- OJIN Homepage

- Table of Contents

- Volume 23 - 2018

- Number 2: May 2018

- Evidence Psychiatric Mental Health Interventions

Evidence for Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing Interventions: An Update (2011 through 2015)

Dr. Bekhet is an Associate Professor at Marquette University College of Nursing in Milwaukee, WI. She received aBSN and MSN from Alexandria University in Alexandria, Egypt. She received a PhD from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, OH. Her clinical experience in psychiatric nursing is with persons having schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and depressive disorders. She has taught psychiatric mental health nursing to undergraduate and direct entry students. She has also advised PhD students. Dr. Bekhet’s program of research focuses on the effects of positive cognitions and resourcefulness in overcoming adversity in vulnerable populations. Her research has been funded by Sigma Theta Tau International; American Psychiatric Nursing Foundation; International Society of Psychiatric Mental Health Nurses; and Marquette University. She is a past recipient of a Midwest Nursing Research Society Mentorship Grant Award, and has received the Award for Excellence from the CWRU Nursing Alumni Association in 2011 and the Way-Klinger Young Scholar Award from Marquette University in 2012. More recently, she was awarded the 2014 research award from the International Society of Psychiatric Mental Health Nurses. Dr. Bekhet has published numerous articles and presented numerous papers and posters at regional, national, and international conferences.

Dr. Zauszniewski is the Kate Hanna Harvey Professor in Community Health Nursing, and Director of the PhD in Nursing Program at the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), Cleveland, OH. She received a PhD and MSN from CWRU, Cleveland, OH; a MA in Counseling and Human Services from John Carroll University, Cleveland, OH; a BA in psychology from Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH; and a diploma in nursing from St. Alexis Hospital School of Nursing, Cleveland, OH. She has practiced nursing for 42 years, including 33 years in the field of psychiatric-mental health nursing; she has experience as a staff nurse, clinical preceptor, head nurse, supervisor, patient care coordinator, nurse educator, and nurse researcher, and is board certified by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). Her program of research focuses on the identification of factors and strategies to prevent depression and to preserve healthy functioning across the lifespan. She is best known for her research examining the development and testing of nursing interventions to teach resourcefulness skills to family caregivers. She has received research funding from the National Institutes of Nursing Research and Aging; the National Institutes of Health; Sigma Theta Tau International; the American Nurses Foundation; Midwest Nursing Research Society; and the State of Ohio Board of Regents.

Denise Matel-Anderson is a doctoral student at Marquette University College of Nursing in Milwaukee, WI. She holds an Advanced Practice Nurse Prescriber license, and is currently working on a PhD in nursing with a focus on mental health. She has three publications in mental health nursing journals. Ms. Matel-Anderson currently lectures at Carroll University, Waukesha, WI, in the undergraduate mental health nursing theory course, and serves as a nurse practitioner on the medical team at an acute mental health facility.

Jane Suresky is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing of Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, OH. She has received DNP and MSN degrees from CWRU, and a BSN degree from Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH. Her clinical experience in psychiatric nursing covers the areas of psychobiological research, adolescent dual diagnosis, and mood disorders. She has taught psychiatric mental health nursing to undergraduate and graduate students. In addition, she has been involved in nursing research that focuses on the stress of the female family members of the severely mentally ill.

Mallory Stonehouse recently graduated with a Master of Science in Nursing degree from Marquette University in Milwaukee, WI, where she completed the adult-older adult, primary care, nurse practitioner program. She is a registered nurse at Froedtert Community Memorial Hospital in Wisconsin, where she works on the Behavioral Health Unit. Ms. Stonehouse holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology.

- Figures/Tables

This state-of-the-evidence review summarizes characteristics of intervention studies published from January 2011 through December 2015, in five psychiatric nursing journals. Of the 115 intervention studies, 23 tested interventions for mental health staff, while 92 focused on interventions to promote the well-being of clients. Analysis of published intervention studies revealed 92 intervention studies from 2011 through 2015, compared with 71 from 2006 through 2010, and 77 from 2000 through 2005. This systematic review identified a somewhat lower number of studies from outside the United States; a slightly greater focus on studies of mental health professionals compared with clients; and a continued trend for testing interventions capturing more than one dimension. Though substantial progress has been made through these years, room to grow remains. In this article, the authors discuss the background and significance of tracking the progress of intervention research disseminated within the specialty journals, present the study methods used , share their findings , describe the intervention domains and nature of the studies , discuss their findings , consider the implications of these studies , and conclude that continued track of psychiatric and mental health nursing intervention research is essential.

Key Words: best practices, evidence-based practice, psychiatric nursing journals, psychiatric nursing research, published research, research dissemination, research utilization, systematic review, tradition, intervention research

Implementation science is concerned with the translation of research into practice... The past five years have seen a rapidly growing interest in the field of implementation science ( Sorensen & Kosten, 2011 ). Implementation science is concerned with the translation of research into practice; it involves the examination of the challenges and the opportunities for successful, evidence-based changes in practice ( Nilsen, 2015 ). Translating research into practice depends heavily on the dissemination of findings from intervention research to those most likely to use those findings in clinical or community settings. In contrast to implementation, dissemination involves the spread of information about an intervention, for example, through publication of the intervention in professional journals. Dissemination strategies that are actively targeted toward spreading evidence-based findings concerning an intervention may prompt future implementation in clinical practice ( Proctor et al., 2009 ).

Translating research into practice depends heavily on the dissemination of findings from intervention research... Important for psychiatric and mental health nurses, it is critical that implementation of evidence-based findings occurs across multiple settings (i.e., beyond specialty mental healthcare units) to medical settings, such as primary care areas in which mental health services are provided, and to non-specialized settings, such as criminal justice and school systems and community social service agencies, where mental healthcare is delivered (Proctor et al., 2009). However, before implementation can happen, dissemination of findings from well-designed intervention studies that can inform psychiatric and mental health nursing practice is needed.

One of the best mediums for disseminating evidence-based findings in psychiatric and mental health nursing is the professional nursing journals that are most available to practicing psychiatric and mental health nurses. Nursing journals that are specifically designed a specialty are more likely to be read by persons in the given specialty area than are other nursing research journals. Nurses in practice settings, including those at an advanced practice level, may not have access to scientific research journals or may choose not to read them if the research does not appear meaningful for their practice. The goal of this review was to describe the findings from intervention studies disseminated through publication in one of the five psychiatric and mental health nursing specialty journals published from 2011 through 2015.

Background and Significance

Through the years, more psychiatric and mental health nurse researchers have been targeting specialty journals for disseminating findings from intervention research. For example, in previous reviews of intervention studies published in the five major psychiatric and mental health specialty journals, there was a higher percentage of quantitative intervention studies conducted from 2006 through 2010 (84%) than in a similar review conducted from 2000-2005 (64%) ( Zauszniewski, Suresky, Bekhet, & Kidd, 2007 ; Zauszniewski, Bekhet, & Haberlein, 2012 ), indicating increased use of more rigorous, statistical analytic methods in published intervention research over time ( Zauszniewski et al., 2007 ; Zauszniewski et al., 2012 ).

Tracking the progress of intervention research disseminated within the specialty journals in psychiatric and mental health nursing is important for two reasons. First, it provides data to show improvements in dissemination efforts of psychiatric and mental health nurse researchers. Second, it calls attention to the importance for continued dissemination of intervention research to practicing psychiatric and mental health nurses who are in the best positions to implement the findings in practice. Therefore, the purpose of this review of the same, five, peer-reviewed psychiatric and mental health nursing journals, covering 2011 through 2015, was to determine the number and types of intervention studies within the specified review period. For consistency, the same criteria for selecting the intervention studies that were described in the previous review ( Zauszniewski et al., 2012 ) were applied: A study was determined to be an intervention study if nursing strategies, procedures, or practices were examined for effectiveness in enhancing or promoting health or preventing disability or dysfunction ( Kane, 2015 ).

Five peer-reviewed nursing journals, regarded as the most frequently read in the mental health nursing profession, were analyzed for the years 2011 through 2015. The journals included in the analysis were Archives of Psychiatric Nursing ; Issues in Mental Health Nursing ; Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Associatio n; Journal of Psychosocial and Mental Health Services; and Perspectives in Psychiatric Care .

Journals were reviewed for the type of intervention study (qualitative or quantitative); the study domain (biological, psychological, or social); and the number of intervention studies found within the journals. After review, the agreed upon intervention studies were extracted and individually analyzed by the co-authors.

There were 832 databased articles published from January 2011 through December 2015. However, only 115 (14%) evaluated or tested psychiatric nursing interventions. Of these 115 intervention studies, 14 tested interventions with nursing students, nine involved nurses and mental health professionals, while 92 focused on interventions to promote mental health in clients of care.

This section describes the findings from the 115 intervention studies included in the review. The 23 studies that included nursing students, nurses, and mental health professional, and the 92 that involved recipients of mental health services or care are presented in this section. First, the research settings in which the 115 studies were conducted, and descriptions of the targeted populations are described. Next, the 23 studies’ designs, purposes, and findings are discussed in detail. Third, the 92 studies that involved recipients of mental health services or care are presented using the categories of the bio-psycho-social framework. Finally, the type of data (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed) are discussed and presented in the table.

Research Settings Sixty-six of the 115 intervention studies were completed in the United States. Five studies each were done in Australia and United Kingdom. Four each were completed in Korea, China, and Turkey; three each in Norway, Canada, and Iran; and two each in Taiwan, Mexico, Sweden, France, and Netherlands. One study each was conducted in Jordan, Europe, Iceland, Pacific Islands, Thailand, Spain, Greece, and Singapore

Targeted Populations Fourteen of the 115 intervention studies involved interventions with nursing students, while nine studies focused on nurses and mental health professionals. Ninety-two of the studies examined the effect of the intervention on the client. Examples of the studies describing each of these groups are described below.

Fourteen of the 23 nursing intervention studies involved undergraduate nursing students. Nursing students . Fourteen of the 23 nursing intervention studies involved undergraduate nursing students. One study was conducted in Australia regarding consumer participation ( Happell, Moxham, & Plantain-Phung, 2011 ). In this study, researchers investigated whether education programs introducing nursing students to mental health nursing lead to more favorable attitudes towards consumer participation in the mental health setting after completing the mental health component of the nursing program. Study participants were in the first semester of the final year of the Bachelor of Nursing program. The study used a within-subject design using two points (pre-and post-educational program implementation). Results indicated that students demonstrated positive attitudes toward consumer participation even before completing the mental health component. Only marginal and non-significant changes were noted at the post-test stage. The authors concluded that the findings were not surprising given the positive scores recorded at baseline (ceiling effect) ( Happell et al., 2011 ). Another study investigated the effect of pedagogy of curriculum infusion on nursing students’ well-being and the improvement of quality of patients’ care ( Riley & Yearwood, 2012 ).

Pedagogy of curriculum infusion involves instilling the university values and mission with a focus on educating the whole person, and encouraging faculty to translate the core mission of the university into practice in the classroom. this can be accomplished through a variety of courses that provide students with opportunities for contemplation, reflective engagement, and also action through volunteerism, service, and study abroad. The ultimate goal of the study was to encourage critical thinking through reflective exercises and group discussion. Results indicated that students who have experienced the curriculum infusion showed an ability to be self-advocates when discussing their work challenges. Also, they were able to identify specific nursing actions for patient safety; to recognize the patient as a partner in care; and to demonstrate respect for patients' uniqueness, values, and desires as evidenced by case analysis and personal reflections ( Riley & Yearwood, 2012 ).

Three intervention studies explored simulation to see its impact on improving the learning experiences of the nursing students. Three intervention studies explored simulation to see its impact on improving the learning experiences of the nursing students ( Kameg, Englert, Howard, & Perozzi, 2013 ; Kidd, Knisley & Morgan, 2012 ; Masters, Kane, & Pike, 2014 ). Different simulations were used in the three studies; all of them were deemed effective. For example, the results of the study conducted by Kidd and colleagues indicated that undergraduate, mental health nursing students perceived that Second Life® virtual simulation was moderately effective as an educational strategy and slightly difficult as a technical program ( Kidd et al., 2012 ). Also, second degree and traditional BSN students found that a tabletop simulation, which was developed as a patient safety activity and involved checking-in a patient admitted to a psychiatric care unit, was a good learning experience and helpful to prepare students for situations they may experience in the workplace ( Masters et al., 2014 ). The third study used a high-fidelity, patient simulation (HFPS) to assess senior level nursing student knowledge and retention of knowledge utilizing three parallel, 30-item Elsevier Health Education Systems, Inc. (HESITM) Custom Exams. Although students’ knowledge did not improve following the HFPS experiences, the findings provided evidence that HFPS may improve knowledge in students who are at risk (defined as those earning less than 850 on HESI exam). Students reported that they viewed this simulation as a positive learning experience ( Kameg et al., 2013 ).

An additional intervention study used a quasi-experimental design to explore perceptions of student nurses toward nurses who are chemically dependent, using a two-group, pretest–posttest design (prior to formal education and after receiving substance abuse education). Results indicated that the student nurses in this study had positive perceptions about nurses who are chemically dependent before the intervention; and the education program appeared to reinforce their existing attitudes. ( Boulton & Nosek, 2014 ).

Mitchell et al. ( 2013 ) investigated the impact of an addiction training program for nurses consisting of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), and embedded within an undergraduate nursing curriculum, on students’ abilities to apply an evidence-based screening and brief intervention approach for risky alcohol and drug use in their nursing practice. Results indicated that the SBIRT program was effective in changing the undergraduate nursing students’ self-perceptions of their knowledge, skills, and effectiveness in screening and intervening for hazardous alcohol and drug use. Furthermore, this positive perception was maintained at 30-day follow-up ( Mitchell et al., 2013 ).

Luebbert and Popkess ( 2015 ) investigated the impact of an innovative, active-learning strategy using simulated, standardized patients on suicide assessment skills in a sample of 34 junior and senior baccalaureate nursing students. Additionally, Schwindt, McNelis, and Sharp ( 2014 ) evaluated a theory-based educational program to motivate nursing students to intervene with persons having serious mental illness. Other intervention studies among nursing students focused on improving students' interpersonal relationships; communication competence; empathetic skills; and confidence in performing mental health nursing skills among nursing students ( Choi, Song, & Oh, 2015 ; Choi & Won, 2013 ; Fiedler, Breitenstein, & Delaney 2012 ; Ozcan, Bilgin, & Eracar, 2011 ; Stiberg, Holand, Ostad, & Lorem, 2012 ).

Nursing staff and mental health professionals . Interventions among the nursing staff and mental health professionals accounted for nine of the nursing intervention studies. The majority of these studies were nursing interventions to educate the nursing staff. Educational interventions included: training videos ( Irvine et al., 2012 ); a continuing education course on suicide awareness ( Tsai, Lin, Chang, Yu,& Chou, 2011 ); an education program using simulation ( Usher et al., 2014 ; Wynn, 2011 ); an educational workshop ( White, Hemingway, & Stephenson, 2014 ); training on family-centered care ( Wong, 2014 ); and the impact of the completion of a 26-week trial on nursing staff’s experience for working as a cardio-metabolic health nurse ( Happell et al., 2014 ).

Terry and Cutter ( 2013 ) used a mixed methods pilot study to evaluate the effect of education on confidence in assessing and addressing physical health needs following attendance at a module titled “Physical Health Issues in Adult Mental Health Practice.” The majority of the participants had studied at the university during the previous five years, at either the diploma or the degree level. Results showed improvement in confidence scores for all study participants following the module; participants were able to identify new knowledge and perspectives for practice change.

Results indicated that care zoning increased the nursing team’s capacity to share information and to communicate patients’ clinical needs... Finally, the study conducted by Taylor and colleagues ( 2011 ) used a pragmatic approach to increase understanding of the clinical-risks needs in acute in-patient unit settings. Each patient was classified according to three zoning levels using a traffic light system: red (high level of risk), amber (medium/moderate level of risk), and green (low level of risk). The level of risk was based on multiple factors including clinical judgment and team discussion ( Taylor et al., 2011 ). Results indicated that care zoning increased the nursing team’s capacity to share information and to communicate patients’ clinical needs, as well as to enhance their abilities to address complex clinical presentation and to seek support when needed.

Intervention Domains

Ninety-two of the studies examined the effect of an intervention for the client. In the following section, we will describe the intervention domains of these 92 articles and provided examples. Additional detail is included in the Table .

Interventions in the Biological Domain Eight interventions were in the biological domain. Study interventions included yoga, dancing, diet, medication, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), exercise, walking, and educational intervention on metabolic syndrome. Four interventions used various kinds of exercises, including walking ( Beebe, Smith, Davis, Roman, & Burke, 2012 ); dancing ( Emory, Silva, Christopher, Edwards, & Wahl, 2011 ); yoga ( Kinser, Bourguigion, Whaley, Hauenstein, & Taylor, 2013 ); and group exercise program ( Stanton, Donohue, Garnon, & Happell, 2015 ). Diet was also used as an intervention. For example, Lindseth, Helland, and Caspers ( 2015 ) used dietary intake of a high or low tryptophan diet as an intervention. Results indicated improvement in patients’ mood, depression, and anxiety for those consuming a high tryptophan diet as compared to those who consumed a low tryptophan diet ( Lindseth et al. 2015 ). A third category within the biological domain was the use of medications as an intervention. One study tested the use of different psychotropic medications for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia ( Zhou et al., 2014 ). A second used ECT as a treatment modality and measured scores on the Montgomery Asberg (MA) Depression Rating Scale before and after the course of treatment ( Pulia, Vaidya, Jayaram, Hayat, & Reti, 2013 ). A final category was an educational program on metabolic syndrome provided to mental health counselors who performed intake assessments on patients newly admitted to two outpatient mental health facilities. ( Arms, Bostic, & Cunningham, 2014 ). Prior to the intervention, neither facility screened for metabolic syndrome at intake or referred patients with a body mass index (BMI) >25 for medical evaluation. Following the intervention, 53 of 132 patients had a documented BMI >25, and 47 of 53 patients were referred to a primary care provider for evaluation. These findings suggested that screening for metabolic syndrome and associated illnesses will increase the rate of detection of chronic conditions ( Arms et al., 2014 ).

Interventions in the Psychological Domain ...the psychological domain had the largest number of intervention studies. Compared to the other domains, the psychological domain had the largest number of intervention studies. Twenty-four of the 92 total intervention studies extracted were in the psychological domain. The intervention studies in the psychological domain included emotion, behavior, and cognition (e.g., counseling) in addition to studies that focused on behavior therapy and psychoeducational programs. Examples of psychological domains studies included: counseling regarding tobacco cessation treatment ( Battaglia, Benson, Cook, & Prochazka, 2013 ); counseling regarding sexual assault ( Lawson, Munoz-Rojas, Gutman, & Siman, 2012 ); resourcefulness training intervention for relocated older adults ( Bekhet, Zauszniewski, & Matel-Anderson, 2012 ); and resilience training and cognitive therapy in women with symptoms of depression aged 18-22 years of age ( Zamirinejad, Hojjat, Golzari, Borjali, & Akaberi, 2014 ) Please see the Table for further details.

One study utilizing an intervention from the psychological domain examined a brief, six- session, cognitive-behavioral intervention among patients with alcohol dependence and depression. The researchers used a quasi-experimental design with a control group and pretest, posttest, and follow-up assessments. Results indicated that the mean depression scores decreased significantly in both the experimental (n = 33) and control groups (n = 27) at the one-month follow-up (Week 7). However, only the experimental group showed significant differences in their mean depression scores between pre- and posttest. At Week 7, the experimental group showed significantly lower mean depression scores than the control group ( Thapinta, Skulphan, & Kittrattanapaiboon, 2014 ).

Interventions in the Social Domain The social domain considers the patients’ environment and its impact on patients’ adjustment and responses to stress. Nine studies involved use of the social domain in their interventions. The social domain considers the patients’ environment and its impact on patients’ adjustment and responses to stress. Interventions in this domain included family, friends, and social support, as well as community interactions ( Zauszniewski et al., 2012 ). One example of an intervention in the social domain involved studying the long-term impact of safe shelter and justice services on abused women’s ability to function after receiving services ( Koci, 2014 ). Another example of an intervention study in the social domain was a pilot, randomized, controlled trial study by Simpson, Quigley, Henry, and Hall ( 2014 ). In this study, the researchers evaluated the selection, training, and support of a group of peer workers recruited to provide support to service users discharged from acute psychiatric unites in London, comparing peer support with usual care ( Simpson et al., 2014 ) (see Table ). A third example in the social domain was designed to help participants successfully transfer from hospitals to the community by enhancing staff participation, creating/maintaining supportive ward milieus, and supporting managers throughout the implementation process ( Forchuk et al., 2012 ).

The study conducted by Horgan, McCarthy, and Sweeny ( 2013 ) was another example of research in the social domain. This study included designing a website for people ages 18-24 who were experiencing depressive symptoms. The website provided a forum to allow participants to offer peer support to each other; it also provided information on depression and links to other supports ( Horgan et al., 2013 ).

Combinations of the Domains Many studies used more than one domain as interventions. Many studies used more than one domain as interventions (see Figure ). Almost half (49%) of the 92 reviewed studies (n = 45) tested an intervention that included two domains. Thirty studies were psychosocial, twelve were biopsychological, and three were biosocial. In addition, six studies (7%) tested intervention with all three domains (biopsychosocial). In the following section, one study from each combination will be described. Again, additional information is provided in the Table .

Figure. Psychiatric Nursing Interventions: Examples of Domains and Their Total Numbers

Iskhandar Shah and colleagues ( 2015 ) studied and tested an intervention from the biopsychological domain using a single-group, pretest–posttest, quasi-experimental research design. Their intervention program included three daily, one-hour sessions incorporating psychoeducation and virtual-reality-based relaxation practice in a convenience sample of twenty-two people with mental disorders. Results indicated that those who completed the program had significantly lowered subjective stress, depression, and anxiety, along with increased skin temperature, perceived relaxation, and knowledge ( Iskhandar Shah et al., 2015 ).

Pedersen, Nordaunet, Martinsen, Berget, and Braastad ( 2011 ) studied an intervention from the biosocial domain. Their intervention program tested the impact of a 12-week, farm-animal-assisted intervention consisting of work and contact with dairy cattle, on levels of anxiety and depression in a sample of fourteen adults diagnosed with clinical depression. The twice-a-week program involved video recording each participant twice during the intervention. Participants were given the choice of either choosing their work tasks with animals (e.g., milking, feeding, hand feeding, moving animals) or the choice of spending their time in contact with farm animals (e.g., patting, stroking, and other non-work-related physical contact). Results indicated that levels of anxiety and depression decreased, and self-efficacy increased during the intervention. Interaction with farm animals (social) via work tasks showed a greater potential for improved mental health than merely animal contact, but only when progress in working skills (biological aspect) was achieved, indicating the role of coping experiences for a successful intervention. ( Pedersen et al., 2011 ).

The NP often accompanied the participant to medical and mental health appointments... Chandler, Roberts, and Chiodo ( 2015 ) conducted a study in the psychosocial domain that examined the feasibility and potential efficacy of implementing a four-week, empower-resilience intervention (ERI) to build resilience capacity with young adults who have identified adverse childhood experiences. The intervention included using mindfulness-based stress reduction (psychological domain) and social support with guided peer and facilitator interaction (social domain). The study randomly assigned a purposive sample of female undergraduate students between the ages of 18 and 24 years of age into two groups: intervention (n = 17) and control (n = 11), and used a pretest–posttest design to compare symptoms, health behaviors, and resilience before and after the intervention program. Results indicated that subjects in the intervention group reported greater building of strengths, reframing resilience, and creating support connections as compared with the control group ( Chandler et al., 2015 ).

Interventions in the biopsychosocial domain include all three components (biological, psychological, and social). There were six studies that included all three domains in their interventions. Hanrahan, Solomon, and Hurford ( 2014 ) used a randomized controlled design to deliver a transitional care model (TCM) intervention to patients with serious mental illness who were transferring from hospital care to home. The intervention group (n = 20) received the TCM intervention delivered by a psychiatric nurse practitioner (NP) for 90 days post hospitalization and the control group (n = 20) received the usual care. The intervention by the nurse practitioner included helping the patients adapt to the home by focusing on managing problem behaviors and physical problems, managing risk factors to prevent further cognitive or emotional decline, promoting adherence to therapies, and integrating physical and mental care approaches. The NP often accompanied the participant to medical and mental health appointments to facilitate communication, translate information to specialty providers, and advocate for the participant ( Hanrahan et al., 2014 ).

Table. Research Classifications by Domains, Design, and Type of Data Used

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Beebe et al. ( ) | Walking program | Self-efficacy for exercise was significantly higher in experimental participants than in controls after intervention. | Random assignment, researchers blinded, pre-/ posttest | Quantitative | Biological |

| Emory et al. ( ) | Line dancing program | The fall rate post intervention was 2.8% compared with 3.2% before intervention. | Pretest-posttest | Quantitative | Biological |

| Kinser, Bourguignon, Taylor, & Steeves ( ) | 8-week yoga intervention | Yoga served as a self-care technique for the stress and ruminative aspects of depression. Yoga facilitated connectedness and helped in sharing experiences in a safe environment. | Qualitative data through daily logs in which participants documented their feelings before and after daily home yoga practice. | Qualitative | Biological |

| Stanton et al. ( ) | Evaluate satisfaction with inpatient group activities designed to assist with recovery, including cognitive behavioral therapy, creative expression, relaxation, reflection/ discussion, and exercise. | More inpatients (50%) rated exercise as “excellent” compared with all other activities. Nonattendance rates were lowest for cognitive behavioral therapy (6.3%), highest for the relaxation group (18.8%), and for the group exercise program (12.5%). | Site evaluation upon discharge; evaluation survey was completed anonymously. | Quantitative | Biological |

| Lindseth et al. ( ) | Dietary intake of high or low tryptophan diet. | Improvement in patients’ mood, depression, and anxiety for those consuming a high tryptophan diet as compared to those who consumed a low Tryptophan. | Within-subjects crossover-designed study, random assignment to control /experimental | Quantitative | Biological |

| Zhou et al. ( ) | Examine the predictive value of time-based prospective memory (TBPM) and other cognitive components for remission of positive symptoms in first episode of schizophrenia. | Higher scores, reflecting better TBPM, at baseline were more likely to achieve remission after 8 weeks of optimized antipsychotic treatment. | Random assignment, pretest-posttest | Quantitative | Biological |

| Pulia et al. ( ) | ECT technique. Two changes were introduced: (a) switching the anesthetic agent from propofol to methohexital, and (b) using a more aggressive ECT charge dosing regimen for right unilateral (RUL) electrode placement. | Compared with patients receiving ECT with RUL placement prior to the changes, patients who received RUL ECT after the changes had a significantly shorter inpatient Length of stay (27.4 versus 18 days, p = 0.028). | A retrospective analysis was performed on two inpatient groups treated on Mood Disorders Unit. | Quantitative | Biological |

| Arms et al. ( ) | Education session about metabolic syndrome for clinicians. | No difference in educational pre-posttest scores. Clinicians increased referral to Primary Care Provider for BMI >25. | Pretest/posttest, chart audit | Quantitative | Biological |

| Battaglia et al. ( ) | Counseling regarding tobacco cessation treatment designed to increase patient engagement while hospitalized. | The intervention had minimal impacts on internalized stigma and personal recovery. Peer support demonstrated positive effects on internalized stigma and personal recovery. | Pilot study, single group, unblinded intervention trial | Quantitative and Qualitative | Psychological |

| Lawson et al. ( ) | “Men's Program”- rape prevention intervention. | Promising change in attitudes about rape beliefs and bystander behaviors in Hispanic males exposed to the educational intervention. | Exploratory study, mixed methods design, pre- and post-test, focus group transcription thematic coding | Quantitative and Qualitative | Psychological |

| Bekhet, Zauszniewski, & Matel-Anderson ( ) | Resourcefulness training (RT) for relocated older adults assessing necessity, acceptability, feasibility, safety and effectiveness of RT. | 76.3% of the older adults scoring below 120, indicating a strong need for RT. Participants indicated acceptability, feasibility, safety, and effectiveness with recommendations for intervention improvement. | Pilot study, random assignment, convenience sample | Quantitative and Qualitative | Psychological |

| Zamirinejad, Hojjat, Golzari, Borjali, & Akaberi ( ) | Resilience training and cognitive therapy for young women with depression | The resilience training group and cognitive therapy group showed a signiï¬cant decrease in the average depression score from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up. There was no signiï¬cant difference between effectiveness of resilience training and cognitive therapy on depression but there was a signiï¬cant difference between these two treatment groups and the control group. | Three-group design with control, pretest- posttest | Quantitative | Psychological |

| Thapinta, Skulphan, & Kittrattanapaiboon ( ) | Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy intervention to reduce depression among alcohol-dependent individuals | The mean depression scores decreased signiï¬cantly in both the experimental and control groups at the one-month follow-up. However, only the experimental group showed signiï¬cant differences in their mean depression scores between pre-and posttest. At Week 7, the experimental group showed signiï¬cantly lower mean depression scores than the control group. | Quasi-experimental, control group, pretest/ posttest design | Quantitative | Psychological |

| Koci et al. ( ) | shelter and justice services for abused women | At 4 months following a shelter stay or justice services, improvement in all mental health measures; however, improvement was the lowest for PTSD. minimum further improvement at 12 months. | Prospective study | Quantitative | Social |

| Simpson et al. ( ) | peer support workers for inpatient aftercare | Participants indicated that the training was valuable, challenging, yet positive experience that provided them with a good preparation for the role. | Pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT), focus groups | Quantitative and Qualitative | Social |

| Forchuk et al. ( ) | Transitional Relational Model (TRM) was used to help mental health clients transitioning from a psychiatric hospital setting to the community. Strategies included enhancing staff participation, creating/ maintaining supportive ward milieus. | Group C implemented the TRM model significantly quicker than the other groups. | Randomized controlled trial; compared three groups of hospital wards; Group A wards had already adopted the TRM, Group B wards implemented the TRM in Year 1, and Group C wards implemented the TRM in Year 2. | Quantitative | Social |

| Horgan, McCarthy, & Sweeney ( ) | online peer support for young adults experiencing depressive symptoms | No statistical significance difference pre- and post-test. The forum posts revealed that the participants' main difficulties were loneliness and perceived lack of socialization skills. The website provided a place for emotional support. | Mixed method, involving quantitative descriptive, pre- and post-test and qualitative descriptive designs | Quantitative and Qualitative | Social |

| Iskhandar Shah et al. ( ) | Virtual reality (VR)-based stress management (VR DE-STRESS) program for people with mood disorders | Those who completed the program had significantly lowered stress, depression, anxiety. | Single-group, pretest–posttest, quasi-experimental research design and convenience sample | Quantitative and Qualitative | Bio-psychological |

| Pedersen et al. ( ) | Farm animal-assisted intervention consisting of work and contact with dairy cattle | Levels of anxiety and depression decreased, and self-efficacy increased during the intervention. | Pretest-posttest, video recording thematic coding | Quantitative and Qualitative | Bio-Social |

| Chandler et al ( ) | Empower resilience intervention (ERI) to build resilience | Subjects in the intervention group reported building strengths, reframing resilience, and creating support connections. | Purposive sampling, random assignment, intervention and control, pretest-posttest design | Quantitative and Qualitative | Psychosocial |

| Hanrahan et al. ( ) | Transitional care model (TCM) intervention to patients with serious mental illness transferring from hospital care to home | Emergency room use was lower for intervention group but not statistically significant. Continuity of care with primary care appointments were significantly higher for the intervention group. The intervention group's general health improved but was not statistically significant compared with controls. | Randomized controlled trial | Quantitative | Bio-psychosocial |

Discussion

Although substantial progress is being made to develop and test interventions for persons with psychiatric and mental health challenges and their families, there remains much work to be done. Nurse scientists and practitioners share a professional obligation to persons entrusted to their care, which includes providing the highest quality care grounded in solid empirical evidence ( Willis, Beeber, Mahoney, & Sharp, 2010 ). This review yields evidence for the continued dissemination of findings from intervention studies from 2011 through 2015. To perform the analysis reported here, we employed methods that were similar to those used for amassing information from the intervention studies in two previous reviews ( Zauszniewski et al., 2007 ; Zauszniewski et al., 2012 ) in order to facilitate comparisons over time.

... the continued publication of evidence from countries outside the United States remains important... During the review period (2011-2015), 57% of the published intervention studies took place in the United States (U.S.) while 43% were conducted outside the U.S. (i.e., internationally). These percentages compare with 72% and 54% of published U.S. intervention studies and 28% and 46% published international intervention studies in the 2000-2005 and 2006-2010 reviews, respectively. The somewhat lower percentages (28% and 46%) of international intervention studies within the current time frame (2011-2015) may indicate a need for more descriptive research to identify distinguishing characteristics of international populations and important phenomena that may be amenable to intervention prior to the systematic testing of interventions. However, the continued publication of evidence from countries outside the United States remains important for developing globally relevant interventions for psychiatric nursing practice.

...there have been dramatic increases through the years in the overall number of studies that have tested interventions that tap more than one domain. Of the 115 intervention studies from 2011 through 2015 found in the five journals, nurses, student nurses, nursing staff, or other mental health professionals were the intervention recipients in 23, representing 20% of the intervention studies. This percent is higher than the 14% reported in the previous review conducted from 2006 through 2010, indicating a slightly greater focus on testing interventions in mental health care professionals in recent years. Although the interventions tested in these populations are not focused directly on outcomes for clients with mental health issues, promoting or preserving the mental health of professional caregivers most certainly affects those for whom they provide care.

Analysis of published intervention studies in the 5-year interval from 2011 through 2015 revealed an increase in the number of studies of psychiatric patients or clients in the five selected journals. For this time frame, we found 92 intervention studies in comparison with 71 from 2006 through 2010 and 77 from 2000 through 2005, which reflect 5 and 6-year intervals respectively.

We also noted fewer intervention studies where all three domains were integrated within the intervention... Moreover, there have been dramatic increases through the years in the overall number of studies that have tested interventions that tap more than one domain. For example, 33% of intervention studies from 2011 through 2015 tested psychosocial interventions, compared to 17% in the previous review (2006-2010) and 12% in the one prior to that (2000-2005). In addition, 13% of the studies from 2011 through 2015 tested biopsychological interventions compared with 4% and 5% in the previous two reviews. However, there was a slightly lower percent of biosocial intervention studies, specifically 3% in comparison with 4% from 2000-2005 and 6% from 2006-2010. We also noted fewer intervention studies where all three domains were integrated within the intervention, specifically only 6% in comparison with 17% in the previous time frame (2006-2010). Yet, our review revealed a larger percent of biopsychosocial intervention studies than from the review conducted from 2000-2005 (1%). Despite the lower number of studies that integrated all three intervention domains, there was an overall trend toward testing interventions that were not restricted only to one domain, indicating increased attention toward more holistic interventions.

... the overall trend shows a lesser focus on testing interventions within a single domain over time... There were 41 intervention studies between 2011 and 2015 that focused solely on one domain. With the exception of the biological domain (9%), interventions within the psychological (26%) and social (10%) domains were fewer than in previous reviews. For example, there has been a clear downward trend in the percent of psychological intervention studies over time with 57% from 2000-2005 to 38% from 2006-2010 and 26% in this current review. Intervention studies within the social domain decreased from 17% in 2006-2010 to 10% in this review. Studies of interventions in the biological domain have fluctuated over time from 11% in 2000-2005 down to 1% from 2005-2010 and up to 9% in the review reported here. However, the overall trend shows a lesser focus on testing interventions within a single domain over time, pointing perhaps to a growing interest in determining effective interventions that are multifaceted and target multiple factors that affect a person’s health.

Implications: Research Needed

The mind and body do not function independently of each other; therefore, when considering the focus of nursing research, we need to target both systems. Nursing has as its foundation a holistic approach to patient care. At this point in our history as we build a knowledge base, a multifaceted approach is needed when planning nursing research. This study of nursing interventions in our research has explored the biological, psychological, and social domains. Studies in the biopsychosocial domain would benefit our knowledge base and improve the criteria for more accurate, evidence-based nursing interventions.

Medicine has increasingly focused on the mental health component of medical illnesses. Nursing research would be strengthened by focusing on the possibility of medical illness and its relationship to mental illness. This nursing research approach'‹ would support our holistic philosophy of care and increase our knowledge of the whole person. It would provide the best evidence-based approach to planning treatment. In addition, it would serve to increase the sphere of psychiatric nursing beyond the psychiatric unit in health care settings.

...an increase in multicultural studies is needed to further strengthen our evidenced based practice. Finally, an increase in multicultural studies is needed to further strengthen our evidenced based practice. The individual person is complex. Identified culture provides important information as to how patients view health and illness. This information is an important component when planning our evidenced based care and should not be isolated from the patient presentation.

Tracking the progress in intervention research relevant for psychiatric and mental health nursing practice is essential to identify evidence gaps. This current, systematic review of intervention studies published in the most accessible psychiatric and mental health nursing journals for practicing nurses, educators, and researchers in the United States has revealed a somewhat lower number of studies from outside the United States; a slightly greater focus on studies of nurses, nursing students, or other mental health professionals as compared with clients who receive their care or services; and a continued trend for testing interventions that captured more than one dimension. Tracking the progress in intervention research relevant for psychiatric and mental health nursing practice is essential to identify evidence gaps. Though substantial progress has been made through the years, there is still room to grow.

Abir K. Bekhet, PhD, RN, HSMI Email: [email protected]

Jaclene A. Zauszniewski, PhD, RN-BC, FAAN Email: [email protected]

Denise M. Matel-Anderson, APNP, RN Email: [email protected]

Jane Suresky, DNP, MSN Email: [email protected]

Mallory Stonehouse, MSN, RN Email: [email protected]

Arms, T., Bostic, T., & Cunningham, P. (2014). Educational intervention to increase detection of metabolic syndrome in patients at community mental health centers. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 52 (9), 32-36. doi:10.3928/02793695-20140703-01

Battaglia, C., Benson, S.L., Cook, P.F., & Prochazka, A. (2013). Building a tobacco cessation telehealth care management for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association , 19 (2), 78-91. doi:10.1177/1078390313483314

Beebe, L.H., Smith, K., Davis, J., Roman, M., & Burke, R. (2012). Meet me at the crossroads: Clinical research engages practitioners, educators, students, and patients. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 48 (2), 76-82. doi: 10.1111%2Fj.1744-6163.2011.00306.x

Bekhet, A.K., Zauszniewski, J.A., & Matel-Anderson, D.M. (2012). Resourcefulness training intervention: Assessing critical parameters from relocated older adults’ perspectives. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33 (7), 430-435. doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.664802

Boulton, M.A., & Nosek, L. (2014). How do nursing students perceive substance abusing nurses? Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28 (1), 29-34. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2013.10.005

Chandler, G.E., Roberts, S.J., & Chiodo, L. (2015). Resilience intervention for young adults with adverse childhood experiences. The Journal of Psychiatric Nurses Association, 21 (6), 406-416. doi:10.1177/1078390315620609

Choi, Y., Song, E., & Oh, E. (2015). Effects of teaching communication skills using a video clip on a smart phone on communication competence and emotional intelligence in nursing students. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29 (2), 90-95. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.11.003

Choi, Y-J., & Won, M-R. (2013). A pilot study on effects of a group program using recreational therapy to improve interpersonal relationships for undergraduate nursing students. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27 (1), 54-55. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2012.08.002

Emory, S.L., Silva, S.G., Edwards, P.B., & Wahl, L.E. (2011). Stepping to stability and fall prevention in adult psychiatric patients. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 49 (12), 30-36 doi:10.3928/02793695-20111102-01

Fiedler, R.A., Breitenstein, S., & Delaney, K. (2012). An assessment of students’ confidence in performing psychiatric mental health nursing skills: The impact of the clinical practicum experience. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 18 (4), 244-250. doi:10.1177/1078390312455218

Forchuk, C., Martin, M-L., Jensen, E., Ouseley, S., Sealy, P., Beal, G., … Sharkey, S. (2012). Integrating the transitional relationship model into clinical practice. Archives in Psychiatric Nursing, 26 (5), 374-381. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01956.x

Hanrahan, N.P., Solomon, P., & Hurford, M.O. (2014). A pilot randomized control trial: Testing a transitional care model for acute psychiatric conditions. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association , 20 (5), 315-327. doi:10.1177/1078390314552190

Happell, B., Hodgetts, D., Stanton, R., Millar, F., Phung, C.P., & Scott, D. (2014). Lessons learned from the trial of a cardiometabolic health nurse. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 50 (4), 1-9. doi:10.1111/ppc.12091

Happell, B., Moxham, L., &Platania-Phung, C. (2011). The impact of mental health nursing education on undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes to consumer participation. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 (2), 108-113. doi:10.3109/01612840.2010.531519

Horgan, A., McCarthy, G., & Sweeny, J. (2013). An evaluation of an online peer support forum for university students with depressive symptoms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27 (2), 54-55. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2012.12.00

Irvine, A.B., Billow, M.B., Eberhage, M.G., Seeley, J.R., McMahon, E., & Bourgeois, M. (2012). Mental illness training for licensed staff in long-term care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33 (3), 181-194. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.639482

Iskhandar Shah, L.B., Torres, S., Kannusamy, P., Lee Chng, C.M., He, H-G., Klainin-Yobas, P. (2015). Efficacy of the virtual reality-based stress management program on stree-related variables in people with mood disorders: The feasibility of the study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29 (1), 6-13. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.09.003

Kameg, K.M., Englert, N.C., Howard, V.M., & Perozzi, K.J. (2013). Fusion of psychiatric and medical high-fidelity patient simulation scenarios: Effect on nursing student knowledge, retention of knowledge, and perception. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34 (12), 892-900. doi:10.3109/01612840.2013.854543

Kane, C. (2015). The 2014 Scope and Standards of Practice for psychiatric mental health nursing: Key Updates. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 20 (1), Manuscript 1. doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol20No01Man01

Kidd, L.I., Knisley, S.J. & Morgan, K.I. (2012). Effectiveness of a Second Life® simulation as a teaching strategy for undergraduate mental health nursing students. Journal of Psychosocial & Mental Health Services, 50 (7), 3-5. doi:10.3928/02793695-20120605-04

Kinser, P.A., Bourgugnon, C. Taylor, A.G., Steeves, R. (2013). "A feeling of connectedness": Perspectives on a gentle yoga interenvention for women with major depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34 (6), 402-211. doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.762959

Kinser, P.A., Bourguigion, C., Whaley, D., Hauenstein, E., & Taylor, A.G. (2013). Feasibility, acceptability, and effects of gentle Hatha yoga for women with major depression: Findings from a randomized controlled mixed-methods study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27 (3), 137-147. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2013.01.003

Koci, A.F., Cesario, S., Nava, A., Liu, F., Montalvo-Liendo, N., & Zahed, H. (2014). Women’s functioning following an intervention for partner violence: New knowledge for clinical practice from a 7-year study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35 (10), 745-755. doi:10.3109/01612840.2014.901450

Lawson, S.L., Munoz-Rojas, D., & Siman, M.N. (2012). Changing attitudes and perceptions of Hispanic men ages 18-25 about rape and rape prevention. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 22 (12), 864-70. doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.728279

Lindseth, G., Helland, B., & Caspers, J. (2015). The effects of dietary tryptophan on affective disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29 (3), 102-107. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.11.008

Luebbert, R., & Popkess, A. (2015). The influence of teaching method on performance of suicide assessment in baccalaureate nursing students. The Journal of American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 21 (2), 126-133. doi:10.1177/1078390315580096

Masters, J.C., Kane, M.G., & Pike, M.E. (2014). The suitcase simulation: An effective and inexpensive psychiatric nursing teaching activity. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 52 (8), 39-44. doi:10.3928/02793695-20140619-01

Mitchell, A.M., Puskar, K., Hagle, H., Gotham, H.J., Talcott, K.S., Terhorst, L., … Burns, H.K. (2013). Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment: Overview of and student satisfaction with an undergraduate addiction training program for nurses. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 51 (10), 29-37. doi:10.3928/02793695-20130628-01

Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science : IS , 10 , 53. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

Ozcan, N.D., Bilgin, H., & Eracar, N. (2011). The use of expressive methods for developing empathetic skills. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 (2), 131-136. doi:10.3109/01612840.2010.534575

Pedersen, I., Nordaunet, T., Martinsen, E.W., Berget, B., & Braastad, B.O. (2011). Farm animal-assisted intervention: Relationship between work and contact with farm animals and change in depression, anxiety, and self-efficacy among persons with clinical depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 (8), 493-500. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.566982

Proctor, E.K., Landsverk, J., Aarons, G., Chambers, D., Glisson, C., & Mittman, B. (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 36 (1), 24-34 doi:10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4

Pulia, K., Vaidya, P., Jayaram, G., Hayat, M., & Reti, I.M. (2013). ECT treatment outcomes following performance improvement changes. Journal of Psychosocial and Mental Health Services, 51 (11), 20-25. doi:10.3928/02793695-20130628-02

Riley, J.B., & Yearwood, E.L. (2012). The effect of a pedagogy of curriculum infusion on nursing student well-being and intent to improve the quality of nursing care. Achieves in Psychiatric Nursing, 26 (5), 364-63. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2012.06.004

Schwindt, R.G., McNelis, A.M., & Sharp, D. (2014). Evaluation of a theory-based educational program to motivate nursing students to intervene with their seriously mentally ill clients who use tobacco. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28 (4), 277-283. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.04.003

Simpson, A., Quigley, J., Henry, S.J., & Hall, C. (2014). Evaluating the selection, training, and support of peer support workers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52 (1), 31-40. doi:10.3928/02793695-20131126-03

Sorensen, J. L., & Kosten, T. (2011). Developing the tools of implementation science in substance use disorders treatment: applications of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25 (2), 262-268. doi:10.1037/a0022765

Stanton, R., Donohue, T., Garnon, M., & Happell, B. (2015). Participation in and satisfaction with an exercise program for inpatient mental health consumers. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 52 (1), 62-67. doi:10.1111/ppc.12108

Stiberg, E., Holand, U., Olstad, R., & Lorem, G. (2012). Teaching care and cooperation with relatives: Video as a learning tool in mental health work . Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33 (8). doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.687804

Taylor. K., Guy, S., Stewart, L., Ayling, M., Miller, G., Anthony, A., … Thomas, M. (2011). Care zoning a pragmatic approach to enhance the understanding of clinical needs as it relates to clinical risks in acute in-patient unit settings. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 (5), 318-326. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.559570

Terry, J. & Cutter, J. (2013). Does education improve mental health practitioners’ confidence in meeting the physical health needs of mental health service users? A mixed method pilot study. Issues in Mental Health , 34(4), 249-255. doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.740768

Thapinta, D., Skulphan, S., & Kittrattanapaiboon, P. (2014). Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for depression among patients with alcohol dependence in Thailand. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35( 9), 689-693. doi:10.3109/01612840.2014.917751

Tsai, W-P., Lin, L-Y., Chang, H-C., Yu, L-S., & Chou, M-C. (2011). The effects of the gatekeeper suicide-awareness program for nursing personnel. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 47 (3), 117-125. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00278

Usher, K., Park, T., Trueman, S., Redman-MacLaren, M., Casella, E., & Woods, C. (2014). An educational program for mental health nurses and community health workers from Pacific Island countries: Results from a pilot study . Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35 (5), 337-343. doi:10.3109%2F01612840.2013.868963

White, J., Hemingway, S., & Stephenson, J. (2014). Training mental health nurses to assess the physical health needs of mental health service users: A pre- and post-test analysis. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 50( 4), 243-250. doi:10.1111/ppc.12048

Willis, D.G., Beeber, L., Mahoney, J., & Sharp, D. (2010). Strategies for advancing psychiatric-mental health nursing science relevant to practice. Perspectives from the American Psychiatric Nurses Association research council co-chairs. Contemporary Nurse, 34 (2), 135-139

Wong, O.L. (2014). Contextual barriers to the successful implementation of family-centered practice in mental health care: A Hong Kong study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28 (3), 197-199. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.02.001

Wynn, S.D. (2011). Improving the quality of care of veterans with diabetes. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 49 (2), 38-43. doi:10.3928/02793695-20110111-01

Zamirinejad, S., Hojjat, SK., Golzari, M., Borjali, A., &Akaberi, A. (2014). Effectiveness of resilience training versus cognitive therapy on reduction of depression in female Iranian college students. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36 (6), 480-488. doi:10.3109/01612840.2013.879628

Zauszniewski, J.A, Bekhet, A., &Haberlein, S. (2012). A decade of published evidence for psychiatric and mental health nursing interventions. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 17 (3), doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No03HirshPsy01

Zauszniewski, J., Suresky M.J., Bekhet, A., & Kidd, L. (May 14, 2007). Moving from Tradition to Evidence: A Review of Psychiatric Nursing Intervention Studies . Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 12 (2) doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol12No02HirshPsy01

Zhou, F-C., Xiang, Y-T., Wang, C-Y., Dickerson, F., Kryenbuhl, J., Ungari, G.S., … Chiu, H.F.K. (2014). Predictive value of prospective memory for remission in first-episode schizophrenia. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 50 (2), 102-110. doi:10.1111/ppc.12027

May 31, 2018

DOI : 10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No02Man04

https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No02Man04

Citation: Bekhet, A.K., Zauszniewski, J.A., Matel-Anderson, D.M., Suresky, M.J., Stonehouse, M., (May 31, 2018) "Evidence for Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing Interventions: An Update (2011 through 2015)" OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing Vol. 23, No. 2, Manuscript 4.

- Article May 31, 2018 Advancing Scholarship through Translational Research: The Role of PhD and DNP Prepared Nurses Deborah E. Trautman, PhD, RN, FAAN; Shannon Idzik, DNP, CRNP, FAANP, FAAN; Margaret Hammersla, PhD, CRNP-A; Robert Rosseter, MBA, MS

- Article May 31, 2018 Connecting Translational Nurse Scientists Across the Nation—The Nurse Scientist-Translational Research Interest Group Elizabeth Gross Cohn, RN, NP, PhD, FAAN; Donna Jo McCloskey, RN, PhD, FAAN; Christine Tassone Kovner, PhD, RN, FAAN; Rachel Schiffman, RN, PhD, FAAN; Pamela H. Mitchell, RN, PhD, FAAN

- Article May 31, 2018 Translation Research in Practice: An Introduction Marita G. Titler, PhD, RN, FAAN

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2019

Mental health nurses’ attitudes, experience, and knowledge regarding routine physical healthcare: systematic, integrative review of studies involving 7,549 nurses working in mental health settings

- Geoffrey L. Dickens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8862-1527 1 , 2 ,

- Robin Ion 3 ,

- Cheryl Waters 1 ,

- Evan Atlantis 1 &

- Bronwyn Everett 1

BMC Nursing volume 18 , Article number: 16 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

59k Accesses

19 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

There has been a recent growth in research addressing mental health nurses’ routine physical healthcare knowledge and attitudes. We aimed to systematically review the empirical evidence about i) mental health nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of physical healthcare for mental health patients, and ii) the effectiveness of any interventions to improve these aspects of their work.

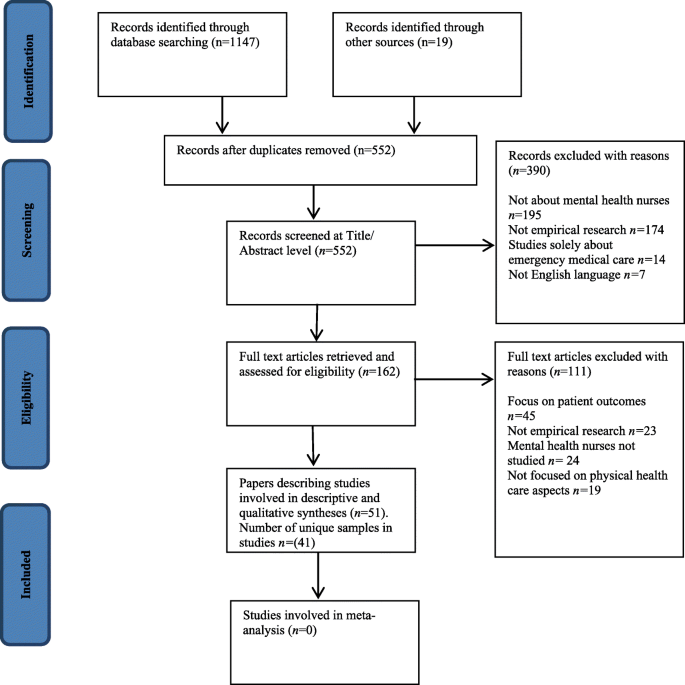

Systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Multiple electronic databases were searched using comprehensive terms. Inclusion criteria: English language papers recounting empirical studies about: i) mental health nurses’ routine physical healthcare-related knowledge, skills, experience, attitudes, or training needs; and ii) the effectiveness of interventions to improve any outcome related to mental health nurses’ delivery of routine physical health care for mental health patients. Effect sizes from intervention studies were extracted or calculated where there was sufficient information. An integrative, narrative synthesis of study findings was conducted.

Fifty-one papers covering studies from 41 unique samples including 7549 mental health nurses in 14 countries met inclusion criteria. Forty-two (82.4%) papers were published since 2010. Eleven were intervention studies; 40 were cross-sectional. Observational and qualitative studies were generally of good quality and establish a baseline picture of the issue. Intervention studies were prone to bias due to lack of randomisation and control groups but produced some large effect sizes for targeted education innovations. Comparisons of international data from studies using the Physical Health Attitudes Scale for Mental Health Nursing revealed differences across the world which may have implications for different models of student nurse preparation.

Conclusions

Mental health nurses’ ability and increasing enthusiasm for routine physical healthcare has been highlighted in recent years. Contemporary literature provides a base for future research which must now concentrate on determining the effectiveness of nurse preparation for providing physical health care for people with mental disorder, determining the appropriate content for such preparation, and evaluating the effectiveness both in terms of nurse and patient- related outcomes. At the same time, developments are needed which are congruent with the needs and wants of patients.

Peer Review reports

People with a mental disorder diagnosis are at more than double the risk of all-cause mortality than the general population. Most at risk are those with psychosis, mood disorder and anxiety diagnoses. Median length of life lost by this group is 10.1 years greater for people with a diagnosis of mental disorder than for general population controls, but mortality rates are significantly higher in studies which include inpatients [ 1 ]. While risk of unnatural causes of death, notably suicide, are greatly increased in this group, it is death from natural causes that remains responsible for the vast majority of mortality. In people with schizophrenia, for example, cardiovascular disease accounts for about one third of all deaths and cancer for one in six, while other common causes are diabetes mellitus, COPD, influenza, and pneumonia [ 2 ]. A relatively high rate of tobacco smoking in this group is implicated in significant increased mortality [ 3 ], as is obesity [ 4 ], exposure to high levels of antipsychotic pharmacological treatment [ 5 ], and mental disorder itself [ 1 ].

Accordingly, the physical health of patients with mental disorder has been prioritised, becoming the focus of guidelines for practitioners in general [ 6 ] and for mental health nurses and other clinical professionals specifically [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. However, while policies and guidelines are necessary prerequisites of change they must also be implemented in practice if they are to have a positive effect; one of the key barriers to change implementation for mental health nurses has been identified as lack of confidence, skills, and knowledge [ 10 ]. Robson and Haddad ([ 11 ]: p.74) identified that surprisingly ‘modest attention’ had been paid to the issue of such attitudes and knowledge among nurses related to their role in physical health care provision, and developed the Physical Health Assessment Scale for mental health nurses (PHASe) in order to further investigate the phenomenon. Since then, there has been a tangible and growing response among mental health nursing academics and practitioners. In recent years, published literature reviews have covered a decade of UK-only research on the role of mental health nurses in physical health care [ 12 ], patients’ and professionals’ perceptions of barriers to physical health care for people with serious mental illness [ 13 ], the focus and content of nurse-provided physical healthcare for mental health patients [ 14 ], and the physical health of people with severe mental illness [ 15 ]. There has also been an upsurge in the amount of related empirical research. However, to date, no one has systematically reviewed this growing literature about mental health nurses’ attitudes towards, or their related knowledge and experience about providing routine physical healthcare. Further, studies about the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve their delivery of or attitudes to routine physical healthcare have not been systematically appraised. This is surprising given the known links between nurses’ attitudes and their implementation of evidence-based practice [ 16 , 17 , 18 ] and the centrality of measuring nurses’ attitudes to physical health care delivery in recent mental health nursing research on the topic [ 11 , 19 , 20 ].

In this context we have conducted a systematic review to identify, appraise, and synthesise existing evidence from empirical research literature about i) mental health nurses’ experience of providing physical healthcare for patients and about their related knowledge, skills, educational preparation, and attitudes; ii) the effectiveness of any interventions aimed at improving or changing mental health nurse-related outcomes; and iii) to identify implications for the future provision of relevant training and education, for policy, research, and practice. The specific review question being addressed therefore is: what is known from the international, English language, empirical literature about mental health nurses’ skills, knowledge, attitudes, and experiences regarding provision of physical healthcare.

A systematic review of the literature following the relevant points of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [ 21 ].

Search strategy

Since the review scope encompassed questions about experience and effectiveness a dual literature search strategy was developed. For studies about mental health nurses’ experience of delivering physical healthcare a Population Exposure Outcome (PEO) format review question was developed (Population: mental health nurses; Exposure: physical healthcare provision for patients or related training; Outcomes: experiential, social, educational, knowledge, or attitudinal terms, see Additional file 1 : Table S1). For studies of the effectiveness of interventions to improve or change mental health nurse-related outcomes a Population Intervention Comparator Outcome (PICO) structure was implemented (Population: mental health nurses; Intervention: any intervention including physical health-related education, policy or guideline change; Comparator: any or none; Outcome: any) [ 22 ]. We searched five electronic databases: i) CINAHL, ii) PubMed, iii) MedLine, iv) Scopus, and v) ProQuest Dissertations and Theses using text words and MeSH terms. The references list of all included studies, together with those of relevant literature reviews, and the tables of contents of selected mental health nursing journals were hand searched. The search terms were informed by previous literature reviews on the subject of physical healthcare in mental health. The initial search was conducted in April 2018 and re-run in September 2018.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for studies were English language accounts of empirical research which investigated mental health nurses’ experience of providing physical health care or examined the effectiveness of any intervention that aimed to improve outcomes related to the provision of physical healthcare. Thus, studies of interventions aimed at changing nursing practice, behaviour, knowledge, attitudes, or experiences were eligible, but not those which solely attempted to determine the effect of an intervention on nurses in terms of patient outcomes. While improvement in patient care and outcomes is clearly the desirable endpoint of any intervention on nurses, previous reviews have indicated that no good quality studies exist [ 23 ]. Additionally, studies were only eligible for inclusion where the practitioners involved comprised or included mental health or psychiatric nurses or mental health nursing students, or registered nurses whose practice was within mental health services. Included studies could have used any design or methodological approach. As in previous reviews, studies solely about mental health nurses providing care for people with alcohol/ drug misuse, or mental disorder/substance misuse dual diagnosis were not eligible. Studies about mental health nurses and the provision of emergency physical care or of their experience of providing care for the seriously deteriorating physical health of a patient were omitted as this is the subject of a separate review (Dickens et al. submitted).

Data extraction

Information about the study title, author, publication year, data collection years, location (country), research objectives, aims or hypotheses, design, population, sample details and size, data sources, study variables (i.e. details of intervention) or other exposure, unit of analysis, and study findings were extracted from full text papers. Corresponding authors of included studies were contacted regarding any issues where clarification or additional data could aid the review.

Studies were categorised as interventional or observational. Intervention studies investigated the impact of an educational, policy, or practice intervention in terms of any mental health nurse- or nursing- related outcome, e.g., knowledge, attitudes, behaviour. Intervention studies were further sub-classified as simulation studies (as defined by Bland et al. ([ 24 ]: p.668) “a dynamic process involving the creation of a hypothetical opportunity that incorporates an authentic representation of reality, facilitates active student engagement and integrates the complexities of practical and theoretical learning with opportunity for repetition, feedback, evaluation and reflection”), traditional educational interventions (e.g., lectures, workshops, workbooks), or policy-level interventions (e.g., requiring nurses to follow some new policy or implement some new practice). Observational studies either described mental health nurse- or nursing- related outcomes and/or utilised case control designs to compare them with those of other occupational or professional groups and/or used qualitative methods.

Study quality appraisal

The likelihood of bias in intervention studies was assessed against criteria described by Thomas et al. [ 25 ] and encompassed assessment of the likelihood of selection bias in the obtained sample, study design, potential confounders, blinding, potential for bias in data collection from invalid instrumentation, and participant retention (see Additional file 2 : Table S2). Relevant items from the US Department of Health & Human Sciences NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [ 26 ] were used to assess cross-sectional observational studies (see Additional file 3 : Table S3). Qualitative descriptive studies were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [ 27 ] tool (See Additional file 4 : Table S4). Multiple papers arising from single studies were quality assessed as a single entity. Study quality was initially undertaken independently by at least two of the team. A good level of inter-rater agreement was achieved (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.742 between pairs of raters). Disputed items were discussed by GD and CW and consensus achieved.

Study synthesis

The available total and subscale data from those studies that conducted data collection via the Physical Healthcare Attitude Scale for mental health nurses (PHASe [ 11 ]), the only scale used across more than two studies, was tabulated and compared across studies using unpaired t-tests in QuickCalcs GraphPad software. Where individual item mean and dispersion scores were unavailable estimates were calculated as follows: the mean mean (i.e., Σ means / n means) and the estimated standard deviation (the square root of the average of the variances [ 28 ]). Also, and where available, dichotomised data (‘Strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ responses versus all other responses) from the multiple studies using the 14-item PHASe scale investigating self-reported current involvement in aspects of physical healthcare was tabulated and subjected to Chi-squared analysis. Significant cross-study differences of means and proportions involved all subscale or item data for each study being compared with the corresponding subscale or item from the original study development sample, ‘the reference group’ [ 11 ].

Where available, effect sizes for correlational, interventional, or difference-related outcomes from studies were extracted or, where sufficient information presented, calculated. Where sufficient information was not presented we attempted to contact the corresponding author for clarification. Appropriate effect size statistics were calculated using an online resource [ 29 ]. All other information from study results was subject to a qualitative synthesis conducted by author 1 and subsequently refined and agreed by all of the authors.

Study settings and participants