- Corpus ID: 31614312

Capital Structure and Firm Performance

- Published 2012

- Business, Economics

6 Citations

Corporate financial risk analysis according to the constructal law: exploring the composition of liabilities to assets.

- Highly Influenced

Factors influencing debt financing and its effects on financial performance of state corporations in Kenya

Impact of financial structure on economic return (roa - return on asset); case study: wholesale of motor vehicle parts and accessories (nace: 4531), effect of director ’ s tunnelling on performance of quoted manufacturing companies in nigeria, the financing of high-tech smes: investigating the effects of capital structure on performance, the effect of capital budgeting decisions on the financial performance of manufacturing firms listed at the nse, 42 references, capital structure and corporate performance: evidence from jordan, a mean-variance theory of optimal capital structure and corporate debt capacity, impact of capital structure on firm’s value: evidence from bangladesh, the cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment, the determinants of capital structure choice, capital structure, equity ownership and firm performance, capital structure and ownership structure: a review of literature, corporate capital structure decisions: evidence from leveraged buyouts, an empirical test of the impact of managerial self-interest on corporate capital structure, what do we know about capital structure some evidence from international data, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

The relationship between capital structure and firm performance: the moderating role of agency cost.

1. Introduction

2. literature review, 2.1. theoretical approach, 2.2. hypothesis development, 2.2.1. the relationship between capital structure and financial performance, 2.2.2. the relationship between agency cost and firm performance, 2.2.3. the relationship between agency cost, capital structure, and firm performance, 3. materials and methods, 3.1. theoretical approach, 3.2. variables selection, 3.2.1. independent and moderator variables, 3.2.2. dependent variables, 3.2.3. control variables, 3.3. method and empirical model.

- Model 1 without moderation. R O A i t = β 0 + β 1 D T A i t + β 2 D T M C i t + β 3 A U R i t + β 4 C i t + E i t

- Model 1 with moderation. R O A i t = β 0 + β 1 D T A i t + β 2 D T M C i t + β 3 A U R i t + β 4 D T A i t × A U R i t + β 5 D T M C i t × A U R i t + β 6 C i t + E i t

- Model 2 without moderation. T Q i t = β 0 + β 1 D T A i t + β 2 D T M C i t + β 3 A U R i t + β 4 C i t + E i t

- Model 2 with moderation. T Q i t = β 0 + β 1 D T A i t + β 2 D T M C i t + β 3 A U R i t + β 4 D T A i t × A U R i t + β 5 D T M C i t × A U R i t + β 6 C i t + E i t

- Model 3 without moderation. E P S i t = β 0 + β 1 D T A i t + β 2 D T M C i t + β 3 A U R i t + β 4 C i t + E i t

- Model 3 with moderation. E P S i t = β 0 + β 1 D T A i t + β 2 D T M C i t + β 3 A U R i t + β 4 D T A i t × A U R i t + β 5 D T M C i t × A U R i t + β 6 C i t + E i t

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. descriptive results, 4.2. multicollinearity test, 4.3. heteroscedasticity test, 4.4. panel unit-root tests, 4.5. model specification, 4.6. regression results, 4.6.1. effect of capital structure on firm performance, 4.6.2. effect of agency cost on firm performance, 4.6.3. moderating effect of agency cost, 5. conclusions, author contributions, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Abdullah, Hariem. 2020. Capital Structure, Corporate Governance and Firm Performance Under IFRS Implementation. Ph.D. thesis, Near East University, Mersin, Turkey. (In Germany) [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abdullah, Hariem. 2021. Profitability and Leverage as Determinants of Dividend Policy: Evidence of Turkish Financial Firms. Eurasian Journal of Management & Social Sciences 2: 15–30. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abdullah, Hariem, and Turgut Tursoy. 2021. Capital structure and firm performance: Evidence of Germany under IFRS adoption. Review of Managerial Science 15: 379–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abdullah, Hariem, and Turgut Tursoy. 2023. The Effect of Corporate Governance on Financial Performance: Evidence from a Shareholder-Oriented System. Iranian Journal of Management Studies 16: 79–95. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abdullah, Hariem A., Heshoo G. Awrahman, and Hardi A. Omer. 2021. Effect of Working Capital Management on The Financial Performance of Banks (An Empirical Analysis for Banks Listed on The Iraq Stock Exchange). Qalaai Zanist Journal 6: 429–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abor, Joshua. 2007. Debt policy and performance of SMEs: Evidence from Ghanaian and South African firms. Journal of Risk Finance 8: 364–79. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Adair, Philippe, Mohamed Adaskou, and David McMillan. 2015. Trade-off theory vs. Pecking order theory and the determinants of corporate leverage: Evidence from a panel data analysis upon french SMEs (2002–2010). Cogent Economics and Finance 3: 1–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ahmad, Muhammad, Rabia Bashir, and Hamid Waqas. 2022. Working capital management and firm performance: Are their effects same in covid 19 compared to financial crisis 2008? Cogent Economics and Finance 10: 1–18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Albart, Nicko, Bonar Marulitua Sinaga, Perdana Wahyu Santosa, and Trias Andati. 2020. The Effect of Corporate Characteristics on Capital Structure in Indonesia. Journal of Economics, Business, & Accountancy Ventura 23: 46–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alexander, Onyango Allen. 2016. Effect of Capital Strucuture on Financial Performance: The Case of Banks Listed at The Nairobi Securities Exchange. Bachelor’s thesis, Strathmore University, Nairobi, Kenya. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11071/5061 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Al-Gamrh, Bakr, Ku Nor Izah Ku Ismail, Tanveer Ahsan, and Abdulsalam Alquhaif. 2020. Investment opportunities, corporate governance quality, and firm performance in the UAE. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 10: 261–76. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ali, Muhammad Nawzad, and Amanj Mohamed Ahmed. 2021. The Effect of Capital Structure on Financial Performance “Applied study in Turkish Stock Exchange”. Eurasian Journal of Management & Social Sciences 2: 43–57. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Al-Imam, Salahadin, and Mesa Hassan. 2019. The effect of capital structure on financial performance. Journal of AL_Turath University College 27: 189–212. Available online: https://www.iasj.net/iasj/article/201851 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Al-Kayed, Lama Tarek, Sharifah Raihan Syed Mohd Zain, and Jarita Duasa. 2014. The relationship between capital structure and performance of Islamic banks. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 5: 158–81. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Almustafa, Hamza, Quang Khai Nguyen, Jia Liu, and Van Cuong Dang. 2023. The impact of COVID-19 on firm risk and performance in MENA countries: Does national governance quality matter? PLoS ONE 18: e0281148. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Al-Taani, Khalaf. 2013. The Relationship between Capital Structure and Firm Performance: Evidence from Jordan. Journal of Finance and Accounting 1: 41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ang, James S., Rebel A. Cole, and James Wuh Lin. 2000. Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. The Journal of Finance 55: 81–106. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ayalew, Zemenu Amare, and David McMillan. 2021. Capital structure and profitability: Panel data evidence of private banks in Ethiopia. Cogent Economics and Finance 9: 1. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bae, John, Sang-Joon Kim, and Hannah Oh. 2017. Taming polysemous signals: The role of marketing intensity on the relationship between financial leverage and firm performance. Review of Financial Economics 33, 29–40 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baykara, Sule, and Betul Baykara. 2021. The impact of agency costs on firm performance: An analysis on BIST SME firms. Pressacademia 14: 28–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Berger, Allen N., and Emilia Bonaccorsi di Patti. 2006. Capital structure and firm performance: A new approach to testing agency theory and an application to the banking industry. Journal of Banking and Finance 30: 1065–102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Berle, Adolf A., Jr., and Gardiner Coit Means. 1932. The Modern Corporation and Private Property . New York: The Mcmillan Company. [ Google Scholar ]

- Booth, Laurence, Varouj A. Aivazian, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Vojislav Maksimovic. 2001. Capital structures in developing countries. Journal of Finance 56: 87–130. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Brooks, Chris. 2014. Introductory Econometrics for Finance , 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chi, Jianxin (Daniel). 2005. Understanding the endogeneity between firm value and shareholder rights. Financial Management 34: 65–76. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dang, Van Cuong, and Quang Khai Nguyen. 2021. Internal corporate gov-ernance and stock price crash risk: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment , 1–18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dawar, Varun. 2014. Agency Theory, Capital Structure and Firm Performance. Managerial Finance 40: 1190–206. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Demsetz, H., and K. Lehn. 1985. The Structure of Corporate Ownership: Causes and Consequences. Journal of Political Econom 93: 1155–77. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Diantimala, Yossi, Sofyan Syahnur, Ratna Mulyany, and Faisal Faisal. 2021. Firm size sensitivity on the correlation between financing choice and firm value. Cogent Business and Management 8: 1–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dickey, David A., and Wayne A. Fuller. 1979. Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. Journal of the American Statistical Association 74: 427–31. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Eldomiaty, Tarek I. 2008. Determinants of corporate capital structure: Evidence from an emerging economy. International Journal of Commerce and Management 17: 25–43. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- El-Sayed Ebaid, Ibrahim. 2009. The impact of capital-structure choice on firm performance: Empirical evidence from Egypt. Journal of Risk Finance 10: 477–87. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Grossman, Sanford J., and Oliver D. Hart. 1982. Corporate Financial Structure and Managerial Incentives. In The Economics of Information and Uncertainty . Edited by John J. McCall. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 107–40. Available online: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c4434 (accessed on 25 February 2023).

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis , 7th ed. London: Pearson Education. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harris, Richard D. F., and Elias Tzavalis. 1999. Inference for unit roots in dynamic panels where the time dimension is fixed. Journal of Econometrics 91: 201–26. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hasan, Bokhtiar, A. F. M. Mainul Ahsan, Afzalur Rahaman, and Nurul Alam. 2014. Influence of Capital Structure on Firm Performance: Evidence from Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management 9: 184–94. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Hoang, Le Duc, Tran Minh Tuan, Pham Van Tue Nha, and Ta Thu Phuong. 2019. Impact of agency costs on firm performance: Evidence from Vietnam. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies 10: 294–309. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ibhagui, Oyakhilome W., and Felicia O. Olokoyo. 2018. Leverage and firm performance: New evidence on the role of firm size. North American Journal of Economics and Finance 45: 57–82. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jabbary, Hossein, Zohreh Hajiha, and Roghaieh Hassanpour Labeshka. 2013. Investigation of the effect of agency costs on firm performance of listed firms in Tehran Stock Exchange. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Science 2: 771–76. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jensen, Michael C. 1986. Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeovers. The American Economic Review 76: 323–29. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1818789 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jouida, Sameh. 2018. Diversification, capital structure and profitability: A panel VAR approach. Research in International Business and Finance 45: 243–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kalash, İsmail. 2019. Firm leverage, agency costs and firm performance: An empirical research on service firms in Turkey. Journal of the Human and Social Sciences Researches 8: 624–36. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kontuš, Eleonora. 2021. Agency costs, capital structure and corporate performance. Ekonomski Vjesnik 34: 73–85. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Koop, Gary. 2008. Introduction to Econometrics . Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraus, Alan, and Robert Litzenberger. 1973. A State-Preference Model of Optimal financial leverage. Journal of Finance 28: 911–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Le, Thi Phuong Vy, and Thi Bich Nguyet Phan. 2017. Capital structure and firm performance: Empirical evidence from a small transition country. Research in International Business and Finance 42: 710–26. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Levin, Andrew, Chien-Fu Lin, and Chia-Shang James Chu. 2002. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics 108: 1–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Li, Hongxia, and Liming Cui. 2003. Empirical Study of Capital Structure on Agency Costs in Chinese Listed Firms. Nature and Science 1: 12–20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Li, Kang, Jyrki Niskanen, and Mervi Niskanen. 2019. Capital structure and firm performance in European SMEs: Does credit risk make a difference? Managerial Finance 45: 582–601. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Liang, Zhiqiang, Jianming Wei, Junyu Zhao, Haitao Liu, Baoqing Li, Jie Shen, and Chunlei Zheng. 2008. The statistical meaning of kurtosis and its new application to identification of persons based on seismic signals. Sensors 8: 5106–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Liu, Tiansen, Yufeng Zhang, and Dapeng Liang. 2019. Can ownership structure improve environmental performance in Chinese manufacturing firms? The moderating effect of financial performance. Journal of Cleaner Production 225: 58–71. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Mansyur, Andi, Abd. Rahman Mus, Zainuddin Rahman, and Suriyanti Suriyanti. 2020. Financial Performance as Mediator on the Impact of Capital Structure, Wealth Structure, Financial Structure on Stock Price: The Case of The Indonesian Banking Sector. European Journal of Business and Management Research 5: 1–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mardones, Juan Gallegos, and Gonzalo Ruiz Cuneo. 2020. Capital structure and performance in Latin American companies. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja 33: 2171–88. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Mehmood, Mudassar. 2021. Agency Costs and Performance of UK Universities. Public Organization Review 21: 187–204. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Miller, Merton H. 1977. Debt and Taxes. The Journal of Finance 32: 261–75. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1958. The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American Economic Review 48: 261–97. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1809766 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. 1963. Corporate Income Taxes and the Cost of Capital: A Correction. The American Economic Review 53: 433–43. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1809167 (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Myers, Stewart C. 1977. Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics 5: 147–75. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Myers, Stewart C. 1984. The Capital Structure Puzzle. The Journal of Finance 39: 575–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Myers, Stewart C., and Nicholas S. Majluf. 1984. Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics 13: 187–221. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Nachane, Dilip M. 2006. Econometrics: Theoretical Foundations and Empirical Perspectives. Journal of Quantitative Economics 4: 151–54. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Newbold, Paul, Betty Thorne, and William Lee Carlson. 2013. Statistics for Business and Economics , 8th ed. London: Pearson Education. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ngatno, Apriatni, P. Endang, and Arief Youlianto. 2021. Moderating effects of corporate governance mechanism on the relation between capital structure and firm performance. Cogent Business and Management 8: 1. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nguyen, An, and Phuong Hoang. 2022. The impact of corporate governance quality on capital structure choices: Does national governance quality matter? Cogent Economics and Finance 10: 1–26. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nidumolu, Radhika. 2018. Exploring the Effects of Agency Theory on Ownership Structures and Firm Performance. In Law and Economics: Breaking New Grounds . Working Paper. Lucknow: Eastern Book Company. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3809607 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Pandey, Krishna Dayal, and Tarak Nath Sahu. 2019. Debt Financing, Agency Cost and Firm Performance: Evidence from India. Vision 23: 267–74. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pham, Hanh Song Thi, and Hien Thi Tran. 2020. CSR disclosure and firm performance: The mediating role of corporate reputation and moderating role of CEO integrity. Journal of Business Research 120: 127–36. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Phuong, Thao Tran Thi, and Anh Thuy Nguyen. 2019. The Impact of Capital Structure on Firm Performance of Vietnamese Non-financial Listed Companies Based on Agency Cost Theory. VNU Journal of Science: Economics and Business 35: 24–33. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Porter, Dawn C., and Damodar N. Gujarati. 2009. Basic Econometrics , 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sadeghian, Nima Sepehr, Mohammad Mehdi Latifi, Saeed Soroush, and Zeinab Talebipour Aghabagher. 2012. Debt Policy and Corporate Performance: Empirical Evidence from Tehran Stock Exchange Companies. International Journal of Economics and Finance 4: 217–24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Sdiq, Shirwan Rafiq, and Hariem A. Abdullah. 2022. Examining the effect of agency cost on capital structure-financial performance nexus: Empirical evidence for emerging market. Cogent Economics and Finance 10: 1–16. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Seth, Himanshu, Saurabh Chadha, Satyendra Kumar Sharma, and Namita Ruparel. 2020. Exploring predictors of working capital management efficiency and their influence on firm performance: An integrated DEA-SEM approach. Benchmarking 28: 1120–45. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sheikh, Nadeem Ahmed, and Zongjun Wang. 2012. Effects of corporate governance on capital structure: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Corporate Governance (Bingley) 12: 629–41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sheikh, Nadeem Ahmed, and Zongjun Wang. 2013. The impact of capital structure on performance: An empirical study of non-financial listed firms in Pakistan. International Journal of Commerce and Management 23: 354–68. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shrestha, Ashish. 2020. Analysis of Capital Structure in Power Companies in Asian Economies: Analysis of Capital Structure in Power Companies in Asian Economies. MBA thesis, Kathmandu University, Dhulikhel, Nepal. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Siddik, Md Nur Alam, Sajal Kabiraj, and Shanmugan Joghee. 2017. Impacts of capital structure on performance of banks in a developing economy: Evidence from Bangladesh. International Journal of Financial Studies 5: 13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Thomsen, Steen, and Torben Pedersen. 2000. Ownership structure and economic performance in the largest European companies. Strategic Management Journal 21: 689–705. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tretiakova, V. V., M. S. Shalneva, and A. S. Lvov. 2021. The Relationship between Capital Structure and Financial Performance of the Company. SHS Web of Conferences 91: 01002. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, George. Yungchih. 2010. The Impacts of Free Cash Flows and Agency Costs on Firm Performance. Journal of Service Science and Management 3: 408–18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Williams, Joseph. 1987. Perquisites, Risk, and Capital Structure. The Journal of Finance 42: 29–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey. M. 1997. Multiplicative Panel Data Models Without the Strict Exogeneity Assumption. Econometric Theory 13: 667–78. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey. M. 2002. Econometrics Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data . Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey. M. 2015. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach , 6th ed. Boston: Cengage Learning. [ Google Scholar ]

- Xiao, Sheng, and Shan Zhao. 2014. How do agency problems affect firm value? - Evidence from China. European Journal of Finance 20: 803–28. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yoshikawa, Toru, and Phillip H. Phan. 2003. The performance implications of ownership-driven governance reform. European Management Journal 21: 698–706. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zeitun, Rami, and Gary Gang Tian. 2007. Capital Structure and Corporate Performance: Evidence from Jordan. The Australasian Accounting Business & Finance Journal 1: 40–61. [ Google Scholar ]

| No. | Sector or Industry | Number of Firms | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Food and beverage | 13 | 8.33 |

| 2 | Automobiles and their parts | 24 | 15.38 |

| 3 | Plastics and rubber | 6 | 3.85 |

| 4 | Electrical machinery | 5 | 3.21 |

| 5 | Petroleum products | 7 | 4.49 |

| 6 | Metallic minerals | 8 | 5.13 |

| 7 | Machinery and equipment | 9 | 5.77 |

| 8 | Other non-metallic mineral products | 8 | 5.13 |

| 9 | Ceramic tile | 6 | 3.85 |

| 10 | Basic metals | 17 | 10.90 |

| 11 | Medicinal products | 23 | 14.74 |

| 12 | Chemicals | 13 | 8.33 |

| 13 | Cement lime gypsum | 17 | 10.90 |

| Total | 156 | 100 |

| Variables | Notation | Proxies | Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Financial Performance | ROA | Return on Assets | Net Income/Total Assets |

| TQ | Tobin’s Q | (Market Value of Equity + Book Value of Debt)/Book Value of Assets | ||

| EPS | Earnings Per Share | Net Income/Number of Shares Outstanding | ||

| Explanatory Variable | Capital Structure | DTA | Debt to Assets | Total Debt/Total Assets |

| DTMC | Debt to Market Capitalization | Total Debt/(Total Debt + Market Capitalization) | ||

| Independent and Moderating Variable | Agency Cost | AUR | Asset Utilization Ratio | Annual Sales/Total Assets |

| Control Variable | SG | Sales Growth | Proportion of sales growth compared with the previous year | |

| AGE | Firm Age | Natural logarithm of number of years in service since established | ||

| OLS (FEM and CEM) | GLS (REM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Normality | No | Yes |

| Heteroscedasticity | Yes | No |

| Multicollinearity | Yes (independent variable more than 1) | Yes (independent variable more than 1) |

| Autocorrelation | No | No |

| ROA | TQ | EPS | DTA | DTMC | AUR | SG | AGE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.125 | 2.061 | 0.955 | 0.586 | 0.387 | 1.024 | 0.277 | 3.545 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.147 | 1.669 | 1.574 | 0.210 | 0.217 | 0.779 | 0.499 | 0.418 |

| Minimum | −0.540 | 0.583 | −6.278 | 0.036 | 0.01 | 0.058 | −0.825 | 1.945 |

| Maximum | 0.652 | 20.581 | 16.897 | 2.077 | 0.921 | 6.839 | 6.594 | 4.262 |

| Skewness | 0.440 | 4.415 | 3.481 | 0.616 | 0.303 | 3.347 | 4.233 | −0.734 |

| Kurtosis | 4.187 | 32.113 | 24.957 | 6.127 | 2.158 | 18.667 | 42.066 | 2.900 |

| Observations | 1404 | 1404 | 1404 | 1404 | 1404 | 1404 | 1404 | 1404 |

| ROA | TQ | EPS | DTA | DTMC | AUR | SG | AGE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 1 | |||||||

| TQ | 0.273 *** | 1 | ||||||

| EPS | 0.734 *** | 0.158 *** | 1 | |||||

| DTA | −0.648 *** | −0.181 *** | −0.318 *** | 1 | ||||

| DTMC | −0.631 *** | −0.586 *** | −0.377 *** | 0.516 ** | 1 | |||

| AUR | 0.064 ** | 0.076 *** | 0.027 | 0.066 ** | −0.021 | 1 | ||

| SG | 0.270 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.169 *** | −0.107 *** | −0.231 *** | 0.137 *** | 1 | |

| AGE | −0.136 *** | 0.044 * | −0.144 *** | 0.097 *** | 0.048 | −0.005 | 0.022 | 1 |

| Variables | VIF | Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| DTA | 2.112 | 0.474 |

| DTMC | 2.176 | 0.460 |

| AUR | 1.032 | 0.969 |

| SG | 1.083 | 0.923 |

| AGE | 1.012 | 0.989 |

| Mean | 1.483 |

| Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey | Model 1 (ROA) | Model 2 (TQ) | Model 3 (EPS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prob. Chi-Square (2) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Variables | Unit Root in | LLC | ADF-Fisher | HT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | Level | −24.44 *** | 358.43 ** | 29.17 *** |

| DTA | Level | −27.01 *** | 366.36 *** | 30.75 *** |

| DTMC | Level | −103.40 *** | 590.71 *** | 46.81 *** |

| AUR | Level | −29.91 *** | 347.57 * | 34.79 *** |

| SG | Level | −26.76 *** | 636.24 *** | 8.47 *** |

| AGE | Level | −55.33 *** | 1642.05 *** | 22.02 *** |

| Test Summary | Synopsis | Model 1 ROA | Model 2 TQ | Model 3 EPS | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagrange Multiplier Test Breusch–Pagan | REM | 1557.26 *** | 4523.42 *** | 1240.68 *** | H0 accepted |

| Chow Test Cross-section, Chi-square | FEM | 1138.24 *** | 192.45 ** | 1075.93 *** | H0 rejected |

| Hausman Test Cross-section random, Chi-square | FEM | 49.88 *** | 44.19 *** | 24.03 *** | H0 accepted |

| Variables | ROA | TQ | EPS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a (Without Moderation) | Model 1b (With Moderation) | Model 2a (Without Moderation) | Model 2b (With Moderation) | Model 3a (Without Moderation) | Model 3b (With Moderation) | |||||||

| Coef. | t-Stat. | Coef. | t-Stat. | Coef. | t-Stat. | Coef. | t-Stat. | Coef. | t-Stat. | Coef. | t-Stat. | |

| C | 0.834 *** | 9.43 | 0.814 *** | 9.22 | −2.754 * | −1.90 | −2.204 * | −1.54 | 3.345 *** | 2.66 | 3.318 *** | 2.62 |

| DTA | −0.310 *** | −17.17 | −0.249 *** | −9.66 | 3.304 *** | 11.15 | 1.550 *** | 3.70 | −1.858 *** | −7.21 | −1.748 *** | −4.73 |

| DTMC | −0.144 *** | −8.42 | −0.195 *** | −7.69 | −6.964 *** | −24.85 | −5.212 *** | −12.72 | −0.839 *** | −3.44 | −1.021 *** | −2.82 |

| AUR | 0.029 *** | 5.09 | 0.053 *** | 4.82 | −0.115 ** | 1.18 | −0.509 *** | −2.84 | 0.153 * | 1.88 | 0.171 | 1.08 |

| AUR*DTA | −0.064 *** | −3.26 | 1.845 *** | 5.80 | −0.113 | −0.40 | ||||||

| AUR*DTMC | 0.051 *** | 2.74 | −1.758 *** | −5.82 | 0.181 | 0.67 | ||||||

| SG | 0.053 *** | 12.18 | 0.052 *** | 11.95 | 0.443 *** | 6.22 | 0.478 *** | 6.79 | 0.408 *** | 6.60 | 0.404 *** | 6.50 |

| AGE | −0.145 *** | −6.02 | −0.145 *** | −6.06 | 1.505 *** | 3.81 | 1.502 *** | 3.87 | −0.351 | −1.02 | −0.347 | −1.01 |

| R-Square | 0.783 | 0.785 | 0.546 | 0.561 | 0.615 | 0.615 | ||||||

| Adjusted R-Square | 0.755 | 0.757 | 0.488 | 0.504 | 0.565 | 0.565 | ||||||

| F-statistic | 28.09 | 28.03 | 9.378 | 9.82 | 12.41 | 12.25 | ||||||

| Prob. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Ahmed, A.M.; Nugraha, D.P.; Hágen, I. The Relationship between Capital Structure and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Agency Cost. Risks 2023 , 11 , 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11060102

Ahmed AM, Nugraha DP, Hágen I. The Relationship between Capital Structure and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Agency Cost. Risks . 2023; 11(6):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11060102

Ahmed, Amanj Mohamed, Deni Pandu Nugraha, and István Hágen. 2023. "The Relationship between Capital Structure and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Agency Cost" Risks 11, no. 6: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11060102

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Corporate governance, capital structure, and firm performance: a panel VAR approach

- Original Article

- Published: 13 December 2022

- Volume 3 , article number 14 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Rishi Kapoor Ronoowah ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4152-5204 1 &

- Boopendra Seetanah ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1786-0675 2

6809 Accesses

Explore all metrics

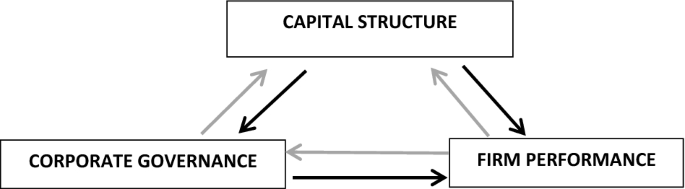

This study aims to examine the interrelationships and interdependencies between corporate governance (CG), capital structure (CS), and firm performance (FP) of companies listed on the Stock Exchange of Mauritius from 2009 to 2019 along with a comparison between financial and non-financial firms. A panel vector autoregression (PVAR) approach is used in this study to determine the relationship dynamics between CG, CS and FP. The findings reveal a positive and significant bidirectional association between CS and FP, supporting the trade-off theory. The results also show that CG and FP jointly help to increase CS while CG and CS jointly boost the profitability of firms. A strong bidirectional relationship with varied signs between CG and CS is found only for financial firms. The results of the forecast error variance decomposition analysis support the selection of FP as the most endogenous variable. Robustness tests also support the findings. This study is the first to examine the dynamic and interdependent relationships using a PVAR model between CG, CS and FP that presents new contributions to the existing CG and CS literature with insights from an emerging economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Does corporate governance characteristics influence firm performance in India? Empirical evidence using dynamic panel data analysis

Does One Size Fit All? A Study of the Simultaneous Relations Among Ownership, Corporate Governance Mechanisms, and the Financial Performance of Firms in China

The Effect of Governance Characteristics on Corporate Performance: An Empirical Bayesian Analysis for Vietnamese Publicly Listed Companies

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corporate governance (CG), capital structure (CS), and firm performance (FP) are three crucial aspects that are linked to each other. Previous studies on the association between CG and CS rely heavily on agency theory to explain a company's financing decisions (Boateng et al. 2017 ). Both are linked because agency cost is one of the major elements of CS and CG that mitigates agency conflicts. CS is a CG instrument that can assist a company in developing value by preserving CG efficacy (La Rocca 2007 ). Good CG is commonly acknowledged to improve company performance (Beiner et al. 2004 ; Black and Kim 2012 ; Padachi et al. 2017 ; Sheaba Rani and Adhena 2017 ; Mansour et al. 2022 ). However, FP can also influence the level of CG, often measured using the CG disclosure index (CGI) as a proxy for the overall quality of CG in different countries. For instance, profitable organisations are anticipated to have greater compliance and disclosure levels than unprofitable or less profitable organisations to attract new investors and shareholders (Suwaidan et al. 2021 ). Moreover, on one hand, CS can influence performance (Doan 2020 ; Amare 2021 ) but financial performance, on the other hand, may also have an impact on CS (Abdullah and Tursoy 2021 ). Organisations with better profitability can more easily obtain debt financing, probably at more competitive interest rates than companies with less profitability. Researchers have discovered that one of the most important elements influencing the CS mix is FP (Iyoha and Umoru 2017 ; Cevheroglu-Acar 2018 ).

In recent years, there has been a surge in attention paid to the impact of CG on CS and FP and CS on FP, respectively. However, a detailed analysis of the literature reveals significant shortcomings. First, the bidirectional causation between CG, CS and FP has rarely been considered. Second, most prior studies, although taking into account the dynamic nature of financial performance modelling, have largely ignored the issues of endogeneity and reverse causality in the CG, CS and FP nexus. Third, emerging nations such as Mauritius, and more specifically African countries, have distinct economic, institutional, legal, and political settings than developed countries; therefore, the relationships between CG, CS and FP and their reverse causalities may likely differ from those noted in developed economies. Previous studies in Mauritius on CG by Soobaroyen and Mahadeo ( 2008 ), McGee ( 2009 ), Mahadeo and Soobaroyen ( 2012 ) and Mahadeo and Soobaroyen ( 2016 ) focus on the level of compliance, whereas Appasamy et al. ( 2013 ) and Padachi et al. ( 2017 ) quantitatively study the impact of CG on FP using static models and with limited sample size. Prior studies related to CS in Mauritius have focused on the determinants of CS (Fowdar et al. 2009 ; Odit and Gobardhun 2011 ; Gourdeale and Polodoo 2016 ; Omrawoo et al. 2017 ), and so far, only one study has been conducted on the effect of CS on FP by Seetanah et al. ( 2014 ), with limited sample size and no CG variables employed as potential determinants. Fifth, no study has been conducted on the impact of CG on CS and vice versa in Mauritius, and most studies (Herlambang et al. 2018 ; Chow et al. 2018 ) have used several CG variables as proxies for CG. The use of CGI as a measure of overall CG quality to assess its impact on CS is rare. Finally, previous studies have largely focused on non-financial companies, while financial firms have often been ignored.

For various reasons, Mauritius is an attractive research setting for examining the interrelationships and interdependencies between CG, CS and FP. In Mauritius, the de facto features of the corporate environment are quite different from the CG structure, which is relatively less mature, from those used in developed countries, making Mauritius an interesting case for this study. Additionally, there are major differences between emerging and developed markets in terms of market and knowledge quality, volatility and size (Al-Malkawi 2008 ). Moreover, the Mauritian capital market has a concentrated ownership structure based on cross-shareholdings and pyramid ownership structures as well as an inactive market for corporate control, that is, takeovers. Managerial entrenchment often results from concentrated ownership structures (Elghuweel et al. 2017 ). Furthermore, Mauritius is a heavily indebted country with high-leverage enterprises, as debt from banks is favoured over equity and is a relatively inexperienced equity market. In an emerging economy with strong growth prospects, it is critical to investigate the impact of such a high-leverage structure on FP and vice versa. Mauritian enterprises are regarded as small corporations around the world because of their modest size. Finally, as an emerging economy, Mauritius is rapidly evolving and aspires to become a significant foreign direct investment hub by focusing on an innovatively led framework. Mauritius' continuous growth has brought with it several new difficulties and responsibilities, as well as a closer alignment with foreign investors and global stakeholders, all of which need a stronger focus on better CG and optimum CS which improve FP and help to attract investors. As a result, Mauritius emerges as a crucial motivator to conduct a first-hand study on the relationship dynamics between the CG, CS and FP of listed firms as part of realising the country's vision in competing with international competitors.

Consequently, this study aims to add to the existing body of literature by addressing some of the shortcomings of past studies and offering new empirical findings. First, this study offers evidence on the effects of CG, with a single measure of overall CG quality, on CS and vice versa in an emerging economy, Mauritius, where no such research has been conducted. Second, this study provides new evidence on the relationships between CG and FP, CS and FP, and CG and CS with reverse causalities in a small island emerging country like Mauritius, which has different characteristics compared to developed and larger developing/emerging economies. This will be the first attempt, to the authors’ knowledge, to examine the dynamic and interdependent relationships using a PVAR model between CG, CS and FP that presents new contributions to the existing CG and CS literature. Third, this study investigates the interrelationships and interdependencies between CG, CS and FP in a panel vector autoregression (PVAR) framework which accounts for potential dynamic and endogeneity issues and sheds light on reverse causality between these variables. Finally, this study examines any differences in the interrelationships and interdependencies of CG, CS and FP between financial and non-financial firms.

Therefore, this study aims to explore empirically, using a PVAR approach, the following interrelationships between CG, CS and FP, namely, to determine the direction of causation between CS and FP, CG and FP, and CG and CS in a sample consisting of SEMDEX (29) and DEMEX (13) listed firms from 2009 to 2019 in Stock Exchange of Mauritius (SEM), and the results are compared between financial (4) and non-financial firms (38). Dynamic evaluation is established on the completion of the forecast error variance decomposition (FEVD) and impulse response functions (IRFs). Different ordering of the variables and alternative methods of estimating the PVAR model, that is, XTVAR for robustness checks, are examined.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. The theoretical and empirical literature on the associations between CG, CS and FP is presented in “ Literature review ”. “ Research design ” describes the data, variables and methodologies of this study. “ Empirical results and discussion ” discusses the findings. “ Robustness analysis ” determines the robustness of the findings. The summary and conclusion of this study are presented in “ Summary and conclusion ”.

Literature review

CG entails mechanisms to ensure that lenders of capital to firms will receive a return on their investment (Shleifer and Vishny 1997). In a CG structure, a company’s timely decision-making policies and practices regulate the obligations and rights of its diverse stakeholders. Agency theory presents board members with professional expertise to meet these requirements. This board also decides on the best mix of debt and equity for a firm’s future performance. The pecking order theory (POT) and trade-of-theory (TOT) of CS provide managers with guidelines in this context. Based on these three prominent theories, this section illustrates the interrelationships between CG, CS and FP.

Theoretical literature

Agency theory.

Agency theory underpins the practice of CG. The primary tenet of this theory is that there is a working relationship in the form of a cooperation contract between the party providing the authority (the principal), that is the investor, and the party obtaining the authority (agency), namely the manager. Due to the separation of corporate ownership and control, agency conflicts develop. In an agency relationship, it is natural to anticipate that the agent (manager) will make decisions that are detrimental to the interests of the principal (owner) if economic agents are utility maximisers (Jensen and Meckling 1976 ). The amount of resources under the manager’s control is just one factor that influences how agency costs affect the composition of the CS. According to Jensen ( 1986 ), managers may take on debt to increase the resources under their control, which can result in debt agency costs like bankruptcy costs. CG stands out as a tool that facilitates the alignment of interests between agent and principal in this context. There are grounds to believe that CG and CS are related (Borges Júnior, 2022 ). This is based on the idea that agency conflict is influenced by CG mechanisms, and that these mechanisms are linked to choices concerning the composition of a firm's funding sources. Moreover, the agency theory proposes that CG and financial decisions have an impact on company value and CS must be viewed as a device that can intervene and drive governance structures within the business, and hence FP (Bashir et al. 2020 ).

According to agency theory, organisations voluntarily reveal additional information to reduce agency conflicts and the costs that arise from the conflict between managers and shareholders (Lambert 2001 ; Alves et al. 2012 ; Ntim and Soobaroyen 2013 ). As a result, increased mandatory and voluntary disclosures on CG may reduce information asymmetry between agents and owners, allowing shareholders to better supervise the management's conduct (Beekes et al. 2016 ).

Trade-off theory

The trade-off theory (TOT) accounts for the effects of taxes and the costs of bankruptcy. The theory assumes that firms trade-off the benefits of debt financing (favourable corporate tax structure) against increased interest rates and bankruptcy costs to find an optimal CS—the mixer that maximises a firm's worth. The TOT predicts a positive relationship, because when a company is profitable, it may take on more debt, resulting in larger interest payments that are deducted from taxes (Ponce et al. 2019 ).

Pecking order theory

Majluf and Myers ( 1984 ), in contrast to the TOT, developed the pecking order theory (POT), which implies that there is no optimal CS. Instead, the theory proposes that firms have a preferred funding hierarchy. According to Myers ( 1984 ), organisations with high levels of profitability have low levels of debt because they have a large number of internal sources of funding. Because POT predicts that corporations use their resources rather than borrow them, it expects a negative relationship. The validity of the POT has been proved in numerous empirical research (Acaravci 2015 ; Paredes Gómez et al. 2016 ).

Empirical literature

Capital structure and firm performance, causal effect of capital structure on firm performance.

It is expected that increasing financial leverage will strengthen management, lower information costs, and reduce inefficiencies, all of which will improve FP (Jensen 1986 ; Jensen and Meckling 1976 ). Financing decisions affect the cost of capital, allowing businesses to optimise their financial performance (Majluf and Myers 1984 ; Abdullah and Tursoy 2019 ). Empirical research demonstrates that FP can be influenced by the relative usage of both capital sources i.e., the mixture of debt and equity (Saona and San Martín 2018 ; Abdullah and Tursoy 2019 ). According to theoretical models, the link between CS and FP is unclear (Miglo 2016 ). Only a few empirical studies have explored the performance effect of leverage and the results vary. A few studies find that leverage is positively linked to FP, such as Vijayakumaran ( 2018 ) in China and Amare ( 2021 ) in Ethiopia, while others find it to be negatively linked, such as Li et al. ( 2018 ) in European SMEs from Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the UK; and Doorasamy ( 2021 ) in East Africa (Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda). In Mauritius, Seetanah et al. ( 2014 ) find a negative impact of CS on the FP of listed Mauritian firms for the period 2005–2011. Abata et al. ( 2017 ) report mixed results in another study conducted in South Africa.

Causal effect of firm performance on capital structure

CS may influence FP but the latter, on the other hand, may also have an impact on a company’s CS (Abdullah and Tursoy 2021 ). The logic of the reverse causal relationship between performance and leverage can also be explained using TOT and POT. Researchers have discovered that one of the most important variables influencing the CS mix is FP (Iyoha and Umoru 2017 ; Cevheroglu-Acar 2018 Koralun-Bereżnicka 2018 ). This argument may be explained by the TOT, which states that profitable businesses have lower bankruptcy costs and are, hence, more inclined to borrow (Fama and French 2002 ). Moreover, high-profit businesses are prone to take on more debt to reap tax benefits (Frank and Goyal 2009 ). Therefore, FP may favourably influence CS. Previous empirical research findings support the TOT’s claim (Ajibola et al. 2018 ; Angkasajaya and Mahadwartha 2020 ; Amare 2021 ). POT contends that profitable businesses are more likely to rely on the generated surplus to fund their assets rather than external sources (Myers 1984 ). Consequently, profitability is assumed to have a negative effect on leverage, keeping the investment level stable backed by empirical studies such as Jarallah et al. ( 2019 ) in Japan and Doan ( 2020 ) in Vietnam.

Reverse causality between capital structure and firm performance

Previous research has investigated the relationship between leverage and FP but fails to account for the reverse causality of CS on FP, and a simultaneous-equations bias may emerge (Iyoha, and Umoru 2017 ). From 2002 to 2012, Jouida ( 2018 ) studies the dynamic relationship between CS, diversification, and FP for 412 financial companies in France using a PVAR model and observes bidirectional causation between CS and FP after controlling for individual fixed factors. She and Guo ( 2018 ) examine a sample of 49 global e-commerce businesses from 2012 to 2016 and find a negative reverse causality between FP and CS that is in line with the POT, which nonetheless shifts when the quantity of debt grows. Abdullah and Tursoy ( 2021 ) examine the reverse causality between FP and CS of listed German non-financial firms from 1993 to 2016 and find that FP and CS can positively influence each other. Adhari and Viverita ( 2015 ) investigate the reverse causality between CS and FP of 215 firms in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore from 2008 to 2011 and observe that CS and FP can positively affect each other.

Corporate governance and firm performance

Causal effect of corporate governance on firm performance.

CG mechanisms may improve FP, amongst others, through better monitoring resulting in managers investing value maximising projects, lesser wastage of resources in unproductive activities and enhanced protection of investors implying a lower risk of losing their assets with acceptance of lower investment return triggering a lower cost of capital for firms. According to agency theory, there is a positive correlation between CG ratings and FP (Jensen and Meckling 1976 ). The implementation of appropriate CG mechanisms, as well as voluntary disclosure, will result in a net reduction in agency costs and an increase in FP (Fama and Jensen 1983 ; Siddiqui et al. 2013 ). CG disclosure is a critical tool for ensuring that firms’ CG practices are held within the bounds of law in terms of openness and accountability (Isukul and Chizea 2017 ).

A good CG is commonly acknowledged to improve FP (Padachi et al. 2017 ; Bhatt and Bhatt 2017 ; Sheaba Rani and Adhena 2017 ; Mansour et al. 2022 ). Other researchers, such as Rajput and Joshi ( 2014 ) in India and Adegboye et al. ( 2019 ) in Nigeria, find a negative connection between CG and FP, or no relationship by Hassouna et al. ( 2017 ) in Egypt, and Braendle ( 2019 ) in Austria, or find mixed results by Tariq et al. ( 2018 ) in Pakistan, Shao ( 2018 ) in China, Griffin et al. ( 2018 ) in various countries, and Dao and Nguyen ( 2020 ) in Vietnam. In Mauritius, Appasamy et al . ( 2013 ) show that there is a relationship between CG and FP in the insurance sector from 2009 to 2011, whereas Padachi et al. ( 2017 ) find a significant positive relationship between the CG and FP of 36 listed firms from 2010 to 2014.

Causal effect of firm performance on corporate governance

Profitable firms have more financial resources to sustain the increased administrative costs in meeting compliance and enhancing their CG level as compared to less profitable firms. Moreover, FP is regarded as an essential determinant of the level of CG through enhanced compliance with the code of CG and disclosure to stakeholders. Most disclosure research indicates a positive link between corporate profitability and CG disclosures (Elfeky 2017 ; Cunha and Rodrigues 2018 ). Agency theory contends that high-profit corporate executives reveal specific information to gain individual advantages, justify their salary packages, improve their reputation in the business market, and reinforce their position (Alnabsha et al. 2018 ). Moreover, profitable organisations are anticipated to have greater compliance/disclosure levels than unprofitable or less profitable organisations to attract new investors and shareholders (Suwaidan et al. 2021 ) . However, according to Ben-Amar and Boujenoui ( 2007 ), even those with weak financial performance have strong incentives to do so to attract investments and improve their financial ratios. Furthermore, increased information disclosure may be linked to lower profit levels, because corporations’ legal liability, if any, is lowered if they share unfavourable information or ‘bad news’ about themselves (Skinner 1994 ). This implies that a negative association may also exist between profitability and corporate disclosure (Zeghal and Moussa 2015 ; Suwaidan et al. 2021 ). Although previous research has examined the association between CG and FP, the bidirectional causation between these two variables is seldom considered which may result in simultaneous-equation bias.

Reverse causality between corporate governance and firm performance

Love ( 2011 ) observes that some prior studies argue that causality goes from governance to performance but others argue the opposite that causality runs in a reverse direction from performance to governance. There are various reasons to believe that causality can truly happen from valuation to governance. On one hand, organisations with superior operating results or greater market values may decide to adopt better governance methods, which will result in reverse causality. On the other hand, companies with poor performance prefer to adopt additional anti-takeover clauses, which are linked to poorer governance. As an alternative, businesses may embrace stronger governance processes as a predictor of future success or as a means of enforcing insiders' adherence to ethical behaviour. The signaling role of governance will be significant for share prices in this situation rather than governance itself. Reverse causation may also occur through institutional or international investors who are more inclined to companies with higher market values, which may also result in better governance practices.

Lamiri et al. ( 2008 ) examine the reverse causality between different board characteristics and FP of a panel of 36 listed Tunisian firms between 2004 and 2006 and their findings conclude that board influences FP and firms change their board structure in response to FP. Perez de Toledo ( 2011 ) assesses the relationship between the quality of CG proxied by a CGI and the market value of 106 listed Spanish firms from 2005 to 2007 and shows that CG positively impacts firm value but there is no proof of reverse causality, i.e. firm value influencing CG. Ingriyani and Chalid ( 2021 ) examine 51 listed Indonesian manufacturing firms between 2014 and 2018 and conclude that executive compensation, CG and FP are related to each other. They find that CG has a positive effect on FP and that greater FP tends to decrease the number of board of directors and the supervisory function of the commissioners but increase the proportion of independent directors.

Corporate governance and capital structure

Causal effect of corporate governance on capital structure.

Managers' choices of CS are among the most important business policy decisions they make (Boateng et al. 2017 ). This is because leverage decisions are subject to agency problems and have an impact on a firm's riskiness and performance (Jensen and Meckling 1976 ). Jensen and Meckling ( 1976 ) propose that the separation of principal and agent roles in businesses causes conflicts of interest (agency costs) between shareholders and management, leading to the idea of CG. This is where the two notions of CG and CS come together. According to agency theory, managers in low-CG practice organisations are more likely to experience agency problems, therefore, they will be tempted to use sub-optimal leverage to take advantage of free cash flow. Higher levels of leverage have been considered as a good substitute for weaker governance practices (Mwambuli 2019 ). In this situation, leverage and governance quality are inversely associated, with companies with low-CG practice needing to use more leverage to minimise agency costs and align firm managers' interests with those of shareholders.

Several studies have shown some evidence for the above assertion, indicating that CG frameworks have an important impact on listed companies’ leverage decisions (Morellec et al. 2012 ). For example, using a survey-based CG index Haque et al. ( 2011 ) investigate the link between CG and the leverage pattern of listed non-financial firms in Bangladesh. They discover that firm-level governance quality has a significant impact on a company's leverage, with weakly governed businesses having a greater degree of debt financing. Mwambuli ( 2019 ) investigates the role of CG, measured by a CGI, on CS of 32 non-financial listed firms in the East African region from 2006 to 2015 and finds a significant negative effect of CG on CS decisions. Most studies (Herlambang et al. 2018 ; Chow et al. 2018 ) use several CG variables as a proxy for CG, and the use of CGI as a measure of overall CG quality to assess their impact on CS is rare.

Causal effect of capital structure on corporate governance

CS can influence CG levels through enhanced compliance with the CG Code and more corporate disclosures. According to Jensen and Meckling ( 1976 ) and Masum et al. ( 2020 ), firms with high debt are prone to report additional information to satisfy the requests of external capital providers and alleviate borrowers’ concerns about the possibility of transferring resources from debt holders to managers and shareholders. Again, agency theory shows a robust correlation between a company’s CS and disclosure (Jensen and Meckling 1976 ), because the existence of debt holders in a company’s leverage (particularly in highly geared businesses) intensifies agency problems (and hence increases monitoring costs), which aims to decrease these costs by revealing additional information in their annual reports. These companies should increase their disclosure levels to restore investor and creditor confidence and as a result, minimise the impact of bankruptcy risk.

A substantial positive link between CS and CG disclosure has been observed by Al-Moataz and Hussainey ( 2013 ) in Saudi Arabia and Elfeky ( 2017 ) in Egypt, and an insignificant positive impact by Zeghal and Moussa ( 2015 ) in several countries, Elgattani and Hussainey ( 2020 ) in eight countries (Bahrain, Syria, Qatar, Sudan, Jordan, Palestine, Oman, and Mauritius), and Suwaidan et al. ( 2021 ) in Jordan. However, a significant negative relationship is found in some studies by Mallin and Ow-yong ( 2009 ) in the United Kingdom and Cunha and Rodrigues ( 2018 ) in Portugal, but such a relationship is found to be insignificant by Alves et al.( 2012 ) in Portugal and Spain, and Allegrini and Greco ( 2013 ) in Italy.

Reverse causality between corporate governance and capital structure

CS affects CG and vice versa. This is true regardless of whether management chooses to use debt as a source of funding to minimise issues with information asymmetry and transaction, increasing the efficiency of its firm governance decisions, or whether the growth in the debt level is required by the stockholders as a tool to discipline behaviour and ensure effective CG.

On one hand, a change in how debt and equity are managed affects CG practices by changing the structure of incentives and management control. If through the mixture of debt and equity, diverse types of investors all converge within the company, where they have different kinds of impact on governance decisions, then managers will typically have preferences when deciding how one of these categories will prevail when defining the company’s CS. More crucially, it is possible to significantly improve CG efficiency through the thoughtful design of debt contracts and equity.

On the other hand, CG also affects CS decisions. Myers ( 1984 ) and Majluf and Myers ( 1984 ) demonstrate how management makes decisions about a firm's financing following an order of preference; in this case, if the manager selects the financing resources, it can be assumed that the latter is avoiding a decrease in its ability to make decisions by agreeing to the discipline that debt represents. Finance from internal sources enables managers to keep outside parties out of their decision-making processes. Management can prevent outside influences from influencing their decision-making by financing internal resources. De Jong (2002) describes how managers in the Netherlands attempt to avoid utilising debt so that their ability to make decisions is unchecked, while Zwiebel (1996) observes that managers are forced to issue debt through other governance mechanisms since they are unable to freely embrace the “discipline” of debt (cited in La Rocca 2007 ). Jensen ( 1986 ) stated that decisions to increase corporate debt are voluntarily undertaken by management when it aims to ‘‘reassure’’ stakeholders that its governance decisions are ‘‘proper’’. Empirical studies on the bidirectional relationship between CG and CS are scarce.

Corporate governance, capital structure and firm performance

Previous research has investigated the relationships between CG, CS and FP but such research (Roy and Pal 2017 ; Nawaz K. and Nawaz A. 2019 ; Shahzad et al. 2022 ) has analysed each association separately, in one direction, and using various mechanisms of CG.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated the interrelationship and interdependence between these three variables simultaneously, and more so, using a single composite measure of CG level.

The impacts of CG mechanisms and leverage on FP from previous studies have mixed results, and it is interesting to investigate the simultaneous interrelationships and interdependencies between these three variables in a unique economic, political and social contexts of a small and emerging economy like Mauritius, considered as a reference for the main economic aspects (including good governance) in the African region.

Research design

This section discusses the current study’s research design and philosophy, disclosure sources, CGI measurement, data collection, sample selection, PVAR models and the statistical tests that are employed.

Research questions and conceptual framework

The study’s objectives are to analyse:

The interrelationships and interdependencies between CG, CS and FP of listed Mauritian firms, and

Any differences in the magnitude and impact of their interrelationships and interdependencies between Mauritian financial and non-financial listed firms.

Timeframe and statistical analysis model

A sample of firms listed on the SEM from 2009 to 2019 is examined. The PVAR approach is used to capture the multiple variables involved in the sample, according to the applicable literature discussed in “ Literature review ”. The STATA 16 software is used to analyse the data to obtain descriptive statistics and the PVAR model (Fig. 1 ).

Dynamic interrelationships and interdependencies between corporate governance, capital structure, and firm performance

Research and sampling design

This study applies the balanced panel data method to examine a sample of companies listed on the SEM from 2009 to 2019. The research data are collected manually, comprising four financial (excluding banks because of the difference in their CG disclosure requirements) and 38 non-financial companies listed on both SEMDEX and DEMEX of SEM. Annual reports before 2009 are unavailable for all 42 firms to have a balanced panel. The years 2020 and 2021 are excluded because of the worldwide economic crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic which will not reflect the true financial performance of the selected listed companies.

Description of the corporate governance disclosure index

The CGI is measured as the ratio of compliance with each of the CG practices of all 42 companies in the sample selected, which consist of six components/sub-indices of CG. The annual reports from 2009 to 2019 are used to determine whether each of the 102 governance provisions recommended in the checklist is true for that company, as per the Mauritian Code of CG. A ‘yes’ response in form of compliance to a respective governance practice is given a value of one and a ‘no’ response in form of non-compliance is given a value of zero. The CGI is calculated by adding these values to each company annually. Given that when the index has a large number of items and both weighted and unweighted indices’ scores produce similar results (Chow and Wong-Boren, 1987 ; Sharma, 2014 ), an unweighted index is used to evaluate disclosure levels as per previous studies (Cunha and Rodrigues 2018 ; Masum et al. 2020 ). Furthermore, the unweighted approach gives each disclosure item in the annual report equal weighting and is best suited to resolve the problem of subjectivity bias (Healy and Palepu 2001 ). Cronbach’s alpha test of reliability of the above six sub-indices forming the CGI has a score of 0.866, which shows that the sub-indices are reliable indicators for measuring the extent of CG.

Panel data vector autoregression (PVAR) models

A summary of the variables’ descriptions and measurements based on previous literature and utilised in this study is shown in Table 1 .

As per the definition in prior studies, three variables CGI, CS and ROE are used in this study. Bhagat et al. ( 2008 ) argue that developing a CGI is beneficial, because it incorporates the different components of a company's governance structure into a single number that can be utilised to assess governance efficiency. The interrelationships/interdependencies between CG, CS, and FP are investigated using the PVAR methodology. The PVAR method is particularly well suited to this research because it strives to model the evolution of a system of interest variables—CG, CS and FP—in a set of firms that differ significantly in various dimensions such as financial, non-financial, size, age, industry type, and listing status. The PVAR approach is a mixed econometric methodology that blends the standard VAR method, in which all variables in the model are considered endogenous, with the panel data technique, which permits the explicit insertion of a fixed effect in the structure (Shank and Vianna 2016 ). PVAR accounts for both static and dynamic interdependencies (Canova and Ciccarelli, 2013 ). This setup also enables us to investigate the Impulse Response Functions (IRFs) of various shocks and how they influence other imbalances. In this study, the model in the PVAR approach is limited to only endogeneous variables and control variables are excluded in line with prior studies (Shank and Vianna 2016 ; Comunale 2017 ; Jouida 2018 ; Traoré 2018 ; Apostolakis and Papadopoulos 2019 ; Trofimov 2021 ).

In a generalised method of moments (GMM) framework, the PVAR model selection, estimation, and inference are used, as proposed by Abrigo and Love ( 2016 ). Considering Abrigo and Love ( 2016 ), the following k -variable homogeneous panel VAR of order p , with panel-specific fixed effects characterised by the following system of linear equations:

where Y is a (1 × k) vector of dependent variables, X is a (1 × l ) vector of exogenous covariates, and ui and e are (1 × k) vectors of dependent variable-specific panel fixed-effects and idiosyncratic errors, respectively. The (k × k) matrices A 1, A 2, …, A p − 1, Ap, and the ( l × k ) matrix B are the parameters to be estimated. It is presumed that the innovations have the following attributes: E ( eit ) = 0 , E ( e’iteit ) = Σ , and E ( e’iteis ) = 0 , and for all t > s .

According to Abrigo and Love ( 2016 ), the PVAR describes in Eq. ( 1 ) has problems with dynamic interdependencies and cross-sectional heterogeneities. Consequently, the fixed-effects variable μi is the only variable that captures the heterogeneity between various units. Because the individual effect term Ai is linked to the error term in dynamic panels, the ordinary least-squares (OLS) method cannot be used, because estimation by OLS leads to biased coefficients (Jouida 2018 ). To address this issue, PVAR models are determined using an equation estimated with the GMM, in an 11 year study of 42 listed Mauritian companies. This method has numerous benefits. Arellano-Bond is used to generate unbiased fixed-effects average coefficients for the short panels (N > T). As a result, the findings control for all time-invariant characteristics that are often addressed in empirical research. On the left side of each equation is the first difference of an endogenous variable and on the right side is the p lagged first difference of all endogenous variables.

Panel unit root test

The Augmented Dickey and Fuller (ADF) (1981), Levin, Lin, and Chu (LLC) (2002) and Im, Pesaran, and Shin (IPS) (2003) tests for data stationarity reveal that all the series of variables used in this model are stationary at level, because the p-values are below the 5% level. Given the absence of a unit root, it is possible to investigate the causation between the three variables.

Selection order criteria

For the study of the PVAR models, the steps of Abrigo and Love ( 2016 ), who present a package of controls on STATA, are followed. The optimal lag order in the panel VAR specification and moment condition is used to perform the PVAR analysis. Since the first-order panel VAR (one lag) has the smallest MBIC (Bayesian information criteria, Schwarz, 1978), MAIC (Akaike information criteria, Akaike, 1969), and MQIC (Hannan-Quinn information criteria, Hannan and Quinn, 1979), the data in Table 2 support this option.

Empirical results and discussion

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3 shows the normal statistical characteristics of the main and other variables, including the mean, minimum, maximum, and standard deviation, of the sample of 42 listed companies.

As shown in Table 3 , the average return on equity ratio (ROE), a proxy for FP, is 22.2%. The CGI , as a proxy for CG, for all 42 listed firms ranged from 21.6 to 97.1%, with a mean of 81.9% and a standard deviation of 11.9%. The mean value of the CGI of the 38 non-financial firms is 81%, while that of the four financial firms is 90.6%. The results indicate that listed Mauritian firms are highly compliant with the Mauritian CG Code, with financial firms being more compliant than non-financial firms. The average CS levels of Mauritian companies are almost 101.6% of their equity (financial firms: 131.2% and non-financial firms: 98.5%) demonstrating that they are highly leveraged firms. ROE is on average 22.2% for the whole sample and 7.1% and 165.4% for non-financial and financial firms, respectively.

Correlation analysis

The correlation analysis between the three variables in Table 4 and the variance inflation factors (VIF) for both CS and CGI is 1.00 which implies that there is no evidence of multicollinearity.

PVAR results and discussion

Pvar results.

Table 5 shows the coefficients from the PVAR model by using ‘GMM-style’ instruments for CG, CS and FP. In this model, all variables are at a level and considered endogenous. Table 5 indicates that, in the CG equation, CG responds positively and significantly to its own lag for all firms, including both non-financial and financial firms. The CG responds positively and significantly to the lag of CS only for financial firms. CS has a positive impact on CG because high levels of leverage of financial firms raise agency costs, which encourages managers to reveal more information in an attempt to lower these costs. Moreover, financial companies with high debt ratios are exposed to significant monitoring costs or specific restrictive covenants, which force them to reveal more information and also reassure their lenders to extend or lengthen the debt contract time. It can also be noted that CG responds negatively and substantially to the lag in FP, except for non-financial firms, where it is positive but insignificant. The negative impact of FP on CG is consistent with the findings of Zeghal and Moussa ( 2015 ) and Suwaidan et al. ( 2021 ), because even Mauritian firms with weak financial performance have strong motivations for CG disclosures to attract investment and enhance their financial ratios. The positive effect of FP on CG disclosure for non-financial firms, supporting the agency theory, is because they may be aiming to attract new investors and shareholders.

In the CS equation, all coefficients are significant, as indicated by their values at the 1% level. CS responds positively and significantly for the whole sample and non-financial firms to the lag of CG but negatively and significantly for financial firms. The positive effect of CG on CS implies better governed non-financial firms are in a better position to obtain more debt. As regards financial firms, CG impacts negatively on CS because firms with low-CG practice need to use more leverage to minimise agency costs and align firm managers' interests with those of shareholders. The CS responds positively and substantially to its own lag in all three cases. The lag in FP has a substantial positive effect on CS for the whole sample and two sub-samples. This implies that profitable Mauritian firms are more inclined to borrow more because of low bankruptcy costs and reap more tax benefits and support TOT.

Regarding the FP equation, FP responds significantly and positively to its own lag and the lag of CS for the whole sample and two sub-samples. CS has a positive impact on FP, because an increase in firm leverage is expected to decrease information costs, lessen inefficiency, strengthen management and thus enhance FP. Nevertheless, the response of FP to CG differs; it is negatively connected to the lag of CG for the whole sample and non-financial firms which contradicts the findings of Padachi et al.( 2017 ). This significant negative relationship for non-financial firms can be the result of the prevalence of highly concentrated ownership among the listed Mauritian companies which often leads to managerial entrenchment (Elghuweel et al. 2017 ) that can have adverse impacts on management behaviour and incentives. Another possible reason for the negative impact of CG on FP can be that directors of the board and its board committees may not be having a total commitment to the cause of the company because of other commitments which limit their contribution. For financial firms, FP responds positively but insignificantly to CG lag.

There is no indication of any reverse causation between CG and FP for all firms, including non-financial and financial firms. Causality runs negatively and significantly in just one direction for the whole sample and financial firms—from FP to CG and not vice versa. For non-financial companies, however, causality only flows negatively and significantly in one direction, from CG to FP which is in line with the studies by Rajput and Joshi ( 2014 ) and Adegboye et al. ( 2019 ) and not vice versa. Additionally, CS has a positive and significant impact on FP and vice versa, demonstrating a strong bidirectional relationship between CS and FP for all firms, including non-financial and financial firms, and supporting the agency cost hypothesis and CS trade-off theory, which contradicts the findings of Jouida ( 2018 ) with varying relationships but consistent with the findings of Abdullah and Tursoy ( 2021 ) and Adhari and Viverita ( 2015 ). Moreover, the analysis reveals a unidirectional relationship between CG and CS for the whole sample and non-financial firms, because CG has a positive significant influence on CS, implying that better governed firms have more debt, but not vice versa. For financial firms, however, substantial bidirectional correlations between CG and CS have been established with varied signs. For instance, CG has a major negative effect on CS, meaning that better governed financial firms have less leverage (Haque et al. 2011 ; Mwambuli 2019 ), and CS has a considerable positive impact on CG in line with the findings of Al-Moataz and Hussainey ( 2013 ) and Elfeky ( 2017 ) and which supports the agency theory.

Overall, the findings reveal that better governed firms can increase their leverage to boost FP which in turn helps to obtain further debt. Therefore, in an emerging economy with steady economic growth and growth opportunities, profitable and better governed firms are prone to finance their investments with additional debt that significantly improves their profitability. However, as a firm increases its debt holdings, the probability of financial distress increases and creditors are less likely to re-finance or renegotiate. In this context, given the importance of debts and good CG, policymakers can consider measures relating to monetary (interest rates) and fiscal (tax) policies to make loans from financial institutions more accessible and attractive/competitive and to further improve CG standards that jointly help to improve FP. However, policymakers can also consider policy measures for steady positive economic growth because any decline may increase bankruptcy risks with serious repercussions due to the presence of highly leveraged companies.

- Granger causality

In Table 6 , the null hypothesis that all lags of all variables can be excluded from each equation in the PVAR system is evaluated in the final row, which displays the joint probability of all lagged variables in the equation.

Table 6 shows that the joint significance Chi-square statistics in the last row show that all three variables i.e., CS, CG and FP variables are granger-caused by all the lagged variables for financial firms only. CS and FP variables are jointly and significantly granger-caused by all the lagged variables for all firms including non-financial and financial firms. However, the CG variable is not jointly and significantly granger-caused by all the lagged variables for the whole sample and non-financial firms. In general, the findings reveal that CG and FP jointly help to increase leverage, and CG and CS jointly boost the profitability of firms. Policy measures can, therefore, be focused on jointly improving CG standards and leverage to boost FP (Fig. 2 ).