Archer Library

Quantitative research: literature review .

- Archer Library This link opens in a new window

- Research Resources handout This link opens in a new window

- Locating Books

- Library eBook Collections This link opens in a new window

- A to Z Database List This link opens in a new window

- Research & Statistics

- Literature Review Resources

- Citations & Reference

Exploring the literature review

Literature review model: 6 steps.

Adapted from The Literature Review , Machi & McEvoy (2009, p. 13).

Your Literature Review

Step 2: search, boolean search strategies, search limiters, ★ ebsco & google drive.

1. Select a Topic

"All research begins with curiosity" (Machi & McEvoy, 2009, p. 14)

Selection of a topic, and fully defined research interest and question, is supervised (and approved) by your professor. Tips for crafting your topic include:

- Be specific. Take time to define your interest.

- Topic Focus. Fully describe and sufficiently narrow the focus for research.

- Academic Discipline. Learn more about your area of research & refine the scope.

- Avoid Bias. Be aware of bias that you (as a researcher) may have.

- Document your research. Use Google Docs to track your research process.

- Research apps. Consider using Evernote or Zotero to track your research.

Consider Purpose

What will your topic and research address?

In The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students , Ridley presents that literature reviews serve several purposes (2008, p. 16-17). Included are the following points:

- Historical background for the research;

- Overview of current field provided by "contemporary debates, issues, and questions;"

- Theories and concepts related to your research;

- Introduce "relevant terminology" - or academic language - being used it the field;

- Connect to existing research - does your work "extend or challenge [this] or address a gap;"

- Provide "supporting evidence for a practical problem or issue" that your research addresses.

★ Schedule a research appointment

At this point in your literature review, take time to meet with a librarian. Why? Understanding the subject terminology used in databases can be challenging. Archer Librarians can help you structure a search, preparing you for step two. How? Contact a librarian directly or use the online form to schedule an appointment. Details are provided in the adjacent Schedule an Appointment box.

2. Search the Literature

Collect & Select Data: Preview, select, and organize

Archer Library is your go-to resource for this step in your literature review process. The literature search will include books and ebooks, scholarly and practitioner journals, theses and dissertations, and indexes. You may also choose to include web sites, blogs, open access resources, and newspapers. This library guide provides access to resources needed to complete a literature review.

Books & eBooks: Archer Library & OhioLINK

| Books | |

Databases: Scholarly & Practitioner Journals

Review the Library Databases tab on this library guide, it provides links to recommended databases for Education & Psychology, Business, and General & Social Sciences.

Expand your journal search; a complete listing of available AU Library and OhioLINK databases is available on the Databases A to Z list . Search the database by subject, type, name, or do use the search box for a general title search. The A to Z list also includes open access resources and select internet sites.

Databases: Theses & Dissertations

Review the Library Databases tab on this guide, it includes Theses & Dissertation resources. AU library also has AU student authored theses and dissertations available in print, search the library catalog for these titles.

Did you know? If you are looking for particular chapters within a dissertation that is not fully available online, it is possible to submit an ILL article request . Do this instead of requesting the entire dissertation.

Newspapers: Databases & Internet

Consider current literature in your academic field. AU Library's database collection includes The Chronicle of Higher Education and The Wall Street Journal . The Internet Resources tab in this guide provides links to newspapers and online journals such as Inside Higher Ed , COABE Journal , and Education Week .

The Chronicle of Higher Education has the nation’s largest newsroom dedicated to covering colleges and universities. Source of news, information, and jobs for college and university faculty members and administrators

The Chronicle features complete contents of the latest print issue; daily news and advice columns; current job listings; archive of previously published content; discussion forums; and career-building tools such as online CV management and salary databases. Dates covered: 1970-present.

Offers in-depth coverage of national and international business and finance as well as first-rate coverage of hard news--all from America's premier financial newspaper. Covers complete bibliographic information and also subjects, companies, people, products, and geographic areas.

Comprehensive coverage back to 1984 is available from the world's leading financial newspaper through the ProQuest database.

Newspaper Source provides cover-to-cover full text for hundreds of national (U.S.), international and regional newspapers. In addition, it offers television and radio news transcripts from major networks.

Provides complete television and radio news transcripts from CBS News, CNN, CNN International, FOX News, and more.

Search Strategies & Boolean Operators

There are three basic boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT.

Used with your search terms, boolean operators will either expand or limit results. What purpose do they serve? They help to define the relationship between your search terms. For example, using the operator AND will combine the terms expanding the search. When searching some databases, and Google, the operator AND may be implied.

Overview of boolean terms

| Search results will contain of the terms. | Search results will contain of the search terms. | Search results the specified search term. |

| Search for ; you will find items that contain terms. | Search for ; you will find items that contain . | Search for online education: you will find items that contain . |

| connects terms, limits the search, and will reduce the number of results returned. | redefines connection of the terms, expands the search, and increases the number of results returned. | excludes results from the search term and reduces the number of results. |

|

Adult learning online education: |

Adult learning online education: |

Adult learning online education: |

About the example: Boolean searches were conducted on November 4, 2019; result numbers may vary at a later date. No additional database limiters were set to further narrow search returns.

Database Search Limiters

Database strategies for targeted search results.

Most databases include limiters, or additional parameters, you may use to strategically focus search results. EBSCO databases, such as Education Research Complete & Academic Search Complete provide options to:

- Limit results to full text;

- Limit results to scholarly journals, and reference available;

- Select results source type to journals, magazines, conference papers, reviews, and newspapers

- Publication date

Keep in mind that these tools are defined as limiters for a reason; adding them to a search will limit the number of results returned. This can be a double-edged sword. How?

- If limiting results to full-text only, you may miss an important piece of research that could change the direction of your research. Interlibrary loan is available to students, free of charge. Request articles that are not available in full-text; they will be sent to you via email.

- If narrowing publication date, you may eliminate significant historical - or recent - research conducted on your topic.

- Limiting resource type to a specific type of material may cause bias in the research results.

Use limiters with care. When starting a search, consider opting out of limiters until the initial literature screening is complete. The second or third time through your research may be the ideal time to focus on specific time periods or material (scholarly vs newspaper).

★ Truncating Search Terms

Expanding your search term at the root.

Truncating is often referred to as 'wildcard' searching. Databases may have their own specific wildcard elements however, the most commonly used are the asterisk (*) or question mark (?). When used within your search. they will expand returned results.

Asterisk (*) Wildcard

Using the asterisk wildcard will return varied spellings of the truncated word. In the following example, the search term education was truncated after the letter "t."

| Original Search | |

| adult education | adult educat* |

| Results included: educate, education, educator, educators'/educators, educating, & educational |

Explore these database help pages for additional information on crafting search terms.

- EBSCO Connect: Basic Searching with EBSCO

- EBSCO Connect: Searching with Boolean Operators

- EBSCO Connect: Searching with Wildcards and Truncation Symbols

- ProQuest Help: Search Tips

- ERIC: How does ERIC search work?

★ EBSCO Databases & Google Drive

Tips for saving research directly to Google drive.

Researching in an EBSCO database?

It is possible to save articles (PDF and HTML) and abstracts in EBSCOhost databases directly to Google drive. Select the Google Drive icon, authenticate using a Google account, and an EBSCO folder will be created in your account. This is a great option for managing your research. If documenting your research in a Google Doc, consider linking the information to actual articles saved in drive.

EBSCO Databases & Google Drive

EBSCOHost Databases & Google Drive: Managing your Research

This video features an overview of how to use Google Drive with EBSCO databases to help manage your research. It presents information for connecting an active Google account to EBSCO and steps needed to provide permission for EBSCO to manage a folder in Drive.

About the Video: Closed captioning is available, select CC from the video menu. If you need to review a specific area on the video, view on YouTube and expand the video description for access to topic time stamps. A video transcript is provided below.

- EBSCOhost Databases & Google Scholar

Defining Literature Review

What is a literature review.

A definition from the Online Dictionary for Library and Information Sciences .

A literature review is "a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works" (Reitz, 2014).

A systemic review is "a literature review focused on a specific research question, which uses explicit methods to minimize bias in the identification, appraisal, selection, and synthesis of all the high-quality evidence pertinent to the question" (Reitz, 2014).

Recommended Reading

About this page

EBSCO Connect [Discovery and Search]. (2022). Searching with boolean operators. Retrieved May, 3, 2022 from https://connect.ebsco.com/s/?language=en_US

EBSCO Connect [Discover and Search]. (2022). Searching with wildcards and truncation symbols. Retrieved May 3, 2022; https://connect.ebsco.com/s/?language=en_US

Machi, L.A. & McEvoy, B.T. (2009). The literature review . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press:

Reitz, J.M. (2014). Online dictionary for library and information science. ABC-CLIO, Libraries Unlimited . Retrieved from https://www.abc-clio.com/ODLIS/odlis_A.aspx

Ridley, D. (2008). The literature review: A step-by-step guide for students . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Archer Librarians

Schedule an appointment.

Contact a librarian directly (email), or submit a request form. If you have worked with someone before, you can request them on the form.

- ★ Archer Library Help • Online Reqest Form

- Carrie Halquist • Reference & Instruction

- Jessica Byers • Reference & Curation

- Don Reams • Corrections Education & Reference

- Diane Schrecker • Education & Head of the IRC

- Tanaya Silcox • Technical Services & Business

- Sarah Thomas • Acquisitions & ATS Librarian

- << Previous: Research & Statistics

- Next: Literature Review Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 11:19 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ashland.edu/quantitative

Archer Library • Ashland University © Copyright 2023. An Equal Opportunity/Equal Access Institution.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write Review of Related Literature (RRL) in Research

A review of related literature (a.k.a RRL in research) is a comprehensive review of the existing literature pertaining to a specific topic or research question. An effective review provides the reader with an organized analysis and synthesis of the existing knowledge about a subject. With the increasing amount of new information being disseminated every day, conducting a review of related literature is becoming more difficult and the purpose of review of related literature is clearer than ever.

All new knowledge is necessarily based on previously known information, and every new scientific study must be conducted and reported in the context of previous studies. This makes a review of related literature essential for research, and although it may be tedious work at times , most researchers will complete many such reviews of varying depths during their career. So, why exactly is a review of related literature important?

Table of Contents

Why a review of related literature in research is important

Before thinking how to do reviews of related literature , it is necessary to understand its importance. Although the purpose of a review of related literature varies depending on the discipline and how it will be used, its importance is never in question. Here are some ways in which a review can be crucial.

- Identify gaps in the knowledge – This is the primary purpose of a review of related literature (often called RRL in research ). To create new knowledge, you must first determine what knowledge may be missing. This also helps to identify the scope of your study.

- Avoid duplication of research efforts – Not only will a review of related literature indicate gaps in the existing research, but it will also lead you away from duplicating research that has already been done and thus save precious resources.

- Provide an overview of disparate and interdisciplinary research areas – Researchers cannot possibly know everything related to their disciplines. Therefore, it is very helpful to have access to a review of related literature already written and published.

- Highlight researcher’s familiarity with their topic 1 – A strong review of related literature in a study strengthens readers’ confidence in that study and that researcher.

Tips on how to write a review of related literature in research

Given that you will probably need to produce a number of these at some point, here are a few general tips on how to write an effective review of related literature 2 .

- Define your topic, audience, and purpose: You will be spending a lot of time with this review, so choose a topic that is interesting to you. While deciding what to write in a review of related literature , think about who you expect to read the review – researchers in your discipline, other scientists, the general public – and tailor the language to the audience. Also, think about the purpose of your review of related literature .

- Conduct a comprehensive literature search: While writing your review of related literature , emphasize more recent works but don’t forget to include some older publications as well. Cast a wide net, as you may find some interesting and relevant literature in unexpected databases or library corners. Don’t forget to search for recent conference papers.

- Review the identified articles and take notes: It is a good idea to take notes in a way such that individual items in your notes can be moved around when you organize them. For example, index cards are great tools for this. Write each individual idea on a separate card along with the source. The cards can then be easily grouped and organized.

- Determine how to organize your review: A review of related literature should not be merely a listing of descriptions. It should be organized by some criterion, such as chronologically or thematically.

- Be critical and objective: Don’t just report the findings of other studies in your review of related literature . Challenge the methodology, find errors in the analysis, question the conclusions. Use what you find to improve your research. However, do not insert your opinions into the review of related literature. Remain objective and open-minded.

- Structure your review logically: Guide the reader through the information. The structure will depend on the function of the review of related literature. Creating an outline prior to writing the RRL in research is a good way to ensure the presented information flows well.

As you read more extensively in your discipline, you will notice that the review of related literature appears in various forms in different places. For example, when you read an article about an experimental study, you will typically see a literature review or a RRL in research , in the introduction that includes brief descriptions of similar studies. In longer research studies and dissertations, especially in the social sciences, the review of related literature will typically be a separate chapter and include more information on methodologies and theory building. In addition, stand-alone review articles will be published that are extremely useful to researchers.

The review of relevant literature or often abbreviated as, RRL in research , is an important communication tool that can be used in many forms for many purposes. It is a tool that all researchers should befriend.

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Writing Center. Literature Reviews. https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/literature-reviews/ [Accessed September 8, 2022]

- Pautasso M. Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013, 9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003149.

Q: Is research complete without a review of related literature?

A research project is usually considered incomplete without a proper review of related literature. The review of related literature is a crucial component of any research project as it provides context for the research question, identifies gaps in existing literature, and ensures novelty by avoiding duplication. It also helps inform research design and supports arguments, highlights the significance of a study, and demonstrates your knowledge an expertise.

Q: What is difference between RRL and RRS?

The key difference between an RRL and an RRS lies in their focus and scope. An RRL or review of related literature examines a broad range of literature, including theoretical frameworks, concepts, and empirical studies, to establish the context and significance of the research topic. On the other hand, an RRS or review of research studies specifically focuses on analyzing and summarizing previous research studies within a specific research domain to gain insights into methodologies, findings, and gaps in the existing body of knowledge. While there may be some overlap between the two, they serve distinct purposes and cover different aspects of the research process.

Q: Does review of related literature improve accuracy and validity of research?

Yes, a comprehensive review of related literature (RRL) plays a vital role in improving the accuracy and validity of research. It helps authors gain a deeper understanding and offers different perspectives on the research topic. RRL can help you identify research gaps, dictate the selection of appropriate research methodologies, enhance theoretical frameworks, avoid biases and errors, and even provide support for research design and interpretation. By building upon and critically engaging with existing related literature, researchers can ensure their work is rigorous, reliable, and contributes meaningfully to their field of study.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

How Does R Discovery’s Interplatform Capability Enhance Research Accessibility

University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Blackboard Learn

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

- University of Arkansas

Literature Reviews

- Qualitative or Quantitative?

- Getting Started

- Finding articles

- Primary sources? Peer-reviewed?

- Review Articles/ Annual Reviews...?

- Books, ebooks, dissertations, book reviews

Qualitative researchers TEND to:

Researchers using qualitative methods tend to:

- t hink that social sciences cannot be well-studied with the same methods as natural or physical sciences

- feel that human behavior is context-specific; therefore, behavior must be studied holistically, in situ, rather than being manipulated

- employ an 'insider's' perspective; research tends to be personal and thereby more subjective.

- do interviews, focus groups, field research, case studies, and conversational or content analysis.

Image from https://www.editage.com/insights/qualitative-quantitative-or-mixed-methods-a-quick-guide-to-choose-the-right-design-for-your-research?refer-type=infographics

Qualitative Research (an operational definition)

Qualitative Research: an operational description

Purpose : explain; gain insight and understanding of phenomena through intensive collection and study of narrative data

Approach: inductive; value-laden/subjective; holistic, process-oriented

Hypotheses: tentative, evolving; based on the particular study

Lit. Review: limited; may not be exhaustive

Setting: naturalistic, when and as much as possible

Sampling : for the purpose; not necessarily representative; for in-depth understanding

Measurement: narrative; ongoing

Design and Method: flexible, specified only generally; based on non-intervention, minimal disturbance, such as historical, ethnographic, or case studies

Data Collection: document collection, participant observation, informal interviews, field notes

Data Analysis: raw data is words/ ongoing; involves synthesis

Data Interpretation: tentative, reviewed on ongoing basis, speculative

- Qualitative research with more structure and less subjectivity

- Increased application of both strategies to the same study ("mixed methods")

- Evidence-based practice emphasized in more fields (nursing, social work, education, and others).

Some Other Guidelines

- Guide for formatting Graphs and Tables

- Critical Appraisal Checklist for an Article On Qualitative Research

Quantitative researchers TEND to:

Researchers using quantitative methods tend to:

- think that both natural and social sciences strive to explain phenomena with confirmable theories derived from testable assumptions

- attempt to reduce social reality to variables, in the same way as with physical reality

- try to tightly control the variable(s) in question to see how the others are influenced.

- Do experiments, have control groups, use blind or double-blind studies; use measures or instruments.

Quantitative Research (an operational definition)

Quantitative research: an operational description

Purpose: explain, predict or control phenomena through focused collection and analysis of numberical data

Approach: deductive; tries to be value-free/has objectives/ is outcome-oriented

Hypotheses : Specific, testable, and stated prior to study

Lit. Review: extensive; may significantly influence a particular study

Setting: controlled to the degree possible

Sampling: uses largest manageable random/randomized sample, to allow generalization of results to larger populations

Measurement: standardized, numberical; "at the end"

Design and Method: Strongly structured, specified in detail in advance; involves intervention, manipulation and control groups; descriptive, correlational, experimental

Data Collection: via instruments, surveys, experiments, semi-structured formal interviews, tests or questionnaires

Data Analysis: raw data is numbers; at end of study, usually statistical

Data Interpretation: formulated at end of study; stated as a degree of certainty

This page on qualitative and quantitative research has been adapted and expanded from a handout by Suzy Westenkirchner. Used with permission.

Images from https://www.editage.com/insights/qualitative-quantitative-or-mixed-methods-a-quick-guide-to-choose-the-right-design-for-your-research?refer-type=infographics.

- << Previous: Books, ebooks, dissertations, book reviews

- Last Updated: Aug 20, 2024 10:19 AM

- URL: https://uark.libguides.com/litreview

- See us on Instagram

- Follow us on Twitter

- Phone: 479-575-4104

Research Process :: Step by Step

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Popular Databases

- Evaluate Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

- Research Process

- Selecting Your Topic

- Identifying Keywords

- Gathering Background Info

- Evaluating Sources

Organize the literature review into sections that present themes or identify trends, including relevant theory. You are not trying to list all the material published, but to synthesize and evaluate it according to the guiding concept of your thesis or research question.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. Occasionally you will be asked to write one as a separate assignment, but more often it is part of the introduction to an essay, research report, or thesis. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries

A literature review must do these things:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you are developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Ask yourself questions like these:

- What is the specific thesis, problem, or research question that my literature review helps to define?

- What type of literature review am I conducting? Am I looking at issues of theory? methodology? policy? quantitative research (e.g. on the effectiveness of a new procedure)? qualitative research (e.g., studies of loneliness among migrant workers)?

- What is the scope of my literature review? What types of publications am I using (e.g., journals, books, government documents, popular media)? What discipline am I working in (e.g., nursing psychology, sociology, medicine)?

- How good was my information seeking? Has my search been wide enough to ensure I've found all the relevant material? Has it been narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material? Is the number of sources I've used appropriate for the length of my paper?

- Have I critically analyzed the literature I use? Do I follow through a set of concepts and questions, comparing items to each other in the ways they deal with them? Instead of just listing and summarizing items, do I assess them, discussing strengths and weaknesses?

- Have I cited and discussed studies contrary to my perspective?

- Will the reader find my literature review relevant, appropriate, and useful?

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- Has the author formulated a problem/issue?

- Is it clearly defined? Is its significance (scope, severity, relevance) clearly established?

- Could the problem have been approached more effectively from another perspective?

- What is the author's research orientation (e.g., interpretive, critical science, combination)?

- What is the author's theoretical framework (e.g., psychological, developmental, feminist)?

- What is the relationship between the theoretical and research perspectives?

- Has the author evaluated the literature relevant to the problem/issue? Does the author include literature taking positions she or he does not agree with?

- In a research study, how good are the basic components of the study design (e.g., population, intervention, outcome)? How accurate and valid are the measurements? Is the analysis of the data accurate and relevant to the research question? Are the conclusions validly based upon the data and analysis?

- In material written for a popular readership, does the author use appeals to emotion, one-sided examples, or rhetorically-charged language and tone? Is there an objective basis to the reasoning, or is the author merely "proving" what he or she already believes?

- How does the author structure the argument? Can you "deconstruct" the flow of the argument to see whether or where it breaks down logically (e.g., in establishing cause-effect relationships)?

- In what ways does this book or article contribute to our understanding of the problem under study, and in what ways is it useful for practice? What are the strengths and limitations?

- How does this book or article relate to the specific thesis or question I am developing?

Text written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre, University of Toronto

http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Step 5: Cite Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 4:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/researchprocess

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

| Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or mode | Seeks to identify most significant items in the field | No formal quality assessment. Attempts to evaluate according to contribution | Typically narrative, perhaps conceptual or chronological | Significant component: seeks to identify conceptual contribution to embody existing or derive new theory | |

| Generic term: published materials that provide examination of recent or current literature. Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness. May include research findings | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Mapping review/ systematic map | Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints | No formal quality assessment | May be graphical and tabular | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. May identify need for primary or secondary research |

| Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching. May use funnel plot to assess completeness | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/ exclusion and/or sensitivity analyses | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | Numerical analysis of measures of effect assuming absence of heterogeneity | |

| Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies | Requires either very sensitive search to retrieve all studies or separately conceived quantitative and qualitative strategies | Requires either a generic appraisal instrument or separate appraisal processes with corresponding checklists | Typically both components will be presented as narrative and in tables. May also employ graphical means of integrating quantitative and qualitative studies | Analysis may characterise both literatures and look for correlations between characteristics or use gap analysis to identify aspects absent in one literature but missing in the other | |

| Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics | May or may not include comprehensive searching (depends whether systematic overview or not) | May or may not include quality assessment (depends whether systematic overview or not) | Synthesis depends on whether systematic or not. Typically narrative but may include tabular features | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies | May employ selective or purposive sampling | Quality assessment typically used to mediate messages not for inclusion/exclusion | Qualitative, narrative synthesis | Thematic analysis, may include conceptual models | |

| Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research | Completeness of searching determined by time constraints | Time-limited formal quality assessment | Typically narrative and tabular | Quantities of literature and overall quality/direction of effect of literature | |

| Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research) | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints. May include research in progress | No formal quality assessment | Typically tabular with some narrative commentary | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. Attempts to specify a viable review | |

| Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives | Aims for comprehensive searching of current literature | No formal quality assessment | Typically narrative, may have tabular accompaniment | Current state of knowledge and priorities for future investigation and research | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; uncertainty around findings, recommendations for future research | |

| Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis’ | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Minimal narrative, tabular summary of studies | What is known; recommendations for practice. Limitations | |

| Attempt to include elements of systematic review process while stopping short of systematic review. Typically conducted as postgraduate student assignment | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; uncertainty around findings; limitations of methodology | |

| Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results | Identification of component reviews, but no search for primary studies | Quality assessment of studies within component reviews and/or of reviews themselves | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; recommendations for future research |

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 23, 2024 3:40 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Literature Review

What exactly is a literature review.

- Critical Exploration and Synthesis: It involves a thorough and critical examination of existing research, going beyond simple summaries to synthesize information.

- Reorganizing Key Information: Involves structuring and categorizing the main ideas and findings from various sources.

- Offering Fresh Interpretations: Provides new perspectives or insights into the research topic.

- Merging New and Established Insights: Integrates both recent findings and well-established knowledge in the field.

- Analyzing Intellectual Trajectories: Examines the evolution and debates within a specific field over time.

- Contextualizing Current Research: Places recent research within the broader academic landscape, showing its relevance and relation to existing knowledge.

- Detailed Overview of Sources: Gives a comprehensive summary of relevant books, articles, and other scholarly materials.

- Highlighting Significance: Emphasizes the importance of various research works to the specific topic of study.

How do Literature Reviews Differ from Academic Research Papers?

- Focus on Existing Arguments: Literature reviews summarize and synthesize existing research, unlike research papers that present new arguments.

- Secondary vs. Primary Research: Literature reviews are based on secondary sources, while research papers often include primary research.

- Foundational Element vs. Main Content: In research papers, literature reviews are usually a part of the background, not the main focus.

- Lack of Original Contributions: Literature reviews do not introduce new theories or findings, which is a key component of research papers.

Purpose of Literature Reviews

- Drawing from Diverse Fields: Literature reviews incorporate findings from various fields like health, education, psychology, business, and more.

- Prioritizing High-Quality Studies: They emphasize original, high-quality research for accuracy and objectivity.

- Serving as Comprehensive Guides: Offer quick, in-depth insights for understanding a subject thoroughly.

- Foundational Steps in Research: Act as a crucial first step in conducting new research by summarizing existing knowledge.

- Providing Current Knowledge for Professionals: Keep professionals updated with the latest findings in their fields.

- Demonstrating Academic Expertise: In academia, they showcase the writer’s deep understanding and contribute to the background of research papers.

- Essential for Scholarly Research: A deep understanding of literature is vital for conducting and contextualizing scholarly research.

A Literature Review is Not About:

- Merely Summarizing Sources: It’s not just a compilation of summaries of various research works.

- Ignoring Contradictions: It does not overlook conflicting evidence or viewpoints in the literature.

- Being Unstructured: It’s not a random collection of information without a clear organizing principle.

- Avoiding Critical Analysis: It doesn’t merely present information without critically evaluating its relevance and credibility.

- Focusing Solely on Older Research: It’s not limited to outdated or historical literature, ignoring recent developments.

- Isolating Research: It doesn’t treat each source in isolation but integrates them into a cohesive narrative.

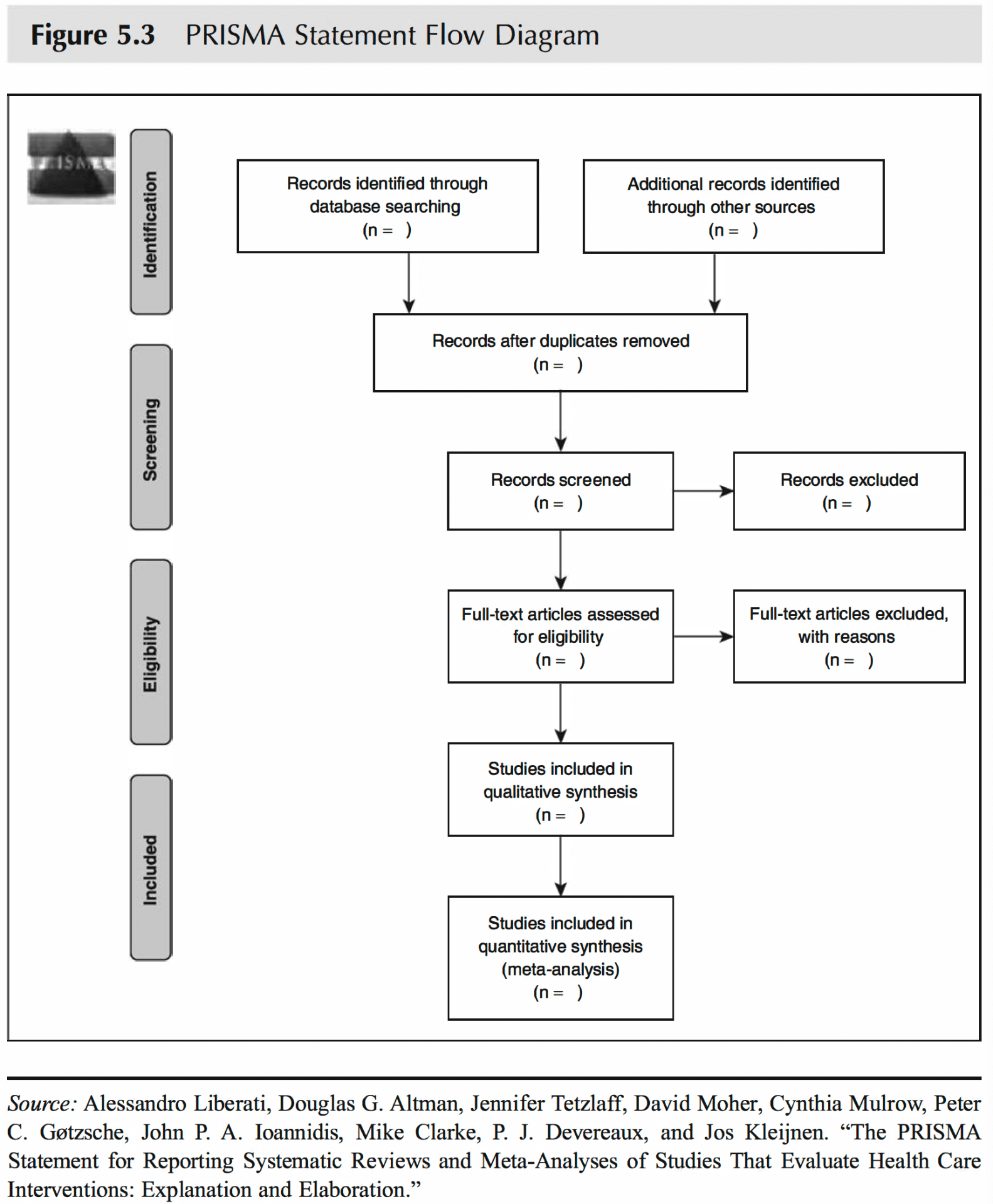

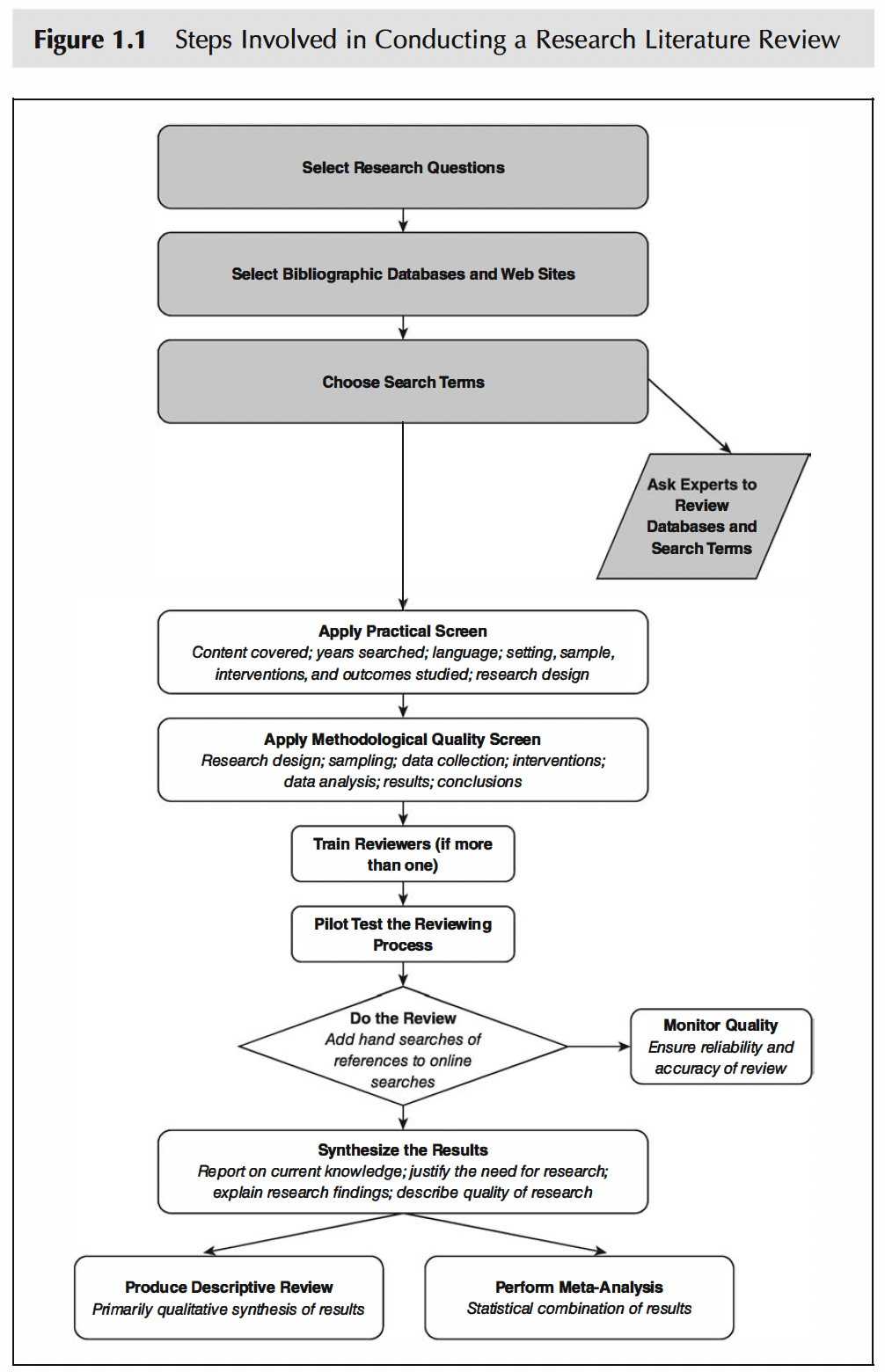

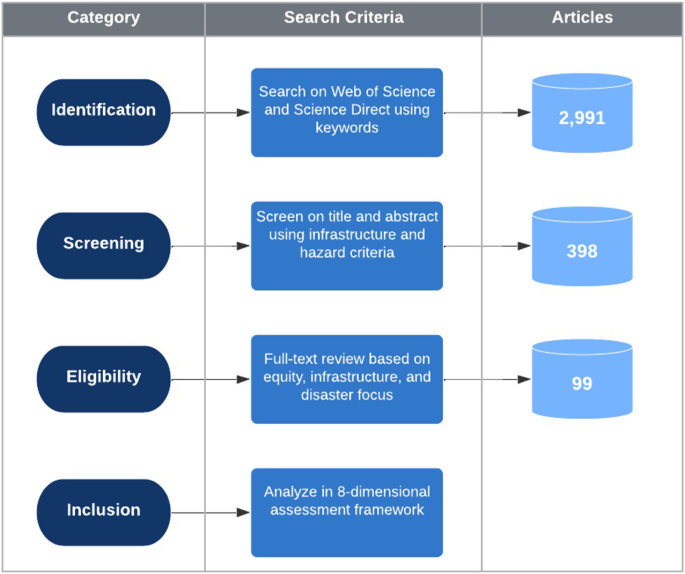

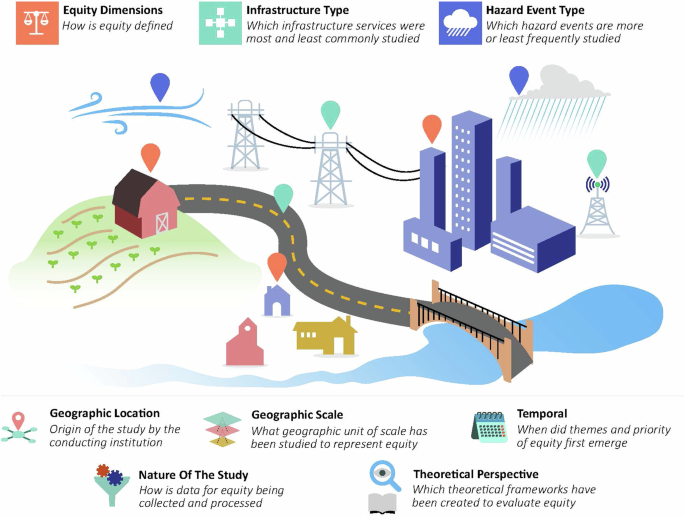

Steps Involved in Conducting a Research Literature Review (Fink, 2019)

1. choose a clear research question., 2. use online databases and other resources to find articles and books relevant to your question..

- Google Scholar

- OSU Library

- ERIC. Index to journal articles on educational research and practice.

- PsycINFO . Citations and abstracts for articles in 1,300 professional journals, conference proceedings, books, reports, and dissertations in psychology and related disciplines.

- PubMed . This search system provides access to the PubMed database of bibliographic information, which is drawn primarily from MEDLINE, which indexes articles from about 3,900 journals in the life sciences (e.g., health, medicine, biology).

- Social Sciences Citation Index . A multidisciplinary database covering the journal literature of the social sciences, indexing more than 1,725 journals across 50 social sciences disciplines.

3. Decide on Search Terms.

- Pick words and phrases based on your research question to find suitable materials

- You can start by finding models for your literature review, and search for existing reviews in your field, using “review” and your keywords. This helps identify themes and organizational methods.

- Narrowing your topic is crucial due to the vast amount of literature available. Focusing on a specific aspect makes it easier to manage the number of sources you need to review, as it’s unlikely you’ll need to cover everything in the field.

- Use AND to retrieve a set of citations in which each citation contains all search terms.

- Use OR to retrieve citations that contain one of the specified terms.

- Use NOT to exclude terms from your search.

- Be careful when using NOT because you may inadvertently eliminate important articles. In Example 3, articles about preschoolers and academic achievement are eliminated, but so are studies that include preschoolers as part of a discussion of academic achievement and all age groups.

4. Filter out articles that don’t meet criteria like language, type, publication date, and funding source.

- Publication language Example. Include only studies in English.

- Journal Example. Include all education journals. Exclude all medical journals.

- Author Example. Include all articles by Andrew Hayes.

- Setting Example. Include all studies that take place in family settings. Exclude all studies that take place in the school setting.

- Participants or subjects Example. Include children that are younger than 6 years old.

- Program/intervention Example. Include all programs that are teacher-led. Exclude all programs that are learner-initiated.

- Research design Example. Include only longitudinal studies. Exclude cross-sectional studies.

- Sampling Example. Include only studies that rely on randomly selected participants.

- Date of publication Example. Include only studies published from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2023.

- Date of data collection Example. Include only studies that collected data from 2010 through 2023. Exclude studies that do not give dates of data collection.

- Duration of data collection Example. Include only studies that collect data for 12 months or longer.

5. Evaluate the methodological quality of the articles, including research design, sampling, data collection, interventions, data analysis, results, and conclusions.

- Maturation: Changes in individuals due to natural development may impact study results, such as intellectual or emotional growth in long-term studies.

- Selection: The method of choosing and assigning participants to groups can introduce bias; random selection minimizes this.

- History: External historical events occurring simultaneously with the study can bias results, making it hard to isolate the study’s effects.

- Instrumentation: Reliable data collection tools are essential to ensure accurate findings, especially in pretest-posttest designs.

- Statistical Regression: Selection based on extreme initial measures can lead to misleading results due to regression towards the mean.

- Attrition: Loss of participants during a study can bias results if those remaining differ significantly from those who dropped out.

- Reactive Effects of Testing: Pre-intervention measures can sensitize participants to the study’s aims, affecting outcomes.

- Interactive Effects of Selection: Unique combinations of intervention programs and participants can limit the generalizability of findings.

- Reactive Effects of Innovation: Artificial experimental environments can lead to uncharacteristic behavior among participants.

- Multiple-Program Interference: Difficulty in isolating an intervention’s effects due to participants’ involvement in other activities or programs.

- Simple Random Sampling : Every individual has an equal chance of being selected, making this method relatively unbiased.

- Systematic Sampling : Selection is made at regular intervals from a list, such as every sixth name from a list of 3,000 to obtain a sample of 500.

- Stratified Sampling : The population is divided into subgroups, and random samples are then taken from each subgroup.

- Cluster Sampling : Natural groups (like schools or cities) are used as batches for random selection, both at the group and individual levels.

- Convenience Samples : Selection probability is unknown; these samples are easy to obtain but may not be representative unless statistically validated.

- Study Power: The ability of a study to detect an effect, if present, is known as its power. Power analysis helps identify a sample size large enough to detect this effect.

- Test-Retest Reliability: High correlation between scores obtained at different times, indicating consistency over time.

- Equivalence/Alternate-Form Reliability: The degree to which two different assessments measure the same concept at the same difficulty level.

- Homogeneity: The extent to which all items or questions in a measure assess the same skill, characteristic, or quality.

- Interrater Reliability: Degree of agreement among different individuals assessing the same item or concept.

- Content Validity: Measures how thoroughly and appropriately a tool assesses the skills or characteristics it’s supposed to measure. Face Validity: Assesses whether a measure appears effective at first glance in terms of language use and comprehensiveness. Criterion Validity: Includes predictive validity (forecasting future performance) and concurrent validity (agreement with already valid measures). Construct Validity: Experimentally established to show that a measure effectively differentiates between people with and without certain characteristics.

- Relies on factors like the scale (categorical, ordinal, numerical) of independent and dependent variables, the count of these variables, and whether the data’s quality and characteristics align with the chosen statistical method’s assumptions.

6. Use a standard form for data extraction, train reviewers if needed, and ensure quality.

7. interpret the results, using your experience and the literature’s quality and content. for a more detailed analysis, a meta-analysis can be conducted using statistical methods to combine study results., 8. produce a descriptive review or perform a meta-analysis..

- Example: Bryman, A. (2007). Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Studies in higher education, 32(6), 693-710.

- Clarify the objectives of the analysis.

- Set explicit criteria for including and excluding studies.

- Describe in detail the methods used to search the literature.

- Search the literature using a standardized protocol for including and excluding studies.

- Use a standardized protocol to collect (“abstract”) data from each study regarding study purposes, methods, and effects (outcomes).

- Describe in detail the statistical method for pooling results.

- Report results, conclusions, and limitations.

- Example: Yu, Z. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effect of virtual reality technology use in education. Interactive Learning Environments, 31 (8), 4956-4976.

- Essential and Multifunctional Bibliographic Software: Tools like EndNote, ProCite, BibTex, Bookeeper, Zotero, and Mendeley offer more than just digital storage for references; they enable saving and sharing search strategies, directly inserting references into reports and scholarly articles, and analyzing references by thematic content.

- Comprehensive Literature Reviews: Involve supplementing electronic searches with a review of references in identified literature, manual searches of references and journals, and consulting experts for both unpublished and published studies and reports.

- One of the most famous reporting checklists is the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials ( CONSORT ). CONSORT consists of a checklist and flow diagram. The checklist includes items that need to be addressed in the report.

References:

Bryman, A. (2007). Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Studies in higher education , 32 (6), 693-710.

Fink, A. (2019). Conducting research literature reviews: From the internet to paper . Sage publications.

Yu, Z. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effect of virtual reality technology use in education. Interactive Learning Environments, 31 (8), 4956-4976.

How to Operate Literature Review Through Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis Integration?

- Conference paper

- First Online: 05 May 2022

- Cite this conference paper

- Eduardo Amadeu Dutra Moresi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6058-3883 13 ,

- Isabel Pinho ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1714-8979 14 &

- António Pedro Costa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4644-5879 14

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems ((LNNS,volume 466))

Included in the following conference series:

- World Conference on Qualitative Research

539 Accesses

3 Citations

Usually, a literature review takes time and becomes a demanding step in any research project. The proposal presented in this article intends to structure this work in an organised and transparent way for all project participants and the structured elaboration of its report. Integrating qualitative and quantitative analysis provides opportunities to carry out a solid, practical, and in-depth literature review. The purpose of this article is to present a guide that explores the potentials of qualitative and quantitative analysis integration to develop a solid and replicable literature review. The paper proposes an integrative approach comprising six steps: 1) research design; 2) Data Collection for bibliometric analysis; 3) Search string refinement; 4) Bibliometric analysis; 5) qualitative analysis; and 6) report and dissemination of research results. These guidelines can facilitate the bibliographic analysis process and relevant article sample selection. Once the sample of publications is defined, it is possible to conduct a deep analysis through Content Analysis. Software tools, such as R Bibliometrix, VOSviewer, Gephi, yEd and webQDA, can be used for practical work during all collection, analysis, and reporting processes. From a large amount of data, selecting a sample of relevant literature is facilitated by interpreting bibliometric results. The specification of the methodology allows the replication and updating of the literature review in an interactive, systematic, and collaborative way giving a more transparent and organised approach to improving the literature review.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

On being ‘systematic’ in literature reviews

Literature Reviews: An Overview of Systematic, Integrated, and Scoping Reviews

Pritchard, A.: Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics? J. Doc. 25 (4), 348–349 (1969)

Google Scholar

Nalimov, V., Mulcjenko, B.: Measurement of Science: Study of the Development of Science as an Information Process. Foreign Technology Division, Washington DC (1971)

Hugar, J.G., Bachlapur, M.M., Gavisiddappa, A.: Research contribution of bibliometric studies as reflected in web of science from 2013 to 2017. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-journal), 1–13 (2019). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2319

Verma, M.K., Shukla, R.: Library herald-2008–2017: a bibliometric study. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-journal), 2–12 (2018). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1762

Pandita, R.: Annals of library and information studies (ALIS) journal: a bibliometric study (2002–2012). DESIDOC J. Libr. Inf. Technol. 33 (6), 493–497 (2013)

Article Google Scholar

Kannan, P., Thanuskodi, S.: Bibliometric analysis of library philosophy and practice: a study based on scopus database. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-journal), 1–13 (2019). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2300/

Marín-Marín, J.-A., Moreno-Guerrero, A.-J., Dúo-Terrón, P., López-Belmonte, J.: STEAM in education: a bibliometric analysis of performance and co-words in Web of Science. Int. J. STEM Educ. 8 (1) (2021). Article number 41

Khalife, M.A., Dunay, A., Illés, C.B.: Bibliometric analysis of articles on project management research. Periodica Polytechnica Soc. Manag. Sci. 29 (1), 70–83 (2021)

Pech, G., Delgado, C.: Screening the most highly cited papers in longitudinal bibliometric studies and systematic literature reviews of a research field or journal: widespread used metrics vs a percentile citation-based approach. J. Informet. 15 (3), 101161 (2021)

Das, D.: Journal of informetrics: a bibliometric study. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-journal), 1–15 (2021). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5495/

Schmidt, F.: Meta-analysis: a constantly evolving research integration tool. Organ. Res. Methods 11 (1), 96–113 (2008)

Zupic, I., Cater, T.: Bibliometric methods in management organisation. Organ. Res. Methods 18 (3), 429–472 (2014)

Noyons, E., Moed, H., Luwel, M.: Combining mapping and citation analysis for evaluative bibliometric purposes: a bibliometric study. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 50 , 115–131 (1999)

van Rann, A.: Measuring science. Capita selecta of current main issues. In: Moed, H., Glänzel, W., Schmoch, U. (eds.) Handbook of Quantitative Science and Technology Research, pp. 19–50. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht (2004)

Chapter Google Scholar

Garfield, E.: Citation analysis as a tool in journal evaluation. Science 178 , 417–479 (1972)

Hirsch, J.: An index to quantify an individuals scientific research output. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 102, pp. 16569–1657. National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC (2005)

Cobo, M., López-Herrera, A., Herrera-Viedma, E., Herrera, F.: Science mapping software tools: review, analysis and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 62 , 1382–1402 (2011)

Noyons, E., Moed, H., van Rann, A.: Integrating research perfomance analysis and science mapping. Scientometrics 46 , 591–604 (1999)

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., Lim, W.M.: How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 133 , 285–296 (2021)

Aria, M., Cuccurullo, C.: Bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informet. 11 (4), 959–975 (2017)

Aria, M., Cuccurullo, C.: Package ‘bibliometrix’. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/bibliometrix/bibliometrix.pdf . Accessed 10 July 2021

Börner, K., Chen, C., Boyack, K.: Visualisingg knowledge domains. Ann. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 37 , 179–255 (2003)

Morris, S., van der Veer Martens, B.: Mapping research specialities. Ann. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol. 42 , 213–295 (2008)

Zitt, M., Ramanana-Rahary, S., Bassecoulard, E.: Relativity of citation performance and excellence measures: from cross-field to cross-scale effects of field-normalisation. Scientometrics 63 (2), 373–401 (2005)

Li, L.L., Ding, G., Feng, N., Wang, M.-H., Ho, Y.-S.: Global stem cell research trend: bibliometric analysis as a tool for mapping trends from 1991 to 2006. Scientometrics 80 (1), 9–58 (2009)

Ebrahim, A.N., Salehi, H., Embi, M.A., Tanha, F.H., Gholizadeh, H., Motahar, S.M.: Visibility and citation impact. Int. Educ. Stud. 7 (4), 120–125 (2014)

Canas-Guerrero, I., Mazarrón, F.R., Calleja-Perucho, C., Pou-Merina, A.: Bibliometric analysis in the international context of the “construction & building technology” category from the web of science database. Constr. Build. Mater. 53 , 13–25 (2014)

Gaviria-Marin, M., Merigó, J.M., Baier-Fuentes, H.: Knowledge management: a global examination based on bibliometric analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 140 , 194–220 (2019)

Heradio, R., Perez-Morago, H., Fernandez-Amoros, D., Javier Cabrerizo, F., Herrera-Viedma, E.: A bibliometric analysis of 20 years of research on software product lines. Inf. Softw. Technol. 72 , 1–15 (2016)

Furstenau, L.B., et al.: Link between sustainability and industry 4.0: trends, challenges and new perspectives. IEEE Access 8 , 140079–140096 (2020). Article 9151934

van Eck, N.J., Waltman, L.: VOSviewer manual. Universiteit Leiden, Leiden (2021)

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., Jacomy, M.: Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In: Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference, pp. 361–362. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, San Jose CA (2009)

Chen, C.: How to use CiteSpace. Leanpub, Victoria, British Columbia, CA (2019)

yWorks.: yEd Graph Editor Manual. https://yed.yworks.com/support/manual/index.html . Accessed 13 July 2020

Moresi, E.A.D., Pierozzi Júnior, I.: Representação do conhecimento para ciência e tecnologia: construindo uma sistematização metodológica. In: 16th International Conference on Information Systems and Technology Management, TECSI, São Paulo SP (2019). Article 6275

Moresi, E.A.D., Pinho, I.: Proposta de abordagem para refinamento de pesquisa bibliográfica. New Trends Qual. Res. 9 , 11–20 (2021)

Moresi, E.A.D., Pinho, I.: Como identificar os tópicos emergentes de um tema de investigação? New Trends Qual. Res. 9 , 46–55 (2021)

Chen, Y.H., Chen, C.Y., Lee, S.C.: Technology forecasting of new clean energy: the example of hydrogen energy and fuel cell. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 4 (7), 1372–1380 (2010)

Ernst, H.: The use of patent data for technological forecasting: the diffusion of CNC-technology in the machine tool industry. Small Bus. Econ. 9 (4), 361–381 (1997)

Chen, C.: Science mapping: a systematic review of the literature. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2 (2), 1–40 (2017)

Prabhakaran, T., Lathabai, H.H., Changat, M.: Detection of paradigm shifts and emerging fields using scientific network: a case study of information technology for engineering. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 91 , 124–145 (2015)

Klavans, R., Boyack, K.W.: Identifying a better measure of relatedness for mapping science. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 57 (2), 251–263 (2006)

Kauffman, J., Kittas, A., Bennett, L., Tsoka, S.: DyCoNet: a Gephi plugin for community detection in dynamic complex networks. PLoS ONE 9 (7), e101357 (2014)

Grant, M.J., Booth, A.: A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 26 (2), 91–108 (2009)

Costa, A.P., Soares, C.B., Fornari, L., Pinho, I.: Revisão da Literatura com Apoio de Software - Contribuição da Pesquisa Qualitativa. Ludomedia, Aveiro Portugal (2019)

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., Smart, P.: Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 14 (3), 207–222 (2003)

Costa, A.P., Amado, J.: Content Analysis Supported by Software. Ludomedia, Oliveira de Azeméis - Aveiro - Portugal (2018)

Pinho, I., Leite, D.: Doing a literature review using content analysis - research networks review. In: Atas CIAIQ 2014 - Investigação Qualitativa em Ciências Sociais, vol. 3, pp. 377–378. Ludomedia, Aveiro Portugal (2014)

White, M.D., Marsh, E.E.: Content analysis: a flexible methodology. Libr. Trends 55 (1), 22–45 (2006)

Souza, F.N., Neri, D., Costa, A.P.: Asking questions in the qualitative research context. Qual. Rep. 21 (13), 6–18 (2016)

Pinho, I., Pinho, C., Rosa, M.J.: Research evaluation: mapping the field structure. Avaliação: Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior (Campinas) 25 , 546–574 (2020)

Costa, A., Moreira, A. de Souza, F.: webQDA - Qualitative Data Analysis (2019). www.webqda.net

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Catholic University of Brasília, Brasília, DF, 71966-700, Brazil

Eduardo Amadeu Dutra Moresi

University of Aveiro, 3810-193, Aveiro, Portugal

Isabel Pinho & António Pedro Costa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eduardo Amadeu Dutra Moresi .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Education and Psychology, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

António Pedro Costa

António Moreira

Department Didactics, Organization and Research Methods, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

Maria Cruz Sánchez‑Gómez

Adventist University of Africa, Nairobi, Kenya

Safary Wa-Mbaleka

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Moresi, E.A.D., Pinho, I., Costa, A.P. (2022). How to Operate Literature Review Through Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis Integration?. In: Costa, A.P., Moreira, A., Sánchez‑Gómez, M.C., Wa-Mbaleka, S. (eds) Computer Supported Qualitative Research. WCQR 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 466. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04680-3_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04680-3_13

Published : 05 May 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-04679-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-04680-3

eBook Packages : Intelligent Technologies and Robotics Intelligent Technologies and Robotics (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES