Home — Essay Samples — Economics — Indian Economy — Impact Of Covid-19 On The Indian Economy

Impact of Covid-19 on The Indian Economy

- Categories: Covid 19 India Indian Economy

About this sample

Words: 1417 |

Published: Feb 8, 2022

Words: 1417 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Table of contents

Introduction.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_India

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341266520_Effect_of_COVID-19_on_the_Indian_Economy_and_Supply_Chain

- https://etinsights.et-edge.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/KPMG-REPORT-compressed.pdf

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health Geography & Travel Economics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 456 words

3 pages / 1286 words

6 pages / 2505 words

3 pages / 1364 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Indian Economy

The Vaishya caste is one of the four major social classes in Hinduism, known as Varnas, and is traditionally associated with commerce, agriculture, and trade. The Vaishya caste plays a crucial role in Indian society, as it is [...]

Credit control is absignificant tool used by Reserve Bank of India. It is an important weapon of the monetary policy used to control demand and supply of money which is also termed as liquidity in the economy. Administers of the [...]

The Indian financial system can be broadly classified into the formal (organized) financial system and the informal (unorganized) financial system. The formal financial system comes under the purview of the Ministry of [...]

India is considered as the fourth largest pharmaceutical producer by volume and as the thirteenth largest by value. At the meantime, the country is also a major drug exporter and huge supplier across the globe in which its [...]

Illegal wildlife trade across the world is worth billions of dollars each year and is one of the major threats to the survival of our most iconic species in the wildlife such as Rhinos, Tigers and Elephants. According to U.S., [...]

In this assignment I will be considering what Brexit is and what impact it has had on financial services as well as financial institutions. This will be followed up by some recommendation on how the Bank of England and the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Publications

- Ask a question

- Research Hub

- Submit Evidence

How has Covid-19 affected India’s economy?

India has been hit hard by the pandemic, particularly during the second wave of the virus in the spring of 2021. the sharp drop in gdp is the largest in the country’s history, but this may still underestimate the economic damage experienced by the poorest households..

From April to June 2020, India’s GDP dropped by a massive 24.4%. According to the latest national income estimates , in the second quarter of the 2020/21 financial year (July to September 2020), the economy contracted by a further 7.4%. The recovery in the third and fourth quarters (October 2020 to March 2021) was still weak, with GDP rising 0.5% and 1.6%, respectively. This means that the overall rate of contraction in India was (in real terms) 7.3% for the whole 2020/21 financial year.

In the post-independence period, India's national income has declined only four times before 2020 – in 1958, 1966, 1973 and 1980 – with the largest drop being in 1980 (5.2%). This means that 2020/21 is the worst year in terms of economic contraction in the country’s history, and much worse than the overall contraction in the world (Figure 1).

The decline is solely responsible for reversing the trend in global inequality, which had been falling but has now started to rise again after three decades ( Deaton, 2021 ; Ferreira, 2021 ).

Figure 1: Economic contraction in India and the world during Covid-19

Source: world economic outlook, international monetary fund, april 2021. note: the gross domestic product (gdp) per capita, constant prices is measured at purchase power parity; 2017 international dollars. the gdp per capita of each series is normalised to 100 in 2011. we use population-weighted average as the aggregation method., what do the main macroeconomic indicators tell us about india’s economy during the pandemic.

While economies worldwide have been hit hard, India has suffered one of the largest contractions. During the 2020/21 financial year, the rates of decline in GDP for the world were 3.3% and 2.2% for emerging market and developing economies. Table 1 summarises macroeconomic indicators for India, along with a reference group of comparable countries and the world. The fact that India’s growth rate in 2019 was among the highest makes the drop due to Covid-19 even more noticeable.

Comparing national unemployment rates in 2020, India’s rate of 7.1% indicates that it has performed relatively poorly – both in terms of the world average and compared with a set of reference group economies with similar per capita incomes. Unemployment rates were more muted within the reference group economies and were also kept low by generous labour market policies to keep people in work.

Despite the scale of the pandemic, additional budgetary allocation to various social safety measures has been relatively low in India compared with other countries. Although the country might look comparable to the reference group in non-health sector measures, the additional health sector fiscal measures are less than half those in the reference group. More worryingly, the Indian government's announced allocation in the 2021 budget for such measures does not show an increase, once inflation is taken into account.

Table 1: Summary of key macroeconomic indicators

| GDP at constant prices 2019 (% change) | 4.0% | 3.6% | 2.8% |

| GDP at constant prices 2020 (% change) | -7.3% | -2.2% | -3.3% |

| Unemployment rate 2019 (% of total labour force) | 5.3% | 5.5% | 5.4% |

| Unemployment rate 2020 (% of total labour force) | 7.1% | 6.4% | 6.5% |

| Above-the-line additional health sector fiscal measures in response to Covid-19 (% of GDP) | 0.4% | 0.9% | 1.2% |

| Above-the-line additional non-health sector fiscal measures in response to Covid-19 (% of GDP) | 3.0% | 2.8% | 7.8% |

Source: Data on gross domestic product, constant prices (percentage change) is obtained from the World Economic Outlook Database April 2021, International Monetary Fund . Note: India’s GDP contraction is 8%, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and 7.3% from recent national estimates. Unemployment rates (for youth, adults: 15+) are ILO-modelled estimates as of November 2021 and are obtained from ILOSTAT, International Labour Organization (ILO) and World Bank . Fiscal measures are obtained from Fiscal Monitor Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic as of April 2021, International Monetary Fund . The ‘reference group’ refers to the closest peer group statistic under which India falls. The reference group for GDP per capita is the emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) classification by the IMF. The reference group for the unemployment rate is the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) classification by the World Bank. The reference group for the fiscal measures is the EMDEs classification by the IMF. See Ghatak and Raghavan (forthcoming) for a comparison of India’s economic and health performance against the reference group.

How has covid-19 changed income, consumption, poverty and unemployment in india.

While the macroeconomic statistics provide a snapshot of India’s economic position, they hide the large and unequal effects on households and workers within the country.

Both wealth and income inequality has been on the rise in India ( Ghatak, 2021 ). Estimates suggest that in 2020, the top 1% of the population held 42.5% of the total wealth, while the bottom 50% had only 2.5% of the total wealth ( Oxfam, 2020 ). Post-pandemic, the number of poor in India is projected to have more than doubled and the number of people in the middle class to have fallen by a third ( Kochhar, 2021 ).

During India’s first stringent national lockdown between April and May 2020, individual income dropped by approximately 40%. The bottom decile of households lost three months’ worth of income ( Azim Premji University, 2021 ; Beyer et al, 2021 ).

Microdata from the largest private survey in India, CMIE’s ‘Consumer Pyramids Household Survey’ (CPHS), show that per capita consumption spending dropped by more than GDP, and did not return to pre-lockdown levels during periods of reduced social distancing. Average per capita consumption spending continued to be over 20% lower after the first lockdown (in August 2020 compared with August 2019), and remained 15% lower year-on-year by the end of 2020.

Official poverty data are unavailable, and the CPHS data come with a caveat of ‘top’ and ‘bottom exclusions’. For example, official statistics show a rural headcount ratio of 35% in 2017/18 ( Subramanian, 2019 ). But the CPHS data estimate it at 25%, which suggests exclusions at the lower end of the consumption distribution ( Dreze and Somanchi, 2021 ).

Despite these statistical concerns, the CPHS does provide consumption numbers for a large sample of individuals, which can provide insights into changes in consumption levels arising from the pandemic.

Table 2 reports the percentage of people who have monthly consumption expenditure below different cut-off values. The different cut-offs encompass the official poverty lines (which, in any case, have been considered too low by some commentators). The current rural poverty line is set at 1,600 rupees (£15.50) per month or over, and the urban poverty line is 2,400 rupees per month (£23.37) or over.

Based on the latest CPHS data, rural poverty increased by 9.3 percentage points and urban poverty by over 11.7 percentage year-on-year from December 2019 to December 2020. Earlier months of the CPHS show that rural poverty increased by 14.2 percentage points and urban poverty by 18.1 percentage points. Yet the actual increase in poverty due to Covid-19 is likely to be higher than what the CPHS data suggest, as indicated by other surveys .

Table 2: Percentage of individuals by monthly consumption expenditure

| Rs 1,000 or below | 6.0 | 9.0 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 7.5 | 10.9 |

| Rs 1,600 or below | 23.5 | 31.6 | 14.5 | 21.7 | ||

| Rs 2,000 or below | 38.3 | 48.3 | 25.7 | 35.7 | 44.4 | 55.2 |

| Rs 2,400 or below | 52.1 | 62.6 | 59.0 | 69.7 | ||

| Sample size | 433,021 | 499,879 | 278,759 | 331,809 | 154,262 | 168,070 |

| Rs 1,000 or below | 5.0 | 10.0 | 2.3 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 12.5 |

| Rs 1,600 or below | 21.0 | 33.6 | 12.0 | 22.5 | ||

| Rs 2,000 or below | 34.9 | 50.3 | 21.9 | 37.1 | 41.3 | 57.5 |

| Rs 2,400 or below | 48.2 | 64.4 | 55.5 | 71.5 | ||

| Sample size | 570592 | 477237 | 362417 | 321100 | 208175 | 156137 |

Source: Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS) for December 2019 and December 2020, and for August 2019 and August 2020. Notes: Estimates for consumption are calculated by dividing household adjusted total expenditure by household size and weighted using member level country weights. Adjusted total expenditure is the sum total of all consumption goods and services purchased by the household during a month, adjusted using weekly records. Real values are adjusted for inflation using the MOSPI CPI (IW) for urban workers and CPI (AL) for rural workers (Base 2012=100). Headcount ratio is the percentage of individuals who are below the poverty line in urban and rural areas in each year. Poverty line is the inflation-adjusted poverty line in rural areas (Rs 972 in 2011-12 prices) and urban areas (Rs 1410 in 2011-12 prices), which are adjusted to 2012 prices with the RBI CPI(AL) and CPI(IW) for 2011/12-2012/13 respectively. All figures are in December 2019 values and observations with missing regions are dropped. Despite a much larger sample in urban areas, the CPHS also underestimates mean per capita consumption in urban areas, which is likely to reflect their inability to survey high-income urban households. From the draft National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) Report on Household Consumer Expenditure for 2017-18, the CPHS estimate of mean per capita consumption in urban areas was 0.8 of the NSSO level for 2017-18. For rural areas, the CPHS estimate is 1.1 of the NSSO level.

Taking into account the general trend of reduction in poverty, an estimated 230 million people in India have fallen into poverty as a result of the first wave of the pandemic ( Azim Premji University, 2021 ).

Table 3 shows that households in the middle of the pre-Covid-19 CPHS consumption distribution saw large drops in spending after the first wave of the pandemic, helping to create a new set of people entering poverty.

The percentage of poor people in the second lowest quintile of pre-Covid-19 consumption jumped from 32% to 60% within a year. This was driven largely by rural areas, where the headcount ratio for the second quintile almost doubled.

In urban areas, the poverty line is set higher due to greater living costs and 72% of people in the second quintile of the urban income distribution were below this poverty line before the pandemic. Within a year, they were joined in urban poverty by many who had higher incomes before. Half of people in the third quintile and 29% of people in the fourth quintile fell below the poverty line after the pandemic.

This sharp rise in poverty after the first lockdown is consistent with a variety of surveys that highlighted the depth of the crisis ( Azim Premji University, 2021 ). Year-on-year urban unemployment rate jumped from 8.8% in April to June 2019 to a staggering 20.8% in April to June 2020 ( Government of India National Statistical Office, 2020 ).

Table 3: Percentage of individuals who are below the poverty line in middle quintiles of pre-Covid-19 consumption expenditure, August 2019 to August 2020

| 2 | 32 | 60 | 72 | 73 | 33 | 58 |

| 3 | 14 | 41 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 34 |

| 4 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 16 |

Source: Consumer Pyramids Household Survey (CPHS) for August 2019 and August 2020. Notes: Quintiles are based on 2019 mean per capita consumption levels for each region type. Consumption levels are calculated by dividing household adjusted total expenditure by household size and weighted using member level country weights. Adjusted total expenditure is the sum total of all consumption goods and services purchased by the household during a month, adjusted using weekly records. Real values are adjusted for inflation using the MOSPI CPI (IW) for urban workers and CPI (AL) for rural workers (Base 2012=100). All figures are in December 2019 values and observations with missing regions are dropped.

The pandemic has brought severe economic hardship, especially to young individuals who are over-represented in informal work. India has a large share of young people in its workforce and the pandemic has put them at heightened risk of long-term unemployment. This has negative impacts on lifelong earnings and employment prospects ( Machin and Manning, 1999 ).

A study by the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP at the London School of Economics) analyses the depth of continuing joblessness among younger workers in the low-income states of Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh (see Table 4, Dhingra and Kondirolli, 2021 ).

The first round of the survey randomly sampled urban workers aged 18-40 during the first lockdown quarter, finding that a majority of them who had work before the pandemic were left with no work or no pay. After the first lockdown in April to June 2020, 20% of those sampled were out of work, another 9% were employed but had zero hours of work and 81% had no work or pay at all.

Ten months on from the first lockdown quarter, 8% of the sample continued to be out of work, another 8% were working zero hours, and 40% had no work or no pay. The rate of no work or no pay was higher (at 47%) among the youngest low-income individuals (those aged 18-25 who had below median pre-Covid-19 earnings).

Table 4: Crisis labour force status of individuals who were employed pre-Covid-19: recontact sample of individuals interviewed during the first lockdown (April to June 2020) and before the second wave (January to March 2021)

| Out of work last week | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Zero hours last week | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Not paid | 0.70 | 0.29 | 0.32 |

| No work/Zero hours/Not paid | 0.81 | 0.40 | 0.47 |

| Sample Size | 3201 | 3201 | 542 |

Source: CEP-LSE Survey 2020 and 2021. Note: Out of work last week and zero hours last week are indicators for individuals who were unemployed in the week preceding the survey and employed but working zero hours in the week before the survey respectively. Not paid is an indicator for individuals who received no pay in April 2020 in the column of April to June 2020 and those who received no pay during January to March 2021 in all other columns. Median earnings are constructed using average earnings in January and February 2020. 18-25 refers to individuals who are between 18 to 25 years of age at the time of the first survey.

The recovery after the first wave was too muted to get many young Indian workers back into employment. For example, rural migrants continued to be reluctant to return to work in urban areas even before the second wave hit ( Imbert, 2021 ). And the second wave, which started in mid-February and appears to be flattening out in June 2021, heightened these risks of long-term unemployment by increasing the spells of economic inactivity.

What do public health indicators reveal about the impact of Covid-19 on India’s economy?

To avoid another livelihood crisis, India turned to local lockdowns during the second wave of the pandemic. Before the second wave, India’s public health performance (in terms of confirmed cases and confirmed deaths), while not the best, was ahead of several reference group countries. But the second wave has made India’s position significantly worse. The total confirmed cases per million now are comparable to those in the rest the world and the rate of vaccination is lower in India.

While death rates seem lower in India, there is massive underreporting. After accounting for the underreporting within official statistics, India’s total confirmed cases and deaths might exceed that of the rest of the world by a large margin (Gamio and Glanz, 2021).

In the conservative scenario, the total confirmed cases per million are about 13 times larger than in the rest of the world, and the total confirmed deaths per million are about 85% of that in the rest of the world. In the worst-case scenario, India is far behind the rest of the world.

There is an important caveat: while the focus of this article is on India, underreporting of Covid-19 cases and deaths is prevalent globally ( Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, 2021 ).

How has India fared so far?

More than a year has passed since India’s first national lockdown was announced. There was talk of a trade-off between lives and livelihoods when the Covid-19 crisis erupted last year. As India struggles in the second wave, it is clear that the country did poorly in both dimensions.

While India’s policy response was strong in terms of some aspects of lockdown stringency, it was ineffective in dealing with both the public health and economic aspects of the crisis. What’s more, it failed to limit the damaging impact of the crisis on the most vulnerable sections of the population.

Where can I find out more?

- State of working in India 2021 : Report from Azim Premji University’s Centre for Sustainable Employment on the effects of Covid-19 on jobs, incomes, inequality and poverty.

- City of dreams no more – The impact of Covid-19 on urban workers in India: Briefings from the Centre for Economic Performance.

- India needs a second wave of relief measures : Jean Drèze discusses the humanitarian and economic case for further support.

- Covid-19 articles from Debraj Ray .

- India COVID-19 chartbook : A series of charts on the effects of the pandemic in India from HSBC Global Research.

- India’s already-stressed rural economy is getting battered by the second wave of Covid-19 : Rohit Inani examines the crisis in India and calls for urgent relief measures.

Who are experts on this question?

- Amit Basole , Azim Premji University

- Swati Dhingra , LSE

- Maitreesh Ghatak , LSE

- Debraj Ray , New York University

- S. Subramanian , Independent Researcher

- Sanchari Roy , King's College London

Authors: Swati Dhingra and Maitreesh Ghatak

Swati thanks the erc for starting grant 760037. the authors would like to thank ramya raghavan and fjolla kondirolli for research assistance, photo by shubhangee vyas on unsplash.

- Swati Dhingra LSE View Profile

- Maitreesh Ghatak LSE View Profile

- News Ideas for the UK: election economics international week

- Prices & interest rates What are the future prospects for UK inflation?

- Trade & supply chains How is India’s trade landscape shaping up for the future?

- Economy & Politics ›

Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) on the Indian economy - statistics & facts

After reporting its first case in late January 2020 in the southern state of Kerala, India introduced rigorous airport screenings for the coronavirus (COVID-19). The following weeks saw a quick succession of events leading to a suspension of all travel in and out of the country by March 22 that year. While infections continued to increase during this period, Indians were now confined to their homes to contain the spread of the virus. The announcement did not come without chaos – it created widespread panic, specifically among lower classes of society including farmers and migrant workers who were left stranded and jobless overnight from their faraway homes and no mode of transport. Despite the government announcing a relief package of 1.7 trillion rupees , it was clear that a large portion of the country’s population was going to be scouring for livelihoods. Economists slashed GDP rates for the foreseeable future due to the obvious impact of the lockdown. However, it was also estimated that the country might bounce back quickly because its industry composition, with unorganized markets being largely dominant. Losses from organized sectors amounted to an estimated nine trillion rupees in late March, projected to increase with the prolonging of the lockdown. Unsurprisingly, the most affected industries included services and manufacturing, specifically travel & tourism, financial services, mining and construction, with declining rates of up to 23 percent between April and June 2020. Towards the end of 2020, however, India saw some semblance of recovery across certain sectors. This was a result of easing restrictions, controlled infection rates and the festive season between October and November 2020. The pandemic came with uncertainty and implications on all aspects of business across the world. Despite India being ahead of most countries in being able to implement work-from-home measures, specifically in white collar work, job and earning deficits , along with instability in prices was expected. The months of the lockdown resulted in the free fall of employment, which slowly stabilized after the economy steadied in most parts of the country. Segments including consumer retail expected to see sharp falls ranging between three and 23 percent depending on the market. For the big players across segments, this meant operating at less than full capacity to keep afloat. For small businesses , however, it depended on how long they could ride out the storm. Overall, the pandemic changed daily lifestyles drastically . Economic activity started to take a hit yet again since March 2021, as the country faced its second wave of the pandemic . As a result, GDP forecasts were expected to fall, putting losses at over 38 billion U.S. dollars if local lockdowns continued till June 2021. Unprecedented numbers in terms of infections and deaths recorded across the country led to another set of lockdowns in some parts, burdening the healthcare system in the midst of government controversy. International aid in the form of oxygen cylinders, PPE kits, ventilators along with funding was being sent from various countries to what looked like a dire situation. This text provides general information. Statista assumes no liability for the information given being complete or correct. Due to varying update cycles, statistics can display more up-to-date data than referenced in the text. Show more - Description Published by Statista Research Department , Dec 19, 2023

Key insights

Detailed statistics

Estimated quarterly impact from COVID-19 on India's GDP FY 2020-2022

Estimated cost due to COVID-19 on economy in India 2020

Value of government aid to combat COVID-19 in India April 2020

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Estimated economic impact from COVID-19 on services in India Q2 2020-Q3 2021

Key Economic Indicators

Estimated economic impact from COVID-19 on industry in India 2020

COVID-19 impact on labor participation rate in India 2020-2022

Further recommended statistics

Key indicators.

- Basic Statistic Estimated quarterly impact from COVID-19 on India's GDP FY 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on estimated income group in India 2021, by type

- Premium Statistic Estimated cost due to COVID-19 on economy in India 2020

- Premium Statistic Estimated economic cost of Maharashtra COVID-19 lockdown India 2021, by sector

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on GDP forecast India FY 2021, by agency

- Premium Statistic Impact from COVID-19 on India's exports 2021, by commodity

- Premium Statistic Impact from COVID-19 on India's imports 2022, by commodity

Estimated quarterly impact from COVID-19 on India's GDP FY 2020-2022

Estimated quarterly impact from the coronavirus (COVID-19) on India's GDP growth in financial year 2020 to 2022

COVID-19 impact on estimated income group in India 2021, by type

Coronavirus (COVID-19) impact on estimated income group across India as of April 2021, by type (in millions)

Estimated cost of the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown on the Indian economy in 2020 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Estimated economic cost of Maharashtra COVID-19 lockdown India 2021, by sector

Estimated cost of the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown in Maharashtra on the Indian economy in April 2021, by sector (in billion Indian rupees)

COVID-19 impact on GDP forecast India FY 2021, by agency

Impact from the coronavirus (COVID-19) on India's GDP growth forecast in financial year 2021, by agency

Impact from COVID-19 on India's exports 2021, by commodity

Impact from the coronavirus (COVID-19) on exports from India in January 2021, by commodity group

Impact from COVID-19 on India's imports 2022, by commodity

Impact from the coronavirus (COVID-19) on major imports into India in April 2022, by commodity group

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on rural and urban employment India 2020, by type

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on unemployment rate in India 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on jobs in India 2020, by age group

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on number of people employed in India 2020-2021

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on labor participation rate in India 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic Employment rate of urban women India 2016-2021

COVID-19 impact on rural and urban employment India 2020, by type

Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) on rural and urban employment across India in 2020, by type

COVID-19 impact on unemployment rate in India 2020-2022

Impact on unemployment rate due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown in India from January 2020 to May 2022

COVID-19 impact on jobs in India 2020, by age group

Impact on job loss and gain due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown in India between April and July 2020, by age group (in millions)

COVID-19 impact on number of people employed in India 2020-2021

Impact on number of people employed during the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown in India between May 2020 and January 2021 (in millions)

Impact on labor participation due to the coronavirus pandemic in India between 2020 and 2022

Employment rate of urban women India 2016-2021

Employment rate of urban women in India from March 2016 to February 2021

- Premium Statistic Size of organized market India FY 2019, by sector

- Basic Statistic Estimated economic impact from COVID-19 on industry in India 2020

- Basic Statistic Estimated economic impact from COVID-19 on services in India Q2 2020-Q3 2021

- Premium Statistic Estimated economic impact from COVID-19 in India 2020 by market

- Premium Statistic Impact of COVID-19 on corporate revenues in India Q1-Q2 2020, by sector

- Premium Statistic Problems faced by business due to COVID-19 in India 2020

- Premium Statistic COVID-19 impact on start-up funding in India 2020

Size of organized market India FY 2019, by sector

Size of the organized market across India in financial year 2019, by sector (in billion Indian rupees)

Estimated impact from the coronavirus (COVID-19) on the industry sector in India from April to December 2020, by type

Estimated impact from the coronavirus (COVID-19) on the service sector in India from 2nd quarter 2020 to 3rd quarter 2021, by type

Estimated economic impact from COVID-19 in India 2020 by market

Estimated impact from the coronavirus (COVID-19) on India in 2020, by market

Impact of COVID-19 on corporate revenues in India Q1-Q2 2020, by sector

Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on corporate revenues in India in 1st quarter and 2nd quarter 2020, by sector

Problems faced by business due to COVID-19 in India 2020

Problems faced by business due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) in India in 2020

COVID-19 impact on start-up funding in India 2020

The impact of COVID-19 on Indian tech start-ups in different funding stages between April and October 2020

Retail and consumption

- Premium Statistic Reasons for not visiting restaurants after COVID-19 lockdown India 2020

- Basic Statistic Opinion on shopping for non-essentials after COVID-19 lockdown relaxation India 2020

- Basic Statistic COVID-19 impact on media consumption India 2020 by type of media

- Basic Statistic Opinion on online deliveries after COVID-19 lockdown relaxation India 2020

- Premium Statistic Opinion on impact of COVID-19 lockdown on grocery availability India 2020

- Basic Statistic People engaged in panic buying due to COVID-19 India 2020

Reasons for not visiting restaurants after COVID-19 lockdown India 2020

Reasons for not visiting favorite restaurant after the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown in India as of May 2020

Opinion on shopping for non-essentials after COVID-19 lockdown relaxation India 2020

Opinion about purchasing items beyond essentials after the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown relaxation in India as of May 2020

COVID-19 impact on media consumption India 2020 by type of media

Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) on media consumption in India as of March 2020, by type of media

Opinion on online deliveries after COVID-19 lockdown relaxation India 2020

Opinion about permitting e-commerce platforms to deliver all goods after the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown relaxation in India as of May 2020

Opinion on impact of COVID-19 lockdown on grocery availability India 2020

Opinion on impact of COVID-19 lockdown on grocery availability in India from March 20, 2020 to May 18, 2020

People engaged in panic buying due to COVID-19 India 2020

Share of people engaged in panic buying due to coronavirus (COVID-19) in India in 2020

Relief and financial aid

- Premium Statistic Value of government aid to combat COVID-19 in India April 2020

- Premium Statistic Impact of government aid to combat COVID-19 in India September 2020

- Premium Statistic Top ten states by number of people fed during COVID-19 lockdown in India 2020

- Basic Statistic Government shelter homes during COVID-19 in India 2020 by state

Value of government aid towards the coronavirus (COVID-19) across India as of May 6, 2020, by type (in billion Indian rupees)

Impact of government aid to combat COVID-19 in India September 2020

Number of people aided by the government relief package towards the coronavirus (COVID-19) across India as of September 9, 2020, by type (in millions)

Top ten states by number of people fed during COVID-19 lockdown in India 2020

Leading states by number of free meals provided by the state/NGO during the coronavirus (COVID-19) lockdown in India as of April 2020 (in millions)

Government shelter homes during COVID-19 in India 2020 by state

Number of government shelter homes during the coronavirus (COVID-19) in India as of April 2020, by state

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

- Readers’ Blog

Impact of Covid-19 on Indian economy

The Impact of Covid-19 on Indian Economy

As per the official data released by the ministry of statistics and program implementation, the Indian economy contracted by 7.3% in the April-June quarter of this fiscal year. This is the worst decline ever observed since the ministry had started compiling GDP stats quarterly in 1996. In 2020, an estimated 10 million migrant workers returned to their native places after the imposition of the lockdown. But what was surprising was the fact that neither the state government nor the central government had any data regarding the migrant workers who lost their jobs and their lives during the lockdown.

The government extended their help to migrant workers who returned to their native places during the second wave of the corona, apart from just setting up a digital-centralized database system. The second wave of Covid-19 has brutally exposed and worsened existing vulnerabilities in the Indian economy. India’s $2.9 trillion economy remains shuttered during the lockdown period, except for some essential services and activities. As shops, eateries, factories, transport services, business establishments were shuttered, the lockdown had a devastating impact on slowing down the economy. The informal sectors of the economy have been worst hit by the global epidemic. India’s GDP contraction during April-June could well be above 8% if the informal sectors are considered. Private consumption and investments are the two biggest engines of India’s economic growth. All the major sectors of the economy were badly hit except agriculture. The Indian economy was facing headwinds much before the arrival of the second wave. Coupled with the humanitarian crisis and silent treatment of the government, the covid-19 has exposed and worsened existing inequalities in the Indian economy. The contraction of the economy would continue in the next 4 quarters and a recession is inevitable. Everyone agrees that the Indian economy is heading for its full-year contraction. The surveys conducted by the Centre For Monitoring Indian Economy shows a steep rise in unemployment rates, in the range of 7.9% to 12% during the April-June quarter of 2021. The economy is having a knock-on effect with MSMEs shutting their businesses. Millions of jobs have been lost permanently and have dampened consumption. The government should be ready to spend billions of dollars to fight the health crisis and fast-track the economic recovery from the covid-19 instigated recession. The most effective way out of this emergency is that the government should inject billions of dollars into the economy.

The GDP growth had crashed 23.9% in response to the centre’s no notice lockdown. India’s GDP shrank 7.3% in 2020-21. This was the worst performance of the Indian economy in any year since independence. As of now, India’s GDP growth rate is likely to be below 10 per cent.

The Controller General of Accounts Data for the centre’s fiscal collection indicates a gross-tax revenue (GTR) of rupees 20 lakh crore and the net tax revenue of rupees 14 lakh crore for 2020-21. The tax revenue growth will be 12 per cent, which would mean the projected gross and the net tax revenues for 2020-21 would be rupees 22.7 lakh crore and 15.8 lakh crore respectively.

This suggests some additional net tax revenues to the centre amounting to rupees 0.35 lakh crores as compared to the budget magnitudes. The main expected shortfall may still be in the non-tax revenues and the non-debt capital receipts. If we look down in the past, the growth rate for the non-tax revenues and non-debt capital receipts have been volatile, but if we add them together, they average to a little lower than 15% during the five years preceding 2020-21.

How have different sectors been affected due to Covid-19?

Hospitality Sector:

As many states have imposed localised lockdowns, the hospitality sector is facing a repeat of 2020. The hospitality sector includes many businesses like restaurants, beds and breakfast, pubs, bars, nightclubs and more. The sector that has contributed to a large portion of India’s annual GDP has been hit hard by restrictions and curfews imposed by the states.

Tourism Sector:

The hospitality sector is linked to the tourism sector. The sector that employs millions of Indians started bouncing back after the first wave, but the second wave of covid was back for the devastation! The tourism sector contributes nearly 7% to India’s annual GDP.

It comprises hotels, homestays, motels and more. The restrictions due to the second wave have crippled the tourism sector, which was already struggling to recover from the initial loss suffered by the businesses in 2020.

Aviation and Travel sector:

Aviation and other sector establishments faced a massive struggle during the second wave of the pandemic. The larger travel sector is also taking a hit as people are scared to step out of their homes. For airlines and the broader travel sector, its recovery will depend on whether people in future will opt for such services. At present, the outlook for the aviation and broader travel sector does not look good.

Automobile sector:

The automobile sector is expected to remain under pressure in the near term due to the covid-19 situation in India.

Real Estate and Construction sector:

The real estate and construction activities have started facing a disruption during the second wave as a large number of migrant workers have left the urban areas. The situation has not been grave as of 2020 for this sector.

Fiscal Deficit:

The Covid-19 pandemic has not affected our fiscal deficit and disinvestment target much. In this year’s union budget, Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a fiscal deficit target of 6.8% for 2021 to 2022. India’s fiscal deficit for 2020-21 zoomed to 9.5% of GDP as against 3.5% projected earlier. Our finance minister has promised to achieve a fiscal deficit of 4.5% of GDP by 2025-26 by increasing the steaming tax revenues through increased tax compliance as well as asset monetization over the years. According to the medium-term fiscal policy statement that the government had presented in February 2020, the fiscal deficit for 2021-22 and 2022-23 was at 3.3% and 3.1% respectively.

The impact of the lockdowns and restrictions:

The extent to which localised lockdowns and restrictions have been imposed in the past have impacted the economic recovery timeliness. There is a scope for sustained fiscal stimulus going throughout the year. To some extent, if credit is made available to businesses at low-interest rates, then monetary stimulus is also possible. The second wave has pushed back India’s fragile economic recovery. Rising inequality and strained household balance sheets have constrained the recovery. From growing only 4% in 2019-20 to contracting 7-8% in 2020-21 to staring at another low economic growth recovery in 2021, India has been virtually stopped in all its tracks. Therefore, fiscal policy must lend a generous helping hand to lead vulnerable businesses and households towards economic recovery.

What is the path to recovery?

If the outbreak worsens over time, or if the case numbers are very high, this would elevate the risk to India’s economic and fiscal recovery. The Indian economy should resume its recovery once the covid waves recede and the Indian economy will continue to grow at a faster pace than its peers at similar levels of per capita income around the world. On the downside, there will be less vigorous recoveries in the government revenues and severe downside scenarios may entail additional fiscal spending. Commodities and the automobile sector are severely affected by the initial stream of infections and associated lockdown measures. It recovered strongly in the second half of 2021.

The recovery in the global economy has made it unlikely that a sharp price decline like 2020 will happen again. The pent up demand in the automobile sector will likely drive a strong recovery when curbs are relaxed as was seen in 2020. The second wave of covid-19 has challenged an otherwise strong recovery for Indian Infrastructure. As consumers strive to maximize their utility, they will maintain earning due to regulated returns, fixed tariffs and quick recovery in demand. Airports are most at risk with international traffic recovery likely delayed by another year. This may impede a strong domestic recovery if the government increases the severity and scope of restrictions on mobility. A strong recovery is needed after a crushing 2020. As the outbreak grew worse the state governments have applied restrictive lockdown measures that halted the budding economic recovery in tracks.

Downgrades are a warning not to take economic recovery for granted. The slow pace of vaccinations is likely to be a burden on India’s economic recovery. The Indian recovery has been vigorous across many sectors particularly in the last quarter of fiscal 2021. Halts to domestic air traffic and subdued international travel have dismantled recovery for airports. The covid wave has hit small and medium-size enterprises particularly hard. It has delayed recovery in banks’ asset quality. Mobility has been down to 50-60% of the normal levels. Therefore, people are staying home more and spending less. Recovery will take hold later this year. India’s budding economic recovery throughout March solidified government revenues.

Power Sector: The Indian power sector will generate huge revenues and it would track the recovery of the GDP of India.

Airports: The second wave has threatened India’s air recovery traffic. The domestic passenger traffic has decreased by 75% of the pre-covid levels. The traffic recovery in the worst-case scenario could be 10% lower than what is predicted. Weaker traffic hits the cash flows of the airports. There will be a sharp recovery in road traffic after a short disruption. The commercial vehicle traffic will see better resilience as it supports logistics and essential services.

Ports: A modest recovery will be witnessed by import volumes. Fertilizers and containers will increase at a greater pace than crude and coal segments.

Operating cash flows will recover most infrastructure and utilities such as water, sewage, dams and natural gas segments. Credit loss will remain high in the fiscal year 2022 at 2.2% of the total loans before it recovers to 1.8% in 2023. India’s strong economic recovery and the steps taken by the central governments and the state government to mitigate the effects of the economic crisis have lessened the burden on the banks. Additionally, banks have raised capitals to strengthen their balance sheets. This will smoothen the hit from covid related losses. The weak consumption accompanied by large scale job losses and the salary cuts in the formal sector may hit the banking sector’s loans and ‘credit card’ loans. This is accompanied by lower recovery rates in the bank’s non-performing assets. That could lead to a rise in weaker loans.

If we have to move towards sustained and real economic growth against v-shaped, k-shaped or w-shaped paths, the states and the centre need to work towards a cooperative strategy through their “cooperative federalism” scheme to increase the vaccination drive.

Last year, the government chose life over livelihoods. By choosing to protect the former, the covid 1.0 was delayed in September and its intensity was much lower than predicted. By January 2021, the government had declared victory over covid-19. The first threat to economic recovery is the regional cases which are resulting in further extension of lockdowns and hence they are limiting the pace of economic recovery. The second threat is the vaccination rates arising from the vaccine supply. Without inoculating a major portion of our labour force, there is a threat that viruses will disrupt our real economy. It is apparent from the worldwide cases of Covid-19.

best article for those who are thinking of starting for new business. thanks for your information i will have a plan for contract business for constru...

many people\'s income also increased during covid , only the poor section of the country has been economically affected badly. could somebody write ...

All Comments ( ) +

@ Shreyansh Mangla

I have a communication and journalism background. I am currently pursuing a Master's Degree in Journalism from Delhi School of Journalism, University of Delhi.

- The book publishing Industry in India: Flourishing or fading

- The movement for Right to Information in India

- Billionaires aiming for space

- Social media in journalism

Oldest language of the world

whatsup University

Today’s time is paramount!

The role of technology in the future and its impact on society.

Toshan Watts

Recently Joined Bloggers

The impact of COVID-19 and the policy response in India

Subscribe to global connection, maurice kugler and maurice kugler professor of public policy, schar school of policy and government - george mason university shakti sinha shakti sinha senior fellow - world resources international (wri india).

July 13, 2020

Much has been written about how COVID-19 is affecting people in rich countries but less has been reported on what is happening in poor countries. Paradoxically, the first images of COVID-19 that India associates with are not ventilators or medical professionals in ICUs but of migrant laborers trudging back to their villages hundreds of miles away, lugging their belongings. With most of the economy shut down, the fragility of India’s labor market was patent. It is estimated that in the first wave, almost 10 million people returned to their villages, half a million of them walking or bicycling. After the economic stoppage, the International Labor Organization has projected that 400 million people in India risk falling into poverty .

Agriculture is the largest employer, at 42 percent of the workforce, but produces just 18 percent of GDP. Over 86 percent of all agricultural holdings have inefficient scale (below 2 hectares). Suppressed incomes due to low agricultural productivity prompt rural-urban migration. Migration is circular, as workers return for some seasons, such as harvesting.

Evidence of Indian labor market segmentation is widely available—with a small percentage of workers being employed formally, while the lion’s share of households relies on income from self-employment or precarious jobs without recourse to rights stipulated by labor regulations. Only about 10 percent of the workforce is formal with safe working conditions and social security. Perversely, modern-sector employment is becoming “informalized,” through outsourcing or hiring without direct contracts. The share of formal employment in the modern sector fell from 52 percent in 2005 to 45 percent in 2012. During this period, formal employment went up from 33.41 million to 38.56 million (about 15 percent), while nonagricultural informal employment increased from 160.83 million to 204.03 million (about 25 percent) .

Most informal workers labor for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) that emerged as intermediate inputs and services suppliers to the modern sector. However, workers struggle to get paid, which the government identifies as great challenge. Payroll and other taxes, as well as limited access to subsidized credit for large firms, are disincentives to MSME growth. Although over half of India has smartphone access, relatively few can telework. Retail and manufacturing jobs require physical presence involving direct client interaction. Indeed, income for families unable to telework has fallen faster.

Related Books

Geoffrey Kemp

May 3, 2010

June 14, 2012

Sebastian Edwards, Nora Claudia Lustig

September 1, 1997

The government’s crisis response has mitigated damage, with a fiscal stimulus of 20 trillion rupees , almost 10 percent of GDP. Also, the Reserve Bank of India enacted decisive expansionary monetary policy . Yet, banks accessed only 520 billion rupees out of the emergency guaranteed credit window of 3 trillion rupees. In fact, corporate credit in June is lower than June last year by a wide margin after bank lending’s fall. S&P has estimated the nonperforming loans would increase by 14 percent this fiscal year . Corporations have deleveraged retiring old debts and hoarding cash, as have households. Recovery through investment and consumption has stalled . These trends are exacerbated due to the pandemic. The manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) recovered 50 percent since May but at 47.2 it remains in negative territory. Services contribute over half of GDP but its PMI, even after bouncing back , remains low at 33.7 in June. Consumption of electricity, petrol, and diesel have regained from the lockdown lows but are still 10-18 percent below June 2019 levels . Agriculture has been the bright spot, with 50 percent higher monsoon crop sowing and fertilizer consumption up 100 percent. Unemployment levels had spiked to 23.5 percent but with a mid-June recovery to 8.5 percent—and then crept up again marginally.

The National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGA) and supply of subsidized food grains have acted as useful buffers keeping unemployment down and ensuring social stability. Thirty-six million people sought work in May 2020 (25 million in May 2019). This went up to 40 million in June 2020 (average of 23.6 million during 2013-2019 period). The government has ramped up allocation to the highest level ever, totaling 1 trillion rupees. Similarly, in addition to a heavily subsidized supply of rice and wheat, a special scheme of free supply of 5 kilograms of wheat/rice per person for three months was started and since extended by another three months, covering 800 million people. There have also been cash transfers of 500 billion rupees to women and farmers .

However, MNREGA has an upper bound of 100 days guaranteed employment and it also does not cover urban areas. Agriculture cannot absorb more labor, with massive underlying disguised unemployment. A post-pandemic survey shows that the MSME sector expects earnings to fall up to 50 percent this year. Critically, the larger firms are perceived healthier. However, small and micro enterprises, who have minimal access to formal credit, constitute 99.2 percent of all MSMEs . These are the largest source of employment outside agriculture. Their inability to bounce back could see India face further economic and also social tensions. The economy is withstanding both supply and demand shocks, with the wholesale prices index declining sharply .

We identified labor market pressures toward increased poverty, both in the extensive margin (headcount) and intensive margin (deprivation depth). India needs to ramp up MNREGA, introduce a guaranteed urban employment scheme, and boost further cash transfers to poor households. Government efforts have been enormous in macroeconomic policy (fiscal stimulus and monetary loosening) to mitigate adversity but fiscal space is narrowing, requiring the World Bank and other international financial institutions to step up and help avert even greater hardship. Also, ongoing advances towards structural economic policy reforms have to continue.

Related Content

Ipchita Bharali, Preeti Kumar, Sakthivel Selvaraj

July 2, 2020

Urvashi Sahni

May 14, 2020

Stuti Khemani

April 30, 2020

Global Economy and Development

India South Asia

Vera Songwe, Landry Signé

September 18, 2024

Mireya Solís

September 16, 2024

John W. McArthur, Fred Dews

September 13, 2024

Advertisement

The Impact of COVID-19 on the Household Economy of India

- Published: 17 November 2021

- Volume 64 , pages 867–882, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Bino Paul ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5644-0484 1 ,

- Unmesh Patnaik 1 ,

- Kamal Kumar Murari 1 ,

- Santosh Kumar Sahu 2 &

- T. Muralidharan 3

7647 Accesses

7 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

COVID-19 has disrupted the Indian economy. Government-enforced lockdown to restrict the spread of infection has impacted the household economy in particular. We combine aggregates from national income accounts and estimates from the microdata of a labour force survey covering more than 0.1 million households and 0.4 million individuals. The aggregate daily loss to households is USD 2.42 billion. While loss to earnings accounts for 72% of the total, the rest 28% is wage loss. Service-based activities account for two thirds of wage loss, and natural resource-based activities are responsible for most of the earning loss. The dominance of informal job contracts and job switching in labour markets intensifies this, with the most vulnerable group consisting of 57.8 million in casual engagement, who have a high degree of transition from one stream of employment to another on a daily basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Did the UK policy response to Covid-19 protect household incomes?

Macroeconomic Effects of COVID-19 Across the World Income Distribution

Bird’s Eye View of COVID-19, Mobility, and Labor Market Outcomes Across the US

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak and ensuing lockdowns resulted in multiple economic challenges for transitional economies like India. Policy responses to mitigate the impact of shutdown are dependent upon the assessment of losses. The relief packages announced for India range between 0.1 and 11% of the national income (IMF 2020 ). Most of these government backed packages are found on crude calculations of impacts at the aggregate level while ignoring the bearings on livelihood of the households. The households play a pivotal role in the circular flow of goods and services in the economy, especially in the Indian context, where the informal sector is a major contributor to the economy (Sengupta et al. 2008 ; National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector 2008 ). The Indian labour market vastly differs from geographies like USA, Europe and China since regular wage employment accounts for a mere one-fourth of total employment, while for the above set of geographies regular wage employment forms the core (International Labour Organization 2020 ). In the absence of jobs that are aligned with any form of employment relation, as in India, streams of employment tend to be embedded with the household economy that has principal stakes in production, consumption and distribution (Baker et al. 2020 ). Therefore, the impact of lockdown due to pandemics for India will be very different from the above geographies. However, our results may be representative of other countries in South Asia. No study has explored these multifarious attributes that proliferate the vulnerability of households (Morduch 1994 ). The issue of vulnerability pertinent to households is captured through three constructs: (1) wage loss, (2) earning loss and (3) extremely vulnerable workforce (high chances of shifting employment within a small window of 7 days).

We develop a systematic method to account the impacts of such risks on consumption, production and distribution from the standpoint of households in India based on microdata (Deaton 1997 ). We have done two novel things: (1) we control for formal employment relations and (2) we account for earning loss. Quite importantly, wage is an outcome of formal or informal employment relations, while earning emanates from self-employment. Further, we disaggregate losses with respect to principal and subsidiary engagements. Further, we compute the probability of transition in the stream of employment during a small window of 7 days, capturing the magnitude of what we term as ‘extreme vulnerability’.

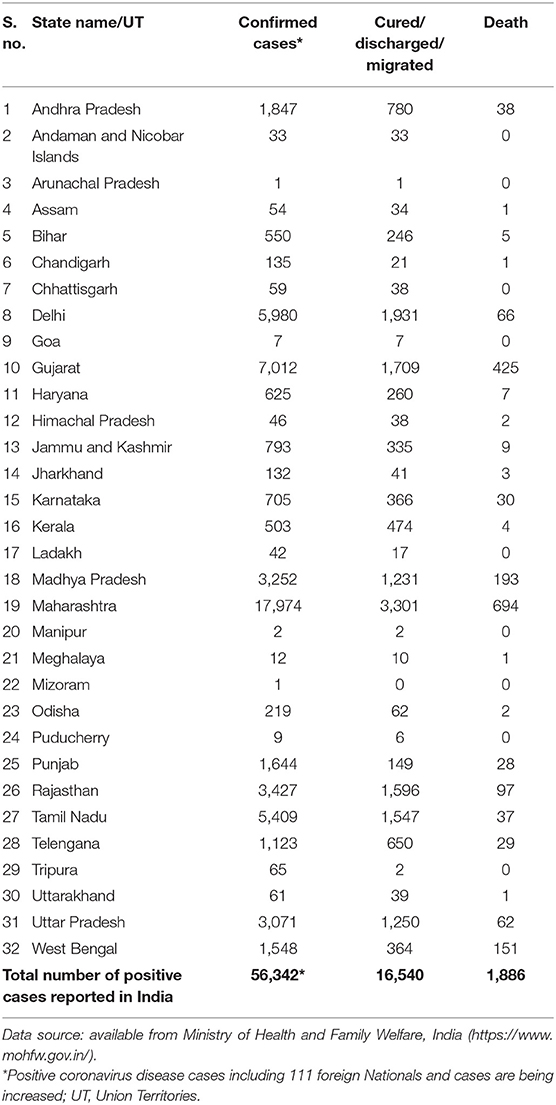

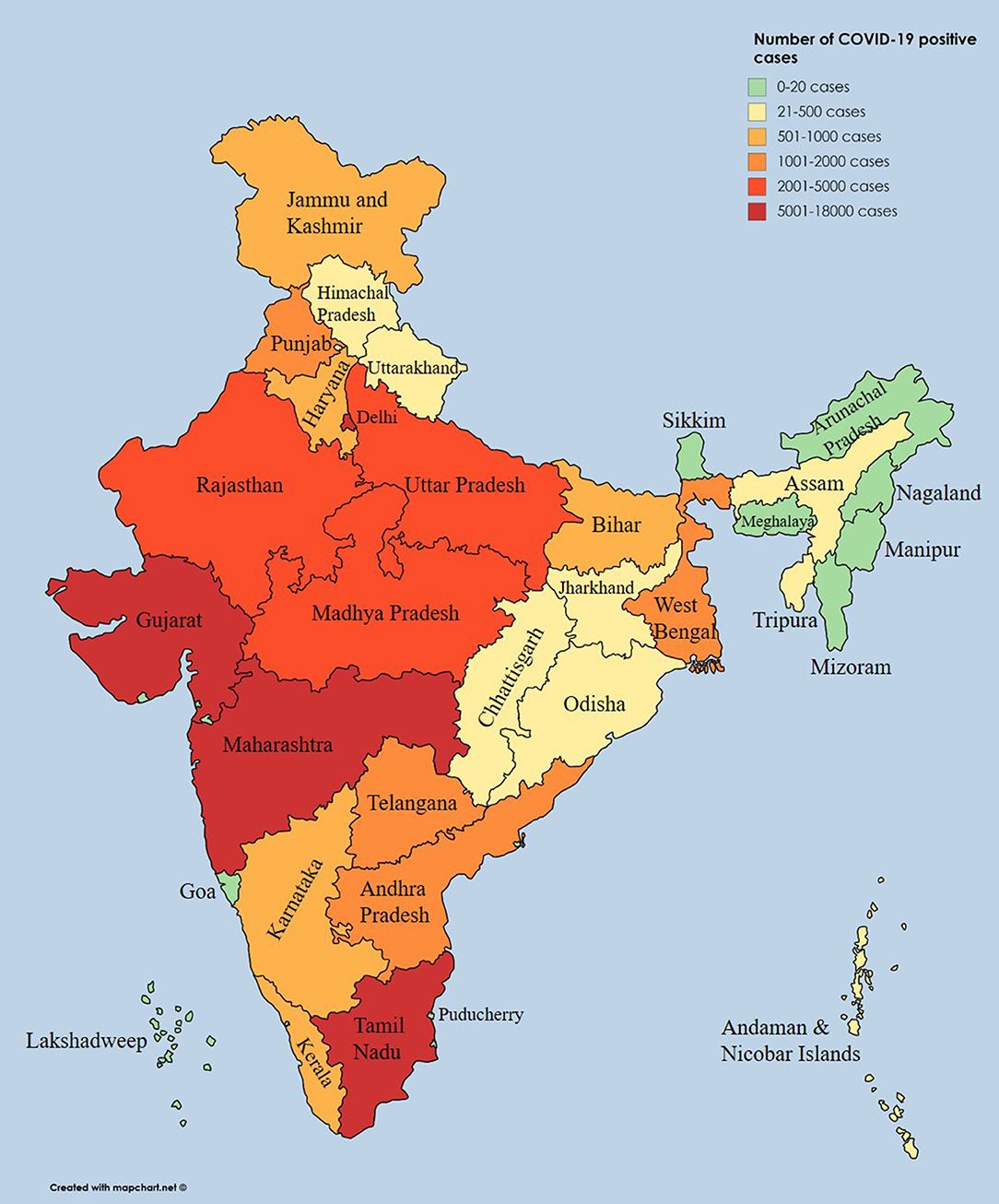

The first confirmed COVID-19 case in India was reported on 30 January 2020. Till the last week of March, the spread of COVID-19 cases in India was slow (Fig. 1 a). Anticipating an intensive spread, the Government of India declared the first lockdown on 25 March that continued till 14 April with strict social distancing norms and regulation on outdoor movement. Although the spread of COVID-19 was very slow during this period, the suspension of economic activities has devastated labourers. Our thesis is on the pivotal role of households in the Indian economic system. The household, as an institution compared to other two major institutions—government and corporate sector—constitutes a principal share in employment, production and consumption and therefore very important in the circular flow of economic resources (Table S1 in the Appendix). While this is conveyed by macroeconomic identities, the manuscript uses a large sample survey data to pinpoint the significance of households in the economy.

COVID-19 progression in India. a The percentage values in the parenthesis (brown font) show the growth rate of confirmed cases, recovered cases and deaths, respectively. The values in the parenthesis corresponding to the loss show lower and upper bounds of the estimation. b The location of green, orange and red zones. The white fill is the administrative boundary and shows non-availability of data in b . c The number of marginal workers, total households and total workforce in the green, orange and red zones based on Census 2011 (International Labour Organization 2020)

2 Data and Methods

2.1.1 covid-19 cases.

Data on COVID-19 progression (as shown in Fig. 1 a) were taken from the Centre for System Science and Engineering at John Hopkins University, tracking daily records of confirmed, deaths and recovered cases due to COVID-19 from 22 January 2020 to till date. We used India specific data for the period from 22 January 2020 to 31 May 2020. The data set was downloaded on 11 June 2020. Footnote 1

2.1.2 Census 2011

District-scale total number of households, marginal workforce and total workforce (as shown in Fig. 1 c) were extracted from Census 2011. Footnote 2 These data are merged with the district-wise zoning information obtained from Government of India notification (National Accounts Statistics 2019a , b ; Census of India 2012 ; PIB 2020a , b , c , d ).

2.1.3 Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) Data

For loss assessments, we use the recent microdata on labour from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS Footnote 3 ), to disaggregate wage with respect to economic activities that include diverse set of activities spread across primary, secondary and tertiary industries (PLFS 2019 ; PLFS Microdata 2019 ). The total number of household records accessed is 102,113, and the records for members are 433,339.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 counting and accounting the labour in an economy.

Fundamentally, labour is a major segment of the population that generates both wage and earning for a household. The total population ( P ) of a country can be divided into two parts: (1) persons who are being engaged in the labour market ( L b ) and (2) those who do not participate in the labour market ( N ). Primarily, participation in the labour market is subject to the person’s age being higher than the minimum age limit prescribed by the law. For instance, in India, engaging persons who are 14 years. Below this age, paid work is illegal and such engagements are identified as child labour. Footnote 4

2.2.2 Employment and Unemployment Status

Those who are in the labour force are either engaged in the paid work (the category of employed E ), or waiting (searching or not searching) for opportunities to engage in paid work (the category of unemployed U ). While L and N constitute P , the labour market is defined by E and U . . This structure may be expressed as follows:

2.2.3 Types of Employment

The category labelled as employed ( E ) comprises three groups: (1) self-employed (SE), (2) regular wage-salaried employees ( R ) and (3) casual work ( C ). SE consists of own account worker, employer and working as a helper in household enterprises. R includes a whole range of employment for which workers are paid at regular intervals (for example monthly) for a continuous engagement in the paid work. On the other hand, workers who belong to category C are engaged in paid activities that lack continuity. Formally,

While engagement in SE generates earning for a person that is a mix of wage, profit, interest, and rent, other two categories (i.e. R and C ) provide wage to the persons engaged.

2.2.4 Status of Employment: Principal and Subsidiary

Drawing cues from National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), employment in terms of principal and subsidiary engagement, is classified into three: (1) workforce being engaged in principal activity, however not pursuing any subsidiary activity, (2) engaged in both principal and subsidiary activities and (3) engaged only in subsidiary activity. To consider any activity as subsidiary, the engagement should not be less than 30 days during a year. By using subsidiary engagement, measurement of employment becomes broader compared to counting only principal engagement as employment. Table S4 (Appendix) provides a schema of principal and subsidiary employment.

2.3 Computing the Losses to Household Engagements due to Lockdown

2.3.1 wage and earnings.

We classify direct losses incurred by households due to economic lockdown into wage loss ( L w ) and earnings loss ( L y ). These two losses sum to loss ( L ) to the household if the economy falls into an economic lockdown. The national income accounts provide the aggregate of wage in the economy ( W t ) for a particular year, known as compensation to employees. However, W t only captures the workforce who are in the ambit of formal and informal employment relationships. The aggregate Y ht is the measure of earning and operating surplus (earnings from rent and profit) of the households in the economy, principally capturing self-employed persons.

2.3.2 Wage and Earnings across Different Sectors of an Economy

We begin with the wage of household members who were engaged in formal or important employment relations ( w i ). Aggregating the cross-sectional data of w i produces the combined total for a particular industry for a given year ( \(\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {w_{ist} }\) ). In a similar vein, we compute the sum of \(\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {w_{ist} }\) all economic activities, generating a double sum of wages for ‘ i ’ individuals and ‘ s ’ economic activities during the year ‘ t ’ ( \(\sum\nolimits_{s = 1}^{k} {\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {w_{ist} } }\) ). To find the share of a particular economic activity in the wage being earned by households, we divide economic activity-specific sum of wage by the sum of industry aggregates to \(\left( {\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{s = 1}^{k} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}} \right)\) . Multiplying \(\left( {\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{s = 1}^{k} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}} \right)\) by W t , we get the annual losses if the economy is in full lockdown.

Nevertheless, exercise of this sort seems to be far off from reality. Even during the full lockdown, some people may get wages, depending on the nature of employment contracts. For instance, in the case of formal employment contracts, subject to the mandate of labour law and social security rules and caveats, payment of wage and social security benefits is unlikely to be interrupted. Therefore, it makes sense to control the effect of formal employment relations, which we perform next by aggregating the wage earned through formal employment contract ( \(\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w f_{ist}\) ) and computing its share in total wage across all economic activities \(\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {w_{ist} }\) . Hence, \(\left[ {1 - \left( {\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} wf_{ist} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}} \right)} \right]\) provides the proportion of wage received through informal means of employment. This measure, to a greater extent, gauges the aggregate of wage, controlling for the impact of wage protection during a complete lockdown in the economy.

To calculate the loss of wage ( L w ) to households in the economy on any lockdown day, we multiply the ratio of economic activity-specific sum of wage to sum of activity aggregates \(\left( {\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{s = 1}^{k} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}} \right)\) by the control for wage earned through formal employment \(1 - \left( {\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} wf_{ist} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}} \right)\) . Finally, we multiply the product of these ratios by W t and divide the measure by the number of days in a year, i.e. 365. To put above arguments formally, \(L_{{\text{w}}}\) = \(\left[ {\left( {\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{s = 1}^{k} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}} \right){ }\left( {1 - \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} wf_{ist} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} w_{ist} }}} \right){ }\left( \frac{1}{365} \right)} \right]\) \(\times W_{t}\) . To compute L y , i.e. the loss for earnings, we follow similar procedures except that we control for the formal wage since earning is the outcome of self-engagements like own account work, employer or being an associate or helper in self-employment.

To put things in an analytical framework, we examine the aggregate from the national income accounts, measuring the earnings accruing to households by pursuing production and service activities, either for profit or not for profit. This aggregate ( \(Y_{ht} )\) captures the operating surplus or earning to the households in the economy. Similar to the previous computation of wage loss, we rely on the microdata of PLFS to find first the sum of earning \(\left( {\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {y_{ist} } } \right)\) in a particular economic activity, delimiting the domain to self-employed persons. Secondly, we calculate the aggregate of sums across economic activities \(\left( {\sum\nolimits_{s = 1}^{k} {\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {y_{ist} } } } \right)\) and divide the first measure (sum of earnings) by the second measure, to get the ratio \(\left( {\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} y_{ist} }}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{s = 1}^{k} \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} y_{ist} }}} \right)\) . To arrive at an estimate of daily loss, we multiply the above ratio with Y ht and then divide the whole expression by 365 days. Formally, the procedures are stated as follows:

2.4 Aggregating Employment with Losses in Wages and Earnings Across Different Sectors and Groups

Now, we combine the schema of employment status presented in Table 1 , with the decomposition \(L_{{\text{w}}}\) and \(L_{{\text{y}}}\) with respect to households engaged in primary employment status, subsidiary employment status and not in the labour force ( E P , S ), ( E P , ~ S ), ( U P , S ) and ( N P , S ). Further to decompose the loss, we compute shares of wage \(\left( {\frac{{W\left( {E_{P} ,S} \right)}}{{W\left( {E_{P} , S} \right) + W\left( {E_{P} ,\sim S} \right) + W\left( {U_{P} ,S} \right) + W\left( {N_{P} ,S} \right) }}} \right)\) and earning \(\left( {\frac{{Y\left( {E_{P} ,S} \right)}}{{Y\left( {E_{P} , S} \right) + Y\left( {E_{P} ,\sim S} \right) + Y\left( {U_{P} ,S} \right) + Y\left( {N_{P} ,S} \right) }}} \right)\) with respect to each of these categories. Next, we multiply shares of wage and earning by \(L_{{\text{w}}}\) and \(L_{{\text{y}}}\) , respectively.

Further, using similar computation procedures, we disaggregate losses in wage and earning from men ( \(L_{{\text{w MEN}}}\) , \(L_{{\text{y MEN}}}\) ) and women ( \(L_{{\text{w WOMEN}}} , L_{{\text{y WOMEN}}}\) ). Computation is stated as follows:

2.5 Computing Chances of Daily Transition

We compute chances of an employed person switching from any stream of employment to the another across any pair of days over a week. For example, what are the chances of a person who was self-employed on day 1 to shift to casual employment on day 2, while joining back to self-employment the rest of the week. To measure the change of this sort, we compare the status of employment between any pair of days. The number of pairs of days out of a week is \(C_{2}^{7}\) .

First, we compute the share of employed who remained in the same stream of employment ( \({\text{Stable}}_{k}\) ) on any particular pair of days, out of the count of employment during any pair of days during a week \(\left( {\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {E_{idk} } } \right)\) , and summing it across all pairs of days \(\left[ {\mathop \sum \limits_{d = 1}^{21} \left( {{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {\text{Stable}}_{idk} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {\text{Stable}}_{idk} } {\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} E_{idk} }}}\right.\kern-\nulldelimiterspace} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${\mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} E_{idk} }$}}} \right)} \right]\) . To compute the average proportion of \({\text{Stable}}_{k}\) , we divide the computed sum by \(C_{2}^{7}\) . Deducting this measure from absolute 1 yields the chances of shifting employment from the status k to l denoted by ( \(p_{k \to l}\) ) that varies from 0 to 1. Supposing \(p_{k \to l}\) = \(\frac{1}{4}\) , the chance of changing from employment k to l is 1 out of 4, implying that the chance of remaining in the same employment stream is \(\frac{3}{4}\) . Presumably, switching over from one employment to another one every day within a short duration of 7 days is a coping strategy to survive in a transient labour market. Therefore, we use \(p_{k \to l}\) to compute the size of extremely vulnerable employment ( \(EV_{k}\) ). To arrive at \(EV_{k}\) , we multiply \(p_{k \to l}\) , share of a particular employment stream in total employment ( \(\alpha_{k} )\) , and total employment \((E_{PS}\) ). Formally, it is stated in the following equation and Table 2 describes the notations used.

2.6 Scenarios for Loss Calculation during Lockdown Periods

The scenarios for calculating the losses to wage and earning across the lockdown periods are derived from the information provided in the Press Information Bureau of Government of India. They are created according to the level of relaxation allowed in each broad sector of the economy across the four lockdown periods. In essence, a full lockdown of the sector implies that the sector works at 0%, while a complete relaxation ensures that the sector works with 100% of its capacity. For instance, the services pertaining to the delivery and provisioning of essential commodities were operational across all the four lockdown phases and hence we assume that the sector worked with full capacity (100%). The lower and the upper bounds of the losses correspond to the lowest and highest working capacity under each scenario permissible for that sector, respectively. Table S5 (Appendix) describes the extent to which economic activities were functional.

The household’s income has two components: wage and earning. While a household earns from sources such as rents from property and interest or dividend from investments, the share of wage and earning combined together is too big to compare with other sources of income (National Accounts Statistics 2019a , b ). Besides, wages and earnings are outcomes of economic activities that are discernibly vulnerable to shocks like economic lockdowns or to any other exogenous risks. We find that suspension of economic activities results in a daily loss of about 2.42 billion USD for Indian households, of which approximately 0.679 billion USD (28%) is due to wage loss and the rest 1.741 billion USD (72%) is loss in earning, discounting for wage protection present across some occupations. Our estimate does not account for the losses to the industry and government sectors, which would escalate the figures of economic loss considerably upwards.

The total estimated loss to households during the series of lockdowns (25 March 2020–31 May 2020) is about 74.6 billion USD, which is close to the order of 2.75% of the total gross domestic product of India. Some sectors were allowed to operate with varying capacities to facilitate the flow of essential goods and services. We create scenarios for the level of functioning across different sectors based on the government’s notifications, which, in essence, varies from complete closure (0%) to full relaxation (100%) (PIB 2020a ). The lower and upper bounds of our estimates are 59 and 93 billion USD, respectively. Most of this is due to loss of earnings to households except in a few sectors like mining and information technology (IT) services (Fig. 2 ). The Government of India announced a second lockdown from 15 April to 3 May. Over this period, the restrictions to economic activities were slightly relaxed as the country was divided into three zones, green, orange and red, to facilitate differential economic relaxation (Fig. 1 b) (PIB 2020b ). Green zones were the districts reporting no new infections, orange zones were the ones with limited cases of infections, and red zones were regions of COVID-19 infection hot spots (PIB 2020b ). Most of the economic activities were under suspension in red and orange zones, while little relaxation was allowed in green zones. However, red and orange zones accounted for more than 80% of households and total workforce of the country (Fig. 1 c). Interestingly, red and orange zones were also the regions with intensive economic progress and also districts with maximum population of marginal workers (Fig. 1 c).

Sector-wise distribution of losses due to lockdown. a , c , d , e , f The horizontal red line in bars indicates the division of wage and earning loss of a sector. The error bar indicates lower and upper ranges of the estimated loss for a sector. b Wage loss (as the percentage of total loss) of individual industries and their classification as primary, secondary and tertiary sectors

Impacts during the second lockdown were roughly of the same order as in the first lockdown, particularly for the marginal workforce hoping for normalcy after enduring the hardship of the first lockdown. The estimated loss for the second lockdown was about 18.79 billion USD (14.96–22.75) (Fig. 2 ). The third and the fourth lockdowns were comparatively relaxed in the green zone, but in the red and orange zones the degree of restrictions was the same as before (PIB 2020c , d ). The estimated loss for the third lockdown and the fourth lockdown is about 12.1 billion USD (9.22–14.96) and 11.77 billion USD (8.72–14.83), respectively. Apart from the loss suffered by households, permanent loss of jobs and job opportunities is the bigger concern that will have longer-term impacts and will aggravate the household vulnerability, in particular to exogenous risks like the incidence of natural disasters that are likely to worsen in the context of changing climate (Krishnan et al. 2020 ).