15 Definitions of Management by Different Authors and Thinkers

Definitions of Management

Management is a process in which the activities of the organizations are managed in a way that ensures the organizational goals are met within desired standards. It is the basis of every organization .

Many management thinkers have defined the concept of management in many ways. Here, we have made a list of 15 definitions of management by different management scholars. Let’s look at them.

1.) According to Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915) , – “Management is the art of knowing what you want to do and then seeing that you do it in the best and the cheapest way . “

2.) According to George R. Terry (1909-1979) , “Management is a distinct process consisting of planning , organizing, actuating and controlling, performed to determine and accomplish the stated objective by the use of human beings and other resources.”

3.) Definition of management According to Harold Koontz (1909-1984), – “Management is the art of getting things done through others and with formally organized groups. It is the art of creating an environment in which people can perform and individuals can cooperate on the attainment of group goals.”

4.) Peter Ferdinand Drucker (1909-2005) “Management may be defined as the process by means of which the purpose and objectives of a particular human group are determined, clarified, and effectuated. Management is a multipurpose organ that manages a business and manages, and the manager manages workers and work.

5.) One popular definition of management by Mary Parker Follett (1868-1933). “Management is the art of getting things done through people.”

6.) Henri Fayol (1841-1925) – “Management is to forecast, to plan, to organize, to command, to co-ordinate and control activities of others.”

7.) Louis Allen ‘s definition of management is one of the best, shortest, and sweetest. According to him “Management is what a manager does .”

8.) “Management is the art of directing and inspiring people”. – J. D. Moony and A. C. Railey

9. Koontz O Donnel – Management is the art of getting things done through and with people in formally organized groups.

10.) Harold Koontz & Heinz Weihrich – Management is the process of designing and maintaining an environment in which individuals, working together, in groups, efficiently accomplish selected aims.

11. George R. Terry & Stephen G. Franklin – Management is a distinct process consisting of activities of planning, organizing , actuating, and controlling performed to determine and accomplish stated objectives with the use of human beings and other resources.

12. Ivancevich, Donnely, and Gibson – Management is the process undertaken by one or more persons to coordinate the activities of the persons to achieve results not attainable by any person acting alone.

13. SP Robbins, Mary Coulter, and Neharika Bohra – Management involves coordinating and overseeing the work activities of others so that their activities are completed effectively and efficiently.

14.) Ricky W. Griffin – Management is a set of activities (including planning and decision-making, organizing, leading, and controlling ) directed at organizational resources (human, financial, physical, and information) with the aim of achieving organizational goals in an efficient and effective manner.

15.) According to Joseph Massie – “Management is defined as the process by which a cooperative group directs action towards common goals”.

Read Next: Why Management is Called an Art?

Sujan Chaudhary is a BBA graduate. He loves to share his business knowledge with the rest of the world. While not writing, he will be found reading and exploring the world.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

TheMBAins.com is a one-stop MBA knowledge base. We strive to provide insightful knowledge that will help you enhance your business knowledge.

Quick Links

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Support Links

- Organizational Behavior

- Entrepreneurship

- Human Resource

- Privacy Policy

Home » Assignment – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Assignment – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Assignment is a task given to students by a teacher or professor, usually as a means of assessing their understanding and application of course material. Assignments can take various forms, including essays, research papers, presentations, problem sets, lab reports, and more.

Assignments are typically designed to be completed outside of class time and may require independent research, critical thinking, and analysis. They are often graded and used as a significant component of a student’s overall course grade. The instructions for an assignment usually specify the goals, requirements, and deadlines for completion, and students are expected to meet these criteria to earn a good grade.

History of Assignment

The use of assignments as a tool for teaching and learning has been a part of education for centuries. Following is a brief history of the Assignment.

- Ancient Times: Assignments such as writing exercises, recitations, and memorization tasks were used to reinforce learning.

- Medieval Period : Universities began to develop the concept of the assignment, with students completing essays, commentaries, and translations to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the subject matter.

- 19th Century : With the growth of schools and universities, assignments became more widespread and were used to assess student progress and achievement.

- 20th Century: The rise of distance education and online learning led to the further development of assignments as an integral part of the educational process.

- Present Day: Assignments continue to be used in a variety of educational settings and are seen as an effective way to promote student learning and assess student achievement. The nature and format of assignments continue to evolve in response to changing educational needs and technological innovations.

Types of Assignment

Here are some of the most common types of assignments:

An essay is a piece of writing that presents an argument, analysis, or interpretation of a topic or question. It usually consists of an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Essay structure:

- Introduction : introduces the topic and thesis statement

- Body paragraphs : each paragraph presents a different argument or idea, with evidence and analysis to support it

- Conclusion : summarizes the key points and reiterates the thesis statement

Research paper

A research paper involves gathering and analyzing information on a particular topic, and presenting the findings in a well-structured, documented paper. It usually involves conducting original research, collecting data, and presenting it in a clear, organized manner.

Research paper structure:

- Title page : includes the title of the paper, author’s name, date, and institution

- Abstract : summarizes the paper’s main points and conclusions

- Introduction : provides background information on the topic and research question

- Literature review: summarizes previous research on the topic

- Methodology : explains how the research was conducted

- Results : presents the findings of the research

- Discussion : interprets the results and draws conclusions

- Conclusion : summarizes the key findings and implications

A case study involves analyzing a real-life situation, problem or issue, and presenting a solution or recommendations based on the analysis. It often involves extensive research, data analysis, and critical thinking.

Case study structure:

- Introduction : introduces the case study and its purpose

- Background : provides context and background information on the case

- Analysis : examines the key issues and problems in the case

- Solution/recommendations: proposes solutions or recommendations based on the analysis

- Conclusion: Summarize the key points and implications

A lab report is a scientific document that summarizes the results of a laboratory experiment or research project. It typically includes an introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

Lab report structure:

- Title page : includes the title of the experiment, author’s name, date, and institution

- Abstract : summarizes the purpose, methodology, and results of the experiment

- Methods : explains how the experiment was conducted

- Results : presents the findings of the experiment

Presentation

A presentation involves delivering information, data or findings to an audience, often with the use of visual aids such as slides, charts, or diagrams. It requires clear communication skills, good organization, and effective use of technology.

Presentation structure:

- Introduction : introduces the topic and purpose of the presentation

- Body : presents the main points, findings, or data, with the help of visual aids

- Conclusion : summarizes the key points and provides a closing statement

Creative Project

A creative project is an assignment that requires students to produce something original, such as a painting, sculpture, video, or creative writing piece. It allows students to demonstrate their creativity and artistic skills.

Creative project structure:

- Introduction : introduces the project and its purpose

- Body : presents the creative work, with explanations or descriptions as needed

- Conclusion : summarizes the key elements and reflects on the creative process.

Examples of Assignments

Following are Examples of Assignment templates samples:

Essay template:

I. Introduction

- Hook: Grab the reader’s attention with a catchy opening sentence.

- Background: Provide some context or background information on the topic.

- Thesis statement: State the main argument or point of your essay.

II. Body paragraphs

- Topic sentence: Introduce the main idea or argument of the paragraph.

- Evidence: Provide evidence or examples to support your point.

- Analysis: Explain how the evidence supports your argument.

- Transition: Use a transition sentence to lead into the next paragraph.

III. Conclusion

- Restate thesis: Summarize your main argument or point.

- Review key points: Summarize the main points you made in your essay.

- Concluding thoughts: End with a final thought or call to action.

Research paper template:

I. Title page

- Title: Give your paper a descriptive title.

- Author: Include your name and institutional affiliation.

- Date: Provide the date the paper was submitted.

II. Abstract

- Background: Summarize the background and purpose of your research.

- Methodology: Describe the methods you used to conduct your research.

- Results: Summarize the main findings of your research.

- Conclusion: Provide a brief summary of the implications and conclusions of your research.

III. Introduction

- Background: Provide some background information on the topic.

- Research question: State your research question or hypothesis.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of your research.

IV. Literature review

- Background: Summarize previous research on the topic.

- Gaps in research: Identify gaps or areas that need further research.

V. Methodology

- Participants: Describe the participants in your study.

- Procedure: Explain the procedure you used to conduct your research.

- Measures: Describe the measures you used to collect data.

VI. Results

- Quantitative results: Summarize the quantitative data you collected.

- Qualitative results: Summarize the qualitative data you collected.

VII. Discussion

- Interpretation: Interpret the results and explain what they mean.

- Implications: Discuss the implications of your research.

- Limitations: Identify any limitations or weaknesses of your research.

VIII. Conclusion

- Review key points: Summarize the main points you made in your paper.

Case study template:

- Background: Provide background information on the case.

- Research question: State the research question or problem you are examining.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of the case study.

II. Analysis

- Problem: Identify the main problem or issue in the case.

- Factors: Describe the factors that contributed to the problem.

- Alternative solutions: Describe potential solutions to the problem.

III. Solution/recommendations

- Proposed solution: Describe the solution you are proposing.

- Rationale: Explain why this solution is the best one.

- Implementation: Describe how the solution can be implemented.

IV. Conclusion

- Summary: Summarize the main points of your case study.

Lab report template:

- Title: Give your report a descriptive title.

- Date: Provide the date the report was submitted.

- Background: Summarize the background and purpose of the experiment.

- Methodology: Describe the methods you used to conduct the experiment.

- Results: Summarize the main findings of the experiment.

- Conclusion: Provide a brief summary of the implications and conclusions

- Background: Provide some background information on the experiment.

- Hypothesis: State your hypothesis or research question.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of the experiment.

IV. Materials and methods

- Materials: List the materials and equipment used in the experiment.

- Procedure: Describe the procedure you followed to conduct the experiment.

- Data: Present the data you collected in tables or graphs.

- Analysis: Analyze the data and describe the patterns or trends you observed.

VI. Discussion

- Implications: Discuss the implications of your findings.

- Limitations: Identify any limitations or weaknesses of the experiment.

VII. Conclusion

- Restate hypothesis: Summarize your hypothesis or research question.

- Review key points: Summarize the main points you made in your report.

Presentation template:

- Attention grabber: Grab the audience’s attention with a catchy opening.

- Purpose: Explain the purpose of your presentation.

- Overview: Provide an overview of what you will cover in your presentation.

II. Main points

- Main point 1: Present the first main point of your presentation.

- Supporting details: Provide supporting details or evidence to support your point.

- Main point 2: Present the second main point of your presentation.

- Main point 3: Present the third main point of your presentation.

- Summary: Summarize the main points of your presentation.

- Call to action: End with a final thought or call to action.

Creative writing template:

- Setting: Describe the setting of your story.

- Characters: Introduce the main characters of your story.

- Rising action: Introduce the conflict or problem in your story.

- Climax: Present the most intense moment of the story.

- Falling action: Resolve the conflict or problem in your story.

- Resolution: Describe how the conflict or problem was resolved.

- Final thoughts: End with a final thought or reflection on the story.

How to Write Assignment

Here is a general guide on how to write an assignment:

- Understand the assignment prompt: Before you begin writing, make sure you understand what the assignment requires. Read the prompt carefully and make note of any specific requirements or guidelines.

- Research and gather information: Depending on the type of assignment, you may need to do research to gather information to support your argument or points. Use credible sources such as academic journals, books, and reputable websites.

- Organize your ideas : Once you have gathered all the necessary information, organize your ideas into a clear and logical structure. Consider creating an outline or diagram to help you visualize your ideas.

- Write a draft: Begin writing your assignment using your organized ideas and research. Don’t worry too much about grammar or sentence structure at this point; the goal is to get your thoughts down on paper.

- Revise and edit: After you have written a draft, revise and edit your work. Make sure your ideas are presented in a clear and concise manner, and that your sentences and paragraphs flow smoothly.

- Proofread: Finally, proofread your work for spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors. It’s a good idea to have someone else read over your assignment as well to catch any mistakes you may have missed.

- Submit your assignment : Once you are satisfied with your work, submit your assignment according to the instructions provided by your instructor or professor.

Applications of Assignment

Assignments have many applications across different fields and industries. Here are a few examples:

- Education : Assignments are a common tool used in education to help students learn and demonstrate their knowledge. They can be used to assess a student’s understanding of a particular topic, to develop critical thinking skills, and to improve writing and research abilities.

- Business : Assignments can be used in the business world to assess employee skills, to evaluate job performance, and to provide training opportunities. They can also be used to develop business plans, marketing strategies, and financial projections.

- Journalism : Assignments are often used in journalism to produce news articles, features, and investigative reports. Journalists may be assigned to cover a particular event or topic, or to research and write a story on a specific subject.

- Research : Assignments can be used in research to collect and analyze data, to conduct experiments, and to present findings in written or oral form. Researchers may be assigned to conduct research on a specific topic, to write a research paper, or to present their findings at a conference or seminar.

- Government : Assignments can be used in government to develop policy proposals, to conduct research, and to analyze data. Government officials may be assigned to work on a specific project or to conduct research on a particular topic.

- Non-profit organizations: Assignments can be used in non-profit organizations to develop fundraising strategies, to plan events, and to conduct research. Volunteers may be assigned to work on a specific project or to help with a particular task.

Purpose of Assignment

The purpose of an assignment varies depending on the context in which it is given. However, some common purposes of assignments include:

- Assessing learning: Assignments are often used to assess a student’s understanding of a particular topic or concept. This allows educators to determine if a student has mastered the material or if they need additional support.

- Developing skills: Assignments can be used to develop a wide range of skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, research, and communication. Assignments that require students to analyze and synthesize information can help to build these skills.

- Encouraging creativity: Assignments can be designed to encourage students to be creative and think outside the box. This can help to foster innovation and original thinking.

- Providing feedback : Assignments provide an opportunity for teachers to provide feedback to students on their progress and performance. Feedback can help students to understand where they need to improve and to develop a growth mindset.

- Meeting learning objectives : Assignments can be designed to help students meet specific learning objectives or outcomes. For example, a writing assignment may be designed to help students improve their writing skills, while a research assignment may be designed to help students develop their research skills.

When to write Assignment

Assignments are typically given by instructors or professors as part of a course or academic program. The timing of when to write an assignment will depend on the specific requirements of the course or program, but in general, assignments should be completed within the timeframe specified by the instructor or program guidelines.

It is important to begin working on assignments as soon as possible to ensure enough time for research, writing, and revisions. Waiting until the last minute can result in rushed work and lower quality output.

It is also important to prioritize assignments based on their due dates and the amount of work required. This will help to manage time effectively and ensure that all assignments are completed on time.

In addition to assignments given by instructors or professors, there may be other situations where writing an assignment is necessary. For example, in the workplace, assignments may be given to complete a specific project or task. In these situations, it is important to establish clear deadlines and expectations to ensure that the assignment is completed on time and to a high standard.

Characteristics of Assignment

Here are some common characteristics of assignments:

- Purpose : Assignments have a specific purpose, such as assessing knowledge or developing skills. They are designed to help students learn and achieve specific learning objectives.

- Requirements: Assignments have specific requirements that must be met, such as a word count, format, or specific content. These requirements are usually provided by the instructor or professor.

- Deadline: Assignments have a specific deadline for completion, which is usually set by the instructor or professor. It is important to meet the deadline to avoid penalties or lower grades.

- Individual or group work: Assignments can be completed individually or as part of a group. Group assignments may require collaboration and communication with other group members.

- Feedback : Assignments provide an opportunity for feedback from the instructor or professor. This feedback can help students to identify areas of improvement and to develop their skills.

- Academic integrity: Assignments require academic integrity, which means that students must submit original work and avoid plagiarism. This includes citing sources properly and following ethical guidelines.

- Learning outcomes : Assignments are designed to help students achieve specific learning outcomes. These outcomes are usually related to the course objectives and may include developing critical thinking skills, writing abilities, or subject-specific knowledge.

Advantages of Assignment

There are several advantages of assignment, including:

- Helps in learning: Assignments help students to reinforce their learning and understanding of a particular topic. By completing assignments, students get to apply the concepts learned in class, which helps them to better understand and retain the information.

- Develops critical thinking skills: Assignments often require students to think critically and analyze information in order to come up with a solution or answer. This helps to develop their critical thinking skills, which are important for success in many areas of life.

- Encourages creativity: Assignments that require students to create something, such as a piece of writing or a project, can encourage creativity and innovation. This can help students to develop new ideas and perspectives, which can be beneficial in many areas of life.

- Builds time-management skills: Assignments often come with deadlines, which can help students to develop time-management skills. Learning how to manage time effectively is an important skill that can help students to succeed in many areas of life.

- Provides feedback: Assignments provide an opportunity for students to receive feedback on their work. This feedback can help students to identify areas where they need to improve and can help them to grow and develop.

Limitations of Assignment

There are also some limitations of assignments that should be considered, including:

- Limited scope: Assignments are often limited in scope, and may not provide a comprehensive understanding of a particular topic. They may only cover a specific aspect of a topic, and may not provide a full picture of the subject matter.

- Lack of engagement: Some assignments may not engage students in the learning process, particularly if they are repetitive or not challenging enough. This can lead to a lack of motivation and interest in the subject matter.

- Time-consuming: Assignments can be time-consuming, particularly if they require a lot of research or writing. This can be a disadvantage for students who have other commitments, such as work or extracurricular activities.

- Unreliable assessment: The assessment of assignments can be subjective and may not always accurately reflect a student’s understanding or abilities. The grading may be influenced by factors such as the instructor’s personal biases or the student’s writing style.

- Lack of feedback : Although assignments can provide feedback, this feedback may not always be detailed or useful. Instructors may not have the time or resources to provide detailed feedback on every assignment, which can limit the value of the feedback that students receive.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Data Interpretation – Process, Methods and...

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Thesis – Structure, Example and Writing Guide

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Definition of Random Assignment According to Psychology

Materio / Getty Images

Random assignment refers to the use of chance procedures in psychology experiments to ensure that each participant has the same opportunity to be assigned to any given group in a study to eliminate any potential bias in the experiment at the outset. Participants are randomly assigned to different groups, such as the treatment group versus the control group. In clinical research, randomized clinical trials are known as the gold standard for meaningful results.

Simple random assignment techniques might involve tactics such as flipping a coin, drawing names out of a hat, rolling dice, or assigning random numbers to a list of participants. It is important to note that random assignment differs from random selection .

While random selection refers to how participants are randomly chosen from a target population as representatives of that population, random assignment refers to how those chosen participants are then assigned to experimental groups.

Random Assignment In Research

To determine if changes in one variable will cause changes in another variable, psychologists must perform an experiment. Random assignment is a critical part of the experimental design that helps ensure the reliability of the study outcomes.

Researchers often begin by forming a testable hypothesis predicting that one variable of interest will have some predictable impact on another variable.

The variable that the experimenters will manipulate in the experiment is known as the independent variable , while the variable that they will then measure for different outcomes is known as the dependent variable. While there are different ways to look at relationships between variables, an experiment is the best way to get a clear idea if there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two or more variables.

Once researchers have formulated a hypothesis, conducted background research, and chosen an experimental design, it is time to find participants for their experiment. How exactly do researchers decide who will be part of an experiment? As mentioned previously, this is often accomplished through something known as random selection.

Random Selection

In order to generalize the results of an experiment to a larger group, it is important to choose a sample that is representative of the qualities found in that population. For example, if the total population is 60% female and 40% male, then the sample should reflect those same percentages.

Choosing a representative sample is often accomplished by randomly picking people from the population to be participants in a study. Random selection means that everyone in the group stands an equal chance of being chosen to minimize any bias. Once a pool of participants has been selected, it is time to assign them to groups.

By randomly assigning the participants into groups, the experimenters can be fairly sure that each group will have the same characteristics before the independent variable is applied.

Participants might be randomly assigned to the control group , which does not receive the treatment in question. The control group may receive a placebo or receive the standard treatment. Participants may also be randomly assigned to the experimental group , which receives the treatment of interest. In larger studies, there can be multiple treatment groups for comparison.

There are simple methods of random assignment, like rolling the die. However, there are more complex techniques that involve random number generators to remove any human error.

There can also be random assignment to groups with pre-established rules or parameters. For example, if you want to have an equal number of men and women in each of your study groups, you might separate your sample into two groups (by sex) before randomly assigning each of those groups into the treatment group and control group.

Random assignment is essential because it increases the likelihood that the groups are the same at the outset. With all characteristics being equal between groups, other than the application of the independent variable, any differences found between group outcomes can be more confidently attributed to the effect of the intervention.

Example of Random Assignment

Imagine that a researcher is interested in learning whether or not drinking caffeinated beverages prior to an exam will improve test performance. After randomly selecting a pool of participants, each person is randomly assigned to either the control group or the experimental group.

The participants in the control group consume a placebo drink prior to the exam that does not contain any caffeine. Those in the experimental group, on the other hand, consume a caffeinated beverage before taking the test.

Participants in both groups then take the test, and the researcher compares the results to determine if the caffeinated beverage had any impact on test performance.

A Word From Verywell

Random assignment plays an important role in the psychology research process. Not only does this process help eliminate possible sources of bias, but it also makes it easier to generalize the results of a tested sample of participants to a larger population.

Random assignment helps ensure that members of each group in the experiment are the same, which means that the groups are also likely more representative of what is present in the larger population of interest. Through the use of this technique, psychology researchers are able to study complex phenomena and contribute to our understanding of the human mind and behavior.

Lin Y, Zhu M, Su Z. The pursuit of balance: An overview of covariate-adaptive randomization techniques in clinical trials . Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):21-25. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2015.07.011

Sullivan L. Random assignment versus random selection . In: The SAGE Glossary of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2009. doi:10.4135/9781412972024.n2108

Alferes VR. Methods of Randomization in Experimental Design . SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2012. doi:10.4135/9781452270012

Nestor PG, Schutt RK. Research Methods in Psychology: Investigating Human Behavior. (2nd Ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing Definitions

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A formal definition is based upon a concise, logical pattern that includes as much information as it can within a minimum amount of space. The primary reason to include definitions in your writing is to avoid misunderstanding with your audience. A formal definition consists of three parts:

- The term (word or phrase) to be defined

- The class of object or concept to which the term belongs

- The differentiating characteristics that distinguish it from all others of its class

For example:

- Water ( term ) is a liquid ( class ) made up of molecules of hydrogen and oxygen in the ratio of 2 to 1 ( differentiating characteristics ).

- Comic books ( term ) are sequential and narrative publications ( class ) consisting of illustrations, captions, dialogue balloons, and often focus on super-powered heroes ( differentiating characteristics ).

- Astronomy ( term ) is a branch of scientific study ( class ) primarily concerned with celestial objects inside and outside of the earth's atmosphere ( differentiating characteristics ).

Although these examples should illustrate the manner in which the three parts work together, they are not the most realistic cases. Most readers will already be quite familiar with the concepts of water, comic books, and astronomy. For this reason, it is important to know when and why you should include definitions in your writing.

When to Use Definitions

"Stellar Wobble is a measurable variation of speed wherein a star's velocity is shifted by the gravitational pull of a foreign body."

"Throughout this essay, the term classic gaming will refer specifically to playing video games produced for the Atari, the original Nintendo Entertainment System, and any systems in-between." Note: not everyone may define "classic gaming" within this same time span; therefore, it is important to define your terms

"Pagan can be traced back to Roman military slang for an incompetent soldier. In this sense, Christians who consider themselves soldiers of Christ are using the term not only to suggest a person's secular status but also their lack of bravery.'

Additional Tips for Writing Definitions

- Avoid defining with "X is when" and "X is where" statements. These introductory adverb phrases should be avoided. Define a noun with a noun, a verb with a verb, and so forth.

"Rhyming poetry consists of lines that contain end rhymes." Better: "Rhyming poetry is an artform consisting of lines whose final words consistently contain identical, final stressed vowel sounds."

- Define a word in simple and familiar terms. Your definition of an unfamiliar word should not lead your audience towards looking up more words in order to understand your definition.

- Keep the class portion of your definition small but adequate. It should be large enough to include all members of the term you are defining but no larger. Avoid adding personal details to definitions. Although you may think the story about your Grandfather will perfectly encapsulate the concept of stinginess, your audience may fail to relate. Offering personal definitions may only increase the likeliness of misinterpretation that you are trying to avoid.

Random Assignment in Psychology: Definition & Examples

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

In psychology, random assignment refers to the practice of allocating participants to different experimental groups in a study in a completely unbiased way, ensuring each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group.

In experimental research, random assignment, or random placement, organizes participants from your sample into different groups using randomization.

Random assignment uses chance procedures to ensure that each participant has an equal opportunity of being assigned to either a control or experimental group.

The control group does not receive the treatment in question, whereas the experimental group does receive the treatment.

When using random assignment, neither the researcher nor the participant can choose the group to which the participant is assigned. This ensures that any differences between and within the groups are not systematic at the onset of the study.

In a study to test the success of a weight-loss program, investigators randomly assigned a pool of participants to one of two groups.

Group A participants participated in the weight-loss program for 10 weeks and took a class where they learned about the benefits of healthy eating and exercise.

Group B participants read a 200-page book that explains the benefits of weight loss. The investigator randomly assigned participants to one of the two groups.

The researchers found that those who participated in the program and took the class were more likely to lose weight than those in the other group that received only the book.

Importance

Random assignment ensures that each group in the experiment is identical before applying the independent variable.

In experiments , researchers will manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables. Random assignment increases the likelihood that the treatment groups are the same at the onset of a study.

Thus, any changes that result from the independent variable can be assumed to be a result of the treatment of interest. This is particularly important for eliminating sources of bias and strengthening the internal validity of an experiment.

Random assignment is the best method for inferring a causal relationship between a treatment and an outcome.

Random Selection vs. Random Assignment

Random selection (also called probability sampling or random sampling) is a way of randomly selecting members of a population to be included in your study.

On the other hand, random assignment is a way of sorting the sample participants into control and treatment groups.

Random selection ensures that everyone in the population has an equal chance of being selected for the study. Once the pool of participants has been chosen, experimenters use random assignment to assign participants into groups.

Random assignment is only used in between-subjects experimental designs, while random selection can be used in a variety of study designs.

Random Assignment vs Random Sampling

Random sampling refers to selecting participants from a population so that each individual has an equal chance of being chosen. This method enhances the representativeness of the sample.

Random assignment, on the other hand, is used in experimental designs once participants are selected. It involves allocating these participants to different experimental groups or conditions randomly.

This helps ensure that any differences in results across groups are due to manipulating the independent variable, not preexisting differences among participants.

When to Use Random Assignment

Random assignment is used in experiments with a between-groups or independent measures design.

In these research designs, researchers will manipulate an independent variable to assess its effect on a dependent variable, while controlling for other variables.

There is usually a control group and one or more experimental groups. Random assignment helps ensure that the groups are comparable at the onset of the study.

How to Use Random Assignment

There are a variety of ways to assign participants into study groups randomly. Here are a handful of popular methods:

- Random Number Generator : Give each member of the sample a unique number; use a computer program to randomly generate a number from the list for each group.

- Lottery : Give each member of the sample a unique number. Place all numbers in a hat or bucket and draw numbers at random for each group.

- Flipping a Coin : Flip a coin for each participant to decide if they will be in the control group or experimental group (this method can only be used when you have just two groups)

- Roll a Die : For each number on the list, roll a dice to decide which of the groups they will be in. For example, assume that rolling 1, 2, or 3 places them in a control group and rolling 3, 4, 5 lands them in an experimental group.

When is Random Assignment not used?

- When it is not ethically permissible: Randomization is only ethical if the researcher has no evidence that one treatment is superior to the other or that one treatment might have harmful side effects.

- When answering non-causal questions : If the researcher is just interested in predicting the probability of an event, the causal relationship between the variables is not important and observational designs would be more suitable than random assignment.

- When studying the effect of variables that cannot be manipulated: Some risk factors cannot be manipulated and so it would not make any sense to study them in a randomized trial. For example, we cannot randomly assign participants into categories based on age, gender, or genetic factors.

Drawbacks of Random Assignment

While randomization assures an unbiased assignment of participants to groups, it does not guarantee the equality of these groups. There could still be extraneous variables that differ between groups or group differences that arise from chance. Additionally, there is still an element of luck with random assignments.

Thus, researchers can not produce perfectly equal groups for each specific study. Differences between the treatment group and control group might still exist, and the results of a randomized trial may sometimes be wrong, but this is absolutely okay.

Scientific evidence is a long and continuous process, and the groups will tend to be equal in the long run when data is aggregated in a meta-analysis.

Additionally, external validity (i.e., the extent to which the researcher can use the results of the study to generalize to the larger population) is compromised with random assignment.

Random assignment is challenging to implement outside of controlled laboratory conditions and might not represent what would happen in the real world at the population level.

Random assignment can also be more costly than simple observational studies, where an investigator is just observing events without intervening with the population.

Randomization also can be time-consuming and challenging, especially when participants refuse to receive the assigned treatment or do not adhere to recommendations.

What is the difference between random sampling and random assignment?

Random sampling refers to randomly selecting a sample of participants from a population. Random assignment refers to randomly assigning participants to treatment groups from the selected sample.

Does random assignment increase internal validity?

Yes, random assignment ensures that there are no systematic differences between the participants in each group, enhancing the study’s internal validity .

Does random assignment reduce sampling error?

Yes, with random assignment, participants have an equal chance of being assigned to either a control group or an experimental group, resulting in a sample that is, in theory, representative of the population.

Random assignment does not completely eliminate sampling error because a sample only approximates the population from which it is drawn. However, random sampling is a way to minimize sampling errors.

When is random assignment not possible?

Random assignment is not possible when the experimenters cannot control the treatment or independent variable.

For example, if you want to compare how men and women perform on a test, you cannot randomly assign subjects to these groups.

Participants are not randomly assigned to different groups in this study, but instead assigned based on their characteristics.

Does random assignment eliminate confounding variables?

Yes, random assignment eliminates the influence of any confounding variables on the treatment because it distributes them at random among the study groups. Randomization invalidates any relationship between a confounding variable and the treatment.

Why is random assignment of participants to treatment conditions in an experiment used?

Random assignment is used to ensure that all groups are comparable at the start of a study. This allows researchers to conclude that the outcomes of the study can be attributed to the intervention at hand and to rule out alternative explanations for study results.

Further Reading

- Bogomolnaia, A., & Moulin, H. (2001). A new solution to the random assignment problem . Journal of Economic theory , 100 (2), 295-328.

- Krause, M. S., & Howard, K. I. (2003). What random assignment does and does not do . Journal of Clinical Psychology , 59 (7), 751-766.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of assignment

task , duty , job , chore , stint , assignment mean a piece of work to be done.

task implies work imposed by a person in authority or an employer or by circumstance.

duty implies an obligation to perform or responsibility for performance.

job applies to a piece of work voluntarily performed; it may sometimes suggest difficulty or importance.

chore implies a minor routine activity necessary for maintaining a household or farm.

stint implies a carefully allotted or measured quantity of assigned work or service.

assignment implies a definite limited task assigned by one in authority.

Examples of assignment in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'assignment.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

see assign entry 1

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Phrases Containing assignment

- self - assignment

Dictionary Entries Near assignment

Cite this entry.

“Assignment.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/assignment. Accessed 26 Sep. 2024.

Legal Definition

Legal definition of assignment, more from merriam-webster on assignment.

Nglish: Translation of assignment for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of assignment for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, plural and possessive names: a guide, the difference between 'i.e.' and 'e.g.', more commonly misspelled words, absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, weird words for autumn time, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, 15 words that used to mean something different, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, games & quizzes.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of assignment in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- It was a jammy assignment - more of a holiday really.

- He took this award-winning photograph while on assignment in the Middle East .

- His two-year assignment to the Mexico office starts in September .

- She first visited Norway on assignment for the winter Olympics ten years ago.

- He fell in love with the area after being there on assignment for National Geographic in the 1950s.

- act as something phrasal verb

- all work and no play (makes Jack a dull boy) idiom

- be at work idiom

- be in work idiom

- housekeeping

- in the line of duty idiom

- undertaking

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

assignment | American Dictionary

Assignment | business english, examples of assignment, collocations with assignment.

These are words often used in combination with assignment .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of assignment

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

nine to five

describing or relating to work that begins at nine o'clock in the morning and finishes at five, the hours worked in many offices from Monday to Friday

It’s as clear as mud! (Words and expressions that mean ‘difficult to understand’)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- on assignment

- American Noun

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

To add assignment to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add assignment to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

The Author’s Purpose for students and teachers

What Is The Author’s Purpose?

When discussing the author’s purpose, we refer to the ‘why’ behind their writing. What motivated the author to produce their work? What is their intent, and what do they hope to achieve?

The author’s purpose is the reason they decided to write about something in the first place.

There are many reasons a writer puts pen to paper, and students must possess the necessary tools to identify these reasons and intents to react and respond appropriately.

Understanding why authors write is essential for students to navigate the complex landscape of texts effectively. The concept of author’s purpose encompasses the motivations behind a writer’s choice of words, style, and structure. By teaching students to discern these purposes, educators empower them to engage critically with various forms of literature and non-fiction.

Author’s Purpose Definition

The author’s purpose is his or her motivation for writing a text and their intent to Persuade, Inform, Entertain, Explain or Describe something to an audience.

Author’s Purpose Examples and Types

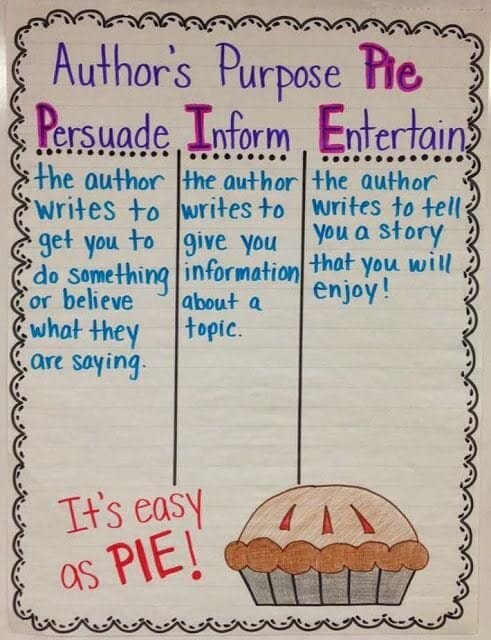

It is universally accepted there are three base categories of the Author’s Purpose: To Persuade, To Inform , and To Entertain . These can easily be remembered with the PIE acronym and should be the starting point on this topic. However, you may also encounter other subcategories depending on who you ask.

This table provides many author’s purpose examples, and we will cover the first five in detail in this article.

| Author’s Purpose | Author’s Purpose Examples |

|---|---|

| : | The author aims to convince the reader to agree with a particular viewpoint or take a specific action. This can be seen in opinion pieces, advertisements, or political speeches. |

| : | The author aims to provide factual information to the reader, such as in textbooks, news articles, or research papers. |

| : | The author aims to engage and amuse the reader through storytelling, humour, or other means. This includes genres such as fiction, poetry, and humour. |

| : | The author’s purpose is to provide step-by-step guidance or directions to the reader. Examples include manuals, how-to guides, and recipes. |

| : | The author uses vivid language to paint a picture in the reader’s mind. This can be found in travel writing, descriptive essays, or literature. |

| : | Some authors write primarily to express themselves, their thoughts, emotions, or experiences. This can be seen in personal essays, journals, or poetry. |

| : | Exploratory writing involves delving into a topic or idea to gain a deeper understanding or to provoke thought. This can be found in philosophical essays, literary analysis, or investigative journalism. |

| : | Authors may write to document events, experiences, or historical periods for posterity. This includes memoirs, autobiographies, and historical accounts. |

Author’s Purpose Teaching Unit

Teach your students ALL ASPECTS of the Author’s Purpose with this fully EDITABLE 63-page Teaching Unit.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ ( 42 reviews )

Author’s Purpose 1: To Persuade

Definition: This is a prevalent purpose of writing, particularly in nonfiction. When a text is written to persuade, it aims to convince the reader of the merits of a particular point of view . In this type of writing, the author attempts to persuade the reader to agree with this point of view and/or subsequently take a particular course of action.

Examples: This purpose can be found in all kinds of writing. It can even be in fiction writing when the author has an agenda, consciously or unconsciously. However, it is most commonly the motivation behind essays, advertisements, and political writing, such as speech and propaganda.

Persuasion is commonly also found in…

- A political speech urges voters to support a particular candidate by presenting arguments for their suitability for the position, policies, and record of achievements.

- An advertisement for a new product that emphasizes its unique features and benefits over competing products, attempting to convince consumers to choose it over alternatives.

- A letter to the editor of a newspaper expressing a strong opinion on a controversial issue and attempting to persuade others to adopt a similar position by presenting compelling evidence and arguments.

How to Identify: To identify when the author’s purpose is to persuade, students should ask themselves if they feel the writer is trying to get them to believe something or take a specific action. They should learn to identify the various tactics and strategies used in persuasive writing, such as repetition, multiple types of supporting evidence, hyperbole, attacking opposing viewpoints, forceful phrases, emotive imagery, and photographs.

We have a complete persuasive writing guide if you want to learn more.

Strategies for being a more PERSUASIVE writer

To become a persuasive writer, students can employ several strategies to convey their arguments and influence their readers effectively. Here are five strategies for persuasive writing:

- Understand Your Audience: Know your target audience and tailor your persuasive arguments to appeal to their interests, values, and beliefs. Consider their potential objections and address them in your writing. Understanding your audience helps you create a more compelling and persuasive piece.

- Use Strong Evidence and Examples: Support your claims with credible evidence, statistics, and real-life examples. Persuasive writing relies on logic and facts to support your arguments. Conduct research to find reliable sources that strengthen your case and make your writing more convincing.

- Craft a Persuasive Structure: Organize your writing clearly and persuasively. Start with a compelling introduction that grabs the reader’s attention and states your main argument. Use body paragraphs to present evidence and supporting points logically. Finish with a strong conclusion that reinforces your main message and calls the reader to take action or adopt your viewpoint.

- Appeal to Emotions: Persuasive writing is not just about logic; emotions are crucial in influencing readers. Use emotional appeals to connect with your audience and evoke empathy, sympathy, or excitement. Be careful not to manipulate emotions but use them to reinforce your argument authentically.

- Anticipate Counterarguments: Acknowledge and address potential counterarguments to show that you have considered different perspectives. By addressing opposing viewpoints, you demonstrate that you have thoroughly thought about the issue and strengthen your credibility as a persuasive writer.

Bonus Tip: Use Persuasive Language: Pay attention to your choice of words and language. Use compelling language that evokes a sense of urgency or importance. Employ rhetorical devices, such as repetition, analogy, and rhetorical questions, to make your writing more persuasive and memorable.

Please encourage students to practice these strategies in their writing in formal essays and everyday persuasive situations. By mastering persuasive writing techniques, students can effectively advocate for their ideas, inspire change, and have a greater impact with their words.

Author’s Purpose 2: To Inform

Definition: When an author aims to inform, they usually wish to enlighten their readership about a real-world topic. Often, they will do this by providing lots of facts. Informational texts impart information to the reader to educate them on a given topic.

Examples: Many types of school books are written with the express purpose of informing the reader, such as encyclopedias, recipe books, newspapers and informative texts…

- A news article reporting on a recent event or development provides factual details about what happened, who was involved, and where and when it occurred.

- A scientific journal article describes a research study’s findings, explaining the methodology, results, and implications for further analysis or practical application.

- A travel guidebook that provides detailed information about a particular destination, including its history, culture, attractions, accommodation options, and practical advice for visitors.

How to Identify: In the process of informing the reader, the author will use facts, which is one surefire way to spot the intent to inform.

However, when the author’s purpose is persuasion, they will also likely provide the reader with some facts to convince them of the merits of their particular case. The main difference between the two ways facts are employed is that when the intention is to inform, facts are presented only to teach the reader. When the author aims to persuade, they commonly mask their opinions amid the facts.

Students must become adept at recognizing ‘hidden’ opinions through practice. Teach your students to beware of persuasion masquerading as information!

Please read our complete guide to learn more about writing an information report.

Strategies for being a more INFORMATIVE writer

To become an informative writer, students can employ several strategies to effectively convey information and knowledge clearly and engagingly. Here are five strategies for informative writing:

- Conduct Thorough Research: Before writing, gather information from credible sources such as books, academic journals, reputable websites, and expert interviews. Use reliable data and evidence to support your points. Ensuring the accuracy and reliability of your information is essential in informative writing.

- Organize Information Logically: Structure your writing clearly and logically. Use headings, subheadings, and bullet points to organize information into easily digestible chunks. A well-structured piece helps readers understand complex topics more quickly.

- Use Clear and Concise Language: Aim for clarity and avoid unnecessary jargon or complex language that might confuse your readers. Use simple and concise sentences to deliver information effectively. Make sure to define any technical terms or concepts unfamiliar to your audience.

- Provide Real-Life Examples: Illustrate your points with real-life examples, case studies, or anecdotes. Concrete examples make abstract concepts more understandable and relatable. They also help to keep the reader engaged throughout the piece.

- Incorporate Visual Aids: Whenever possible, use visual aids such as charts, graphs, diagrams, and images to complement your text. Visual elements enhance understanding and retention of information. Be sure to explain the significance of each visual aid in your writing.

Bonus Tip: Practice Summarization: After completing informative writing, practice summarizing the main points. Being able to summarize your work concisely reinforces your understanding of the topic and helps you identify any gaps in your information.

Encourage students to practice these strategies in various writing tasks, such as research papers, reports, and explanatory essays. By mastering informative writing techniques, students can effectively educate their readers, share knowledge, and contribute meaningfully to their academic and professional pursuits.

Author’s Purpose 3: To Entertain

Definition: When an author’s chief purpose is to entertain the reader, they will endeavour to keep things as interesting as possible. Things happen in books written to entertain, whether in an action-packed plot , inventive characterizations, or sharp dialogue.

Examples: Not surprisingly, much fiction is written to entertain, especially genre fiction. For example, we find entertaining examples in science fiction, romance, and fantasy.

Here are some more entertaining texts to consider.

- A novel that tells a compelling story engages the reader’s emotions and imagination through vivid characters, evocative settings, and unexpected twists and turns.

- A comedy television script that uses humour and wit to amuse the audience, often by poking fun at everyday situations or societal norms.

- A stand-up comedy routine that relies on the comedian’s storytelling ability and comedic timing to entertain the audience, often by commenting on current events or personal experiences.

How to Identify: When writers attempt to entertain or amuse the reader, they use various techniques to engage their attention. They may employ cliffhangers at the end of a chapter, for example. They may weave humour into their story or even have characters tell jokes. In the case of a thriller, an action-packed scene may follow an action-packed scene as the drama builds to a crescendo. Think of the melodrama of a soap opera here rather than the subtle touch of an arthouse masterpiece.

Strategies for being a more ENTERTAINING writer

To become an entertaining writer, students can use several strategies to captivate their readers and keep them engaged. Here are five effective techniques:

- Use Humor: Inject humour to tickle the reader’s funny bone. Incorporate witty remarks, funny anecdotes, or clever wordplay. Humour lightens the tone of your writing and makes it enjoyable to read. However, be mindful of your audience and ensure your humour is appropriate and relevant to the topic.

- Create Engaging Characters: Whether you’re writing a story, essay, or any other type of content, develop compelling and relatable characters. Readers love connecting with well-developed characters with distinct personalities, flaws, and strengths. Use descriptive language to bring them to life and make them memorable.

- Craft Intriguing Beginnings: Grab your reader’s attention from the very first sentence. Start with a compelling hook that sparks curiosity or creates intrigue. An exciting beginning sets the tone for the rest of the piece and encourages the reader to continue reading.

- Build Suspense and Surprise: Incorporate twists, turns, and surprises into your writing to keep readers on their toes. Building suspense creates anticipation and makes readers eager to discover what happens next. Surprise them with unexpected plot developments or revelations to keep them engaged throughout the piece.

- Use Imagery and Vivid Descriptions : Paint vivid pictures with your words to immerse readers in your writing. Use sensory language and descriptive imagery to transport them to different places, evoke emotions, and create a multisensory experience. Readers love to feel like they’re part of the story, and vivid descriptions help achieve that.

Bonus Tip: Read Widely and Analyze: To become an entertaining writer, read a variety of books, articles, and pieces from different genres and authors. Pay attention to the elements that make their writing engaging and entertaining. Analyze their use of humour, character development, suspense, and descriptions. Learning from the work of accomplished writers can inspire and improve your own writing.

By using these strategies and practising regularly, students can become more entertaining writers, captivating their audience and making their writing a joy to read. Remember, the key to entertaining writing is engaging your readers and leaving them with a positive and memorable experience.

Author’s Purpose 4: To Explain

Definition: When writers write to explain, they want to tell the reader how to do something or reveal how something works. This type of writing is about communicating a method or a process.

Examples: Writing to explain can be found in instructions, step-by-step guides, procedural outlines, and recipes such as these…

- A user manual explaining how to operate a piece of machinery or a technical device provides step-by-step instructions and diagrams to help users understand the process.

- A textbook chapter that explains a complex scientific or mathematical concept breaks it into simpler components and provides examples and illustrations to aid comprehension.

- A how-to guide that explains how to complete a specific task or achieve a particular outcome, such as cooking a recipe, gardening, or home repair. It provides a list of materials, step-by-step instructions, and tips to ensure success.

How to Identify: Often, this writing is organized into bulleted or numbered points. As it focuses on telling the reader how to do something, often lots of imperatives will be used within the writing. Diagrams and illustrations are often used to reinforce the text explanations too.

Read our complete guide to explanatory texts here.

Strategies for being a more EXPLANATORY WRITER

To become a more explanatory writer, students can employ several strategies to effectively clarify complex ideas and concepts for their readers. Here are five strategies for explanatory writing:

- Define Technical Terms: When writing about a specialized or technical topic, ensure that you define any relevant terms or jargon that might be unfamiliar to your readers. A clear and concise definition helps readers grasp the meaning of these terms and facilitates better understanding of the content.

- Use Analogies and Comparisons: Use analogies and comparisons to relate complex ideas to more familiar concepts. This technique makes abstract or difficult concepts more relatable and easier to understand. Analogies provide a frame of reference that helps readers connect new information to something they already know.

- Provide Step-by-Step Explanations: Break down complex processes or procedures into step-by-step explanations. This approach helps readers follow the sequence of events or actions and understand the logic behind each step. Use numbered lists or bullet points to make the process visually clear.

- Include Visuals and Diagrams: Supplement your explanatory writing with visual aids such as diagrams, flowcharts, or illustrations. Visuals can enhance understanding and retention of information by visually representing the concepts being discussed.

- Address “Why” and “How”: In explanatory writing, go beyond simply stating “what” happened or what a concept is. Focus on explaining “why” something occurs and “how” it works. Providing the underlying reasons and mechanisms helps readers better understand the subject matter.

Bonus Tip: Review and Revise: After completing your explanatory writing, review your work and assess whether the explanations are clear and comprehensive. Consider seeking feedback from peers or teachers to identify areas needing further clarification or expansion.

Please encourage students to practice these strategies in writing across different subjects and topics. By mastering explanatory writing techniques, students can effectively communicate complex ideas, promote better understanding, and excel academically and professionally.

Author’s Purpose 5: To Describe

Definition: Writers often use words to describe something in more detail than conveyed in a photograph alone. After all, they say a picture paints a thousand words, and text can help get us beyond the one-dimensional appearance of things.

Examples: We can find lots of descriptive writing in obvious places like short stories, novels and other forms of fiction where the writer wishes to paint a picture in the reader’s imagination. We can also find lots of writing with the purpose of description in nonfiction too – in product descriptions, descriptive essays or these text types…

- A travelogue that describes a particular place, highlighting its natural beauty, cultural attractions, and unique characteristics. The author uses sensory language to create a vivid mental picture in the reader’s mind.

- A painting analysis that describes the colors, shapes, textures, and overall impression of a particular artwork. The author uses descriptive language to evoke the emotions and ideas conveyed by the painting.

- A product review that describes the features, benefits, and drawbacks of a particular item. The author uses descriptive language to give the reader a clear sense of the product and whether it might suit their needs.

How to Identify: In the case of fiction writing which describes, the reader will notice the writer using lots of sensory details in the text. Our senses are how we perceive the world, and to describe their imaginary world, writers will draw heavily on language that appeals to these senses. In both fiction and nonfiction, readers will notice that the writer relies heavily on adjectives.

Strategies for being a more descriptive writer

Becoming a descriptive writer is a valuable skill that allows students to paint vivid pictures with words and immerse readers in their stories. Here are five strategies for students to enhance their descriptive writing:

- Sensory Language: Engage the reader’s senses by incorporating sensory language into your writing. Use descriptive adjectives, adverbs, and strong verbs to create a sensory experience for your audience. For example, instead of saying “the flower was pretty,” describe it as “the delicate, fragrant blossom with hues of vibrant pink and a velvety texture.”

- Show, Don’t Tell: Use the “show, don’t tell” technique to make your writing more descriptive and immersive. Rather than stating emotions or characteristics directly, use descriptive details and actions to show them. For instance, instead of saying “she was scared,” describe how “her heart raced, and her hands trembled as she peeked around the dark corner.”

- Use Metaphors and Similes: Integrate metaphors and similes to add depth and creativity to your descriptions. Compare two unrelated things to create a powerful visual image. For example, “the sun dipped below the horizon like a golden coin slipping into a piggy bank.”

- Focus on Setting: Pay attention to the setting of your story or narrative. Describe the environment, atmosphere, and surroundings in detail. Take the reader on a journey by clearly depicting the location. Let your words bring the setting to life, whether it’s a lush forest, a bustling city street, or a mystical castle.

- Practice Observation: Practice keen observation skills in your daily life. Take note of the world around you—the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures. Observe people, places, and objects with a writer’s eye. By developing a habit of keen observation, you’ll have a rich bank of sensory details to draw from when you write.

Bonus Tip: Revise and Edit: Good descriptive writing often comes through revision and editing. After writing a draft, go back and read your work critically. Look for opportunities to add more descriptive elements, eliminate unnecessary adjectives or cliches, and refine your language to make it more engaging.

By applying these strategies and continually honing your descriptive writing skills, you’ll be able to transport readers to new worlds, evoke emotions, and make your writing more captivating and memorable.

Free Author’s Purpose Anchor Charts & Posters

Author’s Purpose Teaching Activities

The Author’s Purpose Task 1. The Author’s Purpose Anchor Chart

Whether introducing the general idea of the author’s purpose or working on identifying the specifics of a single purpose, a pie author’s purpose anchor chart can be an excellent resource for students when working independently. Compiling the anchor chart collaboratively with the students can be an effective way for them to reconstruct and reinforce their learning.

The Author’s Purpose Task 2. Gather Real-Life Examples

Challenging students to identify and collect real-life examples of the various types of writing as homework can be a great way to get some hands-on practice. Encourage your students to gather various forms of text together indiscriminately. They then sift through them to categorize them appropriately according to their purpose. The students will soon begin to see that all writing has a purpose. You may also like to make a classroom display of the gathered texts to serve as examples.

The Author’s Purpose Task 3. DIY

One of the most effective ways for students to recognize the authorial intent behind a piece of writing is to gain experience producing writing for various purposes. Design writing tasks with this in mind. For example, if you are focused on writing to persuade, you could challenge the students to produce a script for a radio advertisement. If the focus is entertaining, you could ask the students to write a funny story.

The Author’s Purpose Task 4. Classroom Discussion

When teaching author’s purpose, organize the students into small discussion groups of, say, 4 to 5. Provide each group with copies of sample texts written for various purposes. Students should have some time to read through the texts by themselves. They then work to identify the author’s purpose, making notes as they go. Students can discuss their findings as a group.

Remember: the various purposes are not mutually exclusive; sometimes, a text has more than one purpose. It is possible to be both entertaining and informative, for example. It is essential students recognize this fact. A careful selection of texts can ensure the students can discover this for themselves.

Students need to understand that regardless of the text they are engaged with, every piece of writing has some purpose behind it. It’s important that they work towards recognizing the various features of different types of writing that reveal to the reader just what that purpose is.

Initially, the process of learning to identify the different types of writing and their purposes will require conscious focus on the part of the student. Plenty of opportunities should be created to allow this necessary classroom practice.

However, this practice doesn’t have to be exclusively in the form of discrete lessons on the author’s purpose. Simply asking students what they think the author’s purpose is when reading any text in any context can be a great way to get the ‘reps’ in quickly and frequently.