- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- Science Experiments for Kids

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Understanding Peer Review in Science

Peer review is an essential element of the scientific publishing process that helps ensure that research articles are evaluated, critiqued, and improved before release into the academic community. Take a look at the significance of peer review in scientific publications, the typical steps of the process, and and how to approach peer review if you are asked to assess a manuscript.

What Is Peer Review?

Peer review is the evaluation of work by peers, who are people with comparable experience and competency. Peers assess each others’ work in educational settings, in professional settings, and in the publishing world. The goal of peer review is improving quality, defining and maintaining standards, and helping people learn from one another.

In the context of scientific publication, peer review helps editors determine which submissions merit publication and improves the quality of manuscripts prior to their final release.

Types of Peer Review for Manuscripts

There are three main types of peer review:

- Single-blind review: The reviewers know the identities of the authors, but the authors do not know the identities of the reviewers.

- Double-blind review: Both the authors and reviewers remain anonymous to each other.

- Open peer review: The identities of both the authors and reviewers are disclosed, promoting transparency and collaboration.

There are advantages and disadvantages of each method. Anonymous reviews reduce bias but reduce collaboration, while open reviews are more transparent, but increase bias.

Key Elements of Peer Review

Proper selection of a peer group improves the outcome of the process:

- Expertise : Reviewers should possess adequate knowledge and experience in the relevant field to provide constructive feedback.

- Objectivity : Reviewers assess the manuscript impartially and without personal bias.

- Confidentiality : The peer review process maintains confidentiality to protect intellectual property and encourage honest feedback.

- Timeliness : Reviewers provide feedback within a reasonable timeframe to ensure timely publication.

Steps of the Peer Review Process

The typical peer review process for scientific publications involves the following steps:

- Submission : Authors submit their manuscript to a journal that aligns with their research topic.

- Editorial assessment : The journal editor examines the manuscript and determines whether or not it is suitable for publication. If it is not, the manuscript is rejected.

- Peer review : If it is suitable, the editor sends the article to peer reviewers who are experts in the relevant field.

- Reviewer feedback : Reviewers provide feedback, critique, and suggestions for improvement.

- Revision and resubmission : Authors address the feedback and make necessary revisions before resubmitting the manuscript.

- Final decision : The editor makes a final decision on whether to accept or reject the manuscript based on the revised version and reviewer comments.

- Publication : If accepted, the manuscript undergoes copyediting and formatting before being published in the journal.

Pros and Cons

While the goal of peer review is improving the quality of published research, the process isn’t without its drawbacks.

- Quality assurance : Peer review helps ensure the quality and reliability of published research.

- Error detection : The process identifies errors and flaws that the authors may have overlooked.

- Credibility : The scientific community generally considers peer-reviewed articles to be more credible.

- Professional development : Reviewers can learn from the work of others and enhance their own knowledge and understanding.

- Time-consuming : The peer review process can be lengthy, delaying the publication of potentially valuable research.

- Bias : Personal biases of reviews impact their evaluation of the manuscript.

- Inconsistency : Different reviewers may provide conflicting feedback, making it challenging for authors to address all concerns.

- Limited effectiveness : Peer review does not always detect significant errors or misconduct.

- Poaching : Some reviewers take an idea from a submission and gain publication before the authors of the original research.

Steps for Conducting Peer Review of an Article

Generally, an editor provides guidance when you are asked to provide peer review of a manuscript. Here are typical steps of the process.

- Accept the right assignment: Accept invitations to review articles that align with your area of expertise to ensure you can provide well-informed feedback.

- Manage your time: Allocate sufficient time to thoroughly read and evaluate the manuscript, while adhering to the journal’s deadline for providing feedback.

- Read the manuscript multiple times: First, read the manuscript for an overall understanding of the research. Then, read it more closely to assess the details, methodology, results, and conclusions.

- Evaluate the structure and organization: Check if the manuscript follows the journal’s guidelines and is structured logically, with clear headings, subheadings, and a coherent flow of information.

- Assess the quality of the research: Evaluate the research question, study design, methodology, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Consider whether the methods are appropriate, the results are valid, and the conclusions are supported by the data.

- Examine the originality and relevance: Determine if the research offers new insights, builds on existing knowledge, and is relevant to the field.

- Check for clarity and consistency: Review the manuscript for clarity of writing, consistent terminology, and proper formatting of figures, tables, and references.

- Identify ethical issues: Look for potential ethical concerns, such as plagiarism, data fabrication, or conflicts of interest.

- Provide constructive feedback: Offer specific, actionable, and objective suggestions for improvement, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the manuscript. Don’t be mean.

- Organize your review: Structure your review with an overview of your evaluation, followed by detailed comments and suggestions organized by section (e.g., introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion).

- Be professional and respectful: Maintain a respectful tone in your feedback, avoiding personal criticism or derogatory language.

- Proofread your review: Before submitting your review, proofread it for typos, grammar, and clarity.

- Couzin-Frankel J (September 2013). “Biomedical publishing. Secretive and subjective, peer review proves resistant to study”. Science . 341 (6152): 1331. doi: 10.1126/science.341.6152.1331

- Lee, Carole J.; Sugimoto, Cassidy R.; Zhang, Guo; Cronin, Blaise (2013). “Bias in peer review”. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 64 (1): 2–17. doi: 10.1002/asi.22784

- Slavov, Nikolai (2015). “Making the most of peer review”. eLife . 4: e12708. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12708

- Spier, Ray (2002). “The history of the peer-review process”. Trends in Biotechnology . 20 (8): 357–8. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)01985-6

- Squazzoni, Flaminio; Brezis, Elise; Marušić, Ana (2017). “Scientometrics of peer review”. Scientometrics . 113 (1): 501–502. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2518-4

Related Posts

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 12 November 2021

Demystifying the process of scholarly peer-review: an autoethnographic investigation of feedback literacy of two award-winning peer reviewers

- Sin Wang Chong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4519-0544 1 &

- Shannon Mason 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 266 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3249 Accesses

8 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

A Correction to this article was published on 26 November 2021

This article has been updated

Peer reviewers serve a vital role in assessing the value of published scholarship and improving the quality of submitted manuscripts. To provide more appropriate and systematic support to peer reviewers, especially those new to the role, this study documents the feedback practices and experiences of two award-winning peer reviewers in the field of education. Adopting a conceptual framework of feedback literacy and an autoethnographic-ecological lens, findings shed light on how the two authors design opportunities for feedback uptake, navigate responsibilities, reflect on their feedback experiences, and understand journal standards. Informed by ecological systems theory, the reflective narratives reveal how they unravel the five layers of contextual influences on their feedback practices as peer reviewers (micro, meso, exo, macro, chrono). Implications related to peer reviewer support are discussed and future research directions are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

The transformative power of values-enacted scholarship

What matters in the cultivation of student feedback literacy: exploring university efl teachers’ perceptions and practices, why english exploring chinese early career returnee academics’ motivations for writing and publishing in english, introduction.

The peer-review process is the longstanding method by which research quality is assured. On the one hand, it aims to assess the quality of a manuscript, with the desired outcome being (in theory if not always in practice) that only research that has been conducted according to methodological and ethical principles be published in reputable journals and other dissemination outlets (Starck, 2017 ). On the other hand, it is seen as an opportunity to improve the quality of manuscripts, as peers identify errors and areas of weakness, and offer suggestions for improvement (Kelly et al., 2014 ). Whether or not peer review is actually successful in these areas is open to considerable debate, but in any case it is the “critical juncture where scientific work is accepted for publication or rejected” (Heesen and Bright, 2020 , p. 2). In contemporary academia, where higher education systems across the world are contending with decreasing levels of public funding, there is increasing pressure on researchers to be ‘productive’, which is largely measured by the number of papers published, and of funding grants awarded (Kandiko, 2010 ), both of which involve peer review.

Researchers are generally invited to review manuscripts once they have established themselves in their disciplinary field through publication of their own research. This means that for early career researchers (ECRs), their first exposure to the peer-review process is generally as an author. These early experiences influence the ways ECRs themselves conduct peer review. However, negative experiences can have a profound and lasting impact on researchers’ professional identity. This appears to be particularly true when feedback is perceived to be unfair, with feedback tone largely shaping author experience (Horn, 2016 ). In most fields, reviewers remain anonymous to ensure freedom to give honest and critical feedback, although there are concerns that a lack of accountability can result in ‘bad’ and ‘rude’ reviews (Mavrogenis et al., 2020 ). Such reviews can negatively impact all researchers, but disproportionately impact underrepresented researchers (Silbiger and Stubler, 2019 ). Regardless of career phase, no one is served well by unprofessional reviews, which contribute to the ongoing problem of bullying and toxicity prevalent in academia, with serious implications on the health and well-being of researchers (Keashly and Neuman, 2010 ).

Because of its position as the central process through which research is vetted and refined, peer review should play a similarly central role in researcher training, although it rarely features. In surveying almost 3000 researchers, Warne ( 2016 ) found that support for reviewers was mostly received “in the form of journal guidelines or informally as advice from supervisors or colleagues” (p. 41), with very few engaging in formal training. Among more than 1600 reviewers of 41 nursing journals, only one third received any form of support (Freda et al., 2009 ), with participants across both of these studies calling for further training. In light of the lack of widespread formal training, most researchers learn ‘on the job’, and little is known about how researchers develop their knowledge and skills in providing effective assessment feedback to their peers. In this study, we undertake such an investigation, by drawing on our first-hand experiences. Through a collaborative and reflective process, we look to identify the forms and forces of our feedback literacy development, and seek to answer specifically the following research questions:

What are the exhibited features of peer reviewer feedback literacy?

What are the forces at work that affect the development of feedback literacy?

Literature review

Conceptualisation of feedback literacy.

The notion of feedback literacy originates from the research base of new literacy studies, which examines ‘literacies’ from a sociocultural perspective (Gee, 1999 ; Street, 1997 ). In the educational context, one of the most notable types of literacy is assessment literacy (Stiggins, 1999 ). Traditionally, assessment literacy is perceived as one of the indispensable qualities of a successful educator, which refers to the skills and knowledge for teachers “to deal with the new world of assessment” (Fulcher, 2012 , p. 115). Following this line of teacher-oriented assessment literacy, recent attempts have been made to develop more subject-specific assessment literacy constructs (e.g., Levi and Inbar-Lourie, 2019 ). Given the rise of student-centred approaches and formative assessment in higher education, researchers began to make the case for students to be ‘assessment literate’; comprising of such knowledge and skills as understanding of assessment standards, the relationship between assessment and learning, peer assessment, and self-assessment skills (Price et al., 2012 ). Feedback literacy, as argued by Winstone and Carless ( 2019 ), is essentially a subset of assessment literacy because “part of learning through assessment is using feedback to calibrate evaluative judgement” (p. 24). The notion of feedback literacy was first extensively discussed by Sutton ( 2012 ) and more recently by Carless and Boud ( 2018 ). Focusing on students’ feedback literacy, Sutton ( 2012 ) conceptualised feedback literacy as a three-dimensional construct—an epistemological dimension (what do I know about feedback?), an ontological dimension (How capable am I to understand feedback?), and a practical dimension (How can I engage with feedback?). In close alignment with Sutton’s construct, the seminal conceptual paper by Carless and Boud ( 2018 ) further illustrated the four distinctive abilities of feedback literate students: the abilities to (1) understand the formative role of feedback, (2) make informed and accurate evaluative judgement against standards, (3) manage emotions especially in the face of critical and harsh feedback, and (4) take action based on feedback. Since the publication of Carless and Boud ( 2018 ), student and teacher feedback literacy has been in the limelight of assessment research in higher education (e.g., Chong 2021b ; Carless and Winstone 2020 ). These conceptual contributions expand the notion of feedback literacy to consider not only the manifestations of various forms of effective student engagement with feedback but also the confluence of contexts and individual differences of students in developing students’ feedback literacy by drawing upon various theoretical perspectives (e.g., ecological systems theory; sociomaterial perspective) and disciplines (e.g., business and human resource management). Others address practicalities of feedback literacy; for example, how teachers and students can work in synergy to develop feedback literacy (Carless and Winstone, 2020 ) and ways to maximise student engagement with feedback at a curricular level (Malecka et al., 2020). In addition to conceptualisation, advancement of the notion of feedback literacy is evident in the recent proliferation of primary studies. The majority of these studies are conducted in the field of higher education, focusing mostly on student feedback literacy in classrooms (e.g., Molloy et al., 2019 ; Winstone et al., 2019 ) and in the workplace (Noble et al., 2020 ), with a handful focused on teacher feedback literacy (e.g., Xu and Carless 2016 ). Some studies focusing on student feedback literacy adopt a qualitative case study research design to delve into individual students’ experience of engaging with various forms of feedback. For example, Han and Xu ( 2019 ) analysed the profiles of feedback literacy of two Chinese undergraduate students. Findings uncovered students’ resistance to engagement with feedback, which relates to the misalignment between the cognitive, social, and affective components of individual students’ feedback literacy profiles. Others reported interventions designed to facilitate students’ uptake of feedback, focusing on their effectiveness and students’ perceptions. Specifically, affordances and constraints of educational technology such as electronic feedback portfolio (Chong, 2019 ; Winstone et al., 2019 ) are investigated. Of particular interest is a recent study by Noble et al. ( 2020 ), which looked into student feedback literacy in the workplace by probing into the perceptions of a group of Australian healthcare students towards a feedback literacy training programme conducted prior to their placement. There is, however, a dearth of primary research in other areas where elicitation, process, and enactment of feedback are vital; for instance, academics’ feedback literacy. In the ‘publish or perish’ culture of higher education, academics, especially ECRs, face immense pressure to publish in top-tiered journals in their fields and face the daunting peer-review process, while juggling other teaching and administrative responsibilities (Hollywood et al., 2019 ; Tynan and Garbett 2007 ). Taking up the role of authors and reviewers, researchers have to possess the capacity and disposition to engage meaningfully with feedback provided by peer reviewers and to provide constructive comments to authors. Similar to students, researchers have to learn how to manage their emotions in the face of critical feedback, to understand the formative values of feedback, and to make informed judgements about the quality of feedback (Gravett et al., 2019 ). At the same time, feedback literacy of academics also resembles that of teachers. When considering the kind of feedback given to authors, academics who serve as peer reviewers have to (1) design opportunities for feedback uptake, (2) maintain a professional and supportive relationship with authors, and (3) take into account the practical dimension of giving feedback (e.g., how to strike a balance between quality of feedback and time constraints due to multiple commitments) (Carless and Winstone 2020 ). To address the above, one of the aims of the present study is to expand the application of feedback literacy as a useful analytical lens to areas outside the classroom, that is, scholarly peer-review activities in academia, by presenting, analysing, and synthesising the personal experiences of the authors as successful peer reviewers for academic journals.

Conceptual framework

We adopt a feedback literacy of peer reviewers framework (Chong 2021a ) as an analytical lens to analyse, systemise, and synthesise our own experiences and practices as scholarly peer reviewers (Fig. 1 ). This two-tier framework includes a dimension on the manifestation of feedback literacy, which categorises five features of feedback literacy of peer reviewers, informed by student and teacher feedback literacy frameworks by Carless and Boud ( 2018 ) and Carless and Winstone ( 2020 ). When engaging in scholarly peer review, reviewers are expected to be able to provide constructive and formative feedback, which authors can act on in their revisions ( engineer feedback uptake ). Besides, peer reviewers who are usually full-time researchers or academics lead hectic professional lives; thus, when writing reviewers’ reports, it is important for them to consider practically and realistically the time they can invest and how their various degrees of commitment may have an impact on the feedback they provide ( navigate responsibilities ). Furthermore, peer reviewers should consider the emotional and relational influences their feedback exert on the authors. It is crucial for feedback to be not only informative but also supportive and professional (Chong, 2018 ) ( maintain relationships ). Equally important, it is imperative for peer reviewers to critically reflect on their own experience in the scholarly peer-review process, including their experience of receiving and giving feedback to academic peers, as well as the ways authors and editors respond to their feedback ( reflect on feedback experienc e). Lastly, acting as gatekeepers of journals to assess the quality of manuscripts, peer reviewers have to demonstrate an accurate understanding of the journals’ aims, remit, guidelines and standards, and reflect those in their written assessments of submitted manuscripts ( understand standards ). Situated in the context of scholarly peer review, this collaborative autoethnographic study conceptualises feedback literacy not only as a set of abilities but also orientations (London and Smither, 2002 ; Steelman and Wolfeld, 2016 ), which refers to academics’ tendency, beliefs, and habits in relation to engaging with feedback (London and Smither, 2002 ). According to Cheung ( 2000 ), orientations are influenced by a plethora of factors, namely experiences, cultures, and politics. It is important to understand feedback literacy as orientations because it takes into account that feedback is a convoluted process and is influenced by a plethora of contextual and personal factors. Informed by ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1986 ; Neal and Neal, 2013 ) and synthesising existing feedback literacy models (Carless and Boud, 2018 ; Carless and Winstone, 2020 ; Chong, 2021a , 2021b ), we consider feedback literacy as a malleable, situated, and emergent construct, which is influenced by the interplay of various networked layers of ecological systems (Neal and Neal, 2013 ) (Fig. 1 ). Also important is that conceptualising feedback literacy as orientations avoids dichotomisation (feedback literate vs. feedback illiterate), emphasises the developmental nature of feedback literacy, and better captures the multifaceted manifestations of feedback engagement.

The outer ring of the figure shows the components of feedback literacy while the inner ring concerns the layers of contexts (ecosystems) which influence the manifestation of feedback literacy of peer reviewers.

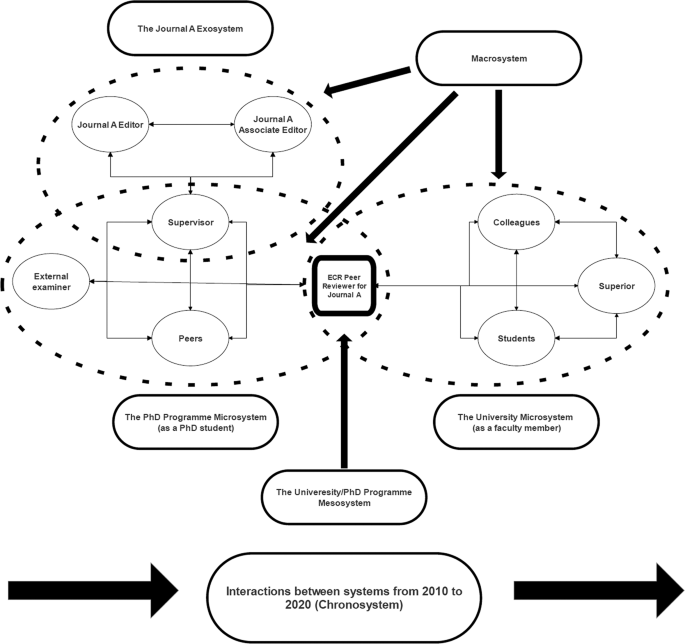

Echoing recent conceptual papers on feedback literacy which emphasises the indispensable role of contexts (Chong 2021b ; Boud and Dawson, 2021 ; Gravett et al., 2019 ), our conceptual framework includes an underlying dimension of networked ecological systems (micro, meso, exo, macro, and chrono), which portrays the contextual forces shaping our feedback orientations. Informed by the networked ecological system theory of Neal and Neal ( 2013 ), we postulate that there are five systems of contextual influence, which affect the feedback experience and development of feedback literacy of peer reviewers. The five ecological systems refer to ‘settings’, which is defined by Bronfenbrenner ( 1986 ) as “place[s] where people can readily engage in social interactions” (p. 22). Even though Bronfenbrenner’s ( 1986 ) somewhat dated definition of ‘place’ is limited to ‘physical space’, we believe that ‘places’ should be more broadly defined in the 21st century to encompass physical and virtual, recent and dated, closed and distanced locations where people engage; as for ‘interactions’, from a sociocultural perspective, we understand that ‘interactions’ can include not only social, but also cognitive and emotional exchanges (Vygotsky, 1978 ). Microsystem refers to a setting where people, including the focal individual, interact. Mesosystem , on the other hand, means the interactions between people from different settings and the influence they exert on the focal individual. An exosystem , similar to a microsystem, is understood as a single setting but this setting excludes the focal individual but it is likely that participants in this setting would interact with the focal individual. The remaining two systems, macrosystem and chronosystem, refer not only to ‘settings’ but ‘forces that shape the patterns of social interactions that define settings’ (Neal and Neal, 2013 , p. 729). Macrosystem is “the set of social patterns that govern the formation and dissolution of… interactions… and thus the relationship among ecological systems” (ibid). Some examples of macrosystems given by Neal and Neal ( 2013 ) include political and cultural systems. Finally, chronosystem is “the observation that patterns of social interactions between individuals change over time, and that such changes impact on the focal individual” (ibid, p. 729). Figure 2 illustrates this networked ecological systems theory using a hypothetical example of an early career researcher who is involved in scholarly peer review for Journal A; at the same time, they are completing a PhD and are working as a faculty member at a university.

This is a hypothetical example of an early career researcher who is involved in scholarly peer review for Journal A.

From the reviewed literature on the construct of feedback literacy, the investigation of feedback literacy as a personal, situated, and unfolding process is best done through an autoethnographic lens, which underscores critical self-reflection. Autoethnography refers to “an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyse (graphy) personal experience (auto) in order to understand cultural experience (ethno)” (Ellis et al., 2011 , p. 273). Autoethnography stems from research in the field of anthropology and is later introduced to the fields of education by Ellis and Bochner ( 1996 ). In higher education research, autoethnographic studies are conducted to illuminate on topics related to identity and teaching practices (e.g., Abedi Asante and Abubakari, 2020 ; Hains-Wesson and Young 2016 ; Kumar, 2020 ). In this article, a collaborative approach to autoethnography is adopted. Based on Chang et al. ( 2013 ), Lapadat ( 2017 ) defines collaborative autoethnography (CAE) as follows:

… an autobiographic qualitative research method that combines the autobiographic study of self with ethnographic analysis of the sociocultural milieu within which the researchers are situated, and in which the collaborating researchers interact dialogically to analyse and interpret the collection of autobiographic data. (p. 598)

CAE is not only a product but a worldview and process (Wall, 2006 ). CAE is a discrete view about the world and research, which straddles between paradigmatic boundaries of scientific and literary studies. Similar to traditional scientific research, CAE advocates systematicity in the research process and consideration is given to such crucial research issues as reliability, validity, generalisability, and ethics (Lapadat, 2017 ). In closer alignment with studies on humanities and literature, the goal of CAE is not to uncover irrefutable universal truths and generate theories; instead, researchers of CAE are interested in co-constructing and analysing their own personal narratives or ‘stories’ to enrich and/or challenge mainstream beliefs and ideas, embracing diverse rather than canonical ways of behaviour, experience, and thinking (Ellis et al., 2011 ). Regarding the role of researchers, CAE researchers openly acknowledge the influence (and also vulnerability) of researchers throughout the research process and interpret this juxtaposition of identities between researchers and participants of research as conducive to offering an insider’s perspective to illustrate sociocultural phenomena (Sughrua, 2019 ). For our CAE on the scholarly peer-review experiences of two ECRs, the purpose is to reconstruct, analyse, and publicise our lived experience as peer reviewers and how multiple forces (i.e., ecological systems) interact to shape our identity, experience, and feedback practice. As a research process, CAE is a collaborative and dynamic reflective journey towards self-discovery, resulting in narratives, which connect with and add to the existing literature base in a personalised manner (Ellis et al., 2011 ). The collaborators should go beyond personal reflection to engage in dialogues to identify similarities and differences in experiences to throw new light on sociocultural phenomena (Merga et al., 2018 ). The iterative process of self- and collective reflections takes place when CAE researchers write about their own “remembered moments perceived to have significantly impacted the trajectory of a person’s life” and read each other’s stories (Ellis et al., 2011 , p. 275). These ‘moments’ or vignettes are usually written retrospectively, selectively, and systematically to shed light on facets of personal experience (Hughes et al., 2012 ). In addition to personal stories, some autoethnographies and CAEs utilise multiple data sources (e.g., reflective essays, diaries, photographs, interviews with co-researchers) and various ways of expressions (e.g., metaphors) to achieve some sort of triangulation and to present evidence in a ‘systematic’ yet evocative manner (Kumar, 2020 ). One could easily notice that overarching methodological principles are discussed in lieu of a set of rigid and linear steps because the process of reconstructing experience through storytelling can be messy and emergent, and certain degree of flexibility is necessary. However, autoethnographic studies, like other primary studies, address core research issues including reliability (reader’s judgement of the credibility of the narrator), validity (reader’s judgement that the narratives are believable), and generalisability (resemblance between the reader’s experience and the narrative, or enlightenment of the reader regarding unfamiliar cultural practices) (Ellis et al., 2011 ). Ethical issues also need to be considered. For example, authors are expected to be honest in reporting their experiences; to protect the privacy of the people who ‘participated’ in our stories, pseudonyms need to be used (Wilkinson, 2019 ). For the current study, we follow the suggested CAE process outlined by Chang et al. ( 2013 ), which includes four stages: deciding on topic and method , collecting materials , making meaning , and writing . When deciding on the topic, we decided to focus on our experience as scholarly peer reviewers because doing peer review and having our work reviewed are an indispensable part of our academic lives. The next is to collect relevant autoethnographic materials. In this study, we follow Kumar ( 2020 ) to focus on multiple data sources: (1) reflective essays which were written separately through ‘recalling’, which is referred to by Chang et al. ( 2013 ) as ‘a free-spirited way of bringing out memories about critical events, people, place, behaviours, talks, thoughts, perspectives, opinions, and emotions pertaining to the research topic’ (p. 113), and (2) discussion meetings. In our reflective essays, we included written records of reflection and excerpts of feedback in our peer-review reports. Following material collection is meaning making. CAE, as opposed to autoethnography, emphasises the importance of engaging in dialogues with collaborators and through this process we identify similarities and differences in our experiences (Sughrua, 2019 ). To do so, we exchanged our reflective essays; we read each other’s reflections and added questions or comments on the margins. Then, we met online twice to share our experiences and exchange views regarding the two reflective essays we wrote. Both meetings lasted for approximately 90 min, were audio-recorded and transcribed. After each meeting, we coded our stories and experiences with reference to the two dimensions of the ecological framework of feedback literacy (Fig. 1 ). With regards to coding our data, we followed the model of Miles and Huberman ( 1994 ), which comprises four stages: data reduction (abstracting data), data display (visualising data in tabular form), conclusion-drawing, and verification. The coding and writing processes were done collaboratively on Google Docs and care was taken to address the aforesaid ethical (e.g., honesty, privacy) and methodological issues (e.g., validity, reliability, generalisability). As a CAE study, the participants are the researchers themselves, that is, the two authors of this paper. We acknowledge that research data are collected from human subjects (from the two authors), such data are collected in accordance with the standards and guidelines of the School Research Ethics Committee at the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work, Queen’s University Belfast (Ref: 005_2021). Despite our different experiences in our unique training and employment contexts, we share some common characteristics, both being ECRs (<5 years post-PhD), working in the field of education, active in the scholarly publication process as both authors and peer reviewers. Importantly for this study, we were both recipients of Reviewer of the Year Award 2019 awarded jointly by the journal, Higher Education Research & Development and the publisher , Taylor & Francis. This award in recognition of the quality of our reviewing efforts, as determined by the editorial board of a prestigious higher education journal, provided a strong impetus for this study, providing an opportunity to reflect on our own experiences and practices. The extent of our peer-review activities during our early career leading up to the time of data collection is summarised in Table 1 .

Findings and discussion

Analysis of the four individual essays (E1 and E2 for each participant) and transcripts of the two subsequent discussions (D1 and D2) resulted in the identification of multiple descriptive codes and in turn a number of overarching themes (Supplementary Appendix 1). Our reporting of these themes is guided by our conceptual framework, where we first focus on the five manifestations of feedback literacy to highlight the experiences that contribute to our growth as effective and confident peer reviewers. Then, we report on the five ecological systems to unravel how each contextual layer develops our feedback literacy as peer reviewers. (Note that the discussion of the chronosystem has been necessarily incorporated into each of the four others dimensions: microsystem , mesosystem , exosystem , and macrosystem in order to demonstrate temporal changes). In particular, similarities and differences will be underscored, and connections with manifested feedback beliefs and behaviours will be made. We include quotes from both Author 1 (A1) and Author 2 (A2), in order to illustrate our findings, and to show the richness and depth of the data collected (Corden and Sainsbury, 2006 ). Transcribed quotes may be lightly edited while retaining meaning, for example through the removal of fillers and repetitions, which is generally accepted practice to ensure readability ( ibid ).

Manifestations of feedback literacy

Engineering feedback uptake.

The two authors have a strong sense of the purpose of peer review as promoting not only research quality, but the growth of researchers. One way that we engineer author uptake is to ensure that feedback is ‘clear’ (A2,E1), ‘explicit’ (A2,E1), ‘specific’ (A1,E1), and importantly ‘actionable… to ensure that authors can act on this feedback so that their manuscripts can be improved and ultimately accepted for publication’ (A1,E1). In less than favourable author outcomes, we ensure that there is reference to the role of the feedback in promoting the development of the manuscript, which A1 refers to as ‘promotion of a growth mindset’ (A1,E1). For example, after requesting a second round of major revisions, A2 ‘acknowledged the frustration that the author might have felt on getting further revisions by noting how much improvement was made to the paper, but also making clear the justification for sending it off for more work’ (A2,E1). We both note that we tend to write longer reviews when a rejection is the recommended outcome, as our ultimate goal is to aid in the development of a manuscript.

Rejections doesn’t mean a paper is beyond repair. It can still be fixed and improved; a rejection simply means that the fix may be too extensive even for multiple review cycles. It is crucial to let the authors whose manuscripts are rejected know that they can still act on the feedback to improve their work; they should not give up on their own work. I think this message is especially important to first-time authors or early career researchers. (A1,E1)

In promoting a growth mindset and in providing actionable feedback, we hope to ‘show the authors that I’m not targeting them, but their work’ (A1,D1). We particularly draw on our own experiences as ECRs, with first-hand understanding that ‘everyone takes it personally when they get rejected. Yeah. Moreover, it is hard to separate (yourself from the paper)’ (A2,D1).

Navigating responsibilities

As with most academics, the two authors have multiple pressures on their time, and there ‘isn’t much formal recognition or reward’ (A1,E1) and ‘little extrinsic incentive for me to review’ (A2,E1). Nevertheless we both view our roles as peer reviewers as ‘an important part of the process’ (A2,E1), ‘a modest way for me to give back to the academic community’ (A1,E1). Through peer review we have built a sense of ‘identity as an academic’ (A1,D1), through ‘being a member of the academic community’ (A2,D1). While A1 commits to ‘review as many papers as possible’ (A1,E1) and A2 will usually accept offers to review, there are still limits on our time and therefore we consider the topic and methods employed when deciding whether or not to accept an invitation, as well as the journal itself, as we feel we can review more efficiently for journals with which we are more familiar. A1 and A2 have different processes for conducting their review that are most efficient for their own situations. For A1, the process begins with reading the whole manuscript in one go, adding notes to the pdf document along the way, which he then reviews, and makes a tentative decision, including ‘a few reasons why I have come to this decision’ (A1,E1). After waiting at least one day, he reviews all of the notes and begins writing the report, which is divided into the sections of the paper. He notes it ‘usually takes me 30–45 min to write a report. I then proofread this report and submit it to the system. So it usually takes me no more than three hours to complete a review’ (A1,E1). For A2, the process for reviewing and structuring the report is quite different, with a need to ‘just find small but regular opportunities to work on the review’ (A2,E1). As was the case during her Ph.D, which involved juggling research and raising two babies, ‘I’ve trained myself to be able to do things in bits’ (A2,D1). So A2 also begins by reading the paper once through, although generally without making initial comments. The next phase involves going through the paper at various points in time whenever possible, and at the same time building up the report, making the report structurally slightly different to that of A1.

What my reviews look like are bullet points, basically. And they’re not really in a particular order. They generally… follow the flow (of the paper). But I mean, I might think of something, looking at the methods and realise, hey, you haven’t defined this concept in the literature review so I’ll just add you haven’t done this. And so I will usually preface (the review)… Here’s a list of suggestions. Some of them are minor, some of them are serious, but they’re in no particular order. (A1,D1)

As such, both reviewers engage in personalised strategies to make more effective use of their time. Both A1 and A2 give explicit but not exhaustive examples of an area of concern, and they also pose questions for the author to consider, in both cases placing the onus back on the author to take action. As A1 notes, ‘I’m not going to do a summary of that reference for you. I’m just going to include that there. If you’d like you can check it out’ (A1,D1). For A2, a lack of adequate reporting of the methods employed in a study makes it difficult to proceed, and in such cases will not invest further time, sending it back to the editor, because ‘I can’t even comment on the findings… I can’t go on. I’m not gonna waste my time’ (A2,D1). In cases where the authors may be ‘on the fence’ about a particular review, they will use the confidential comments to the editor to help work through difficult cases as ‘they are obviously very experienced reviewers’ (A1,D1). Delegating tasks to the expertise of the editorial teams when appropriate also ensures time is used more prudently.

Maintaining relationships

Except in a few cases where A2 has reviewed for journals with a single-blind model, the vast majority of the reviews that we have completed have been double-blind. This means that we are unaware of the identity of the author/s, and we are unknown to them. However, ‘even with blind-reviews I tend to think of it as a conversation with a person’ (A2,E1). A1 talks about the need to have respect for the author and their expertise and effort ‘regardless of the quality of the submission (which can be in some cases subjective)’ (A1,E1). A2 writes similarly about the ‘privilege’ and ‘responsibility’ of being able to review manuscripts that authors ‘have put so much time and energy into possibly over an extended period’ (A2,E1). In this way it is possible to develop a sort of relationship with an author even without knowing their identity. In trying to articulate the nature of that relationship (which we struggle to do so definitively), we note that it is more than just a reviewer, and A2 reflected on a recent review, which went through a number of rounds of resubmission where ‘it felt like we were developing a relationship, more like a mentor than a reviewer’ (A2,E1).

I consider this role as a peer reviewer more than giving helpful and actionable feedback; I would like to be a supporter and critical friend to the authors, even though in most cases I don’t even know who they are or what career stage they are at (A1,E1).

In any case, as A1 notes, ‘we don’t even need to know who that person is because we know that people like encouragement’ (A1,D1), and we are very conscious of the emotional impact that feedback can have on authors, and the inherent power imbalance in the relationship. For this reason, A1 is ‘cautious about the way I write so that I don’t accidentally make the authors the target of my feedback’. As A2 notes ‘I don’t want authors feeling depressed after reading a review’ (A2,E1). While we note that we try to deliver our feedback with ‘respect’ (A1,E1; A1,E2; A2,D1) ‘empathy’ (A1,E1), and ‘kindness’ (A2,D1), we both noted that we do not ‘sugar coat’ our feedback and A1 describes himself as ‘harsh’ and ‘critical’ (A1,E1) while A2 describes herself as ‘pretty direct’ (A2,E1). In our discussion, we tried to delve into this seeming contradiction:… the encouragement, hopefully is to the researcher, but the directness it should be, I hope, is related directly to whatever it is, the methods or the reporting or the scope of the literature review. It’s something specific about the manuscript itself. And I know myself, being an ECR and being reviewed, that it’s hard to separate yourself from your work… And I want to make it really explicit. If it’s critical, it’s not about the person. It’s about the work, you know, the weakness of the work, but not the person. (A2,D1)

A1 explains that at times his initial report may be highly critical, and at times he will ‘sit back and rethink… With empathy, I will write feedback, which is more constructive’ (A1,E1). However, he adds that ‘I will never try to overrate a piece or sugar-coat my comments just to sound “friendly”’ (A1,E1), with the ultimate goal being to uphold academic rigour. Thus, honesty is seen as the best strategy to maintain a strong, professional relationship with reviewers. Another strategy employed by A2 is showing explicit commitment to the review process. One way this is communicated is by prefacing a review with a summary of the paper, not only ‘to confirm with the author that I am interpreting the findings in the way that they intended, but also importantly to show that I have engaged with the paper’ (A2,E1). Further, if the recommendation is for a further round of review, she will state directly to the authors ‘that I would be happy to review a revised manuscript’ (A2,E1).

Reflecting on feedback experience

As ECRs we have engaged in the scholarly publishing process initially as authors, subsequently as reviewers, and most recently as Associate Editors. Insights gained in each of these roles have influenced our feedback practices, and have interacted to ‘develop a more holistic understanding of the whole review process’ (A1,E1).

We reflect on our experiences as authors beginning in our doctoral candidatures, with reviews that ranged from ‘the most helpful to the most cynical’ (A1,E1). A2 reflected on two particular experiences both of which resulted in rejection, one being ‘snarky’ and ‘unprofessional’ with ‘no substance’, the other providing ‘strong encouragement … the focus was clearly on the paper and not me personally’ (A2,E1). It was this experience that showed the divergence between the tone and content of review despite the same outcome, and as result A2 committed to being ‘ the amazing one’. A1 also drew from a negative experience noting that ‘I remember the least useful feedback as much as I do with the most constructive one’ (A1,E1). This was particularly the case when a reviewer made apparently politically-motivated judgements that A1 ‘felt very uncomfortable with’ and flagged with the editor (A1,E1). Through these experiences both authors wrote in their essays about the need to focus on the work and not on the individual, with an understanding that a review ‘can have a really serious impact’ (A2,D1) on an author.

It is important to note that neither authors have been involved in any formal or informal training on how to conduct peer review, although A1 expresses appreciation of the regular practice of one journal for which he reviews, where ‘the editor would write an email to the reviewers giving feedback on the feedback we have given’ (A1,E1). For A2, an important source of learning is in comparing her reviews with that of others who have reviewed the same manuscript, the norm for some journals being to send all reports to all reviewers along with the final decision.

I’m always interested to see how [my] review compares with others. Have I given the same recommendation? Have I identified the same areas of weakness? Have I formatted my review in the same way? How does the tone of delivery differ? I generally find that I give a similar if not the same response to other reviews, and I’m happy to see that I often pick up the same issues with methodology. (A2,E1)

For A2 there is comfort in seeing reviews that are similar to others, although we both draw on experiences where our recommendation diverged from others, with a source of assurance being the ultimate decision of the editor.

So it’s like, I don’t think it can be published and that [other] reviewer thinks it’s excellent. So usually, what the editor would do in this instance is invite the third one. Right, yeah. But then this editor told me… that they decided to go with my decision to reject because they find that my comments are more convincing. (A1,D1)

A2 also was surprised to read another report of the same manuscript she reviewed, that raised similar concerns and gave the same recommendation for major revisions, but noted the ‘wording is soooo snarky. What need?’ (A2,E1). In one case that A1 detailed in our first discussion, significant but improbable changes made to the methodology section of a resubmitted paper caused him to question the honesty of the reporting, making him ‘uncomfortable’ and as a result reported his concerns to the editor. In this case the review took some time to craft, trying to balance the ‘fine line between catering for the emotion [of the author], right, and upholding the academic standards’ (A1,D1). While he conceded initially his report was ‘kind of too harsh… later I think I rephrased it a little bit, I kind of softened (it)’.

While the role of Associate Editor is very new to A2 and thus was yet unable to comment, for A1 the ‘opportunity to read various kinds of comments given by reviewers’ (A1,E1) is viewed favourably. This includes not only how reviewers structure their feedback, but also how they use the confidential comments to the editors to express their thoughts more openly, providing important insights into the process that are largely hidden.

Understanding standards

While our reviewing practices are informed more broadly ‘according to more general academic standards of the study itself, and the clarity and fullness of the reporting’ (A2,E1), we look in the first instance to advice and guidelines from journals to develop an understanding of journal-specific standards, although A2 notes that a lack of review guidelines for one of the earliest journals she reviewed led her to ‘searching Google for standard criteria’ (A2,E1). However, our development in this area seems to come from developing a familiarity with a journal, particularly through engagement with the journal as an author.

In addition to reading the scope and instructions for authors to obtain such basic information as readership, length of submissions, citation style, the best way for me to understand the requirements and preferences of the journals is my own experience as an author. I review for journals which I have published in and for those which I have not. I always find it easier to make a judgement about whether the manuscripts I review meet the journal’s standards if I have published there before. (A1,E1)

Indeed, it seems that journal familiarity is connected closely to our confidence in reviewing, and while both authors ‘review for journals which I have published in and for those which I have not’ (A1,E1), A2 states that she is reluctant to ‘readily accept an offer to review for a journal that I’m not familiar with’, and A1 takes extra time to ‘do more preparatory work before I begin reading the manuscript and writing the review’ when reviewing for an unfamiliar journal.

Ecological systems

Microsystem.

Three microsystems exert influence on A1’s and A2’s development of feedback literacy: university, journal community, and Twitter.

In regards to the university, we are full-time academics in research-intensive universities in the UK and Japan where expectations for academics include publishing research in high-impact journals ‘which is vital to promotion’ (A1,E2). It is especially true in A2’s context where the national higher education agenda is to increase world rankings of universities. Thus, ‘there is little value placed on peer review, as it is not directly related to the broader agenda’ (A2,E2). When considering his recent relocation to the UK together with the current pandemic, A1 navigated his responsibilities within the university context and decided to allocate more time to his university-related responsibilities, especially providing learning and pastoral support to his students, who are mostly international students. Besides, A2 observed that there is a dearth of institution-wide support on conducting peer review although ‘there are a lot of training opportunities related to how to write academic papers in English, how to present at international conferences, how to write grant applications’, etc. (A2,E2). As a result, she ‘struggled for a couple of years’ because of the lack of institutional support for her development as a peer reviewer’ (A2,D2); but this helplessness also motivated her to seek her own ways to learn how to give feedback, such as ‘seeing through glimpses of other reviews, how others approach it, in terms of length, structure, tone, foci etc.’ (A2,E2). A1 shares the same view that no training is available at his institution to support his development as a peer reviewer. However, his postgraduate supervision experiences enabled him to reflect on how his feedback can benefit researchers. In our second online discussion, A1 shared that he held individual advising sessions with some postgraduate students, which made him realise that it is important for feedback to serve the function to inspire rather than to ‘give them right answers’ (A1,D2).

Because of the lack of formal training provided by universities, both authors searched for other professional communities to help us develop our expertise in giving feedback as peer reviewers, with journal communities being the next microsystem. We found that international journals provide valuable opportunities for us to understand more about the whole peer-review process, in particular the role of feedback. For A1, the training which he received from the editor-in-chief when he took up the associate editorship of a language education journal two years ago was particularly useful. A1 benefited greatly from meetings with the editor who walked him through every stage in the review process and provided ‘hands-on experience on how to handle delicate scenarios’ (A1,E2). Since then, A1 has had plenty of opportunities to oversee various stages of peer review and read a large number of reviewers’ reports which helped him gain ‘a holistic understanding of the peer-review process’ (A1,E2) and gradually made him become more cognizant of how he wants to give feedback. Although there was no explicit instruction on the technical aspect of giving feedback, A1 found that being an associate editor has developed his ‘consciousness’ and ‘awareness’ of giving feedback as a peer reviewer (A1,D2). Further, he felt that his editorial experiences provided him the awareness to constantly refine and improve his ways of giving feedback, especially ways to make his feedback ‘more structured, evidence-based, and objective’ (A1,E2). Despite not reflecting from the perspective of an editor, A2 recalled her experience as an author who received in-depth and constructive feedback from a reviewer, which really impacted the way she viewed the whole review process. She understood from this experience that even though the paper under review may not be particularly strong, peer reviewers should always aim to provide formative feedback which helps the authors to improve their work. These positive experiences of the two authors are impactful on the ways they give feedback as peer reviewers. In addition, close engagement with a specific journal has helped A2 to develop a sense of belonging, making it ‘much more than a journal, but also a way to become part of an academic community’ (A2,E2). With such a sense of belonging, it is more likely for her to be ‘pulled towards that journal than others’ when she can only review a limited number of manuscripts (A2,D2).

Another professional community in which we are both involved is Twitter. We regard Twitter as a platform for self-learning, reflection, and inspiration. We perceive Twitter as a space where we get to learn from others’ peer-review experiences and disciplinary practices. For example, A1 found the tweets on peer-review informative ‘because they are written by different stakeholders in the process—the authors, editors, reviewers’ and offer ‘different perspectives and sometimes different versions of the same story’ (A1,E2). A2 recalled a tweet she came across about the ‘infamous Reviewer 2’ and how she learned to not make the same mistakes (A2,D2). Reading other people’s experiences helps us reconsider our own feedback practices and, more broadly, the whole peer-review system because we ‘get a glimpse of the do’s and don’ts for peer reviewers’ (A1,E2).

Further to our three common microsystems, A2 also draws on a unique microsystem, that of her former profession as a teacher, which shapes her feedback practices in three ways. First, in her four years of teacher training, a lot of emphasis was placed on assessment and feedback such as ‘error correction’; this understanding related to giving feedback to students and was solidified through ‘learning on the job’ (A2,D2). Second, A2 acknowledges that as a teacher, she has a passion to ‘guide others in their knowledge and skill development… and continue this in our review practices’ (A2,E2). Finally, her teaching experience prepared her to consider the authors’ emotional responses in her peer-review feedback practices, constantly ‘thinking there’s a person there who’s going to be shattered getting a rejection’ (A2,D2).

Mesosystem considers the confluence of our interactions in various microsystems. Particularly, we experienced a lack of support from our institutions, which pushed us to seek alternative paths to acquire the art of giving feedback. This has made us realise the importance of self-learning in developing feedback literacy as peer reviewers, especially in how to develop constructive and actionable feedback. Both authors self-learn how to give feedback by reading others’ feedback. A1 felt ‘fortunate to be involved in journal editing and Twitter’ because he gets ‘a glimpse of how other peer reviewers give feedback to authors’ (A1,E2). A2, on the other hand, learned through her correspondences with a journal editor who made her stop ‘looking for every word’ and move away from ‘over proofreading and over editing’ (A2,D2).

Focusing on the chronosystem, it is noticed that both authors adjusted how they give feedback over time because of the aggregated influence of their microsystems. What stands out is that they have become more strategic in giving feedback. One way this is achieved is through focusing their comments on the arguments of the manuscripts instead of burning the midnight oil with error-correcting.

Exosystem concerns the environment where the focal individuals do not have direct interactions with the people in it but have access to information about. In his case, A1’s understanding of advising techniques promoted by a self-access language learning centre is conducive to the cultivation of his feedback literacy. Although A1 is not a part of the language advising team, he has a working relationship with the director. A1 was especially impressed by the learner-centeredness of an advising process:

The primary duty of the language advisor is not to be confused with that of a language teacher. Language teachers may teach a lecture on a linguistic feature or correct errors on an essay, but language advisors focus on designing activities and engaging students in dialogues to help them reflect on their own learning needs… The advisors may also suggest useful resources to the students which cater to their needs. In short, language advisors work in partnership with the students to help them improve their language while language teachers are often perceived as more authoritative figures (A1, E2).

His understanding of advising has affected how A1 provides feedback as a peer reviewer in a number of ways. First, A1 places much more emphasis on humanising his feedback, for example, by considering ‘ways to work in partnership with the authors and making this “partnership mindset” explicit to the authors through writing’ (A1,E2). One way to operationalise this ‘partnership mindset’ in peer review is to ‘ask a lot of questions’ and provide ‘multiple suggestions’ for the authors to choose from (A1,E2). Furthermore, his knowledge of the difference between feedback as giving advice and feedback as instruction has led him to include feedback, which points authors to additional resources. Below is a feedback point A1 gave in one of his reviews:

The description of the data analysis process was very brief. While we are not aiming at validity and reliability in qualitative studies, it is important for qualitative researchers to describe in detail how the data collected were analysed (e.g. iterative coding, inductive/deductive coding, thematic analysis) in order to ascertain that the findings were credible and trustworthy. See Johnny Saldaña’s ‘The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers’.