- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Academic CV (Curriculum Vitae) for Research: CV Examples

What is an academic CV (or research CV)?

An academic CV or “curriculum vitae” is a full synopsis (usually around two to three pages) of your educational and academic background. In addition to college and university transcripts, the personal statement or statement of purpose , and the cover letter, postgraduate candidates need to submit an academic CV when applying for research, teaching, and other faculty positions at universities and research institutions.

Writing an academic CV (also referred to as a “research CV” or “academic resume”) is a bit different than writing a professional resume. It focuses on your academic experience and qualifications for the position—although relevant work experience can still be included if the position calls for it.

What’s the difference between a CV and a resume?

While both CVs and resumes summarize your major activities and achievements, a resume is more heavily focused on professional achievements and work history. An academic CV, on the other hand, highlights academic accomplishments and summarizes your educational experience, academic background and related information.

Think of a CV as basically a longer and more academic version of a resume. It details your academic history, research interests, relevant work experience, publications, honors/awards, accomplishments, etc. For grad schools, the CV is a quick indicator of how extensive your background is in the field and how much academic potential you have. Ultimately, grad schools use your academic resume to gauge how successful you’re likely to be as a grad student.

Do I need an academic CV for graduate school?

Like personal statements, CVs are a common grad school application document (though not all programs require them). An academic CV serves the same basic purpose as a regular CV: to secure you the job you want—in this case, the position of “grad student.” Essentially, the CV is a sales pitch to grad schools, and you’re selling yourself !

In addition to your college transcripts, GRE scores, and personal statement or statement of purpose , graduate schools often require applicants submit an academic CV. The rules for composing a CV for a Master’s or doctoral application are slightly different than those for a standard job application. Let’s take a closer look.

Academic CV Format Guidelines

No matter how compelling the content of your CV might be, it must still be clear and easy for graduate admissions committee members to understand. Keep these formatting and organization tips in mind when composing and revising your CV:

- Whatever formatting choices you make (e.g., indentation, font and text size, spacing, grammar), keep it consistent throughout the document.

- Use bolding, italics, underlining, and capitalized words to highlight key information.

- Use reverse chronological order to list your experiences within the sections.

- Include the most important information to the top and left of each entry and place associated dates to the right.

- Include page numbers on each page followed by your last name as a header or footer.

- Use academic verbs and terms in bulleted lists; vary your language and do not repeat the same terms. (See our list of best verbs for CVs and resumes )

How long should a CV be?

While resumes should be concise and are usually limited to one or two pages, an academic CV isn’t restricted by word count or number of pages. Because academic CVs are submitted for careers in research and academia, they have all of the sections and content of a professional CV, but they also require additional information about publications, grants, teaching positions, research, conferences, etc.

It is difficult to shorten the length without shortening the number of CV sections you include. Because the scope and depth of candidates’ academic careers vary greatly, academic CVs that are as short as two pages or as long as five pages will likely not surprise graduate admissions faculty.

How to Write an Academic CV

Before we look at academic CV examples, let’s discuss the main sections of the CV and how you can go about writing your CV from scratch. Take a look at the sections of the academic CV and read about which information to include and where to put each CV section. For academic CV examples, see the section that follows this one.

Academic CV Sections to Include (with Examples)

A strong academic CV should include the following sections, starting from the top of the list and moving through the bottom. This is the basic Academic CV structure, but some of the subsections (such as research publications and academic awards) can be rearranged to highlight your specific strengths and achievements.

- Contact Information

- Research Objective or Personal Profile

- Education Section

- Professional Appointments

- Research Publications

- Awards and Honors

- Grants and Fellowships

- Conferences Attended

- Teaching Experience

- Research Experience

- Additional Activities

- Languages and Skills

Now let’s go through each section of your academic CV to see what information to include in detail.

1. Contact Information

Your academic curriculum vitae must include your full contact information, including the following:

- Professional title and affiliation (if applicable)

- Institutional address (if you are currently registered as a student)

- Your home address

- Your email address

- Your telephone number

- LinkedIn profile or other professional profile links (if applicable)

In more business-related fields or industries, adding your LinkedIn profile in your contact information section is recommended to give reviewers a more holistic understanding of your academic and professional profile.

Check out our article on how to use your LinkedIn profile to attract employers .

2. Research Objective or Personal Profile

A research objective for an academic CV is a concise paragraph (or long sentence) detailing your specific research plans and goals.

A personal profile gives summarizes your academic background and crowning achievements.

Should you choose a research objective or a personal profile?

If you are writing a research CV, include a research objective. For example, indicate that you are applying to graduate research programs or seeking research grants for your project or study

A research objective will catch the graduate admission committee’s attention and make them want to take a closer look at you as a candidate.

Academic CV research objective example for PhD application

MA student in Sociology and Gender Studies at North American University who made the President’s List for for six consecutive semesters seeking to use a semester-long research internship to enter into postgraduate research on the Impetus for Religious In-groups in Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century.

Note that the candidate includes details about their academic field, their specific scholastic achievements (including an internship), and a specific topic of study. This level of detail shows graduate committees that you are a candidate who is fully prepared for the rigors of grad school life.

While an academic CV research objective encapsulates your research objective, a CV personal profile should summarize your personal statement or grad school statement of purpose .

Academic CV personal profile example for a post-doctoral university position

Proven excellence in the development of a strong rapport with undergraduate students, colleagues, and administrators as a lecturer at a major research university. Exhibits expertise in the creation and implementation of lifelong learning programs and the personalized development of strategies and activities to propel learning in Higher Education, specifically in the field of Education. Experienced lecturer, inspirational tutor, and focused researcher with a knack for recognizing and encouraging growth in individuals. Has completed a Master’s and PhD in Sociology and Education with a BA in Educational Administration.

What makes this CV personal profile example so compelling? Again, the details included about the applicant’s academic history and achievements make the reader take note and provide concrete examples of success, proving the candidate’s academic acumen and verifiable achievements.

3. Education Section

If you are applying to an academic position, the Education section is the most essential part of your academic CV.

List your postsecondary degrees in reverse chronological order . Begin with your most recent education (whether or not you have received a degree at the time of application), follow it with your previous education/degree, and then list the ones before these.

Include the following educational details:

- Year of completion or expected completion (do not include starting dates)

- Type of Degree

- Any minor degrees (if applicable)

- Your department and institution

- Your honors and awards

- Dissertation/Thesis Title and Advisor (if applicable)

Because this is arguably the most important academic CV section, make sure that all of the information is completely accurate and that you have not left out any details that highlight your skills as a student.

4. Professional Appointments

Following the education section, list your employment/professional positions on your academic CV. These should be positions related to academia rather than previous jobs or positions you held in the private section (whether it be a chef or a CEO). These appointments are typically tenure-track positions, not ad hoc and adjunct professor gigs, nor TA (teacher assistant) experience. You should instead label this kind of experience under “Teaching Experience,” which we discuss further down the list.

List the following information for each entry in your “Professional Appointments” section:

- Institution (university/college name)

- Department

- Your professional title

- Dates employed (include beginning and end dates)

- Duties in this position

5. Research Publications

Divide your publications into two distinct sections: peer-reviewed publications and other publications. List peer-reviewed publications first, as these tend to carry more weight in academia. Use a subheading to distinguish these sections for the reader and make your CV details easier to understand.

Within each subsection, further divide your publications in the following order:

- Book chapters

- Peer-reviewed journal articles

- Contributions to edited volumes equivalent to peer-reviewed journals

All of your other research publications should be put into a subcategory titled “Other Publications.” This includes all documents published by a third party that did not receive peer review, whether it is an academic journal, a science magazine, a website, or any other publishing platform.

Tip: When listing your publications, choose one academic formatting style ( MLA style , Chicago style , APA style , etc.) and apply it throughout your academic CV. Unsure which formatting style to use? Check the website of the school you are applying to and see what citation style they use.

6. Awards and Honors

This section allows you to show off how your skills and achievements were officially acknowledged. List all academic honors and awards you have received in reverse chronological order, just like the education and professional appointments sections. Include the name of the award, which year you received it, and the institution that awarded it to you.

Should you include how much money you were awarded? While this is not recommended for most academic fields (including humanities and social sciences), it is more common for business or STEM fields.

7. Fellowships and Grants

It is important to include fellowships and grants you received because it evidences that your research has been novel and valuable enough to attract funding from institutions or third parties.

Just like with awards and honors, list your grants and fellowships in reverse chronological order. Enter the years your fellowship or grant spanned and the name of the institution or entity providing the funding. Whether you disclose the specific dollar amount of funding you received depends on your field of study, just as with awards and honors.

8. Conferences Attended

Involvement in academic conferences shows admissions committees that you are already an active member of the research community. List the academic conferences in which you took part and divide this section into three subsections:

- Invited talks —conferences you presented at other institutions to which you received an invitation

- Campus talks —lectures you gave on your own institution’s campus

- Conference participation —conferences you participated in (attended) but gave no lecture

9. Teaching Experience

The “Teaching Experience” section is distinct from the “Professional Appointments” section discussed above. In the Teaching Experience CV section, list any courses you taught as a TA (teacher’s assistant) you have taught. If you taught fewer than ten courses, list all of them out. Included the name of the institution, your department, your specific teaching role, and the dates you taught in this position.

If you have a long tenure as an academic scholar and your academic CV Appointments section strongly highlights your strengths and achievements, in the Teaching Experience sections you could list only the institutions at which you were a TA. Since it is likely that you will be teaching, lecturing, or mentoring undergraduates and other research students in your postgraduate role, this section is helpful in making you stand out from other graduate, doctoral, or postdoctoral candidates.

10. Research Experience

In the “Research Experience” section of your CV, list all of the academic research posts at which you served. As with the other CV sections, enter these positions in reverse chronological order.

If you have significant experience (and your academic CV is filling up), you might want to limit research and lab positions to only the most pertinent to the research position to which you are applying. Include the following research positions:

- Full-time Researcher

- Research Associate

- Research Assistant

For an academic or research CV, if you do not have much research experience, include all research projects in which you participated–even the research projects with the smallest roles, budget, length, or scope.

11. Additional Activities

If you have any other activities, distinctions, positions, etc. that do not fit into the above academic CV sections, include them here.

The following items might fit in the “Additional Activities” section:

- Extracurriculars (clubs, societies, sports teams, etc.)

- Jobs unrelated to your academic career

- Service to profession

- Media coverage

- Volunteer work

12. Languages and Skills

Many non-academic professional job positions require unique skillsets to succeed. The same can be true with academic and research positions at universities, especially when you speak a language that might come in handy with the specific area of study or with the other researchers you are likely to be working alongside.

Include all the languages in which you are proficient enough to read and understand academic texts. Qualify your proficiency level with the following terms and phrases:

- IntermediateNative/bilingual in Language

- Can read Language with a dictionary

- Advanced use of Language

- Fully proficient in Language

- Native fluency in Language

- Native/Bilingual Language speaker

If you only have a basic comprehension of a language (or if you simply minored in it a decade ago but never really used it), omit these from this section.

Including skills on an academic CV is optional and MIGHT appear somewhat amateur if it is not a skill that is difficult and would likely contribute to your competency in your research position. In general, include a skill only if you are in a scientific or technical field (STEM fields) and if they realistically make you a better candidate.

13. References

The final section of your academic CV is the “References” section. Only include references from individuals who know you well and have first-hand experience working with you, either in the capacity of a manager, instructor, or professor, or as a colleague who can attest to your character and how well you worked in that position. Avoid using personal references and never use family members or acquaintances–unless they can somehow attest to your strength as an academic.

List your references in the order of their importance or ability to back up your candidacy. In other words, list the referrers you would want the admissions faculty to contact first and who would give you a shining review.

Include the following in this order:

- Full name and academic title

- Physical mailing address

- Telephone number

- Email address

Academic CV Examples by Section

Now that you have a template for what to include in your academic CV sections, let’s look at some examples of academic CV sections with actual applicant information included. Remember that the best CVs are those that clearly state the applicant’s qualifications, skills, and achievements. Let’s go through the CV section-by-section to see how best to highlight these elements of your academic profile. Note that although this example CV does not include EVERY section detailed above, this doesn’t mean that YOU shouldn’t include any of those sections if you have the experiences to fill them in.

CV Example: Personal Details (Basic)

Write your full name, home address, phone number, and email address. Include this information at the top of the first page, either in the center of the page or aligned left.

- Tip: Use a larger font size and put the text in bold to make this info stand out.

CV Example: Profile Summary (Optional)

This applicant uses an academic research profile summary that outlines their personal details and describes core qualifications and interests in a specific research topic. Remember that the aim of this section is to entice admissions officials into reading through your entire CV.

- Tip: Include only skills, experience, and what most drives you in your academic and career goals.

CV Example: Education Section (Basic)

This applicant’s academic degrees are listed in reverse chronological order, starting with those that are currently in progress and recently completed and moving backward in time to their undergraduate degrees and institutions.

- Include the name of the institution; city, state, and country (if different from the institution to which you are applying); degree type and major; and month/year the degree was or will be awarded.

- Provide details such as the title of your thesis/dissertation and your advisor, if applicable.

- Tip: Provide more details about more recent degrees and fewer details for older degrees.

CV Example: Relevant Experience (Basic)

List professional positions that highlight your skills and qualifications. When including details about non-academic jobs you have held, be sure that they relate to your academic career in some way. Group experiences into relevant categories if you have multiple elements to include in one category (e.g., “Research,” “Teaching,” and “Managerial”). For each position, be sure to:

- Include position title; the name of organization or company; city, state, and country (if different from the institution to which you are applying); and dates you held the position

- Use bullet points for each relevant duty/activity and accomplishment

- Tip: For bulleted content, use strong CV words , vary your vocabulary, and write in the active voice; lead with the verbs and write in phrases rather than in complete sentences.

CV Example: Special Qualifications or Skills (Optional)

Summarize skills and strengths relevant to the position and/or area of study if they are relevant and important to your academic discipline. Remember that you should not include any skills that are not central to the competencies of the position, as these can make you appear unprofessional.

CV Example: Publications (Basic)

Include a chronological (not alphabetical) list of any books, journal articles, chapters, research reports, pamphlets, or any other publication you have authored or co-authored. This sample CV does not segment the publications by “peer-reviewed” and “non-peer-reviewed,” but this could simply be because they do not have many publications to list. Keep in mind that your CV format and overall design and readability are also important factors in creating a strong curriculum vitae, so you might opt for a more streamlined layout if needed.

- Use bibliographic citations for each work in the format appropriate for your particular field of study.

- Tip: If you have not officially authored or co-authored any text publications, include studies you assisted in or any online articles you have written or contributed to that are related to your discipline or that are academic in nature. Including any relevant work in this section shows the faculty members that you are interested in your field of study, even if you haven’t had an opportunity to publish work yet.

CV Example: Conferences Attended (Basic)

Include any presentations you have been involved in, whether you were the presenter or contributed to the visual work (such as posters and slides), or simply attended as an invitee. See the CV template guide in the first section of this article for how to list conference participation for more seasoned researchers.

- Give the title of the presentation, the name of the conference or event, and the location and date.

- Briefly describe the content of your presentation.

- Tip: Use style formatting appropriate to your field of study to cite the conference (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.)

CV Example: Honors and Awards (Basic)

Honors and awards can include anything from university scholarships and grants, to teaching assistantships and fellowships, to inclusion on the Dean’s list for having a stellar GPA. As with other sections, use your discretion and choose the achievements that best highlight you as a candidate for the academic position.

- Include the names of the honors and official recognition and the date that you received them.

- Tip: Place these in order of importance, not necessarily in chronological order.

CV Example: Professional/Institutional Service (Optional)

List the professional and institutional offices you have held, student groups you have led or managed, committees you have been involved with, or extra academic projects you have participated in.

- Tip: Showing your involvement in campus life, however minor, can greatly strengthen your CV. It shows the graduate faculty that you not only contribute to the academic integrity of the institution but that you also enrich the life of the campus and community.

CV Example: Certifications and Professional Associations (Optional)

Include any membership in professional organizations (national, state, or local). This can include nominal participation as a student, not only as a professional member.

CV Example: Community Involvement and Volunteer Work (Optional)

Include any volunteer work or outreach to community organizations, including work with churches, schools, shelters, non-profits, and other service organizations. As with institutional service, showing community involvement demonstrates your integrity and willingness to go the extra mile—a very important quality in a postgraduate student or faculty member.

While the CV template guide above suggests including these activities in a section titled “Additional Activities,” if you have several instances of volunteer work or other community involvement, creating a separate heading will help catch the eye of the admissions reviewer.

CV Example: References Section (Basic)

References are usually listed in the final section of an academic CV. Include 3-5 professional or academic references who can vouch for your ability and qualifications and provide evidence of these characteristics.

- Write the name of the reference, professional title, affiliation, and contact information (phone and email are sufficient). You do not need to write these in alphabetical order. Consider listing your references in order of relevance and impact.

CV Editing for Research Positions

After you finish drafting and revising your academic CV, you still need to ensure that your language is clear, compelling, and accurate and that it doesn’t have any errors in grammar, spelling, or punctuation.

A good academic CV typically goes through at least three or four rounds of revision before it is ready to send out to university department faculty. Be sure to have a peer or CV editing service check your CV or academic resume, and get cover letter editing and application essay editing for your longer admissions documents to ensure that there are no glaring errors or major room for improvement.

For professional editing services that are among the highest quality in the industry, send your CV and other application documents to Wordvice’s admissions editing services . Our professional proofreaders and editors will ensure that your hard work is reflected in your CV and help make your postgrad goals a reality.

Check out our full suite of professional proofreading and English editing services on the Wordvice homepage.

Unfortunately we don't fully support your browser. If you have the option to, please upgrade to a newer version or use Mozilla Firefox , Microsoft Edge , Google Chrome , or Safari 14 or newer. If you are unable to, and need support, please send us your feedback .

We'd appreciate your feedback. Tell us what you think! opens in new tab/window

Writing an effective academic CV

June 6, 2019 | 6 min read

By Elsevier Connect contributors

How to create a curriculum vitae that is compelling, well-organized and easy to read

A good CV showcases your skills and your academic and professional achievements concisely and effectively. It’s well-organized and easy to read while accurately representing your highest accomplishments.

Don't be shy about your achievements, but also remember to be honest about them. Do not exaggerate or lie!

Academic CVs differ from the CVs opens in new tab/window typically used by non-academics in industry because you need to present your research, various publications and awarded funding in addition to the other items contained in a non-academic CV.

Here are some tips. They are organized into categories that could be used to structure a CV. You do not need to follow this format, but you should address the categories covered here somewhere in your CV.

Tools you can use

If you’re looking to demonstrate the impact your research has had, PlumX Metrics are available in several of Elsevier’s products and services, giving you an overview of how specific papers have performed, including where they were mentioned in the media, how other researchers used them, and where they were mentioned on platforms from Twitter to Wikipedia.

You can also use Mendeley Careers to discover job opportunities based on the keywords and interests listed in your CV and the articles you’ve read in your Mendeley library.

If you’re looking for more specific guidance on how to take control of your career in research and academia, Elsevier’s Research Academy opens in new tab/window has entire sections dedicated to job search opens in new tab/window , career planning and career guidance.

General tips

Start by considering the length , structure and format of your CV.

2 pages is optimal for a non-academic CV, but research positions offer more flexibility on length

Include research-specific details that emphasize your suitability, like relevant publications, funding secured in your name, presentations and patents to the employer.

4 sides is a reasonable length. Academic recruiters may accept more if the additional information is relevant to the post.

Next, choose a structure for your CV.

Start with the main headings and sub-headings you will use.

In general, you should start by providing some brief personal details, then a brief career summary.

The first section of your CV should focus on your education, publications and research.

Also address: funding, awards and prizes, teaching roles, administrative experience, technical and professional skills and qualifications, professional affiliations or memberships, conference and seminar attendances and a list of references.

Dr. Sheba Agarwal-Jans talks about writing an academic CV for Elsevier’s Researcher Academy (free registration required). Watch here opens in new tab/window .

Use legible font types in a normal size (font size 11 or 12) with normal sized margins (such as 1 inch or 2.5 cm).

Bullet points can highlight important items and present your credentials concisely.

Keep a consistent style for headings and sub-headings and main text – do not use more than 2 font types.

Make smart but sparing use of

bold and italics. (Avoid underlining for emphasis; underlines are associated with hyperlinks.)

Be aware of spelling and grammar and ensure it is perfect. Re-read a few times after writing the CV. Spell check can be useful, though some suggestions will not be accurate or relevant.

Composing your CV

Personal details

Personal details include your name, address of residence, phone number(s) and professional email.

You might also include your visa status if relevant.

Career summary

Use about 5 to 7 sentences to summarize your expertise in your disciplines, years of expertise in these areas, noteworthy research findings, key achievements and publications.

Provide an overview of your education starting from your most recent academic degree obtained (reverse chronological order).

Include the names of the institutions, thesis or dissertation topics and type of degree obtained.

List your most reputed publications in ranking of type, such as books, book chapters, peer-reviewed journal articles, non-peer-reviewed articles, articles presented as prestigious conferences, forthcoming publications, reports, patents, and so forth.

Consider making an exhaustive list of all publications in an appendix.

Publications

Your research experiences, findings, the methods you use and your general research interests are critical to present in the first part of your CV.

Highlight key research findings and accomplishments.

Honors and awards

Indicate any prizes, awards, honors or other recognitions for your work with the year it occurred and the organization that granted the award.

The funding you have attracted for your research and work is recognition of the value of your research and efforts.

As with the honors and recognitions, be forthcoming with what you have obtained in terms of grants, scholarships and funds.

List your teaching experience, including the institutions, years you taught, the subjects you taught and the level of the courses.

Administrative experience

Administrative experience on a faculty or at a research institute should be noted.

This might include facilitating a newsletter, organizing events or other noteworthy activities at your institution or beyond.

Professional experience

Include any employment in industry that is recent (within the last 5 to 10 years) and relevant to your academic work.

Professional experience can explain any gaps in your academic work and demonstrate the diversity in your capabilities.

Other skills and qualifications

Highlight key skills and qualifications relevant to your research and academic work.

Technical and practical skills, certifications, languages and other potentially transferrable skills are relevant to mention in this section.

Professional affiliations and memberships

If you belong to any professional group or network related to your areas of expertise, you should mention them in this section.

Only list affiliations or memberships you have been active with within the last 5 years.

Keep this section short.

Attendance at conferences and seminars

List the most relevant conferences or seminars where you presented or participated on a panel within the last 5 to 7 years.

In an appendix, you can add an exhaustive list of conferences and seminars where you participated by giving a speech, presenting a paper or research, or took part in a discussion panel.

List at least three people who can provide a reference for your research, work and character. Check with them first to make sure the are comfortable recommending you and aware of the opportunities you are seeking.

Provide their names and complete contact information. They should all be academics and all people you have worked with.

Appendices enable you to keep the main content of your CV brief while still providing relevant detail.

Items to list in an appendix can include publications, short research statements or excerpts, conference or seminar participation, or something similar and relevant which you would like to provide more details about.

CVs are not only for job searching. You will need to update your CV regularly and adapt it for the various purposes:

Awards, fellowships

Grant applications

Public speaking

Contributor

Elsevier Connect contributors

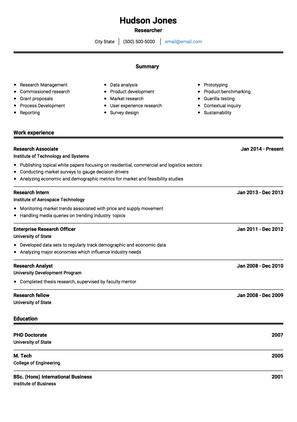

Research Scientist CV Example

Cv guidance.

- CV Template

- How to Format

- Personal Statements

- Related CVs

CV Tips for Research Scientists

- Highlight Your Education and Specialization : Clearly state your degrees, the institutions you attended, and your areas of specialization. If you have a PhD or post-doctoral experience, place this information prominently in your CV.

- Detail Your Research Achievements : Quantify your impact with specific metrics, such as the number of projects led, grants won, or publications in high-impact journals.

- Customize Your CV to the Role : Align your CV content with the job's requirements, emphasizing relevant experiences and skills. If the role requires expertise in a specific research method or technology, make sure this is clearly stated in your CV.

- Specify Your Technical Skills : List your proficiency in laboratory techniques, scientific software, or equipment relevant to your field. Also, mention any experience with data analysis or statistical tools.

- Showcase Collaboration and Leadership : Highlight your experience in leading research teams, collaborating on multi-disciplinary projects, or mentoring junior researchers. This demonstrates your ability to contribute to a team and lead scientific projects.

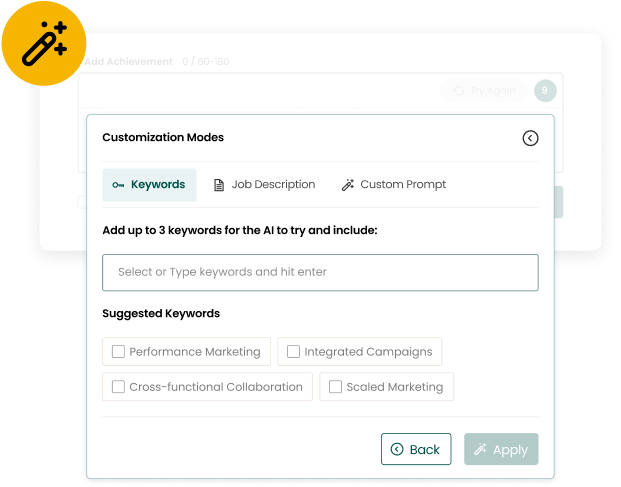

The Smarter, Faster Way to Write Your CV

- Directed a team of 10 researchers in a groundbreaking study on gene therapy, resulting in 3 published papers in high-impact journals and a 20% increase in departmental funding.

- Implemented a new data analysis protocol using advanced statistical software, improving the accuracy of research findings by 30% and accelerating the data processing time by 40%.

- Developed a novel research methodology that reduced the time to results by 25%, leading to faster publication and increased recognition within the scientific community.

- Coordinated a cross-functional team of scientists and engineers in the development of a new biomedical device, which is now being used in over 50 hospitals nationwide.

- Secured a $500,000 grant for a 3-year research project on neurodegenerative diseases, contributing to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Presented research findings at 5 international conferences, enhancing the visibility of the organization and fostering collaborations with other research institutions.

- Conducted a comprehensive study on the effects of environmental factors on cell growth, leading to a better understanding of cell behavior and contributing to 2 peer-reviewed publications.

- Collaborated with a multidisciplinary team to develop a new laboratory protocol, improving lab safety and efficiency by 15%.

- Initiated a mentoring program for junior researchers, improving their technical skills and increasing their publication rate by 20%.

- Team Leadership and Management

- Advanced Data Analysis

- Research Methodology Development

- Cross-functional Collaboration

- Grant Writing and Fundraising

- Public Speaking and Presentation

- Comprehensive Scientific Research

- Protocol Development and Implementation

- Mentorship and Training

- Project Coordination and Execution

Research Scientist CV Template

- Conducted [type of research, e.g., clinical trials, data analysis] in collaboration with [teams/departments], leading to [result, e.g., new scientific insights, patent filings], demonstrating strong [soft skill, e.g., teamwork, leadership].

- Managed [research function, e.g., lab operations, project timelines], optimizing [process or task, e.g., data collection, experiment setup] to enhance [operational outcome, e.g., research efficiency, data accuracy].

- Implemented [system or process improvement, e.g., new lab equipment, revised data analysis methods], resulting in [quantifiable benefit, e.g., 20% time savings, improved data quality].

- Played a pivotal role in [project or initiative, e.g., drug development, environmental research], which led to [measurable impact, e.g., publication in a top-tier journal, grant funding].

- Performed [type of analysis, e.g., statistical analysis, genetic sequencing], using [analytical tools/methods] to inform [decision-making/action, e.g., research direction, policy recommendations].

- Instrumental in [task or responsibility, e.g., lab safety protocols, mentoring junior researchers], ensuring [quality or standard, e.g., compliance, professional development] across all research activities.

- Major: Name of Major

- Minor: Name of Minor

100+ Free Resume Templates

How to format a research scientist cv, start with a compelling research objective, emphasize education and publications, detail relevant research experience, highlight technical skills and collaborations, personal statements for research scientists, research scientist personal statement examples, what makes a strong personal statement.

Compare Your CV to a Job Description

CV FAQs for Research Scientists

How long should research scientists make a cv, what's the best format for an research scientist cv, how does a research scientist cv differ from a resume, related cvs for research scientist.

Research Analyst CV

Research Assistant CV

Research Associate CV

Research Coordinator CV

Research Manager CV

Research Technician CV

Try our AI Resume Builder

- Self & Career Exploration

- Networking & Relationship Building

- Resume, CV & Cover Letter

- Interviewing

- Internships

- Blue Chip Leadership Experience

- Experiential Learning

- Research Experiences

- Transferable Skills

- Functional Skills

- Online Profiles

- Offer Evaluation & Negotiation

- Arts & Media

- Commerce & Management

- Data & Technology

- Education & Social Services

- Engineering & Infrastructure

- Environment & Resources

- Global Impact & Public Service

- Health & Biosciences

- Law & Justice

- Research & Academia

- Recent Alumni

- Other Alumni Interest Areas

- People of Color

- First Generation

- International

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Families

Academic Curriculum Vitae (CV) Example and Writing Tips

- Share This: Share Academic Curriculum Vitae (CV) Example and Writing Tips on Facebook Share Academic Curriculum Vitae (CV) Example and Writing Tips on LinkedIn Share Academic Curriculum Vitae (CV) Example and Writing Tips on X

Updated July 30, 2020 | Link to article from The Balance Careers

A curriculum vitae (CV) written for academia should highlight research and teaching experience, publications, grants and fellowships, professional associations and licenses, awards, and any other details in your experience that show you’re the best candidate for a faculty or research position advertised by a college or university.

When writing an academic CV, make sure you know what sections to include and how to structure your document.

Tips for Writing an Academic CV

Think about length. Unlike resumes (and even some other CVs), academic CVs can be any length. This is because you need to include all of your relevant publications, conferences, fellowships, etc. 1 Of course, if you are applying to a particular job, check to see if the job listing includes any information on a page limit for your CV.

Think about structure . More important than length is structure. When writing your CV, place the most important information at the top. Often, this will include your education, employment history, and publications. You may also consider adding a personal statement to make your CV stand out. Within each section, list your experiences in reverse chronological order.

Consider your audience . Like a resume, be sure to tailor your CV to your audience. For example, think carefully about the university or department you are applying to work at. Has this department traditionally valued publication over teaching when it makes tenure and promotion decisions? If so, you should describe your publications before listing your teaching experience.

If, however, you are applying to, say, a community college that prides itself on the quality of its instruction, your teaching accomplishments should have pride of place. In this case, the teaching section (in reverse chronological order) should proceed your publications section.

Talk to someone in your field. Ask someone in your field for feedback on how to structure your CV. Every academic department expects slightly different things from a CV. Talk to successful people in your field or department, and ask if anyone is willing to share a sample CV with you. This will help you craft a CV that will impress people in your field.

Make it easy to read. Keep your CV uncluttered by including ample margins (about 1 inch on all sides) and space between each section. You might also include bullet points in some sections (such as when listing the courses you taught at each university) to make your CV easy to read.

Important: Be sure to use an easy-to-read font , such as Times New Roman, in a font size of about 12-pt.

By making your CV clear and easy to follow, you increase the chances that an employer will look at it carefully.

Be consistent. Be consistent with whatever format you choose. For example, if you bold one section title, bold all section titles. Consistency will make it easy for people to read and follow along with your CV.

Carefully edit. You want your CV to show that you are professional and polished. Therefore, your document should be error-free. Read through your CV and proofread it for any spelling or grammar errors. Ask a friend or family member to look it over as well.

Academic Curriculum Vitae Format

This CV format will give you a sense of what you might include in your academic CV. When writing your own curriculum vitae, tailor your sections (and the order of those sections) to your field, and to the job that you want.

Note: Some of these sections might not be applicable to your field, so remove any that don’t make sense for you.

CONTACT INFORMATION Name Address City, State Zip Code Telephone Cell Phone Email

SUMMARY STATEMENT This is an optional section. In it, include a brief list of the highlights of your candidacy.

EDUCATION List your academic background, including undergraduate and graduate institutions attended. For each degree, list the institution, location, degree, and date of graduation. If applicable, include your dissertation or thesis title, and your advisors.

EMPLOYMENT HISTORY List your employment history in reverse chronological order, including position details and dates. You might break this into multiple sections based on your field. For example, you might have a section called “Teaching Experience” and another section called “Administrative Experience.”

POSTDOCTORAL TRAINING List your postdoctoral, research, and/or clinical experiences, if applicable.

FELLOWSHIPS / GRANTS List internships and fellowships, including organization, title, and dates. Also include any grants you have been given. Depending on your field, you might include the amount of money awarded for each grant.

HONORS / AWARDS Include any awards you have received that are related to your work.

CONFERENCES / TALKS List any presentations (including poster presentations) or invited talks that you have given. Also list any conferences or panels that you have organized.

SERVICE Include any service you have done for your department, such as serving as an advisor to students, acting as chair of a department, or providing any other administrative assistance.

LICENSES / CERTIFICATION List type of license, certification, or accreditation, and date received.

PUBLICATIONS / BOOKS Include any publications, including books, book chapters, articles, book reviews, and more. Include all of the information about each publication, including the title, journal title, date of publication, and (if applicable) page numbers.

PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS List any professional organizations that you belong to. Mention if you hold a position on the board of any organization.

SKILLS / INTERESTS This is an optional section that you can use to show a bit more about who you are. Only include relevant skills and interests. For example, you might mention if you speak a foreign language, or have experience with web design.

REFERENCES Depending on your field, you might include a list of your references at the end of your CV.

Academic Curriculum Vitae Example

This is an example of an academic curriculum vitae. Download the academic CV template (compatible with Google Docs and Word Online) or see below for more examples.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/20608172020-704633147361447da63bf6afc74808e8.jpg)

Download the Word Template

Academic Curriculum Vitae Example (Text Version)

JOHN SMITH 287 Market Street Minneapolis, MN 55404 Phone: 555-555-5555 [email protected]

EDUCATION:Ph.D., Psychology, University of Minnesota, 2019 Concentrations: Psychology, Community Psychology Dissertation: A Study of Learning-Disabled Children in a Low-Income Community Dissertation Advisors: Susan Hanford, Ph.D., Bill Andersen, Ph.D., Melissa Chambers, MSW

M.A., Psychology, University at Albany, 2017 Concentrations: Psychology, Special Education Thesis: Communication Skills of Learning-Disabled Children Thesis Advisor: Jennifer Atkins, Ph.D.

B.A, Psychology, California State University-Long Beach, 2015

TEACHING EXPERIENCE:

Instructor, University of Minnesota, 2017-2019 University of Minnesota Courses: Psychology in the Classroom, Adolescent Psychology

Teaching Assistant, University at Albany, 2015-2017 Courses: Special Education, Learning Disabilities, Introduction to Psychology

RESEARCH EXPERIENCE:

Postdoctoral Fellow, XYZ Hospital, 2019-2020 Administered extensive neuropsychological and psychodiagnostic assessment for children ages 3-6 for study on impact of in-class technology on children with various neurodevelopmental conditions

PUBLICATIONS:

North, T., and Smith, J. (Forthcoming). “Technology and Classroom Learning in a Mixed Education Space.” Journal of Adolescent Psychology, vol. 12.

Willis, A., North, T., and Smith, J. (2019). “The Behavior of Learning Disabled Adolescents in the Classroom.” Journal of Educational Psychology , volume 81, 120-125.

PRESENTATIONS:

Smith, John (2019). “The Behavior of Learning Disabled Adolescents in the Classroom.” Paper presented at the Psychology Conference at the University of Minnesota.

Smith, John (2018). “Tailoring Assignments within Inclusive Classrooms.” Paper presented at Brown Bag Series, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota.

GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS:

Nelson G. Stevens Fellowship (XYZ Research Facility, 2019)

RDB Grant (University of Minnesota Research Grant, 2018) Workshop Grant (for ASPA meeting in New York, 2017)

AWARDS AND HONORS:

Treldar Scholar, 2019 Teaching Fellow of the Year, 2018 Academic Excellence Award, 2017

PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS:

Psychology Association of America National Association of Adolescent Psychology

RELEVANT SKILLS:

- Programming ability in C++ and PHP

- Extensive knowledge of SPSSX and SAS statistical programs.

- Fluent in German, French, and Spanish

We respectfully acknowledge the University of Arizona is on the land and territories of Indigenous peoples. Today, Arizona is home to 22 federally recognized tribes, with Tucson being home to the O'odham and the Yaqui. Committed to diversity and inclusion, the University strives to build sustainable relationships with sovereign Native Nations and Indigenous communities through education offerings, partnerships, and community service.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- AEM Educ Train

- v.5(4); 2021 Aug

A guide to creating a high‐quality curriculum vitae

Michael gottlieb.

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago Illinois, USA

Susan B. Promes

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, Penn State Health System, Hershey Pennsylvania, USA

Wendy C. Coates

3 Department of Emergency Medicine, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, Los Angeles California, USA

Associated Data

Introduction.

The curriculum vitae (CV) is nearly ubiquitous in academic medicine, often beginning prior to medical school and continually being refined throughout graduate and postgraduate training. The CV serves as a formal record of your experiences and accomplishments, which can help others to better understand what you have done thus far and your potential qualifications for a position or promotion. 1 An academic CV differs from a resume, in that the latter is much more condensed (typically 1–2 pages) and focuses more on specific skills and qualifications, rather than cataloguing your full academic history.

A well‐crafted CV is important throughout an academic career. A CV is not a static document and can be formatted to serve a variety of needs. One of the most common uses of a CV is to apply for a new job or leadership position. Most chairs and hiring committees will expect a CV and cover letter as the initial component of the application materials. Additionally, the CV is utilized as one of the primary criteria as part of the dossier used for making decisions about promotion and tenure (P&T). We wish to emphasize that the CV should not be the sole criterion for a position or advancement and that it is important to engage in holistic review of applications 2 ; however, the CV is one important component of this process. In addition to the above, a CV is important personally for considering and reevaluating your niche and career path. It can serve as a tool for you and your mentor to discuss your interests and current progress and identify areas for future growth. Finally, the CV serves as a record of your personal progress and achievements and can be invaluable in crafting your personal statement for academic advancement. It can also be a valuable tool to help boost morale and combat imposter syndrome. 3

Despite the important role that a CV plays in career and academic advancement, we have seen wide variations in the quality, format, and structure of CVs. Building upon a recent CV workshop at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Scientific Assembly, we sought to share our experience and insights to help guide resident and attending physicians when embarking on creating or refining their CV.

COMPONENTS OF A CV

While the exact naming conventions and order may vary by institution, we will review the most common components of a CV and provide tangible recommendations for each component. In general, a CV should have a consistent and legible font, appropriate spacing and use of line breaks, bolding to highlight key components or headers, and the dates should be listed in a consistent order (either chronological or reverse chronological). A sample CV is included here as Appendix S1 .

The first page should include your name and degrees at the top. We recommend that your name be written in a larger font and bolded. This allows your name to stand out and reduces the risk of your CV being accidentally confused with another person when there are multiple applicants. The top of the page should also include your contact information, such as your address, phone number, and email address. We generally recommend using your work address for privacy. However, if you are applying for a new job, you may want to consider using an email address that is more confidential, such as your personal email. A cell phone number, work number, or both could be included depending on your preferred contact number(s). Finally, the first page should include the date that the CV was last updated. This will assist you with tracking the versions, as well as the recipient if you send an updated CV later. All subsequent pages should include your italicized name at the top right as a header along with the page number on the bottom right as a footer. This can assist with ensuring that no pages are lost or reviewed out of order if the CV is printed.

The next section is your education. This begins in reverse chronological order with your postgraduate training (e.g., residency, fellowship), followed by graduate training (e.g., undergraduate institution, medical school, masters degree programs). When listing your undergraduate training, make sure to include the institution and dates attended, degree obtained, major(s), minor(s), and any honors (e.g., cum laude, distinctions, Alpha Omega Alpha). You should include any advanced leadership training that does not fall within the above categories (e.g., leadership courses, speaker courses) as a separate section located after the education section, which could be entitled “Additional Training” or “Faculty Development.”

The next component of the CV should contain appointments, such as academic appointments and nonacademic or hospital appointments. For faculty, you should include your current and prior academic appointments along with the dates at each rank. This will be particularly valuable for P&T committees. You should also include all relevant employment. This can include your current role as well as prior clinical roles. These should include the title, department, institution, and date range. As a general rule, you should limit these to jobs most relevant to the current position and should routinely trim these back as you advance your career. For example, being a scribe in the emergency department would be relevant for medical students and residents but would no longer be relevant for a full professor. Some prefer to maintain selected early accomplishments, but these are individual decisions that warrant deliberate consideration. For those with prior careers outside medicine, consider keeping them in, particularly if they are directly relevant to the current role. As an example, if you are applying for a chair position, a history of being the chief financial officer of a company would be relevant regardless of the timing.

You should generally list all honors and awards that you have received along with the corresponding date. If an award is not readily apparent by the name, consider adding a brief description or annotation. As you move forward in your career, you may consider removing less relevant awards and honors, similar to positions as discussed in the preceding paragraph.

Certifications and licensure are important to include along with the dates active. However, you should avoid including information such as your DEA or medical license number unless explicitly required to reduce the risk of this being misappropriated. Additionally, you should include the societies to which you belong. While society memberships could be listed later (given the reduced impact compared with other aspects of your CV), we believe it is valuable to list early because it allows you to abbreviate societies with long names if used later in the CV (e.g., leadership positions, committee roles, invited lectures). However, this may depend on your institution's format.

You should also include a dedicated section on your leadership positions at your institution and within professional societies as well as any committee or task force membership roles within professional societies. While traditionally these are listed in order based on the dates of involvement, you could consider grouping these by organization to demonstrate dedication to a specific group. This can be particularly valuable if you are applying for a leadership role in one of those societies as well as for helping support the citizenship components of your P&T application. For some institutions, this may alternatively be listed in a “service” or “administrative leadership” category.

The teaching section should include your involvement with leading any local, regional, and national curricula. While not as comprehensive as an educator's portfolio, 4 you should consider including sufficient information for the reader to understand the scope, size, and time commitment of the program. It is important to separate this curricular section (i.e., a set of courses) from the latter section on individual courses. You may also consider separating into undergraduate medical education (e.g., medical students), graduate medical education (e.g., residents, fellows), and other learners (e.g., paramedics, nursing). We recommend including the program title, your role, the number of learners, type of learners (specialty and experience level), frequency of the courses, length of the sessions, and dates that the program occurred. As you advance in your career, you may consider removing low‐impact internal teaching activities.

The mentorship section should include any people you are or have been mentoring. When deciding who to include, consider whether you could readily describe the skills, knowledge, insights, or value you have provided to the mentee. This section should include their name, length of mentorship, current role (e.g., faculty role, fellow, resident, medical student), and institution as well as their prior role when you began mentoring them (if applicable). As not all institutional CV formats have a designated location for this, you could consider making this a separate appendix file.

The scientific and scholarly activities section (also known as the research section) can include a wide array of components. We recommend including any research‐specific service roles (e.g., editor, reviewer for professional journals, reviewer for granting agencies) as well as scholarship (e.g., grant funding, abstract or poster presentations, peer‐reviewed manuscripts, books, blog posts), in accordance with your institution's preferred format. We recommend that all publications be numbered and listed in chronological or reverse chronological order, depending on your institution's preference. Publications should be listed in a citation format consistent with your institutional guidelines, and you should consider adding the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) or PubMed identifier (PMID). When listing grant funding, you should include the funding source, amount, grant award name, date(s), and your role. You could also consider adding an annotation here to describe the importance of an item or your contribution to a grant or manuscript. For the research presentations, manuscripts, and book chapters, we recommend putting your name in bold and/or italics to help your name stand out. You could also consider adding your research metrics here (e.g., h‐index, i‐10) to help demonstrate your scholarly impact. 5 , 6

Lectures, podcasts, and nonresearch presentations could be listed within either teaching or scholarship and we advise following your institutional guidelines. 7 These should include the URL, link, or website and data on downloads if available. For individual lectures and didactic sessions, include the institution or professional group, date, location, number of attendees, contact hours (i.e., length of session), and topic. Consider separating this out into local lectures; grand rounds at outside institutions; and invited sessions at regional, national, or international conferences, with higher‐impact (i.e., international or invited) presentations listed first.

Additional categories may be added and may include your fluency in another language or additional expertise (e.g., SPSS, RevMan). It is advisable to be honest when listing these, because they may be challenged. For example, if foreign language proficiency is indicated as “fluent,” it is possible that a prospective employer may wish to conduct the interview in that language. Some people also list a few extracurricular passions (e.g., sports, literature) that may serve to foster a connection with a potential interviewer.

Finally, your last page should include your references. Depending on the position, you could either list your references or add a comment “references available on request.” The latter component may be useful when you are applying for an external position. When including references, identify three references who can speak to your qualifications for a given position. This may include your department chair, mentors, those in similar roles that you are applying for, and those who are a direct supervisor to you. In many cases, your references may not be from your institution. Make sure that your references know they have been listed as a reference. You should include their role and current address, phone, and email to guide the reader when reaching out to them.

BEST PRACTICES FOR MANAGING YOUR CV

In this section, we describe recommended strategies to manage your CV (Table 1 ). Even though institutions often require the same information, each may have a specific format for organizing and/or building your CV. Some institutions furnish a guideline that includes the desired headings and order of the entries on the CV, while others provide an electronic fillable template. By adhering to the desired format for your institution and advancement track (e.g., research, clinician‐educator, tenure), your P&T committee will be able to access all information easily to process academic advancement decisions. Since most formats include similar categories, you can send this version of your CV to prospective employers or other interested parties upon request. However, if you are seeking a new career or hope to delve into a niche within a particular academic realm, it may be useful to tailor your CV to highlight relevant aspects.

Best practices for creating and managing the CV for career advancement

| Best practice | Process | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Use the correct format | Use institutional standard. | Ease of access by P&T committee. |

| Update frequently | Develop a routine. | Assures comprehensive inclusion of achievements. |

| Keep a working document | Keep an unpaginated CV accessible for real‐time updates. | Allows easy entry of data without worrying about section/page breaks. |

| Create a shareable CV | Delete irrelevant categories. Keep sections together. Set up logical pagination. Save as PDF to access on demand. | Creates a visually pleasing, professional document with organized and relevant information. |

| Keep a track record | Save CV at the end of each year. Refer to CV history for dossier. Appreciate self‐progress. | Provides accurate timestamps for interim accomplishments (personal statements). Highlights personal progress. |

| Seek feedback | Review CV with mentors and departmental P&T representative. | Facilitates compliance with norms. |

Abbreviations: CV, curriculum vitae; PDF, portable document format; P&T, promotion and tenure.

If you relocate to a new institution, it is prudent to update your CV to the new format as soon as possible. One strategy to ensure you are compliant with the correct CV format for your institution is to reach out to the people in your department who manage this area. It may also be helpful to ask a respected role model who has been successful in the same career track to share their CV as a real‐world example. 1 In addition to simply seeing their formatted CV, it is a good chance to consider your own career aspirations and to identify a potential local mentor.

A busy academician who is working hard to advance in the appropriate career track may generate numerous additions to their CV in a short period of time. Waiting until the last minute during dossier preparation for an academic action may lead to omission of important details, such as collaborators, dates or locations of occurrence, and even the events themselves, so it is critical to develop a process that reliably captures all aspects of each accomplishment (e.g., lectures, awards, publications). There are many strategies, but the most important factor is to identify those that fit into your natural routine. Some examples include real‐time entry as soon as an event or accomplishment occurs, creating an email folder of items to add to your CV, scheduling a recurring calendar event weekly or monthly to update your master CV, or using a voice recorder or handwritten or electronic notes to add events in real time and transfer to the CV at planned intervals. You can also refer to your electronic calendar for details about prior sessions. It is also important to update the details on events that have already been entered as they become available, such as adding DOI, PMID, and publication details (e.g., volume, page numbers). To facilitate this, you could create a Google Scholar alert for your publications and citations. 8 This will allow you to know when your publications are released in print or are assigned to an electronic issue and provide citation metrics as described above.

Some people keep an easily accessible file on their desktop that links to an unpaginated working document of their CV that uses accurate spelling, punctuation, grammar, headings, bold typeface, underlines, logical hyphenations, margins, fonts, alignment, and indentations as they should appear in the final formatted CV (Table 2 ). This can facilitate real‐time updating without the need to reformat the pages after every entry. Another option is to create a table without borders under each section heading with the necessary columns and subheadings. This can be an efficient way to easily add items as a new row with consistent formatting and pacing. When it is time to send your CV to a prospective employer, a professional organization, or your P&T committee, you should present your CV in a visually pleasing, well‐organized manner. This includes formatting page breaks to avoid having items split across pages, including boldface type and/or capitalization for section headers, ensuring consistent alignment, and eliminating spelling and grammatical errors. This will also allow you to add or remove specific components to best meet the objectives for this particular CV.

Strategies for converting your working document into the finalized CV

| Remove unnecessary sections | Delete blank sections of templated CV, such as “grants received” if there are none. An exception is if this is a required field that is designated by the entity requesting the CV. In this case, add “N/A.” |

| Use page breaks to keep items together | Avoid splitting items across pages. Use page breaks to move the item or section to the next page so the entire section appears as a cohesive unit. It is acceptable to have some extra space at the bottom of a page to accomplish this step. |

| Update references and publications | Update references (if included) to assure that the correct individuals are listed with current contact information. Also update publications with DOI, PMID, and journal issue information. |

| Perform a final review | Review the spelling, grammar, page/line breaks, and content to ensure that it is ready to be distributed. |

| Convert to a PDF | Convert the working word processing document file to a PDF for dissemination. This will ensure that it is received in the desired formatting and prevent alterations. |

Abbreviations: CV, curriculum vitae; DOI, digital object identifier; PDF, portable document format; PMID, PubMed identifier.

When updating your CV, we recommend opening the working document and saving each revision as a new file with the updated date listed (e.g., Gottlieb CV [10‐5‐21]). This prevents inadvertent changes to the working document and allows for final formatting prior to dissemination. We recommend saving this as both a PDF and an editable Word document. The PDF can be sent to others to ensure that the formatting is not altered when opened on the recipient's computer.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS: RESUMES, COVER LETTERS, AND THE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

It is important to delineate the difference between a CV and a resume. A CV is generally expected for people applying for academic positions, whereas a resume is more commonly requested for other professional positions that are nonacademic or non–research oriented (Table 3 ).

Comparison of a CV versus resume

| CV | Resume | |

|---|---|---|

| Target organization | Academic medical center, university, or professional organization | Clinical or industry position not involving teaching or research |

| Goal | Present a detailed list of your academic credentials—training, teaching experience, research (including grants), publications, honors/awards, and service | Highlight unique attributes, skills, and accomplishments. Does not need to be exhaustive. |

| Length | Variable depending on experience | No more than 2 pages |

| Publications | List all publications | Only include if relevant to the position |

| Honors, awards, and affiliations | Include all honors, awards, and affiliations | Curtail listing of honors, awards, and affiliations and consider omitting |

| References | May include | Do not include |

Adapted from the Princeton University Center for Career Development Guide. 11

Abbreviation: CV, curriculum vitae.

CVs generally include a comprehensive (exhaustive) list of positions you have held, honors and awards you received, and activities you have participated in up to current time. In fact, curriculum vitae is Latin for “course of (one's) life.” As defined by the Merriam‐Webster dictionary, a resume is a short account of one's career and qualifications. 9 A resume is concise and much shorter than a CV, typically being no longer than two pages in length. The goal of a resume is to highlight your unique attributes, skills, and accomplishments and align them with your career goal to open the door for an interview. It does not contain all the items that are listed chronologically in a CV. 10 Listing a career goal that is in line with the position you are applying for is common practice when preparing a resume. The career goal is generally explicitly stated on the first line of the document under your name and contact information. Research is generally not included in a resume unless it is explicitly required for the position you are seeking. References are also commonly omitted on a resume.

Regardless of whether you are submitting a CV or resume for a job you are seeking, you should prepare a cover letter to introduce yourself and your interest in the position. If there is something that specifically attracted you to the position or the area, this is the place to include that information. If there is a specific area of expertise asked for in an advertisement or mentioned by a recruiter be sure to address it in your cover letter. It is important to address your cover letter to the individual who will be making the decision on who will be invited to interview or possibly a search committee chair or recruiter. The cover letter is an important tool to persuade the reader through a personalized message that you are the right person for the job, though it should not simply be a rehash of your resume or CV. The cover letter should be brief, no more than one page in length. In general, you will need to craft a separate cover letter for each application.

For those individuals with longer CVs, you may want to consider preparing a one‐ to two‐page high‐level executive summary of your key work experiences, personal qualities, and skills you possess that will set you up for success in the position you are pursuing. An executive summary is placed at the top of your document to help the employer zero in on key aspects of your candidacy. It should be direct and focused on the key components you wish to highlight. Think of it as an abstract or teaser of what can be found in more detail in your CV. An executive summary should showcase your best attributes up front.

Curricula vitae are important for a variety of uses, including applying for new leadership and employment positions, seeking academic advancement through promotion and tenure, and reevaluating your niche. This article highlights the key features of a curriculum vitae, recommendations for creating and maintaining a curriculum vitae, and key differences from a resume. We hope this provides a valuable guide for those at any career stage who are seeking to enhance the quality of their curriculum vitae.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Sample CV.

Gottlieb M, Promes SB, Coates WC. A guide to creating a high‐quality curriculum vitae . AEM Educ Train . 2021; 5 :e10717. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10717 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Supervising Editor: Daniel J. Egan, MD.

Research CV Examples and Templates for 2022

Start creating your CV in minutes by using our 21 customizable templates or view one of our handpicked Research examples.

Join over 260,000 professionals using our Research examples with VisualCV. Sign up to choose your template, import example content, and customize your content to stand out in your next job search.

- How do you write a research CV?

To write a research CV, follow these steps:

- Select a CV template that’s right for research/academia.

- Next, add your research goal within your CV summary or objective.

- List your GPA clearly.

- Show that you perform research work independently and how your past experience or skills will be helpful.

- Add your research publications.

- How do you list research experience on a CV?

To add your research experience on a CV, add another entry to your work experience section and list the research work you did in a bulleted list.

- Research CV summary and profile

Ready to start with your Researcher Curriculum Vitae? See our hand picked CV Examples above and view our live Researcher CV Examples from our free CV builder .

- Research CV Objective

A research position is a person engaged in research, possibly recognized as such by a formal title. This is a very broad definition and relates to the fact that research positions generally cover multiple jobs and job titles. It’s important to distinguish between these positions so that we may accurately define research cv objectives.

The first objective to a research cv is to determine if the job you are applying for requires specific qualifications and/or education. For example, it is likely that research assistant roles will require a degree or postgraduate degree to even apply for the position, whereas a research fellow or research associate will usually require a minimum of a master’s degree.

Once you’ve identified your qualifications are sufficient, it is now time to show your expertise in the associated field.