Education Policy in Japan: Building Bridges towards 2030

Education in japan: strengths and challenges.

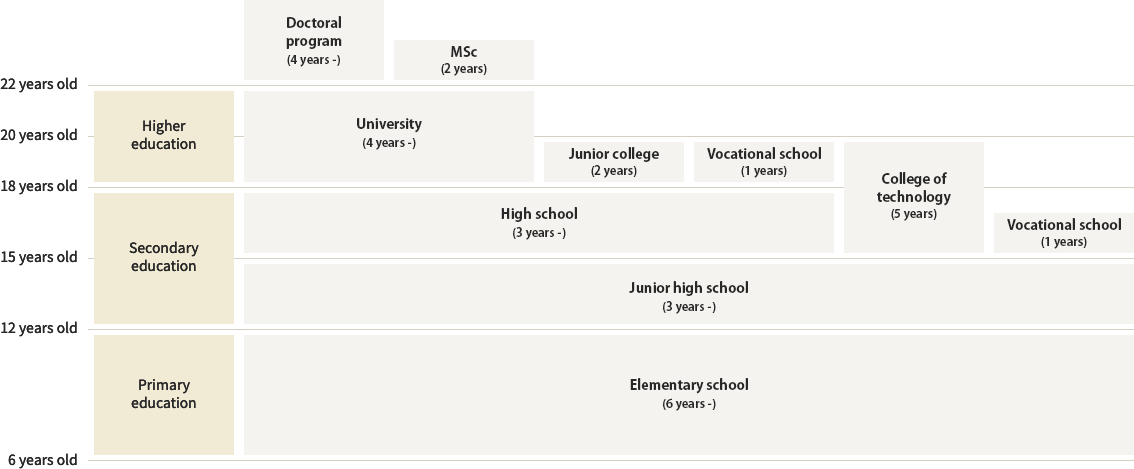

Japanese Educational System: Schooling to Higher Education

Jamila Brown Updated on July 16, 2024 Education in Japan

Many of you reading this article would likely have finished university. However, it’s essential to understand the Japanese educational system, especially if you are in Japan or planning to move in with school-going kids or a foreigner looking for higher education in Japan.

In this article

School Education System in Japan

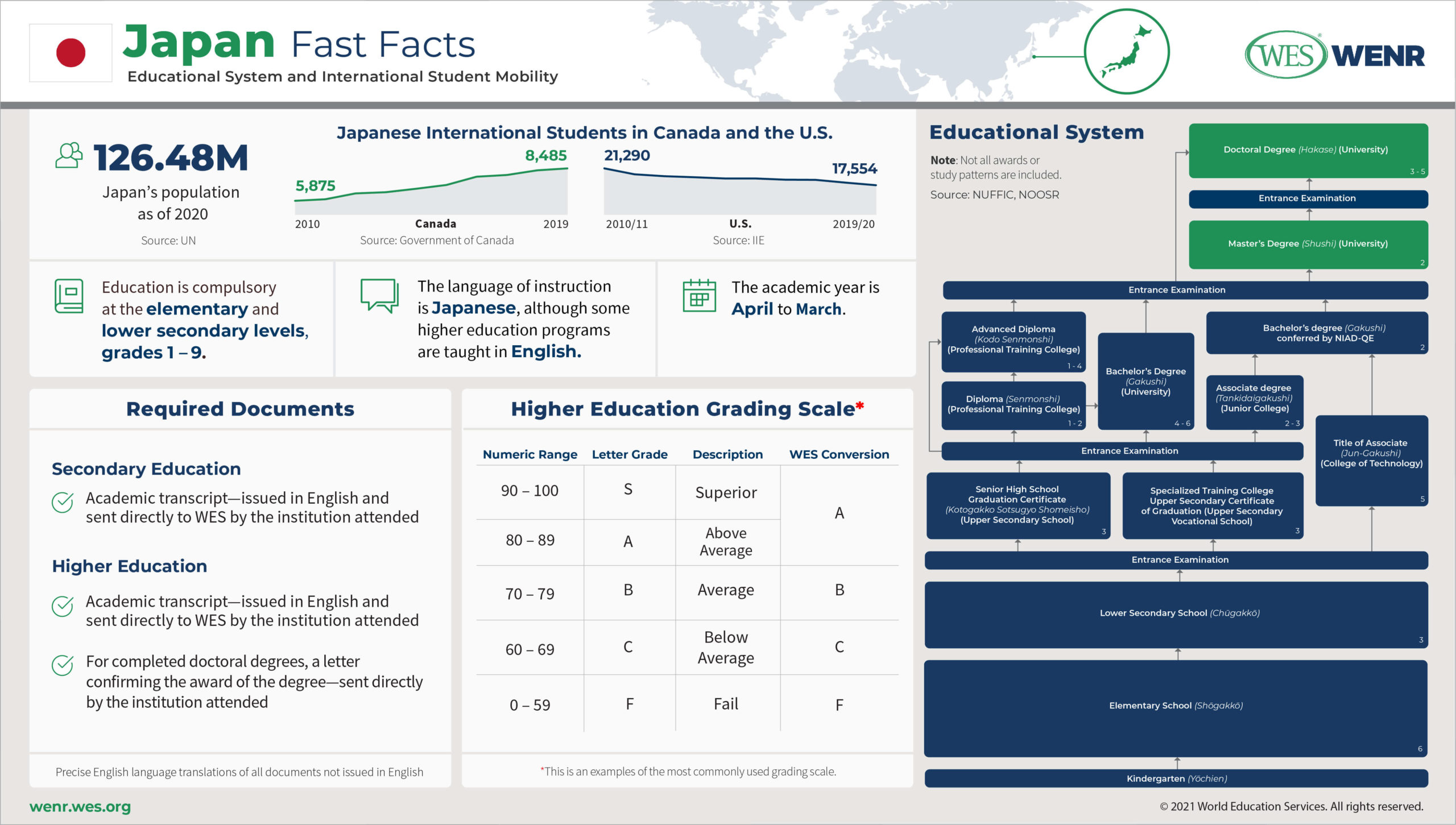

The Japanese school education system consists of 12 years, of which the first 9 years, from elementary school (6 years) to junior high school (3 years), are compulsory. After compulsory education, the next 3 years are for high school.

In Japan, compulsory education starts at age six and ends at age fifteen at the end of junior high school.

Japan performs quite well in its educational standards, and overall, school education in Japan is divided into five sections. These are as follows:

- Nursery school ( hoikuen or 保育園) – Optional

- Kindergarten ( youchien or 幼稚園) – Optional

- Elementary school ( sh ō gakk ō or 小学校) – Mandatory

- Junior high school ( Chūgakkō or 中学校) – Mandatory

- High School (高校 or Kōkō) – Optional

Once students graduate from high school in Japan, they can opt for university (daigaku or 大学) or vocational school (senmongakk ō or 専門学校) for higher education.

Cram Schools in Japan

Many Japanese students also attend cram school (“juku” or 塾) to catch up on the academic competition.

These are specialized schools that help students improve their grades or pass entrance examinations. These extended programs start after school, around 4 p.m., and, depending on the program, can end well into the evening.

Classes are held from Monday to Friday, with the occasional extra classes in schools on Saturdays. The school year starts in April and ends the following year in March.

Many Japanese schools have a three-semester system. These are as follows:

- First semester: From April to August

- Second semester: From September to December

- Third semester: From January to March

National and public primary and lower secondary Japanese schools do not charge tuition, making it essentially free for all students in Japan. Foreign children aren’t required to enroll in school in Japan, but they can also attend elementary and junior high school for free. Please check this guide for foreign students’ schooling in Japan.

However, if you wish to send your kids to international schools, you will need to pay a good amount of fees.

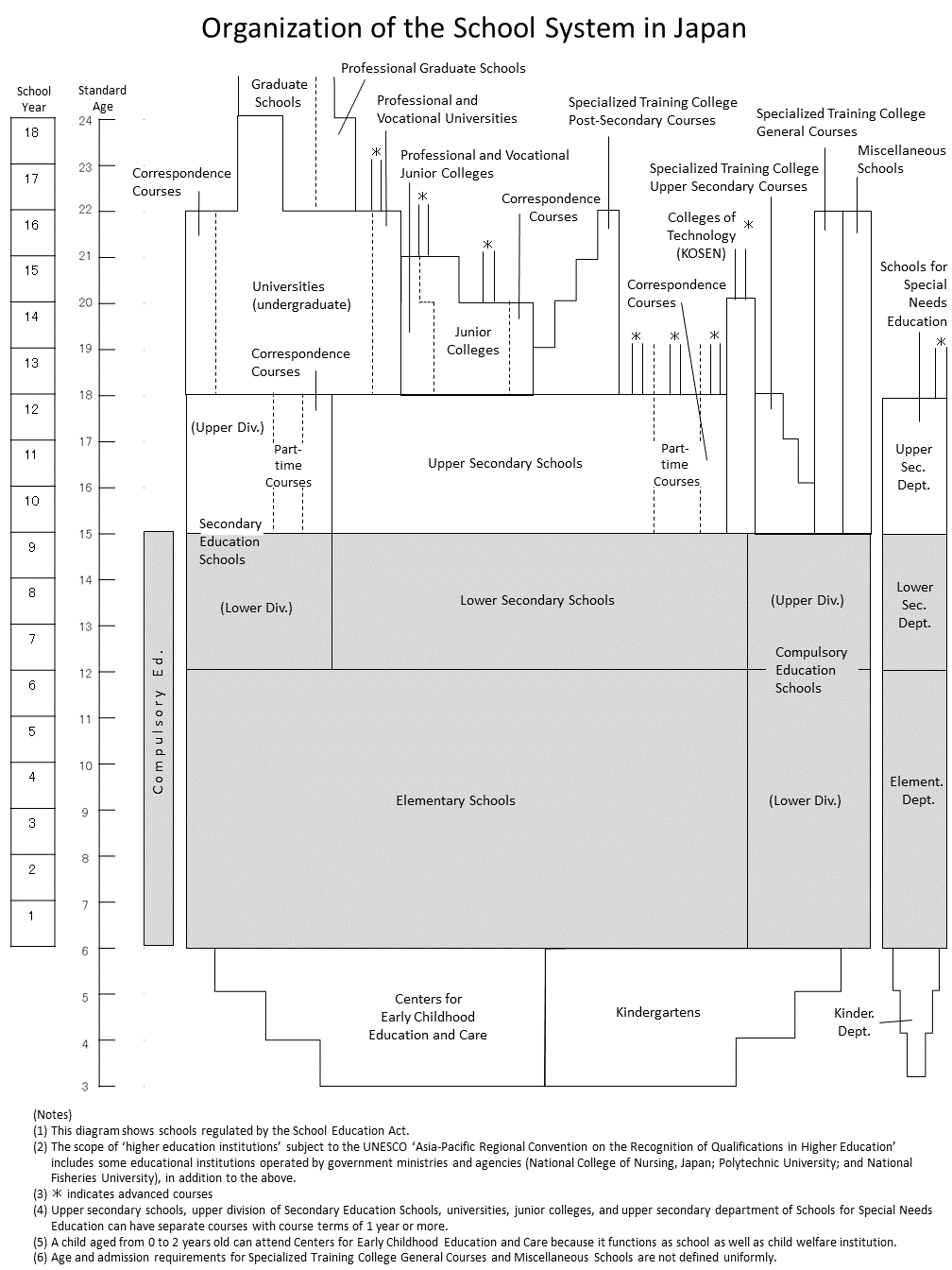

(Image credit: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Japan

Types of Japanese School

The typical age groups of students for elementary, junior high school, and high school in Japan are as follows:

- Elementary school for six years: (6 years old – 12 years old)

- Junior high school for three years (12 – 15 years old)

- High school for three years (15 – 18 years old)

Although high school isn’t compulsory, 99% of students nationwide pursue upper secondary education after graduating from junior high school.

There are public and private schools all across Japan. Public elementary and lower secondary schools are free, while private schools require much higher tuition fees.

All public schools are funded equally. Moreover, they have the same curriculum, and all schools have the same educational expectations nationwide. After World War II, education became more democratized to make education more accessible to low-income families.

International Schools in Japan

International schools have become more popular across Japan due to the rise of foreign residents in Japan.

While Japanese schools primarily instruct in Japanese, international schools have instructions in English. These schools are largely for children of expats and bicultural children; however, Japanese residents can also attend if they choose to. However, International schools are much more expensive than Japanese public schools.

There are many international schools across Japan, but not every school is accredited by the Ministry of Education. Some schools lack proper accreditations for Western standards as well. Therefore, if you’re interested in enrolling your children in an international school, you should do your research to make sure your children can pursue further education upon graduation.

Educational Facilities for Mentally Challenged

Physically and mentally challenged students can receive “special needs education.” This is called ‘tokubetsushienkyouiku’ (特別支援教育) and supports students in being self-reliant and enhancing their communication skills.

According to the National Institute of Special Education (NISE) 2022 report, 3.26% of the total number of students in Japan received special education in various forms. Children with more acute problems can attend specialized schools.

Most of these institutions are overseen by the local government and cater to children from kindergarten to senior high school.

Japanese School Curriculum

Students in Japan take all the basic subjects similar to those around the world. These basic subjects are math, science, Japanese, Physical Education (P.E.), Home Economics, and English. People might notice a difference between Japanese and Western schools focusing on etiquette and civics.

For the first three years of school, students don’t take exams. Therefore, the core focus of education is on establishing good manners and developing character. Students are taught to respect each other, be generous, and be kind to nature.

The curriculum becomes more academically focused once they enter the fourth grade.

Japanese education heavily emphasizes equality above everything else. While many schools in the West quickly adopt the latest technology to give their students the upper hand, most National and Public schools across Japan are very low-tech.

Basic information technology courses are offered in national and public schools in Japan, but students are generally not allowed to use electronic devices in the classroom. This is to ensure equality among all students, regardless of income level.

In some countries, if students fail to perform adequately, they will likely be held back from further improving their skills. However, in Japan, students always advance to the next grade regardless of their test scores or performance.

In Japan, even if students fail tests or skip classes, they can still join the graduation ceremony at the end of the year.

School Life in Japan

Schools across Japan don’t have a janitorial staff. Students spend 10-15 minutes cleaning the school at the end of the school day. Similarly, right before any vacation, they’ll spend 30 minutes to an hour cleaning.

Once your child becomes a student, you’ll likely notice that they’ll start spending much of their free time at school due to their club activities.

School club activities ( bukatsu or 部活) are serious business in Japan. It’s a chance for students to create friendships and learn self-discipline, but they are known for taking up most students’ time. Students choose a club to join at the start of their first year, and they rarely change. Club activities happen all year round.

Aside from school clubs, students will have other activities throughout the year, such as sports day, school marathons, trips, and school festivals.

Each school is different in what sort of activities they have, but most schools will have a school festival. It’s a chance for students to work together and show off their talents to their families and friends in the area. It is usually the year’s biggest event, and students spend months preparing for the big day.

School Exams

Exams ( shiken or 試験) are a serious part of the Japanese education system. They measure not only a student’s overall learning of the material but also the schools they’ll be able to attend, starting from elementary school.

Students who want to attend junior high school, high school, and university must take entrance exams to get into those schools. And, of course, the very best schools require the highest test scores.

University entrance exams in Japan can also be particularly tough. Every February, about half a million students across Japan sign up to take them. Students who pass can look forward to acceptance from the university they applied to.

After graduating from high school, students who fail to get admission to their desired academic institution for the next level of education are called Rōnin (浪人). Rōnin is an old Japanese term for a masterless samurai. Such students must study outside the school system for self-study to prepare for the entrance test during the next academic year.

However, the Ronin students have the option to take admission in yobikō (予備校). Yobiko is a privately run school that prepares students for college admissions.

Even if you fail to get admission during the next 2-3 years, you can keep preparing because even good universities will accept you once you pass the admission test.

The education system is changing slowly as foreign companies introduce their own customs and practices. Since many Western companies hire employees based on skill, experience, and personality rather than test scores, many schools have adapted to de-emphasize the need for testing.

Higher Education in Japan

After finishing high school, many students continue their higher education at a university or a vocational school in Japan.

There’s a saying that students study hard in high school to relax in university. Attendance often isn’t required in university. Unfortunately, since many students have to endure strict rules in high school, university is seen as a time of rebellion, at least for the first two years.

Many students start their job search (shuukatsu or 就活) at the start of their third year. It may look strange to some Westerners, but wearing black suits and changing their hair to its natural color are expected norms to secure a job upon graduation.

Vocational schools have also become more popular in Japan. These Japanese vocational schools are typically only two-year courses. These institutions focus more on teaching the skills needed for a specific occupation. Upon graduation, students are awarded the title of advanced professional.

University Programs in Japan

Bachelor’s degrees.

Bachelor’s degree programs gakushi (学士) last at least four years. However, degrees in medical dentistry, pharmacy, and veterinary program extend to six years.

Most universities start their academic year in April and end in March the following year. The first semester is from April to September, and the second is from October to March .

Some Japanese universities offer flexibility in when international students can start their program, depending on the area of research. Bachelor programs require at least 124 credits to complete.

Eligibility for a Bachelor’s program in Japan as an international student requires the applicant to have completed at least 12 years of formal education in their home country.

Those without a formal education must pass the National Entrance Examination Test. School transcripts, a personal statement, and one to two letters of recommendation are also required.

Since many international programs are taught in English, prospective students must have completed 12 years of education in English.

Students who don’t qualify must prove their English language proficiency through tests like TOEFL or IELTS .

Programs taught in Japanese are also available to international students. However, students must prove their Japanese language proficiency at an intermediate level through either the Examination for Japanese University Admission (EJU) or the JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test) .

Master’s Degrees in Japan

Master’s programs or shuushi (修士) in Japanese universities combine lectures, research, student projects, and a written dissertation.

To be eligible for a Master’s degree, you must have completed a four-year bachelor’s program.

Along with university transcripts, applicants will likely need two letters of recommendation, a resume, and an outline of the research proposal.

Master’s programs in Japan last for two years and require 30 course credits to be completed.

There are several Master’s programs available in English in sciences, humanities, arts, and education. Before applying, you must provide proof of language proficiency for non-native Japanese speakers interested in enrolling in a Japanese-instructed program.

Doctorate Degrees in Japan

Doctoral programs or hakase (博士) is the highest level of academic study available in Japan.

Japanese Ph.D. programs are based on quality research and high-tech teaching techniques. Most doctoral programs in Japan last for a minimum of three years. As in any other country, admission requires completing a bachelor’s and master’s degree.

Japanese Research Programs

Students who don’t meet the university’s initial qualifications or are only interested in conducting research can enroll as a research student or kenkyusei (研究生) at a graduate school of their choosing.

Students are not eligible for academic credit or a degree upon completion of their research; however, this is an ideal route for students interested in enrolling in graduate programs before fully committing to a program.

Many students use this to improve their Japanese language skills before applying. To become a research student, applicants must receive approval from a prospective advisor of the school they wish to attend.

Scholarship Opportunities for Higher Education in Japan

Compared to the cost of university in America and many other countries, university tuition in Japan is quite reasonable.

The average tuition fee for Japanese universities is about $10,000 per academic year, but it can vary depending on the school .

Many university students rely on their families for financial support, but that might not be possible for international students. Scholarships are quite rare in Japan, but several scholarships are available to international students for various programs.

An important help during your scholarship application process is the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO) . JASSO provides student services and is responsible for scholarships, study loans, and support for international students.

You may like to check the following links for more information about the scholarships for university education in Japan:

- Japanese Government (MEXT) Postgraduate Scholarships

- The Monbukagakusho Honors Scholarship for Privately Financed International Students

- Japanese Grant Aid for Human Resource Development Scholarship

- Asian Development Bank Japan Scholarship Program

- Scholarships available through JASSO

Individual institutions also offer merit-based scholarships for international students. Be sure to check with the student offices for their qualifications.

Higher Education in Japan for Foreigners

Japan’s reputation for high educational standards makes it a great choice for international students to pursue higher education in Japan.

Japan is home to an array of technological innovations with a mix of traditional cultures, making it an attractive choice for higher education.

Although it’s not well known, many universities in Japan offer programs for international students. These programs are available primarily in English but also offer students a chance to learn the Japanese language and customs. We do have an article about English university education in and around Tokyo .

Japanese universities offer programs for Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Doctorate degrees in many different areas of study.

Why Study in Japan?

Japan has held a strong reputation for being the center of technology and innovation for quite some time, which is well reflected in its universities.

International experience also gives applicants a competitive edge over their competition. More employers value international experience as it shows drive and willingness to experiment. If your end goal is to work in Japan, starting as an international student allows you the chance to build a professional network.

Despite Japan’s reputation as a monolithic culture, many opportunities exist for non-Japanese students to study for higher education in Japan. The reputation of Japanese universities is well reflected at each institution, so any program you choose will be well worth your time.

Conclusion About the Education System in Japan

Education in Japan may seem a little different compared to your own culture. However, there’s no need to be alarmed about the quality of education, as Japan is often cited for having a 99% literacy rate .

Despite its emphasis on testing, the Japanese education system has been successful. Its strong educational and societal values are admired worldwide and produce some of the most talented students.

Moreover, for higher education, Japan offers a good mix of traditional and modern university programs that testify to its rich academic history and innovative future.

These programs provide top-notch education and a unique opportunity for foreigners to immerse themselves in the Japanese culture and way of life.

Pursuing higher education in Japan can be a transformative experience, bridging gaps between the East and the West. Japanese universities are a compelling destination for those seeking an academic adventure filled with learning, discovery, and personal growth.

Furthermore, Japan is a good destination for higher education if you wish to take advantage of its career growth prospects. With a continuously increasing demand-supply of talent because of its aging and declining population, Japan is a good destination for career growth prospects. Having a college education in Japan helps in achieving that goal more efficiently.

Jamila Brown is a 5-year veteran in Japan working in the education and business sector. Jamila is currently transitioning into the digital marketing world in Japan. In her free time, she enjoys traveling and writing about the culture in Japan.

- Japan Corner

- A Kanji a Day (69)

- Japanese Culture and Art (15)

- Working in Japan (13)

- Life in Japan (12)

- Travel in Japan (9)

- Japan Visa (7)

- Japanese Language & Communication (6)

- Housing in Japan (5)

- Medical care in Japan (3)

- Foreigners in Japan (2)

- Education in Japan (2)

- Tech Corner

- AI/ML and Deep Learning (25)

- Application Development and Testing (11)

- Methodologies (9)

- Tech Interviews Questions (8)

- Blockchain (8)

- IT Security (3)

- Cloud Computing (3)

- Automation (2)

- Miscellaneous (2)

Jobs & Career Corner

- Jobs and Career Corner

Let us know about your question or problem and we will reach out to you.

Employment Japan

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Become Our Business Partners

- Jobs & Career

For Employers

EJable.com 806, 2-7-4, Aomi, Koto-ku, Tokyo, 135-0064, Japan

Send to a friend

- My Favorites

You have successfully logged in but...

... your login credentials do not authorize you to access this content in the selected format. Access to this content in this format requires a current subscription or a prior purchase. Please select the WEB or READ option instead (if available). Or consider purchasing the publication.

- Education Policy Outlook

Education Policy Outlook 2021

Shaping responsive and resilient education in a changing world.

Education systems operate in a world that is constantly evolving towards new equilibria, yet short-term crises may disrupt, accelerate or divert longer-term evolutions. This Framework for Responsiveness and Resilience in Education Policy aims to support policy makers to balance the urgent challenge of building eco-systems that adapt in the face of disruption and change (resilience), and the important challenge of navigating the ongoing evolution from industrial to post-industrial societies and economies (responsiveness). Building on international evidence and analysis from over 40 education systems, this framework endeavours to establish tangible, transferable and actionable definitions of resilience. These definitions, which are the goals of the framework ( Why? ), are underpinned by policy components of responsiveness ( What? ), which define priority areas for education policy makers. Policy pointers for resilience ( How? ) then illustrate how policy makers can apply these components in ways that promote resilience at the learner, broader learning environment and system levels of the policy ecosystem. Finally, a transversal component looks into the people and the processes undertaken in order to reach a given purpose ( Who? ). The report has been prepared with evidence from the Education Policy Outlook series – the OECD’s analytical observatory of education policy.

- Résumé - Perspectives des politiques de l'éducation 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1787/75e40a16-en

- Click to access:

- Click to access in HTML WEB

- Click to download PDF - 4.70MB PDF

- Click to download EPUB - 8.50MB ePUB

Japan’s Third Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education sets out the goals for the entire education system in the period 2018-22, and defines a comprehensive approach to policy implementation. Its overarching aim is to ensure that the education system prepares learners for the world of 2030. As such, there is a focus on developing the skills required for the knowledge economy though the integration of information and communication technology (ICT) and problem solving into learning, as well as promoting lifelong learning and enabling learners to adapt to changes in the labour market. The plan builds on the success of the first and second basic plans for education, which include improving standardised test scores in lower-performing regions, implementing individualised learning and support plans for students with special educational needs (SEN), and reducing the cost of ECEC for low-income families. Outstanding issues from the previous two basic plans were taken into account when setting goals for the current plan. Key measures include strengthening school-community partnerships and reforming school leadership to allow teachers to focus their energy on teaching and to maintain Japan’s holistic approach to education with support from the community. There is also a focus on promoting collaboration between schools, and between the different services that sustain the well-being of learners. The implementation process involves systematically setting goals for education policies, developing indicators to monitor progress, and identifying measures to achieve these goals. Measures and goals of the Plan are refined on a continuous basis. Many activities are carried out by local actors, and local governments are encouraged to develop distinctive goals and measures based on their context.

- Click to download PDF - 731.78KB PDF

Cite this content as:

Author(s) OECD

18 Dec 2021

Selected indicators of education resilience in Japan

- Click to download XLS XLS

- Accreditation and Quality

- Mobility Trends

- Enrollment & Recruiting

- Skilled Immigration

- Asia Pacific

- Middle East

- Country Resources

- iGPA Calculator

- Degree Equivalency

- Research Reports

Sample Documents

- Scholarship Finder

- World Education Services

Education System Profiles

Education in japan.

Sophia Chawala, Knowledge Analyst, WES

Japan’s economy was once the envy of the world. From the ashes of World War II rose a nation that, in a little over two decades, became the world’s second-largest economy. The Japanese Miracle, a period of rapid economic growth lasting from the post-World War II era to the end of the Cold War, made Japan the global model to emulate in industrial policy, management techniques, and product engineering. The postwar period left no room for the country’s continued reliance on military-industrial production and development. To effect a rapid transformation, Japan had to reimagine and redefine its national image beyond its militaristic and industrial past, which for centuries had been the cornerstone of its economy and national identity.

But by the 1990s, Japan found itself beleaguered, stuck in its worst recession since World War II. Years of rapid economic growth had given way to decline and eventually stagnation. While Japan’s economy has improved marginally since that “Lost Decade,” many of the conditions underlying that decline remain. Others, most notably the growing economic and military threat from China and the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, have only grown.

Many analysts attribute Japan’s recent problems, particularly its slowing economy, to the country’s declining birthrates. In the 1970s, with the hyperactive economy causing the cost of living to rise and encouraging young men, and increasingly, women , to focus on their careers, birthrates began to fall. As a result, population growth slowed and eventually declined. According to the Statistics Bureau of Japan , 2019 marked the ninth year in a row of population decline. The population fell that year to 126.2 million, a decrease of 276,000 (0.22 percent) from the previous year. At the same time, improved health care caused life expectancy to rise—Japan’s population today enjoys one of the longest life expectancies in the world—and Japan’s elderly population numbers to swell. Around 28 percent of Japan’s population is over the age of 65, the highest proportion of that age cohort of all the countries in the world.

These demographic trends have had serious economic consequences. A shrinking workforce has complicated efforts to recover from the 1991 collapse in asset prices, leading to a prolonged economic recession, the effects of which are still being felt today. The employment outlook for many of the country’s youth has also deteriorated, with weak economic growth, an aging workforce, and the unique employment practices of most Japanese companies—workers in Japan are often hired for life with salaries highly correlated with seniority—forcing Japanese companies to “ refrain from hiring new regular workers and to increase their reliance on irregular workers.” The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated these issues, with one analyst predicting a “steep recession” and warning that the health crisis would deal the “final blow” to Japan’s economy.

Its sluggish economic performance has afforded Japan’s rapidly developing neighbors time to catch up to and, in China’s case, surpass Japan. In 2010, China succeeded Japan as the world’s second-largest economy , a status Japan had held since 1968. This milestone also symbolized a rebalancing of power in East Asia, with China increasing its pursuit of foreign policy goals that Japan views as a threat to its national security. China has increased its military presence around the strategically important Senkaku Islands, or as they are known in China, Diaoyu Islands , control over which Japan and China have disputed for decades. China’s growing economic strength has also allowed Beijing to pursue its strategic goals through trade agreements, international investment, and access to supply chains and its massive domestic market.

To counter the rising influence of China, Japan has turned its eyes to the rest of the world, nurturing strategic alliances with large Western powers like the United States. It has also introduced measures aimed at fueling economic growth and innovation. The Japanese government has sought to promote technological advances, increase economic links with other East and Southeast Asian countries, and diversify its workforce for a more globalized and fast-paced future. Like many other countries that have sought to diversify their workforce in the face of global crises, the Japanese government has investigated reforming certain components of its education system.

The Backdrop to Reform: Japan’s Educational Performance

Education is one of the most important aspects of Japan’s national identity and a source of pride for Japanese citizens. The country’s high-quality education system has consistently won international praise. An emphasis on the holistic development of children has for decades led Japanese students to achieve mastery in a variety of academic disciplines—their performance in science, math, and engineering is particularly noteworthy. In the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2015, Japan ranked second in science and fifth in math among 72 participating countries and regions .

The school system also still embodies the values of egalitarianism, harmony, and social equality, which were highlighted as early as the first postwar education law, the 1947 Fundamental Law of Education , also translated as the Basic Act on Education. According to the OECD, Japan ranks highly among wealthy nations in providing equal opportunities to students of all socioeconomic backgrounds. Only 9 percent of variation in performance among compulsory school students is explained by socioeconomic hardship, about 5 percent below the OECD average.

Despite international praise for Japan’s educational system, many of the system’s underlying principles have come under increasing scrutiny in recent decades. The educational system has become the focus of increasing discontent because of its perceived rigidity, uniformity, and exam-centeredness. The extent to which the country has succeeded in providing equal access to education is also being questioned, especially when its selective, competitive tertiary level is considered. The gap in access to higher education between the upper and lower classes is widening alongside growing income inequality. While most obvious at the higher education level, this inequality is growing at each educational stage and is driven by several variables including the proliferation of private preschools and senior high schools, the growth of exclusive institutions aimed at preparing students for university and high school entrance examinations, and rising tuition fees at higher education institutions (HEIs). These challenges, combined with the need to provide education and training relevant to the expanding knowledge economy, have prompted renewed calls for education reform.

Education Reform: Past and Present

Education reform in Japan is not new. Western education systems came to influence Japanese education shortly after the 1868 Meiji Restoration, which transferred effective political power from the Tokugawa shogunate to the emperor, ushering in an era of modernization across all sectors of Japanese society. In 1872, Japan’s newly established Ministry of Education adopted from the American school system the three-tier elementary, secondary, and university structure, and from the French, strong administrative centralization. A group of newly established Imperial Universities took on certain aspects of the German university model . Despite those early international influences, domestic resistance to outsiders quickly followed, intensifying sharply during World War II.

But following Japan’s surrender in 1945, foreign influence on the educational system resumed, with all national reform and revitalization efforts falling under the aegis of the occupying Allied powers, led largely by the U.S. Of all the areas identified for reform, Allied personnel and the newly installed Japanese cabinet considered educational reform to be the most important, expecting it to play a principal role in channeling the thoughts and beliefs of the Japanese people in a more liberal and democratic direction. In 1946, the Educational Reform Committee laid out what would remain the core issues for Japanese education ministers until well after the years of occupation. The committee identified three issues as top priorities: the decentralization of educational administration, the democratization of educational access, and the reform of the educational curriculum.

Although occupation ended in 1952, it was not until the late 1980s and early 1990s that Japan’s economic slowdown and growing integration in the global economy solidified these priorities as essential cornerstones of Japanese policy and national identity. The unexpected economic decline made it clear to Japanese policymakers that remaining competitive on the global stage would require a highly skilled and educated workforce, able to increase worker productivity and drive technological innovation. In response, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) stepped up its reform efforts, focusing on democratization, decentralization, and internationalization with the goal of developing a new generation of globalized and resilient Japanese youth. As occurred at earlier stages in the country’s history, these reforms have sought to balance modernization with respect for tradition. Current reforms are shaped both by an openness to ideas found in the educational systems of other countries and a deep respect for long-held values and principles, especially those of societal honor, communal harmony, and self-sacrifice.

While the reforms have produced some positive results for Japan, they are not without their shortcomings. The OECD’s 2018 report, Education Policy in Japan: Building Bridges towards 2030 , warns that the reforms, though well regulated and well-intentioned, risk being “adopted only as superficial change.” The content and success of these reforms will occupy much of the discussion below.

Student Mobility

For years, Asian countries have sought to even out imbalances in inbound and outbound student flows—historically, the region has sent out more students than it brings in. For many of the region’s countries, such as China, the effort to erase that imbalance has meant putting in place policies and programs aimed at effecting a transformation from mere sources of international students to educational destinations of choice in their own right. Japan is no stranger to the desire to balance inbound and outbound numbers. However, with more inbound than outbound students, Japan has, somewhat uniquely, often had to work harder to promote outbound mobility than many of its neighbors.

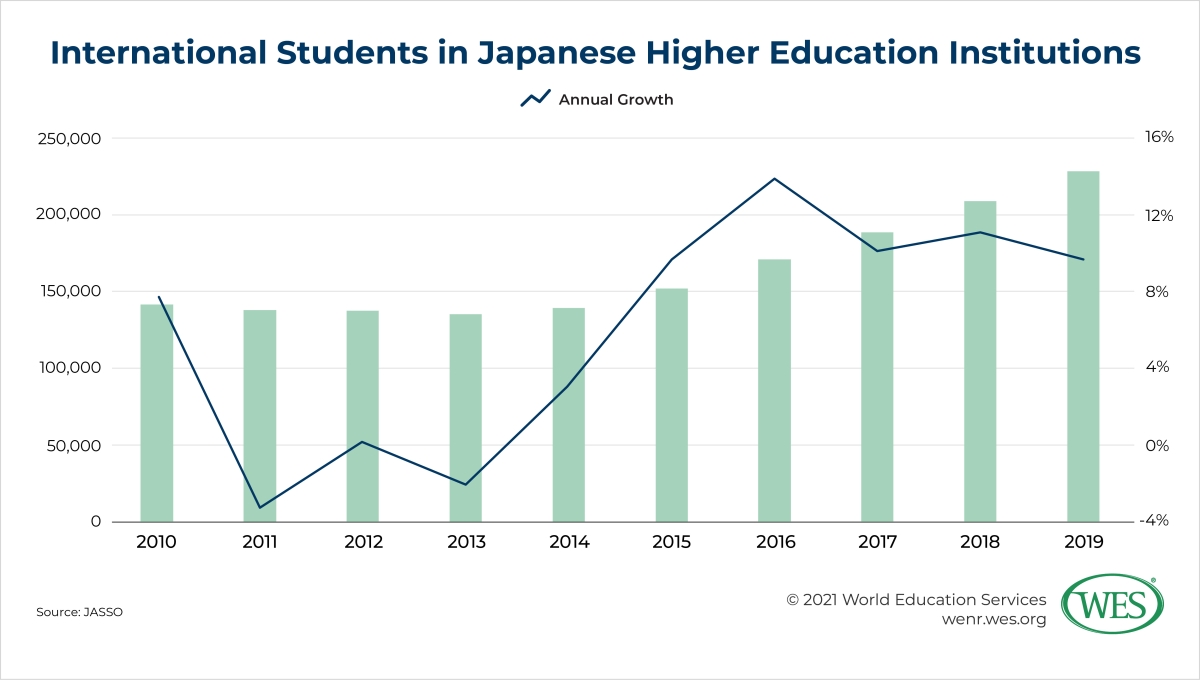

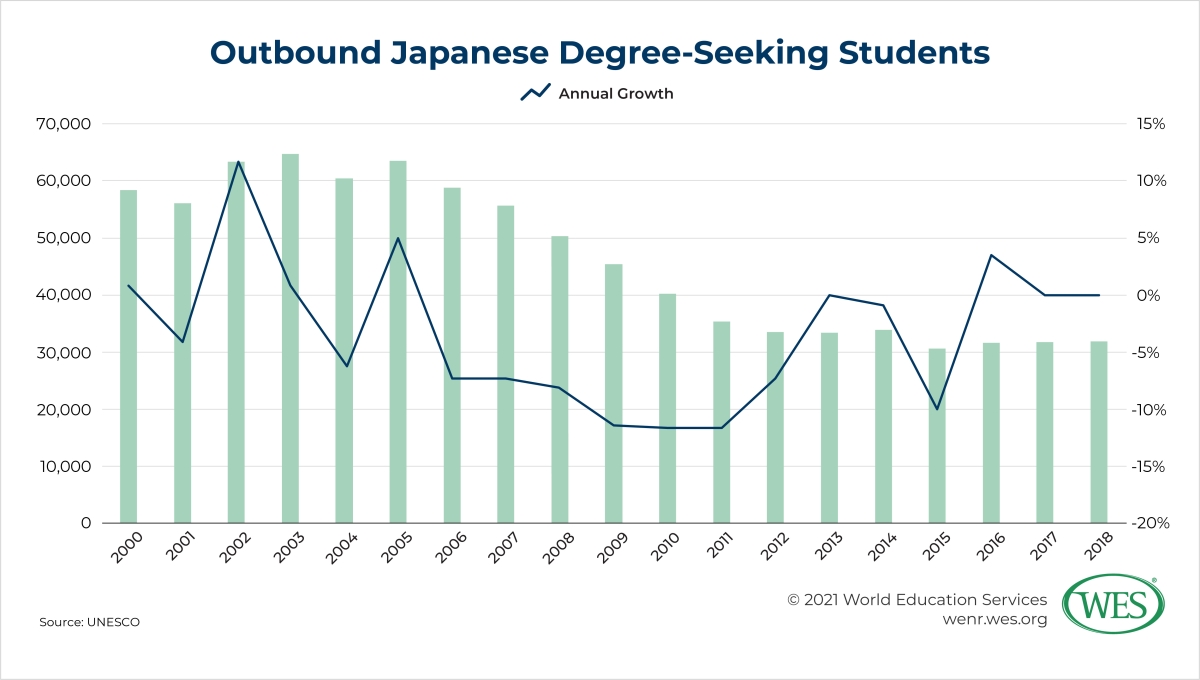

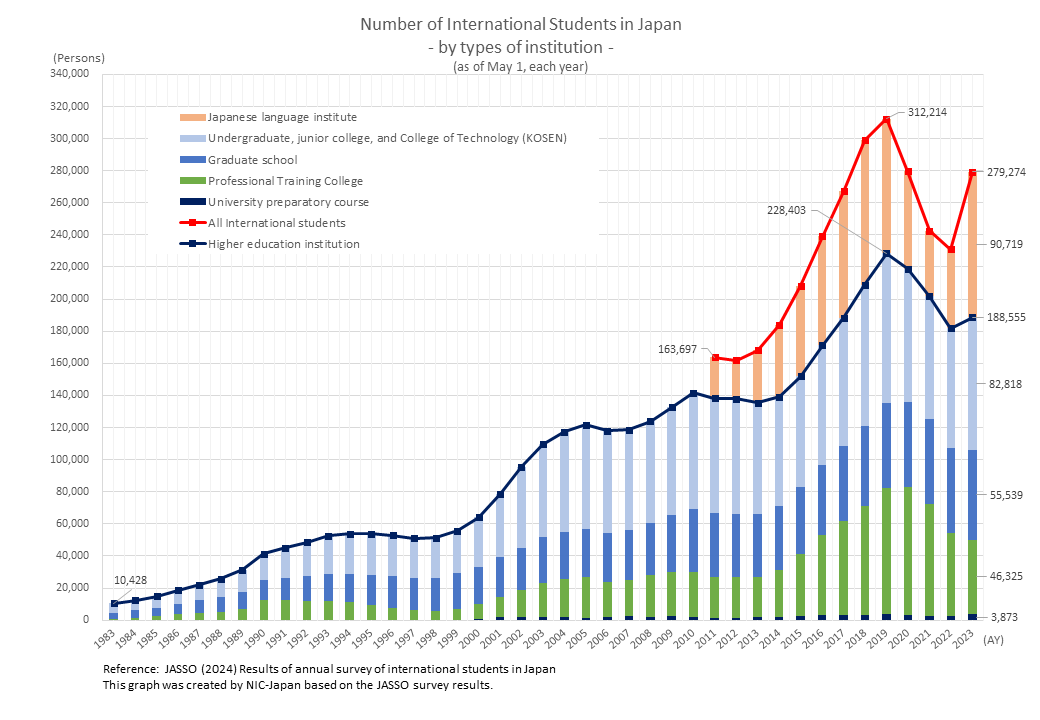

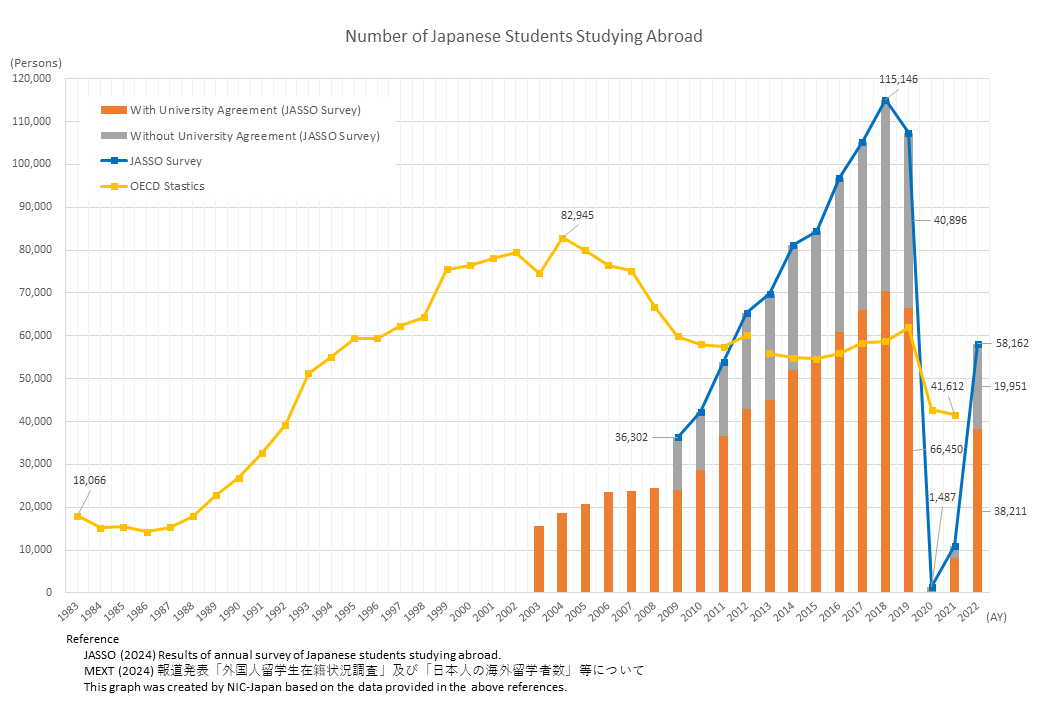

One notable priority of the MEXT’s 2013 National Education Reform Plan was the promotion of internationalization by raising total numbers and softening the imbalance between outbound and inbound student mobility, among other initiatives. To increase outbound mobility, the government set a goal of doubling the number of Japanese students studying abroad , from 60,000 in 2010 to 120,000 in 2020. For inbound mobility, the government sought to attract 300,000 international students by 2020 . Observers view increasing the number of inbound and outbound students as central to the nation’s economic development plans . After graduation, talented international students can help fill positions left empty by Japan’s shrinking domestic workforce, while the internationalized education received by Japanese students studying abroad can be leveraged by the country’s corporations and national government to further trade and diplomatic ties.

Inbound Student Mobility

With Japan’s aging population causing university admissions to decline, the Japanese government has launched several initiatives to attract foreign students; the Study in Japan Global Network Project (GNP) is one. A global recruiting initiative co-managed by MEXT and the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO), the GNP helps Japanese universities establish overseas bases in key regions, such as the Middle East, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa, and South America, from which they can directly promote the benefits of studying in Japan to prospective international students. GNP also allows staff members of university overseas offices to visit high schools in various countries to recruit students, prioritizing those schools that have previously sent students on exchange trips or study abroad programs to Japan.

Other initiatives include CAMPUS Asia , an East Asian regional initiative aimed at promoting the cross-border mobility of students from Korea, Japan, and China through student exchanges and institutional partnerships. Internationalization efforts undertaken by individual universities and educational associations, such as the Global 30 Project , also seek to attract international students to Japan. Currently, the Top Global University project, an initiative of MEXT, supports internationalization efforts at 37 of the country’s top universities. At the selected universities, the project seeks to promote international academic and research partnerships, increase the number of courses offered in English, and facilitate the recruitment of international students and faculty, among other objectives.

Some Japanese universities have also begun adding study abroad requirements to their programs and adopting an academic curriculum and semester system conducive to overseas study. For example, in 2016, Chiba University made overseas study a graduation requirement for all students in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, introducing at the same time a six-semester academic calendar to accommodate it. In 2020, the university made study abroad mandatory for all students university-wide.

These initiatives have been met with considerable success. By one measure, Japanese universities reached the 2020 enrollment targets set by the government a year early. According to JASSO , which includes in its measures international students enrolled in non-university, Japanese language institutes, more than 312,000 international students traveled to Japan to study in 2019.

Measuring just university enrollments, the number enrolled in HEIs reached more than 228,000 that same year, up nearly 70 percent from 2013. Over 90 percent of those students came from other Asian countries, with students from China and Vietnam alone accounting for nearly two-thirds of all international students in Japan.

Still, despite these promising results, Japan’s inbound mobility rate remains low compared to that of other developed countries. Although increasing by more than a third over the previous decade, Japan’s inbound mobility rate stood at just 4.7 percent in 2018. Several obstacles hinder efforts to increase international student enrollments, most notably, language. Despite attempts to increase their English language offerings, few programs in Japanese universities are taught in English, a situation that forces many interested international students to undergo intense Japanese language training prior to the start of their studies. Another barrier is student uncertainty surrounding the in-country employment pathways available to international students earning Japanese credentials, a lack of clarity that raises concerns about the value of Japanese higher education to international students. To facilitate international students’ transition from the university to the workplace, national universities have begun hosting monthlong internships in cooperation with local governments and private companies.

Differing Measures of Student Mobility: Short Term vs. Full Time

Various organizations in Japan differ in how they define international students and in how they measure outbound and inbound student mobility, so reported international student numbers can differ widely. Some organizations, such as JASSO, consider short-term study abroad programs as a barometer of success, and measure student mobility numbers accordingly. JASSO defines the act of studying abroad as participation in any post-secondary educational program, a definition that includes not only formal university programs, but also language and cultural programs. While government agencies like MEXT and intergovernmental organizations like UNESCO are primarily concerned with full-time higher education enrollment, JASSO’s numbers also reflect Japanese university students pursuing short-term exchange programs abroad, often for six months or less. The pool of students measured by the Japan Association of Overseas Studies (JAOS) is even broader. When measuring and reporting outbound student mobility numbers, JAOS includes students going abroad for secondary education in addition to those in degree programs and short-term language and exchange programs. Another common means of evaluating Japanese outbound mobility rates is through the lens of university exchange agreements. As of 2017, the top three destinations for Japanese students participating in institutional exchange programs were the U.S., Canada, and China.

Chinese Students in Japan

China’s economic growth since the start of the millennium has greatly benefited Japan’s education sector. Despite long-standing tensions between East Asia’s two largest economies, Chinese students currently make up the largest portion of international students studying in Japan. In 2019, four in ten international students in Japan were from China.

Per the UNESCO Institute of Statistics , the number of Chinese students studying in Japan peaked at 96,592 in 2012, up from 28,076 in 2000, an increase of more than 300 percent. Analysts attribute this growth to “ a nexus of factors ,” including “the popularization of educational mobility during China’s reform era” and “Japan’s efforts to attract students from overseas.” China’s cultural and physical proximity to Japan likely also plays a role, as do regional exchange initiatives, such as CAMPUS Asia, discussed above.

Given China’s growing middle class, the latest generation of Chinese students in Japan is more affluent and aspirational, largely self-financing their overseas studies. However, China’s economic growth and own improving HEIs mean that more students are willing and able to study further afield or at home. Since their peak in 2012, Chinese enrollments in Japan have declined, falling to 84,101 in 2018.

Outbound Student Mobility

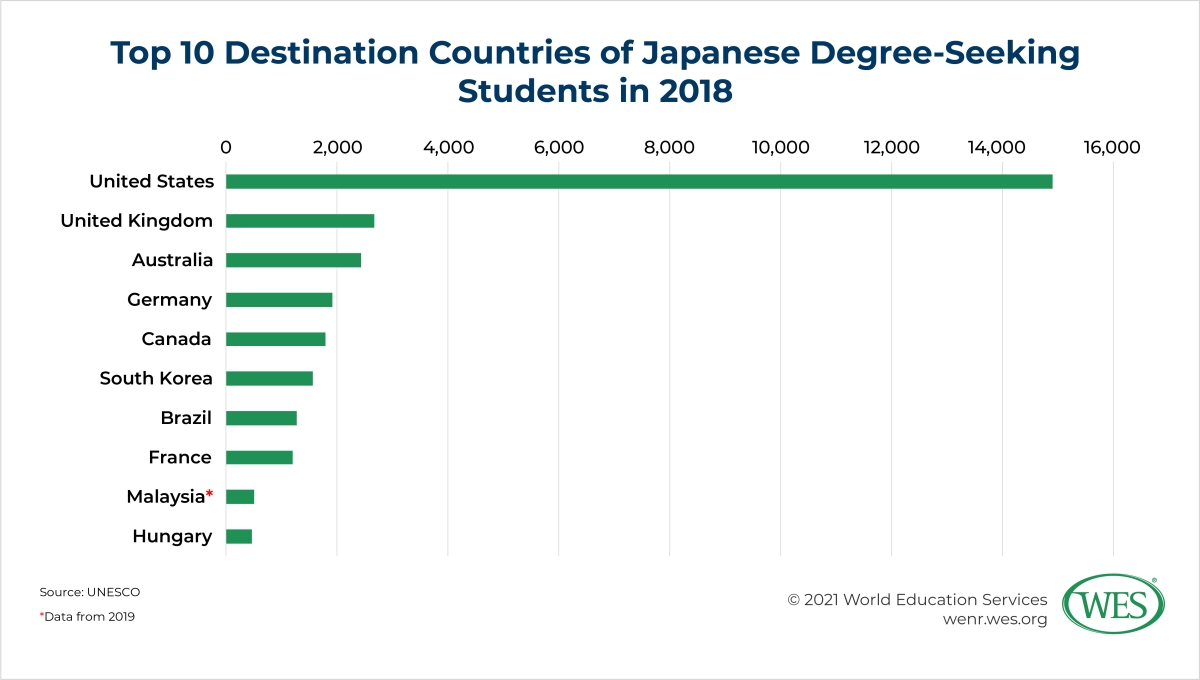

Outbound mobility, as measured by JASSO, is just under the government’s goals. According to JASSO , more than 115,000 Japanese students studied overseas in 2018, up from just under 70,000 in 2013. However, far fewer Japanese students are pursuing a full degree program at an overseas university. According to UNESCO, less than 32,000 degree-seeking tertiary students studied overseas in 2018, less than 1 percent of all Japanese tertiary students .

Japan has never been a major source of globally mobile students. But, around 2005, after decades of low population growth, outbound mobility began a sharp and swift decline. According to UNESCO data, by 2018, outbound student numbers had fallen by nearly half their 2005 level (63,492).

While low birthrates are widely recognized as a key driver of Japan’s low outbound mobility rate, some experts also attribute the low rate to some of the country’s unique cultural characteristics. Students from other Asian countries that have low and declining birthrates, like South Korea and China, study overseas at far higher levels than those of Japanese students. Some Japanese experts , including government officials, attribute the low rates of study abroad to the “inward-looking mindset” of the country’s students, a state of mind known in Japanese as Uchimukishikou . In everyday usage, the term describes an internal, psychological state stemming from personal lack of interest; a state that combines intimidation, fear, and inhibition typically felt when confronting an uncertain and highly consequential event. But the Japanese government has elevated the term to national prominence, employing it to explain a lack of overall interest among Japanese students in overseas study or work. Other trends within Japan’s borders likely contribute to low outbound student numbers, such as the growth of domestic higher education opportunities, the expansion of doctoral programs and student grants, and the increasing availability of English language training in Japan.

Those students who do study overseas tend to head to English-speaking countries. According to UNESCO, four of the top five destinations in 2018 were English speaking: the U.S., the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada. In Germany, the only non-Anglophone country in the top five, English language university programs are widely available. In recent years, German universities have greatly increased the number of master’s and doctoral programs taught in English .

Japanese Students in the U.S. and Canada

Historically, Japan has been one of the leading countries of origin for international students studying in the U.S. Each year since 2000, according to IIE Open Doors data , Japan has been one of the top 10. The popularity of the U.S. among Japanese students stems in part from long-standing ties between the governments of both countries. Since the signing of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan in 1951, Japan has been aligned strategically and militarily with the U.S. The resulting atmosphere of cooperation and mutual goodwill has helped nurture an abundance of educational exchange programs , such as the U.S. Embassy’s TeamUp campaign which fosters “institutional partnerships between U.S. and Japanese colleges and universities to facilitate student exchange.” Another project, the TOMODACHI Initiative , a public-private partnership developed in the wake of the devastating 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, has facilitated thousands of educational and cultural exchanges for American and Japanese citizens.

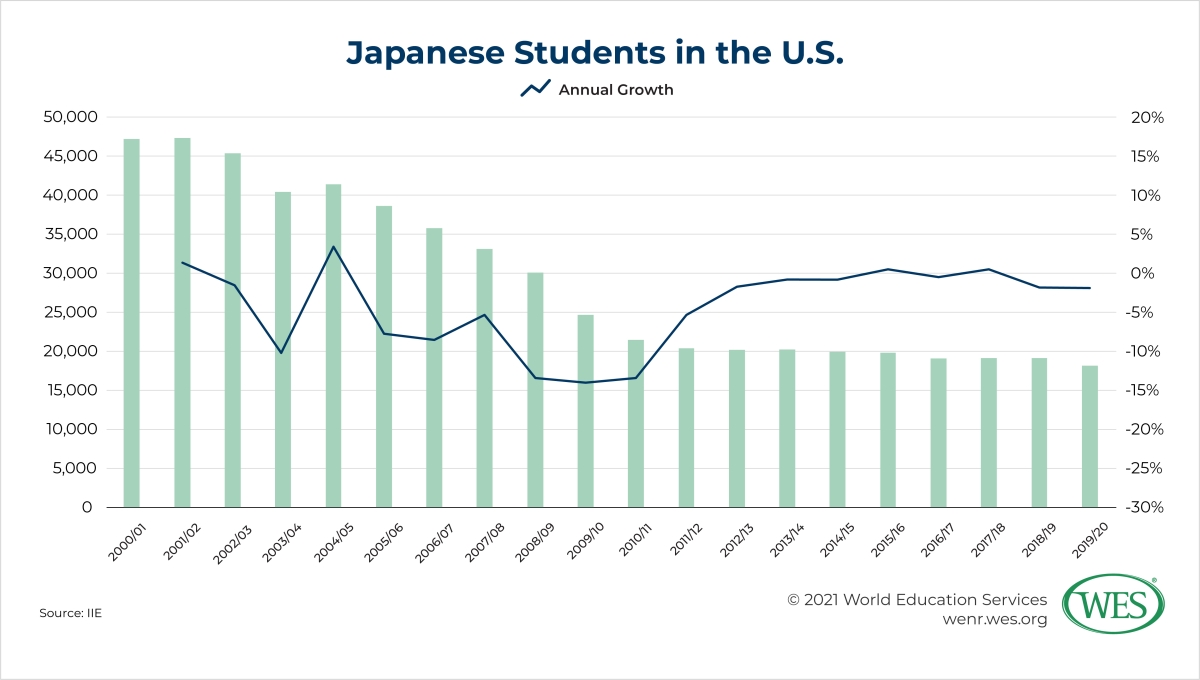

That said, since 2000, Japanese enrollment in U.S. higher education institutions (HEIs) has declined sharply. According to Open Doors , the number of Japanese students studying in the U.S. during the 2019/20 academic year was 17,554, falling from a high of 46,810 in 2001/02. Growth has been negative in all but two years since 2000/01.

Nearly half (49 percent) of the Japanese students that are in the U.S. are enrolled at the undergraduate level , while 26 percent are registered in non-degree programs, 16 percent in graduate programs, and 8 in the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program. Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs (18 percent) are the most popular field of study for these students , followed by business and management (17 percent) and intensive English (14 percent) programs.

There has been much speculation on the reasons behind the downturn in the number of Japanese students in the U.S. Among the proposed theories are feelings of hesitation and unease about studying abroad stemming from crucial differences between Japanese and U.S. education systems.

Differences in the academic calendar may prove an obstacle to Japanese students hoping to study abroad. Since the beginning of the Meiji era, Japan has always matriculated and enrolled students in the spring, a season closely associated in Japanese culture with new beginnings. There have been recent debates on whether schools should shift the start of the year to the fall to align with most other countries in the world. However, such plans have never come to fruition because of the heavy cultural implications associated with the start of the school year and the uncertainty surrounding the consequences that such a change would bring. A change to the academic calendar would not only complicate the graduation timeline of Japanese students, it would also complicate their job search. Traditionally, the job-search process for Japanese college students starts in the fall of their penultimate year of study, or the second semester of their junior year.

For Japanese students choosing to study in the U.S., the country’s fall to spring academic calendar could delay the job-search process. Furthermore, students who studied abroad or possess a degree from the U.S. are not guaranteed a leg up in the domestic job market in Japan. Rather, potential employers in Japan have negatively judged returning students for their inability to readjust to the norms of the Japanese workplace.

Another challenge for Japanese international students on short-term study abroad programs is the recognition of their international academic coursework. Credits earned at overseas universities through exchange or short-term study abroad programs are often not recognized at Japanese universities. Finally, soaring tuition fees at HEIs worldwide, and especially those in English-speaking countries, are of great concern to Japanese students.

These differences are also likely to present obstacles to Japanese students thinking about studying overseas in countries other than the U.S. Still, the recent experience of Canada seems to tell a different story.

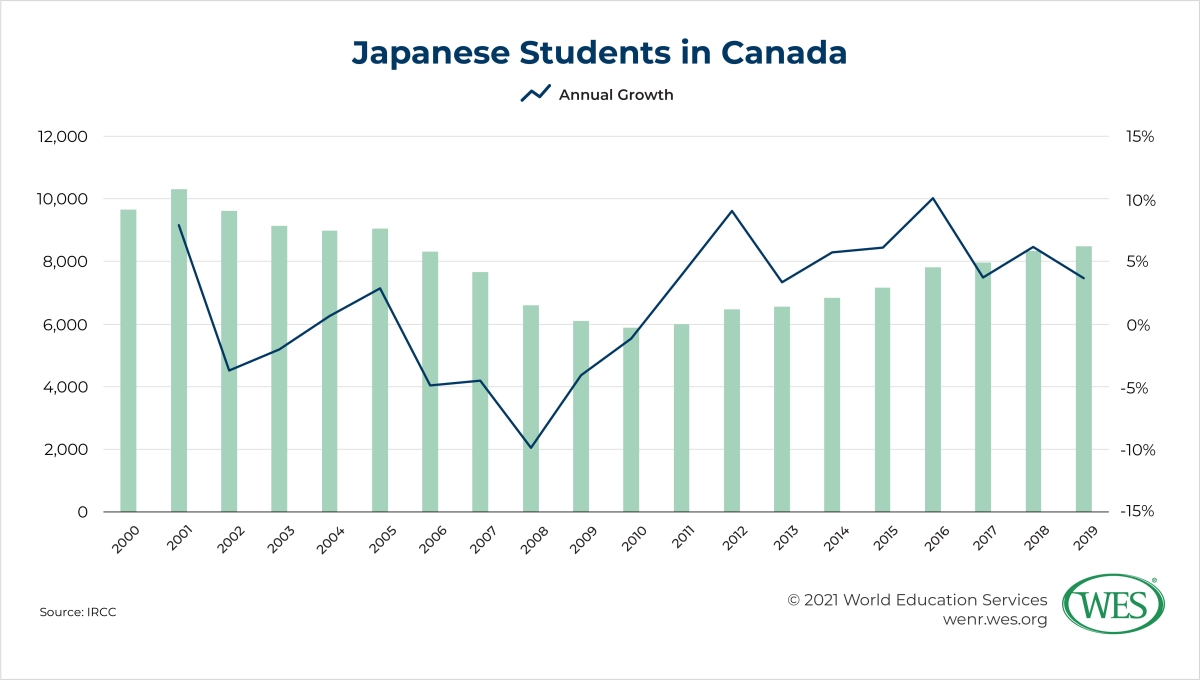

In contrast to the U.S., where the number of students has continued a long-standing decline in recent years, the number of Japanese students studying in Canada has increased, albeit at an uneven rate. According to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), the number of Japanese students with study permits reached a high of more than 10,000 in 2001, before a nearly unbroken, decadelong decline brought numbers to a 20-year low of less than 6,000 in 2010.

Enrollment numbers began to rebound in 2011. They were given an additional boost by then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s 2013 policy goal of doubling outbound student mobility, mentioned above. MEXT, which measures international student numbers differently from Canada’s IRCC, reported that between 2013 and 2015, there was a 24 percent increase in outbound mobility to Canada, from 6,614 to 8,189 students. The increase in outbound mobility to Canada outpaced both overall Japanese outbound mobility growth and Japanese mobility growth to the U.S., which grew 21 percent and 11 percent, respectively.

Several factors are likely driving the divergence in growth trends between the U.S. and Canada. Canadian universities offer many of the same benefits of U.S. universities, with few of the drawbacks. Japanese students, like students from other countries around the world, are increasingly drawn to Canada’s high-quality and relatively affordable colleges and universities. A 2017 MEXT survey also found that Japanese students and parents prioritize public safety. Canada is widely perceived as a safer study destination than the U.S. Previous WES research revealed widespread concerns among international students in the U.S. about gun violence both at their institution and in the surrounding community.

In Brief: The Education System of Japan

The structure of Japan’s education system resembles that of much of the U.S. , consisting of three stages

of basic education, elementary, junior high, and senior high school, followed by higher education. Most parents also enroll their children in early childhood education programs prior to elementary school. Children are required to attend school for nine years—six years of elementary education and three years of lower secondary education. At the primary and secondary levels, the school year typically begins on April 1 and is divided into three terms: April to July, September to December, and January to March.

High educational outcomes have earned Japan’s educational system a sterling reputation on the global stage, especially at the elementary and secondary levels. On worldwide assessments of educational attainment, the country consistently scores above average in educational performance, participation rates, and classroom environment. In the OECD’s 2018 PISA , 15-year-old Japanese students scored 16 points above the OECD average in reading and literacy, 36 points higher in mathematics, and 38 points above in science.

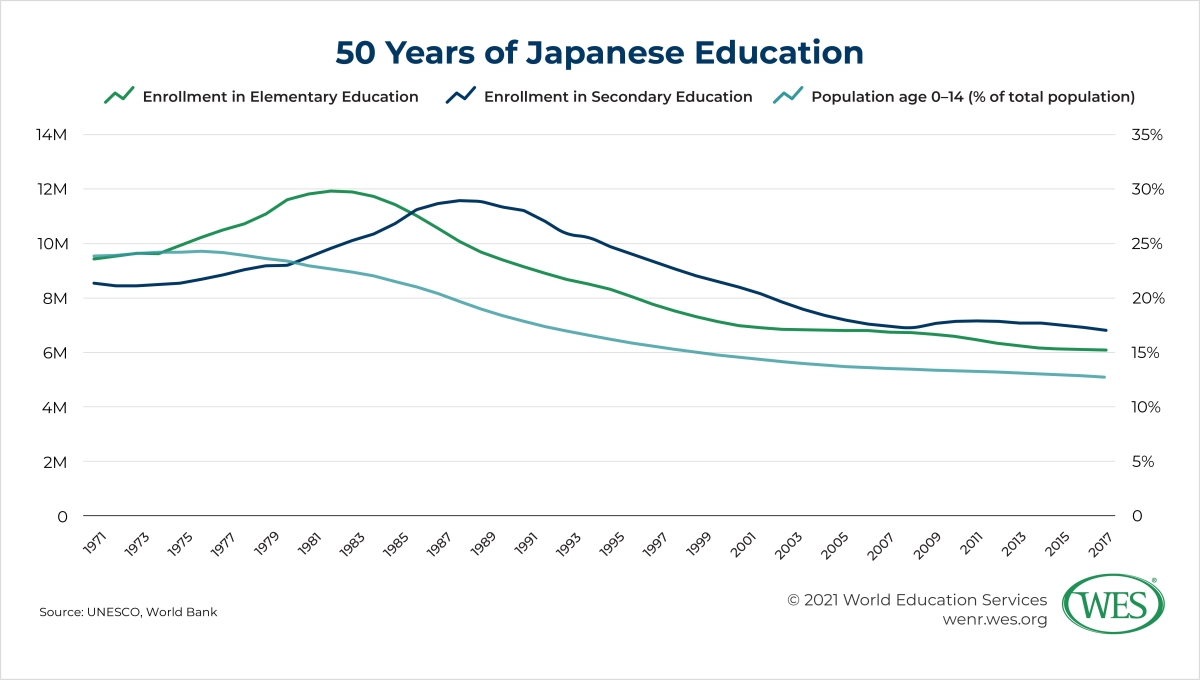

That said, Japan’s education system faces a number of challenges, among the most significant of which are demographic aging and enrollment declines. Elementary and secondary enrollment peaked in the 1980s, with elementary enrollment reaching a high of nearly 12 million in 1982, and secondary enrollments, a high of over 11.4 million in 1988.

Since then, enrollment at both levels has declined sharply. In 2018, the latest year for which data were available, elementary enrollment had fallen to just under 7 million, and secondary enrollment to around 6.5 million. That decline has closely tracked the country’s aging population. After reaching 24 percent in 1976, the percentage of the Japanese population age 0 to 14 declined steadily, falling to 13 percent in 2018.

The ramifications of these declines have rippled outward to affect nearly all aspects and levels of Japanese education, society, and economy. The following sections will not only explore the varying impact of demographic trends on different levels of education in Japan, they will also outline the structure and content of each level of education, other current challenges, and important reforms and modifications that are aimed at mitigating internal and external pressures.

Administration of the Education System

Responsibility for educational administration and policy development is divided between government authorities at three levels: national, prefectural, and municipal. At the national level, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), or Monbu-kagaku-shō , is responsible for all stages of the education system, from early childhood education to graduate studies and continuing, or lifelong, learning. MEXT ensures that education in Japan meets the standards set by the 1947 Fundamental Law of Education which stipulates that the country provide an education to all its citizens “that values the dignity of the individual, that endeavors to cultivate a people rich in humanity and creativity who long for truth and justice and who honor the public spirit, that passes on traditions, and that aims to create a new culture.” To fulfill that mandate, MEXT sets and enforces national standards for teacher certification qualifications, school organization, and education facilities, among others. It provides a significant portion of the funds for public schools, universities, research institutions, and, under certain circumstances, issues grants to private academic institutions. MEXT is also typically responsible for the development of national education policies, although in recent decades prime ministers have often convened ad hoc councils to determine education policy.

At the elementary and secondary levels, MEXT develops national curriculum standards or guidelines ( gakushū shidō yōryō ) which contain the “ basic outlines of each subject taught in Japanese schools and the objectives and content of teaching in each grade.” Typically, private educational publishers develop and print textbooks following these guidelines. Elementary and secondary schools can only use textbooks reviewed and approved by MEXT, which provides textbooks to students free of charge.

Although MEXT revises the curriculum guidelines roughly once every 10 years, their overall structure and objectives have remained more or less the same since 1886. Since then, curriculum guidelines have emphasized standardization, objectivity, and neutrality to avoid divisive political, factional, and religious issues. While this emphasis may lead one to assume that the national government strictly limits and controls educational content and teaching methods, in theory, these guidelines are only intended to establish nationally uniform standards of education, allowing students throughout the country access to an equal education. The system is designed to give teachers the freedom to develop individualized lesson plans and tests. Still, comparisons with other OECD countries suggest that Japanese teachers have limited control over classroom instruction and curriculum. Among the recent concerns cited as limiting the freedom of Japanese teachers is the 2007 introduction of a national academic achievement test. Observers note that in order to reach achievement test targets, local schools and educational authorities have tightened control over teaching methods and educational content.

At the prefectural and municipal levels, the external influences mentioned in the introduction are readily apparent. In the post-World War II era, democratization and the decentralization of education were core issues of educational reform, spurring the Japanese government to adopt the system of boards of education common in the U.S.

Japan is divided into 47 prefectures, each of which is composed of smaller municipalities, such as cities, towns, and villages. Boards of education, representative councils responsible for the supervision of education at the elementary and secondary levels, exist at both the prefectural and municipal levels. At the prefectural level , governors appoint members to five-member boards of education for terms of four years. Prefectural boards are responsible for appointing teachers and partially funding municipal operations and payrolls, including funding for two-thirds of teachers’ salaries, with the remaining third financed by the national government. At the municipal level, members are appointed by local mayors. Municipal boards are responsible for the supervision of day-to-day operational tasks at elementary and junior high schools, the management and professional development of teachers, and the selection of MEXT-approved school materials.

A 2015 reform of the board of education system—the first such reform in nearly 60 years—expanded the control of local chief executives, such as governors or mayors, over educational administration and planning, and reduced the role of boards of education. Authority to appoint the superintendent, the most powerful local educational authority, was transferred from the board of education to the local chief executives. The reform also increased their authority to determine local policy goals—it transferred authority to establish the local education policy charter to chief executives, reducing boards of education to an advisory role. Reformers hope the changes will lead to improvements in a system long criticized for its lack of transparency, accountability, and clearly defined roles and responsibilities.

Early Childhood Education

Traditionally, two principal forms of early childhood education (ECE) have existed in Japan: kindergarten ( yōchien ) and day care ( hoikuen ). Under the jurisdiction of MEXT, yōchien is a non-compulsory stage of the country’s educational system, coming immediately before elementary school, providing preschool education to children from the ages of three to six. Children typically attend yōchien for around four hours each day. As at other levels of Japan’s basic education system, MEXT develops and publishes curriculum standards for kindergartens, which must meet criteria necessary for the curriculum to realize the nation’s educational goals. The latest, issued in 2017 , seeks to foster a “zest for living,” a goal pursued at all levels of the educational system, and lay the groundwork for learning at the elementary level and beyond.

Administered by a different ministry, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare , hoikuen exists outside the Japanese educational system. Its principal function is to provide basic childcare services for children age one to six while their parents are at work. Typically lasting for eight hours, or the length of a typical working day, hoikuen often include some educational elements like reading and math.

Both yōchien and hoikuen centers can be owned and operated by public or private bodies, such as local municipalities, educational corporations, or non-profit organizations. However, the majority of students enroll at private institutions, some of which are highly selective and expensive. Many parents believe that enrolling their children in these highly selective institutions increases their children’s chances of being admitted to more selective institutions later in their educational career. In fact, some yōchien and hoikuen centers even prepare students for admissions tests at private elementary schools.

With more and more Japanese mothers entering the workforce, yōchien kindergarten programs, which have traditionally provided educational supervision for only part of the day, have in recent years faced

difficulty maintaining enrollment numbers. For the same reason, the demand for full-day hoikuen services has been on the rise. Historically, there have been long, persistent waitlists for parents hoping to enroll their children in hoikuen centers.

Given the clear demand for full-day childcare services, more and more yōchien have begun to adopt the day care elements more typical of hoikuen centers. For example, some yōchien have begun to offer extended hours to meet the demands of working parents, not ending their classes until the end of the workday. Some local governments have also started combining yōchien and hoikuen centers and mandating enrollment for all children prior to elementary school. The national government has even introduced measures merging childcare and early childhood education services into a single facility known as nintei-kodomoen . However, because of conflicting ministerial jurisdictions, reform efforts have often been stymied by administrative complications and are yet to achieve widespread success.

Still, early efforts at reform, combined with declining birthrates, have proved effective in reducing hoikuen waitlists. In 2019, waitlists for day care facilities reached an all-time low, with just under 17,000 children waiting to enter day care, a decrease of more than 3,000 children from the previous year.

Elementary and Lower Secondary Education

Elementary education marks the beginning of compulsory education for all Japanese children, lasting six years and spanning grades one to six. Children enter elementary education provided they reach age six as of April 1.

The elementary curriculum emphasizes both intellectual and moral development. All students must take certain compulsory subjects , like Japanese language, mathematics, science, social studies, music, crafts, home economics, living environment studies, and physical education. For public school students in grades five and six, English has been a compulsory subject since 2011. Since 2020 , English has been mandatory starting in third grade. Moral development is promoted through a moral education course and informal learning experiences designed to inculcate respect for society and the environment. The importance of moral education—long a taboo subject given its association with the nationalistic excesses of Imperial Japan—to Japan’s educational policies has increased over the past few decades. In recent years, the reintroduction of moral education as a formal course was spurred by reports of rampant student truancy, bullying, and school violence.

Classes remain large by international and OECD standards , despite efforts by MEXT to improve student-teacher ratios and recruit additional instructors. In 2011, MEXT limited first grade classes to 35 , down from 40, although intentions to extend similar limitations to other grades subsequently failed. Nearly all the country’s elementary schools, known as shōgakkō , are public. Enrollment at public elementary schools is free.

Students completing the elementary education cycle are awarded the Elementary School Certificate of Graduation (s hogakko sotsugyo shosho ) and automatically accepted into public junior high school.

Lower secondary education, the final stage of compulsory education, lasts three years, comprising grades six to nine. Instruction is conducted at junior high schools, or chūgakkō , 90 percent of which are public and tuition-free. Some municipalities have established nine-year unified compulsory education schools which combine primary and lower secondary education. Students hoping to enroll in private junior high schools or national junior high schools affiliated with national universities are required to sit for admissions examinations administered by the institution.

All public junior high schools follow a standard national curriculum which comprises the compulsory subjects previously taught at the elementary level. In addition to compulsory subjects, students can also choose from a wide range of electives and extracurricular activities in fields such as fine arts, foreign languages, physical health and education, and music.

Lower secondary education is a critical stage in a typical student’s educational journey, as grades partially determine whether a student will be accepted into a good senior high school, and consequently, into a top university. It also culminates in the first significant stage of what is colloquially referred to as “ examination hell ,” a series of rigorous and highly consequential entrance examinations that are required for admission to senior high schools and universities. Many students in the final two years of junior high school attend Juku , or cram schools, in preparation for the competitive senior high school admissions examinations.

Students completing junior high school are awarded the Lower Secondary School Leaving Certificate and are eligible to sit for senior high school admissions examinations.

Yutori Kyōiku: Compulsory Education Reform

Since the 1990s, the direction that education reform in Japan should take has been a hotly debated topic. Experts have long criticized Japanese education for its “strict management” which “places excessive emphasis on standardization and student behavioral control.” They have also voiced concerns about the “the widespread practices of rote memorization and ‘cramming’ of knowledge,” which have been accused of “depriving pupils of opportunities to develop their intellectual curiosity and creativity.” Finally, experts allege that the “intense competition among students vying for admission to prestigious senior high schools and universities has caused tremendous psychological pressure for these students and their parents.”

To address these concerns, the government issued national curriculum standards in 2002 that put in place a concept known as yutori kyōiku, which roughly translates as “relaxed education.” The updated guidelines brought about significant changes, reducing the length of the school week from six to five days and cutting curriculum content by 30 percent. The guidelines also mandated the creation of a new “Integrated Studies” course, which granted schools and municipalities discretion to create their own courses to provide students with a “ learning space outside the traditional bounds of the curriculum that would not be closely associated with entrance tests or tightly defined learning outcomes.”

But a year after the new curriculum guidelines were introduced, yutori kyōiku policies faced intense criticism. The disappointing results of Japanese students in the OECD’s 2003 PISA study shocked the nation. In the study, the average performance of Japanese 15-year-olds dropped from first to sixth rank in mathematics and from eighth to 14 th in reading. In just three years, mean performance had dropped from 557 to 543 in mathematics, from 522 to 498 in reading literacy, and from 550 to 548 in science.

Experts also highlighted the results of the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), an assessment that measures U.S. eighth grade student performance comparatively with that of other secondary students around the globe, as a sign of the country’s declining educational quality. While Japanese students again performed well overall, outperforming the global average in mathematics, when compared with other high-performing Asian countries, Japan’s performance was disappointing. Between 31 percent and 44 percent of students from Singapore, South Korea, and Hong Kong scored at the advanced benchmark for math, compared with just 24 percent of Japanese students. Many Japanese scholars attributed the Japanese students’ relatively poor performance in these international education assessments to the more relaxed nature of the yutori kyōiku reforms.

Public concern over declining performance prompted the Japanese government to review the yutori kyōiku reforms. What followed were a number of reforms aimed at maintaining some of the benefits of the educational reforms of the 1990s and early 2000s while increasing the academic rigor of Japanese compulsory education. MEXT issued new curriculum standards in 2008 and 2009 which increased academic lesson hours while reducing Integrated Study and elective hours, and a number of municipalities, supported by MEXT, reintroduced Saturday classes. MEXT also introduced mandatory foreign language courses to the elementary school curriculum, as mentioned above. More recently, reform in Japan has avoided the yutori kyōiku concept, instead promoting “ Active Learning ” with the aim of developing “students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes compatible with the new visions of learning for a knowledge-based society in the twenty-first century.”

Upper Secondary Education

After nine years of compulsory education, students have the option of enrolling in senior high schools ( kōtō-gakkō ), widely regarded as the most strenuous stage of Japanese education. Despite being a non-compulsory level of education, the transition rate from junior to senior high school is extremely high, in part due to the integral role a student’s performance in senior high school plays in determining future access to higher education and employment. Per MEXT , as many as 98 percent of Japanese junior secondary students choose to move on to upper secondary schooling.

Admission to senior high school is typically determined by three criteria: an entrance examination, an interview, and junior high school grades. Of these criteria, the fate of a student’s placement in higher education—and even of their career in the years beyond—is determined most heavily by the entrance examination ( kōkō juken ). Students take these examinations, which are administered by their senior high school of choice, between January and March. Typically, entrance examinations test a student’s proficiency in the core subjects of Japanese, mathematics, science, social studies, and English.

Students hoping to enroll in public high schools take entrance examinations standardized by the prefectural board of education which has jurisdiction over the school. If students fail the entrance examination for a public school, they will often opt to apply to a private school. Unlike public schools, private senior high schools typically create their own examinations. Although nearly three-quarters of the country’s senior high schools are public, the proportion of private senior high schools has been growing in recent years. Students enrolling in the country’s limited number of unified junior high and senior high schools ( chuto-kyoiku-gakko ) are spared the entrance examination. Since reforms introduced in 2010 , students have been able to attend public high schools free of charge, while students attending private high schools receive government subsidies.

The employment prospects of students who fail to gain admission to either a public or private senior high school are often grim, with many forced to find work as unskilled blue-collar laborers, an occupational category traditionally thought of as low status. Given the highly competitive nature of senior high school admissions and coursework, it is no surprise that senior high school is perceived as a vehicle toward higher social status. This exclusivity, however, has long raised concerns about equity and access. Since the 1980s, MEXT has attempted to rectify these concerns through a series of reforms, the most significant of which was the introduction of the credit system to senior high schools . In the late 1980s, MEXT implemented the credit system for part-time and distance education learners, allowing them to learn at their own pace and graduate when they completed the required number of credits. In the early 1990s, the credit system was expanded to full-time senior high school students as well.

Senior high school lasts for three years, comprising grades 10 to 12, with students receiving 240 days of instruction each year. Following recent yutori kyōiku-inspired educational reforms, the school week is officially five days long, from Monday to Friday. Still, as mentioned above, workarounds exist, with educational authorities issuing special approvals to public schools to hold Saturday classes, while many less regulated private schools have reintroduced Saturday classes at monthly or bimonthly intervals.

As at the lower secondary level, the senior high school curriculum comprises three years of mathematics, social studies, Japanese, science, and English, with all the students in one grade level studying the same subjects. Electives are also similar to those offered at earlier levels, including physical education, music, art, and moral studies courses. However, the high number of required courses often leaves students with little room to fit in electives or subjects matching their personal interests. Although MEXT has pushed to expand the types of courses taken in high school to promote individuality, purpose, and inspiration, implementation has proved difficult because of a lack of qualified teachers.

Students must obtain a minimum of 74 credits to graduate. Students who graduate are awarded the Senior High School Graduation Certificate ( sotsugyo shomeisho ) and are eligible to sit for university entrance examinations.

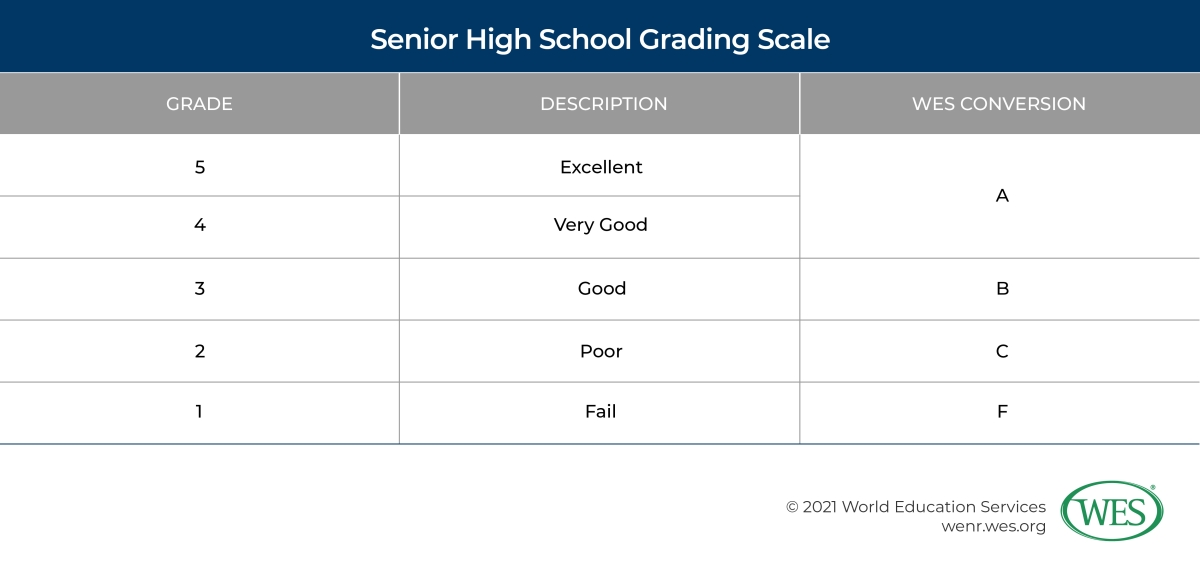

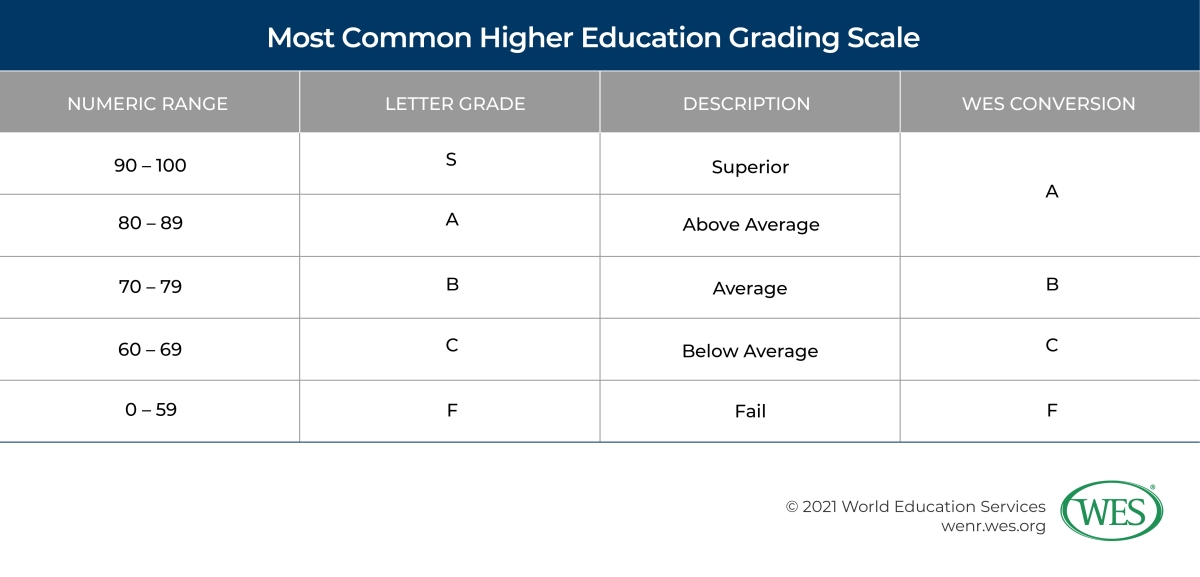

Senior high schools use a numeric grading scale ranging from 1 to 5.

Technical, Professional, and Vocational Education

Amid Japan’s current economic challenges, technical and vocational institutions have attracted considerable attention from reformers and government planners. Concerns that the education system is “ obsolete and dysfunctional , with the curricula lacking relevance to the realities of society and the economy,” has led to calls to expand and strengthen vocational and professional education. A 2017 MEXT white paper , which laid out key priorities in education reform, included a call to strengthen and reform the country’s technical and vocational education. To meet the challenges of globalization, economic transformation, and declining birthrates, the paper highlighted the importance of diversifying the country’s education system by increasing the availability of vocational schools and junior colleges. That paper followed a 2016 revision to the 1947 School Education Act; the revision urged professional institutions to collaborate with industry leaders to develop curricula that better balance practical and theoretical components.

Government planners are hoping that these efforts will expand and strengthen what is an already diverse landscape of vocational and professional institutions. Japan possesses a wide variety of institutions offering specialized education and professional and technical training to Japanese students at the secondary, post-secondary, and continuing education levels. Given the unique recruitment practices of Japanese employers—discussed further below—these institutions are attracting a growing number of university students who choose to study in a vocational institution either simultaneously or after graduating from university, to increase their employability, a phenomenon known in Japan as “double schooling.”

Specialized Training Colleges ( senshu gakku )

First introduced in 1976 , specialized training colleges ( senshu gakku ) offer courses of study aimed at developing skills and competencies that are needed for specific occupations. Three categories of specialized training colleges exist : general, upper secondary, and post-secondary, each maintaining different requirements for admission and offering training programs that vary in content and intensity.

Most specialized training colleges are privately owned and operated. New specialized training colleges must meet minimum quality requirements set by MEXT, after which they can be granted approval to operate by the prefectural government in which they are located.

Specialized Training College, General Course (senshu gakko ippan katei)

The lowest level of specialized training college offers courses in general vocational subjects such as Japanese dressmaking, art, and cooking. MEXT does not set admission requirements for entry to general courses, instead allowing individual institutions to set their own. As of 2017 , there were 157 colleges offering general courses to around 29,000 students.

Specialized Training College, Upper Secondary Course (koto-senshu-gakko)

More popular are the specialized training colleges offering courses at the upper secondary level. As of 2017, 424 institutions offered upper secondary courses to around 38,000 students. Admission to courses at this level requires possession of the Lower Secondary School Leaving Certificate. Courses typically last between one and three years. Those completing a course lasting three years or more that meets minimum academic requirements set by MEXT are eligible for enrollment in a university or a professional training college. Students graduating from these courses are awarded a Specialized Training College Upper Secondary Certificate of Graduation.

Professional Training College (senmon gakko)

The highest level of specialized training college is the professional training college, which offers courses at the post-secondary level. Admission is open to graduates of senior high schools, with courses lasting between one and four years. Students who graduate from specialized vocational schools are able to enroll in a traditional four-year university but can also use their degrees directly toward careers in their specialty. Options for specialization are vast but are typically classified into eight fields of study : industry, agriculture, medical care, health, education and social welfare, business practices, apparel and homemaking, and culture and the liberal arts.

Students completing a MEXT-approved course of at least two years and 62 credits (1,700 credit hours) are awarded a diploma (s enmonshi ). Those completing a MEXT-approved course of at least four years and 124 credits (3,400 credit hours) are awarded the advanced diploma ( kodo senmonshi ).