Advisory boards aren’t only for executives. Join the LogRocket Content Advisory Board today →

- Product Management

- Solve User-Reported Issues

- Find Issues Faster

- Optimize Conversion and Adoption

Understanding group dynamics: Definition, theory, and examples

Unless you’re a writer who self-publishes, there’s a good chance you need to rely on others to accomplish anything in your role. Your colleagues support you, provide you with information, and play their part. Product managers never work in isolation.

You might be a member of a group, or even the leader, but regardless, working in a group comes with a unique set of challenges and expectations. Because of this, understanding group dynamics is essential for achieving the best results for your product.

In this article, you will learn what group dynamics are, how groups form, and the challenges that may arise.

What are group dynamics?

Group dynamics are the behaviors and psychological dimensions that occur between or within a social group. These refer to the roles individuals play in social settings and the way that they interact, cooperate, and compete with each other.

Understanding group dynamics allows you to better understand your team and maximize its potential.

There are a range of different groups you might belong to. These are some of the most common:

- Product group — The collection of product people working within the same organization and driving product-focused activities. This might include chief product officers, lead product managers, product managers, and product owners

- Scrum / delivery group — People tasked with getting product changes through the process and out of the door to end users. Often, these are scrum masters, software engineers, tech leads, QA, and designers

- Management group — Strategic decision makers who determine the direction of future activities. Normally these are department heads or C-suite members

- Colleague group — An informal collection of people you work alongside who share common interests, but without the formal structure of some of the other groups

Tuckman’s stages of group development (forming, norming, storming, performing)

Group formation refers to the roles and interaction that individuals undertake to bring people together into a coherent group.

This process was first described by Bruce Truckman in his 1965 publication “ Developmental Sequence in Small Groups ,” where he described the phases of group development in four distinct phases:

Imagine you are hired to join a start-up that’s just beginning its first product development journey. On day one you walk into the office and are faced with a founder, a designer, and an engineer. You are now part of this new group and the start of the journey to launching your new product requires your group to come together and start working on the MVP .

This initial period involves the group aligning around the overall goals for the product (both long-term and short-term), including some guidance from the founder on the vision and discussions from the group on what might be possible and when.

At this stage, the group is new, so individuals are typically understanding and polite with each other. Trust between members hasn’t been developed yet and there are fewer arguments among members, as individuals are cautious and aware of how they will be perceived and fit within the group.

2. Storming

Once your start-up group has a defined MVP and is working on a plan for its delivery, the group progresses together and trust has been developed between members. Now there’s a more secure environment where individuals can express their opinions. This can result in some degree of conflict.

For example, the founder could be insistent on the delivery of a feature in the MVP, which is countered by the engineer pushing back due to its initial complexity. This interaction between two members of the group doesn’t just impact those two members.

Over 200k developers and product managers use LogRocket to create better digital experiences

The nature of the group means that the remaining members are also involved, trying to determine where the power in the group lies, how they’re expected to react to this disagreement, and what it might mean for them going forward.

Time progresses and now your start-up group works through any potential conflict and assumes roles and responsibilities for how they approach all aspects of group activity. This enables you to develop conventions of operation that support movement towards the agreed goal. Individuals can now make decisions on how they need to behave within the group to ensure that the goal is reached.

4. Performing

As you continue delivering on the goal and approach the launch of the MVP you are motivated and clear on what you need to do in order to get the product released. By this time, everyone in the group knows their role and can make autonomous decisions that keep everything moving in the right direction towards delivering the MVP release.

5 challenges groups face

Following the journey of your start-up team, you’d think everything was smooth sailing and the group got together, figured out what to do, and got on with it. However, the challenge with groups is that they involve multiple individuals and the dynamics between these members can have a real impact on the success of the group.

There are a range of challenges within a group including:

Lack of creativity

In early-stage groups, it’s common for there to be a lack of trust between team members. This happens because you put individuals together who don’t know each other, who haven’t worked together, and who don’t know what to expect from each other.

A popular way to address this is to promote team-building activities that can foster a level of trust and understanding that can then be transferred from the activity to the workplace. Think about paint-balling, sailing, or orienteering. These exercises provide a safe space for some of the forming and norming to occur outside of the main task at hand, but allow for growth in relationships and importantly trust.

With individual tasks, you only have yourself to consider and it’s clear that the results will likely reflect the effort you put in. On the other hand, In a group setting there can be an imbalance in effort that has a negative impact on the group’s performance.

If your start-up founder sets the goal and then disappears until delivery day, the team will think that the founder’s effort doesn’t match that of the team and frustration can ensue. You might overhear team members saying, “Why should I put in so much effort if others in the team don’t bother?” Once you’re at this point, the team needs to realign and provide more clarity on the expectations of its members.

Continuing from the example, if the designer comes up with a new design for a particular feature and presents it to the group, the group might accept the design without any serious feedback. The group knows they need to move forward and remain to date. However, challenging and providing critical feedback is key to pushing groups forward toward delivering better solutions.

If your group is too comfortable they won’t push the boundaries, so it’s important for there to be an opportunity to challenge and question the possibilities. Encourage an innovation culture led by constructive criticism .

If you give a group too much freedom they can splinter off in different directions, while, with too little autonomy a group can feel as if they aren’t invested in the group and are just cogs in the machine. You need to strike a balance between setting clear goals and providing opportunities for them to develop their own solutions.

Depending on the size of your group, the ability for sub-groups to form introduces risks to the performance of the overall group. Different dynamics will start to appear within the sub-groups that can derail the wider dynamics.

The exclusion of some group members from a sub-group (whether intentionally or not) might negatively impact trust or increase frustrations, and sub-groups might develop different goals that don’t fully align with the core group’s goals.

Group roles

Ultimately, the strongest groups are the ones where roles and responsibilities are clear. This supports the movement toward a common goal. However, when we’re talking about roles here we aren’t talking about job titles.

Within any group, there are task-based, procedural, and social roles to play in order for the group to achieve the team goals that include:

- Coach — Someone who provides support to individuals throughout the project, helping team members deliver the best of themselves

- Compromiser — The person who helps the team achieve their goals by finding a path through any challenges put in their path

- Coordinator — This role involves getting people together for discussions, keeping records of decisions, and providing clarity on activities. Without coordination, groups can go off in different directions

- Critic — Someone who is prepared to question approaches, decisions, and actions in order to ensure that the path is the right one

- Facilitator — The person who brings people together, makes sure roles and goals are clear, and ensures that the team are equipped to deliver

- Initiator — Someone who is always looking to find new solutions or encourage actionIf you think back to a time when you were working in a team you will likely be able to identify times when you’ve played all of these roles. You could have been a coach to the intern who needed support in finding their voice, or a critic of a proposed approach.

Assessing your own groups

Now that you’ve seen some of the factors that influence the dynamics within a group, take the time to understand how your groups are performing by asking yourself these questions:

- Does your group know its goals and how it’s performing against them?

- Do they feel like there are common goals that they own?

- If your group goes off course, how does it get back on track?

- Does your group challenge each other in a positive way?

- Do members feel like they can share their views with the group?

- How can members share their concerns or frustrations?

- Does your team learn from its mistakes?

You might answer yes to some of these and no to others, but the important thing is to be honest so that you can take steps as a group to address areas of improvement.

Teams are organic. The dynamics of a group are constantly evolving, with the changing of team members and the phase of work. Good teams will adapt and continue to work toward their common goal.

The important thing to remember is that groups need attention and nurturing.

If you’re struggling with a group, don’t assume that everyone understands group dynamics or has the skills to operate effectively within a group environment. Instead, lean on Tuckman’s stages of group development to understand what stage of development your team is at. Also keep in mind the major challenges that groups face and try to mitigate them as much as possible.

LogRocket generates product insights that lead to meaningful action

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- #collaboration and communication

- #project management

Stop guessing about your digital experience with LogRocket

Recent posts:.

How PMs can best work with UX designers

With a well-built collaborative working environment you can successfully deliver customer centric products.

Leader Spotlight: Evaluating data in aggregate, with Christina Trampota

Christina Trampota shares how looking at data in aggregate can help you understand if you are building the right product for your audience.

What is marketing myopia? Definition, causes, and solutions

Combat marketing myopia by observing market trends and by allocating sufficient resources to research, development, and marketing.

Leader Spotlight: How features evolve from wants to necessities, with David LoPresti

David LoPresti, Director, U-Haul Apps at U-Haul, talks about how certain product features have evolved from wants to needs.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6.2 Group Dynamics and Behavior

Learning objectives.

- Explain how and why group dynamics change as groups grow in size.

- Describe the different types of leaders and leadership styles.

- Be familiar with experimental evidence on group conformity.

- Explain how groupthink develops and why its development may lead to negative consequences.

Social scientists have studied how people behave in groups and how groups affect people’s behavior, attitudes, and perceptions (Gastil, 2009). Their research underscores the importance of groups for social life, but it also points to the dangerous influence groups can sometimes have on their members.

The Importance of Group Size

The distinction made earlier between small primary groups and larger secondary groups reflects the importance of group size for the functioning of a group, the nature of its members’ attachments, and the group’s stability. If you have ever taken a very small class, say fewer than 15 students, you probably noticed that the class atmosphere differed markedly from that of a large lecture class you may have been in. In the small class, you were able to know the professor better, and the students in the room were able to know each other better. Attendance in the small class was probably more regular than in the large lecture class.

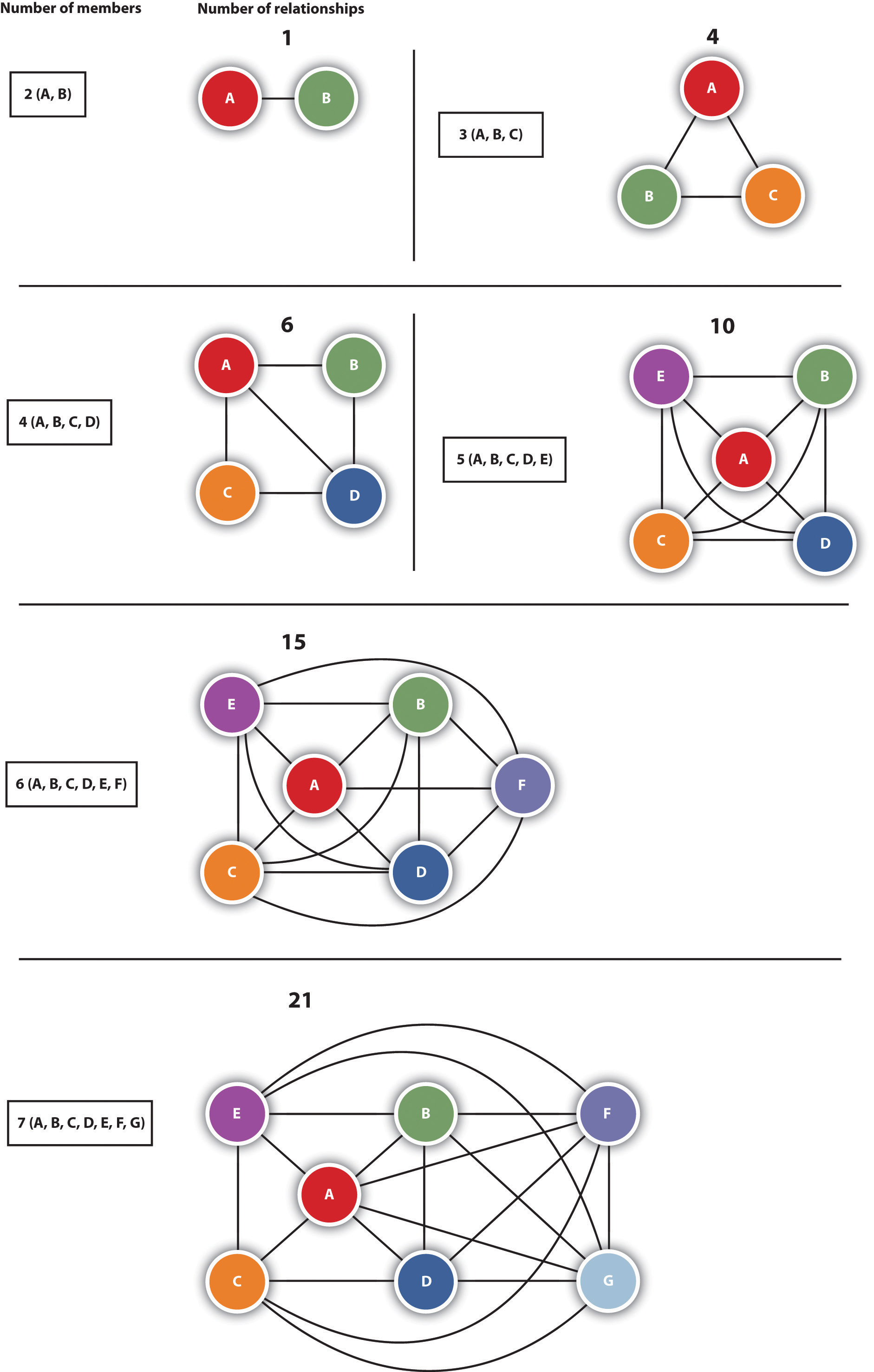

Over the years, sociologists and other scholars have studied the effects of group size on group dynamics. One of the first to do so was German sociologist Georg Simmel (1858–1918), who discussed the effects of groups of different sizes. The smallest group, of course, is the two-person group, or dyad , such as a married couple or two people engaged to be married or at least dating steadily. In this smallest of groups, Simmel noted, relationships can be very intense emotionally (as you might know from personal experience) but also very unstable and short lived: if one person ends the relationship, the dyad ends as well.

The smallest group is the two-person group, or dyad. Dyad relationships can be very intense emotionally but also unstable and short lived. Why is this so?

erin m – 2 couples – CC BY-NC 2.0.

A triad , or three-person group, involves relationships that are still fairly intense, but it is also more stable than a dyad. A major reason for this, said Simmel, is that if two people in a triad have a dispute, the third member can help them reach some compromise that will satisfy all the triad members. The downside of a triad is that two of its members may become very close and increasingly disregard the third member, reflecting the old saying that “three’s a crowd.” As one example, some overcrowded college dorms are forced to house students in triples, or three to a room. In such a situation, suppose that two of the roommates are night owls and like to stay up very late, while the third wants lights out by 11:00 p.m. If majority rules, as well it might, the third roommate will feel very dissatisfied and may decide to try to find other roommates.

As groups become larger, the intensity of their interaction and bonding decreases, but their stability increases. The major reason for this is the sheer number of relationships that can exist in a larger group. For example, in a dyad only one relationship exists, that between the two members of the dyad. In a triad (say composed of members A, B, and C), three relationships exist: A-B, A-C, and B-C. In a four-person group, the number of relationships rises to six: A-B, A-C, A-D, B-C, B-D, and C-D. In a five-person group, 10 relationships exist, and in a seven-person group, 21 exist (see Figure 6.2 “Number of Two-Person Relationships in Groups of Different Sizes” ). As the number of possible relationships rises, the amount of time a group member can spend with any other group member must decline, and with this decline comes less intense interaction and weaker emotional bonds. But as group size increases, the group also becomes more stable because it is large enough to survive any one member’s departure from the group. When you graduate from your college or university, any clubs, organizations, or sports teams to which you belong will continue despite your exit, no matter how important you were to the group, as the remaining members of the group and new recruits will carry on in your absence.

Figure 6.2 Number of Two-Person Relationships in Groups of Different Sizes

Group Leadership and Decision Making

Most groups have leaders. In the family, of course, the parents are the leaders, as much as their children sometimes might not like that. Even some close friendship groups have a leader or two who emerge over time. Virtually all secondary groups have leaders. These groups often have a charter, operations manual, or similar document that stipulates how leaders are appointed or elected and what their duties are.

Sociologists commonly distinguish two types of leaders, instrumental and expressive. An instrumental leader is a leader whose main focus is to achieve group goals and accomplish group tasks. Often instrumental leaders try to carry out their role even if they alienate other members of the group. The second type is the expressive leader , whose main focus is to maintain and improve the quality of relationships among group members and more generally to ensure group harmony. Some groups may have both types of leaders.

Related to the leader types is leadership style . Three such styles are commonly distinguished. The first, authoritarian leadership , involves a primary focus on achieving group goals and on rigorous compliance with group rules and penalties for noncompliance. Authoritarian leaders typically make decisions on their own and tell other group members what to do and how to do it. The second style, democratic leadership , involves extensive consultation with group members on decisions and less emphasis on rule compliance. Democratic leaders still make the final decision but do so only after carefully considering what other group members have said, and usually their decision will agree with the views of a majority of the members. The final style is laissez-faire leadership . Here the leader more or less sits back and lets the group function on its own and really exerts no leadership role.

When a decision must be reached, laissez-faire leadership is less effective than the other two in helping a group get things done. Whether authoritarian or democratic leadership is better for a group depends on the group’s priorities. If the group values task accomplishment more than anything else, including how well group members get along and how much they like their leader, then authoritarian leadership is preferable to democratic leadership, as it is better able to achieve group goals quickly and efficiently. But if group members place their highest priority on their satisfaction with decisions and decision making in the group, then they would want to have a lot of input in decisions. In this case, democratic leadership is preferable to authoritarian leadership.

Some small groups shun leadership and instead try to operate by consensus . In this model of decision making popularized by Quakers (T. S. Brown, 2009), no decision is made unless all group members agree with it. If even one member disagrees, the group keeps discussing the issue until it reaches a compromise that satisfies everyone. If the person disagreeing does not feel very strongly about the issue or does not wish to prolong the discussion, she or he may agree to “stand aside” and let the group make the decision despite the lack of total consensus. But if this person refuses to stand aside, no decision may be possible.

Some small groups operate by consensus instead of having a leader guiding or mandating their decision making. This model of decision making was popularized by the Society of Friends (Quakers).

John – All Are Welcome – CC BY 2.0.

A major advantage of the consensus style of decision making is psychic. Because everyone has a chance to voice an opinion about a potential decision, and no decisions are reached unless everyone agrees with them, group members will ordinarily feel good about the eventual decision and also about being in the group. The major disadvantage has to do with time and efficiency. When groups operate by consensus, their discussions may become long and tedious, as no voting is allowed and discussion must continue until everyone is satisfied with the outcome. This means the group may well be unable to make decisions quickly and efficiently.

One final issue is how gender influences leadership styles. Although the evidence indicates that women and men are equally capable of being good leaders, their leadership styles do tend to differ. Women are more likely to be democratic leaders, while men are more likely to be authoritarian leaders (Eagly & Carli, 2007). Because of this difference, women leaders sometimes have trouble securing respect from their subordinates and are criticized for being too soft. Yet if they respond with a more masculine, or authoritarian, style, they may be charged with acting too much like a man and be criticized in ways a man would not be.

Groups, Roles, and Conformity

We have seen in this and previous chapters that groups are essential for social life, in large part because they play an important part in the socialization process and provide emotional and other support for their members. As sociologists have emphasized since the origins of the discipline during the 19th century, the influence of groups on individuals is essential for social stability. This influence operates through many mechanisms, including the roles that group members are expected to play. Secondary groups such as business organizations are also fundamental to complex industrial societies such as our own.

Social stability results because groups induce their members to conform to the norms, values, and attitudes of the groups themselves and of the larger society to which they belong. As the chapter-opening news story about teenage vandalism reminds us, however, conformity to the group, or peer pressure, has a downside if it means that people might adopt group norms, attitudes, or values that are bad for some reason to hold and may even result in harm to others. Conformity is thus a double-edged sword. Unfortunately, bad conformity happens all too often, as several social-psychological experiments, to which we now turn, remind us.

Solomon Asch and Perceptions of Line Lengths

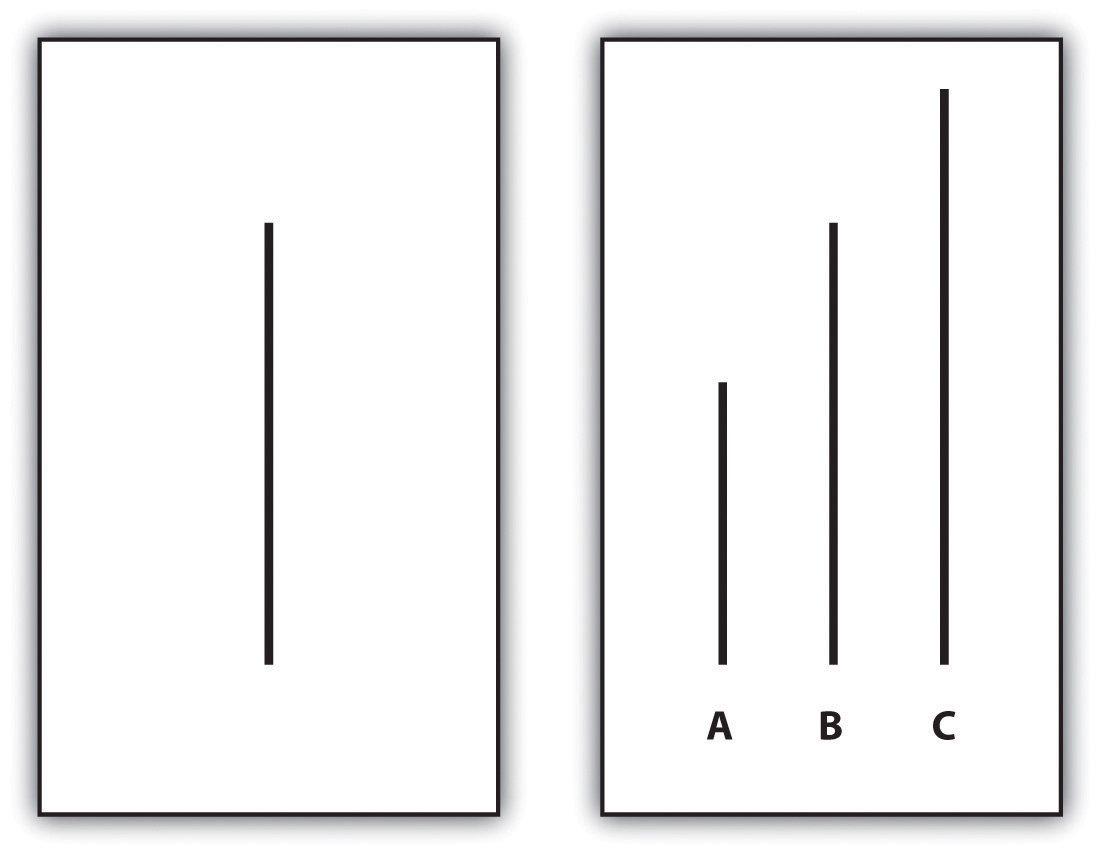

Several decades ago Solomon Asch (1958) conducted one of the first of these experiments. Consider the pair of cards in Figure 6.3 “Examples of Cards Used in Asch’s Experiment” . One of the lines (A, B, or C) on the right card is identical in length to the single line in the left card. Which is it? If your vision is up to par, you undoubtedly answered Line B. Asch showed several students pairs of cards similar to the pair in Figure 6.3 “Examples of Cards Used in Asch’s Experiment” to confirm that it was very clear which of the three lines was the same length as the single line.

Figure 6.3 Examples of Cards Used in Asch’s Experiment

Next, he had students meet in groups of at least six members and told them he was testing their visual ability. One by one he asked each member of the group to identify which of the three lines was the same length as the single line. One by one each student gave a wrong answer. Finally, the last student had to answer, and about one-third of the time the final student in each group also gave the wrong answer that everyone else was giving.

Unknown to these final students, all the other students were confederates or accomplices, to use some experimental jargon, as Asch had told them to give a wrong answer on purpose. The final student in each group was thus a naive subject, and Asch’s purpose was to see how often the naive subjects in all the groups would give the wrong answer that everyone else was giving, even though it was very clear it was a wrong answer.

After each group ended its deliberations, Asch asked the naive subjects who gave the wrong answers why they did so. Some replied that they knew the answer was wrong but they did not want to look different from the other people in the group, even though they were strangers before the experiment began. But other naive subjects said they had begun to doubt their own visual perception : they decided that if everyone else was giving a different answer, then somehow they were seeing the cards incorrectly.

Asch’s experiment indicated that groups induce conformity for at least two reasons. First, members feel pressured to conform so as not to alienate other members. Second, members may decide their own perceptions or views are wrong because they see other group members perceiving things differently and begin to doubt their own perceptive abilities. For either or both reasons, then, groups can, for better or worse, affect our judgments and our actions.

Stanley Milgram and Electric Shock

Although the type of influence Asch’s experiment involved was benign, other experiments indicate that individuals can conform in a very harmful way. One such very famous experiment was conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram (1974), who designed it to address an important question that arose after World War II and the revelation of the murders of millions of people during the Nazi Holocaust. This question was, “How was the Holocaust possible?” Many people blamed the authoritarian nature of German culture and the so-called authoritarian personality that it inspired among German residents, who, it was thought, would be quite ready to obey rules and demands from authority figures.

Milgram wanted to see whether Germans would indeed be more likely than Americans to obey unjust authority. He devised a series of experiments and found that his American subjects were quite likely to give potentially lethal electric shocks to other people. During the experiment, a subject, or “teacher,” would come into a laboratory and be told by a man wearing a white lab coat to sit down at a table housing a machine that sent electric shocks to a “learner.” Depending on the type of experiment, this was either a person whom the teacher never saw and heard only over a loudspeaker, a person sitting in an adjoining room whom the teacher could see through a window and hear over the loudspeaker, or a person sitting right next to the teacher.

The teacher was then told to read the learner a list of word pairs, such as mother-father, cat-dog, and sun-moon. At the end of the list, the teacher was then asked to read the first word of the first word pair—for example, “mother” in our list—and to read several possible matches. If the learner got the right answer (“father”), the teacher would move on to the next word pair, but if the learner gave the wrong answer, the teacher was to administer an electric shock to the learner. The initial shock was 15 volts (V), and each time a wrong answer was given, the shock would be increased, finally going up to 450 V, which was marked on the machine as “Danger: Severe Shock.” The learners often gave wrong answers and would cry out in pain as the voltage increased. In the 200-V range, they would scream, and in the 400-V range, they would say nothing at all. As far as the teachers knew, the learners had lapsed into unconsciousness from the electric shocks and even died. In reality, the learners were not actually being shocked. Instead, the voice and screams heard through the loudspeaker were from a tape recorder, and the learners that some teachers saw were only pretending to be in agony.

Before his study began, Milgram consulted several psychologists, who assured him that no sane person would be willing to administer lethal shock in his experiments. He thus was shocked (pun intended) to find that more than half the teachers went all the way to 450 V in the experiments, where they could only hear the learner over a loudspeaker and not see him. Even in the experiments where the learner was sitting next to the teacher, some teachers still went to 450 V by forcing a hand of the screaming, resisting, but tied-down learner onto a metal plate that completed the electric circuit.

Milgram concluded that people are quite willing, however reluctantly, to obey authority even if it means inflicting great harm on others. If that could happen in his artificial experiment situation, he thought, then perhaps the Holocaust was not so incomprehensible after all, and it would be too simplistic to blame the Holocaust just on the authoritarianism of German culture. Instead, perhaps its roots lay in the very conformity to roles and group norms that makes society possible in the first place. The same processes that make society possible may also make tragedies like the Holocaust possible.

The Third Wave

In 1969, concern about the Holocaust prompted Ron Jones, a high school teacher from Palo Alto, California, to conduct a real-life experiment that reinforced Milgram’s findings by creating a Nazi-like environment in the school in just a few short days (Jones, 1979). He began by telling his sophomore history class about the importance of discipline and self-control. He had his students sit at attention and repeatedly stand up and sit down in quiet unison and saw their pride as they accomplished this task efficiently. All of a sudden everyone in the class seemed to be paying rapt attention to what was going on.

The next day, Jones began his class by talking about the importance of community and of being a member of a team or a cause. He had his class say over and over, “Strength through discipline, strength through community.” Then he showed them a new class salute, made by bringing the right hand near the right shoulder in a curled position. He called it the Third Wave salute, because a hand in this position resembled a wave about to topple over. Jones then told the students they had to salute each other outside the classroom, which they did so during the next few days. As word of what was happening in Jones’s class spread, students from other classes asked if they could come into his classroom.

On the third day of the experiment, Jones gave membership cards to every student in his class, which had now gained several new members. He told them they had to turn in the name of any student who was disobeying the class’s rules. He then talked to them about the importance of action and hard work, both of which enhanced discipline and community. Jones told his students to recruit new members and to prevent any student who was not a Third Wave member from entering the classroom. During the rest of the day, students came to him with reports of other students not saluting the right way or of some students criticizing the experiment. Meanwhile, more than 200 students had joined the Third Wave.

On the fourth day of the experiment, more than 80 students squeezed into Jones’s classroom. Jones informed them that the Third Wave was in fact a new political movement in the United States that would bring discipline, order, and pride to the country and that his students were among the first in the movement. The next day, Jones said, the Third Wave’s national leader, whose identity was still not public, would be announcing a grand plan for action on national television at noon.

At noon the next day, more than 200 students crowded into the school auditorium to see the television speech. When Jones gave them the Third Wave salute, they saluted back. They chanted, “Strength through discipline, strength through community,” over and over, and then sat in silent anticipation as Jones turned on a large television in front of the auditorium. The television remained blank. Suddenly Jones turned on a movie projector and showed scenes from a Nazi rally and the Nazi death camps. As the crowd in the auditorium reacted with shocked silence, the teacher told them there was no Third Wave movement and that almost overnight they had developed a Nazi-like society by allowing their regard for discipline, community, and action to warp their better judgment. Many students in the auditorium sobbed as they heard his words.

The Third Wave experiment was designed to help high school students in Palo Alto, California, understand how the Nazi Holocaust (represented by this photo of the Auschwitz concentration camp) could have happened. The experiment illustrated that normal group processes that make social life possible can also lead people to conform to objectionable standards.

George Olcott – Auschwitz Fence – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The Third Wave experiment once again indicates that the normal group processes that make social life possible also can lead people to conform to standards—in this case fascism—that most of us would reject. It also helps us understand further how the Holocaust could have happened. As Jones (1979, pp. 509–10) told his students in the auditorium, “You thought that you were the elect. That you were better than those outside this room. You bargained your freedom for the comfort of discipline and superiority. You chose to accept the group’s will and the big lie over your own conviction.…Yes, we would all have made good Germans.”

Zimbardo’s Prison Experiment

In 1971, Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo (1972) conducted an experiment to see what accounts for the extreme behaviors often seen in prisons: does this behavior stem from abnormal personalities of guards and prisoners or, instead, from the social structure of prisons, including the roles their members are expected to play? His experiment remains a compelling illustration of how roles and group processes can prompt extreme behavior.

Zimbardo advertised for male students to take part in a prison experiment and screened them out for histories of mental illness, violent behavior, and drug use. He then assigned them randomly to be either guards or prisoners in the experiment to ensure that any behavioral differences later seen between the two groups would have to stem from their different roles and not from any preexisting personality differences had they been allowed to volunteer.

The guards were told that they needed to keep order. They carried no weapons but did dress in khaki uniforms and wore reflector sunglasses to make eye contact impossible. On the first day of the experiment, the guards had the prisoners, who wore gowns and stocking caps to remove their individuality, stand in front of their cells (converted laboratory rooms) for the traditional prison “count.” They made the prisoners stand for hours on end and verbally abused those who complained. A day later the prisoners refused to come out for the count, prompting the guards to respond by forcibly removing them from their cells and sometimes spraying them with an ice-cold fire extinguisher to expedite the process. Some prisoners were put into solitary confinement. The guards also intensified their verbal abuse of the prisoners.

By the third day of the experiment, the prisoners had become very passive. The guards, several of whom indicated before the experiment that they would have trouble taking their role seriously, now were quite serious. They continued their verbal abuse of the prisoners and became quite hostile if their orders were not followed exactly. What had begun as somewhat of a lark for both guards and prisoners had now become, as far as they were concerned, a real prison.

Shortly thereafter, first one prisoner and then a few more came down with symptoms of a nervous breakdown. Zimbardo and his assistants could not believe this was possible, as they had planned for the experiment to last for two weeks, but they allowed the prisoners to quit the experiment. When the first one was being “released,” the guards had the prisoners chant over and over that this prisoner was a bad prisoner and that they would be punished for his weakness. When this prisoner heard the chants, he refused to leave the area because he felt so humiliated. The researchers had to remind him that this was only an experiment and that he was not a real prisoner. Zimbardo had to shut down the experiment after only six days.

Zimbardo (1972) later observed that if psychologists had viewed the behaviors just described in a real prison, they would likely have attributed them to preexisting personality problems in both guards and prisoners. As already noted, however, his random assignment procedure invalidated this possibility. Zimbardo thus concluded that the guards’ and prisoners’ behavioral problems must have stemmed from the social structure of the prison experience and the roles each group was expected to play. Zimbardo (2008) later wrote that these same processes help us understand “how good people turn evil,” to cite the subtitle of his book, and thus help explain the torture and abuse committed by American forces at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq after the United States invaded and occupied that country in 2003. Once again we see how two of the building blocks of social life—groups and roles—contain within them the seeds of regrettable behavior and attitudes.

Groupthink may prompt people to conform with the judgments or behavior of a group because they do not want to appear different. Because of pressures to reach a quick verdict, jurors may go along with the majority opinion even if they believe otherwise. Have you ever been in a situation where groupthink occurred?

Brian DeWitt – Wolf Law Courtroom – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

As these examples suggest, sometimes people go along with the desires and views of a group against their better judgments, either because they do not want to appear different or because they have come to believe that the group’s course of action may be the best one after all. Psychologist Irving Janis (1972) called this process groupthink and noted it has often affected national and foreign policy decisions in the United States and elsewhere. Group members often quickly agree on some course of action without thinking completely of alternatives. A well-known example here was the decision by President John F. Kennedy and his advisers in 1961 to aid the invasion of the Bay of Pigs in Cuba by Cuban exiles who hoped to overthrow the government of Fidel Castro. Although several advisers thought the plan ill advised, they kept quiet, and the invasion was an embarrassing failure (Hart, Stern, & Sundelius, 1997).

Groupthink is also seen in jury decision making. Because of the pressures to reach a verdict quickly, some jurors may go along with a verdict even if they believe otherwise. In juries and other small groups, groupthink is less likely to occur if at least one person expresses a dissenting view. Once that happens, other dissenters feel more comfortable voicing their own objections (Gastil, 2009).

Key Takeaways

- Leadership in groups and organizations involves instrumental and expressive leaders and several styles of leadership.

- Several social-psychological experiments illustrate how groups can influence the attitudes, behavior, and perceptions of their members. The Milgram and Zimbardo experiments showed that group processes can produce injurious behavior.

For Your Review

- Think of any two groups to which you now belong or to which you previously belonged. Now think of the leader(s) of each group. Were these leaders more instrumental or more expressive? Provide evidence to support your answer.

- Have you ever been in a group where you or another member was pressured to behave in a way that you considered improper? Explain what finally happened.

Asch, S. E. (1958). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In E. E. Maccoby, T. M. Newcomb, & E. L. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in social psychology . New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Brown, T. S. (2009). When friends attend to business . Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. Retrieved from http://www.pym.org/pm/comments.php?id=1121_0_178_0_C .

Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. (2007). Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders . Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Gastil, J. (2009). The group in society . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hart, P. T., Stern E. K., & Sundelius B., (Eds.). (1997). Beyond groupthink: Political group dynamics and foreign policy-making . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Jones, R. (1979). The third wave: A classroom experiment in fascism. In J. J. Bonsignore, E. Karsh, P. d’Errico, R. M. Pipkin, S. Arons, & J. Rifkin (Eds.), Before the law: An introduction to the legal process (pp. 503–511). Dallas, TX: Houghton Mifflin.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority . New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Zimbardo, P. G. (2008). The Lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil . New York, NY: Random House Trade Paperbacks.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1972). Pathology of imprisonment. Society, 9 , 4–8.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

8.2 Group Dynamics

Learning objectives.

- Understand the difference between informal and formal groups.

- Learn the stages of group development.

- Identify examples of the punctuated equilibrium model.

- Learn how group cohesion affects groups.

- Learn how social loafing affects groups.

- Learn how collective efficacy affects groups.

Types of Groups: Formal and Informal

What is a group ? A group is a collection of individuals who interact with each other such that one person’s actions have an impact on the others. How groups function in organizations important implications for organizational productivity. Groups in which members respect one another, feel the desire to contribute to the team, and are capable of coordinating their efforts may have high performance levels, whereas teams characterized by extreme levels of conflict or hostility may demoralize members of the workforce.

In organizations, you may encounter different types of groups. Informal work groups are made up of two or more individuals who are associated with one another in ways not prescribed by the formal organization. For example, a few people in the company who get together to play tennis on the weekend would be considered an informal group. A formal work group is made up of employees who mutually influence and interact regularly with one another on work-related matters. We will discuss many different types of formal work groups later on in this chapter. We will also distinguish groups from teams.

Stages of Group Development

Forming, storming, norming, and performing.

American organizational psychologist Bruce Tuckman presented a robust model in 1965 that is still widely used today. Based on his observations of group behavior in a variety of settings, he proposed a four-stage map of group evolution, also known as the forming-storming-norming-performing model (Tuckman, 1965). Later he enhanced the model by adding a fifth and final stage, the adjourning phase . Interestingly enough, just as an individual moves through developmental stages such as childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, so does a group, although in a much shorter period of time. According to this theory, in order to successfully facilitate a group, the leader needs to move through various leadership styles over time. Generally, this is accomplished by first being more directive, eventually serving as a coach, and later, once the group is able to assume more power and responsibility for itself, shifting to a delegator. While research has not confirmed that this is descriptive of how groups progress, knowing and following these steps can help groups be more effective. For example, groups that do not go through the storming phase early on will often return to this stage toward the end of the group process to address unresolved issues. Another example of the validity of the group development model involves groups that take the time to get to know each other socially in the forming stage. When this occurs, groups tend to handle future challenges better because the individuals have an understanding of each other’s needs.

Figure 8.2 Stages of the Group Development Model

In the forming stage, the group comes together for the first time. The members may already know each other or they may be total strangers. In either case, there is a level of formality, some anxiety, and a degree of guardedness as group members are not sure what is going to happen next. “Will I be accepted? What will my role be? Who has the power here?” These are some of the questions participants think about during this stage of group formation. Because of the large amount of uncertainty, members tend to be polite, observant, and avoid conflict. They are trying to figure out the “rules of the game” without being too vulnerable. At this point, they may also be quite excited and optimistic about the task at hand, perhaps experiencing a level of pride at being chosen to join this particular group. Group members are trying to achieve several goals at this stage, although this may not necessarily be aware of it. First, they are trying to get to know each other. Often this can be accomplished by finding some common ground. Members also begin to explore group boundaries to determine what will be considered acceptable behavior. “Can I interrupt? Can I leave when I feel like it?” This trial phase may also involve testing the appointed leader or seeing if an informal leader emerges in groups in which no leader is assigned. At this point, group members are also discovering how the group will work in terms of what needs to be done and who will be responsible for each task. This stage is often characterized by abstract discussions about issues to be addressed by the group; those who like to get moving can become impatient with this part of the process. This phase is usually short in duration, perhaps a meeting or two.

Once group members feel sufficiently safe and included, they tend to enter the storming phase. Participants focus less on keeping their guard up as they shed social facades, becoming more authentic and more argumentative. Group members begin to explore their power and influence, and they often stake out their territory by differentiating themselves from the other group members rather than seeking common ground. Discussions can become heated as participants raise contending points of view and values, or argue over how tasks should be done and who is assigned to them. It is not unusual for group members to become defensive, competitive, or jealous. They may even take sides or begin to form cliques within the group. Questioning and resisting direction from the leader is also quite common. “Why should I have to do this? Who designed this project in the first place? Why do I have to listen to you?” Although little seems to get accomplished at this stage, group members are becoming more authentic as they express their deeper thoughts and feelings. What they are really exploring is “Can I truly be me, have power, and be accepted?” During this chaotic stage, a great deal of creative energy that was previously buried is released and available for use, but it takes skill to move the group on from the storming phase. In many cases, the group gets stuck in the storming phase.

OB Toolbox: Avoid Getting Stuck in the Storming Phase!

There are several steps you can take to avoid getting stuck in the storming phase of group development. Try the following if you feel the group process you are involved in is not progressing:

- Normalize conflict . Let members know this is a natural phase in the group-formation process. Ensure conflict is about the task, avoid any personal attacks.

- Be inclusive . Continue to make all members feel included and invite all views into the room. Mention how diverse ideas and opinions help foster creativity and innovation.

- Make sure everyone is heard . Facilitate heated discussions and help participants understand each other.

- Support all group members . This is especially important for those who feel more insecure.

- Remain positive . This is a key point to remember about the group’s ability to accomplish its goal.

- Don’t rush the group’s development . Remember that working through the storming stage can take several meetings.

Once group members discover that they can be authentic and that the group is capable of handling differences without dissolving, they are ready to enter the next stage, norming.

“We survived!” is the common sentiment at the norming stage. Group members often feel elated at this point, and they are much more committed to each other and the group’s goal. Feeling energized by knowing they can handle the “tough stuff,” group members are now ready to get to work. Finding themselves more cohesive and cooperative, participants find it easy to establish their own ground rules (or norms ) and define their operating procedures and goals. The group tends to make big decisions, while subgroups or individuals handle the smaller decisions. By this point, the group should be open with and have respect for one another, and members ask each other for both help and feedback. They may even begin to form friendships and share more personal information with each other. At this point, the leader should become more of a facilitator by stepping back and letting the group assume more responsibility for its goal. Since the group’s energy is running high, this is an ideal time to host a social or team-building event.

Galvanized by a sense of shared vision and a feeling of unity, the group has now shifted into high gear. Members are more interdependent, individuality and differences are respected, and group members feel themselves to be part of a greater entity. At the performing stage, participants are not only getting the work done, but they also pay greater attention to how they are doing it. They ask questions like, “Do our operating procedures best support productivity and quality assurance? Do we have suitable means for addressing differences that arise so we can preempt destructive conflicts? Are we relating to and communicating with each other in ways that enhance group dynamics and help us achieve our goals? How can I further develop as a person to become more effective?” By now, the group has matured, becoming more competent, autonomous, and insightful. Group leaders can finally move into coaching roles and help members grow in skill and leadership.

Just as groups form, so do they end. For example, many groups or teams formed in a business context are project oriented and therefore are temporary in nature. Alternatively, a working group may dissolve due to an organizational restructuring. Just as when we graduate from school or leave home for the first time, these endings can be bittersweet, with group members feeling a combination of victory, grief, and insecurity about what is coming next. For those who like routine and bond closely with fellow group members, this transition can be particularly challenging. Group leaders and members alike should be sensitive to handling these endings respectfully and compassionately. An ideal way to close a group is to set aside time to debrief (“How did it all go? What did we learn?”), acknowledge each other, and celebrate a job well done. As a team leader/facilitator, you might also consider following up again with the group six months or a year later. Sometimes, time is needed for reflecting on lessons learned, and those after-the-fact insights can help people with their future group work.

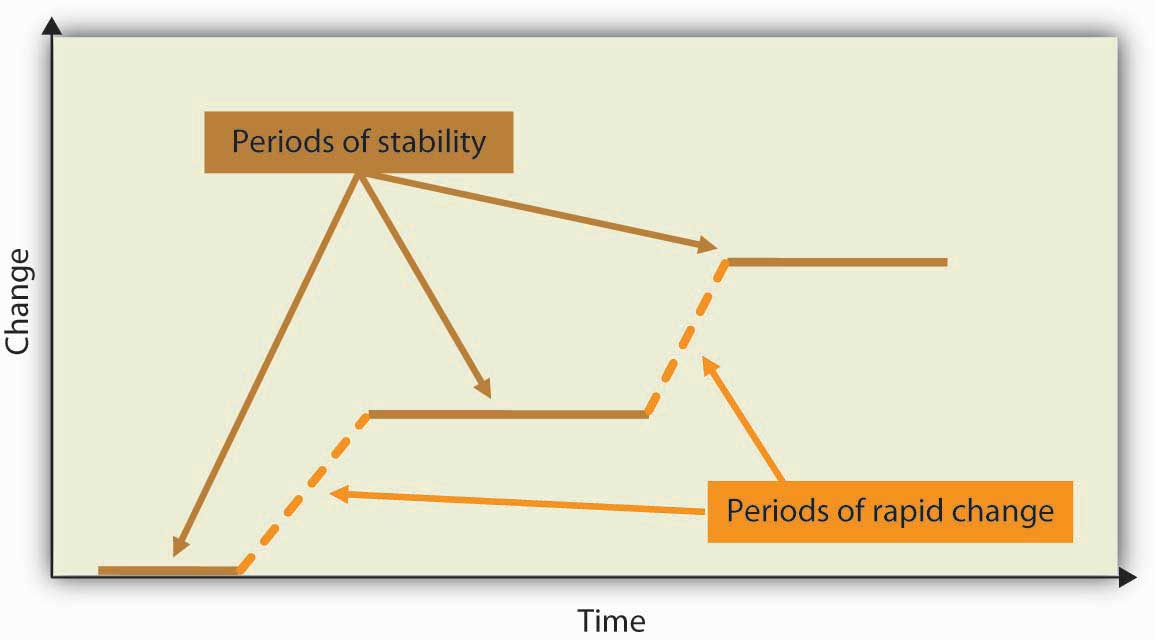

The Punctuated-Equilibrium Model

As you may have noted, the five-stage model we have just reviewed is meant to be a linear process. According to the model, a group progresses to the performing stage, at which point it finds itself in an ongoing, smooth-sailing situation until the group dissolves. In reality, subsequent researchers, most notably Joy H. Karriker, have found that the life of a group is much more dynamic and cyclical in nature (Karriker, 2005). For example, a group may operate in the performing stage for several months. Then, because of a disruption, such as a competing emerging technology that changes the rules of the game or the introduction of a new CEO, the group may revert back to the storming phase before returning to performing. Ideally, any regression in the linear group progression will ultimately result in a higher level of functioning. Proponents of this cyclical model draw from behavioral scientist Connie Gersick’s study of punctuated equilibrium (Gersick, 1991).

The concept of punctuated equilibrium was first proposed in 1972 by paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould, who both believed that evolution occurred in rapid, radical spurts rather than gradually over time. Identifying numerous examples of this pattern in social behavior, Gersick found that the concept also applied to organizational change. She proposed that groups remain fairly static, maintaining a certain equilibrium for long periods of time. Change during these periods is incremental, largely due to the resistance to change that arises when systems take root and processes become institutionalized. In this model, revolutionary change occurs in brief, punctuated bursts, generally catalyzed by a crisis or problem that breaks through the systemic inertia and shakes up the deep organizational structures in place. At this point, the organization or group has the opportunity to learn and create new structures that are better aligned with current realities. Whether the group does this is not guaranteed. In sum, in Gersick’s model, groups can repeatedly cycle through the storming and performing stages, with revolutionary change taking place during short transitional windows. For organizations and groups who understand that disruption, conflict, and chaos are inevitable in the life of a social system, these disruptions represent opportunities for innovation and creativity.

Figure 8.3 The Punctuated Equilibrium Model

Cohesion can be thought of as a kind of social glue. It refers to the degree of camaraderie within the group. Cohesive groups are those in which members are attached to each other and act as one unit. Generally speaking, the more cohesive a group is, the more productive it will be and the more rewarding the experience will be for the group’s members (Beal et al., 2003; Evans & Dion, 1991). Members of cohesive groups tend to have the following characteristics: They have a collective identity; they experience an emotional bond and a desire to remain part of the group; they share a sense of purpose, working together on a meaningful task or cause; and they establish a structured pattern of communication.

The fundamental factors affecting group cohesion include the following:

- Similarity . Generally, the more similar group members are in terms of age, sex, education, skills, attitudes, values, and beliefs, the more easily and quickly the group will bond. However, groups that work hard to create cohesion in spite of significant differences can enjoy especially deep bonds.

- Stability . The longer a group stays together, the more cohesive it becomes.

- Size . Smaller groups tend to have higher levels of cohesion.

- Support . When group members receive coaching and are encouraged to support their fellow team members, group identity strengthens.

- Satisfaction . Cohesion is correlated with how pleased group members are with each other’s performance, behavior, and conformity to group norms.

As you might imagine, there are many benefits in creating a cohesive group. Members are generally more personally satisfied and feel greater self-confidence and self-esteem when in a group where they feel they belong. For many, membership in such a group can be a buffer against stress, which can improve mental and physical well-being. Because members are invested in the group and its work, they are more likely to regularly attend and actively participate in the group, taking more responsibility for the group’s functioning. In addition, members can draw on the strength of the group to persevere through challenging situations that might otherwise be too hard to tackle alone.

OB Toolbox: Steps to Creating and Maintaining a Cohesive Team

- Align the group with the greater organization . Establish common objectives in which members can get involved.

- Let members have choices in setting their own goals . Include them in decision making at the organizational level.

- Define clear roles . Demonstrate how each person’s contribution furthers the group goal—everyone is responsible for a special piece of the puzzle.

- Situate group members in close proximity to each other . This builds familiarity.

- Give frequent praise . Both individuals and groups benefit from praise. Also encourage them to praise each other. This builds individual self-confidence, reaffirms positive behavior, and creates an overall positive atmosphere.

- Treat all members with dignity and respect . This demonstrates that there are no favorites and everyone is valued.

- Celebrate differences . This highlights each individual’s contribution while also making diversity a norm.

- Establish common rituals . Thursday morning coffee, monthly potlucks—these reaffirm group identity and create shared experiences.

Can a Group Have Too Much Cohesion?

Keep in mind that groups can have too much cohesion. Because members can come to value belonging over all else, an internal pressure to conform may arise, causing some members to modify their behavior to adhere to group norms. Members may become conflict avoidant, focusing more on trying to please each other so as not to be ostracized. In some cases, members might censor themselves to maintain the party line. As such, there is a superficial sense of harmony and less diversity of thought. Having less tolerance for deviants, who threaten the group’s static identity, cohesive groups will often excommunicate members who dare to disagree. Members attempting to make a change may even be criticized or undermined by other members, who perceive this as a threat to the status quo. The painful possibility of being marginalized can keep many members in line with the majority.

The more strongly members identify with the group, the easier it is to see outsiders as inferior, or enemies in extreme cases, which can lead to increased insularity. This form of prejudice can have a downward spiral effect. Not only is the group not getting corrective feedback from within its own confines, it is also closing itself off from input and a cross-fertilization of ideas from the outside. In such an environment, groups can easily adopt extreme ideas that will not be challenged. Denial increases as problems are ignored and failures are blamed on external factors. With limited, often biased, information and no internal or external opposition, groups like these can make disastrous decisions. Groupthink is a group pressure phenomenon that increases the risk of the group making flawed decisions by allowing reductions in mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment. Groupthink is most common in highly cohesive groups (Janis, 1972).

Cohesive groups can go awry in much milder ways. For example, group members can value their social interactions so much that they have fun together but spend little time on accomplishing their assigned task. Or a group’s goal may begin to diverge from the larger organization’s goal and those trying to uphold the organization’s goal may be ostracized (e.g., teasing the class “brain” for doing well in school). Normalizing conflict and even encouraging it (e.g., by assigning a group member to the “devil’s advocate” role each meeting) can provide a safer environment for disagreements.

In addition, research shows that cohesion leads to acceptance of group norms (Goodman, Ravlin, & Schminke, 1987). Groups with high task commitment do well, but imagine a group where the norms are to work as little as possible? As you might imagine, these groups get little accomplished and can actually work together against the organization’s goals.

Social Loafing

Social loafing refers to the tendency of individuals to put in less effort when working in a group context. This phenomenon, also known as the Ringelmann effect, was first noted by French agricultural engineer Max Ringelmann in 1913. In one study, he had people pull on a rope individually and in groups. He found that as the number of people pulling increased, individuals reduced their own effort so that the benefits of more people were not realized (Karau & Williams, 1993).

Why do people work less hard when they are working with other people? Observations show that as the size of the group grows, this effect becomes larger as well (Karau & Williams, 1993). The social loafing tendency is less a matter of being lazy and more a matter of perceiving that one will receive neither one’s fair share of rewards if the group is successful nor blame if the group fails. Rationales for this behavior include, “My own effort will have little effect on the outcome,” “Others aren’t pulling their weight, so why should I?” or “I don’t have much to contribute, but no one will notice anyway.” This is a consistent effect across a great number of group tasks and countries (Gabrenya, Latane, & Wang, 1983; Harkins & Petty, 1982; Taylor & Faust, 1952; Ziller, 1957). Research also shows that perceptions of fairness are related to less social loafing (Price, Harrison, & Gavin, 2006). Therefore, teams that are deemed as more fair should also see less social loafing.

OB Toolbox: Tips for Preventing Social Loafing in Your Group

When designing a group project, here are some considerations to keep in mind:

- Carefully choose the number of individuals you need to get the task done . The likelihood of social loafing increases as group size increases (especially if the group consists of 10 or more people), because it is easier for people to feel unneeded or inadequate, and it is easier for them to “hide” in a larger group.

- Clearly define each member’s tasks in front of the entire group . If you assign a task to the entire group, social loafing is more likely. For example, instead of stating, “By Monday, let’s find several articles on the topic of stress,” you can set the goal of “By Monday, each of us will be responsible for finding five articles on the topic of stress.” When individuals have specific goals, they become more accountable for their performance.

- Design and communicate to the entire group a system for evaluating each person’s contribution . You may have a midterm feedback session in which each member gives feedback to every other member. This would increase the sense of accountability individuals have. You may even want to discuss the principle of social loafing in order to discourage it.

- Build a cohesive group . When group members develop strong relational bonds, they are more committed to each other and the success of the group, and they are therefore more likely to pull their own weight.

- Assign tasks that are highly engaging and inherently rewarding . Design challenging, unique, and varied activities that will have a significant impact on the individuals themselves, the organization, or the external environment. For example, one group member may be responsible for crafting a new incentive-pay system through which employees can direct some of their bonus to their favorite nonprofits.

- Make sure individuals feel that they are needed . If the group ignores a member’s contributions because these contributions do not meet the group’s performance standards, members will feel discouraged and are unlikely to contribute in the future. Make sure that everyone feels included and needed by the group.

Collective Efficacy

Collective efficacy refers to a group’s perception of its ability to successfully perform well (Bandura, 1997). Collective efficacy is influenced by a number of factors, including watching others (“that group did it and we’re better than them”), verbal persuasion (“we can do this”), and how a person feels (“this is a good group”). Research shows that a group’s collective efficacy is related to its performance (Gully et al., 2002; Porter, 2005; Tasa, Taggar, & Seijts, 2007). In addition, this relationship is higher when task interdependence (the degree an individual’s task is linked to someone else’s work) is high rather than low.

Key Takeaway

Groups may be either formal or informal. Groups go through developmental stages much like individuals do. The forming-storming-norming-performing-adjourning model is useful in prescribing stages that groups should pay attention to as they develop. The punctuated-equilibrium model of group development argues that groups often move forward during bursts of change after long periods without change. Groups that are similar, stable, small, supportive, and satisfied tend to be more cohesive than groups that are not. Cohesion can help support group performance if the group values task completion. Too much cohesion can also be a concern for groups. Social loafing increases as groups become larger. When collective efficacy is high, groups tend to perform better.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Beal, D. J., Cohen, R. R., Burke, M. J., & McLendon, C. L. (2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology , 88 , 989–1004.

Evans, C. R., & Dion, K. L. (1991). Group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Small Group Research , 22 , 175–186.

Gabrenya, W. L., Latane, B., & Wang, Y. (1983). Social loafing in cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Perspective , 14 , 368–384.

Gersick, C. J. G. (1991). Revolutionary change theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm. Academy of Management Review , 16 , 10–36.

Goodman, P. S., Ravlin, E., & Schminke, M. (1987). Understanding groups in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior , 9 , 121–173.

Gully, S. M., Incalcaterra, K. A., Joshi, A., & Beaubien, J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology , 87 , 819–832.

Harkins, S., & Petty, R. E. (1982). Effects of task difficulty and task uniqueness on social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 43 , 1214–1229.

Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of Groupthink . New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Karau, S. J., & Williams, K. D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 65 , 681–706.

Karriker, J. H. (2005). Cyclical group development and interaction-based leadership emergence in autonomous teams: An integrated model. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies , 11 , 54–64.

Porter, C. O. L. H. (2005). Goal orientation: Effects on backing up behavior, performance, efficacy, and commitment in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology , 90 , 811–818.

Price, K. H., Harrison, D. A., & Gavin, J. H. (2006). Withholding inputs in team contexts: Member composition, interaction processes, evaluation structure, and social loafing. Journal of Applied Psychology , 91 , 1375–1384.

Tasa, K., Taggar, S., & Seijts, G. H. (2007). The development of collective efficacy in teams: A multilevel and longitudinal perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology , 92 , 17–27.

Taylor, D. W., & Faust, W. L. (1952). Twenty questions: Efficiency of problem-solving as a function of the size of the group. Journal of Experimental Psychology , 44 , 360–363.

Tuckman, B. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin , 63 , 384–399.

Ziller, R. C. (1957). Four techniques of group decision-making under uncertainty. Journal of Applied Psychology , 41 , 384–388.

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- R Soc Open Sci

- v.3(4); 2016 Apr

Understanding the group dynamics and success of teams

Michael klug.

1 Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA

James P. Bagrow

2 Vermont Complex Systems Center, The University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA

3 Vermont Advanced Computing Core, The University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA

Associated Data

All data analysed are made publicly available by the GitHub Archive Project ( https://www.githubarchive.org ).

Complex problems often require coordinated group effort and can consume significant resources, yet our understanding of how teams form and succeed has been limited by a lack of large-scale, quantitative data. We analyse activity traces and success levels for approximately 150 000 self-organized, online team projects. While larger teams tend to be more successful, workload is highly focused across the team, with only a few members performing most work. We find that highly successful teams are significantly more focused than average teams of the same size, that their members have worked on more diverse sets of projects, and the members of highly successful teams are more likely to be core members or ‘leads’ of other teams. The relations between team success and size, focus and especially team experience cannot be explained by confounding factors such as team age, external contributions from non-team members, nor by group mechanisms such as social loafing. Taken together, these features point to organizational principles that may maximize the success of collaborative endeavours.

1. Introduction

Massive datasets describing the activity patterns of large human populations now provide researchers with rich opportunities to quantitatively study human dynamics [ 1 , 2 ], including the activities of groups or teams [ 3 , 4 ]. New tools, including electronic sensor systems, can quantify team activity and performance [ 5 , 4 ]. With the rise in prominence of network science [ 6 , 7 ], much effort has gone into discovering meaningful groups within social networks [ 8 – 15 ] and quantifying their evolution [ 15 , 16 ]. Teams are increasingly important in research and industrial efforts [ 3 , 4 , 17 – 21 ], and small, coordinated groups are a significant component of modern human conflict [ 22 , 23 ]. There are many important dimensions along which teams should be studied, including their size, how work is distributed among their members, and the differences and similarities in the experiences and backgrounds of those team members. Recently, there has been much debate on the ‘group size hypothesis’ that larger groups are more robust or perform better than smaller ones [ 24 – 27 ]. Scholars of science have noted for decades that collaborative research teams have been growing in size and importance [ 20 , 28 – 30 ]. At the same time, however, social loafing, where individuals apply less effort to a task when they are in a group than when they are alone, may counterbalance the effectiveness of larger teams [ 31 – 33 ]. Meanwhile, case studies show that leadership [ 3 , 34 – 36 ] and experience [ 37 , 38 ] are key components of successful team outcomes, while specialization and multitasking are important but potentially error-prone mechanisms for dealing with complexity and cognitive overload [ 39 , 40 ]. In all of these areas, large-scale, quantitative data can push the study of teams forward.

Teams are important for modern software engineering tasks, and researchers have long studied the digital traces of open source software projects to better quantify and understand how teams work on software projects [ 41 , 42 ]. Researchers have investigated estimators of work activity or effort based on edit volume, such as different ways to count the number of changes made to a software's source code [ 43 – 46 ]. Various dimensions of success of software projects such as popularity, timeliness of bug fixes or other quality measures have been studied [ 47 – 49 ]. Successful open source software projects show a layered structure of primary or core contributors surrounded by lesser, secondary contributors [ 50 ]. At the same time, much work is focused on case studies [ 45 , 51 ] of small numbers of highly successful, large projects [ 41 ]. Considering these studies alone runs the risk of survivorship bias or other selection biases, so large-scale studies of large quantities of teams are important complements to these works.

Users of the GitHub web platform can form teams to work on real-world projects, primarily software development but also music, literature, design work and more. A number of important scientific computing resources are now developed through GitHub, including astronomical software, genetic sequencing tools and key components of the Compact Muon Solenoid experiment's data pipeline. 1 A ‘GitHub for science’ initiative has been launched 2 and GitHub is becoming the dominant service for open scientific development.

GitHub provides rich public data on team activities, including when new teams form, when members join existing teams and when a team's project is updated. GitHub also provides social media tools for the discovery of interesting projects. Users who see the work of a team can choose to flag it as interesting to them by ‘starring’ it. The number of these ‘stargazers’ S allows us to quantify one aspect of the success of the team, in a manner analogous to the use of citations of research literature as a proxy for ‘impact’ [ 52 ]. Of course, as with bibliometric impact, one should be cautious and not consider success to be a perfectly accurate measure of quality , something that is far more difficult to objectively quantify. Instead this is a measure of popularity as would be other statistics such as web traffic, number of downloads and so forth [ 47 ].

In this study, we analyse the memberships and activities of approximately 150 000 teams, as they perform real-world tasks, to uncover the blend of features that relate to success. To the best of our knowledge this is the largest study of real-world team success to date. We present results that demonstrate (i) how teams distribute or focus work activity across their members, (ii) the mixture of experiential diversity and collective leadership roles in teams, and (iii) how successful teams are different from other teams while accounting for confounds such as team size.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: in § 2 , we describe our GitHub dataset; give definitions of a team, team success and work activity/focus of a team member; and introduce metrics to measure various aspects of the experience and experiential diversity of a team's members. In § 3 , we present our results relating these measures to team success. In § 4 , we present statistical tests on linear regression models of team features to control for potential confounds between team features and team success. Lastly, we conclude with a discussion in § 5 .

2. Material and methods

2.1. dataset and team selection.