Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Covid 19 — My Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic

My Experience During The Covid-19 Pandemic

- Categories: Covid 19

About this sample

Words: 440 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 440 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, physical impact, mental and emotional impact, social impact.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

- American Psychiatric Association. (2020). Mental health and COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/apa-blogs/apa-blog/2020/03/mental-health-and-covid-19

- The New York Times. (2020). Coping with Coronavirus Anxiety. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/well/family/coronavirus-anxiety-mental-health.html

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1417 words

2 pages / 876 words

2 pages / 985 words

3 pages / 1383 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Covid 19

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus, has had far-reaching consequences on individuals' lives worldwide. This essay will explore the personal impacts of the pandemic, focusing on mental and emotional [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic has left an indelible mark on the world, altering our daily lives in unprecedented ways. In this essay, I reflect upon my experiences during this global crisis, the challenges I faced, the lessons learned, [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the indispensable role of accurate information and scientific advancements in managing public health crises. In a time marked by uncertainty and fear, access to reliable data and ongoing [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic, a global crisis of unprecedented magnitude, has not only posed threats to physical health but has also had profound implications for mental well-being. This essay, titled "Impact of COVID-19 on Mental [...]

As a Computer Science student who never took Pre-Calculus and Basic Calculus in Senior High School, I never realized that there will be a relevance of Calculus in everyday life for a student. Before the beginning of it uses, [...]

Many countries are suggesting various levels of containment in order to prevent the spread of coronavirus or COVID-19. With these worries, schools and universities are closing down and moving abruptly to online platforms and [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- +44 (0) 207 391 9032

Recent Posts

- Why Is Your CV Getting Rejected and How to Avoid It

- Where to Find Images for Presentations

- What Is an Internship? Everything You Should Know

How Long Should a Thesis Statement Be?

- How to Write a Character Analysis Essay

- Best Colours for Your PowerPoint Presentation: Top Colour Combinations

- How to Write a Nursing Essay – With Examples

- Top 5 Essential Skills You Should Build As An International Student

- How Professional Editing Services Can Take Your Writing to the Next Level

- How to Write an Effective Essay Outline: Template & Structure Guide

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

How to write an essay on coronavirus (COVID-19)

(Last updated: 10 November 2021)

Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation service

We have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below.

With the coronavirus pandemic affecting every aspect of our lives for the last 18 months, it is no surprise that it has become a common topic in academic assignments. Writing a COVID-19 essay can be challenging, whether you're studying biology, philosophy, or any course in between.

Your first question might be, how would an essay about a pandemic be any different from a typical academic essay? Well, the answer is that in many ways it is largely similar. The key difference, however, is that this pandemic is much more current than usual academic topics. That means that it may be difficult to rely on past research to demonstrate your argument! As a result, COVID-19 essay writing needs to balance theories of past scholars with very current data (that is constantly changing).

In this post, we are going to give you our top tips on how to write a coronavirus academic essay, so that you are able to approach your writing with confidence and produce a great piece of work.

1. Do background reading

Critical reading is an essential component for any essay, but the question is – what should you be reading for a coronavirus essay? It might seem like a silly question, but the choices that you make during the reading process may determine how well you actually do on the paper. Therefore, we recommend the following steps.

First, read (and re-read) the assignment prompt that you have been given by the instructor. If you write an excellent essay, but it is off topic, you’ll likely be marked down. Make notes on the words that explain what is being asked of you – perhaps the essay asks you to “analyse”, “describe”, “list”, or “evaluate”. Make sure that these same words actually appear in your paper.

Second, look for specific things you have been instructed to do. This might include using themes from your textbook or incorporating assigned readings. Make a note of these things and read them first. Remember to take good notes while you read.

Once you have done your course readings, the question then becomes: what types of external readings are you going to need? Typically, at this point, you are going to be left with newspapers/websites, and a few scholarly articles (books on coronavirus might not be readily available at this stage, but could still be useful!). If it is a research essay, you are likely going to need to rely on a variety of sources as you work through this assignment. This might seem different than other academic writing where you would typically focus on only peer-reviewed articles or books. With coronavirus essays, there is a need for a more diverse set of sources, including;

Newspaper articles and websites

Just like with academic articles, not all newspaper articles and/or websites are created equal. Further, there are likely to be a variety of different statistics released, as the way that countries calculate coronavirus cases, deaths, and other components of the virus are not always the same.

Try to pick sources that are reputable. This might be reports done by key governmental organisations or even the World Health Organisation. If you are reading through an article and can identify obvious areas of bias, you may need to find alternate readings for your paper.

Academic articles

You may be surprised to discover the variety of articles published so far on COVID-19 - a lot can be achieved over multiple lockdowns! The research that has been done has been fairly extensive, covering a broad range of topics. Therefore, when preparing to write your academic essay, make sure to check the literature frequently as new publications are being released all the time.

If you do a search and you cannot find anything on the coronavirus specifically, you will have to widen your search. Think about the topic more widely. Are there theories that you have learned about in your classes that you can link to academic articles? Surely the answer must be yes! Just because there is limited research on this topic does not mean that you should avoid academic articles all together. Relying solely on websites or newspapers can lead you to a biased piece of writing, which usually is not what an academic essay is all about.

2. Plan your essay

Brainstorming.

Taking the time to brainstorm out your ideas can be the first step in a super successful essay. Brainstorming does not have to take a lot of time, and can be done in about 20 minutes if you have already done some background reading on the topic.

First, figure out how many points you need to identify. Each point is likely to equate to one paragraph of your paper, so if you are writing a 1500-word essay (and you use 300 words for the introduction and conclusion) you will be left with 1200 words, which means you will need between 5-6 paragraphs (and 5-6 points).

Start with a blank piece of paper. In the middle of the paper write the question or statement that you are trying to answer. From there, draw 5 or 6 lines out from the centre. At the end of each of these lines will be a point you want to address in your essay. From here, write down any additional ideas that you have.

It might look messy, but that’s OK! This is just the first step in the process and an opportunity for you to get your ideas down on paper. From this messiness, you can easily start to form a logical and linear outline that will soon become the template for your essay.

Creating an outline

Once you have a completed brainstorm, the next step is to put your ideas into a logical format The first step in this process is usually to write out a rough draft of the argument you are attempting to make. In doing this, you are then able to see how your subsequent paragraphs are addressing this topic (and if they are not addressing the topic, now is the time to change this!).

Once you have a position/argument/thesis statement, create space for your body paragraphs, but numbering each section. Then, write a rough draft of the topic sentence that you think will fit well in that section. Once you have done this, pull up the coronavirus articles, data, and other reports that you have read. Determine where each will fit best in your paper (and exclude the ones that do not fit well). Put a citation of the document in each paragraph section (this will make it easier to construct your reference list at the end).

Once every paragraph is organised, double check to make sure they are all still on track to address your main thesis. At this point you are ready to write an excellent and well-organised COVID-19 essay!

3. Structure your paragraphs

When structuring an academic essay on COVID-19, there will be a need to balance the news, evidence from academic articles, and course theory. This adds an extra layer of complexity because there are just so many things to juggle.

One strategy that can be helpful is to structure all your paragraphs in the same way. Now, you might be thinking, how boring! In reality, it is likely that the reader will appreciate the fact that you have carefully thought out your process and how you are going to approach this essay.

How to design your essay paragraphs

- Create a topic sentence. A topic sentence is a sentence that presents the main idea for the paragraph. Usually it links back to your thesis, argument, or position.

- Start to introduce your evidence. Use the next sentence in your introduction as a bridge between the topic sentence and the evidence/data you are going to present.

- Add evidence. Take 2-4 sentences to give the reader some good information that supports your topic sentence. This can be statistics, details from an empirical study, information from a news article, or some other form of information.

- Give some critical thought. It is essential to make a connection for the reader between your evidence and your topic sentence. Tell the reader why the information you have presented is important.

- Provide a concluding sentence. Make sure you wrap up your argument or transition to the next one.

4. Write your essay

Keep it academic.

There is a lot of information available about the coronavirus, but because much of it is coming from newspaper articles, the evidence that you might use for your paper can be skewed. In order to keep your paper academic, it is best to maintain a professional and academic style.

Present statistics from reputable sources (like the World Health Organisation), rather than those that have been selected by third parties. Furthermore, if you are writing a COVID-19 essay that is about a specific region (e.g. the United Kingdom), make sure that your statistics and evidence also come from this region.

Use up-to-date sources

The information on coronavirus is constantly changing. By now, everyone has seen the exponential curve of cases reoccurring all over the world at different times. Therefore, what was true last month may not necessarily be the case now. This can be challenging when you are planning an essay, because your outline from a previous week may need to be modified.

There are a number of ways you can address this. One way is, obviously, to continue going back and refreshing the data. Another way, which can be equally useful, is to outline the scope of the problem in your paper, writing something like, “data on COVID-19 is constantly changing, but the data presented was accurate at the time of writing”.

Avoid personal bias or opinion (unless asked!)

Everybody has an opinion – this opinion can often relate to how you or your family members have been affected by the pandemic (and the government response to this). People have lost jobs, have had to avoid family/friends, or have lost someone as a result of this pandemic. Life, for many, is very different.

While all of this is extremely important, it may not necessarily be relevant for an academic essay. One of the more challenging components of this type of academic paper is to try and remove yourself from the evidence you are providing. Now… there are exceptions. If you are writing a COVID-19 reflective essay, then it is your responsibility to include your opinion; otherwise, do your best to remain objective.

Avoid personal pronouns

Along the same lines as avoiding bias, it is also a good idea to avoid personal pronouns in your academic essay (except in a reflection, of course). This means avoiding words like “I, we, our, my”. While you may agree (or disagree) with the sentiment you are presenting, try and present your information from a distanced perspective.

Proofread carefully

Finally (and this is true of any essay), make sure that you take the time to proofread your essay carefully. Is it free from spelling errors? Have you checked the grammar? Have you made sure that your references are correct and in order? Have you carefully reviewed the submission requirements of your instructor (e.g. font, margins, spacing, etc.)? If the answer is yes, it sounds as if you are finally ready to submit your essay.

Final thoughts

Writing an essay is not easy. Writing an essay on a pandemic while living in that same pandemic is even more difficult.

A good essay is appropriately structured with a clear purpose and is presented according to the recommended guidelines. Unless it is a personal reflection, it attempts to present information as if it were free from bias.

So before you start to panic about having to write an essay about a pandemic, take a breath. You can do this. Take all the same steps as you would in a conventional academic essay, but expand your search to include relevant and up-to-date information that you know will make your essay a success. Once you have done this, make sure to have your university writing centre or an academic at Oxbridge Essays check it over and make suggestions! Now, stop reading and get writing! Good luck.

Essay exams: how to answer ‘To what extent…’

How to write a master’s essay, writing services.

- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- Journal Publication

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

Additional Services

- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies

- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Editing Service Examples

- [email protected]

- Contact Form

Payment Methods

Cryptocurrency payments.

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay On Covid-19: 100, 200 and 300 Words

- Updated on

- Apr 30, 2024

COVID-19, also known as the Coronavirus, is a global pandemic that has affected people all around the world. It first emerged in a lab in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 and quickly spread to countries around the world. This virus was reportedly caused by SARS-CoV-2. Since then, it has spread rapidly to many countries, causing widespread illness and impacting our lives in numerous ways. This blog talks about the details of this virus and also drafts an essay on COVID-19 in 100, 200 and 300 words for students and professionals.

Table of Contents

- 1 Essay On COVID-19 in English 100 Words

- 2 Essay On COVID-19 in 200 Words

- 3 Essay On COVID-19 in 300 Words

- 4 Short Essay on Covid-19

Essay On COVID-19 in English 100 Words

COVID-19, also known as the coronavirus, is a global pandemic. It started in late 2019 and has affected people all around the world. The virus spreads very quickly through someone’s sneeze and respiratory issues.

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on our lives, with lockdowns, travel restrictions, and changes in daily routines. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, we should wear masks, practice social distancing, and wash our hands frequently.

People should follow social distancing and other safety guidelines and also learn the tricks to be safe stay healthy and work the whole challenging time.

Also Read: National Safe Motherhood Day 2023

Essay On COVID-19 in 200 Words

COVID-19 also known as coronavirus, became a global health crisis in early 2020 and impacted mankind around the world. This virus is said to have originated in Wuhan, China in late 2019. It belongs to the coronavirus family and causes flu-like symptoms. It impacted the healthcare systems, economies and the daily lives of people all over the world.

The most crucial aspect of COVID-19 is its highly spreadable nature. It is a communicable disease that spreads through various means such as coughs from infected persons, sneezes and communication. Due to its easy transmission leading to its outbreaks, there were many measures taken by the government from all over the world such as Lockdowns, Social Distancing, and wearing masks.

There are many changes throughout the economic systems, and also in daily routines. Other measures such as schools opting for Online schooling, Remote work options available and restrictions on travel throughout the country and internationally. Subsequently, to cure and top its outbreak, the government started its vaccine campaigns, and other preventive measures.

In conclusion, COVID-19 tested the patience and resilience of the mankind. This pandemic has taught people the importance of patience, effort and humbleness.

Also Read : Essay on My Best Friend

Essay On COVID-19 in 300 Words

COVID-19, also known as the coronavirus, is a serious and contagious disease that has affected people worldwide. It was first discovered in late 2019 in Cina and then got spread in the whole world. It had a major impact on people’s life, their school, work and daily lives.

COVID-19 is primarily transmitted from person to person through respiratory droplets produced and through sneezes, and coughs of an infected person. It can spread to thousands of people because of its highly contagious nature. To cure the widespread of this virus, there are thousands of steps taken by the people and the government.

Wearing masks is one of the essential precautions to prevent the virus from spreading. Social distancing is another vital practice, which involves maintaining a safe distance from others to minimize close contact.

Very frequent handwashing is also very important to stop the spread of this virus. Proper hand hygiene can help remove any potential virus particles from our hands, reducing the risk of infection.

In conclusion, the Coronavirus has changed people’s perspective on living. It has also changed people’s way of interacting and how to live. To deal with this virus, it is very important to follow the important guidelines such as masks, social distancing and techniques to wash your hands. Getting vaccinated is also very important to go back to normal life and cure this virus completely.

Also Read: Essay on Abortion in English in 650 Words

Short Essay on Covid-19

Please find below a sample of a short essay on Covid-19 for school students:

Also Read: Essay on Women’s Day in 200 and 500 words

to write an essay on COVID-19, understand your word limit and make sure to cover all the stages and symptoms of this disease. You need to highlight all the challenges and impacts of COVID-19. Do not forget to conclude your essay with positive precautionary measures.

Writing an essay on COVID-19 in 200 words requires you to cover all the challenges, impacts and precautions of this disease. You don’t need to describe all of these factors in brief, but make sure to add as many options as your word limit allows.

The full form for COVID-19 is Corona Virus Disease of 2019.

Related Reads

Hence, we hope that this blog has assisted you in comprehending with an essay on COVID-19. For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Simran Popli

An avid writer and a creative person. With an experience of 1.5 years content writing, Simran has worked with different areas. From medical to working in a marketing agency with different clients to Ed-tech company, the journey has been diverse. Creative, vivacious and patient are the words that describe her personality.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

Writing about COVID-19 in a college admission essay

by: Venkates Swaminathan | Updated: September 14, 2020

Print article

For students applying to college using the CommonApp, there are several different places where students and counselors can address the pandemic’s impact. The different sections have differing goals. You must understand how to use each section for its appropriate use.

The CommonApp COVID-19 question

First, the CommonApp this year has an additional question specifically about COVID-19 :

Community disruptions such as COVID-19 and natural disasters can have deep and long-lasting impacts. If you need it, this space is yours to describe those impacts. Colleges care about the effects on your health and well-being, safety, family circumstances, future plans, and education, including access to reliable technology and quiet study spaces. Please use this space to describe how these events have impacted you.

This question seeks to understand the adversity that students may have had to face due to the pandemic, the move to online education, or the shelter-in-place rules. You don’t have to answer this question if the impact on you wasn’t particularly severe. Some examples of things students should discuss include:

- The student or a family member had COVID-19 or suffered other illnesses due to confinement during the pandemic.

- The candidate had to deal with personal or family issues, such as abusive living situations or other safety concerns

- The student suffered from a lack of internet access and other online learning challenges.

- Students who dealt with problems registering for or taking standardized tests and AP exams.

Jeff Schiffman of the Tulane University admissions office has a blog about this section. He recommends students ask themselves several questions as they go about answering this section:

- Are my experiences different from others’?

- Are there noticeable changes on my transcript?

- Am I aware of my privilege?

- Am I specific? Am I explaining rather than complaining?

- Is this information being included elsewhere on my application?

If you do answer this section, be brief and to-the-point.

Counselor recommendations and school profiles

Second, counselors will, in their counselor forms and school profiles on the CommonApp, address how the school handled the pandemic and how it might have affected students, specifically as it relates to:

- Grading scales and policies

- Graduation requirements

- Instructional methods

- Schedules and course offerings

- Testing requirements

- Your academic calendar

- Other extenuating circumstances

Students don’t have to mention these matters in their application unless something unusual happened.

Writing about COVID-19 in your main essay

Write about your experiences during the pandemic in your main college essay if your experience is personal, relevant, and the most important thing to discuss in your college admission essay. That you had to stay home and study online isn’t sufficient, as millions of other students faced the same situation. But sometimes, it can be appropriate and helpful to write about something related to the pandemic in your essay. For example:

- One student developed a website for a local comic book store. The store might not have survived without the ability for people to order comic books online. The student had a long-standing relationship with the store, and it was an institution that created a community for students who otherwise felt left out.

- One student started a YouTube channel to help other students with academic subjects he was very familiar with and began tutoring others.

- Some students used their extra time that was the result of the stay-at-home orders to take online courses pursuing topics they are genuinely interested in or developing new interests, like a foreign language or music.

Experiences like this can be good topics for the CommonApp essay as long as they reflect something genuinely important about the student. For many students whose lives have been shaped by this pandemic, it can be a critical part of their college application.

Want more? Read 6 ways to improve a college essay , What the &%$! should I write about in my college essay , and Just how important is a college admissions essay? .

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

The truth about homework in America

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

Introduction - Pandemic Preparedness | Lessons From COVID-19

Introduction.

- Recommendations

- Other Views

- Defense & Security

- Diplomacy & International Institutions

- Energy & Environment

- Human Rights

- Politics & Government

- Social Issues

- All Regions

- Europe & Eurasia

- Global Commons

- Middle East & North Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- More Explainers

- Backgrounders

- Special Projects

Research & Analysis

- All Research & Analysis

- Centers & Programs

- Books & Reports

- Independent Task Force Program

- Fellowships

Communities

- All Communities

- State & Local Officials

- Religion Leaders

- Local Journalists

- Lectureship Series

- Webinars & Conference Calls

- Member Login

- ForeignAffairs.com

- Co-chairs Sylvia Mathews Burwell and Frances Fragos Townsend

- Authors Thomas J. Bollyky and Stewart M. Patrick

- The work ahead—home

On December 31, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) contacted China about media reports of a cluster of viral pneumonias in Wuhan, later attributed to a coronavirus, now named SARS-CoV-2 . By January 30, 2020, scarcely a month later, WHO declared the virus to be a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC)—the highest alarm the organization can sound. Thirty days more and the pandemic was well underway; the coronavirus had spread to more than seventy countries and territories on six continents, and there were roughly ninety thousand confirmed cases worldwide of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

The COVID-19 pandemic is far from over and could yet evolve in unanticipated ways, but one of its most important lessons is already clear: preparation and early execution are essential in detecting, containing, and rapidly responding to and mitigating the spread of potentially dangerous emerging infectious diseases. The ability to marshal early action depends on nations and global institutions being prepared for the worst-case scenario of a severe pandemic and ready to execute on that preparedness The COVID-19 pandemic is far from over and could yet evolve in unanticipated ways, but one of its most important lessons is already clear: preparation and early execution are essential in detecting, containing, and rapidly responding to and mitigating the spread of potentially dangerous emerging infectious diseases. The ability to marshal early action depends on nations and global institutions being prepared for the worst-case scenario of a severe pandemic and ready to execute on that preparedness before that worst-case outcome is certain.

The rapid spread of the coronavirus and its devastating death toll and economic harm have revealed a failure of global and U.S. domestic preparedness and implementation, a lack of cooperation and coordination across nations, a breakdown of compliance with established norms and international agreements, and a patchwork of partial and mishandled responses. This pandemic has demonstrated the difficulty of responding effectively to emerging outbreaks in a context of growing geopolitical rivalry abroad and intense political partisanship at home.

Pandemic preparedness is a global public good. Infectious disease threats know no borders, and dangerous pathogens that circulate unabated anywhere are a risk everywhere. As the pandemic continues to unfold across the United States and world, the consequences of inadequate preparation and implementation are abundantly clear. Despite decades of various commissions highlighting the threat of global pandemics and international planning for their inevitability, neither the United States nor the broader international system were ready to execute those plans and respond to a severe pandemic. The result is the worst global catastrophe since World War II.

The lessons of this pandemic could go unheeded once life returns to a semblance of normalcy and COVID-19 ceases to menace nations around the globe. The United States and the world risk repeating many of the same mistakes that exacerbated this crisis, most prominently the failure to prioritize global health security, to invest in the essential domestic and international institutions and infrastructure required to achieve it, and to act quickly in executing a coherent response at both the national and the global level.

The goal of this report is to curtail that possibility by identifying what went wrong in the early national and international responses to the coronavirus pandemic and by providing a road map for the United States and the multilateral system to better prepare and execute in future waves of the current pandemic and when the next pandemic threat inevitably emerges. This report endeavors to preempt the next global health challenge before it becomes a disaster.

A Rapid Spread, a Grim Toll, and an Economic Disaster

On January 23, 2020, China’s government began to undertake drastic measures against the coronavirus, imposing a lockdown on Wuhan, a city of ten million people, aggressively testing, and forcibly rounding up potential carriers in makeshift quarantine centers. 1 In the subsequent days and weeks, the Chinese government extended containment to most of the country, sealing off cities and villages and mobilizing tens of thousands of health workers to contain and treat the disease. By the time those interventions began, however, the disease had already spread well beyond the country’s borders.

SARS-CoV-2 is a highly transmissible emerging infectious disease for which no highly effective treatments or vaccines currently exist and against which people have no preexisting immunity. Some nations have been successful so far in containing its spread through public health measures such as testing, contact tracing, and isolation of confirmed and suspected cases. Those nations have managed to keep the number of cases and deaths within their territories low.

More than one hundred countries implemented either a full or a partial shutdown in an effort to contain the spread of the virus and reduce pressure on their health systems. Although these measures to enforce physical distancing slowed the pace of infection, the societal and economic consequences in many nations have been grim. The supply chain for personal protective equipment (PPE), testing kits, and medical equipment such as oxygen treatment equipment and ventilators remains under immense pressure to meet global demand.

If international cooperation in response to COVID-19 has been occurring at the top levels of government, evidence of it has been scant, though technical areas such as data sharing have witnessed some notable successes. Countries have mostly gone their own ways, closing borders and often hoarding medical equipment. More than a dozen nations are competing in a biotechnology arms race to find a vaccine. A proposed international arrangement to ensure timely equitable access to the products of that biomedical innovation has yet to attract the necessary support from many vaccine-manufacturing nations, and many governments are now racing to cut deals with pharmaceutical firms and secure their own supplies.

As of August 31, 2020, the pandemic had infected at least twenty-five million people worldwide and killed at least 850,000 (both likely gross undercounts), including at least six million reported cases and 183,000 deaths in the United States. Meanwhile, the world economy had collapsed into a slump rivaling or surpassing the Great Depression, with unemployment rates averaging 8.4 percent in high-income economies. In the second quarter of 2020, the U.S gross domestic product (GDP) fell 9.5 percent, the largest quarterly decline in the nation’s history. 2

Already in May 2020, the Asia Development Bank estimated that the pandemic would cost the world $5.8 to 8.8 trillion, reducing global GDP in 2020 by 6.4 to 9.7 percent. The ultimate financial cost could be far higher. 3

The United States is among the countries most affected by the coronavirus, with about 24 percent of global cases (as of August 31) but just 4 percent of the world’s population. While many countries in Europe and Asia succeeded in driving down the rate of transmission in spring 2020, the United States experienced new spikes in infections in the summer because the absence of a national strategy left it to individual U.S. states to go their own way on reopening their economies. In the hardest-hit areas, U.S. hospitals with limited spare beds and intensive care unit capacity have struggled to accommodate the surge in COVID-19 patients. Resource-starved local and state public health departments have been unable to keep up with the staggering demand for case identification, contract tracing, and isolation required to contain the coronavirus’s spread.

A Failure to Heed Warnings

- Institute of Medicine, Microbial Threats to Health (1992)

- National Intelligence Estimate, The Global Infectious Disease Threat and Its Implications ...

This failing was not for any lack of warning of the dangers of pandemics. Indeed, many had sounded the alarm over the years. For nearly three decades, countless epidemiologists, public health specialists, intelligence community professionals, national security officials, and think tank experts have underscored the inevitability of a global pandemic of an emerging infectious disease. Starting with the Bill Clinton administration, successive administrations, including the current one, have included pandemic preparedness and response in their national security strategies. The U.S. government, foreign counterparts, and international agencies commissioned multiple scenarios and tabletop exercises that anticipated with uncanny accuracy the trajectory that a major outbreak could take, the complex national and global challenges it would create, and the glaring gaps and limitations in national and international capacity it would reveal.

The global health security community was almost uniformly in agreement that the most significant natural threat to population health and global security would be a respiratory virus—either a novel strain of influenza or a coronavirus that jumped from animals to humans. 4 Yet, for all this foresight and planning, national and international institutions alike have failed to rise to the occasion.

- National Intelligence Estimate, The Global Infectious Disease Threat and Its Implications for the United States (2000)

- Launch of the U.S. Global Health Security Initiative (2001)

- Institute of Medicine, Microbial Threats to Health: Emergence, Detection, and Response (2003)

- Revision of the International Health Regulations (2005)

- World Health Organization, Global Influenza Preparedness Plan (2005)

- Homeland Security Council, National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza (2005)

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Health Security Strategy of the United States of America (2009)

- U.S. Director of National Intelligence, Worldwide Threat Assessments (2009–2019)

- World Health Organization, Report of Review Committee on the Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in Relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 (2011)

- Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act of 2013

- Launch of the Global Health Security Agenda (2014)

- Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense (now Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense) (2015)

- National Security Strategy (2017)

- National Biodefense Strategy (2018)

- Crimson Contagion Simulation (2019)

- Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, A Work at Risk: Annual Report on Global Preparedness for Health Emergencies (2019)

- CSIS Commission, Ending the Cycle of Crisis and Complacency in U.S. Global Health Security (2019)

- U.S. National Health Security Strategy, 2019–2022 (2019)

- Global Health Security Index (2019)

Further Reading

Health-Systems Strengthening in the Age of COVID-19

By Angela E. Micah , Katherine Leach-Kemon , Joseph L Dieleman August 25, 2020

What Is the World Doing to Create a COVID-19 Vaccine?

By Claire Felter Aug 26, 2020

What Does the World Health Organization Do?

By CFR.org Editors Jun 1, 2020

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Newsletters

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

- Labor Day sales

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Online checking

- High-yield savings

- Money market

- Home equity loan

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Options pit

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

How to Write About the Impact of the Coronavirus in a College Essay

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many -- a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

[ Read: How to Write a College Essay. ]

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

[ Read: What Colleges Look for: 6 Ways to Stand Out. ]

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them -- and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

[ Read: The Common App: Everything You Need to Know. ]

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic -- and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

| {{item.snippet}} |

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement

- Giving Opportunities

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

Traditional Academic Essays In Three Parts

Part i: the introduction.

An introduction is usually the first paragraph of your academic essay. If you’re writing a long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to introduce your topic to your reader. A good introduction does 2 things:

- Gets the reader’s attention. You can get a reader’s attention by telling a story, providing a statistic, pointing out something strange or interesting, providing and discussing an interesting quote, etc. Be interesting and find some original angle via which to engage others in your topic.

- Provides a specific and debatable thesis statement. The thesis statement is usually just one sentence long, but it might be longer—even a whole paragraph—if the essay you’re writing is long. A good thesis statement makes a debatable point, meaning a point someone might disagree with and argue against. It also serves as a roadmap for what you argue in your paper.

Part II: The Body Paragraphs

Body paragraphs help you prove your thesis and move you along a compelling trajectory from your introduction to your conclusion. If your thesis is a simple one, you might not need a lot of body paragraphs to prove it. If it’s more complicated, you’ll need more body paragraphs. An easy way to remember the parts of a body paragraph is to think of them as the MEAT of your essay:

Main Idea. The part of a topic sentence that states the main idea of the body paragraph. All of the sentences in the paragraph connect to it. Keep in mind that main ideas are…

- like labels. They appear in the first sentence of the paragraph and tell your reader what’s inside the paragraph.

- arguable. They’re not statements of fact; they’re debatable points that you prove with evidence.

- focused. Make a specific point in each paragraph and then prove that point.

Evidence. The parts of a paragraph that prove the main idea. You might include different types of evidence in different sentences. Keep in mind that different disciplines have different ideas about what counts as evidence and they adhere to different citation styles. Examples of evidence include…

- quotations and/or paraphrases from sources.

- facts , e.g. statistics or findings from studies you’ve conducted.

- narratives and/or descriptions , e.g. of your own experiences.

Analysis. The parts of a paragraph that explain the evidence. Make sure you tie the evidence you provide back to the paragraph’s main idea. In other words, discuss the evidence.

Transition. The part of a paragraph that helps you move fluidly from the last paragraph. Transitions appear in topic sentences along with main ideas, and they look both backward and forward in order to help you connect your ideas for your reader. Don’t end paragraphs with transitions; start with them.

Keep in mind that MEAT does not occur in that order. The “ T ransition” and the “ M ain Idea” often combine to form the first sentence—the topic sentence—and then paragraphs contain multiple sentences of evidence and analysis. For example, a paragraph might look like this: TM. E. E. A. E. E. A. A.

Part III: The Conclusion

A conclusion is the last paragraph of your essay, or, if you’re writing a really long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to conclude. A conclusion typically does one of two things—or, of course, it can do both:

- Summarizes the argument. Some instructors expect you not to say anything new in your conclusion. They just want you to restate your main points. Especially if you’ve made a long and complicated argument, it’s useful to restate your main points for your reader by the time you’ve gotten to your conclusion. If you opt to do so, keep in mind that you should use different language than you used in your introduction and your body paragraphs. The introduction and conclusion shouldn’t be the same.

- For example, your argument might be significant to studies of a certain time period .

- Alternately, it might be significant to a certain geographical region .

- Alternately still, it might influence how your readers think about the future . You might even opt to speculate about the future and/or call your readers to action in your conclusion.

Handout by Dr. Liliana Naydan. Do not reproduce without permission.

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

I Thought We’d Learned Nothing From the Pandemic. I Wasn’t Seeing the Full Picture

M y first home had a back door that opened to a concrete patio with a giant crack down the middle. When my sister and I played, I made sure to stay on the same side of the divide as her, just in case. The 1988 film The Land Before Time was one of the first movies I ever saw, and the image of the earth splintering into pieces planted its roots in my brain. I believed that, even in my own backyard, I could easily become the tiny Triceratops separated from her family, on the other side of the chasm, as everything crumbled into chaos.

Some 30 years later, I marvel at the eerie, unexpected ways that cartoonish nightmare came to life – not just for me and my family, but for all of us. The landscape was already covered in fissures well before COVID-19 made its way across the planet, but the pandemic applied pressure, and the cracks broke wide open, separating us from each other physically and ideologically. Under the weight of the crisis, we scattered and landed on such different patches of earth we could barely see each other’s faces, even when we squinted. We disagreed viciously with each other, about how to respond, but also about what was true.

Recently, someone asked me if we’ve learned anything from the pandemic, and my first thought was a flat no. Nothing. There was a time when I thought it would be the very thing to draw us together and catapult us – as a capital “S” Society – into a kinder future. It’s surreal to remember those early days when people rallied together, sewing masks for health care workers during critical shortages and gathering on balconies in cities from Dallas to New York City to clap and sing songs like “Yellow Submarine.” It felt like a giant lightning bolt shot across the sky, and for one breath, we all saw something that had been hidden in the dark – the inherent vulnerability in being human or maybe our inescapable connectedness .

More from TIME

Read More: The Family Time the Pandemic Stole

But it turns out, it was just a flash. The goodwill vanished as quickly as it appeared. A couple of years later, people feel lied to, abandoned, and all on their own. I’ve felt my own curiosity shrinking, my willingness to reach out waning , my ability to keep my hands open dwindling. I look out across the landscape and see selfishness and rage, burnt earth and so many dead bodies. Game over. We lost. And if we’ve already lost, why try?

Still, the question kept nagging me. I wondered, am I seeing the full picture? What happens when we focus not on the collective society but at one face, one story at a time? I’m not asking for a bow to minimize the suffering – a pretty flourish to put on top and make the whole thing “worth it.” Yuck. That’s not what we need. But I wondered about deep, quiet growth. The kind we feel in our bodies, relationships, homes, places of work, neighborhoods.

Like a walkie-talkie message sent to my allies on the ground, I posted a call on my Instagram. What do you see? What do you hear? What feels possible? Is there life out here? Sprouting up among the rubble? I heard human voices calling back – reports of life, personal and specific. I heard one story at a time – stories of grief and distrust, fury and disappointment. Also gratitude. Discovery. Determination.

Among the most prevalent were the stories of self-revelation. Almost as if machines were given the chance to live as humans, people described blossoming into fuller selves. They listened to their bodies’ cues, recognized their desires and comforts, tuned into their gut instincts, and honored the intuition they hadn’t realized belonged to them. Alex, a writer and fellow disabled parent, found the freedom to explore a fuller version of herself in the privacy the pandemic provided. “The way I dress, the way I love, and the way I carry myself have both shrunk and expanded,” she shared. “I don’t love myself very well with an audience.” Without the daily ritual of trying to pass as “normal” in public, Tamar, a queer mom in the Netherlands, realized she’s autistic. “I think the pandemic helped me to recognize the mask,” she wrote. “Not that unmasking is easy now. But at least I know it’s there.” In a time of widespread suffering that none of us could solve on our own, many tended to our internal wounds and misalignments, large and small, and found clarity.

Read More: A Tool for Staying Grounded in This Era of Constant Uncertainty

I wonder if this flourishing of self-awareness is at least partially responsible for the life alterations people pursued. The pandemic broke open our personal notions of work and pushed us to reevaluate things like time and money. Lucy, a disabled writer in the U.K., made the hard decision to leave her job as a journalist covering Westminster to write freelance about her beloved disability community. “This work feels important in a way nothing else has ever felt,” she wrote. “I don’t think I’d have realized this was what I should be doing without the pandemic.” And she wasn’t alone – many people changed jobs , moved, learned new skills and hobbies, became politically engaged.

Perhaps more than any other shifts, people described a significant reassessment of their relationships. They set boundaries, said no, had challenging conversations. They also reconnected, fell in love, and learned to trust. Jeanne, a quilter in Indiana, got to know relatives she wouldn’t have connected with if lockdowns hadn’t prompted weekly family Zooms. “We are all over the map as regards to our belief systems,” she emphasized, “but it is possible to love people you don’t see eye to eye with on every issue.” Anna, an anti-violence advocate in Maine, learned she could trust her new marriage: “Life was not a honeymoon. But we still chose to turn to each other with kindness and curiosity.” So many bonds forged and broken, strengthened and strained.

Instead of relying on default relationships or institutional structures, widespread recalibrations allowed for going off script and fortifying smaller communities. Mara from Idyllwild, Calif., described the tangible plan for care enacted in her town. “We started a mutual-aid group at the beginning of the pandemic,” she wrote, “and it grew so quickly before we knew it we were feeding 400 of the 4000 residents.” She didn’t pretend the conditions were ideal. In fact, she expressed immense frustration with our collective response to the pandemic. Even so, the local group rallied and continues to offer assistance to their community with help from donations and volunteers (many of whom were originally on the receiving end of support). “I’ve learned that people thrive when they feel their connection to others,” she wrote. Clare, a teacher from the U.K., voiced similar conviction as she described a giant scarf she’s woven out of ribbons, each representing a single person. The scarf is “a collection of stories, moments and wisdom we are sharing with each other,” she wrote. It now stretches well over 1,000 feet.

A few hours into reading the comments, I lay back on my bed, phone held against my chest. The room was quiet, but my internal world was lighting up with firefly flickers. What felt different? Surely part of it was receiving personal accounts of deep-rooted growth. And also, there was something to the mere act of asking and listening. Maybe it connected me to humans before battle cries. Maybe it was the chance to be in conversation with others who were also trying to understand – what is happening to us? Underneath it all, an undeniable thread remained; I saw people peering into the mess and narrating their findings onto the shared frequency. Every comment was like a flare into the sky. I’m here! And if the sky is full of flares, we aren’t alone.

I recognized my own pandemic discoveries – some minor, others massive. Like washing off thick eyeliner and mascara every night is more effort than it’s worth; I can transform the mundane into the magical with a bedsheet, a movie projector, and twinkle lights; my paralyzed body can mother an infant in ways I’d never seen modeled for me. I remembered disappointing, bewildering conversations within my own family of origin and our imperfect attempts to remain close while also seeing things so differently. I realized that every time I get the weekly invite to my virtual “Find the Mumsies” call, with a tiny group of moms living hundreds of miles apart, I’m being welcomed into a pocket of unexpected community. Even though we’ve never been in one room all together, I’ve felt an uncommon kind of solace in their now-familiar faces.

Hope is a slippery thing. I desperately want to hold onto it, but everywhere I look there are real, weighty reasons to despair. The pandemic marks a stretch on the timeline that tangles with a teetering democracy, a deteriorating planet , the loss of human rights that once felt unshakable . When the world is falling apart Land Before Time style, it can feel trite, sniffing out the beauty – useless, firing off flares to anyone looking for signs of life. But, while I’m under no delusions that if we just keep trudging forward we’ll find our own oasis of waterfalls and grassy meadows glistening in the sunshine beneath a heavenly chorus, I wonder if trivializing small acts of beauty, connection, and hope actually cuts us off from resources essential to our survival. The group of abandoned dinosaurs were keeping each other alive and making each other laugh well before they made it to their fantasy ending.

Read More: How Ice Cream Became My Own Personal Act of Resistance

After the monarch butterfly went on the endangered-species list, my friend and fellow writer Hannah Soyer sent me wildflower seeds to plant in my yard. A simple act of big hope – that I will actually plant them, that they will grow, that a monarch butterfly will receive nourishment from whatever blossoms are able to push their way through the dirt. There are so many ways that could fail. But maybe the outcome wasn’t exactly the point. Maybe hope is the dogged insistence – the stubborn defiance – to continue cultivating moments of beauty regardless. There is value in the planting apart from the harvest.

I can’t point out a single collective lesson from the pandemic. It’s hard to see any great “we.” Still, I see the faces in my moms’ group, making pancakes for their kids and popping on between strings of meetings while we try to figure out how to raise these small people in this chaotic world. I think of my friends on Instagram tending to the selves they discovered when no one was watching and the scarf of ribbons stretching the length of more than three football fields. I remember my family of three, holding hands on the way up the ramp to the library. These bits of growth and rings of support might not be loud or right on the surface, but that’s not the same thing as nothing. If we only cared about the bottom-line defeats or sweeping successes of the big picture, we’d never plant flowers at all.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024

- Inside the Rise of Bitcoin-Powered Pools and Bathhouses

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What Makes a Friendship Last Forever?

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- Your Questions About Early Voting , Answered

- Column: Your Cynicism Isn’t Helping Anybody

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2021

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: an overview of systematic reviews

- Israel Júnior Borges do Nascimento 1 , 2 ,

- Dónal P. O’Mathúna 3 , 4 ,

- Thilo Caspar von Groote 5 ,

- Hebatullah Mohamed Abdulazeem 6 ,

- Ishanka Weerasekara 7 , 8 ,

- Ana Marusic 9 ,

- Livia Puljak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8467-6061 10 ,

- Vinicius Tassoni Civile 11 ,

- Irena Zakarija-Grkovic 9 ,

- Tina Poklepovic Pericic 9 ,

- Alvaro Nagib Atallah 11 ,

- Santino Filoso 12 ,

- Nicola Luigi Bragazzi 13 &

- Milena Soriano Marcolino 1

On behalf of the International Network of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (InterNetCOVID-19)

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 21 , Article number: 525 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

35 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Navigating the rapidly growing body of scientific literature on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is challenging, and ongoing critical appraisal of this output is essential. We aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

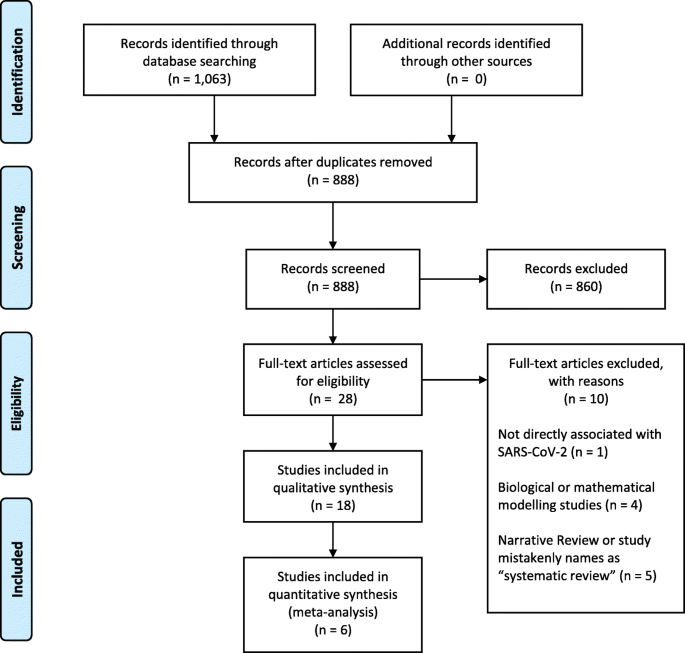

Nine databases (Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Sciences, PDQ-Evidence, WHO’s Global Research, LILACS, and Epistemonikos) were searched from December 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020. Systematic reviews analyzing primary studies of COVID-19 were included. Two authors independently undertook screening, selection, extraction (data on clinical symptoms, prevalence, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, diagnostic test assessment, laboratory, and radiological findings), and quality assessment (AMSTAR 2). A meta-analysis was performed of the prevalence of clinical outcomes.

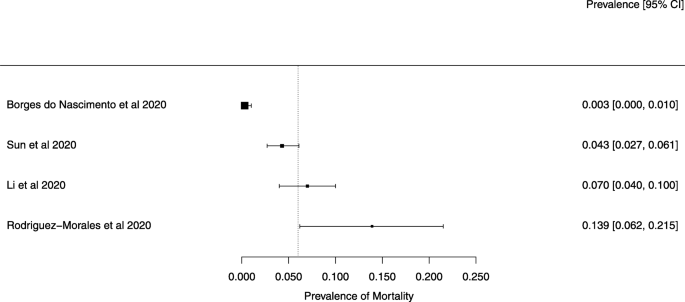

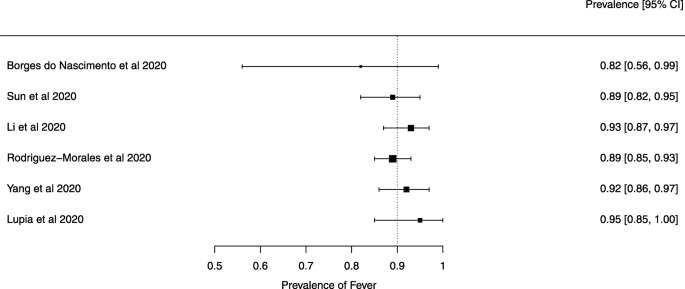

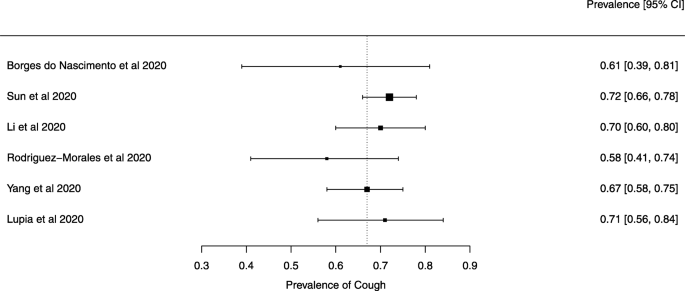

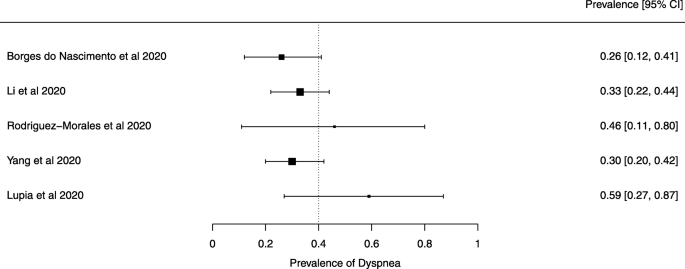

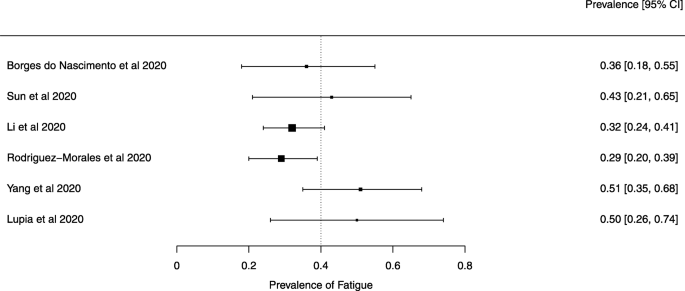

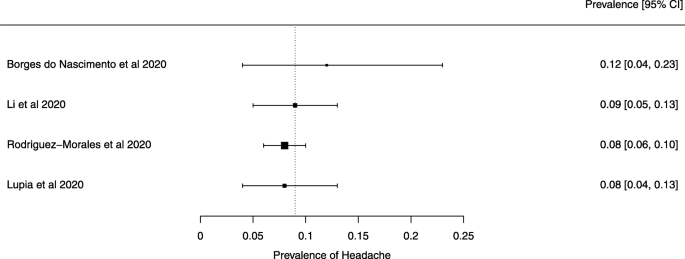

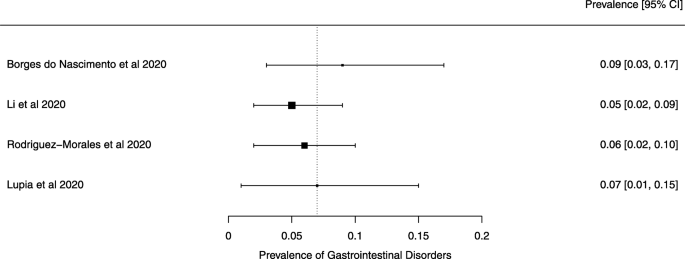

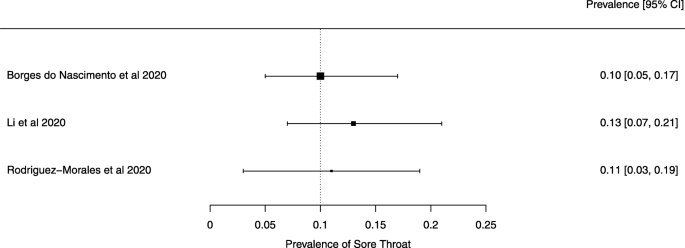

Eighteen systematic reviews were included; one was empty (did not identify any relevant study). Using AMSTAR 2, confidence in the results of all 18 reviews was rated as “critically low”. Identified symptoms of COVID-19 were (range values of point estimates): fever (82–95%), cough with or without sputum (58–72%), dyspnea (26–59%), myalgia or muscle fatigue (29–51%), sore throat (10–13%), headache (8–12%) and gastrointestinal complaints (5–9%). Severe symptoms were more common in men. Elevated C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase, and slightly elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, were commonly described. Thrombocytopenia and elevated levels of procalcitonin and cardiac troponin I were associated with severe disease. A frequent finding on chest imaging was uni- or bilateral multilobar ground-glass opacity. A single review investigated the impact of medication (chloroquine) but found no verifiable clinical data. All-cause mortality ranged from 0.3 to 13.9%.

Conclusions

In this overview of systematic reviews, we analyzed evidence from the first 18 systematic reviews that were published after the emergence of COVID-19. However, confidence in the results of all reviews was “critically low”. Thus, systematic reviews that were published early on in the pandemic were of questionable usefulness. Even during public health emergencies, studies and systematic reviews should adhere to established methodological standards.

Peer Review reports

The spread of the “Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2” (SARS-CoV-2), the causal agent of COVID-19, was characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 and has triggered an international public health emergency [ 1 ]. The numbers of confirmed cases and deaths due to COVID-19 are rapidly escalating, counting in millions [ 2 ], causing massive economic strain, and escalating healthcare and public health expenses [ 3 , 4 ].

The research community has responded by publishing an impressive number of scientific reports related to COVID-19. The world was alerted to the new disease at the beginning of 2020 [ 1 ], and by mid-March 2020, more than 2000 articles had been published on COVID-19 in scholarly journals, with 25% of them containing original data [ 5 ]. The living map of COVID-19 evidence, curated by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), contained more than 40,000 records by February 2021 [ 6 ]. More than 100,000 records on PubMed were labeled as “SARS-CoV-2 literature, sequence, and clinical content” by February 2021 [ 7 ].

Due to publication speed, the research community has voiced concerns regarding the quality and reproducibility of evidence produced during the COVID-19 pandemic, warning of the potential damaging approach of “publish first, retract later” [ 8 ]. It appears that these concerns are not unfounded, as it has been reported that COVID-19 articles were overrepresented in the pool of retracted articles in 2020 [ 9 ]. These concerns about inadequate evidence are of major importance because they can lead to poor clinical practice and inappropriate policies [ 10 ].

Systematic reviews are a cornerstone of today’s evidence-informed decision-making. By synthesizing all relevant evidence regarding a particular topic, systematic reviews reflect the current scientific knowledge. Systematic reviews are considered to be at the highest level in the hierarchy of evidence and should be used to make informed decisions. However, with high numbers of systematic reviews of different scope and methodological quality being published, overviews of multiple systematic reviews that assess their methodological quality are essential [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. An overview of systematic reviews helps identify and organize the literature and highlights areas of priority in decision-making.

In this overview of systematic reviews, we aimed to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in humans that were available at the beginning of the pandemic.

Methodology

Research question.

This overview’s primary objective was to summarize and critically appraise systematic reviews that assessed any type of primary clinical data from patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Our research question was purposefully broad because we wanted to analyze as many systematic reviews as possible that were available early following the COVID-19 outbreak.

Study design

We conducted an overview of systematic reviews. The idea for this overview originated in a protocol for a systematic review submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42020170623), which indicated a plan to conduct an overview.

Overviews of systematic reviews use explicit and systematic methods for searching and identifying multiple systematic reviews addressing related research questions in the same field to extract and analyze evidence across important outcomes. Overviews of systematic reviews are in principle similar to systematic reviews of interventions, but the unit of analysis is a systematic review [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

We used the overview methodology instead of other evidence synthesis methods to allow us to collate and appraise multiple systematic reviews on this topic, and to extract and analyze their results across relevant topics [ 17 ]. The overview and meta-analysis of systematic reviews allowed us to investigate the methodological quality of included studies, summarize results, and identify specific areas of available or limited evidence, thereby strengthening the current understanding of this novel disease and guiding future research [ 13 ].