Mental Health Case Study: Understanding Depression through a Real-life Example

Through the lens of a gripping real-life case study, we delve into the depths of depression, unraveling its complexities and shedding light on the power of understanding mental health through individual experiences. Mental health case studies serve as invaluable tools in our quest to comprehend the intricate workings of the human mind and the various conditions that can affect it. By examining real-life examples, we gain profound insights into the lived experiences of individuals grappling with mental health challenges, allowing us to develop more effective strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and support.

The Importance of Case Studies in Understanding Mental Health

Case studies play a crucial role in the field of mental health research and practice. They provide a unique window into the personal narratives of individuals facing mental health challenges, offering a level of detail and context that is often missing from broader statistical analyses. By focusing on specific cases, researchers and clinicians can gain a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors that contribute to mental health conditions.

One of the primary benefits of using real-life examples in mental health case studies is the ability to humanize the experience of mental illness. These narratives help to break down stigma and misconceptions surrounding mental health conditions, fostering empathy and understanding among both professionals and the general public. By sharing the stories of individuals who have faced and overcome mental health challenges, case studies can also provide hope and inspiration to those currently struggling with similar issues.

Depression, in particular, is a common mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide. Disability Function Report Example Answers for Depression and Bipolar: A Comprehensive Guide offers valuable insights into how depression can impact daily functioning and the importance of accurate reporting in disability assessments. By examining depression through the lens of a case study, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of its manifestations, challenges, and potential treatment approaches.

Understanding Depression

Before delving into our case study, it’s essential to establish a clear understanding of depression and its impact on individuals and society. Depression is a complex mental health disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and loss of interest in activities. It can affect a person’s thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and overall well-being.

Some common symptoms of depression include:

– Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood – Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism – Irritability – Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities – Decreased energy or fatigue – Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions – Sleep disturbances (insomnia or oversleeping) – Appetite and weight changes – Physical aches or pains without clear physical causes – Thoughts of death or suicide

The prevalence of depression worldwide is staggering. According to the World Health Organization, more than 264 million people of all ages suffer from depression globally. It is a leading cause of disability and contributes significantly to the overall global burden of disease. The impact of depression extends far beyond the individual, affecting families, communities, and economies.

Depression can have profound consequences on an individual’s quality of life, relationships, and ability to function in daily activities. It can lead to decreased productivity at work or school, strained personal relationships, and increased risk of other health problems. The economic burden of depression is also substantial, with costs associated with healthcare, lost productivity, and disability.

The Significance of Case Studies in Mental Health Research

Case studies serve as powerful tools in mental health research, offering unique insights that complement broader statistical analyses and controlled experiments. They allow researchers and clinicians to explore the nuances of individual experiences, providing a rich tapestry of information that can inform our understanding of mental health conditions and guide the development of more effective treatment strategies.

One of the key advantages of case studies is their ability to capture the complexity of mental health conditions. Unlike standardized questionnaires or diagnostic criteria, case studies can reveal the intricate interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors that contribute to an individual’s mental health. This holistic approach is particularly valuable in understanding conditions like depression, which often have multifaceted causes and manifestations.

Case studies also play a crucial role in the development of treatment strategies. By examining the detailed accounts of individuals who have undergone various interventions, researchers and clinicians can identify patterns of effectiveness and potential barriers to treatment. This information can then be used to refine existing approaches or develop new, more targeted interventions.

Moreover, case studies contribute to the advancement of mental health research by generating hypotheses and identifying areas for further investigation. They can highlight unique aspects of a condition or treatment that may not be apparent in larger-scale studies, prompting researchers to explore new avenues of inquiry.

Examining a Real-life Case Study of Depression

To illustrate the power of case studies in understanding depression, let’s examine the story of Sarah, a 32-year-old marketing executive who sought help for persistent feelings of sadness and loss of interest in her once-beloved activities. Sarah’s case provides a compelling example of how depression can manifest in high-functioning individuals and the challenges they face in seeking and receiving appropriate treatment.

Background: Sarah had always been an ambitious and driven individual, excelling in her career and maintaining an active social life. However, over the past year, she began to experience a gradual decline in her mood and energy levels. Initially, she attributed these changes to work stress and the demands of her busy lifestyle. As time went on, Sarah found herself increasingly isolated, withdrawing from friends and family, and struggling to find joy in activities she once loved.

Presentation of Symptoms: When Sarah finally sought help from a mental health professional, she presented with the following symptoms:

– Persistent feelings of sadness and emptiness – Loss of interest in hobbies and social activities – Difficulty concentrating at work – Insomnia and daytime fatigue – Unexplained physical aches and pains – Feelings of worthlessness and guilt – Occasional thoughts of death, though no active suicidal ideation

Initial Diagnosis: Based on Sarah’s symptoms and their duration, her therapist diagnosed her with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). This diagnosis was supported by the presence of multiple core symptoms of depression that had persisted for more than two weeks and significantly impacted her daily functioning.

The Treatment Journey

Sarah’s case study provides an opportunity to explore the various treatment options available for depression and examine their effectiveness in a real-world context. Supporting a Caseworker’s Client Who Struggles with Depression offers valuable insights into the role of support systems in managing depression, which can complement professional treatment approaches.

Overview of Treatment Options: There are several evidence-based treatments available for depression, including:

1. Psychotherapy: Various forms of talk therapy, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT), can help individuals identify and change negative thought patterns and behaviors associated with depression.

2. Medication: Antidepressants, such as Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), can help regulate brain chemistry and alleviate symptoms of depression.

3. Combination Therapy: Many individuals benefit from a combination of psychotherapy and medication.

4. Lifestyle Changes: Exercise, improved sleep habits, and stress reduction techniques can complement other treatments.

5. Alternative Therapies: Some individuals find relief through approaches like mindfulness meditation, acupuncture, or light therapy.

Treatment Plan for Sarah: After careful consideration of Sarah’s symptoms, preferences, and lifestyle, her treatment team developed a comprehensive plan that included:

1. Weekly Cognitive Behavioral Therapy sessions to address negative thought patterns and develop coping strategies.

2. Prescription of an SSRI antidepressant to help alleviate her symptoms.

3. Recommendations for lifestyle changes, including regular exercise and improved sleep hygiene.

4. Gradual reintroduction of social activities and hobbies to combat isolation.

Effectiveness of the Treatment Approach: Sarah’s response to treatment was monitored closely over the following months. Initially, she experienced some side effects from the medication, including mild nausea and headaches, which subsided after a few weeks. As she continued with therapy and medication, Sarah began to notice gradual improvements in her mood and energy levels.

The CBT sessions proved particularly helpful in challenging Sarah’s negative self-perceptions and developing more balanced thinking patterns. She learned to recognize and reframe her automatic negative thoughts, which had been contributing to her feelings of worthlessness and guilt.

The combination of medication and therapy allowed Sarah to regain the motivation to engage in physical exercise and social activities. As she reintegrated these positive habits into her life, she experienced further improvements in her mood and overall well-being.

The Outcome and Lessons Learned

Sarah’s journey through depression and treatment offers valuable insights into the complexities of mental health and the effectiveness of various interventions. Understanding the Link Between Sapolsky and Depression provides additional context on the biological underpinnings of depression, which can complement the insights gained from individual case studies.

Progress and Challenges: Over the course of six months, Sarah made significant progress in managing her depression. Her mood stabilized, and she regained interest in her work and social life. She reported feeling more energetic and optimistic about the future. However, her journey was not without challenges. Sarah experienced setbacks during particularly stressful periods at work and struggled with the stigma associated with taking medication for mental health.

One of the most significant challenges Sarah faced was learning to prioritize her mental health in a high-pressure work environment. She had to develop new boundaries and communication strategies to manage her workload effectively without compromising her well-being.

Key Lessons Learned: Sarah’s case study highlights several important lessons about depression and its treatment:

1. Early intervention is crucial: Sarah’s initial reluctance to seek help led to a prolongation of her symptoms. Recognizing and addressing mental health concerns early can prevent the condition from worsening.

2. Treatment is often multifaceted: The combination of medication, therapy, and lifestyle changes proved most effective for Sarah, underscoring the importance of a comprehensive treatment approach.

3. Recovery is a process: Sarah’s improvement was gradual and non-linear, with setbacks along the way. This emphasizes the need for patience and persistence in mental health treatment.

4. Social support is vital: Reintegrating social activities and maintaining connections with friends and family played a crucial role in Sarah’s recovery.

5. Workplace mental health awareness is essential: Sarah’s experience highlights the need for greater understanding and support for mental health issues in professional settings.

6. Stigma remains a significant barrier: Despite her progress, Sarah struggled with feelings of shame and fear of judgment related to her depression diagnosis and treatment.

Sarah’s case study provides a vivid illustration of the complexities of depression and the power of comprehensive, individualized treatment approaches. By examining her journey, we gain valuable insights into the lived experience of depression, the challenges of seeking and maintaining treatment, and the potential for recovery.

The significance of case studies in understanding and treating mental health conditions cannot be overstated. They offer a level of detail and nuance that complements broader research methodologies, providing clinicians and researchers with invaluable insights into the diverse manifestations of mental health disorders and the effectiveness of various interventions.

As we continue to explore mental health through case studies, it’s important to recognize the diversity of experiences within conditions like depression. Personal Bipolar Psychosis Stories: Understanding Bipolar Disorder Through Real Experiences offers insights into another complex mental health condition, illustrating the range of experiences individuals may face.

Furthermore, it’s crucial to consider how mental health issues are portrayed in popular culture, as these representations can shape public perceptions. Understanding Mental Disorders in Winnie the Pooh: Exploring the Depiction of Depression provides an interesting perspective on how mental health themes can be embedded in seemingly lighthearted stories.

The field of mental health research and treatment continues to evolve, driven by the insights gained from individual experiences and comprehensive studies. By combining the rich, detailed narratives provided by case studies with broader research methodologies, we can develop more effective, personalized approaches to mental health care. As we move forward, it is essential to continue exploring and sharing these stories, fostering greater understanding, empathy, and support for those facing mental health challenges.

References:

1. World Health Organization. (2021). Depression. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

2. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

3. Beck, A. T., & Alford, B. A. (2009). Depression: Causes and treatment. University of Pennsylvania Press.

4. Cuijpers, P., Quero, S., Dowrick, C., & Arroll, B. (2019). Psychological treatment of depression in primary care: Recent developments. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(12), 129.

5. Malhi, G. S., & Mann, J. J. (2018). Depression. The Lancet, 392(10161), 2299-2312.

6. Otte, C., Gold, S. M., Penninx, B. W., Pariante, C. M., Etkin, A., Fava, M., … & Schatzberg, A. F. (2016). Major depressive disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2(1), 1-20.

7. Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping. Holt paperbacks.

8. Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage publications.

Similar Posts

Sjögren’s Syndrome and Depression: Understanding the Connection and Finding Hope

Sjögren’s syndrome is a complex autoimmune disorder that affects millions of people worldwide, primarily targeting the body’s moisture-producing glands. While the physical symptoms of this condition are well-documented, there’s a growing recognition of its impact on mental health, particularly in relation to depression. The prevalence of depression among Sjögren’s patients is significantly higher than in…

Country Songs about Depression: Finding Solace in Melody

From tear-stained guitar strings to heartfelt honky-tonk harmonies, country music has long been a sanctuary for those grappling with the shadows of depression and anxiety. The raw emotion and storytelling prowess of country artists have created a unique space where listeners can find solace, understanding, and even hope in the face of mental health struggles….

Understanding VA Depression Rating and Disability Compensation

Navigating the labyrinth of VA depression ratings and disability compensation can be a daunting journey for veterans seeking the support they deserve. The process involves understanding complex criteria, gathering substantial evidence, and navigating a bureaucratic system that can often feel overwhelming. However, with the right knowledge and guidance, veterans can effectively pursue the benefits they’ve…

Understanding the Link Between MTHFR Mutation and Depression

Hidden within the depths of our genetic code, a tiny mutation in the MTHFR gene could be silently influencing our mental health, potentially unlocking the mysteries behind depression and its complex origins. This intriguing connection between our genes and mental well-being has captivated researchers and medical professionals alike, prompting a deeper exploration into the intricate…

Meltdown vs Anxiety Attack: Understanding the Differences and Similarities

Chaos erupts within, leaving you grasping for control as your mind and body wage war against an unseen enemy—but is it a meltdown or an anxiety attack? This question plagues many individuals who find themselves in the throes of intense emotional and physical distress. While both experiences can be overwhelming and distressing, understanding the nuances…

Understanding the Process: How Hard Is It to Get Disability for Depression?

Depression whispers lies, but the path to disability benefits shouts a truth many need to hear: help is available, even if the journey seems daunting. For those grappling with the debilitating effects of depression, understanding the process of obtaining disability benefits can be a crucial step towards securing financial stability and focusing on recovery. This…

Cambridge Core purchasing will be unavailable Sunday 22/09/2024 08:00BST – 18:00BST, due to planned maintenance. We apologise for any inconvenience. Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist

- > Volume 15

- > CBT for difficult-to-treat depression: single complex...

Article contents

- Key learning aims

Background to the case study

Key practice points, data availability statement, author contributions, financial support, conflicts of interest, ethical standards, cbt for difficult-to-treat depression: single complex case.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 August 2022

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for depression but a significant minority of clients are difficult to treat: they are more likely to have adverse childhood experiences, early-onset depression, co-morbidities, interpersonal problems and heightened risk, and are prone to drop out, non-response or relapse. CBT based on a self-regulation model (SR-CBT) has been developed for this client group which incorporates aspects of first, second and third wave therapies. The model and treatment components are described in a concurrent article (Barton et al ., 2022). The aims of this study were: (1) to illustrate the application of high dose SR-CBT in a difficult-to-treat case, including treatment decisions, therapy process and outcomes, and (2) to highlight the similarities and differences between SR-CBT and standard CBT models. A single case quasi-experimental design was used with a depressed client who was an active participant in treatment decisions, data collection and interpretation. The client had highly recurrent depression with atypical features and had received several psychological therapies prior to receiving SR-CBT, including standard CBT. The client responded well to SR-CBT over a 10-month acute phase: compared with baseline, her moods were less severe and less reactive to setbacks and challenges. Over a 15-month maintenance phase, with approximately monthly booster sessions, the client maintained these gains and further stabilized her mood. High dose SR-CBT was effective in treating depression in a client who had not received lasting benefit from standard CBT and other therapies. An extended maintenance phase had a stabilizing effect and the client did not relapse. Further empirical studies are underway to replicate these results.

(1) To find out similarities and differences between self-regulation CBT and other CBT models;

(2) To discover how self-regulation CBT treatment components are delivered in a bespoke way, based on the needs of the individual case;

(3) To consider the advantages of using single case methods in routine clinical practice, particularly with difficult-to-treat cases.

CBT based on a self-regulation model (SR-CBT) is a cognitive behavioural therapy for difficult-to-treat depression (McAllister-Willams et al ., Reference McAllister-Williams, Arango, Blier, Demyttenaere, Falkai, Gorwood, Hopwood, Javed, Kasper, Malhi, Soares, Vieta, Young, Papadopoulos and Rush 2020 ; Rush et al ., Reference Rush, Sackeim, Conway, Bunker, Hollon, Demyttenaere, Young, Aaronson, Dibué, Thase and McAllister-Williams 2022 ). The model and treatment components are described in a concurrent article (Barton et al ., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Robinson and Bromley 2022 ) and readers are encouraged to read that article for more details about the theoretical framework and how the treatment components are derived from it. The aim of this article is to illustrate the application of SR-CBT in a difficult-to-treat case of depression, in particular how the treatment components were organized and delivered, and how these influenced the process and outcome of therapy. SR-CBT has 10 treatment components and a key part of the approach is individualizing therapy based on the case formulation. Individualizing means varying the sequence, combination and dose of the treatment components, based on client need – it does not mean drifting from the therapist actions prescribed in the components.

The client in question was an active participant in the research process. She suffered from highly recurrent depression, with atypical mood fluctuations, and had received several treatments over the previous 13 years, including anti-depressant medication, computer-assisted CBT, counselling, psychodynamic psychotherapy, group-based mindfulness-based CBT, individual CBT, and intermittent care from a community mental health team and crisis team. She had received temporary but not lasting benefit from these interventions, gaining support, psychoeducation and coping skills, but not lasting remission from depression. She concurred that her depression was difficult to treat, acknowledging that there had been difficulties for both her and her previous therapists. Following assessment at the Centre for Specialist Psychological Therapies, the client was given the choice between a further course of standard CBT and a course of SR-CBT. She was given information, had an opportunity to ask questions and chose SR-CBT, explaining that the previous CBT been helpful but not lasting, and she would prefer to try a novel treatment.

At the time of the assessment, the client had been keeping a daily mood diary over the previous 16 months (514 days), during which time she had received a course of standard CBT (15 sessions), anti-depressant medication (ADM) and support from a community mental health team (CMHT). The daily diary created an opportunity for a baseline phase against which the SR-CBT could be compared and tested. The opportunity for a quasi-experiment was only recognized at this point, so the case study was limited to the mood measure that the client had been using in her previous care. The sequence of SR-CBT delivered after CBT, ADM and CMHT was not randomized or open to experimental control. Nevertheless, this case study is a good example of naturalistic practice-based evidence, with a high level of collaboration and participation from the service user. She recognized the value of continuing to complete the mood diary as a way of comparing SR-CBT with previous treatments, and was supportive of her treatment being summarized in this article, taking an active role in ensuring confidentiality within the write-up (several personal details are anonymized). She declined the opportunity to be a co-author but provided feedback on drafts and was satisfied with how the therapy had been summarized and discussed. The first author (S.B.) was the therapist, and he received monthly supervision throughout from the second author (P.A.).

Demographics and mental health history

Evelyn (psydonym) was a 52-year-old married woman with two grown-up daughters from a previous marriage. She first presented to mental health services aged 39, diagnosed with recurrent depressive disorder. She reported occasional episodes of depression as an adolescent that became more frequent and problematic in her late 20s and 30s. Evelyn’s marriage broke down when she was 42 and this precipitated an intense experience of personal failure, a severe depressive episode and a serious suicide attempt. In the subsequent 10 years, Evelyn experienced intermittent severe depressive episodes within the same phasic pattern. During periods of milder depression, Evelyn could be energized and engaged in her work as managing director of a company. These phases fell short of the threshold for hypomania: bipolar II disorder was not diagnosed, but psychiatric evaluation suggested an atypical phasic pattern of alternating mild, moderate and severely depressed moods with a high level of unpredictability from one day to the next.

Treatment phases

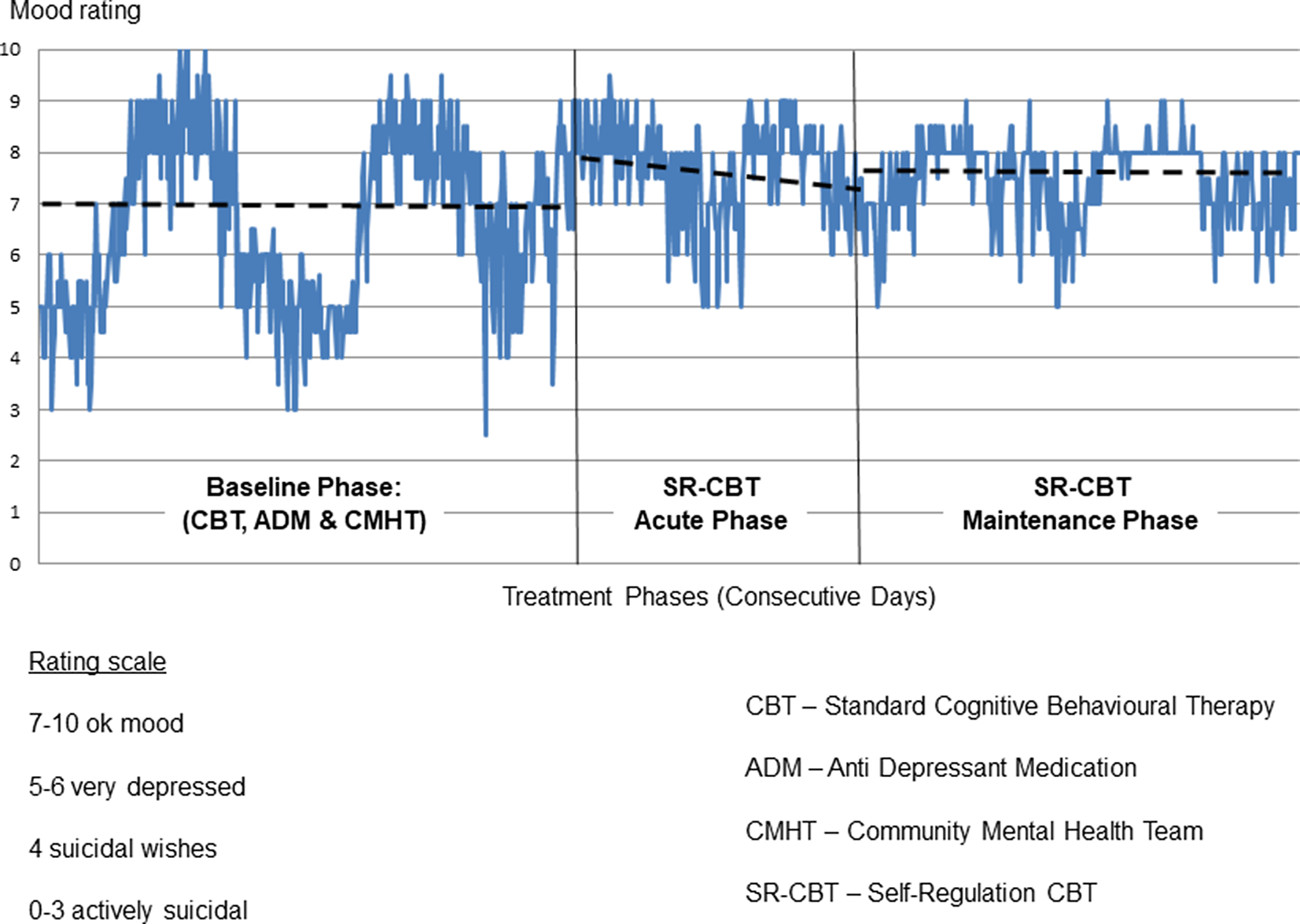

Up to 30 sessions is the usual dose of SR-CBT for clients with difficult-to-treat depression, and Evelyn received 27 sessions of SR-CBT over a 10-month acute phase (306 days). Her pre-treatment Patient Health Questionnaire score was 19 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al ., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams 2001 ) indicating moderate depression symptoms, and her GAD-7 score was 5, confirming depression as the primary problem (Spitzer et al ., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe 2006 ). Evelyn’s moods were subject to a lot of fluctuations and this pattern is depicted in a graph of her daily mood ratings (Fig. 1 ). The ratings were made on the following 11-point scale, with higher numbers representing milder depression: 7–10, OK mood; 5–6, very depressed; 4, suicidal wishes; 0–3, actively suicidal.

Figure 1. Evelyn’s daily mood ratings across treatment phases.

Evelyn was at heightened risk of relapse due to adverse childhood experiences, early onset depression, multiple previous episodes and unstable remission (Bockting et al ., Reference Bockting, Hollon, Jarrett, Kuyken and Dobson 2015 ). For this reason, she was offered a maintenance phase of monthly booster sessions after the acute phase was completed, with the goal of maintaining progress and staying well (Jarrett et al ., Reference Jarrett, Kraft, Doyle, Foster, Eaves and Silver 2001 ). This was initially expected to last 6 months, but it was extended to 15 months (15 sessions, 463 days) to accommodate Evelyn’s learning process and heightened risk. Evelyn continued to take anti-depressant medication and have intermittent CMHT support during both phases of SR-CBT.

Treatment process

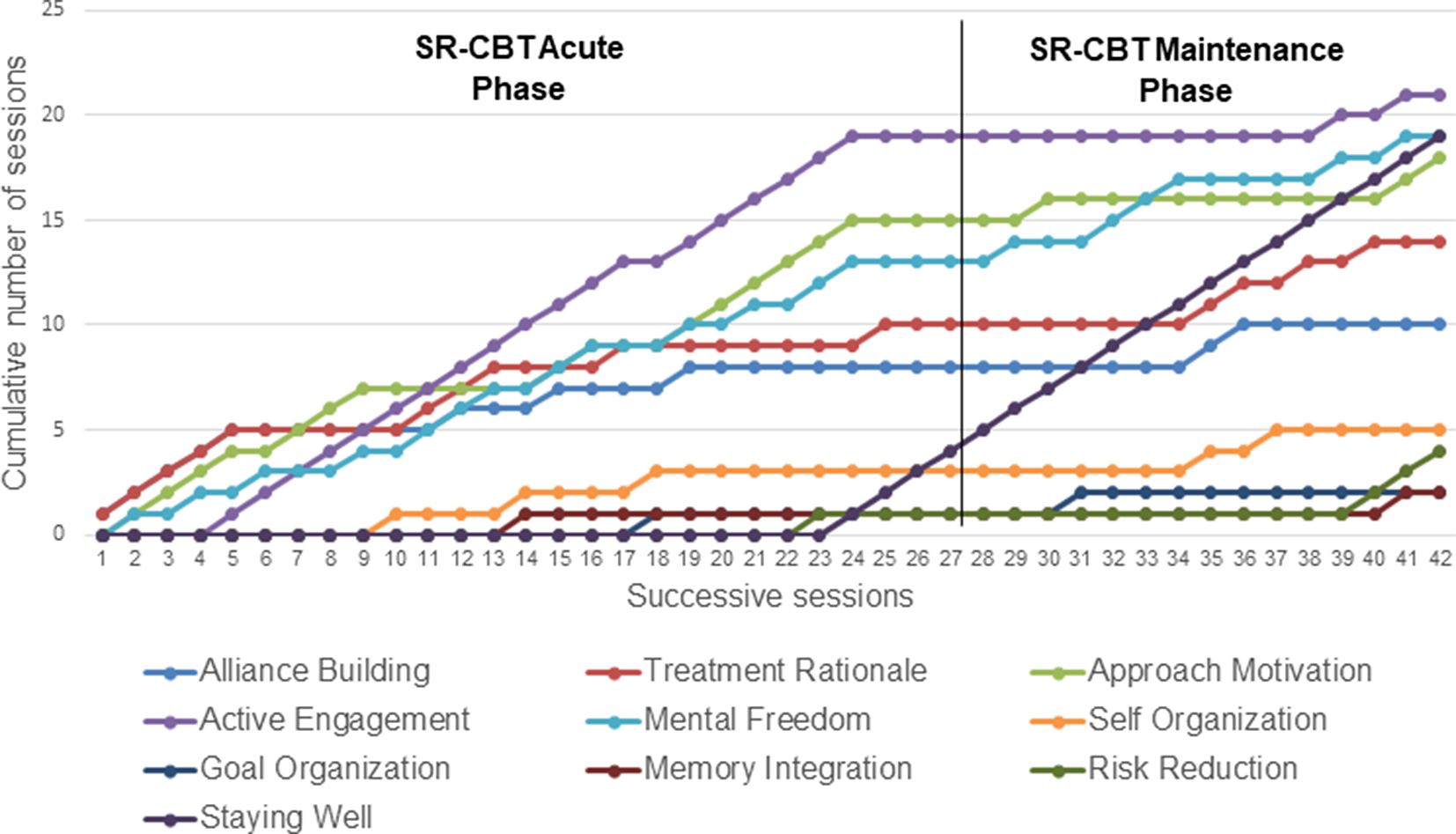

Emphasis was placed on the self-regulation skills that Evelyn most needed to develop, based on her case formulation. To provide an overview of when and how the components were delivered, the acute and maintenance phases have been combined in the following summary. The number of sessions in which each component formed a significant part are presented in a cumulative plot in Fig. 2 . Sessions usually combined more than one treatment component (mean = 2.77 per session). The way each component was delivered, and the number of sessions in which they formed a part, are described below.

Figure 2. SR-CBT treatment components: cumulative number of sessions in which each component was delivered.

Alliance building (10/42 sessions)

An effective working alliance was established with Evelyn over the first five sessions. She was trusting and respectful and the personal alliance formed easily. The task alliance, reflected in alignment on target problems, goals and therapy tasks, was more challenging to develop, and there were three barriers (Barton et al ., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Wicks, Freeman and Meyer 2017 ; Cameron et al ., Reference Cameron, Rodgers and Dagnan 2018 ). Firstly, Evelyn was ambivalent about receiving further CBT and unsure whether it would differ from her previous therapy. Her initial motivation came from a sense of obligation to her husband, who encouraged her to try new therapies. Evelyn was not optimistic that SR-CBT would produce benefits that were different or greater than previous therapies. Secondly, Evelyn’s mood disorder was highly persistent with several recurrent major episodes and an atypical pattern of mood fluctuations. Even if she responded to SR-CBT, she would have heightened risk of relapse (Wojnarowski et al ., Reference Wojnarowski, Firth, Finegan and Delgadillo 2019 ). Thirdly, Evelyn had suffered adverse childhood experiences in her birth family for which she felt partly responsible. She felt uncomfortable discussing herself, and was particularly reluctant to discuss early experiences in case she was perceived to be blaming her parents.

The therapist’s response was to guide discovery about each of these issues, making them explicit and investing time to reach an aligned position. The therapist sought to differentiate SR-CBT from standard CBT, encouraging Evelyn to find out if it was similar or different by committing to a small number of sessions initially. This increased Evelyn’s agency to engage in the therapy, without the therapist taking too much responsibility for change. The therapist also emphasized the need for two phases of treatment, the first to improve Evelyn’s mood and the second to sustain those changes. The risk of relapse was acknowledged at the outset, with a pro-active approach emphasizing that staying well depended on applying self-regulation skills that could be learned during treatment. Finally, the therapist acknowledged that a strong relationship was needed to discuss painful childhood experiences, and Evelyn did not need to decide at the start of therapy whether she wanted to do this later. These conversations had an alliance-strengthening effect, sufficient to proceed with the other treatment components. Throughout treatment, the therapist had to be robust in maintaining the task alliance to keep the therapy sufficiently change-focused.

Treatment rationale (14/42 sessions)

The treatment rationale in SR-CBT is to reflect on mood fluctuations, differentiating depressed and less-depressed moods and using this to leverage change. Depressed moods help to formulate how depression is maintained; less-depressed moods help to find a path out of depression. Evelyn readily accepted that there were a lot of fluctuations in her moods. She found it particularly frustrating, and bewildering, that her moods could plummet from mild to severe in a short space of time with no apparent trigger. She accepted the logic that less-depressed moods could help to find a path out of depression, but in practice she would default to discussing depression, trying to find out what had triggered it so that she could avoid those triggers. Avoiding triggers was one of the strategies she had learned in previous treatments. In Evelyn’s case, this strategy was maintaining behavioural avoidance and rumination (e.g. ‘why do these keep happening?’). She gradually accepted that she could not always discover what the triggers were, and also came to realize that avoiding triggers was not the best strategy, because they were difficult to predict and attempting to do so maintained an avoidant orientation: trying to dodge undetermined hazards, rather than influencing situations in a preferred direction (Quigley et al ., Reference Quigley, Wen and Dobson 2017 ).

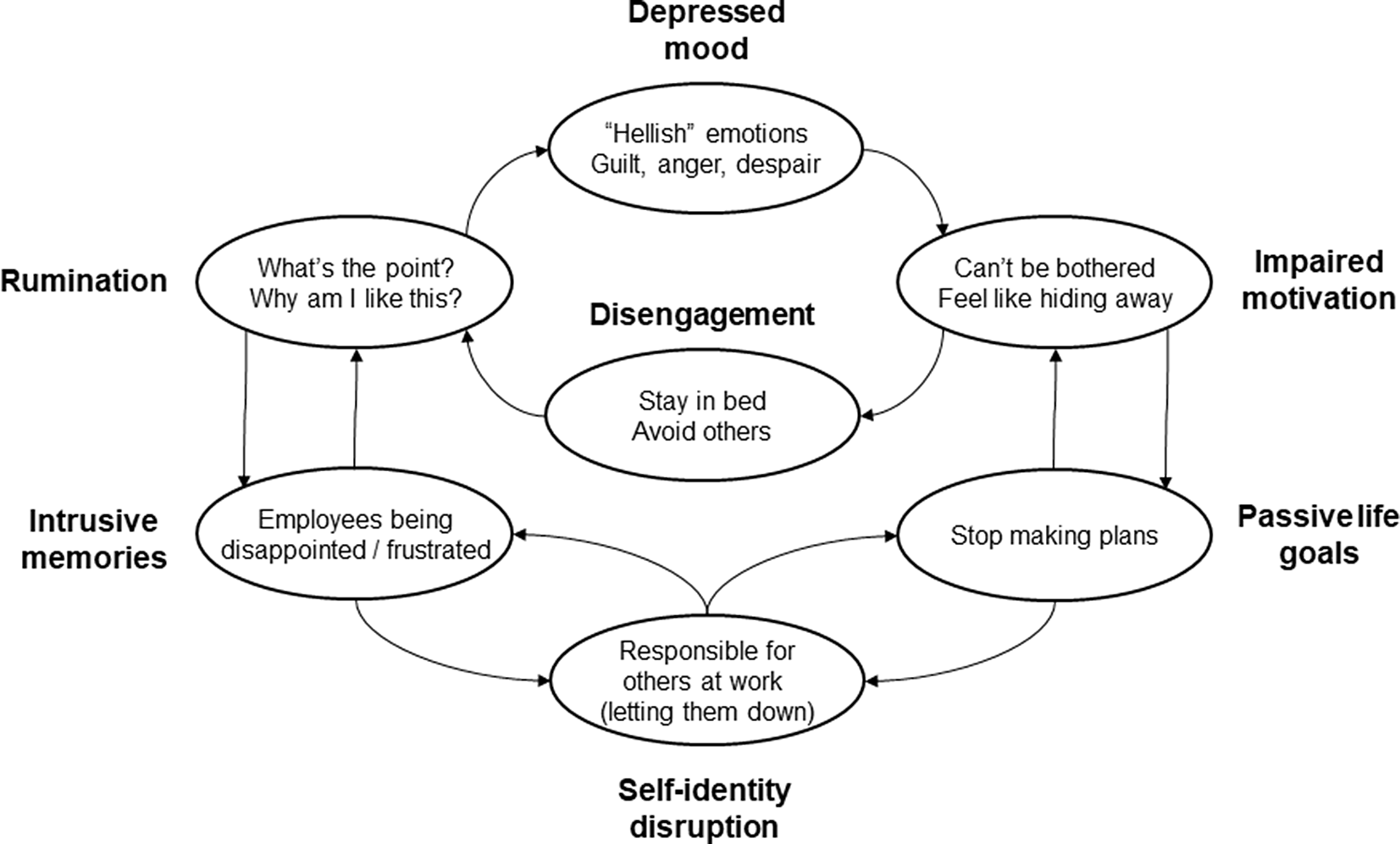

Over the first five sessions, Evelyn was socialized to key features of the self-regulation model. The model proposes that depression is perpetuated by repeated interactions of self-identity disruption, impaired motivation, disengagement, rumination, intrusive memories and passive life-goals. The repeated interaction of these processes maintains depression like a traffic gridlock (Barton and Armstrong, Reference Barton and Armstrong 2019 ; Teasdale and Barnard, Reference Teasdale and Barnard 1993 ). Figure 3 presents Evelyn’s formulation which was built up over several sessions.

Figure 3. Evelyn’s case formulation.

Evelyn’s self-identity was narrowly invested in taking responsibility for others through her work as a managing director. This was a positive self-representation in the sense that it provided self-definition, value and purpose. Evelyn ascribed importance to doing her job well and was highly invested in that goal. This does not mean that she had consistently positive beliefs about doing a good job; in fact, these fluctuated a great deal. She experienced phases of work going reasonably well when she reported her mood to be ‘OK’, but small setbacks at work (real or perceived) had a disproportionate effect on her mood. She could switch rapidly into a self-loathing, unmotivated, withdrawn, ruminative state, pre-occupied with memories of letting others down and uninterested in planning for the future. When Evelyn’s depression was milder, she would engage in work tasks with some interest and a felt-sense of obligation, sometimes over-working, joining in with others and experiencing some job satisfaction. She recognized that her attention was more externally focused on these occasions, and she was more able to think clearly and make decisions.

The treatment rationale was revisited regularly throughout therapy, particularly when Evelyn suffered setbacks and became despondent about change. When this happened, the therapist would re-focus attention on less-depressed moods and encourage Evelyn to keep influencing her motivation, actions and cognition. To effect change, sufficient emphasis has to be placed on less-depressed experiences, and to achieve this the treatment rationale usually has to be revisited regularly.

Approach motivation (18/42 sessions)

Approach motivation is often delivered in combination with active engagement (see below). The aim is to stimulate approach impulses which are usually attenuated during depression with reduced positive anticipation, lower reward expectancies and weakened interest in desired outcomes (Sherdell et al ., Reference Sherdell, Waugh and Gotlib 2012 ). When reflecting on Evelyn’s less-depressed moods, the therapist questioned her motivational impulses and intentions; for example, when she felt some satisfaction after a particular work meeting. This increased the explicitness of Evelyn’s desires to support the staff that worked in her company, to whom she felt very responsible. Rather than focusing on responsibility beliefs, the therapist asked what Evelyn would like to happen in her organization, and how she would like key staff to develop. These desires were elaborated in a lot of detail and they helped to generate reasons for action; for example, to influence work culture and strategic direction.

Another example was bringing attention to what Evelyn needed when she felt negative emotions; for example, upset, guilt, sadness or anger. Her tendency was to suppress negative emotions because they would often activate depressing thoughts and provoke rumination. She had not considered emotions as signalling needs, for example, the need for self-soothing, forgiveness, support, grieving, communication, fairness, etc. Evelyn was not accustomed to reflecting on her needs and desires in this way, initially appraising it as selfish. This was unfamiliar and uncomfortable for her – even dystonic at times – and took a long time to make sense and sit more comfortably. Attending to needs and desires is self-compassionate: it signals the value of responding to one’s suffering and attempting to alleviate it, and of taking desires seriously and wanting to realize them. Repeated attention to Evelyn’s needs and desires helped to generate reasons for action and, over an extended period, reasons to act gradually became impulses for action.

Active engagement (21/42 sessions)

The goal of active engagement is to increase clients’ interaction with tasks and other people, with engagement targeted in situations where the client tends to disengage, withdraw and/or avoid (Ottenbreit et al ., Reference Ottenbreit, Dobson and Quigley 2014 ). There is a big emphasis on experimentation, with clients encouraged to try out new ways of interacting, including how they relate to themselves. The focus is on setting goals to influence preferred outcomes and aligning those goals with needs and desires. Consequently, the output of approach motivation is often used to plan experiments within active engagement.

In Evelyn’s therapy, 50% of the sessions involved planning a behavioural experiment to be conducted before the next session, and this would often relate to a work commitment that Evelyn’s secretary had booked in, or a personal engagement that her husband had arranged for them. It was normal for Evelyn to be dreading these and feel like withdrawing from them. From session 6 onwards, the repeating therapeutic pattern was exploring prospectively what Evelyn would like to happen in those situations. Time was taken to plan how she wanted to approach the situation, emphasizing how she would interact and communicate with others, to try to influence what she would like to happen. She would also consider which mindset she needed to be in before, during and after the situation, in particular where to place her attention and how to keep preferences in mind. Sessions would end with Evelyn stating her preferred outcomes, not her predictions, and the experiment was to find out if and how she could influence those preferences. A de-brief was planned for the next session.

Examples include feeling despondent about not having sufficient administrative support in her office, even though she was the managing director of the company. When feeling depressed, it did not occur to Evelyn that she had the authority and influence to hire more staff, imagining that this would be blocked by red tape that was out of her control. The therapist dis-attended to Evelyn’s negative predictions and kept attention on what she would like to happen in this situation. With some reluctance and difficulty, Evelyn slowly worked back from the desired outcome and, over a number of weeks, the staffing was increased. Another example was dreading a visit to see her elderly parents, feeling like cancelling on the pretence of ill-health. The therapist enquired about the best and worst memories of visiting her parents, and this helped Evelyn to identify what she was most dreading: feeling trapped in their home, unable to leave (see self-organization section). By staying focused on what she would like to happen (e.g. having her own space, going out when she wanted), Evelyn developed a plan to stay in a local hotel and let her parents know in advance that she was increasing physical exercise. These possibilities had not previously occurred to Evelyn, and overall they contributed to a more tolerable family visit.

Evelyn struggled with active engagement for several months, preferring to talk about negative experiences that had occurred in the previous week, and was sometimes frustrated that the therapist did not pay much attention to her negative predictions. The personal alliance was sufficiently strong to withhold this, so the therapist kept the task alliance as the priority (i.e. change-focus). After 6 months of slow learning, a threshold was reached and Evelyn started to internalize the active engagement process that she had applied across several experiments. When she paid attention to her preferred outcomes, and formed an intention to bring them about, she was usually able to influence them in some way, even if it was not in the way she had expected.

Mental freedom (19/42 sessions)

The aim of mental freedom is to develop a good self-mind relationship with reflective capacity, attentional skills and productive questioning. The first step is to increase awareness of the difference between rumination and reflection and this occurred in the first six sessions when the treatment rationale and initial formulation was developed. Evelyn accepted that rumination was unhelpful but she did not always recognize when it was happening (Watkins and Roberts, Reference Watkins and Roberts 2020 ). When her mood lifted, she was usually able to reflect back on her experiences and recognize that rumination had occurred. It took several months for Evelyn to become aware of rumination when it was happening in the moment, and then she felt minimal control over it. As her reflective capacity increased, Evelyn developed more attentional skills. This grew out of the recognition that she tended to be self-focused in depressed moods and more externally focused in less-depressed moods. External focus of attention became a regular part of active engagement. This gradually gave her a tool to use when feeling more depressed, choosing to place her attention externally, when she remembered to do so. This was not sufficient to prevent all depression and rumination, but it had a beneficial effect and was the beginning of Evelyn learning how to influence her cognition during depressed moods.

The intervention that had greatest impact was recognizing the unhelpfulness of the questions she asked herself when feeling depressed, such as: ‘what’s the point?’, ‘why bother?’, ‘why can’t I be normal like everyone else?’, etc. These thoughts indicated how distressed, frustrated and angry Evelyn could become with herself. When her mood was less depressed, Evelyn brought these questions to mind in cognitive experiments within therapy sessions: the presence of the questions depressed her mood, brought negative thoughts to mind and led to unhelpful answers. Evelyn recognized their unhelpfulness, but didn’t know how to think differently, especially when feeling depressed. With the therapist’s guidance, she was able to experiment with different types of question such as ‘how can I help myself right now?’, ‘what do I need to do next?’, ‘who can I talk to?’. Evelyn recognized that these were more helpful, concrete and practical questions, giving her ideas for action, and that this was a better way to respond when feeling down. She started monitoring her questions at work, particularly when feeling burdened or guilty, and there was a gradual shift from less to more helpful questioning (e.g. ‘why do I keep messing up?’ became ‘did I make a mistake?’). The challenge was helping Evelyn to access reflective thinking when she most needed it, when her mood was 6/10 or less. Initially she was only able to apply these skills when her mood was 7/10 or greater, and this became one of the key aims of relapse prevention and staying well.

Self-organization (5/42), goal organization (2/42) and memory integration (2/42 sessions)

In the self-regulation model, vulnerability to depression results from the under-development of positive self-representations and their associated self-regulatory capacities, rather than the presence negative beliefs. The main aim of self-organization is to strengthen, diversify and re-structure positive self-representations. The main aim of memory integration is to elaborate positive recollections to increase their memorability and accessibility, when possible making explicit links to positive self-representations. The main aim of goal-organization is to structure life-goals so they are approach-based, concrete, imaginable and span a range of self-representations.

The main hypothesis about Evelyn’s vulnerability to depression was that her early family experiences limited the development of positive self-representations and associated life skills. When growing up, Evelyn endured several years of marital discord, conflict and miscommunication, with her parents unaware of its psychological impact on her. As time passed, Evelyn felt increasingly responsible for her family’s unhappiness, unable to solve her parents’ difficulties. She internalized a lot of unhappy memories and often felt helpless, unable to escape or improve the family situation. Her parents’ dissatisfaction with each other captured much of their attention, and Evelyn’s need for emotional support, encouragement and soothing was often overlooked.

This was compensated, to some degree, by her intelligence and aptitude at school where she was responsible, hard-working and successful, but her capacity to encourage herself and self-soothe was not consistently supported at home. On the contrary, the family atmosphere was characterized by criticism and harshness, which came to reflect Evelyn’s relationship with herself. Being responsible, intelligent and hard-working led to a successful path through school, university and her subsequent career, but her positive self-representations were few in number, narrowly invested in feeling responsible to others, particularly in her role as a managing director. This brought her a lot of career success and some periods of euthymic mood, but she had limited resilience to buffer negative interpersonal experiences when, as she perceived it, she made mistakes or let others down. As we have already observed, when her self-identity as a responsible managing director was disrupted Evelyn could switch rapidly into self-attack, self-blame and self-loathing.

Focusing on personal qualities was very challenging for Evelyn because she was very uncomfortable receiving positive feedback; it jarred as if it had no place within her. Throughout therapy, the therapist would comment on Evelyn’s good humour, compassion, intelligence and work expertise, in an attempt to strengthen her acceptance of these qualities, but this was limited by Evelyn’s reluctance to participate in this type of change. It is possible that Evelyn would have benefited from greater therapeutic focus on her memories, self-identity and life-goals, but throughout therapy she remained uncomfortable discussing herself, her early life in particular, and this limited the depth of self re-organization that was possible.

Risk reduction (4/42 sessions)

The aim of risk reduction is to reduce suicide risk when it is increased. Clients’ motives are explored in detail by asking about the intended and unintended consequences of suicidal actions. When feeling suicidal, clients’ attention often narrows around a specific need, for example, to be re-united with a loved one, to escape, to experience relief or put an end to a particular feeling. Evelyn’s mood rating did not enter the suicidal range (4/10 or less) during the course of SR-CBT, but there were occasions when she was bothered by suicidal thoughts, and on those occasions the therapy helped her to explore the goal of suicide: what did Evelyn imagine suicide would achieve? In Evelyn’s case, she believed it could result in ‘an end to hellish feelings’ and ‘not having to be me anymore’. This was tempered by potential unintended consequences, including pain, injury, illness and her husband being devastated. Evelyn recognized an inner battle between these pros and cons that she had lived with over several years.

The therapy tried to broaden Evelyn’s attention onto other life-goals and reasons for living, including seeing her company grow, supporting the development of key colleagues and enjoying holidays with her husband (Linehan et al ., Reference Linehan, Goodstein, Nielsen and Chiles 1983 ). Most importantly, it tried to identify non-lethal ways to respond to her felt-need to avoid ‘hellish’ emotions and escape herself. The main strategy was to encourage Evelyn to switch from avoidance to approach. Rather than avoid these feelings, she was encouraged to influence them so they occurred less frequently and respond to them differently when they were present. Rather than escape herself, she was encouraged to submit to a deeper acceptance of her personal qualities. Some of this therapeutic work was acutely uncomfortable for Evelyn, but it appeared to contribute to her increased safety over the course of the treatment.

Staying well (19/42 sessions)

Towards the end of the acute phase, four sessions of staying well were provided, aiming to consolidate the skills Evelyn had learned during therapy and apply them more independently (Jarrett et al ., Reference Jarrett, Kraft, Doyle, Foster, Eaves and Silver 2001 ). There remained an unpredictability in Evelyn’s moods that was frustrating and difficult for her to accept, and when her mood was more depressed (i.e. 6/10 or less) it was very difficult for her to remember and apply skills she had learned. It became apparent that this was a significant struggle for Evelyn, and this was what prompted the offer of maintenance therapy. This was initially expected to be monthly for 6 months, but it was extended to 15 months, reflecting the size of the task. There were two main aims: (a) to make Evelyn’s self-regulation skills more explicit and memorable; and (b) to help her access the skills when they were most needed, during depressed moods (i.e. 6/10 or less). Evelyn’s understanding of what she needed to do to stay well gradually became more explicit, and her skills became more automatic, but this was very slow learning that relied on multiple repetitions to become accessible during depressed moods.

Treatment outcomes

By the end of the acute SR-CBT phase, Evelyn’s PHQ-9 score had reduced from 19 to 2. This is a reliable change of more than 6 points that is also below the threshold for clinical caseness (McMillan et al ., Reference McMillan, Gilbody and Richards 2010 ). However, a pre–post comparison only takes account of two time-points and cannot capture the dynamics of mood patterns or changes within them. The daily mood ratings provided a richer description of those dynamics and also allowed comparisons between phases. The main questions were: (a) whether moods in the acute phase of SR-CBT were less depressed and more stable, compared with baseline; and (b) whether changes in mood during acute phase SR-CBT were sustained in the maintenance phase. Visual analysis of Fig. 1 confirms that there was a lot of variability within each phase, consistent with Evelyn’s formulation. A cyclical pattern was apparent, both within and across phases, with apparently milder depression and more stable mood during the SR-CBT phases (baseline median = 7; acute SR-CBT median = 8; maintenance SR-CBT median = 8). Evelyn’s risk was also less during SR-CBT: she scored 4 or less (indicating suicidal wishes) on 24/514 days during the baseline phase (4.6%) and 0/769 days during SR-CBT (0%).

Differences between phases were tested statistically using non-overlap methods (Morley, Reference Morley 2017 ; Parker and Vannest, Reference Parker, Vannest, Kratochwill and Levin 2014 ; Parker et al ., Reference Parker, Vannest, Davis and Sauber 2011 ). There was no significant trend within the baseline phase when Evelyn received standard CBT, ADM and CMHT (Tau-U=–0.028, Z=–0.963, p =0.336). The same underlying mood pattern was recurring without a significant trend towards better or worse mood, and this is reflected in the flat trend line in the baseline phase in Fig. 1 . There was therefore no need to control for baseline trend in the comparison with acute phase SR-CBT, which revealed a statistically significant improvement in mood, consistent with Fig. 1 (Tau-U=0.257, Z=6.167, p <0.001). Compared with baseline, Evelyn’s moods were significantly milder during acute SR-CBT, but there was also a significant decreasing trend during the acute phase which, without further intervention, could have led to relapse (Tau-U=–0.151, Z=–3.934, p <0.001). This is depicted in the sloping trend line in the acute phase in Fig. 1 . With this trend statistically controlled, there was a significant difference between acute phase SR-CBT and maintenance phase SR-CBT, favouring the maintenance phase (Tau-U=–0.093, Z=–2.192, p =0.028). Evelyn’s mood was more stable in the maintenance phase, with no significant trend for worsening or further improvement (Tau-U=–0.035, Z=–1.114, p =0.265). This is reflected in the flat trend line in the maintenance phase in Fig. 1 .

This single case demonstrates how SR-CBT is organized and delivered across a course of therapy. Because Evelyn kept a mood diary over an extended period, comparisons could be made between treatment phases. The case demonstrates the aim of SR-CBT: to provide effective therapy for difficult-to-treat clients who have received standard CBT in the past but where it has not had a beneficial or lasting effect (Barton and Armstrong, Reference Barton and Armstrong 2019 ). The pattern of results is consistent with the model’s claims, that SR-CBT can provide an effective alternative when standard CBT has not been sufficiently potent (Barton et al ., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Robinson and Bromley 2022 ). There are alternative explanations for the changes observed during SR-CBT, for example, that positive life events or other treatments were responsible for the effects. However, Evelyn attributed the changes to SR-CBT; there were no major positive life events during the 25 months of her treatment; she continued to take anti-depressant medication and receive CMHT support, but there were no substantial changes in medication and, due to her improvement, CMHT input was less than before.

Assuming that the changes are at least partly attributable to SR-CBT, this case does not provide evidence that SR-CBT is more effective than standard CBT; it does not address that question. The case is illustrative and not a comparative test: it is one case, without randomization or replication. A scientific comparison of cognitive therapy vs behavioural activation vs SR-CBT would need to balance the order in which they were received, since Evelyn’s gains during SR-CBT could be partly attributable to the preparatory effects of previous therapy. It would also need to match treatment doses and use a broader range of measures: 42 sessions is significantly greater than 15 sessions, which was the dose of the standard CBT she received in the baseline phase. Nevertheless, what can be claimed is that, in this particular case, high dose SR-CBT coincided with positive changes in mood that did not occur during standard CBT at a normal dose, and these changes were sustained over a 15-month maintenance phase. The enduring effect of SR-CBT in this case echoes the lasting benefits reported in an earlier version of this treatment (Barton et al ., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Freeston and Twaddle 2008 ).

Although a single case is limited without replication, single case methods have the potential to address issues in the field that are normally approached through randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. For example, the bespoke combination of treatment components is open to empirical scrutiny to find out how much variance occurs across cases, and whether the same or different ingredients are associated with better outcomes. If it is the same ingredients, SR-CBT could become more protocolized in the future; if it is different ingredients, there is a case for continued individualization with this client group. Repeated measure designs also have the potential to detect trends that are not usually measured in RCTs, the best example in this study being the decreasing trend in the acute SR-CBT phase, even though this phase had significantly milder depression than the baseline. If this pattern was replicated in other cases, it could be a way of detecting empirically which cases are at greater risk of relapse through their response to acute phase treatment.

Two further questions need to be addressed. Firstly, how similar or different is SR-CBT compared with standard CBT? Therapists use core CBT skills to provide SR-CBT and it certainly has overlaps with other CBT treatments, for example, mental freedom shares features with rumination-focused CBT (Watkins and Roberts, Reference Watkins and Roberts 2020 ), and active engagement shares features with behavioural activation (Martell et al ., Reference Martell, Addis and Jacobsen 2001 ; Martell et al ., Reference Martell, Dimidjian and Herman-Dunn 2010 ) and activity scheduling in cognitive therapy (Beck et al ., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery 1979 ). Readers are encouraged to access the concurrent article that explores these similarities and differences in more detail (Barton et al ., Reference Barton, Armstrong, Robinson and Bromley 2022 ).

Secondly, are the effects of SR-CBT attributable to high dose treatment rather than specific treatment components? This possibility cannot be ruled out, but the change pattern depicted in Fig. 1 suggests a specific response to SR-CBT, rather than a simple dose effect. However, this question needs to be addressed through replication in further studies, and the health economics of high dose treatment also need consideration. Arguably, an effective high dose treatment for difficult-to-treat cases would save resources in the long term, given the healthcare costs incurred by treatment-resistant depression (Johnston et al ., Reference Johnston, Powell, Anderson, Szabo and Cline 2019 ). For some clients, fast learning is not possible and slow learning across a high intensity treatment may be more cost-effective than subsequent multiple brief episodes of care. For example, slower change is inevitable when working with non-verbal aspects of trauma, and this may be one of the reasons why treatment responses in chronic depression are superior for doses of 30 sessions or greater (Brewin et al ., Reference Brewin, Reynolds and Tata 1999 ; Cuijpers et al ., Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Schuurmans, van Oppen, Hollon and Andersson 2009 ). With respect to the current case, consider the costs incurred by Evelyn’s treatment in the 13 years prior to receiving SR-CBT, and the potential savings in the years ahead, if her treatment gains are sustained. The efficacy of SR-CBT and its health economics are now undergoing further empirical tests.

(a) When possible, increase the treatment dose compared with standard CBT.

(b) Pay more attention to building the working alliance by overcoming alliance barriers.

(c) Pay more attention to less-depressed moods as a way of finding a path out of depression.

(d) Conduct behavioural experiments that seek to influence clients’ preferences, rather than disconfirm their negative predictions.

(2) Therapists should consider using individualized measures, such as daily mood ratings, alongside standard measures as a way of observing trends and patterns of change.

Copies of the single case dataset are available from the first author on request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues who provided feedback on drafts and contributed to the development of the treatment components: Nina Brauner, Beth Bromley, Elisabeth Felter, Dave Haggarty, Youngsuk Kim, Lucy Robinson and Karl Taylor.

Stephen Barton: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Peter Armstrong: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Supervision (lead); Stephen Holland: Conceptualization (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Hayley Tyson-Adams: Conceptualization (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

The authors have abided by the ethical principles and code of conduct set out by the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies and British Psychological Society. The reported study is practice-based evidence and did not receive ethical approval in advance. In lieu of this, oversight was sought from CNTW Foundation Trust management which supported service-user involvement in collecting practice-based evidence. The service user was an active participant in the research process, read the manuscript and agreed to it going forward for publication.

Further reading

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Stephen B. Barton (a1) (a2) , Peter V. Armstrong (a1) , Stephen Holland (a1) and Hayley Tyson-Adams (a3)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X22000319

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability