Your browser does not support javascript. Some site functionality may not work as expected.

- Images from UW Libraries

- Open Images

- Image Analysis

- Citing Images

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- Images Research Guide

Images Research Guide: Image Analysis

Analyze images.

Content analysis

- What do you see?

- What is the image about?

- Are there people in the image? What are they doing? How are they presented?

- Can the image be looked at different ways?

- How effective is the image as a visual message?

Visual analysis

- How is the image composed? What is in the background, and what is in the foreground?

- What are the most important visual elements in the image? How can you tell?

- How is color used?

- What meanings are conveyed by design choices?

Contextual information

- What information accompanies the image?

- Does the text change how you see the image? How?

- Is the textual information intended to be factual and inform, or is it intended to influence what and how you see?

- What kind of context does the information provide? Does it answer the questions Where, How, Why, and For whom was the image made?

Image source

- Where did you find the image?

- What information does the source provide about the origins of the image?

- Is the source reliable and trustworthy?

- Was the image found in an image database, or was it being used in another context to convey meaning?

Technical quality

- Is the image large enough to suit your purposes?

- Are the color, light, and balance true?

- Is the image a quality digital image, without pixelation or distortion?

- Is the image in a file format you can use?

- Are there copyright or other use restrictions you need to consider?

developed by Denise Hattwig , [email protected]

More Resources

National Archives document analysis worksheets :

- Photographs

- All worksheets

Visual literacy resources :

- Visual Literacy for Libraries: A Practical, Standards-Based Guide (book, 2016) by Brown, Bussert, Hattwig, Medaille ( UW Libraries availability )

- 7 Things You Should Know About... Visual Literacy ( Educause , 2015 )

- Keeping Up With... Visual Literacy (ACRL, 2013)

- Visual Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (ACRL, 2011)

- Visual Literacy White Paper (Adobe, 2003)

- Reading Images: an Introduction to Visual Literacy (UNC School of Education)

- Visual Literacy Activities (Oakland Museum of California)

- << Previous: Open Images

- Next: Citing Images >>

- Last Updated: Aug 6, 2024 12:41 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/newimages

Quick Links:

Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials

Student resources, welcome to the companion website.

Welcome to the companion website for Visual Methodologies, Fourth Edition, by Gillian Rose. The resources on the site have been specifically designed to support your study.

For students

- Searching for images online

- Author video

- Journal article

- Audio clip

About the book

Now in its Fourth Edition, Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Methodologies is a bestselling critical guide to the study and analysis of visual culture. Existing chapters have been fully updated to offer a rigorous examination and demonstration of an individual methodology in a clear and structured style.

Reflecting changes in the way society consumes and creates its visual content, new features include:

- Brand new chapters dealing with social media platforms, the development of digital methods and the modern circulation and audiencing of research images

- More 'Focus' features covering interactive documentaries, digital story-telling and participant mapping

- A Companion Website featuring links to useful further resources relating to each chapter.

A now classic text, Visual Methodologies appeals to undergraduates, graduates, researchers and academics across the social sciences and humanities who are looking to get to grips with the complex debates and ideas in visual analysis and interpretation.

About the author

Gillian Rose is Professor of Cultural Geography at The Open University, and her current research interests focus on contemporary visual culture in cities, and visual research methodologies. Her website, with links to many of her publications, is here:

http://www.open.ac.uk/people/gr334

She also blogs at

www.visualmethodculture.wordpress.com

And you can follow her on Twitter @ProfGillian.

Disclaimer:

This website may contain links to both internal and external websites. All links included were active at the time the website was launched. SAGE does not operate these external websites and does not necessarily endorse the views expressed within them. SAGE cannot take responsibility for the changing content or nature of linked sites, as these sites are outside of our control and subject to change without our knowledge. If you do find an inactive link to an external website, please try to locate that website by using a search engine. SAGE will endeavour to update inactive or broken links when possible.

Visual Methods in Qualitative Research

Qualitative researchers have a number of methods available to them for data collection, with the main workhorse being the qualitative interview. However, as the world becomes increasingly visual due to the proliferation of the internet and multimedia technologies, qualitative research methods are changing. Often used in participatory research (though certainly not exclusive to such designs), visual methods of collecting qualitative data offer new ways to approach our participants, our data, and our analyses.

Discover How We Assist to Edit Your Dissertation Chapters

Aligning theoretical framework, gathering articles, synthesizing gaps, articulating a clear methodology and data plan, and writing about the theoretical and practical implications of your research are part of our comprehensive dissertation editing services.

- Bring dissertation editing expertise to chapters 1-5 in timely manner.

- Track all changes, then work with you to bring about scholarly writing.

- Ongoing support to address committee feedback, reducing revisions.

Scholars have described several ways of incorporating visual methods into qualitative research, but I will focus on just two examples here. The first approach uses photographs taken by participants. If appropriate for your research study (remember that methods and design must align with the purpose, problem, and research questions of your study), one way to collect data is through your participants. Let’s say that you are conducting a phenomenological study on the lived experiences of women with breast cancer. After selecting and recruiting your sample, you might give your participants instructions to take photographs that tell a story of what life is like for them. In the beginning, leave this prompt open; you can always refine it if your participants want clarification later. The photos that they take become data and can be coded and analyzed in ways similar to what you would do for text. You may also choose to conduct follow-up interviews with these participants to learn more about why they took the photos that they did.

A second approach is to introduce photographs or visual aids into your interviews that you, as the researcher, have selected. Sometimes a visual stimulus can be more helpful to get participants talking rather than a relatively open-ended question. Instead of conducting a semi-structured interview using only questions, you could introduce photographs related

to your research topic to generate discussion. Alternatively, you could have your participants find photographs on your research topic to bring to the interview.

These are just a few ways to incorporate visual methods into qualitative research. The possibilities are endless, and it is time for researchers get more creative and engage with new ways of thinking about our research!

The Visual Communication Guy

Learn Visually. Communicate Powerfully.

- About The VCG

- Contact Curtis

- Five Paragraph Essay

- IMRaD (Science)

- Indirect Method (Bad News)

- Inverted Pyramid (News)

- Martini Glass

- Narrative Format

- Rogerian Method

- Toulmin Method

- Apostrophes

- Exclamation Marks (Points)

- Parentheses

- Periods (Full Stops)

- Question Marks

- Quotation Marks

- Plain Language

- APPEALS: ETHOS, PATHOS, LOGOS

- CLUSTER ANALYSIS

- FANTASY-THEME

- GENERIC CRITICISM

- IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM

- NEO-ARISTOTELIAN

- O.P.T.I.C. (VISUAL ANALSYIS)

- S.O.A.P.S.T.O.N.E. (WRITTEN ANALYSIS)

- S.P.A.C.E.C.A.T. (RHETORICAL ANALYSIS)

- BRANCHES OF ORATORY

- FIGURES OF SPEECH

- FIVE CANONS

- LOGICAL FALLACIES

- Information Design Rules

- Arrangement

- Organization

- Negative Space

- Iconography

- Photography

- Which Chart Should I Use?

- “P” is for PREPARE

- "O" is for OPEN

- "W" is for WEAVE

- “E” is for ENGAGE

- PRESENTATION EVALUTION RUBRIC

- POWERPOINT DESIGN

- ADVENTURE APPEAL

- BRAND APPEAL

- ENDORSEMENT APPEAL

- HUMOR APPEAL

- LESS-THAN-PERFECT APPEAL

- MASCULINE & FEMININE APPEAL

- MUSIC APPEAL

- PERSONAL/EMOTIONAL APPEAL

- PLAIN APPEAL

- PLAY-ON-WORDS APPEAL

- RATIONAL APPEAL

- ROMANCE APPEAL

- SCARCITY APPEAL

- SNOB APPEAL

- SOCIAL APPEAL

- STATISTICS APPEAL

- YOUTH APPEAL

- The Six Types of Résumés You Should Know About

- Why Designing Your Résumé Matters

- The Anatomy of a Really Good Résumé: A Good Résumé Example

- What a Bad Résumé Says When It Speaks

- How to Write an Amazing Cover Letter: Five Easy Steps to Get You an Interview

- Make Your Boring Documents Look Professional in 5 Easy Steps

- Business Letters

- CONSUMER PROFILES

- ETHNOGRAPHY RESEARCH

- FOCUS GROUPS

- OBSERVATIONS

- SURVEYS & QUESTIONNAIRES

- S.W.O.T. ANALYSES

- USABILITY TESTS

- CITING SOURCES: MLA FORMAT

- MLA FORMAT: WORKS CITED PAGE

- MLA FORMAT: IN-TEXT CITATIONS

- MLA FORMAT: BOOKS & PAMPHLETS

- MLA FORMAT: WEBSITES AND ONLINE SOURCES

- MLA FORMAT: PERIODICALS

- MLA FORMAT: OTHER MEDIA SOURCES

- Course Syllabi

- Checklists and Peer Reviews (Downloads)

- Communication

- Poster Prints

- Poster Downloads

- Handout & Worksheet Downloads

- QuickGuide Downloads

- Downloads License Agreements

How to Do a Visual Analysis (A Five-Step Process)

One of the best ways to improve visual literacy and visual communication skills is to analyze a visual artifact of some kind. If you haven’t done one before, a visual analysis can seem kind of overwhelming. Doing one requires you to think about a visual artifact of some kind, whether it be a billboard on the side of the freeway, an Andy Warhol painting, or a new toaster for sale, and actually have something important to say about it. A visual analysis requires you to think about what the artifact is, what its role in society is, and the impact is has had or probably will have on viewers. To do such an analysis, you need to understand how to do five important things:

1) choose a visual artifact that has meaning, purpose, or intrigue; 2) research the artifact to understand its context; 3) evaluate the rhetorical devices the artifact uses to affect an audience; 4) examine the design principles the artifact employs; 5) make a sophisticated argument about the topic based on your analysis.

It’s been my experience that students approaching a visual analysis assume that they have to find a visual artifact that is overtly controversial (like a racy lingerie ad using teenagers to sell products) or else there is nothing to say about it. However, thousands and thousands of visual objects and images that surround us make statements that are worth evaluating. In fact, you might check out a student example of an a visual analysis about the Volkswagen Beetle “Lemon” ad to see just how a seemingly mundane topic can be quite interesting.

With that in mind, I put together a 5-step process for putting together an effective visual analysis. If you would like to use this infographic for teaching or other purposes, feel free to download the PDF version . You can find other helpful free downloads on my resources page.

Related Articles

The OPTIC Strategy for Visual Analysis

What is Visual Rhetoric?

Why Do Photos Matter on the Internet?

- ← The Logical Fallacy Collection: 30 Ways to Lose an Argument

- Top 5 Rules for Designing with Photographs →

Shop for your perfect poster print or digital download at our online store!

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 Visual and Contextual Analysis

J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie

The study of visual culture relies on two key skill sets: visual analysis and contextual analysis.

Visual Analysis

Visual Analysis is just a fancy way of saying “give a detailed description of the image.” It is easy to assume that visual analysis is easy or that it isn’t necessary because anyone can just look at the image and see the same thing you see. But is it really that simple?

As individual viewers we all bring our own background, perspective, education, and ideas to the viewing of an image. What you notice right away in an image may not be the same thing your classmate (or your grandmother or your neighbour) notices. And this is perfectly fine!

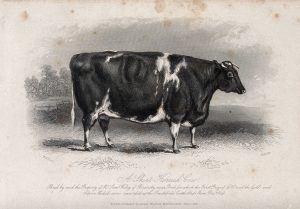

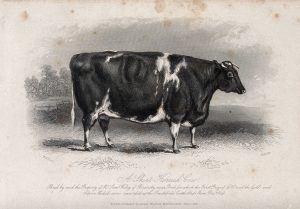

What do you see when you look at the images below?

In all three cases we have pictures of cows, but there are some important similarities and differences. What do you think is important to note about these images?

Reflection Exercise

Take a 5-10 minutes to jot down a detailed description (visual analysis) for each of the images above.

- What do you notice?

- What do you see?

- What part of the image is your eye drawn to first?

- How are these images similar? How are they different?

Contextual Analysis

Contextual analysis is another very important skill for studying images. This is a fancy way of saying “we need more information about this picture.” You will often have to do external research to build and support your contextual analysis. There is an old saying that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” but we need to think carefully and critically about this. A picture can not tell us everything we might want to know about it! Sometimes it is very important to dig deeper through research to learn more about an image in order to understand how it participates in the meaning making process.

Here is a list of some questions that are useful for guiding contextual analysis. This is not an exhaustive list and not all questions will apply in all cases:

- Who made this image? Why?

- Where was the image made? (In a different part of the world? In a laboratory? On the beach?)

- Who was the intended audience for this image?

- Where was the image meant to be viewed? (A textbook? A gallery? As part of a movie set? In a family photo album?)

- When was this image made? How do you know?

- What kinds of technologies were used to make this image? What kinds of limitations were there on this technology at this time?

- Is there text in the image? If so, how does it shape our understanding of what we are looking at? What about the image caption? How does it shape our understanding of what we are looking at?

Sometimes you can get clues from the image that can help you answer these kinds of questions, but often you will have to branch out and turn to books, articles, websites, documentary films, and other resources to help build and develop your contextual analysis.

In our examples above the captions give us quite a bit of information. We learn, for instance, who made the pictures (and, in one case, we learn that this information isn’t known). We learn when the images were made and the type of pictures they are–although we may need to look up what an etching , stereograph , or an albumen print is. The titles are fairly descriptive in that they provide us some basic information about what we are looking at.

Reflection Exercise – Part II

The visual analysis we just did combined with the information provided in the image captions gives us a place to start with our investigation into these images. But are many things that we still don’t know about these pictures.

What other things might we want to know if we were going to write about these pictures? Take a few moments and jot down a list of questions you have about these images.

As we generate questions based on these images and then start to do the research to find out the answers to those questions we are starting to build our contextual analysis. Through research we would learn, for instance, that the firm of Underwood & Underwood was a leading manufacturer of stereograph cards in the 19th century and that stereograph cards had a massive public and commercial appeal . The two images, when viewed through a special device known as a stereoscope , merge together to form an image that looks 3-D. Imagine how exciting this would be for viewers in an age before television, movies, and video games. Some have even described this as an early form of virtual reality !

Further research will show us that Edward H. Hacker was a printmaker in Britain in the 19th century and that he was best known for creating engravings of animal pictures. In an era when it wasn’t easy to reproduce paintings, this allowed multiple copies of an image to be shared and circulated. In our example, above he is reproducing a painting by William Henry Davis , an artist who specialised in portraits of livestock.

Today it might seem odd to us that people would want pictures painted of their cows and we might even wonder why someone would hire a printmaker to make reproductions of these images. Why would people want images of their cows? And further, why does the cow in the first picture above look so strange? She is so enormous that her little tiny, skinny legs couldn’t possibly support her body. What is going on here? Did Davis now know how to paint cows?

In fact, Davis was a well-respected artist. The answer to this question can be discovered through a bit of research (more contextual analysis). As we dig into this investigation, we would soon learn that this type of picture was part of a larger 19th trend for creating images of livestock that exaggerated their features as a way to advertise certain breeds and breeders . In other words, the farmers that were commissioning these images were using these pictures to try and prove that their animals were better than the animals owned by competing farmers. These pictures can not be separated out from the economics of 18th and 19th century British farming practices.

In 2018 the Museum of English Rural Life posted a photograph of a very large ram with the words “look at this absolute unit.” This Twitter post went viral and brought a lot of attention to the history behind these kinds of images. Having a picture like this circulate on social media brought a new layer of meaning to the photograph . It didn’t replace the original context, but it added to the discussions about it.

When an image is taken out of its original context new meanings can be generated. Take, for example, a controversial advertising campaign launched in the spring of 2023 by the Italian government . It features the very recognizable central figure from Sandro Botticelli’s 15th century painting known as “ Birth of Venus .” But in this campaign she is out and about enjoying the tourist sites in Italy, playing the role of Instagram influencer. This campaign provoked a strong reaction and many people criticised what they saw as trivialising and making a mockery of a beloved work of art. The associations people have with this painting–that it is a “masterpiece” to be admired and venerated–have fueled this criticism. If the central figure in these advertisements was not a recognizable figure it is unlikely that there would have been any controversy at all. By taking this figure out of context and putting her in AI generated scenes of Italian tourism, some feel it changes the meaning of the original picture. Love it or hate it, the one thing everyone agrees on is that this campaign has generated much discussion!

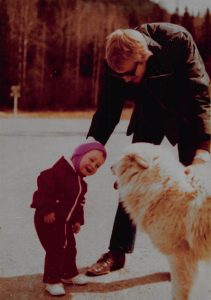

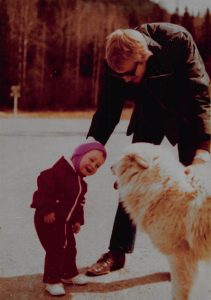

Visual and Contextual Analysis Exercise

Find a picture that you think expresses something about who you are. It can be from your childhood, a photograph of your dorm room, or a picture of the aunt who taught you how to read. Perhaps it is a picture of you cheering on your favourite sports team or of a special dinner shared with close friends. It doesn’t matter what the subject is as long as it is an example of a picture that you think says something about you.

Step 1 (Visual Analysis): Write a description of this picture. Try to stick to only description in this step, really look at the picture carefully and consider things like:

- What medium is it (e.g.: is it a photograph, a painting, etc.)?

- What colours are used?

- How is it composed? How big is it?

- Are there people in the image?

- Is the image dark or light?

- What is in the background?

- Is there anything blurry or unclear?

*Note: This is not an exhaustive list of questions. Rather, they are given as examples to help you think about what kinds of things to focus on.

Step 2 (Contextual Analysis): Imagine you are going to show this picture to a complete stranger, someone who doesn’t know you at all. Make a list of everything you think that person needs to know about the picture in order to learn a bit about you? What information might help that person understand why this picture is meaningful for you? For example, was this photograph taken on your birthday? Is it a picture of your first pet? Is the person who is blurry in the background your best friend who moved away when you were 11? Then think about why these things are important to you. In other words, what do you know about this picture that wouldn’t be obvious to someone else?

If I were doing this exercise with this photograph, in step #1 I would focus on things like the colour of the child’s clothing, the size of the dog, and the way the adult, child, and dog are posed, including that the man has one hand on the child, one hand on the dog. I would talk about it being a photograph and how the faded tones suggest that this is an old photograph. I would note that the photograph was taken outside and that these three are standing on what appears to be pavement but that there are trees in the background. There is also what appears to be a wooden sign in the background but it is too blurry to read. I would also point out that the shadows on the ground indicate that it was a sunny day, but the type of clothing the two human figures are wearing suggests that it was also a cold day.

If I were to continue on and complete step #2 I would list that this was a photograph taken in the mid-1970s by my mother and that it is a picture of me (Keri) and my uncle with a dog we happened to meet in the parking lot of Mount Robson Park while our family was moving from British Columbia to Alberta. This was not our dog. We had never met him before nor did we ever see him again. But he was friendly, and I was absolutely enthralled by how fluffy he was. My uncle took me over to introduce me to the dog, staying close to make sure the dog didn’t hurt me.

This picture holds meaning for me for a number of reasons. First of all, it is an early example of my love of animals. Secondly, Mount Robson Park is part of the Canadian Rocky Mountains and was often a destination for family vacations. These trips shaped my interest in nature and outdoor activities in spaces like Provincial and National Parks. This led to me deciding to write my MA thesis on the visual culture of these kinds of places, a document that was eventually turned into a book . And lastly, this picture has taken on a new layer of importance for me lately as my uncle pictured here recently died of cancer. Even though it isn’t a great picture in terms of technical quality, it is a picture that I have framed in my house because it holds a lot of meaning for me.

By doing this exercise you are slowing down the process of meaning making and thinking about how the visual elements of the image relate to the larger context that helps to shape why this picture holds meaning for you. You can see how the two types of analysis–visual and contextual–work together. You need both halves of this equation. By slowing down and doing some deep noticing in our visual analysis, we can notice things that become significant when we switch over to contextual analysis. And our contextual analysis can provide us a starting place for further research if needed.

With this exercise you were working with an image that you are already very familiar with. But this same process can get repeated with any image. When you are working with an image that isn’t from your own personal life, there will likely be more steps needed to arrive at a contextual analysis–research, further reading, etc.–but the process itself remains the foundation for critical thinking about images.

Look Closely: A Critical Introduction to Visual Culture Copyright © 2023 by J. Keri Cronin and Hannah Dobbie is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Visual Methods

Visual Analysis: How to Analyze a Painting and Write an Essay

A visual analysis essay is an entry-level essay sometimes taught in high school and early university courses. Both communications and art history students use visual analysis to understand art and other visual messages. In our article, we will define the term and give an in-depth guide on how to look at a piece of art and write a visual analysis essay. Stay tuned until the end for a handy visual analysis essay example from our graduate paper writing service .

What Is Visual Analysis?

Visual analysis is essential in studying Communication, English, and Art History. It's a fundamental part of writing about art found in scholarly books, art magazines, and even undergraduate essays. You might encounter a visual analysis as a standalone assignment or as part of a larger research paper.

When you do this type of assignment, you're examining the basic elements of an artwork. These include things like its colors, lines, textures, and size. But it goes beyond just describing these elements. A good analysis also considers the historical context in which the artwork was created and tries to understand what it might mean to different people.

It also encourages you to look closely at details and think deeply about what an artwork is trying to say. This kind of analysis makes you appreciate art more and teaches you how to explain your ideas clearly based on what you see in the artwork.

What is the Purpose of Visual Analysis?

The purpose of a visual analysis is to recognize and understand the visual choices the artist made in creating the artwork. By looking closely at different elements, analysts can learn a lot about how an artwork was made and why the artist made certain choices.

For example, studying how colors are used or how things are arranged in the artwork can reveal its themes or the emotions it's trying to convey. Also, understanding the time period when the artwork was created helps us see how societal changes and cultural ideas influenced its creation and how people reacted to it.

If you don’t feel confident working on your task alone, leave us a request - ' write my paper for me ' and we'll handle it for you professionally.

Another Visual Analysis Paper Looming?

Don't stress! Send your requirements and breathe easy – our writing experts are here to help.

How to Write a Visual Analysis Step-by-Step

To create an insightful visual analysis, you should not only examine the artwork in detail but also situate it within a broader cultural and historical framework. This process can be broken down into three main steps:

- Identifying, describing, and analyzing the visual material

- Situating the visual material in its context

- Interpreting and responding to the content of the visual material.

Let’s discuss each of these steps in more detail.

Step 1: Identify, Describe, and Analyze the Visual Material

Begin by clearly identifying the visual material you will analyze. This could be a painting, photograph, sculpture, advertisement, or any other visual artwork. Provide essential information such as the title, artist, date, and medium.

Next, offer a detailed description of the visual material. Focus on the key elements and principles of design, such as:

Describe what you see without interpreting its meaning yet. For instance, note the use of bright colors, the placement of objects, the presence of figures, and the overall layout. This descriptive part forms the foundation of your analysis, allowing your reader to visualize the artwork.

Afterward, consider how the artist uses elements like contrast, balance, emphasis, movement, and harmony. Analyze the techniques and methods used and how they contribute to the overall effect of the piece.

Step 2: Situate the Visual Material in its Context

To fully understand a piece of visual material, you need to consider its historical and cultural context. Start by researching the time period when the artwork was created. Look at the social, political, and economic conditions of that time, and see if there were any cultural movements that might have influenced the artwork.

Next, learn about the artist and their reasons for creating the visual material. Find out about the artist's life, other works they have made, and any statements they have made about this piece. Knowing the artist’s background can give you valuable insights into the artwork's purpose and message.

Finally, think about how the visual material was received by people when it was first shown and how it has impacted others over time. Look for reviews and public reactions, and see if it influenced other works or movements. This will help you understand the significance of the visual material in the larger cultural and artistic context.

Step 3: Interpret and Respond to the Content of the Visual Material

Now, combine your description, analysis, and understanding of the context to interpret what the visual material means. Talk about the themes, symbols, and messages the artwork conveys. Think about what it reveals about human experiences, society, or specific issues. Use evidence from earlier steps to support your interpretation.

Afterward, consider your own reaction to the visual material. How does it personally resonate with you? What emotions or thoughts does it provoke? Your personal response adds a subjective aspect to your analysis, making it more relatable.

Finally, summarize your findings and emphasize the importance of the visual material. Highlight key aspects from your identification, description, analysis, context, and interpretation. Then, it concludes by reinforcing the impact and significance of the visual material in both its original setting and its enduring influence.

Who Does Formal Analysis of Art

Most people who face visual analysis essays are Communication, English, and Art History students. Communications students explore mediums such as theater, print media, news, films, photos — basically anything. Comm is basically a giant, all-encompassing major where visual analysis is synonymous with Tuesday.

Art History students study the world of art to understand how it developed. They do visual analysis with every painting they look it at and discuss it in class.

English Literature students perform visual analysis too. Every writer paints an image in the head of their reader. This image, like a painting, can be clear, or purposefully unclear. It can be factual, to the point, or emotional and abstract like Ulysses, challenging you to search your emotions rather than facts and realities.

6 Questions to Answer Before Analyzing a Piece of Art

According to our experienced term paper writer , there are six important questions to ask before you start analyzing a piece of art. Answering these questions can make writing your analysis much easier:

- Who is the artist, and what type of art do they create? - To place the artwork in context, you should identify the artist and understand the type of art they create.

- What was the artist's goal in creating this painting? - Determine why the artist created the artwork. Was it to convey a message, evoke emotions, or explore a theme?

- When and where was this artwork made? - Knowing the time and place of creation helps understand the cultural and historical influences on the artwork.

- What is the main focus or theme of this artwork? - Identify what the artwork is about. This could be a person, place, object, or abstract concept.

- Who was the artwork created for? - To provide insight into its style and content, consider who the artist intended to reach with their work.

- What historical events or cultural factors influenced this painting? - Understanding the historical background can reveal more about the significance and meaning of the artwork.

Count on the support of the professional writers of our essay writing service .

Elements of the Visual Analysis

To fully grasp formal analysis, it's important to differentiate between the elements and principles of visual analysis. The elements are the basic building blocks used to create a piece of art. These include:

| Art Element 🎨 | Description 📝 |

| ✏️Line | A mark with length and direction, which can define shapes, create textures, and suggest movement. |

| 🌗Value | The lightness or darkness of a color, which helps to create depth and contrast. |

| 🔶Shapes | Two-dimensional areas with a defined boundary, such as circles, squares, and triangles. |

| 🔲Forms | Three-dimensional objects with volume and thickness, like cubes, spheres, and cylinders. |

| 🌌Space | The area around, between, and within objects, which can be used to create the illusion of depth. |

| 🌈Color | The hues, saturation, and brightness in artwork, used to create mood and visual interest. |

| 🖐️Texture | The surface quality of an object, which can be actual (how it feels) or implied (how it looks like it feels). |

Principles of the Visual Analysis

The principles, on the other hand, are how these elements are combined and used together to create the overall effect of the artwork. These principles include:

| Principle of Art 🎨 | Description 📝 |

| ⚖️Balance | The distribution of visual weight in a composition, which can be symmetrical or asymmetrical. |

| 🌗Contrast | The difference between elements, such as light and dark, to create visual interest. |

| 🏃♂️Movement | The suggestion or illusion of motion in an artwork, guiding the viewer’s eye through the piece. |

| 🎯Emphasis | The creation of a focal point to draw attention to a particular area or element. |

| 🔄Pattern | The repetition of elements to create a sense of rhythm and consistency. |

| 📏Proportion | The relationship in size between different parts of an artwork, contributing to its harmony. |

| 🔗Unity | The sense of cohesiveness in an artwork, where all elements and principles work together effectively. |

Visual Analysis Outline

It’s safe to use the five-paragraph essay structure for your visual analysis essay. If you are looking at a painting, take the most important aspects of it that stand out to you and discuss them in relation to your thesis.

.png)

In the introduction, you should:

- Introduce the Artwork : Mention the title, artist, date, and medium of the artwork.

- Provide a Brief Description : Offer a general overview of what the artwork depicts.

- State the Purpose : Explain the goal of your analysis and what aspects you will focus on.

- Thesis Statement : Present a clear thesis statement that outlines your main argument or interpretation of the artwork.

The body of the visual analysis is where you break down the visual material into its component parts and examine each one in detail. This section should be structured logically, with each paragraph focusing on a specific element or aspect of the visual material.

- Description: Start with a detailed description of the visual material. Describe what you see without interpreting or analyzing it yet. Mention elements such as color, line, shape, texture, space, and composition. For instance, if analyzing a painting, describe the subject matter, the arrangement of figures, the use of light and shadow, etc.

- Analysis of Visual Elements: Analyze how each visual element contributes to the overall effect of the material. Discuss the use of color (e.g., warm or cool tones, contrasts, harmonies), the role of lines (e.g., leading lines, contours), the shapes (e.g., geometric, organic), and the texture (e.g., smooth, rough). Consider how these elements work together to create a certain mood or message.

- Contextual Analysis: Examine how the context in which the visual material was created and is being viewed influences its interpretation. This includes historical, cultural, social, and political factors. Discuss how these contextual elements impact the meaning and reception of the visual material.

- Interpretation: Discuss your interpretation of the visual material. Explain how the visual elements and contextual factors contribute to the meaning you derive from it. Support your interpretation with specific examples from the material.

- Comparative Analysis (if applicable): If relevant, compare the visual material with other works by the same creator or with similar works by different creators. Highlight similarities and differences in style, technique, and thematic content.

The conclusion of a visual analysis essay summarizes the main points of the analysis and restates the thesis in light of the evidence presented.

- Restate Thesis: Reiterate your thesis statement in a way that reflects the depth of your analysis. Show how your understanding of the visual material has been supported by your detailed examination.

- Summary of Main Points: Summarize the key points of your analysis. Highlight the most important findings and insights.

- Implications: Discuss the broader implications of your analysis. What does your analysis reveal about the visual material? How does it contribute to our understanding of the creator's work, the time period, or the cultural context?

- Closing Thought: End with a final thought that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. This could be a reflection on the significance of the visual material, a question for further consideration, or a statement about its impact on you or on a broader audience.

If you want a more in-depth look at the classic essay structure, feel free to visit our 5 PARAGRAPH ESSAY blog.

Visual Analysis Example

In this section, we've laid out two examples of visual analysis essays to show you how it's done effectively. Get inspired and learn from them!

Key Takeaways

Visual analysis essays are fundamental early in your communications and art history studies. Learning how to formally break down art is key, whether you're pursuing a career in art or communications.

Before jumping into analysis, get a solid grasp of the painter's background and life. Analyzing a painting isn't just for fun, as you need to pay attention to the small details the painter might have hidden. Knowing how to do this kind of assignment not only helps you appreciate art more but also lets you deeply understand the media messages you encounter every day.

If you enjoyed this article and found it insightful, make sure to also check out the summary of Lord of the Flies and an article on Beowulf characters .

If you read the whole article and still have no idea how to start your visual analysis essay, let a professional writer do this job for you. Contact us, and we’ll write your work for a higher grade you deserve. All college essay service requests are processed fast.

Paper Panic?

Our expert academics can help you break through that writer's block and craft a paper you can be proud of.

What are the 4 Steps of Visual Analysis?

How to write a formal visual analysis, what is the function of visual analysis.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

- Added new sections

- Added new writing steps

- Added a new example

- Updated an outline

- Duke University. (n.d.). Visual Analysis . https://twp.duke.edu/sites/twp.duke.edu/files/file-attachments/visual-analysis.original.pdf

- Glatstein, J. (2019, December 9). Formal Visual Analysis: The Elements & Principles of Composition . Www.kennedy-Center.org. https://www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/articles-and-how-tos/articles/educators/visual-arts/formal-visual-analysis-the-elements-and-principles-of-compositoin/

- MADA: Visual analysis . (n.d.). Student Academic Success. https://www.monash.edu/student-academic-success/excel-at-writing/annotated-assessment-samples/art-design-and-architecture/mada-visual-analysis

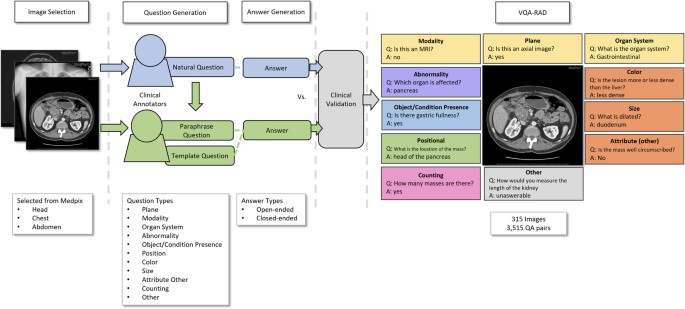

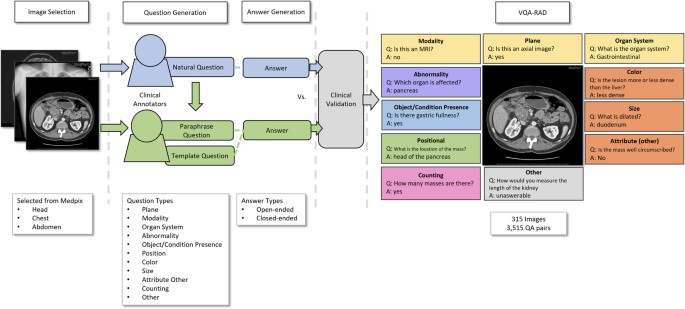

Visual Analysis of Scene-Graph-Based Visual Question Answering

New citation alert added.

This alert has been successfully added and will be sent to:

You will be notified whenever a record that you have chosen has been cited.

To manage your alert preferences, click on the button below.

New Citation Alert!

Please log in to your account

Information & Contributors

Bibliometrics & citations, view options, supplementary material, index terms.

Computing methodologies

Machine learning

Machine learning approaches

Neural networks

Human-centered computing

Visualization

Visualization application domains

Visual analytics

Visualization systems and tools

Recommendations

Lightweight visual question answering using scene graphs.

Visual question answering (VQA) is a challenging problem in machine perception, which requires a deep joint understanding of both visual and textual data. Recent research has advanced the automatic generation of high-quality scene graphs from images, ...

An analysis of graph convolutional networks and recent datasets for visual question answering

Graph neural network is a deep learning approach widely applied on structural and non-structural scenarios due to its substantial performance and interpretability recently. In a non-structural scenario, textual and visual research topics like ...

Visual-Textual Semantic Alignment Network for Visual Question Answering

VQA task requires deep understanding of visual and textual content and access to key information to better answer the question. Most of current works only use image and question as the input of the network, where the image features are over-...

Information

Published in.

Association for Computing Machinery

New York, NY, United States

Publication History

Check for updates, author tags.

- explainable AI

- scene graphs

- visual analytics

- Research-article

- Refereed limited

Funding Sources

- Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)

Acceptance Rates

Contributors, other metrics, bibliometrics, article metrics.

- 0 Total Citations

- 327 Total Downloads

- Downloads (Last 12 months) 327

- Downloads (Last 6 weeks) 26

View options

View or Download as a PDF file.

View online with eReader .

HTML Format

View this article in HTML Format.

Login options

Check if you have access through your login credentials or your institution to get full access on this article.

Full Access

Share this publication link.

Copying failed.

Share on social media

Affiliations, export citations.

- Please download or close your previous search result export first before starting a new bulk export. Preview is not available. By clicking download, a status dialog will open to start the export process. The process may take a few minutes but once it finishes a file will be downloadable from your browser. You may continue to browse the DL while the export process is in progress. Download

- Download citation

- Copy citation

We are preparing your search results for download ...

We will inform you here when the file is ready.

Your file of search results citations is now ready.

Your search export query has expired. Please try again.

Brill | Nijhoff

Brill | Wageningen Academic

Brill Germany / Austria

Böhlau

Brill | Fink

Brill | mentis

Brill | Schöningh

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht

V&R unipress

Open Access

Open Access for Authors

Transformative Agreements

Open Access and Research Funding

Open Access for Librarians

Open Access for Academic Societies

Discover Brill’s Open Access Content

Organization

Stay updated

Corporate Social Responsiblity

Investor Relations

Policies, rights & permissions

Review a Brill Book

Author Portal

How to publish with Brill: Files & Guides

Fonts, Scripts and Unicode

Publication Ethics & COPE Compliance

Data Sharing Policy

Brill MyBook

Ordering from Brill

Author Newsletter

Piracy Reporting Form

Sales Managers and Sales Contacts

Ordering From Brill

Titles No Longer Published by Brill

Catalogs, Flyers and Price Lists

E-Book Collections Title Lists and MARC Records

How to Manage your Online Holdings

LibLynx Access Management

Discovery Services

KBART Files

MARC Records

Online User and Order Help

Rights and Permissions

Latest Key Figures

Latest Financial Press Releases and Reports

Annual General Meeting of Shareholders

Share Information

Specialty Products

Press and Reviews

Share link with colleague or librarian

Stay informed about this journal!

- Get New Issue Alerts

- Get Advance Article alerts

- Get Citation Alerts

Visual Research Methods: Qualifying and Quantifying the Visual

The role of visual research methods in ethnographic research has been significant, particularly in place-making and representing visual culture and environments in ways that are not easily substituted by text. Digital media has extended into mundane, everyday existences and routines through most noticeably the modern smartphone, social media and digital artefacts that have created new forms of ethnographic enquiry. Ethnographers have engaged in this relatively new possibility of exploring how social media and new technologies transform the way we view social realities through the digital experience. The paper discusses the possible role of visual research methods in multimethod research and the theoretical underpinning of interpreting visual data. In the process of interpreting and analysing visual data, there is a need to acknowledge the possible ambiguity and polysemic quality of visual representation. It presents selectively the use of visual methods in an ethnographic exploration of early childhood settings through the use of internet-based visual data, researcher and participant-generated visual materials and media, together with visual-elicited (e.g. drawings, still images, video clips) information data through several examples. This approach in ‘visualizing’ the curriculum also unveils some aspects of the visual culture or the ‘hidden curriculum’ in the learning environment.

Although visual methods have become increasing importance, it has traditionally taken a secondary place when compared to narrative approaches based on text and verbal discourse. The internet and electronic communications have made an attentiveness to the ‘visual’ essential in education and educational research. Qualitative researchers have made progress in developing visual methodologies to study visual culture and phenomena ( Metcalfe, 2016 ; Prosser, 2007 ). The issue of new technologies and developments producing shifts in the way we conceptualize and experience social and electronic realities that we experience (Sarah Pink, 2012). Ethnographers have the option to explore the ways in which these new technologies, software and images have become part of their social reality and that their focus may be on how these technologies are appropriated rather than how they transform the basis of the world that we live in ( Coleman, 2010 ; Miller, 2011 ). The role of visual methodologies and ethnography in looking at how the curriculum is enacted and articulated in everyday practice will be explored.

Visual ethnographic study explores the complex interactions and relationships between local practices of the study and global implications and influences of digital media, the materiality and the politics of representation. The representation through visuality of digital media includes the mundane, everyday routines, the manifestation of cultural life and modes of communication. Media in many instances have become central to the articulation and expression of valued beliefs, ceremonious practices and modes of being ( Coleman, 2010 ). It is therefore essential to press beyond the boundaries of narrow presumptions about the limitations of the digital experience.

Visual ethnography engages with methods through its process of research, analysis and representation. It is inescapably collaborative, to a certain extent is participatory, involves analysing visual cultures, and requires an understanding of how the data set materials from both researcher and participant relate to one another. The process of audio-visual recording of research participants while ‘walking with them’ produces a research encounter that captures the ‘place in a phenomenological sense ( Pink, 2014 ). These processes constitute multisensory experiences and a collaborative work of visual (audio) ethnographic representations of urban contexts in the case study. Visual ethnography through photography and video captures a sense of a place, its history and cultural contexts, maybe everyday life, routines, languages, social interactions and gestures of communication, with other material and sensorial realities of the environment and place.

The gathering of pre-existing societal imagery and found imagery although usually regarded as secondary data requires a minimum reflexive knowledge of the technical and expressive aspects of imagery and representational techniques so as to be able to read and utilize them in an appropriate way. Therefore, some form of visual competence is required and the audience often pays attention to the historical and cultural aspects and contexts of production and consumption ( Pauwels, 2007 ). Researcher-generated imagery requires a sufficient degree of technical expertise that allow them to produce images and other forms of visual representations and that they are aware of cultural conventions and perceptual principles of the academic or non-academic audience that they aim to address. Visual ethnography is also concerned with understanding how we know as well as the environments in which knowledge is generated and it involves engaging with the philosophy of knowledge, of practice and of the place and space (Sarah Pink, 2014 ). This form of methodological focus through the visual requires a commitment to visual theory and researcher positionality particularly with respect to the literal and figurative aspects of one’s perspective ( Metcalfe, 2016 ).

Visual culture becomes ingrained in the school culture that is typically unquestioned and unconscious, but it forms a ‘hidden curriculum’ because it is both visual yet unseen. The organizational culture is influential in the organization’s outcomes as the ‘ethos’ links it with the school culture and ultimately the organization’s effectiveness. The organizational culture through ethnographic methodological framework allows an analytic approach to understanding the processes and rationale behind ‘school life’ ( Prosser, 2007 ). The debate goes on regarding the significance of the visual culture of schools and centres and the argument that visual culture and image-based methodologies are as important as number and word-based methodologies in the constructions of school culture and its influence on education policy. Visual-centric approach highlights and gives priority to what is visually perceived rather than what is written, spoken or statistically measured. Observed events, routines, rituals, artefacts, materials, spaces and behaviours in everyday routines are the evidence and markings of the past, present and future hidden curriculum.

The following sections discuss the methodological, theoretical and conceptual frameworks through which visual data may be interpreted. A combination of methodological strategies, empirical approaches, perspectives and interpretive-analytic stances enhances the rigor, depth and complexity of the research inquiry ( Denzin, 2012 ; Flick, 2018 ).

2 Methodological Consideration Using Visual Methods

The nature of visual research methods has posed some challenges based on issues of concern regarding the validity and rigor of such approaches. This has led to some challenges in identifying studies that integrate these methods with mixed methods research that use both quantitative and qualitative strategies ( Shannon-Baker & Edwards, 2018 ). The intersection of visual methods with mixed methods research allow complements and expansion of qualitative and quantitative data and the approach is also in alignment with philosophical and theoretical assumptions ( Clark & Ivankova, 2016 ), Shannon-Baker & Edwards, (2018) points out that there are methodological differences between a mixed methods study that utilizes visual research methods and visual methods study that utilizes mixed methods approaches. Studies using visual methods are often paired with qualitative methods such as interviewing and written reflective logs and the use of multiple methods speak to diverse experiences and contribute to the philosophical belief in multiple truths ( O’Connell, 2013 ; Prosser, 2007 ; Rule & Harrell, 2010 ). The challenges in using visual methods in mixed methods research include the need to validate the methodological approach particularly in disciplines that are dominated by other methodologies, often training to use particular methods, communicating the research purpose, design and findings, and also articulating appropriate data analysis strategies ( Clark & Ivankova, 2016 ; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017 ; Pauwels, 2007 ; Shannon-Baker & Edwards, 2018 ). Research studies like Rule & Harrell, (2010) utilized visual methods primarily, but analysed visual data using qualitative methods and the integration of visual data included transformation into quantitative data for further analysis and triangulation. For O’Connell (2013) , visual methods were embedded in the qualitative research design and visual data was contextualized using other qualitative data. Here, there was integration of visual data that also included transformation into quantitative data and the construction of the case studies. The other exemplar is by Shannon-Baker & Edwards, (2018) that uses visual methods as part of an arts-based critical visual research methodology. The commonalities identified in these studies using visual methods is that firstly, participant created visual data is used and also visual data is transformed to quantitative data so that both quantitative and qualitative strategies reinforce and legitimize visual methods.

- 2.1 Realist Positivism vs Social Constructivism

The visual approach has been conventionally grounded on a realist positivist approach that looks upon visual images and data as the objective reality and to be regarded as unbiased and unmediated representations of the social world ( Ortega-Alcázar, 2012 ). Modern contemporary views challenge these assumptions and positivist epistemologies so there is currently a debate on the presumed objectivity and the unambiguity of visual data. Social constructivism takes into perspective the subjective presence of the person behind the camera who plays a crucial role in framing the image captures, the polysemic nature of visual representation and the idea that audiences are not passive consumers but also constructors of meanings and interpretations of the visual. Visual materials through the use of digital photography and videography are acknowledged to be subject to multiple interpretations and perspectives so hold no fixed or single meaning. Images and visual representations have the power construct specific visions of social class, race, and gender and can provide particular perspectives of the social world, thus having an important influence on audiences or those who consume these images.

- 2.2 Analysis and Interpretation of Visual Materials

The acknowledgement of the possible ambiguity of meaning and acknowledgment of the polysemic quality of visual representations has opened the field for the analysis of these images in various contexts including marketing materials, models, and communication to certain groups of audiences. The main methods of analysis of visual materials and data are i) content analysis ii) semiotic analysis iii) discourse analysis ( Ortega-Alcázar, 2012 ). The approach of content analysis of visual data is often a clearly defined methodological process that seeks to produce valid and replicable findings. This approach may be based on counting the frequency in which a certain element or quality appears in a defined set of images. Content analysis would then serve to provide a descriptive account of the content of a given sample set of images rather than the interpretation of various possible meanings. This may help to identify trends through image data sets and certain software applications. nvivo Ncapture for instance can work with large data sets on Facebook posts to provide this form of analysis that has a quantitative aspect in it.

The second method to the analysis of visual data is the use of semiotic analysis. This approach is grounded on the theory of Swiss linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure who proposed that the sound of speech and signs have no intrinsic meaning, but meanings are ascribed through linguistic signs that are made of the signifier and the signified. The relationships between the signifier and the signified are arbitrary. Poststructuralists challenge the concept by Saussure that once the signifier and signified are integrated to forms a sign, the sign has a fixed meaning. Poststructuralist theory and semiotics argue that meanings are not fixed but are continually being open to interpretation as signifiers are detachable from the things that are being signified. Barthes developed Saussure’s theory to argue that there are two levels of signification, denotation and connotation. The first level is the literal (denotative) and at the second level, signs can have other attached meanings (connotative).

The third form of interpretation is that of discourse analysis and stems from a critique of the realist approach to language. It claims that meaning is constituted within language and therefore language is constitutive of the social realm. Discourses are constructed from a series of related statements (both visual and textual) on a particular topic or theme and make up an authoritative language for speaking about the topic and shape the way a particular topic or issue is understood and interpreted. It does not attempt to read or analyse images but seeks to understand what the images or text claim is the ‘truth’.

- 2.3 Grounded Theory and Visual Analysis

Ethnographic research is used to document events, objects and activities of interest. This has led to a collective analysis of participant-generated images rather than researcher generated digital documentation. The site or sites of data collection may be expanded by visual participatory methods or participant representation of activities and events in spaces and places that the researcher would normally not have access to ( Hicks, 2018 ). Such visual methods may allow participants across linguistic, social and geographical divides to visually represent what may not always be visible or accessible to the researcher or audience outside the setting ( Greyson et al., 2017 ). The use of visual methods expands grounded theoretical approaches by diversifying the data that the researcher has access to. While photographs and videography may not form a wholly objective representation of reality, participant generated images help to magnify and elaborate an understanding of the social enactment of activities, interactions and relationships through a detailed and multi-faceted perspective (Croghan et al., 2008). In allowing participants, a means to portray and represent what is of priority and importance to them rather than what is important to the researcher alone. Constructivist grounded theory transpires through the understanding that meaning is co-constructed between research participant and researcher rather than merely brought into existence through an objective and neutral observer ( Charmaz, 2015 ).

3 Description of the Research Scenario

The research settings included various centres in Singapore and these were of three main types: privately owned, corporately owned and community-based early childhood centres. Although the study was based on an exploratory-sequential mixed methods design, the methodology and some of the findings shared in the context of this paper will be mostly limited to those derived from visual research methods and would not discuss the quantitative findings. The initial method used with internet-based visual data aimed to obtain a visual account of how the curriculum was enacted in the different learning environments and centre types. The priorities and commonalities in the activities and curriculum programmes in these settings were also investigated through data generation and analysis using visual research methods that included: i) internet based visual data ii) participant generated data and iii) image or photo-elicited data.

- 3.1 Internet-based Visual Data

The first stage of data generation involved social media data or essentially posts by a selection of centres. These centres were a representative sample using social media or Facebook posts over a period of 12 months. The posts that were selected fulfilled certain criteria and were images captured i) involving the children as active participants in the learning environment ii) involving both children and teachers and/or facilitators engaged in activity iii) involving children, teachers and parents involved in an event or participating in activity. It was essential to note that the learning environment was not always within the ece centre setting itself but also constituted of the environments that the class was immersed while on field trips and excursions. The constantly transforming environment within the centre itself during various festivities and celebrations was also observed and captured in the posts over the period of time.

Each social media Facebook post consisted of a cluster of photographic images capture during a particular activity or event ( Figure 1 and 2 ). In total, the sample demonstrated here were 72 such posts by five different representative early childhood education centres. Each of these main posts was coded via ground theory analysis and the distribution of frequency for each thematic code is represented in Table 1 . As coding of the visual materials is often arbitrary and often subject to personal judgment, the images were also represented by text with short bulleted points based on the visual and caption or commentary that accompanied the image (See Figure 2 ). The visual image was there also represented in text and this was also coded into the various themes.

Thematic coding with NVIVO12 Pro

Citation: Beijing International Review of Education 2, 1 (2020) ; 10.1163/25902539-00201004

- Download Figure

- Download figure as PowerPoint slide

NVIVO image-pic view of selected code

Based on the percentage distribution of the total frequency of 733, it showed that certain thematic codes ( ) were well represented in these media posts with a relative heavier emphasis of ‘Discovery of the World’ domain from the national curriculum framework curriculum or the nel framework (Nurturing Early Learners). Another inductive theme that was used was ‘Integrated MI or Multiple Intelligences’ which referred to activities that engaged more than one nel domain or two or more of the eight Gardner’s Intelligences (e.g. logical-mathematical, verbal-linguistic, naturalistic, visual-spatial, intrapersonal, interpersonal, musical, and kinesthetic). The ‘Cognitive’ domain of the nel framework was supplanted by ‘Numeracy skills’ as a great percentage of activities engaged the cognitive skillset but this was not easily specifically identified.

NVIVO Reference view of selected code

Citation: Beijing International Review of Education 2, 1 (2020) ;

Many of the posts featured in these ece social media postings featured activities that were specific to different levels such as sessions that encouraged hand-eye coordination and aesthetic expression for 3–4-year olds (Nursery 1) or more cognitively advanced activities such as projects that required higher level critical thinking and reflection with the 5–6-year olds (Kindergarten 1). Such activities emphasized the developmental appropriateness of the skills subsets required to participate actively in them. Some of these posts involved mixed age groups particularly in festive celebrations and assembly activities, these allowed the various age groups and levels to participate in them. Of the 733 frequency counts of coding, 63 counts featured community partnerships and involvement in some form of another. These community partnership activities allowed the children to experience and immerse in different learning environments including the neighborhood and community surroundings such as the fire station, community gardens, hydroponic vegetable, goat and even frog farms around the island. Experiential learning in the form of interactive, hands-on experiences is involving the senses and sometimes situated in real-life contexts as in authentic learning ( ). In learning science and mathematical concepts, the interaction with material with resultant play and creativity are noted as forms of experiential learning. Other codes that were used included activities that promoted environmental awareness (33), culturally responsive curriculum (28) and project-based learning (27).

The visual data in these thematic codes include activities and events such as gardening, outdoor field trips for environmental awareness, celebration of various festivals, racial harmony day that was an aspect of a culturally responsive curriculum. It was noted that project-based learning usually involved those four years and above as these required higher order thinking and problem-solving activities. Certain thematic codes were relatively less represented in these social media posts such as mother tongue activities although they may form a core aspect of the curriculum perhaps due to the nature of these activities which does not lend itself readily to visual representation in such media.

Participant-generated visual data may use different forms of images including photographs, video clips, artefacts, drawings and work samples, together with other forms of visual representations. In this study, teacher participants were asked to select at least three artefacts or examples of work that their students had worked or made during class activities. This appeared to be selective emphasis of the products rather than on the processes of the curriculum. There was also examples of photographs and short video clips that demonstrated the processes of the curriculum and what was important or of priority to the teacher participants themselves. It was found to be very effective in communicating the processes in the curriculum through photo documentation series with explanatory texts accompanying these.

Planning learning spaces

Citation: Beijing International Review of Education 2, 1 (2020) ;

Photographs that are generated research contexts are often a product of the network of relations between the participant, the researcher and the audience/s and the debate ensues that there should be not one meaning ascribed, but the possibility of multiple interpretations and meanings that could evolve over time or remain relative unchanging. The meaning could also be a co-construction between participant and researcher ( ).

Learning about the food pyramid and a balanced meal

Citation: Beijing International Review of Education 2, 1 (2020) ;

In some instances, the photographs themselves present a visual narrative even without further explanation from the individual participant or interpretation from the researcher. Although not shared by all researchers, Sarah is particular about practices that subordinate the visual image to the written word in research. assert that a robust visual analytic process incorporates both the participant and researcher voices, while relating these various layers of perspective and statements made so as to demonstrate the emerging analytical narrative that may become emphasized or diminished based on the overall research direction and objectives. They point out three stages to interpretative visual analysis and meaning making when using participant-generated visual material although not all analysis passes through all three stages. The first stage is that of meaning making through the engagement of the participant and image production. This stage of analysis engages mainly with the stories, experiences and representations that participants wish the researchers to know about through the participant’s reflections on the visual material generated and the participant guides the way they feel the visual material should be interpreted. The second stage of the interpretative process involves a closer examination of the visual materials and that of the participant’s explanations. The researcher’s reflections on these facilitates the forming of themes and the interconnections between these themes, the context in which these visual materials were generated, together with other details will provide further interpretation of the participant’s reflections. This could also include the participant’s interview responses on further probing and inquiry into the participant’s interpretation or processes. Stage process refers to meaning making through re-contextualization within the theoretical and conceptual frameworks to define and identify the emerging analytic patterns. This stage allows a more final and defined robust analytic explanation.

The visual research method used here refers to the use of images, photographs, drawings or other work samples or artefacts from the teacher participants themselves or from the students in their class ( ). In some instances, participants were specifically given the equipment to capture the images that were used at a later stage for stimulating discussion and reflection (Croghan et al., 2008; ). Both researcher and participant-generated visual data was also often used in a photo-elicited semi-structured interview setting. However, not just direct participant-generated images but also work samples and artefacts from their classrooms, particularly when direct field observations were not always possible in elucidating the processes of creation and generation of the artefacts. Banks, (2007) elaborates on photo-elicitation by itself and refers to it as involving photographs to invoke memories, comments and discussion during the course of semi-structured interview. The visual material may be participant-generated as mentioned in the earlier section, directly or indirectly or it may be researcher generated photographs or digital video clips. The framing of the visuals may demonstrate certain examples of inter-relationship and social interactions and provide a detail of the cultural context of the activity or event represented. These may provide the basis for discussion and elaboration of the abstraction, trigger details, and focus during the process.

The supermarket in the neighbourhood

Citation: Beijing International Review of Education 2, 1 (2020) ;

Perhaps what is missing in this context are the children’s direct voices and their own meaning-making through their work. As the dialogue with the teacher participants sometimes, takes place a period after the creation of their artwork and there was insufficient opportunity to take the time to dialogue directly with the children but rather to learn about the process through the teacher participants’ perspective at this stage. The meaning-making process here considers mainly the interpretation of the teacher and the researcher. The fact is that images should be acknowledged to be multi-vocal, having the ability to ‘speak’ to different audiences in a variety of contexts ( ; ).

In current times, digital media has reached into our mundane everyday existences, most obviously through the cell phone and modern-day gadgets, social media and these digital artefacts have engendered new forms of ethnographic enquiry. One of these includes what might be termed as the cultural politics of media and examines cultural identities, representations and imaginaries ( ). Fleer & Ridgway, (2014) outline and frame visual narrative data based on cultural-historical theory. Cultural historical theory acknowledges that the characteristics of individuals engaged in activities and interactions within a certain cultural setting can evolve and transform over a period of history. This can enable the researcher a better understanding on why certain practices and needs are defined as they are in a specific context and that different perspectives and priorities are taken in different cultures and times ( ; ).

Though field observation, particularly in Reggio-Emilia inspired centres and where children are given free reign of their imagination through encouragement and access to materials, it has been observed that the young can use the graphic and expressive languages of drawing, painting, collage and construction to record their ideas, observations, reflections, memories to further explore their understanding. Embedded in these activities are the processes of reconstructing and building on earlier knowledge so as to externalize their thoughts and what is learnt, to share their worlds with their peers and others ( ; ). The approach using ‘art as epistemology’ ( ) so that art experiences in the classroom can have both communicative and expressive goals, and the concept of art as a symbolic language is the subject of much debate. This highlights the potential of teachers facilitating children to develop the capacity in the ‘hundred language’ that is accessible to them so as to master the range of instruments and symbols ( ) that form the visual culture and an expressive language used in the curriculum. The potential for research based on visual methodologies is thus boundless.

I would like to thank niec, National Institute of Early Childhood Development, Singapore and the following teacher participant contributors Chandra Rai, Shauna Chen and Kavita Mogan.

, M. (2007). Visual methods and field research. In , 58–91. SAGE. . , ( ). . In , – . SAGE. .)| false , M. (2011). Presenting visual research. In , 105–128. SAGE. 10.4135/9781526445933.n5.

, ( ). . In , – . SAGE. 10.4135/9781526445933.n5.)| false , U. , & Morris, P. A. (2006). The Bio ecological Model of Human Development. In . John Wiley.

, , & , ( ). . In . John Wiley.)| false , K. (2015). (Second Ed, Vol. ). Elsevier.

, ( ). (Second Ed, Vol. ). Elsevier.)| false , V. L. P. , & Ivankova, N. V. (2016). How to Expand the use of Mixed Methods Research?: Intersecting Mixed Methods with Other Approaches. In , 135–160.

, , & , ( ). . In , – .)| false , E. G. (2010). . . , ( ). . .)| false , J. , & Plano Clark, V. (2017). . (Third, Ed.). SAGE. , , & , ( ). . (Third, Ed.). SAGE.)| false , R. , Griffin, C. , Hunter, J. , & Phoenix, A. (2008). Young people’s constructions of self: Notes on the use and analysis of the photo-elicitation methods. , (4), 345–356. .

, , , , , , & , ( ). . , ( ), – . .)| false , R. , Griffin, C. , Hunter, J. , & Phoenix, A. (2008). Young people’s constructions of self: Notes on the use and analysis of the photo-elicitation methods. , (4), 345–356. . , , , , , , & , ( ). . , ( ), – . .)| false , K. (2009). The Environment as Third Teacher: Pre-service Teacher’s Aesthetic Transformation of an Art Learning Environment for Young Children in a Museum Setting. , (1), 1–17. , ( ). . , ( ), – .)| false , N. K. (2012). Triangulation 2.0*. , (2), 80–88. . , ( ). , ( ), – . .)| false , S. , & Guillemin, M. (2014). From photographs to findings: visual meaning-making and interpretive engagement in the analysis of participant-generated images. , (1), 54–67. . , , & , ( ). . , ( ), – . .)| false , L. , Hallett, F. , Kay, V. , & Woodhouse, C. (2017). . . , , , , , , & , ( ). . .)| false , T. S. (2013). (3rd Edt). Oxford University Press. , ( ). (3rd Edt). Oxford University Press.)| false , M. , & Ridgway, A. (2014). . .