How to Write a Research Proposal: A Complete Guide

.webp)

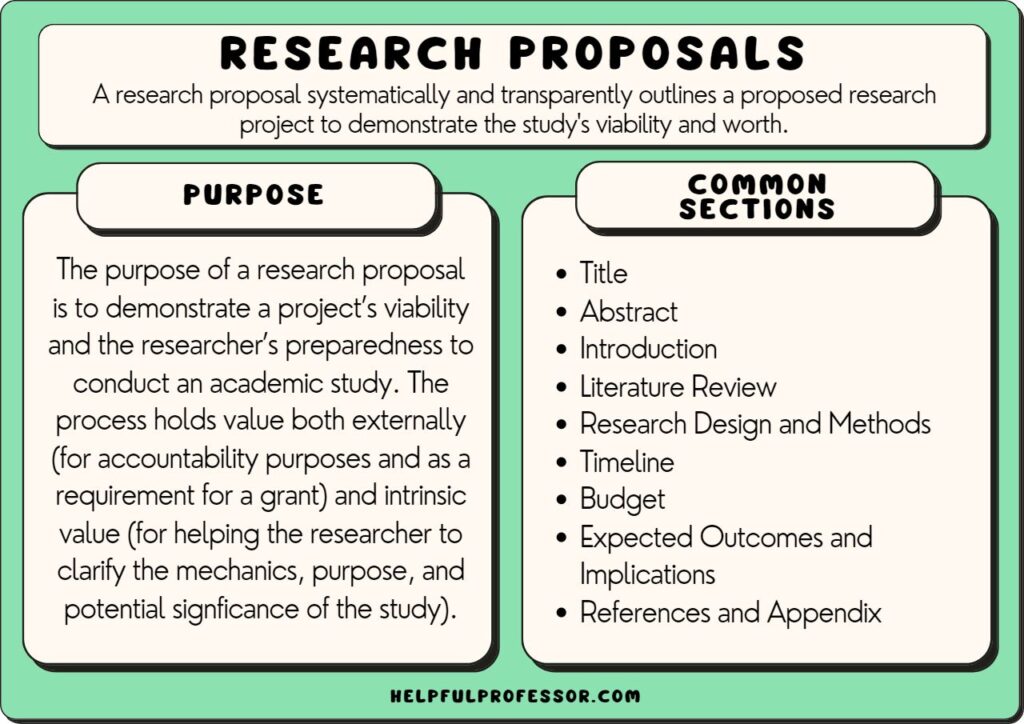

A research proposal is a piece of writing that basically serves as your plan for a research project. It spells out what you’ll study, how you’ll go about it, and why it matters. Think of it as your pitch to show professors or funding bodies that your project is worth their attention and support.

This task is standard for grad students, especially those in research-intensive fields. It’s your chance to showcase your ability to think critically, design a solid study, and articulate why your research could make a difference.

In this article, we'll talk about how to craft a good research proposal, covering everything from the standard format of a research proposal to the specific details you'll need to include.

Feeling overwhelmed by the idea of putting one together? That’s where DoMyEssay comes in handy. Whether you need a little push or more extensive guidance, we’ll help you nail your proposal and move your project forward.

Research Proposal Format

When you're putting together a research proposal, think of it as setting up a roadmap for your project. You want it to be clear and easy to follow so everyone knows what you’re planning to do, how you’re going to do it, and why it matters.

Whether you’re following APA or Chicago style, the key is to keep your formatting clean so that it’s easy for committees or funding bodies to read through and understand.

Here’s a breakdown of each section, with a special focus on formatting a research proposal:

- Title Page : This is your first impression. Make sure it includes the title of your research proposal, your name, and your affiliations. Your title should grab attention and make it clear what your research is about.

- Abstract : This is your elevator pitch. In about 250 words, you need to sum up what you plan to research, how you plan to do it, and what impact you think it will have.

- Introduction : Here’s where you draw them in. Lay out your research question or problem, highlight its importance, and clearly outline what you aim to achieve with your study.

- Literature Review : Show that you’ve done your homework. In this section, demonstrate that you know the field and how your research fits into it. It’s your chance to connect your ideas to what’s already out there and show off a bit about what makes your approach unique or necessary.

- Methodology : Dive into the details of how you’ll get your research done. Explain your methods for gathering data and how you’ll analyze it. This is where you reassure them that your project is doable and you’ve thought through all the steps.

- Timeline : Keep it realistic. Provide an estimated schedule for your research, breaking down the process into manageable stages and assigning a timeline for each phase.

- Budget : If you need funding, lay out a budget that spells out what you need money for. Be clear and precise so there’s no guesswork involved about what you’re asking for.

- References/Bibliography : List out all the works you cited in your proposal. Stick to one citation style to keep things consistent.

Get Your Research Proposal Right

Let our experts guide you through crafting a research proposal that stands out. From idea to submission, we've got you covered.

Research Proposal Structure

When you're writing a research proposal, you're laying out your questions and explaining the path you're planning to take to tackle them. Here’s how to structure your proposal so that it speaks to why your research matters and should get some attention.

Introduction

An introduction is where you grab attention and make everyone see why what you're doing matters. Here, you’ll pose the big question of your research proposal topic and show off the potential of your research right from the get-go:

- Grab attention : Start with something that makes the reader sit up — maybe a surprising fact, a challenging question, or a brief anecdote that highlights the urgency of your topic.

- Set the scene : What’s the broader context of your work? Give a snapshot of the landscape and zoom in on where your research fits. This helps readers see the big picture and the niche you’re filling.

- Lay out your plan : Briefly mention the main goals or questions of your research. If you have a hypothesis, state it clearly here.

- Make it matter : Show why your research needs to happen now. What gaps are you filling? What changes could your findings inspire? Make sure the reader understands the impact and significance of your work.

Literature Review

In your research proposal, the literature review does more than just recap what’s already out there. It's where you get to show off how your research connects with the big ideas and ongoing debates in your field. Here’s how to make this section work hard for you:

- Connect the dots : First up, highlight how your study fits into the current landscape by listing what others have done and positioning your research within it. You want to make it clear that you’re not just following the crowd but actually engaging with and contributing to real conversations.

- Critique what’s out there : Explore what others have done well and where they’ve fallen short. Pointing out the gaps or where others might have missed the mark helps set up why your research is needed and how it offers something different.

- Build on what’s known : Explain how your research will use, challenge, or advance the existing knowledge. Are you closing a key gap? Applying old ideas in new ways? Make it clear how your work is going to add something new or push existing boundaries.

Aims and Objectives

Let's talk about the aims and objectives of your research. This is where you set out what you want to achieve and how you plan to get there:

- Main Goal : Start by stating your primary aim. What big question are you trying to answer, or what hypothesis are you testing? This is your research's main driving force.

- Detailed Objectives : Now, break down your main goal into smaller, actionable objectives. These should be clear and specific steps that will help you reach your overall aim. Think of these as the building blocks of your research, each one designed to contribute to the larger goal.

Research Design and Method

This part of your proposal outlines the practical steps you’ll take to answer your research questions:

- Type of Research : First off, what kind of research are you conducting? Will it be qualitative or quantitative research , or perhaps a mix of both? Clearly define whether you'll be gathering numerical data for statistical analysis or exploring patterns and theories in depth.

- Research Approach : Specify whether your approach is experimental, correlational, or descriptive. Each of these frameworks has its own way of uncovering insights, so choose the one that best fits the questions you’re trying to answer.

- Data Collection : Discuss the specifics of your data. If you’re in the social sciences, for instance, describe who or what you’ll be studying. How will you select your subjects or sources? What criteria will you use, and how will you gather your data? Be clear about the methods you’ll use, whether that’s surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments.

- Tools and Techniques : Detail the tools and techniques you'll use to collect your data. Explain why these tools are the best fit for your research goals.

- Timeline and Budget : Sketch out a timeline for your research activities. How long will each phase take? This helps everyone see that your project is organized and feasible.

- Potential Challenges : What might go wrong? Think about potential obstacles and how you plan to handle them. This shows you’re thinking ahead and preparing for all possibilities.

Ethical Considerations

When you're conducting research, especially involving people, you've got to think about ethics. This is all about ensuring everyone's rights are respected throughout your study. Here’s a quick rundown:

- Participant Rights : You need to protect your participants' rights to privacy, autonomy, and confidentiality. This means they should know what the study involves and agree to participate willingly—this is what we call informed consent.

- Informed Consent : You've got to be clear with participants about what they’re signing up for, what you’ll do with the data, and how you'll keep it confidential. Plus, they need the freedom to drop out any time they want.

- Ethical Approval : Before you even start collecting data, your research plan needs a green light from an ethics committee. This group checks that you’re set up to keep your participants safe and treated fairly.

You need to carefully calculate the costs for every aspect of your project. Make sure to include a bit extra for those just-in-case scenarios like unexpected delays or price hikes. Every dollar should have a clear purpose, so justify each part of your budget to ensure it’s all above board. This approach keeps your project on track financially and avoids any surprises down the line.

The appendices in your research proposal are where you stash all the extra documents that back up your main points. Depending on your project, this could include things like consent forms, questionnaires, measurement tools, or even a simple explanation of your study for participants.

Just like any academic paper, your research proposal needs to include citations for all the sources you’ve referenced. Whether you call it a references list or a bibliography, the idea is the same — crediting the work that has informed your research. Make sure every source you’ve cited is listed properly, keeping everything consistent and easy to follow.

Research Proposal Got You Stuck?

Get expert help with your literature review, ensuring your research is grounded in solid scholarship.

How to Write a Research Proposal?

Whether you're new to this process or looking to refine your skills, here are some practical tips to help you create a strong and compelling proposal.

| Tip | What to Do |

|---|---|

| Stay on Target 🎯 | Stick to the main points and avoid getting sidetracked. A focused proposal is easier to follow and more compelling. |

| Use Visuals 🖼️ | Consider adding charts, graphs, or tables if they help explain your ideas better. Visuals can make complex info clearer. |

| Embrace Feedback 🔄 | Be open to revising your proposal based on feedback. The best proposals often go through several drafts. |

| Prepare Your Pitch 🎤 | If you’re going to present your proposal, practice explaining it clearly and confidently. Being able to pitch it well can make a big difference. |

| Anticipate Questions ❓ | Think about the questions or challenges reviewers might have and prepare clear responses. |

| Think Bigger 🌍 | Consider how your research could impact your field or even broader society. This can make your proposal more persuasive. |

| Use Strong Sources 📚 | Always use credible and up-to-date sources. This strengthens your arguments and builds trust with your readers. |

| Keep It Professional ✏️ | While clarity is key, make sure your tone stays professional throughout your proposal. |

| Highlight What’s New 💡 | Emphasize what’s innovative or unique about your research. This can be a big selling point for your proposal. |

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a simple and handy research proposal example in PDF format to help you get started and keep your work organized:

Writing a research proposal can be straightforward if you break it down into manageable steps:

- Pick a strong research proposal topic that interests you and has enough material to explore.

- Craft an engaging introduction that clearly states your research question and objectives.

- Do a thorough literature review to see how your work fits into the existing research landscape.

- Plan out your research design and method , deciding whether you’ll use qualitative or quantitative research.

- Consider the ethical aspects to ensure your research is conducted responsibly.

- Set up a budget and gather any necessary appendices to support your proposal.

- Make sure all your sources are cited properly to add credibility to your work.

If you need some extra support, DoMyEssay is ready to help with any type of paper, including crafting a strong research proposal.

What Is a Research Proposal?

How long should a research proposal be, how do you start writing a research proposal.

Examples of Research proposals | York St John University. (n.d.). York St John University. https://www.yorksj.ac.uk/study/postgraduate/research-degrees/apply/examples-of-research-proposals/

.webp)

Final Project Proposal

- Post author By Tania Hartanto

- Post date April 10, 2024

- No Comments on Final Project Proposal

We learned from the discussions in our previous class that from the earliest days of civilization, humans have looked to nature for inspiration clothing. Designers today are increasingly turning to nature for inspiration, creating clothing that mimics the qualities of biological materials. In our project, we initially wanted to use mushrooms and fungi as a central theme. Mushrooms offer a fresh perspective on our relationship with the natural world. They serve as metaphors for resilience, adaptation, and interconnectedness. Through the lens of mother nature, we aimed to shed light on the interplay between fashion and the human body while offering a critical examination of prevailing societal practices.

My group-mates, Korrina & Yelena, and I did some background research on mushrooms to gain some inspiration for our concept. Below are some of our notes:

Korrina’s Notes:

- Mushrooms are more closely related to animals than plants ( USA Today, 2023 )

- The mycelial network connects trees together for transfer of nutrients and information

- Tania’s takeaway → can relate to prompt: mushrooms and insects have a symbiotic relationship, just like how humans are dependent on each other to survive

- Others puff & pop using evaporating cooling to create airflow

- Tania’s takeaway → humans hide from their fears until they feel like they are safe

- Lighting can make mushrooms more plentiful (boosts mushroom growth)

- Mushroom mycelium is used to create biodegradable material

- Natural pesticide

- Tania’s takeaway → people don’t feel secure when “picked on” and ends up self destructing, feeling insecure

- Mushrooms can sing

- Trauma (lightning makes us stronger & grow)

- Have connections with people through internet & just in person (rumors spread)

- Connection resilience

Yelena’s Notes:

- Some mushrooms glow at night : Fungi glow because of a natural reaction between enzymes and chemicals called luciferins, including a type called caffeic acid that is found in all plants. Introducing four key fungal genes into the plants’ DNA caused them to glow 10 times more brightly than those engineered using bacteria, The Guardian reports.

- Tania’s takeaway → relate back to symbiotic relationship between humans and nature

- Mushrooms grow very fast, they can symbolize liveliness and strength.

- Mushrooms send out signals to each other. Andrew Adamatzy did a research on mushrooms. He integrated circuits into mushrooms and it worked.

- Books: Humongous Fungus | link

- Canadian Smocking – link

Tania’s Notes

- The mycelial network has more connections than the human brain’s neural pathways but works similarly using electrical impulses and electrolytes

- Hairlike spines

- Clouds of spores “puff” out when they burst open or are hit with falling raindrops

- Oozes indigo-covered latex when the mushroom is cut or broken open

- All mushrooms in the genus Lactarius

- Coated in slimes that attracts flies and insects that help disperse the spores

- Has dramatic lacy skirt-like figure

- Mycelium can be used to make plant-based leather alternatives and vegan, durable, and biodegradable materials

- “ Mycelium can thus be described as the nervous system of the earth, through which all trees, forests, plants, and fungi communicate with each other.”

- Rahul Mishra Spring 2021

- Iris Van Herpen Spring 2021 (inspired by Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds by Merlin Sheldrake)

- Daniel Del Core debut collection, Milan

- Jonathan Anderson Fall 2021

- Johanna Ortiz Fall 2021 (prints inspired by the Fantastic Fungi documentary)

- Pinterest Moodboard for potential inspiration

Kinetic Prototypes Materials and Techniques

Prototype 1: mushroom inflatable.

This prototype consists of a 3D printed mushroom and a silicon inflatable. Our vision for its usage is inspired by our research, which suggests that mushrooms only emerge when environmental conditions are favorable. Therefore, we aim to create a character that remains concealed until it feels comfortable, akin to someone who has experienced trauma and approaches situations with caution. One interesting discovery is that with the sound of the motor, it feels as if the mushroom is breathing.

Prototype 2: Moving Plate

This prototype utilizes a stepper motor, 3D printed chain units, cardboards, and wires. It draws inspiration from Marcela’s demo prototype that has a similar structure with channels on each unit and the example from an Instagram artist. Based on our previous chain unit model from our past project, adjustments were made by adding channels to ensure smoother movement. We are experimenting with how we can make materials move in a life-like way.

Prototype 3: Butterfly

This prototype features a butterfly with flapping wings controlled by an actuator. As the actuator is relatively weak, Korrina devised a mechanism to control the string’s movement, which in turn drives the butterfly wings. Our vision for its usage involves connecting it to a distance sensor, triggering the wings to flap in response to stimuli.

Post-Presentation Feedback from Professor Marcela

After our in-class presentation on our concept and kinetic prototypes, the feedback we received was to focus on h ow mushrooms can inspire potential wearables in the futures. Moreover, we should also look into using the movement of lights to depict one of mushrooms’ interesting features. I guess we were too focused on the metaphorical aspect of our concept rather than what can we take from mushrooms about the technology we have to make this wearable work into our project. Another notion on a mechanism we could explore is some sort of an e xpanding motion to show growth in living organisms or using inflatables to show that something is breathing.

New Sketches by Korrina

After getting feedback in class, Korrina sketched her new idea, but we still wanted to focus on a nature-related concept. The result is, to build an ecosystem that is wearable. What drove us to take on this concept is the issue that the fast fashion industry being one of the least sustainable industries in the world. Through our wearable, we want to encourage people to think more about being environmentally friendly. In a time where it seems as though the world is coming to an irreversible damage, we want to change the way we think about the future by creating ideas on what we can do to be more sustainable through what wear.

Potential mechanism reference:

- Automatic Plant Watering with Arduino | link

- Simple Soil Moisture Sensor Circuit | link – use LED lights to indicate moisture level

- Fast & Easy Rice Paper Decoupage | link

- Diana Scherer manipulates plant roots to grow into intricate, lace-like arrangements | link

Additional Research Reference:

- The easiest fungi to grow: oyster, white button, and Shiitake | link

- Basic requirements for mushroom cultivation | link

- Rootfull | link ;

- MycoWorks | link

- Hemp Fabric | link

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

What’s on the EU research and innovation policy agenda for autumn 2024?

As EU policymakers return from the summer break, we look at key decisions that will affect the R&I community in the months ahead

European Commission, Berlaymont building, Brussels, Belgium. Photo credits: Fred Romero / Flickr

After several crisis-filled years characterised by wars, pandemic and economic challenges, the recent European elections and subsequent summer break offer an opportunity to pause and take stock.

Now, as Europeans filter back to their desks, it’s a good time to look at what the research and innovation community can expect this autumn. The current geopolitical environment has placed R&I topics firmly in the mainstream debate, and that is not likely to change any time soon. Here are some of the stories we expect to be covering in the months ahead.

New commissioner

The first question is, Who will be the next commissioner for Innovation, Research, Culture, Education and Youth? Bulgaria’s Iliana Ivanova has held the post since 2023 after compatriot Mariya Gabriel left to return to national politics , but the country has yet to put forward a commissioner candidate for the upcoming mandate.

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has given member states until 30 August to nominate candidates for the College of Commissioners, after which she will assign portfolios. Bulgaria is one of several countries currently dragging its feet.

Whoever is nominated as the new research commissioner will then be quizzed by MEPs in the Parliament committee for industry, research and energy ITRE, and culture and education committee, with hearings expected to take place in September or October.

Defence funding

For the first time, von der Leyen’s team will include a Commissioner for Defence . During her bid for re-election, she pledged to build a “veritable defence union”, and to present a white paper on the future of European defence.

The white paper, which should be published in the first 100 days of her new mandate, will identify investment needs. Research and innovation may not be at the top of the list, considering the urgent need to provide Ukraine with ammunition, but von der Leyen has promised to reinforce the European Defence Fund which supports R&D projects.

Competitiveness agenda

Speaking to MEPs ahead of her re-election vote, von der Leyen said prosperity and competitiveness would be her top priority. But perhaps the flagship policy of this new strategy, to propose a European competitiveness fund, will have to wait until the EU’s next long-term budget for 2028-2034. The Commission should publish its proposal for this budget by mid-2025.

However, there are several proposals in von der Leyen’s political guidelines that may be put forward before the end of the year and could have an R&D component. For example, she plans to propose a Clean Industrial Deal in her first 100 days to “help create lead markets in everything from clean steel to clean tech” and “speed up planning, tendering, and permitting”.

Further proposals are likely to be influenced by former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi’s highly-anticipated report on EU competitiveness. He was expected to submit his findings to the Commission over the summer, but publication was delayed and should now happen some time this autumn.

FP10 expert group

All eyes will be on the independent group set up to advise the Commission on the interim evaluation of Horizon Europe and its successor, Framework Programme 10. The group’s feedback should be influential in shaping the next framework programme.

The group of 15 experts , led by former Portuguese research minister Manuel Heitor, is meeting monthly between January and October 2024, and is due to deliver its report to the Commission on 16 October.

After taking the advice on board, the Commission should publish its interim evaluation of Horizon Europe early next year, and then present its proposal for FP10 mid-way through 2025.

2025 work programmes

The post-election transition will mean delays to the publication of the Horizon Europe work programmes for 2025 . These are set to be adopted in March or April 2025. We already have some idea of what will feature because the Commission has published its strategic plan for the final years of Horizon Europe, including nine proposed new public-private partnerships.

We are waiting on the work programmes under Pillar II for large collaborative research projects, research infrastructures and the Widening programme for cohesion in research. For other parts of Horizon Europe, such as the European Research Council and the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions, the Commission has extended the current work programmes to cover 2025.

Research lobbies

As well as awaiting the conclusions of the Draghi report, the R&I community will be expecting progress towards implementing Enrico Letta’s recommendations to create a ‘fifth freedom’ of a single market dedicated to the free movement of research, innovation, knowledge and education.

Research lobbies expect the composition of the new Commission to set the tone.

“R&I has never been so central in the political guidelines of the Commission president before the start of a new European Commission,” said Kurt Deketelaere, secretary general of the League of European Research Universities. “Hopefully this will be reflected in the R&I portfolio and its holder.”

Deketelaere is hoping research, innovation and education will remain a standalone portfolio, rather than being integrated into a larger competitiveness, internal market or economy portfolio. That is the case in “a number of member states”, he noted, saying much will depend on who is picked for the role. “Let's hope we get someone with experience and expertise on or in Europe, research, innovation and education.”

Deketelaere also wants to see member states step up. “They can start with stopping the annual circus of opposing the annual Horizon Europe budget as proposed by the European Commission and supported by the European Parliament,” he said. The Council has proposed cutting €400 million from the Horizon budget for 2025.

Muriel Attané, secretary general of the European Association of Research and Technology Organisations, said she is looking forward to working with the new research commissioner in the coming months, including on preparations for FP10 and the next long-term budget, with competitiveness set to have a central role in the discussions.

“Luckily, about 70% of the current FP Horizon Europe budget thanks to its Pillar II is geared towards pan-EU collaborative R&D&I with key industrial partnerships,” she told Science|Business.

“We believe this will be the main asset the new commissioner will have in their pocket, to actually ensure a strong FP10 as well as avoid the FP budget being cannibalised by the announced new competitiveness fund and to avoid that we would be exchanging R&D&I grants for loans.

“We do not need a new Juncker Plan, which did not foster R&D&I,” she added, referencing the 2015 programme that used loan guarantees to secure financing for infrastructure and other projects that were otherwise too risky to invest in. There have been calls to replicate that plan to decarbonise Europe’s industry.

Never miss an update from Science|Business: Newsletter sign-up

Related News

Get the Science|Business newsletters

Sign up for the Funding Newswire

Sign up for the Policy Bulletin

Sign up for The Widening

Funding Newswire subscription

Follow where the public and private R&I money is going and which collaborative opportunities you can pursue.

Subscribe today

Find out more about the Science|Business Network

Why join?

Become a member

- Funding Newswire

- The Widening

- R&D Policy

- Why subscribe?

- Testimonials

- Become a member

- Network news

- Strategic advice

- Sponsorships

- EU Projects

- Enquire today

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

To reform the child protection system in portugal—stakeholders’ positions.

1. Introduction

2. materials and methods, 2.1. procedures, 2.2. measures, 2.3. sample, 2.4. data analysis, 3.1. level of agreement and positions on the proposals to reform the cps, 3.1.1. promotion of quality family-based care and promotion of adoption.

“Everything should be equal, equal in all dimensions”. (Family 1, male)

“In the past, these young people had a vulnerable life, and now have a fragile social network”. (Practitioner 4, female)

“What I think… nobody should be unprotected, should they? The system must ensure protection. They are still very immature...”. (Academic 1, female)

“They should be similar! Those families [special guardians] must be prepared and qualified for their role too”. (Practitioner 3, female)

“Any measure applied to a child should have the same benefits. No matter what kind of measure...”. (Family 2, female)

“Free acceptance from the special guardian, as well as informed consent to accept support”. (Academic 2, female)

“Not to constrain a family... Supporting them is important, but also enabling them to develop a family environment”. (Former beneficiary 2, female)

“It makes all sense to keep family bonds, right?! Siblings have suffered the same situations and processes, and they were in alternative care for the same reasons. Well, yes, I think that siblings should be kept together, in any situation!”. (Former beneficiary 2, female)

“I know a hilarious case. A family adopted a child and was impaired by law to adopt his sister’ cause she was older than 15. So, currently there are two siblings living together in the same family, but having different family names, and having different inheritance rights… in accordance with the current law! They are divorced as siblings...”. (Family 1, male)

“There are other legal institutes [national bodies of law in addition to adoption]. If adoption in those terms was authorised, there would be a conflict between legal institutes [national bodies of law]. And that would be complex… Incapacities, traditions… there must be a reflection about everything in terms of law, shouldn’t there?”. (Academic 4, male)

3.1.2. Development of Child-Friendly Terminology

“It is a question of harmonisation, isn’t it? Focus on children as the subject of rights, with their own autonomy”. (Academic 3, female)

“Labels! For me, are just labels. However, I must say that we are living in Europe, so, Portugal should be aligned with it for comparisons in member-states”. (Family 1, male)

“We are not just a minor… we are… a [particular] child or young person. We need this [child-friendly terminology]! It is more inclusive”. (Former beneficiary 1, female)

“Calling minor to a vulnerable child undermines him/her...”. (Former beneficiary 2, female)

3.1.3. Improvement of the Administration of the CPS: Specialised Courts, Children’s Ombudsman, Coordination and Data Collection

“It makes sense to treat each and every child equally! Even if in a particular part of the country there is only a single one, it will be imperative [to establish a specialised court]”. (Former beneficiary 4, female)

“It is fundamental to provide specialisation in this field, ‘cause it is in these courts that the people who make the most relevant decisions for the life of a child are located”. (Practitioner 4, female)

“Some say that it [the children’s ombudsman] is unconstitutional because it collides with the role of the general ombudsman. For me sincerely, I think that… again the interest of children should prevail [...] the general ombudsman is completely unaware of the child’s needs”. (Academic 1, female)

“[...] or it [the children’s ombudsman] could be a specialised department of the general ombudsman’s institution, that is the one mandated to receive complaints about rights that were violated. I mean, regarding the small size of the country, perhaps it won’t make sense to create an entire organisation. It happens the same in the scope of the courts… The Family Court and other courts are within the main court institution”. (Family 1, male)

“Someone who stands for them [children], that is close to them.— He belongs to me ; I may talk with him [the children’s ombudsman]. He came to my school today and gave me his phone number. Someone who represents children and gives them voice! Yes, it makes sense to me”. (Practitioner 1, female)

“Adding one more [entity]…, it will not solve the problem in the short term… It will complicate it even more…”. (Family 2, female)

“In my opinion, it makes sense! ‘This disorganization’ is… Sadly, leads to a child suffering twice, when he/she was abused by his/her family, and then by the system, because he/she is required to go through so many services… Today he/she is with the social worker at the Social Security, tomorrow he/she is at a court… The easier, the better. Entities must have complete information about a child and know each other’s roles and to be coordinated”. (Former beneficiary 1, female)

“We are talking about a structure similar to a ministry of childhood or a ministry of childhood and youth, no matter its name. What matters is its aims and to conduct a search about methodologies implemented in other latitudes”. (Practitioner 2, male)

“It is horrible! You need to be a qualified detective to find [where the] information [is]”. (Academic 2, female)

“Cross-sectional information to compare it… To identify children who were supported by the Child Protection System and later became involved in the justice system, in the juvenile or even in the criminal. And as well as reporting those former beneficiaries who became homeless”. (Academic 1, female)

“The question is… how will they present the data collected? Will they work to make it more appealing rather than real?”. (Family 4, female)

4. Discussion

5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Alfaiate, Ana Rita, and Geraldo Ribeiro. 2013. Reflexões a propósito do apadrinhamento civil. Revista do Centro de Estudos Judiciários 1: 117–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barros, Diana, Paula Casaleiro, Paula Fernando, and João Paulo Dias. 2023. Mapping Child Protection Systems in the EU (27). Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/pt_-_report_-_mapping_child_protection_systems_-_2023.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Blaikie, Norman. 2010. Designing Social Research . Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bruning, Mariëlle, and Jaap Doek. 2021. Characteristics of an effective child protection system in the European and international contexts. International Journal on Child Maltreatment: Research, Policy and Practice 4: 231–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cantwell, Nigel, Jennifer Davidson, Susan Elsley, Ian Milligan, and Neil Quinn. 2012. Moving Forward: Implementing the ‘Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children . Glasgow: Centre for Excellence for Looked After Children in Scotland. Available online: https://www.alternativecareguidelines.org/Portals/46/Moving-forward/Moving-Forward-implementing-the-guidelines-for-web1.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Castro, José, Jorge Ferreira, and Luís Capucha. 2023. Uma análise histórica do sistema de proteção de crianças português. Que lições para o futuro? Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 102: 59–78. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Council of Europe. 2022. Council of Europe Strategy for the Rights of the Child (2022–2027). Available online: https://rm.coe.int/council-of-europe-strategy-for-the-rights-of-the-child-2022-2027-child/1680a5ef27 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Council of Ministers’ Resolution no. 112/2020 of 18 December [Resolução do Conselho de Ministros no. 112/2020 de 18 de Dezembro]. 2020. Diário da República . No. 245, Série I. pp. 2–22. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/1s/2020/12/24500/0000200022.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Council Recommendation. 2021. Establishing a European Child Guarantee. European Union, Council of the European Union. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2021/1004/oj (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Davidson, Jennifer, Ian Milligan, Neil Quinn, Nigel Cantwell, and Susan Elsley. 2016. Developing family-based care: Complexities in implementing the UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. European Journal of Social Work 20: 754–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- de Souza, Joanna, Karen Gillett, Yakubu Salifu, and Catherine Walshe. 2024. Changes in Participant Interactions. Using Focus Group Analysis Methodology to Explore the Impact on Participant Interactions of Face-to-Face Versus Online Video Data Collection Methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 23: 1–14. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Decree-Law no. 121/2010 of 27 October [Decreto-Lei n.º 121/2010, de 27 de Outubro]. 2010. Diário da República . 209, Série I. pp. 4892–94. Available online: https://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=1287&tabela=leis&so_miolo= (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Decree-Law no. 139/2017 of 10 November [Decreto-Lei n.º 139/2017, de 10 de Novembro]. 2017. Diário da República . 217, Série I. pp. 6002–8. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/139-2017-114177786 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- DGPJ—Direção Geral de Política de Justiça. 2024. Processos de Apadrinhamento Civil Findos nos Tribunais Judiciais de 1.ª Instância, por Modalidade de Termo, nos Anos de 2011 a 2023. Available online: https://estatisticas.justica.gov.pt/sites/siej/pt-pt/Paginas/Processos-tutelares-civeis-findos-nos-tribunais-judiciais-de-1-instancia.aspx (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Dias, Cristina. 2012. Algumas notas em torno do regime jurídico do apadrinhamento civil. In Estudos em Homenagem ao Professor Doutor Heinrich Ewald Hörster . Edited by Luís Gonçalves. Coimbra: Almedina, pp. 161–95. [ Google Scholar ]

- Diogo, Elisete, Bárbara Mourão Sacur, and Paulo Guerra. 2022. Caminhos para uma reforma do Sistema de Promoção e Proteção das Crianças e Jovens—Recomendações. Temas Sociais 3: 31–51. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- European Commission. 2021. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child (COM/2021/142 Final). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0142 (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- European Commission. 2024. Commission Recommendation of 23rd April on Developing and Strengthening Child Protection Systems in the best Interests of the Child. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/36591cfb-1b0a-4130-985e-332fd87d40c1_en?filename=C_2024_2680_1_EN_ACT_part1_v8.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- Ferreira, Elisabete. 2019. O apadrinhamento civil como alternativa ao acolhimento permanente de crianças e jovens. Configurações 23: 159–76. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Flekkoy, Målfrid. 1990. Working for the Rights of Children. Innocenti Essay . 1. Available online: https://shre.ink/19wt (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Flick, Uwe. 2005. Métodos Qualitativos na Investigação Científica . Lisbon: Monitor. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flick, Uwe. 2013. Introdução à Metodologia de Pesquisa . Porto Alegre: Penso. [ Google Scholar ]

- FRA. 2024. Mapping Child Protection Systems—Data File (Data from 2014 and 2023). Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2024/mapping-child-protection-systems-eu-update-2023#read-online (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Furey, Eamonn, and John Canavan. 2019. A Review on the Availability and Comparability of Statistics on Child Protection Welfare, Including Children in Care Collated by Tusia: Child and Family Agency with Statistics Published in Other Jurisdictions . Galway: UNESCO Child and Family Research Centre, NUI Galway. Available online: https://www.tusla.ie/uploads/content/COMPWELFINALREPORTMARCH29_-_Final.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Gilbert, Neil, Nigel Parton, and Marit Skivenes. 2011. Child Protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations . Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gottschalk, Francesca, and Hannah Borhan. 2023. Child Participation in Decision Making: Implications for Education and Beyond . OECD Education Working Papers. Paris: OECD Publishing. 301p. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Guerra, Paulo. 2021. Lei de Proteção de Crianças e Jovens em Perigo. Anotada , 5th ed. Coimbra: Almedina. [ Google Scholar ]

- Instituto da Segurança Social, Instituto Público. 2023. CASA, 2022—Relatório de Caracterização Anual da Situação de Acolhimento das Crianças e Jovens. Available online: https://www.seg-social.pt/documents/10152/13200/Relat%C3%B3rio+CASA+2022/c1d7359c-0c75-4aae-b916-3980070d4471 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Law no. 103/2009 of 11 September [Lei n. º 103/2009, de 11 de Setembro]. 2009. Diário da República . 177, Série I. pp. 6210–16. Available online: https://dre.pt/dre/legislacao-consolidada/lei/2009-34513875 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Law no. 147/99 of 1 September and Its Amendments [Lei n. º 147/99 de 1 de Setembro]. 1999. Diário da República . 204, Série I-A. pp. 6115–32. Available online: http://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=545&tabela=leis (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Law no. 23/2023 of 25 May [Lei n. º 23/2023, de 25 de Maio]. 2023. Diário da República . 101, Série I. pp. 21–22. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/lei/23-2023-213498832 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Law no. 46/2023 of 17 August [Lei no.46/2023, de 17 de Agosto]. 2023. Diário da República . 159, Série I. pp. 12–13. Available online: https://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=3683&tabela=leis&ficha=1&pagina=1&so_miolo= (accessed on 16 May 2023).

- Maguire, Moira, and Brid Delahunt. 2017. Doing a Thematic Analysis: A Practical, Step-by-Step Guide for Learning and Teaching Scholars. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education 8: 3351–514. [ Google Scholar ]

- Melton, Gary. 1991. Lessons from Norway: The children’s ombudsman as a voice for children. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 23: 197. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moreira, João Manuel. 2004. Questionários: Teoria e prática . Coimbra: Almedina. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parton, Nigel. 2019. Addressing the Relatively Autonomous Relationship Between Child Maltreatment and Child Protection Policies and Practices. International Journal on Child Maltreatment: Research, Policy and Practice 3: 19–34. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Roesch-Marsh, Autumn, Andrew Gillies, and Dominique Green. 2017. Nurturing the virtuous circle: Looked after Children’s participation in reviews, a cyclical and relational process. Child & Family Social Work 22: 904–13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rolock, Nancy, Kerrie Ocasio, Kevin White, Young Cho, Rowena Fong, Laura Marra, and Monica Faulkner. 2020. Identifying Families Who May Be Struggling after Adoption or Guardianship. Journal of Public Child Welfare 15: 78–104. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sacur, Bárbara Mourão, and Elisete Diogo. 2021. The EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child and the European Child Guarantee—Evidence-based recommendations for alternative care. Children 8: 1181. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Sim, Julius, and Jackie Waterfield. 2019. Focus group methodology: Some ethical challenges. Quality & Quantity 53: 3003–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Simmonds, John, and Judith Harwin. 2020. Making Special Guardianship Work for Children and Their Guardians . Briefing Paper. London: Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. [ Google Scholar ]

- Skauge, Berit, Anita Skårstad Storhaug, and Edgar Marthinsen. 2021. The What, Why and How of Child Participation—A Review of the Conceptualization of “Child Participation” in Child Welfare. Social Sciences 10: 54. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Smales, Madelaine, Melissa Savaglio, Heather Morris, Lauren Bruce, Helen Skouteris, and Rachel Green. 2020. “Surviving not thriving”: Experiences of health among young people with a lived experience in out-of-home care. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25: 809–23. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office and Eurochild. 2021. Better Data for Better Child Protection Systems in Europe: Mapping How Data on Children in Alternative Care Are Collected, Analysed and Published across 28 European Countries. Technical Report of Datacare Project. Available online: https://eurochild.org/uploads/2022/02/UNICEF-DataCare-Technical-Report-Final-1.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- United Nations Children’s Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Save the Children and World Vision. 2013. A Better Way to Protect All Children: The Theory and Practice of Child Protection Systems, Conference Report. Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/c956_cps_interior_5_130620web_0.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- United Nations. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- United Nations. 2019. Concluding Observations on the Combined Fifth and Sixth Periodic Report of Portugal. Available online: https://shre.ink/195O (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Woodman, Elise, Steven Roche, and Morag McArthur. 2023. Children’s participation in child protection—How do practitioners understand children’s participation in practice? Children & Family Social Work 28: 125–35. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

| Proposals to Reform the CPS |

|---|

| Family-based care and adoption |

| Terminology |

| Administration of the CPS |

| Sample Characteristics | Online Survey Sample N = 292 | Focus Group Sample N = 18 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years); mean (SD; range) | 47.23 (10.95; 20–73) | 46.11 (12.53; 20–69) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 246 | 14 |

| Male | 46 | 4 |

| Years of contact with child protection system; mean (SD; range) | 14.02 (9.23; 1–47) | 14.89 (10.03; 1–39) |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Diogo, E.; Silva, J.V.; Sacur, B.M. To Reform the Child Protection System in Portugal—Stakeholders’ Positions. Soc. Sci. 2024 , 13 , 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090443

Diogo E, Silva JV, Sacur BM. To Reform the Child Protection System in Portugal—Stakeholders’ Positions. Social Sciences . 2024; 13(9):443. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090443

Diogo, Elisete, Joana Véstia Silva, and Bárbara Mourão Sacur. 2024. "To Reform the Child Protection System in Portugal—Stakeholders’ Positions" Social Sciences 13, no. 9: 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090443

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- 2018/03/18/Making-a-presentation-from-your-research-proposal

Making a presentation from your research proposal

In theory, it couldn’t be easier to take your written research proposal and turn it into a presentation. Many people find presenting ideas easier than writing about them as writing is inherently difficult. On the other hand, standing up in front of a room of strangers, or worse those you know, is also a bewildering task. Essentially, you have a story to tell, but does not mean you are story telling. It means that your presentation will require you to talk continuously for your alloted period of time, and that the sentences must follow on from each other in a logical narative; i.e. a story.

So where do you start?

Here are some simple rules to help guide you to build your presentation:

- One slide per minute: However many minutes you have to present, that’s your total number of slides. Don’t be tempted to slip in more.

- Keep the format clear: There are lots of templates available to use, but you’d do best to keep your presentation very clean and simple.

- Be careful with animations: You can build your slide with animations (by adding images, words or graphics). But do not flash, bounce, rotate or roll. No animated little clipart characters. No goofy cartoons – they’ll be too small for the audience to read. No sounds (unless you are talking about sounds). Your audience has seen it all before, and that’s not what they’ve come for. They have come to hear about your research proposal.

- Don’t be a comedian: Everyone appreciates that occasional light-hearted comment, but it is not stand-up. If you feel that you must make a joke, make only one and be ready to push on when no-one reacts. Sarcasm simply won’t be understood by the majority of your audience, so don’t bother: unless you’re a witless Brit who can’t string three or more sentences together without.

Keep to your written proposal formula

- You need a title slide (with your name, that of your advisor & institution)

- that put your study into the big picture

- explain variables in the context of existing literature

- explain the relevance of your study organisms

- give the context of your own study

- Your aims & hypotheses

- Images of apparatus or diagrams of how apparatus are supposed to work. If you can’t find anything, draw it simply yourself.

- Your methods can be abbreviated. For example, you can tell the audience that you will measure your organism, but you don’t need to provide a slide of the callipers or balance (unless these are the major measurements you need).

- Analyses are important. Make sure that you understand how they work, otherwise you won’t be able to present them to others. Importantly, explain where each of the variables that you introduced, and explained how to measure, fit into the analyses. There shouldn’t be anything new or unexpected that pops up here.

- I like to see what the results might look like, even if you have to draw graphs with your own lines on it. Use arrows to show predictions under different assumptions.

Slide layout

- Your aim is to have your audience listen to you, and only look at the slides when you indicate their relevance.

- You’d be better off having a presentation without words, then your audience will listen instead of trying to read. As long as they are reading, they aren't listening. Really try to limit the words you have on any single slide (<30). Don’t have full sentences, but write just enough to remind you of what to say and so that your audience can follow when you are moving from point to point.

- Use bullet pointed lists if you have several points to make (Font 28 pt)

- If you only have words on a slide, then add a picture that will help illustrate your point. This is especially useful to illustrate your organism. At the same time, don’t have anything on a slide that has no meaning or relevance. Make sure that any illustration is large enough for your audience to see and understand what it is that you are trying to show.

- Everything on your slide must be mentioned in your presentation, so remove anything that becomes irrelevant to your story when you practice.

- Tables: you are unlikely to have large complex tables in a presentation, but presenting raw data or small words in a table is a way to lose your audience. Make your point in another way.

- Use citations (these can go in smaller font 20 pt). I like to cut out the title & authors of the paper from the pdf and show it on the slide.

- If you can, have some banner that states where you are in your presentation (e.g. Methods, or 5 of 13). It helps members of the audience who might have been daydreaming.

Practice, practice, practice

- It can’t be said enough that you must practice your presentation. Do it in front of a mirror in your bathroom. In front of your friends. It's the best way of making sure you'll do a good job.

- If you can't remember what you need to say, write flash cards with prompts. Include the text on your slide and expand. When you learn what’s on the cards, relate it to what’s on the slide so that you can look at the slides and get enough hints on what to say. Don’t bring flashcards with you to your talk. Instead be confident enough that you know them front to back and back to front.

- Practice with a pointer and slide advancer (or whatever you will use in the presentation). You should be pointing out to your audience what you have on your slides; use the pointer to do this.

- Avoid taking anything with you that you might fiddle with.

Maybe I've got it all wrong?

There are some things that I still need to learn about presentations. Have a look at the following video and see what you think. There are some really good points made here, and I think I should update my example slides to reflect these ideas. I especially like the use of contrast to focus attention.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

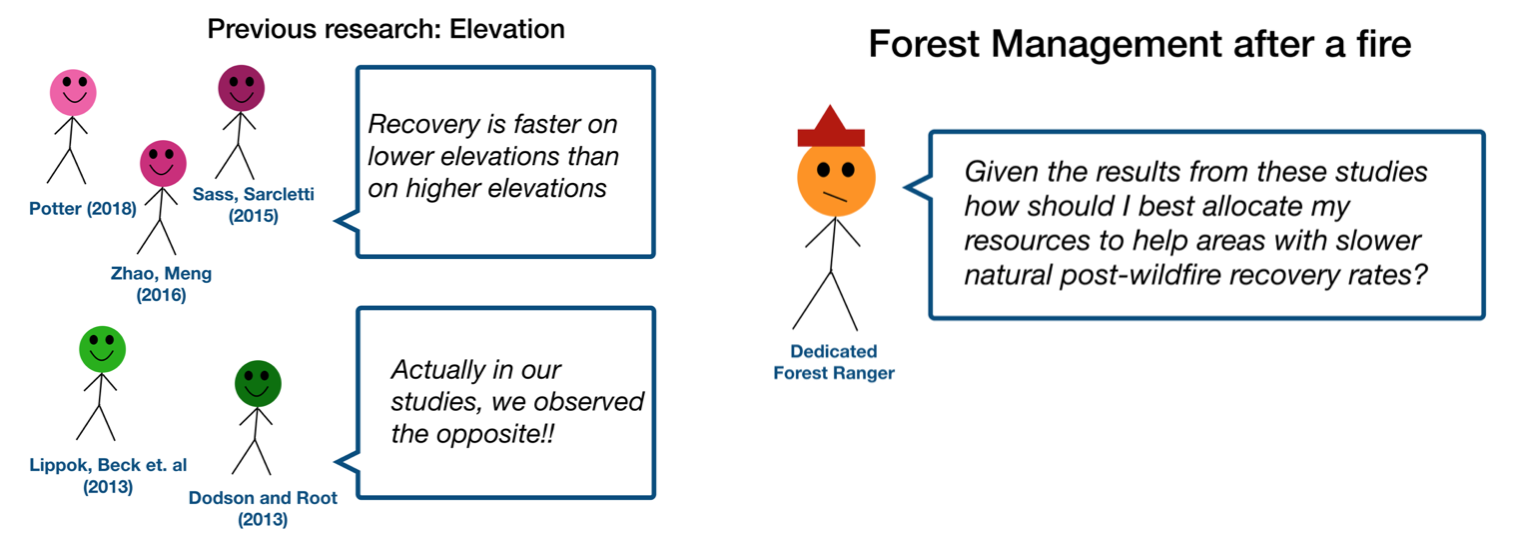

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- Information for participants

How to present a research proposal

Presenting a research proposal is part of most Masters and Doctoral programmes and is also a considerably important skill for professional life. Developing an ability to clearly articulate complex ideas and to meaningfully engage with an audience, ensure your ideas are heard, and ensure that the feedback you receive is more constructive that simple requests for clarification.

Let’s consider the main objectives of the presentation:

- To convince your peers, supervisors, and perhaps members of relevant quality assurance committees (e.g., proposals, ethics), that you have a viable and worth-while project

- To receive constructive feedback that can shape the project

- Potentially, identify collaborative opportunities

To achieve any of these outcomes you must first be successful in conveying your research idea, which is something that must be practiced and rehearsed.

The suggestions presented here have been collated after many years of teaching and observing student presentations, as well as reflective learning from my own experiences in delivering pitches and presentations.

- Ensure that you will be able to deliver your presentation on the day. Have a plan B, and maybe a plan C. Use a flash drive, keep your files on Dropbox, or email yourself the presentation the day before.

- If you need to run media in your presentation, then be sure you have stored the associated media files in the same folder as the .pptx file, and remember that you will need to copy the whole folder onto a flash drive to run it.

- Learn how to put powerpoint into full screen mode before you go to present, and learn how to use the keyboard or mouse to navigate back and forwards (i.e. you can simply use arrow keys, or space and back space).

- Plan your talk. The amount of planning necessary for a talk depends on the environment, how familiar you are with the content and how comfortable you are talking in public. The downside to word-for-word talking is that most people go into reading-mode and sound unnatural. Furthermore, getting just one word wrong can throw the rhythm for the whole talk off. Instead, I recommend simply developing a good idea about the flow of key arguments, and know what the next slide is about and how to make that transition. This approach will give you the freedom to use whatever words come to you at the time (which will sound much more genuine) and will allow for any little interruptions or diversions that may occur. Of course, you should practice your talk with a stopwatch handy to familiarise yourself with the directions you will take. The best parts to remember are the transitions between slides or sections.

Designing the presentation

- Plan to talk and use the slides as a supplement only. Remember, your audience won’t read the words on the slides and listen to you at the same time. One way or another, the audience must be allowed to absorb all information provided, and since it’s a presentation (and not an email), they will want to hear you present. This means keeping the slides clean and brief.

- Keep the word-count to an essential minimum on the slides. Avoid sentences.

- Use the slides to provide structure to your presentation and help the audience follow you with heading and key points.

- Try use slides for images, graphs, diagrams, and tables only

- Keep the number of slides low. Any more than one slide per minute of presentation and you may be overdoing it. A good tip would be to have a slide with a consort diagram and then talk your way the various stages of your design, rather than having one slide per stage.

- Don’t use a font size less that 20pt.

- Have no more than two images/illustrations per slide

Readability

- Use high contrast colours only. Black text on a white background is best and will work well in rooms and projectors that are less than ideal.

- Use a good font. Times New Roman and Arial are fonts that are very easy to read and are professional.

- Keep your sentences short. Remember it is you that will be doing the talking, so you do not need full sentences written on slides.

- Use either bold, underline or italics, not a combination of these. DONT USE FULL CAPS. Limit exclamation marks, never more that one!!!

- Use bullets for points, numbers for a list (especially if ordinal,) and letter for options.

Delivering the Presentation

- Stand and face your audience, but be sure that you are not obstructing anyone’s view.

- Engage the audience and read off their expressions. Looking at the screen is acceptable as a reminder of where you are in your presentation, and also to provide guidance when explaining illustrations and graphs. Otherwise, you should be focusing on connecting with the audience, and not the screen.