Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 13 March 2018

Does playing violent video games cause aggression? A longitudinal intervention study

- Simone Kühn 1 , 2 ,

- Dimitrij Tycho Kugler 2 ,

- Katharina Schmalen 1 ,

- Markus Weichenberger 1 ,

- Charlotte Witt 1 &

- Jürgen Gallinat 2

Molecular Psychiatry volume 24 , pages 1220–1234 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

557k Accesses

110 Citations

2349 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroscience

It is a widespread concern that violent video games promote aggression, reduce pro-social behaviour, increase impulsivity and interfere with cognition as well as mood in its players. Previous experimental studies have focussed on short-term effects of violent video gameplay on aggression, yet there are reasons to believe that these effects are mostly the result of priming. In contrast, the present study is the first to investigate the effects of long-term violent video gameplay using a large battery of tests spanning questionnaires, behavioural measures of aggression, sexist attitudes, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), mental health (depressivity, anxiety) as well as executive control functions, before and after 2 months of gameplay. Our participants played the violent video game Grand Theft Auto V, the non-violent video game The Sims 3 or no game at all for 2 months on a daily basis. No significant changes were observed, neither when comparing the group playing a violent video game to a group playing a non-violent game, nor to a passive control group. Also, no effects were observed between baseline and posttest directly after the intervention, nor between baseline and a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention period had ended. The present results thus provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games in adults and will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective on the effects of violent video gaming.

Similar content being viewed by others

The associations between autistic characteristics and microtransaction spending

No effect of short term exposure to gambling like reward systems on post game risk taking

Increasing prosocial behavior and decreasing selfishness in the lab and everyday life

The concern that violent video games may promote aggression or reduce empathy in its players is pervasive and given the popularity of these games their psychological impact is an urgent issue for society at large. Contrary to the custom, this topic has also been passionately debated in the scientific literature. One research camp has strongly argued that violent video games increase aggression in its players [ 1 , 2 ], whereas the other camp [ 3 , 4 ] repeatedly concluded that the effects are minimal at best, if not absent. Importantly, it appears that these fundamental inconsistencies cannot be attributed to differences in research methodology since even meta-analyses, with the goal to integrate the results of all prior studies on the topic of aggression caused by video games led to disparate conclusions [ 2 , 3 ]. These meta-analyses had a strong focus on children, and one of them [ 2 ] reported a marginal age effect suggesting that children might be even more susceptible to violent video game effects.

To unravel this topic of research, we designed a randomised controlled trial on adults to draw causal conclusions on the influence of video games on aggression. At present, almost all experimental studies targeting the effects of violent video games on aggression and/or empathy focussed on the effects of short-term video gameplay. In these studies the duration for which participants were instructed to play the games ranged from 4 min to maximally 2 h (mean = 22 min, median = 15 min, when considering all experimental studies reviewed in two of the recent major meta-analyses in the field [ 3 , 5 ]) and most frequently the effects of video gaming have been tested directly after gameplay.

It has been suggested that the effects of studies focussing on consequences of short-term video gameplay (mostly conducted on college student populations) are mainly the result of priming effects, meaning that exposure to violent content increases the accessibility of aggressive thoughts and affect when participants are in the immediate situation [ 6 ]. However, above and beyond this the General Aggression Model (GAM, [ 7 ]) assumes that repeatedly primed thoughts and feelings influence the perception of ongoing events and therewith elicits aggressive behaviour as a long-term effect. We think that priming effects are interesting and worthwhile exploring, but in contrast to the notion of the GAM our reading of the literature is that priming effects are short-lived (suggested to only last for <5 min and may potentially reverse after that time [ 8 ]). Priming effects should therefore only play a role in very close temporal proximity to gameplay. Moreover, there are a multitude of studies on college students that have failed to replicate priming effects [ 9 , 10 , 11 ] and associated predictions of the so-called GAM such as a desensitisation against violent content [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] in adolescents and college students or a decrease of empathy [ 15 ] and pro-social behaviour [ 16 , 17 ] as a result of playing violent video games.

However, in our view the question that society is actually interested in is not: “Are people more aggressive after having played violent video games for a few minutes? And are these people more aggressive minutes after gameplay ended?”, but rather “What are the effects of frequent, habitual violent video game playing? And for how long do these effects persist (not in the range of minutes but rather weeks and months)?” For this reason studies are needed in which participants are trained over longer periods of time, tested after a longer delay after acute playing and tested with broader batteries assessing aggression but also other relevant domains such as empathy as well as mood and cognition. Moreover, long-term follow-up assessments are needed to demonstrate long-term effects of frequent violent video gameplay. To fill this gap, we set out to expose adult participants to two different types of video games for a period of 2 months and investigate changes in measures of various constructs of interest at least one day after the last gaming session and test them once more 2 months after the end of the gameplay intervention. In contrast to the GAM, we hypothesised no increases of aggression or decreases in pro-social behaviour even after long-term exposure to a violent video game due to our reasoning that priming effects of violent video games are short-lived and should therefore not influence measures of aggression if they are not measured directly after acute gaming. In the present study, we assessed potential changes in the following domains: behavioural as well as questionnaire measures of aggression, empathy and interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs (such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness, risk taking, delay discounting), and depressivity and anxiety as well as executive control functions. As the effects on aggression and pro-social behaviour were the core targets of the present study, we implemented multiple tests for these domains. This broad range of domains with its wide coverage and the longitudinal nature of the study design enabled us to draw more general conclusions regarding the causal effects of violent video games.

Materials and methods

Participants.

Ninety healthy participants (mean age = 28 years, SD = 7.3, range: 18–45, 48 females) were recruited by means of flyers and internet advertisements. The sample consisted of college students as well as of participants from the general community. The advertisement mentioned that we were recruiting for a longitudinal study on video gaming, but did not mention that we would offer an intervention or that we were expecting training effects. Participants were randomly assigned to the three groups ruling out self-selection effects. The sample size was based on estimates from a previous study with a similar design [ 18 ]. After complete description of the study, the participants’ informed written consent was obtained. The local ethics committee of the Charité University Clinic, Germany, approved of the study. We included participants that reported little, preferably no video game usage in the past 6 months (none of the participants ever played the game Grand Theft Auto V (GTA) or Sims 3 in any of its versions before). We excluded participants with psychological or neurological problems. The participants received financial compensation for the testing sessions (200 Euros) and performance-dependent additional payment for two behavioural tasks detailed below, but received no money for the training itself.

Training procedure

The violent video game group (5 participants dropped out between pre- and posttest, resulting in a group of n = 25, mean age = 26.6 years, SD = 6.0, 14 females) played the game Grand Theft Auto V on a Playstation 3 console over a period of 8 weeks. The active control group played the non-violent video game Sims 3 on the same console (6 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 24, mean age = 25.8 years, SD = 6.8, 12 females). The passive control group (2 participants dropped out, resulting in a group of n = 28, mean age = 30.9 years, SD = 8.4, 12 females) was not given a gaming console and had no task but underwent the same testing procedure as the two other groups. The passive control group was not aware of the fact that they were part of a control group to prevent self-training attempts. The experimenters testing the participants were blind to group membership, but we were unable to prevent participants from talking about the game during testing, which in some cases lead to an unblinding of experimental condition. Both training groups were instructed to play the game for at least 30 min a day. Participants were only reimbursed for the sessions in which they came to the lab. Our previous research suggests that the perceived fun in gaming was positively associated with training outcome [ 18 ] and we speculated that enforcing training sessions through payment would impair motivation and thus diminish the potential effect of the intervention. Participants underwent a testing session before (baseline) and after the training period of 2 months (posttest 1) as well as a follow-up testing sessions 2 months after the training period (posttest 2).

Grand Theft Auto V (GTA)

GTA is an action-adventure video game situated in a fictional highly violent game world in which players are rewarded for their use of violence as a means to advance in the game. The single-player story follows three criminals and their efforts to commit heists while under pressure from a government agency. The gameplay focuses on an open world (sandbox game) where the player can choose between different behaviours. The game also allows the player to engage in various side activities, such as action-adventure, driving, third-person shooting, occasional role-playing, stealth and racing elements. The open world design lets players freely roam around the fictional world so that gamers could in principle decide not to commit violent acts.

The Sims 3 (Sims)

Sims is a life simulation game and also classified as a sandbox game because it lacks clearly defined goals. The player creates virtual individuals called “Sims”, and customises their appearance, their personalities and places them in a home, directs their moods, satisfies their desires and accompanies them in their daily activities and by becoming part of a social network. It offers opportunities, which the player may choose to pursue or to refuse, similar as GTA but is generally considered as a pro-social and clearly non-violent game.

Assessment battery

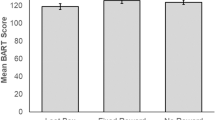

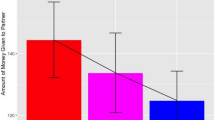

To assess aggression and associated constructs we used the following questionnaires: Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire [ 19 ], State Hostility Scale [ 20 ], Updated Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale [ 21 , 22 ], Moral Disengagement Scale [ 23 , 24 ], the Rosenzweig Picture Frustration Test [ 25 , 26 ] and a so-called World View Measure [ 27 ]. All of these measures have previously been used in research investigating the effects of violent video gameplay, however, the first two most prominently. Additionally, behavioural measures of aggression were used: a Word Completion Task, a Lexical Decision Task [ 28 ] and the Delay frustration task [ 29 ] (an inter-correlation matrix is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1 1). From these behavioural measures, the first two were previously used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay. To assess variables that have been related to the construct of impulsivity, we used the Brief Sensation Seeking Scale [ 30 ] and the Boredom Propensity Scale [ 31 ] as well as tasks assessing risk taking and delay discounting behaviourally, namely the Balloon Analogue Risk Task [ 32 ] and a Delay-Discounting Task [ 33 ]. To quantify pro-social behaviour, we employed: Interpersonal Reactivity Index [ 34 ] (frequently used in research on the effects of violent video gameplay), Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale [ 35 ], Reading the Mind in the Eyes test [ 36 ], Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire [ 37 ] and Richardson Conflict Response Questionnaire [ 38 ]. To assess depressivity and anxiety, which has previously been associated with intense video game playing [ 39 ], we used Beck Depression Inventory [ 40 ] and State Trait Anxiety Inventory [ 41 ]. To characterise executive control function, we used a Stop Signal Task [ 42 ], a Multi-Source Interference Task [ 43 ] and a Task Switching Task [ 44 ] which have all been previously used to assess effects of video gameplay. More details on all instruments used can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Data analysis

On the basis of the research question whether violent video game playing enhances aggression and reduces empathy, the focus of the present analysis was on time by group interactions. We conducted these interaction analyses separately, comparing the violent video game group against the active control group (GTA vs. Sims) and separately against the passive control group (GTA vs. Controls) that did not receive any intervention and separately for the potential changes during the intervention period (baseline vs. posttest 1) and to test for potential long-term changes (baseline vs. posttest 2). We employed classical frequentist statistics running a repeated-measures ANOVA controlling for the covariates sex and age.

Since we collected 52 separate outcome variables and conduced four different tests with each (GTA vs. Sims, GTA vs. Controls, crossed with baseline vs. posttest 1, baseline vs. posttest 2), we had to conduct 52 × 4 = 208 frequentist statistical tests. Setting the alpha value to 0.05 means that by pure chance about 10.4 analyses should become significant. To account for this multiple testing problem and the associated alpha inflation, we conducted a Bonferroni correction. According to Bonferroni, the critical value for the entire set of n tests is set to an alpha value of 0.05 by taking alpha/ n = 0.00024.

Since the Bonferroni correction has sometimes been criticised as overly conservative, we conducted false discovery rate (FDR) correction [ 45 ]. FDR correction also determines adjusted p -values for each test, however, it controls only for the number of false discoveries in those tests that result in a discovery (namely a significant result).

Moreover, we tested for group differences at the baseline assessment using independent t -tests, since those may hamper the interpretation of significant interactions between group and time that we were primarily interested in.

Since the frequentist framework does not enable to evaluate whether the observed null effect of the hypothesised interaction is indicative of the absence of a relation between violent video gaming and our dependent variables, the amount of evidence in favour of the null hypothesis has been tested using a Bayesian framework. Within the Bayesian framework both the evidence in favour of the null and the alternative hypothesis are directly computed based on the observed data, giving rise to the possibility of comparing the two. We conducted Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVAs comparing the model in favour of the null and the model in favour of the alternative hypothesis resulting in a Bayes factor (BF) using Bayesian Information criteria [ 46 ]. The BF 01 suggests how much more likely the data is to occur under the null hypothesis. All analyses were performed using the JASP software package ( https://jasp-stats.org ).

Sex distribution in the present study did not differ across the groups ( χ 2 p -value > 0.414). However, due to the fact that differences between males and females have been observed in terms of aggression and empathy [ 47 ], we present analyses controlling for sex. Since our random assignment to the three groups did result in significant age differences between groups, with the passive control group being significantly older than the GTA ( t (51) = −2.10, p = 0.041) and the Sims group ( t (50) = −2.38, p = 0.021), we also controlled for age.

The participants in the violent video game group played on average 35 h and the non-violent video game group 32 h spread out across the 8 weeks interval (with no significant group difference p = 0.48).

To test whether participants assigned to the violent GTA game show emotional, cognitive and behavioural changes, we present the results of repeated-measure ANOVA time x group interaction analyses separately for GTA vs. Sims and GTA vs. Controls (Tables 1 – 3 ). Moreover, we split the analyses according to the time domain into effects from baseline assessment to posttest 1 (Table 2 ) and effects from baseline assessment to posttest 2 (Table 3 ) to capture more long-lasting or evolving effects. In addition to the statistical test values, we report partial omega squared ( ω 2 ) as an effect size measure. Next to the classical frequentist statistics, we report the results of a Bayesian statistical approach, namely BF 01 , the likelihood with which the data is to occur under the null hypothesis that there is no significant time × group interaction. In Table 2 , we report the presence of significant group differences at baseline in the right most column.

Since we conducted 208 separate frequentist tests we expected 10.4 significant effects simply by chance when setting the alpha value to 0.05. In fact we found only eight significant time × group interactions (these are marked with an asterisk in Tables 2 and 3 ).

When applying a conservative Bonferroni correction, none of those tests survive the corrected threshold of p < 0.00024. Neither does any test survive the more lenient FDR correction. The arithmetic mean of the frequentist test statistics likewise shows that on average no significant effect was found (bottom rows in Tables 2 and 3 ).

In line with the findings from a frequentist approach, the harmonic mean of the Bayesian factor BF 01 is consistently above one but not very far from one. This likewise suggests that there is very likely no interaction between group × time and therewith no detrimental effects of the violent video game GTA in the domains tested. The evidence in favour of the null hypothesis based on the Bayes factor is not massive, but clearly above 1. Some of the harmonic means are above 1.6 and constitute substantial evidence [ 48 ]. However, the harmonic mean has been criticised as unstable. Owing to the fact that the sum is dominated by occasional small terms in the likelihood, one may underestimate the actual evidence in favour of the null hypothesis [ 49 ].

To test the sensitivity of the present study to detect relevant effects we computed the effect size that we would have been able to detect. The information we used consisted of alpha error probability = 0.05, power = 0.95, our sample size, number of groups and of measurement occasions and correlation between the repeated measures at posttest 1 and posttest 2 (average r = 0.68). According to G*Power [ 50 ], we could detect small effect sizes of f = 0.16 (equals η 2 = 0.025 and r = 0.16) in each separate test. When accounting for the conservative Bonferroni-corrected p -value of 0.00024, still a medium effect size of f = 0.23 (equals η 2 = 0.05 and r = 0.22) would have been detectable. A meta-analysis by Anderson [ 2 ] reported an average effects size of r = 0.18 for experimental studies testing for aggressive behaviour and another by Greitmeyer [ 5 ] reported average effect sizes of r = 0.19, 0.25 and 0.17 for effects of violent games on aggressive behaviour, cognition and affect, all of which should have been detectable at least before multiple test correction.

Within the scope of the present study we tested the potential effects of playing the violent video game GTA V for 2 months against an active control group that played the non-violent, rather pro-social life simulation game The Sims 3 and a passive control group. Participants were tested before and after the long-term intervention and at a follow-up appointment 2 months later. Although we used a comprehensive test battery consisting of questionnaires and computerised behavioural tests assessing aggression, impulsivity-related constructs, mood, anxiety, empathy, interpersonal competencies and executive control functions, we did not find relevant negative effects in response to violent video game playing. In fact, only three tests of the 208 statistical tests performed showed a significant interaction pattern that would be in line with this hypothesis. Since at least ten significant effects would be expected purely by chance, we conclude that there were no detrimental effects of violent video gameplay.

This finding stands in contrast to some experimental studies, in which short-term effects of violent video game exposure have been investigated and where increases in aggressive thoughts and affect as well as decreases in helping behaviour have been observed [ 1 ]. However, these effects of violent video gaming on aggressiveness—if present at all (see above)—seem to be rather short-lived, potentially lasting <15 min [ 8 , 51 ]. In addition, these short-term effects of video gaming are far from consistent as multiple studies fail to demonstrate or replicate them [ 16 , 17 ]. This may in part be due to problems, that are very prominent in this field of research, namely that the outcome measures of aggression and pro-social behaviour, are poorly standardised, do not easily generalise to real-life behaviour and may have lead to selective reporting of the results [ 3 ]. We tried to address these concerns by including a large set of outcome measures that were mostly inspired by previous studies demonstrating effects of short-term violent video gameplay on aggressive behaviour and thoughts, that we report exhaustively.

Since effects observed only for a few minutes after short sessions of video gaming are not representative of what society at large is actually interested in, namely how habitual violent video gameplay affects behaviour on a more long-term basis, studies employing longer training intervals are highly relevant. Two previous studies have employed longer training intervals. In an online study, participants with a broad age range (14–68 years) have been trained in a violent video game for 4 weeks [ 52 ]. In comparison to a passive control group no changes were observed, neither in aggression-related beliefs, nor in aggressive social interactions assessed by means of two questions. In a more recent study, participants played a previous version of GTA for 12 h spread across 3 weeks [ 53 ]. Participants were compared to a passive control group using the Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire, a questionnaire assessing impulsive or reactive aggression, attitude towards violence, and empathy. The authors only report a limited increase in pro-violent attitude. Unfortunately, this study only assessed posttest measures, which precludes the assessment of actual changes caused by the game intervention.

The present study goes beyond these studies by showing that 2 months of violent video gameplay does neither lead to any significant negative effects in a broad assessment battery administered directly after the intervention nor at a follow-up assessment 2 months after the intervention. The fact that we assessed multiple domains, not finding an effect in any of them, makes the present study the most comprehensive in the field. Our battery included self-report instruments on aggression (Buss–Perry aggression questionnaire, State Hostility scale, Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance scale, Moral Disengagement scale, World View Measure and Rosenzweig Picture Frustration test) as well as computer-based tests measuring aggressive behaviour such as the delay frustration task and measuring the availability of aggressive words using the word completion test and a lexical decision task. Moreover, we assessed impulse-related concepts such as sensation seeking, boredom proneness and associated behavioural measures such as the computerised Balloon analogue risk task, and delay discounting. Four scales assessing empathy and interpersonal competence scales, including the reading the mind in the eyes test revealed no effects of violent video gameplay. Neither did we find any effects on depressivity (Becks depression inventory) nor anxiety measured as a state as well as a trait. This is an important point, since several studies reported higher rates of depressivity and anxiety in populations of habitual video gamers [ 54 , 55 ]. Last but not least, our results revealed also no substantial changes in executive control tasks performance, neither in the Stop signal task, the Multi-source interference task or a Task switching task. Previous studies have shown higher performance of habitual action video gamers in executive tasks such as task switching [ 56 , 57 , 58 ] and another study suggests that training with action video games improves task performance that relates to executive functions [ 59 ], however, these associations were not confirmed by a meta-analysis in the field [ 60 ]. The absence of changes in the stop signal task fits well with previous studies that likewise revealed no difference between in habitual action video gamers and controls in terms of action inhibition [ 61 , 62 ]. Although GTA does not qualify as a classical first-person shooter as most of the previously tested action video games, it is classified as an action-adventure game and shares multiple features with those action video games previously related to increases in executive function, including the need for hand–eye coordination and fast reaction times.

Taken together, the findings of the present study show that an extensive game intervention over the course of 2 months did not reveal any specific changes in aggression, empathy, interpersonal competencies, impulsivity-related constructs, depressivity, anxiety or executive control functions; neither in comparison to an active control group that played a non-violent video game nor to a passive control group. We observed no effects when comparing a baseline and a post-training assessment, nor when focussing on more long-term effects between baseline and a follow-up interval 2 months after the participants stopped training. To our knowledge, the present study employed the most comprehensive test battery spanning a multitude of domains in which changes due to violent video games may have been expected. Therefore the present results provide strong evidence against the frequently debated negative effects of playing violent video games. This debate has mostly been informed by studies showing short-term effects of violent video games when tests were administered immediately after a short playtime of a few minutes; effects that may in large be caused by short-lived priming effects that vanish after minutes. The presented results will therefore help to communicate a more realistic scientific perspective of the real-life effects of violent video gaming. However, future research is needed to demonstrate the absence of effects of violent video gameplay in children.

Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: a meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychol Sci. 2001;12:353–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, et al. Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western countries: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:151–73.

Article Google Scholar

Ferguson CJ. Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:646–66.

Ferguson CJ, Kilburn J. Much ado about nothing: the misestimation and overinterpretation of violent video game effects in eastern and western nations: comment on Anderson et al. (2010). Psychol Bull. 2010;136:174–8.

Greitemeyer T, Mugge DO. Video games do affect social outcomes: a meta-analytic review of the effects of violent and prosocial video game play. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014;40:578–89.

Anderson CA, Carnagey NL, Eubanks J. Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:960–71.

DeWall CN, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. The general aggression model: theoretical extensions to violence. Psychol Violence. 2011;1:245–58.

Sestire MA, Bartholow BD. Violent and non-violent video games produce opposing effects on aggressive and prosocial outcomes. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:934–42.

Kneer J, Elson M, Knapp F. Fight fire with rainbows: The effects of displayed violence, difficulty, and performance in digital games on affect, aggression, and physiological arousal. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;54:142–8.

Kneer J, Glock S, Beskes S, Bente G. Are digital games perceived as fun or danger? Supporting and suppressing different game-related concepts. Cyber Beh Soc N. 2012;15:604–9.

Sauer JD, Drummond A, Nova N. Violent video games: the effects of narrative context and reward structure on in-game and postgame aggression. J Exp Psychol Appl. 2015;21:205–14.

Ballard M, Visser K, Jocoy K. Social context and video game play: impact on cardiovascular and affective responses. Mass Commun Soc. 2012;15:875–98.

Read GL, Ballard M, Emery LJ, Bazzini DG. Examining desensitization using facial electromyography: violent video games, gender, and affective responding. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;62:201–11.

Szycik GR, Mohammadi B, Hake M, Kneer J, Samii A, Munte TF, et al. Excessive users of violent video games do not show emotional desensitization: an fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11:736–43.

Szycik GR, Mohammadi B, Munte TF, Te Wildt BT. Lack of evidence that neural empathic responses are blunted in excessive users of violent video games: an fMRI study. Front Psychol. 2017;8:174.

Tear MJ, Nielsen M. Failure to demonstrate that playing violent video games diminishes prosocial behavior. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68382.

Tear MJ, Nielsen M. Video games and prosocial behavior: a study of the effects of non-violent, violent and ultra-violent gameplay. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:8–13.

Kühn S, Gleich T, Lorenz RC, Lindenberger U, Gallinat J. Playing super Mario induces structural brain plasticity: gray matter changes resulting from training with a commercial video game. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:265–71.

Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452.

Anderson CA, Deuser WE, DeNeve KM. Hot temperatures, hostile affect, hostile cognition, and arousal: Tests of a general model of affective aggression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21:434–48.

Payne DL, Lonsway KA, Fitzgerald LF. Rape myth acceptance: exploration of its structure and its measurement using the illinois rape myth acceptance scale. J Res Pers. 1999;33:27–68.

McMahon S, Farmer GL. An updated measure for assessing subtle rape myths. Social Work Res. 2011; 35:71–81.

Detert JR, Trevino LK, Sweitzer VL. Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: a study of antecedents and outcomes. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93:374–91.

Bandura A, Barbaranelli C, Caprara G, Pastorelli C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71:364–74.

Rosenzweig S. The picture-association method and its application in a study of reactions to frustration. J Pers. 1945;14:23.

Hörmann H, Moog W, Der Rosenzweig P-F. Test für Erwachsene deutsche Bearbeitung. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1957.

Anderson CA, Dill KE. Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:772–90.

Przybylski AK, Deci EL, Rigby CS, Ryan RM. Competence-impeding electronic games and players’ aggressive feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:441.

Bitsakou P, Antrop I, Wiersema JR, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Probing the limits of delay intolerance: preliminary young adult data from the Delay Frustration Task (DeFT). J Neurosci Methods. 2006;151:38–44.

Hoyle RH, Stephenson MT, Palmgreen P, Lorch EP, Donohew RL. Reliability and validity of a brief measure of sensation seeking. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;32:401–14.

Farmer R, Sundberg ND. Boredom proneness: the development and correlates of a new scale. J Pers Assess. 1986;50:4–17.

Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, Richards JB, Ramsey SE, Stuart GL, et al. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). J Exp Psychol Appl. 2002;8:75–84.

Richards JB, Zhang L, Mitchell SH, de Wit H. Delay or probability discounting in a model of impulsive behavior: effect of alcohol. J Exp Anal Behav. 1999;71:121–43.

Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Cat Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10:85.

Google Scholar

Mehrabian A. Manual for the Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES). (Available from Albert Mehrabian, 1130 Alta Mesa Road, Monterey, CA, USA 93940); 1996.

Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill J, Raste Y, Plumb I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:241–51.

Buhrmester D, Furman W, Reis H, Wittenberg MT. Five domains of interpersonal competence in peer relations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55:991–1008.

Richardson DR, Green LR, Lago T. The relationship between perspective-taking and non-aggressive responding in the face of an attack. J Pers. 1998;66:235–56.

Maras D, Flament MF, Murray M, Buchholz A, Henderson KA, Obeid N, et al. Screen time is associated with depression and anxiety in Canadian youth. Prev Med. 2015;73:133–8.

Hautzinger M, Bailer M, Worall H, Keller F. Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI). Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI): Testhandbuch der deutschen Ausgabe. Bern: Huber; 1995.

Spielberger CD, Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, Owen AE, et al. Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999.

Lorenz RC, Gleich T, Buchert R, Schlagenhauf F, Kuhn S, Gallinat J. Interactions between glutamate, dopamine, and the neuronal signature of response inhibition in the human striatum. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4031–40.

Bush G, Shin LM. The multi-source interference task: an fMRI task that reliably activates the cingulo-frontal-parietal cognitive/attention network. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:308–13.

King JA, Colla M, Brass M, Heuser I, von Cramon D. Inefficient cognitive control in adult ADHD: evidence from trial-by-trial Stroop test and cued task switching performance. Behav Brain Funct. 2007;3:42.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300.

Wagenmakers E-J. A practical solution to the pervasive problems of p values. Psychon Bull Rev. 2007;14:779–804.

Hay DF. The gradual emergence of sex differences in aggression: alternative hypotheses. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1527–37.

Jeffreys H. The Theory of Probability. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1961.

Raftery AE, Newton MA, Satagopan YM, Krivitsky PN. Estimating the integrated likelihood via posterior simulation using the harmonic mean identity. In: Bernardo JM, Bayarri MJ, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Heckerman D, Smith AFM, et al., editors. Bayesian statistics. Oxford: University Press; 2007.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91.

Barlett C, Branch O, Rodeheffer C, Harris R. How long do the short-term violent video game effects last? Aggress Behav. 2009;35:225–36.

Williams D, Skoric M. Internet fantasy violence: a test of aggression in an online game. Commun Monogr. 2005;72:217–33.

Teng SK, Chong GY, Siew AS, Skoric MM. Grand theft auto IV comes to Singapore: effects of repeated exposure to violent video games on aggression. Cyber Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:597–602.

van Rooij AJ, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Shorter GW, Schoenmakers TM, Van, de Mheen D. The (co-)occurrence of problematic video gaming, substance use, and psychosocial problems in adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2014;3:157–65.

Brunborg GS, Mentzoni RA, Froyland LR. Is video gaming, or video game addiction, associated with depression, academic achievement, heavy episodic drinking, or conduct problems? J Behav Addict. 2014;3:27–32.

Green CS, Sugarman MA, Medford K, Klobusicky E, Bavelier D. The effect of action video game experience on task switching. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28:984–94.

Strobach T, Frensch PA, Schubert T. Video game practice optimizes executive control skills in dual-task and task switching situations. Acta Psychol. 2012;140:13–24.

Colzato LS, van Leeuwen PJ, van den Wildenberg WP, Hommel B. DOOM’d to switch: superior cognitive flexibility in players of first person shooter games. Front Psychol. 2010;1:8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hutchinson CV, Barrett DJK, Nitka A, Raynes K. Action video game training reduces the Simon effect. Psychon B Rev. 2016;23:587–92.

Powers KL, Brooks PJ, Aldrich NJ, Palladino MA, Alfieri L. Effects of video-game play on information processing: a meta-analytic investigation. Psychon Bull Rev. 2013;20:1055–79.

Colzato LS, van den Wildenberg WP, Zmigrod S, Hommel B. Action video gaming and cognitive control: playing first person shooter games is associated with improvement in working memory but not action inhibition. Psychol Res. 2013;77:234–9.

Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, Stock AK, Beste C, Colzato LS. Action video gaming and cognitive control: playing first person shooter games is associated with improved action cascading but not inhibition. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144364.

Download references

Acknowledgements

SK has been funded by a Heisenberg grant from the German Science Foundation (DFG KU 3322/1-1, SFB 936/C7), the European Union (ERC-2016-StG-Self-Control-677804) and a Fellowship from the Jacobs Foundation (JRF 2016–2018).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Center for Lifespan Psychology, Lentzeallee 94, 14195, Berlin, Germany

Simone Kühn, Katharina Schmalen, Markus Weichenberger & Charlotte Witt

Clinic and Policlinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Clinic Hamburg-Eppendorf, Martinistraße 52, 20246, Hamburg, Germany

Simone Kühn, Dimitrij Tycho Kugler & Jürgen Gallinat

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Simone Kühn .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary material, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kühn, S., Kugler, D., Schmalen, K. et al. Does playing violent video games cause aggression? A longitudinal intervention study. Mol Psychiatry 24 , 1220–1234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0031-7

Download citation

Received : 19 August 2017

Revised : 03 January 2018

Accepted : 15 January 2018

Published : 13 March 2018

Issue Date : August 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0031-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Far from the future: internet addiction association with delay discounting among adolescence.

- Huaiyuan Qi

International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (2024)

The effect of competitive context in nonviolent video games on aggression: The mediating role of frustration and the moderating role of gender

- Jinqian Liao

- Yanling Liu

Current Psychology (2024)

Geeks versus climate change: understanding American video gamers’ engagement with global warming

- Jennifer P. Carman

- Marina Psaros

- Anthony Leiserowitz

Climatic Change (2024)

Exposure to hate speech deteriorates neurocognitive mechanisms of the ability to understand others’ pain

- Agnieszka Pluta

- Joanna Mazurek

- Michał Bilewicz

Scientific Reports (2023)

The effects of violent video games on reactive-proactive aggression and cyberbullying

- Yunus Emre Dönmez

Current Psychology (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Blame Game: Violent Video Games Do Not Cause Violence

What research shows us about the link between violent video games and behavior..

Updated June 9, 2024 | Reviewed by Matt Huston

- How Can I Manage My Anger?

- Take our Anger Management Test

- Find a therapist to heal from anger

In February 2018, President Trump stated in response to the school shooting in Parkland, Florida that “the level of violence (in) video games is really shaping young people’s thoughts.” He’s far from the first to suggest that violent video games make children violent.

It certainly looks like they do. Jimmy Kimmel humorously pointed this out when he challenged parents to turn off their children’s TVs while they were playing the popular shooter game Fortnite and film the results. Unsurprisingly, many of the children lashed out, some cursing, others striking their parents.

The research

Decades of research seem to support this, too. Three common ways that researchers test levels of aggression in a laboratory are with a “hot sauce paradigm,” the “Competitive Reaction Time Test,” and with word or story completion tasks.

In the hot sauce paradigm , researchers instruct participants to prepare a cup of hot sauce for a taste tester. They inform them that the taste tester must consume all of the hot sauce in the cup and that the taste tester detests spicy food. The more hot sauce the participants put into the cup, the more “aggressive” the participants are said to be.

In the Competitive Reaction Time Test , participants compete with a person in the next room. They are told that both people must press a button as fast as possible when they see a light flash. Whoever presses the button first will get to “punish” the opponent with a blast of white noise. They are allowed to turn up the volume as loud and as long as they want. In reality, there is no participant in the next room; the test is designed to let people win exactly half of the games. The researchers are measuring how far they turned the dial and how long they held it for. In theory, people who punish their opponent more severely are more aggressive.

During a word or story completion task , participants are shown a word with missing letters or a story without an ending. Participants are asked to guess what word can be made from those letters or to predict what will happen next in a story. When participants choose “aggressive” words (such as assuming that “M _ _ _ E R” is “murder” instead of “mother”) or assuming that characters will hurt one another, they are considered more aggressive.

These tests have been used to examine whether violent games increase aggression. Several representative studies are summarized below. In each study, the participants assigned to play a violent game seemed more prone to acting or thinking aggressively than those who played a non-violent game for an equivalent amount of time.

- 2000: Undergraduate psychology students played a video game for 30 minutes and were given the Competitive Reaction Time Test. Those who played Wolfenstein 3D (a violent game) turned the “ punishment ” dial for a longer period of time than those who played Myst (a non-violent game).

- 2002: Participants played a video game for 20 minutes and were given a story completion task. Players who played Carmageddon , Duke Nukem , Mortal Kombat , or Future Cop (violent games) were more likely to predict that the characters in an ambiguous story would react to conflict aggressively than those who had played Glider Pro , 3D Pinball , Austin Powers , or Tetra Madness (non-violent games).

- 2004: Participants played a video game for 20 minutes and were given a word-completion task. Players who played Dark Forces , Marathon 2 , Speed Demon , Street Fighter , and Wolfenstein 3D (violent games) were more likely to predict that word fragments were part of aggressive words than non-aggressive words than those who had played 3D Ultra Pinball , Glider Pro , Indy Car II , Jewel Box , and Myst (non-violent games).

- 2004: Participants played a video game for 20 minutes and were given the Competitive Reaction Time Test. Those who played Marathon 2 (a violent game) turned the “noise punishment” dial to higher levels than those who had played Glider PRO (a non-violent game).

- 2014: Participants played a video game for 30 minutes and were given the hot sauce test. People who played Call of Duty: Modern Warfare (a violent game) put more hot sauce into the cup than people who played LittleBigPlanet 2 (a non-violent game).

It is easy to conclude from this research that violent games make people more aggressive. In 2015, The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Task Force on Violent Media analyzed 31 similar studies published since 2009 and concluded that “violent video game use has an effect on... aggressive behavior, cognitions, and affect.”

Is this research valid?

However, experienced gamers would notice a critical problem with the studies’ construction.

Although Wolfenstein 3D , Call of Duty , and Duke Nukem are certainly more violent than Myst , LittleBigPlanet 2 , and Glider Pro , violence is far from the only variable.

For example, Wolfenstein 3D is an action-packed, exciting, and fast-paced shooting game, while Myst is a slow, methodical, exploration and puzzle game. To help illustrate this point, here is footage of people playing Wolfenstein and Myst .

Comparing the two and assuming that any differences in the level of aggression after playing must be due to the different levels of violence ignores all of these other variables.

If it’s not violence, what is it?

Some researchers have taken note of this criticism in recent years and begun exploring alternative hypotheses for the differences found, such as that the violent games chosen were also harder to master and that many people had aggressive thoughts simply because they lost . When they have conducted more nuanced studies to explore these other hypotheses, they have found that the violence was not the critical variable.

For example, one clever set of studies examined whether players acted out simply because some games “impeded competence.”

- The first study demonstrated that two of the games in the previous studies differed significantly in how difficult the games were to master; Glider Pro 4 uses just two buttons, while Marathon 2 requires the mouse plus 20 different buttons. This additional variable they identified makes it inappropriate to compare the two and draw a scientifically credible conclusion.

- The researchers then created two first-person-shooter games with differing levels of violence. In the violent game, characters who the players shot suffered horrific, bloody deaths. The other was a paintball game in which characters simply disappeared when shot. The two games were otherwise identical. When they tested the level of aggression afterward, they found no differences between the groups .

- In two other studies, these researchers manipulated the game Tetris to be more complicated for half of the participants, either by making the controls complicated or by giving them pieces that could not fit into the grid easily. The groups playing complicated, frustrating versions of the game showed more aggression afterward.

In each of these studies, it was the level of difficulty— not the presence of violence—that predicted aggressive thoughts and actions afterward. When the games were better matched than the previous studies, violence did not appear to affect aggression after playing.

In other words, these researchers concluded that games can make people angry just by being difficult to win.

A clear example of how frustration alone can lead to aggression in a non-violent game can be seen on YouTube, on well-known streamer Markiplier’s first attempt to beat Getting Over It . The game is bizarre; players try to guide a shirtless man in a cauldron up a mountain using only a hammer. It is designed to be extraordinarily unforgiving; one minor misstep might undo an hour of progress. Here ’s a video of him throwing a chair when he slipped down the mountain.

Others have suggested that it is the level of competition present in many games which fosters aggressive thoughts and actions. This is easy to understand—how many of us have yelled at friends or overturned the board at the end of a tense game of Monopoly? One gaming writer quipped , “What makes you angrier: dying to a horde of violent aliens in Gears of War , or losing a close match to your taunting brother in the very non-violent Mario Kart ?”

Anecdotally, I have found these two hypotheses to be true for my clients. I frequently hear from them or their parents that they act aggressively while playing video games, e.g. breaking controllers or yelling at their parents or other players. When I ask my clients about the situation, they talk about feeling frustrated, usually because of difficult gameplay, opponents playing unfairly, losing, or having to stop playing at an inopportune time in the game. These outbursts happen for violent and non-violent games alike.

What if violence is the variable?

In order to understand the results of the experiments, it is important to understand the difference between “statistical significance” and “clinical significance.” Statistical significance is a way to assess whether the results of the study were due to a real difference between groups or whether the results might have been due to chance. Clinical significance is whether the results are important for individuals or the population as a whole.

For example, the 2000 study which found that, on average, players turned the “punishment” dial longer when they played Wolfenstein 3D than those who had played Myst did reach statistical significance.

However, the actual difference was between 6.81 and 6.65 seconds, a difference of 0.16 seconds. To put that number into context, blinking takes roughly 0.1 to 0.4 seconds . That is, subjects who played violent and non-violent games both chose to punish an imaginary opponent for roughly seven seconds. The difference between how long the groups held the dial was less than the blink of an eye .

A 2 percent difference in how long someone holds a dial in a laboratory is hardly cause for alarm. Further, studies have shown that this tiny increase in aggression fades quickly, lasting less than 10 minutes .

Despite this, the researchers linked violent video games to the school shooting at Columbine High School in the first paragraph of the paper.

The APA’s Society for Media Psychology and Technology has since firmly stated that this kind of comparison is inappropriate : “Journalists and policymakers do their constituencies a disservice where they link acts of real-world violence with the perpetrators’ exposure to violent video games...there’s little scientific evidence to support the connection...Discovering that a young crime perpetrator also happened to play violent video games is no more illustrative than discovering that he or she happened to wear sneakers or used to watch Sesame Street.”

In fact, the Secret Service’s report studying characteristics of school shooters showed that only 14 percent of school shooters enjoyed violent video games , compared to 70 percent of their peers.

What about long-term effects?

Some researchers who study aggression use the General Aggression Model (GAM) , a unified theory of aggression created by the researcher who authored many of the papers that found a link between aggression and violent video games. The theory explains that many things may increase aggression in the short-term, including being insulted, unpleasant noises, and the temperature of the room.

The GAM theory further suggests that repeatedly acting on aggressive impulses may push people toward becoming permanently more aggressive. For example, a normally peaceful person may act out when insulted. The more times the person acts out, the more “accessible” violent responses become and the more likely this person is to act violently in future situations.

This makes intuitive sense, and researchers sometimes state that even a tiny increase in aggression, like the aforementioned 2 percent, could be cumulative and lead to long-term aggressive tendencies.

However, it does not appear that this is true. Researchers recently surveyed more than 1,000 British teens ages 14-15 on how often they play games, independently examined how violent those games are, and asked their parents to report how aggressively their children acted over the past month. They examined whether each variable was connected and found no evidence of a correlation. Teens who played violent games many hours per week did not act more aggressively than those who played peaceful games or no games at all.

Should children play violent games?

Of course, I am not suggesting that it is appropriate for young children to play violent games. I would not recommend that young children play Call of Duty for the same reason that I would not recommend they watch Saving Private Ryan until they are mature enough to understand it.

Even though it is not likely to make peaceful people aggressive, media which contains graphic violence can be frightening and hard to understand, especially for young people. Parents should take reasonable steps to ensure that their children are playing age-appropriate games, in the same way that they should ensure their children are watching age-appropriate movies.

Some parents choose to play video games with their children, ask them to play in a common area, or sit with them while they play to help provide context to the content of the games. These are great ideas; they allow parents to teach their children the difference between violence in games and in real life, to have conversations about the actions their characters take, and to comfort children who become scared.

It also helps parents understand what their children are experiencing while playing games so they can help them learn to manage these feelings of frustration. Parents who are familiar with their children’s video games can determine whether they are age-appropriate, their children’s motivations for play, how their children are affected, and how to set appropriate limits.

Adachi, P.J.C. & Willoughby, T. (2011). The effect of video game competition and violence on aggressive behavior: Which characteristic has the greatest influence? Psychology of Violence, 1 (4). Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2cab/940f9292928a48d57c375259442c9dc7d…

Allen, J.J., Anderson, C.A., & Bushman, B.J. (2017). The General Aggression Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19 . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316119742_The_General_Aggressi…

Anderson, C.A., Carnagey, N.L., & Eubanks, J. (2003). Exposure to violent media: The effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84 (5). Retrieved from http://www.craiganderson.org/wp-content/uploads/caa/abstracts/2000-2004…

Anderson, C.A. & Dill, K.E. (2000). Video games and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behavior in the laboratory and in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78 (4). Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.583.6828&rep=r…

APA Task Force on Violent Media (2015). Technical report on the review of the violent video game literature. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/families/review-video-games.pdf

Barlett, C., Branch, O., Rodeheffer, C., & Harris, R. (2009). How long do the short-term violent video game effects last? Aggressive Behavior, 35 . Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23996782_How_Long_Do_the_Short…

Breuer, J., Scharkow, M., & Quandt, T. (2013, December 23). Sore Losers? A Reexamination of the Frustration–Aggression Hypothesis for Colocated Video Game Play. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000020 Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261794000_Sore_losers_A_reexam…

Bushman, B.J. & Anderson, C.A. (2002). Violent video games and hostile expectations: A test of the General Aggression Model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237308783_Violent_Video_Games_…

Chester, D.S. & Lasko, E. (2018). Validating a standardized approach to the Taylor Aggression Paradigm. Social Psychological and Personality Science. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325749887_Validating_a_Standar…

CNN. (2018, February 22). Trump blames video games, movies for violence [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3RKZn2Sf7bo

Doommaster1994 [Doommaster1994]. (2008, November 13). Wolfenstein 3D Gameplay [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=561sPCk6ByE

Ferguson, C.J. (2008). The school shooting/violent video game link: Causal relationship or moral panic? Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 5. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/725227/The_school_shooting_violent_video_game_…

Ferguson, C. (2017, Spring/Summer). News Media, Public Education and Public Policy Committee: Societal violence and video games: Public statements of a link are problematic. The Amplifier Magazine . Retrieved from https://div46amplifier.com/2017/06/12/news-media-public-education-and-p…

Filardodesigns [filardodesigns]. (2008, September 8). MYST - Chapter 1 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-8CFun3nEw

Fischbach, M.E. [Markiplier]. (2017, December 7). I LITERALLY THROW A CHAIR IN RAGE | Getting Over It - Part 1 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/dH9w9VlyNO4

Hollingdale, J. & Greitemeyer, T. (2014). The effect of online violent video games on levels of aggression. PLoS ONE 9 (11). Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.01117…

Jimmy Kimmel Live [Jimmy Kimmel Live]. (2018, December 13). YouTube Challenge - I Turned Off the TV During Fortnite [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AggZU8sg5HI

Lieberman, J.D., Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & McGregor, H.A. (1999). A hot new way to measure aggression: Hot sauce allocation. Aggressive Behavior, 25 . Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3a78/9895c3e18f9e3356e98feda68521b726f…

Milo, R., Jorgensen, P., Moran, U., Weber, G., & Springer, M. (2009). BioNumbers - the database of key numbers in molecular and cell biology. Nucleic Acids Research, 38 . Retrieved from https://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu/bionumber.aspx?&id=100706&ver=4

Przybylski, A.K., Deci, E.L., Rigby, C.S., & Ryan, R.M. (2014). Competence-impeding electronic games and players’ aggressive feelings, thoughts, and behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106 (3). Retrieved from http://selfdeterminationtheory.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2014_Przy…

Przybylski, A.K. & Weinstein, N. (2019). Violent video game engagement is not associated with adolescents’ aggressive behaviour: Evidence from a registered report. Royal Society Open Science, 6 (2). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331409534_Violent_video_game_e…

Schreier, J. (2015, August 14). Why most video game “aggression” studies are nonsense. Retrieved from https://kotaku.com/why-most-video-game-aggression-studies-are-nonsense-…

Andrew Fishman is a licensed social worker in Chicago, Illinois. He is also a lifelong gamer who works with clients to understand the impact video games have had on their mental health.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Christopher J. Ferguson, The Conversation Christopher J. Ferguson, The Conversation

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/analysis-why-its-time-to-stop-blaming-video-games-for-real-world-violence

Analysis: Why it’s time to stop blaming video games for real-world violence

In the wake of the El Paso shooting on Aug. 3 that left 21 dead and dozens injured, a familiar trope has reemerged: Often, when a young man is the shooter, people try to blame the tragedy on violent video games and other forms of media.

This time around, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick placed some of the blame on a video game industry that “ teaches young people to kill .” Republican House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy of California went on to condemn video games that “dehumanize individuals” as a “problem for future generations.” And President Trump pointed to society’s “glorification of violence,” including “ gruesome and grisly video games .”

These are the same connections a Florida lawmaker made after the Parkland shooting in February 2018, suggesting that the gunman in that case “was prepared to pick off students like it’s a video game .”

Kevin McCarthy, the GOP House minority leader, also tells Fox News that video games are the problem following the mass shootings in El Paso and Dayton. pic.twitter.com/w7DmlJ9O1K — John Whitehouse (@existentialfish) August 4, 2019

But, speaking as a researcher who has studied violent video games for almost 15 years, I can state that there is no evidence to support these claims that violent media and real-world violence are connected. As far back as 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that research did not find a clear connection between violent video games and aggressive behavior.

Criminologists who study mass shootings specifically refer to those sorts of connections as a “ myth .” And in 2017, the Media Psychology and Technology division of the American Psychological Association released a statement I helped craft, suggesting reporters and policymakers cease linking mass shootings to violent media, given the lack of evidence for a link.

A history of a moral panic

So why are so many policymakers inclined to blame violent video games for violence? There are two main reasons.

The first is the psychological research community’s efforts to market itself as strictly scientific. This led to a replication crisis instead, with researchers often unable to repeat the results of their studies. Now, psychology researchers are reassessing their analyses of a wide range of issues – not just violent video games, but implicit racism , power poses and more.

The other part of the answer lies in the troubled history of violent video game research specifically.

An attendee dressed as a Fortnite character poses for a picture in a costume at Comic Con International in San Diego, California, U.S., July 19, 2019. Photo by REUTERS/Mike Blake

Beginning in the early 2000s, some scholars, anti-media advocates and professional groups like the APA began working to connect a methodologically messy and often contradictory set of results to public health concerns about violence. This echoed historical patterns of moral panic, such as 1950s concerns about comic books and Tipper Gore’s efforts to blame pop and rock music in the 1980s for violence, sex and satanism.

Particularly in the early 2000s, dubious evidence regarding violent video games was uncritically promoted . But over the years, confidence among scholars that violent video games influence aggression or violence has crumbled .

Reviewing all the scholarly literature

My own research has examined the degree to which violent video games can – or can’t – predict youth aggression and violence. In a 2015 meta-analysis , I examined 101 studies on the subject and found that violent video games had little impact on kids’ aggression, mood, helping behavior or grades.

Two years later, I found evidence that scholarly journals’ editorial biases had distorted the scientific record on violent video games. Experimental studies that found effects were more likely to be published than studies that had found none. This was consistent with others’ findings . As the Supreme Court noted, any impacts due to video games are nearly impossible to distinguish from the effects of other media, like cartoons and movies.

Any claims that there is consistent evidence that violent video games encourage aggression are simply false.

Spikes in violent video games’ popularity are well-known to correlate with substantial declines in youth violence – not increases. These correlations are very strong, stronger than most seen in behavioral research. More recent research suggests that the releases of highly popular violent video games are associated with immediate declines in violent crime, hinting that the releases may cause the drop-off.

The role of professional groups

With so little evidence, why are people like Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin still trying to blame violent video games for mass shootings by young men? Can groups like the National Rifle Association seriously blame imaginary guns for gun violence?

A key element of that problem is the willingness of professional guild organizations such as the APA to promote false beliefs about violent video games. (I’m a fellow of the APA.) These groups mainly exist to promote a profession among news media, the public and policymakers, influencing licensing and insurance laws . They also make it easier to get grants and newspaper headlines. Psychologists and psychology researchers like myself pay them yearly dues to increase the public profile of psychology. But there is a risk the general public may mistake promotional positions for objective science.

In 2005 the APA released its first policy statement linking violent video games to aggression. However, my recent analysis of internal APA documents with criminologist Allen Copenhaver found that the APA ignored inconsistencies and methodological problems in the research data.

The APA updated its statement in 2015, but that sparked controversy immediately: More than 230 scholars wrote to the group asking it to stop releasing policy statements altogether. I and others objected to perceived conflicts of interest and lack of transparency tainting the process.

It’s bad enough that these statements misrepresent the actual scholarly research and misinform the public. But it’s worse when those falsehoods give advocacy groups like the NRA cover to shift blame for violence onto non-issues like video games. The resulting misunderstanding hinders efforts to address mental illness and other issues, such as the need for gun control, that are actually related to gun violence.

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original article . This story was updated from an earlier version to reflect the events surrounding the El Paso and Dayton shootings.

Christopher J. Ferguson is a professor of psychology at Stetson University. He's coauthor of " Moral Combat: Why the War on Violent Video Games is Wrong ."

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

El Paso shooting is domestic terrorism, investigators say

Nation Aug 04

Health Research 4 U

Safe To Play

Violent Video Games and Aggression

After mass shootings, the media and public officials often question the role of the shooter’s video game habits.

The American Psychological Association (APA) considers violent video games a risk factor for aggression . [1] In 2017, the APA Task Force on Violent Media concluded that violent video game exposure was linked to increased aggressive behaviors, thoughts, and emotions, as well as decreased empathy. However, it is not clear whether violent video game exposure was linked to criminality or delinquency.

Do Violent Video Games Increase Aggression?

Studies have shown that playing violent video games can increase aggressive thoughts, behaviors, and feelings in both the short-term and long-term. [2] Violent video games can also desensitize people to seeing aggressive behavior and decrease prosocial behaviors such as helping another person and feeling empathy (the ability to understand others). The longer that individuals are exposed to violent video games, the more likely they are to have aggressive behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. These effects have been seen in studies in both Eastern and Western countries. Although males spend more time than females playing violent video games, violent video game exposure can increase aggressive thoughts, behaviors, and feelings in both sexes.

Aggressive behavior is measured by scientists in a number of ways. Some studies looked at self-reports of hitting or pushing, and some looked at peer or teacher ratings on aggressive behaviors. Other studies looked at how likely an individual was to subject others to an unpleasant exposure to hot sauce or a loud noise after playing violent video games.

Unfortunately, few studies have been completed on violent video game exposure and aggression in children under age 10. There is also little information about the impact of violent video game exposure on minority children.

There have not been many studies on the effects of different characteristics of video games, such as perspective or plot. However, some studies have found that competition among players in video games is a better predictor of aggressive behavior than is the level of violence. [3]

Do Violent Video Games Increase Violence?

Violence is a form of aggression, but not all aggressive behaviors are violent. Very few studies have looked at whether playing violent video games increases the chances of later delinquency, criminal behavior, or lethal violence. Such studies are difficult to conduct, and require very large numbers of children. It makes sense that since playing violent video games tends to increase the level of aggressive behavior it would also results in more lethal violence or other criminal behaviors, but there is no clear evidence to support that assumption.

In the aftermath of the Parkland shooting in Florida in 2018, policymakers are again questioning the influence of violent video games. The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) affirms that their rating system is effective, but the APA Task Force on Violent Media recommends that the ESRB revise their rating system to make the level of violence clearer. The Task Force also recommends that further research must be done using delinquency, violence, and criminal behavior as outcomes to determine whether or not violent video games are linked to violence.

Bottom Line

It is important to keep in mind that violent video game exposure is only one risk factor of aggressive behavior. For example, mental illness, adverse environments, and access to guns are all risk factors of aggression and violence.

All articles are reviewed and approved by Dr. Diana Zuckerman and other senior staff.

The National Center for Health Research is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research, education and advocacy organization that analyzes and explains the latest medical research and speaks out on policies and programs. We do not accept funding from pharmaceutical companies or medical device manufacturers. Find out how you can support us here .

References :

- The American Psychological Association Task Force on Violent Media. (2017). The American Psychological Association Task Force Assessment of Violent Video Games: Science in the Service of Public Interest. American Psychologist . 72(2): 126-143. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0040413 . Accessed on March 9, 2018.

- Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, Rothstein HR, Muniba. Violent Video Game Effects on Aggression, Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior in Eastern and Western Countries: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin . 2010.

- Adachi, PJ and Willoughby, T. (2013). Demolishing the Competition: The Longitudinal Link Between Competitive Video Games, Competitive Gambling, and Aggression. Journal of Youth Adolescence. 42(7): 1090-104. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9952-2.

- Sanstock, JW. A Topical Approach to Life Span Development 4th Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007. Ch 15. 489-491

- Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. The Effects of Pathological Gaming on Aggressive Behavior. Journal of Youth Adolescence . 2010.

- Huesmann LR, Moise J, Podolski CP, Eron LD. (2003). Longitudinal relations between childhood exposure to media violence and adult aggression and violence. Developmental Psychology . 35:201-221.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

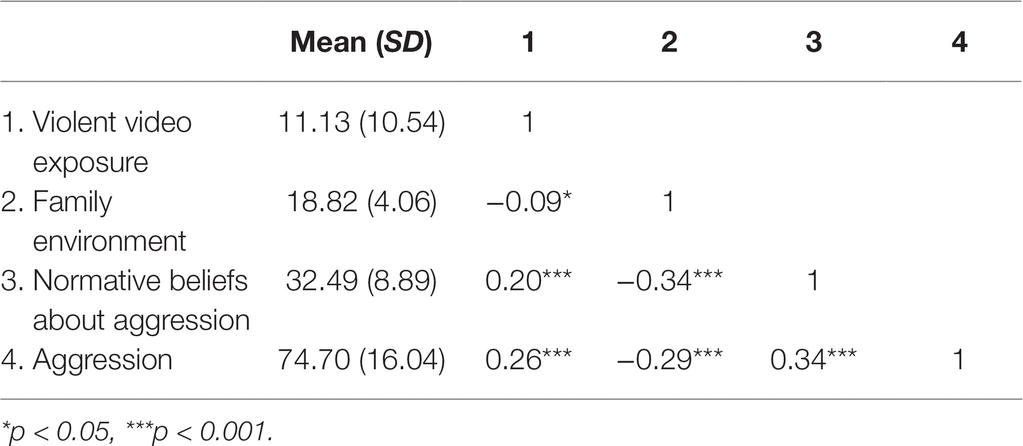

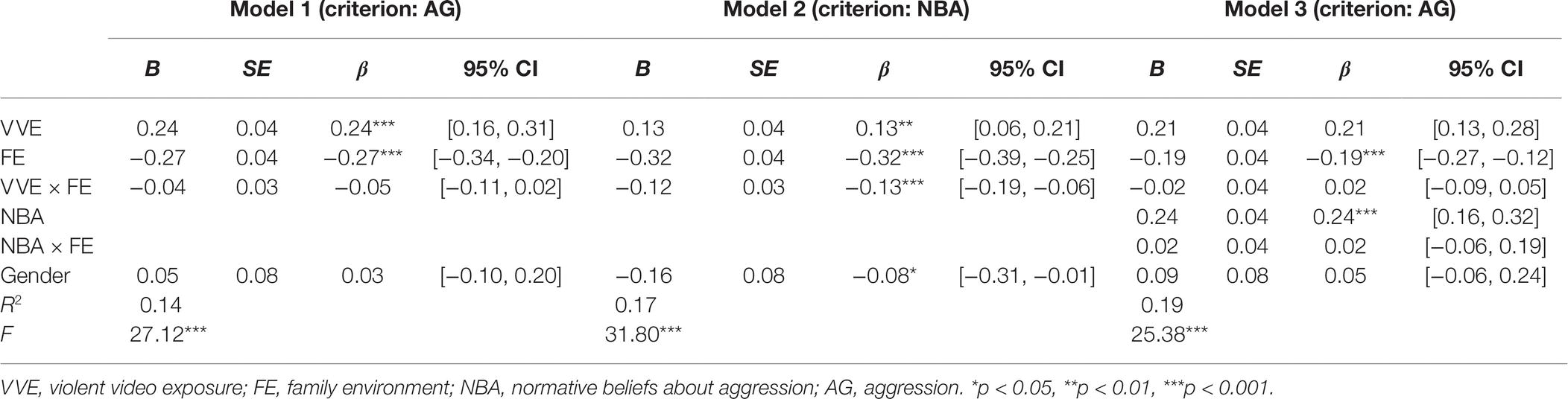

Violent Video Game Exposure and Problem Behaviors among Children and Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Deviant Peer Affiliation for Gender and Grade Differences

Associated data.

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.