Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.4 Qualitative Research

Learning objectives.

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?

This book is primarily about quantitative research . Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of data from each of a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in psychology, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study many psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008). They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To do this, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

Again, this book is primarily about quantitative research in psychology. The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, or that female college students are not substantially more talkative than male college students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And it is not very good at all at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973). Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this.

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

As with correlational research, data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews . Interviews in qualitative research tend to be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them. The researcher can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that do come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. This was essentially the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide survivors. Small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue are often referred to as focus groups . The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one-on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses.

Another approach to data collection in qualitative research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. The data they collect can include interviews (usually unstructured), their own notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. An example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins (published in Social Psychology Quarterly ) on a college-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008). Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

Data Analysis in Quantitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with recovering alcoholics to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

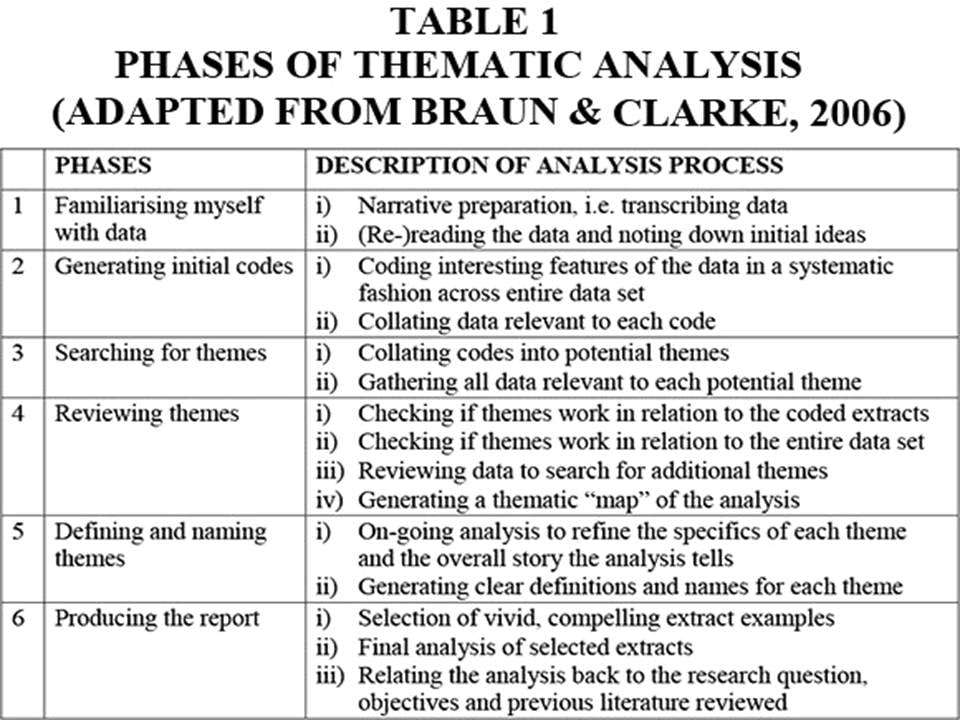

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative —an interpretation—of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009). Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. Table 7.1 “Themes and Repeating Ideas in a Study of Postpartum Depression Among Low-Income Mothers” shows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk.…Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances.

Table 7.1 Themes and Repeating Ideas in a Study of Postpartum Depression Among Low-Income Mothers

| Theme | Repeating ideas |

|---|---|

| Ambivalence | “I wasn’t prepared for this baby,” “I didn’t want to have any more children.” |

| Caregiving overload | “Please stop crying,” “I need a break,” “I can’t do this anymore.” |

| Juggling | “No time to breathe,” “Everyone depends on me,” “Navigating the maze.” |

| Mothering alone | “I really don’t have any help,” “My baby has no father.” |

| Real-life worry | “I don’t have any money,” “Will my baby be OK?” “It’s not safe here.” |

The Quantitative-Qualitative “Debate”

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research in psychology and related fields do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004). (In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches.) One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables for a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation . The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research is an important alternative to quantitative research in psychology. It generally involves asking broader research questions, collecting more detailed data (e.g., interviews), and using nonstatistical analyses.

- Many researchers conceptualize quantitative and qualitative research as complementary and advocate combining them. For example, qualitative research can be used to generate hypotheses and quantitative research to test them.

- Discussion: What are some ways in which a qualitative study of girls who play youth baseball would be likely to differ from a quantitative study on the same topic?

Abrams, L. S., & Curran, L. (2009). “And you’re telling me not to stress?” A grounded theory study of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33 , 351–362.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Lindqvist, P., Johansson, L., & Karlsson, U. (2008). In the aftermath of teenage suicide: A qualitative study of the psychosocial consequences for the surviving family members. BMC Psychiatry, 8 , 26. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/8/26 .

Todd, Z., Nerlich, B., McKeown, S., & Clarke, D. D. (2004) Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice . London, UK: Psychology Press.

Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7: Nonexperimental Research

Qualitative Research

Learning Objectives

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?

This textbook is primarily about quantitative research . Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of data from each of a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this method is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in psychology, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study many psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behaviour than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008) [1] . They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To address this question, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

Again, this textbook is primarily about quantitative research in psychology. The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behaviour. This method is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, or that female undergraduate students are not substantially more talkative than male undergraduate students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behaviour, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behaviour of particular groups in particular situations. And it is not very good at all at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behaviour in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this depth is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973) [2] . Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this detail.

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

As with correlational research, data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews . Interviews in qualitative research can be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them–or structured, where there is a strict script that the interviewer does not deviate from. Most interviews are in between the two and are called semi-structured interviews, where the researcher has a few consistent questions and can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that do come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. The unstructured interview was the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide survivors because the researchers were aware that how much was disclosed about such a sensitive topic should be led by the families not by the researchers. Small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue are often referred to as focus groups . The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one-on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses. However, we know from social psychology that group dynamics are often at play in any group, including focus groups, and it is useful to be aware of those possibilities.

Another approach to data collection in qualitative research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. The data they collect can include interviews (usually unstructured), their own notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. An example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins (published in Social Psychology Quarterly ) on a university-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008) [3] . Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

Data Analysis in Quantitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with recovering alcoholics to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this project sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) [4] . This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this analysis in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative —an interpretation—of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009) [5] . Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. Table 7.1 shows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk.…Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances.

| Theme | Repeating ideas |

|---|---|

| Ambivalence | “I wasn’t prepared for this baby,” “I didn’t want to have any more children.” |

| Care-giving overload | “Please stop crying,” “I need a break,” “I can’t do this anymore.” |

| Juggling | “No time to breathe,” “Everyone depends on me,” “Navigating the maze.” |

| Mothering alone | “I really don’t have any help,” “My baby has no father.” |

| Real-life worry | “I don’t have any money,” “Will my baby be OK?” “It’s not safe here.” |

The Quantitative-Qualitative “Debate”

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research in psychology and related fields do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behaviour and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behaviour and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behaviour.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004) [6] . (In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches.) One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables for a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation . The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Using qualitative research can often help clarify quantitative results in triangulation. Trenor, Yu, Waight, Zerda, and Sha (2008) [7] investigated the experience of female engineering students at university. In the first phase, female engineering students were asked to complete a survey, where they rated a number of their perceptions, including their sense of belonging. Their results were compared by the student ethnicities, and statistically, the various ethnic groups showed no differences in their ratings of sense of belonging. One might look at that result and conclude that ethnicity does not have anything to do with sense of belonging. However, in the second phase, the authors also conducted interviews with the students, and in those interviews, many minority students reported how the diversity of cultures at the university enhanced their sense of belonging. Without the qualitative component, we might have drawn the wrong conclusion about the quantitative results.

This example shows how qualitative and quantitative research work together to help us understand human behaviour. Some researchers have characterized quantitative research as best for identifying behaviours or the phenomenon whereas qualitative research is best for understanding meaning or identifying the mechanism. However, Bryman (2012) [8] argues for breaking down the divide between these arbitrarily different ways of investigating the same questions.

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research is an important alternative to quantitative research in psychology. It generally involves asking broader research questions, collecting more detailed data (e.g., interviews), and using nonstatistical analyses.

- Many researchers conceptualize quantitative and qualitative research as complementary and advocate combining them. For example, qualitative research can be used to generate hypotheses and quantitative research to test them.

- Discussion: What are some ways in which a qualitative study of girls who play youth baseball would be likely to differ from a quantitative study on the same topic? What kind of different data would be generated by interviewing girls one-on-one rather than conducting focus groups?

- Lindqvist, P., Johansson, L., & Karlsson, U. (2008). In the aftermath of teenage suicide: A qualitative study of the psychosocial consequences for the surviving family members. BMC Psychiatry, 8 , 26. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/8/26 ↵

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures . New York, NY: Basic Books. ↵

- Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301. ↵

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, IL: Aldine. ↵

- Abrams, L. S., & Curran, L. (2009). “And you’re telling me not to stress?” A grounded theory study of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33 , 351–362. ↵

- Todd, Z., Nerlich, B., McKeown, S., & Clarke, D. D. (2004) Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice . London, UK: Psychology Press. ↵

- Trenor, J.M., Yu, S.L., Waight, C.L., Zerda. K.S & Sha T.-L. (2008). The relations of ethnicity to female engineering students’ educational experiences and college and career plans in an ethnically diverse learning environment. Journal of Engineering Education, 97 (4), 449-465. ↵

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods , 4th ed. Oxford: OUP. ↵

Research in which data is gathered from a large number of individuals and described using a statistical technique.

A way to collect qualitative data consisting of both general questions and more detailed questions.

Small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue.

Researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying.

Researchers start with the data and develop a theory or interpretation that is “grounded in” the data.

An interpretation of the data in terms of the themes identified through qualitative research.

The combination of quantitative and qualitative research.

Using both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

6.4 Qualitative Research

Learning objectives.

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?

This textbook is primarily about quantitative research, in part because most studies conducted in psychology are quantitative in nature . Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of data from a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this method is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in psychology, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008) [1] . They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To address this question, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

Again, this textbook is primarily about quantitative research in psychology. The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This method is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, and that female undergraduate students are not substantially more talkative than male undergraduate students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And quantitative research is not very good at all at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this depth is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973) [2] . Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this detail.

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

Data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, participant observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews . Interviews in qualitative research can be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them—or structured, where there is a strict script that the interviewer does not deviate from. Most interviews are in between the two and are called semi-structured interviews, where the researcher has a few consistent questions and can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. The unstructured interview was the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide victims because the researchers were aware that how much was disclosed about such a sensitive topic should be led by the families, not by the researchers. Small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue are often referred to as

Focus groups are also used in qualitative research. Focus groups are small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue . The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one-on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses. However, we know from social psychology that group dynamics are often at play in any group, including focus groups, and it is useful to be aware of those possibilities.

Data Analysis in Quantitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with recovering alcoholics to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this project sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) [3] . This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this analysis in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative —an interpretation—of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009) [4] . Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. Table 6.4 shows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk.…Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms, not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances.

| Ambivalence | “I wasn’t prepared for this baby,” “I didn’t want to have any more children.” |

| Caregiving overload | “Please stop crying,” “I need a break,” “I can’t do this anymore.” |

| Juggling | “No time to breathe,” “Everyone depends on me,” “Navigating the maze.” |

| Mothering alone | “I really don’t have any help,” “My baby has no father.” |

| Real-life worry | “I don’t have any money,” “Will my baby be OK?” “It’s not safe here.” |

The Quantitative-Qualitative “Debate”

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research in psychology and related fields do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004) [5] . (In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches.) One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables for a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation . The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Using qualitative research can often help clarify quantitative results in triangulation. Trenor, Yu, Waight, Zerda, and Sha (2008) [6] investigated the experience of female engineering students at a university. In the first phase, female engineering students were asked to complete a survey, where they rated a number of their perceptions, including their sense of belonging. Their results were compared across the student ethnicities, and statistically, the various ethnic groups showed no differences in their ratings of their sense of belonging. One might look at that result and conclude that ethnicity does not have anything to do with one’s sense of belonging. However, in the second phase, the authors also conducted interviews with the students, and in those interviews, many minority students reported how the diversity of cultures at the university enhanced their sense of belonging. Without the qualitative component, we might have drawn the wrong conclusion about the quantitative results.

This example shows how qualitative and quantitative research work together to help us understand human behavior. Some researchers have characterized quantitative research as best for identifying behaviors or the phenomenon whereas qualitative research is best for understanding meaning or identifying the mechanism. However, Bryman (2012) [7] argues for breaking down the divide between these arbitrarily different ways of investigating the same questions.

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research is an important alternative to quantitative research in psychology. It generally involves asking broader research questions, collecting more detailed data (e.g., interviews), and using nonstatistical analyses.

- Many researchers conceptualize quantitative and qualitative research as complementary and advocate combining them. For example, qualitative research can be used to generate hypotheses and quantitative research to test them.

Discussion: What are some ways in which a qualitative study of girls who play youth baseball would be likely to differ from a quantitative study on the same topic? How would the data differ by interviewing girls one-on-one rather than conducting focus groups or surveys?

- Lindqvist, P., Johansson, L., & Karlsson, U. (2008). In the aftermath of teenage suicide: A qualitative study of the psychosocial consequences for the surviving family members. BMC Psychiatry, 8 , 26. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/8/26 ↵

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures . New York, NY: Basic Books. ↵

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, IL: Aldine. ↵

- Abrams, L. S., & Curran, L. (2009). “And you’re telling me not to stress?” A grounded theory study of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33 , 351–362. ↵

- Todd, Z., Nerlich, B., McKeown, S., & Clarke, D. D. (2004) Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice . London, UK: Psychology Press. ↵

- Trenor, J.M., Yu, S.L., Waight, C.L., Zerda. K.S & Sha T.-L. (2008). The relations of ethnicity to female engineering students’ educational experiences and college and career plans in an ethnically diverse learning environment. Journal of Engineering Education, 97 (4), 449-465. ↵

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods , 4th ed. Oxford: OUP. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Qualitative Data Is Used in Psychology

When Numbers Can't Tell the Whole Story

Cecilie_Arcurs/E+/Getty Images

What Is Qualitative Data?

The 3 types of qualitative data, methods of collecting qualitative data, analysis techniques for qualitative data, qualitative vs. quantitative data.

How do researchers analyze answers to open-ended questions? What about the information collected from interviews, video recordings and observations ? This type of data is called qualitative data. Qualitative data means not using numbers to represent information, which would be quantitative data .

Numbers can tell a good story, but certainly not the whole story. That's where qualitative data comes in.

A well-researched article can generate a powerful impact when numbers represent an important fact. For instance, you would feel shocked to find out exactly how much more likely you are to develop mental health issues if you scroll on your phone for more than 3 hours a day. The numbers don’t lie, right?

However, it can be hard to contextualize quantitative facts. That’s where qualitative data can come in, to provide a more human context to help readers make sense of those digits. In psychology studies, qualitative data is used to understand the experiences, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings of study participants. It aims to understand and explain the why and how of a research question, as opposed to the how much or how many.

Real-Life Examples of Qualitative Data

Collecting qualitative data can involve a psychology researcher interviewing subjects with a mental health diagnosis to understand the subjective experience of their symptoms.

Having a focus group discussion with consumers for market research is another example of how qualitative data is used. A facilitator would ask a focus group open-ended questions about their attitudes, perceptions, and opinions about a company’s product or service.

A human resources department conducting personal interviews with employees to understand job satisfaction and workplace culture is also an example of qualitative data.

There are 3 types of qualitative data:

- Binary : Binary data is what computers use to read. Information is coded as ones and zeros. Qualitative data examples include evaluating a statement as ‘true or false’ or responding to a question that only has a ‘yes or no’ answer.

- Ordinal : Ordinal data is information that is categorized based on a range or order. For instance, a question that asks you to rank how much you agree with a statement from ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘disagree’ to ‘strongly disagree’.

- Nominal: Nominal data is when information is named or labeled under two or more categories. The categories do not have an order to them. For instance, gender, marital status and ethnicity are considered nominal data.

There are several important steps to consider before collecting qualitative data. Dr. Stephanie J. Wong , Ph.D., a Licensed Clinical Psychologist and author of Cancel the Filter: Realities of a Psychologist, Podcaster, and Working Mother of Color shared that research proposals need to be submitted to an Institutional Review Board (IRB).

An external organization must evaluate the proposal for potential risks and benefits to participants, and ways you will collect, protect, analyze, and share the data. This applies to both quantitative and qualitative studies. Once your study is approved, there are several ways qualitative data can be collected.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most common ways to collect qualitative data. Personal interviews use a one-on-one approach between an interviewer and a subject to gather how they think and feel about a topic or concept. This can be structured where the interviewer asks predetermined questions. Interviews can also be unstructured and conversational where the interviewer uses open-ended questions but adapts depending on the subject’s responses. The interviews can be recorded and transcribed for qualitative analysis.

- Observations: This qualitative data collection method involves observing participants and gathering information about their behaviors, actions and reactions. Observational data could also be captured via photos, video and audio recordings.

- Document Analysis: Qualitative data can also be collected from old records. Sources can be formal like medical files, financial statements, or incident reports. However, less formal sources that can be analyzed include emails, journal entries, social media posts or comments, and content in online forums.

Dr. Wong explained that qualitative data can be analyzed in various ways, including identifying trends, creating categories of themes, and informing quantitative analysis or studies. Here are some analysis techniques for qualitative data:

- Coding: Coding qualitative data involves categorizing and labeling pieces of information. A system is used to organize the information so that themes, patterns, or concepts can be identified.

- Thematic Analysis: When the data is coded, they are grouped under overarching themes. A theme is a pattern that is seen in the qualitative data. Thematic analysis helps to reveal the research participant's insights and experiences.

- Content Analysis: Content analysis is used when there is a large dataset that includes text, visual, and/or audio information. It uses a systematic approach to categorize the characteristics of the content. It then measures the frequency of these categories to identify themes and trends.

It’s easy to remember the difference between qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data qualifies and quantitative data quantifies what is being investigated.

Qualitative data is descriptive and does not use numbers. Quantitative data is measurable and uses numbers.

Qualitative data is used to understand subjective experiences and perceptions by identifying themes and patterns. Quantitative data is used to determine significant associations based on statistical analysis. Both types of data can be valuable in answering research questions.

“There may be a perception that quantitative research is more scientifically accurate than qualitative research, although both provide value,” explains Dr. Wong.

The Advantages and Potential Drawbacks of Qualitative Data

There are advantages and disadvantages to using qualitative data for your study. Dr. Wong shares that qualitative research is particularly helpful in exploring a topic with a limited amount of research, such as outcomes among specific populations.

“[Qualitative data] can provide rich data that may not be captured by quantitative research and can inform future quantitative studies,” adds Dr. Wong.

However, a drawback is that qualitative research is typically conducted with small sample sizes, which limits the ability to generalize the data to larger groups of people.

Additionally, there is potential for bias since the analysis can be influenced by the researcher’s subjective interpretation.

Lastly, collecting qualitative data typically requires in-depth interviews which can be time-consuming.

Quantitative research is more efficient as it can typically accommodate larger sample sizes and software can be utilized to track and analyze the data.

Therefore, qualitative data is used to understand the nuances of a situation and explore the meaning behind experiences and findings. When deciding on a method of data collection for your study, it’s important to choose one that aligns with your research question and to take into consideration your time, budget, expertise, and available resources. If possible, using both qualitative and quantitative methods can give you a more comprehensive understanding of what you’re researching.

Tenny S, Brannan JM, Brannan GD. Qualitative study . In: StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Bailey J. First steps in qualitative data analysis: transcribing . Family Practice . 2008;25(2):127–131.

Mishra P, Pandey C, Singh U, Gupta A. Scales of measurement and presentation of statistical data . Ann Card Anaesth . 2018;21(4):419–422.

QUAGOL: A guide for qualitative data analysis . International Journal of Nursing Studies . 2012;49(3):360–371.

Winter G. A comparative discussion of the notion of “validity” in qualitative and quantitative research. The Qualitative Report. 2000;4(3):1–14.

By Katharine Chan, MSc, BSc, PMP Katharine is the author of three books (How To Deal With Asian Parents, A Brutally Honest Dating Guide and A Straight Up Guide to a Happy and Healthy Marriage) and the creator of 60 Feelings To Feel: A Journal To Identify Your Emotions. She has over 15 years of experience working in British Columbia's healthcare system.

Qualitative Research in Psychology

Available formats, also available from.

- Table of contents

- Contributor bios

- Book details

Qualitative methods of research contribute valuable information to our understanding and expanding knowledge of psychological phenomena.

This updated edition of Qualitative Research in Psychology builds upon the groundwork laid by its acclaimed predecessor, bringing together a diverse group of scholars to illuminate the value that qualitative methods bring to studying psychological phenomena in depth and in context.

A range of techniques, guiding paradigms, and rich case examples are explored, demonstrating qualitative methodologies as alternative and complementary to quantitative methods, as a means of exploration and theory building, and as a means of developing and evaluating complex behavior-change interventions.

Thoroughly updated chapters reflect advances in this dynamic field. New authors and chapters describe emerging methodologies, qualitative meta-analysis, and how qualitative methods can contribute to a wider psychological approach to research. Pragmatic issues, such as how to choose a method or combination of methods to suit the research question and study design, how to determine the ideal sample size, and how to balance journal space limitations with the need for transparency in describing the study, will be valuable to all readers.

Preface to the Second Edition Paul M. Camic

Part 1. Laying the Foundations: The Pluralistic Approaches of Qualitative Inquiry

- Going Around the Bend and Back: Qualitative Inquiry in Psychological Research Paul M. Camic

- Choosing a Qualitative Method: A Pragmatic, Pluralistic Perspective Chris Barker and Nancy Pistrang

- Narrative in Qualitative Psychology: Approaches and Methodological Consequences Michael Bamberg

- Information Power: Sample Content and Size in Qualitative Studies Kirsti Malterud , Volkert Siersma, and Ann Dorrit Guassora

Part 2. Methodologies for Qualitative Researchers: Helping to Understand the World Around Us

- Participation, Power, and Solidarities Behind Bars: A 25-Year Reflection on Critical Participatory Action Research on College in Prison Michelle Fine, Maria Elena Torre, Kathy Boudin, and Cheryl Wilkins

- Doing Narrative Research Michael Murray

- Discursive Psychology: Capturing the Psychological World as it Unfolds Jonathan Potter

- Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis Jonathan A. Smith and Megumi Fieldsend

- Situational Analysis: Mapping Relationalities in Psychology Rachel Washburn, Adele Clarke, and Carrie Friese

- What Lies Beneath? Eliciting Grounded Theory Through the Analysis of Video-Recorded Verbal and Nonverbal Interactions Colin Griffiths

- Under Observation: Line Drawing as an Investigative Method in Focused Ethnography Andrew Causey

Part 3. Developing and Expanding Qualitative Research

- Into the Ordinary: Lessons Learned From a Mixed-Methods Study in the Homes of People Living With Dementia Emma Harding, Mary Pat Sullivan, Keir X. X. Yong, and Sebastian J. Crutch

- Using Qualitative Research for Intervention Development and Evaluation Lucy Yardley, Katherine Bradbury, and Leanne Morrison

- Qualitative Meta-Analysis: Issues to Consider in Design and Review Kathleen M. Collins and Heidi M. Levitt

Paul M. Camic, PhD , is emeritus professor at Canterbury Christ Church University and honorary professor of health psychology at the Dementia Research Centre, University College London. He has taught qualitative research methods for over 25 years and has published widely using a range of quantitative and qualitative methods. His research interests include the arts, health, and well-being, focusing on older people, those with mental health problems, and those with dementia.

He was founding co-editor of the journal Arts & Health from 2009 to 2018 and coeditor of the Oxford Textbook of Creative Arts, Health, and Wellbeing (published in 2015). He is a Professorial Fellow of the Royal Society for Public Health, and his research on the use of museums and art galleries to address problems of social isolation and loneliness has won awards from Public Health England and the Royal Society for Public Health, as well as a Museums and Heritage Award for Best Educational Initiative.

You may also like

Methodological Issues and Strategies, 5e

How to Mix Methods

Practical Ethics for Psychologists

The Complete Researcher

APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

31 Qualitative Research

Learning objectives.

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?