An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Pharm Educ

- v.74(8); 2010 Oct 11

Presenting and Evaluating Qualitative Research

The purpose of this paper is to help authors to think about ways to present qualitative research papers in the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education . It also discusses methods for reviewers to assess the rigour, quality, and usefulness of qualitative research. Examples of different ways to present data from interviews, observations, and focus groups are included. The paper concludes with guidance for publishing qualitative research and a checklist for authors and reviewers.

INTRODUCTION

Policy and practice decisions, including those in education, increasingly are informed by findings from qualitative as well as quantitative research. Qualitative research is useful to policymakers because it often describes the settings in which policies will be implemented. Qualitative research is also useful to both pharmacy practitioners and pharmacy academics who are involved in researching educational issues in both universities and practice and in developing teaching and learning.

Qualitative research involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data that are not easily reduced to numbers. These data relate to the social world and the concepts and behaviors of people within it. Qualitative research can be found in all social sciences and in the applied fields that derive from them, for example, research in health services, nursing, and pharmacy. 1 It looks at X in terms of how X varies in different circumstances rather than how big is X or how many Xs are there? 2 Textbooks often subdivide research into qualitative and quantitative approaches, furthering the common assumption that there are fundamental differences between the 2 approaches. With pharmacy educators who have been trained in the natural and clinical sciences, there is often a tendency to embrace quantitative research, perhaps due to familiarity. A growing consensus is emerging that sees both qualitative and quantitative approaches as useful to answering research questions and understanding the world. Increasingly mixed methods research is being carried out where the researcher explicitly combines the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the study. 3 , 4

Like healthcare, education involves complex human interactions that can rarely be studied or explained in simple terms. Complex educational situations demand complex understanding; thus, the scope of educational research can be extended by the use of qualitative methods. Qualitative research can sometimes provide a better understanding of the nature of educational problems and thus add to insights into teaching and learning in a number of contexts. For example, at the University of Nottingham, we conducted in-depth interviews with pharmacists to determine their perceptions of continuing professional development and who had influenced their learning. We also have used a case study approach using observation of practice and in-depth interviews to explore physiotherapists' views of influences on their leaning in practice. We have conducted in-depth interviews with a variety of stakeholders in Malawi, Africa, to explore the issues surrounding pharmacy academic capacity building. A colleague has interviewed and conducted focus groups with students to explore cultural issues as part of a joint Nottingham-Malaysia pharmacy degree program. Another colleague has interviewed pharmacists and patients regarding their expectations before and after clinic appointments and then observed pharmacist-patient communication in clinics and assessed it using the Calgary Cambridge model in order to develop recommendations for communication skills training. 5 We have also performed documentary analysis on curriculum data to compare pharmacist and nurse supplementary prescribing courses in the United Kingdom.

It is important to choose the most appropriate methods for what is being investigated. Qualitative research is not appropriate to answer every research question and researchers need to think carefully about their objectives. Do they wish to study a particular phenomenon in depth (eg, students' perceptions of studying in a different culture)? Or are they more interested in making standardized comparisons and accounting for variance (eg, examining differences in examination grades after changing the way the content of a module is taught). Clearly a quantitative approach would be more appropriate in the last example. As with any research project, a clear research objective has to be identified to know which methods should be applied.

Types of qualitative data include:

- Audio recordings and transcripts from in-depth or semi-structured interviews

- Structured interview questionnaires containing substantial open comments including a substantial number of responses to open comment items.

- Audio recordings and transcripts from focus group sessions.

- Field notes (notes taken by the researcher while in the field [setting] being studied)

- Video recordings (eg, lecture delivery, class assignments, laboratory performance)

- Case study notes

- Documents (reports, meeting minutes, e-mails)

- Diaries, video diaries

- Observation notes

- Press clippings

- Photographs

RIGOUR IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative research is often criticized as biased, small scale, anecdotal, and/or lacking rigor; however, when it is carried out properly it is unbiased, in depth, valid, reliable, credible and rigorous. In qualitative research, there needs to be a way of assessing the “extent to which claims are supported by convincing evidence.” 1 Although the terms reliability and validity traditionally have been associated with quantitative research, increasingly they are being seen as important concepts in qualitative research as well. Examining the data for reliability and validity assesses both the objectivity and credibility of the research. Validity relates to the honesty and genuineness of the research data, while reliability relates to the reproducibility and stability of the data.

The validity of research findings refers to the extent to which the findings are an accurate representation of the phenomena they are intended to represent. The reliability of a study refers to the reproducibility of the findings. Validity can be substantiated by a number of techniques including triangulation use of contradictory evidence, respondent validation, and constant comparison. Triangulation is using 2 or more methods to study the same phenomenon. Contradictory evidence, often known as deviant cases, must be sought out, examined, and accounted for in the analysis to ensure that researcher bias does not interfere with or alter their perception of the data and any insights offered. Respondent validation, which is allowing participants to read through the data and analyses and provide feedback on the researchers' interpretations of their responses, provides researchers with a method of checking for inconsistencies, challenges the researchers' assumptions, and provides them with an opportunity to re-analyze their data. The use of constant comparison means that one piece of data (for example, an interview) is compared with previous data and not considered on its own, enabling researchers to treat the data as a whole rather than fragmenting it. Constant comparison also enables the researcher to identify emerging/unanticipated themes within the research project.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative researchers have been criticized for overusing interviews and focus groups at the expense of other methods such as ethnography, observation, documentary analysis, case studies, and conversational analysis. Qualitative research has numerous strengths when properly conducted.

Strengths of Qualitative Research

- Issues can be examined in detail and in depth.

- Interviews are not restricted to specific questions and can be guided/redirected by the researcher in real time.

- The research framework and direction can be quickly revised as new information emerges.

- The data based on human experience that is obtained is powerful and sometimes more compelling than quantitative data.

- Subtleties and complexities about the research subjects and/or topic are discovered that are often missed by more positivistic enquiries.

- Data usually are collected from a few cases or individuals so findings cannot be generalized to a larger population. Findings can however be transferable to another setting.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Research quality is heavily dependent on the individual skills of the researcher and more easily influenced by the researcher's personal biases and idiosyncrasies.

- Rigor is more difficult to maintain, assess, and demonstrate.

- The volume of data makes analysis and interpretation time consuming.

- It is sometimes not as well understood and accepted as quantitative research within the scientific community

- The researcher's presence during data gathering, which is often unavoidable in qualitative research, can affect the subjects' responses.

- Issues of anonymity and confidentiality can present problems when presenting findings

- Findings can be more difficult and time consuming to characterize in a visual way.

PRESENTATION OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH FINDINGS

The following extracts are examples of how qualitative data might be presented:

Data From an Interview.

The following is an example of how to present and discuss a quote from an interview.

The researcher should select quotes that are poignant and/or most representative of the research findings. Including large portions of an interview in a research paper is not necessary and often tedious for the reader. The setting and speakers should be established in the text at the end of the quote.

The student describes how he had used deep learning in a dispensing module. He was able to draw on learning from a previous module, “I found that while using the e learning programme I was able to apply the knowledge and skills that I had gained in last year's diseases and goals of treatment module.” (interviewee 22, male)

This is an excerpt from an article on curriculum reform that used interviews 5 :

The first question was, “Without the accreditation mandate, how much of this curriculum reform would have been attempted?” According to respondents, accreditation played a significant role in prompting the broad-based curricular change, and their comments revealed a nuanced view. Most indicated that the change would likely have occurred even without the mandate from the accreditation process: “It reflects where the profession wants to be … training a professional who wants to take on more responsibility.” However, they also commented that “if it were not mandated, it could have been a very difficult road.” Or it “would have happened, but much later.” The change would more likely have been incremental, “evolutionary,” or far more limited in its scope. “Accreditation tipped the balance” was the way one person phrased it. “Nobody got serious until the accrediting body said it would no longer accredit programs that did not change.”

Data From Observations

The following example is some data taken from observation of pharmacist patient consultations using the Calgary Cambridge guide. 6 , 7 The data are first presented and a discussion follows:

Pharmacist: We will soon be starting a stop smoking clinic. Patient: Is the interview over now? Pharmacist: No this is part of it. (Laughs) You can't tell me to bog off (sic) yet. (pause) We will be starting a stop smoking service here, Patient: Yes. Pharmacist: with one-to-one and we will be able to help you or try to help you. If you want it. In this example, the pharmacist has picked up from the patient's reaction to the stop smoking clinic that she is not receptive to advice about giving up smoking at this time; in fact she would rather end the consultation. The pharmacist draws on his prior relationship with the patient and makes use of a joke to lighten the tone. He feels his message is important enough to persevere but he presents the information in a succinct and non-pressurised way. His final comment of “If you want it” is important as this makes it clear that he is not putting any pressure on the patient to take up this offer. This extract shows that some patient cues were picked up, and appropriately dealt with, but this was not the case in all examples.

Data From Focus Groups

This excerpt from a study involving 11 focus groups illustrates how findings are presented using representative quotes from focus group participants. 8

Those pharmacists who were initially familiar with CPD endorsed the model for their peers, and suggested it had made a meaningful difference in the way they viewed their own practice. In virtually all focus groups sessions, pharmacists familiar with and supportive of the CPD paradigm had worked in collaborative practice environments such as hospital pharmacy practice. For these pharmacists, the major advantage of CPD was the linking of workplace learning with continuous education. One pharmacist stated, “It's amazing how much I have to learn every day, when I work as a pharmacist. With [the learning portfolio] it helps to show how much learning we all do, every day. It's kind of satisfying to look it over and see how much you accomplish.” Within many of the learning portfolio-sharing sessions, debates emerged regarding the true value of traditional continuing education and its outcome in changing an individual's practice. While participants appreciated the opportunity for social and professional networking inherent in some forms of traditional CE, most eventually conceded that the academic value of most CE programming was limited by the lack of a systematic process for following-up and implementing new learning in the workplace. “Well it's nice to go to these [continuing education] events, but really, I don't know how useful they are. You go, you sit, you listen, but then, well I at least forget.”

The following is an extract from a focus group (conducted by the author) with first-year pharmacy students about community placements. It illustrates how focus groups provide a chance for participants to discuss issues on which they might disagree.

Interviewer: So you are saying that you would prefer health related placements? Student 1: Not exactly so long as I could be developing my communication skill. Student 2: Yes but I still think the more health related the placement is the more I'll gain from it. Student 3: I disagree because other people related skills are useful and you may learn those from taking part in a community project like building a garden. Interviewer: So would you prefer a mixture of health and non health related community placements?

GUIDANCE FOR PUBLISHING QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Qualitative research is becoming increasingly accepted and published in pharmacy and medical journals. Some journals and publishers have guidelines for presenting qualitative research, for example, the British Medical Journal 9 and Biomedcentral . 10 Medical Education published a useful series of articles on qualitative research. 11 Some of the important issues that should be considered by authors, reviewers and editors when publishing qualitative research are discussed below.

Introduction.

A good introduction provides a brief overview of the manuscript, including the research question and a statement justifying the research question and the reasons for using qualitative research methods. This section also should provide background information, including relevant literature from pharmacy, medicine, and other health professions, as well as literature from the field of education that addresses similar issues. Any specific educational or research terminology used in the manuscript should be defined in the introduction.

The methods section should clearly state and justify why the particular method, for example, face to face semistructured interviews, was chosen. The method should be outlined and illustrated with examples such as the interview questions, focusing exercises, observation criteria, etc. The criteria for selecting the study participants should then be explained and justified. The way in which the participants were recruited and by whom also must be stated. A brief explanation/description should be included of those who were invited to participate but chose not to. It is important to consider “fair dealing,” ie, whether the research design explicitly incorporates a wide range of different perspectives so that the viewpoint of 1 group is never presented as if it represents the sole truth about any situation. The process by which ethical and or research/institutional governance approval was obtained should be described and cited.

The study sample and the research setting should be described. Sampling differs between qualitative and quantitative studies. In quantitative survey studies, it is important to select probability samples so that statistics can be used to provide generalizations to the population from which the sample was drawn. Qualitative research necessitates having a small sample because of the detailed and intensive work required for the study. So sample sizes are not calculated using mathematical rules and probability statistics are not applied. Instead qualitative researchers should describe their sample in terms of characteristics and relevance to the wider population. Purposive sampling is common in qualitative research. Particular individuals are chosen with characteristics relevant to the study who are thought will be most informative. Purposive sampling also may be used to produce maximum variation within a sample. Participants being chosen based for example, on year of study, gender, place of work, etc. Representative samples also may be used, for example, 20 students from each of 6 schools of pharmacy. Convenience samples involve the researcher choosing those who are either most accessible or most willing to take part. This may be fine for exploratory studies; however, this form of sampling may be biased and unrepresentative of the population in question. Theoretical sampling uses insights gained from previous research to inform sample selection for a new study. The method for gaining informed consent from the participants should be described, as well as how anonymity and confidentiality of subjects were guaranteed. The method of recording, eg, audio or video recording, should be noted, along with procedures used for transcribing the data.

Data Analysis.

A description of how the data were analyzed also should be included. Was computer-aided qualitative data analysis software such as NVivo (QSR International, Cambridge, MA) used? Arrival at “data saturation” or the end of data collection should then be described and justified. A good rule when considering how much information to include is that readers should have been given enough information to be able to carry out similar research themselves.

One of the strengths of qualitative research is the recognition that data must always be understood in relation to the context of their production. 1 The analytical approach taken should be described in detail and theoretically justified in light of the research question. If the analysis was repeated by more than 1 researcher to ensure reliability or trustworthiness, this should be stated and methods of resolving any disagreements clearly described. Some researchers ask participants to check the data. If this was done, it should be fully discussed in the paper.

An adequate account of how the findings were produced should be included A description of how the themes and concepts were derived from the data also should be included. Was an inductive or deductive process used? The analysis should not be limited to just those issues that the researcher thinks are important, anticipated themes, but also consider issues that participants raised, ie, emergent themes. Qualitative researchers must be open regarding the data analysis and provide evidence of their thinking, for example, were alternative explanations for the data considered and dismissed, and if so, why were they dismissed? It also is important to present outlying or negative/deviant cases that did not fit with the central interpretation.

The interpretation should usually be grounded in interviewees or respondents' contributions and may be semi-quantified, if this is possible or appropriate, for example, “Half of the respondents said …” “The majority said …” “Three said…” Readers should be presented with data that enable them to “see what the researcher is talking about.” 1 Sufficient data should be presented to allow the reader to clearly see the relationship between the data and the interpretation of the data. Qualitative data conventionally are presented by using illustrative quotes. Quotes are “raw data” and should be compiled and analyzed, not just listed. There should be an explanation of how the quotes were chosen and how they are labeled. For example, have pseudonyms been given to each respondent or are the respondents identified using codes, and if so, how? It is important for the reader to be able to see that a range of participants have contributed to the data and that not all the quotes are drawn from 1 or 2 individuals. There is a tendency for authors to overuse quotes and for papers to be dominated by a series of long quotes with little analysis or discussion. This should be avoided.

Participants do not always state the truth and may say what they think the interviewer wishes to hear. A good qualitative researcher should not only examine what people say but also consider how they structured their responses and how they talked about the subject being discussed, for example, the person's emotions, tone, nonverbal communication, etc. If the research was triangulated with other qualitative or quantitative data, this should be discussed.

Discussion.

The findings should be presented in the context of any similar previous research and or theories. A discussion of the existing literature and how this present research contributes to the area should be included. A consideration must also be made about how transferrable the research would be to other settings. Any particular strengths and limitations of the research also should be discussed. It is common practice to include some discussion within the results section of qualitative research and follow with a concluding discussion.

The author also should reflect on their own influence on the data, including a consideration of how the researcher(s) may have introduced bias to the results. The researcher should critically examine their own influence on the design and development of the research, as well as on data collection and interpretation of the data, eg, were they an experienced teacher who researched teaching methods? If so, they should discuss how this might have influenced their interpretation of the results.

Conclusion.

The conclusion should summarize the main findings from the study and emphasize what the study adds to knowledge in the area being studied. Mays and Pope suggest the researcher ask the following 3 questions to determine whether the conclusions of a qualitative study are valid 12 : How well does this analysis explain why people behave in the way they do? How comprehensible would this explanation be to a thoughtful participant in the setting? How well does the explanation cohere with what we already know?

CHECKLIST FOR QUALITATIVE PAPERS

This paper establishes criteria for judging the quality of qualitative research. It provides guidance for authors and reviewers to prepare and review qualitative research papers for the American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education . A checklist is provided in Appendix 1 to assist both authors and reviewers of qualitative data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to the 3 reviewers whose ideas helped me to shape this paper.

Appendix 1. Checklist for authors and reviewers of qualitative research.

Introduction

- □ Research question is clearly stated.

- □ Research question is justified and related to the existing knowledge base (empirical research, theory, policy).

- □ Any specific research or educational terminology used later in manuscript is defined.

- □ The process by which ethical and or research/institutional governance approval was obtained is described and cited.

- □ Reason for choosing particular research method is stated.

- □ Criteria for selecting study participants are explained and justified.

- □ Recruitment methods are explicitly stated.

- □ Details of who chose not to participate and why are given.

- □ Study sample and research setting used are described.

- □ Method for gaining informed consent from the participants is described.

- □ Maintenance/Preservation of subject anonymity and confidentiality is described.

- □ Method of recording data (eg, audio or video recording) and procedures for transcribing data are described.

- □ Methods are outlined and examples given (eg, interview guide).

- □ Decision to stop data collection is described and justified.

- □ Data analysis and verification are described, including by whom they were performed.

- □ Methods for identifying/extrapolating themes and concepts from the data are discussed.

- □ Sufficient data are presented to allow a reader to assess whether or not the interpretation is supported by the data.

- □ Outlying or negative/deviant cases that do not fit with the central interpretation are presented.

- □ Transferability of research findings to other settings is discussed.

- □ Findings are presented in the context of any similar previous research and social theories.

- □ Discussion often is incorporated into the results in qualitative papers.

- □ A discussion of the existing literature and how this present research contributes to the area is included.

- □ Any particular strengths and limitations of the research are discussed.

- □ Reflection of the influence of the researcher(s) on the data, including a consideration of how the researcher(s) may have introduced bias to the results is included.

Conclusions

- □ The conclusion states the main finings of the study and emphasizes what the study adds to knowledge in the subject area.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Online Metrics

Google Analytics Courses and Consulting

July 14, 2015 By Paul Koks Leave a Comment

Six Challenges of Qualitative Data Analysis

In an ideal world there is both valuable quantitative as well as qualitative data available to you.

You can’t say that one data source is better than the other. They complement each other and provide you with a more accurate picture of what’s going on and why.

Both data sources are very helpful in the field of conversion optimization.

Well thought out hypothesis – based on quantitative and qualitative data – are important to define the best A/B test experiments .

In this article I share six common problems with qualitative data that you should know.

Sampling-Related Problems

The first three limitations are sampling-related issues.

1. Limited Sample Size

Contrary to quantitative data where you often have a great amount of data available, is sample size one of the challenges of qualitative data.

If you browse on the internet, you find out there is no general agreement on the ideal sample size for qualitative research.

It is very costly to perform extensive qualitative research with hundreds of participants.

And is it really needed to question so many people to get valuable insights?

Watch this video to get a better understanding of this topic:

Two tips about your sample size:

- Rule of thumb: you need more participants if new participants keep on providing you with relevant, new insights.

- Be flexible; don’t rigidly set the number of participants at the start.

2. Sampling Bias

Sampling bias definition by Wikipedia :

“In statistics, sampling bias is a bias in which a sample is collected in such a way that some members of the intended population are less likely to be included than others.”

In other words, your qualitative sample will never include a representative overview of all the different people that come to your website.

It’s important to keep that in mind when interpreting test results.

3. Self-Selection Bias

Do you like to participate in surveys? A few of you might say “Yes” and others think “Arghhhh”.

This is the exact problem here. It’s a free choice to participate in a research study or not.

On the other side, quantitative data is gathered from most people whether they like it or not.

Just sign up for Hotjar , set up a heatmap and the data will be collected for you.

Ok, I don’t talk about the tech-savvy people here. ;-)

Sampling and self-selection biases are closely related and limit the usefulness of qualitative data.

Observation Biases

The second group of problems with qualitative data include observational biases.

4. Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne Effect can best be described as:

“Participants in behavioral studies change their behavior or performance in response to being observed.”

For example, your opinion about a particular website might be different when you know you are being observed if compared to when you (don’t know) you are being observed.

I recommend to watch this video (it clearly explains the Hawthorne Effect and its background):

5. Observer-Expectancy Effect

Let’s say you are running a survey and function as an observer in the research room. You are walking around and observe the participants.

Do you think you won’t influence the results?

It is known that researcher’s beliefs or expectations causes him or her to unconsciously influence the participants of an experiment. This is called the observer-expectancy effect.

6. Artificial Scenario

Most experiments include pre-set goals in a specific environment. And you can’t get feedback on things you don’t ask.

For example, you run an experiment for an ecommerce website .

Your goal is to find out whether the form (where people leave their personal information) functions well or if anything needs to be improved.

In this case it is such a focused goal so that you won’t learn about other valuable things through this study.

The participant might have a lot of other things to say, but without asking them you won’t know it.

Conclusions

As you can see, there are a many challenges with qualitative data.

However, marketers can perform extremely well if they use this data in combination with quantitative data to form strong A/B test hypothesis.

Refrain from changing your website on just a small set of qualitative responses.

Instead, enrich your conversion optimization framework with all data sources that are available to you and get more out of your testing efforts.

What’s your experience with qualitative data? Do you use it in combination with quantitative data?

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Online Metrics enhances your data quality and insights so that you can improve your business results. Learn more

Market Research

Qualitative Research: Understanding the Goal and Benefits for Effective Analysis

As market trends evolve at lightning speed in the age of digital transformation, having an intimate understanding of consumer desires and motivations is more critical than ever. Enter qualitative research – the knight in shining armor of deep-dive data analysis. In this blog post, we’ll be exploring the profound purpose and impressive benefits behind qualitative research, unveiling how it anchors effective market analysis and strategy development. Brace yourselves for a mesmerizing journey into the realm of potent insights that power consequential decisions and breed groundbreaking innovation.

The primary goal of qualitative research is to obtain insights into participants’ experiences and understanding of the world. This type of research provides rich descriptions and explanations of processes in identifiable local contexts. Qualitative research has several benefits including providing an in-depth understanding, being flexible and adaptable, and generating descriptive data that can be used to create new theories using the inductive method.

Qualitative Study’s Importance

Qualitative research holds a significant place in the realm of social science research and is integral for understanding the complexities of human behavior, experiences, and social interactions. Unlike quantitative research which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research collects non-numerical data and emphasizes interpreting meaning from social contexts.

The importance of qualitative research lies in its ability to provide rich descriptions and explanations of processes in identifiable local contexts. It allows researchers to gain insights into participants’ experiences and understand the world as another person experiences it. This deeper understanding paves the way for more comprehensive analyses and the development of theories that accurately represent the intricacies of human life.

For instance, imagine a sociologist interested in studying how individuals cope with unemployment during economic downturns. By conducting qualitative research , these sociologists can immerse themselves in the lives of unemployed individuals, observe their daily routines, conduct in-depth interviews, and analyze their personal narratives. This approach goes beyond simply quantifying unemployment rates; it provides an intimate understanding of how people navigate through difficult situations and sheds light on the emotional, psychological, and societal impacts.

In addition to providing rich insight into human experiences, qualitative research offers numerous other benefits that contribute to effective analysis.

- Qualitative research is essential in social science research as it allows for a deeper understanding of human behavior and social interactions. Its focus on non-numerical data collection and interpretation of meaning helps researchers gain insights into participants’ experiences and contextual factors. Qualitative research also provides rich descriptions and explanations of processes in identifiable local contexts, leading to the development of comprehensive analysis and accurate theories. Overall, qualitative research offers numerous benefits that contribute to effective analysis in social science research.

Goals & Benefits Driving Research

The goals of qualitative research are multifaceted. One primary objective is to investigate the meanings people attribute to their behavior and interactions within specific social contexts. This focus on subjective interpretations helps uncover individual perspectives that may be overlooked by quantitative methods alone. Additionally, qualitative research aims to explore social phenomena that are not easily measurable or quantifiable.

Qualitative research also generates descriptive data that requires rigorous methods of analysis. Researchers employ various techniques such as thematic analysis or grounded theory to identify patterns, themes, and categories within their data. These analytical approaches ensure systematic interpretation while maintaining the integrity of participants’ lived experiences.

Beyond these goals, qualitative research offers several benefits that aid in reliable analysis. Firstly, it provides an in-depth understanding of complex social issues by capturing the nuances and subtleties of human behavior. This depth allows researchers to generate rich descriptions and explanations that facilitate a comprehensive comprehension of social phenomena.

For example, consider a study exploring the experience of minority students in predominantly white institutions. Through qualitative research methods like interviews and focus groups, researchers can delve into the students’ lived experiences, their perceptions of inclusion or exclusion, and their strategies for navigating through institutional challenges. This level of detail paints a holistic picture that goes beyond quantitative statistics such as enrollment numbers.

Another advantage of qualitative research is its flexibility and adaptability. Researchers can modify their data collection methods to account for new insights or unexpected findings during the research process. This responsiveness allows for deeper exploration and ensures that no valuable information is left unexamined.

However, it is essential to acknowledge that qualitative research also has its limitations. These include the limited scope and generalizability of findings due to the smaller sample sizes typically used in qualitative studies. Additionally, there is a potential for researcher bias since the individuals collecting and analyzing the data play an active role in shaping the research process.

Nonetheless, while objectivity may be seen as a myth in qualitative research, researchers should be honest and transparent about their own biases and assumptions. Reflexivity, which involves acknowledging and critically examining one’s subjectivity throughout the research process, is integral to ensuring integrity and minimizing undue influence.

- According to a report from the Journal of Social Issues, as of 2022, around 45% of psychological studies used qualitative methods, signaling strong recognition in the field for its unique insights into human behavior.

- A study conducted by the Market Research Society confirmed that out of all market research carried out worldwide, approximately 20% utilize qualitative methodologies. This highlights its crucial role in understanding customer behaviors and motivations.

- The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) indicated that nearly 70% of health research incorporates some elements of qualitative research, underscoring its importance in contributing to our understanding of complex health issues and interventions.

Comprehensive Approaches

When conducting qualitative research , adopting comprehensive approaches is essential for capturing the richness and depth of data required for effective analysis. These approaches involve a holistic perspective that considers multiple dimensions and contexts. One commonly used comprehensive approach is triangulation , which involves using multiple data sources, methods, or perspectives to cross-verify findings. By triangulating data, researchers can enhance the reliability and validity of their analysis.

Another important approach is thick description , which focuses on providing detailed and vivid accounts of participants’ experiences and contexts. This technique enables researchers to capture the nuances and complexities of social phenomena, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the research topic. Thick descriptions typically include vivid narratives, dialogue excerpts, and detailed observations, providing readers with a rich portrayal of the study’s context.

Researchers may also adopt an iterative process in their analysis, where data collection and analysis occur simultaneously. This approach allows for constant refinement and adjustment of research questions and methods based on emerging findings. Through iteration, researchers can dive deeper into the topic, uncover unexpected insights, and explore various angles that contribute to a more comprehensive analysis.

It’s worth noting that comprehensive approaches in qualitative research require flexibility and openness to embracing emergent themes and unexpected directions. As researchers immerse themselves in the data, they should be willing to adapt their strategies accordingly.

Participant Engagement & Topic Exploration

Participant engagement plays a crucial role in qualitative research as it fosters a deeper understanding of participants’ perspectives and experiences. Effective engagement encourages open dialogue and trust between the researcher and participants, allowing for richer data collection. One way to promote participant engagement is through active listening . By attentively listening to participants’ stories, concerns, and viewpoints, researchers can demonstrate empathy and create a safe space for open expression.

Another aspect that greatly enhances participant engagement is establishing rapport . Building rapport involves creating a comfortable environment where participants feel at ease to share their thoughts and experiences. This can be achieved through transparent communication, respect for participants’ autonomy, and genuine interest in their stories. Researchers should establish a positive and respectful relationship with participants, positioning themselves as partners rather than authoritative figures.

In qualitative research, topic exploration is a dynamic and iterative process that allows researchers to uncover new insights and dimensions of the phenomenon under study. This involves probing deeper into participants’ responses, asking follow-up questions, and exploring unexpected avenues that emerge during data collection. By being open to revisiting research questions and digging deeper into topics, researchers can uncover valuable insights and gain a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

It’s important to note that participant engagement and topic exploration go hand in hand. Engaged participants are more likely to provide rich and detailed responses, leading to enhanced exploration of the research topic. Conversely, skillful topic exploration can foster deeper engagement from participants by demonstrating genuine interest and curiosity in their perspectives.

Effective Data Accumulation Methods

In qualitative research, the collection of rich and meaningful data is a crucial step toward understanding the complexities of human experiences. To ensure effective analysis, researchers need to employ appropriate data accumulation methods that capture the depth of participants’ perspectives and insights. Let’s explore some strategies that can facilitate this process.

One common method used in qualitative research is participant observation. This involves immersing oneself in the research setting, actively observing, and taking detailed notes on behaviors, interactions, and cultural nuances. By being present in the natural context, researchers gain a deeper understanding of the social dynamics and can document valuable data that may go unnoticed otherwise.

For instance, imagine a researcher interested in studying the experiences of healthcare workers in a hospital. Through participant observation, they can shadow these workers, witness their daily routines, the challenges they face, and even engage in conversations during breaks. This method provides an intimate look into their lives and generates valuable insights.

Another effective technique is in-depth interviews. These interviews allow researchers to establish a personal connection with participants and delve into their thoughts, feelings, and motivations regarding the research topic. It’s crucial to create an open and comfortable environment where participants feel safe sharing their views openly.

Additionally, focus groups are utilized as a powerful data accumulation method. Bringing together a small group of individuals who share similar characteristics or experiences allows for stimulating discussions that uncover diverse perspectives. Participants can build upon each other’s ideas and provide deeper insights collectively.

Having explored effective data accumulation methods like participant observation, in-depth interviews, and focus groups, let’s now dive into another important aspect of qualitative research – harnessing sensory inputs & eliciting verbal responses.

Harnessing Sensory Inputs and Eliciting Verbal Responses

Qualitative research aims to understand phenomena from the perspective of individuals involved. One way to achieve this is by harnessing sensory inputs and eliciting verbal responses, allowing participants to express themselves fully. This approach taps into a range of human senses and encourages participants to describe their experiences vividly.

For instance, researchers might utilize photovoice techniques, where participants capture images related to the research topic using cameras or smartphones. These visual representations allow participants to share their perspectives in a unique and powerful way.

Imagine a study exploring the impact of urbanization on community well-being. Participants could be asked to take pictures of spaces they feel contribute positively or negatively to their quality of life. These images can then be used as stimuli for further discussion, sparking conversations about the emotional and sensory aspects of the built environment.

In addition to visuals, researchers can also engage participants’ sense of hearing through audio recordings. By recording interviews, focus group discussions, or even ambient sounds in a particular environment, researchers can capture subtle nuances that may not be conveyed through written transcripts alone.

By harnessing sensory inputs and giving participants the space for verbal expression, qualitative researchers foster an environment where rich and nuanced data can be collected. This multi-sensory approach enables a deeper understanding of individuals’ experiences and allows us to gain insights beyond mere words.

Parsing and Conclusion Derivation from Data

In qualitative research, one of the primary goals is to parse and derive meaningful conclusions from the collected data. Unlike quantitative research which relies on statistical analysis, qualitative research involves obtaining rich descriptions of participants’ experiences and understanding the world as another person experiences it. The process of parsing and deriving conclusions from qualitative data requires a meticulous examination of the data, identification of patterns, themes, and connections, and an inductive approach to theory development.

Qualitative researchers immerse themselves in the data collected through methods such as interviews, observations, and focus groups. They carefully analyze transcripts, field notes, or documents to identify recurring themes or significant incidents that shed light on the research question. Through this process of coding and categorizing, researchers start to make sense of the data and identify key findings that can be used to develop theories or inform specific contexts.

For example, imagine a researcher conducting an ethnographic study exploring the experiences of undocumented immigrants in their journey toward citizenship. Through interviews and participant observation, they gather compelling stories and narratives about the challenges faced by these individuals. By carefully analyzing these stories for common themes such as navigating legal systems or facing social stigma, the researcher can derive conclusions about the complex processes involved in seeking legal status.

“Analyzing qualitative data is like piecing together a puzzle. Each interview or observation provides a unique piece that contributes to the overall picture.”

However, it is important to note that deriving conclusions from qualitative data is not a simple linear process. It requires reflexivity on the part of the researcher to acknowledge their own biases and assumptions that may influence their interpretation of the data. Reflexivity encourages researchers to critically reflect on how their own subjectivity affects their analysis and conclusions.

Advantages & Drawbacks of This Research Type

Qualitative research offers several advantages that contribute to its effectiveness in providing rich insights into social phenomena. First and foremost, it allows researchers to gain an in-depth understanding of the experiences, perspectives, and meanings that individuals attribute to their behavior and interactions. This depth of understanding is often difficult to achieve through quantitative research methods alone.

Moreover, qualitative research is known for its flexibility and adaptability. Researchers can modify their research design or data collection methods as they delve deeper into the field, responding to emerging themes or new areas of investigation. The open-ended nature of qualitative research also enables participants to express themselves freely and provide nuanced responses, offering a more comprehensive view of complex social phenomena.

On the other hand, there are some drawbacks to consider when conducting qualitative research. One challenge is the limited scope and generalizability of findings. Due to the small sample sizes typically involved in qualitative studies, it can be challenging to extrapolate findings to broader populations or contexts. Additionally, there is potential for researcher bias as interpretations of qualitative data are subjective and influenced by researchers’ perspectives and assumptions.

Despite these limitations, the benefits of qualitative research outweigh its drawbacks in many cases. By providing detailed insights into participants’ experiences, qualitative research contributes valuable knowledge that can inform policy decisions, improve interventions, and enhance our understanding of social phenomena.

Unlock the power of qualitative research with Discuss

In a world driven by meaningful connections, Discuss stands at the forefront of qualitative research, empowering you to delve deeper, understand better, and innovate with confidence. Elevate your research game—choose Discuss for insights that go beyond the surface. Navigate cultural nuances effortlessly. Our platform is designed to facilitate cross-cultural research, helping you understand and appreciate the local context that shapes consumer behavior around the world.

Why Discuss ?

- Unparalleled Access: Connect with your target audience effortlessly, breaking down geographical barriers and ensuring your research is truly representative.

- Real-time Collaboration: Seamlessly share ideas, gather feedback, and refine your approach on the fly.

- Rich Multimedia Insights: Witness authentic reactions, emotions, and body language that add layers of depth to your qualitative findings.

- Data-Driven Decision Making: Make informed decisions backed by real, human-driven data.

Sign Up for our Newsletter

Related articles.

Navigating Tomorrow: A Glimpse into the Future of Market Research in 2024

Author: Jim Longo, Co-founder & Chief Strategy Officer As a veteran with over 30 years in…

The Importance of a Market Research Analyst: Key Benefits and Skills

As the world becomes increasingly data-driven, understanding market trends is more crucial than ever for business…

Forrester and G2 Reports Explained

In this short video, Discuss’ Chief Growth Officer, Adam Mertz, highlights three recent industry reports and…

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data: 7 Key Differences

Qualitative data is information you can describe with words rather than numbers.

Quantitative data is information represented in a measurable way using numbers.

One type of data isn’t better than the other.

To conduct thorough research, you need both. But knowing the difference between them is important if you want to harness the full power of both qualitative and quantitative data.

In this post, we’ll explore seven key differences between these two types of data.

#1. The Type of Data

The single biggest difference between quantitative and qualitative data is that one deals with numbers, and the other deals with concepts and ideas.

The words “qualitative” and “quantitative” are really similar, which can make it hard to keep track of which one is which. I like to think of them this way:

- Quantitative = quantity = numbers-related data

- Qualitative = quality = descriptive data

Qualitative data—the descriptive one—usually involves written or spoken words, images, or even objects. It’s collected in all sorts of ways: video recordings, interviews, open-ended survey responses, and field notes, for example.

I like how researcher James W. Crick defines qualitative research in a 2021 issue of the Journal of Strategic Marketing : “Qualitative research is designed to generate in-depth and subjective findings to build theory.”

In other words, qualitative research helps you learn more about a topic—usually from a primary, or firsthand, source—so you can form ideas about what it means. This type of data is often rich in detail, and its interpretation can vary depending on who’s analyzing it.

Here’s what I mean: if you ask five different people to observe how 60 kittens behave when presented with a hamster wheel, you’ll get five different versions of the same event.

Quantitative data, on the other hand, is all about numbers and statistics. There’s no wiggle room when it comes to interpretation. In our kitten scenario, quantitative data might show us that of the 60 kittens presented with a hamster wheel, 40 pawed at it, 5 jumped inside and started spinning, and 15 ignored it completely.

There’s no ifs, ands, or buts about the numbers. They just are.

#2. When to Use Each Type of Data

You should use both quantitative and quantitative data to make decisions for your business.

Quantitative data helps you get to the what . Qualitative data unearths the why .

Quantitative data collects surface information, like numbers. Qualitative data dives deep beneath these same numbers and fleshes out the nuances there.

Research projects can often benefit from both types of data, which is why you’ll see the term “mixed-method” research in peer-reviewed journals. The term “mixed-method” refers to using both quantitative and qualitative methods in a study.

So, maybe you’re diving into original research. Or maybe you’re looking at other peoples’ studies to make an important business decision. In either case, you can use both quantitative and qualitative data to guide you.

Imagine you want to start a company that makes hamster wheels for cats. You run that kitten experiment, only to learn that most kittens aren’t all that interested in the hamster wheel. That’s what your quantitative data seems to say. Of the 60 kittens who participated in the study, only 5 hopped into the wheel.

But 40 of the kittens pawed at the wheel. According to your quantitative data, these 40 kittens touched the wheel but did not get inside.

This is where your qualitative data comes into play. Why did these 40 kittens touch the wheel but stop exploring it? You turn to the researchers’ observations. Since there were five different researchers, you have five sets of detailed notes to study.

From these observations, you learn that many of the kittens seemed frightened when the wheel moved after they pawed it. They grew suspicious of the structure, meowing and circling it, agitated.

One researcher noted that the kittens seemed desperate to enjoy the wheel, but they didn’t seem to feel it was safe.

So your idea isn’t a flop, exactly.

It just needs tweaking.

According to your quantitative data, 75% of the kittens studied either touched or actively participated in the hamster wheel. Your qualitative data suggests more kittens would have jumped into the wheel if it hadn’t moved so easily when they pawed at it.

You decide to make your kitten wheel sturdier and try the whole test again with a new set of kittens. Hopefully, this time a higher percentage of your feline participants will hop in and enjoy the fun.

This is a very simplistic and fictional example of how a mixed-method approach can help you make important choices for your business.

#3. Data You Have Access To

When you can swing it, you should look at both qualitative and quantitative data before you make any big decisions.

But this is where we come to another big difference between quantitative vs. qualitative data: it’s a lot easier to source qualitative data than quantitative data.

Why? Because it’s easy to run a survey, host a focus group, or conduct a round of interviews. All you have to do is hop on SurveyMonkey or Zoom and you’re on your way to gathering original qualitative data.

And yes, you can get some quantitative data here. If you run a survey and 45 customers respond, you can collect demographic data and yes/no answers for that pool of 45 respondents.

But this is a relatively small sample size. (More on why this matters in a moment.)

To tell you anything meaningful, quantitative data must achieve statistical significance.

If it’s been a while since your college statistics class, here’s a refresh: statistical significance is a measuring stick. It tells you whether the results you get are due to a specific cause or if they can be attributed to random chance.

To achieve statistical significance in a study, you have to be really careful to set the study up the right way and with a meaningful sample size.

This doesn’t mean it’s impossible to get quantitative data. But unless you have someone on your team who knows all about null hypotheses and p-values and statistical analysis, you might need to outsource quantitative research.

Plenty of businesses do this, but it’s pricey.

When you’re just starting out or you’re strapped for cash, qualitative data can get you valuable information—quickly and without gouging your wallet.

#4. Big vs. Small Sample Size

Another reason qualitative data is more accessible? It requires a smaller sample size to achieve meaningful results.

Even one person’s perspective brings value to a research project—ever heard of a case study?

The sweet spot depends on the purpose of the study, but for qualitative market research, somewhere between 10-40 respondents is a good number.

Any more than that and you risk reaching saturation. That’s when you keep getting results that echo each other and add nothing new to the research.

Quantitative data needs enough respondents to reach statistical significance without veering into saturation territory.

The ideal sample size number is usually higher than it is for qualitative data. But as with qualitative data, there’s no single, magic number. It all depends on statistical values like confidence level, population size, and margin of error.

Because it often requires a larger sample size, quantitative research can be more difficult for the average person to do on their own.

#5. Methods of Analysis

Running a study is just the first part of conducting qualitative and quantitative research.

After you’ve collected data, you have to study it. Find themes, patterns, consistencies, inconsistencies. Interpret and organize the numbers or survey responses or interview recordings. Tidy it all up into something you can draw conclusions from and apply to various situations.

This is called data analysis, and it’s done in completely different ways for qualitative vs. quantitative data.

For qualitative data, analysis includes:

- Data prep: Make all your qualitative data easy to access and read. This could mean organizing survey results by date, or transcribing interviews, or putting photographs into a slideshow format.

- Coding: No, not that kind. Think color coding, like you did for your notes in school. Assign colors or codes to specific attributes that make sense for your study—green for positive emotions, for instance, and red for angry emotions. Then code each of your responses.

- Thematic analysis: Organize your codes into themes and sub-themes, looking for the meaning—and relationships—within each one.

- Content analysis: Quantify the number of times certain words or concepts appear in your data. If this sounds suspiciously like quantitative research to you, it is. Sort of. It’s looking at qualitative data with a quantitative eye to identify any recurring themes or patterns.

- Narrative analysis: Look for similar stories and experiences and group them together. Study them and draw inferences from what they say.

- Interpret and document: As you organize and analyze your qualitative data, decide what the findings mean for you and your project.

You can often do qualitative data analysis manually or with tools like NVivo and ATLAS.ti. These tools help you organize, code, and analyze your subjective qualitative data.

Quantitative data analysis is a lot less subjective. Here’s how it generally goes:

- Data cleaning: Remove all inconsistencies and inaccuracies from your data. Check for duplicates, incorrect formatting (mistakenly writing a 1.00 value as 10.1, for example), and incomplete numbers.

- Summarize data with descriptive statistics: Use mean, median, mode, range, and standard deviation to summarize your data.

- Interpret the data with inferential statistics: This is where it gets more complicated. Instead of simply summarizing stats, you’ll now use complicated mathematical and statistical formulas and tests—t-tests, chi-square tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and correlation, for starters—to assign meaning to your data.

Researchers generally use sophisticated data analysis tools like RapidMiner and Tableau to help them do this work.

#6. Flexibility

Quantitative research tends to be less flexible than qualitative research. It relies on structured data collection methods, which researchers must set up well before the study begins.

This rigid structure is part of what makes quantitative data so reliable. But the downside here is that once you start the study, it’s hard to change anything without negatively affecting the results. If something unexpected comes up—or if new questions arise—researchers can’t easily change the scope of the study.

Qualitative research is a lot more flexible. This is why qualitative data can go deeper than quantitative data. If you’re interviewing someone and an interesting, unexpected topic comes up, you can immediately explore it.

Other qualitative research methods offer flexibility, too. Most big survey software brands allow you to build flexible surveys using branching and skip logic. These features let you customize which questions respondents see based on the answers they give.

This flexibility is unheard of in quantitative research. But even though it’s as flexible as an Olympic gymnast, qualitative data can be less reliable—and harder to validate.

#7. Reliability and Validity

Quantitative data is more reliable than qualitative data. Numbers can’t be massaged to fit a certain bias. If you replicate the study—in other words, run the exact same quantitative study two or more times—you should get nearly identical results each time. The same goes if another set of researchers runs the same study using the same methods.

This is what gives quantitative data that reliability factor.

There are a few key benefits here. First, reliable data means you can confidently make generalizations that apply to a larger population. It also means the data is valid and accurately measures whatever it is you’re trying to measure.

And finally, reliable data is trustworthy. Big industries like healthcare, marketing, and education frequently use quantitative data to make life-or-death decisions. The more reliable and trustworthy the data, the more confident these decision-makers can be when it’s time to make critical choices.

Unlike quantitative data, qualitative data isn’t overtly reliable. It’s not easy to replicate. If you send out the same qualitative survey on two separate occasions, you’ll get a new mix of responses. Your interpretations of the data might look different, too.

There’s still incredible value in qualitative data, of course—and there are ways to make sure the data is valid. These include:

- Member checking: Circling back with survey, interview, or focus group respondents to make sure you accurately summarized and interpreted their feedback.

- Triangulation: Using multiple data sources, methods, or researchers to cross-check and corroborate findings.

- Peer debriefing: Showing the data to peers—other researchers—so they can review the research process and its findings and provide feedback on both.

Whether you’re dealing with qualitative or quantitative data, transparency, accuracy, and validity are crucial. Focus on sourcing (or conducting) quantitative research that’s easy to replicate and qualitative research that’s been peer-reviewed.

With rock-solid data like this, you can make critical business decisions with confidence.

Make your website better. Instantly.

Keep reading about user experience.

dscout Review–The Good and Bad

dscout is a great tool for doing qualitative user research, like live interviews or diary studies. But it isn’t the best choice for everyone. If…

Out Of All Tips to Improve User Experience, 7 Are Legit

Figuring out the most effective ways to improve the user experience can be hard. There is tons of information out there, and it gets overwhelming…

Is Nominal Data Useful? Yes, In These Situations

Nominal data is descriptive information wherein rank and order don’t matter. Still confused? It helps to contrast nominal data with the other three main types…

What Is User Experience? Answers From 7 Top UX Designers

If you Google user experience the definition you’ll find is “the overall experience of a person using a product like a website or computer application,…

How to Do Each Qualitative Data Coding Type (All Steps)

Qualitative data coding is the process of organizing all the descriptive data you collect during a research project. It has nothing to do with computer…

7 Qualitative Data Examples and Why They Work

Qualitative data presents information using descriptive language, images, and videos instead of numbers. To help make sense of this type of data—as opposed to quantitative…

The 5 Best Usability Testing Tools Compared

Usability testing helps designers, product managers, and other teams figure out how easily users can use a website, app, or product. With these tools, user…

5 Qualitative Data Analysis Methods + When To Use Each

Qualitative data analysis is the work of organizing and interpreting descriptive data. Interview recordings, open-ended survey responses, and focus group observations all yield descriptive—qualitative—information. This…

The 5 Best UX Research Tools Compared

UX research tools help designers, product managers, and other teams understand users and how they interact with a company’s products and services. The tools provide…

Qualitative data is information you can describe with words rather than numbers. Quantitative data is information represented in a measurable way using numbers. One type…

6 Real Ways AI Has Improved the User Experience

It seems like every other company is bragging about their AI-enhanced user experiences. Consumers and the UX professionals responsible for designing great user experiences are…

12 Key UX Metrics: What They Mean + How To Calculate Each

UX metrics help identify where users struggle when using an app or website and where they are successful. The data collected helps designers, developers, and…

5 Key Principles Of Good Website Usability

Ease of use is a common expectation for a site to be considered well designed. Over the past few years, we have been used to…

20 Ways to Speed Up Your Website and Improve Conversion in 2024

Think that speeding up your website isn’t important? Big mistake. A one-second delay in page load time yields: Your site taking a few extra seconds to…

How to Do Usability Testing Right

User experience is one of the most important aspects of having a successful website, app, piece of software, or any other product that you’ve built. …

Over 300,000 websites use Crazy Egg to improve what's working, fix what isn't and test new ideas.

Last Updated on May 25, 2020

Integrations

What's new?

In-Product Prompts

Participant Management

Interview Studies

Prototype Testing

Card Sorting

Tree Testing

Live Website Testing

Automated Reports

Templates Gallery

Choose from our library of pre-built mazes to copy, customize, and share with your own users

Browse all templates

Financial Services

Tech & Software

Product Designers

Product Managers

User Researchers

By use case

Concept & Idea Validation

Wireframe & Usability Test

Content & Copy Testing

Feedback & Satisfaction

Content Hub

Educational resources for product, research and design teams

Explore all resources

Question Bank

Maze Research Success Hub

Guides & Reports

Help Center

Future of User Research Report

The Optimal Path Podcast

User Research

Aug 19, 2024 • 17 minutes read

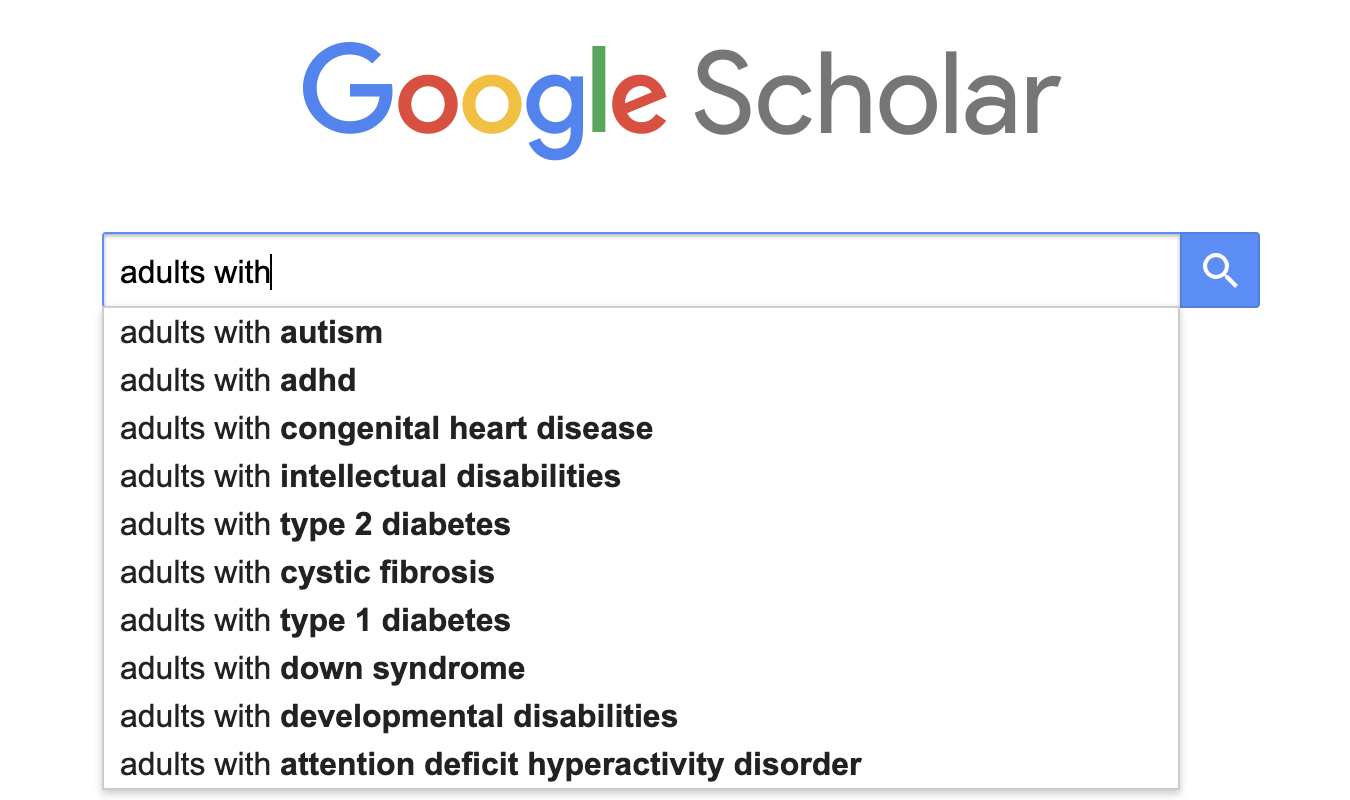

Qualitative research examples: How to unlock, rich, descriptive insights

Qualitative research uncovers in-depth user insights, but what does it look like? Here are seven methods and examples to help you get the data you need.

Armin Tanovic

Behind every what, there’s a why . Qualitative research is how you uncover that why. It enables you to connect with users and understand their thoughts, feelings, wants, needs, and pain points.

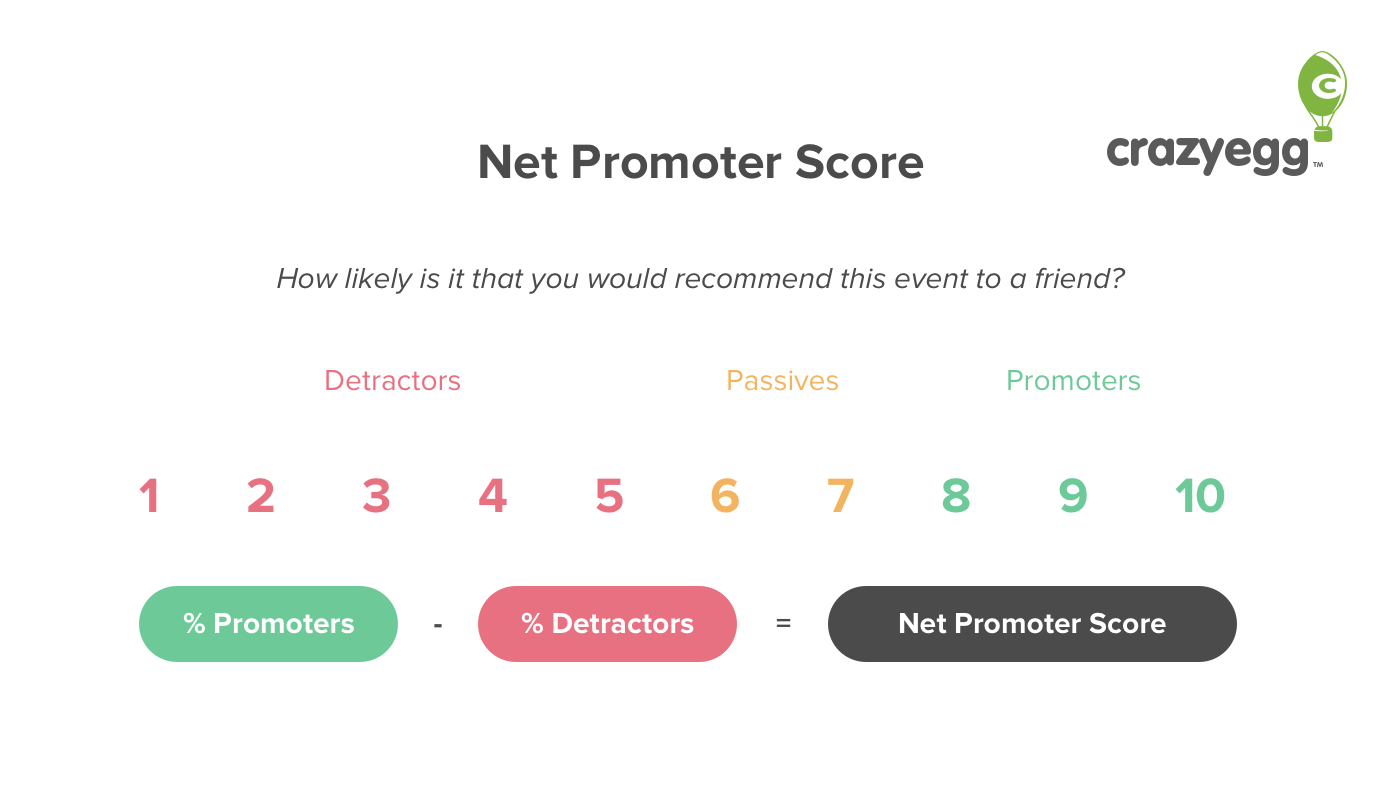

There’s many methods for conducting qualitative research, and many objectives it can help you pursue—you might want to explore ways to improve NPS scores, combat reduced customer retention, or understand (and recreate) the success behind a well-received product. The common thread? All these metrics impact your business, and qualitative research can help investigate and improve that impact.

In this article, we’ll take you through seven methods and examples of qualitative research, including when and how to use them.

Qualitative UX research made easy

Conduct qualitative research with Maze, analyze data instantly, and get rich, descriptive insights that drive decision-making.

7 Qualitative research methods: An overview

There are various qualitative UX research methods that can help you get in-depth, descriptive insights. Some are suited to specific phases of the design and development process, while others are more task-oriented.

Here’s our overview of the most common qualitative research methods. Keep reading for their use cases, and detailed examples of how to conduct them.

Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|

User interviews | |||

Focus groups | |||

Ethnographic research | |||

Qualitative observation | |||

Case study research | |||

Secondary research | |||

Open-ended surveys | to extract descriptive insights. |

1. User interviews

A user interview is a one-on-one conversation between a UX researcher, designer or Product Manager and a target user to understand their thoughts, perspectives, and feelings on a product or service. User interviews are a great way to get non-numerical data on individual experiences with your product, to gain a deeper understanding of user perspectives.

Interviews can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured . Structured interviews follow a strict interview script and can help you get answers to your planned questions, while semi and unstructured interviews are less rigid in their approach and typically lead to more spontaneous, user-centered insights.

When to use user interviews

Interviews are ideal when you want to gain an in-depth understanding of your users’ perspectives on your product or service, and why they feel a certain way.

Interviews can be used at any stage in the product design and development process, being particularly helpful during:

- The discovery phase: To better understand user needs, problems, and the context in which they use your product—revealing the best potential solutions

- The design phase: To get contextual feedback on mockups, wireframes, and prototypes, helping you pinpoint issues and the reasons behind them

- Post-launch: To assess if your product continues to meet users’ shifting expectations and understand why or why not

How to conduct user interviews: The basics

- Draft questions based on your research objectives

- Recruit relevant research participants and schedule interviews

- Conduct the interview and transcribe responses

- Analyze the interview responses to extract insights

- Use your findings to inform design, product, and business decisions

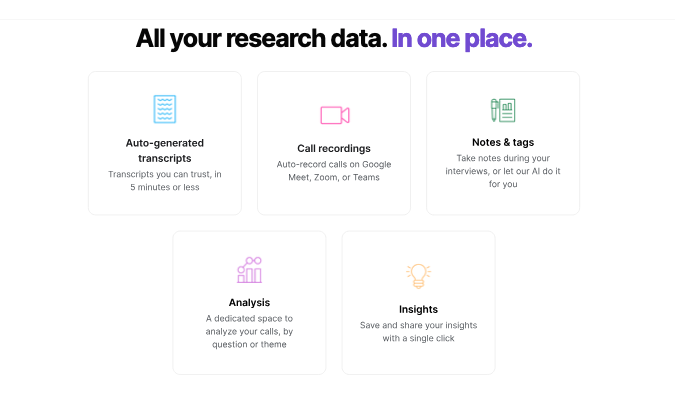

💡 A specialized user interview tool makes interviewing easier. With Maze Interview Studies , you can recruit, host, and analyze interviews all on one platform.

User interviews: A qualitative research example

Let’s say you’ve designed a recruitment platform, called Tech2Talent , that connects employers with tech talent. Before starting the design process, you want to clearly understand the pain points employers experience with existing recruitment tools'.

You draft a list of ten questions for a semi-structured interview for 15 different one-on-one interviews. As it’s semi-structured, you don’t expect to ask all the questions—the script serves as more of a guide.

One key question in your script is: “Have tech recruitment platforms helped you find the talent you need in the past?”

Most respondents answer with a resounding and passionate ‘no’ with one of them expanding:

“For our company, it’s been pretty hit or miss honestly. They let just about anyone make a profile and call themselves tech talent. It’s so hard sifting through serious candidates. I can’t see any of their achievements until I invest time setting up an interview.”

You begin to notice a pattern in your responses: recruitment tools often lack easily accessible details on talent profiles.

You’ve gained contextual feedback on why other recruitment platforms fail to solve user needs.

2. Focus groups

A focus group is a research method that involves gathering a small group of people—around five to ten users—to discuss a specific topic, such as their’ experience with your new product feature. Unlike user interviews, focus groups aim to capture the collective opinion of a wider market segment and encourage discussion among the group.

When to use focus groups

You should use focus groups when you need a deeper understanding of your users’ collective opinions. The dynamic discussion among participants can spark in-depth insights that might not emerge from regular interviews.

Focus groups can be used before, during, and after a product launch. They’re ideal:

- Throughout the problem discovery phase: To understand your user segment’s pain points and expectations, and generate product ideas

- Post-launch: To evaluate and understand the collective opinion of your product’s user experience

- When conducting market research: To grasp usage patterns, consumer perceptions, and market opportunities for your product

How to conduct focus group studies: The basics

- Draft prompts to spark conversation, or a series of questions based on your UX research objectives

- Find a group of five to ten users who are representative of your target audience (or a specific user segment) and schedule your focus group session

- Conduct the focus group by talking and listening to users, then transcribe responses

- Analyze focus group responses and extract insights

- Use your findings to inform design decisions

The number of participants can make it difficult to take notes or do manual transcriptions. We recommend using a transcription or a specialized UX research tool , such as Maze, that can automatically create ready-to-share reports and highlight key user insights.

Focus groups: A qualitative research example

You’re a UX researcher at FitMe , a fitness app that creates customized daily workouts for gym-goers. Unlike many other apps, FitMe takes into account the previous day’s workout and aims to create one that allows users to effectively rest different muscles.

However, FitMe has an issue. Users are generating workouts but not completing them. They’re accessing the app, taking the necessary steps to get a workout for the day, but quitting at the last hurdle.

Time to talk to users.

You organize a focus group to get to the root of the drop-off issue. You invite five existing users, all of whom have dropped off at the exact point you’re investigating, and ask them questions to uncover why.

A dialog develops:

Participant 1: “Sometimes I’ll get a workout that I just don’t want to do. Sure, it’s a good workout—but I just don’t want to physically do it. I just do my own thing when that happens.”

Participant 2: “Same here, some of them are so boring. I go to the gym because I love it. It’s an escape.”

Participant 3: “Right?! I get that the app generates the best one for me on that specific day, but I wish I could get a couple of options.”

Participant 4: “I’m the same, there are some exercises I just refuse to do. I’m not coming to the gym to do things I dislike.”

Conducting the focus groups and reviewing the transcripts, you realize that users want options. A workout that works for one gym-goer doesn’t necessarily work for the next.

A possible solution? Adding the option to generate a new workout (that still considers previous workouts)and the ability to blacklist certain exercises, like burpees.