- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

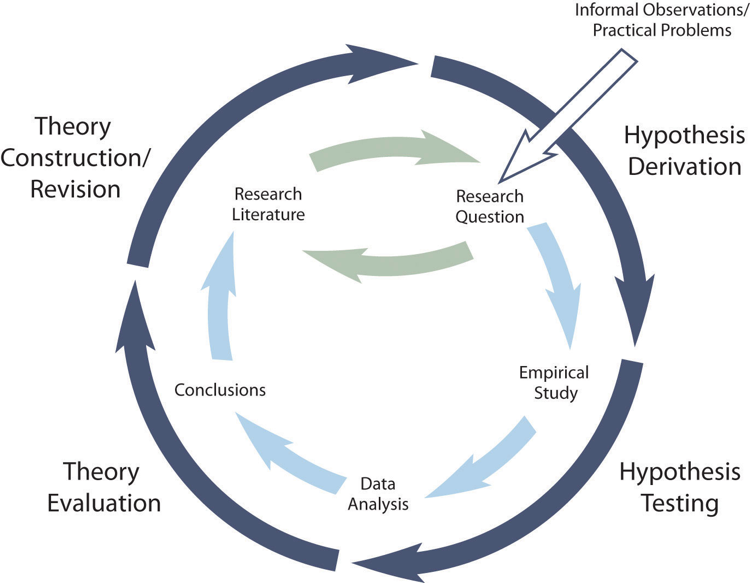

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

One-to-One Interview – Methods and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types...

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved September 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Open access

- Published: 27 June 2011

The case study approach

- Sarah Crowe 1 ,

- Kathrin Cresswell 2 ,

- Ann Robertson 2 ,

- Guro Huby 3 ,

- Anthony Avery 1 &

- Aziz Sheikh 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 11 , Article number: 100 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

798k Accesses

1122 Citations

43 Altmetric

Metrics details

The case study approach allows in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings. The value of the case study approach is well recognised in the fields of business, law and policy, but somewhat less so in health services research. Based on our experiences of conducting several health-related case studies, we reflect on the different types of case study design, the specific research questions this approach can help answer, the data sources that tend to be used, and the particular advantages and disadvantages of employing this methodological approach. The paper concludes with key pointers to aid those designing and appraising proposals for conducting case study research, and a checklist to help readers assess the quality of case study reports.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The case study approach is particularly useful to employ when there is a need to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue, event or phenomenon of interest, in its natural real-life context. Our aim in writing this piece is to provide insights into when to consider employing this approach and an overview of key methodological considerations in relation to the design, planning, analysis, interpretation and reporting of case studies.

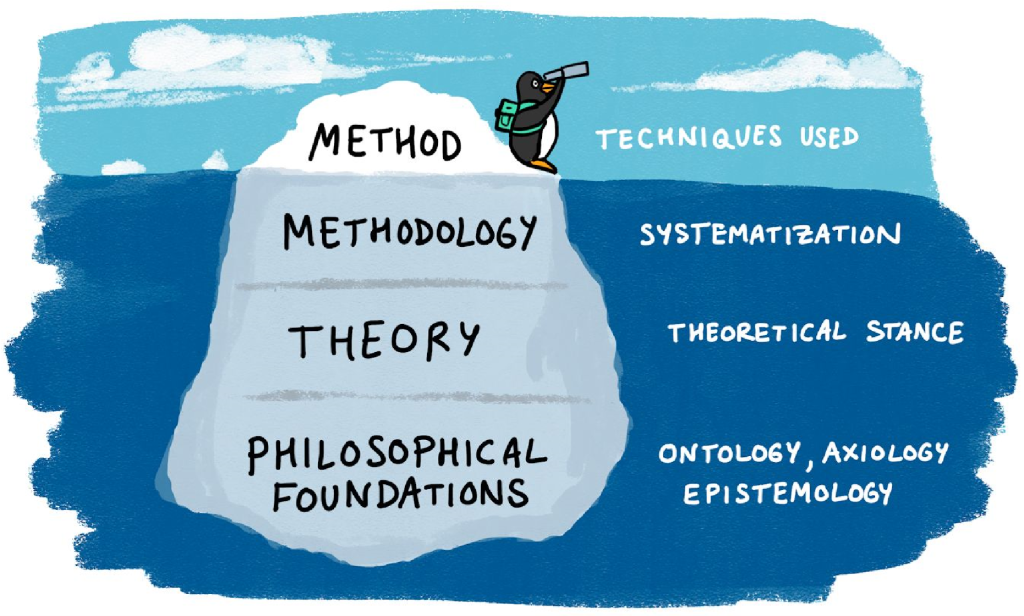

The illustrative 'grand round', 'case report' and 'case series' have a long tradition in clinical practice and research. Presenting detailed critiques, typically of one or more patients, aims to provide insights into aspects of the clinical case and, in doing so, illustrate broader lessons that may be learnt. In research, the conceptually-related case study approach can be used, for example, to describe in detail a patient's episode of care, explore professional attitudes to and experiences of a new policy initiative or service development or more generally to 'investigate contemporary phenomena within its real-life context' [ 1 ]. Based on our experiences of conducting a range of case studies, we reflect on when to consider using this approach, discuss the key steps involved and illustrate, with examples, some of the practical challenges of attaining an in-depth understanding of a 'case' as an integrated whole. In keeping with previously published work, we acknowledge the importance of theory to underpin the design, selection, conduct and interpretation of case studies[ 2 ]. In so doing, we make passing reference to the different epistemological approaches used in case study research by key theoreticians and methodologists in this field of enquiry.

This paper is structured around the following main questions: What is a case study? What are case studies used for? How are case studies conducted? What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided? We draw in particular on four of our own recently published examples of case studies (see Tables 1 , 2 , 3 and 4 ) and those of others to illustrate our discussion[ 3 – 7 ].

What is a case study?

A case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context. It is an established research design that is used extensively in a wide variety of disciplines, particularly in the social sciences. A case study can be defined in a variety of ways (Table 5 ), the central tenet being the need to explore an event or phenomenon in depth and in its natural context. It is for this reason sometimes referred to as a "naturalistic" design; this is in contrast to an "experimental" design (such as a randomised controlled trial) in which the investigator seeks to exert control over and manipulate the variable(s) of interest.

Stake's work has been particularly influential in defining the case study approach to scientific enquiry. He has helpfully characterised three main types of case study: intrinsic , instrumental and collective [ 8 ]. An intrinsic case study is typically undertaken to learn about a unique phenomenon. The researcher should define the uniqueness of the phenomenon, which distinguishes it from all others. In contrast, the instrumental case study uses a particular case (some of which may be better than others) to gain a broader appreciation of an issue or phenomenon. The collective case study involves studying multiple cases simultaneously or sequentially in an attempt to generate a still broader appreciation of a particular issue.

These are however not necessarily mutually exclusive categories. In the first of our examples (Table 1 ), we undertook an intrinsic case study to investigate the issue of recruitment of minority ethnic people into the specific context of asthma research studies, but it developed into a instrumental case study through seeking to understand the issue of recruitment of these marginalised populations more generally, generating a number of the findings that are potentially transferable to other disease contexts[ 3 ]. In contrast, the other three examples (see Tables 2 , 3 and 4 ) employed collective case study designs to study the introduction of workforce reconfiguration in primary care, the implementation of electronic health records into hospitals, and to understand the ways in which healthcare students learn about patient safety considerations[ 4 – 6 ]. Although our study focusing on the introduction of General Practitioners with Specialist Interests (Table 2 ) was explicitly collective in design (four contrasting primary care organisations were studied), is was also instrumental in that this particular professional group was studied as an exemplar of the more general phenomenon of workforce redesign[ 4 ].

What are case studies used for?

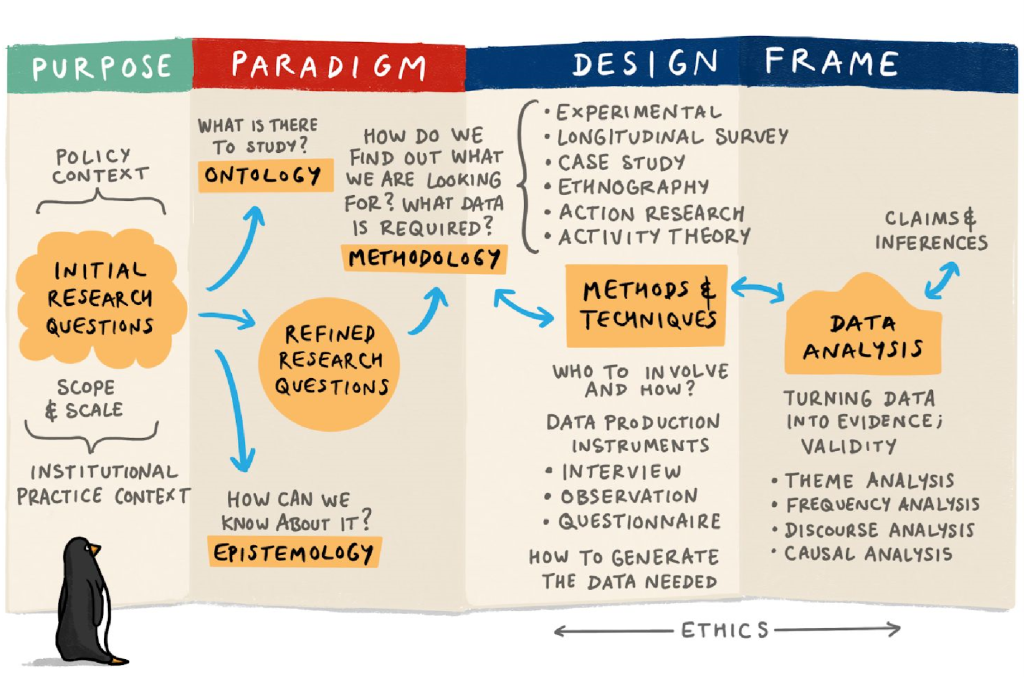

According to Yin, case studies can be used to explain, describe or explore events or phenomena in the everyday contexts in which they occur[ 1 ]. These can, for example, help to understand and explain causal links and pathways resulting from a new policy initiative or service development (see Tables 2 and 3 , for example)[ 1 ]. In contrast to experimental designs, which seek to test a specific hypothesis through deliberately manipulating the environment (like, for example, in a randomised controlled trial giving a new drug to randomly selected individuals and then comparing outcomes with controls),[ 9 ] the case study approach lends itself well to capturing information on more explanatory ' how ', 'what' and ' why ' questions, such as ' how is the intervention being implemented and received on the ground?'. The case study approach can offer additional insights into what gaps exist in its delivery or why one implementation strategy might be chosen over another. This in turn can help develop or refine theory, as shown in our study of the teaching of patient safety in undergraduate curricula (Table 4 )[ 6 , 10 ]. Key questions to consider when selecting the most appropriate study design are whether it is desirable or indeed possible to undertake a formal experimental investigation in which individuals and/or organisations are allocated to an intervention or control arm? Or whether the wish is to obtain a more naturalistic understanding of an issue? The former is ideally studied using a controlled experimental design, whereas the latter is more appropriately studied using a case study design.

Case studies may be approached in different ways depending on the epistemological standpoint of the researcher, that is, whether they take a critical (questioning one's own and others' assumptions), interpretivist (trying to understand individual and shared social meanings) or positivist approach (orientating towards the criteria of natural sciences, such as focusing on generalisability considerations) (Table 6 ). Whilst such a schema can be conceptually helpful, it may be appropriate to draw on more than one approach in any case study, particularly in the context of conducting health services research. Doolin has, for example, noted that in the context of undertaking interpretative case studies, researchers can usefully draw on a critical, reflective perspective which seeks to take into account the wider social and political environment that has shaped the case[ 11 ].

How are case studies conducted?

Here, we focus on the main stages of research activity when planning and undertaking a case study; the crucial stages are: defining the case; selecting the case(s); collecting and analysing the data; interpreting data; and reporting the findings.

Defining the case

Carefully formulated research question(s), informed by the existing literature and a prior appreciation of the theoretical issues and setting(s), are all important in appropriately and succinctly defining the case[ 8 , 12 ]. Crucially, each case should have a pre-defined boundary which clarifies the nature and time period covered by the case study (i.e. its scope, beginning and end), the relevant social group, organisation or geographical area of interest to the investigator, the types of evidence to be collected, and the priorities for data collection and analysis (see Table 7 )[ 1 ]. A theory driven approach to defining the case may help generate knowledge that is potentially transferable to a range of clinical contexts and behaviours; using theory is also likely to result in a more informed appreciation of, for example, how and why interventions have succeeded or failed[ 13 ].

For example, in our evaluation of the introduction of electronic health records in English hospitals (Table 3 ), we defined our cases as the NHS Trusts that were receiving the new technology[ 5 ]. Our focus was on how the technology was being implemented. However, if the primary research interest had been on the social and organisational dimensions of implementation, we might have defined our case differently as a grouping of healthcare professionals (e.g. doctors and/or nurses). The precise beginning and end of the case may however prove difficult to define. Pursuing this same example, when does the process of implementation and adoption of an electronic health record system really begin or end? Such judgements will inevitably be influenced by a range of factors, including the research question, theory of interest, the scope and richness of the gathered data and the resources available to the research team.

Selecting the case(s)

The decision on how to select the case(s) to study is a very important one that merits some reflection. In an intrinsic case study, the case is selected on its own merits[ 8 ]. The case is selected not because it is representative of other cases, but because of its uniqueness, which is of genuine interest to the researchers. This was, for example, the case in our study of the recruitment of minority ethnic participants into asthma research (Table 1 ) as our earlier work had demonstrated the marginalisation of minority ethnic people with asthma, despite evidence of disproportionate asthma morbidity[ 14 , 15 ]. In another example of an intrinsic case study, Hellstrom et al.[ 16 ] studied an elderly married couple living with dementia to explore how dementia had impacted on their understanding of home, their everyday life and their relationships.

For an instrumental case study, selecting a "typical" case can work well[ 8 ]. In contrast to the intrinsic case study, the particular case which is chosen is of less importance than selecting a case that allows the researcher to investigate an issue or phenomenon. For example, in order to gain an understanding of doctors' responses to health policy initiatives, Som undertook an instrumental case study interviewing clinicians who had a range of responsibilities for clinical governance in one NHS acute hospital trust[ 17 ]. Sampling a "deviant" or "atypical" case may however prove even more informative, potentially enabling the researcher to identify causal processes, generate hypotheses and develop theory.

In collective or multiple case studies, a number of cases are carefully selected. This offers the advantage of allowing comparisons to be made across several cases and/or replication. Choosing a "typical" case may enable the findings to be generalised to theory (i.e. analytical generalisation) or to test theory by replicating the findings in a second or even a third case (i.e. replication logic)[ 1 ]. Yin suggests two or three literal replications (i.e. predicting similar results) if the theory is straightforward and five or more if the theory is more subtle. However, critics might argue that selecting 'cases' in this way is insufficiently reflexive and ill-suited to the complexities of contemporary healthcare organisations.

The selected case study site(s) should allow the research team access to the group of individuals, the organisation, the processes or whatever else constitutes the chosen unit of analysis for the study. Access is therefore a central consideration; the researcher needs to come to know the case study site(s) well and to work cooperatively with them. Selected cases need to be not only interesting but also hospitable to the inquiry [ 8 ] if they are to be informative and answer the research question(s). Case study sites may also be pre-selected for the researcher, with decisions being influenced by key stakeholders. For example, our selection of case study sites in the evaluation of the implementation and adoption of electronic health record systems (see Table 3 ) was heavily influenced by NHS Connecting for Health, the government agency that was responsible for overseeing the National Programme for Information Technology (NPfIT)[ 5 ]. This prominent stakeholder had already selected the NHS sites (through a competitive bidding process) to be early adopters of the electronic health record systems and had negotiated contracts that detailed the deployment timelines.

It is also important to consider in advance the likely burden and risks associated with participation for those who (or the site(s) which) comprise the case study. Of particular importance is the obligation for the researcher to think through the ethical implications of the study (e.g. the risk of inadvertently breaching anonymity or confidentiality) and to ensure that potential participants/participating sites are provided with sufficient information to make an informed choice about joining the study. The outcome of providing this information might be that the emotive burden associated with participation, or the organisational disruption associated with supporting the fieldwork, is considered so high that the individuals or sites decide against participation.

In our example of evaluating implementations of electronic health record systems, given the restricted number of early adopter sites available to us, we sought purposively to select a diverse range of implementation cases among those that were available[ 5 ]. We chose a mixture of teaching, non-teaching and Foundation Trust hospitals, and examples of each of the three electronic health record systems procured centrally by the NPfIT. At one recruited site, it quickly became apparent that access was problematic because of competing demands on that organisation. Recognising the importance of full access and co-operative working for generating rich data, the research team decided not to pursue work at that site and instead to focus on other recruited sites.

Collecting the data

In order to develop a thorough understanding of the case, the case study approach usually involves the collection of multiple sources of evidence, using a range of quantitative (e.g. questionnaires, audits and analysis of routinely collected healthcare data) and more commonly qualitative techniques (e.g. interviews, focus groups and observations). The use of multiple sources of data (data triangulation) has been advocated as a way of increasing the internal validity of a study (i.e. the extent to which the method is appropriate to answer the research question)[ 8 , 18 – 21 ]. An underlying assumption is that data collected in different ways should lead to similar conclusions, and approaching the same issue from different angles can help develop a holistic picture of the phenomenon (Table 2 )[ 4 ].

Brazier and colleagues used a mixed-methods case study approach to investigate the impact of a cancer care programme[ 22 ]. Here, quantitative measures were collected with questionnaires before, and five months after, the start of the intervention which did not yield any statistically significant results. Qualitative interviews with patients however helped provide an insight into potentially beneficial process-related aspects of the programme, such as greater, perceived patient involvement in care. The authors reported how this case study approach provided a number of contextual factors likely to influence the effectiveness of the intervention and which were not likely to have been obtained from quantitative methods alone.

In collective or multiple case studies, data collection needs to be flexible enough to allow a detailed description of each individual case to be developed (e.g. the nature of different cancer care programmes), before considering the emerging similarities and differences in cross-case comparisons (e.g. to explore why one programme is more effective than another). It is important that data sources from different cases are, where possible, broadly comparable for this purpose even though they may vary in nature and depth.

Analysing, interpreting and reporting case studies

Making sense and offering a coherent interpretation of the typically disparate sources of data (whether qualitative alone or together with quantitative) is far from straightforward. Repeated reviewing and sorting of the voluminous and detail-rich data are integral to the process of analysis. In collective case studies, it is helpful to analyse data relating to the individual component cases first, before making comparisons across cases. Attention needs to be paid to variations within each case and, where relevant, the relationship between different causes, effects and outcomes[ 23 ]. Data will need to be organised and coded to allow the key issues, both derived from the literature and emerging from the dataset, to be easily retrieved at a later stage. An initial coding frame can help capture these issues and can be applied systematically to the whole dataset with the aid of a qualitative data analysis software package.

The Framework approach is a practical approach, comprising of five stages (familiarisation; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; mapping and interpretation) , to managing and analysing large datasets particularly if time is limited, as was the case in our study of recruitment of South Asians into asthma research (Table 1 )[ 3 , 24 ]. Theoretical frameworks may also play an important role in integrating different sources of data and examining emerging themes. For example, we drew on a socio-technical framework to help explain the connections between different elements - technology; people; and the organisational settings within which they worked - in our study of the introduction of electronic health record systems (Table 3 )[ 5 ]. Our study of patient safety in undergraduate curricula drew on an evaluation-based approach to design and analysis, which emphasised the importance of the academic, organisational and practice contexts through which students learn (Table 4 )[ 6 ].

Case study findings can have implications both for theory development and theory testing. They may establish, strengthen or weaken historical explanations of a case and, in certain circumstances, allow theoretical (as opposed to statistical) generalisation beyond the particular cases studied[ 12 ]. These theoretical lenses should not, however, constitute a strait-jacket and the cases should not be "forced to fit" the particular theoretical framework that is being employed.

When reporting findings, it is important to provide the reader with enough contextual information to understand the processes that were followed and how the conclusions were reached. In a collective case study, researchers may choose to present the findings from individual cases separately before amalgamating across cases. Care must be taken to ensure the anonymity of both case sites and individual participants (if agreed in advance) by allocating appropriate codes or withholding descriptors. In the example given in Table 3 , we decided against providing detailed information on the NHS sites and individual participants in order to avoid the risk of inadvertent disclosure of identities[ 5 , 25 ].

What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided?

The case study approach is, as with all research, not without its limitations. When investigating the formal and informal ways undergraduate students learn about patient safety (Table 4 ), for example, we rapidly accumulated a large quantity of data. The volume of data, together with the time restrictions in place, impacted on the depth of analysis that was possible within the available resources. This highlights a more general point of the importance of avoiding the temptation to collect as much data as possible; adequate time also needs to be set aside for data analysis and interpretation of what are often highly complex datasets.

Case study research has sometimes been criticised for lacking scientific rigour and providing little basis for generalisation (i.e. producing findings that may be transferable to other settings)[ 1 ]. There are several ways to address these concerns, including: the use of theoretical sampling (i.e. drawing on a particular conceptual framework); respondent validation (i.e. participants checking emerging findings and the researcher's interpretation, and providing an opinion as to whether they feel these are accurate); and transparency throughout the research process (see Table 8 )[ 8 , 18 – 21 , 23 , 26 ]. Transparency can be achieved by describing in detail the steps involved in case selection, data collection, the reasons for the particular methods chosen, and the researcher's background and level of involvement (i.e. being explicit about how the researcher has influenced data collection and interpretation). Seeking potential, alternative explanations, and being explicit about how interpretations and conclusions were reached, help readers to judge the trustworthiness of the case study report. Stake provides a critique checklist for a case study report (Table 9 )[ 8 ].

Conclusions

The case study approach allows, amongst other things, critical events, interventions, policy developments and programme-based service reforms to be studied in detail in a real-life context. It should therefore be considered when an experimental design is either inappropriate to answer the research questions posed or impossible to undertake. Considering the frequency with which implementations of innovations are now taking place in healthcare settings and how well the case study approach lends itself to in-depth, complex health service research, we believe this approach should be more widely considered by researchers. Though inherently challenging, the research case study can, if carefully conceptualised and thoughtfully undertaken and reported, yield powerful insights into many important aspects of health and healthcare delivery.

Yin RK: Case study research, design and method. 2009, London: Sage Publications Ltd., 4

Google Scholar

Keen J, Packwood T: Qualitative research; case study evaluation. BMJ. 1995, 311: 444-446.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sheikh A, Halani L, Bhopal R, Netuveli G, Partridge M, Car J, et al: Facilitating the Recruitment of Minority Ethnic People into Research: Qualitative Case Study of South Asians and Asthma. PLoS Med. 2009, 6 (10): 1-11.

Article Google Scholar

Pinnock H, Huby G, Powell A, Kielmann T, Price D, Williams S, et al: The process of planning, development and implementation of a General Practitioner with a Special Interest service in Primary Care Organisations in England and Wales: a comparative prospective case study. Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO). 2008, [ http://www.sdo.nihr.ac.uk/files/project/99-final-report.pdf ]

Robertson A, Cresswell K, Takian A, Petrakaki D, Crowe S, Cornford T, et al: Prospective evaluation of the implementation and adoption of NHS Connecting for Health's national electronic health record in secondary care in England: interim findings. BMJ. 2010, 41: c4564-

Pearson P, Steven A, Howe A, Sheikh A, Ashcroft D, Smith P, the Patient Safety Education Study Group: Learning about patient safety: organisational context and culture in the education of healthcare professionals. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2010, 15: 4-10. 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009052.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

van Harten WH, Casparie TF, Fisscher OA: The evaluation of the introduction of a quality management system: a process-oriented case study in a large rehabilitation hospital. Health Policy. 2002, 60 (1): 17-37. 10.1016/S0168-8510(01)00187-7.

Stake RE: The art of case study research. 1995, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Sheikh A, Smeeth L, Ashcroft R: Randomised controlled trials in primary care: scope and application. Br J Gen Pract. 2002, 52 (482): 746-51.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

King G, Keohane R, Verba S: Designing Social Inquiry. 1996, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Doolin B: Information technology as disciplinary technology: being critical in interpretative research on information systems. Journal of Information Technology. 1998, 13: 301-311. 10.1057/jit.1998.8.

George AL, Bennett A: Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. 2005, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Eccles M, the Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG): Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implementation Science. 2006, 1: 1-8. 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Netuveli G, Hurwitz B, Levy M, Fletcher M, Barnes G, Durham SR, Sheikh A: Ethnic variations in UK asthma frequency, morbidity, and health-service use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005, 365 (9456): 312-7.

Sheikh A, Panesar SS, Lasserson T, Netuveli G: Recruitment of ethnic minorities to asthma studies. Thorax. 2004, 59 (7): 634-

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hellström I, Nolan M, Lundh U: 'We do things together': A case study of 'couplehood' in dementia. Dementia. 2005, 4: 7-22. 10.1177/1471301205049188.

Som CV: Nothing seems to have changed, nothing seems to be changing and perhaps nothing will change in the NHS: doctors' response to clinical governance. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 2005, 18: 463-477. 10.1108/09513550510608903.

Lincoln Y, Guba E: Naturalistic inquiry. 1985, Newbury Park: Sage Publications

Barbour RS: Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?. BMJ. 2001, 322: 1115-1117. 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115.

Mays N, Pope C: Qualitative research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000, 320: 50-52. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50.

Mason J: Qualitative researching. 2002, London: Sage

Brazier A, Cooke K, Moravan V: Using Mixed Methods for Evaluating an Integrative Approach to Cancer Care: A Case Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2008, 7: 5-17. 10.1177/1534735407313395.

Miles MB, Huberman M: Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 1994, CA: Sage Publications Inc., 2

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N: Analysing qualitative data. Qualitative research in health care. BMJ. 2000, 320: 114-116. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114.

Cresswell KM, Worth A, Sheikh A: Actor-Network Theory and its role in understanding the implementation of information technology developments in healthcare. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2010, 10 (1): 67-10.1186/1472-6947-10-67.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Malterud K: Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001, 358: 483-488. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Yin R: Case study research: design and methods. 1994, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing, 2

Yin R: Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Serv Res. 1999, 34: 1209-1224.

Green J, Thorogood N: Qualitative methods for health research. 2009, Los Angeles: Sage, 2

Howcroft D, Trauth E: Handbook of Critical Information Systems Research, Theory and Application. 2005, Cheltenham, UK: Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar

Book Google Scholar

Blakie N: Approaches to Social Enquiry. 1993, Cambridge: Polity Press

Doolin B: Power and resistance in the implementation of a medical management information system. Info Systems J. 2004, 14: 343-362. 10.1111/j.1365-2575.2004.00176.x.

Bloomfield BP, Best A: Management consultants: systems development, power and the translation of problems. Sociological Review. 1992, 40: 533-560.

Shanks G, Parr A: Positivist, single case study research in information systems: A critical analysis. Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems. 2003, Naples

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/11/100/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants and colleagues who contributed to the individual case studies that we have drawn on. This work received no direct funding, but it has been informed by projects funded by Asthma UK, the NHS Service Delivery Organisation, NHS Connecting for Health Evaluation Programme, and Patient Safety Research Portfolio. We would also like to thank the expert reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback. Our thanks are also due to Dr. Allison Worth who commented on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Primary Care, The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Sarah Crowe & Anthony Avery

Centre for Population Health Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Kathrin Cresswell, Ann Robertson & Aziz Sheikh

School of Health in Social Science, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sarah Crowe .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AS conceived this article. SC, KC and AR wrote this paper with GH, AA and AS all commenting on various drafts. SC and AS are guarantors.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A. et al. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 11 , 100 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Download citation

Received : 29 November 2010

Accepted : 27 June 2011

Published : 27 June 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Case Study Approach

- Electronic Health Record System

- Case Study Design

- Case Study Site

- Case Study Report

BMC Medical Research Methodology

ISSN: 1471-2288

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Prev Med

Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research

Vishnu renjith.

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Royal College of Surgeons Ireland - Bahrain (RCSI Bahrain), Al Sayh Muharraq Governorate, Bahrain

Renjulal Yesodharan

1 Department of Mental Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Judith A. Noronha

2 Department of OBG Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Elissa Ladd

3 School of Nursing, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, USA

Anice George

4 Department of Child Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate robust evidence about important issues in the fields of medicine and healthcare. Qualitative research has ample possibilities within the arena of healthcare research. This article aims to inform healthcare professionals regarding qualitative research, its significance, and applicability in the field of healthcare. A wide variety of phenomena that cannot be explained using the quantitative approach can be explored and conveyed using a qualitative method. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research. The greatest strength of the qualitative research approach lies in the richness and depth of the healthcare exploration and description it makes. In health research, these methods are considered as the most humanistic and person-centered way of discovering and uncovering thoughts and actions of human beings.

Introduction

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate trustworthy evidence about issues in the field of medicine and healthcare. The three principal approaches to health research are the quantitative, the qualitative, and the mixed methods approach. The quantitative research method uses data, which are measures of values and counts and are often described using statistical methods which in turn aids the researcher to draw inferences. Qualitative research incorporates the recording, interpreting, and analyzing of non-numeric data with an attempt to uncover the deeper meanings of human experiences and behaviors. Mixed methods research, the third methodological approach, involves collection and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative information with an objective to solve different but related questions, or at times the same questions.[ 1 , 2 ]

In healthcare, qualitative research is widely used to understand patterns of health behaviors, describe lived experiences, develop behavioral theories, explore healthcare needs, and design interventions.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] Because of its ample applications in healthcare, there has been a tremendous increase in the number of health research studies undertaken using qualitative methodology.[ 4 , 5 ] This article discusses qualitative research methods, their significance, and applicability in the arena of healthcare.

Qualitative Research

Diverse academic and non-academic disciplines utilize qualitative research as a method of inquiry to understand human behavior and experiences.[ 6 , 7 ] According to Munhall, “Qualitative research involves broadly stated questions about human experiences and realities, studied through sustained contact with the individual in their natural environments and producing rich, descriptive data that will help us to understand those individual's experiences.”[ 8 ]

Significance of Qualitative Research

The qualitative method of inquiry examines the 'how' and 'why' of decision making, rather than the 'when,' 'what,' and 'where.'[ 7 ] Unlike quantitative methods, the objective of qualitative inquiry is to explore, narrate, and explain the phenomena and make sense of the complex reality. Health interventions, explanatory health models, and medical-social theories could be developed as an outcome of qualitative research.[ 9 ] Understanding the richness and complexity of human behavior is the crux of qualitative research.

Differences between Quantitative and Qualitative Research

The quantitative and qualitative forms of inquiry vary based on their underlying objectives. They are in no way opposed to each other; instead, these two methods are like two sides of a coin. The critical differences between quantitative and qualitative research are summarized in Table 1 .[ 1 , 10 , 11 ]

Differences between quantitative and qualitative research

| Areas | Quantitative Research | Qualitative Research |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of reality | Assumes there is a single reality. | Assumes existence of dynamic and multiple reality. |

| Goal | Test and confirm hypotheses. | Explore and understand phenomena. |

| Data collection methods | Highly structured methods like questionnaires, inventories and scales. | Semi structured like in-depth interviews, observations and focus group discussions. |

| Design | Predetermined and rigid design. | Flexible and emergent design. |

| Reasoning | Deductive process to test the hypothesis. | Primarily inductive to develop the theory or hypothesis. |

| Focus | Concerned with the outcomes and prediction of the causal relationships. | Concerned primarily with process, rather than outcomes or products. |

| Sampling | Rely largely on random sampling methods. | Based on purposive sampling methods. |

| Sample size determination | Involves a-priori sample size calculation. | Collect data until data saturation is achieved. |

| Sample size | Relatively large. | Small sample size but studied in-depth. |

| Data analysis | Variable based and use of statistical or mathematical methods. | Case based and use non statistical descriptive or interpretive methods. |

Qualitative Research Questions and Purpose Statements

Qualitative questions are exploratory and are open-ended. A well-formulated study question forms the basis for developing a protocol, guides the selection of design, and data collection methods. Qualitative research questions generally involve two parts, a central question and related subquestions. The central question is directed towards the primary phenomenon under study, whereas the subquestions explore the subareas of focus. It is advised not to have more than five to seven subquestions. A commonly used framework for designing a qualitative research question is the 'PCO framework' wherein, P stands for the population under study, C stands for the context of exploration, and O stands for the outcome/s of interest.[ 12 ] The PCO framework guides researchers in crafting a focused study question.

Example: In the question, “What are the experiences of mothers on parenting children with Thalassemia?”, the population is “mothers of children with Thalassemia,” the context is “parenting children with Thalassemia,” and the outcome of interest is “experiences.”

The purpose statement specifies the broad focus of the study, identifies the approach, and provides direction for the overall goal of the study. The major components of a purpose statement include the central phenomenon under investigation, the study design and the population of interest. Qualitative research does not require a-priori hypothesis.[ 13 , 14 , 15 ]

Example: Borimnejad et al . undertook a qualitative research on the lived experiences of women suffering from vitiligo. The purpose of this study was, “to explore lived experiences of women suffering from vitiligo using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach.” [ 16 ]

Review of the Literature

In quantitative research, the researchers do an extensive review of scientific literature prior to the commencement of the study. However, in qualitative research, only a minimal literature search is conducted at the beginning of the study. This is to ensure that the researcher is not influenced by the existing understanding of the phenomenon under the study. The minimal literature review will help the researchers to avoid the conceptual pollution of the phenomenon being studied. Nonetheless, an extensive review of the literature is conducted after data collection and analysis.[ 15 ]

Reflexivity

Reflexivity refers to critical self-appraisal about one's own biases, values, preferences, and preconceptions about the phenomenon under investigation. Maintaining a reflexive diary/journal is a widely recognized way to foster reflexivity. According to Creswell, “Reflexivity increases the credibility of the study by enhancing more neutral interpretations.”[ 7 ]

Types of Qualitative Research Designs

The qualitative research approach encompasses a wide array of research designs. The words such as types, traditions, designs, strategies of inquiry, varieties, and methods are used interchangeably. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research.[ 1 , 7 , 10 ]

Narrative research

Narrative research focuses on exploring the life of an individual and is ideally suited to tell the stories of individual experiences.[ 17 ] The purpose of narrative research is to utilize 'story telling' as a method in communicating an individual's experience to a larger audience.[ 18 ] The roots of narrative inquiry extend to humanities including anthropology, literature, psychology, education, history, and sociology. Narrative research encompasses the study of individual experiences and learning the significance of those experiences. The data collection procedures include mainly interviews, field notes, letters, photographs, diaries, and documents collected from one or more individuals. Data analysis involves the analysis of the stories or experiences through “re-storying of stories” and developing themes usually in chronological order of events. Rolls and Payne argued that narrative research is a valuable approach in health care research, to gain deeper insight into patient's experiences.[ 19 ]

Example: Karlsson et al . undertook a narrative inquiry to “explore how people with Alzheimer's disease present their life story.” Data were collected from nine participants. They were asked to describe about their life experiences from childhood to adulthood, then to current life and their views about the future life. [ 20 ]

Phenomenological research

Phenomenology is a philosophical tradition developed by German philosopher Edmond Husserl. His student Martin Heidegger did further developments in this methodology. It defines the 'essence' of individual's experiences regarding a certain phenomenon.[ 1 ] The methodology has its origin from philosophy, psychology, and education. The purpose of qualitative research is to understand the people's everyday life experiences and reduce it into the central meaning or the 'essence of the experience'.[ 21 , 22 ] The unit of analysis of phenomenology is the individuals who have had similar experiences of the phenomenon. Interviews with individuals are mainly considered for the data collection, though, documents and observations are also useful. Data analysis includes identification of significant meaning elements, textural description (what was experienced), structural description (how was it experienced), and description of 'essence' of experience.[ 1 , 7 , 21 ] The phenomenological approach is further divided into descriptive and interpretive phenomenology. Descriptive phenomenology focuses on the understanding of the essence of experiences and is best suited in situations that need to describe the lived phenomenon. Hermeneutic phenomenology or Interpretive phenomenology moves beyond the description to uncover the meanings that are not explicitly evident. The researcher tries to interpret the phenomenon, based on their judgment rather than just describing it.[ 7 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]

Example: A phenomenological study conducted by Cornelio et al . aimed at describing the lived experiences of mothers in parenting children with leukemia. Data from ten mothers were collected using in-depth semi-structured interviews and were analyzed using Husserl's method of phenomenology. Themes such as “pivotal moment in life”, “the experience of being with a seriously ill child”, “having to keep distance with the relatives”, “overcoming the financial and social commitments”, “responding to challenges”, “experience of faith as being key to survival”, “health concerns of the present and future”, and “optimism” were derived. The researchers reported the essence of the study as “chronic illness such as leukemia in children results in a negative impact on the child and on the mother.” [ 25 ]

Grounded Theory Research

Grounded theory has its base in sociology and propagated by two sociologists, Barney Glaser, and Anselm Strauss.[ 26 ] The primary purpose of grounded theory is to discover or generate theory in the context of the social process being studied. The major difference between grounded theory and other approaches lies in its emphasis on theory generation and development. The name grounded theory comes from its ability to induce a theory grounded in the reality of study participants.[ 7 , 27 ] Data collection in grounded theory research involves recording interviews from many individuals until data saturation. Constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling, theoretical coding, and theoretical saturation are unique features of grounded theory research.[ 26 , 27 , 28 ] Data analysis includes analyzing data through 'open coding,' 'axial coding,' and 'selective coding.'[ 1 , 7 ] Open coding is the first level of abstraction, and it refers to the creation of a broad initial range of categories, axial coding is the procedure of understanding connections between the open codes, whereas selective coding relates to the process of connecting the axial codes to formulate a theory.[ 1 , 7 ] Results of the grounded theory analysis are supplemented with a visual representation of major constructs usually in the form of flow charts or framework diagrams. Quotations from the participants are used in a supportive capacity to substantiate the findings. Strauss and Corbin highlights that “the value of the grounded theory lies not only in its ability to generate a theory but also to ground that theory in the data.”[ 27 ]

Example: Williams et al . conducted a grounded theory research to explore the nature of relationship between the sense of self and the eating disorders. Data were collected form 11 women with a lifetime history of Anorexia Nervosa and were analyzed using the grounded theory methodology. Analysis led to the development of a theoretical framework on the nature of the relationship between the self and Anorexia Nervosa. [ 29 ]

Ethnographic research

Ethnography has its base in anthropology, where the anthropologists used it for understanding the culture-specific knowledge and behaviors. In health sciences research, ethnography focuses on narrating and interpreting the health behaviors of a culture-sharing group. 'Culture-sharing group' in an ethnography represents any 'group of people who share common meanings, customs or experiences.' In health research, it could be a group of physicians working in rural care, a group of medical students, or it could be a group of patients who receive home-based rehabilitation. To understand the cultural patterns, researchers primarily observe the individuals or group of individuals for a prolonged period of time.[ 1 , 7 , 30 ] The scope of ethnography can be broad or narrow depending on the aim. The study of more general cultural groups is termed as macro-ethnography, whereas micro-ethnography focuses on more narrowly defined cultures. Ethnography is usually conducted in a single setting. Ethnographers collect data using a variety of methods such as observation, interviews, audio-video records, and document reviews. A written report includes a detailed description of the culture sharing group with emic and etic perspectives. When the researcher reports the views of the participants it is called emic perspectives and when the researcher reports his or her views about the culture, the term is called etic.[ 7 ]

Example: The aim of the ethnographic study by LeBaron et al . was to explore the barriers to opioid availability and cancer pain management in India. The researchers collected data from fifty-nine participants using in-depth semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and document review. The researchers identified significant barriers by open coding and thematic analysis of the formal interview. [ 31 ]

Historical research

Historical research is the “systematic collection, critical evaluation, and interpretation of historical evidence”.[ 1 ] The purpose of historical research is to gain insights from the past and involves interpreting past events in the light of the present. The data for historical research are usually collected from primary and secondary sources. The primary source mainly includes diaries, first hand information, and writings. The secondary sources are textbooks, newspapers, second or third-hand accounts of historical events and medical/legal documents. The data gathered from these various sources are synthesized and reported as biographical narratives or developmental perspectives in chronological order. The ideas are interpreted in terms of the historical context and significance. The written report describes 'what happened', 'how it happened', 'why it happened', and its significance and implications to current clinical practice.[ 1 , 10 ]

Example: Lubold (2019) analyzed the breastfeeding trends in three countries (Sweden, Ireland, and the United States) using a historical qualitative method. Through analysis of historical data, the researcher found that strong family policies, adherence to international recommendations and adoption of baby-friendly hospital initiative could greatly enhance the breastfeeding rates. [ 32 ]

Case study research

Case study research focuses on the description and in-depth analysis of the case(s) or issues illustrated by the case(s). The design has its origin from psychology, law, and medicine. Case studies are best suited for the understanding of case(s), thus reducing the unit of analysis into studying an event, a program, an activity or an illness. Observations, one to one interviews, artifacts, and documents are used for collecting the data, and the analysis is done through the description of the case. From this, themes and cross-case themes are derived. A written case study report includes a detailed description of one or more cases.[ 7 , 10 ]

Example: Perceptions of poststroke sexuality in a woman of childbearing age was explored using a qualitative case study approach by Beal and Millenbrunch. Semi structured interview was conducted with a 36- year mother of two children with a history of Acute ischemic stroke. The data were analyzed using an inductive approach. The authors concluded that “stroke during childbearing years may affect a woman's perception of herself as a sexual being and her ability to carry out gender roles”. [ 33 ]

Sampling in Qualitative Research

Qualitative researchers widely use non-probability sampling techniques such as purposive sampling, convenience sampling, quota sampling, snowball sampling, homogeneous sampling, maximum variation sampling, extreme (deviant) case sampling, typical case sampling, and intensity sampling. The selection of a sampling technique depends on the nature and needs of the study.[ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ] The four widely used sampling techniques are convenience sampling, purposive sampling, snowball sampling, and intensity sampling.

Convenience sampling

It is otherwise called accidental sampling, where the researchers collect data from the subjects who are selected based on accessibility, geographical proximity, ease, speed, and or low cost.[ 34 ] Convenience sampling offers a significant benefit of convenience but often accompanies the issues of sample representation.

Purposive sampling

Purposive or purposeful sampling is a widely used sampling technique.[ 35 ] It involves identifying a population based on already established sampling criteria and then selecting subjects who fulfill that criteria to increase the credibility. However, choosing information-rich cases is the key to determine the power and logic of purposive sampling in a qualitative study.[ 1 ]

Snowball sampling