- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

My Philosophy of Life, Essay Example

Pages: 6

Words: 1566

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

In all honesty, the subject here causes me some problems, at least at first. In simple terms, I am not at all sure that I want any type of philosophy of life. In my mind this would somehow translate to a kind of limitation, or an “outlook” that might prevent me from taking in new experience and actually learning more about what life truly means. I have known people who strongly believe in a positive viewpoint, for instance. Their life philosophies are based on seeking the good in the world around them, and I am certainly not about to argue with such beliefs. At the same time, I feel that such a way of thinking creates borders. It is a philosophy as a focus, and I do not believe that life may be so confined, or neatly fit into any such approach. In all fairness, I have the same opinion regarding those who practice philosophies of extreme caution, or who believe that life is an arena in which they are entitled to take as much as possible. Put another way, whenever I have actually heard or read of a life philosophy, my first thought is invariably that life may not nicely accommodate it. Life, as I see it, has ideas all its own and is not concerned with how anyone chooses to view it.

I am aware that, even in saying this, I am in a sense offering a philosophy anyway. I imagine that is my own dilemma, and one I should at least try to explore. I think back on my life thus far, then, and am struck by one consistent factor: it has never failed to surprise me, in ways both good and bad. Even when experience has been painful, I have sometimes been aware that I do not respond to it in a pained way. Similarly, I have gone through whole periods of my life when everything was going well, yet I have felt a sense of dissatisfaction. I know that my reactions in all ways are powerfully influenced by the world around me. I have been disappointed in not feeling happy, I know, because the circumstances were supposed to make me feel that way, and everyone around me encouraged this as natural. Still, those feelings of happiness have sometimes eluded me, just as I have been strangely empowered or happy when things have gone wrong. How can I even consider a “philosophy,” then, when I cannot even follow the course of thinking and feeling in place for the rest of the world? No matter how I move through my life, it always seems that I am not in a place where a common perception about living matches how I truly think and feel, so I tend to veer from any ideology. It is not that I disagree with them; it is that, for me, they do not fit.

This then brings me to another question: what is it that I think life is? If I can better understand that, I may be on my way to realizing that there is a philosophy for me. After all, there can be no real and consistent view of a thing without an idea of the thing itself. Unfortunately, I “hit a wall” here as well. Great minds have struggled to define life since humanity began, and each seems to have ideas as valid as those different from them. For some, it is meaningless, a kind of dream in which we act our parts to no real purpose. For others, life is a boundless opportunity to grow spiritually and expand the mind and heart to unlimited potentials. For most people, I think, life occupies more of a middle ground; it can be fantastic and enabling, just as it can be empty when no purpose is in sight. In other words, it seems that there is no incorrect view or philosophy of life because it may be, simply, anything and everything at all. Given this thinking, I am not encouraged. I am, in fact, more inclined to see any effort at capturing a philosophy an exercise in futility.

When I then allow myself to take this thinking further, however, it seems that I may be nearing the thing I see as pointless or impossible. That is, since I view life as far too unpredictable to be subject to a single approach or philosophy, I then begin to understand my own role in the entire process. I think of what I earlier said, in regard to mt feelings not following usual patterns and my tendency to react to “life” in unexpected ways. It occurs to me that I am then missing a crucial element in this scenario: myself. I think: everyone, great mind or otherwise, who has wondered about life has done so in the same way, in that the views and feelings must be created by their own life itself. We can seek to see beyond our own experience, but I must wonder at how realistic that ambition is. We are all tied to who and what we are, whether that being is expansive or not; in all cases, the individual can only define life through what the individual has experienced and is capable of perceiving from the experience. Life is the self, in a very real sense. We are not channels out outside elements in some vast, inexplicable equation; we are the equation because life is literally what we make it. This happens through actual “living” and action, and it happens equally through our perceptions.

I then begin to feel that I am nearing a truth. I am life, and life is not some external essence I must consider. At the same time, everyone and everything around me is life as well, just as validly as I am. Here, then, is where I can shape a philosophy. It is not a structure, or even a foundation. Rather, it is more an impression accepted. It is that life is a thing completely bound to myself, and in “partnership” with me. It is, most important of all, never fixed. It cannot be, because every moment changes who I am in some way, and because of this intense and purely exponential relationship with the life around me. Life will always be the moment or direction currently affecting or guiding me, and in every sense of living. When my spirit is at its strongest, life is a generous and fine thing because that is what I am giving to it, and life affirms this reality by taking what I can give. When I am small and involved with minor issues or feelings, life shrinks to a cell because I am unable then to see beyond a cell. I referred to what I know is a cliché, in that life is what we make it. This is, however, profoundly true in a literal sense. As I think this is my philosophy, I restate it as: life is what I create, which in turn reflects and creates me.

While I am content with this definition, I am as well unwilling to leave it as so lacking in structure. More exactly, while I firmly believe in the self/life reciprocity I have described, and while I believe this must be a fluid state of being, I nonetheless comprehend that even this shifting relationship places responsibilities on me. On one level, and no matter how “life and I” go on, I believe in good and evil. I believe these are actual forces or energies in the world, and I believe that my mind and my heart must always be directed to knowing and promoting good when I can. This is not necessarily virtuous on my part; I see it more as an acceptance of a reality as basic as the air we breathe. The complex process of life is endlessly open to possibilities generated by my involvement with it, but there remains in the universe, at least in my perception, these polar elements. True meaning is as powerful a thing as good, and meaning may only come when good is pursued, and I believe this because I believe that evil is emptiness. Whatever life becomes for me, then, there is a primal direction to know.

Lastly, there is as well an obligation linked to good, which is that of being expansive. I cannot expect much of life if I do not open myself to the possibilities in place when my openness meets the limitless offerings of what is outside of myself. This is that partnership in place, and when I am doing my part in giving my utmost to it. Strangely, this is not a giving related to effort; rather, it is more a willingness to accept. When I consider all of this, in fact, I find that my philosophy is more complex than I had thought. It insists on my exponential relationship with living as creating life, yet it also demands real awareness. It is open to the new, but it is observant of basic principles. It is what is known through my eyes, but it relies on my expanding my sight to make the most of it. More than anything, my philosophy of life is one that brings life right to me side, always. It holds to the conviction that, no matter how we make it happen, life is what the world around me and I shape every moment.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, Research Paper Example

The Setting in the Fall of the House of Usher, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus on Our Search for Meaning and Why Happiness Is Our Moral Obligation

By maria popova.

In the beautifully titled and beautifully written A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning ( public library ), historian Robert Zaretsky considers Camus’s lifelong quest to shed light on the absurd condition, his “yearning for a meaning or a unity to our lives,” and its timeless yet increasingly timely legacy:

If the question abides, it is because it is more than a matter of historical or biographical interest. Our pursuit of meaning, and the consequences should we come up empty-handed, are matters of eternal immediacy. […] Camus pursues the perennial prey of philosophy — the questions of who we are, where and whether we can find meaning, and what we can truly know about ourselves and the world — less with the intention of capturing them than continuing the chase.

Reflecting on the parallels between Camus and Montaigne , Zaretsky finds in this ongoing chase one crucial difference of dispositions:

Camus achieves with the Myth what the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty claimed for Montaigne’s Essays: it places “a consciousness astonished at itself at the core of human existence.” For Camus, however, this astonishment results from our confrontation with a world that refuses to surrender meaning. It occurs when our need for meaning shatters against the indifference, immovable and absolute, of the world. As a result, absurdity is not an autonomous state; it does not exist in the world, but is instead exhaled from the abyss that divides us from a mute world.

Camus himself captured this with extraordinary elegance when he wrote in The Myth of Sisyphus :

This world in itself is not reasonable, that is all that can be said. But what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart. The absurd depends as much on man as on the world. For the moment it is all that links them together.

To discern these echoes amid the silence of the world, Zaretsky suggests, was at the heart of Camus’s tussle with the absurd:

We must not cease in our exploration, Camus affirms, if only to hear more sharply the silence of the world. In effect, silence sounds out when human beings enter the equation. If “silences must make themselves heard,” it is because those who can hear inevitably demand it. And if the silence persists, where are we to find meaning?

This search for meaning was not only the lens through which Camus examined every dimension of life, from the existential to the immediate, but also what he saw as our greatest source of agency. In one particularly prescient diary entry from November of 1940, as WWII was gathering momentum, he writes:

Understand this: we can despair of the meaning of life in general, but not of the particular forms that it takes; we can despair of existence, for we have no power over it, but not of history, where the individual can do everything. It is individuals who are killing us today. Why should not individuals manage to give the world peace? We must simply begin without thinking of such grandiose aims.

For Camus, the question of meaning was closely related to that of happiness — something he explored with great insight in his notebooks . Zaretsky writes:

Camus observed that absurdity might ambush us on a street corner or a sun-blasted beach. But so, too, do beauty and the happiness that attends it. All too often, we know we are happy only when we no longer are.

Perhaps most importantly, Camus issued a clarion call of dissent in a culture that often conflates happiness with laziness and championed the idea that happiness is nothing less than a moral obligation. A few months before his death, Camus appeared on the TV show Gros Plan . Dressed in a trench coat, he flashed his mischievous boyish smile and proclaimed into the camera:

Today, happiness has become an eccentric activity. The proof is that we tend to hide from others when we practice it. As far as I’m concerned, I tend to think that one needs to be strong and happy in order to help those who are unfortunate.

This wasn’t a case of Camus arriving at some mythic epiphany in his old age — the cultivation of happiness and the eradication of its obstacles was his most persistent lens on meaning. More than two decades earlier, he had contemplated “the demand for happiness and the patient quest for it” in his journal, capturing with elegant simplicity the essence of the meaningful life — an ability to live with presence despite the knowledge that we are impermanent :

[We must] be happy with our friends, in harmony with the world, and earn our happiness by following a path which nevertheless leads to death.

But his most piercing point integrates the questions of happiness and meaning into the eternal quest to find ourselves and live our truth:

It is not so easy to become what one is, to rediscover one’s deepest measure.

A Life Worth Living: Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning comes from Harvard University Press and is a remarkable read in its entirety. Complement it with Camus on happiness, unhappiness, and our self-imposed prisons , then revisit the story of his unlikely and extraordinary friendship with Nobel-winning biologist Jacques Monod.

— Published September 22, 2014 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/09/22/a-life-worth-living-albert-camus/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, albert camus books culture philosophy psychology, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

Life Philosophy 101 – An Introduction

Personal life philosophies are not a common subject and quality information on them can be difficult to find. They can tend to be grouped with other more prescriptive philosophies or reduced to personal slogans like bumper stickers or t-shirts.

Personal Life Philosophies are unique in that there are as many of them as there are individuals. Just as no two people are alike, no two life philosophies are the same. We each have our own basis for understanding ourselves, our lives and the world and our own aspirations for how we seek them to be.

This introduction touches on the essential knowledge that everyone should have to understand personal life philosophies, why they are essential life tools and how they can enrich your life.

Introduction to Life Philosophy Resources

These key concepts establish a common foundation of knowledge. This foundation will be helpful as you develop and live your personal life philosophy.

Start here if you are unfamiliar with life philosophy or want a refresher. Expand each of the sections if you would like more in depth information.

Life philosophy can be a tricky subject to embrace. There are common misconceptions that can bias your understanding and lead you to avoid the whole topic.

Understanding these misconceptions can stop them from preventing knowing and embracing your unique personal philosophy.

Just as we all have our own life philosophy; we all have our own way of learning.

If you prefer, choose the topics you want to cover in the order that works best for you.

Key Concepts about Personal Philosophies

- What is a personal philosophy?

A personal life philosophy is your unique understanding of and perspective on the world and life including how you think life should be lived and the world should be.

Why does this matter? Your personal philosophy is a way to crystalize and make real your understanding of the world and life to help you make sense of it, know what is essential, sharpen your vision and bring clarity to a complex world.

The concept of a personal philosophy is something that is unique and something that is not generally well known or widespread, at least personal philosophies that are well developed and that can bring real value to one’s life. One can wonder why this is so, especially considering the importance of one’s personal philosophy .

In general, personal philosophies include things like your most essential truths and insights about, and highest aspirations, for life and the world. They bring value to your life both through the process of developing them and through helping make more definite thoughts and feelings that can be abstract and difficult to readily access and use in your life.

A personal philosophy encapsulates what is most essential, of great consequence, vital, enlightening and imperative. It is based upon what captures your imagination, demands your attention, comes naturally to you, incites you to action, inspires you, infuriates you, drives you or frees you to the greatest degree.

Personal philosophies are typically stated in a written form such as a set of principles or tenets and sometimes are written in an essay format, though they can take any from that you find useful.

Note: There are a series of related terms used for referring to personal philosophies including personal philosophy on life, living philosophy. Just about every conceivable combination and variation of the words philosophy, life and personal that are used to refer to personal philosophies. Here, the terms personal philosophy, personal life philosophy and life philosophy are used interchangeably.

- What is life philosophy?

Life philosophy is the development and application of your personal philosophy to your life. Life philosophy includes two primary components: your personal philosophy and the ongoing act of making it real through developing and living it.

Why does this matter? Personal philosophies that cannot be or are not used in one’s life, may be interesting to contemplate and discuss over an adult beverage, but they cannot enrich your life unless you actually use them in it.

Beyond the potentially transformational experience of developing a personal philosophy, most of its value is realized through living it. A personal philosophy that is only vague concepts or even one is well formed but unused is of little value. Your personal philosophies can be of great value, but only if it is clear to you and made real in your life. Living your personal philosophy is how you realize the value of it for yourself and the world. There are a wealth of practical and enriching ways that your personal philosophy can be used in your life .

- Why should I put effort into developing my personal philosophy?

Although each of us naturally has the basis for our personal philosophy, most of us do not understand our basis in ways that help us or in ways that we can make use of. Developing your personal philosophy clarifies it for you and helps you gain active knowledge of it.

Why does this matter? The experience of developing your personal philosophy includes connecting with what is essential to you in the world, which is a rewarding and enriching experience itself. Most importantly developing and actively knowing your personal philosophy enables you to use it in your life and realize the value it can bring .

When following a good approach for developing yours, you start to realize the value early in the process. Because of the nature of personal philosophies, you necessarily need to consider your perspective on the world and to understand your thoughts and feelings about it. Most of us do not take the time or invest the effort into actively working to understand our perspective on the world and ourselves. Developing your personal philosophy gives you an opportunity to indulge in doing so in a way that gets around much of the challenge of being too actively introspective, or touchy-feely. With the right approach, getting in touch with your perspective on the world and yourself is rewarding, freeing and simply enjoyable. You may even find it an experience that is affirmational or transformational.

Beyond the enriching personal experience, developing your personal philosophy will clarify your unique understanding of the world and life for you and make it something that you actively know. A personal philosophy that is just thoughts and feelings floating around in your mind has about as much value as a personal desire to become Yoda. It may be an interesting thought, but it probably won’t go much further than that. Your personal philosophy needs to be clear to you and something that you actively know. Clarity is critical so that when you need to use it in your life you don’t have to sort through it to figure out how it applies. Actively knowing your personal philosophy allows you to use it in your life. Not being able to clearly remember your personal philosophy makes it difficult to use in the moment. If you have to refer back to it in some written form it probably doesn’t have the clarity needed to be a real and present part of your life. Part of developing your personal philosophy is crafting it to be clear so that you can and actively know and use it in your life in large and small ways.

The importance (value) of your personal philosophy in life.

Your personal philosophy begins to bring value to your life through the experience of developing it and continues to do so for the rest of your life. It will help you make sense of the world, understand what is meaningful to you, clarify your insights, motivate and inspire you, and help you find and maintain your direction.

What does this mean to me? Your personal philosophy is a real-world life tool. Without it you are in many ways unequipped for life in an increasingly complex and difficult world for you as an individual.

The process of developing your personal philosophy necessarily requires being in touch with the world and yourself. The experience of doing so in a concerted, intentional way helps you crystalize what is meaningful in the world to you. This is one part of the reason why you should put the effort into developing your personal philosophy .

Beyond the experience of developing your personal philosophy, the real importance of a personal philosophy is that it equips you for life in a complex world in ways that can be difficult to do otherwise. Knowing and understanding your essential truths about, and aspirations for, life and the world as well as what you value and what is meaningful to you helps you with some of the most challenging aspects of life. Many of the traditional sources that people have relied upon for these answers are outdated and not relevant in today’s world. Without a personal philosophy you can be left searching for answers when challenges in life arise. Your personal philosophy helps you make sense of life and the challenges you encounter. It also helps you identify things you do that are out of sync with what you place value in and be a source of strength for changing them. It will help you fend off the constant barrage from others trying to make you do and think what they want you to. It provides a clear source of personal direction that can help with difficult or important decisions that you need to make in life. It can help you better understand your unique insights about life and the world and make the most of them. It can even inspire you to do something that is wildly aspirational that you would likely not do without the clarity, vision and meaning that your personal philosophy makes real for you. Knowing and living your personal philosophy will help you be more effective in the world and help you to contribute to realizing the things that you aspire for life and the world to be.What

Why aren't personal philosophies taught on a wider basis?

The primary purpose of education in most parts of the world is to produce individuals that are effective members of society and productive workers. Secondarily the concept of personal philosophies and the individual or “self” are relatively new (see the brief history of personal philosophies ).

Why should I care about this? A personal philosophy is something that is not needed to be a productive worker or effective member of society. It is needed if you are going to live an engaged, meaningful life that aligns with who you are and what you seek for your life and the world to be.

The value of education cannot be overstated. Knowledge is empowering. Self-knowledge, like that used in one’s personal philosophy, is an especially powerful form of knowledge. Unfortunately, self-knowledge is something that most of us must learn on our own without significant guidance or education about it.

An important part of developing a personal philosophy is quality self-knowledge. While some education systems do seek to develop the individual, but even they do not overtly educate individuals on developing self-knowledge. The concept of personal philosophies, the self and self-knowledge are relatively new. Most education systems are based upon century old theory and have not kept up with these concepts or integrated them into their method and curriculum. Imagine if our education systems sought to help people become self-aware, develop self-knowledge and become more enlightened about life and the world, instead of just seeking to produce productive contributing members of society.

A personal philosophy is something that can help you get beyond the narrow vision and relatively low expectations that many educational systems have for you. It can help you become more self-aware, more knowledgeable and more enlightened about life and the world.

What can be included in your personal philosophy?

Anything that you think or feel is essential to your understanding of and perspective on life and the world.

Why is the point? There are some things that can be helpful to include to make your unique personal philosophy more valuable in your life, but in the end, it is up to you.

A personal philosophy is the encapsulation of one’s most essential truths about, and aspirations for, the world, life and one’s self. That said, you can choose what to include in yours. To be able to apply your personal philosophy to your life, it is helpful if one includes things that you uniquely understand about life and the world, or your truths, and how you would like to see the world be, or your aspirations. The two together create a view of what you know about the world that is most significant to you, how you think life and the world should be and your desires for them. Your personal philosophy can include anything you find essential such as what you place value in and find especially meaningful. If there are other aspects of your understanding of yourself, life or the world that you think are substantive, you should include them.

One of the key attributes of your personal philosophy is that it draws upon your unique knowledge of the world and yourself. The types of knowledge that can be used in your life philosophy are those encompassed by knowledge in a broad sense. Often the concept of knowledge is constrained to specific types of knowledge such as that which is taught through formal education or that which can be attained through science and reason. While there are no hard rules about personal philosophies, constraining yourself to narrow definitions of knowledge is limiting. Including what you know beyond your capacity for reason and the realm of scientific proof, such that which you know through emotion and intuition, helps to create a personal philosophy that captures the nature of being human. Einstein’s essay in Living Philosophies is a great example of how this is true. If you are going to apply your personal philosophy to your life, it should be substantive and not oversimplify the nature of life to the point of being of little value in it. It also should not be limited to someone else’s definition of what a life philosophy should entail, or what it should be based upon. Too, it should not be limited to systems thought and belief that have been formalized and categorized. In many ways, personal philosophy allows you to move beyond these prescribed ways of understanding and create a perspective that is rich in meaning to you.

Including those things that are the most significant to you, especially what sets you apart from others, is one approach. For instance, we all place high value on our families, health and livelihood. These are universal and stating them as a personal philosophy, while perfectly valid, may not be very insightful about your personal truths or aspirations for life and the world. In a similar way, a personal philosophy is not necessarily about defining universal truths or answering life’s big questions such as the purpose or meaning of life. These can be included if your knowledge of them is especially significant to you. Your personal philosophy is about understanding and expressing the things that stand out to you above all others.

- What do I need to know to develop my personal philosophy?

Having a reasonably broad view of life and the world is helpful, as is being able to connect with and understanding your perspective on it. An understanding of personal philosophies is also helpful.

Why does this matter to me? While having a broad view of life and the world is important, you can never know, feel or experience everything. When you decide to develop your personal philosophy, it is important to use your perspective on the world to the greatest extent possible. Too, your personal philosophy will likely evolve as you and the world change.

Your personal philosophy necessarily draws upon your understanding of life and the world. If you have limited experience with life and the world, it can be helpful to work to expand your perspective. Even if you have an expansive perspective on the world, being in touch with that perspective is important. You may find it helpful to spend some time reconnecting with your perspective on the world as you craft your personal philosophy. Too, you continue to learn and change throughout your life and the world continues to change at a rapid pace. An effective approach for crafting your personal philosophy should help you connect with what is essential in the world to and to understand why throughout your life.

Having a good connection with yourself is also helpful. This connection allows you to understand your perspective on the world including your thoughts and feelings about it. You may find it necessary to work to create this connection, or to reconnect with yourself if you have lost touch. One of the challenges with creating and maintaining it is the constant barrage we are under from others wanting us to think and do what they want us to. A good connection with yourself helps cut through this barrage. An effective approach for developing your personal philosophy will also help.

Like with most things that you undertake, a good understanding of what you are taking on and what is involved with accomplishing it is advisable. Having an understanding of personal philosophies and what is involved with developing one can help you successfully craft yours so that it is valuable in your life.

- Where did the concept of personal philosophies come from?

While the roots of personal philosophies, individual’s interpretations on what is important in the world, can be seen even in the earliest artwork and myths, personal philosophies per se arrived on the scene much more recently. They appear to have come into general use within the last century or so.

Like most forms of modern thinking, the roots of personal philosophies appear to have evolved along with human thought. Prehistoric evidence for personal views on the world and what is most significant in it are likely captured in the earliest myths and paintings. These early forms of expression undoubtedly included some personal interpretation of the world for practical use. Yet, considering them to be statements of personal philosophy is a stretch at best. The first formal thinking related to personal philosophies dates back to the time of the early thinkers on human condition and the nature of the world that we live in. Religious beliefs and religions evolved from individuals’ personal understanding of the world. Confucius’s writings can be considered a good example of how this happened. Undoubtedly, many of those who have focused their life on the pursuit of philosophy necessarily include what would constitute their own philosophy on life in their work including the first recognized philosophers in the 600-500 BC period. One perspective on philosophy itself is that it can be considered the pursuit of making sense of life and the world. Beyond those who pursued philosophy per se, many great thinkers and people who have put their imprint upon the course of history have recorded their philosophical perspective behind their thinking and actions. Abraham Lincoln is a familiar, notable example, and there are many more. Yet none of these can be considered a personal philosophy per se.

Personal philosophies in the context used here, are prevalent in modern times. In 1931 a volume of Living Philosophies was published by Simon & Schuster and includes short essays about their philosophy on life from notable figures including Albert Einstein. These insightful essays capture their perspective on the world including their beliefs and ideals. Two subsequent volumes were published with essays from other notables, I Believe in 1942 and Living Philosophies in 1990. All of which are worth reading. These essays seem to come the closest to the concept of personal philosophy as used here. Interestingly the concept of individual identity and the self appears to have come into prominence on a similar timeline, within the last century.

The rapid escalation of the challenges facing humanity in general, the shift away from traditional sources and authorities for answers to life’s important questions, the increasingly difficult global environmental and political situation and the escalating assault on our individuality through the ever-present screens we view all seem to be reasons why personal philosophies are becoming more prominent. In many ways, personal philosophies have become a vital form of empowerment for the individual actualizing their individuality.

Using your personal philosophy in your life.

There are virtually limitless ways that you can use your personal philosophy in your life. How you do so will vary based upon where you are in life and what is happening in yours.

Your personal philosophy can be made part of your life in ways large and small. In looking at the importance (value) of your personal philosophy in life , we touched upon many of the ways your personal philosophy brings value to your life including as a source of meaning, a source of guidance for important decisions, a source of strength, a source of vision and insight, even a source of inspiration.

Through actively knowing your personal philosophy you can use it in your daily life as you make decisions and to help guide your actions to be in line with how you seek to be. It can be easy to take the path of least resistance or to succumb, even momentarily, to the toxic messaging constantly targeting you. Actively knowing your personal philosophy helps you be more intentional and fend off this and other forces working against you.

Making your personal philosophy a part of your daily life helps keep what you find essential, place value in, and draw meaning from present in your life. It also provides a reassuring sense of understanding and direction through your essential truths and aspirations.

Your life philosophy can help you better understand yourself and your perspective on just about everything and under any circumstances. Having a well-developed life philosophy also allows you to share and discuss it with others, if you choose to. It can help them understand you and your actions. Sharing your life philosophy or some part of it can be helpful in many situations such as when you have to explain choices that you make which are different from others or that don’t align with their expectations of you.

Your life philosophy can help you achieve a greater sense of meaning and fulfillment. Some think that it is only possible to achieve higher levels of meaning and happiness through the understanding and awareness that knowing and living a personal philosophy can provide.

Common Misconceptions About Personal Philosophies

- I don’t have or need a personal philosophy.

Short Answer : Everyone has some form of a personal philosophy. Most just have not developed it into something they actively know or use in their lives.

Each individuals’ personal philosophy, including yours, is their unique understanding of the world that is developed into a form that can be actively known and used in their life. When you consider the scope of the human experience, including what we can know and feel and how we can know and feel it, and the diversity of individuals, we all truly have our unique understanding of the world.

There is strength in diversity. You as an empowered, self-actualized and enlightened individual build upon what it means to be human and for us to collectively be humanity. Understanding your unique knowledge and wisdom about life and the world will help you become an empowered, self-actualized and enlightened individual.

The kinds of changes that are confronting individuals and humanity require something more than for all of us to live and think the same way, or even subscribe to a defined set of philosophic and religious systems. The scales are tipped toward you becoming more like everyone else. The intentional attempt to control your thoughts and actions through messaging and artificial intelligence is invading all aspects of your life. It is an attempt to make you think and behave in ways that others seek for you to. Actively knowing your understanding of the world and your aspirations for it is not only essential for surviving in an increasingly complex and difficult world, it is key to advancing us as humanity and overcoming the crises that confront us now and in the future.

- Personal philosophies are only for big thinkers.

Short Answer : Each of us has a unique understanding of the world and the ability to define our own personal philosophy. Be wary of anyone or any entity that tries to make you think otherwise. Question their motives.

Society puts undue importance on the personal philosophies of famous people and preserves their perspective through time disproportionally. Historically, this may have largely been a product of our ability to record and publish the thoughts of any one person. It may be no coincidence that as our ability to record our individual thinking and share it broadly the importance of the big thinkers’ thoughts is diminishing.

For some reason, we have a tendency to treat some and their thoughts effectively as idols. We often turn to those that we view as authorities for answers to life’s important questions when the reality is that they are just people and their answers are merely that, theirs. They are not better than the answers that we each have, yet we often place more value in them than our own.

In the end, you determine your personal philosophy. If you decide to adopt a philosophy or components of a philosophy that is defined by someone else, that is your choice. The important thing is that you have explored the world enough to know what makes sense to you and works for you. Too, nothing in life is cast in stone. The world changes and we all grow and learn. As you do, your personal philosophy should as well.

But it is not only the famous who leave their marks. Every single one of us has, I believe, a significant part to play in the scheme of things. Some contributors that go unrecognized may nevertheless be of the utmost importance.

– Jane Goodall in her personal philosophy within Living Philosophies 1990.

- A personal philosophy is a one sentence maxim.

Short Answer : You’re not a car and your personal philosophy shouldn’t be a bumper sticker.

Everyone likes a concise statement that captures the essence of a common experience in life. It’s also good to have simple rules in life to remind us of basic things we know. They have practical value in specific situations. That said, simple rules of life, even a collection of really good ones do not amount to a personal philosophy.

An effective personal philosophy encompasses the scope of your unique perspective on life and the world. To be effective it needs to be able to help you make sense of a complex and dynamic world. It needs to be able to help you derive meaning from your life, understand what you value and what you seek for life and the world to be. If you truly can express your personal philosophy in one sentence, beyond likely being an amazing sentence, it would no longer be a maxim that is applicable only in specific situations. It would be a broad, robust expression of your unique perspective on the world and life including your truths about them and how you think they should be.

Like philosophy in general, personal philosophies are esoteric and don’t have practical value.

Short Answer : This misconception is completely understandable. Philosophy is generally something that can be challenging to convert to real world value. Personal philosophies are different as they are practical real-life tools.

Unfortunately, there is not a good substitute for the word “philosophy” in the English language that fully captures its meaning in the sense of being “a set of basic concepts and beliefs that are of value as guidance in practical ways.” When we hear or read the world philosophy, we most often think of one of the other meanings primarily “systems of thought” as in skepticism, pragmatism or existentialism and the famous men (typically) that professed their virtues and argued for their specific flavor as the one best perspective on the world and life. In many ways, personal philosophies are the antithesis of these systems of thought. Personal philosophies are individual perspectives meant to have meaning and value for one individual rather than general principles that apply to all. Applied practical value in life is one of the defining characteristics of personal life philosophies. If a personal philosophy is not of practical value in life, it is not much of a personal philosophy at all.

I already know my personal philosophy. I don’t need to develop it.

Short Answer : If you have and know your personal philosophy, you should be able to state it now in a clear and concise way that you can apply in your life. If not, crafting it into a clear form to you and that you actively know will help you realize real-world value from it.

- I’m just one normal person, my personal philosophy is of no value to the world.

Short Answer : Humanity is a collective of unique individuals. Who we are, what we know, what we will become and what defines us our humanity is determined by the sum total of each of us. Your individuality, including your unique understanding of and perspective on life and the world, has real implications for humanity collectively.

It can be easy to sell oneself short considering the hype and focus given to people with power, money and fame. This is exactly what you are doing if you truly think that your personal philosophy is not of consequence to the world.

At the very least, understanding your unique perspective on the world and life, will hedge off the homogeneity we are being driven toward by the systems and institutions that we have created. Systems and institutions controlled by and for the benefit of those with power, money and fame. Systems, institutions and people that want you to think and act in ways that benefit them. Dismissing the value of your personal philosophy and not developing yours is playing their game. Their game of control lets them have power over you and makes you even more susceptible to thinking and acting like they want you to as long as you are passive to it.

Your personal philosophy will lead you to a better understanding of the world. That understanding will prompt you to take some action to make it better, at least within your immediate world. Developing and knowing your personal philosophy may even lead you to do something that you never thought you would. That action may have implications beyond what you expect, and makes a substantial difference in the lives of others and the course of the world.

Be better equipped to develop and live your personal philosophy.

On Terms of Your Own:

The Pursuit of Being and Fulfillment in a Challenging World.

Navigate 101 by Topic

Key Concepts :

- The importance (value) of a personal philosophy.

- Why aren’t personal philosophies taught on a wider basis?

- What can be included in a personal philosophy?

- Using my personal philosophy in my life .

Common Misconceptions :

- Like philosophy in general, personal philosophies are esoteric and don’t have any practical value.

- I already know my personal philosophy. I don’t need to formalize it.

We’re in Yellow Springs, Ohio

Meaning and the good life

A Japanese religious community makes an unlikely home in the mountains of Colorado

Thinkers and theories

Rawls the redeemer

For John Rawls, liberalism was more than a political project: it is the best way to fashion a life that is worthy of happiness

Alexandre Lefebvre

‘Everydayness is the enemy’ – excerpts from the existentialist novel ‘The Moviegoer’

Beyond authenticity

In her final unfinished work, Hannah Arendt mounted an incisive critique of the idea that we are in search of our true selves

Samantha Rose Hill

Philosophy was once alive

I was searching for meaning and purpose so I became an academic philosopher. Reader, you might guess what happened next

Pranay Sanklecha

Learning to be happier

In order to help improve my students’ mental health, I offered a course on the science of happiness. It worked – but why?

Biography and memoir

The unique life philosophy of Abdi, born in Somalia, living in the Netherlands

Why strive? Stephen Fry reads Nick Cave’s letter on the threat of computed creativity

Beauty and aesthetics

The grit of cacti and the drumbeat of time shape a sculptor’s life philosophy

Ageing and death

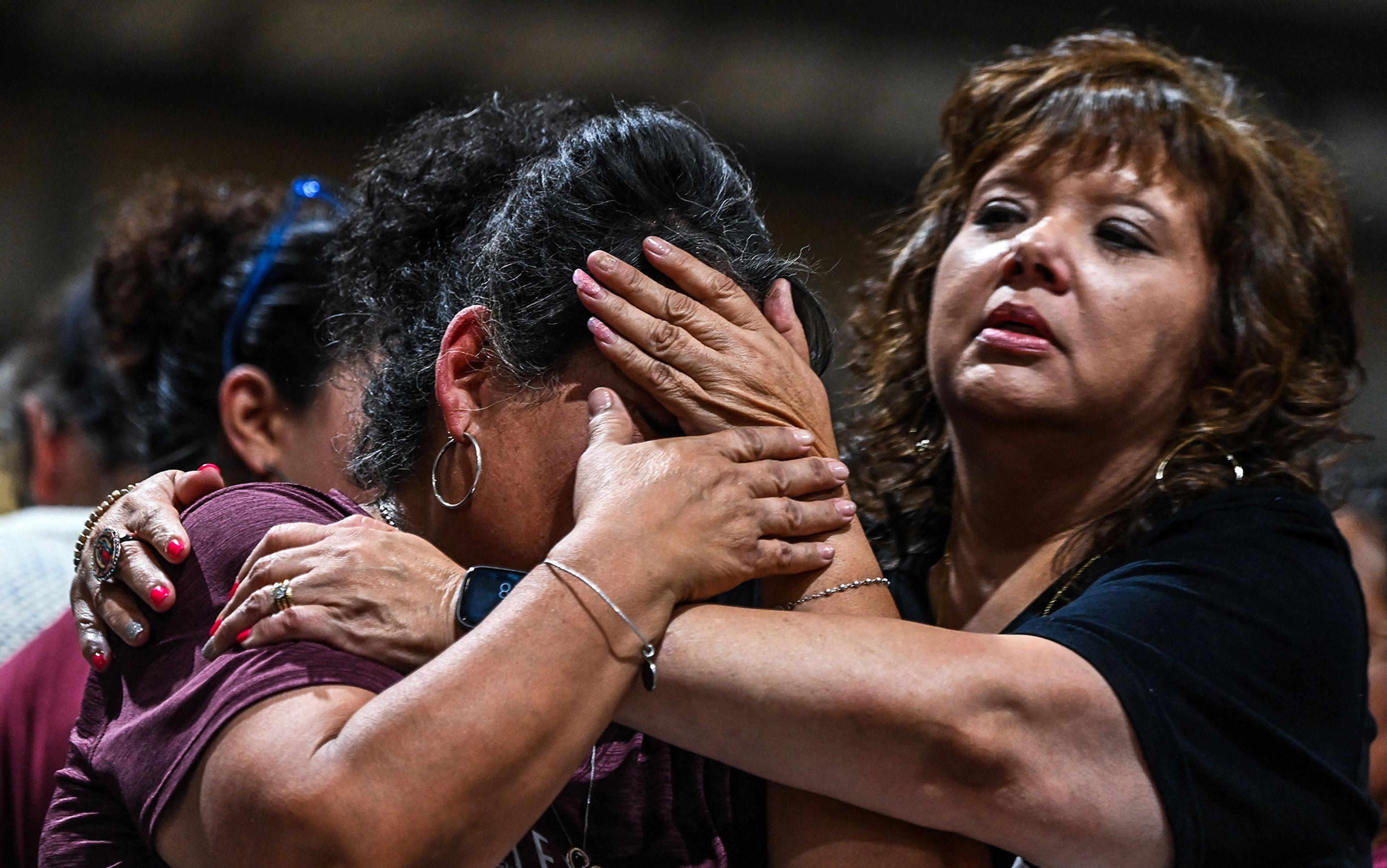

Witness the pain

When loved ones are traumatically lost, bereaved families become accidental activists by turning grief into grievance

Chris Bobel

Modern life subjects us to all-consuming demands. That’s why we should reflect on what it means to step away from it all

David J Siegel

Cognition and intelligence

Are you an artistic genius?

Maybe not, but if that’s the threshold you use for creativity in your life, you are coming at the problem all wrong

James C Kaufman

Even in modern secular societies, belief in an afterlife persists. Why?

Spirituality

Trek alongside spiritual pilgrims on a treacherous journey across Pakistan

Freedom at work

There is always a demand for more jobs. But what makes a job good? For that, Immanuel Kant has an answer

The world turns vivid, strange and philosophical for one plane crash survivor

Stories and literature

Solace and saudade

In the face of an inscrutable, indifferent universe, Pessoa suggests we cultivate a certain longing for the elusive horizon

Jonardon Ganeri & Sarah Seymour

Philosophy of religion

A new paganism

Now is the time to revitalise our relationship with nature and immerse ourselves in the little wonders of the universe

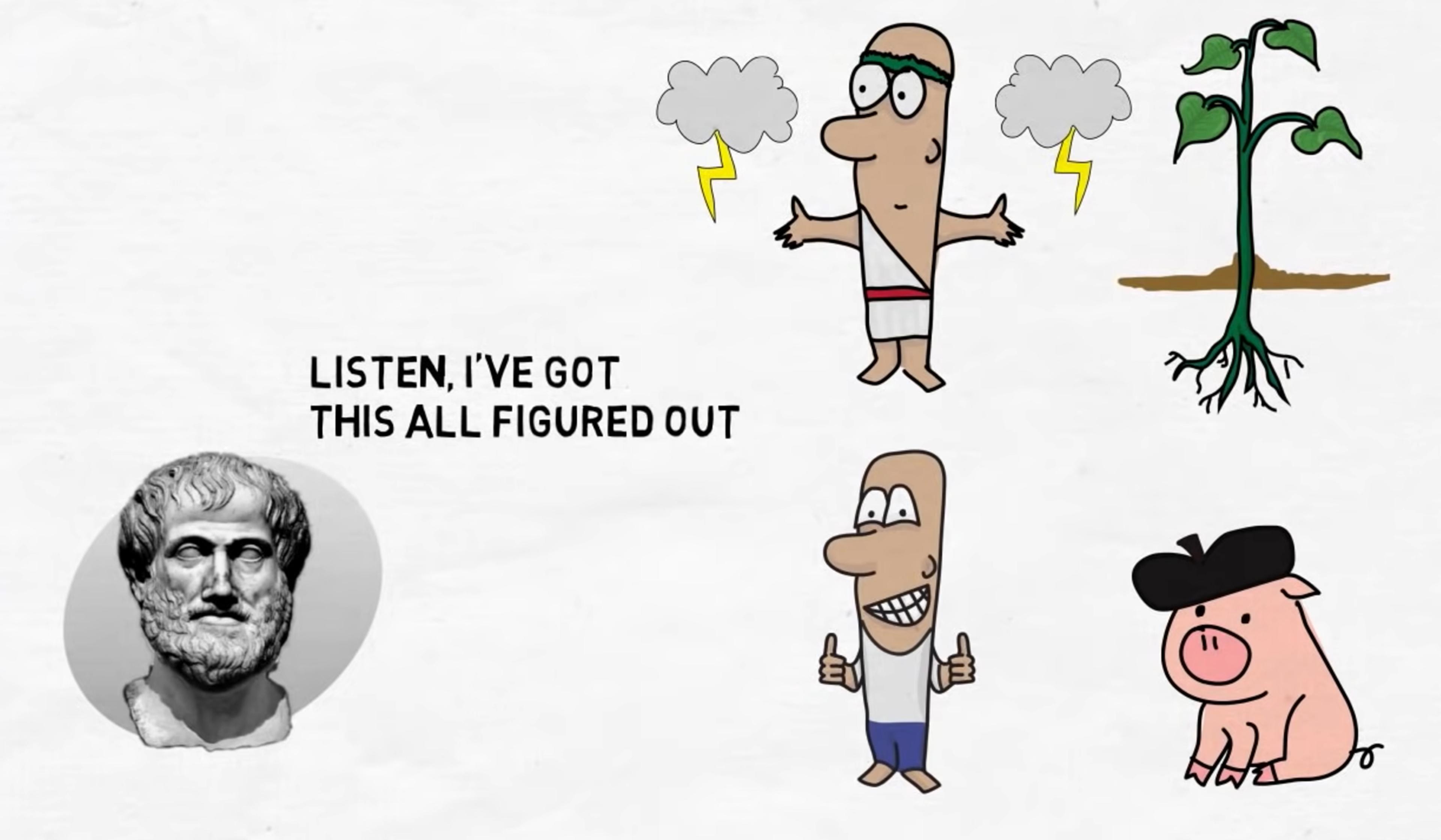

Why Aristotle believed that philosophy was humanity’s highest purpose

Comparative philosophy

How to become wise

Practice is at the heart of Korean philosophy. In order to lead a good life, hone your daily rituals of self-cultivation

Kevin Cawley

Attuned to the aesthetic

The ultimate value of the world can be discovered if you are sensitive to what is beautiful

Tom Cochrane

You’re astonishing!

Life can be better appreciated when you remember how wonderfully and frighteningly unlikely it is that you exist at all

Timm Triplett

Virtues and vices

Look on the dark side

We must keep the flame of pessimism burning: it is a virtue for our deeply troubled times, when crude optimism is a vice

Mara van der Lugt

The end of travel

Driven by the need for a storied life, I relished the opportunity for endless travel. Is that a moment in time, now over?

Henry Wismayer

The Meaning of Life

Many major historical figures in philosophy have provided an answer to the question of what, if anything, makes life meaningful, although they typically have not put it in these terms. Consider, for instance, Aristotle on the human function, Aquinas on the beatific vision, and Kant on the highest good. While these concepts have some bearing on happiness and morality, they are straightforwardly construed as accounts of which final ends a person ought to realize in order to have a significant existence. Despite the venerable pedigree, it is only in the last 50 years or so that something approaching a distinct field on the meaning of life has been established in analytic philosophy, and it is only in the last 25 years that debate with real depth has appeared. Concomitant with the demise of positivism and of utilitarianism in the post-war era has been the rise of analytical enquiry into non-hedonistic conceptions of value grounded on relatively uncontroversial (but not universally shared) judgments or “intuitions,” including conceptions of meaning in life. English-speaking philosophers can be expected to continue to find life's meaning of interest as they increasingly realize that it is a distinct line of enquiry that admits of rational enquiry to no less a degree than more familiar normative categories such as well-being, right action, and distributive justice.

This survey critically discusses approaches to meaning in life that are prominent in contemporary English-speaking philosophical literature. To provide context, sometimes it mentions other texts, e.g., in Continental philosophy or from before the 20 th century. However, the central aim is to acquaint the reader with recent analytic work on life's meaning and to pose questions about it that are currently worthy of consideration.

When the topic of the meaning of life comes up, people often pose one of two questions: “So, what is the meaning of life?” and “What are you talking about?” The literature can be divided in terms of which question it seeks to answer. This discussion begins by addressing works that discuss the latter, abstract question regarding the sense of talk of “life's meaning,” i.e., that aim to clarify what we are asking when we pose the question of what, if anything, makes life meaningful. Then it considers texts that provide answers to the more substantive question. Some accounts of what makes life meaningful provide particular ways to do so, e.g., by making certain achievements (James 2005), developing moral character (Thomas 2005), or learning from relationships with family members (Velleman 2005). However, most recent discussions of meaning in life are attempts to capture in a single principle all the variegated conditions that confer meaning on life. This survey focuses heavily on the articulation and evaluation of these theories of what makes life meaningful. It concludes by examining nihilist views that the conditions necessary for meaning in life do not obtain.

1. The Meaning of “Meaning”

2.1 god-centered views, 2.2 soul-centered views, 3.1 subjectivism, 3.2 objectivism, 4. nihilism, works cited, collections, books for the general reader, other internet resources, related entries.

One part of the field on life's meaning consists of the systematic attempt to clarify what people mean when they ask in virtue of what life has meaning. This section addresses different accounts of the sense of talk of “life's meaning” (and of “significance,” “importance,” and other synonyms). A large majority of those writing on life's meaning deem talk of it centrally to indicate a positive final value that an individual's life can exhibit. So, few believe either that a meaningful life is a neutral quality or that what is of key interest is the meaning of all biological life or of the human species. Most ultimately want to know whether and how the existence of one of us over time has meaning, a certain property that is desirable for its own sake.

Beyond drawing the distinction between the life of an individual and that of a group, there has been very little discussion of life as the bearer of meaning. For instance, is the individual's life best understood biologically ( qua human) or not (person) (Flanagan 1996)? And if an individual is loved from afar, can it affect the meaningfulness of her “life” (Brogaard and Smith 2005, 449)?

Returning to topics on which there is consensus, most writing on meaning believe that it comes in degrees such that some periods of life are more meaningful than others and that some lives as a whole are more meaningful than others (perhaps contra Britton 1969, 192). Note that one can coherently hold the view that some people's lives are less meaningful than others, or even meaningless, and still maintain that people have an equal moral status. Consider a consequentialist view according to which each individual counts for one in virtue of having a capacity for a meaningful life (cf. Railton 1984), or a Kantian view that says that people have an intrinsic worth in virtue of their capacity for autonomous choices, where meaning is a function of the exercise of this capacity (Nozick 1974, ch. 3). On both views, morality could counsel an agent to help people with relatively meaningless lives, at least if the condition is not of their choosing.

Another uncontroversial element of the sense of “meaningfulness” is that it connotes a good that is conceptually distinct from happiness or rightness. First, to ask whether someone's life is meaningful is not one and the same as asking whether her life is happy or well off. A life in an experience or virtual reality machine could conceivably be happy but is not a prima facie candidate for meaningfulness, and, furthermore, one's life logically could become meaningful precisely by sacrificing one's welfare, e.g., by helping others at the expense of oneself. Second, asking whether a person's existence is significant is not identical to considering whether she has been morally upright; there seem to be ways to enhance meaning that have nothing to do with morality, for instance making a scientific discovery. Of course, one might argue that a life would be meaningless if (or even because) it were immoral or unhappy, particularly given Aristotelian conceptions of these disvalues. However, that is to posit a synthetic relationship between the concepts, and is far from indicating that speaking of “meaning in life” is analytically a matter of connoting ideas regarding welfare or morality, which is what I am denying here. My point is that the question of what makes a life meaningful is conceptually distinct from the question of what makes a life well off or morally upright, even if it turns out that the best answer to the question of meaning appeals to an answer to one of these other evaluative questions.

If talk about meaning in life is not by definition talk about welfare or morality, then what is it about? There is as yet no consensus in the field. One answer is that a meaningful life is one that by definition has achieved choice-worthy purposes (Nielsen 1964) or involves satisfaction upon having done so (Wohlgennant 1981). However, this analysis seems too broad for being unable to distinguish the concept of a meaningful life from that of a moral life, which could equally involve attaining worthwhile ends and feeling good upon doing so. We seem to need an account of which purposes are relevant to meaning, with some suggesting they are purposes that not only have a positive value, but also render a life coherent (Markus 2003), make it intelligible (Thomson 2003, 8-13), or transcend one's animal nature (Levy 2005), all of which connote something different from morality and also happiness.

Now, it might be that a focus on any kind of purpose is too narrow for ruling out the logical possibility that meaning could inhere in certain actions, experiences, states, or relationships that have not been adopted as ends and willed and that perhaps even could not be, e.g., being an immortal offshoot of an unconscious, spiritual force that grounds the physical universe, as in Hinduism. In addition, the above purpose-based analyses exclude as not being about life's meaning some of the most widely read texts that purport to be about it, namely, Jean-Paul Sartre's (1948) existentialist account of meaning being constituted by whatever one chooses, and Richard Taylor's (1970, ch. 18) discussion of Sisyphus being able to acquire meaning in his life merely by having his strongest desires satisfied. These are prima facie accounts of meaning in life, but do not necessarily involve the attainment of purposes that foster coherence, intelligibility or transcendence.

The latter problem also faces the alternative suggestion that talk of “life's meaning” is not necessarily about purposes, but is rather just a matter of referring to goods that are qualitatively superior, worthy of love and devotion, and appropriately awed (Taylor 1989, ch. 1). It is implausible to think that whatever choices one ends up making or whichever desires one happens to rank highly fit these criteria.

Although relatively few have addressed the question of whether there exists a single, primary sense of “life's meaning,” the inability to find one so far might suggest that none exists. In that case, it could be that the field is united in virtue of addressing certain overlapping but not equivalent ideas that have family resemblances (Metz 2001). Perhaps when one of us speaks of “meaning in life,” we have in mind one of these ideas: certain conditions that are worthy of great pride or admiration, values that warrant devotion and love, qualities that make a life intelligible, or ends apart from subjective satisfaction and moral duty that are the most choice-worthy.

As the field reflects more on the sense of “life's meaning,” it should try to ascertain whether there is more unity to it than mere family resemblance. And when doing so it should be careful to differentiate the concept of life's meaning from other, closely related ideas. For instance, the concept of a worthwhile life is not identical to that of a meaningful one (Baier 1997, ch. 5). One would not be conceptually confused to claim that a meaningless life full of animal pleasures is most (or even alone) worth living. Furthermore, talk of a “meaningless life” does not simply connote the concept of an absurd (Nagel 1970; Feinberg 1980), unreasonable (Baier 1997, ch. 5), futile (Trisel 2002), or wasted (Kamm 2003, 210-14) life.

Fortunately the field does not need an extremely precise analysis of the concept of life's meaning (or definition of the phrase “life's meaning”) in order to make progress on the substantive question of what life's meaning is. Knowing that meaningfulness analytically concerns a variable and gradient final good in a person's life that is conceptually distinct from happiness, rightness, and worthwhileness provides a certain amount of common ground. The rest of this discussion addresses attempts to theoretically capture the nature of this good.

2. Supernaturalism

Most English speaking philosophers writing on meaning in life are trying to develop and evaluate theories, i.e., fundamental and general principles that are meant to capture all the particular ways that a life could obtain meaning. These theories are standardly divided on a metaphysical basis, i.e., in terms of which kinds of properties are held to constitute the meaning. Supernaturalist theories are views that meaning in life must be constituted by a certain relationship with a spiritual realm. If God or a soul does not exist, or if they exist but one fails to have the right relationship with them, then supernaturalism—or the Western version of it (on which I focus)—entails that one's life is meaningless. In contrast, naturalist theories are views that meaning can obtain in a world as known solely by science. Here, although meaning could accrue from a divine realm, certain ways of living in a purely physical universe would be sufficient for it. Note that there is logical space for a non-naturalist theory that meaning is a function of abstract properties that are neither spiritual nor physical. However, only scant attention has been paid to this possibility in the Anglo-American literature (Williams 1999; Audi 2005).

Supernaturalist thinkers in the monotheistic tradition are usefully divided into those with God-centered views and soul-centered views. The former take some kind of connection with God (understood to be a spiritual person who is all-knowing, all-good, and all-powerful and who is the ground of the physical universe) to constitute meaning in life, even if one lacks a soul (construed as an immortal, spiritual substance). The latter deem having a soul and putting it into a certain state to be what makes life meaningful, even if God does not exist. Of course, many supernaturalists believe that certain relationships with God and a soul are jointly necessary and sufficient for a significant existence. However, the simpler view is common, and often arguments proffered for the more complex view fail to support it any more than the simpler view.

The most widely held and influential God-based account of meaning in life is that one's existence is more significant, the better one fulfills a purpose God has assigned. The familiar idea is that God has a plan for the universe and that one's life is meaningful to the degree that one helps God realize this plan, perhaps in the particular way God wants one to do so. Fulfilling God's purpose (and doing so freely and intentionally) is the sole source of meaning, with the existence of an afterlife not necessary for it (Brown 1971; Levine 1987; Cottingham 2003). If a person failed to do what God intends him to do with his life, then, on the current view, his life would be meaningless.

“Purpose theorists” differ over what it is about God's purpose that makes it uniquely able to confer meaning on human lives. Some argue that God's purpose could be the sole source of invariant moral rules, where a lack of such would render our lives nonsensical (Craig 1994; Cottingham 2003, 2005, ch. 3). However, Euthyphro problems arguably plague this rationale; God's purpose for us must be of a particular sort for our lives to obtain meaning by fulfilling it (as is often pointed out, serving as food for intergalactic travelers won't do), which suggests that there is a standard external to God's purpose that determines what the content of God's purpose ought to be. In addition, critics argue that a universally applicable and binding moral code is not necessary for meaning in life, even if the act of helping others is. Other purpose theorists contend that having been created by God for a reason would be the only way that our lives could avoid being contingent (Craig 1994; cf. Haber 1997). But it is unclear whether God's arbitrary will would avoid contingency, or whether his non-arbitrary will would avoid contingency anymore than a deterministic physical world. Furthermore, the literature is still unclear what contingency is and why it is a deep problem. Still other purpose theorists maintain that our lives would have meaning only insofar as they were intentionally fashioned by a creator, thereby obtaining meaning of the sort that an art-object has (Gordon 1983). Here, though, freely choosing to do any particular thing would not be necessary for meaning, and everyone's life would have an equal degree of meaning, which are both counterintuitive implications. Are all these criticisms sound? Is there a promising reason for thinking that fulfilling God's (as opposed to any human's) purpose is what constitutes meaning in life?

Not only does each of these versions of the purpose theory have specific problems, but they all face this shared objection: if God assigned us a purpose, God would degrade us and hence undercut the possibility of us obtaining meaning from fulfilling the purpose (Baier 1957, 118-20; Murphy 1982, 14-15; Singer 1996, 29). This objection goes back at least to Jean-Paul Sartre (1948, p. 45), and there are many replies to it in the literature that have yet to be assessed (e.g., Hepburn 1965, 271-73; Brown 1971, 20-21; Davis 1986, 155-56; Hanfling 1987, 45-46; Moreland 1987, 129; Walker 1989; Metz 2000, 297-302; Jacquette 2001, 20-21).

Robert Nozick presents a God-centered theory that focuses less on God as purposive and more on God as infinite (Nozick 1981, ch. 6; Nozick 1989, chs. 15-16; see also Cooper 2005). The basic idea is that for a finite condition to be meaningful, it must obtain its meaning from another condition that has meaning. So, if one's life is meaningful, it might be so in virtue of being married to a person, who is important. And, being finite, the spouse must obtain his or her importance from elsewhere, perhaps from the sort of work he or she does. And this work must obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is meaningful, and so on. A regress on meaningful finite conditions is present, and the suggestion is that the regress can terminate only in something infinite, a being so all-encompassing that it need not (indeed, cannot) go beyond itself to obtain meaning from anything else. And that is God. The standard objection to this rationale is that a finite condition could be meaningful without obtaining its meaning from another meaningful condition; perhaps it could be meaningful in itself, or obtain its meaning by being related to something beautiful, autonomous or otherwise valuable for its own sake (but not meaningful).

The purpose- and infinity-based rationales are the two most common instances of God-centered theory in the literature, and the naturalist can point out that they arguably share a common problem: a purely physical world seems able to do the job for which God is purportedly necessary. Nature seems able to ground a universal morality and the sort of final value from which meaning might spring. And other God-based views seem to suffer from this same problem. For two examples, some claim that God must exist in order for there to be a just world, where a world in which the bad do well and the good fare poorly would render our lives senseless (Craig 1994; cf. Cottingham 2003, pt. 3), and others maintain that God's remembering all of us with love is alone what would confer significance on our lives (Hartshorne 1984; Hartshorne 1996). However, the naturalist will point out that an impersonal Karmic force could justly distribute penalties and rewards in the way a retributive personal judge would, and that actually living together in loving relationships would seem to confer more meaning on life than a loving fond remembrance.

A second problem facing all God-based views is the existence of apparent counterexamples. If we think of the stereotypical lives of Albert Einstein, Mother Teresa, and Pablo Picasso, they seem meaningful even if we suppose there is no all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-good spiritual person who is the ground of the physical world. Even religiously inclined philosophers find this hard to deny (Quinn 2000, 58; Audi 2005), though some of them suggest that a supernatural realm is necessary for a “deep” or “ultimate” meaning (Nozick 1981, 618; Craig 1994, 42). What is the difference between a deep meaning and a shallow one? And why think a spiritual existence is necessary for the former?

At this point, the supernaturalist could usefully step back and reflect on what it might be about God that would make Him uniquely able to confer meaning in life, perhaps as follows from the perfect being theological tradition. For God to be solely responsible for any significance in our lives, God must have certain qualities that cannot be found in the natural world, these qualities must be qualitatively superior to any goods possible in a physical universe, and they must be what ground meaning in it. Here, the supernaturalist could argue that meaning depends on the existence of a perfect being, where perfection requires properties such as atemporality, simplicity and immutability that are possible only in a spiritual realm (Metz 2000; cf. Morris 1992; contra Brown 1971 and Hartshorne 1996). Perhaps meaning would come from loving a perfect being or from orienting one's life toward it in other ways such as imitating it or perhaps even fulfilling its purpose.

Although this might be a promising strategy for a God-centered theory, it faces a serious dilemma. On the one hand, in order for God to be the sole source of meaning, God must be utterly unlike us; for the more God were like us, the more reason there would be to think we could obtain meaning from ourselves, absent God. On the other hand, the more God is utterly unlike us, the less clear it is how we could obtain meaning by relating to Him. How can one love a being that cannot change? How can one imitate such a being? Could an immutable, atemporal, simple being even have purposes? Could it truly be a person? And why think an utterly perfect being is necessary for meaning? Why would not a very good but imperfect being confer some meaning?

Recall that a soul-centered theory is the view that meaning in life comes from relating in a certain way to an immortal, spiritual substance that supervenes on one's body when it is alive and that will forever outlive its death. If one lacks a soul, or if one has a soul but relates to it in the wrong way, then one's life is meaningless. There are two prominent arguments for a soul-based perspective.

The first one is often expressed by laypeople and is suggested by the work of Leo Tolstoy (1884; see also Hanfling 1987, 22-24; Morris 1992, 26; Craig 1994). Tolstoy argues that for life to be meaningful something must be worth doing, that nothing is worth doing if nothing one does will make a permanent difference to the world, and that doing so requires having an immortal, spiritual self. Many of course question whether having an infinite effect is necessary for meaning (e.g., Schmidtz 2001; Audi 2005, 354-55). Others point out that one need not be immortal in order to have an infinite effect (Levine 1987, 462), for God's eternal remembrance of one's mortal existence would be sufficient for that.

The other major rationale for a soul-based theory of life's meaning is that a soul is necessary for perfect justice, which, in turn, is necessary for a meaningful life. Life seems nonsensical when the wicked flourish and the righteous suffer, at least supposing there is no other world in which these injustices will be rectified, whether by God or by Karma. Something like this argument can be found in the Biblical chapter Ecclesiastes , and it continues to be defended (Davis 1987; Craig 1994). However, like the previous rationale, the inferential structure of this one seems weak; even if an afterlife were required for just outcomes, it is not obvious why an eternal afterlife should be thought necessary (Perrett 1986, 220).

Work has been done to try to make the inferences of these two arguments stronger, and the basic strategy has been to appeal to the value of perfection (Metz 2003a). Perhaps the Tolstoian reason why one must live forever in order to make the relevant permanent difference is an agent-relative need to honor an infinite value, something qualitatively higher than the worth of, say, pleasure. And maybe the reason why immortality is required in order to mete out just deserts is that rewarding the virtuous requires satisfying their highest free and informed desires, one of which would be for eternal flourishing of some kind. While far from obviously sound, these arguments at least provide some reason for thinking that immortality is necessary to satisfy the major premise about what is required for meaning.

However, both arguments are still plagued by a problem facing the original versions; even if they show that meaning depends on immortality, they do not yet show that it depends on having a soul. If one has a soul, then one is by definition immortal, but it is not true that if one is immortal, then one necessarily has a soul. Perhaps being able to upload one's consciousness into an infinite succession of different bodies in an everlasting universe would count as an instance of immortality without a soul. Such a possibility would not require an individual to have an immortal spiritual substance (imagine that when in between bodies, the information constitutive of one's consciousness were temporarily stored in a computer). What reason is there to think that one must have a soul in particular for life to be significant?

The most promising reason seems to be one that takes us beyond the simple version of soul-centered theory to the more complex view that both God and a soul constitute meaning. The best justification for thinking that one must have a soul in order for one's life to be significant seems to be that significance comes from uniting with God in a spiritual realm such as Heaven, a view espoused by Thomas Aquinas, Leo Tolstoy (1884), and contemporary religious thinkers (e.g., Craig 1994). Another possibility is that meaning comes from honoring what is divine within oneself, i.e., a soul (Swenson 1949).