Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.2 Writing Body Paragraphs

Learning objectives.

- Select primary support related to your thesis.

- Support your topic sentences.

If your thesis gives the reader a roadmap to your essay, then body paragraphs should closely follow that map. The reader should be able to predict what follows your introductory paragraph by simply reading the thesis statement.

The body paragraphs present the evidence you have gathered to confirm your thesis. Before you begin to support your thesis in the body, you must find information from a variety of sources that support and give credit to what you are trying to prove.

Select Primary Support for Your Thesis

Without primary support, your argument is not likely to be convincing. Primary support can be described as the major points you choose to expand on your thesis. It is the most important information you select to argue for your point of view. Each point you choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph you write. Your primary supporting points are further supported by supporting details within the paragraphs.

Remember that a worthy argument is backed by examples. In order to construct a valid argument, good writers conduct lots of background research and take careful notes. They also talk to people knowledgeable about a topic in order to understand its implications before writing about it.

Identify the Characteristics of Good Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of good primary support, the information you choose must meet the following standards:

- Be specific. The main points you make about your thesis and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be specific. Use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon your general ideas. These types of examples give your reader something narrow to focus on, and if used properly, they leave little doubt about your claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical.

- Be relevant to the thesis. Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove your main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all in your body paragraphs. But effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Choose your examples wisely by making sure they directly connect to your thesis.

- Be detailed. Remember that your thesis, while specific, should not be very detailed. The body paragraphs are where you develop the discussion that a thorough essay requires. Using detailed support shows readers that you have considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance your point of view.

Prewrite to Identify Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

Recall that when you prewrite you essentially make a list of examples or reasons why you support your stance. Stemming from each point, you further provide details to support those reasons. After prewriting, you are then able to look back at the information and choose the most compelling pieces you will use in your body paragraphs.

Choose one of the following working thesis statements. On a separate sheet of paper, write for at least five minutes using one of the prewriting techniques you learned in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

- Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

- Students cheat for many different reasons.

- Drug use among teens and young adults is a problem.

- The most important change that should occur at my college or university is ____________________________________________.

Select the Most Effective Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

After you have prewritten about your working thesis statement, you may have generated a lot of information, which may be edited out later. Remember that your primary support must be relevant to your thesis. Remind yourself of your main argument, and delete any ideas that do not directly relate to it. Omitting unrelated ideas ensures that you will use only the most convincing information in your body paragraphs. Choose at least three of only the most compelling points. These will serve as the topic sentences for your body paragraphs.

Refer to the previous exercise and select three of your most compelling reasons to support the thesis statement. Remember that the points you choose must be specific and relevant to the thesis. The statements you choose will be your primary support points, and you will later incorporate them into the topic sentences for the body paragraphs.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

When you support your thesis, you are revealing evidence. Evidence includes anything that can help support your stance. The following are the kinds of evidence you will encounter as you conduct your research:

- Facts. Facts are the best kind of evidence to use because they often cannot be disputed. They can support your stance by providing background information on or a solid foundation for your point of view. However, some facts may still need explanation. For example, the sentence “The most populated state in the United States is California” is a pure fact, but it may require some explanation to make it relevant to your specific argument.

- Judgments. Judgments are conclusions drawn from the given facts. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and examination of a topic.

- Testimony. Testimony consists of direct quotations from either an eyewitness or an expert witness. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; he adds authenticity to an argument based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive experience with a topic. This person studies the facts and provides commentary based on either facts or judgments, or both. An expert witness adds authority and credibility to an argument.

- Personal observation. Personal observation is similar to testimony, but personal observation consists of your testimony. It reflects what you know to be true because you have experiences and have formed either opinions or judgments about them. For instance, if you are one of five children and your thesis states that being part of a large family is beneficial to a child’s social development, you could use your own experience to support your thesis.

Writing at Work

In any job where you devise a plan, you will need to support the steps that you lay out. This is an area in which you would incorporate primary support into your writing. Choosing only the most specific and relevant information to expand upon the steps will ensure that your plan appears well-thought-out and precise.

You can consult a vast pool of resources to gather support for your stance. Citing relevant information from reliable sources ensures that your reader will take you seriously and consider your assertions. Use any of the following sources for your essay: newspapers or news organization websites, magazines, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, which are periodicals that address topics in a specialized field.

Choose Supporting Topic Sentences

Each body paragraph contains a topic sentence that states one aspect of your thesis and then expands upon it. Like the thesis statement, each topic sentence should be specific and supported by concrete details, facts, or explanations.

Each body paragraph should comprise the following elements.

topic sentence + supporting details (examples, reasons, or arguments)

As you read in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , topic sentences indicate the location and main points of the basic arguments of your essay. These sentences are vital to writing your body paragraphs because they always refer back to and support your thesis statement. Topic sentences are linked to the ideas you have introduced in your thesis, thus reminding readers what your essay is about. A paragraph without a clearly identified topic sentence may be unclear and scattered, just like an essay without a thesis statement.

Unless your teacher instructs otherwise, you should include at least three body paragraphs in your essay. A five-paragraph essay, including the introduction and conclusion, is commonly the standard for exams and essay assignments.

Consider the following the thesis statement:

Author J.D. Salinger relied primarily on his personal life and belief system as the foundation for the themes in the majority of his works.

The following topic sentence is a primary support point for the thesis. The topic sentence states exactly what the controlling idea of the paragraph is. Later, you will see the writer immediately provide support for the sentence.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced themes in many of his works.

In Note 9.19 “Exercise 2” , you chose three of your most convincing points to support the thesis statement you selected from the list. Take each point and incorporate it into a topic sentence for each body paragraph.

Supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Topic sentence: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

Draft Supporting Detail Sentences for Each Primary Support Sentence

After deciding which primary support points you will use as your topic sentences, you must add details to clarify and demonstrate each of those points. These supporting details provide examples, facts, or evidence that support the topic sentence.

The writer drafts possible supporting detail sentences for each primary support sentence based on the thesis statement:

Thesis statement: Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

Supporting point 1: Dogs can scare cyclists and pedestrians.

Supporting details:

- Cyclists are forced to zigzag on the road.

- School children panic and turn wildly on their bikes.

- People who are walking at night freeze in fear.

Supporting point 2:

Loose dogs are traffic hazards.

- Dogs in the street make people swerve their cars.

- To avoid dogs, drivers run into other cars or pedestrians.

- Children coaxing dogs across busy streets create danger.

Supporting point 3: Unleashed dogs damage gardens.

- They step on flowers and vegetables.

- They destroy hedges by urinating on them.

- They mess up lawns by digging holes.

The following paragraph contains supporting detail sentences for the primary support sentence (the topic sentence), which is underlined.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced the themes in many of his works. He did not hide his mental anguish over the horrors of war and once told his daughter, “You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose, no matter how long you live.” His short story “A Perfect Day for a Bananafish” details a day in the life of a WWII veteran who was recently released from an army hospital for psychiatric problems. The man acts questionably with a little girl he meets on the beach before he returns to his hotel room and commits suicide. Another short story, “For Esmé – with Love and Squalor,” is narrated by a traumatized soldier who sparks an unusual relationship with a young girl he meets before he departs to partake in D-Day. Finally, in Salinger’s only novel, The Catcher in the Rye , he continues with the theme of posttraumatic stress, though not directly related to war. From a rest home for the mentally ill, sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield narrates the story of his nervous breakdown following the death of his younger brother.

Using the three topic sentences you composed for the thesis statement in Note 9.18 “Exercise 1” , draft at least three supporting details for each point.

Thesis statement: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Supporting details: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

You have the option of writing your topic sentences in one of three ways. You can state it at the beginning of the body paragraph, or at the end of the paragraph, or you do not have to write it at all. This is called an implied topic sentence. An implied topic sentence lets readers form the main idea for themselves. For beginning writers, it is best to not use implied topic sentences because it makes it harder to focus your writing. Your instructor may also want to clearly identify the sentences that support your thesis. For more information on the placement of thesis statements and implied topic statements, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Print out the first draft of your essay and use a highlighter to mark your topic sentences in the body paragraphs. Make sure they are clearly stated and accurately present your paragraphs, as well as accurately reflect your thesis. If your topic sentence contains information that does not exist in the rest of the paragraph, rewrite it to more accurately match the rest of the paragraph.

Key Takeaways

- Your body paragraphs should closely follow the path set forth by your thesis statement.

- Strong body paragraphs contain evidence that supports your thesis.

- Primary support comprises the most important points you use to support your thesis.

- Strong primary support is specific, detailed, and relevant to the thesis.

- Prewriting helps you determine your most compelling primary support.

- Evidence includes facts, judgments, testimony, and personal observation.

- Reliable sources may include newspapers, magazines, academic journals, books, encyclopedias, and firsthand testimony.

- A topic sentence presents one point of your thesis statement while the information in the rest of the paragraph supports that point.

- A body paragraph comprises a topic sentence plus supporting details.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

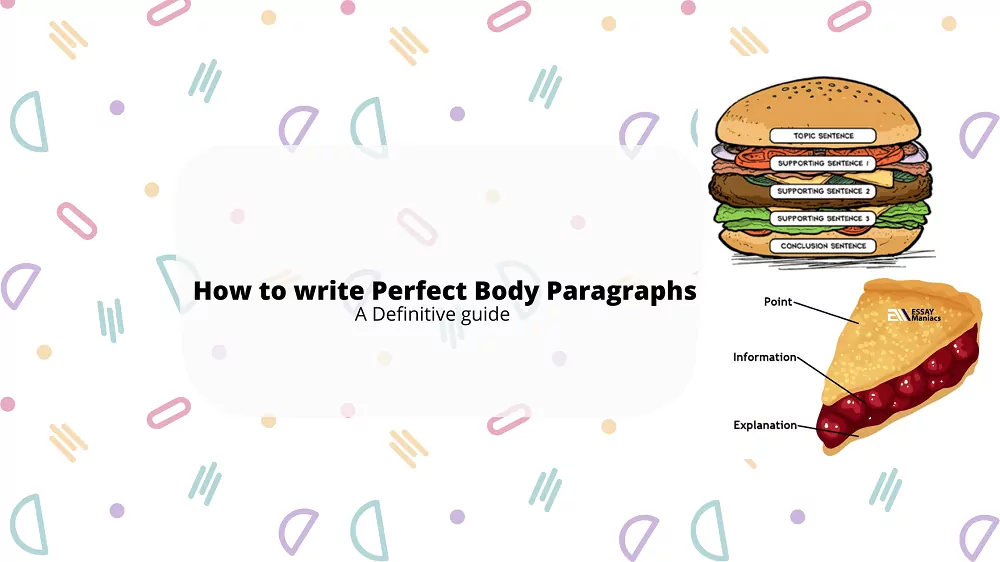

How to Write a Body Paragraph for a College Essay

January 29, 2024

No matter the discipline, college success requires mastering several academic basics, including the body paragraph. This article will provide tips on drafting and editing a strong body paragraph before examining several body paragraph examples. Before we look at how to start a body paragraph and how to write a body paragraph for a college essay (or other writing assignment), let’s define what exactly a body paragraph is.

What is a Body Paragraph?

Simply put, a body paragraph consists of everything in an academic essay that does not constitute the introduction and conclusion. It makes up everything in between. In a five-paragraph, thesis-style essay (which most high schoolers encounter before heading off to college), there are three body paragraphs. Longer essays with more complex arguments will include many more body paragraphs.

We might correlate body paragraphs with bodily appendages—say, a leg. Both operate in a somewhat isolated way to perform specific operations, yet are integral to creating a cohesive, functioning whole. A leg helps the body sit, walk, and run. Like legs, body paragraphs work to move an essay along, by leading the reader through several convincing ideas. Together, these ideas, sometimes called topics, or points, work to prove an overall argument, called the essay’s thesis.

If you compared an essay on Kant’s theory of beauty to an essay on migratory birds, you’d notice that the body paragraphs differ drastically. However, on closer inspection, you’d probably find that they included many of the same key components. Most body paragraphs will include specific, detailed evidence, an analysis of the evidence, a conclusion drawn by the author, and several tie-ins to the larger ideas at play. They’ll also include transitions and citations leading the reader to source material. We’ll go into more detail on these components soon. First, let’s see if you’ve organized your essay so that you’ll know how to start a body paragraph.

How to Start a Body Paragraph

It can be tempting to start writing your college essay as soon as you sit down at your desk. The sooner begun, the sooner done, right? I’d recommend resisting that itch. Instead, pull up a blank document on your screen and make an outline. There are numerous reasons to make an outline, and most involve helping you stay on track. This is especially true of longer college papers, like the 60+ page dissertation some seniors are required to write. Even with regular writing assignments with a page count between 4-10, an outline will help you visualize your argumentation strategy. Moreover, it will help you order your key points and their relevant evidence from most to least convincing. This in turn will determine the order of your body paragraphs.

The most convincing sequence of body paragraphs will depend entirely on your paper’s subject. Let’s say you’re writing about Penelope’s success in outwitting male counterparts in The Odyssey . You may want to begin with Penelope’s weaving, the most obvious way in which Penelope dupes her suitors. You can end with Penelope’s ingenious way of outsmarting her own husband. Because this evidence is more ambiguous it will require a more nuanced analysis. Thus, it’ll work best as your final body paragraph, after readers have already been convinced of more digestible evidence. If in doubt, keep your body paragraph order chronological.

It can be worthwhile to consider your topic from multiple perspectives. You may decide to include a body paragraph that sets out to consider and refute an opposing point to your thesis. This type of body paragraph will often appear near the end of the essay. It works to erase any lingering doubts readers may have had, and requires strong rhetorical techniques.

How to Start a Body Paragraph, Continued

Once you’ve determined which key points will best support your argument and in what order, draft an introduction. This is a crucial step towards writing a body paragraph. First, it will set the tone for the rest of your paper. Second, it will require you to articulate your thesis statement in specific, concise wording. Highlight or bold your thesis statement, so you can refer back to it quickly. You should be looking at your thesis throughout the drafting of your body paragraphs.

Finally, make sure that your introduction indicates which key points you’ll be covering in your body paragraphs, and in what order. While this level of organization might seem like overkill, it will indicate to the reader that your entire paper is minutely thought-out. It will boost your reader’s confidence going in. They’ll feel reassured and open to your thought process if they can see that it follows a clear path.

Now that you have an essay outline and introduction, you’re ready to draft your body paragraphs.

How to Draft a Body Paragraph

At this point, you know your body paragraph topic, the key point you’re trying to make, and you’ve gathered your evidence. The next thing to do is write! The words highlighted in bold below comprise the main components that will make up your body paragraph. (You’ll notice in the body paragraph examples below that the order of these components is flexible.)

Start with a topic sentence . This will indicate the main point you plan to make that will work to support your overall thesis. Your topic sentence also alerts the reader to the change in topic from the last paragraph to the current one. In making this new topic known, you’ll want to create a transition from the last topic to this one.

Transitions appear in nearly every paragraph of a college essay, apart from the introduction. They create a link between disparate ideas. (For example, if your transition comes at the end of paragraph 4, you won’t need a second transition at the beginning of paragraph 5.) The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Writing Center has a page devoted to Developing Strategic Transitions . Likewise, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Writing Center offers help on paragraph transitions .

How to Draft a Body Paragraph for a College Essay ( Continued)

With the topic sentence written, you’ll need to prove your point through tangible evidence. This requires several sentences with various components. You’ll want to provide more context , going into greater detail to situate the reader within the topic. Next, you’ll provide evidence , often in the form of a quote, facts, or data, and supply a source citation . Citing your source is paramount. Sources indicate that your evidence is empirical and objective. It implies that your evidence is knowledge shared by others in the academic community. Sometimes you’ll want to provide multiple pieces of evidence, if the evidence is similar and can be grouped together.

After providing evidence, you must provide an interpretation and analysis of this evidence. In other words, use rhetorical techniques to paraphrase what your evidence seems to suggest. Break down the evidence further and explain and summarize it in new words. Don’t simply skip to your conclusion. Your evidence should never stand for itself. Why? Because your interpretation and analysis allow you to exhibit original, analytical, and critical thinking skills.

Depending on what evidence you’re using, you may repeat some of these components in the same body paragraph. This might look like: more context + further evidence + increased interpretation and analysis . All this will add up to proving and reaffirming your body paragraph’s main point . To do so, conclude your body paragraph by reformulating your thesis statement in light of the information you’ve given. I recommend comparing your original thesis statement to your paragraph’s concluding statement. Do they align? Does your body paragraph create a sound connection to the overall academic argument? If not, you’ll need to fix this issue when you edit your body paragraph.

How to Edit a Body Paragraph

As you go over each body paragraph of your college essay, keep this short checklist in mind.

- Consistency in your argument: If your key points don’t add up to a cogent argument, you’ll need to identify where the inconsistency lies. Often it lies in interpretation and analysis. You may need to improve the way you articulate this component. Try to think like a lawyer: how can you use this evidence to your advantage? If that doesn’t work, you may need to find new evidence. As a last resort, amend your thesis statement.

- Language-level persuasion. Use a broad vocabulary. Vary your sentence structure. Don’t repeat the same words too often, which can induce mental fatigue in the reader. I suggest keeping an online dictionary open on your browser. I find Merriam-Webster user-friendly, since it allows you to toggle between definitions and synonyms. It also includes up-to-date example sentences. Also, don’t forget the power of rhetorical devices .

- Does your writing flow naturally from one idea to the next, or are there jarring breaks? The editing stage is a great place to polish transitions and reinforce the structure as a whole.

Our first body paragraph example comes from the College Transitions article “ How to Write the AP Lang Argument Essay .” Here’s the prompt: Write an essay that argues your position on the value of striving for perfection.

Here’s the example thesis statement, taken from the introduction paragraph: “Striving for perfection can only lead us to shortchange ourselves. Instead, we should value learning, growth, and creativity and not worry whether we are first or fifth best.” Now let’s see how this writer builds an argument against perfection through one main point across two body paragraphs. (While this writer has split this idea into two paragraphs, one to address a problem and one to provide an alternative resolution, it could easily be combined into one paragraph.)

“Students often feel the need to be perfect in their classes, and this can cause students to struggle or stop making an effort in class. In elementary and middle school, for example, I was very nervous about public speaking. When I had to give a speech, my voice would shake, and I would turn very red. My teachers always told me “relax!” and I got Bs on Cs on my speeches. As a result, I put more pressure on myself to do well, spending extra time making my speeches perfect and rehearsing late at night at home. But this pressure only made me more nervous, and I started getting stomach aches before speaking in public.

“Once I got to high school, however, I started doing YouTube make-up tutorials with a friend. We made videos just for fun, and laughed when we made mistakes or said something silly. Only then, when I wasn’t striving to be perfect, did I get more comfortable with public speaking.”

Body Paragraph Example 1 Dissected

In this body paragraph example, the writer uses their personal experience as evidence against the value of striving for perfection. The writer sets up this example with a topic sentence that acts as a transition from the introduction. They also situate the reader in the classroom. The evidence takes the form of emotion and physical reactions to the pressure of public speaking (nervousness, shaking voice, blushing). Evidence also takes the form of poor results (mediocre grades). Rather than interpret the evidence from an analytical perspective, the writer produces more evidence to underline their point. (This method works fine for a narrative-style essay.) It’s clear that working harder to be perfect further increased the student’s nausea.

The writer proves their point in the second paragraph, through a counter-example. The main point is that improvement comes more naturally when the pressure is lifted; when amusement is possible and mistakes aren’t something to fear. This point ties back in with the thesis, that “we should value learning, growth, and creativity” over perfection.

This second body paragraph example comes from the College Transitions article “ How to Write the AP Lang Rhetorical Analysis Essay .” Here’s an abridged version of the prompt: Rosa Parks was an African American civil rights activist who was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Read the passage carefully. Write an essay that analyzes the rhetorical choices Obama makes to convey his message.

Here’s the example thesis statement, taken from the introduction paragraph: “Through the use of diction that portrays Parks as quiet and demure, long lists that emphasize the extent of her impacts, and Biblical references, Obama suggests that all of us are capable of achieving greater good, just as Parks did.” Now read the body paragraph example, below.

“To further illustrate Parks’ impact, Obama incorporates Biblical references that emphasize the importance of “that single moment on the bus” (lines 57-58). In lines 33-35, Obama explains that Parks and the other protestors are “driven by a solemn determination to affirm their God-given dignity” and he also compares their victory to the fall the “ancient walls of Jericho” (line 43). By including these Biblical references, Obama suggests that Parks’ action on the bus did more than correct personal or political wrongs; it also corrected moral and spiritual wrongs. Although Parks had no political power or fortune, she was able to restore a moral balance in our world.”

Body Paragraph Example 2 Dissected

The first sentence in this body paragraph example indicates that the topic is transitioning into biblical references as a means of motivating ordinary citizens. The evidence comes as quotes taken from Obama’s speech. One is a reference to God, and the other an allusion to a story from the bible. The subsequent interpretation and analysis demonstrate that Obama’s biblical references imply a deeper, moral and spiritual significance. The concluding sentence draws together the morality inherent in equal rights with Rosa Parks’ power to spark change. Through the words “no political power or fortune,” and “moral balance,” the writer ties the point proven in this body paragraph back to the thesis statement. Obama promises that “All of us” (no matter how small our influence) “are capable of achieving greater good”—a greater moral good.

What’s Next?

Before you body paragraphs come the start and, after your body paragraphs, the conclusion, of course! If you’ve found this article helpful, be sure to read up on how to start a college essay and how to end a college essay .

You may also find the following blogs to be of interest:

- 6 Best Common App Essay Examples

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay

- UC Essay Examples

- How to Write the Community Essay

- How to Write the Why this Major? Essay

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- ADHD/LD/Autism/Executive Functioning

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Homeschool Resources

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Outdoor Adventure

- Private High School Spotlight

- Research Programs

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Teacher Tools

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to structure an essay: Templates and tips

How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates

Published on September 18, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The basic structure of an essay always consists of an introduction , a body , and a conclusion . But for many students, the most difficult part of structuring an essay is deciding how to organize information within the body.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

The basics of essay structure, chronological structure, compare-and-contrast structure, problems-methods-solutions structure, signposting to clarify your structure, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay structure.

There are two main things to keep in mind when working on your essay structure: making sure to include the right information in each part, and deciding how you’ll organize the information within the body.

Parts of an essay

The three parts that make up all essays are described in the table below.

| Part | Content |

|---|---|

Order of information

You’ll also have to consider how to present information within the body. There are a few general principles that can guide you here.

The first is that your argument should move from the simplest claim to the most complex . The body of a good argumentative essay often begins with simple and widely accepted claims, and then moves towards more complex and contentious ones.

For example, you might begin by describing a generally accepted philosophical concept, and then apply it to a new topic. The grounding in the general concept will allow the reader to understand your unique application of it.

The second principle is that background information should appear towards the beginning of your essay . General background is presented in the introduction. If you have additional background to present, this information will usually come at the start of the body.

The third principle is that everything in your essay should be relevant to the thesis . Ask yourself whether each piece of information advances your argument or provides necessary background. And make sure that the text clearly expresses each piece of information’s relevance.

The sections below present several organizational templates for essays: the chronological approach, the compare-and-contrast approach, and the problems-methods-solutions approach.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The chronological approach (sometimes called the cause-and-effect approach) is probably the simplest way to structure an essay. It just means discussing events in the order in which they occurred, discussing how they are related (i.e. the cause and effect involved) as you go.

A chronological approach can be useful when your essay is about a series of events. Don’t rule out other approaches, though—even when the chronological approach is the obvious one, you might be able to bring out more with a different structure.

Explore the tabs below to see a general template and a specific example outline from an essay on the invention of the printing press.

- Thesis statement

- Discussion of event/period

- Consequences

- Importance of topic

- Strong closing statement

- Claim that the printing press marks the end of the Middle Ages

- Background on the low levels of literacy before the printing press

- Thesis statement: The invention of the printing press increased circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation

- High levels of illiteracy in medieval Europe

- Literacy and thus knowledge and education were mainly the domain of religious and political elites

- Consequence: this discouraged political and religious change

- Invention of the printing press in 1440 by Johannes Gutenberg

- Implications of the new technology for book production

- Consequence: Rapid spread of the technology and the printing of the Gutenberg Bible

- Trend for translating the Bible into vernacular languages during the years following the printing press’s invention

- Luther’s own translation of the Bible during the Reformation

- Consequence: The large-scale effects the Reformation would have on religion and politics

- Summarize the history described

- Stress the significance of the printing press to the events of this period

Essays with two or more main subjects are often structured around comparing and contrasting . For example, a literary analysis essay might compare two different texts, and an argumentative essay might compare the strengths of different arguments.

There are two main ways of structuring a compare-and-contrast essay: the alternating method, and the block method.

Alternating

In the alternating method, each paragraph compares your subjects in terms of a specific point of comparison. These points of comparison are therefore what defines each paragraph.

The tabs below show a general template for this structure, and a specific example for an essay comparing and contrasting distance learning with traditional classroom learning.

- Synthesis of arguments

- Topical relevance of distance learning in lockdown

- Increasing prevalence of distance learning over the last decade

- Thesis statement: While distance learning has certain advantages, it introduces multiple new accessibility issues that must be addressed for it to be as effective as classroom learning

- Classroom learning: Ease of identifying difficulties and privately discussing them

- Distance learning: Difficulty of noticing and unobtrusively helping

- Classroom learning: Difficulties accessing the classroom (disability, distance travelled from home)

- Distance learning: Difficulties with online work (lack of tech literacy, unreliable connection, distractions)

- Classroom learning: Tends to encourage personal engagement among students and with teacher, more relaxed social environment

- Distance learning: Greater ability to reach out to teacher privately

- Sum up, emphasize that distance learning introduces more difficulties than it solves

- Stress the importance of addressing issues with distance learning as it becomes increasingly common

- Distance learning may prove to be the future, but it still has a long way to go

In the block method, each subject is covered all in one go, potentially across multiple paragraphs. For example, you might write two paragraphs about your first subject and then two about your second subject, making comparisons back to the first.

The tabs again show a general template, followed by another essay on distance learning, this time with the body structured in blocks.

- Point 1 (compare)

- Point 2 (compare)

- Point 3 (compare)

- Point 4 (compare)

- Advantages: Flexibility, accessibility

- Disadvantages: Discomfort, challenges for those with poor internet or tech literacy

- Advantages: Potential for teacher to discuss issues with a student in a separate private call

- Disadvantages: Difficulty of identifying struggling students and aiding them unobtrusively, lack of personal interaction among students

- Advantages: More accessible to those with low tech literacy, equality of all sharing one learning environment

- Disadvantages: Students must live close enough to attend, commutes may vary, classrooms not always accessible for disabled students

- Advantages: Ease of picking up on signs a student is struggling, more personal interaction among students

- Disadvantages: May be harder for students to approach teacher privately in person to raise issues

An essay that concerns a specific problem (practical or theoretical) may be structured according to the problems-methods-solutions approach.

This is just what it sounds like: You define the problem, characterize a method or theory that may solve it, and finally analyze the problem, using this method or theory to arrive at a solution. If the problem is theoretical, the solution might be the analysis you present in the essay itself; otherwise, you might just present a proposed solution.

The tabs below show a template for this structure and an example outline for an essay about the problem of fake news.

- Introduce the problem

- Provide background

- Describe your approach to solving it

- Define the problem precisely

- Describe why it’s important

- Indicate previous approaches to the problem

- Present your new approach, and why it’s better

- Apply the new method or theory to the problem

- Indicate the solution you arrive at by doing so

- Assess (potential or actual) effectiveness of solution

- Describe the implications

- Problem: The growth of “fake news” online

- Prevalence of polarized/conspiracy-focused news sources online

- Thesis statement: Rather than attempting to stamp out online fake news through social media moderation, an effective approach to combating it must work with educational institutions to improve media literacy

- Definition: Deliberate disinformation designed to spread virally online

- Popularization of the term, growth of the phenomenon

- Previous approaches: Labeling and moderation on social media platforms

- Critique: This approach feeds conspiracies; the real solution is to improve media literacy so users can better identify fake news

- Greater emphasis should be placed on media literacy education in schools

- This allows people to assess news sources independently, rather than just being told which ones to trust

- This is a long-term solution but could be highly effective

- It would require significant organization and investment, but would equip people to judge news sources more effectively

- Rather than trying to contain the spread of fake news, we must teach the next generation not to fall for it

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Signposting means guiding the reader through your essay with language that describes or hints at the structure of what follows. It can help you clarify your structure for yourself as well as helping your reader follow your ideas.

The essay overview

In longer essays whose body is split into multiple named sections, the introduction often ends with an overview of the rest of the essay. This gives a brief description of the main idea or argument of each section.

The overview allows the reader to immediately understand what will be covered in the essay and in what order. Though it describes what comes later in the text, it is generally written in the present tense . The following example is from a literary analysis essay on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein .

Transitions

Transition words and phrases are used throughout all good essays to link together different ideas. They help guide the reader through your text, and an essay that uses them effectively will be much easier to follow.

Various different relationships can be expressed by transition words, as shown in this example.

Because Hitler failed to respond to the British ultimatum, France and the UK declared war on Germany. Although it was an outcome the Allies had hoped to avoid, they were prepared to back up their ultimatum in order to combat the existential threat posed by the Third Reich.

Transition sentences may be included to transition between different paragraphs or sections of an essay. A good transition sentence moves the reader on to the next topic while indicating how it relates to the previous one.

… Distance learning, then, seems to improve accessibility in some ways while representing a step backwards in others.

However , considering the issue of personal interaction among students presents a different picture.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarized in your thesis statement ) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

Comparisons in essays are generally structured in one of two ways:

- The alternating method, where you compare your subjects side by side according to one specific aspect at a time.

- The block method, where you cover each subject separately in its entirety.

It’s also possible to combine both methods, for example by writing a full paragraph on each of your topics and then a final paragraph contrasting the two according to a specific metric.

You should try to follow your outline as you write your essay . However, if your ideas change or it becomes clear that your structure could be better, it’s okay to depart from your essay outline . Just make sure you know why you’re doing so.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Structure an Essay | Tips & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 19, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/essay-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, how to write the body of an essay | drafting & redrafting, transition sentences | tips & examples for clear writing, what is your plagiarism score.

Body Paragraph

Definition of body paragraph, components of a body paragraph, different between an introduction and a body paragraph, examples of body paragraph in literature, example #1: autobiography of bertrand russell (by bertrand russell).

“Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind. These passions, like great winds, have blown me hither and thither, in a wayward course, over a great ocean of anguish, reaching to the very verge of despair. I have sought love, first, because it brings ecstasy – ecstasy so great that I would often have sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of this joy. I have sought it, next, because it relieves loneliness – that terrible loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss. I have sought it finally, because in the union of love I have seen, in a mystic miniature, the prefiguring vision of the heaven that saints and poets have imagined. This is what I sought, and though it might seem too good for human life, this is what – at last – I have found.”

Example #2: Politics and the English Language (by George Orwell)

“The inflated style itself is a kind of euphemism . A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow , blurring the outline and covering up all the details. The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms , like a cuttlefish spurting out ink. In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics.’ All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred, and schizophrenia. When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer. I should expect to find — this is a guess which I have not sufficient knowledge to verify — that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.”

Function of Body Paragraph

Related posts:, post navigation.

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

| {{item.snippet}} |

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement

- Giving Opportunities

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

Traditional Academic Essays In Three Parts

Part i: the introduction.

An introduction is usually the first paragraph of your academic essay. If you’re writing a long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to introduce your topic to your reader. A good introduction does 2 things:

- Gets the reader’s attention. You can get a reader’s attention by telling a story, providing a statistic, pointing out something strange or interesting, providing and discussing an interesting quote, etc. Be interesting and find some original angle via which to engage others in your topic.

- Provides a specific and debatable thesis statement. The thesis statement is usually just one sentence long, but it might be longer—even a whole paragraph—if the essay you’re writing is long. A good thesis statement makes a debatable point, meaning a point someone might disagree with and argue against. It also serves as a roadmap for what you argue in your paper.

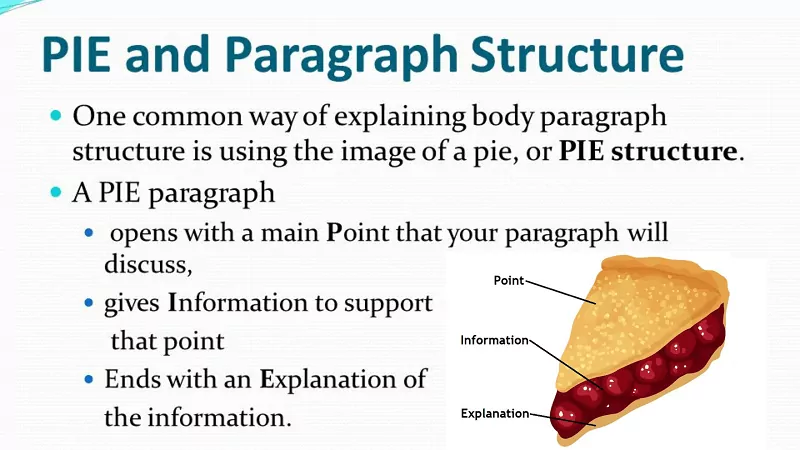

Part II: The Body Paragraphs

Body paragraphs help you prove your thesis and move you along a compelling trajectory from your introduction to your conclusion. If your thesis is a simple one, you might not need a lot of body paragraphs to prove it. If it’s more complicated, you’ll need more body paragraphs. An easy way to remember the parts of a body paragraph is to think of them as the MEAT of your essay:

Main Idea. The part of a topic sentence that states the main idea of the body paragraph. All of the sentences in the paragraph connect to it. Keep in mind that main ideas are…

- like labels. They appear in the first sentence of the paragraph and tell your reader what’s inside the paragraph.

- arguable. They’re not statements of fact; they’re debatable points that you prove with evidence.

- focused. Make a specific point in each paragraph and then prove that point.

Evidence. The parts of a paragraph that prove the main idea. You might include different types of evidence in different sentences. Keep in mind that different disciplines have different ideas about what counts as evidence and they adhere to different citation styles. Examples of evidence include…

- quotations and/or paraphrases from sources.

- facts , e.g. statistics or findings from studies you’ve conducted.

- narratives and/or descriptions , e.g. of your own experiences.

Analysis. The parts of a paragraph that explain the evidence. Make sure you tie the evidence you provide back to the paragraph’s main idea. In other words, discuss the evidence.

Transition. The part of a paragraph that helps you move fluidly from the last paragraph. Transitions appear in topic sentences along with main ideas, and they look both backward and forward in order to help you connect your ideas for your reader. Don’t end paragraphs with transitions; start with them.

Keep in mind that MEAT does not occur in that order. The “ T ransition” and the “ M ain Idea” often combine to form the first sentence—the topic sentence—and then paragraphs contain multiple sentences of evidence and analysis. For example, a paragraph might look like this: TM. E. E. A. E. E. A. A.

Part III: The Conclusion

A conclusion is the last paragraph of your essay, or, if you’re writing a really long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to conclude. A conclusion typically does one of two things—or, of course, it can do both:

- Summarizes the argument. Some instructors expect you not to say anything new in your conclusion. They just want you to restate your main points. Especially if you’ve made a long and complicated argument, it’s useful to restate your main points for your reader by the time you’ve gotten to your conclusion. If you opt to do so, keep in mind that you should use different language than you used in your introduction and your body paragraphs. The introduction and conclusion shouldn’t be the same.

- For example, your argument might be significant to studies of a certain time period .

- Alternately, it might be significant to a certain geographical region .

- Alternately still, it might influence how your readers think about the future . You might even opt to speculate about the future and/or call your readers to action in your conclusion.

Handout by Dr. Liliana Naydan. Do not reproduce without permission.

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Body Paragraphs

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Body paragraphs: Moving from general to specific information

Your paper should be organized in a manner that moves from general to specific information. Every time you begin a new subject, think of an inverted pyramid - The broadest range of information sits at the top, and as the paragraph or paper progresses, the author becomes more and more focused on the argument ending with specific, detailed evidence supporting a claim. Lastly, the author explains how and why the information she has just provided connects to and supports her thesis (a brief wrap-up or warrant).

Moving from General to Specific Information

The four elements of a good paragraph (TTEB)

A good paragraph should contain at least the following four elements: T ransition, T opic sentence, specific E vidence and analysis, and a B rief wrap-up sentence (also known as a warrant ) –TTEB!

- A T ransition sentence leading in from a previous paragraph to assure smooth reading. This acts as a hand-off from one idea to the next.

- A T opic sentence that tells the reader what you will be discussing in the paragraph.

- Specific E vidence and analysis that supports one of your claims and that provides a deeper level of detail than your topic sentence.

- A B rief wrap-up sentence that tells the reader how and why this information supports the paper’s thesis. The brief wrap-up is also known as the warrant. The warrant is important to your argument because it connects your reasoning and support to your thesis, and it shows that the information in the paragraph is related to your thesis and helps defend it.

Supporting evidence (induction and deduction)

Induction is the type of reasoning that moves from specific facts to a general conclusion. When you use induction in your paper, you will state your thesis (which is actually the conclusion you have come to after looking at all the facts) and then support your thesis with the facts. The following is an example of induction taken from Dorothy U. Seyler’s Understanding Argument :

There is the dead body of Smith. Smith was shot in his bedroom between the hours of 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m., according to the coroner. Smith was shot with a .32 caliber pistol. The pistol left in the bedroom contains Jones’s fingerprints. Jones was seen, by a neighbor, entering the Smith home at around 11:00 p.m. the night of Smith’s death. A coworker heard Smith and Jones arguing in Smith’s office the morning of the day Smith died.

Conclusion: Jones killed Smith.

Here, then, is the example in bullet form:

- Conclusion: Jones killed Smith

- Support: Smith was shot by Jones’ gun, Jones was seen entering the scene of the crime, Jones and Smith argued earlier in the day Smith died.

- Assumption: The facts are representative, not isolated incidents, and thus reveal a trend, justifying the conclusion drawn.

When you use deduction in an argument, you begin with general premises and move to a specific conclusion. There is a precise pattern you must use when you reason deductively. This pattern is called syllogistic reasoning (the syllogism). Syllogistic reasoning (deduction) is organized in three steps:

- Major premise

- Minor premise

In order for the syllogism (deduction) to work, you must accept that the relationship of the two premises lead, logically, to the conclusion. Here are two examples of deduction or syllogistic reasoning:

- Major premise: All men are mortal.

- Minor premise: Socrates is a man.

- Conclusion: Socrates is mortal.

- Major premise: People who perform with courage and clear purpose in a crisis are great leaders.

- Minor premise: Lincoln was a person who performed with courage and a clear purpose in a crisis.

- Conclusion: Lincoln was a great leader.

So in order for deduction to work in the example involving Socrates, you must agree that (1) all men are mortal (they all die); and (2) Socrates is a man. If you disagree with either of these premises, the conclusion is invalid. The example using Socrates isn’t so difficult to validate. But when you move into more murky water (when you use terms such as courage , clear purpose , and great ), the connections get tenuous.

For example, some historians might argue that Lincoln didn’t really shine until a few years into the Civil War, after many Union losses to Southern leaders such as Robert E. Lee.

The following is a clear example of deduction gone awry:

- Major premise: All dogs make good pets.

- Minor premise: Doogle is a dog.

- Conclusion: Doogle will make a good pet.

If you don’t agree that all dogs make good pets, then the conclusion that Doogle will make a good pet is invalid.

When a premise in a syllogism is missing, the syllogism becomes an enthymeme. Enthymemes can be very effective in argument, but they can also be unethical and lead to invalid conclusions. Authors often use enthymemes to persuade audiences. The following is an example of an enthymeme:

If you have a plasma TV, you are not poor.

The first part of the enthymeme (If you have a plasma TV) is the stated premise. The second part of the statement (you are not poor) is the conclusion. Therefore, the unstated premise is “Only rich people have plasma TVs.” The enthymeme above leads us to an invalid conclusion (people who own plasma TVs are not poor) because there are plenty of people who own plasma TVs who are poor. Let’s look at this enthymeme in a syllogistic structure:

- Major premise: People who own plasma TVs are rich (unstated above).

- Minor premise: You own a plasma TV.

- Conclusion: You are not poor.

To help you understand how induction and deduction can work together to form a solid argument, you may want to look at the United States Declaration of Independence. The first section of the Declaration contains a series of syllogisms, while the middle section is an inductive list of examples. The final section brings the first and second sections together in a compelling conclusion.

Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

Peter Dazeley / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The body paragraphs are the part of an essay , report , or speech that explains and develops the main idea (or thesis ). They come after the introduction and before the conclusion . The body is usually the longest part of an essay, and each body paragraph may begin with a topic sentence to introduce what the paragraph will be about.

Taken together, they form the support for your thesis, stated in your introduction. They represent the development of your idea, where you present your evidence.

"The following acronym will help you achieve the hourglass structure of a well-developed body paragraph:

- T opic Sentence (a sentence that states the one point the paragraph will make)

- A ssertion statements (statements that present your ideas)

- e X ample(s) (specific passages, factual material, or concrete detail)

- E xplanation (commentary that shows how the examples support your assertion)

- S ignificance (commentary that shows how the paragraph supports the thesis statement).

TAXES gives you a formula for building the supporting paragraphs in a thesis-driven essay." (Kathleen Muller Moore and Susie Lan Cassel, Techniques for College Writing: The Thesis Statement and Beyond . Wadsworth, 2011)

Organization Tips

Aim for coherence to your paragraphs. They should be cohesive around one point. Don't try to do too much and cram all your ideas in one place. Pace your information for your readers, so that they can understand your points individually and follow how they collectively relate to your main thesis or topic.

Watch for overly long paragraphs in your piece. If, after drafting, you realize that you have a paragraph that extends for most of a page, examine each sentence's topic, and see if there is a place where you can make a natural break, where you can group the sentences into two or more paragraphs. Examine your sentences to see if you're repeating yourself, making the same point in two different ways. Do you need both examples or explanations?

Paragraph Caveats

A body paragraph doesn't always have to have a topic sentence. A formal report or paper is more likely to be structured more rigidly than, say, a narrative or creative essay, because you're out to make a point, persuade, show evidence backing up an idea, or report findings.

Next, a body paragraph will differ from a transitional paragraph , which serves as a short bridge between sections. When you just go from paragraph to paragraph within a section, you likely will just need a sentence at the end of one to lead the reader to the next, which will be the next point that you need to make to support the main idea of the paper.

Examples of Body Paragraphs in Student Essays

Completed examples are often useful to see, to give you a place to start analyzing and preparing for your own writing. Check these out:

- How to Catch River Crabs (paragraphs 2 and 3)

- Learning to Hate Mathematics (paragraphs 2-4)

- Rhetorical Analysis of U2's "Sunday Bloody Sunday" (paragraphs 2-13)

- Understanding General-to-Specific Order in Composition

- Development in Composition: Building an Essay

- Definition and Examples of Transitional Paragraphs

- Padding and Composition

- Definition and Examples of Paragraph Breaks in Prose

- Definition and Examples of Climactic Order in Composition and Speech

- Understanding Organization in Composition and Speech

- Conclusion in Compositions

- Unity in Composition

- Paragraph Length in Compositions and Reports

- A Critical Analysis of George Orwell's 'A Hanging'

- Definition and Examples of Spacing in Composition

- Best Practices for the Most Effective Use of Paragraphs

- 7 Secrets to Success in English 101

- The Parts of a Speech in Classical Rhetoric

- Definition and Examples of Paragraphing in Essays

Essay writing: Main body

- Introductions

- Conclusions

- Analysing questions

- Planning & drafting

- Revising & editing

- Proofreading

- Essay writing videos

Jump to content on this page:

“An appropriate use of paragraphs is an essential part of writing coherent and well-structured essays.” Don Shiach, How to write essays

The main body of your essay is where you deliver your argument . Its building blocks are well structured, academic paragraphs. Each paragraph is in itself an individual argument and when put together they should form a clear narrative that leads the reader to the inevitability of your conclusion.

The importance of the paragraph

A good academic paragraph is a special thing. It makes a clear point, backed up by good quality academic evidence, with a clear explanation of how the evidence supports the point and why the point is relevant to your overall argument which supports your position . When these paragraphs are put together with appropriate links, there is a logical flow that takes the reader naturally to your essay's conclusion.

As a general rule there should be one clear key point per paragraph , otherwise your reader could become overwhelmed with evidence that supports different points and makes your argument harder to follow. If you follow the basic structure below, you will be able to build effective paragraphs and so make the main body of your essay deliver on what you say it will do in your introduction.

Paragraph structure

- A topic sentence – what is the overall point that the paragraph is making?

- Evidence that supports your point – this is usually your cited material.

- Explanation of why the point is important and how it helps with your overall argument.

- A link (if necessary) to the next paragraph (or to the previous one if coming at the beginning of the paragraph) or back to the essay question.

This is a good order to use when you are new to writing academic essays - but as you get more accomplished you can adapt it as necessary. The important thing is to make sure all of these elements are present within the paragraph.

The sections below explain more about each of these elements.

The topic sentence (Point)

This should appear early in the paragraph and is often, but not always, the first sentence. It should clearly state the main point that you are making in the paragraph. When you are planning essays, writing down a list of your topic sentences is an excellent way to check that your argument flows well from one point to the next.

This is the evidence that backs up your topic sentence. Why do you believe what you have written in your topic sentence? The evidence is usually paraphrased or quoted material from your reading . Depending on the nature of the assignment, it could also include:

- Your own data (in a research project for example).

- Personal experiences from practice (especially for Social Care, Health Sciences and Education).

- Personal experiences from learning (in a reflective essay for example).

Any evidence from external sources should, of course, be referenced.

Explanation (analysis)

This is the part of your paragraph where you explain to your reader why the evidence supports the point and why that point is relevant to your overall argument. It is where you answer the question 'So what?'. Tell the reader how the information in the paragraph helps you answer the question and how it leads to your conclusion. Your analysis should attempt to persuade the reader that your conclusion is the correct one.

These are the parts of your paragraphs that will get you the higher marks in any marking scheme.

Links are optional but it will help your argument flow if you include them. They are sentences that help the reader understand how the parts of your argument are connected . Most commonly they come at the end of the paragraph but they can be equally effective at the beginning of the next one. Sometimes a link is split between the end of one paragraph and the beginning of the next (see the example paragraph below).

Paragraph structure video

Length of a paragraph

Academic paragraphs are usually between 200 and 300 words long (they vary more than this but it is a useful guide). The important thing is that they should be long enough to contain all the above material. Only move onto a new paragraph if you are making a new point.

Many students make their paragraphs too short (because they are not including enough or any analysis) or too long (they are made up of several different points).

Example of an academic paragraph

Using storytelling in educational settings can enable educators to connect with their students because of inborn tendencies for humans to listen to stories. Written languages have only existed for between 6,000 and 7,000 years (Daniels & Bright, 1995) before then, and continually ever since in many cultures, important lessons for life were passed on using the oral tradition of storytelling. These varied from simple informative tales, to help us learn how to find food or avoid danger, to more magical and miraculous stories designed to help us see how we can resolve conflict and find our place in society (Zipes, 2012). Oral storytelling traditions are still fundamental to native American culture and Rebecca Bishop, a native American public relations officer (quoted in Sorensen, 2012) believes that the physical act of storytelling is a special thing; children will automatically stop what they are doing and listen when a story is told. Professional communicators report that this continues to adulthood (Simmons, 2006; Stevenson, 2008). This means that storytelling can be a powerful tool for connecting with students of all ages in a way that a list of bullet points in a PowerPoint presentation cannot. The emotional connection and innate, almost hardwired, need to listen when someone tells a story means that educators can teach memorable lessons in a uniquely engaging manner that is common to all cultures.

The cross-cultural element of storytelling can be seen when reading or listening to wisdom tales from around the world...

Key: Topic sentence Evidence (includes some analysis) Analysis Link (crosses into next paragraph)

- << Previous: Introductions

- Next: Conclusions >>

- Last Updated: Jul 4, 2024 10:15 AM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/essays

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

- Place order

Parts of a Body Paragraph in an Essay, Assignment, or any Paper

Whether you are writing an essay, thesis, research dissertation, report, proposal, college essay, or personal statement, you must write the body paragraphs at some point. The body paragraphs come immediately after the introduction paragraph.

Majorly, professors, markers, and instructors can tell good writing just by reading a few components of the body paragraphs.

Body paragraphs are the building blocks of essays and other papers written in prose form. They provide all the information and reasoning to prove the thesis statement.

Without wasting too much time, let�s delve into what elements make a body paragraph, how to craft the best paragraphs, and some tips you can use when stuck.

Purpose of Writing a Body Paragraph

Body paragraphs play a critical role in proving the thesis of an essay or paper. As a matter of sequence, the body paragraphs come after the introduction and just before the concluding paragraph of an essay or paper.

The body paragraphs fulfill the predictions made in the introduction and give room for the summary in the conclusion. Therefore, the body paragraphs must relate to what comes before them and what comes after.

Eliminating a body paragraph from the sequence of body paragraphs without altering the flow means that you derailed when writing. Furthermore, it is a solid signal for editing, proofreading, and, if possible, rewriting the paragraph. Technically, body paragraphs link to one another to support the thesis.

Each body paragraph must relate logically to the one immediately before ( introduction paragraph ) or after ( concluding paragraph ). It should only bear or focus on a single idea or topic reflected in the topic sentence. If your topic is complex or has multiple parts, you can split a paragraph into two to maintain this rule.

A paragraph is about 150 words in length and cannot be one sentence, especially in academia. As a result, one-sentence paragraphs are usually underdeveloped.

Essential Parts or Elements of a Good Body Paragraph

The body of your essay or paper is referred to as developmental paragraphs in the sense that it is the arena where all the action takes place. It is where you develop your central idea or thesis. Depending on the length of your paper, the number of body paragraphs will differ. For instance, if you are writing a one-page paper of 300-400 words, you can ideally have two well-balanced short body paragraphs. Similarly, when writing an essay from 500 to 1000 words, you can write at least three body paragraphs to support the thesis statement of your essay or paper.

The main components of a body paragraph of your essay or whatever written assignment you are undertaking are topic sentences, supporting sentences, transitions, and concluding sentences. Each of these elements works side by side with another to bring out the message of the entire body paragraph as a whole.

When you successfully marry every part to another, you end up with a solid body paragraph that supports the thesis statement of your essay or paper.

Components of a Good Body Paragraph

In a nutshell, we can break a good body paragraph into four main parts. Here is a breakdown of the four parts and the functions that each plays in the body paragraph:

- Transition - linking the body paragraphs to one another.

- Topic Sentence - introducing the paragraph.

- Supporting Sentences - Explain the topic sentence and support the thesis.

- Concluding Sentence/Summary - briefly summarize the paragraph and link/transition to the next paragraph.

Given that you now have a rough idea of each part, let's comprehensively explore all the components in detail to figure out how to use each when writing. In the following section, we explain each element of a good body paragraph in detail and give cogent reasons you should incorporate it when writing the developing paragraphs of your essays or papers.

1. Transitions

For you to achieve coherence, flow, and organization in an essay or paper, using transition words and phrases is inevitable. For example, when writing a body paragraph, it must have a transition sentence. Sometimes it comes just before the topic sentence, while you can incorporate it as part of the closing sentence.

Instead of opening a paragraph with an abrupt change of topic, you can use transitions to offer a soft landing to your readers. You slowly guide them into a new conversation that maintains a good flow of ideas. Transitions do a fantastic job of removing confusion and distractions when moving from one paragraph to the next.

The transition sentence is the one that leads from a previous paragraph to ensure that there is smooth reading or flow of ideas. It transitions you from the previous idea to another idea that is related to the former.

And the good thing is that transition phrases and signal words don't have to be complicated. Check out the list of transition or linking words to incorporate into your paragraphs.

2. Topic Sentence

It is also known as the opening sentence or key sentence .

The topic sentence is usually the first sentence of the paragraph. It is sometimes known as the opening sentence. It states one of the topics related to your thesis and bears assertions about how the topic supports the central idea.

A topic sentence serves two purposes:

- It ties the details of the paragraph together

- It relates the details of the paragraph to the thesis statement

It is usually a generalization you can support using evidence and facts when writing the essay. As a characteristic, the topic sentences are short and stand independently when the supporting details are stripped.

3. Supporting Sentences