An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

A critical thinking disposition scale for nurses: short form

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Nursing, Chung Hwa University of Medical Technology, Tainan, Taiwan.

- PMID: 21040020

- DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03343.x

Aims and objectives: The aim of this study was to test the Chinese version of the Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CTDI-CV) among nurses in Taiwan.

Background: Critical thinking is the use of purposeful self-regulatory judgments to identify patient's problems and provide patient care. Critical thinking influences nurses' decision making. To date, no inventory to understand nurse's critical thinking disposition has been developed.

Design: This was a survey design with a stratified random sampling to test the reliability and validity of the CTDI-CV.

Methods: The participants comprised 864 registered nurses who were chosen by stratified random sampling from seven hospitals in Taiwan. Data were collected through self-administered structured questionnaires.

Results: A new scale, short form (SF) CTDI-CV, contains 18 items with three subscales: 'systematic analysis', 'thinking within the box' and 'thinking out of the box', was generated from the analysis with 44% explained variance. Cronbach's alpha coefficients and intra-class correlation coefficients for overall and subscale were above 0.8. Goodness-of-fit test for the final model of SF-CTDI-CV revealed an acceptable result in the overall fit (χ(2)/df = 4.04, p < 0.05, GFI = 0.93, AGFI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.076, RMSEA = 0.059).

Conclusion: On the basis of these results, the SF-CTDI-CV is a reliable instrument for assessing critical thinking disposition for nurses.

Relevance to clinical practice: A short and valid critical thinking instrument for nurses will facilitate critical thinking research in the clinical practice arena. When designing continuing education activities, clinical educators will be able to efficiently and effectively evaluate the quality of critical thinking among practicing nurses.

© 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Critical thinking competence and disposition of clinical nurses in a medical center. Feng RC, Chen MJ, Chen MC, Pai YC. Feng RC, et al. J Nurs Res. 2010 Jun;18(2):77-87. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e3181dda6f6. J Nurs Res. 2010. PMID: 20592653

- Measuring professional competency of public health nurses: development of a scale and psychometric evaluation. Lin CJ, Hsu CH, Li TC, Mathers N, Huang YC. Lin CJ, et al. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Nov;19(21-22):3161-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03149.x. J Clin Nurs. 2010. PMID: 20704628

- Development of competency inventory for registered nurses in the People's Republic of China: scale development. Liu M, Kunaiktikul W, Senaratana W, Tonmukayakul O, Eriksen L. Liu M, et al. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007 Jul;44(5):805-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.01.010. Epub 2006 Mar 7. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007. PMID: 16519890

- Evaluating the performance of the APN. Nugent KE, Lambert VA. Nugent KE, et al. Nurs Manage. 1997 Feb;28(2):29-32. Nurs Manage. 1997. PMID: 9287741 Review.

- Qualitative research in clinical nurse specialist practice. Sorrell JM. Sorrell JM. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013 Jul-Aug;27(4):175-8. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3182990847. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013. PMID: 23748988 Review. No abstract available.

- Critical thinking predicts reductions in Spanish physicians' stress levels and promotes fake news detection. Escolà-Gascón Á, Dagnall N, Gallifa J. Escolà-Gascón Á, et al. Think Skills Creat. 2021 Dec;42:100934. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100934. Epub 2021 Aug 27. Think Skills Creat. 2021. PMID: 35154504 Free PMC article.

- Development and evaluation of clinical reasoning using 'think aloud' approach in pharmacy undergraduates - A mixed-methods study. Altalhi F, Altalhi A, Magliah Z, Abushal Z, Althaqafi A, Falemban A, Cheema E, Dehele I, Ali M. Altalhi F, et al. Saudi Pharm J. 2021 Nov;29(11):1250-1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.10.003. Epub 2021 Oct 19. Saudi Pharm J. 2021. PMID: 34819786 Free PMC article.

- Influence of critical thinking disposition on the learning efficiency of problem-based learning in undergraduate medical students. Pu D, Ni J, Song D, Zhang W, Wang Y, Wu L, Wang X, Wang Y. Pu D, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2019 Jan 3;19(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1418-5. BMC Med Educ. 2019. PMID: 30606170 Free PMC article.

- Critical thinking dispositions of nursing students in Asian and non-Asian countries: a literature review. Salsali M, Tajvidi M, Ghiyasvandian S. Salsali M, et al. Glob J Health Sci. 2013 Sep 26;5(6):172-8. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n6p172. Glob J Health Sci. 2013. PMID: 24171885 Free PMC article. Review.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

How Do Critical Thinking Ability and Critical Thinking Disposition Relate to the Mental Health of University Students?

Associated data.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems associate with deficiencies in critical thinking. However, it currently remains unclear whether both critical thinking skill and critical thinking disposition relate to individual differences in mental health. This study explored whether and how the critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition of university students associate with individual differences in mental health in considering impulsivity that has been revealed to be closely related to both critical thinking and mental health. Regression and structural equation modeling analyses based on a Chinese university student sample ( N = 314, 198 females, M age = 18.65) revealed that critical thinking skill and disposition explained a unique variance of mental health after controlling for impulsivity. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity (acting on the spur of the moment) and non-planning impulsivity (making decisions without careful forethought). These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking associate with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions and enhancing their control over impulsive behavior.

Introduction

Although there is no consistent definition of critical thinking (CT), it is usually described as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanations of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations that judgment is based upon” (Facione, 1990 , p. 2). This suggests that CT is a combination of skills and dispositions. The skill aspect mainly refers to higher-order cognitive skills such as inference, analysis, and evaluation, while the disposition aspect represents one's consistent motivation and willingness to use CT skills (Dwyer, 2017 ). An increasing number of studies have indicated that CT plays crucial roles in the activities of university students such as their academic performance (e.g., Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), professional work (e.g., Barry et al., 2020 ), and even the ability to cope with life events (e.g., Butler et al., 2017 ). An area that has received less attention is how critical thinking relates to impulsivity and mental health. This study aimed to clarify the relationship between CT (which included both CT skill and CT disposition), impulsivity, and mental health among university students.

Relationship Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

Associating critical thinking with mental health is not without reason, since theories of psychotherapy have long stressed a linkage between mental problems and dysfunctional thinking (Gilbert, 2003 ; Gambrill, 2005 ; Cuijpers, 2019 ). Proponents of cognitive behavioral therapy suggest that the interpretation by people of a situation affects their emotional, behavioral, and physiological reactions. Those with mental problems are inclined to bias or heuristic thinking and are more likely to misinterpret neutral or even positive situations (Hollon and Beck, 2013 ). Therefore, a main goal of cognitive behavioral therapy is to overcome biased thinking and change maladaptive beliefs via cognitive modification skills such as objective understanding of one's cognitive distortions, analyzing evidence for and against one's automatic thinking, or testing the effect of an alternative way of thinking. Achieving these therapeutic goals requires the involvement of critical thinking, such as the willingness and ability to critically analyze one's thoughts and evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs. In addition to theoretical underpinnings, characteristics of university students also suggest a relationship between CT and mental health. University students are a risky population in terms of mental health. They face many normative transitions (e.g., social and romantic relationships, important exams, financial pressures), which are stressful (Duffy et al., 2019 ). In particular, the risk increases when students experience academic failure (Lee et al., 2008 ; Mamun et al., 2021 ). Hong et al. ( 2010 ) found that the stress in Chinese college students was primarily related to academic, personal, and negative life events. However, university students are also a population with many resources to work on. Critical thinking can be considered one of the important resources that students are able to use (Stupple et al., 2017 ). Both CT skills and CT disposition are valuable qualities for college students to possess (Facione, 1990 ). There is evidence showing that students with a higher level of CT are more successful in terms of academic performance (Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), and that they are better at coping with stressful events (Butler et al., 2017 ). This suggests that that students with higher CT are less likely to suffer from mental problems.

Empirical research has reported an association between CT and mental health among college students (Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ; Kargar et al., 2013 ; Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ; Chen and Hwang, 2020 ; Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ). Most of these studies focused on the relationship between CT disposition and mental health. For example, Suliman and Halabi ( 2007 ) reported that the CT disposition of nursing students was positively correlated with their self-esteem, but was negatively correlated with their state anxiety. There is also a research study demonstrating that CT disposition influenced the intensity of worry in college students either by increasing their responsibility to continue thinking or by enhancing the detached awareness of negative thoughts (Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ). Regarding the relationship between CT ability and mental health, although there has been no direct evidence, there were educational programs examining the effect of teaching CT skills on the mental health of adolescents (Kargar et al., 2013 ). The results showed that teaching CT skills decreased somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression, and insomnia in adolescents. Another recent CT skill intervention also found a significant reduction in mental stress among university students, suggesting an association between CT skills and mental health (Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ).

The above research provides preliminary evidence in favor of the relationship between CT and mental health, in line with theories of CT and psychotherapy. However, previous studies have focused solely on the disposition aspect of CT, and its link with mental health. The ability aspect of CT has been largely overlooked in examining its relationship with mental health. Moreover, although the link between CT and mental health has been reported, it remains unknown how CT (including skill and disposition) is associated with mental health.

Impulsivity as a Potential Mediator Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

One important factor suggested by previous research in accounting for the relationship between CT and mental health is impulsivity. Impulsivity is recognized as a pattern of action without regard to consequences. Patton et al. ( 1995 ) proposed that impulsivity is a multi-faceted construct that consists of three behavioral factors, namely, non-planning impulsiveness, referring to making a decision without careful forethought; motor impulsiveness, referring to acting on the spur of the moment; and attentional impulsiveness, referring to one's inability to focus on the task at hand. Impulsivity is prominent in clinical problems associated with psychiatric disorders (Fortgang et al., 2016 ). A number of mental problems are associated with increased impulsivity that is likely to aggravate clinical illnesses (Leclair et al., 2020 ). Moreover, a lack of CT is correlated with poor impulse control (Franco et al., 2017 ). Applications of CT may reduce impulsive behaviors caused by heuristic and biased thinking when one makes a decision (West et al., 2008 ). For example, Gregory ( 1991 ) suggested that CT skills enhance the ability of children to anticipate the health or safety consequences of a decision. Given this, those with high levels of CT are expected to take a rigorous attitude about the consequences of actions and are less likely to engage in impulsive behaviors, which may place them at a low risk of suffering mental problems. To the knowledge of the authors, no study has empirically tested whether impulsivity accounts for the relationship between CT and mental health.

This study examined whether CT skill and disposition are related to the mental health of university students; and if yes, how the relationship works. First, we examined the simultaneous effects of CT ability and CT disposition on mental health. Second, we further tested whether impulsivity mediated the effects of CT on mental health. To achieve the goals, we collected data on CT ability, CT disposition, mental health, and impulsivity from a sample of university students. The results are expected to shed light on the mechanism of the association between CT and mental health.

Participants and Procedure

A total of 314 university students (116 men) with an average age of 18.65 years ( SD = 0.67) participated in this study. They were recruited by advertisements from a local university in central China and majoring in statistics and mathematical finance. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Each participant signed a written informed consent describing the study purpose, procedure, and right of free. All the measures were administered in a computer room. The participants were tested in groups of 20–30 by two research assistants. The researchers and research assistants had no formal connections with the participants. The testing included two sections with an interval of 10 min, so that the participants had an opportunity to take a break. In the first section, the participants completed the syllogistic reasoning problems with belief bias (SRPBB), the Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCSTS-CV), and the Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI), respectively. In the second session, they completed the Barrett Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11), Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), and University Personality Inventory (UPI) in the given order.

Measures of Critical Thinking Ability

The Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test was employed to measure CT skills (Lin, 2018 ). The CCTST is currently the most cited tool for measuring CT skills and includes analysis, assessment, deduction, inductive reasoning, and inference reasoning. The Chinese version included 34 multiple choice items. The dependent variable was the number of correctly answered items. The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST is 0.56 (Jacobs, 1995 ). The test–retest reliability of CCTST-CV is 0.63 ( p < 0.01) (Luo and Yang, 2002 ), and correlations between scores of the subscales and the total score are larger than 0.5 (Lin, 2018 ), supporting the construct validity of the scale. In this study among the university students, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST-CV was 0.5.

The second critical thinking test employed in this study was adapted from the belief bias paradigm (Li et al., 2021 ). This task paradigm measures the ability to evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs (West et al., 2008 ), which is a strongly emphasized skill in CT literature. The current test included 20 syllogistic reasoning problems in which the logical conclusion was inconsistent with one's prior knowledge (e.g., “Premise 1: All fruits are sweet. Premise 2: Bananas are not sweet. Conclusion: Bananas are not fruits.” valid conclusion). In addition, four non-conflict items were included as the neutral condition in order to avoid a habitual response from the participants. They were instructed to suppose that all the premises are true and to decide whether the conclusion logically follows from the given premises. The measure showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.83) in a Chinese sample (Li et al., 2021 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the SRPBB was 0.94.

Measures of Critical Thinking Disposition

The Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory was employed to measure CT disposition (Peng et al., 2004 ). This scale has been developed in line with the conceptual framework of the California critical thinking disposition inventory. We measured five CT dispositions: truth-seeking (one's objectivity with findings even if this requires changing one's preconceived opinions, e.g., a person inclined toward being truth-seeking might disagree with “I believe what I want to believe.”), inquisitiveness (one's intellectual curiosity. e.g., “No matter what the topic, I am eager to know more about it”), analyticity (the tendency to use reasoning and evidence to solve problems, e.g., “It bothers me when people rely on weak arguments to defend good ideas”), systematically (the disposition of being organized and orderly in inquiry, e.g., “I always focus on the question before I attempt to answer it”), and CT self-confidence (the trust one places in one's own reasoning processes, e.g., “I appreciate my ability to think precisely”). Each disposition aspect contained 10 items, which the participants rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale. This measure has shown high internal consistency (overall Cronbach's α = 0.9) (Peng et al., 2004 ). In this study, the CCTDI scale was assessed at Cronbach's α = 0.89, indicating good reliability.

Measure of Impulsivity

The well-known Barrett Impulsivity Scale (Patton et al., 1995 ) was employed to assess three facets of impulsivity: non-planning impulsivity (e.g., “I plan tasks carefully”); motor impulsivity (e.g., “I act on the spur of the moment”); attentional impulsivity (e.g., “I concentrate easily”). The scale includes 30 statements, and each statement is rated on a 5-point scale. The subscales of non-planning impulsivity and attentional impulsivity were reversely scored. The BIS-11 has good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.81, Velotti et al., 2016 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the BIS-11 was 0.83.

Measures of Mental Health

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 was used to assess mental health problems such as depression (e.g., “I feel that life is meaningless”), anxiety (e.g., “I find myself getting agitated”), and stress (e.g., “I find it difficult to relax”). Each dimension included seven items, which the participants were asked to rate on a 4-point scale. The Chinese version of the DASS-21 has displayed a satisfactory factor structure and internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92, Wang et al., 2016 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the DASS-21 was 0.94.

The University Personality Inventory that has been commonly used to screen for mental problems of college students (Yoshida et al., 1998 ) was also used for measuring mental health. The 56 symptom-items assessed whether an individual has experienced the described symptom during the past year (e.g., “a lack of interest in anything”). The UPI showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92) in a Chinese sample (Zhang et al., 2015 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the UPI was 0.85.

Statistical Analyses

We first performed analyses to detect outliers. Any observation exceeding three standard deviations from the means was replaced with a value that was three standard deviations. This procedure affected no more than 5‰ of observations. Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which facets of critical thinking were related to mental health. In addition, structural equation modeling with Amos 22.0 was performed to assess the latent relationship between CT, impulsivity, and mental health.

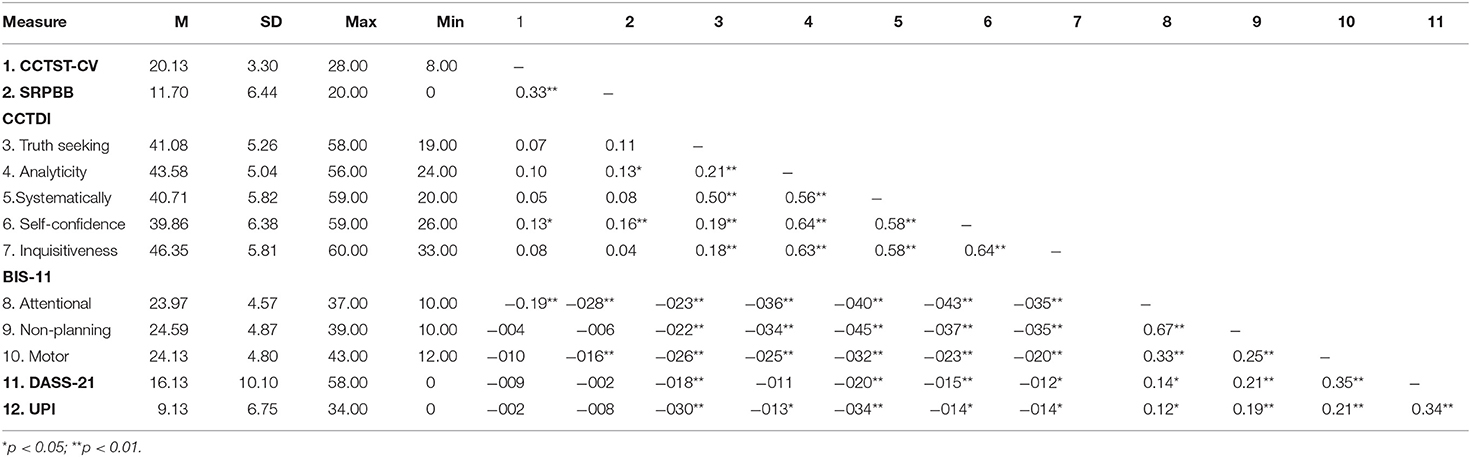

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of all the variables. CT disposition such as truth-seeking, systematicity, self-confidence, and inquisitiveness was significantly correlated with DASS-21 and UPI, but neither CCTST-CV nor SRPBB was related to DASS-21 and UPI. Subscales of BIS-11 were positively correlated with DASS-21 and UPI, but were negatively associated with CT dispositions.

Descriptive results and correlations between all measured variables ( N = 314).

| 20.13 | 3.30 | 28.00 | 8.00 | − | |||||||||||

| 11.70 | 6.44 | 20.00 | 0 | 0.33 | − | ||||||||||

| 3. Truth seeking | 41.08 | 5.26 | 58.00 | 19.00 | 0.07 | 0.11 | − | ||||||||

| 4. Analyticity | 43.58 | 5.04 | 56.00 | 24.00 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.21 | − | |||||||

| 5.Systematically | 40.71 | 5.82 | 59.00 | 20.00 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.50 | 0.56 | − | ||||||

| 6. Self-confidence | 39.86 | 6.38 | 59.00 | 26.00 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.64 | 0.58 | − | |||||

| 7. Inquisitiveness | 46.35 | 5.81 | 60.00 | 33.00 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.64 | − | ||||

| 8. Attentional | 23.97 | 4.57 | 37.00 | 10.00 | −0.19 | −028 | −023 | −036 | −040 | −043 | −035 | − | |||

| 9. Non-planning | 24.59 | 4.87 | 39.00 | 10.00 | −004 | −006 | −022 | −034 | −045 | −037 | −035 | 0.67 | − | ||

| 10. Motor | 24.13 | 4.80 | 43.00 | 12.00 | −010 | −016 | −026 | −025 | −032 | −023 | −020 | 0.33 | 0.25 | − | |

| 16.13 | 10.10 | 58.00 | 0 | −009 | −002 | −018 | −011 | −020 | −015 | −012 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.35 | − | |

| 9.13 | 6.75 | 34.00 | 0 | −002 | −008 | −030 | −013 | −034 | −014 | −014 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.34 | |

Regression Analyses

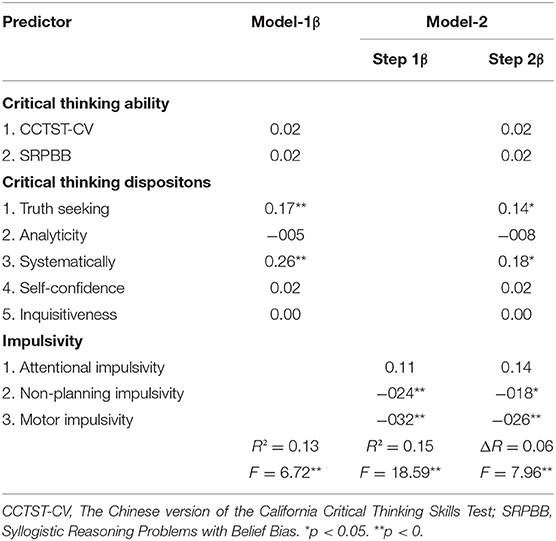

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the effects of CT skill and disposition on mental health. Before conducting the analyses, scores in DASS-21 and UPI were reversed so that high scores reflected high levels of mental health. Table 2 presents the results of hierarchical regression. In model 1, the sum of the Z-score of DASS-21 and UPI served as the dependent variable. Scores in the CT ability tests and scores in the five dimensions of CCTDI served as predictors. CT skill and disposition explained 13% of the variance in mental health. CT skills did not significantly predict mental health. Two dimensions of dispositions (truth seeking and systematicity) exerted significantly positive effects on mental health. Model 2 examined whether CT predicted mental health after controlling for impulsivity. The model containing only impulsivity scores (see model-2 step 1 in Table 2 ) explained 15% of the variance in mental health. Non-planning impulsivity and motor impulsivity showed significantly negative effects on mental health. The CT variables on the second step explained a significantly unique variance (6%) of CT (see model-2 step 2). This suggests that CT skill and disposition together explained the unique variance in mental health after controlling for impulsivity. 1

Hierarchical regression models predicting mental health from critical thinking skills, critical thinking dispositions, and impulsivity ( N = 314).

| 1. CCTST-CV | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| 2. SRPBB | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| 1. Truth seeking | 0.17 | 0.14 | |

| 2. Analyticity | −005 | −008 | |

| 3. Systematically | 0.26 | 0.18 | |

| 4. Self-confidence | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| 5. Inquisitiveness | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 1. Attentional impulsivity | 0.11 | 0.14 | |

| 2. Non-planning impulsivity | −024 | −018 | |

| 3. Motor impulsivity | −032 | −026 | |

| = 0.13 | = 0.15 | Δ = 0.06 | |

| = 6.72 | = 18.59 | = 7.96 | |

CCTST-CV, The Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test; SRPBB, Syllogistic Reasoning Problems with Belief Bias .

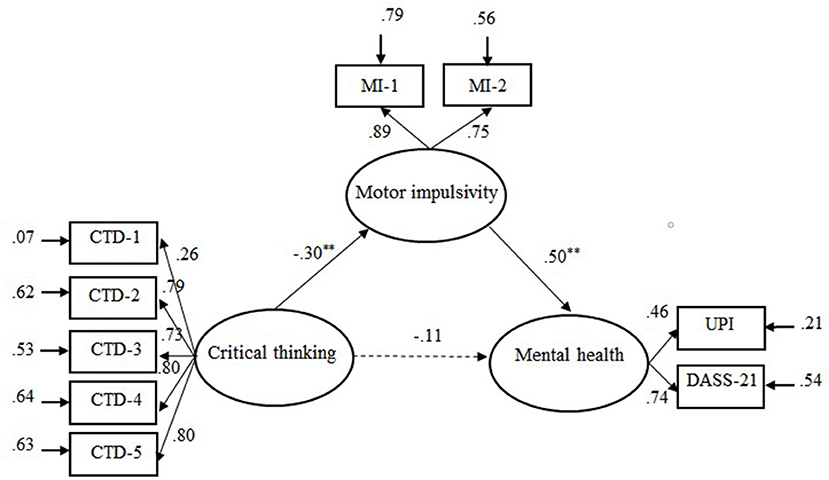

Structural equation modeling was performed to examine whether impulsivity mediated the relationship between CT disposition (CT ability was not included since it did not significantly predict mental health) and mental health. Since the regression results showed that only motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity significantly predicted mental health, we examined two mediation models with either motor impulsivity or non-planning impulsivity as the hypothesized mediator. The item scores in the motor impulsivity subscale were randomly divided into two indicators of motor impulsivity, as were the scores in the non-planning subscale. Scores of DASS-21 and UPI served as indicators of mental health and dimensions of CCTDI as indicators of CT disposition. In addition, a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples was established to test for direct and indirect effects. Amos 22.0 was used for the above analyses.

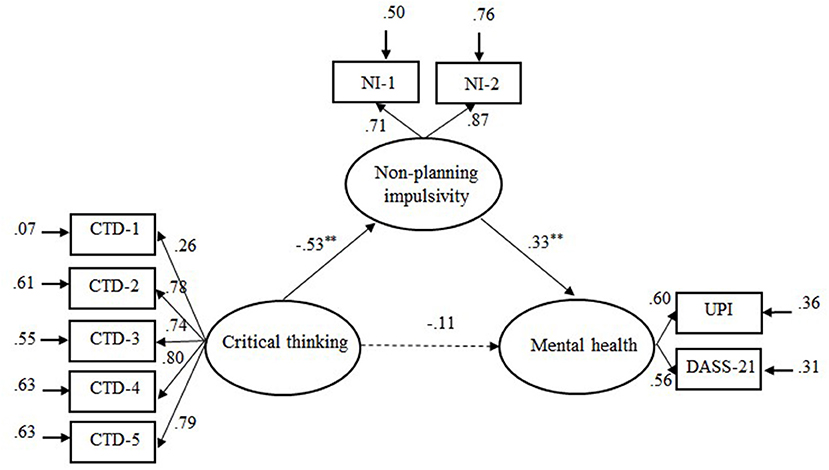

The mediation model that included motor impulsivity (see Figure 1 ) showed an acceptable fit, χ ( 23 ) 2 = 64.71, RMSEA = 0.076, CFI = 0.96, GFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.073. Mediation analyses indicated that the 95% boot confidence intervals of the indirect effect and the direct effect were (0.07, 0.26) and (−0.08, 0.32), respectively. As Hayes ( 2009 ) indicates, an effect is significant if zero is not between the lower and upper bounds in the 95% confidence interval. Accordingly, the indirect effect between CT disposition and mental health was significant, while the direct effect was not significant. Thus, motor impulsivity completely mediated the relationship between CT disposition and mental health.

Illustration of the mediation model: Motor impulsivity as mediator variable between critical thinking dispositions and mental health. CTD-l = Truth seeking; CTD-2 = Analyticity; CTD-3 = Systematically; CTD-4 = Self-confidence; CTD-5 = Inquisitiveness. MI-I and MI-2 were sub-scores of motor impulsivity. Solid line represents significant links and dotted line non-significant links. ** p < 0.01.

The mediation model, which included non-planning impulsivity (see Figure 2 ), also showed an acceptable fit to the data, χ ( 23 ) 2 = 52.75, RMSEA = 0.064, CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.97, NNFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.06. The 95% boot confidence intervals of the indirect effect and the direct effect were (0.05, 0.33) and (−0.04, 0.38), respectively, indicating that non-planning impulsivity completely mediated the relationship between CT disposition and mental health.

Illustration of the mediation model: Non-planning impulsivity asmediator variable between critical thinking dispositions and mental health. CTD-l = Truth seeking; CTD-2 = Analyticity; CTD-3 = Systematically; CTD-4 = Self-confidence; CTD-5 = Inquisitiveness. NI-I and NI-2 were sub-scores of Non-planning impulsivity. Solid line represents significant links and dotted line non-significant links. ** p < 0.01.

This study examined how critical thinking skill and disposition are related to mental health. Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems are in part due to a lack of CT. However, empirical evidence for the hypothesized relationship between CT and mental health is relatively scarce. This study explored whether and how CT ability and disposition are associated with mental health. The results, based on a university student sample, indicated that CT skill and disposition explained a unique variance in mental health. Furthermore, the effect of CT disposition on mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity. The finding that CT exerted a significant effect on mental health was in accordance with previous studies reporting negative correlations between CT disposition and mental disorders such as anxiety (Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ). One reason lies in the assumption that CT disposition is usually referred to as personality traits or habits of mind that are a remarkable predictor of mental health (e.g., Benzi et al., 2019 ). This study further found that of the five CT dispositions, only truth-seeking and systematicity were associated with individual differences in mental health. This was not surprising, since the truth-seeking items mainly assess one's inclination to crave for the best knowledge in a given context and to reflect more about additional facts, reasons, or opinions, even if this requires changing one's mind about certain issues. The systematicity items target one's disposition to approach problems in an orderly and focused way. Individuals with high levels of truth-seeking and systematicity are more likely to adopt a comprehensive, reflective, and controlled way of thinking, which is what cognitive therapy aims to achieve by shifting from an automatic mode of processing to a more reflective and controlled mode.

Another important finding was that motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity mediated the effect of CT disposition on mental health. The reason may be that people lacking CT have less willingness to enter into a systematically analyzing process or deliberative decision-making process, resulting in more frequently rash behaviors or unplanned actions without regard for consequences (Billieux et al., 2010 ; Franco et al., 2017 ). Such responses can potentially have tangible negative consequences (e.g., conflict, aggression, addiction) that may lead to social maladjustment that is regarded as a symptom of mental illness. On the contrary, critical thinkers have a sense of deliberativeness and consider alternate consequences before acting, and this thinking-before-acting mode would logically lead to a decrease in impulsivity, which then decreases the likelihood of problematic behaviors and negative moods.

It should be noted that although the raw correlation between attentional impulsivity and mental health was significant, regression analyses with the three dimensions of impulsivity as predictors showed that attentional impulsivity no longer exerted a significant effect on mental effect after controlling for the other impulsivity dimensions. The insignificance of this effect suggests that the significant raw correlation between attentional impulsivity and mental health was due to the variance it shared with the other impulsivity dimensions (especially with the non-planning dimension, which showed a moderately high correlation with attentional impulsivity, r = 0.67).

Some limitations of this study need to be mentioned. First, the sample involved in this study is considered as a limited sample pool, since all the participants are university students enrolled in statistics and mathematical finance, limiting the generalization of the findings. Future studies are recommended to recruit a more representative sample of university students. A study on generalization to a clinical sample is also recommended. Second, as this study was cross-sectional in nature, caution must be taken in interpreting the findings as causal. Further studies using longitudinal, controlled designs are needed to assess the effectiveness of CT intervention on mental health.

In spite of the limitations mentioned above, the findings of this study have some implications for research and practice intervention. The result that CT contributed to individual differences in mental health provides empirical support for the theory of cognitive behavioral therapy, which focuses on changing irrational thoughts. The mediating role of impulsivity between CT and mental health gives a preliminary account of the mechanism of how CT is associated with mental health. Practically, although there is evidence that CT disposition of students improves because of teaching or training interventions (e.g., Profetto-Mcgrath, 2005 ; Sanja and Krstivoje, 2015 ; Chan, 2019 ), the results showing that two CT disposition dimensions, namely, truth-seeking and systematicity, are related to mental health further suggest that special attention should be paid to cultivating these specific CT dispositions so as to enhance the control of students over impulsive behaviors in their mental health promotions.

Conclusions

This study revealed that two CT dispositions, truth-seeking and systematicity, were associated with individual differences in mental health. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity. These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking is associated with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions (especially truth-seeking and systematicity) and enhancing the control of individuals over impulsive behaviors.

Data Availability Statement

Ethics statement.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by HUST Critical Thinking Research Center (Grant No. 2018CT012). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

XR designed the study and revised the manuscript. ZL collected data and wrote the manuscript. SL assisted in analyzing the data. SS assisted in re-drafting and editing the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1 We re-analyzed the data by controlling for age and gender of the participants in the regression analyses. The results were virtually the same as those reported in the study.

Funding. This work was supported by the Social Science Foundation of China (grant number: BBA200034).

- Barry A., Parvan K., Sarbakhsh P., Safa B., Allahbakhshian A. (2020). Critical thinking in nursing students and its relationship with professional self-concept and relevant factors . Res. Dev. Med. Educ. 9 , 7–7. 10.34172/rdme.2020.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benzi I. M. A., Emanuele P., Rossella D. P., Clarkin J. F., Fabio M. (2019). Maladaptive personality traits and psychological distress in adolescence: the moderating role of personality functioning . Pers. Indiv. Diff. 140 , 33–40. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.026 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Billieux J., Gay P., Rochat L., Van der Linden M. (2010). The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours . Behav. Res. Ther. 48 , 1085–1096. 10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.008 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler H. A., Pentoney C., Bong M. P. (2017). Predicting real-world outcomes: Critical thinking ability is a better predictor of life decisions than intelligence . Think. Skills Creat. 25 , 38–46. 10.1016/j.tsc.2017.06.005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chan C. (2019). Using digital storytelling to facilitate critical thinking disposition in youth civic engagement: a randomized control trial . Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 107 :104522. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104522 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen M. R. A., Hwang G. J. (2020). Effects of a concept mapping-based flipped learning approach on EFL students' English speaking performance, critical thinking awareness and speaking anxiety . Br. J. Educ. Technol. 51 , 817–834. 10.1111/bjet.12887 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cuijpers P. (2019). Targets and outcomes of psychotherapies for mental disorders: anoverview . World Psychiatry. 18 , 276–285. 10.1002/wps.20661 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duffy M. E., Twenge J. M., Joiner T. E. (2019). Trends in mood and anxiety symptoms and suicide-related outcomes among u.s. undergraduates, 2007–2018: evidence from two national surveys . J. Adolesc. Health. 65 , 590–598. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.033 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer C. P. (2017). Critical Thinking: Conceptual Perspectives and Practical Guidelines . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Facione P. A. (1990). Critical Thinking: Astatement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction . Millibrae, CA: The California Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fortgang R. G., Hultman C. M., van Erp T. G. M., Cannon T. D. (2016). Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: testing for shared endophenotypes . Psychol. Med. 46 , 1497–1507. 10.1017/S0033291716000131 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Franco A. R., Costa P. S., Butler H. A., Almeida L. S. (2017). Assessment of undergraduates' real-world outcomes of critical thinking in everyday situations . Psychol. Rep. 120 , 707–720. 10.1177/0033294117701906 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gambrill E. (2005). Critical thinking, evidence-based practice, and mental health, in Mental Disorders in the Social Environment: Critical Perspectives , ed Kirk S. A. (New York, NY: Columbia University Press; ), 247–269. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghanizadeh A. (2017). The interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education . Higher Educ. 74 . 101–114. 10.1007/s10734-016-0031-y [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert T. (2003). Some reflections on critical thinking and mental health . Teach. Phil. 24 , 333–339. 10.5840/teachphil200326446 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gregory R. (1991). Critical thinking for environmental health risk education . Health Educ. Q. 18 , 273–284. 10.1177/109019819101800302 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayes A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the newmillennium . Commun. Monogr. 76 , 408–420. 10.1080/03637750903310360 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hollon S. D., Beck A. T. (2013). Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies, in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, Vol. 6 . ed Lambert M. J. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; ), 393–442. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hong L., Lin C. D., Bray M. A., Kehle T. J. (2010). The measurement of stressful events in chinese college students . Psychol. Sch. 42 , 315–323. 10.1002/pits.20082 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jacobs S. S. (1995). Technical characteristics and some correlates of the california critical thinking skills test, forms a and b . Res. Higher Educ. 36 , 89–108. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kargar F. R., Ajilchi B., Goreyshi M. K., Noohi S. (2013). Effect of creative and critical thinking skills teaching on identity styles and general health in adolescents . Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 84 , 464–469. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.585 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leclair M. C., Lemieux A. J., Roy L., Martin M. S., Latimer E. A., Crocker A. G. (2020). Pathways to recovery among homeless people with mental illness: Is impulsiveness getting in the way? Can. J. Psychiatry. 65 , 473–483. 10.1177/0706743719885477 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee H. S., Kim S., Choi I., Lee K. U. (2008). Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicide ideation and attempts in korean college students . Psychiatry Investig. 5 , 86–93. 10.4306/pi.2008.5.2.86 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li S., Ren X., Schweizer K., Brinthaupt T. M., Wang T. (2021). Executive functions as predictors of critical thinking: behavioral and neural evidence . Learn. Instruct. 71 :101376. 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101376 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin Y. (2018). Developing Critical Thinking in EFL Classes: An Infusion Approach . Singapore: Springer Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Luo Q. X., Yang X. H. (2002). Revising on Chinese version of California critical thinkingskillstest . Psychol. Sci. (Chinese). 25 , 740–741. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mamun M. A., Misti J. M., Hosen I., Mamun F. A. (2021). Suicidal behaviors and university entrance test-related factors: a bangladeshi exploratory study . Persp. Psychiatric Care. 4 , 1–10. 10.1111/ppc.12783 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patton J. H., Stanford M. S., Barratt E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale . J Clin. Psychol. 51 , 768–774. 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)5 1 :63.0.CO;2-1 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peng M. C., Wang G. C., Chen J. L., Chen M. H., Bai H. H., Li S. G., et al.. (2004). Validity and reliability of the Chinese critical thinking disposition inventory . J. Nurs. China (Zhong Hua Hu Li Za Zhi). 39 , 644–647. [ Google Scholar ]

- Profetto-Mcgrath J. (2005). Critical thinking and evidence-based practice . J. Prof. Nurs. 21 , 364–371. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.002 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ren X., Tong Y., Peng P., Wang T. (2020). Critical thinking predicts academic performance beyond general cognitive ability: evidence from adults and children . Intelligence 82 :101487. 10.1016/j.intell.2020.101487 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanja M., Krstivoje S. (2015). Developing critical thinking in elementary mathematics education through a suitable selection of content and overall student performance . Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 180 , 653–659. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.174 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stupple E., Maratos F. A., Elander J., Hunt T. E., Aubeeluck A. V. (2017). Development of the critical thinking toolkit (critt): a measure of student attitudes and beliefs about critical thinking . Think. Skills Creat. 23 , 91–100. 10.1016/j.tsc.2016.11.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suliman W. A., Halabi J. (2007). Critical thinking, self-esteem, and state anxiety of nursing students . Nurse Educ. Today. 27 , 162–168. 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.04.008 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ugwuozor F. O., Otu M. S., Mbaji I. N. (2021). Critical thinking intervention for stress reduction among undergraduates in the Nigerian Universities . Medicine 100 :25030. 10.1097/MD.0000000000025030 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Velotti P., Garofalo C., Petrocchi C., Cavallo F., Popolo R., Dimaggio G. (2016). Alexithymia, emotion dysregulation, impulsivity and aggression: a multiple mediation model . Psychiatry Res. 237 , 296–303. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.025 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang K., Shi H. S., Geng F. L., Zou L. Q., Tan S. P., Wang Y., et al.. (2016). Cross-cultural validation of the depression anxiety stress scale−21 in China . Psychol. Assess. 28 :e88. 10.1037/pas0000207 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- West R. F., Toplak M. E., Stanovich K. E. (2008). Heuristics and biases as measures of critical thinking: associations with cognitive ability and thinking dispositions . J. Educ. Psychol. 100 , 930–941. 10.1037/a0012842 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yoshida T., Ichikawa T., Ishikawa T., Hori M. (1998). Mental health of visually and hearing impaired students from the viewpoint of the University Personality Inventory . Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 52 , 413–418. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yoshinori S., Marcus G. (2013). The dual effects of critical thinking disposition on worry. PLoS ONE 8 :e79714. 10.1371/journal.pone.007971 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang J., Lanza S., Zhang M., Su B. (2015). Structure of the University personality inventory for chinese college students . Psychol. Rep. 116 , 821–839. 10.2466/08.02.PR0.116k26w3 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Critical Thinking Dispositions

Working with students and educators to develop a new scale..

Posted September 11, 2020

Critical thinking (CT) skills and dispositions are increasingly valued in modern society, largely because these skills and dispositions support reasoning and problem-solving in real-world settings (Butler et al., 2012; Halpern, 2013). Historically, CT skills including analysis, evaluation and inference have been extensively researched, and there are a number of instruments available to measure these skills. However, CT dispositions have been somewhat neglected by researchers. Indeed, it’s not easy to find reliable and valid scales to measure CT dispositions.

In broad terms, CT dispositions refer to an inclination, tendency or willingness to perform specific thinking skills. Currently, the only measures of CT dispositions available are the California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI; Facione & Facione, 1992) and the Critical Thinking Disposition Scale (CTDS; Sosu, 2013). The authors of the CCTDI generated a set of items that were assumed to measure seven CT dispositions: Inquisitiveness, Maturity, Self-Confidence , Open-Mindedness, Truth-Seeking, Analyticity, and Systematicity. However, researchers have questioned the reliability and validity of the scale (Walsh, Seldomridge & Badros, 2007). The CCTDI is also a proprietary scale, and in addition to having to pay to use the scale, researchers are not provided with a scoring key indicating which items pertain to which factors.

This is deeply unfortunate, not only for researchers seeking transparency but also for educators who have limited or no funds to support intervention and evaluation work in the classroom. Responding to analytical problems associated with the use of CCTDI, Sosu (2013) developed the Critical Thinking Dispositions Scale (CTDS). This is a two-factor, 11-item instrument, measuring two core CT dispositions: critical openness and reflective scepticism. Initial evaluations suggest the scale has good internal consistency and convergent validity.

The limited availability of reliable and valid CT disposition measures is problematic. Notably, CT is an important outcome of education , with many universities now providing instructional CT courses, which have the potential to support the development of CT skills and CT dispositions. Having access to reliable and valid measures of CT dispositions is vital as it allows for the evaluation of curricula and can be used to inform the iterative design of CT training programmes.

Therefore, we recently set out to develop and evaluate a new measure of CT dispositions . Importantly, the Student-Educator Negotiated CT Dispositions Scale (SENCTDS) is grounded in intensive collective intelligence deliberations involving students and educators, who worked together to develop a consensus-based model of CT dispositions (Dwyer et al., 2016). We also followed the principles of scale design advocated by DeVellis (2012) – we generated CT disposition scale items derived from our collective intelligence work, made modifications to scale items based on expert feedback, performed both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis to identify scale factors, and evaluated the validity of the scale. Part of the validity evaluation involved the analysis of predictive relationships between SENCTDS factors and paranormal and conspiracy beliefs, which were hypothesised based on previous research to be negatively related to CT dispositions. So what did we find?

First, collective intelligence work revealed 13 CT dispositions that students and educators considered important. The 13 CT dispositions are listed and defined below.

An inclination to reflect on one’s behaviour, attitudes, opinions, and motivations; distinguishing what is known and what is unknown, recognising limited knowledge or uncertainty; approaching decision-making with an awareness that some problems are ill-structured, some situations permit more than one plausible conclusion or solution, and good judgment is based on analysis and evaluation, and depends on feasibility, standards, contexts, and available evidence.

Open-Mindedness

An inclination to be cognitively flexible and avoid rigidity in thinking; to tolerate divergent or conflicting views and consider all viewpoints; to detach from one’s own beliefs and consider points of view other to one’s own without bias or self-interest; to be open to feedback by accepting positive feedback and not rejecting criticism or constructive feedback without thoughtful consideration; to amend existing knowledge in light of new ideas and experiences.

Self-Efficacy

The tendency to be confident and trust in one’s own reasoned judgments; to acknowledging one’s sense of self while considering problems and arguments (i.e. life experiences, knowledge, biases, culture, and environment); to be confident and believe in one’s ability to assimilate feedback positively and constructively; to be self-efficacious in leading others in the rational resolution of problems; and to recognise that good reasoning is the key to living a rational life and to creating a more just world.

Truth-Seeking

To have a desire for knowledge; to seek and offer both reasons and objections in an effort to inform and be well-informed; a willingness to challenge popular beliefs and social norms by asking questions (of oneself and others); to be honest and objective about pursuing the truth even if findings do not support one’s self-interest or pre-conceived beliefs; and to change one’s mind about an idea as a result of the desire for truth.

Organisation

An inclination to be orderly, systematic and diligent with information, resources, and time when working on a task or addressing a problem, with awareness of the broader context supporting the maintenance of organised activity.

Resourcefulness

The willingness to utilise existing internal resources to resolve problems; search for additional external resources in order to resolve problems; to switch between solution processes and/or knowledge to seek new ways/information to solve a problem; to make the best of the resources available; to adapt and/or improve if something goes wrong; and to think about how and why it went wrong.

Inclination to challenge ideas; to withhold judgment in advance of engaging all the evidence or when the evidence and reasons are insufficient; to take a position and be able to change position when the evidence and reasons are sufficient; and to look at findings from various perspectives.

Perseverance

To be resilient and motivated to persist at working through complex tasks and the associated frustration and difficulty inherent in such tasks, without giving up; motivation to get the job done correctly; a desire to progress.

Inquisitiveness

An inclination to be curious; desire to fully understand something, discover the answer to a problem, and accept that an answer may not yet be known; a sustained curiosity to understand a task and its associated requirements.

Intrinsic Goal Orientation

Inclined to be positive and enthusiastic towards a task or topic and the process of learning new things; to search for answers as a result of internal motivation, rather than as a result of external, extrinsic rewards.

Attentiveness

Willingness to focus and concentrate; to be aware of surroundings, context, consequences and potential obstacles.

A tendency to visualise, simulate and generate novel ideas; to "think outside the box" (i.e. thinking from different perspectives, with non-normative solutions and novel syntheses).

To seek intelligibility, transparency, lucidity and precision from others and to be clear with respect to the intended meaning of any communication.

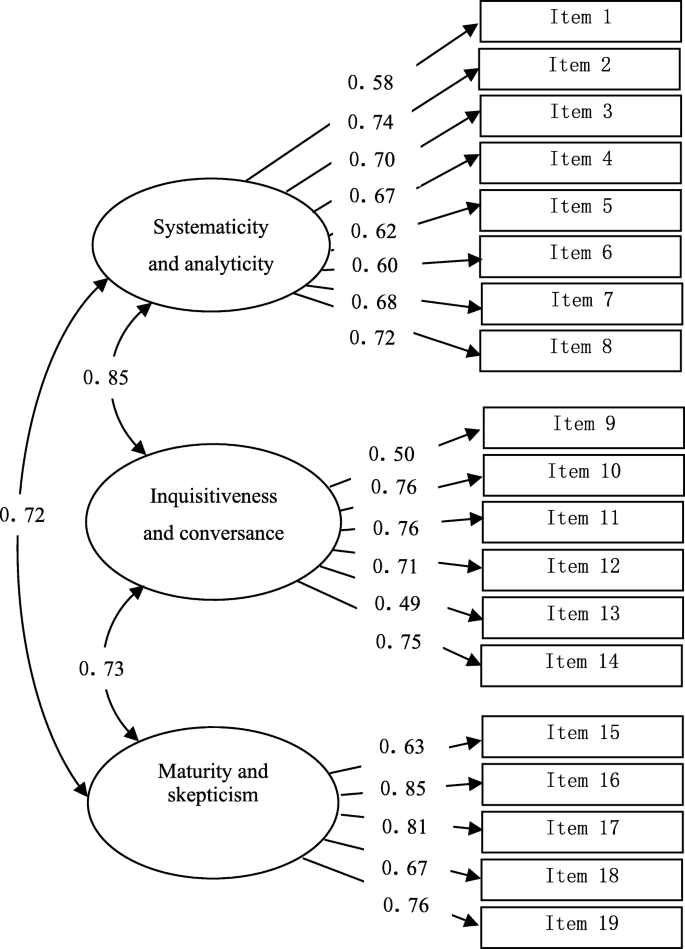

Next, a total of 167 scale items designed to tap into these 13 dispositions were generated and were sent to independent experts for review, specifically, to evaluate both the relevance and clarity of statements as indicators of specific CT dispositions. Based on expert feedback, 101 items measuring the 13 CT dispositions were retained for factor analysis. Exploratory factor analysis first revealed an eight-factor CT disposition structure, and subsequent confirmatory factor analysis indicated a six-factor structure. As such, although we started with 13 CT dispositions derived from collective intelligence work, statistical analyses converged on a six-factor, 21-item SENCTDS measure with good reliability for the total scale (α=.773) and sub-scales (α=.594 - .823). The scale items and associated factors are presented below.

- When a theory, interpretation or conclusion is presented to me, I try to decide if there is good supporting evidence.

- When faced with a decision, I seek as much information as possible.

- I try to gather as much information about a topic before I draw a conclusion about it.

- I find that I'm easily distracted when thinking about a task.

- I find it hard to concentrate when thinking about problems.

- I often miss out on important information because I'm thinking of other things.

- I often daydream when learning a new topic.

Open-mindedness

- Thinking is not about "being flexible," it’s about "being right."

- Being open-minded about different worldviews is less important than people think.

- When attempting to solve complex problems, it’s better to give up fast if you cannot reach a solution.

- I know what I think and believe so it’s not important to dwell on it any further.

- I like to make lists of things I need to do and thoughts I may have.

- I take notes so I can organize my thoughts.

- I make simple charts, diagrams or tables to help me organize large amounts of information.

- I persevere with a task even when it is very difficult.

- Frustration does not stop me from finishing what needs to be done.

- I find it desirable to keep going even if it is sometimes hard.

Intrinsic goal motivation

- I enjoy information that challenges me to think.

- I look forward to learning challenging things.

- Completing difficult tasks is fun for me.

- Even if material is difficult to comprehend, I enjoy dealing with information that arouses my curiosity.

Although more work is needed to further evaluate the factor structure and scale reliability and validity of the SENCTDS, a range of convergent and predictive validity analyses are reported in the published paper.

For example, we used the Revised Paranormal Beliefs Scale (Tobacyk, 2004), and the Generic Conspiracist Beliefs questionnaire (GCB; Brotherton, French & Pickering, 2013) as part of predictive validity testing. Notably, higher scores on the SENCTDS factor perseverance were associated with lower paranormal belief scores. It is increasingly understood that judgments and decisions can be driven by biases and heuristics , which may increase vulnerability to superstitious and paranormal beliefs (Willard & Norenzayan, 2013). However, if one perseveres and works through challenging issues and problems, one may be less susceptible to accepting paranormal beliefs.

Consistent with the idea that persevering with challenging tasks entails a motivation to engage with knowledge, a negative relationship was also found between intrinsic goal motivation and paranormal belief scores. SENCTDS also predicted a number of GCB subscale scores. For example, higher levels of open-mindedness were associated with lower levels of endorsement for conspiracy-related control of information (CI) beliefs, a finding consistent with previous research (Swami, Voracek, Stieger, Tran, & Furnham, 2014).

Perseverance was also found to negatively predict government malfeasance (GM) and malevolent global (MG) conspiracy beliefs. Furthermore, attentiveness was found to negatively predict extra-terrestrial cover-up (ET) beliefs. Attentiveness has previously been linked with deep learning (Lau, Liem & Nie, 2009) and insight problem-solving (Byrne & Murray, 2005), and the findings from our study suggest that dispositional attentiveness to information and arguments may also influence personal beliefs.

In summary, our study provides researchers and educators with a unique conceptualisation of CT dispositions and a new scale that can be used to measure six dispositions. While research has highlighted the importance of thinking dispositions, limited work has focused on CT disposition scale development. The current research points to the SENCTDS as a reliable and valid measure of CT dispositions, which may prove useful in advancing basic and applied research in the area.

Brotherton, R., French, C. C., & Pickering, A. D. (2013). Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: The generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 279. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279

Butler, H. A., Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., Franco, A., Rivas, S. F., Saiz, C., & Almeida, L. F. (2012). Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment and real-world outcomes: Cross-national application. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7(2), 112-121.

Byrne, R. M., & Murray, M. A. (2005, January). Attention and working memory in insight problem-solving. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (Vol. 27, No. 27).

DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications (Vol. 26). Thousand Oaks: Sage publications.

Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., Harney, O. M., & Kavanagh, C. (2016). Facilitating a student-educator conceptual model of dispositions towards critical thinking through interactive management. Educational Technology Research and Development, 1-27.

Facione, P. A., & Facione, N. C. (1992). California critical thinking disposition inventory. Millbrae: California Academic Press

Halpern, D. F. (2013). Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking. New York: Psychology Press.

Lau, S., Liem, A. D., & Nie, Y. (2008). Task‐and self‐related pathways to deep learning: The mediating role of achievement goals, classroom attentiveness, and group participation. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(4), 639-662. doi: https://doi.org/10.1348/000709907X270261

Sosu, E. M. (2013). The development and psychometric validation of a Critical Thinking Disposition Scale. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 9, 107-119. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2012.09.002

Swami, V., Voracek, M., Stieger, S., Tran, U. S., & Furnham, A. (2014). Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories. Cognition, 133(3), 572-585. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.006.

Tobacyk, J. J. (2004). A revised paranormal belief scale. The International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 23(23), 94-98. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2004.23.1.94

Michael Hogan, Ph.D. , is a lecturer in psychology at the National University of Ireland, Galway.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

How do critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition relate to the mental health of university students.

- School of Education, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems associate with deficiencies in critical thinking. However, it currently remains unclear whether both critical thinking skill and critical thinking disposition relate to individual differences in mental health. This study explored whether and how the critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition of university students associate with individual differences in mental health in considering impulsivity that has been revealed to be closely related to both critical thinking and mental health. Regression and structural equation modeling analyses based on a Chinese university student sample ( N = 314, 198 females, M age = 18.65) revealed that critical thinking skill and disposition explained a unique variance of mental health after controlling for impulsivity. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity (acting on the spur of the moment) and non-planning impulsivity (making decisions without careful forethought). These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking associate with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions and enhancing their control over impulsive behavior.

Introduction

Although there is no consistent definition of critical thinking (CT), it is usually described as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanations of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations that judgment is based upon” ( Facione, 1990 , p. 2). This suggests that CT is a combination of skills and dispositions. The skill aspect mainly refers to higher-order cognitive skills such as inference, analysis, and evaluation, while the disposition aspect represents one's consistent motivation and willingness to use CT skills ( Dwyer, 2017 ). An increasing number of studies have indicated that CT plays crucial roles in the activities of university students such as their academic performance (e.g., Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), professional work (e.g., Barry et al., 2020 ), and even the ability to cope with life events (e.g., Butler et al., 2017 ). An area that has received less attention is how critical thinking relates to impulsivity and mental health. This study aimed to clarify the relationship between CT (which included both CT skill and CT disposition), impulsivity, and mental health among university students.

Relationship Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

Associating critical thinking with mental health is not without reason, since theories of psychotherapy have long stressed a linkage between mental problems and dysfunctional thinking ( Gilbert, 2003 ; Gambrill, 2005 ; Cuijpers, 2019 ). Proponents of cognitive behavioral therapy suggest that the interpretation by people of a situation affects their emotional, behavioral, and physiological reactions. Those with mental problems are inclined to bias or heuristic thinking and are more likely to misinterpret neutral or even positive situations ( Hollon and Beck, 2013 ). Therefore, a main goal of cognitive behavioral therapy is to overcome biased thinking and change maladaptive beliefs via cognitive modification skills such as objective understanding of one's cognitive distortions, analyzing evidence for and against one's automatic thinking, or testing the effect of an alternative way of thinking. Achieving these therapeutic goals requires the involvement of critical thinking, such as the willingness and ability to critically analyze one's thoughts and evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs. In addition to theoretical underpinnings, characteristics of university students also suggest a relationship between CT and mental health. University students are a risky population in terms of mental health. They face many normative transitions (e.g., social and romantic relationships, important exams, financial pressures), which are stressful ( Duffy et al., 2019 ). In particular, the risk increases when students experience academic failure ( Lee et al., 2008 ; Mamun et al., 2021 ). Hong et al. (2010) found that the stress in Chinese college students was primarily related to academic, personal, and negative life events. However, university students are also a population with many resources to work on. Critical thinking can be considered one of the important resources that students are able to use ( Stupple et al., 2017 ). Both CT skills and CT disposition are valuable qualities for college students to possess ( Facione, 1990 ). There is evidence showing that students with a higher level of CT are more successful in terms of academic performance ( Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), and that they are better at coping with stressful events ( Butler et al., 2017 ). This suggests that that students with higher CT are less likely to suffer from mental problems.

Empirical research has reported an association between CT and mental health among college students ( Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ; Kargar et al., 2013 ; Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ; Chen and Hwang, 2020 ; Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ). Most of these studies focused on the relationship between CT disposition and mental health. For example, Suliman and Halabi (2007) reported that the CT disposition of nursing students was positively correlated with their self-esteem, but was negatively correlated with their state anxiety. There is also a research study demonstrating that CT disposition influenced the intensity of worry in college students either by increasing their responsibility to continue thinking or by enhancing the detached awareness of negative thoughts ( Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ). Regarding the relationship between CT ability and mental health, although there has been no direct evidence, there were educational programs examining the effect of teaching CT skills on the mental health of adolescents ( Kargar et al., 2013 ). The results showed that teaching CT skills decreased somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression, and insomnia in adolescents. Another recent CT skill intervention also found a significant reduction in mental stress among university students, suggesting an association between CT skills and mental health ( Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ).

The above research provides preliminary evidence in favor of the relationship between CT and mental health, in line with theories of CT and psychotherapy. However, previous studies have focused solely on the disposition aspect of CT, and its link with mental health. The ability aspect of CT has been largely overlooked in examining its relationship with mental health. Moreover, although the link between CT and mental health has been reported, it remains unknown how CT (including skill and disposition) is associated with mental health.

Impulsivity as a Potential Mediator Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

One important factor suggested by previous research in accounting for the relationship between CT and mental health is impulsivity. Impulsivity is recognized as a pattern of action without regard to consequences. Patton et al. (1995) proposed that impulsivity is a multi-faceted construct that consists of three behavioral factors, namely, non-planning impulsiveness, referring to making a decision without careful forethought; motor impulsiveness, referring to acting on the spur of the moment; and attentional impulsiveness, referring to one's inability to focus on the task at hand. Impulsivity is prominent in clinical problems associated with psychiatric disorders ( Fortgang et al., 2016 ). A number of mental problems are associated with increased impulsivity that is likely to aggravate clinical illnesses ( Leclair et al., 2020 ). Moreover, a lack of CT is correlated with poor impulse control ( Franco et al., 2017 ). Applications of CT may reduce impulsive behaviors caused by heuristic and biased thinking when one makes a decision ( West et al., 2008 ). For example, Gregory (1991) suggested that CT skills enhance the ability of children to anticipate the health or safety consequences of a decision. Given this, those with high levels of CT are expected to take a rigorous attitude about the consequences of actions and are less likely to engage in impulsive behaviors, which may place them at a low risk of suffering mental problems. To the knowledge of the authors, no study has empirically tested whether impulsivity accounts for the relationship between CT and mental health.

This study examined whether CT skill and disposition are related to the mental health of university students; and if yes, how the relationship works. First, we examined the simultaneous effects of CT ability and CT disposition on mental health. Second, we further tested whether impulsivity mediated the effects of CT on mental health. To achieve the goals, we collected data on CT ability, CT disposition, mental health, and impulsivity from a sample of university students. The results are expected to shed light on the mechanism of the association between CT and mental health.

Participants and Procedure

A total of 314 university students (116 men) with an average age of 18.65 years ( SD = 0.67) participated in this study. They were recruited by advertisements from a local university in central China and majoring in statistics and mathematical finance. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Each participant signed a written informed consent describing the study purpose, procedure, and right of free. All the measures were administered in a computer room. The participants were tested in groups of 20–30 by two research assistants. The researchers and research assistants had no formal connections with the participants. The testing included two sections with an interval of 10 min, so that the participants had an opportunity to take a break. In the first section, the participants completed the syllogistic reasoning problems with belief bias (SRPBB), the Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCSTS-CV), and the Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI), respectively. In the second session, they completed the Barrett Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11), Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), and University Personality Inventory (UPI) in the given order.

Measures of Critical Thinking Ability

The Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test was employed to measure CT skills ( Lin, 2018 ). The CCTST is currently the most cited tool for measuring CT skills and includes analysis, assessment, deduction, inductive reasoning, and inference reasoning. The Chinese version included 34 multiple choice items. The dependent variable was the number of correctly answered items. The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST is 0.56 ( Jacobs, 1995 ). The test–retest reliability of CCTST-CV is 0.63 ( p < 0.01) ( Luo and Yang, 2002 ), and correlations between scores of the subscales and the total score are larger than 0.5 ( Lin, 2018 ), supporting the construct validity of the scale. In this study among the university students, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST-CV was 0.5.

The second critical thinking test employed in this study was adapted from the belief bias paradigm ( Li et al., 2021 ). This task paradigm measures the ability to evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs ( West et al., 2008 ), which is a strongly emphasized skill in CT literature. The current test included 20 syllogistic reasoning problems in which the logical conclusion was inconsistent with one's prior knowledge (e.g., “Premise 1: All fruits are sweet. Premise 2: Bananas are not sweet. Conclusion: Bananas are not fruits.” valid conclusion). In addition, four non-conflict items were included as the neutral condition in order to avoid a habitual response from the participants. They were instructed to suppose that all the premises are true and to decide whether the conclusion logically follows from the given premises. The measure showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.83) in a Chinese sample ( Li et al., 2021 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the SRPBB was 0.94.

Measures of Critical Thinking Disposition

The Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory was employed to measure CT disposition ( Peng et al., 2004 ). This scale has been developed in line with the conceptual framework of the California critical thinking disposition inventory. We measured five CT dispositions: truth-seeking (one's objectivity with findings even if this requires changing one's preconceived opinions, e.g., a person inclined toward being truth-seeking might disagree with “I believe what I want to believe.”), inquisitiveness (one's intellectual curiosity. e.g., “No matter what the topic, I am eager to know more about it”), analyticity (the tendency to use reasoning and evidence to solve problems, e.g., “It bothers me when people rely on weak arguments to defend good ideas”), systematically (the disposition of being organized and orderly in inquiry, e.g., “I always focus on the question before I attempt to answer it”), and CT self-confidence (the trust one places in one's own reasoning processes, e.g., “I appreciate my ability to think precisely”). Each disposition aspect contained 10 items, which the participants rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale. This measure has shown high internal consistency (overall Cronbach's α = 0.9) ( Peng et al., 2004 ). In this study, the CCTDI scale was assessed at Cronbach's α = 0.89, indicating good reliability.

Measure of Impulsivity

The well-known Barrett Impulsivity Scale ( Patton et al., 1995 ) was employed to assess three facets of impulsivity: non-planning impulsivity (e.g., “I plan tasks carefully”); motor impulsivity (e.g., “I act on the spur of the moment”); attentional impulsivity (e.g., “I concentrate easily”). The scale includes 30 statements, and each statement is rated on a 5-point scale. The subscales of non-planning impulsivity and attentional impulsivity were reversely scored. The BIS-11 has good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.81, Velotti et al., 2016 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the BIS-11 was 0.83.

Measures of Mental Health

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 was used to assess mental health problems such as depression (e.g., “I feel that life is meaningless”), anxiety (e.g., “I find myself getting agitated”), and stress (e.g., “I find it difficult to relax”). Each dimension included seven items, which the participants were asked to rate on a 4-point scale. The Chinese version of the DASS-21 has displayed a satisfactory factor structure and internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92, Wang et al., 2016 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the DASS-21 was 0.94.

The University Personality Inventory that has been commonly used to screen for mental problems of college students ( Yoshida et al., 1998 ) was also used for measuring mental health. The 56 symptom-items assessed whether an individual has experienced the described symptom during the past year (e.g., “a lack of interest in anything”). The UPI showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92) in a Chinese sample ( Zhang et al., 2015 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the UPI was 0.85.

Statistical Analyses

We first performed analyses to detect outliers. Any observation exceeding three standard deviations from the means was replaced with a value that was three standard deviations. This procedure affected no more than 5‰ of observations. Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which facets of critical thinking were related to mental health. In addition, structural equation modeling with Amos 22.0 was performed to assess the latent relationship between CT, impulsivity, and mental health.