Can Beauty Save the World?

Dostoyevsky once let drop the enigmatic phrase: “Beauty will save the world.” What does this mean? For a long time it used to seem to me that this was a mere phrase. Just how could such a thing be possible? When had it ever happened in the bloodthirsty course of history that beauty had saved anyone from anything? Beauty had provided embellishment certainly, given uplift—but whom had it ever saved?

However, there is a special quality in the essence of beauty, a special quality in the status of art: the conviction carried by a genuine work of art is absolutely indisputable and tames even the strongly opposed heart. One can construct a political speech, an assertive journalistic polemic, a program for organizing society, a philosophical system, so that in appearance it is smooth, well structured, and yet it is built upon a mistake, a lie; and the hidden element, the distortion, will not immediately become visible. And a speech, or a journalistic essay, or a program in rebuttal, or a different philosophical structure can be counterposed to the first—and it will seem just as well constructed and as smooth, and everything will seem to fit. And therefore one has faith in them—yet one has no faith.

It is vain to affirm that which the heart does not confirm. In contrast, a work of art bears within itself its own confirmation: concepts which are manufactured out of whole cloth or overstrained will not stand up to being tested in images, will somehow fall apart and turn out to be sickly and pallid and convincing to no one. Works steeped in truth and presenting it to us vividly alive will take hold of us, will attract us to themselves with great power- and no one, ever, even in a later age, will presume to negate them. And so perhaps that old trinity of Truth and Good and Beauty is not just the formal outworn formula it used to seem to us during our heady, materialistic youth. If the crests of these three trees join together, as the investigators and explorers used to affirm, and if the too obvious, too straight branches of Truth and Good are crushed or amputated and cannot reach the light—yet perhaps the whimsical, unpredictable, unexpected branches of Beauty will make their way through and soar up to that very place and in this way perform the work of all three.

And in that case it was not a slip of the tongue for Dostoyevsky to say that “Beauty will save the world,” but a prophecy. After all, he was given the gift of seeing much, he was extraordinarily illumined.

And consequently perhaps art, literature, can in actual fact help the world of today.

SEED QUESTIONS FOR REFLECTION: What does Beauty mean to you? Can you share a story that illustrates Beauty also performing the work of Truth and Good? What practice helps you bring this Beauty into your work and life?

Add Your Reflection

6 past reflections.

On Aug 18, 2020 olivia wrote :

Post your reply, on oct 28, 2017 marc wrote :.

This question will generate a different answer from different people, but perhaps beauty is something that invites us to rise up beyond what we thought possible, because it speaks truth. I am a huge fan of music, and I tend to listen for beauty in music, which is to say that I like to feel that the artist is expressing what is truth to him/her. I have also read books that are beautiful. I try to bring this beauty into my work and life by remembering to be true to my values and ideals. This is often a challenge, since many forces pull us in directions that encourage us to be someone else, but when I can remember, it is empowering to feel this beauty.

On Feb 3, 2016 Ramesh Narayan wrote :

What did Dostoyevsky mean by Beauty? Beauty is a very relative term. What is beautiful for me might not be so for someone else. Everyone has his or her own definition of beauty. Beautiful eyes, beautiful face, beautiful grace, beautiful body language, beautiful occasion, beautiful nature, beautiful morning, beautiful crowd, beautiful music, beautiful this, beautiful that.....Yes, beauty is certainly a blend of truth, good and many more things that are beautiful.

On Dec 15, 2015 Craig wrote :

I feel that there is a truth to what Dostoyevsky said, but that it is far more esoteric than what Solzhenitsyn has written about here. My sense is that Beauty resonates with us in a way that is beyond the intellectual mind, under the table of the ego. As Rashimi wrote, Beauty pulls us toward it perhaps because it reminds us that we are one with it already; Beauty tickles our hearts in that place where we are not separate from anything. I felt a bit saddened reading this piece. Did Solzhenitsyn contradict his meaning with his form? To my ear, the way he expressed his ideas did not sing or dance. Where did the poetry go? Was his beauty was lost in translation? Or is beauty so relative, as David has suggested, that another reader found beauty here that I missed, because I did not have the ears to hear it? I will continue to ponder the notion that untrue ideas cannot fit into a beautiful form—yet I see an attempt to convey that very thing in advertising on a daily basis. And many of us are hooked by it, seduced... The ancient Hindu story of the Churning of the Ocean of Milk is a wonderful story to study when we wish to look at the place, the need, and the power of Beauty. It's a tale of how Beauty did save the world. In that myth, Divinity alternates between manifesting and hiding, between the numinous and the seductive, found among the perceptual world—then hopelessly lost—and only recovered again by going deep, deep within.

On Dec 15, 2015 Rashmi wrote :

Beauty certainly pulls me towards it.

On Dec 13, 2015 david doane wrote :

(Curious that I seem to struggle more with what to say about this topic than with any topic so far.) For me, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, or more accurately, in the soul of the beholder. Beauty is that which catches my attention and touches my soul in a positive way, and I feel some amount of awe, joy, and appreciation. There is a Greek saying that a thing of beauty is a joy forever. Beauty stimulates my senses and imagination, and I am caught up in it, present to it and with it and disconnected from other realities of life for a few or many moments. For me, an example of Beauty is a ballerina performing impeccably with grace and balance which simultaneously opens me to the impeccable grace and balance of Truth and Good. The practice of being in the present, seeing and responding to what is happening brings Beauty into my work and life. I suppose what appears as beauty pulls out a sliver of Beauty that is in the beholder.

- BIOGRAPHIES

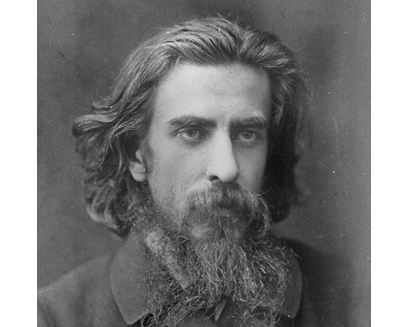

Home » Beauty will save the world – Fyodor Dostoevsky

Beauty will save the world – Fyodor Dostoevsky

What is the Meaning of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Quote: “Beauty will save the world”?

In the realm of literature and philosophical musings, Fyodor Dostoevsky, the renowned Russian author, left behind a powerful quote that has captivated readers and thinkers for generations. The quote, “Beauty will save the world,” holds deep meaning and invites us to explore the profound implications it carries. This article aims to unravel the essence of this enigmatic statement, delving into its various interpretations and shedding light on its significance.

The Context of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Quote

Fyodor Dostoevsky, known for his profound and introspective writings, included the quote “Beauty will save the world” in his novel “ The Idiot “. The novel explores the complexities of human nature and the contrast between the inherent beauty of the protagonist’s soul and the corrupted world surrounding him. Within this context, the quote becomes a beacon of hope, suggesting that beauty possesses the potential to bring salvation and transform the world.

The Interpretations of Beauty

Beauty as aesthetic pleasure.

One interpretation of Dostoevsky’s quote focuses on beauty as a source of aesthetic pleasure. In this view, beauty, whether found in nature, art, or human actions, has the power to evoke deep emotional responses. It transcends the mundane and touches the core of our being, lifting our spirits and reminding us of the inherent goodness and harmony in the world.

Beauty as Moral Transformation

Another interpretation sees beauty as a catalyst for moral transformation. According to this perspective, experiencing beauty awakens our inner virtues and inspires us to pursue higher ideals. The encounter with beauty prompts introspection and encourages us to align our actions with principles such as compassion, empathy, and justice.

Beauty as Redemption

A more profound interpretation suggests that beauty serves as a means of redemption. It implies that the transformative power of beauty can restore individuals and societies, healing the wounds inflicted by the darkness and suffering that often pervade the world. Beauty, in this sense, becomes a force that leads to salvation and renewal.

Beauty and its Relationship with the World

Dostoevsky’s quote hints at the interconnectedness between beauty and the world. It suggests that the world, with its struggles and imperfections, can find solace and redemption through encounters with beauty. By appreciating and nurturing beauty, we become agents of change, fostering harmony and inspiring others to embrace a more profound understanding of life.

Beauty’s Power to Inspire Change

Individual transformation.

Beauty has the power to transform individuals from within. When we encounter something truly beautiful, whether it’s a captivating piece of art, a breathtaking landscape, or an act of kindness, it can deeply touch our souls. These experiences have the potential to awaken dormant aspirations, reshape our perspectives, and drive us towards personal growth and self-improvement.

Societal Transformation

Furthermore, beauty can catalyze societal transformation. Throughout history, art, literature, and music have sparked revolutions, challenged societal norms, and fostered cultural progress. By appealing to the universal sense of beauty, creators can inspire collective action and ignite movements that bring positive change to the world.

The Role of Art in Manifesting Beauty

Art plays a pivotal role in manifesting beauty and conveying its transformative power. Whether through paintings, sculptures, literature, or music, artists capture the essence of beauty and offer it to the world. Through their creations, they provoke emotions, encourage introspection, and challenge conventional wisdom. Moreover, all these efforts are in service of revealing the profound truths and the redemptive potential of beauty.

Challenges and Critiques

Despite the profound message conveyed by Dostoevsky’s quote, it also faces challenges and critiques. Skeptics argue that beauty alone cannot solve the complex problems and conflicts of the world. They contend that practical actions, grounded in ethics and reason, are necessary to effect lasting change. However, proponents of Dostoevsky’s view assert that beauty serves as a catalyst, inspiring and nurturing the virtues needed to navigate the challenges we face.

The Timelessness of Dostoevsky’s Quote

Dostoevsky’s quote continues to resonate across time and cultures because it taps into the universal longing for meaning and redemption. It reminds us that amidst the chaos and suffering in the world, beauty holds the power to inspire, transform, and save. Regardless of its various interpretations, the essence of the quote lies in its capacity to evoke a deep sense of hope and a call to action.

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s quote, “Beauty will save the world,” encapsulates a profound truth that transcends time and space. It invites us to recognize the transformative power of beauty in our lives and in the world around us. Whether through aesthetic pleasure, moral transformation, or societal change, beauty has the capacity to elevate our existence and bring about redemption. Let us embrace and nurture beauty in all its forms, knowing that by doing so, we become active participants in the salvation of the world.

Dive into Fyodor Dostoevsky’s profound quotes, exploring the depths of human existence

Must Read Books by Fyodor Dostoevsky

- Crime and Punishment

- Notes from Underground

Right or wrong, it’s very pleasant to break something from time to time – Fyodor Dostoevsky

To love someone means to see them as god intended them – fyodor dostoevsky, follow us on instagram.

- Account icon Log in

- Art Prints (11x14)

- Posters (18x24)

- Paper Goods

Beauty will save the world

“Beauty will save the world” - Dostoevsky

Alexander Solzhenitsyn also wrestled with this line in his 1970 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, and we're lucky to be privy to his chain of thought here:

"One day Dostoevsky threw out the enigmatic remark: “Beauty will save the world”. What sort of a statement is that? For a long time I considered it mere words. How could that be possible? When in bloodthirsty history did beauty ever save anyone from anything? Ennobled, uplifted, yes – but whom has it saved? There is, however, a certain peculiarity in the essence of beauty, a peculiarity in the status of art: namely, the convincingness of a true work of art is completely irrefutable and it forces even an opposing heart to surrender. It is possible to compose an outwardly smooth and elegant political speech, a headstrong article, a social program, or a philosophical system on the basis of both a mistake and a lie. What is hidden, what distorted, will not immediately become obvious. Then a contradictory speech, article, program, a differently constructed philosophy rallies in opposition – and all just as elegant and smooth, and once again it works. Which is why such things are both trusted and mistrusted. In vain to reiterate what does not reach the heart. But a work of art bears within itself its own verification: conceptions which are devised or stretched do not stand being portrayed in images, they all come crashing down, appear sickly and pale, convince no one. But those works of art which have scooped up the truth and presented it to us as a living force – they take hold of us, compel us, and nobody ever, not even in ages to come, will appear to refute them. So perhaps that ancient trinity of Truth, Goodness and Beauty is not simply an empty, faded formula as we thought in the days of our self-confident, materialistic youth? If the tops of these three trees converge, as the scholars maintained, but the too blatant, too direct stems of Truth and Goodness are crushed, cut down, not allowed through – then perhaps the fantastic, unpredictable, unexpected stems of Beauty will push through and soar TO THAT VERY SAME PLACE, and in so doing will fulfil the work of all three? In that case Dostoevsky’s remark, “Beauty will save the world”, was not a careless phrase but a prophecy? After all HE was granted to see much, a man of fantastic illumination. And in that case art, literature might really be able to help the world today? It is the small insight which, over the years, I have succeeded in gaining into this matter that I shall attempt to lay before you here today."

You can read the rest of his speech at NobelPrize.org

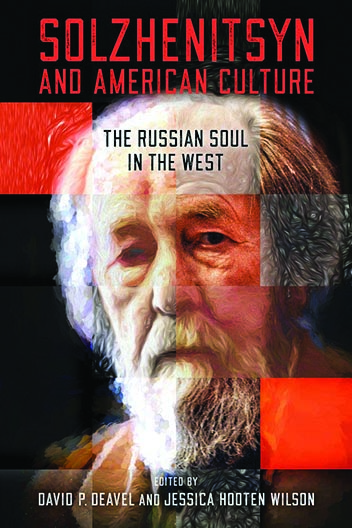

Dostoevsky, Solzenhitsyn and the current state of the world collectively inspired this illustration . We wanted to capture a sense of individuals connecting to a whole that is greater than the parts. Points of light suggest a globe at sunrise, then connect through sunrise into the shape of a magnolia flower.

Checkmark icon Added to your cart:

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

Enhanced Page Navigation

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - Nobel Lecture

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Nobel lecture.

English Russian (pdf)

Nobel Lecture in Literature 1970 *

Just as that puzzled savage who has picked up – a strange cast-up from the ocean? – something unearthed from the sands? – or an obscure object fallen down from the sky? – intricate in curves, it gleams first dully and then with a bright thrust of light. Just as he turns it this way and that, turns it over, trying to discover what to do with it, trying to discover some mundane function within his own grasp, never dreaming of its higher function.

So also we, holding Art in our hands, confidently consider ourselves to be its masters; boldly we direct it, we renew, reform and manifest it; we sell it for money, use it to please those in power; turn to it at one moment for amusement – right down to popular songs and night-clubs, and at another – grabbing the nearest weapon, cork or cudgel – for the passing needs of politics and for narrow-minded social ends. But art is not defiled by our efforts, neither does it thereby depart from its true nature, but on each occasion and in each application it gives to us a part of its secret inner light.

But shall we ever grasp the whole of that light? Who will dare to say that he has DEFINED Art, enumerated all its facets? Perhaps once upon a time someone understood and told us, but we could not remain satisfied with that for long; we listened, and neglected, and threw it out there and then, hurrying as always to exchange even the very best – if only for something new! And when we are told again the old truth, we shall not even remember that we once possessed it.

One artist sees himself as the creator of an independent spiritual world; he hoists onto his shoulders the task of creating this world, of peopling it and of bearing the all-embracing responsibility for it; but he crumples beneath it, for a mortal genius is not capable of bearing such a burden. Just as man in general, having declared himself the centre of existence, has not succeeded in creating a balanced spiritual system. And if misfortune overtakes him, he casts the blame upon the age-long disharmony of the world, upon the complexity of today’s ruptured soul, or upon the stupidity of the public.

Another artist, recognizing a higher power above, gladly works as a humble apprentice beneath God’s heaven; then, however, his responsibility for everything that is written or drawn, for the souls which perceive his work, is more exacting than ever. But, in return, it is not he who has created this world, not he who directs it, there is no doubt as to its foundations; the artist has merely to be more keenly aware than others of the harmony of the world, of the beauty and ugliness of the human contribution to it, and to communicate this acutely to his fellow-men. And in misfortune, and even at the depths of existence – in destitution, in prison, in sickness – his sense of stable harmony never deserts him.

But all the irrationality of art, its dazzling turns, its unpredictable discoveries, its shattering influence on human beings – they are too full of magic to be exhausted by this artist’s vision of the world, by his artistic conception or by the work of his unworthy fingers.

Archaeologists have not discovered stages of human existence so early that they were without art. Right back in the early morning twilights of mankind we received it from Hands which we were too slow to discern. And we were too slow to ask: FOR WHAT PURPOSE have we been given this gift? What are we to do with it?

And they were mistaken, and will always be mistaken, who prophesy that art will disintegrate, that it will outlive its forms and die. It is we who shall die – art will remain. And shall we comprehend, even on the day of our destruction, all its facets and all its possibilities?

Not everything assumes a name. Some things lead beyond words. Art inflames even a frozen, darkened soul to a high spiritual experience. Through art we are sometimes visited – dimly, briefly – by revelations such as cannot be produced by rational thinking.

Like that little looking-glass from the fairy-tales: look into it and you will see – not yourself – but for one second, the Inaccessible, whither no man can ride, no man fly. And only the soul gives a groan …

One day Dostoevsky threw out the enigmatic remark: “Beauty will save the world”. What sort of a statement is that? For a long time I considered it mere words. How could that be possible? When in bloodthirsty history did beauty ever save anyone from anything? Ennobled, uplifted, yes – but whom has it saved?

There is, however, a certain peculiarity in the essence of beauty, a peculiarity in the status of art: namely, the convincingness of a true work of art is completely irrefutable and it forces even an opposing heart to surrender. It is possible to compose an outwardly smooth and elegant political speech, a headstrong article, a social program, or a philosophical system on the basis of both a mistake and a lie. What is hidden, what distorted, will not immediately become obvious.

Then a contradictory speech, article, program, a differently constructed philosophy rallies in opposition – and all just as elegant and smooth, and once again it works. Which is why such things are both trusted and mistrusted.

In vain to reiterate what does not reach the heart.

But a work of art bears within itself its own verification: conceptions which are devised or stretched do not stand being portrayed in images, they all come crashing down, appear sickly and pale, convince no one. But those works of art which have scooped up the truth and presented it to us as a living force – they take hold of us, compel us, and nobody ever, not even in ages to come, will appear to refute them.

So perhaps that ancient trinity of Truth, Goodness and Beauty is not simply an empty, faded formula as we thought in the days of our self-confident, materialistic youth? If the tops of these three trees converge, as the scholars maintained, but the too blatant, too direct stems of Truth and Goodness are crushed, cut down, not allowed through – then perhaps the fantastic, unpredictable, unexpected stems of Beauty will push through and soar TO THAT VERY SAME PLACE, and in so doing will fulfil the work of all three?

In that case Dostoevsky’s remark, “Beauty will save the world”, was not a careless phrase but a prophecy? After all HE was granted to see much, a man of fantastic illumination.

And in that case art, literature might really be able to help the world today?

It is the small insight which, over the years, I have succeeded in gaining into this matter that I shall attempt to lay before you here today.

In order to mount this platform from which the Nobel lecture is read, a platform offered to far from every writer and only once in a lifetime, I have climbed not three or four makeshift steps, but hundreds and even thousands of them; unyielding, precipitous, frozen steps, leading out of the darkness and cold where it was my fate to survive, while others – perhaps with a greater gift and stronger than I – have perished. Of them, I myself met but a few on the Archipelago of GULAG 1 , shattered into its fractionary multitude of islands; and beneath the millstone of shadowing and mistrust I did not talk to them all, of some I only heard, of others still I only guessed. Those who fell into that abyss already bearing a literary name are at least known, but how many were never recognized, never once mentioned in public? And virtually no one managed to return. A whole national literature remained there, cast into oblivion not only without a grave, but without even underclothes, naked, with a number tagged on to its toe. Russian literature did not cease for a moment, but from the outside it appeared a wasteland! Where a peaceful forest could have grown, there remained, after all the felling, two or three trees overlooked by chance.

And as I stand here today, accompanied by the shadows of the fallen, with bowed head allowing others who were worthy before to pass ahead of me to this place, as I stand here, how am I to divine and to express what THEY would have wished to say?

This obligation has long weighed upon us, and we have understood it. In the words of Vladimir Solov’ev:

Even in chains we ourselves must complete That circle which the gods have mapped out for us.

Frequently, in painful camp seethings, in a column of prisoners, when chains of lanterns pierced the gloom of the evening frosts, there would well up inside us the words that we should like to cry out to the whole world, if the whole world could hear one of us. Then it seemed so clear: what our successful ambassador would say, and how the world would immediately respond with its comment. Our horizon embraced quite distinctly both physical things and spiritual movements, and it saw no lop-sidedness in the indivisible world. These ideas did not come from books, neither were they imported for the sake of coherence. They were formed in conversations with people now dead, in prison cells and by forest fires, they were tested against THAT life, they grew out of THAT existence.

When at last the outer pressure grew a little weaker, my and our horizon broadened and gradually, albeit through a minute chink, we saw and knew “the whole world”. And to our amazement the whole world was not at all as we had expected, as we had hoped; that is to say a world living “not by that”, a world leading “not there”, a world which could exclaim at the sight of a muddy swamp, “what a delightful little puddle!”, at concrete neck stocks, “what an exquisite necklace!”; but instead a world where some weep inconsolate tears and others dance to a light-hearted musical.

How could this happen? Why the yawning gap? Were we insensitive? Was the world insensitive? Or is it due to language differences? Why is it that people are not able to hear each other’s every distinct utterance? Words cease to sound and run away like water – without taste, colour, smell. Without trace.

As I have come to understand this, so through the years has changed and changed again the structure, content and tone of my potential speech. The speech I give today.

And it has little in common with its original plan, conceived on frosty camp evenings.

From time immemorial man has been made in such a way that his vision of the world, so long as it has not been instilled under hypnosis, his motivations and scale of values, his actions and intentions are determined by his personal and group experience of life. As the Russian saying goes, “Do not believe your brother, believe your own crooked eye.” And that is the most sound basis for an understanding of the world around us and of human conduct in it. And during the long epochs when our world lay spread out in mystery and wilderness, before it became encroached by common lines of communication, before it was transformed into a single, convulsively pulsating lump – men, relying on experience, ruled without mishap within their limited areas, within their communities, within their societies, and finally on their national territories. At that time it was possible for individual human beings to perceive and accept a general scale of values, to distinguish between what is considered normal, what incredible; what is cruel and what lies beyond the boundaries of wickedness; what is honesty, what deceit. And although the scattered peoples led extremely different lives and their social values were often strikingly at odds, just as their systems of weights and measures did not agree, still these discrepancies surprised only occasional travellers, were reported in journals under the name of wonders, and bore no danger to mankind which was not yet one.

But now during the past few decades, imperceptibly, suddenly, mankind has become one – hopefully one and dangerously one – so that the concussions and inflammations of one of its parts are almost instantaneously passed on to others, sometimes lacking in any kind of necessary immunity. Mankind has become one, but not steadfastly one as communities or even nations used to be; not united through years of mutual experience, neither through possession of a single eye, affectionately called crooked, nor yet through a common native language, but, surpassing all barriers, through international broadcasting and print. An avalanche of events descends upon us – in one minute half the world hears of their splash. But the yardstick by which to measure those events and to evaluate them in accordance with the laws of unfamiliar parts of the world – this is not and cannot be conveyed via soundwaves and in newspaper columns. For these yardsticks were matured and assimilated over too many years of too specific conditions in individual countries and societies; they cannot be exchanged in mid-air. In the various parts of the world men apply their own hard-earned values to events, and they judge stubbornly, confidently, only according to their own scales of values and never according to any others.

And if there are not many such different scales of values in the world, there are at least several; one for evaluating events near at hand, another for events far away; aging societies possess one, young societies another; unsuccessful people one, successful people another. The divergent scales of values scream in discordance, they dazzle and daze us, and in order that it might not be painful we steer clear of all other values, as though from insanity, as though from illusion, and we confidently judge the whole world according to our own home values. Which is why we take for the greater, more painful and less bearable disaster not that which is in fact greater, more painful and less bearable, but that which lies closest to us. Everything which is further away, which does not threaten this very day to invade our threshold – with all its groans, its stifled cries, its destroyed lives, even if it involves millions of victims – this we consider on the whole to be perfectly bearable and of tolerable proportions.

In one part of the world, not so long ago, under persecutions not inferior to those of the ancient Romans’, hundreds of thousands of silent Christians gave up their lives for their belief in God. In the other hemisphere a certain madman, (and no doubt he is not alone), speeds across the ocean to DELIVER us from religion – with a thrust of steel into the high priest! He has calculated for each and every one of us according to his personal scale of values!

That which from a distance, according to one scale of values, appears as enviable and flourishing freedom, at close quarters, and according to other values, is felt to be infuriating constraint calling for buses to be overthrown. That which in one part of the world might represent a dream of incredible prosperity, in another has the exasperating effect of wild exploitation demanding immediate strike. There are different scales of values for natural catastrophes: a flood craving two hundred thousand lives seems less significant than our local accident. There are different scales of values for personal insults: sometimes even an ironic smile or a dismissive gesture is humiliating, while for others cruel beatings are forgiven as an unfortunate joke. There are different scales of values for punishment and wickedness: according to one, a month’s arrest, banishment to the country, or an isolation-cell where one is fed on white rolls and milk, shatters the imagination and fills the newspaper columns with rage. While according to another, prison sentences of twenty-five years, isolation-cells where the walls are covered with ice and the prisoners stripped to their underclothes, lunatic asylums for the sane, and countless unreasonable people who for some reason will keep running away, shot on the frontiers – all this is common and accepted. While the mind is especially at peace concerning that exotic part of the world about which we know virtually nothing, from which we do not even receive news of events, but only the trivial, out-of-date guesses of a few correspondents.

Yet we cannot reproach human vision for this duality, for this dumbfounded incomprehension of another man’s distant grief, man is just made that way. But for the whole of mankind, compressed into a single lump, such mutual incomprehension presents the threat of imminent and violent destruction. One world, one mankind cannot exist in the face of six, four or even two scales of values: we shall be torn apart by this disparity of rhythm, this disparity of vibrations.

A man with two hearts is not for this world, neither shall we be able to live side by side on one Earth.

But who will co-ordinate these value scales, and how? Who will create for mankind one system of interpretation, valid for good and evil deeds, for the unbearable and the bearable, as they are differentiated today? Who will make clear to mankind what is really heavy and intolerable and what only grazes the skin locally? Who will direct the anger to that which is most terrible and not to that which is nearer? Who might succeed in transferring such an understanding beyond the limits of his own human experience? Who might succeed in impressing upon a bigoted, stubborn human creature the distant joy and grief of others, an understanding of dimensions and deceptions which he himself has never experienced? Propaganda, constraint, scientific proof – all are useless. But fortunately there does exist such a means in our world! That means is art. That means is literature.

They can perform a miracle: they can overcome man’s detrimental peculiarity of learning only from personal experience so that the experience of other people passes him by in vain. From man to man, as he completes his brief spell on Earth, art transfers the whole weight of an unfamiliar, lifelong experience with all its burdens, its colours, its sap of life; it recreates in the flesh an unknown experience and allows us to possess it as our own.

And even more, much more than that; both countries and whole continents repeat each other’s mistakes with time lapses which can amount to centuries. Then, one would think, it would all be so obvious! But no; that which some nations have already experienced, considered and rejected, is suddenly discovered by others to be the latest word. And here again, the only substitute for an experience we ourselves have never lived through is art, literature. They possess a wonderful ability: beyond distinctions of language, custom, social structure, they can convey the life experience of one whole nation to another. To an inexperienced nation they can convey a harsh national trial lasting many decades, at best sparing an entire nation from a superfluous, or mistaken, or even disastrous course, thereby curtailing the meanderings of human history.

It is this great and noble property of art that I urgently recall to you today from the Nobel tribune.

And literature conveys irrefutable condensed experience in yet another invaluable direction; namely, from generation to generation. Thus it becomes the living memory of the nation. Thus it preserves and kindles within itself the flame of her spent history, in a form which is safe from deformation and slander. In this way literature, together with language, protects the soul of the nation.

(In recent times it has been fashionable to talk of the levelling of nations, of the disappearance of different races in the melting-pot of contemporary civilization. I do not agree with this opinion, but its discussion remains another question. Here it is merely fitting to say that the disappearance of nations would have impoverished us no less than if all men had become alike, with one personality and one face. Nations are the wealth of mankind, its collective personalities; the very least of them wears its own special colours and bears within itself a special facet of divine intention.)

But woe to that nation whose literature is disturbed by the intervention of power. Because that is not just a violation against “freedom of print”, it is the closing down of the heart of the nation, a slashing to pieces of its memory. The nation ceases to be mindful of itself, it is deprived of its spiritual unity, and despite a supposedly common language, compatriots suddenly cease to understand one another. Silent generations grow old and die without ever having talked about themselves, either to each other or to their descendants. When writers such as Achmatova and Zamjatin – interred alive throughout their lives – are condemned to create in silence until they die, never hearing the echo of their written words, then that is not only their personal tragedy, but a sorrow to the whole nation, a danger to the whole nation.

In some cases moreover – when as a result of such a silence the whole of history ceases to be understood in its entirety – it is a danger to the whole of mankind.

At various times and in various countries there have arisen heated, angry and exquisite debates as to whether art and the artist should be free to live for themselves, or whether they should be for ever mindful of their duty towards society and serve it albeit in an unprejudiced way. For me there is no dilemma, but I shall refrain from raising once again the train of arguments. One of the most brilliant addresses on this subject was actually Albert Camus’ Nobel speech, and I would happily subscribe to his conclusions. Indeed, Russian literature has for several decades manifested an inclination not to become too lost in contemplation of itself, not to flutter about too frivolously. I am not ashamed to continue this tradition to the best of my ability. Russian literature has long been familiar with the notions that a writer can do much within his society, and that it is his duty to do so.

Let us not violate the RIGHT of the artist to express exclusively his own experiences and introspections, disregarding everything that happens in the world beyond. Let us not DEMAND of the artist, but – reproach, beg, urge and entice him – that we may be allowed to do. After all, only in part does he himself develop his talent; the greater part of it is blown into him at birth as a finished product, and the gift of talent imposes responsibility on his free will. Let us assume that the artist does not OWE anybody anything: nevertheless, it is painful to see how, by retiring into his self-made worlds or the spaces of his subjective whims, he CAN surrender the real world into the hands of men who are mercenary, if not worthless, if not insane.

Our Twentieth Century has proved to be more cruel than preceding centuries, and the first fifty years have not erased all its horrors. Our world is rent asunder by those same old cave-age emotions of greed, envy, lack of control, mutual hostility which have picked up in passing respectable pseudonyms like class struggle, racial conflict, struggle of the masses, trade-union disputes. The primeval refusal to accept a compromise has been turned into a theoretical principle and is considered the virtue of orthodoxy. It demands millions of sacrifices in ceaseless civil wars, it drums into our souls that there is no such thing as unchanging, universal concepts of goodness and justice, that they are all fluctuating and inconstant. Therefore the rule – always do what’s most profitable to your party. Any professional group no sooner sees a convenient opportunity to BREAK OFF A PIECE, even if it be unearned, even if it be superfluous, than it breaks it off there and then and no matter if the whole of society comes tumbling down. As seen from the outside, the amplitude of the tossings of western society is approaching that point beyond which the system becomes metastable and must fall. Violence, less and less embarrassed by the limits imposed by centuries of lawfulness, is brazenly and victoriously striding across the whole world, unconcerned that its infertility has been demonstrated and proved many times in history. What is more, it is not simply crude power that triumphs abroad, but its exultant justification. The world is being inundated by the brazen conviction that power can do anything, justice nothing. Dostoevsky’s DEVILS – apparently a provincial nightmare fantasy of the last century – are crawling across the whole world in front of our very eyes, infesting countries where they could not have been dreamed of; and by means of the hijackings, kidnappings, explosions and fires of recent years they are announcing their determination to shake and destroy civilization! And they may well succeed. The young, at an age when they have not yet any experience other than sexual, when they do not yet have years of personal suffering and personal understanding behind them, are jubilantly repeating our depraved Russian blunders of the Nineteenth Century, under the impression that they are discovering something new. They acclaim the latest wretched degradation on the part of the Chinese Red Guards as a joyous example. In shallow lack of understanding of the age-old essence of mankind, in the naive confidence of inexperienced hearts they cry: let us drive away THOSE cruel, greedy oppressors, governments, and the new ones (we!), having laid aside grenades and rifles, will be just and understanding. Far from it! . . . But of those who have lived more and understand, those who could oppose these young – many do not dare oppose, they even suck up, anything not to appear “conservative”. Another Russian phenomenon of the Nineteenth Century which Dostoevsky called SLAVERY TO PROGRESSIVE QUIRKS.

The spirit of Munich has by no means retreated into the past; it was not merely a brief episode. I even venture to say that the spirit of Munich prevails in the Twentieth Century. The timid civilized world has found nothing with which to oppose the onslaught of a sudden revival of barefaced barbarity, other than concessions and smiles. The spirit of Munich is a sickness of the will of successful people, it is the daily condition of those who have given themselves up to the thirst after prosperity at any price, to material well-being as the chief goal of earthly existence. Such people – and there are many in today’s world – elect passivity and retreat, just so as their accustomed life might drag on a bit longer, just so as not to step over the threshold of hardship today – and tomorrow, you’ll see, it will all be all right. (But it will never be all right! The price of cowardice will only be evil; we shall reap courage and victory only when we dare to make sacrifices.)

And on top of this we are threatened by destruction in the fact that the physically compressed, strained world is not allowed to blend spiritually; the molecules of knowledge and sympathy are not allowed to jump over from one half to the other. This presents a rampant danger: THE SUPPRESSION OF INFORMATION between the parts of the planet. Contemporary science knows that suppression of information leads to entropy and total destruction. Suppression of information renders international signatures and agreements illusory; within a muffled zone it costs nothing to reinterpret any agreement, even simpler – to forget it, as though it had never really existed. (Orwell understood this supremely.) A muffled zone is, as it were, populated not by inhabitants of the Earth, but by an expeditionary corps from Mars; the people know nothing intelligent about the rest of the Earth and are prepared to go and trample it down in the holy conviction that they come as “liberators”.

A quarter of a century ago, in the great hopes of mankind, the United Nations Organization was born. Alas, in an immoral world, this too grew up to be immoral. It is not a United Nations Organization but a United Governments Organization where all governments stand equal; those which are freely elected, those imposed forcibly, and those which have seized power with weapons. Relying on the mercenary partiality of the majority UNO jealously guards the freedom of some nations and neglects the freedom of others. As a result of an obedient vote it declined to undertake the investigation of private appeals – the groans, screams and beseechings of humble individual PLAIN PEOPLE – not large enough a catch for such a great organization. UNO made no effort to make the Declaration of Human Rights, its best document in twenty-five years, into an OBLIGATORY condition of membership confronting the governments. Thus it betrayed those humble people into the will of the governments which they had not chosen.

It would seem that the appearance of the contemporary world rests solely in the hands of the scientists; all mankind’s technical steps are determined by them. It would seem that it is precisely on the international goodwill of scientists, and not of politicians, that the direction of the world should depend. All the more so since the example of the few shows how much could be achieved were they all to pull together. But no; scientists have not manifested any clear attempt to become an important, independently active force of mankind. They spend entire congresses in renouncing the sufferings of others; better to stay safely within the precincts of science. That same spirit of Munich has spread above them its enfeebling wings.

What then is the place and role of the writer in this cruel, dynamic, split world on the brink of its ten destructions? After all we have nothing to do with letting off rockets, we do not even push the lowliest of hand-carts, we are quite scorned by those who respect only material power. Is it not natural for us too to step back, to lose faith in the steadfastness of goodness, in the indivisibility of truth, and to just impart to the world our bitter, detached observations: how mankind has become hopelessly corrupt, how men have degenerated, and how difficult it is for the few beautiful and refined souls to live amongst them?

But we have not even recourse to this flight. Anyone who has once taken up the WORD can never again evade it; a writer is not the detached judge of his compatriots and contemporaries, he is an accomplice to all the evil committed in his native land or by his countrymen. And if the tanks of his fatherland have flooded the asphalt of a foreign capital with blood, then the brown spots have slapped against the face of the writer forever. And if one fatal night they suffocated his sleeping, trusting Friend, then the palms of the writer bear the bruises from that rope. And if his young fellow citizens breezily declare the superiority of depravity over honest work, if they give themselves over to drugs or seize hostages, then their stink mingles with the breath of the writer.

Shall we have the temerity to declare that we are not responsible for the sores of the present-day world?

However, I am cheered by a vital awareness of WORLD LITERATURE as of a single huge heart, beating out the cares and troubles of our world, albeit presented and perceived differently in each of its corners.

Apart from age-old national literatures there existed, even in past ages, the conception of world literature as an anthology skirting the heights of the national literatures, and as the sum total of mutual literary influences. But there occurred a lapse in time: readers and writers became acquainted with writers of other tongues only after a time lapse, sometimes lasting centuries, so that mutual influences were also delayed and the anthology of national literary heights was revealed only in the eyes of descendants, not of contemporaries.

But today, between the writers of one country and the writers and readers of another, there is a reciprocity if not instantaneous then almost so. I experience this with myself. Those of my books which, alas, have not been printed in my own country have soon found a responsive, worldwide audience, despite hurried and often bad translations. Such distinguished western writers as Heinrich Böll have undertaken critical analysis of them. All these last years, when my work and freedom have not come crashing down, when contrary to the laws of gravity they have hung suspended as though on air, as though on NOTHING – on the invisible dumb tension of a sympathetic public membrane; then it was with grateful warmth, and quite unexpectedly for myself, that I learnt of the further support of the international brotherhood of writers. On my fiftieth birthday I was astonished to receive congratulations from well-known western writers. No pressure on me came to pass by unnoticed. During my dangerous weeks of exclusion from the Writers’ Union the WALL OF DEFENCE advanced by the world’s prominent writers protected me from worse persecutions; and Norwegian writers and artists hospitably prepared a roof for me, in the event of my threatened exile being put into effect. Finally even the advancement of my name for the Nobel Prize was raised not in the country where I live and write, but by Francois Mauriac and his colleagues. And later still entire national writers’ unions have expressed their support for me.

Thus I have understood and felt that world literature is no longer an abstract anthology, nor a generalization invented by literary historians; it is rather a certain common body and a common spirit, a living heartfelt unity reflecting the growing unity of mankind. State frontiers still turn crimson, heated by electric wire and bursts of machine fire; and various ministries of internal affairs still think that literature too is an “internal affair” falling under their jurisdiction; newspaper headlines still display: “No right to interfere in our internal affairs!” Whereas there are no INTERNAL AFFAIRS left on our crowded Earth! And mankind’s sole salvation lies in everyone making everything his business; in the people of the East being vitally concerned with what is thought in the West, the people of the West vitally concerned with what goes on in the East. And literature, as one of the most sensitive, responsive instruments possessed by the human creature, has been one of the first to adopt, to assimilate, to catch hold of this feeling of a growing unity of mankind. And so I turn with confidence to the world literature of today – to hundreds of friends whom I have never met in the flesh and whom I may never see.

Friends! Let us try to help if we are worth anything at all! Who from time immemorial has constituted the uniting, not the dividing, strength in your countries, lacerated by discordant parties, movements, castes and groups? There in its essence is the position of writers: expressers of their native language – the chief binding force of the nation, of the very earth its people occupy, and at best of its national spirit.

I believe that world literature has it in its power to help mankind, in these its troubled hours, to see itself as it really is, notwithstanding the indoctrinations of prejudiced people and parties. World literature has it in its power to convey condensed experience from one land to another so that we might cease to be split and dazzled, that the different scales of values might be made to agree, and one nation learn correctly and concisely the true history of another with such strength of recognition and painful awareness as it had itself experienced the same, and thus might it be spared from repeating the same cruel mistakes. And perhaps under such conditions we artists will be able to cultivate within ourselves a field of vision to embrace the WHOLE WORLD: in the centre observing like any other human being that which lies nearby, at the edges we shall begin to draw in that which is happening in the rest of the world. And we shall correlate, and we shall observe world proportions.

And who, if not writers, are to pass judgement – not only on their unsuccessful governments, (in some states this is the easiest way to earn one’s bread, the occupation of any man who is not lazy), but also on the people themselves, in their cowardly humiliation or self-satisfied weakness? Who is to pass judgement on the light-weight sprints of youth, and on the young pirates brandishing their knives?

We shall be told: what can literature possibly do against the ruthless onslaught of open violence? But let us not forget that violence does not live alone and is not capable of living alone: it is necessarily interwoven with falsehood. Between them lies the most intimate, the deepest of natural bonds. Violence finds its only refuge in falsehood, falsehood its only support in violence. Any man who has once acclaimed violence as his METHOD must inexorably choose falsehood as his PRINCIPLE. At its birth violence acts openly and even with pride. But no sooner does it become strong, firmly established, than it senses the rarefaction of the air around it and it cannot continue to exist without descending into a fog of lies, clothing them in sweet talk. It does not always, not necessarily, openly throttle the throat, more often it demands from its subjects only an oath of allegiance to falsehood, only complicity in falsehood.

And the simple step of a simple courageous man is not to partake in falsehood, not to support false actions! Let THAT enter the world, let it even reign in the world – but not with my help. But writers and artists can achieve more: they can CONQUER FALSEHOOD! In the struggle with falsehood art always did win and it always does win! Openly, irrefutably for everyone! Falsehood can hold out against much in this world, but not against art.

And no sooner will falsehood be dispersed than the nakedness of violence will be revealed in all its ugliness – and violence, decrepit, will fall.

That is why, my friends, I believe that we are able to help the world in its white-hot hour. Not by making the excuse of possessing no weapons, and not by giving ourselves over to a frivolous life – but by going to war!

Proverbs about truth are well-loved in Russian. They give steady and sometimes striking expression to the not inconsiderable harsh national experience:

ONE WORD OF TRUTH SHALL OUTWEIGH THE WHOLE WORLD.

And it is here, on an imaginary fantasy, a breach of the principle of the conservation of mass and energy, that I base both my own activity and my appeal to the writers of the whole world.

*Delivered only to the Swedish Academy and not actually given as a lecture.

1. The Central Administration of Corrective Labour Camps.

2024 Nobel Prize announcements

Six days, six prizes.

Explore prizes and laureates

Can Beauty Save the World?

IS IT MORE ACCESSIBLE THAN THE TRUE & THE GOOD?

In Dostoevsky’s The Idiot , the dying Teréntyev asks Prince Myshkin, “Is it true, Prince, that you once said that beauty will save the world?” The thesis that beauty will save the world is arresting, but what are we to make of it? In his 1970 Nobel Prize lecture, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn affirms the thesis, though he admits that for a long time he could make no sense of the claim. Others say it is false. Isn’t beauty’s failure to save even itself the stuff of history? In its beauty, Baghdad fell to the Mongols; in its loveliness, Japan’s Heian met destruction. And are not artists all too often self-destructive? Though starkly different, Van Gogh and Thomas Kinkade shared a like fate.

Solzhenitsyn does not deny history’s lessons. But such reproval, he says, fails to see that barbarism cannot finally extinguish beauty. And while an artist who would create a private reality might fall beneath its burden, one who is harmony’s apprentice finds an enduring home. Yes, art falters; but there is also success. Even now a developing world literature speaks to us all.

Yet there is more. Beauty, Solzhenitsyn says, is a transcendental; it joins, in troika fashion, with truth and goodness. In our time, truth suffers institutional betrayal, and a legion of partisans subverts the good. Nonetheless, he tells us,

A work of art bears within itself its own verification: conceptions which are devised or stretched…come crashing down [and] convince no one. But those works of art which have scooped up the truth and present it to us as a living force — they take hold of us, compel us, and nobody ever, not even in ages to come, will appear to refute them.

Thus beauty holds a privileged position. Even if the “stems of Truth and Goodness are crushed [perhaps] the fantastic, unpredictable, unexpected stems of Beauty will push through…and in so doing will fulfill the work of all three.” In short, we can still live in hope.

Enjoyed reading this?

READ MORE! REGISTER TODAY

Choose a year

- Literature & Literary Criticism

- Flannery O'Connor

- Lavender Mafia Files

- Neoconservatism

"Catholicism's Intellectual Prizefighter!"

- Karl Keating

Strengthen the Catholic cause.

SUPPORT NOR TODAY

You May Also Enjoy

Poe uses the doppelgänger motif as a physical manifestation of Wilson’s conscience and ultimately shows the demise of a man who, blinded by his sins, kills his own conscience.

Williams, an influential British theologian and accomplished man of letters, was best known as a principal member of the Inklings.

Thirty years ago the Japanese novelist Shusaku Endo published Silence, a novel meant to tell…

Become A Donor

Contact Info

684 West College St. Sun City, United States America, 064781.

(+55) 654 - 545 - 1235

The Meaning of Dostoevsky’s “Beauty Will Save the World”

- Essays Slider

- November 28, 2013

By Vladimir Soloviev

Dostoevsky not only preached, but, to a certain degree also demonstrated in his own activity this reunification of concerns common to humanity–at least of the highest among these concerns–in one Christian idea.

Being a religious person, he was at the same time a free thinker and a powerful artist. These three aspects , these three higher concerns were not differentiated in him and did not exclude one another, but entered indivisibly into all his activity. In his convictions he never separated truth from good and beauty; in his artistic creativity he never placed beauty apart from the good and the true.

And he was right, because these three live only in their unity. The good, taken separately from truth and beauty, is only an indistinct feeling, a powerless upwelling; truth taken abstractly is an empty word; and beauty without truth and the good is an idol. For Dostoevsky, these were three inseparable forms of one absolute Idea.

The infinity of the human soul–having been revealed in Christ and capable of fitting into itself all the boundlessness of divinity–is at one and the same time both the greatest good, the highest truth, and the most perfect beauty.

Truth is good, perceived by the human mind; beauty is the same good and the same truth, corporeally embodied in solid living form.

And its full embodiment–the end, the goal, and the perfection–already exists in everything, and this is why Dostoevsky said that beauty will save the world.

Source: Mind Your Maker

“Pelicans” (detail) painted by Michael Moukios. Click image to enlarge.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Tasmanian Times

Solzhenitsyn: Beauty will save the world?

Alexander Solzhenitsyn Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech 1970

AS THE SAVAGE, WHO IN BEWILDERMENT has picked up a strange sea–leaving, a thing hidden in the sand, or an incomprehensible something fallen out of the sky–something intricately curved, sometimes shimmering dully, sometimes shining in a bright ray of light–turns it this way and that, turns it looking for a way to use it, for some ordinary use to which he can put it, without suspecting an extraordinary one…

Alexander Solzhenitsyn Nobel Lecture (1970)

Translated from the Russian by F.D. Reeve

So we, holding Art in our hands, self-confidently consider ourselves its owners, brashly give it aim, renovate it, re-form it, make manifestoes of it, sell it for cash, play up to the powerful with it, and turn it around at times for entertainment, even in vaudeville songs and in nightclubs, and at times–using stopper or stick, whichever comes first–for transitory political or limited social needs. But Art is not profaned by our attempts, does not because of them lose touch with its source, Each time and by each use it yields us a part of its mysterious inner light.

But will we comprehend all that light? Who will dare say that he has DEFINED art? That he has tabulated all its facets? Perhaps someone in ages past did understand and named them for us, but we could not hold still; we listened; we were scornful; we discarded them at once, always in a hurry to replace even the best with anything new! And when the old truth is told us again, we do not remember that we once possessed it.

One kind of artist imagines himself the creator of an independent spiritual world and shoulders the act of creating that world and the people in it, assuming total responsibility for it–but he collapses, for no mortal genius is able to hold up under such a load. Just as man, who once declared himself the center of existence, has not been able to create a stable spiritual system. When failure overwhelms him, he blames it on the age-old discord of the world, on the complexity of the fragmented and torn modern soul, or on the public’s lack of understanding.

Another artist acknowledges a higher power above him and joyfully works as a common apprentice under God’s heaven, although his responsibility for all that he writes down or depicts, and for those who understand him, is all the greater. On the other hand, he did not create the world, it is not given direction by him, it is a world about whose foundations he has no doubt. The task of the artist is to sense more keenly than others the harmony of the world, the beauty and the outrage of what man has done to it, and poignantly to let people know. In failure as well as in the lower depths–in poverty, in prison, in illness–the consciousness of a stable harmony will never leave him.

All the irrationality of art, however, its blinding sudden turns, its unpredictable discoveries, its profound impact on people, are too magical to be exhausted by the artist’s view of the world, by his overall design, or by the work of his unworthy hands.

Archaeologists have uncovered no early stages of human existence so primitive that they were without art. Even before the dawn of civilization we had received this gift from Hands we were not quick enough to discern. And we were not quick enough to ask: WHAT is this gift FOR? What are we to do with it?

All who predict that art is disintegrating, that it has outgrown its forms, and that it is dying are wrong and will be wrong. We will die, but art will remain. Will we, before we go under, ever understand all its facets and all its ends?

Not everything has a name. Some things lead us into a realm beyond words. Art warms even an icy and depressed heart, opening it to lofty spiritual experience. By means of art we are sometimes sent -dimly, briefly–revelations unattainable by reason.

Like that little mirror in the fairy tales–look into it, and you will see not yourself but, for a moment, that which passeth understanding, a realm to which no man can ride or fly. And for which the soul begins to ache…

2 DOSTOEVSKY ONCE ENIGMATICALLY let drop the phrase: “Beauty will save the world.” What does this mean? For a long time I thought it merely a phrase. Was such a thing possible? When in our bloodthirsty history did beauty ever save anyone from anything? Ennobled, elevated, yes; but whom has it saved?

There is, however, something special in the essence of beauty, a special quality in art: the conviction carried by a genuine work of art is absolute and subdues even a resistant heart. A political speech, hasty newspaper comment, a social program, a philosophical system can, as far as appearances are concerned, be built smoothly and consistently on an error or a lie; and what is concealed and distorted will not be immediately clear. But then to counteract it comes a contradictory speech, commentary, program, or differently constructed philosophy–and again everything seems smooth and graceful, and again hangs together. That is why they inspire trust–and distrust.

There is no point asserting and reasserting what the heart cannot believe.

A work of art contains its verification in itself: artificial, strained concepts do not withstand the test of being turned into images; they fall to pieces, turn out to be sickly and pale, convince no one. Works which draw on truth and present it to us in live and concentrated form grip us, compellingly involve us, and no one ever, not even ages hence, will come forth to refute them.

Perhaps then the old trinity of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty is not simply the dressed-up, worn-out formula we thought it in our presumptuous, materialistic youth? If the crowns of these three trees meet, as scholars have asserted, and if the too obvious, too straight sprouts of Truth and Goodness have been knocked down, cut off, not let grow, perhaps the whimsical, unpredictable, unexpected branches of Beauty will work their way through, rise up TO THAT VERY PLACE, and thus complete the work of all three?

Then what Dostoevsky wrote–“Beauty will save the world”–is not a slip of the tongue but a prophecy. After all, he had the gift of seeing much, a man wondrously filled with light.

And in that case could not art and literature, in fact, help the modern world?

What little I have managed to learn about this over the years I will try to set forth here today.

TO REACH THIS CHAIR FROM WHICH the Nobel Lecture is delivered–a chair by no means offered to every writer and offered only once in a lifetime–I have mounted not three or four temporary steps but hundreds or even thousands, fixed, steep, covered with ice, out of the dark and the cold where I was fated to survive, but others, perhaps more talented, stronger than I, perished. I myself met but few of them in the Gulag Archipelago,1 a multitude of scattered island fragments. Indeed, under the millstone of surveillance and mistrust, I did not talk to just any man; of some I only heard; and of others I only guessed. Those with a name in literature who vanished into that abyss are, at least, known; but how many were unrecognized, never once publicly mentioned? And so very few, almost no one ever managed to return. A whole national literature is there, buried without a coffin, without even underwear, naked, a number tagged on its toe. Not for a moment did Russian literature cease, yet from outside it seemed a wasteland. Where a harmonious forest could have grown, there were left, after all the cutting, two or three trees accidentally overlooked.

And today how am I, accompanied by the shades of the fallen, my head bowed to let pass forward to this platform others worthy long before me, today how am I to guess and to express what they would have wished to say?

This obligation has long lain on us, and we have understood it. In Vladimir Solovyov’s words:

But even chained, we must ourselves complete That circle which the gods have preordained.

In agonizing moments in camp, in columns of prisoners at night, in the freezing darkness through which the little chains of lanterns shone, there often rose in our throats something we wanted to shout out to the whole world, if only the world could have heard one of us. Then it seemed very clear what our lucky messenger would say and how immediately and positively the whole world would respond. Our field of vision was filled with physical objects and spiritual forces, and in that clearly focused world nothing seemed to outbalance them. Such ideas came not from books and were not borrowed for the sake of harmony or coherence; they were formulated in prison cells and around forest campfires, in conversations with persons now dead, were hardened by that life, developed out of there.

When the outside pressures were reduced, my outlook and our outlook widened, and gradually, although through a tiny crack, that “whole world” outside came in sight and was recognized. Startlingly for us, the “whole world” turned out to be not at all what we had hoped: it was a world leading “not up there” but exclaiming at the sight of a dismal swamp, “What an enchanting meadow!” or at a set of prisoner’s concrete stocks, “What an exquisite necklace!”–a world in which, while flowing tears rolled down the cheeks of some, others danced to the carefree tunes of a musical.

How did this come about? Why did such an abyss open? Were we unfeeling, or was the world? Or was it because of a difference in language? Why are people not capable of grasping each other’s every clear and distinct speech? Words die away and flow off like water–leaving no taste, no color, no smell. Not a trace.

Insofar as I understand it, the structure, import, and tone of speech possible for me–of my speech here today–have changed with the years.

It now scarcely resembles the speech which I first conceived on those freezing nights in prison camp.

FOR AGES, SUCH HAS BEEN MAN’S nature that his view of the world (when not induced by hypnosis), his motivation and scale of values, his actions and his intentions have been determined by his own personal and group experiences of life. As the Russian proverb puts it, “Don’t trust your brother, trust your own bad eye.” This is the soundest basis for understanding one’s environment and one’s behavior in it. During the long eras when our world was obscurely and bewilderingly fragmented, before a unified communications system had transformed it and it had turned into a single, convulsively beating lump, men were unerringly guided by practical experience in their own local area, then in their own community, in their own society, and finally in their own national territory. The possibility then existed for an individual to see with his own eyes and to accept a common scale of values–what was considered average, what improbable; what was cruel, what beyond all bounds of evil; what was honesty, what deceit. Even though widely scattered peoples lived differently and their scales of social values might be strikingly dissimilar, like their systems of weights and measures, these differences surprised none but the occasional tourist, were written up as heathen wonders, and in no way threatened the rest of not yet united mankind.

In recent decades, however, mankind has imperceptibly, suddenly, become one, united in a way which offers both hope and danger, for shock and infection in one part are almost instantaneously transmitted to others, which often have no immunity. Mankind has become one, but not in the way the community or even the nation used to be stably united, not through accumulated practical experience, not through its own, good-naturedly so-called bad eye, not even through its own well-understood, native tongue, but, leaping over all barriers, through the international press and radio. A wave of events washes over us and, in a moment, half the world hears the splash, but the standards for measuring these things and for evaluating them, according to the laws of those parts of the world about which we know nothing, are not and cannot be broadcast through the ether or reduced to newsprint. These standards have too long and too specifically been accepted by and incorporated in too special a way into the lives of various lands and societies to be communicated in thin air. In various parts of the world, men apply to events a scale of values achieved by their own long suffering, and they uncompromisingly, self-reliantly judge only by their own scale, and by no one else’s.

If there are not a multitude of such scales in the world, nevertheless there are at least several: a scale for local events, a scale for things far away; for old societies, and for new; for the prosperous, and for the disadvantaged. The points and markings on the scale glaringly do not coincide; they confuse us, hurt our eyes, and so, to avoid pain, we brush aside all scales not our own, as if they were follies or delusions, and confidently judge the whole world according to our own domestic values. Therefore, what seems to us more important, more painful, and more unendurable is really not what is more important, more painful, and more unendurable but merely that which is closer to home. Everything distant which, for all its moans and muffled cries, its ruined lives and, even, millions of victims, does not threaten to come rolling up to our threshold today we consider, in general, endurable and of tolerable dimensions.

On one side, persecuted no less than under the old Romans, hundreds of thousands of mute Christians give up their lives for their belief in God. On the other side of the world, a madman (and probably he is not the only one) roars across the ocean in order to FREE US from religion with a blow of steel at the Pontiff! Using his own personal scale, he has decided things for everyone.

What on one scale seems, from far off, to be enviable and prosperous freedom, on another, close up, is felt to be irritating coercion calling for the overturning of buses. What in one country seems a dream of improbable prosperity in another arouses indignation as savage exploitation calling for an immediate strike. Scales of values differ even for natural calamities: a flood with two hundred thousand victims matters less than a local traffic accident. Scales differ for personal insults: at times, merely a sardonic smile or a dismissive gesture is humiliating, whereas, at others, cruel beatings are regarded as a bad joke. Scales differ for punishments and for wrongdoing. On one scale, a month’s arrest, or exile to the country, or “solitary confinement” on white bread and milk rocks the imagination and fills the newspaper columns with outrage. On another, both accepted and excused are prison terms of twenty-five years, solitary confinement in cells with ice-covered walls and prisoners stripped to their underclothing, insane asylums for healthy men, and border shootings of countless foolish people who, for some reason, keep trying to escape. The heart is especially at ease with regard to that exotic land about which nothing is known, from which no events ever reach us except the belated and trivial conjectures of a few correspondents.

For such ambivalence, for such thickheaded lack of understanding of someone else’s far-off grief, however, mankind is not at fault: that is how man is made. But for mankind as a whole, squeezed into one lump, such mutual lack of understanding carries the threat of imminent and violent destruction. Given six, four, or even two scales of values, there cannot be one world, one single humanity: the difference in rhythms, in oscillations, will tear mankind asunder. We will not survive together on one Earth, just as a man with two hearts is not meant for this world.

WHO WILL COORDINATE THESE SCALES of values, and how? Who will give mankind one single system for reading its instruments, both for wrongdoing and for doing good, for the intolerable and the tolerable as they are distinguished from each other today? Who will make clear for mankind what is really oppressive and unbearable and what, for being so near, rubs us raw–and thus direct our anger against what is in fact terrible and not merely near at hand? Who is capable of extending such an understanding across the boundaries of his own personal experience? Who has the skill to make a narrow, obstinate human being aware of others’ far-off grief and joy, to make him understand dimensions and delusions he himself has never lived through? Propaganda, coercion, and scientific proofs are all powerless. But, happily, in our world there is a way. It is art, and it is literature.

There is a miracle which they can work: they can overcome man’s unfortunate trait of learning only through his own experience, unaffected by that of others. From man to man, compensating for his brief time on earth, art communicates whole the burden of another’s long life experience with all its hardships, colors, and vitality, re-creating in the flesh what another has experienced, and allowing it to be acquired as one’s own.

More important, much more important: countries and whole continents belatedly repeat each other’s mistakes, sometimes after centuries when, it would , seem, everything should be so clear! No: what some nations have gone through, thought through, and rejected, suddenly seems to be the latest word in other nations. Here too the only substitute for what we ourselves have not experienced is art and literature. They have the marvelous capacity of transmitting from one nation to another despite differences in language, customs, and social structure–practical experience, the harsh national experience of many decades never tasted by the other nation. Sometimes this may save a whole nation from what is a dangerous or mistaken or plainly disastrous path, thus lessening the twists and turns of human history.

Today, from this Nobel lecture platform, I should like to emphasize this great, beneficent attribute of art.

Literature transmits condensed and irrefutable human experience in still another priceless way: from generation to generation. It thus becomes the living memory of a nation. What has faded into history it thus keeps warm and preserves in a form that defies distortion and falsehood. Thus literature, together with language, preserves and protects a nation’s soul.

(It has become fashionable in recent times to talk of the leveling of nations, and of various peoples disappearing into the melting pot of contemporary civilization. I disagree with this, but that is another matter; all that should be said here is that the disappearance of whole nations would impoverish us no less than if all people were to become identical, with the same character and the same face. Nations are the wealth of humanity, its generalized personalities. The least among them has its own special colors, and harbors within itself a special aspect of God’s design.)

But woe to the nation whose literature is cut off by the interposition of force. That is not simply a violation of “freedom of the press”; it is stopping up the nation’s heart, carving out the nation’s memory. The nation loses its memory; it loses its spiritual unity–and, despite their supposedly common language, fellow countrymen suddenly cease understanding each other. Speechless generations are born and die, having recounted nothing of themselves either to their own times or to their descendants. That such masters as Akhmatova and Zamyatin were buried behind four walls for their whole lives and condemned even to the grave to create in silence, without hearing one reverberation of what they wrote, is not only their own personal misfortune but a tragedy for the whole nation–and, too, a real threat to all nationalities.