- Biology Article

- Biogeochemical Cycles

Process of Biogeochemical Cycles

What is a biogeochemical cycle.

“Biogeochemical cycles mainly refer to the movement of nutrients and other elements between biotic and abiotic factors.”

The term biogeochemical is derived from “bio” meaning biosphere , “geo” meaning the geological components and “ chemical ” meaning the elements that move through a cycle .

The matter on Earth is conserved and present in the form of atoms. Since matter can neither be created nor destroyed, it is recycled in the earth’s system in various forms.

The earth obtains energy from the sun which is radiated back as heat, rest all other elements are present in a closed system. The major elements include:

These elements are recycled through the biotic and abiotic components of the ecosystem . The atmosphere, hydrosphere and lithosphere are the abiotic components of the ecosystem.

Types of Biogeochemical Cycles

Biogeochemical cycles are basically divided into two types:

- Gaseous cycles – Includes Carbon, Oxygen, Nitrogen, and the Water cycle.

- Sedimentary cycles – Includes Sulphur, Phosphorus, Rock cycle, etc.

Let us have a look at each of these biogeochemical cycles in brief:

Water Cycle

The water from the different water bodies evaporates, cools, condenses and falls back to the earth as rain.

This biogeochemical cycle is responsible for maintaining weather conditions. The water in its various forms interacts with the surroundings and changes the temperature and pressure of the atmosphere.

There’s another process called Evapotranspiration (i.e. vapour produced from leaves) which aids this process. It is the evaporation of water from the leaves, soil and water bodies to the atmosphere which again condenses and falls as rain.

Also Read: Water Cycle

Carbon Cycle

It is one of the biogeochemical cycles in which carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere and pedosphere.

All green plants use carbon dioxide and sunlight for photosynthesis . Carbon is thus stored in the plant. The green plants, when dead, are buried into the soil that gets converted into fossil fuels made from carbon. These fossil fuels when burnt, release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Also, the animals that consume plants, obtain the carbon stored in the plants. This carbon is returned to the atmosphere when these animals decompose after death. The carbon also returns to the environment through cellular respiration by animals.

Huge carbon content in the form of carbon dioxide is produced that is stored in the form of fossil fuel (coal & oil) and can be extracted for various commercial and non-commercial purposes. When factories use these fuels, the carbon is again released back in the atmosphere during combustion.

Also Read: Carbon cycle

Nitrogen Cycle

It is the biogeochemical cycle by which nitrogen is converted into several forms and it gets circulated through the atmosphere and various ecosystems such as terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Nitrogen is an essential element of life. The nitrogen in the atmosphere is fixed by the nitrogen-fixing bacteria present in the root nodules of the leguminous plants and made available to the soil and plants.

The bacteria present in the roots of the plants convert this nitrogen gas into a usable compound called ammonia. Ammonia is also supplied to plants in the form of fertilizers. This ammonia is converted into nitrites and nitrates. The denitrifying bacteria reduce the nitrates into nitrogen and return it into the atmosphere.

Also Read: Nitrogen Cycle

Oxygen Cycle

This biogeochemical cycle moves through the atmosphere, the lithosphere and the biosphere. Oxygen is an abundant element on our Earth. It is found in the elemental form in the atmosphere to the extent of 21%.

Oxygen is released by the plants during photosynthesis. Humans and other animals inhale the oxygen exhale carbon dioxide which is again taken up by the plants. They utilise this carbon dioxide in photosynthesis to produce oxygen, and the cycle continues.

Also Read: Oxygen Cycle

Phosphorous Cycle

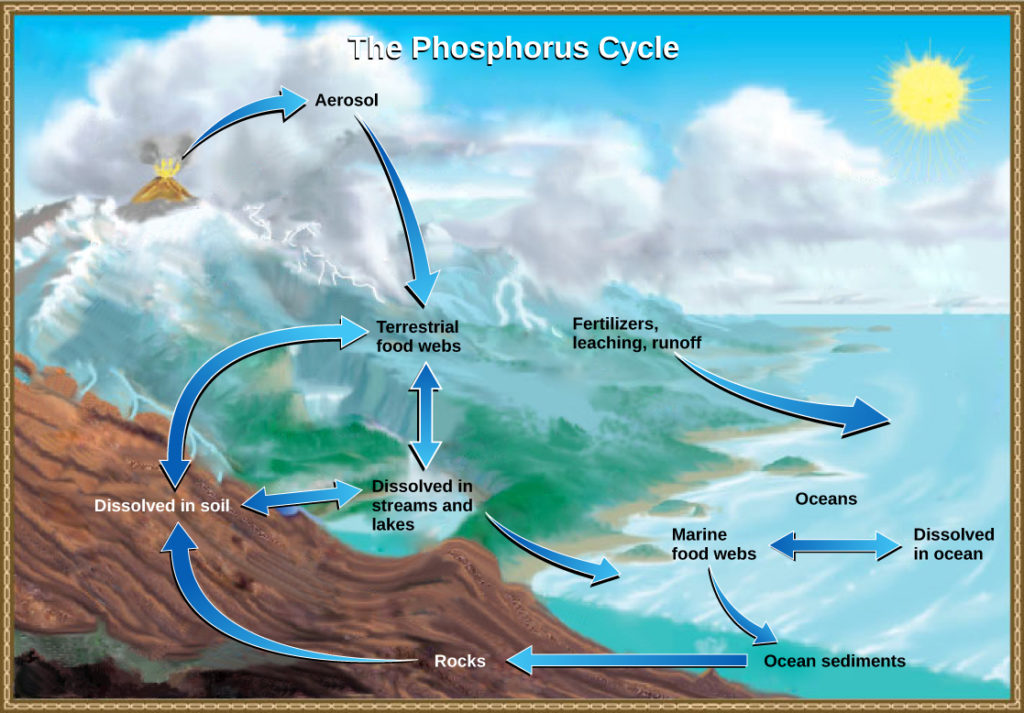

In this biogeochemical cycle, phosphorus moves through the hydrosphere, lithosphere and biosphere. Phosphorus is extracted by the weathering of rocks. Due to rains and erosion phosphorus is washed away in the soil and water bodies. Plants and animals obtain this phosphorus through the soil and water and grow. Microorganisms also require phosphorus for their growth. When the plants and animals die they decompose, and the stored phosphorus is returned to the soil and water bodies which is again consumed by plants and animals and the cycle continues.

Also Read: Phosphorus cycle

Sulphur Cycle

This biogeochemical cycle moves through the rocks, water bodies and living systems. Sulphur is released into the atmosphere by the weathering of rocks and is converted into sulphates. These sulphates are taken up by the microorganisms and plants and converted into organic forms. Organic sulphur is consumed by animals through food. When the animals die and decompose, sulphur is returned to the soil, which is again obtained by the plants and microbes, and the cycle continues.

Also Read: Sulphur cycle

Importance of Biogeochemical Cycles

These cycles demonstrate the way in which the energy is used. Through the ecosystem, these cycles move the essential elements for life to sustain. They are vital as they recycle elements and store them too, and regulate the vital elements through the physical facets. These cycles depict the association between living and non-living things in the ecosystems and enable the continuous survival of ecosystems.

It is important to comprehend these cycles to learn their effect on living entities. Some activities of humans disturb a few of these natural cycles and thereby affecting related ecosystems. A closer look at these mechanisms can help us restrict and stop their dangerous impact.

To learn more about biogeochemical cycles, and their types, keep visiting BYJU’S website or download BYJU’S app for further reference.

Put your understanding of this concept to test by answering a few MCQs. Click ‘Start Quiz’ to begin!

Select the correct answer and click on the “Finish” button Check your score and answers at the end of the quiz

Visit BYJU’S for all Biology related queries and study materials

Your result is as below

Request OTP on Voice Call

| BIOLOGY Related Links | |

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post My Comment

Excellent work of byju’s app 👌

can i have digram of all cycles

You are the best 👌🥰😇

Thanks Byjus for your Answer. It helped me a lot.

I need some MCQ question on environmental awareness

You can find these here: https://byjus.com/biology/environmental-issues-mcq/

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

37.3 Biogeochemical Cycles

Learning objectives.

In this section, you will explore the following questions:

- What are the basic stages in the biogeochemical cycles of water, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur?

- How have human activities impacted these biogeochemical cycles, and what are the potential consequences for Earth?

Connection for AP ® Courses

As we learned in Energy Flow through Ecosystems , energy takes a one-way path (flows directionally) through the trophic levels in an ecosystem. However, the matter that comprises living organisms is conserved and recycled through what are referred to as biogeochemical cycles . The six most common elements associated with organic molecules—carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur—take a variety of chemical forms and may exist for long periods in Earth’s atmosphere, on land, in water, or beneath our planet’s surface. Geologic processes, including weathering and erosion, play a role in this recycling of materials from the environment to living organisms. For the purpose of AP ® , you do not need to know the details of every biogeochemical cycle, though some details of those cycles are covered in this section.

Information presented and the examples highlighted in the section support concepts outlined in Big Idea 2 and Big Idea 4 of the AP ® Biology Curriculum Framework. The AP ® Learning Objectives listed in the Curriculum Framework provide a transparent foundation for the AP ® Biology course, an inquiry-based laboratory experience, instructional activities, and AP ® exam questions. A learning objective merges required content with one or more of the seven science practices.

| Biological systems utilize free energy and molecular building blocks to grow, to reproduce, and to maintain dynamic homeostasis. | |

| Growth, reproduction and maintenance of living systems require free energy and matter. | |

| Organisms must exchange matter with the environment to grow, reproduce and maintain organization. | |

| The student can create representations and models of natural or man-made phenomena and systems in the domain. | |

| The student can use representations and models to analyze situations or solve problems qualitatively and quantitatively. | |

| The student is able to represent graphically or model quantitatively the exchange of molecules between an organism and its environment, and the subsequent use of these molecules to build new molecules that facilitate dynamic homeostasis, growth and reproduction. | |

| Biological systems interact, and these systems and their interactions possess complex properties. | |

| Interactions within biological systems lead to complex properties. | |

| Interactions among living systems and with their environment result in the movement of matter and energy. | |

| The student can use representations and models to analyze situations or solve problems qualitatively and quantitatively. | |

| The student is able to use visual representations to analyze situations or solve problems qualitatively to illustrate how interactions among living systems and with their environment results in the movement of matter and energy. |

Water contains hydrogen and oxygen, which is essential to all living processes. The hydrosphere is the area of the Earth where water movement and storage occurs: as liquid water on the surface and beneath the surface or frozen (rivers, lakes, oceans, groundwater, polar ice caps, and glaciers), and as water vapor in the atmosphere. Carbon is found in all organic macromolecules and is an important constituent of fossil fuels. Nitrogen is a major component of our nucleic acids and proteins and is critical to human agriculture. Phosphorus, a major component of nucleic acid (along with nitrogen), is one of the main ingredients in artificial fertilizers used in agriculture and their associated environmental impacts on our surface water. Sulfur, critical to the 3–D folding of proteins (as in disulfide binding), is released into the atmosphere by the burning of fossil fuels, such as coal.

The cycling of these elements is interconnected. For example, the movement of water is critical for the leaching of nitrogen and phosphate into rivers, lakes, and oceans. Furthermore, the ocean itself is a major reservoir for carbon. Thus, mineral nutrients are cycled, either rapidly or slowly, through the entire biosphere, from one living organism to another, and between the biotic and abiotic world.

Link to Learning

Head to this website to learn more about biogeochemical cycles.

- There is a variable amount of each element on Earth.

- A reservoir is where elements remain through time.

- Only external energy sources drive movement of elements.

- Geochemical cycles are characterized by the movement of elements.

The Water (Hydrologic) Cycle

Water is the basis of all living processes. The human body is more than 1/2 water and human cells are more than 70 percent water. Thus, most land animals need a supply of fresh water to survive. However, when examining the stores of water on Earth, 97.5 percent of it is non-potable salt water ( Figure 37.13 ). Of the remaining water, 99 percent is locked underground as water or as ice. Thus, less than 1 percent of fresh water is easily accessible from lakes and rivers. Many living things, such as plants, animals, and fungi, are dependent on the small amount of fresh surface water supply, a lack of which can have massive effects on ecosystem dynamics. Humans, of course, have developed technologies to increase water availability, such as digging wells to harvest groundwater, storing rainwater, and using desalination to obtain drinkable water from the ocean. Although this pursuit of drinkable water has been ongoing throughout human history, the supply of fresh water is still a major issue in modern times.

Water cycling is extremely important to ecosystem dynamics. Water has a major influence on climate and, thus, on the environments of ecosystems, some located on distant parts of the Earth. Most of the water on Earth is stored for long periods in the oceans, underground, and as ice. Figure 37.14 illustrates the average time that an individual water molecule may spend in the Earth’s major water reservoirs. Residence time is a measure of the average time an individual water molecule stays in a particular reservoir. A large amount of the Earth’s water is locked in place in these reservoirs as ice, beneath the ground, and in the ocean, and, thus, is unavailable for short-term cycling (only surface water can evaporate).

There are various processes that occur during the cycling of water, shown in Figure 37.15 . These processes include the following:

- evaporation/sublimation

- condensation/precipitation

- subsurface water flow

- surface runoff/snowmelt

The water cycle is driven by the sun’s energy as it warms the oceans and other surface waters. This leads to the evaporation (water to water vapor) of liquid surface water and the sublimation (ice to water vapor) of frozen water, which deposits large amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere. Over time, this water vapor condenses into clouds as liquid or frozen droplets and is eventually followed by precipitation (rain or snow), which returns water to the Earth’s surface. Rain eventually permeates into the ground, where it may evaporate again if it is near the surface, flow beneath the surface, or be stored for long periods. More easily observed is surface runoff: the flow of fresh water either from rain or melting ice. Runoff can then make its way through streams and lakes to the oceans or flow directly to the oceans themselves.

Head to this website to learn more about the world’s fresh water supply.

- Humans utilize water from oceans, which is the most common ecosystem.

- Humans utilize freshwater, which is the rarest ecosystem.

- Humans utilize freshwater, which is the most common ecosystem.

- Humans utilize water from oceans, which is the rarest ecosystem.

Rain and surface runoff are major ways in which minerals, including carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur, are cycled from land to water. The environmental effects of runoff will be discussed later as these cycles are described.

The Carbon Cycle

Carbon is the second most abundant element in living organisms. Carbon is present in all organic molecules, and its role in the structure of macromolecules is of primary importance to living organisms. Carbon compounds contain especially high energy, particularly those derived from fossilized organisms, mainly plants, which humans use as fuel. Since the 1800s, the number of countries using massive amounts of fossil fuels has increased. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, global demand for the Earth’s limited fossil fuel supplies has risen; therefore, the amount of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere has increased. This increase in carbon dioxide has been associated with climate change and other disturbances of the Earth’s ecosystems and is a major environmental concern worldwide. Thus, the “carbon footprint” is based on how much carbon dioxide is produced and how much fossil fuel countries consume.

The carbon cycle is most easily studied as two interconnected sub-cycles: one dealing with rapid carbon exchange among living organisms and the other dealing with the long-term cycling of carbon through geologic processes. The entire carbon cycle is shown in Figure 37.16 .

Click this link to read information about the United States Carbon Cycle Science Program.

- Carbon sources, such as burning fossil fuels, produce carbon while carbon sinks, such as oceans, absorb carbon.

- Carbon sources, such as volcanic activity, absorb carbon while carbon sinks, such as vegetation, produce carbon.

- Carbon sources, such as vegetation, produce carbon while carbon sinks, such as volcanic activity, absorb carbon.

- Carbon sources, such as volcanic activity, produce carbon while carbon sinks, such as burning fossil fuels, absorb carbon.

The Biological Carbon Cycle

Living organisms are connected in many ways, even between ecosystems. A good example of this connection is the exchange of carbon between autotrophs and heterotrophs within and between ecosystems by way of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is the basic building block that most autotrophs use to build multi-carbon, high energy compounds, such as glucose. The energy harnessed from the sun is used by these organisms to form the covalent bonds that link carbon atoms together. These chemical bonds thereby store this energy for later use in the process of respiration. Most terrestrial autotrophs obtain their carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere, while marine autotrophs acquire it in the dissolved form (carbonic acid, H 2 CO 3 − ). However carbon dioxide is acquired, a by-product of the process is oxygen. The photosynthetic organisms are responsible for creating the oxygen content of our atmosphere; oxygen makes up approximately 21 percent of the atmosphere that we observe today.

Heterotrophs and autotrophs are partners in biological carbon exchange (especially the primary consumers, largely herbivores). Heterotrophs acquire the high-energy carbon compounds from the autotrophs by consuming them, and breaking them down by respiration to obtain cellular energy, such as ATP. The most efficient type of respiration, aerobic respiration, requires oxygen obtained from the atmosphere or dissolved in water. Thus, there is a constant exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the autotrophs (which need the carbon) and the heterotrophs (which need the oxygen). Gas exchange through the atmosphere and water is one way that the carbon cycle connects all living organisms on Earth.

The Biogeochemical Carbon Cycle

The movement of carbon through the land, water, and air is complex, and in many cases, it occurs much more slowly geologically than as seen between living organisms. Carbon is stored for long periods in what are known as carbon reservoirs, which include the atmosphere, bodies of liquid water (mostly oceans), ocean sediment, soil, land sediments (including fossil fuels), and the Earth’s interior.

As stated, the atmosphere is a major reservoir of carbon in the form of carbon dioxide and is essential to the process of photosynthesis. The level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is greatly influenced by the reservoir of carbon in the oceans. The exchange of carbon between the atmosphere and water reservoirs influences how much carbon is found in each location, and each one affects the other reciprocally. Carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) from the atmosphere dissolves in water and combines with water molecules to form carbonic acid, and then it ionizes to carbonate and bicarbonate ions ( Figure 37.17 )

The equilibrium coefficients are such that more than 90 percent of the carbon in the ocean is found as bicarbonate ions. Some of these ions combine with seawater calcium to form calcium carbonate (CaCO 3 ), a major component of marine organism shells. These organisms eventually form sediments on the ocean floor. Over geologic time, the calcium carbonate forms limestone, which comprises the largest carbon reservoir on Earth.

On land, carbon is stored in soil as a result of the decomposition of living organisms (by decomposers) or from weathering of terrestrial rock and minerals. This carbon can be leached into the water reservoirs by surface runoff. Deeper underground, on land and at sea, are fossil fuels: the anaerobically decomposed remains of plants that take millions of years to form. Fossil fuels are considered a non-renewable resource because their use far exceeds their rate of formation. A non-renewable resource , such as fossil fuel, is either regenerated very slowly or not at all. Another way for carbon to enter the atmosphere is from land (including land beneath the surface of the ocean) by the eruption of volcanoes and other geothermal systems. Carbon sediments from the ocean floor are taken deep within the Earth by the process of subduction : the movement of one tectonic plate beneath another. Carbon is released as carbon dioxide when a volcano erupts or from volcanic hydrothermal vents.

Carbon dioxide is also added to the atmosphere by the animal husbandry practices of humans. The large numbers of land animals raised to feed the Earth’s growing population results in increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere due to farming practices and the respiration and methane production. This is another example of how human activity indirectly affects biogeochemical cycles in a significant way. Although much of the debate about the future effects of increasing atmospheric carbon on climate change focuses on fossils fuels, scientists take natural processes, such as volcanoes and respiration, into account as they model and predict the future impact of this increase.

The Nitrogen Cycle

Getting nitrogen into the living world is difficult. Plants and phytoplankton are not equipped to incorporate nitrogen from the atmosphere (which exists as tightly bonded, triple covalent N 2 ) even though this molecule comprises approximately 78 percent of the atmosphere. Nitrogen enters the living world via free-living and symbiotic bacteria, which incorporate nitrogen into their macromolecules through nitrogen fixation (conversion of N 2 ). Cyanobacteria live in most aquatic ecosystems where sunlight is present; they play a key role in nitrogen fixation. Cyanobacteria are able to use inorganic sources of nitrogen to “fix” nitrogen. Rhizobium bacteria live symbiotically in the root nodules of legumes (such as peas, beans, and peanuts) and provide them with the organic nitrogen they need. Free-living bacteria, such as Azotobacter , are also important nitrogen fixers.

Organic nitrogen is especially important to the study of ecosystem dynamics since many ecosystem processes, such as primary production and decomposition, are limited by the available supply of nitrogen. As shown in Figure 37.18 , the nitrogen that enters living systems by nitrogen fixation is successively converted from organic nitrogen back into nitrogen gas by bacteria. This process occurs in three steps in terrestrial systems: ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification. First, the ammonification process converts nitrogenous waste from living animals or from the remains of dead animals into ammonium (NH 4 + ) by certain bacteria and fungi. Second, the ammonium is converted to nitrites (NO 2 − ) by nitrifying bacteria, such as Nitrosomonas , through nitrification. Subsequently, nitrites are converted to nitrates (NO 3 − ) by similar organisms. Third, the process of denitrification occurs, whereby bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Clostridium , convert the nitrates into nitrogen gas, allowing it to re-enter the atmosphere.

Visual Connection

- Ammonification converts organic nitrogenous matter from living organisms into ammonium (NH4 + ).

- Denitrification by bacteria converts nitrates (NO3 - ) to nitrogen gas (N2).

- Nitrification by bacteria converts nitrates (NO3 - ) to nitrites (NO2 - ).

- Nitrogen fixing bacteria convert nitrogen gas (N2) into organic compounds.

Human activity can release nitrogen into the environment by two primary means: the combustion of fossil fuels, which releases different nitrogen oxides, and by the use of artificial fertilizers in agriculture, which are then washed into lakes, streams, and rivers by surface runoff. Atmospheric nitrogen is associated with several effects on Earth’s ecosystems including the production of acid rain (as nitric acid, HNO 3 ) and greenhouse gas (as nitrous oxide, N 2 O) potentially causing climate change. A major effect from fertilizer runoff is saltwater and freshwater eutrophication , a process whereby nutrient runoff causes the excess growth of microorganisms, depleting dissolved oxygen levels and killing ecosystem fauna.

A similar process occurs in the marine nitrogen cycle, where the ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification processes are performed by marine bacteria. Some of this nitrogen falls to the ocean floor as sediment, which can then be moved to land in geologic time by uplift of the Earth’s surface and thereby incorporated into terrestrial rock. Although the movement of nitrogen from rock directly into living systems has been traditionally seen as insignificant compared with nitrogen fixed from the atmosphere, a recent study showed that this process may indeed be significant and should be included in any study of the global nitrogen cycle. 3

Science Practice Connection for AP® Courses

Think about it.

What is the process of nitrogen fixation and how does it relate to crop rotation in agriculture?

Teacher Support

Think About It: Nitrogen fixation is the incorporation of inorganic nitrogen into biological molecules. Certain crops fix nitrogen more readily, leaving nitrogen in the soil for the next drop planted there. The question is an application of AP ® Learning Objective 2.8 and Science Practice 4.1 because students are describing how a type of molecule/element is taken up by bacteria to be used to synthesize macromolecules necessary for cellular processes in other organisms.

The Phosphorus Cycle

Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for living processes; it is a major component of nucleic acid and phospholipids, and, as calcium phosphate, makes up the supportive components of our bones. Phosphorus is often the limiting nutrient (necessary for growth) in aquatic ecosystems ( Figure 37.19 ).

Phosphorus occurs in nature as the phosphate ion (PO 4 3− ). In addition to phosphate runoff as a result of human activity, natural surface runoff occurs when it is leached from phosphate-containing rock by weathering, thus sending phosphates into rivers, lakes, and the ocean. This rock has its origins in the ocean. Phosphate-containing ocean sediments form primarily from the bodies of ocean organisms and from their excretions. However, in remote regions, volcanic ash, aerosols, and mineral dust may also be significant phosphate sources. This sediment then is moved to land over geologic time by the uplifting of areas of the Earth’s surface.

Phosphorus is also reciprocally exchanged between phosphate dissolved in the ocean and marine ecosystems. The movement of phosphate from the ocean to the land and through the soil is extremely slow, with the average phosphate ion having an oceanic residence time between 20,000 and 100,000 years.

Excess phosphorus and nitrogen that enters these ecosystems from fertilizer runoff and from sewage causes excessive growth of microorganisms and depletes the dissolved oxygen, which leads to the death of many ecosystem fauna, such as shellfish and finfish. This process is responsible for dead zones in lakes and at the mouths of many major rivers ( Figure 37.19 ).

A dead zone is an area within a freshwater or marine ecosystem where large areas are depleted of their normal flora and fauna; these zones can be caused by eutrophication, oil spills, dumping of toxic chemicals, and other human activities. The number of dead zones has been increasing for several years, and more than 400 of these zones were present as of 2008. One of the worst dead zones is off the coast of the United States in the Gulf of Mexico, where fertilizer runoff from the Mississippi River basin has created a dead zone of over 8463 square miles. Phosphate and nitrate runoff from fertilizers also negatively affect several lake and bay ecosystems including the Chesapeake Bay in the eastern United States.

Everyday Connection

Chesapeake bay.

The Chesapeake Bay has long been valued as one of the most scenic areas on Earth; it is now in distress and is recognized as a declining ecosystem. In the 1970s, the Chesapeake Bay was one of the first ecosystems to have identified dead zones, which continue to kill many fish and bottom-dwelling species, such as clams, oysters, and worms. Several species have declined in the Chesapeake Bay due to surface water runoff containing excess nutrients from artificial fertilizer used on land. The source of the fertilizers (with high nitrogen and phosphate content) is not limited to agricultural practices. There are many nearby urban areas and more than 150 rivers and streams empty into the bay that are carrying fertilizer runoff from lawns and gardens. Thus, the decline of the Chesapeake Bay is a complex issue and requires the cooperation of industry, agriculture, and everyday homeowners.

Of particular interest to conservationists is the oyster population; it is estimated that more than 200,000 acres of oyster reefs existed in the bay in the 1700s, but that number has now declined to only 36,000 acres. Oyster harvesting was once a major industry for Chesapeake Bay, but it declined 88 percent between 1982 and 2007. This decline was due not only to fertilizer runoff and dead zones but also to overharvesting. Oysters require a certain minimum population density because they must be in close proximity to reproduce. Human activity has altered the oyster population and locations, greatly disrupting the ecosystem.

The restoration of the oyster population in the Chesapeake Bay has been ongoing for several years with mixed success. Not only do many people find oysters good to eat, but they also clean up the bay. Oysters are filter feeders, and as they eat, they clean the water around them. In the 1700s, it was estimated that it took only a few days for the oyster population to filter the entire volume of the bay. Today, with changed water conditions, it is estimated that the present population would take nearly a year to do the same job.

Restoration efforts have been ongoing for several years by non-profit organizations, such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The restoration goal is to find a way to increase population density so the oysters can reproduce more efficiently. Many disease-resistant varieties (developed at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science for the College of William and Mary) are now available and have been used in the construction of experimental oyster reefs. Efforts to clean and restore the bay by Virginia and Delaware have been hampered because much of the pollution entering the bay comes from other states, which stresses the need for inter-state cooperation to gain successful restoration.

The new, hearty oyster strains have also spawned a new and economically viable industry—oyster aquaculture—which not only supplies oysters for food and profit, but also has the added benefit of cleaning the bay.

- Excess nitrogen from fertilizer decreases microbial growth, depleting dissolved oxygen in water, thereby killing the fauna of the ecosystem.

- Fertilizer runoff decreases the carbon dioxide concentration in water, thereby killing fauna of the ecosystem.

- Fertilizer runoff produces a dead zone in the Chesapeake Bay by increasing oxygen concentration in the ecosystem.

- Excess nitrogen from fertilizer increases microbial growth, depleting dissolved oxygen in water, thereby killing the fauna of the ecosystem.

The Sulfur Cycle

Sulfur is an essential element for the macromolecules of living things. As a part of the amino acid cysteine, it is involved in the formation of disulfide bonds within proteins, which help to determine their 3-D folding patterns, and hence their functions. As shown in Figure 37.21 , sulfur cycles between the oceans, land, and atmosphere. Atmospheric sulfur is found in the form of sulfur dioxide (SO 2 ) and enters the atmosphere in three ways: from the decomposition of organic molecules, from volcanic activity and geothermal vents, and from the burning of fossil fuels by humans.

On land, sulfur is deposited in four major ways: precipitation, direct fallout from the atmosphere, rock weathering, and geothermal vents ( Figure 37.22 ). Atmospheric sulfur is found in the form of sulfur dioxide (SO 2 ), and as rain falls through the atmosphere, sulfur is dissolved in the form of weak sulfurous acid (H 2 SO 3 ). Sulfur can also fall directly from the atmosphere in a process called fallout . Also, the weathering of sulfur-containing rocks releases sulfur into the soil. These rocks originate from ocean sediments that are moved to land by the geologic uplifting of ocean sediments. Terrestrial ecosystems can then make use of these soil sulfates ( SO 4 − SO 4 − ), and upon the death and decomposition of these organisms, release the sulfur back into the atmosphere as hydrogen sulfide (H 2 S) gas.

Sulfur enters the ocean via runoff from land, from atmospheric fallout, and from underwater geothermal vents. Some ecosystems ( Figure 37.9 ) rely on chemoautotrophs using sulfur as a biological energy source. This sulfur then supports marine ecosystems in the form of sulfates.

Human activities have played a major role in altering the balance of the global sulfur cycle. The burning of large quantities of fossil fuels, especially from coal, releases larger amounts of hydrogen sulfide gas into the atmosphere. As rain falls through this gas, it creates the phenomenon known as acid rain. Acid rain is corrosive rain caused by rainwater falling to the ground through sulfur dioxide gas, turning it into weak sulfuric acid, which causes damage to aquatic ecosystems. Acid rain damages the natural environment by lowering the pH of lakes, which kills many of the resident fauna; it also affects the man-made environment through the chemical degradation of buildings. For example, many marble monuments, such as the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, have suffered significant damage from acid rain over the years. These examples show the wide-ranging effects of human activities on our environment and the challenges that remain for our future.

Click this link to learn more about global climate change.

The image shows the nitrogen resevoirs on Earth.

Make a claim based on this image.

- Most of the nitrogen on Earth is in the atmosphere.

- Most of the nitrogen on Earth is in the oceans.

- In the oceans, nitrogen is in the form of N2 gas.

- Marine organisms contain more nitrogen than land organisms.

- 3 Scott L. Morford, Benjamin Z. Houlton, and Randy A. Dahlgren, “Increased Forest Ecosystem Carbon and Nitrogen Storage from Nitrogen Rich Bedrock,” Nature 477, no. 7362 (2011): 78–81.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Julianne Zedalis, John Eggebrecht

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Biology for AP® Courses

- Publication date: Mar 8, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/37-3-biogeochemical-cycles

© Jul 10, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Browse Course Material

Course info, instructors.

- Prof. Edward DeLong

- Prof. Penny Chisholm

Departments

- Civil and Environmental Engineering

As Taught In

- Earth Science

Learning Resource Types

Ecology i: the earth system, lecture 7 notes — biogeochemical cycles.

Lecture notes on biogeochemical cycles.

You are leaving MIT OpenCourseWare

Module 26: Ecology and the Environment

Biogeochemical cycles, discuss the biogeochemical cycles of water, carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur.

Energy flows directionally through ecosystems, entering as sunlight (or inorganic molecules for chemoautotrophs) and leaving as heat during the many transfers between trophic levels. However, the matter that makes up living organisms is conserved and recycled. The six most common elements associated with organic molecules—carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur—take a variety of chemical forms and may exist for long periods in the atmosphere, on land, in water, or beneath the Earth’s surface. Geologic processes, such as weathering, erosion, water drainage, and the subduction of the continental plates, all play a role in this recycling of materials. Because geology and chemistry have major roles in the study of this process, the recycling of inorganic matter between living organisms and their environment is called a biogeochemical cycle .

The cycling of these elements is interconnected. For example, the movement of water is critical for the leaching of nitrogen and phosphate into rivers, lakes, and oceans. Furthermore, the ocean itself is a major reservoir for carbon. Thus, mineral nutrients are cycled, either rapidly or slowly, through the entire biosphere, from one living organism to another, and between the biotic and abiotic world.

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the hydrologic cycle and why it is essential for all life on Earth

- Discuss the carbon cycle and why carbon is essential to all living things

- Discuss the nitrogen cycle and nitrogen’s role on Earth

- Discuss the phosphorus cycle and phosphorus’s role on Earth

- Discuss the sulfur cycle and sulfur’s role on Earth

The Hydrologic Cycle

Water contains hydrogen and oxygen, which is essential to all living processes. The hydrosphere is the area of the Earth where water movement and storage occurs: as liquid water on the surface and beneath the surface or frozen (rivers, lakes, oceans, groundwater, polar ice caps, and glaciers), and as water vapor in the atmosphere.

Water is the basis of all living processes. The human body is more than 1/2 water and human cells are more than 70 percent water. Thus, most land animals need a supply of fresh water to survive. However, when examining the stores of water on Earth, 97.5 percent of it is non-potable salt water (Figure 1). Of the remaining water, 99 percent is locked underground as water or as ice. Thus, less than 1 percent of fresh water is easily accessible from lakes and rivers. Many living things, such as plants, animals, and fungi, are dependent on the small amount of fresh surface water supply, a lack of which can have massive effects on ecosystem dynamics. Humans, of course, have developed technologies to increase water availability, such as digging wells to harvest groundwater, storing rainwater, and using desalination to obtain drinkable water from the ocean. Although this pursuit of drinkable water has been ongoing throughout human history, the supply of fresh water is still a major issue in modern times.

Figure 1. Only 2.5 percent of water on Earth is fresh water, and less than 1 percent of fresh water is easily accessible to living things.

Water cycling is extremely important to ecosystem dynamics. Water has a major influence on climate and, thus, on the environments of ecosystems, some located on distant parts of the Earth. Most of the water on Earth is stored for long periods in the oceans, underground, and as ice. Figure 2 illustrates the average time that an individual water molecule may spend in the Earth’s major water reservoirs. Residence time is a measure of the average time an individual water molecule stays in a particular reservoir. A large amount of the Earth’s water is locked in place in these reservoirs as ice, beneath the ground, and in the ocean, and, thus, is unavailable for short-term cycling (only surface water can evaporate).

Figure 2. This graph shows the average residence time for water molecules in the Earth’s water reservoirs.

There are various processes that occur during the cycling of water, shown in Figure 3. These processes include the following:

- evaporation/sublimation

- condensation/precipitation

- subsurface water flow

- surface runoff/snowmelt

The water cycle is driven by the sun’s energy as it warms the oceans and other surface waters. This leads to the evaporation (water to water vapor) of liquid surface water and the sublimation (ice to water vapor) of frozen water, which deposits large amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere. Over time, this water vapor condenses into clouds as liquid or frozen droplets and is eventually followed by precipitation (rain or snow), which returns water to the Earth’s surface. Rain eventually permeates into the ground, where it may evaporate again if it is near the surface, flow beneath the surface, or be stored for long periods. More easily observed is surface runoff: the flow of fresh water either from rain or melting ice. Runoff can then make its way through streams and lakes to the oceans or flow directly to the oceans themselves.

Rain and surface runoff are major ways in which minerals, including carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur, are cycled from land to water. The environmental effects of runoff will be discussed later as these cycles are described.

Figure 3. Water from the land and oceans enters the atmosphere by evaporation or sublimation, where it condenses into clouds and falls as rain or snow. Precipitated water may enter freshwater bodies or infiltrate the soil. The cycle is complete when surface or groundwater reenters the ocean. (credit: modification of work by John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS)

The Carbon Cycle

Carbon is the second most abundant element in living organisms. Carbon is present in all organic molecules, and its role in the structure of macromolecules is of primary importance to living organisms. Carbon compounds contain especially high energy, particularly those derived from fossilized organisms, mainly plants, which humans use as fuel. Since the 1800s, the number of countries using massive amounts of fossil fuels has increased. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, global demand for the Earth’s limited fossil fuel supplies has risen; therefore, the amount of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere has increased. This increase in carbon dioxide has been associated with climate change and other disturbances of the Earth’s ecosystems and is a major environmental concern worldwide. Thus, the “carbon footprint” is based on how much carbon dioxide is produced and how much fossil fuel countries consume.

The carbon cycle is most easily studied as two interconnected sub-cycles: one dealing with rapid carbon exchange among living organisms and the other dealing with the long-term cycling of carbon through geologic processes. The entire carbon cycle is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Carbon dioxide gas exists in the atmosphere and is dissolved in water. Photosynthesis converts carbon dioxide gas to organic carbon, and respiration cycles the organic carbon back into carbon dioxide gas. Long-term storage of organic carbon occurs when matter from living organisms is buried deep underground and becomes fossilized. Volcanic activity and, more recently, human emissions, bring this stored carbon back into the carbon cycle. (credit: modification of work by John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS)

The Biological Carbon Cycle

Living organisms are connected in many ways, even between ecosystems. A good example of this connection is the exchange of carbon between autotrophs and heterotrophs within and between ecosystems by way of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is the basic building block that most autotrophs use to build multi-carbon, high energy compounds, such as glucose. The energy harnessed from the sun is used by these organisms to form the covalent bonds that link carbon atoms together. These chemical bonds thereby store this energy for later use in the process of respiration. Most terrestrial autotrophs obtain their carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere, while marine autotrophs acquire it in the dissolved form (carbonic acid, H 2 CO 3 − ). However carbon dioxide is acquired, a by-product of the process is oxygen. The photosynthetic organisms are responsible for depositing approximately 21 percent oxygen content of the atmosphere that we observe today.

Heterotrophs and autotrophs are partners in biological carbon exchange (especially the primary consumers, largely herbivores). Heterotrophs acquire the high-energy carbon compounds from the autotrophs by consuming them, and breaking them down by respiration to obtain cellular energy, such as ATP. The most efficient type of respiration, aerobic respiration, requires oxygen obtained from the atmosphere or dissolved in water. Thus, there is a constant exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the autotrophs (which need the carbon) and the heterotrophs (which need the oxygen). Gas exchange through the atmosphere and water is one way that the carbon cycle connects all living organisms on Earth.

The Biogeochemical Carbon Cycle

The movement of carbon through the land, water, and air is complex, and in many cases, it occurs much more slowly geologically than as seen between living organisms. Carbon is stored for long periods in what are known as carbon reservoirs, which include the atmosphere, bodies of liquid water (mostly oceans), ocean sediment, soil, land sediments (including fossil fuels), and the Earth’s interior.

As stated, the atmosphere is a major reservoir of carbon in the form of carbon dioxide and is essential to the process of photosynthesis. The level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is greatly influenced by the reservoir of carbon in the oceans. The exchange of carbon between the atmosphere and water reservoirs influences how much carbon is found in each location, and each one affects the other reciprocally. Carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) from the atmosphere dissolves in water and combines with water molecules to form carbonic acid, and then it ionizes to carbonate and bicarbonate ions:

[latex]\begin{array}{rrcl}\text{Step 1:}&\text{CO}_2\text{(atmospheric)}&\longleftrightarrow&\text{CO}_2\text{(dissolved)}\\\text{Step 2:}&\text{CO}_2\text{(dissolved)}+\text{H}_2\text{O}&\longleftrightarrow&\text{H}_2\text{CO}_3\text{(carbonic acid)}\\\text{Step 3:}&\text{H}_2\text{CO}_3&\longleftrightarrow&\text{H}^{+}+\text{HCO}^-_3\text{(bicarbonate ion)}\\\text{Step 4:}&\text{HCO}^-_3&\longleftrightarrow&\text{H}^{+}+\text{CO}^{2-}_{3}\text{(carbonate ion)}\end{array}[/latex]

The equilibrium coefficients are such that more than 90 percent of the carbon in the ocean is found as bicarbonate ions. Some of these ions combine with seawater calcium to form calcium carbonate (CaCO 3 ), a major component of marine organism shells. These organisms eventually form sediments on the ocean floor. Over geologic time, the calcium carbonate forms limestone, which comprises the largest carbon reservoir on Earth.

On land, carbon is stored in soil as a result of the decomposition of living organisms (by decomposers) or from weathering of terrestrial rock and minerals. This carbon can be leached into the water reservoirs by surface runoff. Deeper underground, on land and at sea, are fossil fuels: the anaerobically decomposed remains of plants that take millions of years to form. Fossil fuels are considered a non-renewable resource because their use far exceeds their rate of formation. A non-renewable resource , such as fossil fuel, is either regenerated very slowly or not at all. Another way for carbon to enter the atmosphere is from land (including land beneath the surface of the ocean) by the eruption of volcanoes and other geothermal systems. Carbon sediments from the ocean floor are taken deep within the Earth by the process of subduction : the movement of one tectonic plate beneath another. Carbon is released as carbon dioxide when a volcano erupts or from volcanic hydrothermal vents.

Carbon dioxide is also added to the atmosphere by the animal husbandry practices of humans. The large numbers of land animals raised to feed the Earth’s growing population results in increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere due to farming practices and the respiration and methane production. This is another example of how human activity indirectly affects biogeochemical cycles in a significant way. Although much of the debate about the future effects of increasing atmospheric carbon on climate change focuses on fossils fuels, scientists take natural processes, such as volcanoes and respiration, into account as they model and predict the future impact of this increase.

Video Review

This video talks about two of the biogeochemical cycles: carbon and water. The hydrologic cycle describes how water moves on, above, and below the surface of the Earth, driven by energy supplied by the sun and wind. The carbon cycle does the same . . . for carbon!

The Nitrogen Cycle

Nitrogen is a major component of our nucleic acids and proteins and is critical to human agriculture. Getting nitrogen into the living world is difficult. Plants and phytoplankton are not equipped to incorporate nitrogen from the atmosphere (which exists as tightly bonded, triple covalent N 2 ) even though this molecule comprises approximately 78 percent of the atmosphere. Nitrogen enters the living world via free-living and symbiotic bacteria, which incorporate nitrogen into their macromolecules through nitrogen fixation (conversion of N 2 ). Cyanobacteria live in most aquatic ecosystems where sunlight is present; they play a key role in nitrogen fixation. Cyanobacteria are able to use inorganic sources of nitrogen to “fix” nitrogen. Rhizobium bacteria live symbiotically in the root nodules of legumes (such as peas, beans, and peanuts) and provide them with the organic nitrogen they need. Free-living bacteria, such as Azotobacter , are also important nitrogen fixers.

Organic nitrogen is especially important to the study of ecosystem dynamics since many ecosystem processes, such as primary production and decomposition, are limited by the available supply of nitrogen. As shown in Figure 5, the nitrogen that enters living systems by nitrogen fixation is successively converted from organic nitrogen back into nitrogen gas by bacteria. This process occurs in three steps in terrestrial systems: ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification. First, the ammonification process converts nitrogenous waste from living animals or from the remains of dead animals into ammonium (NH 4 + ) by certain bacteria and fungi. Second, the ammonium is converted to nitrites (NO 2 − ) by nitrifying bacteria, such as Nitrosomonas , through nitrification. Subsequently, nitrites are converted to nitrates (NO 3 − ) by similar organisms. Third, the process of denitrification occurs, whereby bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Clostridium , convert the nitrates into nitrogen gas, allowing it to re-enter the atmosphere.

Figure 5. Nitrogen enters the living world from the atmosphere via nitrogen-fixing bacteria. This nitrogen and nitrogenous waste from animals is then processed back into gaseous nitrogen by soil bacteria, which also supply terrestrial food webs with the organic nitrogen they need. (credit: modification of work by John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS)

Practice Question

Which of the following statements about the nitrogen cycle is false?

- Ammonification converts organic nitrogenous matter from living organisms into ammonium (NH 4 + ).

- Denitrification by bacteria converts nitrates (NO 3 − ) to nitrogen gas (N 2 ).

- Nitrification by bacteria converts nitrates (NO 3 − ) to nitrites (NO 2 − ).

- Nitrogen fixing bacteria convert nitrogen gas (N 2 ) into organic compounds.

Human activity can release nitrogen into the environment by two primary means: the combustion of fossil fuels, which releases different nitrogen oxides, and by the use of artificial fertilizers in agriculture, which are then washed into lakes, streams, and rivers by surface runoff. Atmospheric nitrogen is associated with several effects on Earth’s ecosystems including the production of acid rain (as nitric acid, HNO 3 ) and greenhouse gas (as nitrous oxide, N 2 O) potentially causing climate change. A major effect from fertilizer runoff is saltwater and freshwater eutrophication , a process whereby nutrient runoff causes the excess growth of microorganisms, depleting dissolved oxygen levels and killing ecosystem fauna.

A similar process occurs in the marine nitrogen cycle, where the ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification processes are performed by marine bacteria. Some of this nitrogen falls to the ocean floor as sediment, which can then be moved to land in geologic time by uplift of the Earth’s surface and thereby incorporated into terrestrial rock. Although the movement of nitrogen from rock directly into living systems has been traditionally seen as insignificant compared with nitrogen fixed from the atmosphere, a recent study showed that this process may indeed be significant and should be included in any study of the global nitrogen cycle.

The Phosphorus Cycle

Phosphorus, a major component of nucleic acid (along with nitrogen), is an essential nutrient for living processes; it is also a major component of phospholipids, and, as calcium phosphate, makes up the supportive components of our bones. Phosphorus is often the limiting nutrient (necessary for growth) in aquatic ecosystems (Figure 6).

Figure 6. In nature, phosphorus exists as the phosphate ion (PO 4 3− ). Weathering of rocks and volcanic activity releases phosphate into the soil, water, and air, where it becomes available to terrestrial food webs. Phosphate enters the oceans via surface runoff, groundwater flow, and river flow. Phosphate dissolved in ocean water cycles into marine food webs. Some phosphate from the marine food webs falls to the ocean floor, where it forms sediment. (credit: modification of work by John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS)

Phosphorus occurs in nature as the phosphate ion (PO 4 3− ). In addition to phosphate runoff as a result of human activity, natural surface runoff occurs when it is leached from phosphate-containing rock by weathering, thus sending phosphates into rivers, lakes, and the ocean. This rock has its origins in the ocean. Phosphate-containing ocean sediments form primarily from the bodies of ocean organisms and from their excretions. However, in remote regions, volcanic ash, aerosols, and mineral dust may also be significant phosphate sources. This sediment then is moved to land over geologic time by the uplifting of areas of the Earth’s surface.

Phosphorus is also reciprocally exchanged between phosphate dissolved in the ocean and marine ecosystems. The movement of phosphate from the ocean to the land and through the soil is extremely slow, with the average phosphate ion having an oceanic residence time between 20,000 and 100,000 years.

Phosphorus is one of the main ingredients in artificial fertilizers used in agriculture and their associated environmental impacts on our surface water. Excess phosphorus and nitrogen that enters these ecosystems from fertilizer runoff and from sewage causes excessive growth of microorganisms and depletes the dissolved oxygen, which leads to the death of many ecosystem fauna, such as shellfish and finfish. This process is responsible for dead zones in lakes and at the mouths of many major rivers (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Dead zones occur when phosphorus and nitrogen from fertilizers cause excessive growth of microorganisms, which depletes oxygen and kills fauna. Worldwide, large dead zones are found in coastal areas of high population density. (credit: NASA Earth Observatory)

A dead zone is an area within a freshwater or marine ecosystem where large areas are depleted of their normal flora and fauna; these zones can be caused by eutrophication, oil spills, dumping of toxic chemicals, and other human activities. The number of dead zones has been increasing for several years, and more than 400 of these zones were present as of 2008. One of the worst dead zones is off the coast of the United States in the Gulf of Mexico, where fertilizer runoff from the Mississippi River basin has created a dead zone of over 8463 square miles. Phosphate and nitrate runoff from fertilizers also negatively affect several lake and bay ecosystems including the Chesapeake Bay in the eastern United States.

Chesapeake Bay

Figure 8. This (a) satellite image shows the Chesapeake Bay, an ecosystem affected by phosphate and nitrate runoff. A (b) member of the Army Corps of Engineers holds a clump of oysters being used as a part of the oyster restoration effort in the bay. (credit a: modification of work by NASA/MODIS; credit b: modification of work by U.S. Army)

The Chesapeake Bay has long been valued as one of the most scenic areas on Earth; it is now in distress and is recognized as a declining ecosystem. In the 1970s, the Chesapeake Bay was one of the first ecosystems to have identified dead zones, which continue to kill many fish and bottom-dwelling species, such as clams, oysters, and worms. Several species have declined in the Chesapeake Bay due to surface water runoff containing excess nutrients from artificial fertilizer used on land. The source of the fertilizers (with high nitrogen and phosphate content) is not limited to agricultural practices. There are many nearby urban areas and more than 150 rivers and streams empty into the bay that are carrying fertilizer runoff from lawns and gardens. Thus, the decline of the Chesapeake Bay is a complex issue and requires the cooperation of industry, agriculture, and everyday homeowners.

Of particular interest to conservationists is the oyster population; it is estimated that more than 200,000 acres of oyster reefs existed in the bay in the 1700s, but that number has now declined to only 36,000 acres. Oyster harvesting was once a major industry for Chesapeake Bay, but it declined 88 percent between 1982 and 2007. This decline was due not only to fertilizer runoff and dead zones but also to overharvesting. Oysters require a certain minimum population density because they must be in close proximity to reproduce. Human activity has altered the oyster population and locations, greatly disrupting the ecosystem.

The restoration of the oyster population in the Chesapeake Bay has been ongoing for several years with mixed success. Not only do many people find oysters good to eat, but they also clean up the bay. Oysters are filter feeders, and as they eat, they clean the water around them. In the 1700s, it was estimated that it took only a few days for the oyster population to filter the entire volume of the bay. Today, with changed water conditions, it is estimated that the present population would take nearly a year to do the same job.

Restoration efforts have been ongoing for several years by non-profit organizations, such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. The restoration goal is to find a way to increase population density so the oysters can reproduce more efficiently. Many disease-resistant varieties (developed at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science for the College of William and Mary) are now available and have been used in the construction of experimental oyster reefs. Efforts to clean and restore the bay by Virginia and Delaware have been hampered because much of the pollution entering the bay comes from other states, which stresses the need for inter-state cooperation to gain successful restoration.

The new, hearty oyster strains have also spawned a new and economically viable industry—oyster aquaculture—which not only supplies oysters for food and profit, but also has the added benefit of cleaning the bay.

Many organisms require nitrogen and phosphorus. This video explains just how they go about getting them via the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles.

The Sulfur Cycle

Sulfur, an essential element for the macromolecules of living things, is released into the atmosphere by the burning of fossil fuels, such as coal. As a part of the amino acid cysteine, it is involved in the formation of disulfide bonds within proteins, which help to determine their 3-D folding patterns, and hence their functions. As shown in Figure 9, sulfur cycles between the oceans, land, and atmosphere. Atmospheric sulfur is found in the form of sulfur dioxide (SO 2 ) and enters the atmosphere in three ways: from the decomposition of organic molecules, from volcanic activity and geothermal vents, and from the burning of fossil fuels by humans.

Figure 9. Sulfur dioxide from the atmosphere becomes available to terrestrial and marine ecosystems when it is dissolved in precipitation as weak sulfuric acid or when it falls directly to the Earth as fallout. Weathering of rocks also makes sulfates available to terrestrial ecosystems. Decomposition of living organisms returns sulfates to the ocean, soil and atmosphere. (credit: modification of work by John M. Evans and Howard Perlman, USGS)

Figure 10. At this sulfur vent in Lassen Volcanic National Park in northeastern California, the yellowish sulfur deposits are visible near the mouth of the vent.

On land, sulfur is deposited in four major ways: precipitation, direct fallout from the atmosphere, rock weathering, and geothermal vents (Figure 10). Atmospheric sulfur is found in the form of sulfur dioxide (SO 2 ), and as rain falls through the atmosphere, sulfur is dissolved in the form of weak sulfuric acid (H 2 SO 4 ). Sulfur can also fall directly from the atmosphere in a process called fallout . Also, the weathering of sulfur-containing rocks releases sulfur into the soil. These rocks originate from ocean sediments that are moved to land by the geologic uplifting of ocean sediments. Terrestrial ecosystems can then make use of these soil sulfates (SO 4 − ), and upon the death and decomposition of these organisms, release the sulfur back into the atmosphere as hydrogen sulfide (H 2 S) gas.

Sulfur enters the ocean via runoff from land, from atmospheric fallout, and from underwater geothermal vents. Some ecosystems rely on chemoautotrophs using sulfur as a biological energy source. This sulfur then supports marine ecosystems in the form of sulfates.

Human activities have played a major role in altering the balance of the global sulfur cycle. The burning of large quantities of fossil fuels, especially from coal, releases larger amounts of hydrogen sulfide gas into the atmosphere. As rain falls through this gas, it creates the phenomenon known as acid rain. Acid rain is corrosive rain caused by rainwater falling to the ground through sulfur dioxide gas, turning it into weak sulfuric acid, which causes damage to aquatic ecosystems. Acid rain damages the natural environment by lowering the pH of lakes, which kills many of the resident fauna; it also affects the man-made environment through the chemical degradation of buildings. For example, many marble monuments, such as the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, have suffered significant damage from acid rain over the years. These examples show the wide-ranging effects of human activities on our environment and the challenges that remain for our future.

Check Your Understanding

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered in the previous section. This short quiz does not count toward your grade in the class, and you can retake it an unlimited number of times.

Use this quiz to check your understanding and decide whether to (1) study the previous section further or (2) move on to the next section.

- Introduction to Biogeochemical Cycles. Authored by : Shelli Carter and Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Biology. Provided by : OpenStax CNX. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected] . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- The Hydrologic and Carbon Cycles: Always Recycle!. Authored by : CrashCourse. Located at : https://youtu.be/2D7hZpIYlCA . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Nitrogen & Phosphorus Cycles: Always Recycle! Part 2. Authored by : CrashCourse. Located at : https://youtu.be/leHy-Y_8nRs . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Evolution of biogeochemical cycles under anthropogenic loads: Limits impacts

- Published: 01 October 2017

- Volume 55 , pages 841–860, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- T. I. Moiseenko 1

439 Accesses

29 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Human activities pathogenically modify biogeochemical cycles via introducing vast amounts of chemical elements and compounds into biotic cycles and inducing evolutionary transformations of the organic world of the biosphere. The adverse phenomena develop cascadewise, as is illustrated by the increase in the content of carbon dioxide and acid-forming compounds, enrichment of aquatic environments by metals, and pollution with persistent organic pollutants and biogenic elements. Analogies with the past are utilized to estimate the possible implications of the evolution of anthropogenically induced processes. The organic world is proved to react to anthropogenic impacts by means of active microevolutionary processes. The key reaction mechanisms of organisms and transformations of populations and ecosystems under the modified conditions are demonstrated. A review of literature data is used to show how anthropogenic emissions of CO 2 , NO x , P, toxic compounds and elements increases on a global scale, and how ocean acidification, eutrophication, water withdrawal, etc. are simultaneously enhanced. The methodology of estimating anthropogenic loads is discussed as a scientifically grounded strategy of minimizing anthropogenic impacts on natural ecosystems.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction to Global Carbon Cycling: An Overview of the Global Carbon Cycle

Ocean Acidification

Environmental Impacts—Marine Biogeochemistry

Explore related subjects.

- Environmental Chemistry

T. M. Ansari, I. L. Marr, and N. Tariq, “Heavy metals in marine pollution perspective: a mini review,” J. Appl. Sci. 4 , 1–20 (2004).

Article Google Scholar

S. Barker and A. Ridgwell, “Ocean acidification,” Nat. Educ. Knowl. 3 (10), 21–28 (2012).

Google Scholar

M. Begon, H. Harper, and C. Townsend, Ecology: Individuals, Populations, and Communities (Blaclwell Science, 1986).

M. Beman, C. E. Chow, A. L. King, Y. Feng, J. A. Fuhrman, A. Andersson, N. R. Bates, B. N. Popp, et al., “Global declines in oceanic nitrification rates as a consequence of ocean acidification,” Environ. Sci. 108 (1), 208–213 (2011).

J. Bijma, M. Barange, L. Brander, et al. “Impacts of ocean acidification,” Science 320 , 336–340 (2008).

V. N. Bol’shakov and T. I. Moiseenko, “Anthropogenic evolution of animals: facts and their interpretation,” Ekologiya 5 , 323–332 (2009).

G. W. Bryan, “Heavy metal contamination in the sea,” Marine Pollution , Ed. by R. Johnston (Academic Press, New York–San Francisco, 1976), pp. 185–302.

M. P. Cajaraville, L. Houser, G. Carvalho, et al. “Genetic damage and the molecular/cellular response to pollution,” in Effects of Pollution on Fish. Molecular Effect and Population Responses , Ed. by A. J. Lawrence and K. L. Hemingway (Blackwell Science Ltd, New York, 2003), pp. 14–82.

Chapter Google Scholar

J. W. Castle and J. H. Rodgers, “Hypothesis for the role of toxin-producing algae in Phanerozoic mass extinctions based on evidence from the geologic record and modern environments,” Environ. Geosci. 16 , 1–239 (2009).

R. K. Chesser and D. W Sugg, “Toxicant as selective agents in population and community dynamics,” Ecotoxicology: a Hierarchical Treatment , Ed. by M. C. Newman, and Ch. H. Jagoe (Levis, New York, 1996), pp. 293–317.

M. O. Clarkson, S. A. Kasemann, R. A. Wood, T. M. Lenton, S. J. Daines, S. Richoz, F. Ohnemueller, et al., “Ocean acidification and the Permo-Triassic mass extinction,” Science 348 (6231), 229–232 (2015).

Climate Change 2013: Synthesis Report. (2014) IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (ar5). https://www.ipcc-wg1.unibe. ch/ar5/ar5.html

L. L. Demina, “Quantification of the role of organisms in the geochemical migration of trace metals in the ocean,” Geochem. Int. 53 (3), 224–240 (2015).

M. N. Depledge, “Genetic ecotoxicology: an overview,” J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 200 (1–2), 57–66 (1996).

T. Dobzhansky, Genetics and Evolutionary Process (Columbia University, New York, 1970).

Dynamics of Population Gene Pools at Anthropogenic Impacts , Ed. by Yu. P, Altukhova (Nauka, Moscow, 2004) [in Russian].

EPA. (United States Environmental Protection Agency) Persistent Bioaccumulative Toxic. Persistence, Bioaccumulation and Toxicity (Parametrix Inc., Washington, 2017). https://www.epa.gov/toxics-release-inventory-tri-program/persistent-bioaccumulative-toxic-pbt-chemicalsrules-under-tri.

T. A. Erwin, “An evolutionary basis for conservation strategies,” Science 253 , 750–752 (1991).

C. D. Evans, T. Don, D. T. Monteith, D. Fowler, J. N. Cape, and S. Brayshaw, “Hydrochloric acid: an overlooked driver of environmental change,” Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 (5), 1887–1895 (2011).

A. P. Fersman, Geochemistry (ONTI-KhIMTEORET, Leningrad, 1934), Vol. 2 [in Russian].

W. F. Fitzgerald, C. H. Lamborg, R. Chad et al., Marine biogeochemical cycling of mercury, Chem. Rev. 107 , 641–662 (2007).

E. M. Galimov, “Role of low solar emittance in the biosphere history,” Geochem. Int. (in press).

E. M. Galimov, Phenomenon of Life: Between Equilibrium and Non-linearity. Origin and Principles of Evolution , 3 rd . Ed. (LIBROKOM, Moscow, 2009) [in Russian].

J. N. Galloway, “Acid deposition: perspectives in time and space,” Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 85 , 15–24 (1995).

J. N. Galloway and E. B. Cowling, “Reactive nitrogen and the world: two hundred years of change,” AMBIO 31 , 64–71 (2002).

Ø. A. Garmo, B. L. Skjelkvåle, H. D. de Wit, L. Colombo, C. Curtis, J. Fölster, A. Hoffmann, J. Hruška, et al. “Trends in surface water chemistry in acidified areas in Europe and North America from 1990 to 2008,” Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 225 , 1–14 (2014).

E. Gautheier, I. Fortier, F. Courchesne et al., “Aluminium form in drinking water and risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” Environ. Res. 84 , 234–246 (2000).

A. M. Gilyarov, “Development of the evolutionary approach as explanation of beginning in the ecology,” Zh. Obshch. Biol. 64 (1), 3–22 (2003).

N. Gruber and J. N. Galloway, “An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle,” Nature 451 , 293–296 (2008).

J. M. Guinotte and V. J. Fabry, “Ocean acidification and its potential effects on marine ecosystems,” An. N-Y. Academy Sci. 1134 , 320–342 (2008).

D. M. Iglesias-Rodriguez, P. R. Halloran, and E. M. Rosalind, “Phytoplankton calcification in a high-CO 2 World,” World Sci. 320 , 336–340 (2008).

B. C. Kelly M. G. Ikonomou, J. D. Blair, A. E. Morin, and F. A. Gobas, “Food web–specific biomagnification of persistent organic pollutants,” Science 317 (5835), 236–239 (2007).

E. I. Kolchinskii, Evolution of the Biosphere (Nauka, Leningrad, 1990) [in Russian].

V. V. Koval’skii, Birth and Evolution of the Biosphere , Usp. Sovremen. Biol. 55 (1), 45–67 (1963).

J. C. I. Kuylenstierna, M. Rodhe, S. Cinderby, and K. Hicks, “Acidification in developing countries: ecosystem sensitivity and the critical load approach on a global scale,” AMBIO 30 , 20–28 (2001).

F. T. Machenzie, L. M. Ver, and A. Lerman, “Centuryscale nitrogen and phosphorus controls of the carbon cycle,” Chem. Geol. 190 , 13–32 (2002).

T. I. Moiseenko, “Effect of acidification on aqueous ecosystems,” Ekologiya 2 , 110–119 (2005).

T. I. Moiseenko, “The theory of critical loads and assessment of the effect of acid-forming substances on surface waters,” Dokl. Earth Sci. 378 , 468–471 (2001).

Moiseenko, T. I. Aqueous Ecotoxicology: Fundamental and Applied Aspects (Nauka, Moscow, 2009) [in Russian].

T. I. Moiseenko, “Stability of aqueous ecosystems and their variability under toxic pollution conditions,” Ekologiya 6 , 441–448 (2011).

T. I. Moiseenko, “Impact of geochemical factors of aquatic environment on the metal bioaccumulation in fish,” Geochem. Int. 53 (3), 213–223 (2015).

T. I. Moiseenko and I. I. Rudneva, “Global pollution and nitrogen functions in the hydrosphere,” Dokl. Earth Sci. 420 , 676–680 (2008).

T. I. Moiseenko, L. P. Kudryavtseva, and N. A. Gashkina, Scattered Elements in the Terrestrial Surface Waters: Technophile Properties, Bioaccumulation, and Ecotoxicology (Nauka, Moscow, 2006) [in Russian].

T. I. Moiseenko, A. N. Sharov, O. I. Vandish, L. P. Kudryavtseva, N. A. Gashkina, and C. Rose, “Long-term modification of arctic lake ecosystem: reference condition, degradation and recovery,” Limnologica 39 (1), 1–13 (2009).

T. I. Moiseenko, M. I. Dinu, and M. M. Bazova, “Longterm changes in the water chemistry of subarctic lakes as a response to reduction of air pollution: case study in the Kola North, Russia,” Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 226 (98), 1–12 (2015).

T. I. Moiseenko, N. A. Gashkina, and M. I. Dinu, “Enrichment of surface water by elements: effects of air pollution, acidification and eutrophication,” Environ. Process. 3 , 39–58 (2016).

T. I. Moiseenko, N. A. Gashkina, and M. I. Dinu, Water Acidification: Vulnerability and Critical Loading (URRS, Moscow, 2016) [in Russian].

D. T. Monteith, J. L. Stoddard, C. D. Evans, M. Forsius, T. Hogasen, A. Wilander, B. L. Skelkvale et al., “Dissolved organic carbon trends resulting from changes in atmospheric deposition chemistry,” Nature 450 , 537–546 (2007).

J. W. Moore, and S. Ramamoorthy, Heavy Metals in Natural Waters. Applied Monitoring and Impact Assessment (Springer-Verlag, New York, 1984).

Book Google Scholar

NASSA Report Vital Signs of the Planet: Global Climate Change and Global Warming (2014). https://climate. nasa.gov/news/2365/seven-case-studies-in-carbon-andclimate.

E. P. Odum, Fundamentals of Ecology (Springer, 1961).

E. R. Pianka, Evolutionary Ecology (Harper and Row, New York, 1974).

A. I. Pogue and W. J. Lukiw, “The mobilization of aluminum into the biosphere,” Front. Neurol. 5 , 262–271 (2014).

I. Prigogine, and I. Stengers, Order out of Chaos. Man’s New Dialogue with Nature (Heinemann, London, 1984).

Problems of the Origin and Evolution of the Biosphere, Galimov, E. M. Ed., (Librikom, Moscow,) [in Russian]

J. Rockström, W. Steffen, K. Noone, Å. Persson, F. S. Chapin III, E. F. Lambin, T. M. Lenton, M. Scheffer et al., “A safe operating space for humanity,” Nature 461 , 472–475 (2009).

I. Semiletov and O. Gustafsson, “Massive remobilization of permafrost carbon during post-glacial warming,” Nat. Commun. 7 , 1–9 (2016).

I. Semiletov, I. Pipko, O. Gustafsson, L. G. Anderson, V. Sergienko, S. Pugach, O. Dudarev, and A. Charkin, “Acidification of East Siberian Arctic Shelf waters through addition of freshwater and terrestrial carbon,” Nat. Geosci. 9 , 361–365 (2016).

S. S. Shvarts, Ecological Tendencies of Evolution (Nauka, Moscow, 1980) [in Russian].

S. C. Stearns, The Evolution of Life History (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1992)

Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. Report of the Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee on the Work of its Ninth Meeting (2013).

T. Tesi, F. Muschitiello, R. H. Smittenberg, M. Jakobsson, J. E. Vonk, P. Hill, A. Andersson, and N. Kirchner et al. Nat. Communic. 7, 1–9 .

E. V. Venitsianov and A. P. Lepikhin, Physicochemical Principles of Simulation of the Migration and Transformation of Heavy Metals in Natural Waters (Ros-NIIVKh, Yekaterinburg, 2002) [in Russian].

V. I. Vernadsky, “Biogeochemical problems,” Tr. Biogeokhim. Lab., 16 , 10–54 (1980).

V. I. Vernadsky, Biosphere and Noosphere (Nauka, Moscow, 1989) [in Russian]

V. I. Vernadsky, Scientific Ideas as Planetary Phenomenon (Nauka, Moscow, 1991) [in Russian].

C. H. Walker, S. P. Hopkin, R. M. Sibly, and D. B. Peakall, Principles of Ecotoxicology (2nd Edition) (Taylor & Francis Ltd, London, 2001).

World’s Mineral Resources as of January 1, 1997. A Statistic Handbook (Official Edition) of “Aerogeologiya”, Ministry of Nature Management of FGUNPP (Inform–Analit. Ts. Mineral, Moscow, 1998) [in Russian].

World’s Mineral Resources as of January 1, 2001. A Statistic Handbook (Official Edition) of “Aerogeologiya”, Ministry of Nature Management of FGUNPP (Inform–Analit. Ts. Mineral, Moscow, 2002) [in Russian].

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Vernadsky Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry (GEOKhI), Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 119991, Russia

T. I. Moiseenko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author