- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 20 March 2020

Side effect concerns and their impact on women’s uptake of modern family planning methods in rural Ghana: a mixed methods study

- Leah A. Schrumpf ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9797-4682 1 ,

- Maya J. Stephens 1 ,

- Nathaniel E. Nsarko 2 ,

- Eric Akosah 2 ,

- Joy Noel Baumgartner 1 ,

- Seth Ohemeng-Dapaah 2 &

- Melissa H. Watt 1

BMC Women's Health volume 20 , Article number: 57 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

16 Citations

17 Altmetric

Metrics details

Despite availability of modern contraceptive methods and documented unmet need for family planning in Ghana, many women still report forgoing modern contraceptive use due to anticipated side effects. The goal of this study was to examine the use of modern family planning, in particular hormonal methods, in one district in rural Ghana, and to understand the role that side effects play in women’s decisions to start or continue use.

This exploratory mixed-methods study included 281 surveys and 33 in-depth interviews of women 18–49 years old in the Amansie West District of Ghana between May and July 2018. The survey assessed contraceptive use and potential predictors of use. In-depth interviews examined the context around uptake and continuation of contraceptive use, with a particular focus on the role of perceived and experienced side effects.

The prevalence of unmet need for modern family planning among sexually active women who wanted to avoid pregnancy ( n = 135) was 68.9%. No factors were found to be significantly different in comparing those with a met need and unmet for modern family planning. Qualitative interviews revealed significant concerns about side effects stemming from previous method experiences and/or rumors regarding short-term impacts and perceived long-term consequences of family planning use. Side effects mentioned include menstrual changes (heavier bleeding, amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea), infertility and childbirth complications.

As programs have improved women’s ability to access modern family planning, it is paramount to address patient-level barriers to uptake, in particular information about side effects and misconceptions about long-term use. Unintended pregnancies can be reduced through comprehensive counseling about contraceptive options including accurate information about side effects, and the development of new contraceptive technologies that meet women’s needs in low-income countries.

Peer Review reports

Modern family planning methods are a cost-effective strategy for reducing high-risk pregnancies, decreasing unsafe abortions, and allowing for birth spacing and limiting [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Despite advances in contraceptive technology and availability, 214 million women had an unmet need for modern family planning in 2017 [ 5 ].

In order to inform the delivery of family planning services, it is important to understand the factors and characteristics that contribute to a woman’s decision to use modern family planning. Demographic factors influencing family planning use may include age, family size, distance from a health care facility and education level [ 6 , 7 ]. Additionally, family planning use is influenced by women’s norms and perceptions. Women may face cultural or religious pressures against using family planning, often rooted in beliefs that family planning leads to unfaithfulness or interferes with goals of procreation [ 7 , 8 ].

Side effects of modern family planning methods, either experienced or anticipated, have been identified as a common reason that women either choose not to start or discontinue contraceptives. Side effects include menstrual changes (heavier bleeding, amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea), changes in weight, headaches, dizziness, nausea, and cardiovascular impacts. In addition, women may harbor fears of long-term effects of contraceptive use, such as infertility and childbirth complications [ 8 , 9 ]. A 2014 systematic review found a significant proportion of women attributed their unmet need for family planning to a fear of side effects: 28% in Africa, 23% in Asia, and 35% in Latin America and the Caribbean [ 10 ]. A fear of side effects may occur when a woman or someone she knows has experienced side effects with a method, or when rumors or overestimations or rare complications are considered factual [ 7 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 ].

Ghana has historically had one of the highest rates of unmet need for family planning in Africa, despite having a relatively strong family planning program. Ghana’s rate of unmet need among married women is 32.9 whereas many surrounding countries have a lower rate of unmet need among married women including Senegal (26.2), Nigeria (23.7) and Cote d’Ivoire (30.9) [ 14 ]. Family planning methods are available at both private and public healthcare facilities and offer a diverse contraceptive mix, including injectables, implants and hormonal birth control pills [ 8 ]. The Amansie West district has 22 public health facilities, comprised of 6 health centers and 16 Community-based Health Planning and Services compounds, 5 private health facilities and 1 hospital. Within these various health facilities modern family planning methods (pills, intrauterine devices (IUDs), and implants) can be administered by trained medical doctors, midwives, and trained Community Health Officers. Nurses in health facilities are able to administer pills and condoms. Outside of health facilities condoms, pills, and injectables are available at pharmacies and drug shops [ 15 , 16 ].

Despite efforts to make contraceptives accessible, about one-third of married women have an unmet need for family planning [ 17 ]. Although the use of modern family planning methods has increased from 5 to 22% between 1988 and 2014, one in four contraceptive users discontinued use within the first year. The main reason reported for discontinuing injectables and implants were side effects or other health concerns and health concerns as a reason for non-use of modern methods in Ghana has been growing over time [ 12 , 17 ].

This study was conducted with the goal of understanding modern family planning use in a rural setting of Ghana with three aims. First, we aimed to estimate the prevalence of modern family planning use and the prevalence of unmet need for modern family planning. Second, we identified factors associated with unmet need for modern family planning use, including factors at an individual, household and health care level. Lastly, we sought to qualitatively examine and understand women’s experiences with choices and behaviors related to family planning use, with a focus on the role of side effects. This data can help inform the delivery of modern contraceptives to all women wanting to delay or limit their pregnancies.

This exploratory mixed-methods study was conducted in the Amansie West District, in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. The population of the area is almost entirely rural (95.6%), with an estimated population of 149,437 in 2014 and annual growth of 2.7% [ 18 , 19 ].

The study included 281 household surveys and 33 in-depth interviews of women 18–49 years old from six subdistricts of the Amansie West District. Data were gathered from May to July 2018 as part of a larger study examining the role of community health workers (CHWs) in family planning use. Six of the seven subdistricts within the Amansie West District were selected based on accessibility and penetration of the national CHW program. The six sub-districts were divided into 11 geographical zones containing at least 100 women of reproductive age (18–49) whose household was registered by a CHW. An average of 30 women were recruited from each zone in order to have geographic representation in our sample; the final sample size was informed by the resources available to us in this study. A subset of individuals who completed the household survey were purposively sampled to participate in a separate in-depth interview. Participants for the in-depth interview were selected based on current, past or lack of modern method use.

To collect the survey data, a team of six female research assistants, bilingual in English and Twi, were trained in ethics and research procedures. The research assistants approached women in their homes to tell them about the study and invite them to participate. After written informed consent, the research assistant administered the structured interview using an electronic tablet, which took approximately 45 min. At the end of the interview, participants were asked if they might be interested in taking part in a subsequent in-depth interview; if yes, then their contact information was collected to schedule the interview at a later time.

To conduct in-depth interviews (IDIs), three bilingual nurses from the district were trained on research ethics and qualitative research. IDIs were scheduled in participants’ homes at a time that was convenient and maximized privacy. Participants were provided a separate written informed consent for the IDI, which included consent for audio recording. IDIs were conducted in Twi and lasted on average 30 min. Following each interview, field notes were written and then later reviewed with the full research team.

Instruments

Structured survey.

The structured survey was created based on a review of the literature and consultation with local public health professionals. The survey was locally translated into Twi and reviewed by multiple individuals to confirm accurate translation. The survey was pre-tested in a rural community prior to data collection, which resulted in slight modifications.

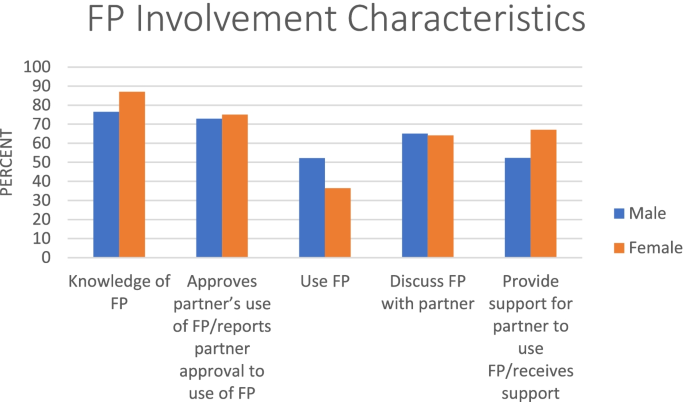

The survey included the following constructs: demographics; pregnancy history; knowledge and perceived availability of various forms of contraceptives; use of contraceptives; pregnancy intention and attitudes towards pregnancy (α = 0.81); depression PHQ-9 (α = 0.74); autonomy (α = 0.77); partner communication (α = 0.74); freedom from coercion (α = 0.80); and partner support (α = 0.80) [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ].

In-depth interviews

The in-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured guide that included open-ended questions and probes to explore community and individual perspectives of family planning, barriers to use, experiences with family planning use, and reasons for using or not using family planning. The interview guide developed for this study, available as a supplementary file, was reviewed by local public health professionals and pretested in the community. Research assistants translated the guide into Twi during the interviews to adjust the phrasing for a natural, casual conversation.

Data analysis

Survey data were analyzed using R Studio. In order to define a population that could be in need of community-based contraception, we excluded individuals who were not sexually active (defined as three months since last sex), currently pregnant, wished to become pregnant in the next few months, or reported being infertile (includes hysterectomy) from the analysis. This resulted in a sample for analysis of 135 women. While definitions of unmet need for population level analyses typically include women, who have unwanted/mistimed pregnancies the parent study was particularly interested in community level modern family planning method gaps that might be facilitated by community health workers. We were also most interested in highly effective modern methods and thus current use of natural and barrier methods were also excluded from our main analyses. Individuals were classified as having an unmet need for modern contraception if they met the criteria for inclusion but reported that they were not using a hormonal method (pills, injectables, implants), female sterilization, male sterilization or an IUD. After examining descriptive statistics, bivariate analysis explored whether key factors were significantly associated with unmet need for these highly effective modern family planning methods. Because bivariate statistics were not significant, multivariate statistics were not used.

Qualitative analysis was conducted using applied thematic analysis [ 25 ]. Audio recordings were simultaneously translated and transcribed in English. NVivo 12 was used to facilitate the organization and coding of transcripts. Emergent themes were identified through an iterative process of summary memos and open coding, which led to the development of a structured codebook. Overarching domains were created as parent codes, and child codes were used to organize emerging themes. Coded texts were reviewed and synthesized, and representative quotes were identified to capture meaning and provide context.

Demographics

Table 1 summarizes the demographics of the sub-sample of participants who had a current need for modern family planning ( n = 135). On average, participants were 29.4 years of age. About half (45%, n = 61) were married. In this community couples who have undergone customary marital rights or those that are living together with children were considered to be married. Half of the participants (52%, n = 70) had three or more children. Education was low, with only 15.6% of participants reporting any secondary school education.

Family planning use

Considering the family planning needs of the sample, 31.1% ( n = 42) had a met need, and 68.9% ( n = 93) had an unmet need. More than half ( n = 23) of women with a met need were using the injectable, Depo-Medroxyprogesterone (DMPA) (Table 2 ). In the bivariate analysis of factors potentially associated with family planning use (i.e., pregnancy intentions and attitudes, depression, level of autonomy, communication with their partner, freedom from coercion and levels of partner support), none of the measures were significantly associated (Table 3 ).

Qualitative insights on family planning use

In the qualitative data, two prominent themes emerged to explain unmet need: concerns about side effects and misconceptions about the long-term effects of family planning (Table 4 ).

- Side effects

Side effects were mentioned as a potential concern in all qualitative interviews. For many, the concerns about side effects outweighed the perceived benefits of using family planning. Of the 17 participants who had discontinued family planning use, only 5 reported experiencing side effects themselves, while the majority recited side effects they believed were associated with modern family planning use. The most common concern about hormonal contraceptives was the resultant changes in menstrual patterns. There was a belief that menstruation was a means of cleansing the body, and concerns that a lack of menstruation could lead to sickness, dizziness, bloating, and fainting. Additionally, amenorrhea was concerning for women because they could no longer monitor whether or not they were pregnant.

In addition to changes in menstruation, participants mentioned other side effects they were concerned about, including sickness, dizziness, and changes in weight. Reduction in weight was seen as an undesirable side effect, while weight gain was seen as a desirable side effect. The seven participants currently using DMPA had experienced at least one of these side effects. Even in cases where participants reported support from their partner, family or religious community to use family planning, anxiety about side effects deterred them from using family planning—support was not enough to overcome what the women articulated as unacceptable side effects. Women who had not experienced side effects themselves discussed side effects as the most common reason that other women did not use modern family planning.

Misconceptions about long-term impacts

Participants both using and not using a modern contraceptive method reported misconceptions in the community, particularly about hormonal methods. The most common misconceptions were rumors about the long-term adverse effects caused by modern family planning. Women recited rumors that family planning use led to fibroids, infertility, birth complications, and even premature death. In most cases, these long-term impacts were attributed to changes in menstrual patterns, typically associated with injectables and implants.

Three participants discussed rumors that implants caused fainting and death due to a restriction in blood flow. The rumors and misconceptions that were reported about family planning use spanned all 14 communities that were included in the qualitative portion of the study, illustrating the ubiquitous nature of these concerns.

Knowledge of modern family planning methods is high throughout Ghana; nationwide, 99% of women with an unmet need for family planning identified at least one modern method [ 17 ]. Despite high levels of knowledge, we found that among 135 women who were sexually active and wanting to avoid pregnancy, a majority (68.9%) had an unmet need for a highly effective modern family planning method. When examining factors that might explain unmet need, no significant associations were identified. Our qualitative data suggests that fear of side effects and misconceptions about family planning methods is likely driving the gap between knowledge and behavior in family planning use. This study suggests a need to address accurate information about family planning methods, especially injectables the most common form of modern family planning in African countries [ 26 ]. Addressing structural barriers of access to contraceptives will be insufficient if misinformation about side effects and long-term adverse effects persist.

In order to meet the needs of women who wish to postpone or limit their pregnancies, it is important to have targeted interventions to address the fears and concerns caused by menstrual bleeding changes that frequently occur with hormonal methods such as injectables and implants. This is especially important in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where the use of injectables is being prompted due to its higher effectiveness level, as compared to oral hormonal pills, and the ability to use the product discretely [ 27 , 28 ]. The universal concern about menstruation in our sample demonstrates the need for improved counseling, before and during use, to educate women about the role of menstruation in reproduction and how hormones impact menstrual patterns [ 8 , 12 , 13 ]. Both uptake and continuation of reversible contraceptives requires regular counseling, scheduled follow-up, and clinical management of contraceptive side effects [ 29 ]. Health workers, including CHWs, involved in providing family planning education and provision should be equipped to provide reproductive education to help women understand and differentiate between nonharmful and harmful side effects. FHI360 has developed a job aid called “NORMAL” to help health workers counsel clients on expected changes of menstruation on various forms of hormonal contraception [ 9 ]. There is evidence that job aids with accurate injectable information have been shown to increase injectable use in low-resource settings and could be adapted to the Ghanaian context [ 30 ]. CHWs need additional training to help women understand and manage side effects from modern family planning. Job aids such as “NORMAL” could provide CHWs with a tool to better counsel and manage clients regarding uptake and continuation of family planning methods. Comprehensive counseling, including accurate information on side effects, has been shown to increase continuation of modern methods [ 31 , 32 ]. Additional qualitative research among different communities is needed to understand the beliefs that underlie women’s concerns about menstrual changes. Better understanding these beliefs can inform culturally congruent counseling approaches to promote the uptake and sustainability of family planning methods.

Certain side effects will always be considered unacceptable for some women, making their family planning options more limited. A long-term solution for family planning coverage requires investments in new contraceptive technologies that are responsive to women’s preferences and needs. This includes the development of both hormonal and nonhormonal long-acting reversible contraceptives that are accessible and effective in low-income settings. Several new contraceptive technologies under development may hold promise, including biodegradable implants, longer-acting injectables, IUDs that are easier to insert, and non-hormonal vaginal rings [ 33 , 34 ]. Hopefully, these new technologies will address some barriers to family planning use and provide more options for women and couples to limit or space their pregnancies.

The study findings must be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. First, social desirability biases may be present in the survey results. The in-depth interviews were conducted by local nurses responsible for administering family planning methods in the clinics; therefore, participants may have been less likely to speak negatively about services or areas in which the nurses work. It is important to note variation among these interviews, as some participants were more willing to discuss and share than others. Second, the in-depth interviews were simultaneously translated and transcribed from the local language, Twi, into English; therefore, some details and phrasing may have been lost in the process. Third, the sample size for the survey was not powered to detect statistically significant differences. Lastly, we did not explore more deeply whether women felt their family planning needs were being met via barrier and/or natural methods—although less effective, some women and couples purposefully choose this option.

Even as modern contraceptives become increasingly accessible, women may perceive potential drawbacks of highly effective family planning methods to outweigh the benefits. The future of family planning research and implementation should focus on developing and implementing evidence-based counseling tools to promote the uptake and continuation of the current method mix and investing in the development of new family planning technologies that fit the lifestyles and needs of women in LMICs.

Availability of data and materials

The data and all related study materials may be requested from the faculty mentor on this study (Dr. Melissa Watt, [email protected] ).

Abbreviations

Community Health Worker

Demographic Health Survey

Depo-Medroxyprogesterone

Estradiol valerate/norethisterone enantate

In-depth interview

Intrauterine device

Low- and middle-income countries

Ahmed S, Li Q, Liu L, Tsui AO. Maternal deaths averted by contraceptive use: An analysis of 172 countries. Lancet. 2012;380(9837):111–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60478-4 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Beson P, Appiah R, Adomah-Afari A. Modern contraceptive use among reproductive-aged women in Ghana: Prevalence, predictors, and policy implications. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0649-2 .

Chola L, McGee S, Tugendhaft A, Buchmann E, Hofman K. Scaling Up Family Planning to Reduce Maternal and Child Mortality: The Potential Costs and Benefits of Modern Contraceptive Use in South Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0130077. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130077 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Starbird E, Norton M, Marcus R. Investing in Family Planning: Key to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Global Health Sci Pract. 2016;4(2):191–210 https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-15-00374 .

Article Google Scholar

Guttmacher Institute. ADDING IT UP: Investing in Contraception and Maternal and Newborn Health, 2017: Guttmacher Institute; 2017. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/adding-it-up-contraception-mnh-2017 Accessed 27 Dec 2018.

Ebrahim NB, Atteraya MS. Structural correlates of modern contraceptive use among Ethiopian women. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(2):208–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1383993 .

Wulifan JK, Brenner S, Jahn A, De Allegri M. A scoping review on determinants of unmet need for family planning among women of reproductive age in low and middle income countries. BMC Womens Health. 2015;16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0281-3 .

Staveteig S. Fear, opposition, ambivalence, and omission: Results from a follow-up study on unmet need for family planning in Ghana. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0182076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076 .

Rademacher KH, Sergison J, Glish L, Maldonado LY, Mackenzie A, Nanda G, Yacobson I. Menstrual Bleeding Changes Are NORMAL: Proposed Counseling Tool to Address Common Reasons for Non-Use and Discontinuation of Contraception. Glob Health. 2018;6(3):8.

Google Scholar

World Health Organization. (2018, February 8). Family planning/Contraception. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/family-planning-contraception Accessed 27 Dec 2018.

Casterline JB, Sathar ZA, Haque, M. ul. Obstacles to Contraceptive Use in Pakistan: A Study in Punjab. Stud Fam Plan. 2001;32(2):95–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00095.x .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Machiyama K, Cleland J. Unmet Need for Family Planning in Ghana: The Shifting Contributions of Lack of Access and Attitudinal Resistance. Stud Fam Plan. 2014;45(2):203–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00385.x .

Sedgh G, Hussain R. Reasons for Contraceptive Nonuse among Women Having Unmet Need for Contraception in Developing Countries. Stud Fam Plan. 2014;45(2):151–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00382.x .

Family Planning 2020. (n.d.). Retrieved December 4, 2019, from https://www.familyplanning2020.org/countries .

Lebetkin E, Orr T, Dzasi K, Keyes E, Shelus V, Mensah S, et al. Injectable Contraceptive Sales at Licensed Chemical Seller Shops in Ghana: Access and Reported Use in Rural and Periurban Communities. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;40(01):021–7. https://doi.org/10.1363/4002114 .

Perry R, Sharon Oteng M, Haider S, Geller S. A brief educational intervention changes knowledge and attitudes about long acting reversible contraception for adolescents in rural Ghana. J Pregnancy Reprod. 2017;1(1). https://doi.org/10.15761/JPR.1000106 .

The DHS Program. Demographic and Health Surveys. In: Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Rockville: GSS, GHS, and ICF International; 2015. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR307/FR307.pdf . Accessed 11 Dec 2018.

Ghana Statistical Service. 2010 Population and housing census district analytical report: Amansie West. 2014. https://new-ndpc-static1.s3.amazonaws.com/CACHES/PUBLICATIONS/2016/06/06/Amansie+West+2010PHC.pdf Accessed 27 Dec 2018.

Nuamah GB, Agyei-Baffour P, Akohene KM, Boateng D, Dobin D, Addai-Donkor K. Incentives to yield to Obstetric Referrals in deprived areas of Amansie West district in the Ashanti Region, Ghana. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0408-7 .

Watt HM, Knettel AB, Choi WK, Knippler TE, May AP, Seedat S. Risk for Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies Among Women at Drinking Venues in Cape Town, South Africa. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78(5):795–800. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2017.78.795 .

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J General Int Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x .

Rominski SD, Gupta M, Aborigo R, Adongo P, Engman C, Hodgson A, Moyer C. Female autonomy and reported abortion-seeking in Ghana, West Africa. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;126(3):217–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.03.031 .

Upadhyay UD, Dworkin SL, Weitz TA, Foster DG. Development and Validation of a Reproductive Autonomy Scale. Stud Fam Plan. 2014;45(1):19–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00374.x .

Norbeck JS, Lindsey AM, Carrieri VL. Further Development of the Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire: Normative Data and Validity Testing. [Editorial]. Nurs Res. 1983;32(1):4–9.

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2012. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384436 .

Book Google Scholar

Bertrand JT, Sullivan TM, Knowles EA, Zeeshan MF, Shelton JD. Contraceptive Method Skew and Shifts in Method Mix in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;40(03):144–53. https://doi.org/10.1363/4014414 .

Bigrigg A, Evans M, Gbolade B, Newton J, Pollard L, Szarewski A, et al. Depo Provera. Position paper on clinical use, effectiveness and side effects. Br J Fam Plann. 1999;25(2):69–76.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Curry L, Taylor L, Pallas SW, Cherlin E, Pérez-Escamilla R, Bradley EH. Scaling up depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA): A systematic literature review illustrating the AIDED model. Reprod Health. 2013;10:39.

Ahmed K, Baeten JM, Beksinska M, Bekker L-G, Bukusi EA, Donnell D, et al. HIV incidence among women using intramuscular depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, a copper intrauterine device, or a levonorgestrel implant for contraception: A randomised, multicentre, open-label trial. Lancet. 2019;0(0). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31288-7 .

Baumgartner JN, Morroni C, Mlobeli R, Otterness, Buga G, Chen M. Impact of a provider job aid intervention on injectable contraceptive continuation in South Africa. Stud Fam Plan. 2012;43(4):305–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00328.x .

Cetina TECD, Canto P, Luna MO. Effect of counseling to improve compliance in Mexican women receiving depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate. Contraception. 2001;63(3):143–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00181-0 .

Liu J, Shen J, Diamond-Smith N. Predictors of DMPA-SC continuation among urban Nigerian women: The influence of counseling quality and side effects. Contraception. 2018;98(5):430–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2018.04.015 .

Brunie A, Callahan RL, Godwin CL, Bajpai J, OlaOlorun FM. User preferences for a contraceptive microarray patch in India and Nigeria: Qualitative research on what women want. PLoS One. 2019;14(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216797 .

Tolley EE, McKenna K, Mackenzie C, Ngabo F, Munyambanza E, Arcara J, et al. Preferences for a potential longer-acting injectable contraceptive: Perspectives from women, providers, and policy makers in Kenya and Rwanda. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2(2):182–94. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00147 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the contributions of the data collection team and the local clinic personnel who helped to facilitate study entry. We are grateful to Bright Asare for provided assistance throughout the data collection period. At the Duke Global Health Institute, Mary Story and Randall Kramer were important advocates for the research.

This study was funded by a grant from Duke University’s Global Health Institute. Students of the funding body designed the study based on priorities identified by Ghanaian collaborators. The supplied funds were used to support data collection and management in Ghana. Analysis, interpretation, & writing were completed by the Duke students (LS and MS), in collaboration with the Ghanaian partners (NN, EA and SO), and with support from Duke faculty mentors (JB and MW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, Box 90519, Durham, NC, 27708, USA

Leah A. Schrumpf, Maya J. Stephens, Joy Noel Baumgartner & Melissa H. Watt

Millennium Promise Ghana, 14 Bathur St, East Legon, Accra, Ghana

Nathaniel E. Nsarko, Eric Akosah & Seth Ohemeng-Dapaah

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LAS was a co-principal investigator on the study, contributed to the design of the work, analyzed and interpreted data, and was the main contributor in the writing of the manuscript. MJS was a co-principal investigator in this study, contributed to the design of the work, and analyzed and interpreted the data. NEN made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. EA made contributions to the design of the work and data interpretation. JNB made contributions in the interpretation of the data and has substantively revised the manuscript. SO-D made contributions to the conception and design of the work. MHW made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, as well as data interpretation and revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Leah A. Schrumpf .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

All study procedures and materials were approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board (2018–0343) and Ghana Health Services Ethical Review Committee. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

The informed consent form included permission to include de-identified data in publications.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Schrumpf, L.A., Stephens, M.J., Nsarko, N.E. et al. Side effect concerns and their impact on women’s uptake of modern family planning methods in rural Ghana: a mixed methods study. BMC Women's Health 20 , 57 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-0885-0

Download citation

Received : 24 August 2019

Accepted : 15 January 2020

Published : 20 March 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-0885-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Family planning

- Contraceptives

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Unmet need for family planning in Ghana: the shifting contributions of lack of access and attitudinal resistance

Affiliation.

- 1 Research Fellow, Faculty of Epidemiology and Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, WC1E 7HT, UK. [email protected].

- PMID: 24931076

- DOI: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00385.x

In Ghana, despite a 38 percent decline in the total fertility rate from 1988 to 2008, unmet need for family planning among married women exposed to pregnancy risk declined only modestly in this period: from 50 percent to 42 percent. Examining data from the five DHS surveys conducted in Ghana during these years, we find that the relative contribution to unmet need of lack of access to contraceptive methods has diminished, whereas attitudinal resistance has grown. In 2008, 45 percent of women with unmet need experienced no apparent obstacles associated with access or attitude, 32 percent had access but an unfavorable attitude, and 23 percent had no access. Concerns regarding health as a reason for nonuse have been reported in greater numbers over these years and are now the dominant reason, followed by infrequent sex. An enduring resistance to hormonal methods, much of it based on prior experience of side effects, may lead many Ghanaian women, particularly the educated in urban areas, to use periodic abstinence or reduced coital frequency as an alternative to modern contraception.

© 2013 The Population Council, Inc.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Reasons for contraceptive nonuse among women having unmet need for contraception in developing countries. Sedgh G, Hussain R. Sedgh G, et al. Stud Fam Plann. 2014 Jun;45(2):151-69. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00382.x. Stud Fam Plann. 2014. PMID: 24931073

- Men's unmet need for family planning: implications for African fertility transitions. Ngom P. Ngom P. Stud Fam Plann. 1997 Sep;28(3):192-202. Stud Fam Plann. 1997. PMID: 9322335

- The causes of unmet need for contraception and the social content of services. Bongaarts J, Bruce J. Bongaarts J, et al. Stud Fam Plann. 1995 Mar-Apr;26(2):57-75. Stud Fam Plann. 1995. PMID: 7618196 Review.

- Estimating unmet need for contraception by district within Ghana: an application of small-area estimation techniques. Amoako Johnson F, Padmadas SS, Chandra H, Matthews Z, Madise NJ. Amoako Johnson F, et al. Popul Stud (Camb). 2012 Jul;66(2):105-22. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2012.678585. Epub 2012 May 4. Popul Stud (Camb). 2012. PMID: 22553978

- Meeting unmet need: new strategies. Robey B, Ross J, Bhushan I. Robey B, et al. Popul Rep J. 1996 Sep;(43):1-35. Popul Rep J. 1996. PMID: 8948001 Review.

- The impact of local supply of popular contraceptives on women's use of family planning: findings from performance-monitoring-for-action in seven sub-Saharan African countries. Kristiansen D, Boyle EH, Svec J. Kristiansen D, et al. Reprod Health. 2023 Nov 21;20(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s12978-023-01708-7. Reprod Health. 2023. PMID: 37990268 Free PMC article.

- Dynamic stagnation: reasons for contraceptive non-use in context of fertility stall. Jadhav A, Short Fabic M. Jadhav A, et al. Gates Open Res. 2019 May 7;3:1458. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.12990.1. eCollection 2019. Gates Open Res. 2019. PMID: 37795519 Free PMC article.

- Perspectives on the side effects of hormonal contraceptives among women of reproductive age in Kitwe district of Zambia: a qualitative explorative study. Mukanga B, Mwila N, Nyirenda HT, Daka V. Mukanga B, et al. BMC Womens Health. 2023 Aug 18;23(1):436. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02561-3. BMC Womens Health. 2023. PMID: 37596577 Free PMC article.

- Assessing the Suitability of Unmet Need as a Proxy for Access to Contraception and Desire to Use It. Senderowicz L, Bullington BW, Sawadogo N, Tumlinson K, Langer A, Soura A, Zabré P, Sié A. Senderowicz L, et al. Stud Fam Plann. 2023 Mar;54(1):231-250. doi: 10.1111/sifp.12233. Epub 2023 Feb 26. Stud Fam Plann. 2023. PMID: 36841972 Free PMC article.

- Measuring Contraceptive Autonomy at Two Sites in Burkina Faso: A First Attempt to Measure a Novel Family Planning Indicator. Senderowicz L, Bullington BW, Sawadogo N, Tumlinson K, Langer A, Soura A, Zabré P, Sié A. Senderowicz L, et al. Stud Fam Plann. 2023 Mar;54(1):201-230. doi: 10.1111/sifp.12224. Epub 2023 Feb 2. Stud Fam Plann. 2023. PMID: 36729070 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources, other literature sources.

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Fear, opposition, ambivalence, and omission: Results from a follow-up study on unmet need for family planning in Ghana

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Avenir Health, Glastonbury, Connecticut, United States of America, The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program, Rockville, Maryland, United States of America

- Sarah Staveteig

- Published: July 31, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076

- Reader Comments

Introduction

Despite a relatively strong family planning program and regionally modest levels of fertility, Ghana recorded one of the highest levels of unmet need for family planning on the African continent in 2008. Unmet need for family planning is a composite measure based on apparent contradictions between women’s reproductive preferences and practices. Women who want to space or limit births but are not using contraception are considered to have an unmet need for family planning. The study sought to understand the reasons behind high levels of unmet need for family planning in Ghana.

A mixed methods follow-up study was embedded within the stratified, two-stage cluster sample of the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS). Women in 13 survey clusters who were identified as having unmet need, along with a reference group of current family planning users, were approached to be reinterviewed within an average of three weeks from their GDHS interview. Follow-up respondents were asked a combination of closed- and open-ended questions about fertility preferences and contraceptive use. Closed-ended responses were compared against the original survey; transcripts were thematically coded and analyzed using qualitative analysis software.

Among fecund women identified by the 2014 GDHS as having unmet need, follow-up interviews revealed substantial underreporting of method use, particularly traditional methods. Complete postpartum abstinence was sometimes the intended method of family planning but was overlooked during questions about method use. Other respondents classified as having unmet need had ambivalent fertility preferences. In several cases, respondents expressed revised fertility preferences upon follow-up that would have made them ineligible for inclusion in the unmet need category. The reference group of family planning users also expressed unstable fertility preferences. Aversion to modern method use was generally more substantial than reported in the GDHS, particularly the risk of menstrual side effects, personal or partner opposition to family planning, and religious opposition to contraception.

Citation: Staveteig S (2017) Fear, opposition, ambivalence, and omission: Results from a follow-up study on unmet need for family planning in Ghana. PLoS ONE 12(7): e0182076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076

Editor: Ali Montazeri, Iranian Institute for Health Sciences Research, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN

Received: November 11, 2016; Accepted: July 12, 2017; Published: July 31, 2017

Copyright: © 2017 Sarah Staveteig. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Nationwide Demographic and Health Survey data are available for free upon registration with The Demographic and Health Surveys Program ( www.dhsprogram.com ). Per agreement with the ICF International Institutional Review Board, due to ethical concerns about re-identification of respondents, individual follow-up interview transcripts cannot be made publicly available.

Funding: This study was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program (#AIDOAA-C-13-00095). The funders had no role in data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Unmet need is a central concept in family planning research and a key indicator for gauging the demand for contraception and for measuring the success of programs and policies. At its most basic level, unmet need reflects an apparent discrepancy between women’s stated reproductive preferences and behavior. In surveys some women respond they want to space or limit births, but they are not using any method to prevent pregnancy. These respondents are considered to have unmet need for family planning, and are at risk of unintended pregnancy. Unintended pregnancies frequently lead to unsafe abortions or maternal complications and place the health of mothers and children at risk [ 1 ].

In 2012 there were estimated to be more than 74 million unintended pregnancies in the developing world, including 4.6 million in West Africa [ 2 ]. The global burden of unintended pregnancy includes not only health of mothers and their children, but also costs for health care systems, social costs, and economic well-being of families worldwide. Family planning provides women and families the opportunity to plan and space births in line with their own reproductive preferences, helping to ensure the safety and well-being of both mother and children. Monitoring unmet need has taken on increased emphasis in recent years as policymakers seek to help women and couples achieve their reproductive goals. Reducing unmet need was part of the Millennium Development Goals. An indicator derived from unmet need, demand satisfied for modern contraception—computed as modern contraceptive prevalence divided by the sum of unmet need for modern contraceptive methods and modern contraceptive prevalence—is an indicator for the Sustainable Development Goals and a central part of new efforts by USAID and several donors to scale up family planning for millions of women as part of FP2020 [ 3 ].

The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program, the largest source of data on contraceptive patterns and unmet need in developing countries, conducts nationally representative surveys during which interviewers ask women questions about sexual activity, fertility preferences, fecundity, contraceptive use, and other topics. DHS and other nationally representative surveys, such as Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and Performance Monitoring and Accountability 2020 (PMA 2020), compute unmet need for family planning based on a complex algorithm involving women’s responses to 18 questions asked at various points throughout the interview [ 4 ]. Married women, and in some cases sexually active unmarried women, who are fecund and wish to postpone giving birth for two or more years or stop childbearing altogether but who are not using any method of family planning are classified as having unmet need. Additionally, women who are pregnant or postpartum amenorrheic with an unwanted or mistimed pregnancy are considered to have an unmet need for family planning.

Specifically, women are considered to have unmet need if they are in any of the following three categories: (1) at risk of becoming pregnant, not using contraception, and want no more children, or want children but do not want to become pregnant within the next two years, or are unsure if or when they want to become pregnant; (2) pregnant with a mistimed or unwanted pregnancy; or (3) postpartum amenorrheic for up to two years following an unwanted or mistimed birth and not using contraception [ 4 ]. The calculation of unmet need does not involve direct questions about women’s own contraceptive preferences and proclivities; as such, it is described as a measure of latent or potential demand for family planning [ 5 , 6 ].

Relatively few women with an unmet need for family planning in developing countries cite cost or access as reasons for not using a contraceptive method [ 7 ]. Instead, survey respondents tend to cite fear of side effects, abstinence, breastfeeding, and attitudinal factors. The explanations underlying these stated reasons are not well understood.

The mixed methods follow-up study described in the present article leveraged the existing sampling structure and data collection within the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS) to provide additional insights into reproductive preferences and barriers to family planning among women in Ghana with unmet need. The primary objective of the follow-up study was to better understand the lived experience and meanings underlying the apparent contradiction in fertility preferences and reproductive behavior that produce statistical estimates of unmet need in the DHS surveys. Do the survey questions about current family planning use and reproductive preferences retain their intended meaning in the field? How stable and well defined are women’s fertility preferences, and how do women explain their non-use of family planning? The study compares respondents classified as having unmet need with a reference group of respondents who were using family planning at the time of the survey.

Open-ended, qualitative questions can provide substantial insight into ambivalence, perceptions, and attitudes not readily apparent from large-scale survey data. Qualitative and mixed methods studies are well positioned to provide important insights about demographic behaviors [ 8 , 9 ] and are particularly relevant to understanding the meanings that respondents attach to responses in large-scale surveys such as the DHS [ 10 ].

The concept of unmet need

The development of the concept of unmet need is rooted in the KAP (Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice) surveys of the 1960s. Researchers identified married women whose preferences and behavior appeared contradictory—that is, they wanted to limit or space childbearing but were not using a method of family planning [ 11 ]. The KAP surveys gave way to the World Fertility Survey program in the 1970s and 1980s and ultimately evolved into the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program which covered a wider range of topics, starting in 1984. The algorithm for determining unmet need grew increasingly complex over time as questions on fertility preferences evolved and data from the contraceptive calendar were included when available. In 2012, a simplified, consensus DHS/MICS definition of unmet need was established using a standard algorithm [ 4 ]. A comprehensive history of unmet need and evolution of the classification schema has been detailed by other authors [ 12 – 14 ].

One concern with the concept of unmet need is that the term itself implies a demand for family planning—and, in fact, is summed with contraceptive prevalence to compute an indicator called “demand for family planning”—but the term does not necessarily reflect actual or potential interest in method use. In particular, it does not reflect how women themselves perceive their risk of pregnancy, the strength of their preferences, or their interest in or resistance to family planning. Additional concerns about the measurement of unmet need include the failure to differentiate married women who are sexually active from those who are not, and thus at no risk of pregnancy [ 12 ], the failure to include male partners [ 15 , 16 ], and instability in professed fertility preferences [ 17 – 20 ].

The extent to which survey measures of unmet need gauge latent demand for family planning has been questioned due to the temporal instability of the measure and the number of different groups it encompasses [ 21 ]. Even in the early days of the development of unmet need as a measure of demand for family planning, it was known that in some countries less than half of women with unmet need were currently at risk of pregnancy [ 14 ]; unmet need classification depends on prospective fertility preferences as well as on ex-post facto assessments of the intendedness of pregnancies and recent births. A technical working group for FP2020 opted against using reductions in levels of unmet need as a global goal because it is not a unidirectional measure of programmatic success [ 22 ].

Despite concerns about its measurement and interpretation, unmet need is a powerful concept. Abortions, surreptitious use of family planning, and unwanted pregnancies all attest to an ongoing need for family planning that is unfulfilled [ 23 ]. How to assess women’s ‘need’ or demand for family planning has proven difficult, however. In particular, evidence indicates that—even among survey respondents whose fertility operates within the “calculus of conscious choice”—the answers to prospective fertility preference questions are fraught with ambiguity and uncertainty [ 17 , 19 ]. Measures of unmet need depend on women’s tendency to plan and articulate fertility preferences in a two-year window. Fertility preferences are subject to both social context [ 5 ] and to vital conjunctures in women’s lives [ 24 ], including husband’s desire for children [ 16 , 25 ], future economic well-being, marital stability, and survival of current children. Longitudinal evidence finds substantial instability in individual women’s fertility preferences over time [ 26 – 28 ].

Study context

At the time this study was being designed, Ghana had recorded one of the highest levels of unmet need for family planning among married women on the African continent, at 36 percent in 2008 [ 29 ]. Family planning use had declined slightly among married women, from 25 percent in 2003 to 24 percent in 2008. Meanwhile, Ghana’s Total Fertility Rate (TFR) in 2008 was among the lowest in West Africa, at 4.0 births per woman. Unmet need is typically only measured among currently married women, but the focus of this study is currently married and sexually active women combined, as both groups of women are at risk of unwanted pregnancies. Nationwide, 29 percent of married and sexually active unmarried women in Ghana had an unmet need for family planning as measured by data from the 2014 GDHS.

Ghana’s attainment of regionally low fertility despite modest levels of family planning use has been a demographic puzzle for nearly two decades [ 30 ]. Abortion is legal in Ghana and has been hypothesized as a reason for lower-than-expected fertility [ 31 ]; but evidence has been inconclusive. It may be that high levels of unmet need in Ghana partly reflected women’s growing tendency to articulate a need for spacing or limiting births. During early stages of the demographic transition, the percentage of women with unmet need can increase even as demand for family planning is being satisfied simply due to women’s increased interest in reducing fertility [ 32 ].

Ghana has a relatively strong family planning program. The contraceptive method mix is diverse. Injectables, the pill, and implants are the most common methods, followed by the rhythm method. Women can obtain contraception from public and private sources. Family planning is inexpensive but not free. Ghana does experience occasional contraceptive supply issues and there are some limits to the method mix offered. Social marketing campaigns have proven successful but some very remote areas of the country remain a few hours’ distance from the nearest clinic. Even so, in surveys women rarely cite access and cost as reasons for non-use of family planning [ 33 ].

By 2014 the TFR increased slightly, to 4.2 births per woman [ 34 ]. The 2014 GDHS also found an increase in modern contraceptive prevalence since 2008 (from 17 to 22 percent) and a decline in unmet need (from 36 to 30 percent) among married women ages 15–49. This brings the country on par with levels of unmet need in neighboring West African countries, but still high in a global perspective.

Perceptions about side effects and attitudinal factors pose a challenge to increased family planning use in Ghana. Focus group discussions from a hospital in Ghana found women’s concern with menstrual regularity results in dissatisfaction with family planning methods that prevent menstruation [ 35 ]. Another study found that many Ghanaian women perceive family planning as ineffective or unsafe [ 36 ], and DHS data from 1988 to 2008 show that attitudinal resistance has been an increasing component of unmet need in Ghana [ 33 ]. Male attitudes toward contraception are mixed: in the 2014 GDHS, 73 percent of men age 15–59 rejected the idea that contraception is a woman’s business and men should not have to be involved, but 46 percent supported the statement that women who use contraception may become promiscuous [ 34 ]. Married Ghanaian women’s sexual empowerment is a statistically significant predictor of contraceptive use, even after controlling for other factors [ 37 ].

This study was designed as a data-linked embedded follow-up study, of the type described by Schatz [ 38 , 39 ]. It was independently funded, planned, and fielded, but respondents were systematically selected from among the respondents to the 2014 GDHS. The 2014 GDHS is a nationally representative household survey in which 9,396 women age 15–49 were interviewed [ 34 ]. Fieldwork for the GDHS was conducted by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and the Ghana Health Service (GHS), with technical assistance from ICF International through The DHS Program, which is funded by USAID. At the end of the GDHS, all 9,396 female respondents were asked for consent to be re-contacted for a follow-up study on family planning. Nationwide, 99.6 percent of women agreed to be re-contacted.

The follow-up study selected three of ten regions for follow-up: Greater Accra, the capital, Central Region, and Northern Region. Central Region had the highest level of unmet need in 2008 and Northern Region has typically had higher fertility and low family planning use. In all, 13 survey clusters were selected for follow-up fieldwork five in Northern Region, five in Central Region, and three in Greater Accra, the region with the lowest fertility. It was decided in advance that all three clusters selected in Greater Accra would be urban, and that one of the five clusters in Central Region and in Northern Region would be urban. A completely random selection of clusters from the parent survey would not have been feasible. Fieldwork for the GDHS takes four months, versus one month for the follow-up study, and it was desirable to return within three weeks. Additionally, for a small-scale study the distances might have been prohibitive. Thus cluster selection was based on those available at the time of the study, with an eye toward geographic diversity. However, within a given cluster women were selected systematically, from among those surveyed in a stratified random sample rather than a convenience sample typical for qualitative studies.

Fieldwork for the follow-up study was conducted by the Institute for Statistical, Social, and Economic Research (ISSER) at the University of Ghana, Legon. Preparation for interviews began with an 11-day training and pretest in Accra. Along with a guide from GSS, three field teams each consisting of two interviewers and a field supervisor attempted to relocate the selected DHS respondents within three weeks of the original survey. Interviewers returned up to three times to complete the interview. Interviews were randomly audited to ensure that they were correctly completed. Follow-up interviews were conducted anywhere from 5 to 60 days after the GDHS interview; on average women were reinterviewed 20 days after their GDHS interview. Survey procedures are described in detail elsewhere [ 40 , 41 ].

The overall response rate was 92.3 percent (131 of 142 women selected). Of these 131 respondents, 96 qualified for analysis. Fig 1 shows detailed sample selection criteria. This article analyzes 96 respondents, the 50 women who were classified by the GDHS as having an unmet need for family planning, alongside a reference group of 46 women who were identified as having a met need for family planning.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076.g001

Respondents to the follow-up survey were located by address, name of household head, and relationship to the household head; to verify their identity, respondents were asked six additional questions: year of birth, month of birth, marital status, whether ever given birth, number of resident sons, and number of resident daughters. The vast majority of respondents matched on all or all but one characteristic. The 96 cases discussed here reflect confident—but imperfect—identity matching. Prior studies have found inconsistent results on key questions, even with the exact same survey conducted after only a short delay [ 42 , 43 ]. Discrepancies in responses were flagged so that interviewers could inquire further.

Follow-up interviews were conducted using Android tablets to import respondent data and guide questions; audio recorders were used to capture women’s full responses to each question. Questionnaires were translated into three languages—Twi, Ga, and Hausa. The semi-structured questionnaires included a combination of closed and open-ended questions about reproductive preferences, ambivalence, decision-making, and family planning (see S1 File ). Respondents were also asked open-ended questions about fertility desires, family planning use, attitudes toward family planning, role of partner and extended family in decision-making, and barriers to access.

After fieldwork was complete, audio files from the interviews were transcribed into the language of the interview and subsequently translated into English, resulting in over 1,000 single-spaced pages of transcripts. Transcripts were input into ATLAS.ti qualitative analysis software. A number of themes were established and listed at the start, based on the questionnaire, while additional themes were added inductively by iteratively reading transcripts. A list of themes was developed, refined, and independently applied to a set of test transcripts by two raters to compare reliability. After finalizing the schema, the themes were consistently applied to the transcripts in ATLAS.ti. Variables created directly from tablet entry information were reviewed for missing and inconsistent values and, when possible, filled in or manually verified against transcripts. These data were confidentially linked to publicly available GDHS records and analyzed using Stata.

Ethical considerations

The ICF International Institutional Review Board (IRB), which requires compliance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects (45 CFR 46), reviewed and approved all study procedures and questionnaires. A waiver of written consent was obtained from the IRB due to minimal risk of harm and a lack of procedures for which written consent is normally required. Respondents were asked for verbal consent to be re-contacted during the main survey and for verbal consent to be interviewed and to be audiotaped at the start of the follow-up interview. Before the interview began interviewers were required to provide their electronic signature attesting that they had received verbal consent from the respondent to be interviewed and that they had correctly indicated whether the respondent consented to be audiotaped.

In keeping with IRB regulations and The DHS Program’s practices, the confidentiality of the respondent’s information was maintained at all stages of the survey. Recordkeeping used anonymous cluster and respondent identifiers. As voluntary HIV serotesting was conducted during the 2014 Ghana DHS, no data entry on names or addresses was done and all cluster and household numbers were scrambled prior to linkage with HIV test results. Similarly, at the conclusion of fieldwork the implementing agency for the follow-up study destroyed all identifying information used to contact respondents, maintaining only an anonymized identification number. A linkage between the anonymized identification number for the follow-up study and the final, publicly available dataset is kept only by The DHS Program.

Sample characteristics

The 96 married and sexually active unmarried women analyzed in this article were systematically selected from among GDHS respondents. The follow-up sample was intended to be diverse, but given the scale of the study, the sample was not designed to be perfectly representative of the three regions. Table 1 indicates how the characteristics of the sample as defined in the GDHS compared with family planning users and with women who had an unmet need in the three selected regions. GDHS sample weights are applied to regional percentages and to the sub-study respondents. Table 1 shows that respondents to the follow-up study were more concentrated in their 30s than their respective regional counterparts. Fewer follow-up respondents were age 15–19. Follow-up respondents were more predominantly rural than both family planning users and women with unmet need in the country as a whole.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076.t001

Women who reported using family planning in the GDHS were more highly educated and wealthier than women with unmet need. Both follow-up samples were over-representative of the lowest wealth quintile than the regional averages. The follow-up sample exhibited religious diversity, but was more heavily traditional/spiritualist and no stated religion than women nationwide in both the unmet need and family planning groups. One of the clusters in the North was Konkomba-speaking, and respondents were ethnically Gurma; the follow-up study sample was thus much more heavily comprised of Gurma women than the country as a whole.

Reproductive characteristics of the four groups (regional and follow-up respondents who were family planning users and who had unmet need in the GDHS) are shown in Table 2 . Women’s knowledge of family planning methods is high in Ghana. Nationwide, over 99 percent of women with unmet need know at least one modern method. In the follow-up survey, one respondent was identified by the GDHS as not knowing any method of family planning, another as only knowing traditional methods. The majority of women with unmet need have used a family planning method before.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076.t002

Fertility preferences

Fertility preferences are a pivotal component of unmet need. Among fecund women, declared intention to have a/another birth and the preferred timing of the next birth determine unmet need status. The two questions on reproductive preferences used to compute unmet need for this group are: (1) “ Would you like to have (a/another) child , or would you prefer not to have any (more) children ? ” Allowable responses to this question are: (a) want a/another; (b) no more; (c) cannot get pregnant; (d) a special condition, such as ‘after marriage’; or (e) don’t know/undecided. Non-pregnant respondents who want a/another child are then asked: (2) “How long would you like to wait from now before the birth of (a/another) child ? ” Pregnant women are asked: “After the child you are expecting now , would you like to have another child , or would you prefer not to have any more children ? ” The answer must either be a specific number of years and months, a special wait condition, or undecided. While the questions used to ascertain fertility preferences are seemingly straightforward, women’s ability and willingness to articulate a fixed timeline for their preferred time to next birth are culturally and temporally variable.

Non-pregnant respondents who want no more children and meet criteria for fecundity and non-use are considered to have an unmet need for limiting. The consensus definition of unmet need uses a threshold of two or more years to determine whether women have an unmet need for spacing. A comparison between responses to the question from the GDHS and the follow-up survey are shown in Table 3 . As the table indicates, 18 percent of follow-up respondents with unmet need and 13 percent of follow-up family planning users gave inconsistent answers to this question between surveys. The shift in responses occurred largely among women who stated they were undecided in the GDHS but said they wanted another child upon follow-up. There was some additional negligible movement in both directions between wanting no more children and wanting another child during the follow-up.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076.t003

The main ambivalence in fertility preferences that emerged through interviews was not whether to have another child, but the timing of that preference. In the GDHS, responses to question about desired timing of the next birth were limited to a single number of months or years, or to a special wait condition. In the follow-up survey women were allowed to specify an open range of desired time until the next birth. Responses to this question, grouped by minimum wait time into one-year intervals, are shown in Table 4 for follow-up respondents with unmet need. Figures include the eight respondents who said in the GDHS that they were undecided or that they wanted no more children but declared in the follow-up survey that they wanted a/another. Twenty of 31 respondents indicated a desire to wait until a single point in time, while the remainder gave a time range, averaging 23 months.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076.t004

Of the respondents classified as having unmet need who indicated in the follow-up interview that they wanted a/another birth, 11 declared in follow-up a minimum desired waiting time of less than two years. For seven of these 11 respondents, two years encompassed both the minimum and maximum waiting time, which would have classified them as having no unmet need. The other four respondents gave a range of time that started before two years. If they had been asked to give a fixed number and settled on less than two years, they would also have been excluded from the group defined as having unmet need.

The follow-up survey also asked women the strength of their desire to wait that long for the next birth. Results are shown in Table 4 . Desires to delay were weakest among women who expressed a preference to wait one to three years; they tended to be strongest at the highest and lowest time boundaries.

A main theme that emerged from the discussion of fertility preferences overall was that respondents felt torn between joy versus means—or in many cases torn between the potential future value of a child (who could be the “star of the family”) versus the immediate cost of raising a child. Respondents and their partners valued children highly, but most respondents perceived an inherent trade-off between the value of another child and the financial or health costs of too many or closely spaced births. For example, as a 35-year old woman in urban Central Region (R03.08) described:

Well, it would be good to have another child, and it would be especially good to have a safe delivery. Even the Bible tells us that children are a blessing and a gift from God, so if I have another child and am able to take care of him or her such that he grows to become responsible and respectable person, it would even bring honor to me. People would point at him and say, oh there goes Sister [Name]’s son, and that would bring me fulfillment and joy… I do not know how far the child might go in life; he might even be an important personality and bring honor to our family, so that could be a value that having lots of children might bring us… Even if you look at the Bible, it says to be fruitful and multiply and to replenish the earth, it’s out of many children that some grow to be important personalities of the world but it’s due to economic and financial hardships that people face that’s why they may decide to have fewer children but ideally, you should have more, you never know which of your children would be of significance someday .

Respondents frequently indicated that they would accept an unwanted pregnancy but would not be happy. “ I don’t like it but if it comes I will accept it” or “ I will not be happy but once it has come I will accept it” was how seven respondents (R01.01, R01.03, R01.05, R02.03, R02.07, R04.02, R05.07) described their attitude toward having another child. “I will be disturbed but I will be happy to have a child” said another (R01.07).

For the 11 respondents identified as having an unmet need whose timing shifted below the two-year threshold, including those who had originally said no more, two themes emerged. First was an overall ambivalence toward pregnancy, not simply conflicted feelings but also a sense of fatalism. The majority of women in this category were in rural areas and had parity of four or more. The second theme that emerged was that the respondent had a partner who would be happy or very happy about another birth while the respondent herself did not feel strongly. For example, one 40-year old rural respondent in the Northern Region with seven children (R13.02) who changed from wanting no more children to wanting a child now indicated the decision was her own, but that she was deferential to her husband’s preference.

I know [my husband] likes children even though we have nothing. Take a look at my house, we don’t have strength but we are managing with life… We talk all the time. He said we are going through a tough time but do we still want more children or we should try a method? And I said whatever you decide I have no problem with it… I would like to have another child any moment from now .

In sum, 41 of 50 respondents with unmet need consistently answered the question about desirability of a/another child in the GDHS and the follow-up. The main source of inconsistency was movement from undecided to wanting another child. Including respondents who changed from wanting no more children to wanting a/another child, there were 11 cases where the stated time to next birth moved into the two-year range, seven of which (14% of unmet need sample) would have meant that women were not classified as having unmet need.

Discrepancies in reporting of method use

At the beginning of the follow-up survey, after questions to confirm key identifying characteristics, non-pregnant women were asked if they were currently using family planning. The wording of the question was the same as in the DHS (“Are you currently doing something or using a method to delay or avoid getting pregnant ? ”) . Unlike in the DHS, however, women who responded “no” were prompted about natural methods (“What about the rhythm/calendar method ? What about withdrawal ? ”) .

A comparison of method use reported in the GDHS and the follow-up survey is shown in Table 5 . Out of 44 non-pregnant respondents that the GDHS determined to have unmet need for family planning, 15 (34 percent) reported in the follow-up interview that they actually were using a method of family planning. Five reported using a modern method, nine reported a traditional method, and one reported both. Additionally, three respondents who said they were using a method in the GDHS reported not using a method in the follow-up study.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182076.t005

Respondents who reported discrepant use of a method in the GDHS and the follow-up survey were closely examined for identity verification questions and checked against other women in the household to see whether the follow-up interview may have been conducted with the wrong household member. None of the GDHS respondents with unmet need who reported using a method at the time of follow-up lived in a household with another woman who used a method. All matched on at least seven of nine pieces of identifying information.

Some of the women may have started or stopped a method in the intervening days between interviews. In cases where women were asked about the discrepancy, none reported starting between interviews. Two users of modern methods said that they were using a method and had told the GDHS interviewers but it was not recorded. The DHS question on method use is specifically intended to be inclusive of traditional methods (“doing something or using a method to prevent pregnancy” ) and in the DHS interview, immediately prior to the question on current method use, respondents are asked whether they have heard of a list of methods, including rhythm or calendar, withdrawal, and lactational amenorrhea. They are read a brief description of each method type. But the main theme that emerged among respondents who reported natural methods was that they misinterpreted the GDHS question about method use as being about modern methods. For example, here is an exchange with a 26-year old woman in an urban part of Central Region (R05.06):

Interviewer: I’d like to begin by confirming the information I received . Are you currently doing something or using any method to delay or avoid getting pregnant ? Respondent: No , I am not on any medication . Interviewer: Yes , I understand you may not be on any medication to prevent pregnancy but there are other ways of preventing pregnancy such as the rhythm or withdrawal methods . Are you currently using any of these to prevent pregnancy ? Respondent: Oh , yes , I didn’t understand at first . I use the withdrawal method . Interviewer: Please according to the information I have from the previous interviewer , you are currently not using any method or means to prevent pregnancy . Is that information correct ? Respondent: Yes , it is . When they came they only asked about the modern methods of family planning . They didn’t ask about the rhythm and the withdrawal like you did . That is why I said no but my husband and I use the withdrawal .