Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles

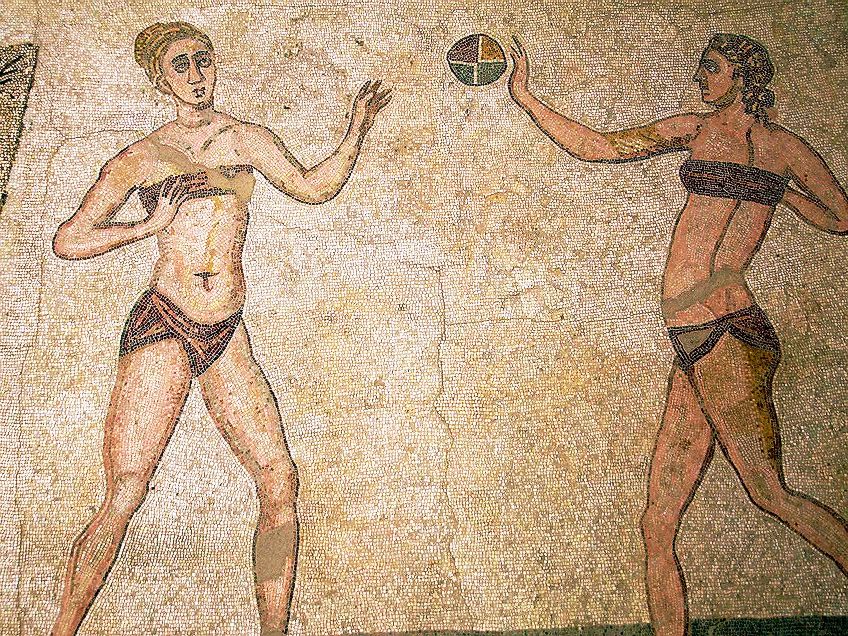

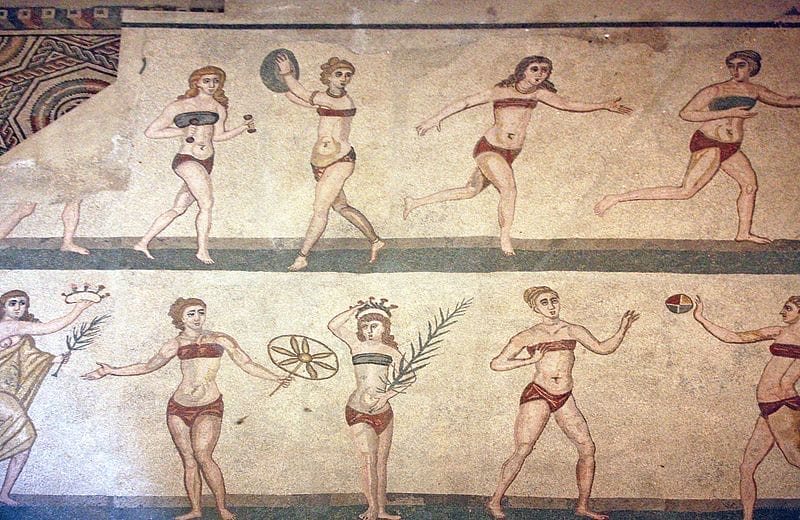

From Antioch to Africa, ancient Roman mosaic art was a ubiquitous component of private residences and public structures. Roman Mosaic tile art is not only stunning in and of itself, but it also serves as essential documentation of everyday objects such as clothing, foodstuff, tools, weaponry, vegetation, and animals. Roman mosaic floor artworks also disclose a lot about Roman pastimes like gladiator fights, athletics, farming, and hunting, and they occasionally even depict the Roman people themselves in vivid and lifelike portraits.

Table of Contents

- 1.1 Influences and Origins

- 1.2 Design Evolution of Roman Patterns and Motifs

- 1.3 Other Roman Mosaic Floor Designs

- 1.4 Mosaic’s Other Uses

- 2.1 Plato’s Academy Mosaic

- 2.2 The Cave Canem Mosaic

- 3.1 What Is the Origin of Roman Mosaic Floors?

- 3.2 How Are Roman Mosaic Tiles Made?

Ancient Roman Mosaic Art

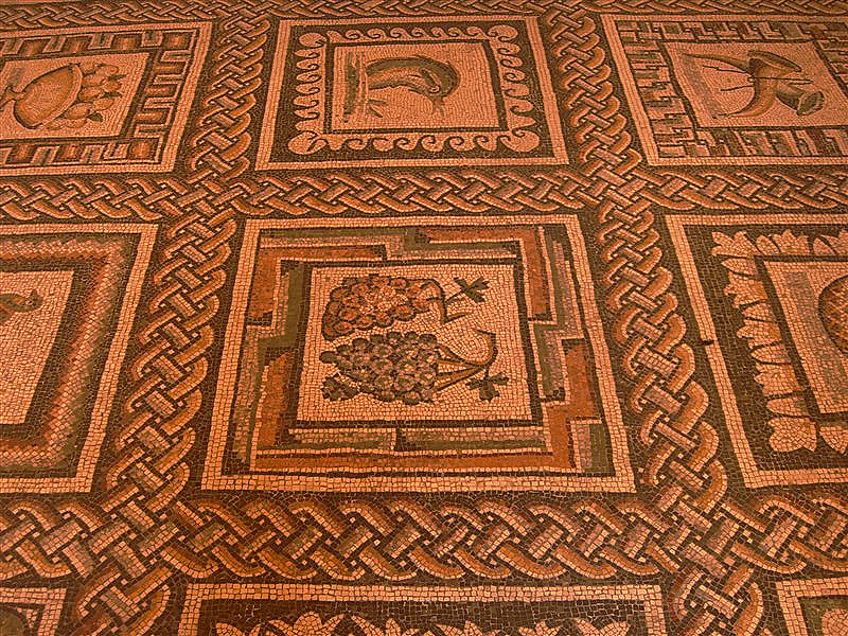

The Roman patterns made of small white and black tiles are known as Roman Mosaic art. Glass, ceramics, stones, and even seashells were used to create these square tiles, with a fresh mortar base being initially constructed.

After, the tiles or tesserae were placed as close together as feasible, with any gaps plugged with liquid mortar in a procedure called grouting. The entire thing was then washed and polished.

Influences and Origins

During the Bronze Age, both the Minoans and the Mycenaeans employed flooring made of tiny pebbles. A similar concept, but with repeating motifs, was utilized in the Near East in the eighth century BCE. The first attempts at pebble paving in Greece date back to the 5th century BCE, including specimens at Olynthus and Corinth. They were often two-toned, with light geometric motifs and basic figures on a black background.

Colors were being utilized by the close of the 4th century BCE, and numerous good instances have been discovered in Pella in Macedonia.

These mosaics were frequently strengthened by inlaying pieces of clay or lead, which were frequently employed to delineate contours. However, it wasn’t until the Hellenistic period in the 3rd century BCE that mosaics truly took off as a form of art, with elaborate panels made of tesserae instead of pebbles being mixed into patterned flooring. Many of these mosaics tried to imitate wall murals.

As mosaics advanced in the second century BCE, finer and more accurately cut tesserae were used, and patterns utilized a broad range of colors with colored grouting to complement adjacent tesserae.

This form of mosaic, which employed intricate coloration and shading to produce a painting-like impression, is known as opus vermiculatum , and one of its best artisans was Sorus of Pergamon, whose work, particularly his Drinking Doves mosaic, was widely replicated for years following.

Aside from Pergamon, notable specimens of Hellenistic opus vermiculatum have been discovered in Delos and Alexandria. Because of the time and effort required to create these pieces, they were placed on a marble tray or bordered tray in a specialized workshop. These items were called emblemata because they were frequently utilized as centerpieces for pavements with simpler motifs. These pieces of art were so precious that they were frequently relocated for re-use somewhere else and passed down through generations within families.

A single mosaic might be made up of several emblemata, and as time passed, the emblemata developed to imitate their environment, and they were known as panels.

Design Evolution of Roman Patterns and Motifs

With a topic like mosaics, it’s impossible to depict a precisely linear growth of the art form since there’s so much variation in artistic excellence, public preference, and regional norms. However, certain significant differences and geographical differences can be identified.

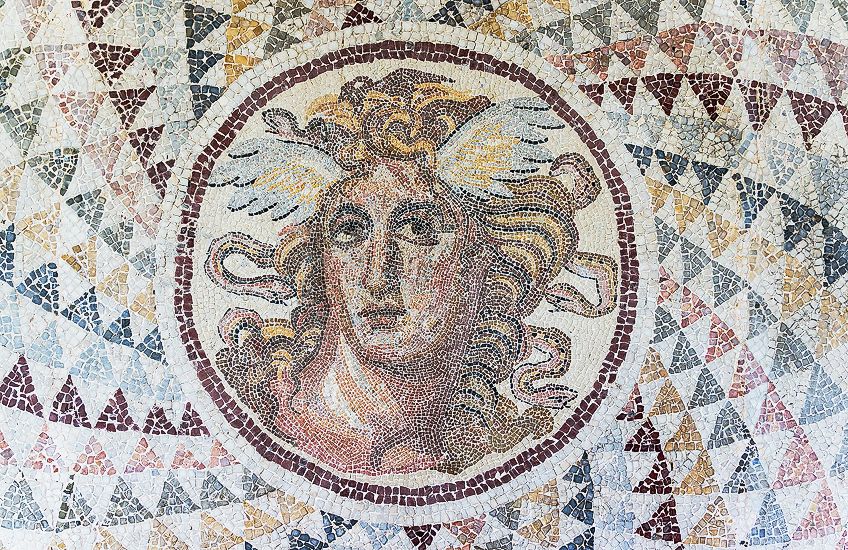

At first, the Romans did not deviate from the Hellenistic attitude to mosaics, and they were strongly swayed in regards to the subject matter – sea themes and depictions from Greek mythology – and the creators themselves, as many signed ancient Roman mosaic art contain Greek names. This demonstrated that even in the Roman period, Greeks controlled mosaic design.

One of the most well-known Roman mosaic tile artworks, The Alexander Mosaic , for example, was a replica of a Hellenistic classic artwork by either Aristeides of Thebes or Philoxenus. It is part of the Pompeii mosaics, located at the House of the Faun.

Although Roman mosaics frequently copied earlier colored ones, the Romans eventually developed their own designs, and manufacturing schools were established throughout the empire to nurture their own specific tastes.

These included large-scale hunting sequences and efforts at perspective in the African regions, painterly vegetation, and a foreground viewer in Antioch mosaics, or the European personal taste for figure panels, for instance.

The main Roman style in Italy itself employed solely white and black tesserae, a taste that lasted far into the third century CE and was most frequently used to portray aquatic motifs, particularly when used for Roman baths ( for instance those that are located on the first floor of the Baths of Caracalla.) There was also a penchant for two-dimensional depictions, with a focus on geometric patterns.

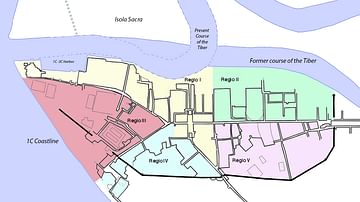

The oldest depiction of a humanoid figure in mosaic artwork is found at the Baths of Buticosus in Ostia around 115 CE, and silhouetted figures were popular in the 2nd century CE.

Over time, the mosaics’ depictions of human beings got more lifelike, and precise portraits became more widespread. Meanwhile, in the eastern half of the empire, particularly Antioch, the 4th century CE saw the emergence of mosaics that employed two-dimensional and repeating patterns to produce a “carpet” impression.

This style would go on to profoundly influence subsequent Jewish synagogues and Christian churches.

Other Roman Mosaic Floor Designs

Floors might also be placed with bigger pieces to create greater-scale patterns. Opus signinum flooring was made of colored mortar-aggregate (typically red) and white tesserae that were set in wide patterns or even randomly.

Crosses with five red tesserae and a center tessera in black were a popular pattern in Italy in the first century BCE and remained until the first century CE, but with only black tiles.

Opus sectile was a form of flooring that employed huge colored marble or stone slabs carved into certain shapes. Opus sectile was another Hellenistic method, although the Romans also used it for wall design. Although it was used in many public structures, it wasn’t until the 4th century CE that it became increasingly widespread in private villas.

Following Egyptian influences , opus sectile started to employ opaque glass as the major material.

Mosaic’s Other Uses

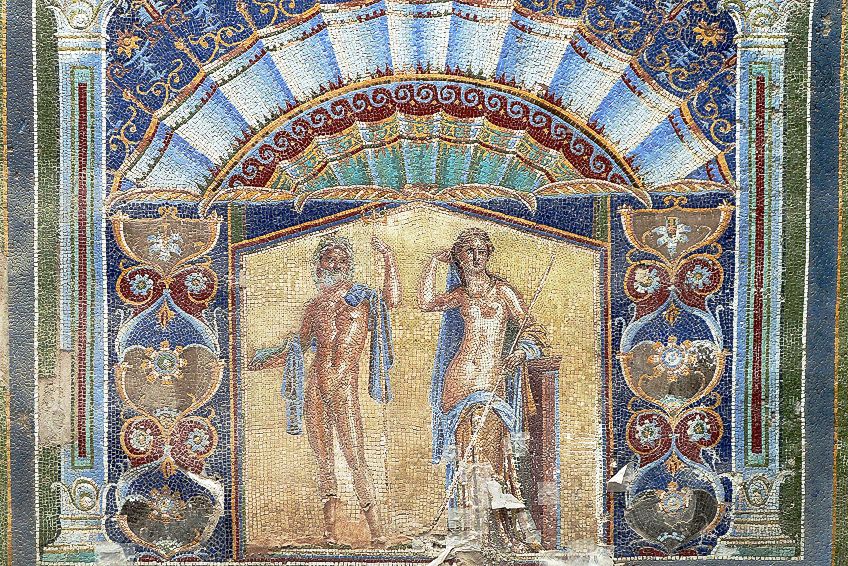

Mosaics were not just used on floors. columns, vaults, and fountains were frequently adorned with mosaics, particularly in baths. The first example of its use may be found in the nymphaeum of the “Villa of Cicero” at Formiae in the mid-1st century BCE, when pumice, marble, and shell fragments were utilized. In other places, bits of glass and marble were placed to create the illusion of a natural grotto.

More intricate mosaic panels were also utilized to adorn Nymphaea and fountains by the 1st century CE. The method was also utilized with the Pompeii mosaics to cover walls and pediments, and these murals often mimicked real paintings.

Later Imperial Roman baths’ walls and vaults were also adorned in mosaic utilizing glass, which worked as a reflector of the sunlight striking the pools and provided a shimmering appearance. The flooring of pools was frequently decorated with mosaic, as were the floors of mausolea, which occasionally included an image of the dead.

The Roman utilization of mosaics to embellish wall space and vaults influenced internal decorators of Christian churches beginning in the fourth century CE.

The Pompeii Mosaics

For more than 2000 years, historians, archeologists, and visitors have been enthralled by Pompeii and its devastation. Pliny the Younger’s manuscripts, which were lost beneath debris until unearthed in 1748, included information on a major volcanic eruption that rocked the Bay of Naples. The conventional date of the Mount Vesuvius eruption in 79 CE, although the current study has been conducted to revise this date, even down to the specific day.

The volcano erupted, burying the Bay of Naples, particularly Pompeii, in a thick layer of ash and detritus, functioning as a protective blanket over the people, structures, and materials of the site.

Because of the chemical composition of the volcanic ash and its unique qualities, archeologists have discovered nothing less than a perfectly intact Roman metropolis during the height of the Roman Empire over the last 250 years.

While much has been written on the incredible preservation and castings of remains, the Pompeii mosaics are equally as beautiful and merit their own in-depth examination.

Plato’s Academy Mosaic

Plato’s Academy mosaic is a near-perfectly maintained mosaic. This mosaic, which dates from the first century BCE or just before the eruption, is housed in the home of T. Siminius Stephanus. A group of seven people is depicted in the tile.

It is supposed that Plato is at the head, yet correctly identifying one of the characters as Plato is very difficult, as no differentiating feature of rank is indicated.

The artist might have been seeking to magnify the wisdom and insight that philosophy provides by combining the philosophy-centered emphasis with the theatrical masks on the border.

The Cave Canem Mosaic

The Cave Canem mosaic, or “Beware of the Dog,” is perhaps one of the most fascinating mosaics to a new audience. The well-preserved mosaic was installed at the entryway of the Tragic Poet’s House. An extremely lifelike dog, displayed in active motion as if about to attack, baring teeth and wearing a leash and chain around its neck, is overlaid over a background of repeated diamonds and carries the words “CAVE CANEM” in Latin.

This is the first thing guests would have seen when they entered the house, and it is similar to any current sign put on a fence or door declaring the same thing. A stunning cast of a dog trapped in the disaster may be found among the ruins of Pompeii. While this dog was not the one represented in the mosaic, it did wear a collar and was most likely a pet.

While these three mosaics are not the only ones that survived at Pompeii, they are among the more intriguing and engaging. Mosaic installations were extremely frequent kinds of decorating, although we seldom find this level of near-perfect preservation.

Looking at these mosaics reveals the aesthetic interests of the residents at the time, as well as the topics that were essential in their everyday lives. Ongoing excavations at the Pompeii mosaics continue to find architectural components such as terraces and allies, as well as corpses, frescoes, texts, and mosaics, revealing even more significant insight into everyday life in the Roman Empire.

Ancient Roman mosaic art was a common feature of private homes and public constructions from Antioch to Africa. Not only is Roman mosaic tile art beautiful in and of itself, but it also provides an important record of everyday goods like clothes, food, tools, armament, greenery, and animals. Roman mosaic floor artworks also reveal a great deal about Roman activities like gladiator battles, sports, farming, and hunting, and they occasionally portray the Roman people themselves in vivid and lifelike images.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the origin of roman mosaic floors.

During the Bronze Age, both the Minoans and the Mycenaeans used pebble floors. In the seventh century BCE, the Near East used a similar design, but with repeated themes. The first attempts at pebble pavement in Greece date back to the 5th century BCE, with examples found at Olynthus and Corinth. They were frequently two-toned, with light geometric designs and simple forms set against a black backdrop. These mosaics were usually reinforced by inlaying clay or lead bits, which were commonly used to outline shapes.

How Are Roman Mosaic Tiles Made?

Roman mosaic art refers to Roman designs consisting of tiny white and black tiles. These square tiles were made from glass, pottery, stones, and even seashells. A new mortar base was first constructed, and then the tiles or tesserae were placed as close as possible together, with any spaces plugged with liquid mortar in a practice called grouting. After that, the entire item was cleaned and polished.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20 th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles.” Art in Context. March 7, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/roman-mosaic/

Meyer, I. (2022, 7 March). Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/roman-mosaic/

Meyer, Isabella. “Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles.” Art in Context , March 7, 2022. https://artincontext.org/roman-mosaic/ .

Similar Posts

Proto-Renaissance – A Highlight of Western Culture and Art

Ukiyo-e – A Glimpse into Japan’s Pictorial History

What Is Chiaroscuro? – A Look at the Chiaroscuro Technique in Art

American Regionalism – The Drive for Accessible American Art

Dark Art – Art That Expresses Everything Dark and Grisly

Art in Florence – Explore the Artistic Wonders of This Great City

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

Greek Mosaics in Later Greek Art and Modern Art Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

History of Mosaics in Later Greek Art

Greek mosaics and modern art, how this influence has shaped the world of design.

Bibliography

Greek mosaic is known to have been an old practice. The practice of making floors through the placement of pebbles and cement plaster was common in early Greece. A unique principal characterized this form of art in Greece. For instance, all the decorated floors were usually confined to a unique principle whereby the dining room (the andron ) and the anteroom were considered. A good example is the Pella Palace characterized by hypothetical floors.

Archeologists have indicated conclusively that pebbles were widely used by early Greeks to decorate floors during the Bronze Age. Incidentally, such flooring materials were embraced by other non-Greeks. For example, the use of pebbles as a unique flooring material was embraced in Anatolia from the eighth century BC.

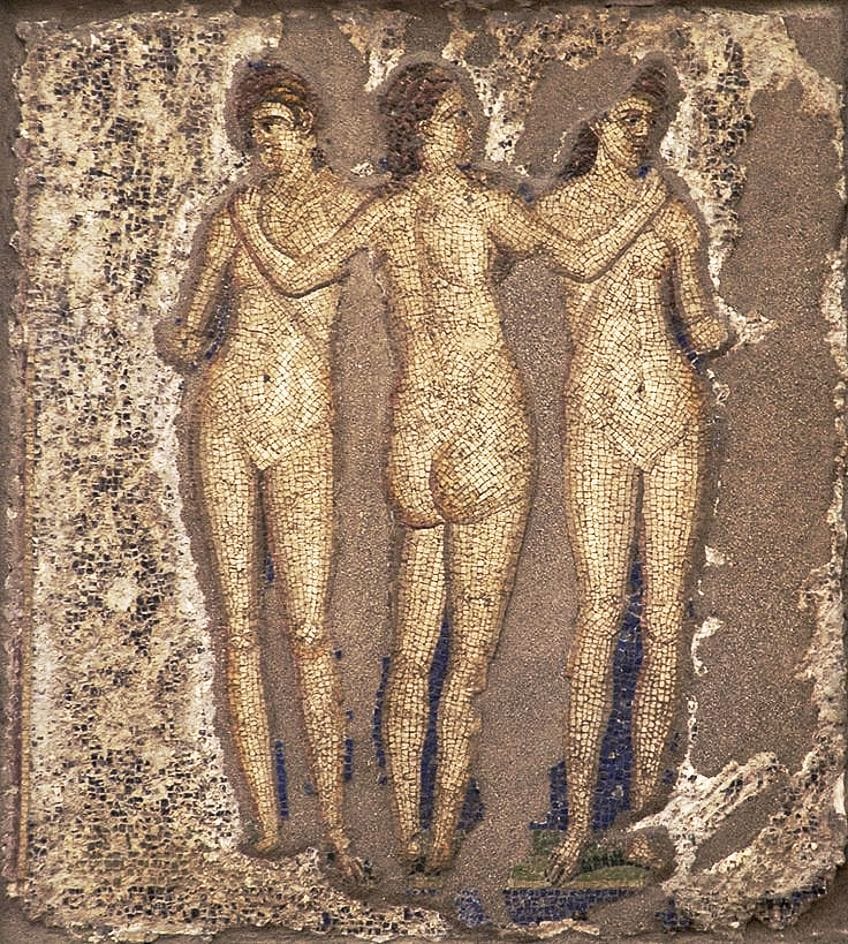

Greek mosaic is a practice that began towards the end of the 5 th century BC. Several centuries later, the design of the Greek mosaics changed drastically to include concentric bands, geometric patterns, and figured decorations. Such decorations focused on a specific figured scene or motif. From the third century BC, the nature of these mosaics changed significantly with the use of pebbles dominating the practice. Analysts have argued strongly that the Greek mosaics were specifically aimed at achieving specific given goals such as honor and aesthetics.

Some scholars have argued that Greek mosaics were similar to fresco painting. This must have been the case because layers of course plasters were covered by a finer one. The pebbles were then set into this finer plaster. During the process, a complex figure could be drawn on the course plaster. This approach has been given the name of the light-on-dark principle. One unique attribute of these mosaics is that the artists never sorted the pebbles into different sizes. However, the stones were packed closely to hide the plaster. Smaller pebbles were used to achieve detailed modeling.

The Greeks went further to embrace a new concept known as red-figure. This concept was achieved through the harmony of the lines and by balancing the light figures on the dark background. This achievement is depicted by the Dionysus on a Panther from Building 2.

Analysts have observed that similar floors were common in North Greece. However, most of the artworks associated with the region emphasized the three-dimensionality. This approach improved the nature of the Greek mosaic thus encouraging more artists to pursue the practice for many years. According to Martin Robertson, pebble floors continued to include figure scenes in order to remain meaningful and spectacular. Heroes and natural sceneries were emphasized by Greek artists. The practice continued to take center-stage in Greece for many years. Historians believe that pebble mosaics had been used widely in public spaces and buildings. The practice was later embraced by private house-owners in an attempt to imitate such prestigious decorations.

Historians have shown conclusively that pebble mosaics were common in Olythos by the fourth century. The andron is where such pebble mosaics were largely concentrated. During the time, the andron was the only room characterized by a wall plaster. The pavements and walls were designed in an attempt to create something called a crescendo.

Private ostentation was achieved towards the end of the 5 th century. The use of mosaics in more houses is something that increased throughout the Hellenistic period. After the conquest of Greece by Alexander the Great, private luxury continued to grow. This was the case because more people became wealthier after Alexander’s conquests. After the Persian Empire was defeated, precious stones and metals from the royal treasures were available to more people.

Experts have gone further to argue that the great houses at Pella were built using the spoils from the famous Alexander’s campaigns. The Greeks were ready to spend this wealth on such decorations and lead lavish lifestyles.

Houses containing more than one dining room were seen to have such decorations. According to past studies, such strategies must have been embraced by the people to impress their visitors. Such rooms could have been used to host more friends and guests. The approach was critical towards expressing power and social differences. The size of decorated dining rooms was a clear distinction between the rich and the poor. A good example is the Vergina Palace that had numerous dining rooms.

From the early fourth century, artists began to use new materials such as glass and terracotta for different mosaics. Tessellated mosaics became common than ever before. The wealth associated with the Hellenistic period encouraged more people to spend money on such conspicuous consumptions. An individualistic ethos replaced the existing classical polis of the time. The social, economic, and political changes experienced during the time led to the proliferation of mosaics in Greece. During the same time, the government was left in the hands of politicians. Mercenaries were hired to protect more citizens.

The concept of individualism after Alexander’s death emerged due to the increasing tension and insecurity. The desire to invest in mosaics was seen as a source of comfort in a country that was faced by uncertainties.

Experts define mosaic as the art whereby beautiful patterns or pictures are creating by setting small materials on a plastered surface. More often than, the practice is decorative in nature and can be achieved through the use of stone pebbles and marbles. This practice is believed to have been developed by the ancient Greeks. During the time, mosaics were employed as useful techniques for interior decorations.

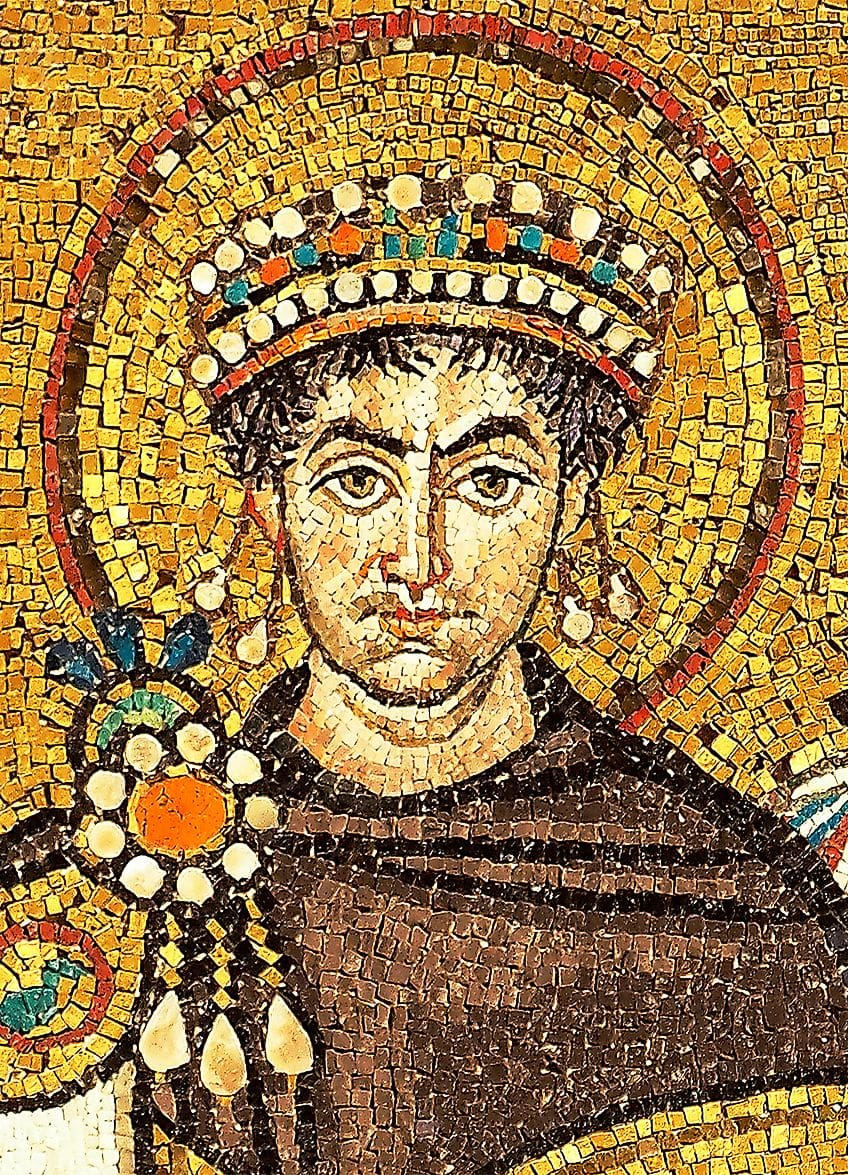

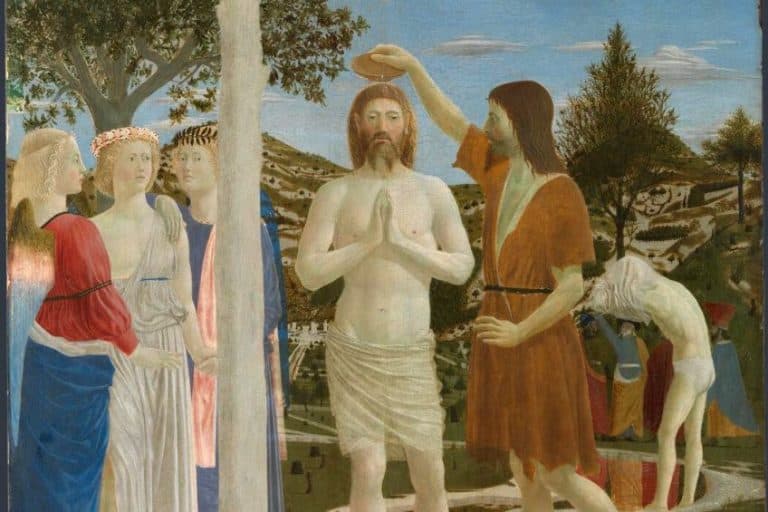

However, the technique would be copied by other societies such as the Romans. After the Renaissance Period, mosaics became common since many Christian painters used the technique to come up with powerful masterpieces. A good example was the mosaic of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great . Although fresco painting might have become the main form of art during the Renaissance Period, historians have observed that mosaic art continued to enjoy a healthy come-back throughout the 19 th and 20 th centuries.

The most outstanding fact is that the mosaics of the ancient Greeks have significantly influenced modern-day art. A revival of the technique occurred towards the end of the 19 th century. During this time, many public houses and buildings were decorated using marbles and mosaics thus giving the art practice a new meaning. A good example is the Westminster Catholic Cathedral (Fig 4) that is decorated using ceramic tiles.

Archeologists and historians have argued that several design styles have played a significant role in influencing modern mosaic art. For instance, the Gothic Revival is believed to have presented new art designs that continue to dominate the world of art even today.

It is undeniable that the mosaic continues to remain one of the popular crafts in different corners of the world. This has been the case because there are a number of organizations that promote this style of art. Some of these organizations include the Society of American Mosaic Artists (SAMA) and the British Association for Modern Mosaic (BAMM). These organizations have managed to come up with three unique types of mosaics. The first one is known as the direct method. This mosaic-building technique is completed when the artist affixes the materials onto the targeted surface. The artist might sketch the lines before decorating the object.

The indirect method, on the other hand, focuses on the use of sticky backings. The next stage is to affix the tiles or pebbles. This technique has been widely embraced because it makes it easier for artists to redesign and rework their masterpieces. The third method is known as the indirect mosaic creation. The pebbles or glass tiles are usually placed face-up unlike in the direct method. The influence of modern mosaics can be seen in great masterpieces such as the Bayeux Tapestry . This is a famous half-size mosaic depicting how the practice is presently embraced in many parts of the world. This masterpiece was created by Michael Linton from 1979 to 1999. The artwork is presently displayed in Geraldine, New Zealand.

Throughout the years, the mosaic is a powerful art that has shaped the world of design. Many aspects of human life are influenced or governed by the world of design. This ranges from different approaches to engineering, programming, art, and building.

The decorative world has benefited significantly from the mosaic. For instance, many designers and artists borrow a lot from Greek mosaics in order to produce masterpieces that can deliver the most desirable goals. Architects have continued to embrace the art style to design houses and buildings that are aesthetic in nature. Interior designers have not been left behind. With the Greek mosaic transforming the emotions and feelings of many people, modern painters have copied the idea in order to achieve similar results in the modern-day world.

Programmers and computer engineers have gone further to embrace the idea. Such programmers are able to design powerful software programs capable of producing superior artworks. Many firms have copied a lot from the style to produce a wide range of products such as clothes and consumer products. Manufacturing companies are also using robots to produce artistic products. The use of computer-aided designs is also making it easier for painters and artists to produce superior mosaics that capture the attention of many people.

Many buildings, landscapes, public spaces, walls, drawings, and living areas have benefited significantly from the concept of mosaic. The idea has been replicated by many people thus making mosaic a powerful artistic style that has been admired by many generations. That being the case, the mosaic remains a powerful style of art that continues to influence many professionals across the world. This means that the lessons learned from the ancient Greeks will continue to reshape the world of design for the next years.

Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great. Wall plaster. 3m x 2m. Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna.

Dionysus on a Panther . Pebbles on plaster. 130cm x 130 cm. Archaeological Museum of Pella, Athens.

Dunbabin, Katherine. Mosaics of the Greek and Roman world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Linton, Michael. Bayeux Tapestry. Cloth. 70000cm x 50 cm. Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux, Normandy.

Ludington, Townsend. A modern mosaic. New York: UNC Press, 2000.

Marconi, Clemente. The Oxford handbook of Greek and Roman art and architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Nassar, Mohammed. “The art of decorative mosaics (hunting scenes) from Madaba area during Byzantine Period (5 th – 6 th AD).” Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 13, no. 1 (2013): 67-76.

Robertson, Martin. “Early Greek mosaic.” Studies in the History of Art 10, no. 1 (1982): 240-249.

Westgate, Ruth. “Greek mosaics in their architectural and social context.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 42, no. 1 (1998): 93-115.

Vergina Palace . Pebbles on plaster. 140m x 80m. The Royal Tombs and the Ancient City, Athens.

- Enlightenment Art and Humanistic Thinking

- Pre-Renaissance Mythology, Sculptures, Paintings

- Analysing Customers Through Mosaic

- Organizations Helping Women of Color Lead

- Byzantine Art: The Concept of the Emperor

- Pregnant Female Body in Renaissance and Modern Art

- Greek Mosaics, Sculpture, and Roman Taste

- Baroque Art Paintings and Sculpture

- Modernity Development in Art of 18-20th Centuries

- Neoclassicism in French Revolution

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 20). Greek Mosaics in Later Greek Art and Modern Art. https://ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mosaics-in-later-greek-art-and-modern-art/

"Greek Mosaics in Later Greek Art and Modern Art." IvyPanda , 20 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mosaics-in-later-greek-art-and-modern-art/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Greek Mosaics in Later Greek Art and Modern Art'. 20 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Greek Mosaics in Later Greek Art and Modern Art." August 20, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mosaics-in-later-greek-art-and-modern-art/.

1. IvyPanda . "Greek Mosaics in Later Greek Art and Modern Art." August 20, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mosaics-in-later-greek-art-and-modern-art/.

IvyPanda . "Greek Mosaics in Later Greek Art and Modern Art." August 20, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mosaics-in-later-greek-art-and-modern-art/.

A history of mosaics

Editorial feature.

By Google Arts & Culture

Vessel (?) Fragment (1st century B.C.–1st century A.D.) by Unknown The J. Paul Getty Museum

The art of puzzles

Mosaics have brought art and color to the walls and floors of Europe for thousands of years. Here are seven amazing mosaics that demonstrate how they have evolved from symbols of wealth and power to a way of ‘hacking’ public spaces in the 21st century. Very little has changed in the creation of mosaics since they first arrived in Europe from Mesopotamia around 4,000 or 5,000 years ago. Their hard-wearing nature has earned them the nickname ‘eternal pictures’ and we can still see some of the earliest examples today, like these vibrant Eastern Mediterranean fragments glass tesserae from around the 1st century BCE.

Mosaic fragments (From the collection of The J Paul Getty Museum)

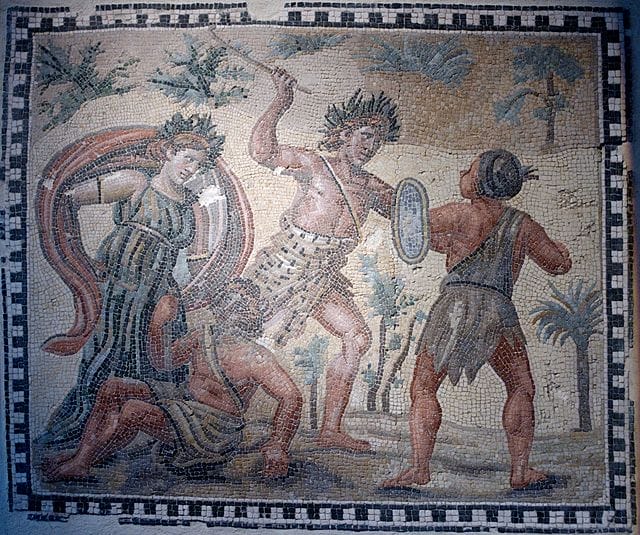

The Roman Empire carried the art form from Greece across the whole of Europe, where it found its way onto walls, ceilings and walkways, depicting everything from simple patterns to stories of daily life and heroic myths. A surviving how-to manual by the Roman architect Vitruvius explains how particularly complex designs were made off-site in panels known as emblemata, using trays which were then turned directly into position before the border designs were laid around them. A vivid example of the technique is this story of the fight between two famous gladiators, which was found in the ruins of baths on the Caelian Hill in Rome. In the bottom frame, the entangled warrior awaits a deadly blow from his opponent’s trident.

Gladiator mosaic (3rd century) Museo Arqueológico Nacional

Gladiator Mosaic (From the collection of Museo Arqueològico Nacional)

The birth of Islam in the 7th century AD brought a new meaning to mosaic art in Europe, particularly in Spain. There, almost 800 years of Moorish rule gave rise to the awe-inspiring mosaics of the Grand Mosque at Cordoba, painted here by the Spanish artist Ricardo Arredondo Calmache.

Planta de la bóveda y cúpula del mihrab (Mezquita de Córdoba). (1875/1879) by Ricardo Arredondo Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando

Planta de la bóveda y cúpula del mihrab (Mezquita de Códoba) (From the collection of Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando)

The Quran forbids pictures of God as sacrilegious. Mosaic artists rose to the challenge with intricate geometric and abstract designs of breathtaking beauty and perfection, which they created as expressions of their faith. Mosaics declined in popularity across Europe during the Renaissance, when frescoes were preferred for walls and ceilings, before the art of mosaic making blazed back into life during the Enlightenment. Some of the fabulous works from this era were so detailed they looked like paintings, such as this depiction of an archangel from Chapel of Saint John the Baptist in Lisbon created in 1750 by the painter Agostino Masucci and mosaicist Mattia Moretti.

Detail of the archangel at the Baptism of Christ mosaic panel, Chapel of Saint John the Baptist (1746/1750) by Agostino Masucci (painter) and Mattia Moretti (mosaicist) Museu de São Roque

Detail of the archangel at the Baptism of Christ mosaic panel by Agostino Masucci and Mattia Moretti (From the collection of Museu de São Roque)

During the Art Nouveau movement, from the late Victorian period to early 20th century, artists explored new forms and new technologies to create mosaics inspired by the elegant curved lines of plants and flowers. This is one of eight Art Nouveau ‘cartoons’ created by the great artist Gustav Klimt in 1910 that were turned into mosaics for the dining room of Stoclet House in Brussels. The image supposedly depicts Klimt himself in an embrace with his lover, Emilie Flöge.

Nine Cartoons for the Execution of a Frieze for the Dining Room of Stoclet House in Brussels: Part 8, Fulfillment (Lovers) (1910–1911) by Gustav Klimt MAK – Museum of Applied Arts

Lovers part of Nine Cartoons for the Execution of a Frieze for the Dining Room of Stoclet House in Brussels by Gustav Klimt (From the collection of MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts)

The archive picture below, dating back to 1914, depicts the dining room where the mosaic appeared.

View of the Dining Room at Palais Stoclet (1914) MAK – Museum of Applied Arts

View of the Dining Room at Palais Stoclet (From the collection of MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts)

Meanwhile, in Catalonia, artist Antonio Gaudí dismissed the painstaking perfectionism of earlier artists for a new style. In his radical new trencadís technique, traditional tesserae were laid alongside pieces of broken ceramics to cover structures of all shapes and sizes in brightly colored jumbles of ceramic and glass, often recycled from local factories. His vibrant, abstract work still inspires artists today, as with this bench created by students at the Universidade Santa Ursula in Brazil.

Gaudi Bench (2014) by Moema Branquinho Rio de Janeiro Department of Conservation

Gaudi Bench by Moema Branquinho (From the collection Rio de Janeiro Department of Conservation)

Today, the French street artist Invader is exploring yet another new direction by using them to ‘hack’ public spaces, spreading what he calls a “virus of mosaic”. His art is inspired by the space invaders of 1980’s video games, their mosaic tiles lending themselves perfectly to recreating old school 8-bit graphics.

Octopus (2011 - 2012) by Invader Rainlab

Octopus by Invader (From the collection of Rainlab)

Like the Romans, Invader carries his mosaics ready-made and puts them up on public walls under the cover of darkness, incognito behind a mask. Unlike the Romans however, his mosaics aren’t meant for the homes of the wealthy and powerful, but for everyone. They are part of the constant evolution and reinvention of mosaic across Europe that is destined to last as long as the art itself.

The Carioca’s Perceivings: from pavements to fashion

Rio de janeiro department of conservation, l'uomo che rubo' la gioconda, play and games in ancient greece, the j. paul getty museum, the hamzanama, mak – museum of applied arts, the painted ceiling of the church of são roque, museu de são roque, the marvelous city, art invasion, paris then and now: through the lens of eugène atget, gustav klimt at the "schweindl-fest“, saint roch: the plague, the cult and the image.

World History et cetera

Thinking with history.

Filter by Month

- August 2023

- November 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

Filter by Categories

- Behind the Scenes

- Exhibitions

- Uncategorized

Filter by Tags

The grandeur of roman mosaics.

R oman mosaics decorated luxurious domestic and public buildings across the empire. Intricate patterns and figural compositions were created by setting tesserae — small pieces of stone or glass — into floors and walls. Scenes from mythology, daily life, nature, and spectacles in the arena enlivened interior spaces and reflected the cultural ambitions of wealthy patrons. Introduced by itinerant craftsmen, mosaic techniques and designs spread widely throughout Rome’s provinces, leading to the establishment of local workshops and a variety of regional styles.

Drawn primarily from the Getty Museum’s collection, Roman Mosaics across the Empire at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, California, presents the artistry of mosaics as well as the contexts of their discovery across Rome’s ever growing empire — from its center in Italy to provinces in North Africa, southern France, and ancient Syria. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia speaks to Dr. Alexis Belis , assistant curator in the Department of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum, about the various kinds of mosaics found within the former Roman Empire.

Floor Panel, A.D. 4th century. Roman mosaic, Stone tesserae. H: 129.5 to 174 × W: 148 to 87.6 × D: 9.5 cm (51 to 68 1/2 × 58 1/4 to 34 1/2 × 3 3/4 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: Why do mosaics so captivate and enthrall us, Dr. Alexis Belis? Additionally, why did the Getty Villa decide to undertake an exhibition devoted to Roman mosaics ?

AB: Above all, mosaics are visually impressive in their size and appearance. They offer a vivid picture of ancient Roman life, revealing how Romans lived in surroundings filled with art and imagery. Their subjects — frequently dramatic narrative scenes that range from mythological and literary subjects to images of athletic contests and daily life — provide insight into Roman cultural values and artistic preferences. Since many are preserved in their original architectural contexts, usually decorating floors, mosaics also give us an idea of how the Romans experienced interior spaces.

The Getty Villa decided to organize an exhibition not just on Roman mosaics, but specifically on the Getty’s collection of Roman mosaics. Most have been in storage for decades, and some have never been displayed at all. The collection is significant because many of the mosaics were excavated during the early twentieth century and have known findspots. We also had the opportunity to present new research on the mosaics in an online publication — Roman Mosaics in the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Lion Attacking an Onager . Roman mosaic, from Hadrumetum (present-day Sousse, Tunisia), A.D. 150-200. Stone and glass. 38 ¾ x 63 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: Mosaics made their initial appearance during the Hellenistic Period thanks to the Greeks, but it was under the Romans that they became omnipresent across the Mediterranean world and beyond.

In what ways did the Romans differ from their Greek predecessors in their creation and appreciation of mosaics as an art form?

AB: While the Greeks refined the art of figural mosaics using pebbles embedded in mortar, the Romans took the art of mosaics to a completely new level, using tesserae of brightly colored stone and glass to create intricate patterns and figural scenes.

Mosaics are closely aligned with Roman culture, and the use of mosaic floors in this technique followed the spread of Roman power throughout the empire. We find a combination of Italian styles and local traditions in mosaic designs in many of the provinces, especially in what is present-day France and North Africa.

Bear Hunt. Roman mosaic, from Baiae. Italy, A.D. 300-400. Stone. 260 ¼ x 342 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Image courtesy of the The J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: In your own words, what else do mosaics tell us about ancient Rome and daily life across the empire? Mosaics were certainly a means through which wealthy Roman delineated their wealth and cultural pursuits, but what else did they convey and what secrets do they conceal?

AB: Mosaics tell us a great deal about ancient architecture . Because of their durability and the fact that they were built into the foundations of buildings, mosaics are among the best-preserved forms of Roman art. The locations and architectural settings of many mosaics have been recorded, and their placement sometimes relates to the function of the spaces they decorated.

For example, the Getty’s mosaic from Antioch , once decorated the entryway of a small public bath building. Other mosaic floors of the building depict busts of Soteria and Apolausis, the Greek personifications of Salvation and Enjoyment, respectively. Such themes would have been appropriate for spaces where Romans gathered for social interactions, entertainment, and to experience the revitalizing waters of the baths.

Some mosaics encourage the viewer to experience a space or room from different perspectives. A mosaic in the exhibition from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art has a central narrative scene bordered on all four sides by a hunting frieze. As the viewer follows the hunters and animals they walk around the mosaic and look at the images from different angles.

Combat between Dares and Entellus . Gallo-Roman mosaic, from Villelaure, France, A.D. 175-200. Stone and glass. 81 7/8 x 81 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: Which scenes or subject matter did the Romans favor most when creating mosaics, Dr. Belis?

AB: Scenes from Greek and Roman mythology as well as literature were especially prevalent. Two mosaics from the same villa in Gaul , found near the modern town of Villelaure, France, depict highly original scenes from Roman literature: a scene of Diana and Callisto from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), and a boxing match between Dares and Entellus from Virgil’s Aeneid . At the same time, a mosaic in the Getty’s collection found at Saint-Romain-en-Gal, also in France, represents the popular Greek myth of Orpheus charming the animals.

Scenes of hunting and capturing animals for the arena were also widespread, as shown in an enormous mosaic of a bear hunt from Baiae on the Bay of Naples. Wealthy Romans often financed the capture of wild animals for spectacles in the arena, which were therefore fitting subjects for mosaic floors in luxurious private villas.

Mosaics with these themes frequently decorated dining rooms and reception areas — spaces in which the owner could entertain and impress guests with his wealth, prestige, and social status.

Peacock Facing Left . Roman mosaic, from Syria, possibly Emesa (present- day Homs), A.D. 400 – 600. Stone 77 ½ x 45 ½ in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California, Gift of William Wahler. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

JW: You mentioned that Roman Mosaics across the Empire consists of mosaics drawn largely from the Getty Museum’s own collection. Among these, which do you find remarkable and worthy of further discussion in particular? Is there a pièce de résistance?

AB: Since most of the objects in the exhibition are from the Getty Museum’s own collection, they also give us a sense of J. Paul Getty’s own interest in mosaics. Getty acquired his first Roman mosaic (the one depicting a bust of Orpheus surrounded by animals) in 1949, and had it installed over the floor of one of the rooms in his new museum — a Spanish Colonial style ranch house where his collection was displayed until the Getty Villa opened in 1974.

The two mosaics from Villelaure, France, which are on view together for the first time in over a century, are especially interesting. They are remarkable in part because they decorated adjacent rooms of the same villa, revealing the diversity of the owner’s preferences. However, the Getty’s mosaic of Dares and Entellus also suggests a regional connection, as this uncommon scene occurs in at least four other mosaics in southern France.

Another significant mosaic is the one from the small bath complex at Antioch, which depicts a hare eating grapes and small birds surrounded by elaborate geometric designs. Since it was discovered during a series of campaigns in the 1930s, we have excavation photos that document the appearance of the mosaic in situ before it was removed from the building.

JW: Dr. Belis, I thank you so much for speaking with me about this lovely exhibition. I wish you many happy adventures in research!

AB: Thank you, James — I have really enjoyed talking with you about the exhibition!

Roman Mosaics across the Empire is on show at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, California until September 12, 2016. Click here to read and download the gallery text that accompanies the exhibition in PDF.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to AHE by the J. Paul Getty Museum have been done so as a courtesy. Interview edited by James Blake Wiener for AHE. Special thanks is extended to Ms. Desiree Zenowich, Senior Communications Specialist at J. Paul Getty Museum, for facilitating this interview. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2016. Please contact us for rights to republication.

Related posts:

- August 2016 Museum Listings

- September 2016 Museum Exhibitions

- October 2016 Museum Exhibitions

- June 2016 Museum Listings

Roman Mosaics

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

Roman mosaics were a common feature of private homes and public buildings across the empire from Africa to Antioch . Not only are mosaics beautiful works of art in themselves but they are also an invaluable record of such everyday items as clothes, food, tools, weapons, flora and fauna. They also reveal much about Roman activities like gladiator contests, sports, agriculture , hunting and sometimes they even capture the Romans themselves in detailed and realistic portraits.

Mosaics, otherwise known as opus tesellatum , were made with small black, white and coloured squares typically measuring between 0.5 and 1.5 cm but fine details were often rendered using even smaller pieces as little as 1mm in size. These squares ( tesserae or tessellae ) were cut from materials such as marble, tile, glass, smalto (glass paste), pottery , stone and even shells. A base was first prepared with fresh mortar and the tesserae positioned as close together as possible with any gaps then filled with liquid mortar in a process known as grouting. The whole was then cleaned and polished.

Origins & Influences

Flooring set with small pebbles was used in the Bronze Age in both the Minoan civilization based on Crete and the Mycenaean civilization on mainland Greece . The same idea but reproducing patterns was used in the Near East in the 8th century BCE. In Greece the first pebble flooring which attempted designs dates to the 5th century BCE with examples at Corinth and Olynthus. These were usually in two shades with light geometric designs and simple figures on a dark background. By the end of the 4th century BCE colours were being used and many fine examples have been found at Pella in Macedonia. These mosaics were often reinforced by inlaying strips of terracotta or lead, often used to mark outlines. Indeed, it was not until Hellenistic times in the 3rd century BCE that mosaics really took off as an art form and detailed panels using tesserae rather than pebbles began to be incorporated into patterned floors. Many of these mosaics attempted to copy contemporary wall paintings.

As mosaics evolved in the 2nd century BCE smaller and more precisely cut tesserae were used, sometimes as small as 4 mm or less, and designs employed a wide spectrum of colours with coloured grouting to match surrounding tesserae . This particular type of mosaic which used sophisticated colouring and shading to create an effect similar to a painting is know as opus vermiculatum and one of its greatest craftsmen was Sorus of Pergamon (150-100 BCE) whose work, especially his Drinking Doves mosaic, was much copied for centuries after. Besides Pergamon, outstanding examples of Hellenistic opus vermiculatum have been found at Alexandria and Delos in the Cyclades . Because of the labour involved in producing these pieces they were often small mosaics 40 x 40 cm laid on a marble tray or rimmed tray in a specialist workshop. These pieces were known as emblemata as they were often used as centre-pieces for pavements with more simple designs. So valuable were these works of art that they were often removed for re-use elsewhere and handed down form generation to generation within families. Several emblemata could make up a single mosaic and gradually, emblemata began to resemble more their surroundings when they are then known as panels.

Evolution in Design

With a subject such as mosaics where there are difficulties of dating, tremendous variance in artistic quality, public taste and regional conventions, it is problematic to describe a strictly linear evolution of the art form. However, some major points of change and regional difference can be noted.

Initially, the Romans did not diverge from the fundamentals of the Hellenistic approach to mosaics and indeed they were heavily influenced in terms of subject matter - sea motifs and scenes from Greek mythology - and the artists themselves, as the many signed Roman mosaics often bear Greek names, evidencing that even in the Roman world mosaic design was still dominated by Greeks. One of the most famous is the Alexander mosaic which was a copy of a Hellenistic original painting by either Philoxenus or Aristeides of Thebes . The mosaic is from the House of the Faun, Pompeii and depicts Alexander the Great riding Bucephalus and facing Darius III on his war chariot at the Battle of Issus (333 BCE).

Roman mosaics often copied earlier coloured ones, however, the Romans did develop their own styles and production schools were developed across the empire which cultivated their own particular preferences - large scale hunting scenes and attempts at perspective in the African provinces, impressionistic vegetation and a foreground observer in the mosaics of Antioch or the European preference for figure panels, for example.

The dominant (but not exclusive) Roman style in Italy itself used only black and white tesserae , a taste which survived well into the 3rd century CE and was most often used to represent marine motifs, especially when used for Roman baths (those from the first floor of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome are an excellent example). There was also a preference for more two-dimensional representations and an emphasis on geometric designs. In c. 115 CE at the Baths of Buticosus in Ostia there is the earliest example of a human figure in mosaic and in the 2nd century CE silhouetted figures became common. Over time the mosaics became ever more realistic in their portrayal of human figures and accurate and detailed portraits become more common. Meanwhile, in the Eastern part of the empire and especially at Antioch, the 4th century CE saw the spread of mosaics which used two-dimensional and repeated motifs to create a 'carpet' effect, a style which would heavily influence later Christian churches and Jewish synagogues.

Other Floor Designs

Floors could also be laid using larger pieces to create designs on a grander scale. Opus signinum flooring used coloured mortar-aggregate (usually red) with white tesserae placed to create broad patterns or even scattered randomly. Crosses using five red tesserae and a central tesserae in black were a very common motif in Italy in the 1st century BCE and continued into the 1st century CE but more typically using only black tiles.

Opus sectile was a second type of flooring which used large coloured stone or marble slabs cut into particular shapes. Opus sectile was another technique of Hellenistic origin but the Romans also expanded the technique to wall decoration. Used in many public buildings, it was not until the 4th century CE that it became more common in private villas and, under Egyptian influence, began to use opaque glass as the primary material.

![essay about mosaic art Opus Sectile Flooring [Hexagons]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/5535.jpg?v=1667403423)

Other Uses of Mosaic

Mosaics were by no means limited to flooring. Vaults, columns and fountains were often decorated with mosaic ( opus musivum ), again, especially in baths. The earliest example of this use dates to the mid-1st century BCE in the nymphaeum of the 'Villa of Cicero ' at Formiae where chips of marble, pumice and shells were used. In other locations pieces of marble and glass were also added the whole giving the effect of a natural grotto. By the 1st century CE more detailed mosaic panels were also used to embellish Nymphaea and fountains. In Pompeii and Herculanum the technique was also used to cover niches, walls and pediments and once again these murals often imitated original paintings. The walls and vaults of later Imperial Roman baths were also decorated in mosaic using glass which acted as a reflective of the sunlight hitting the pools and created a shimmering effect. The floors of the pools themselves were often set with mosaic as were the floors of mausolea, sometimes even incorporating a portrait of the deceased. Once again, the Roman use of mosaics to decorate wall space and vaults would go on to influence the interior decorators of Christian churches from the 4th century CE.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Amanda Claridge. Rome. Oxford University Press, USA, 2010.

- Martin Henig. A Handbook of Roman Art. Cornell Univ Pr, 1983.

- Mortimer Wheeler. Roman Art and Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 1985.

- Simon Hornblower. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, USA, 2012.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Related Content

Library of Pergamon

Roman Baths

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Cartwright, M. (2013, June 14). Roman Mosaics . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/498/roman-mosaics/

Chicago Style

Cartwright, Mark. " Roman Mosaics ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified June 14, 2013. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/498/roman-mosaics/.

Cartwright, Mark. " Roman Mosaics ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 14 Jun 2013. Web. 10 Sep 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Mark Cartwright , published on 14 June 2013. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- American History

- Ancient History

- European History

- Military History

- Medieval History

- Latin American History

- African History

- Historical Biographies

- History Book Reviews

- Sign in / Join

The History of Mosaic Art: An Ancient Art of Function and Design

Pictures and designs created with various types and colors of tessera (tile) and other materials form mosaic art with more than just a decorative purpose.

In its modern form, mosaic means a mixture or montage—a design created by a composite of shapes or photographs; but its ancient beginnings are of function and design. Around 3000 B.C., mosaic designs were created with clay cones imbedded, point first, into columns of the Stone Cone Temple in Urak, in Mesopotamia. This ancient cone mosaic art was a predecessor to the glass mosaic art of Egypt, the black and white pebble mosaics in eighth century B.C. Gordium (Gordion, Turkey), and the multi-textured Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Italian mosaics that followed.

Mosaic Art with a Purpose

The primitive patterned designs of the early cone mosaics added a decorative element to the pillars of ancient buildings, but the cones served another purpose. In Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), P. Roger S. Moorey—British archeologist and historian, specializing in the Ancient Near East—wrote, “At Urak, the decorative cone mosaics were particularly applied to free-standing columns and to walls with buttresses and recesses.”

In citing other resources, Moorey presents evidence that the mosaics were “patterned after rugs and mats hung as decoration on walls,” and that the decorations protected the walls from “wind and water erosion.” Moorey concludes that the cone mosaics, also found at other settlements in Mesopotamia, show that “the intimate relationship of protection and decoration is evident in most uses.”

Egyptian Glass

Small pieces of glass in mosaics were first used by the Egyptians during the New Kingdom (c. 1550 to 1069 B.C.). Very small pieces of dull-colored glass were used to make mosaic jewelry and mosaic stones. The stones were added to wall pieces and inlays, usually in funerary art. It wasn’t until the Roman Empire took control of Egypt in 31 B.C. that glass production would advance to a higher art form in Egypt. With an abundance of sand and soda, and with years of mastering the art, Egypt created much of the glass for the Roman nobles.

Pebble Mosaics and Tesserae

By the eighth century B.C., mosaics of random patterns were being assembled from black and white pebbles in Gordium (Gordion, Turkey). The pebble mosaics added art and design to an area and provided some protection during inclement weather. Six centuries later, mosaic floors—a precursor to the tile floors of today—were widespread among the Greek nobles. Smooth river rocks, with smaller pebbles used to fill in the gaps and create more detailed designs, were used to form floors and pathways. Mosaic art was further defined with the introduction of tesserae, pieces of stone and glass cut into small squares. These mosaic tiles of small uniform pieces made it much easier to create intricate designs.

Mosaic Art of the Roman Empire

As the Roman Empire expanded, mosaic art grew with it. The mosaics at Pompeii are an excellent example of the styles and types of designs the Romans preferred. Marble tiles became a popular choice for floor mosaics and styles ranged from geometric patterns to bucolic scenes. An excavation in Antioch (Antakya, Turkey) revealed one of the largest collections of mosaic floors from the second century A.D. Many are on display at the Hatay Archaeological Museum in Antakya.

Byzantine and Italian Mosaics

By the late fifth century, with the fall of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire came into power. With a surge in Christianity, mosaic art turned to religious subjects and the walls of churches, temples, and palaces displayed colorful intricate designs made with smalti, deeply colored glass tiles with uneven surfaces. Smalti were also made with gold and silver leaf, layered between two pieces of glass. While other tesserae were also used, with smalti, the variety of colors and the luster of gold or silver added another dimension to mosaic art.

During the sixth century, under Emperor Justinian’s rule, the Basilica di San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, was built with most of its walls and ceiling covered with mosaic art. The town has many other exceptional examples of Byzantine mosaic art and is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Rome and Venice are other towns in Italy with excellent examples of mosaic art. The art was popular throughout Italy during the late middle ages.

Historic Multicultural Mosaic Art

Mosaic art has a long and varied history, and although it was widely popular in Europe and the Near East, examples of ancient mosaics have been uncovered in China and South America. Mosaics served a purpose of protecting walls and floors from wind and water, as well as adding a decorative element With each advancing civilization, mosaic art advanced with it—from clay stones to colored glass, from smooth river rocks to tesserae and smalti. Today, mosaic art has become even more specialized with varied materials combined in a blending of artistic interpretation.

- Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence by P.R.S. Moorey

- Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative: Urak

- Report on the Manufacture of Glass by U.S.Census Office, 10th census, 1880, Joseph Dame Weeks

- A Short History of Ancient Egypt (website by André Dollinger)

- Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece by Nigel Guy Wilson

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

The Babylonian Captivity: The Influence of King Nebuchadnezzar II on the Jewish Exiles

The Domestic Roots of Ancient Alchemy: Women’s Work and their Role in the Science of Alchemy

The Legend of Dido: How the Myth of Carthage’s Legendary Queen Evolved

The First Paper: The Papyrus of Ancient Egypt

Amazons – Who Were the Ancient Female Warriors?

The Kyrenia Ship: Her Last Voyage

- Pantone Colors

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Principles of design

- Other materials

Ancient Greek and Hellenistic mosaics

- Roman mosaics

- Early Christian mosaics

- Early Byzantine mosaics

- Middle Byzantine mosaics

- Late Byzantine mosaics

- Medieval mosaics in western Europe

- Renaissance to modern mosaics

- Pre-Columbian mosaics

Periods and centres of activity

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- IOPscience - Arts and technology – Mosaic new techniques and procedures

- Art in Context - Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles

- Humanities LibreTexts - Turquoise mosaics, an introduction

- World History Encyclopedia - Mosaic

- mosaic - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Among the cultures of the ancient Middle East there is one remarkable occurrence of a mosaic-like technique: the exteriors of some large architectural structures dating from the 3rd millennium bce , at Uruk ( Erech ) in Mesopotamia , are decorated with long terra-cotta cones imbedded in the wall surface. The blunt, outer ends of the cones, coloured in red, black, and white, form patterns consisting of zigzag lines, lozenges, and other geometrical motifs. This revetment was decorative as well as functional, for the cones shielded the core of sun-dried bricks from rain and wind. The technique, however, died out and seems to have had no influence on the later development of mosaic.

Recent News

In western Asia Minor are preserved the earliest examples of the surface-covering technique that lead to mosaic in the present sense of the word. In the town of Gordium near modern Ankara in Turkey , houses have been uncovered with floors made of pebbles set in a primitive mortar . In some of these floors (dated to the 8th century bce ), rows of light pebbles form awkward geometrical figures against a background of darker stones. These rudimentary elements of decoration introduced into a crude form of pavement laying spurred artistic imagination and set in motion a process that was to bring spectacular results.

Three main phases can be determined in the development of mosaic art in antiquity. The first, chiefly a Greek matter, involved the gradual perfecting of the pebble medium. The second, which saw the invention and spreading of the tessera technique, took place partly in the Hellenistic Greek world and partly on Roman soil. The third, largely a Roman phenomenon, was characterized by the popularization of mosaic and the application of the medium to new functions. By a process of diffusion , the taste in floor decoration documented at Gordion spread through the Greek-speaking world of the Mediterranean. Its first full flourishing seems to have occurred in late Classical times. Pebble mosaics are found as far west as Sicily (Motya, Morgantina) and, in the east, in the Greek colonies on the Crimean Peninsula (Cherson). They are preserved in large number at only two sites, Olinthos and Pella, in Macedonian northern Greece.

In the town of Olinthos there are floor mosaics, with elaborate figures and complicated patterns, which were part of the new city culture that developed in the 5th century bce . The Olinthos mosaics also reveal that picture making with light and dark pebbles had by then evolved into an intricate art. Against a ground set with black or blue-black stones stand figures or patterns set with white or slightly tinted ones. Pebble size had become fairly uniform, with diameters from one to two centimetres, but particularly intricate areas, like faces, are set with smaller stones. Very small black pebbles serve as outlines. Although the mortar between them is visible, the pebbles are set close enough so that the pictures appear with regular, not too broken outlines and with some emphasis on detail.

Floors in houses at Pella , dating from the 4th century bce , demonstrate a significant later development of the pebble technique. Floor mosaics then openly vied with wall painting in the rendering of space and realistic detail. This was made possible by the introduction of new materials that eliminated the shortcomings of the ordinary pebble medium. Among the basic changes was an increase in the range of colours. When the demand for particular tints could not be met with pebbles of natural colours, “artificial pebbles” were made and are found in several of the floors at Pella. These “pebbles” have been painted in the required tones—mostly strong green and red—and, to protect the film of paint, have a depression sunk in the middle. The new trend also called for smaller pebbles to permit pictures to be set more closely. To obtain precise delineation of limbs and features, outlines made not with pebbles but with long strips of terra-cotta or lead wire were employed. Pictures made in this technique reflect a taste for heroic hunt scenes and fights with wild animals, themes inspired from court art glorifying the ruler.

The next innovation came at the end of the 4th or the beginning of the 3rd century bce , when the introduction of new principles led to the abandonment of the pebble technique. Cut mosaic pieces permitted the nearly complete elimination of the disturbing effects of visible mortar patches, and new materials, above all glass , offered a vast new range of colours. The acceptance of the new methods and materials seems, however, to have come about slowly. In Alexandria (Greco-Roman Museum) there is a mosaic (depicting Erotes fighting a stag and, in the outer border, a frieze of animals) in which cut, triangular tesserae are used together with both pebbles and lead wire. In somewhat later Alexandrian mosaics made with tesserae (late 3rd or early 2nd century bce ), lead threads are still in use—for example, in a panel, signed by the artist Sophilos and depicting a personification of Alexandria, that is the earliest known example of miniature mosaic work (called opus vermiculatum , meaning “wormlike work” because of the close-set, undulating rows of small tesserae).

Pergamum , another centre of the Hellenistic world, was particularly famous for its school of mosaics. According to the ancient Roman historian Pliny the Younger , Sosos, one of the most renowned mosaic artists of antiquity , worked in this city. None of his works survives but, thanks to Roman copies, the intentions that underlay his art can be judged. Pliny listed as his most celebrated works a representation of drinking doves and a clever imitation of the “unswept floor” of a banquet room ( asarōtos oikos ). The copies tell of Sosos’s phenomenal ability to create trompe l’oeil (“fool-the-eye”) effects through a shading and colouring that seems to bring the objects out in full plasticity on the ground on which they are depicted. To call the work merely an imitation of painting may be incorrect. The intense colours and the smooth texture permitted by the new setting technique paved the way for illusionistic effects that went beyond those achieved by painting.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Glass from islamic lands.

Goblet with Incised Designs

Ewer with Molded Inscription

Glass Bowl in Millefiori Technique

Bottle with Blue Trails

Mosque Lamp of Amir Qawsun

'Ali ibn Muhammad al-Barmaki ?

Stefano Carboni Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Qamar Adamjee Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2002

At the time of the Arab conquest in the seventh century A.D. , glassmaking had flourished in Egypt and western Asia for more than two millennia and glassmakers in those regions went about their business despite the momentous political, social, and religious changes taking place around them. Glassmakers inherited many of the techniques of their forebears in the Byzantine and Sasanian empires , including glassblowing, the use of molds, the manipulation of molten glass with tools, and the decorative application of molten glass. Islamic glass production from the seventh through the fourteenth century was also greatly innovative and witnessed glorious phases—such as those of superb relief-cut glass and spectacular gilded and enameled objects —that established its supremacy in glassmaking manufacture throughout the world.

While many of the objects may not have been made under a ruler’s patronage, they certainly are “fit for a sultan.” Islamic glass can be better studied according to the techniques of its manipulation—from undecorated blown vessels to mosaic glass to mold-blown , hot-worked , cut and engraved , and painted objects , though vessels produced after the seventeenth century and greatly influenced by the European trade may be studied in a proper historical context.

In the field of Islamic art, glass is a craft that often rose to excellence but has been largely overlooked by art historians. Thousands of anonymous glassmakers, from Cairo to Delhi, proudly transmitted their knowledge from one generation to the next, experimenting with the colors, shapes, techniques, and surface decoration of this extraordinarily versatile material. Their most outstanding results, from public and private collections worldwide, encourage a widespread appreciation of the artistic forms of Islamic glass—a fitting legacy for this ancient craft.

Tools of the Glassmakers Since the invention of glassblowing in the first century B.C. , glassmakers have been using the same tools to model, manipulate, and decorate molten glass. Two molds from the medieval Islamic world are the only ones to survive, but the basic technology of nonindustrial glassmaking and the tools employed have not changed.

The blowpipe is an iron or steel tube, usually about five feet long, for blowing a parison, or gather, of molten glass. Molds are used to impress decorative patterns on the parison. Dip molds have the typical form of a conical beaker, but two- or three-part hinged molds were also used in the Islamic world. The pontil, a solid metal rod that is applied to the base of a vessel to hold it after it is cut off from the blowpipe, became a common tool in the early Islamic period (seventh–eighth century). The pontil leaves an irregular ring-shaped mark on the base that is commonly known as a “pontil mark.” Wooden blocks, jacks, and shears are used to shape an object. Blocks are used to form the gather into a sphere prior to inflation; jacks, to shape the mouth of an open vessel; and shears, to trim excess hot glass during production. A marver—a smooth flat stone or metal surface over which softened glass is rolled—is also an essential tool of the glassmaker. Of course, no tool would be of much use without a glassmaker’s dexterity and talent.

Archaeological Excavations Scientific excavations are extremely valuable for a better understanding of the history, art, architecture, urban planning, and everyday life of a specific site. In terms of material culture, glass objects and fragments are second in quantity only to pottery at most Islamic sites, offering a wide variety of shapes, colors, and decoration for analysis.

There are, however, a number of problems related to the study of excavated Islamic glass. Only in exceptional cases do glass objects bear informative inscriptions providing names and dates. Both as luxury goods that were traded and exchanged and as simple containers for oils, perfumes, and liquids of all kinds, Islamic glass circulated throughout the Islamic world and as far as southeastern Asia, northern China, and Europe . Glass was also shipped in large quantities as cullet (glass lumps and discarded broken vessels), suitable for remelting and making new glass inexpensively. Thus, the glass of a bottle created in Egypt, for example, may have been recycled as far as Central Asia; a new object may have been made that had a chemical composition usually attributed to Egyptian vessels but a shape and decoration that suggested a different origin. While it clearly is problematic for scholars to determine their place or date of production, excavated objects may be of great help in better understanding the chronology and origin of Islamic glass. The three most prolific excavated sites that have yielded glass in the Islamic world are Fustat (Old Cairo) in Egypt, Samarra in Iraq, and Nishapur in northeastern Iran.

Carboni, Stefano, and Qamar Adamjee. “Glass from Islamic Lands.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/igls/hd_igls.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Allan, James, ed. Islamic Art in the Ashmolean Museum . 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 1995. For marvered glass, see pp. 1–30, 31–50.

Carboni, Stefano. "Zudjadj." In Encyclopaedia of Islam , vol. 11, pp. 552–54. New ed. Leiden: Brill, 960–.

Carboni, Stefano. "Undecorated Glass." In Glass from Islamic Lands: The al-Sabah Collection , pp. 139–61. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Carboni, Stefano. Glass from Islamic Lands: The al-Sabah Collection , pp. 163–95, 261–89, 291–321. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Carboni, Stefano. "Glass with Cut Decoration." In Glass from Islamic Lands: The al-Sabah Collection , pp. 71–137. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Carboni, Stefano. "Glass Production in the Fatimid Lands and Beyond." In L'Égypte fatimide, son art et son histoire , edited by Marianne Barrucand, pp. 169–77. Paris: Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne, 1999.

Carboni, Stefano. "Stained ('Luster-Painted') Glass." In Glass from Islamic Lands: The al-Sabah Collection , pp. 51–69. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Carboni, Stefano. "The Great Era of Enamelled and Gilded Glass." In Glass from Islamic Lands: The al-Sabah Collection , pp. 323–69. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Carboni, Stefano, and David Whitehouse. Glass of the Sultans . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002. See on MetPublications

Charleston, Robert J. Masterpieces of Glass: A World History from the Corning Museum of Glass . Expanded ed. New York: Abrams, 1990.

Gudenrath, William. "Techniques of Glassmaking and Decoration." In Five Thousand Years of Glass , edited by Hugh Tait, pp. 213–41. London: British Museum Press, 1991.

Oliver, Prudence. "Islamic Relief-Cut Glass: A Suggested Chronology." Journal of Glass Studies 3 (1961), pp. 9–29.

Stern, E. Marianne, and Birgit Schlick-Nolte. Early Glass of the Ancient World, 1600 B.C.–A.D. 50 . Ostfildern: Verlag Gerd Hatje, 1994.

Ward, Rachel, ed. Gilded and Enamelled Glass from the Middle East . London: British Museum, 1998.

Whitehouse, David. "The Corning Ewer: A Masterpiece of Islamic Cameo Glass." Journal of Glass Studies 35 (1993), pp. 48–56.

Additional Essays by Stefano Carboni

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Venice and the Islamic World: Commercial Exchange, Diplomacy, and Religious Difference .” (March 2007)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Islamic Art and Culture: The Venetian Perspective .” (March 2007)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Venice and the Islamic World, 828–1797 .” (March 2007)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Venice’s Principal Muslim Trading Partners: The Mamluks, the Ottomans, and the Safavids .” (March 2007)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ A New Visual Language Transmitted Across Asia .” (October 2003)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Courtly Art of the Ilkhanids .” (October 2003)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Folios from the Great Mongol Shahnama (Book of Kings) .” (October 2003)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Folios from the Jami‘ al-tavarikh (Compendium of Chronicles) .” (October 2003)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Takht-i Sulaiman and Tilework in the Ilkhanid Period .” (October 2003)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ The Art of the Book in the Ilkhanid Period .” (October 2003)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Blown Glass from Islamic Lands .” (October 2002)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ Cut and Engraved Glass from Islamic Lands .” (October 2002)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ The Legacy of Genghis Khan .” (October 2003)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ The Mongolian Tent in the Ilkhanid Period .” (October 2003)

- Carboni, Stefano. “ The Religious Arts under the Ilkhanids .” (October 2003)