- Open access

- Published: 01 October 2013

Effective in-service training design and delivery: evidence from an integrative literature review

- Julia Bluestone 1 ,

- Peter Johnson 1 ,

- Judith Fullerton 2 ,

- Catherine Carr 1 ,

- Jessica Alderman 3 &

- James BonTempo 1

Human Resources for Health volume 11 , Article number: 51 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

69k Accesses

172 Citations

54 Altmetric

Metrics details

In-service training represents a significant financial investment for supporting continued competence of the health care workforce. An integrative review of the education and training literature was conducted to identify effective training approaches for health worker continuing professional education (CPE) and what evidence exists of outcomes derived from CPE.

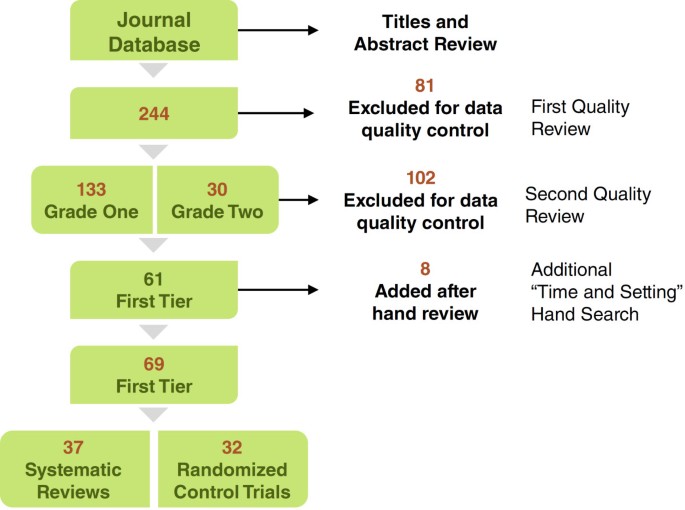

A literature review was conducted from multiple databases including PubMed, the Cochrane Library and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) between May and June 2011. The initial review of titles and abstracts produced 244 results. Articles selected for analysis after two quality reviews consisted of systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and programme evaluations published in peer-reviewed journals from 2000 to 2011 in the English language. The articles analysed included 37 systematic reviews and 32 RCTs. The research questions focused on the evidence supporting educational techniques, frequency, setting and media used to deliver instruction for continuing health professional education.

The evidence suggests the use of multiple techniques that allow for interaction and enable learners to process and apply information. Case-based learning, clinical simulations, practice and feedback are identified as effective educational techniques. Didactic techniques that involve passive instruction, such as reading or lecture, have been found to have little or no impact on learning outcomes. Repetitive interventions, rather than single interventions, were shown to be superior for learning outcomes. Settings similar to the workplace improved skill acquisition and performance. Computer-based learning can be equally or more effective than live instruction and more cost efficient if effective techniques are used. Effective techniques can lead to improvements in knowledge and skill outcomes and clinical practice behaviours, but there is less evidence directly linking CPE to improved clinical outcomes. Very limited quality data are available from low- to middle-income countries.

Conclusions

Educational techniques are critical to learning outcomes. Targeted, repetitive interventions can result in better learning outcomes. Setting should be selected to support relevant and realistic practice and increase efficiency. Media should be selected based on the potential to support effective educational techniques and efficiency of instruction. CPE can lead to improved learning outcomes if effective techniques are used. Limited data indicate that there may also be an effect on improving clinical practice behaviours. The research agenda calls for well-constructed evaluations of culturally appropriate combinations of technique, setting, frequency and media, developed for and tested among all levels of health workers in low- and middle-income countries.

Peer Review reports

The need to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of both pre-service education and continuing professional education (CPE) (in-service training) for the health workforce has never been greater. Decreasing global resources and a pervasive critical shortage of skilled health workers are paralleled by an explosion in the increase of and access to information. Universities and educational institutions are rapidly integrating different approaches for learning that move beyond the classroom [ 1 ]. The opportunities exist both in initial health professional education and CPE to expand education and training approaches beyond classroom-based settings.

An integrative review was designed to identify and review the evidence addressing best practices in the design and delivery of in-service training interventions. The use of an integrative review expands the variety of research designs that can be incorporated within a review’s inclusion criteria and allows the incorporation of both qualitative and quantitative information [ 2 ]. Five questions were formulated based on a conceptual model of CPE developed by the Johns Hopkins University Evidence-Based Practice Center (JHU EPC) for an earlier systematic review of continuing medical education (CME) [ 3 ]. We asked whether: 1. particular educational techniques, 2. frequency of instruction (single or repetitive), 3. setting where instruction occurs, or 4. media used to deliver the instruction make a difference in learning outcomes; and, 5. if there was any evidence regarding the desired outcomes, such as improvements in knowledge, skills or changes in clinical practice behaviours, which could be derived from CPE, using any mixture of technique, media or frequency.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Articles were included in this review if they addressed any type of health worker pre-service or CPE event, and included an analysis of the short-term evaluation and/or assessment of the longer-term outcomes of the training. We included only those articles published in English language literature. These criteria gave priority to articles that used higher-order research methods, specifically meta-analyses or systematic reviews and evaluations that employed experimental designs. Articles excluded from analysis were observational studies, qualitative studies, editorial commentary, letters and book chapters.

Search strategy

A research assistant searched the electronic, peer-reviewed literature between May and June 2011. The search was conducted on studies published in the English language from 2000 to 2011. Multiple databases including PubMed, the Cochrane Library and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) were utilized in the search. Medical subject headings (MeSH) and key search terms are presented below in Table 1 .

Study type, quality assessment and grade

An initial review of titles and abstracts produced 244 results. We identified the strongest studies available, using a range of criteria tailored to the review methodology. Initial selection criteria were developed by a panel of experts. Grading and inclusion criteria are presented in Table 2 . The grading criteria were adapted from the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEMB) levels of evidence model [ 4 ]. Grading of studies included within systematic reviews was reported by authors of those reviews and was not further assessed in this integrative review. Therefore, reference to quality of studies in our report refers to those a priori judgments. Only tier 1 articles (grades 1 and 2) were included in our analysis.

After prioritization of the articles, 163 tier 1 articles were assessed by a senior public health professional to determine topical relevance, study type and grade. A total of 61 tier 1 studies were selected to be included in the analysis following this second review. An additional hand search of the reference lists cited in published studies was conducted for topics that were underrepresented, specifically on the frequency and setting of educational activities. This search added eight articles for a total of 69 studies, including 37 systematic reviews and 32 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), see inclusion process for articles included in analysis, Figure 1 .

Inclusion process for articles included in the analysis.

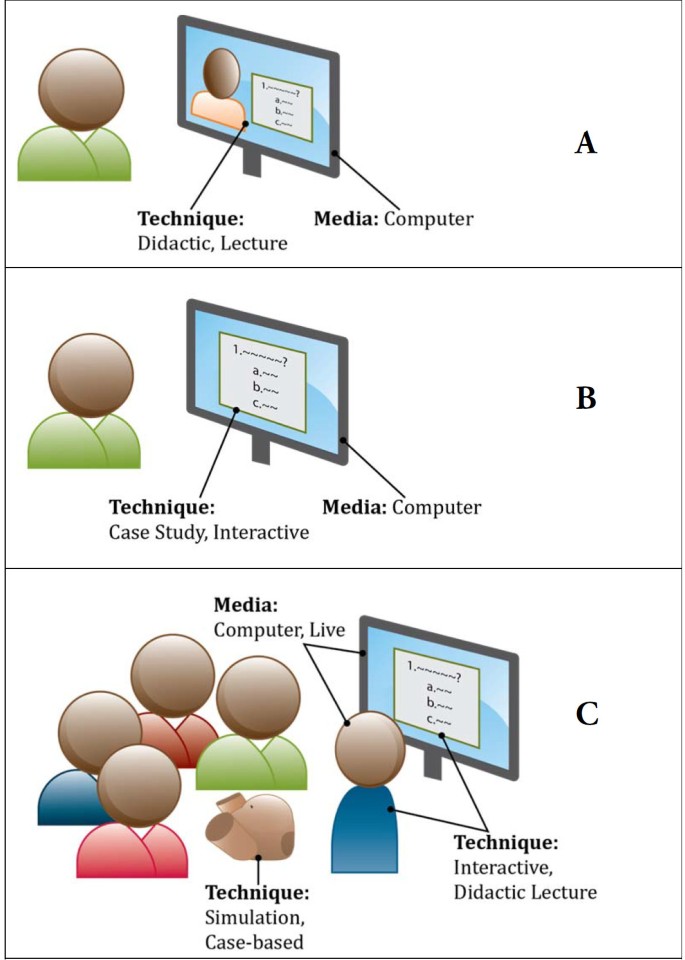

A data extraction spreadsheet was developed, following the model offered in the Best Evidence in Medical Education (BEME) group series [ 5 ] and the conceptual model and definition of terms offered by Marinopoulos et al. in the JHU EPC earlier review of CME [ 3 ]. Categorization decisions were necessary in cases when the use of terminology was inconsistent with the Marinopoulos et al. definitions of terms for CPE [ 3 ]. For example, an article that analysed 'distance learning’ as a technique and used the computer as the medium to deliver an interactive e-learning course was coded and categorized as an 'interactive’ technique delivered via 'computer’ as the medium of instruction. See illustration of categorization terminology in panels A, B, and C, Figure 2 , for an illustration of how terminology was used to categorize and organize articles for analysis.

Illustration of categorization terminology in panels a-c.

Selected articles that best represent common findings and outcomes (effects) of CPE are discussed in the results and discussion sections; the related tables present all the articles analysed and categorized for that topic, and each article is included only once. Relevant information obtained from educational psychology literature is referenced in the discussion.

The articles or studies that specifically addressed educational techniques are summarized in Table 3 . Technique refers to the educational methods used in the instruction. Technique descriptions are based on the Marinopoulos et al. definitions of terms [ 6 ] and reflect the approaches defined in the articles analysed.

Case-based: use of created or actual clinical cases that present materials and questions

Though case-based learning was not specifically compared with other techniques in the literature reviewed, it was often noted as a method in articles that discussed interactive techniques. Case-based learning was also noted as a technique used for computer-delivered CPE courses. Triola et al. compared types of media utilized for case-based learning and found positive learning outcomes both with the use of a live standardized patient and a computer-based virtual patient [ 7 ].

Didactic/lecture: presenting knowledge content; facilitator determines content, organization and pace

Lecture was often referred to in the literature as traditional instruction, lecture-based or didactic teaching. Didactic instruction was not found to be an effective educational technique compared with other methods. Two studies [ 8 , 9 ] found no statistical difference in learning outcomes, and three studies found didactic to be less effective than other techniques [ 10 – 12 ]. Reynolds et al. compared didactic instruction with simulation. The study was limited by small sample size (n = 50), but still demonstrated that the simulation group had a significantly higher mean post-test score ( P <0.01) and overall higher learner satisfaction [ 12 ].

Several systemic reviews that compared didactic instruction to a wide variety of teaching approaches also identified didactic instruction as a less effective educational technique [ 13 – 15 ].

Feedback: providing information to the learner about performance

Multiple articles identified feedback as important for outcomes [ 16 – 18 ]. Herbert et al. compared individualized feedback in the form of a graphic (a prescribing portrait based on personal history of drug-prescribing practices) to small group discussion of the same material and found that both the feedback and the live, interactive session were somewhat effective at changing physician’s prescribing behaviours [ 16 ]. The Issenberg et al. systematic review of simulation identified practice and feedback as key for effective skill development [ 17 ]. A Cochrane review of the evidence to support CPE suggested the importance of feedback and instructor interaction in improving learning outcomes [ 18 ].

Games: competitive game with preset rules

The use of games as an instructional technology was addressed in one rigorous systematic review. The authors found only a limited number of studies, which were of low to moderate methodological quality and offered inconsistent results. Three of the five RCTs included in the review suggested that educational games could have a positive effect on increasing medical student knowledge and that they include interaction and allow for feedback [ 19 ].

Interactive: provide for interaction between the learner and facilitator

Five articles specifically compared interactive CPE to other educational techniques. De Lorenzo and Abbot found interactive techniques to be moderately superior for knowledge outcomes than didactic lecture [ 10 ]. Two other studies found interactive techniques were more effective when feedback from chart audits was added to the intervention [ 16 , 20 ].

Three systematic reviews and one meta-analysis specifically noted the importance of learner interactivity or engagement in learning in achieving positive learning outcomes [ 21 – 24 ] (refer to summary of articles focused on outcomes).

Point-of-care (POC): information provided as needed, at the point of clinical care

Two articles and one systematic review specifically addressed point-of-care (POC) as a technique. The systematic review included three studies and concluded that while the findings were weak, they did indicate that POC led to improved knowledge and confidence [ 25 ]. In an examination of media, Leung et al. determined that handheld devices were more effective than print-based, POC support, although outcome measures were self-reported behaviours [ 26 ]. You et al. found improved performance on a procedure among surgical residents who received POC mentoring via a video using a mobile device, compared with those who received only didactic instruction [ 27 ].

Problem-based learning (PBL): present a case, assign information-seeking tasks and answer questions about the case; can be facilitated or non-facilitated

Four articles specifically compared problem-based learning (PBL) to other methods. One study identified PBL as slightly better [ 11 ], and two studies indicated it to be relatively equal to didactic instruction [ 8 , 9 ]. A systematic review of 10 studies on PBL reported inconclusive evidence to support the approach, although several studies reported increased critical thinking skills and confidence in making decisions [ 28 ].

Reminders: provision of reminders

The Zurovac et al. study conducted in Kenya found that using mobile devices for repetitive reminders resulted in significant improvement in health care provider’s case management of paediatric malaria, and these gains were retained over a 6-month period [ 29 ]. Intention-to-treat analysis showed that correct management improved by 23.7% (95% confidence interval (CI) 7.6 to 40.0, P <0.01) immediately after intervention and by 24.5% (95% CI 8.1 to 41.0, P <0.01) 6 months later, compared with the control group [ 29 ]. Reminders were also noted as an effective technique by two of the systematic reviews [ 13 , 14 ].

Self-directed: completed independently by the learner based on learning needs

This term was difficult to extract for analysis due to widely varying terminology. Some authors used the term 'distance learning’, and some used it to define the medium of delivery, rather than technique. This analysis specifically discusses articles that were consistent with the description for self-directed learning, even if the authors used different terminology.

A recent systematic review identified that moderate-quality evidence suggests a slight increase in knowledge domain compared with traditional teaching, but notes that this may be due to the increased exposure to content [ 30 ]. One RCT found modest improvements in knowledge using a self-directed approach, but noted it was less effective at impacting attitudes or readiness to change [ 31 ].

Multiple studies focused on use of the computer as the medium to deliver instruction and noted that self-directed instruction was equally (or more) effective as instructor-led didactic or interactive instruction and potentially more efficient.

Simulation may include models, devices, standardized patients, virtual environments, social or clinical situations that simulate problems, events or conditions experienced in professional encounters [ 17 ]. Simulation was noted as an effective technique for promotion of learning outcomes across the systematic reviews, particularly for the development of psychomotor and clinical decision-making skills. The systematic reviews all highlighted inconclusive and weak methodology in the studies reviewed, but noted sufficient evidence existed to support simulation as useful for psychomotor and communication skill development [ 32 – 34 ] and to facilitate learning [ 35 ]. The systematic review by Lamb suggests that patient simulators, whether computer or anatomic models, are one of the more effective forms of simulations [ 36 ].

Outcomes of the four separate RCTs indicated simulation was better than the techniques to which they were compared, including interactive [ 37 , 38 ], didactic [ 12 ] and problem-based approaches [ 35 ]. A study by Daniels et al. found that although knowledge outcomes were similar between the interactive and simulation groups, the simulation team performance in a labour and delivery clinical drill was significantly higher for both shoulder dystocia (11.75 versus 6.88, P <0.01) and eclampsia (13.25 versus 11.38, P = 0.032) at 1 month post-intervention [ 38 ].

Simulation was also found to be useful for identifying additional learning gaps, such as a drill on the task of mixing magnesium sulfate for administration [ 39 ]. A systematic review focused on resuscitation training identified simulation as an effective technique, regardless of media or setting used to deliver it [ 40 ].

Team-based: providing interventions for teams that provide care together

Articles discussed here focused on the technique of providing training to co-workers engaged as learning teams. One systematic review of eight studies found that there is limited and inconclusive evidence to support team-based training [ 41 ]. Two of the articles reporting on the same CPE study did not identify any improvements in performance or knowledge acquisition with the addition of using a team-based approach [ 39 , 42 ].

This review included consideration of frequency, comparing single versus repetitive exposure. The findings regarding frequency are summarized in Table 4 .

The three articles focused on frequency all support the use of repetitive interventions. These studies evaluated repetition using the Spaced Education platform (now called Qstream), an Internet-based medium that uses repeated questions and targeted feedback. The evidence from these three articles demonstrated that repetitive, time-spaced education exposures resulted in better knowledge outcomes, better retention and better clinical decisions compared with single interventions and live instruction [ 43 – 45 ].

The use of repetitive or multiple exposures is supported in other systematic reviews of the literature, as well as one RCT conducted in Kenya that used repeated text reminders and resulted in a significant improvement in adherence to malaria treatment protocols [ 29 ].

Setting is the physical location within which the instruction occurs. We identified three articles that looked specifically at the training setting. The findings regarding setting are summarized in Table 5 . Two of them stemmed from the same intervention. Crofts et al. specifically addressed the impact of setting and technique (team-based training) on knowledge acquisition and found no significant difference in the post-score based on the setting [ 42 ]. A systematic review of eight articles evaluating the effectiveness of team-based training for obstetric care did not find significant differences in learning outcomes between a simulation centre and a clinical setting [ 41 ].

Coomarasamy and Khan conducted a systematic review and compared classroom or stand-alone versus clinically integrated teaching for evidence-based medicine (EBM). Their review identified that classroom teaching improved knowledge, but not skills, attitudes or behaviour outcomes; whereas clinically integrated teaching improved all outcomes [ 46 ]. This finding was supported by the Hamilton systematic review of CPE, which suggests that teaching in a clinical setting or simulation setting is more effective (Table 1 ), as well as the Raza et al. systematic review of 23 studies to evaluate stand-alone versus clinically integrated teaching. This review suggested that clinically integrated teaching improved skills, attitudes and behaviour, not just knowledge [ 18 ].

Media refers to the means used to deliver the curriculum. The majority of RCTs compared self-paced or individual instruction delivered via computer versus live, group-based instruction. The findings regarding media are summarized in Table 6 .

Live versus computer-based

Live instruction was found to be somewhat effective at improving knowledge, but less so for changing clinical practice behaviours. When comparing live to computer-based instruction, a frequent finding was that computer-based instruction led to either equal or slightly better knowledge performance on post-tests than live instruction. One of the few to identify a significant difference in outcomes, Harrington and Walker found the computer-based group outperformed the instructor-led group on the knowledge post-test and that participants in the computer-based group, on average, spent less time completing the training than participants in the instructor-led group [ 47 ].

Systematic reviews indicate that the evidence supports the use of computer-delivered instruction for knowledge and attitudes; however, insufficient evidence exists to support its use in the attempt to change practice behaviours. The Raza Cochrane systematic review identified 16 randomized trials that evaluated the effectiveness of Internet-based education used to deliver CPE to practicing health care professionals. Six studies showed a positive change in participants’ knowledge, and three studies showed a change in practice in comparison with traditional formats [ 18 ]. One systematic review noted the importance of interactivity, independent of media, in achieving an impact on clinical practice behaviours [ 48 ].

One article assessed the use of animations against audio instructions in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) using a mobile phone and found the group that had audiovisual animations performed better than the group that received live instruction over the phone in performing CPR; however, neither group was able to perform the psychomotor skill correctly [ 49 ]. Leung et al. found providing POC decision support via a mobile device resulted in slightly better self-reporting on outcome measures compared with print-based job aids, but that both the print and mobile groups showed improvements in use of evidence-based decision-making [ 26 ].

The systematic review of print-based materials conducted by Farmer et al. did not find sufficient evidence to support the use of print media to change clinical practice behaviours [ 50 ]. A comparison of the use of print-based guidelines to a live, interactive workshop indicated that those who completed live instruction were slightly better able to identify patients at high risk of an asthma attack. However, neither intervention resulted in changed practice behaviours related to treatment plans [ 51 ].

Multiple systematic reviews caution against the use of print only media, concluding that live instruction is preferable to print only. Another consistent theme was support for the use of multimedia in CPE interventions.

Outcomes are the consequences of a training intervention. This literature review focuses on changes in knowledge, attitudes, psychomotor, clinical decision-making or communication skills, and effects on practice behaviours and clinical outcomes. All of the articles that focused on outcomes were systematic reviews of the literature and are summarized in Table 7 .

The weight of the evidence across several studies indicated that CPE could effectively address knowledge outcomes, although several studies used weaker methodological approaches. Specifically, computer-based instruction was found to be equally or more effective than live instruction for addressing knowledge, while multiple repetitive exposures leads to better knowledge gains than a single exposure. Games can also contribute to knowledge if designed as interactive learning experiences that stimulate higher thinking through analysis, synthesis or evaluation.

No studies or systematic reviews looked only at attitudes, but CPE that includes clinical integration, simulations and feedback may help address attitudes. The JHU EPC group systematic review evaluation of the short- and long-term effects of CPE on physician attitudes reviewed 26 studies and, despite the heterogeneity of the studies, identified trends supporting the use of multimedia and multiple exposures for addressing attitudes [ 6 ].

Several systematic reviews looked specifically at skills, concluding that there is weak but sufficient evidence to suggest that psychomotor skills can be addressed with CPE interventions that include simulations, practice with feedback and/or clinical integration. 'Dose-response’ or providing sufficient practice and feedback was identified as important for skill-related outcomes. Other RCTs suggest clinically integrated education for supporting skill development. Choa et al. found that neither the audio mentoring via mobile nor animated graphics via mobile resulted in the desired psychomotor skills, reinforcing the need for practice and feedback for psychomotor skill development identified in other studies [ 49 ].

Two systematic reviews focused on communication skills and found techniques that include behaviour modeling, practice and feedback, longer duration or more practice opportunities were more effective [ 52 , 53 ]. Evidence suggests that development of communication skills requires interactive techniques that include practice-oriented strategies and feedback, and limit lecture and print-based materials to supportive strategies only.

Findings also suggest that simulation, PBL, multiple exposures and clinically integrated CPE can improve critical thinking skills. Mobile-based POC support was found to be more useful in the development of critical thinking than print-based job aids.

Several systematic reviews specifically looked at CPE, practice behaviours and the behaviours of the provider. These studies found, despite reportedly weak evidence, that interactive techniques that involved feedback, interaction with the educator, longer durations, multiple exposures, multimedia, multiple techniques and reminders may influence practice behaviours.

A targeted review of 37 articles from the JHU EPC review on the impact of CPE on clinical practice outcomes drew no firm conclusions, but multiple exposures, multimedia and multiple techniques were recommended to improve potential outcomes [ 6 ]. Interaction and feedback were found to be more useful than print or educational meetings (systematic review of nine articles) [ 24 ], but print-based unsolicited materials were not found to be effective [ 50 ]. The systematic review of live, classroom-based, multi-professional training conducted by Rabal et al. found 'the impact on clinical outcomes is limited’ [ 54 ].

The heterogeneity of study designs included in this review limits the interpretations that can be drawn. However, there is remarkable similarity between the information from studies included in this review and similar discussions published in the educational psychology literature. We believe that there is sufficient evidence to support efforts to implement and evaluate the combinations of training techniques, frequency, settings and media included in this discussion.

Avoid educational techniques that provide a passive transfer of information, such as lecture and reading, and select techniques that engage the learner in mental processing, for example, case studies, simulation and other interactive strategies. This recommendation is reinforced in educational psychology literature [ 55 ]. There is sufficient evidence to endorse the use of simulation as a preferred educational technique, notably for psychomotor, communication or critical thinking skills. Given the lack of evidence for didactic methods, selecting interactive, effective educational techniques remains the critical point to consider when designing CPE interventions.

Self-directed learning was also found to be an effective strategy, but requires the use of interactive techniques that engage the learner. Self-directed learning has the additional advantage of allowing learners to study at their own pace, select times convenient for them and tailor learning to their specific needs.

Limited evidence was found to support team-based learning or the provision of training in work teams. There is a need for further study in this area, given the value of engaging teams that are in the same place at the same time in an in-service training intervention. This finding is especially relevant for emergency skills that require the collaboration and cooperation of a team.

Repetitive exposure is supported in the literature. When possible, replace single-event frequency with targeted, repetitive training that provides reinforcement of important messages, opportunities to practice skills and mechanisms for fostering interaction. Recommendations drawn from the educational psychology literature that address the issue of cognitive overload [ 56 ] suggest targeting information to essentials and repetition.

Select the setting based on its ability to deliver effective educational techniques, be similar to the work environment and allow for practice and feedback. In this time of crisis, workplace learning that reduces absenteeism and supports individualized learning is critical. Conclusions from literature in educational psychology reinforce the importance of 'situating’ learning to make the experience as similar to the workplace as possible [ 57 ].

Certain common themes emerged from the many articles that commented on the role of media in CPE effectiveness. A number of systematic reviews suggest the use of multimedia in CPE. It is important to note that the studies that found similar knowledge outcomes between computer-based and live instruction stated that both utilized interactive techniques, possibly indicating the effectiveness was due to the technique rather than the media through which it was delivered. While the data on use of mobile technology to deliver CPE were limited, the study by Zurovac et al. indicated the potential power of mobile technology to improve provider adherence to clinical protocols [ 29 ]. Currently, there is unprecedented access to basic mobile technology and increasing access to lower-cost tablets and computers. The use of these devices to deliver effective techniques warrants exploration and evaluation, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

CPE can positively impact desired learning outcomes if effective techniques are used. There are, however, very limited and weak data that directly link CPE to improved clinical practice outcomes. There are also limited data that link CPE to improved clinical practice behaviours, which may influence the strength of the linkage to outcomes.

Limitations

The following limitations apply to the methodology that we selected for this study. An integrative review of the literature was selected because the majority of published studies of education and training in low- and middle-resource countries did not meet the parameters required of a more rigorous systematic review or meta-analysis. The major limitation of integrative reviews is the potential for bias from their inclusion of non-peer-reviewed information or lower-quality studies. The inclusion of articles representing a range of rigor in their research design restricts the degree of confidence that can be placed on interpretations drawn by the authors of those articles, with the exception of original articles that explicitly discussed quality (such as systematic reviews). This review did not make an additional attempt to reanalyse or combine primary data.

Therefore, for purpose of this article, we also graded all articles and included only tier 1 articles in the analysis. This resulted in restriction of information on certain topics for this report, although a wider range of information is available.

We faced an additional limitation in that many articles included in the review were neither fully transparent nor consistent with terminology definitions used in other reports. This is due in part to the fact that we went beyond the bio-medical literature, to include studies conducted in the education and educational psychology literature, as was appropriate to the integrative review methodology. Certain topics were underdeveloped in the literature, which limits the interpretation that can be drawn on these topics. Other topics are addressed in studies conducted using lower-tier research methodologies (for example observational and/or qualitative studies) that were not included in this article. In addition, the overwhelming majority of studies focused on health professionals in developed or middle-income countries. There were very few articles of sufficient rigor conducted in low- and middle-income countries. This limits what we can say regarding the application of these findings among health workers of a lower educational level and in lower-resourced communities.

In-service training has been and will remain a significant investment in developing and maintaining essential competencies required for optimal public health in all global service settings. Regrettably, in spite of major investments, we have limited evidence about the effectiveness of the techniques commonly applied across countries, regardless of level of resource.

Nevertheless, all in-service training, wherever delivered, must be evidence-based. As stated in Bloom’s systematic review, 'Didactic techniques and providing printed materials alone clustered in the range of no to low effects, whereas all interactive programmes exhibited mostly moderate to high beneficial effect. … The most commonly used techniques, thus, generally were found to have the least benefit’ [ 14 ]. The profusion of mobile technology and increased access to technology present an opportunity to deliver in-service training in many new ways. Given current gaps in high-quality evidence from low- and middle-income countries, the future educational research agenda must include well-constructed evaluations of effective, cost-effective and culturally appropriate combinations of technique, setting, frequency and media, developed for and tested among all levels of health workers in low- and middle-income countries.

Abbreviations

Best Evidence in Medical Education

Confidence interval

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- Continuing medical education

- Continuing professional education

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Evidence-based medicine

Johns Hopkins University Evidence-Based Practice Center

Medical subject headings

Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine

Problem-based learning

Point-of-care

Randomized controlled trial.

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, Fineberg H, Garcia P, Ke Y, Kelley P, Kistnasamy B, Meleis A, Naylor D, Pablos-Mendez A, Reddy S, Scrimshaw S, Sepulveda J, Serwadda D, Zurayk H: Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010, 376 (9756): 1923-1958. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5.

PubMed Google Scholar

Wittemore R, Kanfl K: The integrative review: updated methodology. In J Adv Nursing. 2005, 52 (5): 546-553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x.

Google Scholar

Marinopoulos SS, Baumann MH: American College of Chest Physicians Health and Science Policy Committee: Methods and definition of terms: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines. Chest. 2009, 135 (3 Suppl): 17S-28S.

Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) Levels of Evidence Working Group: The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence. 2011, Oxford: Centre for Evidence Based Medicine, http://www.cebm.net/?O=1025 ,

Best Evidence in Medical Education (BEME): Appendix 1-BEME Coding Sheet. 2011, http://www.medicalteacher.org/MEDTEACH_wip/supp%20files/BEME%204%20Figs%20%20Appendices/BEME4_Appx1.pdf ,

Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, Wilson LM, Ashar BH, Magaziner JL, Miller RG, Thomas PA, Prokopowicz GP, Qayyum R, Bass EB: Effectiveness of continuing medical education. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, No. 149, (Prepared by the Johns Hopkins Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No.290-02-0018) AHRQ Publication No. -7-E006. January 2007, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD

Triola M, Feldman H, Kalet AL, Zabar S, Kachur EK, Gillespie C, Anderson M, Griesser C, Lipkin M: A randomized trial of teaching clinical skills using virtual and live standardized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006, 21 (5): 424-429. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00421.x.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Smits PB, De Buisonje CD, Verbeek JH, Van Dijk FJ, Metz JC, Ten Cate OJ: Problem-based learning versus lecture-based learning in postgraduate medical education. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003, 29 (4): 280-287. 10.5271/sjweh.732.

White M, Michaud G, Pachev G, Lirenman D, Kolenc A, FitzGerald JM: Randomized trial of problem-based versus didactic seminars for disseminating evidence-based guidelines on asthma management to primary care physicians. J ContinEduc Health Prof. 2004, 24 (4): 237-243. 10.1002/chp.1340240407.

De Lorenzo RA, Abbott CA: Effectiveness of an adult-learning, self-directed model compared with traditional lecture-based teaching methods in out-of-hospital training. Acad Emerg Med. 2004, 11 (1): 33-37.

Lin CF, Lu MS, Chung CC, Yang CM: A comparison of problem-based learning and conventional teaching in nursing ethics education. Nurs Ethics. 2010, 17 (3): 373-382. 10.1177/0969733009355380.

Reynolds A, Ayres-de-Campos D, Pereira-Cavaleiro A, Ferreira-Bastos L: Simulation for teaching normal delivery and shoulder dystocia to midwives in training. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2010, 23 (3): 405-

CAS Google Scholar

Alvarez MP, Agra Y: Systematic review of educational interventions in palliative care for primary care physicians. Palliat Med. 2006, 20 (7): 673-683. 10.1177/0269216306071794.

Bloom BS: Effects of continuing medical education on improving physician clinical care and patient health: a review of systematic reviews. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005, 21 (3): 380-385.

Satterlee WG, Eggers RG, Grimes DA: Effective medical education: insights from the Cochrane Library. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008, 63 (5): 329-333. 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31816ff661.

Herbert CP, Wright JM, Maclure M, Wakefield J, Dormuth C, Brett-MacLean P, Legare J, Premi J: Better Prescribing Project: a randomized controlled trial of the impact of case-based educational modules and personal prescribing feedback on prescribing for hypertension in primary care. Fam Pract. 2004, 21 (5): 575-581. 10.1093/fampra/cmh515.

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ: Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005, 27 (1): 10-28. 10.1080/01421590500046924.

Raza A, Coomarasamy A, Khan KS: Best evidence continuous medical education. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009, 280 (4): 683-687. 10.1007/s00404-009-1128-7.

Akl EA, Pretorius RW, Sackett K, Erdley WS, Bhoopathi PS, Alfarah Z, Schunemann HJ: The effect of educational games on medical students’ learning outcomes: a systematic review: BEME Guide No 14. Med Teach. 2010, 32 (1): 16-27. 10.3109/01421590903473969.

Laprise R, Thivierge R, Gosselin G, Bujas-Bobanovic M, Vandal S, Paquette D, Luneau M, Julien P, Goulet S, Desaulniers J, Maltais P: Improved cardiovascular prevention using best CME practices: a randomized trial. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009, 29 (1): 16-31. 10.1002/chp.20002.

Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O’Brien MA, Wolf F, Davis D, Odgaard-Jensen J, Oxman AD: Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, 2: CD003030-

Mansouri M, Lockyer J: A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007, 27 (1): 6-15. 10.1002/chp.88.

Perry M, Draskovic I, Lucassen P, Vernooij-Dassen M, Van Achterberg T, Rikkert MO: Effects of educational interventions on primary dementia care: A systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2011, 26 (1): 1-11. 10.1002/gps.2479.

Rampatige R, Dunt D, Doyle C, Day S, Van Dort P: The effect of continuing professional education on health care outcomes: lessons for dementia care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009, 21 (Suppl 1): S34-S43.

Blaya JA, Fraser HS, Holt B: E-health technologies show promise in developing countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010, 29 (2): 244-251. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0894.

Leung GM, Johnston JM, Tin KY, Wong IO, Ho LM, Lam WW, Lam TH: Randomised controlled trial of clinical decision support tools to improve learning of evidence-based medicine in medical students. BMJ. 2003, 327 (7423): 1,090-

You JS, Park S, Chung SP, Park JW: Usefulness of a mobile phone with video telephony in identifying the correct landmark for performing needle thoracocentesis. Emerg Med J. 2009, 26 (3): 177-179. 10.1136/emj.2008.060541.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Yuan H, Williams BA, Fan L: A systematic review of selected evidence on developing nursing students’ critical thinking through problem-based learning. Nurse Educ Today. 2008, 28 (6): 657-663. 10.1016/j.nedt.2007.12.006.

Zurovac D, Sudoi RK, Akhwale WS, Ndiritu M, Hamer DH, Rowe AK, Snow RW: The effect of mobile phone text-message reminders on Kenyan health workers’ adherence to malaria treatment guidelines: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2011, 378 (9793): 795-803. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60783-6.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Varkey P, Prokop LJ, Murad AL: The effectiveness of self-directed learning in health professions education: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2010, 44 (11): 1,057-1,068.

Young JM, Ward J: Can distance learning improve smoking cessation advice in family practice? A randomized trial. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002, 22 (2): 84-93. 10.1002/chp.1340220204.

Harder BN: Use of simulation in teaching and learning in health sciences: a systematic review. J Nurs Educ. 2010, 49 (1): 23-28. 10.3928/01484834-20090828-08.

McGaghie WC, Siddall VJ, Mazmanian PE, Myers J: American College of Chest Physicians Health and Science Policy Committee: Lessons for continuing medical education from simulation research in undergraduate and graduate medical education: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines. Chest. 2009, 135 (3 Suppl): 62S-68S.

Sturm LP, Windsor JA, Cosman PH, Cregan P, Hewett PJ, Maddern GJ: A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training. Ann Surg. 2008, 248 (2): 166-179. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176bf24.

Steadman RH, Coates WC, Huang YM, Matevosian R, Larmon BR, McCullough L, Ariel D: Simulation-based training is superior to problem-based learning for the acquisition of critical assessment and management skills. Crit Care Med. 2006, 34 (1): 151-157. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000190619.42013.94.

Lamb D: Could simulated emergency procedures practised in a static environment improve the clinical performance of a Critical Care Air Support Team (CCAST)? A literature review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2007, 23 (1): 33-42. 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.07.002.

Bruppacher HR, Alam SK, LeBlanc VR, Latter D, Naik VN, Savoldelli GL, Mazer CD, Kurrek MM, Joo HS: Simulation-based training improves physicians’ performance in patient care in high-stakes clinical setting of cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2010, 112 (4): 985-992. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d3e31c.

Daniels K, Arafeh J, Clark A, Waller S, Druzin M, Chueh J: Prospective randomized trial of simulation versus didactic teaching for obstetrical emergencies. Simul Healthc. 2010, 5 (1): 40-45. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181b65f22.

Ellis D, Crofts JF, Hunt LP, Read M, Fox R, James M: Hospital, simulation center, and teamwork training for eclampsia management: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008, 111 (3): 723-731. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181637a82.

Hamilton R: Nurse’s knowledge and skill retention following cardiopulmonary resuscitation training: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2005, 51 (3): 288-297. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03491.x.

Merien AE, Van de Ven J, Mol BW, Houterman S, Oei SG: Multidisciplinary team training in a simulation setting for acute obstetric emergencies: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2010, 115 (5): 1,021-1,031.

Crofts JF, Ellis D, Draycott TJ, Winter C, Hunt LP, Akande VA: Change in knowledge of midwives and obstetricians following obstetric emergency training: a randomised controlled trial of local hospital, simulation centre and teamwork training. BJOG. 2007, 114 (12): 1,534-1,541.

Kerfoot BP, Fu Y, Baker H, Connelly D, Ritchey ML, Genega EM: Online spaced education generates transfer and improves long-term retention of diagnostic skills: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2010, 211 (3): 331-337. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.023.

Kerfoot BP, Kearney MC, Connelly D, Ritchey ML: Interactive spaced education to assess and improve knowledge of clinical practice guidelines: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2009, 249 (5): 744-749. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819f6db8.

Kerfoot BP, Baker HE, Koch MO, Connelly D, Joseph DB, Ritchey ML: Randomized, controlled trial of spaced education to urology residents in the United States and Canada. J Urol. 2007, 177 (4): 1,481-1,487.

Coomarasamy A, Khan KS: What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in evidence based medicine changes anything? A systematic review. BMJ. 2004, 329 (7473): 1,017-

Harrington SS, Walker BL: The effects of computer-based training on immediate and residual learning of nursing facility staff. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2004, 35 (4): 154-163. quiz 186–7

Curran VR, Fleet L: A review of evaluation outcomes of web-based continuing medical education. Med Educ. 2005, 39 (6): 561-567. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02173.x.

Choa M, Park I, Chung HS, Yoo SK, Shim H, Kim S: The effectiveness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation instruction: animation versus dispatcher through a cellular phone. Resuscitation. 2008, 77 (1): 87-94. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.10.023.

Farmer AP, Legare F, Turcot L, Grimshaw J, Harvey E, McGowan JL, Wolf F: Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, 3: CD004398-

Liaw ST, Sulaiman ND, Barton CA, Chondros P, Harris CA, Sawyer S, Dharmage SC: An interactive workshop plus locally adapted guidelines can improve general practitioners asthma management and knowledge: a cluster randomised trial in the Australian setting. BMC Fam Pract. 2008, 9: 22-10.1186/1471-2296-9-22.

Gysels M, Richardson A, Higginson IJ: Communication training for health professionals who care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of training methods. Support Care Canc. 2005, 13 (6): 356-366. 10.1007/s00520-004-0732-0.

Berkhof M, Van Rijssen HJ, Schellart AJ, Anema JR, Van der Beek AJ: Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2011, 84 (2): 152-162. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.010.

Rabol LI, Ostergaard D, Mogensen T: Outcomes of classroom-based team training interventions for multiprofessional hospital staff: A systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010, 19 (6): e27-10.1136/qshc.2009.037184.

Woolfolk AE: Educational Psychology. 2009, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill/Prentice Hall, 11

Mayer RE: Applying the science of learning to medical education. Med Educ. 2010, 44 (6): 543-549. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03624.x.

Gott S, Lesgold A: Competence in the workplace: how cognitive performance models and situated instruction can accelerate skill acquisition. Advances in Instructional Psychology, Volume 4. Edited by: Glaser R. 2000, Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank the Jhpiego Corporation for support for this research. We thank Dana Lewison, Alisha Horowitz, Rachel Rivas D’Agostino and Trudy Conley for their support in editing and formatting the manuscript. We also thank Spyridon S Marinopoulos, MD, MBA, from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, for his initial input into the study and links to relevant resources. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Jhpiego Corporation.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Jhpiego Corporation, 1615 Thames Street, Baltimore, MD, 21231, USA

Julia Bluestone, Peter Johnson, Catherine Carr & James BonTempo

Independent Consultant, San Diego, CA, USA

Judith Fullerton

Research Assistant, Baltimore, MD, USA

Jessica Alderman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Julia Bluestone .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JB performed article reviews for inclusion, synthesized data and served as primary author of the analysis and manuscript. PJ conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and provided significant input into the manuscript. JF provided guidance on the literature review process, grading and categorizing criteria, and quality review of selected articles, and participated actively as an author of the manuscript. CC and JBT contributed to writing of the manuscript. JA searched the literature, performed initial review and coding, and contributed to selected sections of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Julia Bluestone, Peter Johnson, Catherine Carr contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2, authors’ original file for figure 3, rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bluestone, J., Johnson, P., Fullerton, J. et al. Effective in-service training design and delivery: evidence from an integrative literature review. Hum Resour Health 11 , 51 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-51

Download citation

Received : 08 August 2012

Accepted : 02 May 2013

Published : 01 October 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-51

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- In-service training

- Continuing professional development

Human Resources for Health

ISSN: 1478-4491

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 60, 2009, review article, benefits of training and development for individuals and teams, organizations, and society.

- Herman Aguinis 1 , and Kurt Kraiger 2

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 The Business School, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado 80217-3364; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523-1876; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 60:451-474 (Volume publication date January 2009) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163505

- © Annual Reviews

This article provides a review of the training and development literature since the year 2000. We review the literature focusing on the benefits of training and development for individuals and teams, organizations, and society. We adopt a multidisciplinary, multilevel, and global perspective to demonstrate that training and development activities in work organizations can produce important benefits for each of these stakeholders. We also review the literature on needs assessment and pretraining states, training design and delivery, training evaluation, and transfer of training to identify the conditions under which the benefits of training and development are maximized. Finally, we identify research gaps and offer directions for future research.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

Publication Date: 10 Jan 2009

Online Option

Sign in to access your institutional or personal subscription or get immediate access to your online copy - available in PDF and ePub formats

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Effective in-service training design and delivery: evidence from an integrative literature review

Affiliation.

- 1 Jhpiego Corporation, 1615 Thames Street, Baltimore, MD 21231, USA. [email protected].

- PMID: 24083659

- PMCID: PMC3850724

- DOI: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-51

Background: In-service training represents a significant financial investment for supporting continued competence of the health care workforce. An integrative review of the education and training literature was conducted to identify effective training approaches for health worker continuing professional education (CPE) and what evidence exists of outcomes derived from CPE.

Methods: A literature review was conducted from multiple databases including PubMed, the Cochrane Library and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) between May and June 2011. The initial review of titles and abstracts produced 244 results. Articles selected for analysis after two quality reviews consisted of systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and programme evaluations published in peer-reviewed journals from 2000 to 2011 in the English language. The articles analysed included 37 systematic reviews and 32 RCTs. The research questions focused on the evidence supporting educational techniques, frequency, setting and media used to deliver instruction for continuing health professional education.

Results: The evidence suggests the use of multiple techniques that allow for interaction and enable learners to process and apply information. Case-based learning, clinical simulations, practice and feedback are identified as effective educational techniques. Didactic techniques that involve passive instruction, such as reading or lecture, have been found to have little or no impact on learning outcomes. Repetitive interventions, rather than single interventions, were shown to be superior for learning outcomes. Settings similar to the workplace improved skill acquisition and performance. Computer-based learning can be equally or more effective than live instruction and more cost efficient if effective techniques are used. Effective techniques can lead to improvements in knowledge and skill outcomes and clinical practice behaviours, but there is less evidence directly linking CPE to improved clinical outcomes. Very limited quality data are available from low- to middle-income countries.

Conclusions: Educational techniques are critical to learning outcomes. Targeted, repetitive interventions can result in better learning outcomes. Setting should be selected to support relevant and realistic practice and increase efficiency. Media should be selected based on the potential to support effective educational techniques and efficiency of instruction. CPE can lead to improved learning outcomes if effective techniques are used. Limited data indicate that there may also be an effect on improving clinical practice behaviours. The research agenda calls for well-constructed evaluations of culturally appropriate combinations of technique, setting, frequency and media, developed for and tested among all levels of health workers in low- and middle-income countries.

PubMed Disclaimer

Inclusion process for articles included…

Inclusion process for articles included in the analysis.

Illustration of categorization terminology in…

Illustration of categorization terminology in panels a-c.

Similar articles

- Beyond the black stump: rapid reviews of health research issues affecting regional, rural and remote Australia. Osborne SR, Alston LV, Bolton KA, Whelan J, Reeve E, Wong Shee A, Browne J, Walker T, Versace VL, Allender S, Nichols M, Backholer K, Goodwin N, Lewis S, Dalton H, Prael G, Curtin M, Brooks R, Verdon S, Crockett J, Hodgins G, Walsh S, Lyle DM, Thompson SC, Browne LJ, Knight S, Pit SW, Jones M, Gillam MH, Leach MJ, Gonzalez-Chica DA, Muyambi K, Eshetie T, Tran K, May E, Lieschke G, Parker V, Smith A, Hayes C, Dunlop AJ, Rajappa H, White R, Oakley P, Holliday S. Osborne SR, et al. Med J Aust. 2020 Dec;213 Suppl 11:S3-S32.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50881. Med J Aust. 2020. PMID: 33314144

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, Moraleda C, Rogers L, Daniels K, Green P. Crider K, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1;2(2022):CD014217. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014217. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022. PMID: 36321557 Free PMC article.

- The effectiveness of internet-based e-learning on clinician behavior and patient outcomes: a systematic review protocol. Sinclair P, Kable A, Levett-Jones T. Sinclair P, et al. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015 Jan;13(1):52-64. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1919. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015. PMID: 26447007

- Cultural competence education for health professionals. Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J. Horvat L, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 May 5;2014(5):CD009405. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009405.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. PMID: 24793445 Free PMC article. Review.

- Effectiveness of continuing medical education. Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, Wilson LM, Ashar BH, Magaziner JL, Miller RG, Thomas PA, Prokopowicz GP, Qayyum R, Bass EB. Marinopoulos SS, et al. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007 Jan;(149):1-69. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007. PMID: 17764217 Free PMC article. Review.

- Evaluating the implementation of the Pediatric Acute Care Education (PACE) program in northwestern Tanzania: a mixed-methods study guided by normalization process theory. Mwanga JR, Hokororo A, Ndosi H, Masenge T, Kalabamu FS, Tawfik D, Mediratta RP, Rozenfeld B, Berg M, Smith ZH, Chami N, Mkopi NP, Mwanga C, Diocles E, Agweyu A, Meaney PA. Mwanga JR, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024 Sep 13;24(1):1066. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11554-3. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024. PMID: 39272036

- Perceived barriers and opportunities of providing quality family planning services among Palestinian midwives, physicians and nurses in the West Bank: a qualitative study. Hassan S, Masri H, Sawalha I, Mortensen B. Hassan S, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024 Jul 9;24(1):786. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-11216-4. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024. PMID: 38982474 Free PMC article.

- Development and initiation of a preceptor program to improve midwifery and nursing clinical education in sub-saharan Africa: protocol for a mixed methods study. van de Water B, Renning K, Nyondo A, Sonnie M, Longacre AH, Ewing H, Fullah M, Chepuka L, Mann J. van de Water B, et al. BMC Nurs. 2024 May 31;23(1):365. doi: 10.1186/s12912-024-02036-2. BMC Nurs. 2024. PMID: 38822288 Free PMC article.

- Digital Training for Nurses and Midwives to Improve Treatment for Women with Postpartum Depression and Protect Neonates: A Dynamic Bibliometric Review Analysis. Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou M, Orovou E, Zournatzidou G. Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou M, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 May 14;12(10):1015. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12101015. Healthcare (Basel). 2024. PMID: 38786425 Free PMC article. Review.

- Use of digital technologies for staff education and training programmes on newborn resuscitation and complication management: a scoping review. Horiuchi S, Soller T, Bykersma C, Huang S, Smith R, Vogel JP. Horiuchi S, et al. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2024 May 15;8(1):e002105. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2023-002105. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2024. PMID: 38754893 Free PMC article. Review.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, Fineberg H, Garcia P, Ke Y, Kelley P, Kistnasamy B, Meleis A, Naylor D, Pablos-Mendez A, Reddy S, Scrimshaw S, Sepulveda J, Serwadda D, Zurayk H. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. - DOI - PubMed

- Wittemore R, Kanfl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. In J Adv Nursing. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. - DOI - PubMed

- Marinopoulos SS, Baumann MH. American College of Chest Physicians Health and Science Policy Committee: Methods and definition of terms: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 Suppl):17S–28S. - PubMed

- Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence. Oxford: Centre for Evidence Based Medicine; 2011. http://www.cebm.net/?O=1025 .

- Best Evidence in Medical Education (BEME) Appendix 1-BEME Coding Sheet. 2011. http://www.medicalteacher.org/MEDTEACH_wip/supp%20files/BEME%204%20Figs%... .

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- BioMed Central

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.