FAQ: 10 common speech error patterns seen in children of 3-5 years of age – and when you should be concerned

Speech is a wonderfully complex skill, and children need lots of practice to learn how to do it. As with any motor skill, children make plenty of mistakes as they learn to speak clearly.

In English, we hear several common patterns of error in children’s speech as they grow up. Here are 10 common types of error pattern, and the approximate age by which we expect them to be ‘fixed’ (gone) in typically developing children:

1. Assimilation:

Lala wants the lellow kuk. (lara wants the yellow truck.).

It’s human nature to do as little work as possible, and our tongues, lips and other ‘articulators’ can be just as lazy as the rest of us! Often one sound in a word will affect one or more other sounds in the word. This is called assimilation (or consonant harmony) . Sometimes, the first sound in a word will change later sounds, e.g. if the child said ‘beb’ for ‘bed’. This is called progressive assimilation. Other times, later sounds in a word affect earlier sounds, e.g. if a child says ‘lellow’ for ‘yellow’. This is called regressive assimilation.

When to consider seeking help: if assimilation is still a feature of your child’s speech at the age of 2½-3 years of age.

2. Reduplication:

The taitai needs wawa. (the tiger needs water.).

When children repeat a syllable twice, rather than pronouncing both syllables of the word, they can sound a bit like babies babbling (e.g. mama, dada). When we hear it in 3-5 year olds, we call this error pattern reduplication . It almost always happens when the child repeats the stressed syllable twice, at the expense of the weak syllable, e.g. as in tiger and water above.

When to consider seeking help: if your child is 2½-3 years old or older and reduplicating syllables more than occasionally.

3. Voicing:

I fount a pek for the bram. (i found a peg for the pram.).

The sentence above makes no sense whatsoever. But it allows me to illustrate voicing errors . In English, we produce some of our sounds with our vocal cords apart. These are called unvoiced sounds, which include sounds like p, t, k, s and sh. For other sounds, we bring our vocal cords together to ‘turn on’ our voices. These are called voiced sounds and include b, d, g, z and n. It takes a lot of control to turn your voice on and off during speech, and it’s not unusual for some children to make errors like not voicing sounds when they should (e.g. pek instead of peg) or voicing sounds when they shouldn’t (e.g. bram instead of pram).

Age at which you should you consider therapy: 3 years (or younger if your child is being teased for it).

4. Final consonant deletion:

Gi me my du ma ba. (give me my duck mat back.).

Young children often omit the final consonants in their words. This is called (appropriately enough) final consonant deletion . It can have a big impact on how easy your child is for others to understand – could you understand the example sentence above without the translation?

When to consider seeking help: if your child is regularly omitting final consonants in words at the age of 3 years, 3 months.

5. Fronting:

Sorn tan’t find any eds to teep. (sean can’t find any eggs to keep.).

This type of error is called fronting . It occurs when sounds normally produced with the tongue positioned at the back of the mouth (e.g. k, g and sh) are instead produced with the tongue positioned towards the front of the mouth (e.g. like t, d, and s).

Age at which you should you consider therapy: 3½-4 years of age (or younger if your child is hard for others to understand or being teased for it).

6. Stopping:

Da ban crac into dit debra. (the van crashed into this zebra.).

This ghoulish sentence illustrates stopping . In English, many speech sounds can be stretched out and held continuously until you run out of breath. Sounds like s, z, f, v and th, are good examples. Other speech sounds can’t be held continuously, e.g. p, b, t, d, k and g, which are all examples of ‘plosives’. It’s common for young children to substitute plosives for continuous sounds. We call this ‘stopping’ because the children are ‘stopping’ the sounds, e.g. turning the ‘this’ with its nice continuous ‘th’ and ‘s’ sound into ‘dit’.

Age at which you should you consider therapy:

- 3 years of age for ‘f’ or ‘s’ (or younger if your child is being teased for it);

- 3½ years of age for ‘v’ or ‘z’ (or younger if your child is being teased for it);

- 4½ years of age for ‘sh’, ‘j’ or ‘ch’ (or younger if your child is being teased for it); and

- 5-7 years of age for ‘th’ (as in ‘thin’) and ‘th’ (as in ‘the’) (or younger if your child is being teased for it).

7. Weak syllable deletion:

The efant needs a brela. (the elephant needs an umbrella.).

When we speak, we don’t emphasise each of our syllables equally. For example, in the word ‘telephone’, we usually place the stress on the ‘te’ and ‘phone’, leaving the ‘le’ syllable in the middle un-stressed and weak. In ‘umbrella’, we stress the ‘bre’, leaving the ‘um’ unstressed and weak. I’ll spare you a lecture about Trochaic and Iambic stress patterns in English. Why I mention stress patterns is that it’s common for young children to omit weak syllables. We call this weak syllable deletion .

Age at which you should you consider therapy: 4 years (or younger if your child is being teased for it).

8. Cluster Reduction:

There’s a ‘cary ‘pider in my room (there’s a scary spider in my room).

Many words in English contain combinations or ‘clusters’ of consonants, e.g. squawk, crab or flower. It’s common for young children to omit one or more of the consonants in a cluster (so called cluster reduction ), and there are some clever rules of thumb speech pathologists use to help us predict which ones.

Age at which you should you consider therapy: 4-5 years (or younger if your child is hard for others to understand or is being teased for it).

9. Deaffrication:

“zhack broke my wash”. (‘jack broke my watch.’).

This one has a fancy name – deaffrication – and needs some explanation.

The word “affricate” comes to us via German from the same Latin root as friction, meaning ‘ rub together ’. In English, we have two affricate speech sounds – ‘ch’ (as in “chat”) and ‘j’ (as in “Jack”). Each is made by “rubbing together” two speech sounds:

- the “ch” sound in “check” – transcribed as /t ʃ/ in the International Phonetic Alphabet or IPA – is a combination of /t/ (as in “tell”) and “sh” (/ ʃ/), as in “shell”; and

- the “j” sound – transcribed as /d ʒ/ in IPA – is a combination of /d/ (as in “dog”) and “zh” (/ ʒ/ in IPA), as in the middle of “vision”.

Deaffrication occurs when an affricate is simplified by leaving out the first speech sound of the pair, e.g., when:

- “chain” (/t ʃein/) is pronounced as “Shane” (/ʃein/);

- “watch” /wɒtʃ/ is pronounced as “wash” (/wɒʃ/);

- “Jack” (/d ʒaek/) is pronounced as “Zhack” (/ʒaek/); or

- “hedge (/hɛdʒ/) is pronounced as “hezh” (/hɛʒ/).

Age at which you should you consider therapy: 5 years of age (or younger if your child is being teased for it).

10. Gliding:

The wabbit woves wed wibbons. (the rabbit loves red ribbons.).

We call this error pattern gliding . It’s most common with r and l. Two year olds who glide are often praised for their cuteness. Gliding is not so adorable when you’re seven.

Age at which you should you consider therapy: 5-6 years of age (or younger if your child is being teased for it).

Other considerations

In reality, young children – especially 2 and 3 year olds – often make many of these errors in the same sentence, e.g. ‘dec a tary fwigt’n pider in my woo’. This can make it very difficult for adults who don’t know a child well to understand what he or she is trying to communicate.

The above suggested ages for considering seeking help are, of course, only guides. You are the expert on your child and you should always feel free to discuss your child’s speech development with a speech pathologist.

As a general rule, if:

- your child’s speech is noticeably less developed or easy to understand than that of his or her peers;

- your child shows signs of anxiety or frustration about his or her speech;

- your child is self-conscious about his or her speech, or is being teased or bullied;

- your child’s childcare, pre-school or school teachers flag concerns about your child’s speech;

- you simply want to check that there’s nothing to worry about; or

- your child’s speech features any of these error patterns at 5 years of age,

we recommend you contact a speech pathologist to discuss your concerns.

Principal sources : Dodd, Hua, Crosbie, Holm & Ozanne (2002); Grunwell (1987); McLeod (1996); Bowen (1998).

Related articles :

- Lifting the lid on speech therapy: how we assess and treat children with unclear speech – and why

- My child’s speech is unclear to adults she doesn’t know. Is that normal for her age? (An important research update about child speech intelligibility norms)

- 12 speech-related warning signs that your child might have a hearing problem

- Important update: In what order and at what age should my child learn to say his/her consonants? FAQs

- Speech sound disorders in children

- How to treat speech sound disorders 1: the Cycles Approach

- How to treat speech sound disorders 2: the Complexity Approach

- How to treat speech sound disorders 3: Contrastive Approach – Minimal and Maximal Pairs

- How to identify and treat young children with both speech and language disorders

- ‘He was such a good baby. Never made a sound!’ Late babbling as a red flag for potential speech-language delays

- Why preschoolers with unclear speech are at risk of later reading problems: red flags to seek help

Image : http://tinyurl.com/neoc5by

Hi there, I’m David Kinnane.

Principal Speech Pathologist, Banter Speech & Language

Our talented team of certified practising speech pathologists provide unhurried, personalised and evidence-based speech pathology care to children and adults in the Inner West of Sydney and beyond, both in our clinic and via telehealth.

Share this:

David Kinnane

Banter Quick Tips: The mirror trick for sounding out words

My child’s speech is hard to understand. Which therapy approach is appropriate?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

© 2024 Banter Speech & Language ° Call us 0287573838

Copy Link to Clipboard

Psycholinguistics/Speech Errors

- 1.1 An Overview of Speech Errors

- 1.2 Phoneme Errors

- 1.3 Beyond vowels and consonants

- 1.4 Syllable Errors

- 1.5 Morpheme Errors

- 1.6 Affix Substitution

- 1.7 Syllable Stress

- 1.8 Freudian Slips

- 2.1 Phonotactic Regularity Effect

- 2.2 Consonant-Vowel Category Effect

- 2.3 Initialness Effect

- 2.4 Syllabic Constituent Effect

- 3 Footnotes

- 4 References

- 5.4.1 Part 1

- 5.4.2 Part 2

Errors in Speech Production

“A Tanadian from Toronto”. We are all guilty of producing such speech errors and other slips of the tongue in our day-to-day communications. Speech errors have long been a source of amusement for many, a source of frustration for some, and more recently a source of serious study in the field of psychology. Although these errors are good for a laugh now and then, they prove to be of much greater value to the field of linguistics. Speech errors are providing linguists with insight into the mechanisms behind speech production. There are limitations to how much is available for study; the process of speech production is largely inaccessible for observation. However, by analyzing errors individually and in the context of their surroundings, we may better learn the underlying mechanisms that occur to produce our speech, and investigate the reality of speech production units in word formation [ 1 ] . This chapter will introduce the different types of commonly documented speech errors, the rules that govern error-generation, and how these errors provide insight into some of the proposed speech production models. The nature of speech errors in this chapter will be based on speakers who have no pre-existing speech delays or disorders. These are errors made by speakers whose language and speech production systems are thought to be fully intact. First, let us start by introducing the smaller errors and then work our way up through a hierarchy based on size of units subject to the error.

An Overview of Speech Errors

Early estimates suggested upwards of 10 000 different speech errors are committed in the English language [ 2 ] . These errors have become the source of investigation and experimentation in search of explanation of the basic processes that conduct speech production; from the basic stages of planning to the finished motor plan that produces audible speech [ 3 ] . A preliminary finding from error observations is that errors occur mainly within the same level of speech production rather than between levels of production. For example, this means in the occurrence of units being exchanged that one phoneme will change with another phoneme, but will not change with a syllable as it is a speech unit existing on a separate level of production [ 4 ] . First, let us familiarize ourselves with nine commonly documented speech errors:

Addition: adding a unit

Anticipation: a later speech unit takes place of an earlier one

Blends: two speech units are combined

Deletion: a unit is deleted

Exchange: two units swap positions

Misdeviation: a wrong unit is attached to a word

Perseveration: speech unit is activated too late

Shift: affix changes location

Substitution: unit is changed into a different unit

All different types of speech units are victims of speech error. Above we see changes in features, syllables, morphemes, affixes, words, and syntax. It must be acknowledged that classification of errors is no easy task as some errors are co-occur between different units of speech. Classification can at times be ambiguous. For example, an error such as "hit the spot" (as opposed to the intended word pot ) could be considered a phoneme addition, or also a word substitution.

Phoneme Errors

Errors made at the level of the phoneme, whether it be substitution, addition, deletion, or any others for that matter, are by far the most common speech errors [ 1 ] . An error at this level can occur within a word but more frequently will occur between separate words. The majority of these phonemic errors are anticipations , in which a substitution occurs of a sound that is supposed to occur later in the sentence. In this case, the speaker produces the target phoneme earlier than intended and it interferes with the intended original phoneme; the interfering segment follows the error.

a) also share→ alsho share

b) sea shanty→ she shanty

Second in frequency to phonemic anticipation errors are perseverance errors (the interfering segment precedes the error), which are as follows:

a) walk the beach→walk the beak

b) Sally gave the boy→Sally gave the goy

The very nature of these errors, and the fact that they occur indicate that speech is well planned before it is articulated. As words get confused, like we saw above, we could speculate that all words of a sentence exist as part of a single representation in production and are therefore susceptible to being mixed at that stage in planning. Of course this is intuitive as a sentence could not be created if words were held as separate representations; at some point down then line the words must be integrated and related to create and complete the sentence. Dell et al., [ 5 ] noted a difference between perseverations and anticipations depending on the context of the sentence. If one is speaking a novel sentence, they are more prone to perseverations, where as anticipations are more common amongst practiced and recited phrases [ 6 ] .

Another possible phonemic error is the exchange of two segments, where the order of sound segments gets changed. Exchange errors have been interpreted as the possible combination of an anticipation and a perseverance [ 1 ] .

a) feed the dog→ deed the fog

b) left hemisphere→ heft lemisphere

These phonological errors always involve the exchange of like units; a vowel exchanges with a vowel and a consonant with another consonant. Never is there an exchange between a vowel and a consonant. This is known as the consonant-vowel category effect [ 6 ] .

Beyond vowels and consonants

All of the above examples involved the anticipation, perservation, or exchange of single segments. Errors consisted of small segments such as a vowel or a consonant. These individuals segments can further be combined. As individual segments, two consonants can be transposed. By addition of a consonant to a word, a cluster can be produced as opposed to an intended single segment, as follows:

Fish grotto→ Frish gotto

This is similar in all respects to the previously shown single segmented errors, the only difference now being that the affected segment has become a consonant cluster. A cluster however is not a single unit in speech production, but consists of a sequence of separable segments.

Syllable Errors

Although our focus on speech errors has thus far been on small-segment phonemic errors, this does not mean that errors amongst phonemes are the only source of speech error. Larger than phonemes are syllables that are also units of speech performance and susceptible to error. Nooteboom (1969) [ 7 ] was the first to suggest that syllables could be a unit of measure in speech programming. He found that speech errors generally occur within seven syllables distance between the origin and target. This corresponds and fits with our understanding of a short-term memory span that allows us to comfortably remember seven consecutive items [ 1 ] . Anything beyond this magic number of seven becomes challenging. Nooteboom supported the notion that segmental slips yield to a structural law of syllable placement. If we have two words, each with an equal amount of syllables, the corresponding syllables will be the ones to exchange in the event of an error. The first syllable of the origin word will replace the first syllable of the target word. Likewise, the final syllable of the origin word will exchange with the final syllable of the target word.

Moran and Fader→ Morer and Fadan

In further support of syllables being a unit of articulation, syllabic errors also occur as blends, substitutions, deletions, and additions.

Tremendously→tremenly (deletion of syllable)

Shout+yell= shell (blending of syllables)

Morpheme Errors

As we continue up our hierarchy of speech units, we now see that units of meaning are susceptible to speech errors. Such errors tend to happen subsequent to the syntactic planning of the sentence [ 1 ] . Even units as large as an entire word can be subject to an error such as exchange .

Bowl of soup→soup of bowl

Plant the seeds→plan the seats

Substitutions and exchanges of whole words occur but do so with like-constituents. A noun will take place of a noun, and the same goes for an adjective or verb. When there is a change in word placement but no change in morphemes, the error is said to consist of inflectional morphemes. However, when the root of the words remains and there is an error due to a morpheme addition or substitution, the error is known as a derivational morpheme error.

Bed time→time bed (inflectional)

Easily enough→easy enoughly (derivational)

Such derivational speech errors show that semantic intentions are intact, however, the choice of semantic features has been incorrect. Substitutions can also occur where the substituted word is structurally similar but semantically different from the intended word [ 1 ] .

Affix Substitution

He was very productive→ he was very productful

Documentation of errors involving word affixes provides us with insight as to how words are stored and later produced in speech. An error such as the one above leads one to believe that the word 'productive' may be stored in the mental lexicon as two separate constituents. It is possible that the correct version is stored as product + ive, which is suggestive of rules for word formation. From such errors we may infer that there exists separate vocabularies for stems and affixes. The improper pairing of an affix (product+ful) then leads to a word that is impermissible by the rules of our language. This evidence supports the hypothesis that affixes are a source of speech error and that they may exist as a separate component of one’s lexicon [ 8 ] .

Syllable Stress

In articulation of a sentence, there is a segment of primary stress at which one syllable will be stressed more than the others. Regardless of whether it is a vowel, a whole syllable, part of a syllable, or even a whole word being involved in substitution, the pattern of stress within the sentence does not change. Take for example the following error:

How great things were→ how things were great

In articulation of a sentence, there is a segment of primary stress at which one syllable will be stressed more than the others. Boomer and Laver suggest that despite an error of word exchange, the position of the primary stress in the sentence remains the same (in this case on the second word of the sentence) [ 1 ] .

Freudian Slips

Freud focused on the common errors we make in our day-to-day processes and made these errors a central point of his studies. Verbal errors (or more commonly: slips of the tongue) have since been titled Freudian slips. These are errors in speech (or memory and physical action) that are said to occur due to the interference of an unconscious wish, need, or thought. For example, a man calling his spouse by the name of his previous partner.

At first glance, Freudian slips seem like a gold mine for speech error research, however, they pose some difficulty in regards to research with the model of speech production. With our current linguistic tools, we are unable to tap into the unconscious processes of language production [ 6 ] . With no access; we do not know the intentions that lie behind these errors, unlike the other speech errors we previously examined. Therefore, we cannot make any inference about these errors. To use these slips would require a vast knowledge of the inner-self of the speaker, something that is currently largely inaccessible. Until we develop such methods to do so, this resource of unconscious errors will remain largely untapped.

Speech errors in support of Language Production Models

A general consensus exists amongst linguistic theorists that words and sentences exist as a combination of structure and content. A complete sentence requires words to create meaning, and that the syntax and relation amongst words be permissible within the language. Meaning and syntax reflect content and structure, respectively. The content of words contains a series of phonological features and the structure entails the combination of these features into larger units of speech organization. Modern psychological theories stress the importance of separation between structure and content. Chomsky (1957) [ 9 ] stated that creating a sentence requires different levels of representation. Agreeing with later theorists, it is suggested that a semantic representation is created first. Succeeding this representation are two linguistic representations, one with syntactic information and the other with phonological information. These representations are what eventually direct motor activity in the production of speech [ 10 ] . The following evidence from speech provide support for this theory of language production:

Phonotactic Regularity Effect

Errors at the level of the phoneme habitually end up being sound sequences that are possible within the rules of that given spoken language. This effect was established to be the “first law” of speech errors by Wells (1951) [ 10 ] and has been a central focus of speech error research since. There are,however, violations to this first law. There are 37 found examples of violations (Stemberger 1983) [ 10 ] , but this amounts to less than one percent of all noted phonological speech errors [ 10 ] . This proves the phonotactic regularity effect to be significant as its prevalence is seen in such a vast majority (99%) of errors.

a) A reading list→ a leading list (no violation of English rule)

b) dam→ dlam (a rare case of violation)

In consideration of speech production theories with the phonotactic regularity affect, frames are created with only letter combinations that are permissible within the language. Impossible sound sequences are prohibited in word construction. It is assumed that there is no available frame for an illegal sequence such as 'dlam' to be created [ 10 ] . This is understood as concrete evidence that phonological rules are actively considered in the process of speech production [ 1 ] .

Consonant-Vowel Category Effect

As mentioned earlier, like-units are prone to exchange, but not differing units. A noun slips with another noun, and a verb with another verb. In a similar fashion, vowels and consonants (basic phonological units) only slip with their similar partner; a vowel for a vowel, and a consonant for a consonant. The rate at which this occurs in speech errors is even greater than the phonotactic regularity effect, meaning there are even fewer exceptions to the consonant-vowel category effect (<1%) [ 10 ] . Instances of cross-category errors are extraordinarily rare, in fact, some say they do not occur at all [ 10 ] . The consonant-vowel category effect is considered to be evidence of labeled slots in the frame for production. Labels indicate whether a vowel or a consonant will be accepted into a particular slot, and will only accept the segments (consonant or vowel) that correspond with the correct category. This is a preventative measure that disallows the event of a cross-category error.

Initialness Effect

Initial consonants (onset consonants) are consonants that begin a syllable or word. There is a far greater inclination for word-initial consonants to slip than those from other regions of the word, with 80% of consonant slips coming from word-initial consonants [ 10 ] . In explanation of this effect, MacKay (1972) and Shattuck-Hufnagel (1987) hypothesize that initial consonants of syllables and words have a distinct representation in the phonological frame [ 10 ] . This idea suggests that initial consonants in syllables and words are more detachable from the remainder of the word and would therefore be more susceptible to error and exchange. For example, in the word 'fog', the f -sound is more easily extracted and isolated than the sound of the g . The ease with which the initial consonant f can detach is thought to be in correspondence with a principal division in the structure of the word frame. Segments following the division prove to be less accessible and more buried in the word.

Syllabic Constituent Effect

The syllabic constituent effect occurs when a neighboring vowel and consonant are exchanged as a VC or CV unit with another similar pair. The sequence of vowel-consonant proves to be more susceptible to error than the sequence of consonant-vowel [ 7 ] . Nootboome (1969) noted that of 24 collected phonological errors, 19 involved a VC sequence and only four involved a CV sequence. This effect provides support for a phonological frame that has structure within its syllables. A typical sequence of consonants and vowels follows the CVC pattern, where the first consonant is the onset consonant of the syllable, and the succeeding vowel and consonant combine to form a single unit; the rhyme constituent of the syllable. The fact that VC slips are far more common than CV slips provides further evidence that phonological structure plays a role in the production of the speech frame [ 10 ] .

Taken into consideration separately, each of these effects unveil the functioning of different phonological rules and structures that may be at work in language production. Evidence from the corpus of naturally occurring speech errors and the underlying effects within speech errors supports multiple levels of linguistic analyses in the process of speech production. This growing body of evidence from naturally occurring speech errors suggests that speech production begins begins with a semantic and structural plan. Following this foundation is the progression to accessing the proper words, and finally the application of proper phonological information. With a greater understanding of speech errors comes an understanding of the speech production process. This will ultimately lead to an increased understanding or our means of communication; language.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Fromkin, V.A. (1973). Speech errors as linguistic evidence. The Hague: Mouton

- ↑ Meringer, R., & Mayer, K. (1895). Misspeaking and Misreading: A psycholinguistics study. Stuttgart, Germany: Goschense Verlagsbuchhanlung.

- ↑ Lashley, K.S. (1951). The problem of serial order in behavior. In L.A. Jeffress, Cerebral mechanisms in behavior (pp. 112-136). New York: Wiley.

- ↑ Dell, G.S., Reed, K.D., Adams, D.R., & Meyer, A. (2000). Speech errors, phonotactic constraints, and implicit learning: A study of the role of experience in language production. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26, 1355-1367.

- ↑ Dell, G.s., Burger L.K., & Svec, W.r. (1997). Language production in serial order: A functional analysis and a model. Psychological Review, 104, 123-147.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Jay, T. (2003). The Psychology of Language. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Nooteboom, S.G. (1969). The tongue slips into patterns. Leyden studies in linguistics and phonetics. The Hague: Mouton

- ↑ MacKay, D.G. (1978). Derivational rules and the internal lexicon. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 17, 61-71.

- ↑ Chomsky, N. (1857). Syntactic structures. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 Dell, G.S., Juliano, C., and Govindjee, A. (1993). Structure and content in language production: A theory of frame constraints in phonological speech errors. Cognitive Science, 17. 149-195.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton.

Dell, G.S., Juliano, C., and Govindjee, A. (1993). Structure and content in language production: A theory of frame constraints in phonological speech errors. Cognitive Science, 17. 149-195.

Dell, G.s., Burger L.K., & Svec, W.r. (1997). Language production in serial order: A functional analysis and a model. Psychological Review, 104, 123-147.

Dell, G.S., Reed, K.D., Adams, D.R., & Meyer, A. (2000). Speech errors, phonotactic constraints, and implicit learning: A study of the role of experience in language production. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26, 1355-1367.

Fromkin, V.A. (1973). Speech errors as linguistic evidence. The Hague: Mouton

Harley, T. A. (1984). A critique of top-down independent levels models of speech production: Evidence from non-plan-internal speech errors. Cognitive Science, 8, 191-219.

Harley, T. A. (1990). Environmental contamination of normal speech. Applied Psycholinguistics, 11, 45-72

Jay, T. (2003). The Psychology of Language. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education

Lashley, K.S. (1951). The problem of serial order in behavior. In L.A. Jeffress, Cerebral mechanisms in behavior (pp. 112-136). New York: Wiley.

MacKay, D.G. (1978). Derivational rules and the internal lexicon. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 17, 61-71.

Meringer, R., & Mayer, K. (1895). Misspeaking and Misreading: A psycholinguistics study. Stuttgart, Germany: Goschense Verlagsbuchhanlung.

Nooteboom, S.G. (1969). The tongue slips into patterns. Leyden studies in linguistics and phonetics. The Hague: Mouton

Learning Exercises

Identify the type of errors shown in the following sentences as one of the nine possible errors in speech production (ex substitution, preservation). It is possible for a sentence to contain more than just one type of error. If so, identify the multiple types of errors.

a. Walk the beach→ walk the beak

b. Hop on one foot→ Fop on one foot

c. Pat put the pot on the table

d. On the computer→ on the commuter

e. He had an upset tummy

f. The adds up to→ that add ups to

The following story was written by Tommy, a grade two student at Atlantic Memorial Elementary. It is a recount of his trip to the store on a beautiful weekend day. He plans to submit his story as part of his year end project. Tommy has called upon you to proof read his story!

Identify the types of errors made by Tommy (i.e. perseverance, shifts, deletions, additions etc.) and at which level of production these errors occur (i.e. phonemes, syllables, morphemes). Make the appropriate corrections so he can get the A+ he so greatly desires.

Tommy woke up to a bright sun-shining say. He bate his eggs-benny and got dressed as fast as possible, with an itch to break out the front door into the sunshine. He decide to gos for a walk to Mable’s Country Store. Off he went, with his walking stick in hand, along the trail to the tore. He had the lovely company of the morning birds springing their tune to him along the way, and the river at his side. Not too far along the trail, Tommy realized he had forgot aboutten his money. Being in such a rush, he realized he forgot to deed the fog too! He would need some money to buy a treat at Mables Mountry More, so he turned around and dashed back dome! He shelled at the top of his lungs when the neighborhood hound chased him down the road, but he made it back in the nick of nime. He gathered his money and decided he would bake his ticycle this time to make up for lost time. He made his was along the trail, through the trees birch and at last to the store. For sake of his Saturday morning tradion, he purchased two scoops of strawbry ice cream. Delicious!

In the week following the reading of this chapter, closely listen for and document any speech errors made by yourself and others. Return to this chapter to analyze and relate your documented errors to the content of this chapter. Which types of errors did you find to be most common from this time? Are there any types of errors you have heard frequently in past? Deletions, anticipations, exchanges, or others? Indicate how your documented errors agree, or disagree with such theories as the phonotactic regularity effect or the consonant-vowel category effect. Make note of whether the speaker makes an effort to correct their error, or if it goes unnoticed. Can any conclusions be drawn regarding the level of speech production at which an error has occurred?

a. Walk the beach→ walk the beak (Persevaration)

b. Hop on one foot→ Fop on one foot (Anticipation)

c. Pat put the pot on the pable (persevaration)

d. On the computer→ on the commuter (deletion)

e. He had an upset stummy (blend)

f. The adds up to→ that add ups to (shift)

Sun shining say→ sun shining day (Perseverance. Level: phoneme)

Bate eggs-benny→ ate eggs benny (anticipation: Phoneme. Addition: phoneme)

Decide to go→ decided to go (shift: affix)

Trail to the tore→ trail to the store (perseverance: phoneme)

Springing their tune→ signing their tune (Addition: phoneme. Subtitution: morpheme)

Forgot aboutten→ forgotten about (Shift: morpheme)

Deed the fog→ feed the dog (anticipation and perseverance: phoneme. Combination of anticipation and perseverance= exchange)

Mables Mountry More→ Mables Country Store (Perseverance: phoneme. Substitution: morpheme)

Shelled→ yelled (Blend: syllable)

Nick of nime→ nick of time (Perseveration: phoneme)

Bake his ticycle→ take his bicycle (exchange: phoneme. Substitution: morpheme)

Treed birch→ birch trees (exchange: morpheme)

Tradion→ tradition (Deletion: syllable and phoneme)

Strawbry→strawberry (Deletion: syllable)

- Psycholinguistics

Navigation menu

- Constructed scripts

- Multilingual Pages

Speech Errors and What They Reveal About Language

“They misunderestimated me,” George W. Bush notoriously proclaimed in a 2000 speech about his surprise victory over rival John McCain. This represented just one of many speech errors that George W. Bush would make in his career as president, but it highlights an important point: nobody speaks perfectly, even high-profile politicians who are well-versed in public speaking and have presumably rehearsed their speeches extensively.

By far the most well-known speech errors are Freudian slips, in which the speaker unintentionally reveals his true feelings, breaking his facade of politeness and resulting in an all-around embarrassing situation. For example, a father, upon meeting his son-in-law, might accidentally utter “ Mad to meet you” instead of “Glad to meet you”. Indeed, Freudian slips are entertaining, but they represent only a small sliver of actual speech mistakes that people make.

At face value, real-life speech errors may be less entertaining than Freudian slips. However, the insights they give us regarding our mental lexicon and cognitive underpinnings of language are anything but commonplace. Let’s review some of the most common speech errors, and pick them apart to see what they reveal about how we understand and process language.

Phonological errors

Some speech errors are phonological , or relating to the sounds of a language. Though there are a myriad of ways in which people can pronounce words wrong, we will look at two very common phonological errors: anticipation and perseveration . Perseveration occurs when a sound from a previous word sneaks its way onto a later word. Here are some examples of perseveration:

- He was kicking around a tin tan (instead of tin can ).

- They found a hundred dollar dill (instead of dollar bill ).

Anticipation is the opposite of perseveration: it occurs when a speaker mistakenly uses a sound from a word that is coming later in the utterance. Some examples:

- She drank a cot cup of tea (instead of hot cup of tea).

- He was wearing a weather wristband (instead of leather wristband ).

It’s easy to intuit what is going on with perseveration errors: our tongues, faced with the daunting task of producing many different sounds in very little time, simply got confused, and produced the sound from a previous word. However, anticipation errors -- in which we incorrectly use the sound from a word that hasn’t yet been uttered -- suggest that there is something else going on.

Indeed, linguists have taken the existence of anticipation errors to suggest that our brains plan out all of our utterances, even when we are speaking spontaneously. That is, even before we start speaking, the entire sentence is available on some basic level in our brains. For that reason, words that have not yet been spoken can contaminate our speech and produce anticipation errors.

Substitution errors

Another common type of error occurs when speakers substitute an entire word for a different word that is distinct from the intended one. Here are some examples:

- My CV is too long (instead of short ).

- Look at that cute little dog (instead of cat ).

As the above examples suggest, the erroneously substituted word is not random. Instead, most substitution errors share a few common traits. First, the substituted word and the intended word are almost always of the same syntactic class -- “short” and “long” are both adjectives; “dog” and “cat” are both nouns. You would rarely hear someone say, “My CV is too job”, or “Look at that cute little furry”. Second, the substituted word and the intended word usually share common semantic ground. “Short” and “long” are both measures of length; “dog” and “cat” are both furry pets. It’d be unlikely for someone to accidentally say, “My CV is too green”, or “Look at that cute little boat”.

This suggests that words are structured in our brains with respect to both syntax -- what part of speech the word us -- and semantics -- what words mean. For this reason, substitution errors almost always occur among words that are syntactically and semantically similar.

Foreign-language errors

Most studies about speech errors are conducted with speakers using their native language. However, there has been some research regarding the different types of speech errors made by native speakers and those who learned a language later in life. Unsurprisingly, non-native speakers commit, on average, more errors than their native-speaking counterparts. However, when examining the types of mistakes that native and non-native speakers made, some interesting patterns emerged.

Non-native speakers occasionally substitute words from their first language into their second language. For example, a native English speaker who is learning Spanish might say, “That es importante”, using the English word “that” instead of the Spanish equivalent “eso”. However, these substitutions were not random . They occurred mostly in function words -- that is, words like articles (“the”, “a”) and prepositions (“with”, “to”), which are grammatically necessary but do not offer any meaning on their own.

Therefore, using the above example, the English speaker would be more likely to say “You quiero a hamburguesa”, given that “a” is a function word. These errors suggest that function words are more deeply hard-wired into our brains than other words. It could also explain why topics involving function words -- such as proper use of articles, conjunctions, and prepositions -- often present a special challenge to language learners.

Ultimately, there’s a lot more to speech errors than Freudian slips. Indeed, slips of the tongue may not be quite as revealing of our inner desires as Freud might have thought, but they remain interesting in their own right. They demonstrate to us that we construct plans for our utterances, even in spontaneous speech when we’re not conscious of it. They show us that our brains categorize words based on their syntactic and semantic attributes. And they demonstrate to us that certain classes of words are more ingrained in our brains than others, which offers insight into second language learning and processing.

About the writer

Paul writes on behalf of Language Trainers , a language tutoring service offering personalized course packages to individuals and groups. Check out their free foreign language listening tests and other resources on their website. Visit their Facebook page or contact [email protected] with any questions.

Writing systems | Language and languages | Language learning | Pronunciation | Learning vocabulary | Language acquisition | Motivation and reasons to learn languages | Arabic | Basque | Celtic languages | Chinese | English | Esperanto | French | German | Greek | Hebrew | Indonesian | Italian | Japanese | Korean | Latin | Portuguese | Russian | Sign Languages | Spanish | Swedish | Other languages | Minority and endangered languages | Constructed languages (conlangs) | Reviews of language courses and books | Language learning apps | Teaching languages | Languages and careers | Being and becoming bilingual | Language and culture | Language development and disorders | Translation and interpreting | Multilingual websites, databases and coding | History | Travel | Food | Other topics | Spoof articles | How to submit an article

Why not share this page:

If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon , or by contributing in other ways . Omniglot is how I make my living.

Get a 30-day Free Trial of Amazon Prime (UK)

- Learn languages quickly

- One-to-one Chinese lessons

- Learn languages with Varsity Tutors

- Green Web Hosting

- Daily bite-size stories in Mandarin

- EnglishScore Tutors

- English Like a Native

- Learn French Online

- Learn languages with MosaLingua

- Learn languages with Ling

- Find Visa information for all countries

- Writing systems

- Con-scripts

- Useful phrases

- Language learning

- Multilingual pages

- Advertising

The secrets behind slips of the tongue

The Language Production and Executive Control Lab at Johns Hopkins University investigates why words sometimes fail us

By Kirsten Weir

March 2018, Vol 49, No. 3

Print version: page 60

- Cognition and the Brain

- Neuropsychology

Most of us use the wrong word or misspeak from time to time, saying “squirrel” when we mean “chipmunk,” swapping sounds to utter “Yew Nork” instead of “New York” or calling a partner by a child’s name. Such slipups are more than just a quirk of human language, says Nazbanou “Bonnie” Nozari, PhD, a cognitive psychologist and assistant professor of neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. They’re also valuable tools for understanding the normal processes of speech.

“We have the ability not only to produce language, but to catch our errors when we make them. How do we detect those errors, apply corrections to them and prevent them from coming up again?” she asks.

Nozari aims to answer those questions as founder and head of the four-year-old Language Production and Executive Control Lab at Johns Hopkins University, where she studies the cognitive processes that monitor and control speech. The cognitive control of language production is surprisingly understudied, Nozari says. “My hope is that my work will help return language to those who have lost it.”

When speech misfires

One branch of Nozari’s research focuses on how we catch ourselves when we misspeak. Traditionally, researchers believed that the brain mechanisms involved in understanding language (the comprehension system) were responsible for recognizing and correcting slips of the tongue. While Nozari acknowledges the role of comprehension in detecting speech errors, her work suggests the brain mechanisms involved in generating speech (the language production system) play a key role in the process. She and her colleagues showed black-and-white drawings of objects to people who suffered from aphasia, or language impairment, after a stroke. The researchers recorded whether the participants named the objects incorrectly and, if so, whether they caught and corrected their mistakes. They found that each participant’s ability to detect errors in his or her speech was better predicted by that person’s language production skills, as opposed to his or her comprehension skills ( Cognitive Psychology , Vol. 63, No. 1, 2011).

“There is no doubt that some part of self-monitoring happens through comprehension, but there are internal mechanisms within the production system itself that actually help catch and repair its own errors,” she says.

More recently, she and her colleague Rick Hanley, at the University of Essex in England, extended that theory to children. The research team tested 5- to 8-year-olds with the “moving animals” task, in which the children watched cartoons featuring nine familiar types of animals and described the events to the experimenter. Older children were better than younger children at catching and correcting their own semantic errors, such as calling a dog a cat.

Nozari, Hanley and their team also measured the maturity of each child’s language production system using a separate picture-naming task that required the child to identify the objects in a series of black-and-white drawings. By tallying the kids’ semantic errors (those related to meaning) and phonological errors (those related to sound), the researchers were able to estimate the strength of each child’s language production system using computational modeling. In particular, they showed that this strength was a key predictor in how well the children detected their errors in the moving animals task. This finding mirrored what Nozari and her colleagues found in individuals with aphasia, adding support to the theory that the language production system has its own built-in ability to catch verbal slipups, in children as well as adults ( Journal of Experimental Child Psychology , Vol. 142, No. 1, 2016).

More recently, Nozari’s lab has begun to explore what happens after monitoring, specifically looking at how monitoring processes may help regulate and optimize speech production processes. So far, their work suggests that cognitive control processes, such as inhibitory control, play a key role in our ability to produce fluent and (mostly) error-free language, Nozari says.

A wolf in sheep's clothing

Nozari can pinpoint the moment she first became interested in speech errors. After receiving a medical degree from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences in her native Iran in 2005, she went to London to study people with Alzheimer’s disease. In a routine screening test for dementia, one of her research participants was shown a picture of a sheep and asked to name the object. First, he said “wolf.” He tried again: “steep.” Then, “sleep.”

“I was fascinated that these were not just random errors,” Nozari recalls. “‘Wolf’ is related to ‘sheep’ in meaning, ‘steep’ is related in sound, and ‘sleep’ in both meaning and sound. I was blown away by this phenomenon, and I started reading all about language.”

Her research on the topic led her to the work of cognitive psychologist Gary Dell, PhD, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who later became her PhD mentor. In 2014, she joined the faculty at Johns Hopkins, where she studies language production in healthy adults and children as well as older adults who have language deficits following a stroke.

These stroke victims are motivational for Nozari as she studies the monitoring and control processes that allow people to produce and understand language. She hopes her research will lead to new ways to restore language to those who have lost it. “One of the most rewarding parts of my job is working with participants with brain damage,” she says. “There is nothing more inspiring than seeing the effort and hard work they put into regaining lost function after a stroke.”

Much of Nozari’s research involves participants recruited from the Snyder Center for Aphasia Life Enhancement, an aphasia support and community center in Baltimore. In one project with those participants, she and her colleagues took a fresh look at how to reteach words to people after a stroke. Traditionally, these patients are taught words organized in semantic themes—learning fruits in one session, animal names in another. But all of us, with or without aphasia, are more inclined to mix up words that are similar to one another, Nozari says. “If you make a slip of the tongue, you’re more likely to confuse a fruit with another fruit than you are to confuse a fruit with an animal.” Nozari predicted that language therapy arranged by semantic themes might actually be less effective than therapy that retaught words in semantically unrelated blocks.

To test that idea, she and her colleagues performed a small pilot study with two people who had post-stroke aphasia. Each participated in six training sessions to relearn object names, with the words arranged within semantic groups (such as a block of fruit names) or in semantically unrelated groups. While grouping words by theme helped one participant remember them better in the short term, both participants had better long-term retention of the words they learned in unrelated groups. Nozari and her colleagues presented the results at the 2017 annual meeting of the Academy of Aphasia.

The findings could also have implications for second-language education. In one study being prepared for publication, Nozari and former graduate student Bonnie Breining, PhD, and their Johns Hopkins colleague Brenda Rapp, PhD, taught neurotypical adults an artificial language. They showed that participants were better at learning new labels for objects if they were trained in semantically unrelated blocks.

More recently, Nozari and her lab manager Jessa Sahl are completing a version of the language training experiment among Baltimore schoolchildren. Sahl taught 7- and 8-year-olds French vocabulary words, arranged in related or unrelated blocks, for several weeks. She revisited the students to test their recall of the words three weeks and six weeks later.

So far, the results suggest that children, too, learn words better when taught in unrelated groupings, Nozari says.

“It’s harder to learn something when it is presented along with similar things. Sometimes difficulty in learning can be a good thing because you put more effort into learning. But difficulty is undesirable if you cannot overcome it at the time of learning.”

While these findings are preliminary, Nozari hopes such research could point to ways to improve language instruction, leading to better learning outcomes for both students and people with language deficits.

Becoming a mentor

Nozari’s appointment is in the medical school’s neurology department, which doesn’t have a dedicated PhD program. Though she typically hosts a postdoctoral fellow and occasionally co-mentors graduate students from the department of cognitive science, most of her team includes undergraduate students and paid research assistants, who typically have bachelor’s or master’s degrees. She pays those assistants with help from both internal university funding and grants from sources such as the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Nozari embraces a direct approach to helping her students set deadlines and establish schedules. “It’s often hard for young students to get a grip on how to manage their time, while still doing quality work,” she says.

When it comes to her mentees’ research interests, though, she’s relatively hands off. Her students and research assistants often pursue projects of their own, as long as they fit into the theme of the lab. “I really believe students have to choose their direction,” she says. “I can give them some help, I can nudge them, but ultimately they have to come up with what they want to do, or they will not have vested interest in the research,” she says.

While most of Nozari’s work to date has focused on spoken language, she’s excited about the many possible directions her research can go. In the last couple of years, she’s collaborated with colleagues such as Rapp who have expertise in other modalities of language production, such as written language. Svetlana Pinet, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab, has a background studying the cognitive mechanisms at play when people type words rather than speak them. “Our backgrounds all touch on language production, so we can all understand each other and contribute,” says research assistant Chris Hepner. “But it’s a diverse enough group that we can bring different perspectives to the table.”

Going forward, Nozari hopes her team’s work will encourage other psychologists and scientists to see human language in a new light. “There has sometimes been a tendency to view language as so special that it is somehow disconnected from the rest of cognition,” she says. “The goal of a number of psycholinguists, including myself, is to situate language within the broader picture of cognition.”

“Lab Work” illuminates the work psychologists are doing in research labs nationwide. To read previous installments, go to www.apa.org/monitor/digital and search for “Lab Work.”

Research foci

The Language Production and Executive Control Lab is exploring:

- Cognitive architecture of the language system

- Executive control in language production

- Monitoring and error detection in language production

- Language impairment (aphasia) and rehabilitation

Further reading

Monitoring and Control in Language Production Nozari, N., & Novick, J. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 2017

Cognitive Control During Selection and Repair in Word Production Nozari, N., Freund, M., et al. Language, Cognition & Neuroscience , 2016

Conflict-Based Regulation of Control in Language Production Freund, M., Gordon B., & Nozari, N. Proceedings of the 38th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society , Papafragou, A., Grodner, D., Mirman, D., & Trueswell, J.C. (Eds.), 2016

Investigating the Origin of Nonfluency in Aphasia: A Path Modeling Approach to Neuropsychology Nozari, N., & Faroqi-Shah, Y. Cortex, 2017

Speech Sound (Articulation) Disorders

What is articulation.

Articulation is the process of making speech sounds by moving the tongue, lips, jaw, and soft palate . Children learn speech by imitating the sounds they hear as you talk about what you are doing during the day, sing songs, and read books to them.

Speech sound development

Children begin developing speech as an infant. By 6 months of age, babies coo and play with their voices, making sounds like "oo,” “da,” “ma,” and “goo." As babies grow, they begin to babble, making more consonants like "b" and "k" with different vowel sounds.

Although children begin to develop speech as infants, they do not learn to make all speech sounds at one time. Your child will continue to imitate sounds and word shapes. These imitations will turn into natural, unplanned speech.

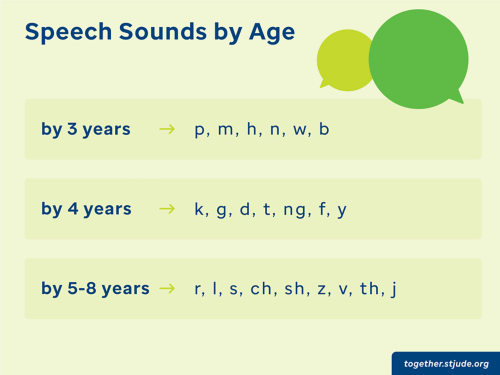

Every sound has a different, but predictable, range of ages for when the child should make the sound correctly.

General articulation milestones:

- By age 3, speech should be understandable about 80 percent of the time.

- By age 4, speech should be understandable almost all the time, although there may still be sound errors.

- By age 8, children should be able to make all of the sounds of the English language correctly.

Articulation errors are a normal part of speech development. Most children will make mistakes as they learn to say new words. Not all sound replacements and omissions are considered speech errors. Instead, they may be related to a dialect or accent.

The chart below gives age ranges for when children learn to make certain speech sounds.

Speech Sounds by Age

These are general guidelines for speech sound development. Talk with a speech language pathologist or other health care provider if you have concerns about your child’s speech.

Articulation delays and disorders

An articulation delay or disorder happens when errors continue past a certain age. These errors can occur at the beginning, middle, or end of a word. The 3 most common articulation errors are:

- Replacing one sound for another, like “bacuum” for “vacuum.”

- Omitting a sound, like “bue” for “blue.”

- Distorting a sound is when you recognize the sound but it sounds off. A lisp is a distortion of the “s” sound and is caused when the tongue sticks out past the teeth.

Causes of articulation delays and disorders

For many children, the causes of speech sound disorders are not known. Your child may not learn how to make the sounds correctly or may not learn the rules of speech on their own. Physical problems can also affect articulation. These physical problems include:

- Illnesses that last a long time. Being in a hospital or having a serious illness may reduce the normal activities and interactions that help children learn speech and language.

- Hearing loss. Speech is learned by listening. Hearing loss and ear problems such as frequent ear infections can slow down speech sound development in young children.

- Brain tumors. Tumors may affect the speech centers of the brain. They also can weaken muscles of the lips, palate, tongue, or vocal cords.

- Structural differences. The physical structure of the jaw, tongue, lips or palate can affect articulation. Structural differences due to injury or birth defects such as cleft lip and palate can lead to speech delays or disorders.

- Developmental or neurological disorders. Disorders such as stroke, cerebral palsy, autism, or brain injury can cause speech sound problems.

- Cannot be understood; they may get frustrated or act out because they cannot express themselves.

- Avoid situations where they need to speak.

- Get embarrassed or worried about how they sound or because others make fun of the way they speak.

What you can do to help

- Talk to your child during playtime. This is a chance to make talking fun and model correct speech sounds.

- When talking, face your child and position yourself near eye level.

Mother and toddler playing, face to face, eye level

- Do not interrupt or constantly correct your child.

- Do not reinforce errors by imitating them. Instead, model the correct way to make the sound. For example, if your child says, “That’s a wellow duck,” you say, “Yes, that’s a yellow duck. A yellow baby duck. The sun is yellow, too.”

- Praise your child for saying the sound correctly or give encouragement for trying.

- Read to your child. Use reading to surround your child with the targeted sound. For example, read Goodnight Moon if the child is working on the /g/ sound.

- Use meals, bath time, bedtime, playtime, and other daily routines to work on speech. These activities can be great learning moments.

If you have concerns about your child’s speech, talk to your doctor. It is important to identify and treat any physical conditions that may be contributing to articulation delays.

A speech language pathologist can help assess whether your child has an articulation disorder and develop a speech therapy plan.

- Articulation is the process of making speech sounds. Articulation errors are a normal part of speech development.

- Speech sound errors or articulation disorders can happen for a variety of reasons. Often, the cause is not known.

- There are ways you can help your child with speech sounds.

- Your doctor may refer you to a speech language pathologist for speech therapy to help with an articulation delay or disorder.

— Reviewed: August 2022

Speech Sound Errors

Speech Sound Errors: Speech production difficulties are the most common form of communication impairment school-based speech pathologists are likely to encounter when working in schools. This page will briefly focus on the two most commonly diagnosed and treated speech disorders: articulation disorders and phonological disorders.

Articulation Disorders

Children who present with articulation disorders generally mispronounce sounds, which effects their speech intelligibility. Articulation disorders have a motor production basis, which results in difficulty with particular phonemes, known as misarticulations. The most common sound misarticulations are omissions , distortions and substitutions . Omissions: Omissions of phonemes is when a child doesn't produce a sound in a word. An example of an omission would be a child who says 'ool' for 'pool.' Substitutions: A very common speech sound error is the substitution. An example is 'thun' for 'sun.' Distortions: Distortions are when a child uses a non-typical sound for a typically developing sound. One of the more common and difficult sound substitutions to treat is the lateral /s/, where the air escapes out of the side of the mouth during /s/ production, not over the center of the tongue. This results in a noisy or slushy quality to the /s/ sound.

Phonological Disorders

A phonological speech disorder is present in the absence of structural or neurological problems and generally causes speech to become largely unintelligible to unfamiliar listeners. For instance, if a child with a phonological disorder was to say, 'On the weekend, I went to the beach,' the sentence may sound like 'On a eet en, I ent oo a bee.' In the above example, close family members who are used to their child's speech sound errors can often understand the content of their child's message. However, people who are unfamiliar with a child's speech impairment will mostly have no clue as to what the child is talking about. When young children attempt to imitate and learn adult speech they will use certain processes to help simplify some speech sounds. Children do this because their speech patterns are not yet at a mature level, therefore they will often substitute easier sounds for more difficult sounds. These sound substitutions are known as phonological processes . Below are several of the more common processes that children will use when attempting to learn adult type speech. If you're a school teacher or pre-school teacher you may have met children who produce these processes. Cluster Reduction: This process occurs on words which feature consonant sounds that are grouped together. For instance, the words snake and snail both feature the consonant cluster sn . In a cluster reduction snake and snail are commonly misarticulated as nake and nail . The /s/ at the beginning of the word is deleted. Final Consonant Deletion: As the process title suggests, the final consonant sound in a word is deleted. For instance the words sheep , duck and carrot may be produced as shee ..., du ... and carro ... When a child has final consonant deletion he or she tends to delete just about all final consonants. So the sentence, 'The horse ate the carrot and the duck went for a swim,' may be presented by the child as 'The hor.. a... the carro... an... the du... wen... for a swi...' Velar Fronting: Very common processes and speech sound errors seen in young boys and girls. Velar fronting occurs on production of the /k/ and /g/ phonemes. The /k/ and /g/ phonemes are made at the back of the mouth, when the tongue contacts the velum, which results in a blockage of the air stream. Children with velar fronting difficulty don't do this. Their tongue tip touches the front of the mouth to produce a /t/ or /d/. For instance, c art becomes t art , and g oat becomes d oat . Stopping: Fricative sounds (stream of air) are replaced by sounds that don't have a stream of air. That is, long windy sounds such as /sh/ or long hissing sounds such as /s/ are replaced by short sounds such as /t/ or /p/. So for instance, the word ship may be pronounced as pip , or tip , or even dip . Liquid Glides: A very common process where the liquid sounds /l/ and /r/ are replaced by /w/ or /y/. For instance, leaf becomes weaf or yeaf , and red becomes wed or yed . Liquid glides are later developing sounds and so are not really considered speech sound errors in younger children, but more as a natural process. For more information about Speech Sound Intervention click to the Speech Sound Intervention page.

Eliciting Speech Sounds

Please click on the links to access information on how to elicit speech sounds for common speech sound errors. Eliciting the /s/ Sound Eliciting the /sh/ Sound Eliciting the /k/ Sound Eliciting the /f/ Sound Eliciting the /l/ Sound

Other important speech sound intervention pages

Click to learn about Traditional Articulation Therapy

Click to learn about Minimal Pairs Intervention (linguistic method)

Click to learn about Multiple Oppositions Intervention (linguistic method)

Click to learn about Empty Set Intervention (linguistic method)

Click to download the instruction and components for the Turbo Card Board Game (Handy game to be used either during speech intervention or as a reward activity)

Speech Intervention Sequence: Comprehensive speech therapy sequence method using traditional articulation intervention techniques

References Van Riper, C. & Erickson, R.L. (1996) Speech Correction: An Introduction to Speech Pathology and Audiology. Allyn & Bacon Williams, A.L. McLeod, S. & McCauley, R.J.(2010)Interventions for Speech Sound Disorders in Children. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Content Last Updated 14/09/2020

| Facebook Twitter Pinterest Tumblr Reddit WhatsApp |

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

- Language Blog

Science of Learning

- Why your child cannot read

- Science of learning and teaching

- What is the Science of Reading?

- Rosenshine Principles for Classroom Practice

Language Intervention

- Inference Activities 2nd Edition

- Sentence Grammar Program

- Free Board Games

- WM Challenges

- WM Activities

- Board Games

- Language Therapy

- Language eBook

- Language program

- Inferencing

- Language skills

- Shared Reading

- Sentence Structure

- Sentence Builder

- Sentence Creator

- Free Activities

- Oral Language Program

- Best Resources

Information about Language

- Active Listening

- What is language?

- Language Disorder

- Working Memory

- Tips for Parents

- Advanced Lang

- Speech Intervention

- The Lateral S

- Minimal Pairs Theory

- Multiple Op

- What is Speech?

- Speech Errors

- Speech Structures

- Simple View of Reading

- Synthetic Phonics Resources

- Sounds to Graph

- Phonol Intervention

- Inference Program

- Inference-Reading

- Vocab Activities

- Vocabulary Comp

- Comprehension

- Dyslexia Defined

- Phonological A

Social Language

- Asperger's Syn

- Pragmatic lang

- Figurative lang

Book Analysis

Best books information.

- Book Activities

- Benefits...

- 1st Grade Books

- 3rd Grade Books

- 6th Grade Books

Website Information

- Research Articles

- Privacy Policy

Information for Teachers and Speechies

- Teacher Tips

- Classroom lang

- Language Techniques

- Crafting Connections

- Parent Survey

- Teaching Literacy

- Secondary School

- Language literacy Inter

- Reading Difficulties

- Writing Tips

- Cognitive load theory

The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne

- My RCH Portal

- Health Professionals

- Patients and Families

- Departments and Services

- Health Professionals

- Departments and Services

- Patients and Families

- Research

Kids Health Information

- About Kids Health Info

- Fact sheets

- Translated fact sheets

- RCH TV for kids

- Kids Health Info podcast

- First aid training

In this section

Speech problems – articulation and phonological disorders

Articulation and phonology ( fon-ol-oji ) refer to the way sound is produced. A child with an articulation disorder has problems forming speech sounds properly. A child with a phonological disorder can produce the sounds correctly, but may use them in the wrong place.

When young children are growing, they develop speech sounds in a predictable order. It is normal for young children to make speech errors as their language develops; however, children with an articulation or phonological disorder will be difficult to understand when other children their age are already speaking clearly.

A qualified speech pathologist should assess your child if there are any concerns about the quality of the sounds they make, the way they talk, or their ability to be understood.

Signs and symptoms of articulation and phonological disorders

Articulation disorders.

Articulation refers to making sounds. The production of sounds involves the coordinated movements of the lips, tongue, teeth, palate (top of the mouth) and respiratory system (lungs). There are also many different nerves and muscles used for speech.

If your child has an articulation disorder, they:

- have problems making sounds and forming particular speech sounds properly (e.g. they may lisp, so that s sounds like th )

- may not be able to produce a particular sound (e.g. they can't make the r sound, and say 'wabbit' instead of 'rabbit').

Phonological disorders

Phonology refers to the pattern in which sounds are put together to make words.

If your child has a phonological disorder, they:

- are able to make the sounds correctly, but they may use it in the wrong position in a word, or in the wrong word, e.g. a child may use the d sound instead of the g sound, and so they say 'doe' instead of 'go'

- make mistakes with the particular sounds in words, e.g. they can say k in 'kite' but with certain words, will leave it out e.g. 'lie' instead of 'like'.

Phonological disorders and phonemic awareness disorders (the understanding of sounds and sound rules in words) have been linked to ongoing problems with language and literacy. It is therefore important to make sure that your child gets the most appropriate treatment.

It can be much more difficult to understand children with phonological disorders compared to children with pure articulation disorders. Children with phonological disorders often have problems with many different sounds, not just one.

When to see a doctor

If you (or anyone else in regular contact with your child, such as their teacher) have any concerns about your child's speech, ask your GP or paediatrician to arrange an assessment with a speech pathologist. You can also arrange to see a speech pathologist directly; however, the fees may be higher.

A qualified speech pathologist should assess your child if there are any concerns about their speech. A speech pathologist can identify the cause, and plan treatment with your child and family. Treatment may include regular appointments and exercises for you to do with your child at home.

With appropriate speech therapy, many children with articulation or phonological disorders will have significant improvement in their speech.

Brain injuries

Articulation or phonological difficulties are generally not a direct result of brain injury. Children with an acquired brain injury may have different difficulties with their speech patterns. These are generally caused by dyspraxia or dysarthria. Some children with acquired brain injuries may also have difficulties with literacy and language. See our fact sheets Dysarthria and Dyspraxia .

Key points to remember

- Articulation and phonology refer to the making of speech sounds.

- Children with phonological disorders or phonemic awareness disorders may have ongoing problems with language and literacy.

- If there are any concerns about your child's speech, ask your GP to arrange an assessment with a qualified speech pathologist.

- With appropriate speech therapy, many children with articulation or phonological disorders will have a big improvement in their speech.

For more information

- Kids Health Info fact sheet: Verbal dyspraxia

- Kids Health Info fact sheet: Word-finding difficulties

- Speech Pathology Australia: Resources for the public

- See your GP or speech pathologist.

Common questions our doctors are asked

Could my child just catch up eventually and grow out of an articulation/phonological disorder?

Some speech disorders can persist well into teenage and adult life. When a person is older, it is much more difficult to correct these problems. Most children with a diagnosed articulation/phonological disorder will need speech therapy.

What causes articulation and phonological disorders?

In most children, there is no known cause for articulation and phonological disorders. In some, the disorder may be due to a structural problem or from imitating behaviours and the creation of bad habits. Regardless of the cause, your child's speech therapist will be able to assist with the recommended treatment.

Developed by The Royal Children's Hospital Paediatric Rehabilitation Service and Speech Pathology department. Adapted with permission from a fact sheet from the Brain Injury Service at Westmead Children's Hospital. We acknowledge the input of RCH consumers and carers.

Reviewed July 2018.

This information is awaiting routine review. Please always seek the most recent advice from a registered and practising clinician.

Kids Health Info is supported by The Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation. To donate, visit www.rchfoundation.org.au .

This information is intended to support, not replace, discussion with your doctor or healthcare professionals. The authors of these consumer health information handouts have made a considerable effort to ensure the information is accurate, up to date and easy to understand. The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne accepts no responsibility for any inaccuracies, information perceived as misleading, or the success of any treatment regimen detailed in these handouts. Information contained in the handouts is updated regularly and therefore you should always check you are referring to the most recent version of the handout. The onus is on you, the user, to ensure that you have downloaded the most up-to-date version of a consumer health information handout.

What’s Right and What’s Wrong with Speech Sounds

- First Online: 04 May 2022

Cite this chapter

- Sheila E. Blumstein 2

489 Accesses