How to Achieve a Good Life? Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

A good life, moral virtues.

Life is a mode of existence and it reflects the experiences of living that characterize human beings whether they are good or bad. It is confounding to describe what a good life is, since it applies to both material life and moral life. For instance, having immense wealth and ability to enjoy every form of pleasure that ever existed on earth can mean that one is living a good life.

On the other hand, living in accordance with the social, religious, and personal morals and ethics means that one is also living a good life. The latter description of good life applies across the board since everybody has the ability to achieve it for everyone has the capacity to think and act morally. This essay explores what a good life is and describes plan of achieving it in terms of integrity, honesty, responsibility, and state obligation.

Living a good life morally means living in accordance with the ethics and morals of the society. A person living a good life expresses virtues such integrity, honesty, responsibility, and obligation to the rules of the state. Although human beings pursue material and intellectual gains as they struggle towards self-actualization, these gains cannot earn them the virtue of being good, but they will rather pass for hardworking individuals.

The rich people have wealth because of their hardworking character and they can access good things of life that bring happiness and pleasure, and live a good life materially; nevertheless, this does not make them good. A poor person can live a miserable life of poverty but with good moral life, while on the contrary, a rich person can live a good life of pleasure and happiness, but with bad moral life. Therefore, when “good” describes virtues, pleasure and happiness due to money cannot make life good.

Morals and ethics that individuals observe to express virtues in life cause them to lead a good life. Integrity and honesty are two virtues that enhance people’s lives and they are inseparable because one cannot have integrity without being honesty or vice versa. Educationally, integrity is a skill that demands learning and continued practice in order to internalize the virtue.

The development of integrity is a life-long process that needs patience and endurance since it is a skill. If likened to a building, honesty and truth are two central pillars that support integrity as a virtue throughout the life of an individual. To develop this virtue of integrity in life, one must always adhere to its two pillars, because integrity is not a discrete achievement but a continuous achievement that needs constant efforts to maintain it.

Responsibility is a powerful virtue which if exercised well by an individual, it does not only yield great benefits to the individual, but also to other people and the entire society. The golden rule demands that there must be reciprocal responsibility in the society to enable people live harmoniously.

Sense of responsibility in the society lessens the impacts of problems experienced because of collective response that lead to immediate solution. Becoming part of the solution in the society is being responsible and the excuse of blaming others would not arise. Since rights and responsibility relate to one another, it requires one to act within the limits of rights to become responsible. Therefore, the rights that govern social norms and regulations give one the degree of responsibility to struggle and attain good life for the benefit of all.

Citizens have a moral obligation to respect and advocate for the common interests of all people. For justice and peace to flourish in the society, citizens have great moral obligation to ensure they report criminal activities, help the poor, and conserve the environment. By doing this, they foster their states’ bid to build justice and a peace in society where virtues spring up, and thus a good life.

Like responsibility, adherence to the laws of the land will enable one to develop a sense of obligation to the state. It is a great obligation of the citizens to help the state fight vices in the society and the best way to do it is by becoming loyal to the laws and being active in enforcing them. The concerted efforts of the state and its citizens will improve the lives of the people resulting into a good life.

To achieve good life based on observance of moral principles demands strict observance and application of ethics in everything. Complete observance of ethics yields virtues that make life good in any community.

The goodness of a person cannot result from material wealth, but it emerges from the good moral qualities that one has achieved in life. Virtues like integrity, honesty, responsibility, and obligation to the state are attributes of an individual and have no material value attached to them. This means that, a good life does not mean wealthy living.

- Teleological and Deontological Theories of Ethics Definition

- Introduction to the Utilitarianism Theory

- The Importance of Academic Honesty

- Aristotle’s Account of Pleasure

- Debate on Drug Legalization: A Matter of Responsibility and Honesty

- Aristotle’s Ethical Theory

- Pro-Life and Pro-Choice Sides of Abortion

- Which is Basic in Ethics: Happiness or Obligation

- The NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct

- Moral Dilemma Between the Right Thing to Do and What Is Good Argumentative

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, August 4). How to Achieve a Good Life? https://ivypanda.com/essays/life/

"How to Achieve a Good Life?" IvyPanda , 4 Aug. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/life/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'How to Achieve a Good Life'. 4 August.

IvyPanda . 2018. "How to Achieve a Good Life?" August 4, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/life/.

1. IvyPanda . "How to Achieve a Good Life?" August 4, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/life/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "How to Achieve a Good Life?" August 4, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/life/.

- Is the Good Life Found in Pursuing Happiness? Words: 733

- The Good Life Overrides the Moral Life Words: 1997

- The Good Life: Meaning and Analysing Words: 645

- “Good Life” From an Ethical Perspective Words: 504

- Philosophy of What Constitutes a Good Life Words: 1529

- Meaningfulness and Meaningless of Life Words: 921

- A Good Parent: Definition and Traits Words: 564

- The “Value Life as It Is” Manifesto Words: 926

- The Human Concept of Happiness and Good Words: 818

- Longevity and Life Expansion Words: 953

- Eternal Life in John’s Gospel: Theological Perspective Words: 1381

- The Meaning of Life: A Discussion Words: 1209

Definitions of a Good Life

At all times, philosophers and thinkers have been pondering what the Good Life is. This concept is subjective and can differ for every person because everyone views the world through the lens of their own values, beliefs, and experiences. As for me, the Good Life is the one where you are happy and satisfied with yourself and what you bring into the world. It is a life where you have the inner balance and feel like you are doing the right thing at every given moment. This paper aims to discuss the concepts related to the idea of the Good Life and reflect on what our society should aspire to achieve.

The concept of the Good Life refers to a meaningful and fulfilled life and is interwoven with the concept of a good society, with developed structure, values, and culture. Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle viewed morality, ethics, and flourishment as an integral part of the Good Life for each individual (Hobbs, 2018). Besides, Aristotle believed that people are hardwired to live in a polis or city; hence, he linked politics and social structure with ethics and moral choices (Hobbs, 2018). I agree with this idea and think that as a society, we should focus on growing together and making the world a better place. It can be achieved by managing resources wisely, maintaining sustainability, and providing equity and opportunities for everyone. The community where every individual is guided by morale and ethics is a key to the Good Life, and this is the state our society should aspire to achieve.

I believe our focus should be on sufficiency, equity, development, and improvement to ensure a good society and a good life. This perspective is consistent with the ideas discussed by O’Neill et al. (2018), who suggested strategies to enhance the quality of life and resource use within planetary boundaries. As per the World Health Organization, quality of life is “an individual’s perception of their position in life … in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (as cited in Carlquist et al., 2017, p. 481). Therefore, it seems utopian to attempt to provide the Good Life for everyone as the concept is subjective. For instance, for me, it includes being healthy, feeling comfortable and satisfied with myself, working toward my goals, and continuously growing as a person. At the same time, another person might see the Good Life as one where their basic needs are covered. The view of the universal Good Life suggested by O’Neill et al. (2018) is idealistic. However, with sufficient quality of life, everyone can be closer to their concept of happiness and satisfaction.

Another important concept associated with the Good Life is progress and its impact on society. Progress refers to a movement toward a better state or a higher stage. In this regard, the desire for the Good Life prompts society to evolve and develop. Progress is often defined as economic growth; however, some researchers criticize this perspective. For example, according to Coccia & Bellitto (2018), “the concept is stratified in manifold factors and includes both positive and negative dimensions in society” (p. 1). In other words, several complex factors of social and psychological nature can influence human behavior and, in turn, human progress. I can’t entirely agree with such criticism as I believe that economic growth contributes significantly to the quality of life and should be viewed as one of the primary contributions to the Good Life. For example, providing nations with quality health care, education, and job opportunities is progress as it allows for the improvement of life for individuals and society as a whole. On the contrary, maintaining the same level of living standards cannot be viewed as progress since it does not mean upgrading to a higher stage.

The idea of the Good Life is based on human values, such as equality, equity, and opportunity. Eliminating opportunity gaps in education and jobs is critical to provide more people with a foundation for the Good Life (Jonas & Yacek, 2018). I support this idea even though the ultimate equality seems unachievable in the real world. Nevertheless, we should value freedom and independence, assisting others in order to create a healthier society. Similarly, racial, ethnic, and gender equality needs to be provided, and people need to be protected from violence. I believe that the promotion of social and environmental justice is crucial for ensuring equal treatment for people and the good society.

In this regard, understanding the importance of concepts like progress, equity, and development contributed to my intention to enroll in my degree in Social Science Psychology. I believe that the program will help me develop a better understanding of the diversity and complexity of our society and the world where we live. Thus, I will be able to apply my knowledge to contribute to welfare promotion.

To sum up, different perspectives on the Good Life and ideas related to it are discussed in this paper. Every individual needs to determine their values and aspirations since they largely define a person’s view of the Good Life. A mindful and tolerant approach to organizing our society can help us consider different perspectives of happiness and provide people with equity and opportunities for growth.

Carlquist, E., Ulleberg, P., Delle Fave, A., Nafstad, H. E., & Blakar, R. M. (2017). Everyday understandings of happiness, good life, and satisfaction: Three different facets of well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12 (2), 481-505.

Coccia, M., & Bellitto, M. (2018). Human progress and its socioeconomic effects in society. Journal of Economic and Social Thought , 5 (2), 160-178. Web.

Hobbs, A. (2018) Philosophy and the good life. Journal of Philosophy in Schools, 5 (1), 20-37.

Jonas, M. E., & Yacek, D. W. (2018). Nietzsche’s philosophy of education: Rethinking ethics, equality and the good life in a democratic age . Routledge.

O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F., & Steinberger, J. K. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nature Sustainability , 1 (2), 88-95.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, January 22). Definitions of a Good Life. https://studycorgi.com/definitions-of-a-good-life/

"Definitions of a Good Life." StudyCorgi , 22 Jan. 2022, studycorgi.com/definitions-of-a-good-life/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Definitions of a Good Life'. 22 January.

1. StudyCorgi . "Definitions of a Good Life." January 22, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/definitions-of-a-good-life/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Definitions of a Good Life." January 22, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/definitions-of-a-good-life/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Definitions of a Good Life." January 22, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/definitions-of-a-good-life/.

This paper, “Definitions of a Good Life”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 9, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

What Is The Good Life & How To Attain It

Yet with more than 8 billion people on this planet, there are probably just as many opinions about what the good life entails.

Positive psychology began as an inquiry into the good life to establish a science of human flourishing and improve our understanding of what makes life worth living (Lopez & Snyder, 2011).

We will begin this article by exploring definitions of the good life, before presenting a brief history of philosophical theories of the good life. Then we’ll introduce a few psychological theories of the good life and methods for assessing the quality of life, before discussing how you can apply these theories to live a more fulfilling life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Happiness & Subjective Wellbeing Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify sources of authentic happiness and strategies to boost wellbeing.

This Article Contains:

What is the good life, what is the good life in philosophy, theories about the good life, assessing your quality of life, how to live the good life, positivepsychology.com resources, a take-home message.

The word ‘good’ has a very different meaning for very many people; however, there are some aspects of ‘the good life’ that most people can probably agree on such as:

- Material comfort

- Engagement in meaningful activities/work,

- Loving relationships (with partners, family, and friends)

- Belonging to a community.

Together, a sense of fulfillment in these and other life domains will lead most people to flourish and feel that life is worth living (Vanderweele, 2017).

However, the question ‘what is the good life?’ has been asked in many fields throughout history, beginning with philosophy. Let’s look at where it all began.

According to Socrates

Interestingly enough, the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates never wrote anything down. His student Plato reported his speeches in published dialogues that demonstrate the Socratic method. Key to Socrates’ definition of the good life was that “the unexamined life is not worth living” (Ap 38a cited in West, 1979, p. 25).

Socrates argued that a person who lives a routine, mundane life of going to work and enjoying their leisure without reflecting on their values or life purpose had a life that wasn’t worth living.

Download 3 Free Happiness Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover authentic happiness and cultivate subjective well-being.

Download 3 Free Happiness Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

According to Plato

Plato’s view of the good life was presented in The Republic (Plato, 380-375 BCE/2007) and supported the views of his teacher, Socrates. The Republic examines virtue and the role of philosophy, community, and the state in creating the conditions needed to live well.

In this dialogue, Socrates is asked why a person ought to be virtuous to live a good life, rather than merely appear to be virtuous by cultivating a good reputation. Socrates answers that the good life doesn’t refer to a person’s reputation but to the state of a person’s soul.

The role of philosophy is essential because philosophers are educated in using reason to subdue their animal passions. This creates noble individuals who contribute to a well-ordered and humane society. A person who is unable to regulate their behavior will be unstable and create suffering for themselves and others, leading to a disordered society.

Therefore, educated reason is crucial for cultivating virtuous conduct to minimize human suffering, both individually and socially. For Socrates and Plato, rational reflection on the consequences of our actions is key to establishing virtuous conduct and living the good life, both inwardly and outwardly.

For a fuller account check out the Wireless Philosophy video by Dr. Chris Surprenant below.

According to Aristotle

For Plato’s student Aristotle, the acquisition of both intellectual and character virtues created the highest good, which he identified with the Greek word eudaimonia , often translated as happiness (Aristotle, 350 BCE/2004).

Aristotle believed a person achieves eudaimonia when they possess all the virtues; however, acquiring them requires more than studying or training. External conditions are needed that are beyond the control of individuals, especially a form of state governance that permits people to live well.

It was Aristotle’s option that state legislators (part of Greek governance) should create laws that aim to improve individual character, which develops along a spectrum from vicious to virtuous. To cultivate virtue, reason is required to discern the difference between good and bad behavior.

For more on Aristotle’s version of the good life, click out the Wireless Philosophy video by Dr. Chris Surprenant below.

According to Kant

Immanuel Kant was a Prussian-born German philosopher active during the Enlightenment period of the late 18th century (Scruton, 2001). He is best known for his seminal contributions to ethics, moral philosophy, and metaphysics.

For Kant, a capacity for virtue is unique to human beings, because the ability to resist bodily desires requires the exercise of reason. Kant claims that human reason makes us worthy of happiness by helping us become virtuous (Kant, 1785/2012).

Kant’s argument describes the relationship between morality, reason, and freedom. One necessary condition of moral action is free choice.

An individual’s action is freely chosen if their reasoning determines the right course of action. Conduct is not freely chosen if it is driven by bodily desires like hunger, lust, or fear, or behavioral coercion that applies rewards and punishments to steer human actions.

For Kant, individuals should act only if they can justify their action as universally applicable, which he termed the categorical imperative (Kant, 1785/2012). He argued that all our behavioral choices can be tested against the categorical imperative to see if they are consistent with the demands of morality. If they fail, they should be discarded.

A virtuous person must exercise reason to identify which principles are consistent with the categorical imperative and act accordingly. However, Kant claimed that reason can only develop through education in a civilized society that has secured the external conditions required for an individual to become virtuous.

For example, an individual who lives in fear of punishment or death lacks the freedom required to live virtuously, therefore authoritarian societies can never produce virtuous individuals. Poverty also erodes an individual’s freedom as they will be preoccupied with securing the means of survival.

For a deeper examination of these ideas view the Wireless Philosophy video by Dr. Chris Surprenant below.

According to Dr. Seligman

Dr. Martin Seligman is widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of positive psychology. For Seligman, the good life entails using our character strengths to engage in activities we find intrinsically fulfilling, during work and play and in our relationships.

For Seligman, ‘the good life’ has three strands,

- Positive emotions

- Eudaimonia and flow

Dr. Seligman’s work with Christopher Peterson (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) helped to develop the VIA system of signature strengths . When we invest our strengths in the activities of daily living, we can develop the virtues required to live ‘the good life’; a life characterized by positive emotional states, flow, and meaning.

Here is a video to learn more from Dr. Seligman about how cultivating your unique strengths is essential for living the good life.

Theories about what constitutes the good life and how to live it abound. This section will look at some of the most recent psychological theories about what contributes to the good life.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Set-Point Theory

Set-point theory argues that while people have fluctuating responses to significant life events like getting married, buying a new home, losing a loved one, or developing a chronic illness, we generally return to our inner ‘set point’ of subjective wellbeing (SWB) after a few years (Diener et al., 1999). This is largely inherited and tied in with personality type.

In terms of the Big Five personality traits , those predisposed to neuroticism will tend more toward pessimism and negative perceptions of events, while those who are more extroverted and open to experience will tend more toward optimism.

According to set-point theory, the efforts we make to achieve our life goals will have little lasting effect on our overall SWB given we each have our own ‘happiness set point’ (Lyubomirsky, 2007).

Furthermore, set point theory suggests that there’s little we can do for people who have been through a difficult time like losing their spouse or losing their job because they will eventually adapt and return to their previous set point.

This implies that helping professionals who believe they can improve people’s SWB in the longer term may be misguided. Or does it?

Other research provides evidence that achieving life goals can have a direct effect on a person’s overall contentment (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2021). Specifically, pursuing non-competitive goals such as making a family, building friendships, helping others in our community, and engaging in social justice activities improve our sense of wellbeing.

On the other hand, pursuing competitive life goals like building a career and monetary wealth exclusively undermines SWB.

For set-point theory, the good life depends more on innate personality traits than education. For a surprising account of this, using a practical example, view the video below.

Life-Satisfaction Theory

Typically, life satisfaction refers to a global evaluation of what makes life worth living rather than focusing on success in one area of life like a career or intimate relationship, or the fleeting sense of pleasure we often call happiness (Suikkanen, 2011).

However, there tend to be two dominant theories of what causes life satisfaction: bottom-up theories and top-down theories.

Bottom-up theories propose that life satisfaction is a consequence of a rounded overall sense of success in highly valued life domains . Valued life domains differ from person to person. For a professional athlete, sporting achievement may be highly valued, while for a committed parent having a good partnership and stable family life will be super important (Suikkanen, 2011).

Of course, these are not mutually exclusive. For most people, multiple life domains matter equally. However, if we are satisfied with the areas that we value, a global sense of life satisfaction results (Suikkanen, 2011).

Top-down theories propose that our happiness set-point has a greater influence on life satisfaction than goal achievement. In other words, personality traits like optimism have a positive impact on a person’s satisfaction with life regardless of external circumstances, whereas neuroticism undermines contentment.

The debate continues, and life satisfaction is likely influenced by a combination of nature and nurture as with other areas of psychology (Suikkanen, 2011). You can read an extended discussion of the evidence in our related article on life satisfaction .

So, while life satisfaction is associated with living a good life, it’s not necessarily related to education, the exercise of reason, or the cultivation of virtues as proposed by the philosophers mentioned above. For example, a successful financial criminal may be highly satisfied with life but would be deemed a corrupt human being by such lofty philosophical standards.

Hedonic treadmill

Meanwhile, the concept of the hedonic treadmill proposes that no matter what happens, good or bad, a person will eventually return to their baseline emotional state. For example, if someone gets married, moves to a new home, is promoted, loses a job, or is seriously injured in an accident, eventually, they will default to their innate set point (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012).

This has also been termed hedonic adaptation theory (Diener et al., 2006). It means that no matter how hard we chase happiness or try to avoid suffering, ultimately, our innate tendencies toward pessimism or optimism return us to our baseline level, either dysphoria or contentment (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

If you tend to see the glass as half empty rather than half full, don’t be discouraged, because recent research by Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2021) acknowledges that while we each have a happiness set point, we can also cultivate greater happiness. We’ve offered some tips in the ‘how to’ section below.

Nevertheless, assessing the quality of life has led to an abundance of international research using quality of life indicators (QoLs) in a variety of scales and questionnaires (Zheng et al., 2021).

Gill and Feinstein identified at least 150 QoL assessment instruments back in the mid-1990s (Gill & Feinstein, 1994). Since then, scales have been refined to measure the quality of life in relation to specific health conditions, life events, and demographic factors like age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Zheng et al., 2021).

Our article Quality of Life Questionnaires and Assessments explains this in more detail and guides you on how to choose the best instrument for your clients.

Meanwhile, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ( OECD ) has developed the Better Life Index to measure how people from different demographics define a high quality of life. You can find out more in the brief video below.

How can each of us live the good life today given our array of differences? Below are five steps you can take to clarify what the good life means to you, and how you can apply your strengths to set goals that will lead to greater fulfillment.

1. Clarify your values

Clarifying what is important to you helps invest your life with meaning. Download our values clarification worksheet to get started.

2. Identify valued life domains

Investing in activities in valued life domains is intrinsically rewarding. Download our valued life domains worksheet to find out more.

3. Invest in your strengths

You can find out your character strengths by taking the free survey here . Playing to your strengths helps you overcome challenges and achieve your goals leading to greater life satisfaction. Read our article about how to apply strengths-based approaches to living well.

4. Set valued goals

Finally, we all benefit when we set goals and make practical plans to achieve them. Try our setting valued goals worksheet for guidance.

5. Ensure high-quality relationships

Healthy relationships with partners, family, friends, and colleagues are essential for living the good life and achieving your goals. To assess the quality of your relationships, take a look at our article on healthy relationships with free worksheets.

You can also look at our healthy boundaries article with more free resources. Healthy boundaries support you in living the good life in all life domains, while poor boundaries will leave you feeling unfulfilled.

17 Exercises To Increase Happiness and Wellbeing

Add these 17 Happiness & Subjective Well-Being Exercises [PDF] to your toolkit and help others experience greater purpose, meaning, and positive emotions.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

We have an excellent selection of resources you might find useful for living the good life.

First, take a look at our Meaning & Valued Living Masterclass for positive psychology practitioners. This online masterclass follows a practical process of identifying values, investing in strengths and then applying them to living a more fulfilled life.

In addition, we have two related articles for you to enjoy while exploring the role of meaning in the good life:

- Realizing Your Meaning: 5 Ways to Live a Meaningful Life

- 15 Ways to Find Your Purpose of Life & Realize Your Meaning

Next, we have an article explaining the role of human flourishing in living the good life.

- What Is Flourishing in Positive Psychology? (+8 Tips & PDF)

Finally, we have an article on how to apply values-driven goal-setting to living the good life.

- How to Set and Achieve Life Goals The Right Way

We also have worksheets you may find useful aids to living the good life:

Our How Joined Up is Your Life? worksheet can help your client identify their interests and passions, assess how authentically they are living their life, and identify any values that remain unfulfilled.

This Writing Your Own Mission Statement worksheet can help clients capture what they stand for, their aims, and objectives. Having a personal mission statement can be useful to return to periodically to assess our alignment with our values and goals.

Finally, this How to Get What You Deserve in Life worksheet can help clients identify what they want as well as justify why they deserve a good life.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop strategies to boost their wellbeing, this collection contains 17 validated happiness and wellbeing exercises . Use them to help others pursue authentic happiness and work toward a life filled with purpose and meaning.

We all want to live the good life, whatever that means to us individually. The concept has preoccupied human beings for millennia.

If you currently struggle, which we all do at different times, we hope you’ll consider trying some of the science-based strategies suggested above to steer your way through.

All the evidence we have shared above shows that you can improve your life satisfaction and subjective wellbeing by living in line with your values. But you have to be clear about what’s important to you.

Values-based living invests your life with more meaning and purpose and is key to living the good life.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Happiness Exercises for free .

- Aristotle. (2004). Nicomachean ethics (Tredennick, H & Thomson, J.A.K., Trans.). Penguin. Original work published 350 BCE.

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist , 61(4), 305–314.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin , 125(2), 276–302.

- Gill, T. M., & Feinstein, A. R. (1994). A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements . Jama, 272(8), 619-626.

- Kant, I. (2012). Groundwork of the metaphysics of morals . Cambridge University Press. Original work published 1785.

- Lopez, S. L. & Snyder, C. R. (2011). The Oxford handbook of positive psychology . Oxford University Press.

- Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology , 9, 111–131.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). The how of happiness: A scientific approach to getting the life you want . Penguin.

- Plato. (2007). The Republic (D. Lee, Trans.; 2nd ed.). Penguin. Original work published 380-375 BCE.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

- Scruton, R. (2001). Kant: A very short introduction . Oxford.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). The challenge of staying happier: Testing the hedonic adaptation prevention model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 38(5), 670–680.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2021). Revisiting the sustainable happiness model and pie chart: Can happiness be successfully pursued? The Journal of Positive Psychology , 16(2), 145–154.

- Suikkanen, J. (2011). An improved whole life satisfaction theory of happiness. International Journal of Wellbeing , 1(1), 149-166

- Vanderweele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 114(31), 8148–8156.

- West, T. G. (1979). Plato’s “Apology of Socrates”: an interpretation, with a new translation . Cornell University Press.

- Zheng, S., He, A., Yu, Y., Jiang, L., Liang, J. & Wang, P. (2021). Research trends and hotspots of health-related quality of life: a bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2019. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 19 , 130.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

For me a happy life is having the necessary things to have a good life in the physical aspect, economic aspect ,social aspect, achievement and also family, love and health . The luxuries are also good but they are extra things in life. The most important thing in life is love and peace.

This article made my day. Thank you for putting it together.

I lost approximately 14,000 dollars because of a bank fraud. This money is a product of my hardwork as a nurse and I have been saving it so I have a money when I travel back to be with partner. And the bank refused to refund my money. This incidence has made me feel devastated about life. It affected me emotionally and mentally. But I tried to contain this emotion for a few months and avoided to work and avoided my friends. But I am lucky that my parents, my sisters and especially my partner have been very supportive and understanding to me. They showed me the love and care I needed especially those tough times. Only a few days ago that I realised I should start to help myself and this is why I started to listen to a different talks and read articles that will help me to stay positive in life. Having this article read, it reminded me that I should be grateful that I am surrounded with great people. So thank you for sharing this article and making it accessible to everyone.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Embracing JOMO: Finding Joy in Missing Out

We’ve probably all heard of FOMO, or ‘the fear of missing out’. FOMO is the currency of social media platforms, eager to encourage us to [...]

The True Meaning of Hedonism: A Philosophical Perspective

“If it feels good, do it, you only live once”. Hedonists are always up for a good time and believe the pursuit of pleasure and [...]

Happiness Economics: Can Money Buy Happiness?

Do you ever daydream about winning the lottery? After all, it only costs a small amount, a slight risk, with the possibility of a substantial [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

3 Happiness Exercises Pack [PDF]

Get the latest content and program updates from Life Time.

Unsubscribe

The Better Good Life: An Essay on Personal Sustainability

Imagine a cherry tree in full bloom, its roots sunk into rich earth and its branches covered with thousands of blossoms, all emitting a lovely fragrance and containing thousands of seeds capable of producing many more cherry trees. The petals begin to fall, covering the ground in a blanket of white flowers and scattering the seeds everywhere.

Some of the seeds will take root, but the vast majority will simply break down along with the spent petals, becoming part of the soil that nourishes the tree — along with thousands of other plants and animals.

Looking at this scene, do we shake our heads at the senseless waste, mess and inefficiency? Does it look like the tree is working too hard, showing signs of strain or collapse? Of course not. But why not?

Well, for one thing, because the whole process is beautiful, abundant and pleasure producing: We enjoy seeing and smelling the trees in bloom, we’re pleased by the idea of the trees multiplying (and producing delicious cherries ), and everyone for miles around seems to benefit in the process.

The entire lifecycle of the cherry tree is rewarding, and the only “waste” involved is an abundant sort of nutrient cycling that only leads to more good things.

The entire lifecycle of the cherry tree is rewarding, and the only “waste” involved is an abundant sort of nutrient cycling that only leads to more good things. Best of all, this show of productivity and generosity seems to come quite naturally to the tree. It shows no signs of discontent or resentment — in fact, it looks like it could keep this up indefinitely with nothing but good, sustainable outcomes.

The cherry-tree scenario is one model that renowned designer and sustainable-development expert William McDonough uses to illustrate how healthy, sustainable systems are supposed to work. “Every last particle contributes in some way to the health of a thriving ecosystem,” he writes in his essay (coauthored with Michael Braungart), “The Extravagant Gesture: Nature, Design and the Transformation of Human Industry” (available at).

Rampant production in this scenario poses no problem, McDonough explains, because the tree returns all of the resources it extracts (without deterioration or diminution), and it produces no dangerous stockpiles of garbage or residual toxins in the process. In fact, rampant production by the cherry tree only enriches everything around it.

In this system and most systems designed by nature, McDonough notes, “Waste that stays waste does not exist. Instead, waste nourishes; waste equals food.”

If only we humans could be lucky and wise enough to live this way — using our resources and energy to such good effect; making useful, beautiful, extravagant contributions; and producing nothing but nourishing “byproducts” in the process.

If only we humans could be lucky and wise enough to live this way — using our resources and energy to such good effect; making useful, beautiful, extravagant contributions ; and producing nothing but nourishing “byproducts” in the process. If only our version of rampant production and consumption produced so much pleasure and value and so little exhaustion, anxiety, depletion and waste.

Well, perhaps we can learn. More to the point, if we hope to create a decent future for ourselves and succeeding generations, we must. After all, a future produced by trends of the present — in which children are increasingly treated for stress, obesity, high blood pressure and heart disease, and in which our chronic health problems threaten to bankrupt our economy — is not much of a future.

We need to create something better. And for that to happen, we must begin to reconsider which parts of our lives contribute to the cherry tree’s brand of healthy vibrance and abundance, and which don’t.

The happy news is, the search for a more sustainable way of life can go hand in hand with the pursuit of a healthier, more rewarding life. And isn’t that the kind of life most of us are after?

In Search of Sustainability and Satisfaction

McDonough’s cherry-tree model represents several key principles of sustainability — including lifecycle awareness, no-waste nutrient cycling and a commitment to “it’s-all-connected” systems thinking (see “ See the Connection “). And it turns out that many of these principles can be usefully applied not just to natural resources and ecosystems, but to all systems — from frameworks for economic and industrial production to blueprints for individual and collective well-being.

For example, when we look at our lives through the lens of sustainability, we can begin to see how unwise short-term tradeoffs (fast food, skipped workouts, skimpy sleep, strictly-for-the-money jobs) produce waste (squandered energy and vitality, unfulfilled personal potential, excessive material consumption) and toxic byproducts (illness, excess weight , depression, frustration, debt).

We can also see how healthy choices and investments in our personal well-being can produce profoundly positive results that extend to our broader circles of influence and communities at large.

Conversely, we can also see how healthy choices and investments in our personal well-being can produce profoundly positive results that extend to our broader circles of influence and communities at large. When we’re feeling our best and overflowing with energy and optimism, we tend to be of greater service and support to others. We’re clearer of mind, meaning we can identify opportunities to reengineer the things that aren’t working in our lives. We can also more fully appreciate and emphasize the things that are (as opposed to feeling stuck in a rut , down in the dumps, unappreciated or entitled to something we’re not getting).

When you look at it this way, it’s not hard to see why sustainability plays such an important role in creating the conditions of a true “ good life ”: By definition, sustainability principles discourage people from consuming or destroying resources at a greater pace than they can replenish them. They also encourage people to notice when buildups and depletions begin occurring and to correct them as quickly as possible.

As a result, sustainability-oriented approaches tend to produce not just robust, resilient individuals , but resilient and regenerative societies — the kind that manage to produce long-term benefits for a great many without undermining the resources on which those benefits depend. (For a thought-provoking exploration of how and why this has been true historically, read Jared Diamond’s excellent book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed .)

The Good Life Gone Bad

So, what exactly is a “good life”? Clearly, not everyone shares the same definition, but most of us would prefer a life filled with experiences we find pleasing and worthwhile and that contribute to an overall sense of well-being.

We’d prefer a life that feels good in the moment, but that also lays the ground for a promising future — a life, like the cherry tree’s, that contributes something of value and that benefits and enriches the lives of others, or at least doesn’t cause them anxiety and harm.

Unfortunately, historically, our pursuit of the good life has focused on increasing our material wealth and upgrading our socioeconomic status in the short term (learn more at “ What Is Affluenza? “). And, in the big picture, that approach has not turned out quite the way we might have hoped.

For too many, the current version of “the good life” involves working too-long hours and driving too-long commutes. It has us worrying and running ourselves ragged.

For too many, the current version of “the good life” involves working too-long hours and driving too-long commutes. It has us worrying and running ourselves ragged, overeating to soothe ourselves, watching TV to distract ourselves, binge-shopping to sate our desire for more, and popping prescription pills to keep troubling symptoms at bay. This version of “the good life” has given us only moments a day with the people we love, and virtually no time or inclination to participate as citizens or community members.

It has also given us anxiety attacks; obesity; depression ; traffic jams; urban sprawl; crushing daycare bills; a broken healthcare system; record rates of addiction, divorce and incarceration; an imploding economy; and a planet in peril.

From an economic standpoint, we’re more productive than we’ve ever been. We’ve focused on getting more done in less time. We’ve surrounded ourselves with technologies designed to make our lives easier, more comfortable and more amusing.

Yet, instead of making us happy and healthy, all of this has left a great many of us feeling depleted, lonely, strapped, stressed and resentful. We don’t have enough time for ourselves, our loved ones, our creative aspirations or our communities. And in the wake of the bad-mortgage-meets-Wall-Street-greed crisis, much of the so-called value we’ve been busy creating has seemingly vanished before our eyes, leaving future generations of citizens to pay almost inconceivably huge bills.

The conveniences we’ve embraced to save ourselves time have reduced us to an unimaginative, sedentary existence that undermines our physical fitness and mental health and reduces our ability to give our best gifts.

Meanwhile, the quick-energy fuels we use to keep ourselves going ultimately leave us feeling sluggish, inflamed and fatigued. The conveniences we’ve embraced to save ourselves time have reduced us to an unimaginative, sedentary existence that undermines our physical fitness and mental health and reduces our ability to give our best gifts. (Not sure what your best gift is? See “ Play to Your Strengths ” for more.)

Our bodies and minds are showing the telltale symptoms of unsustainable systems at work — systems that put short-term rewards ahead of long-term value. We’re beginning to suspect that the costs we’re incurring could turn out to be unacceptably high if we ever stop to properly account for them, which some of us are beginning to do.

Accounting for What Matters

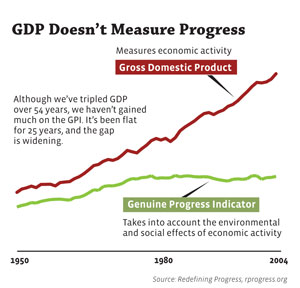

Defining the good life in terms of productivity, material rewards and personal accomplishment is a little like viewing the gross domestic product (GDP) as an accurate measurement of social and economic progress.

In fact, the GDP is nothing more than a gross tally of products and services bought and sold, with no distinctions between transactions that enhance well-being and transactions that diminish it, and no accounting for most of the “externalities” (like losses in vitality, beauty and satisfaction) that actually have the greatest impact on our personal health and welfare.

We’d balk if any business attempted to present a picture of financial health by simply tallying up all of its business activity — lumping income and expense, assets and liabilities, and debits and credits together in one impressive, apparently positive bottom-line number (which is, incidentally, much the way our GDP is calculated).

Yet, in many ways, we do the same kind of flawed calculus in our own lives — regarding as measures of success the gross sum of the to-dos we check off, the salaries we earn, the admiration we attract and the rungs we climb on the corporate ladder.

But not all of these activities actually net us the happiness and satisfaction we seek, and in the process of pursuing them, we can incur appalling costs to our health and happiness. We also make vast sacrifices in terms of our personal relationships and our contributions to the communities, societies and environments on which we depend.

This is the essence of unsustainability , the equivalent of a cherry tree sucking up nutrients and resources and growing nothing but bare branches, or worse — ugly, toxic, foul-smelling blooms. So what are our options?

Asking the Right Questions

In the past several years, many alternative, GDP-like indexes have emerged and attempted to more accurately account for how well (or, more often, how poorly) our economic growth is translating to quality-of-life improvements.

Measurement tools like the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), developed by Redefining Progress, a nonpartisan public-policy and economic think tank, factor in well-being and quality-of-life concerns by considering both positive and negative impacts of various products and services. They also measure more impacts overall (including impacts on elements of “being” and “doing” vs. just “having”). And they evaluate whether various financial expenditures represent a net gain or net loss — not just in economic terms, but also in human, social and ecological ones (see “Sustainable Happiness,” below).

Perhaps it’s time to consider our personal health and well-being in the same sort of broader context — distinguishing productive activities from destructive ones, and figuring the true costs and unintended consequences of our choices into the assessment of how well our lives are working.

To that end, we might begin asking questions like these:

- Where, in our rush to accomplish or enjoy “more” in the short run, are we inadvertently creating the equivalent of garbage dumps and toxic spills (stress overloads, health crises, battered relationships, debt) that will need to be cleaned up later at great (think Superfund) effort and expense?

- Where, in our impatience to garner maximum gains in personal productivity, wealth or achievement in minimum time, are we setting the stage for bailout scenarios down the road? (Consider the sacrifices endured by our families, friends and colleagues when we fall victim to a bad mood, much less a serious illness or disabling health condition.)

- Where, in an attempt to avoid uncertainty, experimentation or change , are we burning through our limited and unrenewable resource of time (staying at jobs that leave us depleted, for example), rather than striving to harness our bottomless stores of purpose-driven enthusiasm (by, say, pursuing careers or civic duties of real meaning)?

- Where are we making short-sighted choices or non-choices (about our health, for example) that sacrifice the resources we need (energy, vitality, clear focus) to make progress and contributions in other areas of our lives?

In addition to these assessments, we can also begin imagining what a better alternative would look like:

- What might be possible if we embraced a different version of the good life — the kind of good life in which the vast majority of our choices both feel good and do good?

- What if we took a systems view of our life , acknowledging how various inputs and outputs play out (for better or worse) over time? What if we fully considered how those around us are affected by our choices now and in the long term?

- What if we embraced more choices that honor our true nature, that gave us more opportunities to use our talents and enthusiasms in the service of a higher purpose?

One has to wonder how many of our health and fitness challenges would evaporate under such conditions — how many compensatory behaviors (overeating, hiding out, numbing out) would simply no longer have a draw.

How many health-sustaining behaviors would become easy and natural choices if each of us were driven by a strong and joyful purpose , and were no longer saddled with the stress and dissatisfaction inherent in the lives we live now?

Think about the cherry-tree effect implicit in such a scenario: each of us getting our needs met, fulfilling our best potential, living at full vitality, and contributing to healthy, vital, sustainable communities in the process.

If it sounds a bit idealistic, that’s probably because it describes an ideal distant enough from our current reality to provoke a certain amount of hopelessness. But that doesn’t mean it’s entirely unrealistic. In fact, it’s a vision that many people are increasingly convinced is the only kind worth pursuing.

Turning the Corner

Maybe it has something to do with how many of our social, economic and ecological systems are showing signs of extreme strain. Maybe it’s how many of us are sick and tired of being sick and tired — or of living in a culture where everyone else seems sick and tired. Maybe it’s the growing realization that no matter how busy and efficient we are, if our efforts don’t feed us in a deep way, then all that output may be more than a little misguided. Whatever the reason, a lot of us are asking: If our rampant productivity doesn’t make us happy, doesn’t allow for calm and creativity, doesn’t give us an opportunity to participate in a meaningful way — then, really, what’s the point?

These days, it seems that more of us are taking a keen interest in seeking out better ways, and seeing the value of extending the lessons of sustainability beyond the natural world and into our own perspectives on what the good life is all about.

In her book MegaTrends 2010: The Rise of Conscious Capitalism , futurist Patricia Aburdene describes a hopeful collection of social and economic trends shaped by a large and influential subset of the American consuming public. What these 70 million individuals have in common, she explains, are some very specific values-driven behaviors — most of which revolve around seeking a better, deeper, more meaningful and sustainable quality of life (discover the four pillars or meaning at “ How to Build a Meaningful Life “).

[“Conscious Consumers” balance] short-term desires and conveniences with long-term well-being — not just their own, but that of their local and larger communities, and of the planet as a whole.

These “Conscious Consumers,” as Aburdene characterizes them, are more carefully weighing material and economic payoffs against moral and spiritual ones. They are balancing short-term desires and conveniences with long-term well-being — not just their own, but that of their local and larger communities, and of the planet as a whole. They are acting, says Aburdene, out of a sort of “enlightened self-interest,” one that is deeply rooted in concerns about sustainability in all its forms.

“Enlightened self-interest is not altruism,” she explains. “It’s self-interest with a wider view. It asks: If I act in my own self-interest and keep doing so, what are the ramifications of my choices? Which acts — that may look fine right now — will come around and bite me and others one year from now? Ten years? Twenty-five years?”

In other words, Conscious Consumers are not merely consumers, but engaged and concerned individuals who think in terms of lifecycles, who perceive the subtleties and complexities of interconnected systems .

As John Muir famously said: “When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.” Just as the cherry tree is tethered in a complex ecosystem of relationships, so are we.

Facing Reality

When we live in a way that diminishes us or weighs us down — whether as the result of poor physical health and fitness, excess stress and anxiety, or any compromise of our best potential — we inevitably affect countless other people and systems whose well-being relies on our own.

For example, if we don’t have the time and energy to make food for ourselves and our families, we end up eating poorly, which further diminishes our energy, and may also result in our kids having behavior or attention problems at school, undermining the quality of their experience there, and potentially creating problems for others.

As satisfaction and well-being go down, need and consumption go up.

If we skimp on sleep and relaxation in order to “get more done,” we court illness and depression, risking both our own and others’ productivity and happiness in the process and diminishing the creativity with which we approach challenges.

At the individual level, unsustainable choices create strain and misery. At the collective level, they do the same thing, with exponential effect. Because, when not enough of us are living like thriving cherry trees, cycles of scarcity (rather than abundance) ensue. Life gets harder for everyone. As satisfaction and well-being go down, need and consumption go up. Our sense of “enough” becomes distorted.

Taking Full Account

The basic question of sustainability is this: Can you keep doing what you’re doing indefinitely and without ill effect to yourself and the systems on which you depend — or are you (despite short-term rewards you may be enjoying now, or the “someday” relief you’re hoping for) on a likely trajectory to eventual suffering and destruction?

When it comes to the ecology of the planet, this question has become very pointed in recent years. But posed in the context of our personal lives, the question is equally instructive: Are we living like the cherry tree — part of a sustainable and regenerative cycle — or are we sucking up resources, yet still obsessed with what we don’t have? Are we continually generating new energy, vitality, generosity and personal potential , or wasting it?

We can work just so hard and consume just so much before we begin to experience both diminishing personal returns and increasing degenerative costs.

The human reality, in most cases, isn’t quite as pretty as the cherry tree in full bloom. We can work just so hard and consume just so much before we begin to experience both diminishing personal returns and increasing degenerative costs. And when enough of us are in a chronically diminished state of well-being, the effect is a sort of social and moral pollution — the human equivalent of the greenhouse gasses that threaten our entire ecosystem.

Accounting for these soft costs, or even recognizing them as relevant externalities, is not something we’ve been trained to do well. But all that is changing — in part, because many of us are beginning to realize that much of what we’ve been sold in the name of “progress” is now looking like anything but. And, in part, because we’re starting to believe that not only might there be a better way, but that the principles for creating it are staring us right in the face.

By making personal choices that respect the principles of sustainability, we can interrupt the toxic cycles of overconsumption and overexertion. Ultimately, when confronted with the possibility of a better quality of life and more satisfying expression of our potential, the primary question becomes not just can we continue living the way we have been, but perhaps just as important, why would we even want to ?

If the approach we’ve been taking appears likely to make us miserable (and perhaps extinct), then it makes sense to consider our options. How do we want to live for the foreseeable and sustainable future, and what are the building blocks for that future? What would it be like to live in a community where most people were overflowing with vitality and looking for ways to be of service to others?

While no one expert or index or council claims to have all the answers to that question, when it comes to discerning the fundamentals of the good life, nature conveniently provides most of the models we need. It suggests a framework by which we can better understand and apply the principles of sustainability to our own lives. Now it’s up to us to apply them.

Make It Sustainable

Here are some right-now changes you can make to enhance and sustain your personal well-being:

1. Rethink Your Eating.

Look beyond meal-to-meal concerns with weight. Aim to eat consciously and selectively in keeping with the nourishment you want to take in, the energy and personal gifts you want to contribute, and the influence you want to have on the world around you.

To that end, you might start eating less meat, or fewer packaged foods, or you might start eating regularly so that you have enough energy to exercise (and so that your low blood sugar doesn’t negatively affect your mood and everyone around you).

You also might start packing your lunch, suggests money expert Vicki Robin: Not only will you have more control over what and how you eat, but the money you’ll save over the course of a career can amount to a year’s worth of work. “Bringing your lunch saves you a year of your life,” she says.

2. Set a Regular Bedtime

Having a target bedtime can help you get the sleep you need to be positive and productive, and to avoid becoming depleted and depressed. Research confirms that adequate sleep is essential to clear thinking, balanced mood, healthy metabolism, strong immunity, optimal vitality and strong professional performance.

Research also shows that going to bed earlier provides a higher quality of rest than sleeping in, so get your hours at the start of the night. By taking care of yourself in this simple way, you lay the groundwork for all kinds of regenerative (vs. depleting) cycles.

3. Own Your Outcomes

If there are parts of your life you don’t like — parts that feel toxic, frustrating or wasteful to you — be willing to trace the outcomes back to their origins, including your choices around self-care , seeking help, balancing priorities and sticking to your core values.

Also examine the full range of outputs and impacts: What waste or damage is occurring as a result of this area of unresolved challenge? Who else and what else in your life might be paying too-high a price for the scenario in question? If you’re unsure about whether or not a choice or an activity you’re involved in is sustainable, ask yourself the following questions:

- Given the option, would I do or choose this again? Would I do it indefinitely?

- How long can I keep this up, and at what cost — not just to me, but to the other people and systems I care about?

- What have I sacrificed to get here; what will it take for me to continue? Are the rewards worth it, even if the other areas of my life suffer?

Sustainable Happiness

Not all growth and productivity represent progress, particularly if you consider happiness and well-being as part of the equation. The growing gap between our gross domestic product and Genuine Progress Indicator (as represented below) suggests we could be investing our resources with far happier results.

Data source: Redefining Progress, rprogress.org . Chart graphic courtesy of Yes! magazine.

Learn more about the most reliable, sustainable sources of happiness and well-being in the Winter 2009 issue of Yes! magazine, available at www.yesmagazine.org .

Learning From Nature

What can we learn from ecological sustainability about the best ways to balance and sustain our own lives? Here are a few key lessons:

- Everything is in relationship with everything else. So overdrawing or overproducing in one area tends to negatively affect other areas. An excessive focus on work can undermine your relationship with your partner or kids. Diminished physical vitality or low mood can affect the quality of your work and service to others.

- What comes around goes around. Trying to “cheat” or “skimp” or “get away with something” in the short term generally doesn’t work because the true costs of cheating eventually become painfully obvious. And very often the “cleanup” costs more and takes longer than it would have to simply do the right thing in the first place.

- Waste not, want not. Unpleasant accumulations or unsustainable drains represent opportunities for improvement and reinvention. Nature’s models of nutrient cycling show us that what looks like waste can become food for a process we simply haven’t engaged yet: Anxiety may be nervous energy that needs to be burned off, or a nudge to do relaxation and self-inquiry exercises that will churn up new insights and ideas. Excess fat may be fuel for enjoyable activities we’ve resisted doing or haven’t yet discovered — or a clue that we’re hungry for something other than food. The clutter in our homes may represent resources that we haven’t gotten around to sharing. Look for ways to put waste and excess to work, and you may discover all kinds of “nutrients” just looking for attention. (See “ The Emotional Toll of Clutter “.)

The Sustainable Self

Connie Grauds, RPh, is a pharmacist who combines her Western medical training with shamanic teachings, and in her view, we get caught in wearying patterns primarily because of fear . “Energy-depleting thoughts and feelings underlie energy-depleting habits,” Grauds writes in her book The Energy Prescription , cowritten with Doug Childers. She says that we often burn ourselves out because we’re unconsciously afraid of what will happen if we don’t.

Grauds uses the shamanic term “susto” to describe our anxious response to external situations we can’t control — the traffic jam, the work deadline, the pressure to buy stuff we don’t really need. “Susto” triggers the body’s fight-or-flight response, which encourages short-term, unconscious reactions to stress. When we shift to a more internal focus, tuning in to our body’s physical and emotional signals more reflectively, we act from what Grauds calls our “sustainable self.” She says the sustainable self can be accessed anytime with a simple four-step process:

- Take a deep breath ;

- Feel your body;

- Notice your thoughts, and then;

- Recognize that you are connected to a larger network of energy .

“A sustainable self recognizes and embraces its interdependent relationship to life,” she says, explaining that when we get our energy from controlling external circumstances we’re bound to collapse eventually, but when we’re connected to our internal reserves, we can be much more effective. “By consistently doing things that replenish us and not doing things that needlessly deplete us,” Grauds writes, “we access and conduct the energy we need to make and sustain positive changes and function at peak levels.”

Thoughts to share?

This Post Has 0 Comments

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

ADVERTISEMENT

More Like This

How to Develop a ‘Stretch’ Mindset

Working with what you have can be the key to more sustainable success. Adopting a “stretch” mindset can help.

The Power of Intention: Learning to Co-Create Your World Your Way

Thought-provoking takeaways from Wayne Dyer’s classic guide to conscious living.

6 Keys to a Happy and Healthy Life

A functional-medicine pioneer explains how to make small choices that build lasting well-being.

What Does It Mean to Live the Good Life?

Golf & Spa

- Philosophical Theories & Ideas

- Major Philosophers

- Ph.D., Philosophy, The University of Texas at Austin

- M.A., Philosophy, McGill University

- B.A., Philosophy, University of Sheffield

What is “the good life”? This is one of the oldest philosophical questions . It has been posed in different ways—How should one live? What does it mean to “live well”?—but these are really just the same question. After all, everyone wants to live well, and no one wants “the bad life.”

But the question isn’t as simple as it sounds. Philosophers specialize in unpacking hidden complexities, and the concept of the good life is one of those that needs quite a bit of unpacking.

The Moral Life

One basic way we use the word “good” is to express moral approval. So when we say someone is living well or that they have lived a good life, we may simply mean that they are a good person, someone who is courageous, honest, trustworthy, kind, selfless, generous, helpful, loyal, principled, and so on.

They possess and practice many of the most important virtues. And they don’t spend all their time merely pursuing their own pleasure; they devote a certain amount of time to activities that benefit others, perhaps through their engagement with family and friends, or through their work, or through various voluntary activities.

This moral conception of the good life has had plenty of champions. Socrates and Plato both gave absolute priority to being a virtuous person over all other supposedly good things such as pleasure, wealth, or power.

In Plato’s dialogue Gorgias , Socrates takes this position to an extreme. He argues that it is much better to suffer wrong than to do it; that a good man who has his eyes gouged out and is tortured to death is more fortunate than a corrupt person who has used wealth and power dishonorably.

In his masterpiece, the Republic , Plato develops this argument in greater detail. The morally good person, he claims, enjoys a sort of inner harmony, whereas the wicked person, no matter how rich and powerful he may be or how many pleasure he enjoys, is disharmonious, fundamentally at odds with himself and the world.

It is worth noting, though, that in both the Gorgias and the Republic , Plato bolsters his argument with a speculative account of an afterlife in which virtuous people are rewarded and wicked people are punished.

Many religions also conceive of the good life in moral terms as a life lived according to God’s laws. A person who lives this way—obeying the commandments and performing the proper rituals—is pious . And in most religions, such piety will be rewarded. Obviously, many people do not receive their reward in this life.

But devout believers are confident that their piety will not be in vain. Christian martyrs went singing to their deaths confident that they would soon be in heaven. Hindus expect that the law of karma will ensure that their good deeds and intentions will be rewarded, while evil actions and desires will be punished, either in this life or in future lives.

The Life of Pleasure

The ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus was one of the first to declare, bluntly, that what makes life worth living is that we can experience pleasure. Pleasure is enjoyable, it’s fun, it’s...well...pleasant! The view that pleasure is the good, or, to put I another way, that pleasure is what makes life worth living, is known as hedonism .

The word “hedonist,” when applied to a person, has slightly negative connotations. It suggests that they are devoted to what some have called the “lower” pleasures such as sex, food, drink, and sensual indulgence in general.

Epicurus was thought by some of his contemporaries to be advocating and practicing this sort of lifestyle, and even today an “epicure” is someone who is especially appreciative of food and drink. But this is a misrepresentation of Epicureanism. Epicurus certainly praised all kinds of pleasures. But he didn’t advocate that we lose ourselves in sensual debauchery for various reasons:

- Doing so will probably reduce our pleasures in the long run since over-indulgence tends to cause health problems and limit the range of pleasure we enjoy.

- The so-called “higher” pleasures such as friendship and study are at least as important as “pleasures of the flesh."

- The good life has to be virtuous. Although Epicurus disagreed with Plato about the value of pleasure, he fully agreed with him on this point.

Today, this hedonistic conception of the good life is arguably dominant in Western culture. Even in everyday speech, if we say someone is “living the good life,” we probably mean that they enjoying lots of recreational pleasures: good food, good wine, skiing, scuba diving, lounging by the pool in the sun with a cocktail and a beautiful partner.

What is key to this hedonistic conception of the good life is that it emphasizes subjective experiences . On this view, to describe a person as “happy” means that they “feel good,” and a happy life is one that contains many “feel good” experiences.

The Fulfilled Life

If Socrates emphasizes virtue and Epicurus emphasizes pleasure, another great Greek thinker, Aristotle , views the good life in a more comprehensive way. According to Aristotle, we all want to be happy.

We value many things because they are a means to other things. For instance, we value money because it enables us to buy things we want; we value leisure because it gives us time to pursue our interests. But happiness is something we value not as a means to some other end but for its own sake. It has intrinsic value rather than instrumental value.

So for Aristotle , the good life is a happy life. But what does that mean? Today, many people automatically think of happiness in subjectivist terms: To them, a person is happy if they are enjoying a positive state of mind, and their life is happy if this is true for them most of the time.

There is a problem with this way of thinking about happiness in this way, though. Imagine a powerful sadist who spends much of his time gratifying cruel desires. Or imagine a pot-smoking, beer-guzzling couch potato who does nothing but sit around all day watching old TV shows and playing video games. These people may have plenty of pleasurable subjective experiences. But should we really describe them as “living well”?

Aristotle would certainly say no. He agrees with Socrates that to live the good life one must be a morally good person. And he agrees with Epicurus that a happy life will involve many and varied pleasurable experiences. We can’t really say someone is living the good life if they are often miserable or constantly suffering.

But Aristotle’s idea of what it means to live well is objectivist rather than subjectivist. It isn’t just a matter of how a person feels inside, although that does matter. It’s also important that certain objective conditions be satisfied.

For instance:

- Virtue: They must be morally virtuous.

- Health: They should enjoy good health and reasonably long life.

- Prosperity: They should be comfortably off (for Aristotle this meant affluent enough so that they don’t need to work for a living doing something that they would not freely choose to do.)

- Friendship: They must have good friends. According to Aristotle human beings are innately social; so the good life can’t be that of a hermit , a recluse, or a misanthrope.

- Respect: They should enjoy the respect of others. Aristotle doesn’t think that fame or glory is necessary; in fact, a craving for fame can lead people astray, just as the desire for excessive wealth can. But ideally, a person’s qualities and achievements will be recognized by others.

- Luck: They need good luck. This is an example of Aristotle’s common sense. Any life can be rendered unhappy by tragic loss or misfortune.

- Engagement: They must exercise their uniquely human abilities and capacities. This is why the couch potato is not living well, even if they report that they are content. Aristotle argues that what separates human beings from the other animals is the human reason. So the good life is one in which a person cultivates and exercises their rational faculties by, for instance, engaging in scientific inquiry, philosophical discussion, artistic creation, or legislation. Were he alive today he might well include some forms of technological innovation.

If at the end of your life you can check all these boxes then you could reasonably claim to have lived well, to have achieved the good life. Of course, the great majority of people today do not belong to the leisure class as Aristotle did. They have to work for a living.

But it’s still true that we think the ideal circumstance is to be doing for a living what you would choose to do anyway. So people who are able to pursue their calling are generally regarded as extremely fortunate.

The Meaningful Life