An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Prev Med

Qualitative Methods in Health Care Research

Vishnu renjith.

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Royal College of Surgeons Ireland - Bahrain (RCSI Bahrain), Al Sayh Muharraq Governorate, Bahrain

Renjulal Yesodharan

1 Department of Mental Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Judith A. Noronha

2 Department of OBG Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Elissa Ladd

3 School of Nursing, MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, USA

Anice George

4 Department of Child Health Nursing, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate robust evidence about important issues in the fields of medicine and healthcare. Qualitative research has ample possibilities within the arena of healthcare research. This article aims to inform healthcare professionals regarding qualitative research, its significance, and applicability in the field of healthcare. A wide variety of phenomena that cannot be explained using the quantitative approach can be explored and conveyed using a qualitative method. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research. The greatest strength of the qualitative research approach lies in the richness and depth of the healthcare exploration and description it makes. In health research, these methods are considered as the most humanistic and person-centered way of discovering and uncovering thoughts and actions of human beings.

Introduction

Healthcare research is a systematic inquiry intended to generate trustworthy evidence about issues in the field of medicine and healthcare. The three principal approaches to health research are the quantitative, the qualitative, and the mixed methods approach. The quantitative research method uses data, which are measures of values and counts and are often described using statistical methods which in turn aids the researcher to draw inferences. Qualitative research incorporates the recording, interpreting, and analyzing of non-numeric data with an attempt to uncover the deeper meanings of human experiences and behaviors. Mixed methods research, the third methodological approach, involves collection and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative information with an objective to solve different but related questions, or at times the same questions.[ 1 , 2 ]

In healthcare, qualitative research is widely used to understand patterns of health behaviors, describe lived experiences, develop behavioral theories, explore healthcare needs, and design interventions.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] Because of its ample applications in healthcare, there has been a tremendous increase in the number of health research studies undertaken using qualitative methodology.[ 4 , 5 ] This article discusses qualitative research methods, their significance, and applicability in the arena of healthcare.

Qualitative Research

Diverse academic and non-academic disciplines utilize qualitative research as a method of inquiry to understand human behavior and experiences.[ 6 , 7 ] According to Munhall, “Qualitative research involves broadly stated questions about human experiences and realities, studied through sustained contact with the individual in their natural environments and producing rich, descriptive data that will help us to understand those individual's experiences.”[ 8 ]

Significance of Qualitative Research

The qualitative method of inquiry examines the 'how' and 'why' of decision making, rather than the 'when,' 'what,' and 'where.'[ 7 ] Unlike quantitative methods, the objective of qualitative inquiry is to explore, narrate, and explain the phenomena and make sense of the complex reality. Health interventions, explanatory health models, and medical-social theories could be developed as an outcome of qualitative research.[ 9 ] Understanding the richness and complexity of human behavior is the crux of qualitative research.

Differences between Quantitative and Qualitative Research

The quantitative and qualitative forms of inquiry vary based on their underlying objectives. They are in no way opposed to each other; instead, these two methods are like two sides of a coin. The critical differences between quantitative and qualitative research are summarized in Table 1 .[ 1 , 10 , 11 ]

Differences between quantitative and qualitative research

| Areas | Quantitative Research | Qualitative Research |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of reality | Assumes there is a single reality. | Assumes existence of dynamic and multiple reality. |

| Goal | Test and confirm hypotheses. | Explore and understand phenomena. |

| Data collection methods | Highly structured methods like questionnaires, inventories and scales. | Semi structured like in-depth interviews, observations and focus group discussions. |

| Design | Predetermined and rigid design. | Flexible and emergent design. |

| Reasoning | Deductive process to test the hypothesis. | Primarily inductive to develop the theory or hypothesis. |

| Focus | Concerned with the outcomes and prediction of the causal relationships. | Concerned primarily with process, rather than outcomes or products. |

| Sampling | Rely largely on random sampling methods. | Based on purposive sampling methods. |

| Sample size determination | Involves a-priori sample size calculation. | Collect data until data saturation is achieved. |

| Sample size | Relatively large. | Small sample size but studied in-depth. |

| Data analysis | Variable based and use of statistical or mathematical methods. | Case based and use non statistical descriptive or interpretive methods. |

Qualitative Research Questions and Purpose Statements

Qualitative questions are exploratory and are open-ended. A well-formulated study question forms the basis for developing a protocol, guides the selection of design, and data collection methods. Qualitative research questions generally involve two parts, a central question and related subquestions. The central question is directed towards the primary phenomenon under study, whereas the subquestions explore the subareas of focus. It is advised not to have more than five to seven subquestions. A commonly used framework for designing a qualitative research question is the 'PCO framework' wherein, P stands for the population under study, C stands for the context of exploration, and O stands for the outcome/s of interest.[ 12 ] The PCO framework guides researchers in crafting a focused study question.

Example: In the question, “What are the experiences of mothers on parenting children with Thalassemia?”, the population is “mothers of children with Thalassemia,” the context is “parenting children with Thalassemia,” and the outcome of interest is “experiences.”

The purpose statement specifies the broad focus of the study, identifies the approach, and provides direction for the overall goal of the study. The major components of a purpose statement include the central phenomenon under investigation, the study design and the population of interest. Qualitative research does not require a-priori hypothesis.[ 13 , 14 , 15 ]

Example: Borimnejad et al . undertook a qualitative research on the lived experiences of women suffering from vitiligo. The purpose of this study was, “to explore lived experiences of women suffering from vitiligo using a hermeneutic phenomenological approach.” [ 16 ]

Review of the Literature

In quantitative research, the researchers do an extensive review of scientific literature prior to the commencement of the study. However, in qualitative research, only a minimal literature search is conducted at the beginning of the study. This is to ensure that the researcher is not influenced by the existing understanding of the phenomenon under the study. The minimal literature review will help the researchers to avoid the conceptual pollution of the phenomenon being studied. Nonetheless, an extensive review of the literature is conducted after data collection and analysis.[ 15 ]

Reflexivity

Reflexivity refers to critical self-appraisal about one's own biases, values, preferences, and preconceptions about the phenomenon under investigation. Maintaining a reflexive diary/journal is a widely recognized way to foster reflexivity. According to Creswell, “Reflexivity increases the credibility of the study by enhancing more neutral interpretations.”[ 7 ]

Types of Qualitative Research Designs

The qualitative research approach encompasses a wide array of research designs. The words such as types, traditions, designs, strategies of inquiry, varieties, and methods are used interchangeably. The major types of qualitative research designs are narrative research, phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, historical research, and case study research.[ 1 , 7 , 10 ]

Narrative research

Narrative research focuses on exploring the life of an individual and is ideally suited to tell the stories of individual experiences.[ 17 ] The purpose of narrative research is to utilize 'story telling' as a method in communicating an individual's experience to a larger audience.[ 18 ] The roots of narrative inquiry extend to humanities including anthropology, literature, psychology, education, history, and sociology. Narrative research encompasses the study of individual experiences and learning the significance of those experiences. The data collection procedures include mainly interviews, field notes, letters, photographs, diaries, and documents collected from one or more individuals. Data analysis involves the analysis of the stories or experiences through “re-storying of stories” and developing themes usually in chronological order of events. Rolls and Payne argued that narrative research is a valuable approach in health care research, to gain deeper insight into patient's experiences.[ 19 ]

Example: Karlsson et al . undertook a narrative inquiry to “explore how people with Alzheimer's disease present their life story.” Data were collected from nine participants. They were asked to describe about their life experiences from childhood to adulthood, then to current life and their views about the future life. [ 20 ]

Phenomenological research

Phenomenology is a philosophical tradition developed by German philosopher Edmond Husserl. His student Martin Heidegger did further developments in this methodology. It defines the 'essence' of individual's experiences regarding a certain phenomenon.[ 1 ] The methodology has its origin from philosophy, psychology, and education. The purpose of qualitative research is to understand the people's everyday life experiences and reduce it into the central meaning or the 'essence of the experience'.[ 21 , 22 ] The unit of analysis of phenomenology is the individuals who have had similar experiences of the phenomenon. Interviews with individuals are mainly considered for the data collection, though, documents and observations are also useful. Data analysis includes identification of significant meaning elements, textural description (what was experienced), structural description (how was it experienced), and description of 'essence' of experience.[ 1 , 7 , 21 ] The phenomenological approach is further divided into descriptive and interpretive phenomenology. Descriptive phenomenology focuses on the understanding of the essence of experiences and is best suited in situations that need to describe the lived phenomenon. Hermeneutic phenomenology or Interpretive phenomenology moves beyond the description to uncover the meanings that are not explicitly evident. The researcher tries to interpret the phenomenon, based on their judgment rather than just describing it.[ 7 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]

Example: A phenomenological study conducted by Cornelio et al . aimed at describing the lived experiences of mothers in parenting children with leukemia. Data from ten mothers were collected using in-depth semi-structured interviews and were analyzed using Husserl's method of phenomenology. Themes such as “pivotal moment in life”, “the experience of being with a seriously ill child”, “having to keep distance with the relatives”, “overcoming the financial and social commitments”, “responding to challenges”, “experience of faith as being key to survival”, “health concerns of the present and future”, and “optimism” were derived. The researchers reported the essence of the study as “chronic illness such as leukemia in children results in a negative impact on the child and on the mother.” [ 25 ]

Grounded Theory Research

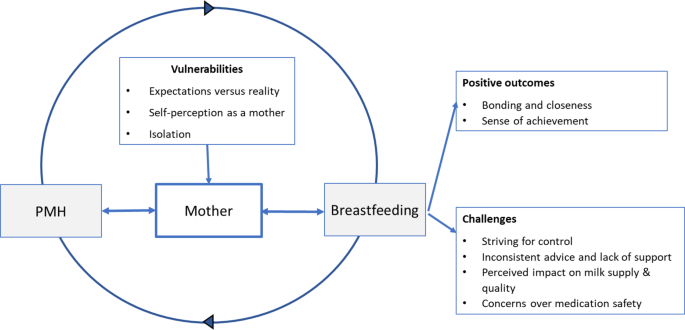

Grounded theory has its base in sociology and propagated by two sociologists, Barney Glaser, and Anselm Strauss.[ 26 ] The primary purpose of grounded theory is to discover or generate theory in the context of the social process being studied. The major difference between grounded theory and other approaches lies in its emphasis on theory generation and development. The name grounded theory comes from its ability to induce a theory grounded in the reality of study participants.[ 7 , 27 ] Data collection in grounded theory research involves recording interviews from many individuals until data saturation. Constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling, theoretical coding, and theoretical saturation are unique features of grounded theory research.[ 26 , 27 , 28 ] Data analysis includes analyzing data through 'open coding,' 'axial coding,' and 'selective coding.'[ 1 , 7 ] Open coding is the first level of abstraction, and it refers to the creation of a broad initial range of categories, axial coding is the procedure of understanding connections between the open codes, whereas selective coding relates to the process of connecting the axial codes to formulate a theory.[ 1 , 7 ] Results of the grounded theory analysis are supplemented with a visual representation of major constructs usually in the form of flow charts or framework diagrams. Quotations from the participants are used in a supportive capacity to substantiate the findings. Strauss and Corbin highlights that “the value of the grounded theory lies not only in its ability to generate a theory but also to ground that theory in the data.”[ 27 ]

Example: Williams et al . conducted a grounded theory research to explore the nature of relationship between the sense of self and the eating disorders. Data were collected form 11 women with a lifetime history of Anorexia Nervosa and were analyzed using the grounded theory methodology. Analysis led to the development of a theoretical framework on the nature of the relationship between the self and Anorexia Nervosa. [ 29 ]

Ethnographic research

Ethnography has its base in anthropology, where the anthropologists used it for understanding the culture-specific knowledge and behaviors. In health sciences research, ethnography focuses on narrating and interpreting the health behaviors of a culture-sharing group. 'Culture-sharing group' in an ethnography represents any 'group of people who share common meanings, customs or experiences.' In health research, it could be a group of physicians working in rural care, a group of medical students, or it could be a group of patients who receive home-based rehabilitation. To understand the cultural patterns, researchers primarily observe the individuals or group of individuals for a prolonged period of time.[ 1 , 7 , 30 ] The scope of ethnography can be broad or narrow depending on the aim. The study of more general cultural groups is termed as macro-ethnography, whereas micro-ethnography focuses on more narrowly defined cultures. Ethnography is usually conducted in a single setting. Ethnographers collect data using a variety of methods such as observation, interviews, audio-video records, and document reviews. A written report includes a detailed description of the culture sharing group with emic and etic perspectives. When the researcher reports the views of the participants it is called emic perspectives and when the researcher reports his or her views about the culture, the term is called etic.[ 7 ]

Example: The aim of the ethnographic study by LeBaron et al . was to explore the barriers to opioid availability and cancer pain management in India. The researchers collected data from fifty-nine participants using in-depth semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and document review. The researchers identified significant barriers by open coding and thematic analysis of the formal interview. [ 31 ]

Historical research

Historical research is the “systematic collection, critical evaluation, and interpretation of historical evidence”.[ 1 ] The purpose of historical research is to gain insights from the past and involves interpreting past events in the light of the present. The data for historical research are usually collected from primary and secondary sources. The primary source mainly includes diaries, first hand information, and writings. The secondary sources are textbooks, newspapers, second or third-hand accounts of historical events and medical/legal documents. The data gathered from these various sources are synthesized and reported as biographical narratives or developmental perspectives in chronological order. The ideas are interpreted in terms of the historical context and significance. The written report describes 'what happened', 'how it happened', 'why it happened', and its significance and implications to current clinical practice.[ 1 , 10 ]

Example: Lubold (2019) analyzed the breastfeeding trends in three countries (Sweden, Ireland, and the United States) using a historical qualitative method. Through analysis of historical data, the researcher found that strong family policies, adherence to international recommendations and adoption of baby-friendly hospital initiative could greatly enhance the breastfeeding rates. [ 32 ]

Case study research

Case study research focuses on the description and in-depth analysis of the case(s) or issues illustrated by the case(s). The design has its origin from psychology, law, and medicine. Case studies are best suited for the understanding of case(s), thus reducing the unit of analysis into studying an event, a program, an activity or an illness. Observations, one to one interviews, artifacts, and documents are used for collecting the data, and the analysis is done through the description of the case. From this, themes and cross-case themes are derived. A written case study report includes a detailed description of one or more cases.[ 7 , 10 ]

Example: Perceptions of poststroke sexuality in a woman of childbearing age was explored using a qualitative case study approach by Beal and Millenbrunch. Semi structured interview was conducted with a 36- year mother of two children with a history of Acute ischemic stroke. The data were analyzed using an inductive approach. The authors concluded that “stroke during childbearing years may affect a woman's perception of herself as a sexual being and her ability to carry out gender roles”. [ 33 ]

Sampling in Qualitative Research

Qualitative researchers widely use non-probability sampling techniques such as purposive sampling, convenience sampling, quota sampling, snowball sampling, homogeneous sampling, maximum variation sampling, extreme (deviant) case sampling, typical case sampling, and intensity sampling. The selection of a sampling technique depends on the nature and needs of the study.[ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ] The four widely used sampling techniques are convenience sampling, purposive sampling, snowball sampling, and intensity sampling.

Convenience sampling

It is otherwise called accidental sampling, where the researchers collect data from the subjects who are selected based on accessibility, geographical proximity, ease, speed, and or low cost.[ 34 ] Convenience sampling offers a significant benefit of convenience but often accompanies the issues of sample representation.

Purposive sampling

Purposive or purposeful sampling is a widely used sampling technique.[ 35 ] It involves identifying a population based on already established sampling criteria and then selecting subjects who fulfill that criteria to increase the credibility. However, choosing information-rich cases is the key to determine the power and logic of purposive sampling in a qualitative study.[ 1 ]

Snowball sampling

The method is also known as 'chain referral sampling' or 'network sampling.' The sampling starts by having a few initial participants, and the researcher relies on these early participants to identify additional study participants. It is best adopted when the researcher wishes to study the stigmatized group, or in cases, where findings of participants are likely to be difficult by ordinary means. Respondent ridden sampling is an improvised version of snowball sampling used to find out the participant from a hard-to-find or hard-to-study population.[ 37 , 38 ]

Intensity sampling

The process of identifying information-rich cases that manifest the phenomenon of interest is referred to as intensity sampling. It requires prior information, and considerable judgment about the phenomenon of interest and the researcher should do some preliminary investigations to determine the nature of the variation. Intensity sampling will be done once the researcher identifies the variation across the cases (extreme, average and intense) and picks the intense cases from them.[ 40 ]

Deciding the Sample Size

A-priori sample size calculation is not undertaken in the case of qualitative research. Researchers collect the data from as many participants as possible until they reach the point of data saturation. Data saturation or the point of redundancy is the stage where the researcher no longer sees or hears any new information. Data saturation gives the idea that the researcher has captured all possible information about the phenomenon of interest. Since no further information is being uncovered as redundancy is achieved, at this point the data collection can be stopped. The objective here is to get an overall picture of the chronicle of the phenomenon under the study rather than generalization.[ 1 , 7 , 41 ]

Data Collection in Qualitative Research

The various strategies used for data collection in qualitative research includes in-depth interviews (individual or group), focus group discussions (FGDs), participant observation, narrative life history, document analysis, audio materials, videos or video footage, text analysis, and simple observation. Among all these, the three popular methods are the FGDs, one to one in-depth interviews and the participant observation.

FGDs are useful in eliciting data from a group of individuals. They are normally built around a specific topic and are considered as the best approach to gather data on an entire range of responses to a topic.[ 42 Group size in an FGD ranges from 6 to 12. Depending upon the nature of participants, FGDs could be homogeneous or heterogeneous.[ 1 , 14 ] One to one in-depth interviews are best suited to obtain individuals' life histories, lived experiences, perceptions, and views, particularly while exporting topics of sensitive nature. In-depth interviews can be structured, unstructured, or semi-structured. However, semi-structured interviews are widely used in qualitative research. Participant observations are suitable for gathering data regarding naturally occurring behaviors.[ 1 ]

Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

Various strategies are employed by researchers to analyze data in qualitative research. Data analytic strategies differ according to the type of inquiry. A general content analysis approach is described herewith. Data analysis begins by transcription of the interview data. The researcher carefully reads data and gets a sense of the whole. Once the researcher is familiarized with the data, the researcher strives to identify small meaning units called the 'codes.' The codes are then grouped based on their shared concepts to form the primary categories. Based on the relationship between the primary categories, they are then clustered into secondary categories. The next step involves the identification of themes and interpretation to make meaning out of data. In the results section of the manuscript, the researcher describes the key findings/themes that emerged. The themes can be supported by participants' quotes. The analytical framework used should be explained in sufficient detail, and the analytic framework must be well referenced. The study findings are usually represented in a schematic form for better conceptualization.[ 1 , 7 ] Even though the overall analytical process remains the same across different qualitative designs, each design such as phenomenology, ethnography, and grounded theory has design specific analytical procedures, the details of which are out of the scope of this article.

Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS)

Until recently, qualitative analysis was done either manually or with the help of a spreadsheet application. Currently, there are various software programs available which aid researchers to manage qualitative data. CAQDAS is basically data management tools and cannot analyze the qualitative data as it lacks the ability to think, reflect, and conceptualize. Nonetheless, CAQDAS helps researchers to manage, shape, and make sense of unstructured information. Open Code, MAXQDA, NVivo, Atlas.ti, and Hyper Research are some of the widely used qualitative data analysis software.[ 14 , 43 ]

Reporting Guidelines

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) is the widely used reporting guideline for qualitative research. This 32-item checklist assists researchers in reporting all the major aspects related to the study. The three major domains of COREQ are the 'research team and reflexivity', 'study design', and 'analysis and findings'.[ 44 , 45 ]

Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Research

Various scales are available to critical appraisal of qualitative research. The widely used one is the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Checklist developed by CASP network, UK. This 10-item checklist evaluates the quality of the study under areas such as aims, methodology, research design, ethical considerations, data collection, data analysis, and findings.[ 46 ]

Ethical Issues in Qualitative Research

A qualitative study must be undertaken by grounding it in the principles of bioethics such as beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice. Protecting the participants is of utmost importance, and the greatest care has to be taken while collecting data from a vulnerable research population. The researcher must respect individuals, families, and communities and must make sure that the participants are not identifiable by their quotations that the researchers include when publishing the data. Consent for audio/video recordings must be obtained. Approval to be in FGDs must be obtained from the participants. Researchers must ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of the transcripts/audio-video records/photographs/other data collected as a part of the study. The researchers must confirm their role as advocates and proceed in the best interest of all participants.[ 42 , 47 , 48 ]

Rigor in Qualitative Research

The demonstration of rigor or quality in the conduct of the study is essential for every research method. However, the criteria used to evaluate the rigor of quantitative studies are not be appropriate for qualitative methods. Lincoln and Guba (1985) first outlined the criteria for evaluating the qualitative research often referred to as “standards of trustworthiness of qualitative research”.[ 49 ] The four components of the criteria are credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Credibility refers to confidence in the 'truth value' of the data and its interpretation. It is used to establish that the findings are true, credible and believable. Credibility is similar to the internal validity in quantitative research.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] The second criterion to establish the trustworthiness of the qualitative research is transferability, Transferability refers to the degree to which the qualitative results are applicability to other settings, population or contexts. This is analogous to the external validity in quantitative research.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Lincoln and Guba recommend authors provide enough details so that the users will be able to evaluate the applicability of data in other contexts.[ 49 ] The criterion of dependability refers to the assumption of repeatability or replicability of the study findings and is similar to that of reliability in quantitative research. The dependability question is 'Whether the study findings be repeated of the study is replicated with the same (similar) cohort of participants, data coders, and context?'[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Confirmability, the fourth criteria is analogous to the objectivity of the study and refers the degree to which the study findings could be confirmed or corroborated by others. To ensure confirmability the data should directly reflect the participants' experiences and not the bias, motivations, or imaginations of the inquirer.[ 1 , 50 , 51 ] Qualitative researchers should ensure that the study is conducted with enough rigor and should report the measures undertaken to enhance the trustworthiness of the study.

Conclusions

Qualitative research studies are being widely acknowledged and recognized in health care practice. This overview illustrates various qualitative methods and shows how these methods can be used to generate evidence that informs clinical practice. Qualitative research helps to understand the patterns of health behaviors, describe illness experiences, design health interventions, and develop healthcare theories. The ultimate strength of the qualitative research approach lies in the richness of the data and the descriptions and depth of exploration it makes. Hence, qualitative methods are considered as the most humanistic and person-centered way of discovering and uncovering thoughts and actions of human beings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 10 October 2019

An integrative review on methodological considerations in mental health research – design, sampling, data collection procedure and quality assurance

- Eric Badu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0593-3550 1 ,

- Anthony Paul O’Brien 2 &

- Rebecca Mitchell 3

Archives of Public Health volume 77 , Article number: 37 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

20 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Several typologies and guidelines are available to address the methodological and practical considerations required in mental health research. However, few studies have actually attempted to systematically identify and synthesise these considerations. This paper provides an integrative review that identifies and synthesises the available research evidence on mental health research methodological considerations.

A search of the published literature was conducted using EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science, and Scopus. The search was limited to papers published in English for the timeframe 2000–2018. Using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, three reviewers independently screened the retrieved papers. A data extraction form was used to extract data from the included papers.

Of 27 papers meeting the inclusion criteria, 13 focused on qualitative research, 8 mixed methods and 6 papers focused on quantitative methodology. A total of 14 papers targeted global mental health research, with 2 papers each describing studies in Germany, Sweden and China. The review identified several methodological considerations relating to study design, methods, data collection, and quality assurance. Methodological issues regarding the study design included assembling team members, familiarisation and sharing information on the topic, and seeking the contribution of team members. Methodological considerations to facilitate data collection involved adequate preparation prior to fieldwork, appropriateness and adequacy of the sampling and data collection approach, selection of consumers, the social or cultural context, practical and organisational skills; and ethical and sensitivity issues.

The evidence confirms that studies on methodological considerations in conducting mental health research largely focus on qualitative studies in a transcultural setting, as well as recommendations derived from multi-site surveys. Mental health research should adequately consider the methodological issues around study design, sampling, data collection procedures and quality assurance in order to maintain the quality of data collection.

Peer Review reports

In the past decades there has been considerable attention on research methods to facilitate studies in various academic fields, such as public health, education, humanities, behavioural and social sciences [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. These research methodologies have generally focused on the two major research pillars known as quantitative or qualitative research. In recent years, researchers conducting mental health research appear to be either employing both qualitative and quantitative research methods separately, or mixed methods approaches to triangulate and validate findings [ 5 , 6 ].

A combination of study designs has been utilised to answer research questions associated with mental health services and consumer outcomes [ 7 , 8 ]. Study designs in the public health and clinical domains, for example, have largely focused on observational studies (non-interventional) and experimental research (interventional) [ 1 , 3 , 9 ]. Observational design in non-interventional research requires the investigator to simply observe, record, classify, count and analyse the data [ 1 , 2 , 10 ]. This design is different from the observational approaches used in social science research, which may involve observing (participant and non- participant) phenomena in the fieldwork [ 1 ]. Furthermore, the observational study has been categorized into five types, namely cross-sectional design, case-control studies, cohort studies, case report and case series studies [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. The cross-sectional design is used to measure the occurrence of a condition at a one-time point, sometimes referred to as a prevalence study. This approach of conducting research is relatively quick and easy but does not permit a distinction between cause and effect [ 1 ]. Conversely, the case-control is a design that examines the relationship between an attribute and a disease by comparing those with and without the disease [ 1 , 2 , 12 ]. In addition, the case-control design is usually retrospective and aims to identify predictors of a particular outcome. This type of design is relevant when investigating rare or chronic diseases which may result from long-term exposure to particular risk factors [ 10 ]. Cohort studies measure the relationship between exposure to a factor and the probability of the occurrence of a disease [ 1 , 10 ]. In a case series design, medical records are reviewed for exposure to determinants of disease and outcomes. More importantly, case series and case reports are often used as preliminary research to provide information on key clinical issues [ 12 ].

The interventional study design describes a research approach that applies clinical care to evaluate treatment effects on outcomes [ 13 ]. Several previous studies have explained the various forms of experimental study design used in public health and clinical research [ 14 , 15 ]. In particular, experimental studies have been categorized into randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized controlled trials, and quasi-experimental designs [ 14 ]. The randomized trial is a comparative study where participants are randomly assigned to one of two groups. This research examines a comparison between a group receiving treatment and a control group receiving treatment as usual or receiving a placebo. Herein, the exposure to the intervention is determined by random allocation [ 16 , 17 ].

Recently, research methodologists have given considerable attention to the development of methodologies to conduct research in vulnerable populations. Vulnerable population research, such as with mental health consumers often involves considering the challenges associated with sampling (selecting marginalized participants), collecting data and analysing it, as well as research engagement. Consequently, several empirical studies have been undertaken to document the methodological issues and challenges in research involving marginalized populations. In particular, these studies largely addresses the typologies and practical guidelines for conducting empirical studies in mental health. Despite the increasing evidence, however, only a few studies have yet attempted to systematically identify and synthesise the methodological considerations in conducting mental health research from the perspective of consumers.

A preliminary search using the search engines Medline, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus Index and EMBASE identified only two reviews of mental health based research. Among these two papers, one focused on the various types of mixed methods used in mental health research [ 18 ], whilst the other paper, focused on the role of qualitative studies in mental health research involving mixed methods [ 19 ]. Even though the latter two studies attempted to systematically review mixed methods mental health research, this integrative review is unique, as it collectively synthesises the design, data collection, sampling, and quality assurance issues together, which has not been previously attempted.

This paper provides an integrative review addressing the available evidence on mental health research methodological considerations. The paper also synthesises evidence on the methods, study designs, data collection procedures, analyses and quality assurance measures. Identifying and synthesising evidence on the conduct of mental health research has relevance to clinicians and academic researchers where the evidence provides a guide regarding the methodological issues involved when conducting research in the mental health domain. Additionally, the synthesis can inform clinicians and academia about the gaps in the literature related to methodological considerations.

Methodology

An integrative review was conducted to synthesise the available evidence on mental health research methodological considerations. To guide the review, the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of mental health has been utilised. The WHO defines mental health as: “a state of well-being, in which the individual realises his or her own potentials, ability to cope with the normal stresses of life, functionality and work productivity, as well as the ability to contribute effectively in community life” [ 20 ]. The integrative review enabled the simultaneous inclusion of diverse methodologies (i.e., experimental and non-experimental research) and varied perspectives to fully understand a phenomenon of concern [ 21 , 22 ]. The review also uses diverse data sources to develop a holistic understanding of methodological considerations in mental health research. The methodology employed involves five stages: 1) problem identification (ensuring that the research question and purpose are clearly defined); 2) literature search (incorporating a comprehensive search strategy); 3) data evaluation; 4) data analysis (data reduction, display, comparison and conclusions) and; 5) presentation (synthesising findings in a model or theory and describing the implications for practice, policy and further research) [ 21 ].

Inclusion criteria

The integrative review focused on methodological issues in mental health research. This included core areas such as study design and methods, particularly qualitative, quantitative or both. The review targeted papers that addressed study design, sampling, data collection procedures, quality assurance and the data analysis process. More specifically, the included papers addressed methodological issues on empirical studies in mental health research. The methodological issues in this context are not limited to a particular mental illness. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed articles published in the English Language, from January 2000 to July 2018.

Exclusion criteria

Articles that were excluded were based purely on general health services or clinical effectiveness of a particular intervention with no connection to mental health research. Articles were also excluded when it addresses non-methodological issues. Other general exclusion criteria were book chapters, conference abstracts, papers that present opinion, editorials, commentaries and clinical case reviews.

Search strategy and selection procedure

The search of published articles was conducted from six electronic databases, namely EMBASE, CINAHL (EBSCO), Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO and Medline. We developed a search strategy based on the recommended guidelines by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [ 23 ]. Specifically, a three-step search strategy was utilised to conduct the search for information (see Table 1 ). An initial limited search was conducted in Medline and Embase (see Table 1 ). We analysed the text words contained in the title and abstract and of the index terms from the initial search results [ 23 ]. A second search using all identified keywords and index terms was then repeated across all remaining five databases (see Table 1 ). Finally, the reference lists of all eligible studies were manually hand searched [ 23 ].

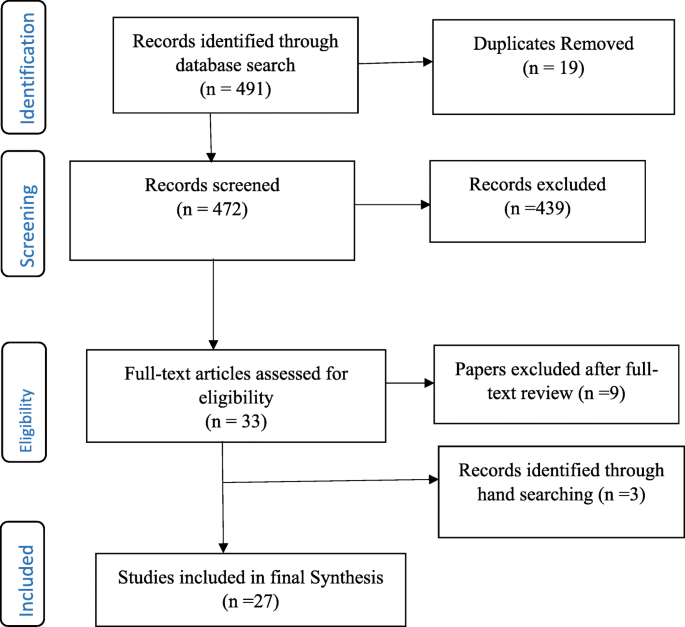

The selection of eligible articles adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [ 24 ] (see Fig. 1 ). Firstly, three authors independently screened the titles of articles that were retrieved and then approved those meeting the selection criteria. The authors reviewed all the titles and abstracts and agreed on those needing full-text screening. E.B (Eric Badu) conducted the initial screening of titles and abstracts. A.P.O’B (Anthony Paul O’Brien) and R.M (Rebecca Mitchell) conducted the second screening of titles and abstracts of all the identified papers. The authors (E.B, A.P.O’B and R.M) conducted full-text screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Flow Chart of studies included in the review

Data management and extraction

The integrative review used Endnote ×8 to screen and handle duplicate references. A predefined data extraction form was developed to extract data from all included articles (see Additional file 1 ). The data extraction form was developed according to Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [ 23 ] and Cochrane [ 24 ] manuals, as well as the literature associated with concepts and methods in mental health research. The data extraction form was categorised into sub-sections, such as study details (citation, year of publication, author, contact details of lead author, and funder/sponsoring organisation, publication type), objective of the paper, primary subject area of the paper (study design, methods, sampling, data collection, data analysis, quality assurance). The data extraction form also had a section on additional information on methodological consideration, recommendations and other potential references. The authors extracted results of the included papers in numerical and textual format [ 23 ]. EB (Eric Badu) conducted the data extraction, A.P.O’B (Anthony Paul O’Brien) and R.M (Rebecca Mitchell), conducted the second review of the extracted data.

Data synthesis

Content analysis was used to synthesise the extracted data. The content analysis process involved several stages which involved noting patterns and themes, seeing plausibility, clustering, counting, making contrasts and comparisons, discerning common and unusual patterns, subsuming particulars into general, noting relations between variability, finding intervening factors and building a logical chain of evidence [ 21 ] (see Table 2 ).

Study characteristics

The integrative review identified a total of 491 records from all databases, after which 19 duplicates were removed. Out of this, 472 titles and abstracts were assessed for eligibility, after which 439 articles were excluded. Articles not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded. Specifically, papers excluded were those that did not address methodological issues as well as papers addressing methodological consideration in other disciplines. A total of 33 full-text articles were assessed – 9 articles were further excluded, whilst an additional 3 articles were identified from reference lists. Overall, 27 articles were included in the final synthesis (see Fig. 1 ). Of the total included papers, 12 contained qualitative research, 9 were mixed methods (both qualitative and quantitative) and 6 papers focused on quantitative data. Conversely, a total of 14 papers targeted global mental health research and 2 papers each describing studies in Germany, Sweden and China. The papers addressed different methodological issues, such as study design, methods, data collection, and analysis as well as quality assurance (see Table 3 ).

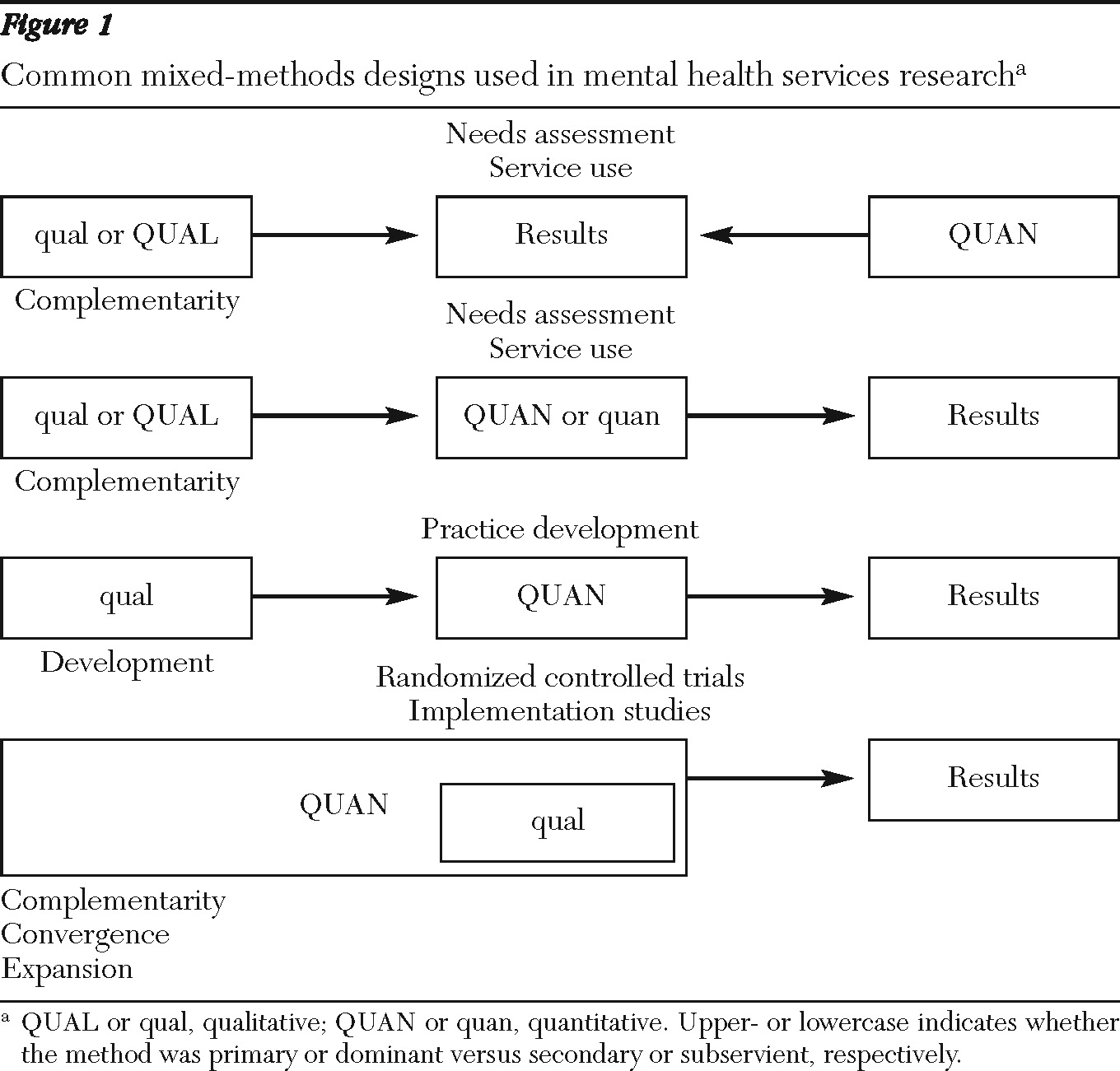

Mixed methods design in mental health research

Mixed methods research is defined as a research process where the elements of qualitative and quantitative research are combined in the design, data collection, and its triangulation and validation [ 48 ]. The integrative review identified four sub-themes that describe mixed methods design in the context of mental health research. The sub-themes include the categories of mixed methods, their function, structure, process and further methodological considerations for mixed methods design. These sub-themes are explained as follows:

Categorizing mixed methods in mental health research

Four studies highlighted the categories of mixed methods design applicable to mental health research [ 18 , 19 , 43 , 48 ]. Generally, there are differences in the categories of mixed methods design, however, three distinct categories predominantly appear to cross cut in all studies. These categories are function, structure and process. Some studies further categorised mixed method design to include rationale, objectives, or purpose. For instance, Schoonenboom and Johnson [ 48 ] categorised mixed methods design into primary and secondary dimensions.

The function of mixed methods in mental health research

Six studies explain the function of conducting mixed methods design in mental health research. Two studies specifically recommended that mixed methods have the ability to provide a more robust understanding of services by expanding and strengthening the conclusions from the study [ 42 , 45 ]. More importantly, the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods have the ability to provide innovative solutions to important and complex problems, especially by addressing diversity and divergence [ 48 ]. The review identified five underlying functions of a mixed method design in mental health research which include achieving convergence, complementarity, expansion, development and sampling [ 18 , 19 , 43 ].

The use of mixed methods to achieve convergence aims to employ both qualitative and quantitative data to answer the same question, either through triangulation (to confirm the conclusions from each of the methods) or transformation (using qualitative techniques to transform quantitative data). Similarly, complementarity in mixed methods integrates both qualitative and quantitative methods to answer questions for the purpose of evaluation or elaboration [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. Two papers recommend that qualitative methods are used to provide the depth of understanding, whilst the quantitative methods provide a breadth of understanding [ 18 , 43 ]. In mental health research, the qualitative data is often used to examine treatment processes, whilst the quantitative methods are used to examine treatment outcomes against quality care key performance targets.

Additionally, three papers indicated that expansion as a function of mixed methods uses one type of method to answer questions raised by the other type of method [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. For instance, qualitative data is used to explain findings from quantitative analysis. Also, some studies highlight that development as a function of mixed methods aims to use one method to answer research questions, and use the findings to inform other methods to answer different research questions. A qualitative method, for example, is used to identify the content of items to be used in a quantitative study. This approach aims to use qualitative methods to create a conceptual framework for generating hypotheses to be tested by using a quantitative method [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. Three papers suggested that using mixed methods for the purpose of sampling utilize one method (eg. quantitative) to identify a sample of participants to conduct research using other methods (eg. qualitative) [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. For instance, quantitative data is sequentially utilized to identify potential participants to participate in a qualitative study and the vice versa.

Structure of mixed methods in mental health research

Five studies categorised the structure of conducting mixed methods in mental health research, into two broader concepts including simultaneous (concurrent) and sequential (see Table 3 ). In both categories, one method is regarded as primary and the other as secondary, although equal weight can be given to both methods [ 18 , 19 , 42 , 43 , 48 ]. Two studies suggested that the sequential design is a process where the data collection and analysis of one component (eg. quantitative) takes place after the data collection and analysis of the other component (eg qualitative). Herein, the data collection and analysis of one component (e.g. qualitative) may depend on the outcomes of the other component (e.g. quantitative) [ 43 , 48 ]. An earlier review suggested that the majority of contemporary studies in mental health research use a sequential design, with qualitative methods, more often preceding quantitative methods [ 18 ].

Alternatively, the concurrent design collects and analyses data of both components (e.g. quantitative and qualitative) simultaneously and independently. Palinkas, Horwitz [ 42 ] recommend that one component is used as secondary to the other component, or that both components are assigned equal priority. Such a mixed methods approach aims to provide a depth of understanding afforded by qualitative methods, with the breadth of understanding offered by the quantitative data to elaborate on the findings of one component or seek convergence through triangulation of the results. Schoonenboom and Johnson [ 48 ] recommended the use of capital letters for one component and lower case letters for another component in the same design to indicate that one component is primary and the other is secondary or supplemental.

Process of mixed methods in mental health research

Five papers highlighted the process for the use of mixed methods in mental health research [ 18 , 19 , 42 , 43 , 48 ]. The papers suggested three distinct processes or strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative data. These include merging or converging the two data sets, connecting the two datasets by having one build upon the other; and embedding one data set within the other [ 19 , 43 ]. The process of connecting occurs when the analysis of one dataset leads to the need for the other data set. For instance, in the situation where quantitative results lead to the subsequent collection and analysis of qualitative data [ 18 , 43 ]. A previous study suggested that most studies in mental health sought to connect the data sets. Similarly, the process of merging the datasets brings together two sets of data during the interpretation, or transforms one type of data into the other type, by combining the data into new variables [ 18 ]. The process of embedding data into mixed method designs in mental health uses one dataset to provide a supportive role to the other dataset [ 43 ].

Consideration for using mixed methods in mental health research

Three studies highlighted several factors that need to be considered when conducting mixed methods design in mental health research [ 18 , 19 , 45 ]. Accordingly, these factors include developing familiarity with the topic under investigation based on experience, willingness to share information on the topic [ 19 ], establishing early collaboration, willingness to negotiate emerging problems, seeking the contribution of team members, and soliciting third-party assistance to resolve any emerging problems [ 45 ]. Additionally, Palinkas, Horwitz [ 18 ] recommended that mixed methods in the context of mental health research are mostly applied in studies that assess needs of services, examine existing services, developing new or adapting existing services, evaluating services in randomised control trials, and examining service implementation.

Qualitative study in mental health research

This theme describes the various qualitative methods used in mental health research. The theme also addresses methodological considerations for using qualitative methods in mental health research. The key emerging issues are discussed below:

Considering qualitative components in conducting mental health research

Six studies recommended the use of qualitative methods in mental health research [ 19 , 26 , 28 , 32 , 36 , 44 ]. Two qualitative research paradigms were identified, including the interpretive and critical approach [ 32 ]. The interpretive methodologies predominantly explore the meaning of human experiences and actions, whilst the critical approach emphasises the social and historical origins and contexts of meaning [ 32 ]. Two studies suggested that the interpretive qualitative methods used in mental health research are ethnography, phenomenology and narrative approaches [ 32 , 36 ].

The ethnographic approach describes the everyday meaning of the phenomena within a societal and cultural context, for instance, the way phenomena or experience is contrasted within a community, or by collective members over time [ 32 ]. Alternatively, the phenomenological approach explores the claims and concerns of a subject with a speculative development of an interpretative account within their cultural and physical environments focusing on the lived experience [ 32 , 36 ].

Moreover, the critical qualitative approaches used in mental health research are predominantly emancipatory (for instance, socio-political traditions) and participatory action-based research. The emancipatory traditions recognise that knowledge is acquired through critical discourse and debate but are not seen as discovered by objective inquiry [ 32 ]. Alternatively, the participatory action based approach uses critical perspectives to engage key stakeholders as participants in the design and conduct of the research [ 32 ].

Some studies highlighted several reasons why qualitative methods are relevant to mental health research. In particular, qualitative methods are significant as they emphasise naturalistic inquiry and have a discovery-oriented approach [ 19 , 26 ]. Two studies suggested that qualitative methods are often relevant in the initial stages of research studies to understand specific issues such as behaviour, or symptoms of consumers of mental services [ 19 ]. Specifically, Palinkas [ 19 ] suggests that qualitative methods help to obtain initial pilot data, or when there is too little previous research or in the absence of a theory, such as provided in exploratory studies, or previously under-researched phenomena.

Three studies stressed that qualitative methods can help to better understand socially sensitive issues, such as exploring the solutions to overcome challenges in mental health clinical policies [ 19 , 28 , 44 ]. Consequently, Razafsha, Behforuzi [ 44 ] recommended that the natural holistic view of qualitative methods can help to understand the more recovery-oriented policy of mental health, rather than simply the treatment of symptoms. Similarly, the subjective experiences of consumers using qualitative approaches have been found useful to inform clinical policy development [ 28 ].

Sampling in mental health research

The theme explains the sampling approaches used in mental health research. The section also describes the methodological considerations when sampling participants for mental health research. The sub-themes emerging are explained in the following sections:

Sampling approaches (quantitative)

Some studies reviewed highlighted the sampling approaches previously used in mental health research [ 25 , 34 , 35 ]. Generally, all quantitative studies tend to use several probability sampling approaches, whilst qualitative studies used non-probability techniques. The quantitative mental health studies conducted at community and population level employ multi-stage sampling techniques usually involving systematic sampling, stratified and random sampling [ 25 , 34 ]. Similarly, quantitative studies that recruit consumers in the hospital setting employ consecutive sampling [ 35 ]. Two studies reviewed highlighted that the identification of consumers of mental health services for research is usually conducted by service providers. For instance, Korver, Quee [ 35 ] research used a consecutive sampling approach by identifying consumers through clinicians working in regional psychosis departments, or academic centres.

Sampling approaches (qualitative)

Seven studies suggested that the sampling procedures widely used in mental health research involving qualitative methods are non-probability techniques, which include purposive [ 19 , 28 , 32 , 42 , 46 ], snowballing [ 30 , 32 , 46 ] and theoretical sampling [ 31 , 32 ]. The purposive sampling identifies participants that possess relevant characteristics to answer a research question [ 28 ]. Purposive sampling can be used in a single case study, or for multiple cases. The purposive sampling used in mental health research is usually extreme, or deviant case sampling, criterion sampling, and maximum variation sampling [ 19 ]. Furthermore, it is advised when using purposive sampling in a multistage level study, that it should aim to begin with the broader picture to achieve variation, or dispersion, before moving to the more focused view that considers similarity, or central tendencies [ 42 ].

Two studies added that theoretical sampling involved sampling participants, situations and processes based on concepts on theoretical grounds and then using the findings to build theory, such as in a Grounded Theory study [ 31 , 32 ]. Some studies highlighted that snowball sampling is another strategy widely used in mental health research [ 30 , 32 , 46 ]. This is ascribed to the fact that people with mental illness are perceived as marginalised in research and practically hard-to-reach using conventional sampling [ 30 , 32 ]. Snowballing sampling involves asking the marginalised participants to recommend individuals who might have direct knowledge relevant to the study [ 30 , 32 , 46 ]. Although this approach is relevant, some studies advise the limited possibility of generalising the sample, because of the likelihood of selection bias [ 30 ].

Sampling consideration

Four studies in this section highlighted some of the sampling considerations in mental health research [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 46 ]. Generally, mental health research should consider the appropriateness and adequacy of sampling approach by applying attributes such as shared social, or cultural experiences, or shared concern related to the study [ 32 ], diversity and variety of participants [ 31 ], practical and organisational skills, as well as ethical and sensitivity issues [ 46 ]. Robinson [ 46 ] further suggested that sampling can be homogenous or heterogeneous depending on the research questions for the study. Achieving homogeneity in sampling should employ a variety of parameters, which include demographic, graphical, physical, psychological, or life history homogeneity [ 46 ]. Additionally, applying homogeneity in sampling can be influenced by theoretical and practical factors. Alternatively, some samples are intentionally selected based on heterogeneous factors [ 46 ].

Data collection in mental health research

This theme highlights the data collection methods used in mental health research. The theme is explained according to three sub-themes, which include approaches for collecting qualitative data, methodological considerations, as well as preparations for data collection. The sub-themes are as follows:

Approaches for collecting qualitative data

The studies reviewed recommended the approaches that are widely applied in collecting data in mental health research. The widely used qualitative data collection approaches in mental health research are focus group discussions (FGDs) [ 19 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 41 , 44 , 47 ], extended in-depth interviews [ 19 , 30 , 34 ], participant and non-participant observation [ 19 ], Delphi data collection, quasi-statistical techniques [ 19 ] and field notes [ 31 , 40 ]. Seven studies suggest that FGDs are widely used data collection approaches [ 19 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 41 , 44 , 47 ] because they are valuable in gathering information on consumers’ perspectives of services, especially regarding satisfaction, unmet/met service needs and the perceived impact of services [ 47 ]. Conversely, Ekblad and Baarnhielm [ 31 ] recommended that this approach is relevant to improve clinical understanding of the thoughts, emotions, meanings and attitudes towards mental health services.

Such data collection approaches are particularly relevant to consumers of mental health services, due to their low self-confidence and self-esteem [ 41 ]. The approach can help to understand specific terms, vocabulary, opinions and attitudes of consumers of mental health services, as well as their reasoning about personal distress and healing [ 31 ]. Similarly, the reliance on verbal rather than written communication helps to promote the participation of participants with serious and enduring mental health problems [ 31 , 41 ]. Although FGD has several important outcomes, there are some limitations that need critical consideration. Ekblad and Baarnhielm [ 31 ] for example suggest, that marginalised participants may not always feel free to talk about private issues regarding their condition at the group level mostly due to perceived stigma and group confidentiality.

Some studies reviewed recommended that attempting to capture comprehensive information and analysing group interactions in mental health research requires the research method to use field notes as a supplementary data source to help validate the FGDs [ 31 , 40 , 41 ]. The use of field notes in addition to FGDs essentially provides greater detail in the accounts of consumers’ subjective experiences. Furthermore, Montgomery and Bailey [ 40 ] suggest that field notes require observational sensitivity, and also require having specific content such as descriptive and interpretive data.

Three studies in this section suggested that in-depth interviews are used to collect data from consumers of mental health services [ 19 , 30 , 34 ]. This approach is particularly important to explore the behaviour, subjective experiences and psychological processes; opinions, and perceptions of mental health services. de Jong and Van Ommeren [ 30 ] recommend that in-depth interviews help to collect data on culturally marked disorders, their personal and interpersonal significance, patient and family explanatory models, individual and family coping styles, symptom symbols and protective mediators. Palinkas [ 19 ] also highlights that the structured narrative form of extended interviewing is the type of in-depth interview used in mental health research. This approach provides participants with the opportunity to describe the experience of living with an illness and seeking services that assist them.

Consideration for data collection

Six studies recommended consideration required in the data collection process [ 31 , 32 , 37 , 41 , 47 , 49 ]. Some studies highlighted that consumers of mental health services might refuse to participate in research due to several factors [ 37 ] like the severity of their illness, stigma and discrimination [ 41 ]. Subsequently, such issues are recommended to be addressed by building confidence and trust between the researcher and consumers [ 31 , 37 ]. This is a significant prerequisite, as it can sensitise and normalise the research process and aims with the participants prior to discussing their personal mental health issues. Similarly, some studies added that the researcher can gain the confidence of service providers who manage consumers of mental health services [ 41 , 47 ], seek ethical approval from the relevant committee(s) [ 41 , 47 ], meet and greet the consumers of mental health services before data collection, and arrange a mutually acceptable venue for the groups and possibly supply transport [ 41 ].

Two studies further suggested that the cultural and social differences of the participants need consideration [ 26 , 31 ]. These factors could influence the perception and interpretation of ethical issues in the research situation.

Additionally, two studies recommended the use of standardised assessment instruments for mental health research that involve quantitative data collection [ 33 , 49 ]. A recent survey suggested that measures to standardise the data collection approach can convert self-completion instruments to interviewer-completion instruments [ 49 ]. The interviewer can then read the items of the instruments to respondents and record their responses. The study further suggested the need to collect demographic and behavioural information about the participant(s).

Preparing for data collection

Eight studies highlighted the procedures involved in preparing for data collection in mental health research [ 25 , 30 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 39 , 41 , 49 ]. These studies suggest that the preparation process involve organising meetings of researchers, colleagues and representatives of the research population. The meeting of researchers generally involves training of interviewers about the overall design, objectives and research questions associated with the study. de Jong and Van Ommeren [ 30 ] recommended that preparation for the use of quantitative data encompasses translating and adapting instruments with the aim of achieving content, semantic, concept, criterion and technical equivalence.

Quality assurance procedures in mental health research

This section describes the quality assurance procedures used in mental health research. Quality assurance is explained according to three sub-themes: 1) seeking informed consent, 2) the procedure for ensuring quality assurance in a quantitative study and 3) the procedure for ensuring quality control in a qualitative study. The sub-themes are explained in the following content.

Seeking informed consent

The papers analysed for the integrative review suggested that the rights of participants to safeguard their integrity must always be respected, and so each potential subject must be adequately informed of the aims, methods, anticipated benefits and potential hazards of the study and any potential discomforts (see Table 3 ). Seven studies highlight that potential participants of mental health research must be consented to the study prior to data collection [ 25 , 26 , 33 , 35 , 37 , 39 , 47 ]. The consent process helps to assure participants of anonymity and confidentiality and further explain the research procedure to them. Baarnhielm and Ekblad [ 26 ] argue that the research should be guided by four basic moral values for medical ethics, autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice. In particular, potential consumers of mental health services who may have severe conditions and unable to consent themselves are expected to have their consent signed by a respective family caregiver [ 37 ]. Latvala, Vuokila-Oikkonen [ 37 ] further suggested that researchers are responsible to agree on the criteria to determine the competency of potential participants in mental health research. The criteria are particularly relevant when potential participants have difficulties in understanding information due to their mental illness.

Procedure for ensuring quality control (quantitative)

Several studies highlighted procedures for ensuring quality control in mental health research (see Table 3 ). The quality control measures are used to achieve the highest reliability, validity and timeliness. Some studies demonstrate that ensuring quality control should consider factors such as pre-testing tools [ 25 , 49 ], minimising non-response rates [ 25 , 39 ] and monitoring of data collection processes [ 25 , 33 , 49 ].

Accordingly, two studies suggested that efforts should be made to re-approach participants who initially refuse to participate in the study. For instance, Liu, Huang [ 39 ] recommended that when a consumer of mental health services refuse to participate in a study (due to low self-esteem) when approached for the first time, a different interviewer can re-approach the same participant to see if they are more comfortable to participate after the first invitation. Three studies further recommend that monitoring data quality can be accomplished through “checks across individuals, completion status and checks across variables” [ 25 , 33 , 49 ]. For example, Alonso, Angermeyer [ 25 ] advocate that various checks are used to verify completion of the interview, and consistency across instruments against the standard procedure.

Procedure for ensuring quality control (qualitative)

Four studies highlighted the procedures for ensuring quality control of qualitative data in mental health research [ 19 , 32 , 37 , 46 ]. A further two studies suggested that the quality of qualitative research is governed by the principles of credibility, dependability, transferability, reflexivity, confirmability [ 19 , 32 ]. Some studies explain that the credibility or trustworthiness of qualitative research in mental health is determined by methodological and interpretive rigour of the phenomenon being investigated [ 32 , 37 ]. Consequently, Fossey, Harvey [ 32 ] propose that the methodological rigour for assessing the credibility of qualitative research are congruence, responsiveness or sensitivity to social context, appropriateness (importance and impact), adequacy and transparency. Similarly, interpretive rigour is classified as authenticity, coherence, reciprocity, typicality and permeability of the researcher’s intentions; including engagement and interpretation [ 32 ].

Robinson [ 46 ] explained that transparency (openness and honesty) is achieved if the research report explicitly addresses how the sampling, data collection, analysis, and presentation are met. In particular, efforts to address these methodological issues highlight the extent to which the criteria for quality profoundly interacts with standards for ethics. Similarly, responsiveness, or sensitivity, helps to situate or locate the study within a place, a time and a meaningful group [ 46 ]. The study should also consider the researcher’s background, location and connection to the study setting, particularly in the recruitment process. This is often described as role conflict or research bias.

In the interpretive phenomenon, coherence highlights the ability to select an appropriate sampling procedure that mutually matches the research aims, questions, data collection, analysis, as well as any theoretical concepts or frameworks [ 32 , 46 ]. Similarly, authenticity explains the appropriate representation of participants’ perspectives in the research process and the interpretation of results. Authenticity is maximised by providing evidence that participants are adequately represented in the interpretive process, or provided an opportunity to give feedback on the researcher’s interpretation [ 32 ]. Again, the contribution of the researcher’s perspective to the interpretation enhances permeability. Fossey, Harvey [ 32 ] further suggest that reflexive reporting, which distinguishes the participants’ voices from that of the researcher in the report, enhances the permeability of the researcher’s role and perspective.

One study highlighted the approaches used to ensure validity in qualitative research, which includes saturation, identification of deviant or non-confirmatory cases, member checking and coding by consensus. Saturation involves completeness in the research process, where all relevant data collection, codes and themes required to answer the phenomenon of inquiry are achieved; and no new data emerges [ 19 ]. Similarly, member checking is the process whereby participants or others who share similar characteristics review study findings to elaborate on confirming them [ 19 ]. The coding by consensus involves a collaborative approach to analysing the data. Ensuring regular meetings among coders to discuss procedures for assigning codes to segments of data and resolve differences in coding procedures, and by comparison of codes assigned on selected transcripts to calculate a percentage agreement or kappa measure of interrater reliability, are commonly applied [ 19 ].

Two studies recommend the need to acknowledge the importance of generalisability (transferability). This concept aims to provide sufficient information about the research setting, findings and interpretations for readers to appropriately determine the replicability of the findings from one context, or population to another, otherwise known as reliability in quantitative research [ 19 , 32 ]. Similarly, the researchers should employ reflexivity as a means of identifying and addressing potential biases in data collection and interpretation. Palinkas [ 19 ] suggests that such bias is associated with theoretical orientations; pre-conceived beliefs, assumptions, and demographic characteristics; and familiarity and experience with the methods and phenomenon. Another approach to enhance the rigour of analysis involves peer debriefing and support meetings held among team members which facilitate detailed auditing during data analysis [ 19 ].

The integrative review was conducted to synthesise evidence into recommended methodological considerations when conducting mental health research. The evidence from the review has been discussed according to five major themes: 1) mixed methods study in mental health research; 2) qualitative study in mental health research; 3) sampling in mental health research; 4) data collection in mental health research; and 5) quality assurance procedures in mental health research.

Mixed methods study in mental health research

The evidence suggests that mixed methods approach in mental health are generally categorised according to their function (rationale, objectives or purpose), structure and process [ 18 , 19 , 43 , 48 ]. The mixed methods study can be conducted for the purpose of achieving convergence, complementarity, expansion, development and sampling [ 18 , 19 , 43 ]. Researchers conducting mental health studies should understand the underlying functions or purpose of mixed methods. Similarly, mixed methods in mental health studies can be structured simultaneously (concurrent) and sequential [ 18 , 19 , 42 , 43 , 48 ]. More importantly, the process of combining qualitative and quantitative data can be achieved through merging or converging, connecting and embedding one data set within the other [ 18 , 19 , 42 , 43 , 48 ]. The evidence further recommends that researchers need to understand the stage of integrating the two sets of data and the rationale for doing so. This can inform researchers regarding the best stage and appropriate ways of combining the two components of data to adequately address the research question(s).

The evidence recommended some methodological consideration in the design of mixed methods projects in mental health [ 18 , 19 , 45 ]. These issues include establishing early collaboration, becoming familiar with the topic, sharing information on the topic, negotiating any emerging problems and seeking contributions from team members. The involvement of various expertise could ensure that methodological issues are clearly identified. However, addressing such issues midway, or late through the design can negatively affect the implementation [ 45 ]. Any robust discoveries can rarely be accommodated under the existing design. Therefore, the inclusion of various methodological expertise during inception can lead to a more robust mixed-methods design which maximises the contributions of team members. Whilst fundamental and philosophical differences in qualitative and quantitative methods may not be resolved, some workable solutions can be employed, particularly if challenges are viewed as philosophical rather than personal [ 45 ]. The cultural issues can be alleviated by understanding the concepts, norms and values of the setting, further to respecting and including perspectives of the various stakeholders.