Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Universality of universal health coverage: A scoping review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations School of Public Health, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision

Affiliation College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Affiliation School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Aklilu Endalamaw,

- Charles F. Gilks,

- Fentie Ambaw,

- Yibeltal Assefa

- Published: August 22, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507

- Reader Comments

16 May 2024: Endalamaw A, Gilks CF, Ambaw F, Assefa Y (2024) Correction: Universality of universal health coverage: A scoping review. PLOS ONE 19(5): e0304023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304023 View correction

The progress of Universal health coverage (UHC) is measured using tracer indicators of key interventions, which have been implemented in healthcare system. UHC is about population, comprehensive health services and financial coverage for equitable quality services and health outcome. There is dearth of evidence about the extent of the universality of UHC in terms of types of health services, its integrated definition (dimensions) and tracer indicators utilized in the measurement of UHC. Therefore, we mapped the existing literature to assess universality of UHC and summarize the challenges towards UHC.

The checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis extension for Scoping Reviews was used. A systematic search was carried out in the Web of Science and PubMed databases. Hand searches were also conducted to find articles from Google Scholar, the World Bank Library, the World Health Organization Library, the United Nations Digital Library Collections, and Google. Article search date was between 20 October 2021 and 12 November 2021 and the most recent update was done on 03 March 2022. Articles on UHC coverage, financial risk protection, quality of care, and inequity were included. The Population, Concept, and Context framework was used to determine the eligibility of research questions. A stepwise approach was used to identify and select relevant studies, conduct data charting, collation and summarization, as well as report results. Simple descriptive statistics and narrative synthesis were used to present the findings.

Forty-seven papers were included in the final review. One-fourth of the articles (25.5%) were from the African region and 29.8% were from lower-middle-income countries. More than half of the articles (54.1%) followed a quantitative research approach. Of included articles, coverage was assessed by 53.2% of articles; financial risk protection by 27.7%, inequity by 25.5% and quality by 6.4% of the articles as the main research objectives or mentioned in result section. Most (42.5%) of articles investigated health promotion and 2.1% palliation and rehabilitation services. Policy and healthcare level and cross-cutting barriers of UHC were identified. Financing, leadership/governance, inequity, weak regulation and supervision mechanism, and poverty were most repeated policy level barriers. Poor quality health services and inadequate health workforce were the common barriers from health sector challenges. Lack of common understanding on UHC was frequently mentioned as a cross-cutting barrier.

Conclusions

The review showed that majority of the articles were from the African region. Methodologically, quantitative research design was more frequently used to investigate UHC. Palliation and rehabilitation health care services need attention in the monitoring and evaluation of UHC progress. It is also noteworthy to focus on quality and inequity of health services. The study implies that urgent action on the identified policy, health system and cross-cutting barriers is required to achieve UHC.

Citation: Endalamaw A, Gilks CF, Ambaw F, Assefa Y (2022) Universality of universal health coverage: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 17(8): e0269507. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507

Editor: Wen-Wei Sung, Chung Shan Medical University, TAIWAN

Received: May 27, 2022; Accepted: August 9, 2022; Published: August 22, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Endalamaw et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its supporting information files.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: Authors declared no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations: ANC, Antenatal Care; AR, Antiretroviral Therapy; CHI, Catastrophic Health Expenditure; FP, Family Planning; GBD2019, Global Burden Disease 2019; HIV/AIDS, Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome; IDs, Infectious diseases; NCDs, Non-communicable diseases; RMNC, Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal and Child; SCA, Service Capacity and Access; SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; UN, United Nations; UHC, Universal Health Coverage; WB, World Bank; WHO, World Health Organization

Introduction

Universal health coverage (UHC) is a multi-dimensional concept that includes population coverage, services coverage and financial protection as its building blocks, as well as equity and quality in its integrated definition [ 1 ]. Health policy and decision makers believe UHC as a foundation to improve population’s health, facilitate economic progress, and achieve social justice [ 2 , 3 ]. It is also essential to minimize disparities, promote effective and comprehensive health governance, and build resilient health systems [ 4 ].

The United Nation’s (UN) post-2015 goals described UHC as the predominant approach to realize the 2030’s sustainable health goals [ 5 ]. It is also taken as an urgent priority in 2020 UHC high-level meeting to address global health crises, through delivering affordable essential quality healthcare services, including the pandemic COVID-19 [ 6 ]. The UN General Assembly further declared, at its 73 rd session, that global institutions and countries make healthcare accessible to one billion more people by 2023 [ 7 ] and 80 percent of the population by 2030 with no catastrophic health expenditures [ 5 ].

WHO and the WB established core tracers of health service coverage to monitor UHC [ 8 ]. These tracers are categorized under the main theme reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health (RMNC), infectious diseases (IDs), non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and service capacity and access (SCA). Another dimension of UHC in SDG 3.8.2 is financial risk protection, which is typically measured by catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) and impoverishment due to healthcare costs [ 8 ].

While no prior studies have been conducted to identify and map the available evidence on UHC, other related studies such as “a synthesis of conceptual literature and global debates” [ 1 ] and a scoping review of “implementation research approaches of UHC” [ 9 ] are available. In addition to these literature, another study assessed the hegemonic nature of UHC in health policy described historical background of how UHC emerged, and frequency of UHC mentioned in all fields of articles available in PubMed database [ 10 ]. None of those previous studies addressed the universality of UHC in terms of its building blocks and service types and summarized the findings from each study included in the review.

A scoping review of the studies on UHC and its dimensions is crucial to map and characterize the existing studies towards UHC. This will help to identify key concepts, gaps in the research, and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policymaking, and research [ 11 ]. The goals of this scoping review towards universality of UHC were, first, to determine the distribution of articles across WHO and WB regions, health service types, and dimensions including major components and tracer indicators, and second, to synthesize barriers of UHC. This review provides insight that is useful in setting strategies, evaluating health service performance, and advancing knowledge on priority research questions for future studies.

Identifying a research question

The protocol of this scoping review is available elsewhere https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1082468/v1 . The overall activities adhered to the Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) scoping review framework [ 12 ], which was expanded with a methodological enhancement for scoping review projects [ 13 ], and the Joanna Briggs Institute framework [ 14 ]. The review followed five steps: (1) identifying research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) data charting, and (5) collation, summarization, and reporting of results. The checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis extension for Scoping Reviews were used ( S1 Checklist ) [ 15 ].

The research questions were developed by AE in collaboration with YA. The Population, Concept, and Context framework was used to determine the eligibility of research questions [ 16 ]. According to the framework, the population represented study participants to whom findings infer which includes people at any age or other important characteristics of study participants. Not all UHC expected to have population component, which is non-applicable in some research. The concept was overall UHC or financial risk protection, equity, quality, and coverage. Context includes the study settings or countries and, in this review, the global context.

Identifying relevant studies

Web of Science, PubMed and Google Scholar were used to find literature in the field. Hand search was also used to find articles from WB Library, WHO Library, UN Digital Library Collections, and Google. Using the relevant keywords and/or phrases, a comprehensive search strategy was established. Universal, health, "health care", healthcare, "health service”, quality, access, coverage, equity, disparity, inequity, equality, inequality, expenditure, and cost were search words and/or phrases. “AND” or “OR” Boolean operators were used to broaden and narrow the specific search results. Search strings were formed in accordance with the need for databases ( S1 Table ). Article search date was between 20 October 2021 and 12 November 2021, with the most recent update on 03 March 2022. The articles were imported into EndNote desktop version x7, which was used to perform an automatic duplication check. Manual duplication removal was also performed. The database search strategies are shown in the ( S1 Table ).

Study selection

In consultation with YA, AE developed and tested study selection forms (inclusion and exclusion criteria) using a random sample from collected references, which were found using search strategy. A second meeting was held to approve the study screening form and process. Then, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied during the article screening process for all articles. Studies conducted using the English language were included. Articles on overall UHC (UHC effective service coverage and FRP), UHC effective service coverage, UHC without specification with service coverage and FRP, and which reported coverage, quality, inequity, FRP in the outcome of the study or explored UHC research objectives were included. Types of study design included were quantitative, qualitative, mixed-research, and review types. The search was narrowed to include only literature published since 2015 to find studies which addressed the SDG target 3.8 and proceeding years. Non-English language literature, abstracts only, comments or letters to the editor, erratum, corrections, and brief communications were all excluded.

Articles’ titles, abstracts, and full texts were reviewed in stages. After duplicates were removed using EndNote desktop x7 software and manual duplication removal, titles were screened. After that, abstracts were used to screen the literature. Those who passed abstract review were eligible for full-text review. Full-text articles were also screened for data charting purposes. For articles with only an abstract, contact was made with the study’s corresponding authors.

Data charting

A piloted and refined data extraction tool was initially developed to chart the results of the review from full-text literature. Data was examined, charted, and sorted according to key issues and themes. Author(s), publication year, WHO geographic category, WB group, study approach, studied domain or topic, UHC themes, and health care service types were all extracted.

Collation, summarization, and report of results

Based on years of publication, studied dimensions (interrelated objectives), WHO region, WB group, study approach, and health care service types, available articles were compiled and summarized with frequency and percentage.

A simple descriptive analysis was performed, and the results were presented in the form of tables and figure. The data reporting scheme was adjusted as needed based on the findings.

Search results

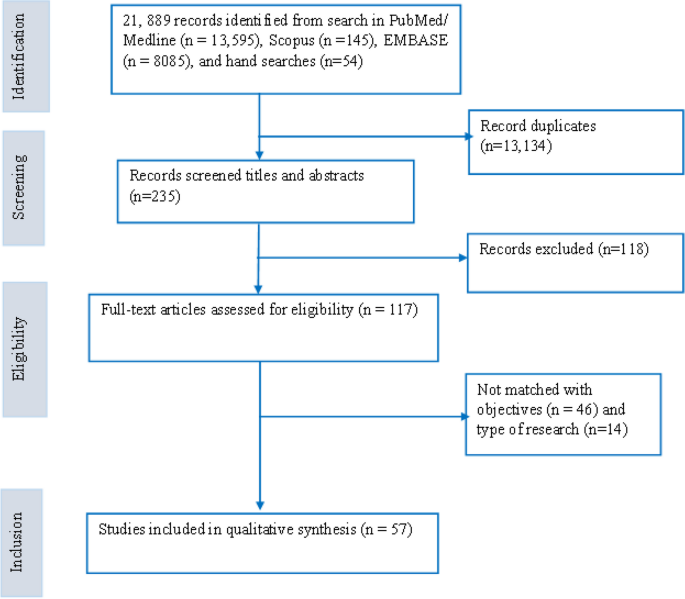

PubMed (n = 6,230) and Web of Science (n = 832) databases were searched. Google Scholar (n = 21), WB Library (n = 5), WHO Library (n = 7), UN Digital Library Collections (n = 13), and Google (n = 63) were also manually searched. A total of 7,171 records were discovered. Following title and abstract screening, 65 articles were chosen for full-text review. Finally, 47 articles were selected for scoping review ( Fig 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507.g001

Articles characteristics

Almost one-fourth of articles were from WHO Africa region and another 25.5% were across two or more WHO regions. According to income category, 42.5% were from lower-middle-income countries followed by 29.8% across two or more WB economy groups. More than half of the articles (54.1%) followed a quantitative research approach ( Table 1 ). The countries where each article conducted are available in S2 Table .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507.t001

Health service types

Twenty articles [ 17 – 36 ] are categorized under health promotion. These articles were focused on pathways and efforts, program evaluation and change, opportunities and challenges, barriers/factors/enablers, community-based health planning and service initiative, perceived effect of health reform on UHC, health-seeking behaviour and knowledge, health security and health promotion activities, the impact of insurance on coverage, and SCA dimensions of UHC. Health promotion encompasses funding and infrastructure, health literacy, the development of healthy public policies, the creation of supportive environments, and the strengthening of community actions and skills, as well as any activities that assist governments, communities, and individuals in dealing with and addressing health challenges.

Six articles discussed treatment aspects of health services, which were access to care for illness, access to treatment for rheumatic heart diseases, neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), mental disorders and hypertension [ 37 – 42 ].

According to GBD-2019, WHO and WB tracers, FP and/or SCA components for promotion, immunization for prevention and other diseases in RMNC, IDs, NCDs for treatment aspects, nineteen articles were a combination of promotion, prevention, and treatment aspects [ 43 – 61 ].

One study looked at both the promotion and treatment of health services [ 62 ].

One study done on the quality of health care for disabled people [ 63 ] was classified as a palliative and rehabilitative care service type despite it did not adhere to palliative care assessment guidelines.

Components and dimensions of UHC

The main four components of UHC are RMNC, IDs, NCDs and SCA. Of included articles, RMNC was reported by 19 articles, 17 assessed NCDs were reported by 17 articles, CDs was assessed by 13 articles, and SCA was assessed by 9 articles. Regarding dimensions, coverage was assessed by 25 of articles; FRP by 13 articles, inequity by 10 articles and quality by 3 articles ( S2 Table ).

Tracer indicators for summary measure of UHC

Of 25 quantitative articles, 19 articles used various tracer indicators to assess UHC quantitatively; the remaining six quantitative articles assessed each empirical analysis of the potential impact of importing health services, access and financial protection of emergency cares, perceived availability and quality of care, the performance of district health systems, crude coverage and financial protection, health-seeking behaviour and OOP health expenditures, and the performance of health system.

Accessibility and affordability in China [ 64 ], as well as curative care and quality of care components in India [ 48 ] were developed as new tracers.

Ten tracers were used in RMNC component of UHC. Five tracers in IDs, seven tracers in SCA and 18 tracers were used NCDs component of UHC. Three tracers were used for FRP estimation. The iteration of tracers under four components of UHC effective service coverage and FRP is shown in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507.t002

Barriers/challenges of UHC

Policy, health sector and cross-cutting barriers of UHC were identified. Financing, leadership/governance, inequity, regulation and supervision mechanism, and poverty were most repeated policy level barriers. Poor quality health services and inadequate health workforce were the common barriers from health sector challenges. Lack of common understanding on UHC was frequently mentioned cross-cutting barriers ( Table 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507.t003

The purpose of this scoping review was to map existing research, and the most researched UHC dimensions, components and summarized main findings. Many articles were found in the African region and in countries with middle-income (lower and upper). Many of the studies followed a quantitative research approach. Palliative and rehabilitative health care types did not be well address in UHC research. The service coverage and financial protection dimensions were most frequently studied, followed by inequity and quality of health care services.

The current evidence found a greater number of articles than a scoping review of African implementation research of UHC [ 65 ]. This is because the former was conducted on a single continent and concentrated on UHC research approaches. Another bibliometric analysis, on the other hand, discovered a greater number of available evidence than the current scoping review [ 66 ]. Because it includes all available evidence as terminology, title, phrases, or words in policy documents, commentaries, editorials, and all frequency counts found in databases by the first search without the conditions of pre-established exclusion criteria. Aside from that, the bibliometric analysis included articles dating back to 1990. UHC is a global agenda that has improved the health of the global population through political support, funding, and active national and international collaborations [ 67 , 68 ]. The number of research output is likely increasing over time though current evidence shows that comparable numbers of articles are available in each year. An earlier bibliometric analysis discovered an increasing trend of UHC research outputs [ 66 ].

Many of the studies in this review used a quantitative approach. A prior scoping review conducted in Africa discovered that qualitative and mixed-methods studies were the commonest method to investigate UHC [ 10 ]. The former study did not consider financial protection research, UHC effective service and crude coverage, service capacity and access. UHC is intended to be quantified numerically as a summary index to track the progress of health care performance. Given the nature of UHC, fewer articles used qualitative research design to investigate its challenges, opportunities, and success of UHC. Various health systems and policies in low, middle, and high-income countries may present different barriers and facilitators to achieve UHC [ 69 – 71 ]. The current review has also identified policy, health system and cross-cutting barriers of UHC that were frequently explored by qualitative research.

Many number of countries are available in the European region and the high-income category [ 72 , 73 ]. In contrast, a substantial amount of UHC research was produced in middle-income countries, most were from African region. Trend analysis in health policy and systems research conducted on the overall research progress discovered that an increasing trend of publications in low-and middle-income countries between 2003 and 2009 [ 74 ]. This could be attributed to the nature of the health problems and the health policy in place regarding health research. Furthermore, health research budgets and clinical trial infrastructures may determine health research activities in each continent. Health budget might not always true in its effect of high research publication. For instance, evidence from a review finding indicated that nations with significant donor investment in health research may not necessarily produce a large number of research [ 75 ]. Articles available across WHO regions were comparable to frequency of articles in WHO African region. This might be due to UHC is a global strategy in monitoring the global process towards universal access to health care. The availability of UHC monitoring framework helps to conduct to conduct research at the multicounty level.

In 2019, the burden of NCDs was 63.8 percent worldwide, followed by IDs, RMNC, and nutritional disease (26.4 percent) [ 76 ]. In the summary measure of the UHC index, RMNC was the most frequently studied component followed by NCDs. This could be because many of the articles in the current review came from Africa and lower-and middle-income countries. In these countries, maternal and child morbidity and mortality were extremely high [ 77 ], making RMNC more likely to be investigated in UHC context. Similarly, a scoping review study on maternal, neonatal, and child health realized a high rate of publication in the most recent period [ 78 ].

This review provides an answer to the question of how much UHC is universal and how much UHC is covered in the current health systems and policy research. UHC tracer indicators are focused on health promotion, disease prevention, treatment, palliative, and rehabilitative health care services at the individual and population level. Promotion aspects of health services were more frequently investigated in the current review. This could be because those articles non-specific to either component of UHC were classified as health promotion. A single study was conducted on disabled population, close to palliative and rehabilitative health care types. Palliative care focuses on the physical, social, psychological, spiritual, and other issues confronting adults and children living with and dying from life-limiting conditions, as well as their families [ 79 ]. Assessment of pain and symptom management, functional status, psychosocial care, caregiver assessment, and quality of life are all part of a palliative care measurement and evaluation domains [ 80 ]. The Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance recommended research to improve palliative care coverage [ 81 ] in order to ensure equitable health care access for more than 40 million people who require palliative care each year worldwide [ 82 ]. However, UHC effective service coverage measurement indicators are appropriate only for assessing the promotion, prevention and treatment aspects of health care, even though all health care services are theoretically expected to be covered [ 54 ].

In terms of dimensions, coverage was more commonly studied. The framework for monitoring and tracking was initially established for effective service coverage and FRP. UHC’s service coverage is a collection of many individual disease indicators used to assess the performance of the health care system. Therefore, it is not surprising that many articles have been written about the coverage dimension. Aside from the usual trend of calculating the service coverage summary index, a few articles estimated UHC by combining effective service coverage and FRP indicators. In the current review, a few studies assessed the quality of care as a dimension of UHC; a single study developed a distinct quality of care measurement that integrated into the UHC matrix. Effective service coverage is predicated on the assumption that those in need receive high-quality health care services. Effective services coverage and quality are theoretically integrated. However, having a high UHC index value does not imply that high-quality care is provided for each specific disease. For example, in countries with high UHC index value [ 54 ], quality medical care services were found to be inadequate for patients with chronic diseases [ 83 ]. Quality of health care can be assessed using structure, process, and outcome indicators in the healthcare system [ 84 ].Therefore, generally, measuring the quality of care for specific disease is helpful for stakeholders, clinicians, and health policymakers working on specific health problems [ 85 ].

The UHC summary index is also useful in comparing the national and subnational progress of health system performance between countries and within a specific country. One of UHC’s primary functions is to promote health equity [ 3 ], and equity has been identified as a measurable component of UHC [ 86 ]. It is linked to social determinants that should be monitored over time, across or within different settings and populations [ 87 ]. Inequity in UHC service coverage studies was reported broadly. None of the UHC articles examined health disparities based on age, gender, race or ethnicity, residence, education level, or socioeconomic status. Moreover, range, absolute or relative difference, concentration index, and Gini coefficient were not used as equity measurement techniques in the included articles.

As implication to policy/program manager and researcher, more research is needed in settings where UHC has not been thoroughly investigated qualitatively. Future research better focus on the quality and equity dimension of UHC health care services. Given that the distinct nature of UHC tracers may limit UHC’s articles on health promotion, prevention, and treatment aspects, palliative and rehabilitative care services require attention in the future research environment. For specific health problems, additional review may be required to identify research gaps in specific tracer.

Strength and limitation

This is the first scoping review of UHC, and it is accompanied by the most recent articles. Our review identified UHC literature in each category of health service type.

In terms of limitations, this review included only articles conducted in English; articles conducted in other languages may have been missed, and geographical representation of UHC articles may have been over or underestimated for regions. When considering UHC dimensions, they may have a different level of research articles discovered if another mapping review is done for specific disease types.

Most articles were from Africa, across WHO regions and middle-income countries. Quantitative research approach has been frequently used. Equity and quality of services have got little attention in UHC research. Palliation and rehabilitation health services have also got little attention in the UHC research. Tracer indicators other than WHO and WB were developed and utilized in different countries. Policy, health sector and cross-cutting barriers of UHC were identified. Financing, leadership/governance, inequity, regulation and supervision mechanism, and poverty were most repeated policy level barriers. Poor quality health services and inadequate health workforce were the common challenges of the health sector towards UHC. Lack of common understanding on UHC was frequently mentioned as cross-cutting barrier.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. items followed in conducting this review..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507.s001

S1 Table. Search strategy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507.s002

S2 Table. Articles’ country and main findings.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269507.s003

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 6. uhc 2030. State of commitment to universal health coverage: synthesis, 2020 2020 Available from: https://www.uhc2030.org/blog-news-events/uhc2030-news/state-of-commitment-to-universal-health-coverage-synthesis-2020-555434/ .

- 16. The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2014 edition/supplement. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Universal healthcare in the united states of america: a healthy debate.

1. Introduction

2. argument against universal healthcare, 3. argument for universal healthcare, preventive initiatives within a universal healthcare model, 4. conclusions, author contributions, conflicts of interest.

- NBC News/Wall Street Journal Survey ; Study #19175; Hart Research Associates/Public Opinion Strategies: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- WHO. Universal Health Coverage. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/universal_health_coverage/en/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Light, D.W. Universal health care: Lessons from the British experience. Am. J. Public Health 2003 , 93 , 25–30. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Chernichovsky, D.; Leibowitz, A.A. Integrating public health and personal care in a reformed US health care system. Am. J. Public Health 2010 , 100 , 205–211. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Unger, J.P.; De Paepe, P. Commercial Health Care Financing: The Cause of U.S., Dutch, and Swiss Health Systems Inefficiency? Int. J. Health Serv. 2019 , 49 , 431–456. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Country Rankings: World & Global Economy Rankings on Economic Freedom. Available online: https://www.heritage.org/index/ranking (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Economic Freedom of the World. Cato Institute. Available online: https://www.cato.org/economic-freedom-world (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Disparities|Healthy People 2020. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Fuchs, V.R. How and why US health care differs from that in other OECD countries. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013 , 309 , 33–34. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Blahous, C.; Fish, J.; Smith, L.F.; Strategist, S.R. The Costs of a National Single-Payer Healthcare System. 2018. Available online: https://www.mercatus.org/publications/federal-fiscal-policy/costs (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Daniels, M.; Panetta, L.; Penny, T. Primary Care: Estimating Democratic Candidates’ Health Plans ; Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sessions, S.Y.; Lee, P.R. A road map for universal coverage: Finding a pass through the financial mountains. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 2008 , 33 , 155–197. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Sanders, B. Options to Finance Medicare for All. 2020. Available online: https://www.sanders.senate.gov/download/options-to-finance-medicare-for-all?inline=file (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Thorpe, K.E. An Analysis of Senator Sanders Single Payer Plan. 2016. Available online: https://berniesanders.com/issues/ (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Skocpol, T. Boomerang: Health Care Reform and the Turn Against Government ; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 133–143. [ Google Scholar ]

- Podemska-Mikluch, M. Understanding Medicare’s Impact on Innovation: A Framework for Policy Reform. 2018. Available online: https://www.mercatus.org/publications (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Barua, B. Waiting Your Turn: Wait Times for Health Care in Canada, 2017 Report ; Fraser Institute: Vancouver, CO, Canada, 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arguing for Universal HealtH Coverage ; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- A Vision for Primary Care in the 21st Century: Towards Universal Health Coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals ; UNICEF, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Crowley, R.; Daniel, H.; Cooney, T.G.; Engel, L.S. Envisioning a better U.S. health care system for all: Coverage and cost of care. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 , 172 , S7–S32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Doherty, R.; Cooney, T.G.; Mire, R.D.; Engel, L.S.; Goldman, J.M. Envisioning a Better U.S. Health Care System for All: A Call to Action by the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 , 172 , S3. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ward, B.W.; Schiller, J.S.; Goodman, R.A. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: A 2012 update. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014 , 11 , E62. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Fryar, C.D.; Chen, T.-C.; Li, X. Prevalence of uncontrolled risk factors for cardiovascular disease: United States, 1999–2010. NCHS Data Brief 2012 , 1–8. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23101933 (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- Pampel, F.C.; Krueger, P.M.; Denney, J.T. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Behaviors. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010 , 36 , 349–370. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Value of Health Insurance: Few of the Uninsured Have Adequate Resources to Pay Potential Hospital Bills|ASPE . Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/value-health-insurance-few-uninsured-have-adequate-resources-pay-potential-hospital-bills (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- McBride, T.D. Uninsured spells of the poor: Prevalence and duration. Health Care Financ. Rev. 1997 , 19 , 145–160. [ Google Scholar ]

- Saydah, S.H.; Imperatore, G.; Beckles, G.L. Socioeconomic status and mortality: Contribution of health care access and psychological distress among U.S. adults with diagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013 , 36 , 49–55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- American Diabetes Association. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 2013 , 36 , 1033–1046. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Lim, S.S.; Vos, T.; Flaxman, A.D.; Danaei, G.; Shibuya, K.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Amann, M.; Anderson, H.R.; Andrews, K.G.; Aryee, M.; et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012 , 380 , 2224–2260. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Leng, B.; Jin, Y.; Li, G.; Chen, L.; Jin, N. Socioeconomic status and hypertension: A meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2015 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kirkland, E.B.; Heincelman, M.; Bishu, K.G.; Schumann, S.O.; Schreiner, A.; Axon, R.N.; Mauldin, P.D.; Moran, W.P. Trends in healthcare expenditures among US adults with hypertension: National estimates, 2003–2014. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Bhurosy, T.; Jeewon, R. Overweight and obesity epidemic in developing countries: A problem with diet, physical activity, or socioeconomic status? Sci. World J. 2014 , 2014 , 964236. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Hammond, R.A.; Levine, R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2010 , 3 , 285–295. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Clark, G.; O’Dwyer, M.; Chapman, Y.; Rolfe, B. An Ounce of Prevention is Worth a Pound of Cure-Universal Health Coverage to Strengthen Health Security. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2018 , 5 , 155–164. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- A Better-Quality Alternative: Single-Payer National Health System Reform|Physicians for a National Health Program. Available online: https://www.pnhp.org/publications/a_better_quality_alternative.php?page=all (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Fielding, J.E.; Teutsch, S.; Koh, H. Health reform and healthy people initiative. Am. J. Public Health 2012 , 102 , 30–33. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- CDC The Power of Prevention. 2009. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/pdf/2009-power-of-prevention.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Levi, J.; Segal, L.; Juliano, C. Issue Report: Prevention for a Healthier America: Investments in Disease Prevention Yield Significant Savings, Stronger Communities ; Trust for America’s Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee, B.Y.; Adam, A.; Zenkov, E.; Hertenstein, D.; Ferguson, M.C.; Wang, P.I.; Wong, M.S.; Wedlock, P.; Nyathi, S.; Gittelsohn, J.; et al. Modeling the economic and health impact of increasing children’s physical activity in the United States. Health Aff. 2017 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hamasaki, H. Daily physical activity and type 2 diabetes: A review. World J. Diabetes 2016 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Magnussen, J.; Vrangbaek, K.; Saltman, R.B. Nordic Health Care Systems Recent Reforms and Current Policy Challenges Nordic Health Care Systems. Eur. Obs. Heal. Syst. Policies Ser. 2009 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Fullman, N.; Yearwood, J.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; Abebe, Z.; Abebo, T.A.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Blumenthal, D.; Abrams, M.; Nuzum, R. The Affordable Care Act at 5 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015 , 372 , 2451–2458. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Zieff, G.; Kerr, Z.Y.; Moore, J.B.; Stoner, L. Universal Healthcare in the United States of America: A Healthy Debate. Medicina 2020 , 56 , 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina56110580

Zieff G, Kerr ZY, Moore JB, Stoner L. Universal Healthcare in the United States of America: A Healthy Debate. Medicina . 2020; 56(11):580. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina56110580

Zieff, Gabriel, Zachary Y. Kerr, Justin B. Moore, and Lee Stoner. 2020. "Universal Healthcare in the United States of America: A Healthy Debate" Medicina 56, no. 11: 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina56110580

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- Open access

- Published: 04 January 2024

Building a resilient health system for universal health coverage and health security: a systematic review

- Ayal Debie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5596-8401 1 , 4 ,

- Adane Nigusie 2 ,

- Dereje Gedle 3 ,

- Resham B. Khatri 3 &

- Yibeltal Assefa 3

Global Health Research and Policy volume 9 , Article number: 2 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

3652 Accesses

3 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Resilient health system (RHS) is crucial to achieving universal health coverage (UHC) and health security. However, little is known about strategies towards RHS to improve UHC and health security. This systematic review aims to synthesise the literature to understand approaches to build RHS toward UHC and health security.

A systematic search was conducted including studies published from 01 January 2000 to 31 December 2021. Studies were searched in three databases (PubMed, Embase, and Scopus) using search terms under four domains: resilience, health system, universal health coverage, and health security. We critically appraised articles using Rees and colleagues’ quality appraisal checklist to assess the quality of papers. A systematic narrative synthesis was conducted to analyse and synthesise the data using the World Health Organization’s health systems building block framework.

A total of 57 articles were included in the final review. Context-based redistribution of health workers, task-shifting policy, and results-based health financing policy helped to build RHS. High political commitment, community-based response planning, and multi-sectorial collaboration were critical to realising UHC and health security. On the contrary, lack of access, non-responsive, inequitable healthcare services, poor surveillance, weak leadership, and income inequalities were the constraints to achieving UHC and health security. In addition, the lack of basic healthcare infrastructures, inadequately skilled health workforces, absence of clear government policy, lack of clarity of stakeholder roles, and uneven distribution of health facilities and health workers were the challenges to achieving UHC and health security.

Conclusions

Advanced healthcare infrastructures and adequate number of healthcare workers are essential to achieving UHC and health security. However, they are not alone adequate to protect the health system from potential failure. Context-specific redistribution of health workers, task-shifting, result-based health financing policies, and integrated and multi-sectoral approaches, based on the principles of primary health care, are necessary for building RHS toward UHC and health security.

Resilient health system (RHS) is essential to ensure universal health coverage (UHC) and health security. It is about the health system’s preparedness and response to severe and acute shocks, and how the system can absorb, adapt and transform to cope with such changes [ 1 , 2 ]. Resilient health system reflects the ability to continue service delivery despite extraordinary shocks to achieving UHC [ 3 ]. A study in Nepal showed that adoption of coexistence strategy on the continuation of the international community on strengthening the health sector with the principle of “do-no-harm” and impartiality at the time of conflicts improve the health outcomes [ 4 ].

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopted a new development agenda aiming to transform the world by achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 [ 5 ], based on the lessons from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [ 6 ]. The SDGs seek to tackle the “unfinished business” of the MDGs era and recognise that health is a major contributor and beneficiary of sustainable development policies [ 7 ]. One of the 17 goals has been devoted specifically to health: “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages” [ 6 ]. All UN Member States have agreed to achieve UHC (target 3.8) by 2030, as part of the SDGs [ 8 ]. The 2030 UHC target was intended to reach at least 80% for the UHC service coverage index and 100% for financial protection [ 9 ]. Universal health coverage is achieved when everyone has access to essential healthcare services without financial hardship associated with paying for care [ 10 ].

Universal health coverage and health security are two sides of the same coin. They are interconnected and complementary goals that require strong health systems and public health infrastructure to ensure that everyone has access to essential health services [ 11 ]. Universal health coverage and health security require an integrated and multi-sectorial system strengthening to provide quality and equitable healthcare services across populations [ 12 ].

A resilient health system provides the foundation for both [ 11 ]. Strengthening the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) six health system building blocks, including service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, health financing, leadership and governance, and access to essential medicines and infrastructures are essential to achieve UHC and health security [ 13 ]. The 13th WHO programme is structured in three interconnected strategic priorities to ensure SDG-3 including: achieving UHC, addressing health emergencies, and promoting healthier populations [ 14 ].

In the World Health Organisation (WHO) European Region, health security emphasises on the analysis of infectious diseases, natural and human-made disasters, conflicts and complex emergencies, and potential future challenges from global changes, particularly climate change [ 15 ]. Health security is also considered as the activities required, both proactive and reactive, to minimise the danger and impact of acute public health events that endanger people’s health across geographical regions and international boundaries [ 16 ]. The links between health system and health security have started to emerge in several national strategic plans and global initiatives, such as the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) and One Health, which aim to better facilitate the implementation of the International Health Regulations (IHR) [ 17 ]. The aim of IHR is to prevent, detect, and respond to the international spread of disease in effective and efficient manner [ 18 ]. The GHSA also help countries to build their capacity to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease threats [ 19 ].

Although almost all nations are progressing towards UHC, the advancement in low and low-middle income countries (LLMICs) is slow [ 20 ]. This is because the ethos and organisations of many health systems are more suitable for yesterday’s disease burden than tomorrow [ 21 , 22 ]. Health systems of various nations faced numerous shocks, including public health, social, economic and political crises associated with COVID-19 [ 23 ]. The COVID -19 pandemic has made an unprecedented impact on the international community and exposed the vulnerabilities of the present global health architecture [ 24 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic is a perfect reminder that countries, individually and collectively, require a strong RHS now more than ever; however, there was no adequate evidence on the strategies toward RHS to improving UHC and health security. Thus, this study can inform the global health community on the lessons of RHS and its applications to UHC in pandemic and beyond. This review generally aimed to address the following research questions: 1) What are the existing evidence on the impact of RHS for UHC and health security? 2) What are the essential elements and characteristics of RHS for UHC and health security as per the WHO building blocks? and 3) What examples exist to demonstrate on how to build RHS core components for UHC and health security?

Registration and search strategy

This review was conducted and reported following enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTERQ). Following ENTERQ guidelines, the systematic review was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) on 02 January 2022 with registration: CRD42020210471. Studies were searched in three databases (PubMed, Embase and Scopus) using search terms of under four broader domains, including resilience, health system, universal health coverage, and health security. Additional literatures were identified by searching in Google and Google Scholar. The search strategies were built using the four domains of search terms, and “Title/Abstract” by linking “AND” and “OR” Boolean operator terms as appropriate (Additional file 1 ). We also used the ENTERQ checklist for reporting the articles (Additional file 2 ).

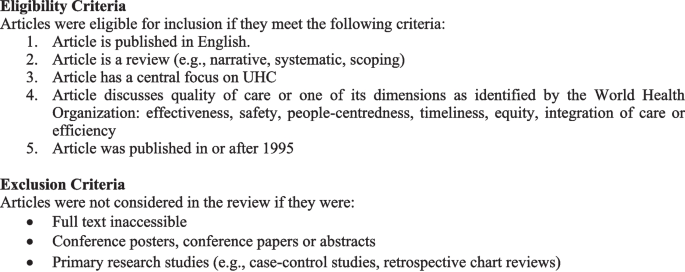

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All articles in relation to RHS towards UHC and health security were included in the review. Inclusion criteria were articles written in the English language published from 01 January 2000 to 31 December 2021. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were perspectives, commentary, expert’s opinion, conference papers, debates, conference reports, letters to the editor, and editorials. We presented this paper as a narrative review, following some components of the preferred reporting of systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guideline for scoping review (Additional file 3 ).

Selection process

The primary author (AD) imported all retrieved articles into the Endnote library to remove duplicates. After removing the duplicates, three authors (AD, AN and DG) independently screened the articles by title and abstract based on inclusion criteria. The senior authors (RBK and YA) mediated the discrepancies between the three reviewers through discussion. Finally, we retained and reviewed the full texts of all relevant studies for final data synthesis.

Data extraction and framework for synthesis

We used the Rees and colleagues’ appraisal instrument as a guiding tool to appraise the quality of included articles in the review [ 25 ]. The quality appraisal instrument is a comprehensive tool designed to assess the quality, rigor of research studies, covers key aspects of research design, data collection, analysis, and reporting. This includes rigour in sampling, rigour in data collection, rigour in data analysis, findings supported by the data, breadth and depth of findings, extent of the study privilege perspectives, reliability or trustworthiness, and usefulness[ 25 ]. A template was developed to extract relevant data from each eligible study. After reading the selected studies, key findings were extracted into the template, including information about the first author, year of publication, type of article, study design, and key summary findings. Three independent reviewers (AD, AN and DG) extracted the data. The senior authors (RBK and YA) verified the extracted information. The successes and challenges of RHS for UHC and health security were extracted using health system building blocks.

We analysed the findings using the WHO health system building blocks, including service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, medicines and infrastructures, healthcare financing, and leadership and governance [ 13 ]. We analysed the key challenges and successes of RHS for UHC and health security using the WHO health system frameworks. Framework analysis provides a systematic approach to analysing large amounts of textual data using pre-determined framework components. This allows the analyst and those commissioning the research to move between multiple layers of abstraction without losing sight of raw data [ 26 ].

Search results

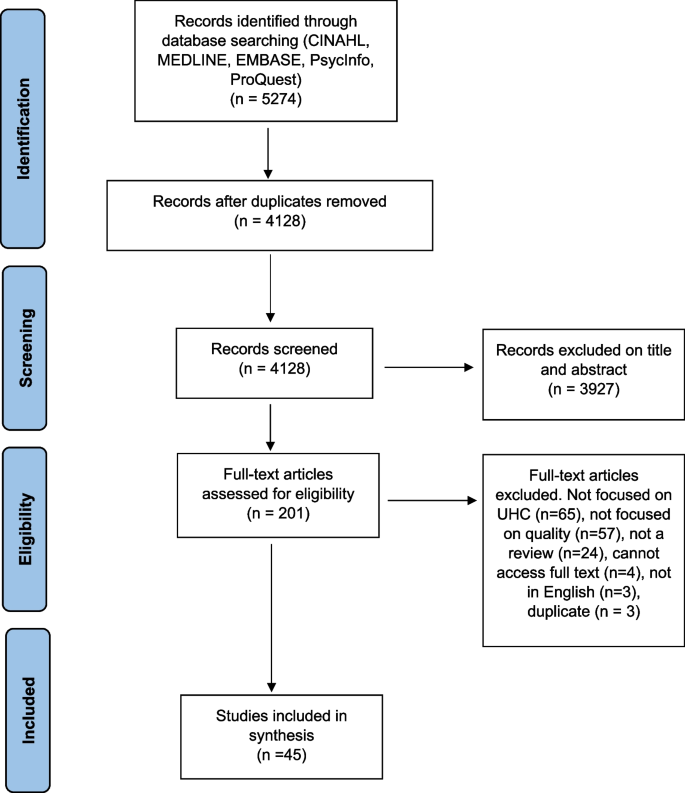

A total of 21,889 records were identified in the initial literature search. After removing 13,134 duplicates, 235 articles were screened by titles and abstracts, and 118 were excluded. Next, 117 studies were reviewed using the full texts, and finally, 57 articles met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed in the systematic review (Fig. 1 ). Of these, 32 articles were primary studies, and 25 articles investigated the application of RHS on UHC. In addition, nine articles explained RHS's implications on UHC and health security. Of these, approximately one-third (19 articles) were conducted in various African nations, while 19 articles were from Asian countries. The remaining articles were from other parts of the world. The study also reviewed articles on various aspects of health system building blocks, including health service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, health financing, leadership/governance, and medicines and infrastructure. The number of articles reviewed for each aspect were 17, 9, 10, 13, 22, and 10, respectively.

ENTREQ flow diagram for the articles included in the review

Successes and challenges of RHS

This review used the six-health system building blocks to achieve UHC and health security. These include service delivery, health workforce, health information system, health financing, medicines, diagnostics and infrastructures, and leadership and governance (Table 1 ).

Service delivery

Of the total reviewed articles, 17 described their healthcare service delivery findings. Good service delivery provides comprehensive and person-centered healthcare services with full accountability [ 27 ]. Continuation of healthcare service delivery in the face of extraordinary shocks facilitated UHC progress [ 3 ]. Studies reported that health service inputs, access to transportation, communication infrastructures, capacity building, referral systems, intersectoral actions, and electronic healthcare platforms could facilitate service delivery and improve access to health services [ 13 , 28 ]. Operational integration between health service continuity and emergency response through proactive planning across all income nations reduced health services disruptions during emergencies [ 29 ]. Community resources, cohesion, and physical accesses were significant assets to improve service utilisation and quality [ 30 ].

An inward migration or mass casualty incidents compromised the quality of services and increased deaths attributed to delays in treatment [ 30 ]. In the Ebola crisis, the long-standing lack of access to basic primary health care to isolate and treat infected people fueled the epidemic’s spread resulting in a death toll [ 31 ]. Uneven health facilities distribution and lack of well-trained personnel and supplies led to geographical inequities and poor healthcare access [ 32 , 33 ]. A combination of public health security threats, both new and reemerging infectious diseases, challenged ensuring health security [ 34 ]. For example, the health service delivery, mainly the lives of many children, was at risk associated with the lack of treatment for common childhood illnesses in Liberia during the Ebola outbreak [ 35 , 36 ]. Exclusion from work due to health problems can easily result in economic impoverishment and inequitable healthcare access, which will undoubtedly worsen health status [ 37 ]. For instance, socially excluded population groups received health services from a dysfunctional publicly provided health system marked by gaps and often invisible barriers in Guatemala and Peru, which undermines the progress towards UHC [ 38 ]. The changes in frequency, intensity, spatial extent, duration, and timing of extreme weather and climate events were also exposed to health threats [ 39 ]. For example, extreme weather events caused an increase in disease prevalence, such as malaria and other vector-borne diseases, malnutrition, food insecurity and food-borne diseases [ 40 ]. Inadequate primary health care system capacity to provide responsive health services to storm and flood-related health problems was another challenge [ 41 ].

Health workforce

In our review, nine articles reported their findings on the successes and challenges of health workforces towards UHC and health security. A well-performing health workforce provides responsive, fair and efficient health services to achieve the best health outcomes [ 27 ]. Task-shifting policy, ensuring accountability and ad hoc redistribution of health workers had a knock-on effect on health services delivery and building RHS [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Training on disaster preparedness and management, and rewarding packages, such as incentives and hazard allowance, facilitated healthcare workers willing to participate in disaster management [ 45 ]. Monitoring and evaluating frontline health workers levels of preparedness against public health emergency threats periodically by their higher-level hierarchy was crucial for early detection and control of health threats [ 46 ].

Lack of skilled and inadequate health workforce distribution was the major obstacle to containing an outbreak, and deaths were attributed to treatment delays [ 35 , 43 ]. Low perception of risks by tourists/ pilgrims, ineffective training, poor control of risk factors, and shortages of infrastructures were the challenges in combating contagious diseases [ 47 ]. Healthcare workers’ practices on effective pandemic management, including corona-virus disease (COVID)-19 were constrained by individual factors, such as education, residence, work station location, hygiene promotion, and social distance management [ 42 ]. Patient assessments by non-indigenous health workers during an emergency were also barriers to early identification and management of acute health events [ 30 ].

Health information system

In this review, ten articles described the contributions and challenges of health information on RHS to realise UHC and health security. A well-functioning HIS ensures the production, analysis, dissemination and use of reliable information for policy decisions [ 27 ]. Building accountability, knowledge culture management, and evidence through regular data quality audit strengthened health management information systems (HMIS) [ 44 ]. Integrated disease surveillance, flexible automation and data processing improved clinical care and health system preparedness to tackle health threats [ 48 , 49 , 50 ]. Strengthening the health system’s capacity was another key measure to rapidly process and communicate test results for pandemic responses [ 51 ].

Poor surveillance, late timing of responses and lack of triggers weakened the functionality of plans and exposed to a high burden of diseases [ 52 ]. Poor data management, misinformation on the risk and transmission, lack of awareness, resources and insufficient electronic reporting system were responsible for the spread of diseases [ 51 , 53 , 54 ]. For instance, misinformation during the Ebola outbreak affected most communities in putting measures in place to stop the spread of the virus [ 54 ]. People approached traditional healers who lacked knowledge on treating certain health shocks in modern medicine was the major problems in early responses [ 35 ].

Medical products, diagnostics, and infrastructures

Of the reviewed articles, 10 reported their findings on the successes and constraints of medical products, diagnostics, and infrastructures to realise UHC and health security. Equitable access to essential medical products, vaccines and technologies to assure quality, safety, efficacy and cost-effective healthcare services to users was the attribute of a well-functioning health system [ 27 ]. To attain UHC, strengthening local preparedness, planning, manufacturing, and coordinating public–private initiatives and training in LMICs was important [ 55 ]. The key factors to facilitate early detection were the provision of rapid, cost-effective, sensitive, and specific diagnostic centers through the inauguration of national centers [ 53 , 56 ]. Identifying emergency medicines, adaptable mobile health care units and systems for mobilisation of health professionals contributed to successful interventions to curb health emergencies [ 57 ].

High patient load, lack of diagnostics, destruction of health facilities and lack of specific funds for medicine procurement may compromise the health system’s hardware (health facilities and supplies) and contained public health threats [ 3 , 30 , 32 , 57 ]. For instance, inadequate essential logistics such as blood, oxygen cylinders, ergometrine and sulphadoxine paramita mine in Ghana was the causes for low level of preparedness to control maternal mortality [ 58 ]. Shortages of medical supplies, personal protective equipment (PPE), and electricity increased the rate of Ebola infections during the outbreak [ 35 ]. Most medicine outlets experienced longer lead times associated with the poor inter-country transportation and limited manufacturing capacity, which were also Namibia's main challenges [ 55 ].

Health financing

In this study, 13 articles described their findings on the contributions and limitations of healthcare financing to realise UHC and health security. A good health financing system raised adequate funds for health to ensure people can use needed services and be protected from financial catastrophes [ 27 ]. Under a publicly funded health financing system that fits well with values and population preferences improved compliance, sustainability, and equity [ 59 ]. An integrated financing mechanism through high income and risk cross-subsidies reduced reliance on OOP payments, maximises risk pools and resource allocation mechanisms facilitated to achieve UHC [ 60 ]. Universal health coverage can substantially improve human security through securing finances [ 61 ]. Universal health coverage indicators were also positively associated with the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and the share of health spending channels [ 62 ]. Income redistribution improved equity in health care service delivery [ 63 ].

Lack of adequate funds and non-affordable medical costs were the main barriers to universal financial protection and poor management of an outbreak [ 33 , 35 ]. In Burundi, for example, performance-based financing without accompanying access to incentives for the poor was the critical challenge to improve equity in health [ 64 ]. Health equity advancement challenges secured dedicated funds to support transformative learning opportunities and build infrastructures [ 65 ]. Because of causalities, the health sector requires additional financial support to address the increased demand for health services; however, movement restrictions limit people’s access to participate in gainful activities [ 30 ]. Low funds from international donors were erratic and far below the amounts required to meet the health needs at crisis time [ 66 ]. People could not trade their commodities because of the fear of attacks exposing service users to lack finances [ 30 ]. Falling in financial access to health services has resulted in political demonstrations and violent unrest [ 67 ].

Leadership and governance

Our review found that 22 articles reported their findings on health system governance (HSG) to realise UHC and health security. Good HSG ensured strategic policy frameworks combined with effective oversight, coalition, appropriate regulations, system design and accountability [ 27 ]. Building strong partnerships, ensuring accountability, coordination, rationalisation, and connection of pandemic planning across sectors and jurisdictions resulted in better preparedness [ 48 , 68 ]. Clear communication channels, multisectoral, and multilevel controls were essential to translate policy into actions [ 52 , 56 ]. Vertical and horizontal integration, centralised governance, responsible leadership, and social capital at community level were needed to address health shocks and homogenous implementation of health interventions [ 54 , 69 , 70 ]. Fueling high-performing teams and increasing investment in early warning and detection systems required leadership resilience to enable action at all levels [ 71 , 72 ].

Working alone the state had proven only partially effective, a situation exacerbated by the natural tendency within the public to ignore as irrelevant to themselves [ 73 ]. In addition, lack of clarity of stakeholder roles, poor leadership and absence of clear government policy for the delivery channels and financial coverage led to fragmentation and poor health system response [ 35 , 52 , 66 ]. For instance, weak governance and decision-making processes, such as high bureaucracy, low prevention culture, and lack of coordination between primary, social and hospital care providers, indicated virus’s rapid spread in the French population in the first wave of COVID-19 [ 74 ].

Moving away from a one-size fits-to all approach in guiding pandemic response, service delivery, political commitment, fair contribution and distribution of resources are helpful to speed up the path towards UHC [ 75 ]. For example, village health volunteers in Thailand, Zanmi Lazante’s Community Health Program in Haiti, Agentes Polivalentes Elementares in Mozambique, Village Health Teams in Uganda, lady health workers in Pakistan, BRAC in Bangladesh, Family Health Program in Brazil, and Health Extension Program in Ethiopia are successful community-based models contributed immensely to achieve health development goals [ 76 ]. In addition, community participation and coordination between different stakeholders significantly impact the prevention of encephalitis in Japan [ 77 ], and early detection of cases and collection of mortality data in Cambodia [ 78 ]. On the contrary, it was difficult for the system to automatically adjust its structure to reduce uncertainty and ascertain complex adaptive behaviour when facing public health emergencies [ 79 ].

With an overarching political will, well-integrated and locally grounded health system can be more resilient to external shocks [ 80 ]. Political leadership was critical during the crisis, which helped the government to develop a response strategy and effective implementation [ 81 ]. For instance, Singapore’s dexterous political environment allowed the government to institute measures to control COVID-19 swiftly [ 56 ]. On the other hand, political instability or war in Syria affected healthcare services by destroying physical health care infrastructures [ 3 ].

In this review, we developed a resilient health system framework that could assist countries in their endeavor toward universal health coverage and health security. The framework involves an integrated and multi-sectoral approach that considers the health system building blocks and contextual factors. The input components of the framework include health financing, health workforce, and infrastructure, while service delivery is the process component, and UHC and health security are the impact program components. The framework also considers health system performance attributes, such as access, equity, quality, safety, efficiency, sustainability, responsiveness, and financial risk protection. Additionally, the cross-cutting components of the framework are leadership and governance, health information systems (HIS), and contextual factors (e.g., political, environmental/climate, socioeconomic, and community engagement) that can affect the health system at any stage of the program components (Fig. 2 ).

Resilient health system framework for UHC and health security

We also indicated that RHS is critical to achieving UHC because it enables the provision of accessible, quality, and equitable health services, while also protecting people from financial risks associated with illness or injury. Such systems are built on strong primary healthcare services, effective governance and leadership, adequate financing, reliable health information systems, and a well-trained and motivated health workforce [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Resilient health systems are better equipped to deliver high-quality healthcare services to all people, including those who are marginalised or living in poverty. This, in turn, investing in RHS is essential for achieving UHC, promoting health equity, and building more sustainable and equitable societies. On the contrary, lack of healthcare access, skilled health workforces, and uneven distribution of health facilities and health workers [ 32 , 33 , 35 , 43 ] were the challenges to achieving health sector goals.

Lack of access, non-responsive and inequitable healthcare services were the challenges to achieve UHC and health security [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Such challenges can be solved by primary health care approach which is an effective strategy to provide accessible, acceptable, equitable and affordable health services to achieve UHC [ 82 , 83 ]. Community-based and differentiated service delivery models are also important platforms for improving healthcare delivery, access, outcomes, and to meet the specific needs and preferences of different groups of patients [ 84 , 85 ]. Community-based service delivery model can bring healthcare services closer to where people live and work, and overcome barriers to healthcare access such as transportation, distance, and cost [ 84 ]. This service delivery model has also the potential to facilitate a more effective response during healthcare crises by minimising top-down approaches and maximising bottom-up strategies through empowering local communities to take ownership of their health and wellbeing [ 86 ]. Additionally, differentiated service delivery model can meet the specific needs and preferences of different groups of patients. For example, providing family planning services within HIV clinics helps women living with HIV to access both services at the same time [ 85 ]. Similarly, considering a health system away from a one-size-fits-all approach to healthcare delivery is essential in meeting the needs of diverse patient populations [ 87 ].

Lack of skilled and inadequate distribution of health workforces were another major obstacle to contain an outbreak and deaths attributed to delays in treatment [ 35 , 43 ]. Conducting integrated supportive supervision, maintenance of human resource information systems, and national task shifting policy are important strategies that can help to address critical health workforce gaps and maldistribution [ 42 , 44 ]. Healthcare workers' pre-service and in-service training opportunities are indeed key to providing quality care. Healthcare workers who receive adequate pre-service and in-service training are better equipped to provide quality care to patients, and also to adapt to new challenges and changing healthcare needs over time [ 88 ]. Training in disaster preparedness and offering rewarding packages can also play an essential role in enhancing the willingness of healthcare workers to participate in disaster management [ 45 ]. For instance, Kenya's Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program (FELTP) has played a significant role in strengthening the capacity of healthcare workers to detect, document, respond, and report unusual health events [ 89 ]. In addition, monitoring frontline health levels is an essential part of preparedness against public health emergencies. This can involve monitoring healthcare facility capacities and the overall preparedness of the healthcare system to respond to an emergency [ 46 ].

Poor infrastructure, absence of emergency stockpiles, inadequate logistics, and shortages of medical supplies can be potential obstacles to achieving UHC during health emergencies [ 30 , 35 , 57 , 58 ]. A strong public health infrastructure can help to ensure that healthcare resources are distributed equitably, based on need rather than ability to pay. This is particularly important during a pandemic, when resources may be scarce and demand for healthcare services is high [ 90 ]. Integrating pharmaceutical supply chain activities with modern technologies and establishing strong relationships between manufacturers, distributors, prescribers, and insurance organizations can help ensure that essential supplies and logistics are available promptly [ 91 ]. Efficient procurement and an effective supply chain management system are essential components of a well-functioning healthcare system. They can help ensure that essential medicines, medical supplies, and equipment are available where and when they are needed, which is critical to achieving UHC and providing quality healthcare services to all individuals, regardless of their ability to pay [ 92 ].

The main challenges for universal financial protection were inadequate healthcare funds [ 35 ]. Context specific health financing mechanisms are essential to provide strong and sustainable health financing and move towards UHC [ 44 , 93 ]. Additionally, cross-subsidisation from rich to poor and low-risk to high-risk groups provide universal access for the entire population [ 94 ]. Similarly, reducing of health systems reliance on OOP payments and maximising risk pools were supportive to achieving UHC [ 60 ]. Universal health coverage can play a significant role in improving human security by providing financial protection against the cost of healthcare. In many countries, people face significant financial barriers to accessing healthcare services, and as a result, they may be forced to forgo necessary care or incur significant debt to pay for it. The example of Thailand is a good illustration of the potential benefits of UHC. Thailand implemented a comprehensive UHC program in the early 2000s, which provided coverage for all citizens and legal residents. Over the course of a decade, this program helped to reduce the annual impoverishment rate due to medical costs from 2.71% to 0.49% [ 61 ].

Poor leadership and absence of clear government policy led to fragmentation and poor health system response [ 35 , 66 ]. It is essential to involve a diverse range of stakeholders in pandemic preparedness and response efforts to ensure that a comprehensive and effective response is implemented. Collaborative efforts that include input from various stakeholders are more likely to lead to successful outcomes in mitigating the impact of a pandemic [ 73 , 95 ]. Good leadership is essential for effective outbreak response because it helps to coordinate and guide the efforts of different stakeholders, including health workers, community leaders, and government officials. A strong leader can help to build trust and confidence among the community, mobilise resources, and ensure that everyone is working together towards a common goal [ 54 ]. Health systems governance is essential for creating RHS that can respond to emerging health challenges, such as pandemics, as well as ongoing health concerns. By building strong partnerships and accountability mechanisms, health systems can better address the needs of individuals and communities, and improve overall health outcomes [ 48 ]. Cultivating bottom-up and top-down forms of accountability is also important to improve the quality and coverage of health services [ 96 ].

This study will provide an insight on RHS framework for achieving UHC and health security with an integrated and multi-sectoral approach that considers the health system building blocks and contextual factors. The limitations of this review include that the study did not quantitatively estimate the extent of resilient health system for UHC and health security. This is because we used articles based on various quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. In addition, we used the Rees et al. appraisal instrument as a guiding framework for the eligibility criteria [ 25 ]. The Rees specifies some methodological criteria for diverse types of studies but does not have a cut-off point for excluding studies.

This review provides evidence of the successes and challenges of RHS and its impact on achieving UHC globally. The review will also give an insight into the key determinants of RHS to achieve long term health sector goals. It will raise health programmers’ awareness of the importance of RHS and initiate an idea for future discussion and arguments on the subject. The review will also help policymakers and government officials to revise and update their strategic plans and policy directions. This review will also assist policy makers in introducing accountability within public institutions to provide more inclusive and equitable health services without excluding any population groups to achieve UHC. This review will help policymakers to formulate an agreed core set of global and national indicators to improve their health systems performance. This review will also help future researchers as baseline information.