- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Doctorate Degrees

- Certificate Programs

- Nursing Degrees

- Cybersecurity

- Human Services

- Science & Mathematics

- Communication

- Liberal Arts

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science

- Admissions Overview

- Tuition and Financial Aid

- Incoming Freshman and Graduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Military Students

- International Students

- Early Access Program

- About Maryville

- Our Faculty

- Our Approach

- Our History

- Accreditation

- Tales of the Brave

- Student Support Overview

- Online Learning Tools

- Infographics

Home / Blog

Speech Impediment Guide: Definition, Causes, and Resources

December 8, 2020

Tables of Contents

What Is a Speech Impediment?

Types of speech disorders, speech impediment causes, how to fix a speech impediment, making a difference in speech disorders.

Communication is a cornerstone of human relationships. When an individual struggles to verbalize information, thoughts, and feelings, it can cause major barriers in personal, learning, and business interactions.

Speech impediments, or speech disorders, can lead to feelings of insecurity and frustration. They can also cause worry for family members and friends who don’t know how to help their loved ones express themselves.

Fortunately, there are a number of ways that speech disorders can be treated, and in many cases, cured. Health professionals in fields including speech-language pathology and audiology can work with patients to overcome communication disorders, and individuals and families can learn techniques to help.

Commonly referred to as a speech disorder, a speech impediment is a condition that impacts an individual’s ability to speak fluently, correctly, or with clear resonance or tone. Individuals with speech disorders have problems creating understandable sounds or forming words, leading to communication difficulties.

Some 7.7% of U.S. children — or 1 in 12 youths between the ages of 3 and 17 — have speech, voice, language, or swallowing disorders, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). About 70 million people worldwide, including some 3 million Americans, experience stuttering difficulties, according to the Stuttering Foundation.

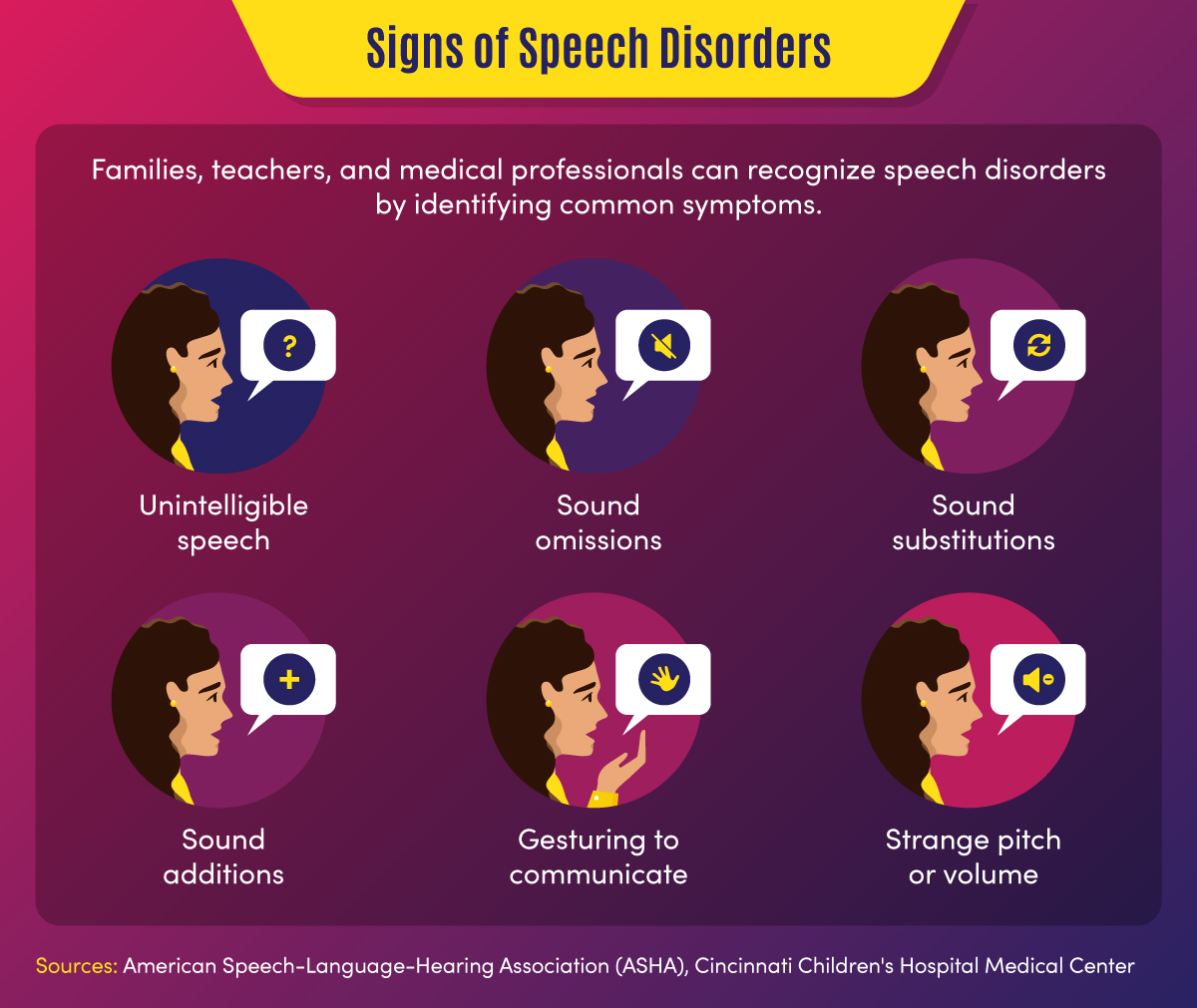

Common signs of a speech disorder

There are several symptoms and indicators that can point to a speech disorder.

- Unintelligible speech — A speech disorder may be present when others have difficulty understanding a person’s verbalizations.

- Omitted sounds — This symptom can include the omission of part of a word, such as saying “bo” instead of “boat,” and may include omission of consonants or syllables.

- Added sounds — This can involve adding extra sounds in a word, such as “buhlack” instead of “black,” or repeating sounds like “b-b-b-ball.”

- Substituted sounds — When sounds are substituted or distorted, such as saying “wabbit” instead of “rabbit,” it may indicate a speech disorder.

- Use of gestures — When individuals use gestures to communicate instead of words, a speech impediment may be the cause.

- Inappropriate pitch — This symptom is characterized by speaking with a strange pitch or volume.

In children, signs might also include a lack of babbling or making limited sounds. Symptoms may also include the incorrect use of specific sounds in words, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). This may include the sounds p, m, b, w, and h among children aged 1-2, and k, f, g, d, n, and t for children aged 2-3.

Back To Top

Categories of Speech Impediments

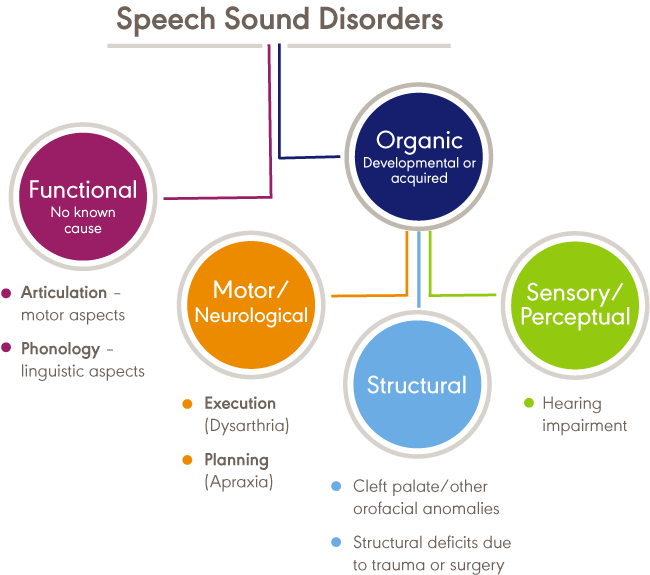

Speech impediments can range from speech sound disorders (articulation and phonological disorders) to voice disorders. Speech sound disorders may be organic — resulting from a motor or sensory cause — or may be functional with no known cause. Voice disorders deal with physical problems that limit speech. The main categories of speech impediments include the following:

Fluency disorders occur when a patient has trouble with speech timing or rhythms. This can lead to hesitations, repetitions, or prolonged sounds. Fluency disorders include stuttering (repetition of sounds) or (rapid or irregular rate of speech).

Resonance disorders are related to voice quality that is impacted by the shape of the nose, throat, and/or mouth. Examples of resonance disorders include hyponasality and cul-de-sac resonance.

Articulation disorders occur when a patient has difficulty producing speech sounds. These disorders may stem from physical or anatomical limitations such as muscular, neuromuscular, or skeletal support. Examples of articulation speech impairments include sound omissions, substitutions, and distortions.

Phonological disorders result in the misuse of certain speech sounds to form words. Conditions include fronting, stopping, and the omission of final consonants.

Voice disorders are the result of problems in the larynx that harm the quality or use of an individual’s voice. This can impact pitch, resonance, and loudness.

Impact of Speech Disorders

Some speech disorders have little impact on socialization and daily activities, but other conditions can make some tasks difficult for individuals. Following are a few of the impacts of speech impediments.

- Poor communication — Children may be unable to participate in certain learning activities, such as answering questions or reading out loud, due to communication difficulties. Adults may avoid work or social activities such as giving speeches or attending parties.

- Mental health and confidence — Speech disorders may cause children or adults to feel different from peers, leading to a lack of self-confidence and, potentially, self-isolation.

Resources on Speech Disorders

The following resources may help those who are seeking more information about speech impediments.

Health Information : Information and statistics on common voice and speech disorders from the NIDCD

Speech Disorders : Information on childhood speech disorders from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Speech, Language, and Swallowing : Resources about speech and language development from the ASHA

Children and adults can suffer from a variety of speech impairments that may have mild to severe impacts on their ability to communicate. The following 10 conditions are examples of specific types of speech disorders and voice disorders.

1. Stuttering

This condition is one of the most common speech disorders. Stuttering is the repetition of syllables or words, interruptions in speech, or prolonged use of a sound.

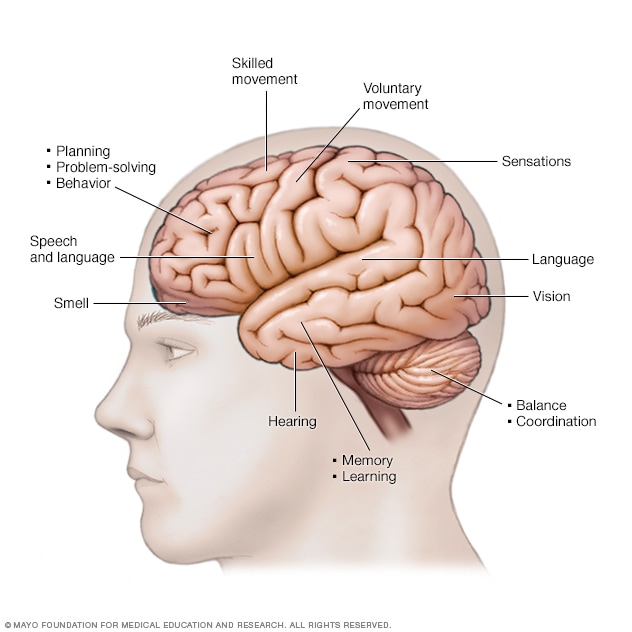

This organic speech disorder is a result of damage to the neural pathways that connect the brain to speech-producing muscles. This results in a person knowing what they want to say, but being unable to speak the words.

This consists of the lost ability to speak, understand, or write languages. It is common in stroke, brain tumor, or traumatic brain injury patients.

4. Dysarthria

This condition is an organic speech sound disorder that involves difficulty expressing certain noises. This may involve slurring, or poor pronunciation, and rhythm differences related to nerve or brain disorders.

The condition of lisping is the replacing of sounds in words, including “th” for “s.” Lisping is a functional speech impediment.

6. Hyponasality

This condition is a resonance disorder related to limited sound coming through the nose, causing a “stopped up” quality to speech.

7. Cul-de-sac resonance

This speech disorder is the result of blockage in the mouth, throat, or nose that results in quiet or muffled speech.

8. Orofacial myofunctional disorders

These conditions involve abnormal patterns of mouth and face movement. Conditions include tongue thrusting (fronting), where individuals push out their tongue while eating or talking.

9. Spasmodic Dysphonia

This condition is a voice disorder in which spasms in the vocal cords produce speech that is hoarse, strained, or jittery.

10. Other voice disorders

These conditions can include having a voice that sounds breathy, hoarse, or scratchy. Some disorders deal with vocal folds closing when they should open (paradoxical vocal fold movement) or the presence of polyps or nodules in the vocal folds.

Speech Disorders vs. Language Disorders

Speech disorders deal with difficulty in creating sounds due to articulation, fluency, phonology, and voice problems. These problems are typically related to physical, motor, sensory, neurological, or mental health issues.

Language disorders, on the other hand, occur when individuals have difficulty communicating the meaning of what they want to express. Common in children, these disorders may result in low vocabulary and difficulty saying complex sentences. Such a disorder may reflect difficulty in comprehending school lessons or adopting new words, or it may be related to a learning disability such as dyslexia. Language disorders can also involve receptive language difficulties, where individuals have trouble understanding the messages that others are trying to convey.

Resources on Types of Speech Disorders

The following resources may provide additional information on the types of speech impediments.

Common Speech Disorders: A guide to the most common speech impediments from GreatSpeech

Speech impairment in adults: Descriptions of common adult speech issues from MedlinePlus

Stuttering Facts: Information on stuttering indications and causes from the Stuttering Foundation

Speech disorders may be caused by a variety of factors related to physical features, neurological ailments, or mental health conditions. In children, they may be related to developmental issues or unknown causes and may go away naturally over time.

Physical and neurological issues. Speech impediment causes related to physical characteristics may include:

- Brain damage

- Nervous system damage

- Respiratory system damage

- Hearing difficulties

- Cancerous or noncancerous growths

- Muscle and bone problems such as dental issues or cleft palate

Mental health issues. Some speech disorders are related to clinical conditions such as:

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Down syndrome or other genetic syndromes

- Cerebral palsy or other neurological disorders

- Multiple sclerosis

Some speech impairments may also have to do with family history, such as when parents or siblings have experienced language or speech difficulties. Other causes may include premature birth, pregnancy complications, or delivery difficulties. Voice overuse and chronic coughs can also cause speech issues.

The most common way that speech disorders are treated involves seeking professional help. If patients and families feel that symptoms warrant therapy, health professionals can help determine how to fix a speech impediment. Early treatment is best to curb speech disorders, but impairments can also be treated later in life.

Professionals in the speech therapy field include speech-language pathologists (SLPs) . These practitioners assess, diagnose, and treat communication disorders including speech, language, social, cognitive, and swallowing disorders in both adults and children. They may have an SLP assistant to help with diagnostic and therapy activities.

Speech-language pathologists may also share a practice with audiologists and audiology assistants. Audiologists help identify and treat hearing, balance, and other auditory disorders.

How Are Speech Disorders Diagnosed?

Typically, a pediatrician, social worker, teacher, or other concerned party will recognize the symptoms of a speech disorder in children. These individuals, who frequently deal with speech and language conditions and are more familiar with symptoms, will recommend that parents have their child evaluated. Adults who struggle with speech problems may seek direct guidance from a physician or speech evaluation specialist.

When evaluating a patient for a potential speech impediment, a physician will:

- Conduct hearing and vision tests

- Evaluate patient records

- Observe patient symptoms

A speech-language pathologist will conduct an initial screening that might include:

- An evaluation of speech sounds in words and sentences

- An evaluation of oral motor function

- An orofacial examination

- An assessment of language comprehension

The initial screening might result in no action if speech symptoms are determined to be developmentally appropriate. If a disorder is suspected, the initial screening might result in a referral for a comprehensive speech sound assessment, comprehensive language assessment, audiology evaluation, or other medical services.

Initial assessments and more in-depth screenings might occur in a private speech therapy practice, rehabilitation center, school, childcare program, or early intervention center. For older adults, skilled nursing centers and nursing homes may assess patients for speech, hearing, and language disorders.

How Are Speech Impediments Treated?

Once an evaluation determines precisely what type of speech sound disorder is present, patients can begin treatment. Speech-language pathologists use a combination of therapy, exercise, and assistive devices to treat speech disorders.

Speech therapy might focus on motor production (articulation) or linguistic (phonological or language-based) elements of speech, according to ASHA. There are various types of speech therapy available to patients.

Contextual Utilization — This therapeutic approach teaches methods for producing sounds consistently in different syllable-based contexts, such as phonemic or phonetic contexts. These methods are helpful for patients who produce sounds inconsistently.

Phonological Contrast — This approach focuses on improving speech through emphasis of phonemic contrasts that serve to differentiate words. Examples might include minimal opposition words (pot vs. spot) or maximal oppositions (mall vs. call). These therapy methods can help patients who use phonological error patterns.

Distinctive Feature — In this category of therapy, SLPs focus on elements that are missing in speech, such as articulation or nasality. This helps patients who substitute sounds by teaching them to distinguish target sounds from substituted sounds.

Core Vocabulary — This therapeutic approach involves practicing whole words that are commonly used in a specific patient’s communications. It is effective for patients with inconsistent sound production.

Metaphon — In this type of therapy, patients are taught to identify phonological language structures. The technique focuses on contrasting sound elements, such as loud vs. quiet, and helps patients with unintelligible speech issues.

Oral-Motor — This approach uses non-speech exercises to supplement sound therapies. This helps patients gain oral-motor strength and control to improve articulation.

Other methods professionals may use to help fix speech impediments include relaxation, breathing, muscle strengthening, and voice exercises. They may also recommend assistive devices, which may include:

- Radio transmission systems

- Personal amplifiers

- Picture boards

- Touch screens

- Text displays

- Speech-generating devices

- Hearing aids

- Cochlear implants

Resources for Professionals on How to Fix a Speech Impediment

The following resources provide information for speech therapists and other health professionals.

Assistive Devices: Information on hearing and speech aids from the NIDCD

Information for Audiologists: Publications, news, and practice aids for audiologists from ASHA

Information for Speech-Language Pathologists: Publications, news, and practice aids for SLPs from ASHA

Speech Disorder Tips for Families

For parents who are concerned that their child might have a speech disorder — or who want to prevent the development of a disorder — there are a number of activities that can help. The following are tasks that parents can engage in on a regular basis to develop literacy and speech skills.

- Introducing new vocabulary words

- Reading picture and story books with various sounds and patterns

- Talking to children about objects and events

- Answering children’s questions during routine activities

- Encouraging drawing and scribbling

- Pointing to words while reading books

- Pointing out words and sentences in objects and signs

Parents can take the following steps to make sure that potential speech impediments are identified early on.

- Discussing concerns with physicians

- Asking for hearing, vision, and speech screenings from doctors

- Requesting special education assessments from school officials

- Requesting a referral to a speech-language pathologist, audiologist, or other specialist

When a child is engaged in speech therapy, speech-language pathologists will typically establish collaborative relationships with families, sharing information and encouraging parents to participate in therapy decisions and practices.

SLPs will work with patients and their families to set goals for therapy outcomes. In addition to therapy sessions, they may develop activities and exercises for families to work on at home. It is important that caregivers are encouraging and patient with children during therapy.

Resources for Parents on How to Fix a Speech Impediment

The following resources provide additional information on treatment options for speech disorders.

Speech, Language, and Swallowing Disorders Groups: Listing of self-help groups from ASHA

ProFind: Search tool for finding certified SLPs and audiologists from ASHA

Baby’s Hearing and Communication Development Checklist: Listing of milestones that children should meet by certain ages from the NIDCD

If identified during childhood, speech disorders can be corrected efficiently, giving children greater communication opportunities. If left untreated, speech impediments can cause a variety of problems in adulthood, and may be more difficult to diagnose and treat.

Parents, teachers, doctors, speech and language professionals, and other concerned parties all have unique responsibilities in recognizing and treating speech disorders. Through professional therapy, family engagement, positive encouragement and a strong support network, individuals with speech impediments can overcome their challenges and develop essential communication skills.

Additional Sources

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Speech Sound Disorders

Identify the Signs, Signs of Speech and Language Disorders

Intermountain Healthcare, Phonological Disorders

MedlinePlus, Speech disorders – children

National Institutes of Health, National Institutes on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, “Quick Statistics About Voice, Speech, Language”

Bring us your ambition and we’ll guide you along a personalized path to a quality education that’s designed to change your life.

Take Your Next Brave Step

Receive information about the benefits of our programs, the courses you'll take, and what you need to apply.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Overcoming Speech Impediment: Symptoms to Treatment

There are many causes and solutions for impaired speech

- Types and Symptoms

- Speech Therapy

- Building Confidence

Speech impediments are conditions that can cause a variety of symptoms, such as an inability to understand language or speak with a stable sense of tone, speed, or fluidity. There are many different types of speech impediments, and they can begin during childhood or develop during adulthood.

Common causes include physical trauma, neurological disorders, or anxiety. If you or your child is experiencing signs of a speech impediment, you need to know that these conditions can be diagnosed and treated with professional speech therapy.

This article will discuss what you can do if you are concerned about a speech impediment and what you can expect during your diagnostic process and therapy.

FG Trade / Getty Images

Types and Symptoms of Speech Impediment

People can have speech problems due to developmental conditions that begin to show symptoms during early childhood or as a result of conditions that may occur during adulthood.

The main classifications of speech impairment are aphasia (difficulty understanding or producing the correct words or phrases) or dysarthria (difficulty enunciating words).

Often, speech problems can be part of neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders that also cause other symptoms, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) or autism spectrum disorder .

There are several different symptoms of speech impediments, and you may experience one or more.

Can Symptoms Worsen?

Most speech disorders cause persistent symptoms and can temporarily get worse when you are tired, anxious, or sick.

Symptoms of dysarthria can include:

- Slurred speech

- Slow speech

- Choppy speech

- Hesitant speech

- Inability to control the volume of your speech

- Shaking or tremulous speech pattern

- Inability to pronounce certain sounds

Symptoms of aphasia may involve:

- Speech apraxia (difficulty coordinating speech)

- Difficulty understanding the meaning of what other people are saying

- Inability to use the correct words

- Inability to repeat words or phases

- Speech that has an irregular rhythm

You can have one or more of these speech patterns as part of your speech impediment, and their combination and frequency will help determine the type and cause of your speech problem.

Causes of Speech Impediment

The conditions that cause speech impediments can include developmental problems that are present from birth, neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s disease , or sudden neurological events, such as a stroke .

Some people can also experience temporary speech impairment due to anxiety, intoxication, medication side effects, postictal state (the time immediately after a seizure), or a change of consciousness.

Speech Impairment in Children

Children can have speech disorders associated with neurodevelopmental problems, which can interfere with speech development. Some childhood neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders may cause a regression (backsliding) of speech skills.

Common causes of childhood speech impediments include:

- Autism spectrum disorder : A neurodevelopmental disorder that affects social and interactive development

- Cerebral palsy : A congenital (from birth) disorder that affects learning and control of physical movement

- Hearing loss : Can affect the way children hear and imitate speech

- Rett syndrome : A genetic neurodevelopmental condition that causes regression of physical and social skills beginning during the early school-age years.

- Adrenoleukodystrophy : A genetic disorder that causes a decline in motor and cognitive skills beginning during early childhood

- Childhood metabolic disorders : A group of conditions that affects the way children break down nutrients, often resulting in toxic damage to organs

- Brain tumor : A growth that may damage areas of the brain, including those that control speech or language

- Encephalitis : Brain inflammation or infection that may affect the way regions in the brain function

- Hydrocephalus : Excess fluid within the skull, which may develop after brain surgery and can cause brain damage

Do Childhood Speech Disorders Persist?

Speech disorders during childhood can have persistent effects throughout life. Therapy can often help improve speech skills.

Speech Impairment in Adulthood

Adult speech disorders develop due to conditions that damage the speech areas of the brain.

Common causes of adult speech impairment include:

- Head trauma

- Nerve injury

- Throat tumor

- Stroke

- Parkinson’s disease

- Essential tremor

- Brain tumor

- Brain infection

Additionally, people may develop changes in speech with advancing age, even without a specific neurological cause. This can happen due to presbyphonia , which is a change in the volume and control of speech due to declining hormone levels and reduced elasticity and movement of the vocal cords.

Do Speech Disorders Resolve on Their Own?

Children and adults who have persistent speech disorders are unlikely to experience spontaneous improvement without therapy and should seek professional attention.

Steps to Treating Speech Impediment

If you or your child has a speech impediment, your healthcare providers will work to diagnose the type of speech impediment as well as the underlying condition that caused it. Defining the cause and type of speech impediment will help determine your prognosis and treatment plan.

Sometimes the cause is known before symptoms begin, as is the case with trauma or MS. Impaired speech may first be a symptom of a condition, such as a stroke that causes aphasia as the primary symptom.

The diagnosis will include a comprehensive medical history, physical examination, and a thorough evaluation of speech and language. Diagnostic testing is directed by the medical history and clinical evaluation.

Diagnostic testing may include:

- Brain imaging , such as brain computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic residence imaging (MRI), if there’s concern about a disease process in the brain

- Swallowing evaluation if there’s concern about dysfunction of the muscles in the throat

- Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (aka nerve conduction velocity, or NCV) if there’s concern about nerve and muscle damage

- Blood tests, which can help in diagnosing inflammatory disorders or infections

Your diagnostic tests will help pinpoint the cause of your speech problem. Your treatment will include specific therapy to help improve your speech, as well as medication or other interventions to treat the underlying disorder.

For example, if you are diagnosed with MS, you would likely receive disease-modifying therapy to help prevent MS progression. And if you are diagnosed with a brain tumor, you may need surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation to treat the tumor.

Therapy to Address Speech Impediment

Therapy for speech impairment is interactive and directed by a specialist who is experienced in treating speech problems . Sometimes, children receive speech therapy as part of a specialized learning program at school.

The duration and frequency of your speech therapy program depend on the underlying cause of your impediment, your improvement, and approval from your health insurance.

If you or your child has a serious speech problem, you may qualify for speech therapy. Working with your therapist can help you build confidence, particularly as you begin to see improvement.

Exercises during speech therapy may include:

- Pronouncing individual sounds, such as la la la or da da da

- Practicing pronunciation of words that you have trouble pronouncing

- Adjusting the rate or volume of your speech

- Mouth exercises

- Practicing language skills by naming objects or repeating what the therapist is saying

These therapies are meant to help achieve more fluent and understandable speech as well as an increased comfort level with speech and language.

Building Confidence With Speech Problems

Some types of speech impairment might not qualify for therapy. If you have speech difficulties due to anxiety or a social phobia or if you don’t have access to therapy, you might benefit from activities that can help you practice your speech.

You might consider one or more of the following for you or your child:

- Joining a local theater group

- Volunteering in a school or community activity that involves interaction with the public

- Signing up for a class that requires a significant amount of class participation

- Joining a support group for people who have problems with speech

Activities that you do on your own to improve your confidence with speaking can be most beneficial when you are in a non-judgmental and safe space.

Many different types of speech problems can affect children and adults. Some of these are congenital (present from birth), while others are acquired due to health conditions, medication side effects, substances, or mood and anxiety disorders. Because there are so many different types of speech problems, seeking a medical diagnosis so you can get the right therapy for your specific disorder is crucial.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Language and speech disorders in children .

Han C, Tang J, Tang B, et al. The effectiveness and safety of noninvasive brain stimulation technology combined with speech training on aphasia after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(2):e36880. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000036880

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick statistics about voice, speech, language .

Mackey J, McCulloch H, Scheiner G, et al. Speech pathologists' perspectives on the use of augmentative and alternative communication devices with people with acquired brain injury and reflections from lived experience . Brain Impair. 2023;24(2):168-184. doi:10.1017/BrImp.2023.9

Allison KM, Doherty KM. Relation of speech-language profile and communication modality to participation of children with cerebral palsy . Am J Speech Lang Pathol . 2024:1-11. doi:10.1044/2023_AJSLP-23-00267

Saccente-Kennedy B, Gillies F, Desjardins M, et al. A systematic review of speech-language pathology interventions for presbyphonia using the rehabilitation treatment specification system . J Voice. 2024:S0892-1997(23)00396-X. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2023.12.010

By Heidi Moawad, MD Dr. Moawad is a neurologist and expert in brain health. She regularly writes and edits health content for medical books and publications.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Types of Speech Impediments

Phynart Studio / Getty Images

Articulation Errors

Ankyloglossia, treating speech disorders.

A speech impediment, also known as a speech disorder , is a condition that can affect a person’s ability to form sounds and words, making their speech difficult to understand.

Speech disorders generally become evident in early childhood, as children start speaking and learning language. While many children initially have trouble with certain sounds and words, most are able to speak easily by the time they are five years old. However, some speech disorders persist. Approximately 5% of children aged three to 17 in the United States experience speech disorders.

There are many different types of speech impediments, including:

- Articulation errors

This article explores the causes, symptoms, and treatment of the different types of speech disorders.

Speech impediments that break the flow of speech are known as disfluencies. Stuttering is the most common form of disfluency, however there are other types as well.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Disfluencies

These are some of the characteristics of disfluencies:

- Repeating certain phrases, words, or sounds after the age of 4 (For example: “O…orange,” “I like…like orange juice,” “I want…I want orange juice”)

- Adding in extra sounds or words into sentences (For example: “We…uh…went to buy…um…orange juice”)

- Elongating words (For example: Saying “orange joooose” instead of "orange juice")

- Replacing words (For example: “What…Where is the orange juice?”)

- Hesitating while speaking (For example: A long pause while thinking)

- Pausing mid-speech (For example: Stopping abruptly mid-speech, due to lack of airflow, causing no sounds to come out, leading to a tense pause)

In addition, someone with disfluencies may also experience the following symptoms while speaking:

- Vocal tension and strain

- Head jerking

- Eye blinking

- Lip trembling

Causes of Disfluencies

People with disfluencies tend to have neurological differences in areas of the brain that control language processing and coordinate speech, which may be caused by:

- Genetic factors

- Trauma or infection to the brain

- Environmental stressors that cause anxiety or emotional distress

- Neurodevelopmental conditions like attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Articulation disorders occur when a person has trouble placing their tongue in the correct position to form certain speech sounds. Lisping is the most common type of articulation disorder.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Articulation Errors

These are some of the characteristics of articulation disorders:

- Substituting one sound for another . People typically have trouble with ‘r’ and ‘l’ sounds. (For example: Being unable to say “rabbit” and saying “wabbit” instead)

- Lisping , which refers specifically to difficulty with ‘s’ and ‘z’ sounds. (For example: Saying “thugar” instead of “sugar” or producing a whistling sound while trying to pronounce these letters)

- Omitting sounds (For example: Saying “coo” instead of “school”)

- Adding sounds (For example: Saying “pinanio” instead of “piano”)

- Making other speech errors that can make it difficult to decipher what the person is saying. For instance, only family members may be able to understand what they’re trying to say.

Causes of Articulation Errors

Articulation errors may be caused by:

- Genetic factors, as it can run in families

- Hearing loss , as mishearing sounds can affect the person’s ability to reproduce the sound

- Changes in the bones or muscles that are needed for speech, including a cleft palate (a hole in the roof of the mouth) and tooth problems

- Damage to the nerves or parts of the brain that coordinate speech, caused by conditions such as cerebral palsy , for instance

Ankyloglossia, also known as tongue-tie, is a condition where the person’s tongue is attached to the bottom of their mouth. This can restrict the tongue’s movement and make it hard for the person to move their tongue.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Ankyloglossia

Ankyloglossia is characterized by difficulty pronouncing ‘d,’ ‘n,’ ‘s,’ ‘t,’ ‘th,’ and ‘z’ sounds that require the person’s tongue to touch the roof of their mouth or their upper teeth, as their tongue may not be able to reach there.

Apart from speech impediments, people with ankyloglossia may also experience other symptoms as a result of their tongue-tie. These symptoms include:

- Difficulty breastfeeding in newborns

- Trouble swallowing

- Limited ability to move the tongue from side to side or stick it out

- Difficulty with activities like playing wind instruments, licking ice cream, or kissing

- Mouth breathing

Causes of Ankyloglossia

Ankyloglossia is a congenital condition, which means it is present from birth. A tissue known as the lingual frenulum attaches the tongue to the base of the mouth. People with ankyloglossia have a shorter lingual frenulum, or it is attached further along their tongue than most people’s.

Dysarthria is a condition where people slur their words because they cannot control the muscles that are required for speech, due to brain, nerve, or organ damage.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Dysarthria

Dysarthria is characterized by:

- Slurred, choppy, or robotic speech

- Rapid, slow, or soft speech

- Breathy, hoarse, or nasal voice

Additionally, someone with dysarthria may also have other symptoms such as difficulty swallowing and inability to move their tongue, lips, or jaw easily.

Causes of Dysarthria

Dysarthria is caused by paralysis or weakness of the speech muscles. The causes of the weakness can vary depending on the type of dysarthria the person has:

- Central dysarthria is caused by brain damage. It may be the result of neuromuscular diseases, such as cerebral palsy, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. Central dysarthria may also be caused by injuries or illnesses that damage the brain, such as dementia, stroke, brain tumor, or traumatic brain injury .

- Peripheral dysarthria is caused by damage to the organs involved in speech. It may be caused by congenital structural problems, trauma to the mouth or face, or surgery to the tongue, mouth, head, neck, or voice box.

Apraxia, also known as dyspraxia, verbal apraxia, or apraxia of speech, is a neurological condition that can cause a person to have trouble moving the muscles they need to create sounds or words. The person’s brain knows what they want to say, but is unable to plan and sequence the words accordingly.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Apraxia

These are some of the characteristics of apraxia:

- Distorting sounds: The person may have trouble pronouncing certain sounds, particularly vowels, because they may be unable to move their tongue or jaw in the manner required to produce the right sound. Longer or more complex words may be especially harder to manage.

- Being inconsistent in their speech: For instance, the person may be able to pronounce a word correctly once, but may not be able to repeat it. Or, they may pronounce it correctly today and differently on another day.

- Grasping for words: The person may appear to be searching for the right word or sound, or attempt the pronunciation several times before getting it right.

- Making errors with the rhythm or tone of speech: The person may struggle with using tone and inflection to communicate meaning. For instance, they may not stress any of the words in a sentence, have trouble going from one syllable in a word to another, or pause at an inappropriate part of a sentence.

Causes of Apraxia

Apraxia occurs when nerve pathways in the brain are interrupted, which can make it difficult for the brain to send messages to the organs involved in speaking. The causes of these neurological disturbances can vary depending on the type of apraxia the person has:

- Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS): This condition is present from birth and is often hereditary. A person may be more likely to have it if a biological relative has a learning disability or communication disorder.

- Acquired apraxia of speech (AOS): This condition can occur in adults, due to brain damage as a result of a tumor, head injury , stroke, or other illness that affects the parts of the brain involved in speech.

If you have a speech impediment, or suspect your child might have one, it can be helpful to visit your healthcare provider. Your primary care physician can refer you to a speech-language pathologist, who can evaluate speech, diagnose speech disorders, and recommend treatment options.

The diagnostic process may involve a physical examination as well as psychological, neurological, or hearing tests, in order to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other causes.

Treatment for speech disorders often involves speech therapy, which can help you learn how to move your muscles and position your tongue correctly in order to create specific sounds. It can be quite effective in improving your speech.

Children often grow out of milder speech disorders; however, special education and speech therapy can help with more serious ones.

For ankyloglossia, or tongue-tie, a minor surgery known as a frenectomy can help detach the tongue from the bottom of the mouth.

A Word From Verywell

A speech impediment can make it difficult to pronounce certain sounds, speak clearly, or communicate fluently.

Living with a speech disorder can be frustrating because people may cut you off while you’re speaking, try to finish your sentences, or treat you differently. It can be helpful to talk to your healthcare providers about how to cope with these situations.

You may also benefit from joining a support group, where you can connect with others living with speech disorders.

National Library of Medicine. Speech disorders . Medline Plus.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Language and speech disorders .

Cincinnati Children's Hospital. Stuttering .

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick statistics about voice, speech, and language .

Cleveland Clinic. Speech impediment .

Lee H, Sim H, Lee E, Choi D. Disfluency characteristics of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms . J Commun Disord . 2017;65:54-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.12.001

Nemours Foundation. Speech problems .

Penn Medicine. Speech and language disorders .

Cleveland Clinic. Tongue-tie .

University of Rochester Medical Center. Ankyloglossia .

Cleveland Clinic. Dysarthria .

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Apraxia of speech .

Cleveland Clinic. Childhood apraxia of speech .

Stanford Children’s Hospital. Speech sound disorders in children .

Abbastabar H, Alizadeh A, Darparesh M, Mohseni S, Roozbeh N. Spatial distribution and the prevalence of speech disorders in the provinces of Iran . J Med Life . 2015;8(Spec Iss 2):99-104.

By Sanjana Gupta Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

- Children's Health

- Common Symptoms

- Common Conditions

- Chronic Conditions

- View Full Guide

Common Speech and Language Disorders

Speech and language problems may make it hard for your child to understand and speak with others, or make the sounds of speech. They're common, affecting as many as one in 12 kids and teens in the U.S.

Kids with these disorders often have trouble when they learn to read and write, or when they try to be social and make friends. But treatment helps most children improve, especially if they start it early.

Adults can also have these disorders. It may have started in childhood, or they may have them because of other problems such as brain injuries, stroke , cancer , or dementia .

Speech Disorders

For children with speech disorders, it can be tough forming the sounds that make up speech or putting sentences together. Signs of a speech disorder include:

- Trouble with p, b, m, h, and w sounds at 1 to 2 years of age

- Problems with k, g, f, t, d, and n sounds between the ages of 2 and 3

- When people who know the child well find it hard to understand them

The causes of most speech disorders are unknown.

There are three major types:

Articulation: It’s hard for your child to pronounce words. They may drop sounds or use the wrong sounds and say things like “wabbit” instead of “rabbit.” Letters such as p, b, and m are easier to learn. Most kids can master those sounds by age 2. But r, l, and th sounds take longer to get right.

Fluency: Your child may have problems with how their words and sentences flow. Stuttering is a fluency disorder. That’s when your child repeats words, parts of words, or uses odd pauses. It’s common as kids approach 3 years of age. That’s when a child thinks faster than they can speak. If it lasts longer than 6 months, or if your child is more than 3.5 years old, get help.

Voice: If your child speaks too loudly, too softly, or is often hoarse, they may have a voice disorder. This can happen if your child speaks loudly and with too much force. Another cause is small growths on the vocal cords called nodules or polyps. They’re also due to too much voice stress.

Language Disorders

Does your child use fewer words and simpler sentences than their friends? These issues may be signs of a language disorder. For kids with this disorder, it’s hard to find the right words or speak in complete sentences. It may be tough for them to make sense of what others say. Your child may have this disorder if they:

- Don’t babble by 7 months

- Only speak a few words by 17 months

- Can’t put two words together by 2 years

- Have problems when they play and talk with other kids from the ages of 2 to 3

There are two major types of language disorders. It’s possible for a child to have both.

Receptive: This is when your child finds it hard to understand speech. They may find it hard to:

- Follow directions

- Answer questions

- Point to objects when asked

Expressive : If your child has trouble finding the right words to express themselves, they may have this type of language disorder. Kids with an expressive disorder may find it tough to:

- Ask questions

- String words into sentences

- Start and continue a conversation

It’s not always possible to trace the cause of language disorders. Physical causes of this type of disorder can include head injuries , illness, or ear infections . These are sometimes called acquired language disorders.

Other things that make it more likely include:

- A family history of language problems

- Being born early

- Down syndrome

- Poor nutrition

Doctors don’t always know what causes your child’s condition. Remember, these kinds of disorders have nothing to do with how smart your child is. Often, kids with language disorders are smarter than average.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Speech and language disorders are legally defined disabilities. Your child may get testing and treatment through your state’s early intervention program or local public schools. Some services are free.

Your child may see a speech language pathologist, or SLP. The SLP may try to find out if your child:

- Can follow directions

- Is able to name common objects

- Knows how to play with toys

- Can hold books the right way

The SLP will first check your child’s hearing. If that’s OK, the SLP will do tests to find out what kind of disorder may be present, if it’s a short-term problem or one that needs treatment, and what treatment plan to recommend.

How to Help Your Child

Children learn and grow at their own pace. The younger they are, the more likely they are to make mistakes. So you’ll want to learn the milestones. Know what skills your child should be able to master at a given age.

To help your child with their speech and language skills:

- Talk to your child, even as a newborn .

- Point to objects and name them.

- When your child is ready, ask them questions.

- Respond to what they say, but don’t correct mistakes.

- Read to your child at least 15 minutes a day.

If your child has one of these disorders, don’t assume they’ll outgrow it. But treatment does help most kids get better. The sooner they get it, the better the results.

Top doctors in ,

Find more top doctors on, related links.

- Children's Health News

- Children's Health Reference

- Children's Health Slideshows

- Children's Health Quizzes

- Children's Health Videos

- Find a Pediatrician

- ADHD in Children

- Baby Development

- BMI Calculator for Parents

- Children's Vaccines

- Kids' Dental Care

- Newborn & Baby

- Teen Health

- More Related Topics

10 Most Common Speech-Language Disorders & Impediments

As you get to know more about the field of speech-language pathology you’ll increasingly realize why SLPs are required to earn at least a master’s degree . This stuff is serious – and there’s nothing easy about it.

In 2016 the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders reported that 7.7% of American children have been diagnosed with a speech or swallowing disorder. That comes out to nearly one in 12 children, and gets even bigger if you factor in adults.

Whether rooted in psycho-speech behavioral issues, muscular disorders, or brain damage, nearly all the diagnoses SLPs make fall within just 10 common categories…

Types of Speech Disorders & Impediments

Apraxia of speech (aos).

Apraxia of Speech (AOS) happens when the neural pathway between the brain and a person’s speech function (speech muscles) is lost or obscured. The person knows what they want to say – they can even write what they want to say on paper – however the brain is unable to send the correct messages so that speech muscles can articulate what they want to say, even though the speech muscles themselves work just fine. Many SLPs specialize in the treatment of Apraxia .

There are different levels of severity of AOS, ranging from mostly functional, to speech that is incoherent. And right now we know for certain it can be caused by brain damage, such as in an adult who has a stroke. This is called Acquired AOS.

However the scientific and medical community has been unable to detect brain damage – or even differences – in children who are born with this disorder, making the causes of Childhood AOS somewhat of a mystery. There is often a correlation present, with close family members suffering from learning or communication disorders, suggesting there may be a genetic link.

Mild cases might be harder to diagnose, especially in children where multiple unknown speech disorders may be present. Symptoms of mild forms of AOS are shared by a range of different speech disorders, and include mispronunciation of words and irregularities in tone, rhythm, or emphasis (prosody).

Stuttering – Stammering

Stuttering, also referred to as stammering, is so common that everyone knows what it sounds like and can easily recognize it. Everyone has probably had moments of stuttering at least once in their life. The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders estimates that three million Americans stutter, and reports that of the up-to-10-percent of children who do stutter, three-quarters of them will outgrow it. It should not be confused with cluttering.

Most people don’t know that stuttering can also include non-verbal involuntary or semi-voluntary actions like blinking or abdominal tensing (tics). Speech language pathologists are trained to look for all the symptoms of stuttering , especially the non-verbal ones, and that is why an SLP is qualified to make a stuttering diagnosis.

The earliest this fluency disorder can become apparent is when a child is learning to talk. It may also surface later during childhood. Rarely if ever has it developed in adults, although many adults have kept a stutter from childhood.

Stuttering only becomes a problem when it has an impact on daily activities, or when it causes concern to parents or the child suffering from it. In some people, a stutter is triggered by certain events like talking on the phone. When people start to avoid specific activities so as not to trigger their stutter, this is a sure sign that the stutter has reached the level of a speech disorder.

The causes of stuttering are mostly a mystery. There is a correlation with family history indicating a genetic link. Another theory is that a stutter is a form of involuntary or semi-voluntary tic. Most studies of stuttering agree there are many factors involved.

Dysarthria is a symptom of nerve or muscle damage. It manifests itself as slurred speech, slowed speech, limited tongue, jaw, or lip movement, abnormal rhythm and pitch when speaking, changes in voice quality, difficulty articulating, labored speech, and other related symptoms.

It is caused by muscle damage, or nerve damage to the muscles involved in the process of speaking such as the diaphragm, lips, tongue, and vocal chords.

Because it is a symptom of nerve and/or muscle damage it can be caused by a wide range of phenomena that affect people of all ages. This can start during development in the womb or shortly after birth as a result of conditions like muscular dystrophy and cerebral palsy. In adults some of the most common causes of dysarthria are stroke, tumors, and MS.

A lay term, lisping can be recognized by anyone and is very common.

Speech language pathologists provide an extra level of expertise when treating patients with lisping disorders . They can make sure that a lisp is not being confused with another type of disorder such as apraxia, aphasia, impaired development of expressive language, or a speech impediment caused by hearing loss.

SLPs are also important in distinguishing between the five different types of lisps. Most laypersons can usually pick out the most common type, the interdental/dentalised lisp. This is when a speaker makes a “th” sound when trying to make the “s” sound. It is caused by the tongue reaching past or touching the front teeth.

Because lisps are functional speech disorders, SLPs can play a huge role in correcting these with results often being a complete elimination of the lisp. Treatment is particularly effective when implemented early, although adults can also benefit.

Experts recommend professional SLP intervention if a child has reached the age of four and still has an interdental/dentalised lisp. SLP intervention is recommended as soon as possible for all other types of lisps. Treatment includes pronunciation and annunciation coaching, re-teaching how a sound or word is supposed to be pronounced, practice in front of a mirror, and speech-muscle strengthening that can be as simple as drinking out of a straw.

Spasmodic Dysphonia

Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) is a chronic long-term disorder that affects the voice. It is characterized by a spasming of the vocal chords when a person attempts to speak and results in a voice that can be described as shaky, hoarse, groaning, tight, or jittery. It can cause the emphasis of speech to vary considerably. Many SLPs specialize in the treatment of Spasmodic Dysphonia .

SLPs will most often encounter this disorder in adults, with the first symptoms usually occurring between the ages of 30 and 50. It can be caused by a range of things mostly related to aging, such as nervous system changes and muscle tone disorders.

It’s difficult to isolate vocal chord spasms as being responsible for a shaky or trembly voice, so diagnosing SD is a team effort for SLPs that also involves an ear, nose, and throat doctor (otolaryngologist) and a neurologist.

Have you ever heard people talking about how they are smart but also nervous in large groups of people, and then self-diagnose themselves as having Asperger’s? You might have heard a similar lay diagnosis for cluttering. This is an indication of how common this disorder is as well as how crucial SLPs are in making a proper cluttering diagnosis .

A fluency disorder, cluttering is characterized by a person’s speech being too rapid, too jerky, or both. To qualify as cluttering, the person’s speech must also have excessive amounts of “well,” “um,” “like,” “hmm,” or “so,” (speech disfluencies), an excessive exclusion or collapsing of syllables, or abnormal syllable stresses or rhythms.

The first symptoms of this disorder appear in childhood. Like other fluency disorders, SLPs can have a huge impact on improving or eliminating cluttering. Intervention is most effective early on in life, however adults can also benefit from working with an SLP.

Muteness – Selective Mutism

There are different kinds of mutism, and here we are talking about selective mutism. This used to be called elective mutism to emphasize its difference from disorders that caused mutism through damage to, or irregularities in, the speech process.

Selective mutism is when a person does not speak in some or most situations, however that person is physically capable of speaking. It most often occurs in children, and is commonly exemplified by a child speaking at home but not at school.

Selective mutism is related to psychology. It appears in children who are very shy, who have an anxiety disorder, or who are going through a period of social withdrawal or isolation. These psychological factors have their own origins and should be dealt with through counseling or another type of psychological intervention.

Diagnosing selective mutism involves a team of professionals including SLPs, pediatricians, psychologists, and psychiatrists. SLPs play an important role in this process because there are speech language disorders that can have the same effect as selective muteness – stuttering, aphasia, apraxia of speech, or dysarthria – and it’s important to eliminate these as possibilities.

And just because selective mutism is primarily a psychological phenomenon, that doesn’t mean SLPs can’t do anything. Quite the contrary.

The National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke estimates that one million Americans have some form of aphasia.

Aphasia is a communication disorder caused by damage to the brain’s language capabilities. Aphasia differs from apraxia of speech and dysarthria in that it solely pertains to the brain’s speech and language center.

As such anyone can suffer from aphasia because brain damage can be caused by a number of factors. However SLPs are most likely to encounter aphasia in adults, especially those who have had a stroke. Other common causes of aphasia are brain tumors, traumatic brain injuries, and degenerative brain diseases.

In addition to neurologists, speech language pathologists have an important role in diagnosing aphasia. As an SLP you’ll assess factors such as a person’s reading and writing, functional communication, auditory comprehension, and verbal expression.

Speech Delay – Alalia

A speech delay, known to professionals as alalia, refers to the phenomenon when a child is not making normal attempts to verbally communicate. There can be a number of factors causing this to happen, and that’s why it’s critical for a speech language pathologist to be involved.

The are many potential reasons why a child would not be using age-appropriate communication. These can range anywhere from the child being a “late bloomer” – the child just takes a bit longer than average to speak – to the child having brain damage. It is the role of an SLP to go through a process of elimination, evaluating each possibility that could cause a speech delay, until an explanation is found.

Approaching a child with a speech delay starts by distinguishing among the two main categories an SLP will evaluate: speech and language.

Speech has a lot to do with the organs of speech – the tongue, mouth, and vocal chords – as well as the muscles and nerves that connect them with the brain. Disorders like apraxia of speech and dysarthria are two examples that affect the nerve connections and organs of speech. Other examples in this category could include a cleft palette or even hearing loss.

The other major category SLPs will evaluate is language. This relates more to the brain and can be affected by brain damage or developmental disorders like autism. There are many different types of brain damage that each manifest themselves differently, as well as developmental disorders, and the SLP will make evaluations for everything.

Issues Related to Autism

While the autism spectrum itself isn’t a speech disorder, it makes this list because the two go hand-in-hand more often than not.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that one out of every 68 children in our country have an autism spectrum disorder. And by definition, all children who have autism also have social communication problems.

Speech-language pathologists are often a critical voice on a team of professionals – also including pediatricians, occupational therapists, neurologists, developmental specialists, and physical therapists – who make an autism spectrum diagnosis .

In fact, the American Speech-Language Hearing Association reports that problems with communication are the first detectable signs of autism. That is why language disorders – specifically disordered verbal and nonverbal communication – are one of the primary diagnostic criteria for autism.

So what kinds of SLP disorders are you likely to encounter with someone on the autism spectrum?

A big one is apraxia of speech. A study that came out of Penn State in 2015 found that 64 percent of children who were diagnosed with autism also had childhood apraxia of speech.

This basic primer on the most common speech disorders offers little more than an interesting glimpse into the kind of issues that SLPs work with patients to resolve. But even knowing everything there is to know about communication science and speech disorders doesn’t tell the whole story of what this profession is all about. With every client in every therapy session, the goal is always to have the folks that come to you for help leave with a little more confidence than when they walked in the door that day. As a trusted SLP, you will build on those gains with every session, helping clients experience the joy and freedom that comes with the ability to express themselves freely. At the end of the day, this is what being an SLP is all about.

Ready to make a difference in speech pathology? Learn how to become a Speech-Language Pathologist today

- Emerson College - Master's in Speech-Language Pathology online - Prepare to become an SLP in as few as 20 months. No GRE required. Scholarships available.

- Arizona State University - Online - Online Bachelor of Science in Speech and Hearing Science - Designed to prepare graduates to work in behavioral health settings or transition to graduate programs in speech-language pathology and audiology.

- NYU Steinhardt - NYU Steinhardt's Master of Science in Communicative Sciences and Disorders online - ASHA-accredited. Bachelor's degree required. Graduate prepared to pursue licensure.

- Calvin University - Calvin University's Online Speech and Hearing Foundations Certificate - Helps You Gain a Strong Foundation for Your Speech-Language Pathology Career.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association

- Certification

- Publications

- Continuing Education

- Practice Management

- Audiologists

- Speech-Language Pathologists

- Academic & Faculty

- Audiology & SLP Assistants

Speech Sound Disorders-Articulation and Phonology

View All Portal Topics

See the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for summaries of the available research on this topic.

The scope of this page is speech sound disorders with no known cause—historically called articulation and phonological disorders —in preschool and school-age children (ages 3–21).

Information about speech sound problems related to motor/neurological disorders, structural abnormalities, and sensory/perceptual disorders (e.g., hearing loss) is not addressed in this page.

See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Childhood Apraxia of Speech and Cleft Lip and Palate for information about speech sound problems associated with these two disorders. A Practice Portal page on dysarthria in children will be developed in the future.

Speech Sound Disorders

Speech sound disorders is an umbrella term referring to any difficulty or combination of difficulties with perception, motor production, or phonological representation of speech sounds and speech segments—including phonotactic rules governing permissible speech sound sequences in a language.

Speech sound disorders can be organic or functional in nature. Organic speech sound disorders result from an underlying motor/neurological, structural, or sensory/perceptual cause. Functional speech sound disorders are idiopathic—they have no known cause. See figure below.

Organic Speech Sound Disorders

Organic speech sound disorders include those resulting from motor/neurological disorders (e.g., childhood apraxia of speech and dysarthria), structural abnormalities (e.g., cleft lip/palate and other structural deficits or anomalies), and sensory/perceptual disorders (e.g., hearing loss).

Functional Speech Sound Disorders

Functional speech sound disorders include those related to the motor production of speech sounds and those related to the linguistic aspects of speech production. Historically, these disorders are referred to as articulation disorders and phonological disorders , respectively. Articulation disorders focus on errors (e.g., distortions and substitutions) in production of individual speech sounds. Phonological disorders focus on predictable, rule-based errors (e.g., fronting, stopping, and final consonant deletion) that affect more than one sound. It is often difficult to cleanly differentiate between articulation and phonological disorders; therefore, many researchers and clinicians prefer to use the broader term, "speech sound disorder," when referring to speech errors of unknown cause. See Bernthal, Bankson, and Flipsen (2017) and Peña-Brooks and Hegde (2015) for relevant discussions.

This Practice Portal page focuses on functional speech sound disorders. The broad term, "speech sound disorder(s)," is used throughout; articulation error types and phonological error patterns within this diagnostic category are described as needed for clarity.

Procedures and approaches detailed in this page may also be appropriate for assessing and treating organic speech sound disorders. See Speech Characteristics: Selected Populations [PDF] for a brief summary of selected populations and characteristic speech problems.

Incidence and Prevalence

The incidence of speech sound disorders refers to the number of new cases identified in a specified period. The prevalence of speech sound disorders refers to the number of children who are living with speech problems in a given time period.

Estimated prevalence rates of speech sound disorders vary greatly due to the inconsistent classifications of the disorders and the variance of ages studied. The following data reflect the variability:

- Overall, 2.3% to 24.6% of school-aged children were estimated to have speech delay or speech sound disorders (Black, Vahratian, & Hoffman, 2015; Law, Boyle, Harris, Harkness, & Nye, 2000; Shriberg, Tomblin, & McSweeny, 1999; Wren, Miller, Peters, Emond, & Roulstone, 2016).

- A 2012 survey from the National Center for Health Statistics estimated that, among children with a communication disorder, 48.1% of 3- to 10-year old children and 24.4% of 11- to 17-year old children had speech sound problems only. Parents reported that 67.6% of children with speech problems received speech intervention services (Black et al., 2015).

- Residual or persistent speech errors were estimated to occur in 1% to 2% of older children and adults (Flipsen, 2015).

- Reports estimated that speech sound disorders are more prevalent in boys than in girls, with a ratio ranging from 1.5:1.0 to 1.8:1.0 (Shriberg et al., 1999; Wren et al., 2016).

- Prevalence rates were estimated to be 5.3% in African American children and 3.8% in White children (Shriberg et al., 1999).

- Reports estimated that 11% to 40% of children with speech sound disorders had concomitant language impairment (Eadie et al., 2015; Shriberg et al., 1999).

- Poor speech sound production skills in kindergarten children have been associated with lower literacy outcomes (Overby, Trainin, Smit, Bernthal, & Nelson, 2012). Estimates reported a greater likelihood of reading disorders (relative risk: 2.5) in children with a preschool history of speech sound disorders (Peterson, Pennington, Shriberg, & Boada, 2009).

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of functional speech sound disorders include the following:

- omissions/deletions —certain sounds are omitted or deleted (e.g., "cu" for "cup" and "poon" for "spoon")

- substitutions —one or more sounds are substituted, which may result in loss of phonemic contrast (e.g., "thing" for "sing" and "wabbit" for "rabbit")

- additions —one or more extra sounds are added or inserted into a word (e.g., "buhlack" for "black")

- distortions —sounds are altered or changed (e.g., a lateral "s")

- syllable-level errors —weak syllables are deleted (e.g., "tephone" for "telephone")

Signs and symptoms may occur as independent articulation errors or as phonological rule-based error patterns (see ASHA's resource on selected phonological processes [patterns] for examples). In addition to these common rule-based error patterns, idiosyncratic error patterns can also occur. For example, a child might substitute many sounds with a favorite or default sound, resulting in a considerable number of homonyms (e.g., shore, sore, chore, and tore might all be pronounced as door ; Grunwell, 1987; Williams, 2003a).

Influence of Accent

An accent is the unique way that speech is pronounced by a group of people speaking the same language and is a natural part of spoken language. Accents may be regional; for example, someone from New York may sound different than someone from South Carolina. Foreign accents occur when a set of phonetic traits of one language are carried over when a person learns a new language. The first language acquired by a bilingual or multilingual individual can influence the pronunciation of speech sounds and the acquisition of phonotactic rules in subsequently acquired languages. No accent is "better" than another. Accents, like dialects, are not speech or language disorders but, rather, only reflect differences. See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology and Cultural Responsiveness .

Influence of Dialect

Not all sound substitutions and omissions are speech errors. Instead, they may be related to a feature of a speaker's dialect (a rule-governed language system that reflects the regional and social background of its speakers). Dialectal variations of a language may cross all linguistic parameters, including phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. An example of a dialectal variation in phonology occurs with speakers of African American English (AAE) when a "d" sound is used for a "th" sound (e.g., "dis" for "this"). This variation is not evidence of a speech sound disorder but, rather, one of the phonological features of AAE.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) must distinguish between dialectal differences and communicative disorders and must

- recognize all dialects as being rule-governed linguistic systems;

- understand the rules and linguistic features of dialects represented by their clientele; and

- be familiar with nondiscriminatory testing and dynamic assessment procedures, such as identifying potential sources of test bias, administering and scoring standardized tests using alternative methods, and analyzing test results in light of existing information regarding dialect use (see, e.g., McLeod, Verdon, & The International Expert Panel on Multilingual Children's Speech, 2017).

See ASHA's Practice Portal pages on Multilingual Service Delivery in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology and Cultural Responsiveness .

The cause of functional speech sound disorders is not known; however, some risk factors have been investigated.

Frequently reported risk factors include the following:

- Gender —the incidence of speech sound disorders is higher in males than in females (e.g., Everhart, 1960; Morley, 1952; Shriberg et al., 1999).

- Pre- and perinatal problems —factors such as maternal stress or infections during pregnancy, complications during delivery, preterm delivery, and low birthweight were found to be associated with delay in speech sound acquisition and with speech sound disorders (e.g., Byers Brown, Bendersky, & Chapman, 1986; Fox, Dodd, & Howard, 2002).

- Family history —children who have family members (parents or siblings) with speech and/or language difficulties were more likely to have a speech disorder (e.g., Campbell et al., 2003; Felsenfeld, McGue, & Broen, 1995; Fox et al., 2002; Shriberg & Kwiatkowski, 1994).

- Persistent otitis media with effusion —persistent otitis media with effusion (often associated with hearing loss) has been associated with impaired speech development (Fox et al., 2002; Silva, Chalmers, & Stewart, 1986; Teele, Klein, Chase, Menyuk, & Rosner, 1990).

Roles and Responsibilities

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) play a central role in the screening, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of persons with speech sound disorders. The professional roles and activities in speech-language pathology include clinical/educational services (diagnosis, assessment, planning, and treatment); prevention and advocacy; and education, administration, and research. See ASHA's Scope of Practice in Speech-Language Pathology (ASHA, 2016).

Appropriate roles for SLPs include the following:

- Providing prevention information to individuals and groups known to be at risk for speech sound disorders, as well as to individuals working with those at risk

- Educating other professionals on the needs of persons with speech sound disorders and the role of SLPs in diagnosing and managing speech sound disorders

- Screening individuals who present with speech sound difficulties and determining the need for further assessment and/or referral for other services

- Recognizing that students with speech sound disorders have heightened risks for later language and literacy problems

- Conducting a culturally and linguistically relevant comprehensive assessment of speech, language, and communication

- Taking into consideration the rules of a spoken accent or dialect, typical dual-language acquisition from birth, and sequential second-language acquisition to distinguish difference from disorder

- Diagnosing the presence or absence of a speech sound disorder

- Referring to and collaborating with other professionals to rule out other conditions, determine etiology, and facilitate access to comprehensive services

- Making decisions about the management of speech sound disorders

- Making decisions about eligibility for services, based on the presence of a speech sound disorder

- Developing treatment plans, providing intervention and support services, documenting progress, and determining appropriate service delivery approaches and dismissal criteria

- Counseling persons with speech sound disorders and their families/caregivers regarding communication-related issues and providing education aimed at preventing further complications related to speech sound disorders

- Serving as an integral member of an interdisciplinary team working with individuals with speech sound disorders and their families/caregivers (see ASHA's resource on interprofessional education/interprofessional practice [IPE/IPP] )

- Consulting and collaborating with professionals, family members, caregivers, and others to facilitate program development and to provide supervision, evaluation, and/or expert testimony (see ASHA's resource on person- and family-centered care )

- Remaining informed of research in the area of speech sound disorders, helping advance the knowledge base related to the nature and treatment of these disorders, and using evidence-based research to guide intervention

- Advocating for individuals with speech sound disorders and their families at the local, state, and national levels

As indicated in the Code of Ethics (ASHA, 2023), SLPs who serve this population should be specifically educated and appropriately trained to do so.

See the Assessment section of the Speech Sound Disorders Evidence Map for pertinent scientific evidence, expert opinion, and client/caregiver perspective.

Screening is conducted whenever a speech sound disorder is suspected or as part of a comprehensive speech and language evaluation for a child with communication concerns. The purpose of the screening is to identify individuals who require further speech-language assessment and/or referral for other professional services.

Screening typically includes

- screening of individual speech sounds in single words and in connected speech (using formal and or informal screening measures);

- screening of oral motor functioning (e.g., strength and range of motion of oral musculature);

- orofacial examination to assess facial symmetry and identify possible structural bases for speech sound disorders (e.g., submucous cleft palate, malocclusion, ankyloglossia); and

- informal assessment of language comprehension and production.

See ASHA's resource on assessment tools, techniques, and data sources .

Screening may result in

- recommendation to monitor speech and rescreen;

- referral for multi-tiered systems of support such as response to intervention (RTI) ;

- referral for a comprehensive speech sound assessment;

- recommendation for a comprehensive language assessment, if language delay or disorder is suspected;

- referral to an audiologist for a hearing evaluation, if hearing loss is suspected; and

- referral for medical or other professional services, as appropriate.

Comprehensive Assessment