What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Rawan Elbaba, Student Reporting Labs Rawan Elbaba, Student Reporting Labs

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/why-on-screen-representation-matters-according-to-these-teens

Why on-screen representation matters, according to these teens

Why does representation in pop culture matter?

For some young students, portrayals of minorities in the media not only affect how others see them, but it affects how they see themselves.

“I do think it’s powerful for people of a minority race to be represented in pop culture to really show a message that everybody has a place in this world,” said Alec Fields, a junior at Forest Hills High School in Pennsylvania.

Fields was one of 144 middle and high school students who were interviewed about seeing themselves reflected — or not — on the screen. PBS NewsHour turned to our Student Reporting Labs from across the country to hear what students had to say a topic that research shows still has room for growth.

The success of recent films like “Black Panther” and “Crazy Rich Asians” have — again — sent a message about the importance of representation of minorities, not only in Hollywood but in other aspects of pop culture as well.

Only two out of every 10 lead film actors (or 19.8 percent) were people of color in 2017, this year’s UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report found. Still, that’s a jump from the year before, when people of color accounted for 13.9 percent of lead roles. People of color have yet to reach proportional representation within the film industry, but there have been gains in specific areas, including film leads and overall cast diversity.

According to 2018 U.S. Census Bureau estimates , the nation’s population is nearly 40 percent non-white. By 2055, the country’s racial makeup is expected to change dramatically, the U.S. will not have one racial or ethnic majority group by 2055, the Pew Research Center estimated .

Some students said that not seeing yourself represented in elements of pop culture can affect mental health.

“It just makes you feel like, ‘Why don’t I see anybody like me?’ [It] kind of like brings your self-esteem down,” said Kimore Willis, a junior at Etiwanda High School in California.

Others said they often look to trends in pop culture when forming their own identities.

“We need to see people that look like ourselves and can say, ‘Oh, that looks like me!’ or ‘I identify with that,’” said Sonali Chhotalal, a junior at Cape May Technical High School in New Jersey.

Others, however, feel that Hollywood is overcompensating for their lack of diversity by depicting exaggerated and stereotypical characters.

Eric Wojtalewicz from Black River Falls High School in Wisconsin said that he sees a lot of gay characters that seem “over-the-top,” playing on old tropes. “I definitely think that not all gays are like that,” he said.

Kate Casper, a junior at T.C. Williams High School in Virginia, called Hollywood’s attempt at diversity “disingenuous.” Although there can never be enough diversity, Casper said, she feels that the entertainment industry is using diversity for economic benefit. “Diversity equals money in today’s world, which is cool, I guess,” she said, adding that “it’s cooler to have pure motives.”

The UCLA report agrees that diversity sells. It says that the median global box office has been the highest for films featuring casts that were more than 20-percent minority, making nearly $450 million in 2017.

Although public opinion may be divided about whether the entertainment industry is doing enough to represent all types of people, South Mountain High School student Dazhane Brown in Arizona said that feeling represented is “empowering.”

“If you see people who look like you and act like you and speak like you and come from the same place you come from … it serves as an inspiration,” Brown said.

PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs produced this story in an effort to highlight the importance of representation of minorities in popular culture. Students from 31 Labs across the country submitted these responses.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Why Jane Fonda is putting herself on the line to fight climate change

Arts Nov 07

Why Representation Matters and Why It’s Still Not Enough

Reflections on growing up brown, queer, and asian american..

Posted December 27, 2021 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- Positive media representation can be helpful in increasing self-esteem for people of marginalized groups (especially youth).

- Interpersonal contact and exposure through media representation can assist in reducing stereotypes of underrepresented groups.

- Representation in educational curricula and social media can provide validation and support, especially for youth of marginalized groups.

Growing up as a Brown Asian American child of immigrants, I never really saw anyone who looked like me in the media. The TV shows and movies I watched mostly concentrated on blonde-haired, white, or light-skinned protagonists. They also normalized western and heterosexist ideals and behaviors, while hardly ever depicting things that reflected my everyday life. For example, it was equally odd and fascinating that people on TV didn’t eat rice at every meal; that their parents didn’t speak with accents; or that no one seemed to navigate a world of daily microaggressions . Despite these observations, I continued to absorb this mass media—internalizing messages of what my life should be like or what I should aspire to be like.

Because there were so few media images of people who looked like me, I distinctly remember the joy and validation that emerged when I did see those representations. Filipino American actors like Ernie Reyes, Nia Peeples, Dante Basco, and Tia Carrere looked like they could be my cousins. Each time they sporadically appeared in films and television series throughout my youth, their mere presence brought a sense of pride. However, because they never played Filipino characters (e.g., Carrere was Chinese American in Wayne's World ) or their racial identities remained unaddressed (e.g., Basco as Rufio in Hook ), I did not know for certain that they were Filipino American like me. And because the internet was not readily accessible (nor fully informational) until my late adolescence , I could not easily find out.

Through my Ethnic Studies classes as an undergraduate student (and my later research on Asian American and Filipino American experiences with microaggressions), I discovered that my perspectives were not that unique. Many Asian Americans and other people of color often struggle with their racial and ethnic identity development —with many citing how a lack of media representation negatively impacts their self-esteem and overall views of their racial or cultural groups. Scholars and community leaders have declared mottos like how it's "hard to be what you can’t see," asserting that people from marginalized groups do not pursue career or academic opportunities when they are not exposed to such possibilities. For example, when women (and women of color specifically) don’t see themselves represented in STEM fields , they may internalize that such careers are not made for them. When people of color don’t see themselves in the arts or in government positions, they likely learn similar messages too.

Complicating these messages are my intersectional identities as a queer person of color. In my teens, it was heartbreakingly lonely to witness everyday homophobia (especially unnecessary homophobic language) in almost all television programming. The few visual examples I saw of anyone LGBTQ involved mostly white, gay, cisgender people. While there was some comfort in seeing them navigate their coming out processes or overcome heterosexism on screen, their storylines often appeared unrealistic—at least in comparison to the nuanced homophobia I observed in my religious, immigrant family. In some ways, not seeing LGBTQ people of color in the media kept me in the closet for years.

How representation can help

Representation can serve as opportunities for minoritized people to find community support and validation. For example, recent studies have found that social media has given LGBTQ young people the outlets to connect with others—especially when the COVID-19 pandemic has limited in-person opportunities. Given the increased suicidal ideation, depression , and other mental health issues among LGBTQ youth amidst this global pandemic, visibility via social media can possibly save lives. Relatedly, taking Ethnic Studies courses can be valuable in helping students to develop a critical consciousness that is culturally relevant to their lives. In this way, representation can allow students of color to personally connect to school, potentially making their educational pursuits more meaningful.

Further, representation can be helpful in reducing negative stereotypes about other groups. Initially discussed by psychologist Dr. Gordon Allport as Intergroup Contact Theory, researchers believed that the more exposure or contact that people had to groups who were different from them, the less likely they would maintain prejudice . Literature has supported how positive LGBTQ media representation helped transform public opinions about LGBTQ people and their rights. In 2019, the Pew Research Center reported that the general US population significantly changed their views of same-sex marriage in just 15 years—with 60% of the population being opposed in 2004 to 61% in favor in 2019. While there are many other factors that likely influenced these perspective shifts, studies suggest that positive LGBTQ media depictions played a significant role.

For Asian Americans and other groups who have been historically underrepresented in the media, any visibility can feel like a win. For example, Gold House recently featured an article in Vanity Fair , highlighting the power of Asian American visibility in the media—citing blockbuster films like Crazy Rich Asians and Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings . Asian American producers like Mindy Kaling of Never Have I Ever and The Sex Lives of College Girls demonstrate how influential creators of color can initiate their own projects and write their own storylines, in order to directly increase representation (and indirectly increase mental health and positive esteem for its audiences of color).

When representation is not enough

However, representation simply is not enough—especially when it is one-dimensional, superficial, or not actually representative. Some scholars describe how Asian American media depictions still tend to reinforce stereotypes, which may negatively impact identity development for Asian American youth. Asian American Studies is still needed to teach about oppression and to combat hate violence. Further, representation might also fail to reflect the true diversity of communities; historically, Brown Asian Americans have been underrepresented in Asian American media, resulting in marginalization within marginalized groups. For example, Filipino Americans—despite being the first Asian American group to settle in the US and one of the largest immigrant groups—remain underrepresented across many sectors, including academia, arts, and government.

Representation should never be the final goal; instead, it should merely be one step toward equity. Having a diverse cast on a television show is meaningless if those storylines promote harmful stereotypes or fail to address societal inequities. Being the “first” at anything is pointless if there aren’t efforts to address the systemic obstacles that prevent people from certain groups from succeeding in the first place.

Instead, representation should be intentional. People in power should aim for their content to reflect their audiences—especially if they know that doing so could assist in increasing people's self-esteem and wellness. People who have the opportunity to represent their identity groups in any sector may make conscious efforts to use their influence to teach (or remind) others that their communities exist. Finally, parents and teachers can be more intentional in ensuring that their children and students always feel seen and validated. By providing youth with visual representations of people they can relate to, they can potentially save future generations from a lifetime of feeling underrepresented or misunderstood.

Kevin Leo Yabut Nadal, Ph.D., is a Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the City University of New York and the author of books including Microaggressions and Traumatic Stress .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Centre

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- Calgary, AB

- Edmonton, AB

- Hamilton, ON

- Montréal, QC

- Toronto, ON

- Vancouver, BC

- Winnipeg, MB

- Mississauga, ON

- Oakville, ON

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

The importance of representation

When I write creatively, I write about white people. Not the same white person, sure: There’s the awkward misunderstood white person, or the rich white woman destined to solve crime or the hard working white man that robs a store at gunpoint. Sitting in a conference with my creative writing teacher, I told her I’m scared to write about things that I don’t know.

I fell in love with writing as I fell in love with books. I would read the Magic Tree House, Judy Bloom, Andrew Clements and Ann M. Martin during lunch, at recess, in my room when the lights were meant to be off. I told myself I would be a writer — that I could be a writer. On the covers of my second grade novels I’d draw a girl, using the peach shade crayon, and name her Grace. Or Lindsay or Abby or Charlotte. This is a girl I felt I knew. She was all around me, in my white school, in my white town. She was on Disney Channel and Nickelodeon. She was on magazines and American Girl dolls. As I got older, this white wash became more apparent. Classical literature praises this peach-shade figment: Jane Eyre, Elizabeth Bennet, Anna Karenina. These adventurous yet respectful white women — I eventually branched out to white men — became my muse.

Representation in the media is a constant source of controversy. For decades, award shows like the Oscars and Grammys have consistently overlooked the work of black artists. Black Panther is proving to be one of the most influential movies of our time with its assertion of black power both in its plot and cast. Many other films and TV shows released in the past few years have sought to provide representation for minority groups in the media. Representation isn’t just a nice way to appease complaining minorities. The media is a reflection of who America is and isn’t. America isn’t just white, and it never has been. When America looks into a mirror, the reflection is white, Christian, financially well-off. The picturesque American citizen.

I, along with so many people of color, write about white people because that is the only face the media deems as a full character. The complexity awarded to white Americans in the media is not seen in minority characters. There is no drive to explore the sassy black sidekick when there’s the multi-faceted white person. There is no incentive to explore minority characters when they exist to further stereotypes. I assumed this was normal. Fiction is about channeling something ideal or fantastical. In my childhood, the ideal was always white. Black people were side characters or villains. They were thugs or drug lords. They were never the hero. The media is partially responsible in the process of constructing what blackness and whiteness are, and in America, the furthering of racial stereotypes only helps justify racist actions. The fight for adequate representation isn’t a new thing. Amazing people have been advocating for cultural diversity in the media since before I was born. But there is more work that needs to be done.

We are in such a place where fundamental American thought can be shifted. Right now, minorities are starting to be listened to. Minorities have been yelling for decades at a country that doesn’t acknowledge us as part of its cultural makeup. Now there are more movies, TV shows, podcasts, models, activists that are beginning to be appreciated and listened to. This is the time. Children don’t have to write about peach-colored girls. The foundations created finally have room for some footing. By pushing for representation, we can change the way America is seen by Americans. When media is white, the stories of the marginalized, of racism, unfair housing, income inequality are never told. The media is a way to bring stories to life. The complexities of different races are not realized by most Americans because they are not visible to most Americans. The media is a pivotal start in forcing Americans to confront the harsh truth of our current political dynamic. Our media is silencing the voices of millions.

Representation is a vicious cycle. We write about what we see and what we experience. When all we study is white and all we see is white, all we create is white. I applaud the great authors and thinkers that have managed to test these boundaries, to push our current media and literature out of balance. They inspire young writers like me to explore the unseen characters, the traditional sidekicks, the never forgotten villains. They also encourage us to find characters in our own identity. We are encouraged to write characters with our strength and weaknesses and flaws.

Everyday, the media reassures us that America is white. Minorities are sidekicks or the help, the American Dream is alive and well, and racism is dead. Representation in the media means that America can finally see itself in all its multicultural, multiracial, beautiful self. Representation in the media means that America sees more to minorities than stereotypes. Representation can make disadvantaged groups become real people.

Contact Natachi Onwuamaegbu at natachi ‘at’ stanford.edu.

Natachi Onwuamaegbu is a freshman from Bethesda, Maryland. She is currently undecided but is leaning towards Political Science and English. Currently, Natachi is part of the Black Student Union and hopes to run a radio station on campus. When she's not wandering around campus, Natachi likes to sit in the sun, listen to music and overuse semi-colons.

Login or create an account

Representation Is at an All-Time High on Screen, but Still Inaccurate, Nielsen Report Says

By Mónica Marie Zorrilla

Mónica Marie Zorrilla

- Wattpad Webtoon Studios Ramps Up Its Output As It Brings On a New Entertainment Head 2 years ago

- From ‘Gossip Girl’ to ‘Bel-Air,’ Black Opulence Has Taken Over TV 2 years ago

- Keenspot Graphic Novel ‘Dreamless’ by ‘Marry Me’ Creator Gets Film Adaptation (EXCLUSIVE) 2 years ago

Series like “ Reservation Dogs ,” “Gossip Girl,” “Run the World,” “Bling Empire,” “Rutherford Falls,” “The Wonder Years” and “The Sex Lives of College Girls” helped make 2021 a good year for diverse, on-screen representation . Those shows helped break barriers for AAPI, BIPOC and Native American visibility on television, as well as LGBTQ+ inclusion. Per Nielsen data for the 2021-2021 TV season, among the top 1,500 programs, 78% have some presence of racial, ethnic, gender, or sexual orientation inclusivity. But, according to Nielsen’s new Diverse Intelligence Series report, those numbers don’t tell the entire story.

It’s not just the quantity of the representation on TV, but the quality of it that Hollywood needs to care about, the study notes. Currently 42.2% of the U.S. population is racially and ethnically diverse, and that number is only projected to grow in the decades to come. But no one group is a monolith, and when you look at the diversity of groups within the AAPI, BIPOC, Native American and LGBTQ+ communities, not everyone is represented in the same way.

Related Stories

Can Today’s Tech Touchstones Solve Hollywood’s Loneliness Epidemic?

'The Fire Inside' Star Ryan Destiny on the 'Trippy Experience' of Working With Claressa Shields and Bringing the Boxer's Story to the Screen

“If you simply look at that high percentage point, you might think the majority of identity groups are well-covered. But lack of representation and diversity in popular content is more nuanced,” said Stacie de Armas, SVP, Diverse Insights & Initiatives, in a statement announcing the report “Being Seen on Screen: The Importance of Quantity and Quality Representation on TV.”

Popular on Variety

“Looking back at the media moments this year, diverse casts and stories have been in the headlines,” de Armas wrote. “Yet, according to Nielsen’s recent research, almost a quarter of people still feel that there is not enough content that adequately represents people from their identity group.”

Nielsen’s key metrics across reality, variety (scripted) and news programming include Share of Screen (SOS), which provides the composition of the top 10 recurring cast members in a program, and the Inclusion Opportunity Index, which compares the SOS of an identity group to their representation in population estimates. Nielsen also took into consideration the number of episodes a recurring cast member was present in, the number of viewing minutes a program has and the viewing audience by identity group classification.

According to the report, Black talent is above on-screen parity, but 58% of Black respondents noted that is still not enough. When crunching the numbers, Black women remain largely underrepresented in shows compared to Black men. The most representative dramas featuring Black women on-screen had, on average, 15% Black women writers in their credits, and that representation was usually positive, steering away from stereotypes and highlighting justice, power and glamor.

In addition, the report shows that South Asian SOS falls below parity, while East Asian representation is above parity on streaming at 2.8%, indicating that AAPI representation on-screen across broadcast, streamers and cable is not monolithic. Similarly, Hispanic and Latinx SOS is far more apparent on broadcast (22%)— particularly in Spanish-language programming —compared to cable at 3.5% and streaming at 8.5%; talent who identifies as Afro-Latinx over-index in genres such as action and adventure, comedy, music, horror and reality. Native American SOS was poor, approximating to less than 0.1% across broadcast and cable programming, and 0.4% on streaming platforms. That is far below parity compared to the population estimate of 1.4%.

The LGBTQ+ community had its highest representation on cable programming (7.5%), but broadcast and SVOD had less than 4%. However, based on Gracenote Video Descriptors in the report— keywords capturing the story and context across mood, theme and scenario— on-screen queer narratives and voices have been deemed authentic and meaningful, as evidenced by the top keywords present: thoughtful, goodness, personal story, conflict, challenging situation, cerebral, performers and creative settings. Other interesting findings based on Gracenote Video Descriptors include Latinas being associated with the keywords "TV reporters, athletes, teammates, victory and nieces," Black women being associated with the keywords "uplift, awareness, family bonds, competition, friendship" and White women were associated with "entertainers, conscience, morality, honesty and friendship."

More from Variety

Gary Oldman Gave Christopher Nolan an Ultimatum on ‘Oppenheimer’ Due to ‘Slow Horses’ Role: ‘If You Don’t Want Wigs’ Then ‘Get Someone Else to Do It’

Dissatisfied With Its Rate of Erosion, DVD Biz Fast-Forwards 2024 Decline

2024 Live Music Business Is Driving Record Revenues, but Some Data Points Raise Concerns

More from our brands, mark ruffalo slams elon musk, mandy patinkin sings ‘over the rainbow’ in yiddish at ‘kamala-con’.

An NFL Legend’s Custom Vacation Retreat in Montana Is Heading to Auction This Month

NCAA Could Roll Dice on Winning House Case at SCOTUS

The Best Loofahs and Body Scrubbers, According to Dermatologists

Chicago Med’s Jessy Schram on the Possibility of Hannah/Dean Romance: ‘Nothing Is Completely Off the Table’

We need your support today

Independent journalism is more important than ever. Vox is here to explain this unprecedented election cycle and help you understand the larger stakes. We will break down where the candidates stand on major issues, from economic policy to immigration, foreign policy, criminal justice, and abortion. We’ll answer your biggest questions, and we’ll explain what matters — and why. This timely and essential task, however, is expensive to produce.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

How can TV and movies get representation right? We asked 6 Hollywood diversity consultants.

Here’s what they said about writing characters that actually reflect America.

by Abbey White

In 2012, Kerry Washington, star of the Shonda Rhimes-created ABC political drama Scandal, became the first black woman to lead a network drama in nearly four decades. Two seasons later, the series became the first on a major broadcast network that “was created by a black woman, starring a black woman” and also directed by a black woman, when Ava DuVernay stepped in to helm an episode.

Fast-forward to 2016, when an episode of The CW’s post-apocalyptic drama The 100 featured a groundbreaking love scene between the show’s bisexual female lead Clarke (Eliza Taylor) and her lesbian love interest Lexa (Alycia Debnam Carey) — right before killing off Lexa. The plot bomb resonated so widely that it sparked a Hollywood pledge to stop needlessly killing LGBTQ characters and raised a larger discussion about who was dying onscreen .

With the help of social media, both shows and others like them are shifting discussions around “good representation” from a simple desire to a necessity. Who lives, who dies, and who tells the story — as Hamilton so succinctly put it — matters now perhaps more than it has ever before.

So who is helping Hollywood tell better, more diverse stories? How are they doing it? What is Hollywood currently getting right, and what is it still getting wrong? To find the answers, I spoke with diversity consultants, many from nonprofit media advocacy organizations, who, along with tasks like compiling data on minority representation, offer free training and research support to studios and networks.

Here’s what representatives from GLAAD (which focuses on LGBTQ representation), Color of Change (race), the Geena Davis Institute (gender), Define American (immigration), and RespectAbility (disability), as well as a religion expert, told me about the work of Hollywood diversity consulting and the state of representation onscreen.

Everyone wants good diversity, but “good” and “diversity” can look different to various identities

Rashad robinson, executive director, color of change.

We are looking for representations that are authentic, fair, and have humanity. Where black people are not the side script to larger stories and are not just seen through white eyes. There is a way in which we get the same types of representation over and over again, which kind of decreases the sensitivity and humanity that people receive because the media images we see of people can be so skewed.

Madeline Di Nonno, CEO, Geena Davis Institute

[Through our research,] we found that even though there were female characters, they were onscreen and speaking two to three times less. That gave us a whole other thing to talk to people. You can have a cast of 100 and 50 are female, but are you hearing them?

Elizabeth Grizzle Voorhees, entertainment media director, Define American

What most might consider good immigrant representation is characters that are hard-working, humble but high-achieving ... non-threatening to “the American way.” We find the “good immigrant versus bad immigrant” ... perpetuates the respectability politics forced upon many marginalized communities and suggests that only certain people are worthy of our humanity. [We need] reinforcement in mainstream culture that — at the end of the day — we ... have more in common than not.

Jennifer Mizrahi, CEO and president, RespectAbility

The two [current] gold standards are the TV show Speechless , which is scripted, and Born This Way , which is reality unscripted, and that’s because the leads are people with disabilities — played by people with disabilities — authentically portraying their lives.

We see it as a success if an amputee is playing a police officer in an episode of Law & Order and you never talk about that person’s disability. All you see is an incredible police officer.

Megan Reid, professor and religion consultant, Cal State Long Beach

[Some] shows do a good job of showing the faith part accurately, but that’s all we ever see. If it’s a show where religion is an essential plot, it would be helpful not just to see characters who struggle with their faith but how to make decisions about what to do in a multicultural environment.

Whether their services are offered or asked for, Hollywood diversity consultants aim to increase representation and inclusion at various levels of the industry

Zeke stokes, vice president of programs, glaad.

I can tell you in a very general way that if you are seeing LGBTQ inclusion on television, there is a very, very strong likelihood that GLAAD played a part in it at some point.

It may not be in an ongoing way with a production if it’s a long-developing arc or if an LGBTQ character or storyline is a basis for the show, but you can generally bet we were involved at the outset in helping them ensure that they weren’t falling into outdated tropes, that a character wasn’t just there to support everyone else’s storyline, that they have a well-developed storyline of their own and sort of a reason for being indispensable.

Madeline Di Nonno

[The Geena Davis Institute] has met with every major studio, network, cable company, and pretty much every division. We really focus on who is making financial decisions and who is making creative decisions.

Once something is in construction, we’re not involved unless someone has asked us to be an adviser. For example, YouTube Red has launched originals, and we were asked to be advisers on a show called Hyperlink , which is about young girls in STEM. We looked at the scripts, the dimensionality of the characters — are the characters balanced? Are they well-rounded? Are they stereotypes?

Jennifer Mizrahi

We are meeting with the networks and then reaching out to them and letting them know we are available. Big partners for us are the unions [like] the Casting Society of America’s Committee on Diversity, the Screen Writers Guild, and SAG-AFTRA.

Elizabeth Grizzle Voorhees

There are a variety of ways we engage, including casting for undocumented and documented immigrants non-scripted television programs and films, providing storylines, and on-set consultation and scene review during filming.

Rashad Robinson

The working relationship can be dependent on the entity that we’re dealing with. We do a series of salons throughout the year, where we bring together writers from a host of shows — writers from Being Mary Jane , Black-ish , and Homeland have been there. We spend hours sort of talking about different themes.

Who is asking for help may not always be who you expect

The majority of folks that reach out [to Color of Change] are not black, but it’s really about what the show is trying to achieve. Do folks feel like they’re talking to us under duress? Do they feel like they’re actually trying to get something right? Are folks trying to get a feeling for the general surface rather than trying to go deeper? Each situation is very different, and I would say there have been a number of white folks in Hollywood that have reached out with good intentions and interest in trying to deal with challenges that have existed in the past.

What we have seen [from RespectAbility’s] work in Hollywood is that there is a huge number of people working who have ADHD, dyslexia, and mental health disorders. Just like sometimes people on the autism spectrum can be better at math, science, and engineering than people not on the autism spectrum, it does seem that people who have mental health differences can be better sometimes at acting or comedy.

But those people don’t come out about it.

In many, many cases, they tell us when they speak with us, “Well, I’m living with X, but don’t tell anyone.” It’s really quite common that there are people working in Hollywood with hidden disabilities who are not publicly disclosing those disabilities.

Zeke Stokes

[GLAAD] works with a lot of straight creators who want to tell stories in a really authentic way, and ... the same is true for LGBTQ creators. If you’re a white gay male creator, you might not have the depth of personal experience to write a really authentic queer woman of color.

I think more and more the LGBTQ creators in Hollywood are realizing that there are so many LGBTQ points of view that if you’re not bringing in people that have certain experiences to help guide your creative process — either as a full-time part of the production or as a consultant — then you’re very apt to get it wrong.

The questions and challenges that Hollywood needs help with are not one size fits all

A lot of people come to [the Geena Davis Institute] for help with getting their projects greenlit. Some come to us for recommendations on financing, or they come to us for recommendations on things like female directors and writers. Many of the talent agencies don’t represent enough women writers and directors. We’re at a point where the really well-known female writers and directors are working, so it’s creatives who are maybe on the cusp that really need the support and need to be given a chance.

A lot of times people are well intentioned, but their lexicon is wrong. For example, [a script] might use the expression “wheelchair-bound,” which is just really bad to say. If someone uses a wheelchair it’s an element of freedom, because that’s how they get around. So we look at scripts and help with that lexicon.

[Color of Change] has a big report coming out this fall with UCLA on the diversity of writers’ rooms, and much of that report is about content. We’re looking at upward of 150 shows ... tracking back to three different themes. One is racism in the show and whether it’s individual or structural. Another is ways in which black people or black families feel like a problem rather than a solution. Then we’re looking at how the criminal justice system is often shown as infallible — so police officers, district attorneys, DNA evidence.

There are a lot of identities and issues outside those traditional sexual orientation and gender binaries that are suddenly in the public consciousness, and [GLAAD is] being called on to do work around that a lot. We’ve been living in this sort of transgender tipping point, so we get a lot of calls from creators and networks who want to get that narrative right.

Just in this past year or so, networks and creators have begun to tackle the realities of this next generation, which is, that they’re eschewing labels in a lot of respects. So we’re doing a lot of consulting around what that means and ... the impact of bad representation on that community.

[There] is definitely a huge effort to portray religious rituals correctly. Also an effort to make settings plausible ... [and for] more respectful portrayals of prayer leaders. Many networks are seeking to get right issues with regard to [religious] law and how it plays a part in people’s lives here and abroad.

What they have gotten wrong, but don’t normally ask for help about — and it’s a problem of perception: the lack of a plausible, nuanced range of the level of religiosity in portrayals of Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, Sikhs, [and others].

We’re starting to see more of the linking of universal themes with the stories and experiences of immigrant families. Storylines that appear in TV and film often follow the headlines we are seeing in the news media, so specific topics like deportations and ICE raids have had high-interest levels recently, [too].

Increasing intersectionality is a top priority

The point of view is: Infuse your content with a lot of female characters, and as you add, then think about the rainbow of what that could be. Could that person be someone with disabilities, could that person be someone of color, could that person be LGBTQ? Lots of times if creators have a limit on female characters, if they have only one female character, they tend to try to make her flawless. The problem comes in because there’s often just one.

If you look at the inclusion that’s happened on television over the last 20 years, from Will & Grace forward, while there has been a lot of LGBTQ inclusion, the vast majority of it, for way too long, was white men. That’s one of the things [GLAAD is] really working to change. We want to make sure that it’s not just diversity and inclusion, but we’re seeing diversity in inclusion. People of color, women, Muslims, immigrants — when you think of all these communities that have been marginalized, they all live within the LGBTQ community as well.

[RespectAbility] feels very strongly that people with physical disabilities should be represented in every crowd scene and they cannot only be white. In terms of the invisible disability — mental health, sensory, attention deficit — that can be put into a storyline. If you want to be authentic and tell authentic stories, they need to be as people are in humanity. Where’s the person who is a wheelchair user? Where’s the service dog? Where’s the person with Down syndrome? We have 56 million Americans with disabilities, so one out of five Americans. The disability experience is something many Americans live with.

Some Hollywood diversity consultants see their job as a challenging balance between education and accountability

There may be a variety of reasons that people reach out to [Color of Change], but a lot of this is about building relationships and trust and then having enough honesty on our part to say, “Just because we give you advice doesn’t mean we’re going to like the outcome.” It’s getting people to understand that the content they put out doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

GLAAD is the organization that literally started tracking the characters, the representation, the kinds of portrayals we were seeing, and reporting that publicly, so that the industry was being held responsible.

It’s one thing to know something, but to see it in writing and reported in the media I think awakens the industry to a different level of consciousness. So not only do they want to do better because it’s the right thing to do, but they want to do better because there can be consequences if they don’t.

Changes are happening, but not in the same way or at the same pace for everyone

[RespectAbility] just did a focus group in Hollywood, and these folks said when they’re casting, they now know that if they’re going to have four stars of a show, one needs to be nonwhite. But they are hesitant to have that person have a disability because they feel that it’s a stigma. But why can’t a person with a disability be a black person who has the most talent in the room? Disability means you can’t do Thing A, but it doesn’t mean you’re not the best in the world at Thing B. The stigma is [harming] employers’ willingness to hire people. Ninety-five percent of the time [that] there is a character with disabilities onscreen, they are played by an actor without that disability.

Many issues don’t come up as issues of religion until the story is actually about religion. Much of what else we see on television — actors and storylines — are about white, even black, Americans, and we just assume they’re from the Christian background.

Otherwise, [religion is] nearly always in the context of a violent incident. Why can so few people name a single incident on TV or film where a Muslim, Hindu, or several other devout practitioners of their faith laughs so hard he or she cries?

Honestly, there hasn’t been a huge shift yet with writers and executives wanting to portray a more diverse and accurate depiction of immigrants. What we have seen is a desire for more intersectionality, which naturally results in more diverse characters.

As we increase the quantity [of representations], it also raises the bar on quality and that requires content creators to be much more surgical. It’s one thing to be a straight white person who is creating a woman of color on their show, who finds a queer woman of color to talk to about this, but what are we doing as an industry to empower queer women of color to tell their own stories, to create their own content, to have access to writers’ rooms and a career path in the industry?

One of the shifts that I’ve seen is that with black showrunners ... there’s been a wider range of portrayal and a wider range of stories about the black experience. I still don’t think we see enough economically challenged people on television, and I feel like this has been a trend across race that we’ve seen. I think not having stories featuring people who are economically challenged adds to the lack of empathy that we have for the challenges people are having.

Most Popular

- There’s a fix for AI-generated essays. Why aren’t we using it?

- Did Brittany Mahomes’s Donald Trump support put her on the outs with Taylor Swift?

- The hidden reason why your power bill is so high

- I can’t take care of all my mom’s needs. Am I a monster?

- Conservatives are shocked — shocked! — that Tucker Carlson is soft on Nazis

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Culture

The DOJ says Tim Pool, Dave Rubin, Benny Johnson and others were unwitting Russian stooges.

Inside Gen Alpha’s relationship with tech.

The Bachelorette finale was riveting TV — and unfathomably cruel.

How China’s first global gaming blockbuster became a weird rallying point for the right.

Jennifer Lopez’s and Ben Affleck’s reactions to their split are both very on-brand and kind of pointless.

The back-and-forth over a wildly rare appeal is a win for victim’s rights.

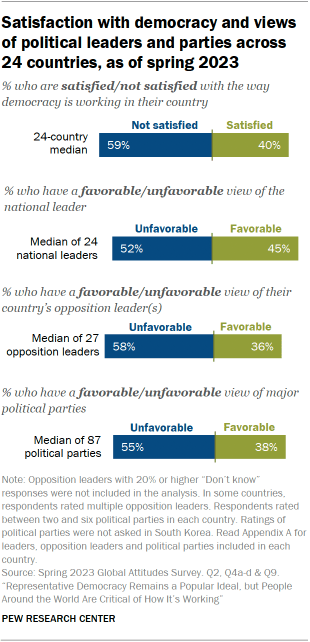

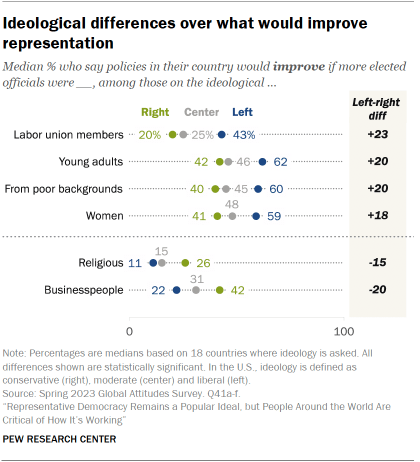

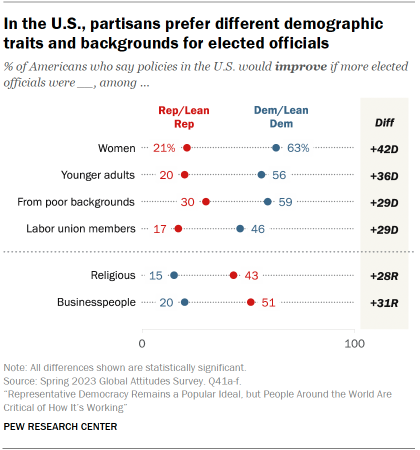

Why Representation in Politics Actually Matters

At this week's presidential debate, both serious contenders left in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination made a historic pronouncement. Former Vice President Joe Biden committed to choosing a woman as his running mate, while Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders said that, "in all likelihood," he would do the same. Online, where most of the discussion currently resides because of the global coronavirus outbreak , reaction to the candidates pledge was mixed. For some who hoped, after four years with an avowed misogynist in the Oval Office, that a woman would be the one to deliver the country from President Donald Trump, the promise was welcome , especially now that the contest has dwindled down to two old, white, straight men. Others saw the gesture as the hollow homogenization of over half the population — just one thing to consider amid other critical criteria upon which to evaluate a future presidential nominee.

But having women in politics — and more broadly, having representation across all identities of race, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status — has tangible effects on the health and functioning of democracy, political scientists told Teen Vogue . Indeed, the body of research showing the value of having women run for and attain political office is rich and growing.

The first argument for the equal inclusion of women, and all identities present in America, is basic fairness, says Kelly Dittmar, assistant professor of political science at Rutgers University–Camden and scholar at the Rutgers Center for American Women and Politics. “If the system is meant to be a representative democracy, then it should be representative of the many populations it serves, and that includes women.”

Despite the significant gains in the 2018 midterms , women are still woefully underrepresented in American politics. As it stands , women occupy 127 of the 535 seats in the U.S. Congress, or 23.7% of power. For statewide executive offices and state legislatures, the share for women is only slightly better, hovering around 30%. The global average for women’s representation in government is 24.5%, according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union , which places the U.S. 82nd of 189 countries on this metric.

“Having women and people of color in political office is beneficial because it’s a sign our political system is open and that everybody can participate no matter their position,” Christina Wolbrecht, professor of political science and director of the Rooney Center for the Study of American Democracy at Notre Dame University, told Teen Vogue . If equal democracy is a sign of democratic openness, then our paltry representation of women, and especially women of color , shows American democracy is not an accessible — or healthy — system.

For many, Warren’s exit spawned such a flood of frustration because it reinforced this exact idea, said Mirya Holman, associate professor of political science at Tulane University. “The way she dropped out with a lot of people being supportive , but that not translating into actual votes, reminds people the system is not actually all that open or welcoming to women,” Holman told Teen Vogue .

Setting fairness aside, women are vital to American politics because they bring symbolic power that comes with a cascade of benefits for democracy. Put simply, “It matters because you cannot be what you cannot see,” Jennifer Piscopo, associate professor of politics at Occidental College, told Teen Vogue . Increasing the number of women in political leadership makes it more likely young women and men will see women as both capable of and an equally natural fit for public leadership , Dittmar, the Rutgers professor, pointed out. “This starts to disrupt what has been a white male dominance in American politics, and that is especially true at the presidential level where no woman has served,” she added.

Symbolic representation also provides the crucial ingredient of trust needed for the successful relationship between the governors and governed in any democratic society. In 2016, Piscopo and her research partners Amanda Clayton of Vanderbilt University and Diana O’Brien of Indiana University ran a series of survey experiments asking Americans to read fictitious articles about state legislative committees with varying levels of gender balance that were evaluating sexual harassment policies. The findings showed a resounding rejection of all-male panels that decided to decrease penalties for sexual harassers, with respondents saying they were less likely to agree with the outcome, more likely to believe the process was unfair and the decision should be overturned, and less trustful of the overall results. “When the folks in office are more diverse and gender-balanced we see people have more trust in government and participate in politics more. The paradox is all these stereotypes make it hard for women to get into office in the first place,” Piscopo told Teen Vogue .

Recent research from Wolbrecht and fellow Notre Dame University professor David Cambell also confirms the relationship between representation and trust in government, especially among girls. Based on a national sample of 997 American teenagers, ages 15–18, administered in the fall of 2016 before the election, and then again in 2017, Wolbrecht and Cambell found a drastic decline in how girls, especially those identifying as Democrats, viewed the state of American democracy. In 2016, 37% of Democratic girls thought politics helped meet their needs. A year later that belief had dropped by 20 percentage points.

But when these same teens were interviewed again in 2018, Democratic girls’ trust in democracy rebounded back to 30%, a result Wolbrecht and Campbell credit to the historic number of women who ran in the 2018 midterm elections. Increased faith in politics was especially pronounced among Democratic girls who lived in places where one or more women ran for the U.S. House, Senate, or governor. On the other hand, the trust remained stagnant in areas where there were no women candidates.

This “role model effect” is important not only for trust in government, but also for another critical element of democracy: civic engagement. As Wolbrecht and Cambell write, young women tend to become more politically engaged when they see women engaging in visible, viable campaigns, a finding bolstered by research from Tiffany Barnes, an associate professor of political science at the University of Kentucky. Using data from 20 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Barnes discovered a direct relationship between women’s representation and political engagement. “Having more women in office, and in visible political positions, is associated with more women engaging in activities like protest or talking about politics, and contacting a representative more frequently,” Barnes told Teen Vogue.

On a substantive policy level, the evidence shows women’s legislative effectiveness is greater than men’s. And although the backgrounds of women are far from monolithic, women overall bring different, valuable perspectives to the currently male-dominated process, Dittmar said. “We value the experience of someone who has had military experience or lived abroad, so, why wouldn’t we value the distinct experience women have in society?”

Want more from Teen Vogue ? Check this out: Elizabeth Warren Never Stood a Chance

Stay up-to-date on the 2020 election. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take !

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

representation

Definition of representation

Examples of representation in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'representation.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Phrases Containing representation

- proportional representation

- self - representation

Dictionary Entries Near representation

representant

representationalism

Cite this Entry

“Representation.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/representation. Accessed 9 Sep. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of representation, legal definition, legal definition of representation, more from merriam-webster on representation.

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for representation

Nglish: Translation of representation for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of representation for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about representation

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, 31 useful rhetorical devices, more commonly misspelled words, absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, 7 shakespearean insults to make life more interesting, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

The power of political representation

Lisa Jane Disch, Making Constituencies: Representation as Mobilization in Mass Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021)

- Critical Exchange

- Open access

- Published: 16 December 2023

- Volume 23 , pages 456–484, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lawrence Hamilton 1 , 2 ,

- Monica Brito Vieira 3 ,

- Lisa Disch 4 ,

- Lasse Thomassen 5 &

- Nadia Urbinati 6

2926 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This Critical Exchange takes up a conversation David Plotke inaugurated twenty-five years ago with this simple statement: ‘Representation is democracy’ ( 1997 ). This sentence announced a unique and powerful reframing that ‘transformed what was commonly believed to be an oxymoron into an equivalence’, as Mónica Brito Vieira so aptly and eloquently described it ( 2017 , p. 6). Rather than promote representation from the typical standpoint of republicanism, Plotke took up a vantage point informed by and grateful for the successes of twentieth-century democratic movements. By extending voice and rights to the formerly marginalized and replacing ‘direct personal domination’ and favoritism with abstract rules and procedures, he argued, democratic movements made ‘politics more complex and less direct’ (Plotke., 1997 , p. 24). Increased complexity gave representation ‘a central positive role in democratic politics’, making it an outcome and ally of democracy rather than ‘an unfortunate compromise between an ideal of direct democracy and messy modern realities’ (Plotke, 1997 , p. 24).

That same year, Iris Marion Young also questioned the privilege accorded to ‘direct democracy’, arguing that directness betrays ideals of equality, mutuality, and accountability wherever face-to-face gatherings cede power to ‘arrogant loud mouths whom no one chose to represent them’ (Young, 1997 , p. 353). Her words affirmed Jane J. Mansbridge’s classic study, published twenty years earlier, which documented how town hall governance brings out deep-seated habits of deference to gender- and race-based hierarchies ( 1980 ). These works proved harbingers of what Nadia Urbinati termed the ‘democratic rediscovery of representation’ that took hold in the early 2000s and challenged the ‘standard model’ of representative politics (Urbinati, 2006 , p. 5; Castiglione & Warren, 2019 , p. 22).

The standard model focuses on elections. It conceives of democratic representation as a principal-agent relationship that is territorially based, located within constitutionally sanctioned institutions of political decision-making, and the source for ‘a simple means and measure of political equality’: the vote (Castiglione & Warren, 2019 , p. 21). Accordingly, representative institutions are democratic insofar as they ensure responsiveness to the ‘interests and opinions of the people constituted by territorial membership’ (Castiglione & Warren, 2019 , p. 21). Due to the proliferation of transnational and subnational practices of representation and the generation of economic and ecological externalities that confound territorial boundaries, twenty-first-century globalization created a ‘disjunction’ between model and practice that provided one catalyst for the turn toward representation in democratic theory (Urbinati & Warren, 2008 , p. 388).

New forms of political action gave scholars an even more powerful catalyst. Various experiments defied the traditional opposition between participatory and representative governance: ‘citizen juries, consensus conferences, planning cells’ (Brown, 2006 , p. 203); ‘accountable autonomy’ in community policing and school budgeting (Fung, 2004 , p. 6); sortition (Sintomer, 2011 , 2023 ). Scholars proposed new categories to conceptualize this activity—’informal’, ‘lay’, and ‘self-appointed’ representation (Montanaro, 2012 , 2017 ; Warren, 2008 ). Scholars also transformed the practice of democratic theory, plumbing historical instances where representative and democratic practices conjoined (Hayat) and working the intersection between normative and empirical research (Hawkesworth, 2003 ; Mansbridge, 2003 , 2009 ; Sabl, 2015 ).

The ‘representative turn’ stood out for its proponents’ ‘willingness to question the polarity of representation and democracy’ (Brito Vieira, 2017 , p. 5). They emphasized that representative functions can be fulfilled by a broad variety of non-electoral political actors including social movements, organizations, individual citizens, and influential media figures. They also maintained that political representation ‘does not simply allow the social to be translated into the political, but also facilitates the formation of political groups and identities’ (Urbinati, 2006 , p. 37; Brito Vieira and Runciman, 2008 ; Brito Vieira, 2009 ; Schwartz, 1998 ; Thomassen, 2019 ; Young, 1997 ). Above all, their work made it clear that Hanna Fenichel Pitkin’s classic definition of representation as the ‘making present in some sense of something which is nevertheless not present literally or in fact’ needed amending (Pitkin, 1967 , pp. 8, 9; emphasis original). These theorists, proponents of a ‘constructivist’ variant on the representative turn, emphasized making the represented and its interests over making them present (Disch, 2011 ; Hayward, 2009 ).

Michael Saward’s conceptualization of representation as claims-making provided an especially influential framework for analyzing this ‘performativity’ in both the speech act sense (as constitutive) and the theatrical sense (as performance) (Saward, 2014 , p. 725). He trained analysts’ attention on the work that would-be representatives do to ‘make representations’ of their constituents, by soliciting the ‘latter to recognize themselves’ in the portraits created by claims, policies, and other acts of representation (Saward, 2014 , p. 726; 2006 , 2010 ). He and others explored ‘representation’s aesthetic and cultural character’ (Saward, 2014 , p. 726) in the thought of Thomas Hobbes (Brito Vieira, 2009 ), in ‘enactments’ of race and gender through Congressional welfare reform (Hawkesworth, 2003 ), and in an array of staged public appearances (Salmon, 2010 ; Finlayson, 2021 ; Spary, 2021 ). Shirin Rai developed a ‘political performance framework’ that breaks political performances into their ‘component parts’ to identify the ‘materiality of performance’ and to analyze ‘why and how some performances mark a rupture in the everyday reproduction of social relations’ while others reproduce those relations (Rai, 2015 , pp. 1180, 1181). Laura Montanaro specified the category of ‘self-appointed’ representatives—charismatic individuals and organized advocacy groups who claim to speak for constituencies and are recognized as doing so even though they are neither elected nor appointed—and proposed normative criteria for assessing when they serve democracy and when they do not ( 2017 ).

This new work focused an urgent concern: ‘if representative politics is performative, how can we ensure that it is also democratic?’ (Thomassen in this Critical Exchange). By recognizing that political representation happens outside constitutionally sanctioned liberal democratic institutions and acknowledging its performativity, this work neutralized traditional election-based yardsticks for assessing its democratic legitimacy: authorization by and responsiveness to a geographically specified constituency.

It also provoked astute objections. Sophia Näsström observes an ambiguity about this work’s ‘diagnostic or normative’ aims ( 2011 , p. 502). Noting the pronounced asymmetries of voice in the non-electoral domain of global politics that favor the wealthy, she cautions that the emphasis on non-electoral representation may ‘serve as a warning of what may lie ahead, as a call for democratic theorists to rethink numerical equality beyond election’, or provide a ‘subtle’ means of acclimating people to the ‘idea that there may be acceptable forms of global representative government without democracy’ ( 2011 , p. 508). Jennifer Rubenstein similarly objects that the activities of global non-governmental organizations are not and do not claim to be acts of representation; they are exercises of power that should be analyzed as such rather than through a ‘representation lens’ ( 2007 , p. 208). Andrew Rehfeld ( 2017 ) pointedly observed that for all the new attention to representation, scholars failed to ask the simplest of questions: What is a representative and how does one come to be one?

Lisa Disch’s Making Constituencies emerges from the representative turn in democratic theory and is inspired by a specific problem: What are empirical researchers to make of the fact that they can affirm citizens’ capacity for preference-formation only at the cost of revealing their susceptibility to the self-seeking rhetoric of competing elites? This question originates from a reconsideration of early survey research that called traditional yardsticks of representative democracy into question long before democratic theorists made the turn. In 1964, Philip Converse famously debunked both responsiveness and accountability, arguing that voters offer little in the way of consistent beliefs or coherent ideologies for representatives to respond to and that they pay too little attention to politics to hold their representatives to account. Today, empirical scholars find that individuals in mass democracies do form political opinions, preferences, and identities but in response to political contexts rather than prior to them (see, for example, Carmines & Kuklinski, 1990 ; Lupia, 1992 , 1994 ; Druckman, 2001 ).

Making Constituencies emphasizes that empirical researchers offer distinct accounts of political learning processes that reach significantly different conclusions regarding the viability of representative democracy. One account holds that humans adapt their opinions and preferences to antagonistic group affiliations which they are psychologically disposed to form (Achen & Bartels, 2016 ; Iyengar et al., 2012 ). The other posts a political divide emerging in response to increasing polarization among political elites (Abrams & Fiorina, 2012 ; Levendusky, 2009 ). These accounts bear on the widely cited phenomenon of ‘sorting’, popularly known as the antagonistic division into partisan camps that pundits lament for rendering mass democracies increasingly ungovernable. The first account depoliticizes sorting by depicting it as a fact or state grounded in human psychology; the second treats it as a portrait of the political landscape—a representation. Rather than reflect a deep-seated partisan cleavage, talk of sorting, studies of sorting, and strategies designed to exploit it participate in constituting that antagonistic divide.

Despite the influence of the psychological account, empirical research frequently supports the political explanation. Recall the intractable partisan differences that were said to have influenced states’ pandemic-related regulations regarding masks and quarantine in the United States and people’s responses to those regulations. Sorting influenced how people understood and experienced the pandemic. Residents of blue [i.e. Democrat] states and/or counties blamed red-state [i.e. Republican] policy and the reckless actions of red-state residents for accelerating both the spread of the pandemic and the propagation of new variants.

Lessons from the Covid War: An Investigative Report ( 2023 ) re-examines this narrative, highlighting the ‘great untold story’ that it was ‘common’ during the first months of the pandemic ‘to find selfless cooperation, people sharing best practices and regularly supporting one another across state lines and all political persuasions’ ( 2023 , p. 150). Only as the pandemic wore on, and the 2020 presidential election approached, did policy and behavior with respect to masking, social-distancing, and—ultimately—vaccine mandates exhibit partisan antagonism. The authors emphasize:

…there is a common view that politics, a ‘[r]ed response’ and a ‘blue response’, were the main obstacle to protecting citizens, not competence and policy failures. We found, instead, that it was more the other way around. Incompetence and policy failures, including the failure of federal executive leadership, produced bad outcomes, flying blind, and resorting to blunt instruments. Those failures and tensions fed toxic politics that further divided the country in a crisis rather than bringing it together ( 2023 , p. 151).

Spotlighting this key paragraph, David Wallace-Wells observes that ‘the partisanship of our pandemic response was not a pre-existing condition…[but] was, at least partly, a result of that response’ ( 2023 ). Applied to the pandemic, the sorting narrative entrenched the condition that its subscribers lament—a country cleaved by antagonistic partisanship and unable to cooperate to achieve clear public goods.

I wrote Making Constituencies to better align our ideals of representative democracy with empirical findings about how it works in practice. This required displacing representative democracy from its (mythical) ground in the ‘bedrock’ of voter preferences—the constructivist turn (Disch, 2011 ). The intuition driving the book is that the constructivist turn has the potential to shore up rather than undermine mass democracy. If representative democracy is at its best when representatives of all kinds—elected officials, opinion-shapers, advocacy groups, and more—build creative and unlikely coalitions, perhaps the turn to constructivism inspires optimism about those agents’ ability to do just that. The generative and perceptive essays that follow offer a wealth of insight into where democratic theory is moving today, particularly in western democracies. They also persuade me that my book gave too little consideration to an important element of this vision: political judgment and the political conditions that foster and distort it in mass publics.

An excellent introduction to a great absent

The constructivist conception of political representation allows Disch to advance two very important arguments, which are the pillars of this excellent book: the vindication of critical realism, and its distinction from what I would call ‘simplistic’ realism. The former inspires a theoretical and practical attitude that is supportive of democracy, while the latter fosters a pessimistic and skeptical, if not overtly critical, attitude toward it. This dualism leads us directly to the topics that have divided scholars of democracy since time immemorial: the role of competence and, indeed, of the competent in political decision-making, and a negative assessment of the role of political parties. While Disch comprehensively covers the former, she leaves out the latter.

Political theorists are well acquainted with Disch’s work, which over the years has become a valuable contribution to the theory of representation as ‘claim-making’—a constructivist approach that corrects the formalist reading and connects representation with participation rather than only voting and institutions. The enormous implications of the constructivist turn have not yet been fully appreciated. They concern the understanding of politics, the role of conflict as constitutive of democratic politics and political freedom, and the inclination of democratic theory toward critical realism. Critical realism is a guide to decoding the factors that determine the formation of citizens’ reasons for their political choices, without falling into moralism and pedagogical paternalism, or alternatively justifying the status quo.

Representation entails the construction of constituencies. The latter give unity to the claims and problems that bring us into the political arena, shape the linguistic frame that conveys to others our reasons and goals—they represent us to our fellow citizens and the audience. Organizational strategies are essential to the making of the several roles and actors that comprise the collective work of representation, which is in all respects a process of participation through which citizens construct their political identities (movements and parties) and goals, and seek and acquire the power to determine the direction of the government of their society; in doing all of that citizens construct ties among each other and side for or against other constituencies. Representation is the name of a form of participation, whose Latin root means two things at once: taking sides and taking part.

Disch brilliantly sketches the process through which this conception of representation emerged: a long journey that began with Pitkin’s seminal 1967 book, which took representation out of the corner to which behaviorist and elitist theories of democracy had confined it, albeit at the cost of emphasizing its formalistic character. ‘Pitkin modified interest representation in several radical ways. She redefined democratic representation from an interpersonal relationship to an anonymous and impersonal’ or formal system process (p. 38). While elitist theory emphasized the individual-to-individual relationship (between the represented and the representatives) and the role of individual preferences and interests—a perspective that is still predominant in political science—Pitkin unpacked representation in relation to the form of the mandate and ascribed relevance to the moment of ‘acting for’. This choice opened the way to issues of advocacy and leadership, and fatally to those of manipulation and ideological constructions. However, although Pitkin did not make the representative claim bi-directional, and insisted on the formalist moment to detract from the plebiscitary or demagogic strategy, she nevertheless opened the way for the active role of citizens, both as respondents and as creators of leaders. Mansbridge refined that trajectory in relation to the deliberative system, proposing the idea of anticipatory representation linked to and in fact promoted by retrospective voting. Disch writes that this move pushed Mansbridge ‘into the constituency paradox’ and into the tension between ‘manipulation’ and ‘education’ that characterizes representative democracy. Disch’s critical work is situated within this ‘paradox’ but with a view to its solution, foregoing the need to identify ‘criteria for distinguishing between persuasion and manipulations’ (p. 45).

Based on the constructivist turn, Disch mounts an assault on contemporary realists, notably Christopher H. Achen, Larry M. Bartel and Jason Brennan, who in fact are anything but realists insofar as they judge citizens’ decisions (election results) on the basis of an idea of ‘competent’ decision-making that claims authority over citizens’ judgment and decision. But, Disch suggests, understanding how and why citizens voted for this or that candidate is not the same as staging a court of law to pass a verdict on them. Contemporary realists rely on a psychological approach in analyzing preferences and beliefs; this individualistic poll-based method leads them to conclude that ignorance is the structural flaw that elections generate, a flaw that can only be contained but never erased. The prescription is predictable: democracy is to be saved from itself by narrowing the role of suffrage in two ways: expanding the role of the competent (Achen and Bartel) or limiting the right to vote to those who pass an exam (Brennan).

These realists argue that the psychological need of individuals to bond with a group is like an instinctive force toward belonging, a kind of ‘primordialism’. It could be said that the more competent and intellectually sharp we are, the more we can reason apart from a group or an instinctive need to belong. The more rational we are, the more individualistic we are, and the more competent we are as citizens—a condition that is of the few, not the many. According to these realists, therefore, any grouping is a sign of ignorance and intellectual laziness. They draw on Gustave Le Bon and Gabriel Tarde, who wrote before democracy raised the fear of the (blind, irrational, emotional and reactive) masses that demagogues conquer. The distrust of contemporary realists mimics Robert Michels’ point that individual citizens need to associate to resolve their weakness, with the paradoxical consequence that association brings them into the arms of an oligarchy and makes them dependent on partisan views.

This simplistic realism is certainly not conducive to representative democracy. As Disch shows, it is the child of behaviorism and a negative conception of politics. It has a pessimistic attitude that is difficult to substantiate, even if very pronounced. Simplistic realism identifies citizenship with voting, and representation with recording individual preferences, and reads preferences as emotional reactions to a world that ordinary citizens have no means of knowing or are not interested in knowing. How can we address this ideological construct that claims to be an objective account of reality?

The most important contribution of Disch’s book lies in offering an answer to this question. Disch responds to realist critics, not by rejecting realism but by reinterpreting it. She argues, very persuasively, that realism is not identifiable with the empirical investigation of individual opinions that assigns a central role to researchers and assumes that citizens are simply reactive; an approach, as we have seen, that draws on crowd psychology. The interdisciplinary approach proposed by the critical realism Disch advocates assumes that political judgments (the reasons for citizens’ decisions) occur within a structural social context. Citizens develop their representative claims and, thus, their electoral choices within reflections on a range of considerations of governmental choices, social and economic conditions, and confrontations between different parts of society. Therefore, we should not blame the ignorance of citizens but the presumption of political scientists, who reduce political judgment to a matter of individual psychological reactions that discard ex ante social relations.

Disch masterfully sketches two realisms by opposing to the one exemplified by Achen, Bartel and Brennan a realism exemplified by Katherine J. Cramer and Suzanne Mettler. The latter is the child of a socio-economic structural analysis of the environment in which people form their beliefs, develop their reasons for making decisions, and eventually organize. For simplistic realism, politics has the defect of being a domain in which opinions are manipulated and preferences are simply wrong, because they often are irrational responses to a reality that eludes citizens. For critical realism, politics is the complex art of interpretation and action, a kind of knowledge that aims at ‘effectuality’ and is pragmatically action-oriented. To understand how citizens opine and decide, we must rely on various disciplines and interrogate the relationship between institutions, leaders, and constituencies.

Based on critical realism, Disch takes an important step outside the demarcation drawn by Mansbridge between manipulation and education, partisan politics and reasonable deliberation. Disch goes to the source of political scientists’ distrust of power. ‘To accept that political speech moves people as much or more than it educates them is to acknowledge the irreducible “ambiguities” of manipulation as a concept’ (p. 94), because indeed the result might be that any form of consensus-seeking persuasion is a form of manipulation. Yet if this were the case what would be the role of elections, party pluralism, and conflict to achieve consensus and govern?

The train of ideas that leads Disch to place the theory of democracy within critical realism is represented by some prominent figures: Elmer E. Schattschneider (for his theory of the contagiousness of conflict and the tension between vested interests and political interests), Robert Goodin (for his critique of the fear of manipulation as a fear of ‘competitive political rhetoric’), Claude Lefort (for bringing the theory of power back to its Machiavellian roots as ‘empty space’ and the choral and individual work of contestation in free (democratic) societies), and Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe (for bringing antagonism and hegemonic articulation of claims into representative politics). These are Disch’s coordinates for thinking democracy as a place of ‘plurality’ and struggle against hierarchy, thus rejecting plurality as made up of groups ‘out there’. Disch argues that, ‘Thinking democracy means thinking of it as plural in this precise sense’ (p. 140).

I fully share Disch’s views about critical realism and pluralism. Her argument is strong, persuasive, and very important. However, I think her position needs a complement to address two issues that are absent in her critical realism. The first issue pertains to ‘antagonism’ as ‘sharp conflict’ that ‘forces decisions on fundamental, often zero-sum issues’ (p. 139). The examples Disch proposes are foundational ‘yes’ or ‘no’ issues as the basic thresholds of democracy: issues of slavery or equal rights, for instance. This kind of ‘zero sum’ antagonism does not, however, seem to qualify ordinary party politics (not even in a two-party system). Not all politics can be antagonistic in this foundational sense if democratic conflict is to be distinguished from civil war. Does Disch distinguish between foundational antagonism and ordinary conflict politics?