| | Other Funday Articles | | | | | | -- Maths | | | -- Poem for the week | | | | | | | | | |   National Hero of Sri Lanka| National Hero of Sri Lanka |

|---|

| | | Type | Title |

|---|

| Awarded for | "An especially meritorious contribution to the historical struggle or national interests of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka" |

|---|

| Presented by | the |

|---|

| Total recipients | Unknown; approximately 135 in the Island's history. |

|---|

| Precedence |

|---|

| Next (higher) | |

|---|

| Next (lower) | , |

|---|

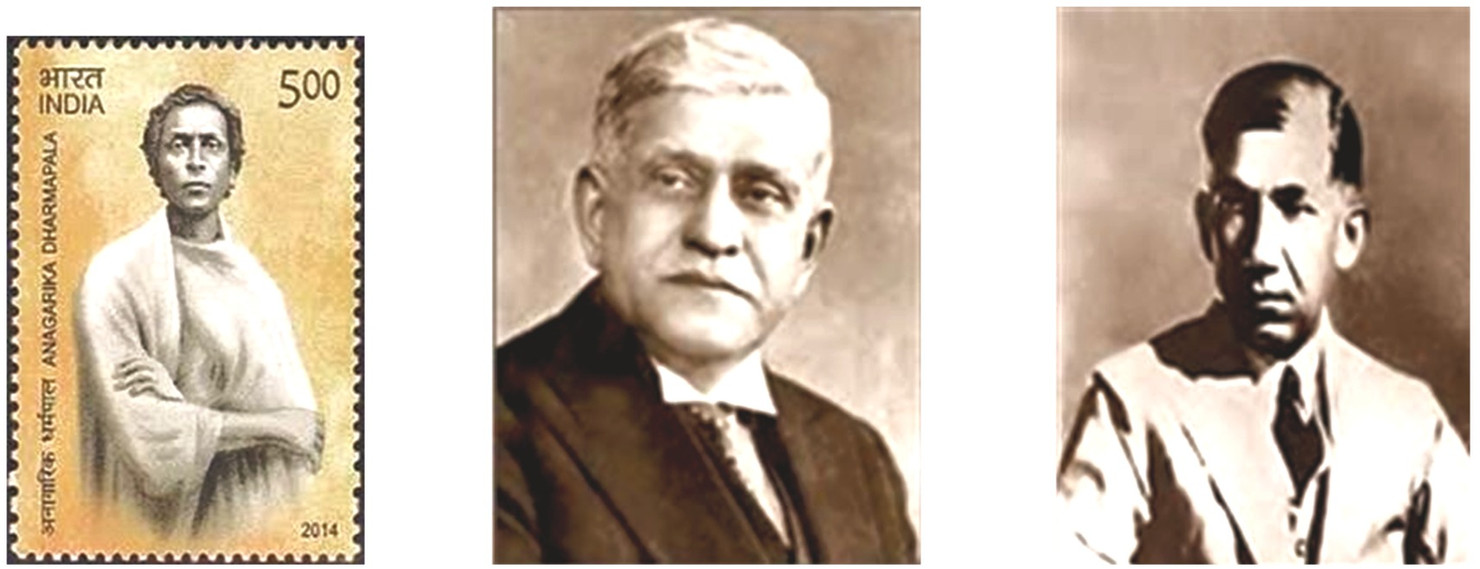

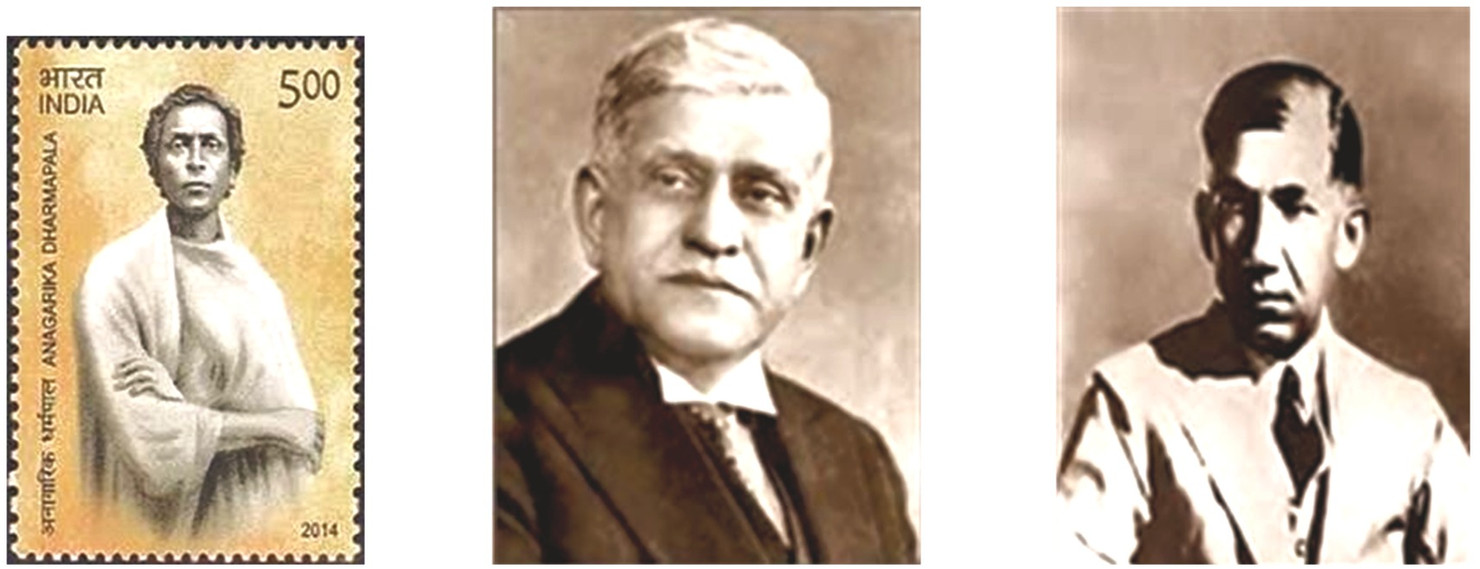

National Hero is a status an individual can receive in Sri Lanka for those who are considered to have played a major role in fighting for the freedom of the country. [1] The status is conferred by the President of Sri Lanka . The recipients of the award are celebrated on a Sri Lankan national holiday, National Heroes’ Day, held annually on 22 May. Every year, the President and general public pay tribute by observing a two minutes silence in their memory. [2] The individuals are also celebrated on Sri Lanka Independence Day , held on 4 February. In this, the President or Prime Minister will typically address the nation with a speech honouring the National Heroes. The award has only been awarded to Sri Lankan citizens , but is not limited to this group. History of the awardMatale rebellion, sri lankan independence movement, bibliography. The award of "National Hero of Sri Lanka" is currently the supreme civilian decoration in precedence in Sri Lanka . [3] [4] To date, the award has only been awarded posthumously . [5] The status of ‘Sri Lanka National Hero’ is a civil honour bestowed on an individual recognised and declared as ‘Patriotic Hero’ who fought for the freedom of the motherland. [4] [6] The award focuses on those who led the Uva Wellassa Great Rebellion (1817–1818), the Matale rebellion (1848) and, the Sri Lankan independence movement . [7] [8] [9] [10] From 1948 to 1972, the nation was known as the Dominion of Ceylon , with its national day, known as Sri Lanka Independence Day being held annually on 4 February. [11] [12] It declared itself a republic on 22 May 1972. [13] Yearly, the National Heroes are celebrated on this day . [14] [15] Recipients of the award range from the 18th century to the 20th century. [16] The recipients include Pandara Vanniyan , a Vanni chieftain , who died during a revolt against the British and Dutch in Sri Lanka. [17] Other recipients are 19 leaders of the Great Rebellion of 1817–18 (including Keppetipola Disawe , late Desave of Ouva), 49 participants of the Great Rebellion of 1817–18 who were sentenced to death by the Martial Court and 32 participants of the Great Rebellion of 1817–18 who were declared as "betrayers" and expelled to Mauritius by the Martial Court. [18] [9] [19] The final 2 groups were made national heroes on 11 September 2017. [20] [21] The 19 Leaders of the Great revolution were made National Heroes on 8 December 2016. [22] [23] The Matale rebellion , also known as the Rebellion of 1848 , took place in Ceylon against the British colonial government under Governor Lord Torrington, 7th Viscount Torrington . [24] It marked a transition from the classic feudal form of anti-colonial revolt to modern independence struggles. [25] It was fundamentally a peasant revolt . [26] For their role in the rebellion, Puran Appu and Gongalegoda Banda were made National Heroes. [27] The Sri Lankan independence movement was a peaceful political movement which was aimed at achieving independence and self-rule for the country of Sri Lanka , then British Ceylon , from the British Empire . [28] [29] The switch of powers was generally known as peaceful transfer of power from the British administration to Ceylon representatives, a phrase that implies considerable continuity with a colonial era that lasted 400 years. [30] It was initiated around the turn of the 20th century and led mostly by the educated middle class. [31] It succeeded when, on 4 February 1948, Ceylon was granted independence as the Dominion of Ceylon . [32] [33] Dominion status within the British Commonwealth was retained for the next 24 years until 22 May 1972 when it became a republic and was renamed the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka . [13] [34] The following persons were awarded as "National Heroes of Sri Lanka" for the part they played in the Sri Lankan independence movement . List of recipients:- Anagarika Dharmapala [35]

- C. W. W. Kannangara [35]

- Cheruka Weerakoon [35]

- D. R. Wijewardena [35]

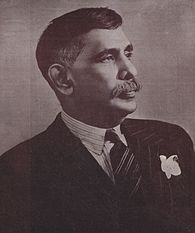

- Don Stephen Senanayake [35]

- E. W. Perera [35]

- Fredrick Richard Senanayake [35]

- Henry Pedris [35]

- James Peiris [35]

- Ponnambalam Arunachalam [35]

- Ponnambalam Ramanathan [35]

- Tuan Burhanudeen Jayah [35]

- A. Ekanayake Gunasinha

- Arthur V. Dias

- Charles Edgar Corea

- Sir Don Baron Jayatilaka

- George E. de Silva

- Gratien Fernando

- Henry Woodward Amarasuriya

- Herbert Sri Nissanka

- Leslie Goonewardene

- M. C. Siddi Lebbe [36]

- Madduma Bandara Ehelapola

- N. M. Perera

- Philip Gunawardena

- Susantha de Fonseka

- Thomas Amarasuriya

- Victor Corea

- Vivienne Goonewardene

- W. A. de Silva

- Walisinghe Harischandra

- Wilmot A. Perera

- Parama Weera Vibhushanaya

- Orders, decorations, and medals of Sri Lanka

- Utuwankande Sura Saradiel

Related Research Articles The United National Party , often abbreviated as UNP , is a centre-right political party in Sri Lanka. The UNP has served as the country's ruling party, or as part of its governing coalition, for 38 of the country's 74 years of independence, including the periods 1947–1956, 1965–1970, 1977–1994, 2001–2004 and 2015–2019. The party also controlled the executive presidency from its formation in 1978 until 1994.  Anagārika Dharmapāla was a Sri Lankan Buddhist revivalist and a writer. Don Stephen Senanayake was a Ceylonese statesman. He was the first Prime Minister of Ceylon having emerged as the leader of the Sri Lankan independence movement that led to the establishment of self-rule in Ceylon. He is considered as the "Father of the Nation". Matale is a major city in Central Province, Sri Lanka. It is the administrative capital and largest urbanised city of Matale District. Matale is also the second largest urbanised and populated city in Central Province. It is located at the heart of the Central Highlands of the island and lies in a broad, green fertile valley at an elevation of 364 m (1,194 ft) above sea level. Surrounding the city are the Knuckles Mountain Range, the foothills were called Wiltshire by the British. They have also called this place as Matelle. Great Rebellion of 1817–1818 , also known as the 1818 Uva–Wellassa Rebellion , was the third Kandyan War in the Uva and Wellassa provinces of the former Kingdom of Kandy, which is today the Uva province of Sri Lanka. The rebellion started against the British colonial government under Governor Robert Brownrigg, three years after the Kandyan Convention ceded Kingdom of Kandy to the British Crown.  The Sri Lankan independence movement was a peaceful political movement which was aimed at achieving independence and self-rule for the country of Sri Lanka, then British Ceylon, from the British Empire. The switch of powers was generally known as peaceful transfer of power from the British administration to Ceylon representatives, a phrase that implies considerable continuity with a colonial era that lasted 400 years. It was initiated around the turn of the 20th century and led mostly by the educated middle class. It succeeded when, on 4 February 1948, Ceylon was granted independence as the Dominion of Ceylon. Dominion status within the British Commonwealth was retained for the next 24 years until 22 May 1972 when it became a republic and was renamed the Republic of Sri Lanka.  Dr. Cristopher William Wijekoon Kannangara was a Sri Lankan Lawyer and a politician. He rose up the ranks of Sri Lanka's movement for independence in the early part of the 20th century. As a lawyer he defended the detainees that were imprisoned during the Riots of 1915, many of whom were the emerging leaders of the independence movement. In 1931, he became the President of Ceylon National Congress, the forerunner to the United National Party. Later, he became the first Minister of Education in the State Council of Ceylon, and was instrumental in introducing extensive reforms to the country's education system that opened up education to children from all levels of society. Weerahannadige Francisco Fernando alias Puran Appu is one of the notable personalities in Sri Lanka's history. He was born on 7 November 1812 in the coastal town of Moratuwa. He left Moratuwa at the age of 13 and stayed in Ratnapura with his uncle, who was the first Sinhalese proctor, and moved to the Uva province. In early 1847, he met and married Bandara Menike, the daughter of Gunnepana Arachchi in Kandy. He was captured by the British after the failure of Matale Rebellion along with Gongalegoda Banda and Ven. Kudapola Thera. He was executed by a firing squad on August 8, 1848. His body was buried in Matale.  Edward Walter Perera was a Ceylonese barrister, politician and freedom fighter. He was known as the "Lion of Kotte" and was a prominent figure in the Sri Lankan independence movement, served as an elected member of the Legislative Council of Ceylon and the State Council of Ceylon.  For other uses, see St. Thomas' College Sri Lanka The Welikada Prison is a maximum security prison and the largest prison in Sri Lanka. It was built in 1841 by the British colonial government under Governor Cameron. The prison covers an area of 48 acres (190,000 m 2 ). It is overcrowded with about 1700 detainees exceeding the actual number that could be accommodated. The prison also has a gallows and its own hospital. The prison is administered by the Department of Prisons. Sri Lankan independence activists are those who are considered to have played a major role in the Sri Lankan independence movement from British Colonial rule during the 20th century.  Charles Alwis Hewavitharana , FRCS, LRCP was a Ceylonese (Sinhalese) physician who played a significant role in Sri Lanka's Independence and Buddhist Revival movements. He was the brother of Anagarika Dharmapala. Arthur Vincent Dias , commonly known as Arthur V. Dias , was a philanthropist, temperance movement member and an independence activist of Sri Lanka. A planter by profession, he is known for the jackfruit propagation campaign he pioneered throughout the country, which earned him the name "Kos Mama". A national hero of Sri Lanka, Dias also helped a number of educational establishments in the country. Before Sri Lanka gained independence from British rule, he was imprisoned by the colonial government and sentenced to death, although he was later released.  Madduma Bandara Ehelapola , mostly known as Madduma Bandara, was one of the national heroes of Sri Lanka. Bandara and his family were executed in 1814 by the King for treachery. His bravery at the time of his execution made him a legendary child hero in Sri Lanka. The 1915 Sinhalese-Muslim riots was a widespread and prolonged ethnic riot in the island of Ceylon between Sinhalese Buddhists and the Ceylon Moors. The riots were eventually suppressed by the British colonial authorities.  Piyadasa Sirisena was a Ceylonese pioneer novelist, patriot, journalist, temperance worker and independence activist. He was the author of some of the bestselling Sinhalese novels in early 20th century. A follower of Anagarika Dharmapala, Siresena was the most popular novelist of the era and most of his novels were on nationalistic and patriotic themes. Piyadasa Sirisena used the novel as a medium through which to reform society and became one of the leaders in mass communication in the early part of the 20th century. Piyadasa Sirisena is widely considered as the father of Sinhalese novel. Some of his novel were reprinted even in the 21st century.  The Kandyan period covers the history of Sri Lanka from 1597–1815. After the fall of the Kingdom of Kotte, the Kandyan Kingdom was the last Independent monarchy of Sri Lanka. The Kingdom played a major role throughout the history of Sri Lanka. It was founded in 1476. The kingdom located in the central part of Sri Lanka managed to remain independent from both the Portuguese and Dutch rule who controlled coastal parts of Sri Lanka; however, it was colonised by the British in 1815. - ↑ Kennedy 2016 .

- ↑ Lakpura Travels 2015 .

- 1 2 "Recognising unsung heroes" . The Sunday Times . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "Keppetipola Disawe, proclaimed national hero, posthumously: To rest in honour, at last!" . Sunday Observer . 10 December 2016 . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev; agencies (9 December 2016). "From traitors to heroes: Sri Lanka pardons 19 who resisted British rule" . The Guardian . ISSN 0261-3077 . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "Nineteen leaders of the Great Rebellion of 1818 declared heroes" . Daily News . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "19 Sinhalese declared 'Traitors ' by British Raj, today declared 'Heroes' | Asian Tribune" . www.asiantribune.com . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- 1 2 "Recognition of Unsung Heroes" . www.dailymirror.lk . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ Options, B. T. (31 January 2016). "The long and winding road" . Explore Sri Lanka – Once discovered, you must explore..... . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ Mashal, Mujib (21 April 2019). "For Sri Lanka, a Long History of Violence" . The New York Times . ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "Language of the national anthem | Daily FT" . www.ft.lk . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- 1 2 "Ceylon Becomes the Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka" . The New York Times . 23 May 1972. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ Thaker, Aruna; Barton, Arlene (5 April 2012). Multicultural Handbook of Food, Nutrition and Dietetics . John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-35046-1 .

- ↑ Trawicky, Bernard (16 April 2009). Anniversaries and Holidays . American Library Association. ISBN 978-0-8389-1004-7 .

- ↑ Canada, Global Affairs (8 August 2014). "Cultural Information – Sri Lanka | Centre for Intercultural Learning" . GAC . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "Wanni Narratives – Part Two" . Sri Lanka Guardian . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "Sri Lanka turns 82 British-era 'traitors' national heroes" . Business Standard India . Press Trust of India. 1 March 2017 . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ Department of Government Printing 2017 .

- ↑ Kanakarathna 2017 .

- ↑ Department of Government Printing 2016 .

- ↑ Bandara 2019 .

- ↑ Wright, Arnold (1999). Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources . Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1335-5 .

- ↑ "The era of rebellion 1815-1848" . www.dailymirror.lk . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ Wijesiriwardana, Panini; Silva, Nilwala de. "A look at rural life in British Ceylon" . www.wsws.org . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "The Island" . www.island.lk . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "Sri Lanka's fight for Independence" . Sri Lanka News – Newsfirst . 4 February 2017 . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ Llc, Books (September 2010). Sri Lanka Independence Struggle: Sri Lankan Independence Movement, Anagarika Dharmapala, Cocos Islands Mutiny, Matale Rebellion . General Books LLC. ISBN 978-1-157-67087-2 .

- ↑ Alagappa, Muthiah (2004). Civil Society and Political Change in Asia: Expanding and Contracting Democratic Space . Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5097-4 . The island gained independence in 1948 in perhaps the most orderly transfer of power in the post - World War II era.

- ↑ Grant, Patrick (5 January 2009). Buddhism and Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka . SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-9367-0 .

- ↑ "Journey since Independence 1948 - 1955 - HOME" . www.treasury.gov.lk . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ "Sri Lanka – Countries – Office of the Historian" . history.state.gov . Retrieved 26 July 2020 .

- ↑ de Silva, K. M. (1972). "Srilanka (Ceylon) the New Republican Constitution" . Verfassung und Recht in Übersee / Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America . 5 (3): 239–249. doi : 10.5771/0506-7286-1972-3-239 . ISSN 0506-7286 . JSTOR 43108222 .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Sunday Times 2011 .

- ↑ M. P. M. Saheed. "Siddi Lebbe: The sage leader of the Muslim community" . Sunday Observer.

- Bandara, Kelum (6 March 2019). "Ban lifted on 'Angampora': Wellessa heroes honoured" . www.dailymirror.lk . Daily Mirror . Retrieved 7 March 2019 .

- Kanakarathna, Thilanka (11 September 2017). "81 leaders in 1818 freedom struggle declared as national heroes" . www.dailymirror.lk . Daily Mirror . Retrieved 7 March 2019 .

- Kennedy, Maev (9 December 2016). "From traitors to heroes: Sri Lanka pardons 19 who resisted British rule" . The Guardian . Retrieved 7 March 2019 .

- Somasundaram, Daya (2010). "Collective trauma in the Vanni- a qualitative inquiry into the mental health of the internally displaced due to the civil war in Sri Lanka" . International Journal of Mental Health Systems . University of Jaffna. 4 : 4. doi : 10.1186/1752-4458-4-22 . PMC 2923106 . PMID 20667090 . S2CID 40442344 .

- "Sri Lanka National / Independence Day" . Lakpura LLC . Lakpura Travels. 15 May 2015.

- "Proclamation By His Excellency The President" (PDF) . The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka . Sri Lanka: Department of Government Printing. 1998/25 (Extraordinary). 21 December 2016.

- "Proclamation By His Excellency The President" (PDF) . The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka . Sri Lanka: Department of Government Printing. 2036/11 (Extraordinary). 11 September 2017.

- "Sri Lanka's Independence movement" . www.sundaytimes.lk . Sunday Times. 30 January 2011.

- National Heroes

- Justice of the peace

- Prizes, medals, and awards

- Military awards and decorations

All that You Need to Know about the Sri Lanka Independence Day History! The graceful history woven around the splendid island of Sri Lanka is just simply wonderful. Starting from the civilization of Naga-Yakka tribe, with the arrival of Prince Vijaya and his 700 followers, passing a series of successive ancient kingdoms, the journey Sri Lanka came was full of delight, and excitement. However, next, Sri Lanka passed a period of colonization . Of course, it is this period that paved the path for the Sri Lanka independence movement. Thus, it is something that can never be missed. Specially, when studying about the history of Sri Lanka , as well as about the Sri Lankan independence day history. Hence, we thought of sharing with you the story behind these incidents, helping you have a good overview on the olden days of this charming isle. So, why not? Let us start getting to know about this epoch of the Sri Lankan saga. For a better understanding, let us start with the British colonial period. Who ruled Sri Lanka Before Independence? If you have an idea about the colonization history timeline of Sri Lanka, you might know that Sri Lanka was first colonized by Portuguese. Next, Sri Lanka was under Dutch rule. Finally British colonized Sri Lanka, in 1815. Of course, Sri Lankans were happy with the British rule. They proceeded ahead with their day to day lives at first. Yet, with time, Sri Lankans hated the British rule. They needed Sri Lanka to regain freedom, and to have a self-rule. Thus, the struggles against colonial power began. Many struggles came up, and all of them had an important role when considering the Sri Lanka independence day history. Some of them are as follows. Uva RebellionMatale rebel. Below sections highlight those most significant incidents that took place with regard in detail. Accordingly, in 1817, the Uva rebellion took place. There were two closest incidents that led to this uprising. One was the obstacles Sri Lankans faced when enjoying the traditional privileges. The other was the appointment of a Moor loyal to British as an official. Keppetipola Disawe launched the rebellion. Moreover, several chiefs joined and supported the rebel. However, the rebel could not achieve the expected success, owing to poor leadership, and several other reasons. And then in 1848, the Matale rebel came up. Hennedige Francisco Fernando (Puran Appu) and Gongalegoda Banda led it. The Sinhalese army left from Dambulla to capture Kandy from the British. They attacked the British buildings, and destroyed tax records as well. However, British troops took Puran Appu as a prisoner, and they executed him. Yet, Gongalegoda Banda and his younger brother escaped. Later, British issued a warrant to arrest Gongalegoda Banda. Moreover, they declared a reward for any who provided information about him. However, Malay soldiers were able to arrest Gongalegoda Banda, and the British kept him as a prisoner in Kandy. The Buddhist Resurgence in Sri LankaFrom ancient times, Buddhism remained the main religion in Sri Lanka. Of course, there were instances where Hinduism flourished in this island owing to the South Indian invasions. Moreover, Islamism emerged from some parts of the island due to the foreign traders who arrived in Sri Lanka. Yet, the majority of the great monarchs were Buddhists. Thus, their main contributions were towards flourishing Buddhism in the island. However, with the colonizations, Catholicism, and Christianity came up. The British worked hard with regard. Moreover, they attempted to provide Protestant Christian education to the younger generations of the country. Yet, the efforts could not reach a success as per their expectation. That was because of the Buddhist resurgence that took place during this period. Several eminent personalities aided this Buddhist resurgence. Further, foreigners such as Col. Henry Steel Olcott were among them as well. Owing to their activities, Buddhism flourished on this island again. Also a group of Buddhist institutions came up with their sponsorship. In the course, Sinhala Buddhist revivalists such as Anagarika Dharmapala emerged influencing the society. Many individuals were with him. Hence, it was more like the emergence of a group of people striving towards a similar cause. However, Anagarika Dharmapala, together with his community, could create a Sinhala-Buddhist consciousness. 1915 Sinhala Muslum RiotsIn 1915, an ethnic riot arose in the city of Colombo. It was against Muslims. Moreover, Buddhists, as well as Christians took part in it. Besides, British understood that this riot could later turn out to be against them as well. Hence, they heavy-handedly reacted to this riot. As a result, Dharmapala broke his leg. His brother passed away there. Also, the British government arrested several hundreds of Sinhalese Buddhists for supporting this riot as well. Among the imprisoned were several future leaders of the independence movement. Some of them highlighting characters among them were F.R. Senanayake, D. S. Senanayake, Anagarika Dharmapala, Baron Jayatilaka, Edwin Wijeyeratne, A. E. Goonesinghe, John Silva, Piyadasa Sirisena, etc. Their imprisonment was indeed a great loss for the continuation of the struggles. Yet, nothing could hold back the Sri Lankan motive. Sir James Peiris, with the support of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, and E.W. Perera, submitted a secret memorandum to the Secretary of States for Colonies. It was a plea to repeal the martial law. Also, it described the cruelty of the Police, led by the British, Dowbiggin. However, these attempts succeeded, as the British government ordered the release of the imprisoned leaders. Further, several British officers were replaced as well. Founding the Ceylon National CongressIn December, 1919, a nationalist political party was founded. Yes, you guessed it right! It was named Ceylon National Congress (CNC) . This group was a combination of the members from the Ceylon National Association and the Ceylon Reform League. However, the Ceylon National Congress played a vital role in Sri Lanka’s journey of attaining independence. The founding president of the CNC Party was Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam. Later, eminent personalities such as Sir James Peiris, D. B. Jayatilaka, E. W. Perera, C. W. W. Kannangara, Patrick de Silva Kularatne, H. W. Amarasuriya, W. A. de Silva, George E. de Silva and Edwin Wijeyeratneled the party. However, it was this CNC party that paved the path for the formation of the United National Party as well. Sri Lanka Independence Movements and the Youth LeaguesThe youth of the country were highly interested and involved in the Sri Lanka independence movement. Moreover, their utmost motive was not only achieving freedom, but also seeking justice for the citizens of the country. It is no secret that it was Dharmapala’s ethnic group that paved the way for the youth to take part in the independence movement. However, it was the Tamil Youth of Jaffna, that gave the head start for the youth leagues. Accordingly, they formed Jaffna Students. It was later popular as the Jaffna Youth Congress (JYC). They argued that the Donoughmore reforms did not concede sufficient self-governance. Thus, they successfully led a boycott of the first state council elections that took place in Jaffna, in 1931. Meanwhile, more youth leagues came up from South Sri Lanka. Intellectuals who returned from Britain, after completing their education in foreign states, supported these leagues. However, the ministers of the CNC demanded more power from the colonial government. They even petitioned the government in order to get their demands. Yet, they never demanded for independence, or at least the dominion statues. Nevertheless, owing to their demands, as well as due to a severe campaign of the Youth leagues, the CNC ministers had to withdraw their ‘Ministers’ memorandum’. Nevertheless, the youth leagues that came up during that period actively took part in several activities. And of course yes! All those activities had some kind of an influence in the journey of the Sri Lanka Independence movement. Thus, we thought of having a quick glance over those highlights as well. Some of them are as follows. Formation of Lanka Sama Samaja PartyOf course, they were some interesting movements. They had a uniqueness of their own. Continue reading, to get to know what they are! Suriya-Mal MovementAs the British rule continued, a poppy sale was carried out in Sri Lanka. It was with relation to the Armistice Day, which was on 11th November. Moreover, it was a project to support the British ex-servicemen to the detriment of Sri Lankan ex-servicemen. However, Aelian Perera, who could not tolerate this activity, started a rival sale of Suriya flowers (flowers of the Portia tree) focusing on the same day. It was with the aim of aiding the needy Ceylon ex-servicemen. Later, the South Colombo Youth League joined hands with this movement and revived it. British authorities tried to interrupt this effort of the youth. Yet, they failed. Thereafter, until the second world war, groups of youth sold Suriya flowers, in competition with the poppy sellers. Indeed, this is one of the most significant milestones with regard to the involvement of youth leagues in the Sri Lanka independence movement. The Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), also known as the Marxist Lanka Sama Samaja Party was the first party that had the sole motive of demanding independence. And the speciality is that it grew out of the youth. Moreover, their aims were specific, since what they aimed at was complete national independence. Also, re-gaining nationalism in terms of production, distribution, as well as exchange was associated with their objectives. Moreover, they also worked hard to abolish the ethnic inequality, caste inequality, and gender inequality as well. Going beyond, they also demanded that colonial authorities replace the official language by Sinhala and Tamil. Yet, the demanded replacement did not take place, and English continued to be the official languages until 1956. Still, their efforts were impressive. They could strengthen the Sri Lanka Independence day movement. The Sri Lankan Society By ThenOwing to the Colebrook reforms, a number of opportunities and income paths emerged. Thus, the castes and status of the traditional Sri Lankan society diminished. Instead, a new middle-class was formed within the society. Most of them were businessmen, and they were educated. Among them were even individuals who completed their education in foreign countries. Thus, they had a good exposure, and they had a good overview on the political status of the country. All these things made this new middle-class get involved and lead the political campaigns of Sri Lanka. Hence, their involvement can be seen significant when considering the Sri Lanka independence day history. Solbury Reforms and the Sri Lanka IndependenceHowever, the British government appointed the Soulbury Commission. Their task was to study and make recommendations for Sri Lanka constitutional reforms. The members of the commission arrived in Sri Lanka in December, 1944. The report of the commission came out in September, 1945. Accordingly, the commission had recommended a constitution that offers Sri Lankans the full power of the internal activities of the country. Schedules were made for the first parliament election under the Solbury reforms. Yet, the British authorities declared nothing with regard to the grant of independence for Sri Lanka. Meanwhile, Sri Lankan political leaders such as D. S. Senanayake argued detailing the rights that Sri Lankans have for independence. However, after much effort, and struggles, just two months before the scheduled parliament election, British authorities declared that they would grant Sri Lanka the freedom to enjoy the facilities of an independent country. Then, in August 1947, the first parliamentary election took place. As per the results, having won the majority of the seats, the United Nationals Party with the leadership of D.S. Senanayake could establish the government. Yet, the British rule still had power in terms of foreign affairs, and military. The reason behind this was the significant geographical location of Sri Lanka, which was highly beneficial in terms of foreign affairs and military activities. Nevertheless, D.S. Senanayake could recognize the wishes of the British authorities. Hence, he took actions to sign treaties with them. Time passed by, and later, the British government approved the Ceylon Freedom Act. Accordingly, the British government lost the power to interfere with the activities related to governing Sri Lanka from 4th February, 1948 . Of course, with that, Sri Lanka attained Independence, and it happened to be the independence day of Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka Independence Day CelebrationHowever, it was on 10th February, 1948 that the first parliament of the independent Sri Lanka assembled. On that day, D.S.Senanayake took down the British flag, hoisted the Sri Lankan national flag, and symbolized the establishment of Sri Lankan rule. Yet, from 1948 onward, Sri Lanka celebrated independence day on 4th February each year, commemorating the national heroes, and the efforts behind this achievement. The official independence day celebration takes place having the president as the chief guest. The president hoists the national flag, and addresses the country. Parades, and cultural performances also take place as a part of this official celebration annually. Meanwhile, Sri Lankans all around the island, hoist the national flag on this day, and join the celebration. The Bottom Line | Sri Lanka Independence Day HistoryLikewise, when considering the Sri Lanka independence day history, it is clear that the journey of achieving independence had not been that much easy. It was a collective effort of several hundreds. Moreover, it was the strength of the unity of Sinhalese. However, even after achieving independence on 4th February, 1948 Sri Lanka was under dominion state. It was only on 22nd May, 1972 that Sri Lanka achieved the status of a republic. It was after that Sri Lanka was called the ‘republic of Sri Lanka’. Besides, more than 70 years have passed after Sri Lanka gained independence. Sri Lanka passed several milestones after independence day as well. If you are willing to get to know about them as well, do not forget to check our article on, ‘ Significant milestones of Sri Lanka after independence ’. You may be excited for a tranquil beach vacation along a gorgeous stretch of golden sand. If not, you might be thrilled to experience the exhilaration and thrill of the incredible wildlife among the breathtaking scenery. Going further, you can even be anticipating learning about the splendor of the historical tales entwined with the island's customs. Similarly, your dream could be anywhere in these boundaries or outside of them. Nevertheless, we cherish your dream and pledge to turn it into a reality. Indeed, the Customized Tour Packages we provide serve as evidence that we honor our commitments. Lead Traveler - Pingback: Frequently Asked Questions about Sri Lanka - Next Travel Sri Lanka

- Pingback: Jaffna in Sri Lanka - Number of places to visit|past and present

- Pingback: History of Sri Lankan Education System - Next Travel Sri Lanka

- Pingback: D.S.Senanayake, a Sri Lankan Leader | Biography

- Pingback: All About Sports in Sri Lanka and their Future | Travel Destination Sri Lanka

- Pingback: Important Days in Sri Lanka - 2023 | Travel Destination Sri Lanka

- Pingback: Best Walks in Colombo | Travel Destination Sri Lanka

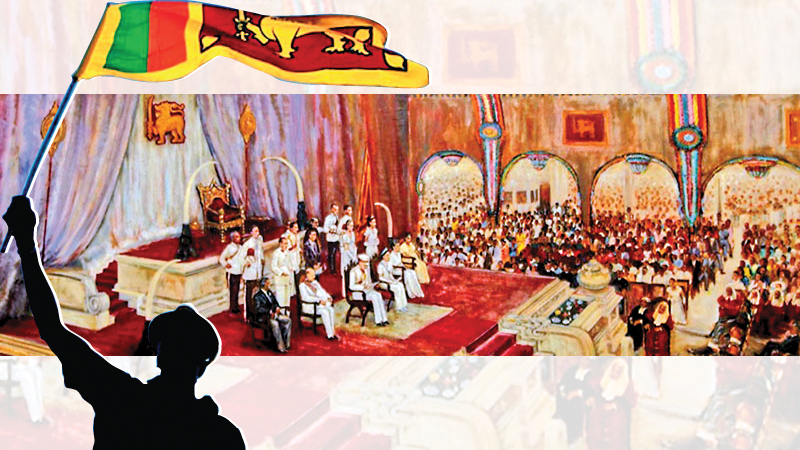

Leave a Reply Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked * Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed . Continue reading...  Henarathgoda Botanical Garden, the Amazing Land of Charm!Looking for a magical destination that will forget your daily rigours? Take it easy, simply because the splendid island of Sri Lanka offers you the…  Colombo, the Wonderful Sleepless Capital in the Paradise of Sri Lanka!The pearl of the Indian Ocean or Sri Lanka, the wonderful tiny island in South Asia is a popular tourist hotspot worldwide for countless reasons…. Privacy Overview Facets of Sri Lanka’s history and Independence Sri Lankans across the island still live freely and independently because of the lionhearted fighters for freedom Mother Lanka gave birth to more than seven decades ago. The National Day or Independence Day which falls on February 4 annually, is a day when every Sri Lankan commemorates the country’s independence from British rule in 1948. Independence Day is celebrated through flag-hoisting ceremonies, parades, cultural and other performances which showcase the cultural traditions strengths and wealth of Sri Lanka. The Independence Ceremony  D.S. Senanayake Normally, this event takes place in Colombo where the President hoists the National Flag and addresses the nation. In the President’s speech, he highlights the achievements of the Government during the past year, raises important issues and calls for further development of the country. The President also pays tribute to the national heroes of Sri Lanka and observes two minutes’ silence in their memory. Military parades A military parade is also held. The military parades showcase the power of the Army, Navy, Air Force, Police and the Civil Defence Force. The commitment, bravery, national unity, and determination to achieve peace are aroused in the minds of the people, who also thank patriots who fought and laid down their lives for the country. The Portuguese arrive After the arrival of the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in India, the Portuguese learnt that Ceylon as Sri Lanka was then known, produced good quality cinnamon. During that time spices like cinnamon had a big demand in the European market. A Portuguese Naval officer, Lourenço de Almeida and others who were on a mission to capture Muslim merchant ships got caught in a storm and unexpectedly landed in Ceylon in the year 1505. At first, they said that they were here for trading. However, they later interfered in politics. The Portuguese era Sri Lanka did not become a colony of Portugal until King Dharmapala of Kotte handed over the region of Kotte to the Portuguese as a deed of gift in 1580. The rule of the Portuguese started to much aversion by the people of Kotte. The Kings of Kandy led the nation into many battles to set free the Kingdom of Kotte from the Portuguese with little success and later the Kings of Kandy had to seek help from the Dutch. The Dutch arrival  In 1658, the Dutch took control of the maritime provinces from the Portuguese. The Dutch were used by the Sinhalese king to counter the Portuguese who wanted to expand their rule. The coming of the Dutch led to the Portuguese having two enemies to deal with. The Portuguese were forced to sign a treaty with the Dutch and come to an agreement with their enemies. Finally, the Portuguese left Ceylon. Even after the Portuguese period ended a part of their culture remained in Sri Lanka. Battles by the Dutch During the years 1659–1668, the Dutch attacked the kingdom of Kandy but the Kings of Kandy managed to win almost every battle and the Dutch had to retreat. By the year 1762 the dissents between the ruler of Kandy and the Dutch started increasing even more. As a result, the ruler of Kandy had to seek help from the British. The British arrive In 1796, the British arrived and took control of the maritime provinces from The Dutch. Different elements of Dutch culture are now integrated into Sri Lanka’s culture. The islands of the Palk Strait were renamed during Dutch rule in the Dutch language. Among them were Kayts and Delft. There is a part of the Sri Lankan population with Dutch surnames, often people of mixed Dutch and Sri Lankan heritage, who are known as Burghers within the community. The British take over The British period is the history of Sri Lanka between 1815 and 1948. During this era the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom into the hands of the British Empire took place. It ended over 2,300 years of the Sinhalese monarchy on the island. The British rule in the island lasted until 1948 when the country gained Independence following the Independence Movement’s fight for freedom. Although the British monarch was the Head of State, in practice, his or her functions were exercised in the colony by the colonial Governor, who acted on the instructions from the British Government. The British found that the hill country of Sri Lanka was suited to grow coffee, tea and rubber. By the mid-19th century, Ceylon Tea had become a key feature of the British market. The first rebellion against the British took place in 1818 but was not successful. The leaders of this rebellion were Keppetipola Disawa, Kiwlegedara Mohottala, Madugalle Disawe and Butawe Rate Rala. Then again, there was a second rebellion in 1848, this time led by Veera Puran Appu, Gongalegoda Banda and Dingirala. But this rebellion too did not achieve its main goal, freedom from British rule. The Independence Movement  The transfer of power was generally known as a peaceful transfer of power from the British administration to Ceylonese (Sri Lankan) representatives. The Independence Movement was initiated around the turn of the 20th century and was led mostly by the educated middle class. Independence It succeeded when on February 4, 1948 Ceylon was granted independence as the Dominion of Ceylon. Dominion status within the British Commonwealth was retained for the next 24 years until May 22, 1972 when it became a republic and was renamed as the Republic of Sri Lanka. The personalities who led the nation to independence are honoured as National Heroes. The first Prime Minister Don Stephen Senanayake (D.S. Senanayake) (1884 – 1952) was an independence activist who served as the first Prime Minister of Ceylon from 1947 to 1952. He played a major role in the Independence Movement, first supporting his brother F.R. Senanayake. After his brother died in 1926, D.S. took his place in the Legislative Council and led the Independence Movement to success. His most distinguished contribution to the nation was his agricultural policy. He is known as the ‘Father of the Nation.’ Pavanya Samaranayake Grade 9-A Musaeus College Colombo 07 Ceylinco Life achieves a decade as World Finance’s ‘Best Life Insurer in Sri Lanka’Teejay records a positive q3, you may also like, kindness beyond words, shilper institute, makola annual prize-giving 2024, is watching tv good or bad, leave a comment cancel reply. Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.  The Sunday Observer is the oldest and most circulated weekly English-language newspaper in Sri Lanka since 1928 [email protected] Call Us : (+94) 112 429 361 - Youth Observer

- Junior Observer

- Marriage Proposal

- Classifieds

- ObserverJobs

- Schoolboy Cricketer

- Government Gazette

- தினகரன் வாரமஞ்சரி

Facebook PageAll Right Reserved. Designed and Developed by Lakehouse IT Division  - Book Reviews

- Pictorial Images

- Sinhala Mind-Set

- Speeding Up Links: Mirigama-Kurunegala Expressway Soon Operational

- Why Thuppahi

- Young Tourism Ambassadors in Jaffna

Remembering DS Senanayake on Sri Lanka’s Independence DaySenanayake Foundation, I tem in Daily Mirror, 4 Feb 2022  The first Prime Minister of Sri Lanka (Ceylon) D.S. Senanayake entered the National Legislature in 1924. He was relatively unknown in the country and was pushed into prominence by his elder brother F.R. Senanayake, who was a very popular and active figure in the social and political arena. Many were surprised and taken aback to see D.S. entering the political field, as they were expecting his brother F.R. to fit the role. Perhaps the only person who had faith in D.S’s capability at that time was none other but F.R. Senanayake himse lf. Ceylon (Sri Lanka) as it was then known was under foreign domination from 1505 to 1948. Three Colonial Powers namely the Portuguese, Dutch and the British ruled parts of the island till 1815 when the entire country was subjugated to the British Government. Many a battle fought by our heroes at different times to free the country remained unsuccessful and the freedom struggles thus brutally subjugated became dormant until its last phase was initiated by F.R. Senanayake in 1915, after being released from imprisonment on false accusations. The Colonial Government imprisoned F.R. Senanayake along with his brother D.S. and a host of other Sinhala Buddhist leaders of the Temperance Movement on trumped-up charges. However, they had to be released as they could not find a shred of evidence against them. But the massacre of innocents under Martial Law continued unabated and F.R. Senanayake vowed to free the country from colonial bondage. He set about revitalizing the freedom movement that lay dormant for many years.  He became a dominant member of the Ceylon National Congress. Continuous agitation for reforms by the newly created Congress resulted in elections being held on a limited scale for the National Legislature in 1924 and F.R. supported his brother D.S. Senanayake to become an elected member of the Legislature. However, just two years later, in 1926, F.R. met with an untimely death at a relatively young age of 44. He was D.S.’s mentor and his death was not only an enormous blow to D.S. Senanayake but also a severe setback to the freedom movement. In fact, many thought that it was the end of the freedom struggle. But D.S. kept his brother’s dream alive and carefully planned and plotted the path to freedom. On 4th February 1948, twenty-four years after entering the National Legislature, D.S. Senanayake raised Lanka’s flag that was brought down by the British in 1815 and proclaimed to the world, Lanka’s Independence. “Sir, when The Donoughmore Report was accepted I was one of those who were rather apprehensive of the success of the Committee system. At that time, I was not certain how the Constitution would work and what difficulties we would have to contend with. But since I have been in charge of a Committee for about a year I must say that my faith in the Committee system has increased considerably” Freedom was achieved by many nations all over the world by pursuing either a path of non-violence or by the barrel of the gun. Polemics of revolt have shown us the methodologies advocated by Gandhi to Guevara, from the apostle of peace to the votary of violence. D.S. Senanayake, however, followed another way, the way of effective negotiations. It may have him taken twenty-four years to achieve this goal but he did so by periodically advancing towards freedom without spilling one drop of blood to achieve independence. Perhaps it was this peaceful transition that had created a misconception in the minds of some that freedom for Sri Lanka was gifted when India was granted her freedom. India and Sri Lanka had their independent freedom struggles. While Indian leaders were seeking freedom through passive resistance, Sri Lankan leaders were represented in the Legislature following a path of active negotiations. It was the capabilities shown by our leaders in the administrative affairs of the country that prompted the then Governor Sir Hugh Clifford to recommend to the British Government in 1926, that the existing Constitution should be viewed as transitional and that a more representative Constitution should be installed. On this recommendation, the British Government appointed the Donoughmore Commission in 1927 to bring about reforms. India received a similar commission, namely the Simon Commission in 1928. India, however, totally rejected the Simon Commission. They took up the position that the Simon Commission had no right to bring a constitution to India. Demanding Swaraj (independence outside the Commonwealth), non-corporation was unleashed by the Indian leaders throughout the streets of India. Sri Lankan leaders did not resort to the same manner. Though they did not accept the recommendations of the Donoughmore Commission in Toto, it was not rejected. The recommendations were taken up in the National Legislature, amended through debate and discussion, and the amended version was accepted as a step towards achieving self-government. In 1931, Sri Lanka became the first country in the whole of Asia to adopt universal suffrage with women being given the same voting rights as men; a feature that even some advanced European countries did not possess. Though the Donoughmore Constitution did not measure up to the requirements of the elected representatives who were expecting a Westminster system of government, they were quite pleased with Adult Franchise and abolition of Communal Representation which were viewed as an obstruction to unification. The other main feature, Executive Committee System was received with mixed feelings. Deeply suspicious, D.S. Senanayake was very critical of the proposed Committee system. Having been involved in the functioning of existing committees, the unwanted delays experienced made him to view them as a hindrance rather than an asset to development. However, the amended form was accepted by him on the firm understanding that reforms were to follow. Bitterly divided, the amended Donoughmore Constitution was accepted by only a slender majority. Leaders such as Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, E.W. Perera and C.W.W. Kannagara opposed the proposals while Sir D.B. Jayatilaka, D.S. Senanayake and W.A. De Silva supported the proposals. It was well known that it was D.S. Senanayake who used his influence to win over the majority for the proposals. He was of the view that though the proposed reforms did not measure up to what was expected, the proposals were a halfway measure to self-government and that it should be given a trial period. The Donoughmore Constitution gave birth to the State Council in 1931 and for the first time elected Representatives entered the realm of the executive. In the election process of the seven Executive Committees announced, chairmen of each committee were designated as Ministers, they were,  It is well known that no member of the Board of Ministers utilized Committees as much as D.S. Senanayake. Having realized that the mere possession of Executive power was meaningless unless it was utilized for the betterment of the masses, he used his Committee to restore all ancient tanks and embarked on massive irrigation schemes to provide water to the rural masses. He opened up the neglected Dry zone which was once the granary of ancient Lanka and settled the landless villages in vast colonization schemes making them a great asset to the nation. Speaking on the Committee system in the State Council on 19th July 1932, D.S. Senanayake said, “Sir, when The Donoughmore Report was accepted I was one of those who were rather apprehensive of the success of the Committee system. At that time, I was not certain how the Constitution would work and what difficulties we would have to contend with. But since I have been in charge of a Committee for about a year I must say that my faith in the Committee system has increased considerably.”  “I feel it is a mistake, a great mistake, to make an attempt to separate the people communally, and make a Constitution whereby the people will forever remain separated communally. If we want to progress, let us all unite. If we try to pander to the feelings of a section of the people, all that will happen is that we will be dividing the people, and that is the greatest danger that can befall any country” Though many an achievement was made under the Donoughmore Constitution which was in operation for sixteen years, it did not always bring about smooth administration. There were many clashes between the elected Representatives and the Colonial bureaucrats; as such there was continuous agitation for reforms by both the State Council and the Ceylon National Congress. As a result, in May 1943, the Colonial government made a declaration authorizing the Board of Ministers to draft a Constitution within certain parameters and stipulated that the proposed Constitution should be ratified by at least seventy-five percent of the State Council. The Ministers welcomed this offer and proceeded to draft a Constitution with the aim of obtaining ‘Dominion Status’, the surest way for attaining independence. The task was completed in four months, and the draft was submitted to the Governor to be presented to the Secretary of State for approval. However, what they received was a rude shock. On 5th July 1944, the House of Commons made an announcement that a Commission will be appointed to: ‘To visit Ceylon in order to examine and discuss any proposals for constitutional reforms in the Island which have the object of giving effect to the Declaration of His Majesty’s Government on that subject dated 26th May 1943, and after consultation with various interests in the Island, including minority communities, concerned with the subjects of constitutional reforms, to advise His Majesty’s Government on all measures necessary to attain that object.’ This was a sinister deviation from the original Declaration and a gross breach of trust. Sir John Kotelawala in his autobiography “An Asian Prime Minister’s Story” refers to this incident. He states, “Sir Ivor Jennings, the great authority on Constitutional questions, has expressed the view that the terms of reference of the Soulbury Commission, appointed in 1944, were undoubtedly a breach of an understanding given by the British Government in May 1943. ‘What is worse,’ says Sir Ivor, ‘was the manner in which this breach was brought about. It left a very nasty taste in one’s mouth.’ When it was all over, Colonel Oliver Stanley, Secretary of State for Colonies, remarked with typical English understatement that this affair had been badly handled.” Many Members of the State Council and of the Ceylon National Congress were aghast at this decision. They began to doubt the sincerity of the British Government. D.S. Senanayake, though disappointed and critical of what had happened, realized that sabotage had emanated from within and not from outside. Referring to this in the State Council on 23rd November 1944, he said, “As the hon. Members are aware, we received a Declaration to which we gave our interpretation, and on that interpretation, we grafted a constitution. We then decided – at least I had stated our decision was – that we should submit that Constitution to the Secretary of State first and that if it was considered acceptable to him we should bring it here for the approval of a 75 per cent majority of Members of this house ….. You see, Sir, when we drafted that Constitution we sent it to the Secretary of State and I believe, up to this day there was no conditions stipulated that a Commission should come out to examine the views of the interests that were here. If that was so, there was no need for them to tell us that it should get the approval of a 75 per cent majority in this House. I believe, and I honestly believe, that the reasons for sending a Commission here to consider various interests is due to the fact that the draft Constitution which was submitted by the Board of Ministers and which met with the requirements of the Secretary of State laid down in his Declaration is not the kind of Constitution that those who had influence with the Secretary of State expected us to bring out. So they felt that it was time to sabotage it.” He went on to say, “… I feel it is a mistake, a great mistake, to make an attempt to separate the people communally, and make a Constitution whereby the people will forever remain separated communally. If we want to progress, let us all unite. If we try to pander to the feelings of a section of the people, all that will happen is that we will be dividing the people, and that is the greatest danger that can befall any country. It is because of that danger that I do not want communal representation; it is not that I object to two seats here or two seats there. As long as there is this feeling that each community should be separated politically, that there should be this cleavage between community and community, those ideas will penetrate into our whole social life, our whole economic life, into all our activities in this country.  DS and OEG in London in 1946(?) to press for independence Dismissing the minority phobia, DS said, “When I suggested the procedure we adopted first, namely, that we deal with the Secretary of State and then the Council, I can honestly tell you that in my own mind I had no desire for Sinhalese domination, or Tamil domination, or European domination; my whole desire was for Ceylonese domination, and the freedom I wanted was for the people of Ceylon.” There was huge agitation to boycott the Soulbury Commission that arrived on the island on 22nd December 1945. D.S. Senanayake, however, did not identify himself with such clamour. He was of the view that the Soulbury Commission should be won over to their way of thinking, and though the Ministers never gave evidence officially, they had many discussions with the Commissioners. D.S. Senanayake in particular had numerous discussions with the Commissioners and even accompanied them on their visits to all parts of the Island. Lord Soulbury was greatly impressed by D.S. Senanayake took an instant liking to him. Lord Soulbury’s attitude and D.S. Senanayake’s commitment helped to rectify the stained relationship between the Imperial Government and the Board of Ministers, and most importantly it paved the way for D.S. Senanayake to obtain the approval for the Constitution that he was eagerly waiting for. The Soulbury Report was published in September 1945, and a White Paper on the intentions of His Majesty’s Government was published on 31st October 1945. Though D.S. Senanayake’s recommendations were included and further advancement had been made, the granting of Dominion Status was postponed. It is believed that the defeat of the Conservative Government in 1945 and the Labour Party assuming office caused this change as the new Secretary of State George Hall, who replaced Colonel Oliver Stanley, was not so amiable to the granting of Dominion Status. Had there been no change of government, Colonel Stanley would have remained as the Secretary of State and Sri Lanka on track to receive Dominion Status in 1945. Anyhow it was conceded that the New Constitution if adopted by the State Council, the Imperial Government would pave the way for the attainment of Dominion Status within a short space of time. On this understanding, on 8th November 1945, D.S. Senanayake moved the following motion in the State Council. “This House expresses disappointment that His Majesty’s Government has deferred the admission of Ceylon to full Dominion status, but in view of the assurance contained in the White Paper of October 31, 1945, that His Majesty’s Government will co-operate with the people of Ceylon so that such status may be attained by this country in a comparatively short time, this House resolves that the Constitution offered in the said White Paper “’be accepted during the interim period.” Addressing the State Council on 8th November 1945, D.S. Senanayake went on to say, “I was invited to London by Colonel Stanley, but my negotiations were conducted with the new Secretary of State, Mr Hall. I should like at the outset to bear witness to the encouragement which I received from both of them. It has been a weakness in our case that we have had to correspond by telegram. They have not known the depth of our feelings; we have been suspicious of their intentions. Colonel Stanley was Colonial Secretary for most of the war. He was aware of the importance of our co-operation in the war effort; he was anxious to secure our political advancement; in him, I am convinced, we have a true friend. Mr Hall – who is, if I may say so, a miner like myself – came fresh to the problems of Ceylon. It was inevitable that he, and the Government of which he was a member, should require time for the consideration of our problems. That he and they approached with sympathy is proved by the result. For the Declaration which I ask you to accept is better than the Declaration of 1943, better than the Minister’s draft and better than the Soulbury Report.” In his lengthy speech, he touched upon all aspects from the freedom movement, its origin, obstacles encountered, sabotage experienced and finally the achievement of the moment of freedom. Allaying the fears of the Minority, he said, “The road to freedom was by no means straight. That we were correct in our procedure is proved by paragraph 12 of the White Paper, and I am glad that His Majesty’s Government has had the generosity to admit that we were right. We did all that we were asked to do and with a speed which, I think, surprised Whitehall. The procedure was changed not by us but by His Majesty’s Government, and the change was due solely to the representations of the minorities. After those representations, His Majesty’s Government felt the whole question should be examined by a Commission. We protested as we were bound to do, at what we regarded as a breach of an undertaking. I am convinced, after hearing the case put in London, that the charge was due to an excess of caution. It was felt that the minorities should be given every opportunity of proving their case if they could. They were given every opportunity, and they took it. The Ministers allowed their draft to speak for itself. If the Commissioners wanted to see anything, we showed it to them, but we gave no evidence. The fact that we gave no evidence has had two excellent results. “First, the minorities said what they pleased and how they pleased. The Ministers were relieved of the temptation to retaliate. In this way we were, I hope, able to avoid adding to the bitterness and ill-will that we so correctly prophesied in 1941. If anybody ought to feel aggrieved it was those who were so bitterly attacked, but we do not feel aggrieved because the verdict has been in our favour. Secondly, that verdict is more impressive because we left our proposals to speak for themselves. “No reasonable person can now doubt the honesty of our intentions. We devised a scheme which gave heavy weightage to the minorities; we deliberately protected them against discriminatory legislation; we vested important powers in the Governor-General because we thought that the minorities would regard him as impartial; we decided upon an independent Public Service Commission so as to give an assurance that there should be no communalism in the Public Service. All these have been accepted by the Soulbury Commission and quoted by them as devices to protect the minorities. Commending the White Paper, he said, “The great advantage of the White Paper is that it gives us complete self-government and puts an end to Commissions. If hon. Members who study the White Paper alone will obtain a false picture. It emphasizes the restrictions and precautions. What they should study is the new Constitution. I have had a new draft prepared and I have compared it with the Constitutions of the Dominions. I can assure the House that there is nothing in it that might not be in the Constitution of a Dominion. In fact, in one respect it goes much further than any Dominion Constitution except that of Eire. It provides specifically and positively for responsible government; and this means responsible government in all matters of administration, civil and military, internal and external.” He concluded his speech by saying, “The present proposal is for an interim period. We want Dominion Status in the shortest possible space of time. To achieve it we must show not only that we have successfully worked the self-government that the White Paper promises, but also that we are fundamentally agreed no matter what may be our politics or communities. In a short time, the Cabinet will demand the fulfilment of the promises in the White Paper. Their hands can be immensely strengthened by this House and now. Every time we ask for a constitutional advance we are met by the argument that we are not agreed. Let us show that we are agreed by accepting this motion with a majority so overwhelming that nobody dares to use the argument against us again. I am not asking for a majority; I am asking for a unanimous vote. “It is because of that danger that I do not want communal representation; it is not that I object to two seats here or two seats there. As long as there is this feeling that each community should be separated politically, that there should be this cleavage between community and community, those ideas will penetrate into our whole social life, our whole economic life, into all our activities in this country” And for what are you being asked to vote? It is a motion to wipe out the Donoughmore Constitution with all its qualifications and limitations and to place the destinies of this country in the hands of its people. It is a motion to end our political subjection and to enable us to devote ourselves to the welfare of the Island freed from these interminable constitutional disputes. A vote for this motion is a vote for Lanka, and it is a pleasure and a privilege to move it.” The State Council endorsed the Motion in an unprecedented manner; fifty-one Members voted for it while only three voted against it. Those who voted against were two Indian Tamils and one Sinhalese namely W. Dahanayake. D.S. Senanayake triumphantly cabled Lord Soulbury that he obtained 95% of the vote in favour of the proposals. Dominion Status that was promised within three years after the adoption of the White Paper was granted in two years. In February 1947, D.S. Senanayake addressed a personal letter to the Secretary of State through the Governor requesting that Dominion Status be granted to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). This request was supported by the Governor. Three months later, in June 1947, an announcement was made in the House of Commons that, as soon as the new government assumes office, negotiations would begin to confer ‘fully self-governing Status’ to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The General Election was held in August 1947, The United National Party became the largest party in the House of Representatives, and since D.S Senanayake had the support of the majority of the Members he became the obvious choice as Prime Minister. The Ceylon Independence Bill was introduced in the House of Commons on 13th November 1947, and on 10th December 1947, The Ceylon Independence Act received Royal Assent. On 3rd February 1948 Ceylon (Sri Lanka) ceased to be a Colony. Four Hundred years of foreign domination came to an end and D.S. Senanayake took his rightful position as the ‘Father of the Nation’. Sri Lanka never modelled itself or followed India’s path to Independence. Until the eleventh hour, India was demanding Swaraj and not Dominion Status. During this period India was involved in widespread demonstrations advocating non-corporation and asking the Imperial Government to quit India while almost all their leaders were languishing in jail. It was perhaps the decision to create Pakistan that made them change their demand to Dominion Status within the Empire, the position Ceylon (Sri Lanka) clung to from the very inception. The creation of Pakistan not only marked the division of India but also brought about unprecedented communal violence where millions lost their lives. The only country that took India’s demand of ‘Swaraj’ to its logical conclusion was Burma and even Burma after becoming an independent nation outside the Empire, proceeded to sign a defence agreement with the United Kingdom. On the other hand, D.S. Senanayake never deviated from his demand for Dominion Status. He was successful in uniting all communities and united, marched to freedom without shedding a drop of blood. It is the sheer ignorance of these facts that has prompted some to erroneously believe that Sri Lanka’s freedom was an extension of India’s Independence. Sceptics have castigated our independence as a half-baked measure and that it was not real freedom. “Defence Agreements entered into with the British Government have been highlighted to show that Sri Lanka was never really free and that real freedom came in 1956 when the Defence Pact was abrogated. One begins to wonder how a Pact can be abrogated unless the Country concerned had the right to do so. It was the inherent right of Independence that allowed the abrogation of the Defence Pact. The independence of a country is not judged by the presence of defence pacts or the presence of foreign forces in the country concerned, but on the right of that country to abrogate such pacts or remove foreign troops if they so desire. Even today free nations stationing of foreign troops and holding defence pacts can be seen all over the world. D.S. Senanayake did enter into a Defense pact with the United Kingdom not because it was forced on him but because he wanted it as a safeguard from external aggression. Introducing these agreements in Parliament on 3rd December 1947, D.S. Senanayake told Parliament that, “The agreements became necessary for no other reason but because of the obligations that Britain had undertaken on our behalf. There was, therefore, this necessity for an agreement before Dominion Status was granted. Besides that, our own interest needed to have an agreement to provide for our defence.” “Now with regard to this Agreement, my Good Friend was not quite logical when he said that we would be prevented from terminating this agreement by virtue of the fact it did not stipulate a definite period, and that therefore we have no remedy. But these are mutual agreements to be entered into at different times. There is no question of giving bases to anyone. There was a question bases being found in Ceylon, but I was certainly not prepared to grant any. What I felt was that if at any time we wanted the assistance of England we should be able to get that assistance by agreement, and if necessary for that purpose to get their aeroplanes we should give them aerodromes. There is no question of any bases being given to her. They were only to be given when it becomes necessary, in our own interest, and after entering into an agreement.” So far as these agreements are concerned, it has definitely stated that they will be in force only during such time as they are necessary.” Referring to the Defence Agreement sought by Burma that had become independent from the United Kingdom, he went on to say, “As far as Burma is concerned, she has got independence outside the British Empire, but she has come to an agreement with Britain. She is independent, but there is an agreement with Britain – ……. Now that is a country that has obtained independence. But the people feel that it is in the interest of Burma itself and in the common interest to come to such an agreement. But as far we are concerned, what is the position? We say we belong to one family, we have mutual interests, and it is by mutual agreement that we are able to decide what is to be done. I feel that does not in any way remove our independence; it only means that we can maintain our independence” in our country. There is a good deal more that I should like to say, but I think I have said enough. I feel sure that no’ Member of this House or anyone outside can say that we could have more speedily better and more secure Agreements than those we have got. All those who have the love of this country at heart should rejoice not only over our getting freedom but over securing these Agreements, so that we may be safe in Ceylon.” Parliament approved these agreements on 3rd December 1947. Incidentally, even S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike who abrogated this pact in 1956, voted in favour of these agreements. What he did may have been a popular decision as cutting off ties with the former Colonial Ruler was widely acceptable emotionally. But it certainly did expose Sri Lanka to brazen interference by our giant neighbour and we still continue to pay a heavy price for it.  D.S. Senanayake never advocated that Sri Lanka should have a permanent Defence Pact with the United Kingdom but that to protect our newly won freedom we need the protection of a powerful Nation and at that time the best source was the United Kingdom. Referring to this predicament as far back as 23rd November 1944, speaking in the State Council of Ceylon on Reforms (Introduction of Constituent Bill), he stated, “It may be that there will be a time when perhaps the British will not be our best shield; we may then join some other Commonwealth or come to some arrangement with some other people. But as long as there is no nation I could think of which is better than the British, I would like to get Dominion Status for Ceylon within the Empire. Now at this time, when countries, even big nations, consider it necessary that they should come to some arrangement for the protecting each other, I think it would be foolhardy on our part to think that we can stand by ourselves.” Harbouring deep suspicions on the intentions of our giant neighbour; D.S. Senanayake was convinced that we need a defence arrangement with a powerful country for our safety. However, after his demise in 1952, the United National Party Government led by Sir John Kotelawala was defeated in 1956 and S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike who was elected Prime Minister proceeded to abrogate the defence pact with the United Kingdom. What followed thereafter was blatant interference in our internal affairs and continued infringement of our sovereignty. What we had to experience and continue to experience to date, more than justifies D.S. Senanayake’s suspicions. Sri Lanka was plagued with a foreign-sponsored armed terrorist organization committed to the division of our country. It took a herculean effort from our armed forces to free the country from this brutal terror. Now, in the name of peace, another threat armed with international repercussions has emerged that threatens the very existence of this nation. It is our bounden duty to save our country from being dismembered and its dominance passed to Foreign Nations. If not greatest .disservice will be done to our National Heroes and another despicable betrayal will be featured in our history.  ***** ***** Share this:Filed under accountability , architects & architecture , British imperialism , colonisation schemes , constitutional amendments , democratic measures , governance , historical interpretation , legal issues , life stories , nationalism , patriotism , politIcal discourse , power politics , Sinhala-Tamil Relations , sri lankan society , truth as casualty of war , unusual people , welfare & philanthophy , world events & processes One response to “ Remembering DS Senanayake on Sri Lanka’s Independence Day ” Sri Lankans love to live in the past remembering, commemorating leaders and kings. Time to change the gear from reverse position to a forward position. Leave a Reply Cancel reply- Sri Lanka A beat South Africa in South Africa … A Feat

- Chance Encounters: A Pot Pourri of Books on Sri Lanka

- The Roberts Oral History Project, 1964-1969: Its Conception, Inception & Outcomes

- Up Yours! The English Middle Finger INSULT Directed at the French

- The Stark Political Choices Facing Sri Lanka’s Voters

- Professor EOE Pereira’s Central Role in Fostering Engineering Education

- Gamini Goonetilleke’s Wide-ranging Medical Work in Lanka

- An Intriguing Photo: Charlie Chaplin at the Dalada Maligawa in 1932

- The “Deep State”– Threats to Democracy within Today’s Western States’its

- Face-to-Face in Admonishment: Drama at the Adelaide Oval, 23rd January 1998

- 9/11 Attacks (1)

- Aboriginality (30)

- accountability (3,512)

- Afghanistan (47)

- Africans in Asia (6)

- Afro-Asians (8)

- Al Qaeda (70)

- american imperialism (674)

- ancient civilisations (137)

- anti-racism (117)

- anton balasingham (26)

- arab regimes (106)

- architects & architecture (277)

- architectural innovation (4)

- art & allure bewitching (806)

- Artic exploration (1)

- asylum-seekers (248)

- atrocities (591)

- Australian culture (445)

- australian media (653)

- authoritarian regimes (1,044)

- biotechnology (35)

- Bodu Bala Sena (23)

- Britain's politics (24)

- British colonialism (576)

- British imperialism (314)

- Buddhism (184)

- Canadian politics (5)

- caste issues (91)

- centre-periphery relations (1,442)

- charitable outreach (407)

- chauvinism (145)

- China and Chinese influences (274)

- citizen journalism (286)

- climate change issues (7)

- Colombo and Its Spaces (77)

- colonisation schemes (43)

- commoditification (198)

- communal relations (989)

- conspiracies (216)

- constitutional amendments (205)

- coronavirus (110)

- counter-insurgency (23)

- cricket for amity (473)

- cricket selections (196)

- Cuba in this world (3)

- cultural transmission (2,562)

- de-mining (4)

- debt restructuring (38)

- democratic measures (685)

- demography (130)

- devolution (143)

- disaster relief team (51)

- discrimination (416)

- disparagement (821)

- doctoring evidence (250)

- Dutch colonialism (33)

- economic processes (1,845)

- education (1,055)

- education policy (99)

- Eelam (213)

- electoral structures (193)

- elephant tales (54)

- Empire loyalism (31)

- energy resources (68)

- environmental degradation (29)

- espionage (4)

- ethnicity (1,210)

- European history (86)

- evolution of languages(s) (11)

- export issues (60)

- Fascism (108)

- female empowerment (307)

- foreign policy (459)

- fundamentalism (357)

- gender norms (53)

- gordon weiss (48)

- governance (1,835)

- growth pole (78)

- hatan kavi (18)

- heritage (2,030)

- Hinduism (40)

- historical interpretation (3,830)

- historical novel (7)

- Hitler (62)

- human rights (487)

- IDP camps (68)

- IMF as monster (16)

- immigration (114)

- immolation (15)

- indian armed forces (25)

- Indian General Elections (10)

- Indian Ocean politics (1,056)

- Indian Premier League cricket (1)

- Indian religions (145)

- Indian traditions (256)

- insurrections (132)

- intricate artefacts (3)

- irrigation (19)

- Islamic fundamentalism (310)

- island economy (1,197)

- Jews in Asia (20)

- jihad (135)

- jihadists (17)

- Kandyan kingdom (42)

- land policies (106)

- landscape wondrous (2,716)

- language policies (366)

- law of armed conflict (375)

- Left politics (268)

- legal issues (1,013)

- leopards in the wild (2)

- liberation tigers of tamil eelam (23)

- life stories (5,038)

- literary achievements (384)

- LTTE (1,066)

- marine life (6)

- martyrdom (271)

- mass conscription (42)

- medical marvels (48)

- medical puzzles (37)

- meditations (461)

- Middle Eastern Politics (88)

- military expenditure (89)

- military strategy (792)

- modernity & modernization (876)

- Muslims in Lanka (190)

- nationalism (579)

- nature's wonders (66)

- news fabrication (179)

- nuclear strikes & war (2)

- Pacific Ocean issues (25)

- Pacific Ocean politics (42)

- paintings (35)

- Palestine (26)

- Paranagama Report (13)

- parliamentary elections (114)

- patriotism (1,136)

- people smugglers (65)

- performance (1,687)

- photography (427)

- photography & its history (12)

- pilgrimages (142)

- plantations (41)

- plural society (124)

- political demonstrations (260)

- politIcal discourse (3,850)

- population (207)

- Portuguese imperialism (25)

- Portuguese in Indian Ocean (78)

- power politics (2,450)

- power sharing (292)

- prabhakaran (369)

- Presidential elections (118)

- press freedom (90)

- press freedom & censorship (88)

- propaganda (471)

- psychological urges (91)

- pulling the leg (65)

- racism (74)

- racist thinking (182)

- Rajapaksa regime (1,029)

- Rajiv Gandhi (37)

- reconciliation (689)

- refugees (87)

- rehabilitation (304)

- religiosity (452)

- religious nationalism (147)

- Responsibility to Protect or R2P (99)

- revenue registers (2)

- riots and pogroms (120)

- Royal College (27)

- Russian history (32)

- S. Thomas College (33)

- Saivism (32)

- sea warfare (15)

- security (967)

- self-reflexivity (3,221)

- Sinhala-Tamil Relations (1,940)

- slanted reportage (750)

- social justice (332)

- Sri Lankan cricket (340)

- Sri Lankan scoiety (59)

- sri lankan society (3,986)