ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

How does work motivation impact employees’ investment at work and their job engagement a moderated-moderation perspective through an international lens.

- 1 Independent Researcher, Netanya, Israel

- 2 Graduate School of Career Studies, Hosei University, Tokyo, Japan

This paper aims at shedding light on the effects that intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, as predictors, have on heavy work investment of time and effort and on job engagement. Using a questionnaire survey, this study conducted a moderated-moderation analysis, considering two conditional effects—worker’s status (working students vs. non-student employees) and country (Israel vs. Japan)—as potential moderators, since there are clear cultural differences between these countries. Data were gathered from 242 Israeli and 171 Japanese participants. The analyses revealed that worker’s status moderates the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on heavy work investment of time and effort and on job engagement and that the moderating effects were conditioned by country differences. Theoretical and practical implications and future research suggestions are discussed.

Introduction

Our world today has been described by the acronym VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous). In this rapidly changing world, organizations and individuals need to engage in continuous learning. To achieve a competitive advantage, organizations need to develop organizational learning, which can be achieved by acquiring learning individuals. From the latter’s viewpoint, it is getting more necessary for workers to learn continuously to enhance and maintain their employability. As shown in previous research, the number of people engaging in lifelong learning has significantly increased ( Corrales-Herrero and Rodríguez-Prado, 2018 ).

In such an era, an organization needs to acquire and retain learning individuals. However, it is not an easy task because they might have turnover intentions, even when they are motivated to work. Since learning individuals enhance their skills continuously and have a “third place” for new encounters (e.g., school), they are likely to find other attractive job opportunities. Therefore, it is valuable for us to explore how motivation affects learning individuals’ attitudes and behavior. However, to the best of our knowledge, researchers have not addressed this issue.

Recently, researchers and practitioners have paid increasing attention to employees’ job engagement (JE) ( Bailey et al., 2017 ). Previous studies suggested that engaged workers are likely to achieve high performance and have low intention to leave ( Rich et al., 2010 ; Alarcon and Edwards, 2011 ). However, JE does not necessarily represent workers’ favorable attitude ( van Beek et al., 2011 ). In the case of working individuals, their appearance of being “highly engaged” can be caused by time constraints or impression management motive.

Recognizing the ambiguous nature of “engaged workers,” this study also focuses on a relatively new construct called heavy work investment (HWI). People high in HWI are apparently similar to those high in JE. However, as will be discussed later, these two constructs are distinct. By focusing on both engagement and HWI, we can reveal the underlying mechanism of how motivation affects the learning individuals’ engagement.

To address these issues, we analyzed quantitative data which include both learning individuals (hereafter called “working students”) and non-student workers. The choice of employees who are students as opposed to “regular” employees was based on arguments presented in the conservation of resources (COR) theory ( Hobfoll, 1989 , 2011 ). It will be elaborated further in this paper.

Besides, since the contexts of lifelong learning and work in an organization can affect the focal mechanism, we collected data from two countries—Israel and Japan—and conducted a between-country comparative analysis. As we will discuss below, these two countries widely differ in cultural dimensions, as suggested by Hofstede (1980 , 2018) . We limit the scope of the research to Israel and Japan to concentrate on a specific issue which was not investigated in previous studies, especially in a comparison between these two countries (to the best of our knowledge). The sample and analysis of this study can provide insightful implications because these two countries are widely different in their national cultural contexts.

Work Motivation

A general definition of motivation is the psychological force that generates complex processes of goal-directed thoughts and behaviors. These processes revolve around an individual’s internal psychological forces alongside external environmental/contextual forces and determine the direction, intensity, and persistence of personal behavior aimed at a specific goal(s) ( Kanfer, 2009 ; Kanfer et al., 2017 ). In the work domain, work motivation is “a set of energetic forces that originate within individuals, as well as in their environment, to initiate work-related behaviors and to determine their form, direction, intensity and duration” (after Pinder, 2008 , p. 11). As mentioned, work motivation is derived from an interaction between individual differences and their environment (e.g., cultural, societal, and work organizational) ( Latham and Pinder, 2005 ). In addition, motivation is affected by personality traits, needs, and even work fit, while generating various outcomes and attitudes, such as satisfaction, organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), engagement, and more (for further reading, see Tziner et al., 2012 ).

Moreover, work motivation, as an umbrella term under the self-determination theory (SDT), is usually broken down into two main constructs—intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation ( Ryan and Deci, 2000b ). On the one hand, intrinsic motivation is an internal driver. Employees work out of the excitement, feeling of accomplishment, joy, and personal satisfaction they derive both from the processes of work-related activities and from their results ( Deci and Ryan, 1985 ; Bauer et al., 2016 ; Legault, 2016 ). On the other hand, extrinsic motivation maintains that the individual’s drive to work is influenced by the organization, the work itself, and the employee’s environment. These can range from social norms, peer influence, financial needs, promises of reward, and more. As such, being extrinsically motivated is being focused on the utility of the activity rather than the activity itself (see Deci and Ryan, 1985 ; Legault, 2016 ). However, this does not, by any means, point that extrinsic motivation is less effective than intrinsic motivation ( Deci et al., 1999 ).

Furthermore, the SDT ( Ryan and Deci, 2000b ) argues that each type of motivation is on opposite poles of a single continuum. However, we agree with the notion that they are mutually independent, as Rockmann and Ballinger (2017) wrote:

“…there is increasing evidence that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are independent, each with unique antecedents and outcomes … in organizations, because financial incentives exist alongside interesting tasks, individuals can simultaneously experience extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for doing their work.” (p. 11)

Literature-wise, the intrinsic–extrinsic outlook of motivation lacks coherent research, and to the best of our knowledge, most of the past research addressed the intrinsic part (e.g., Rich et al., 2010 ; Bauer et al., 2016 ). As such, we would align with the approach to distinguish the two work motivations as was reviewed in this section and consequently treat it as a predictor in our research.

Job Engagement

Work engagement is typically defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” ( Schaufeli et al., 2002 , p. 74). As such, engaged employees appear to be hardworking ( vigor ), are more involved in their work ( dedication ), and are more immersed in their work ( absorption ) (see also Bakker et al., 2008 ; Chughtai and Buckley, 2011 ; Taris et al., 2015 ). JE was initially proposed as a positive construct ( Kahn, 1990 ), and empirical studies revealed that a high level of JE leads to positive work outcomes. For example, recent studies exhibited its positive effect on individual job performance and adverse effect on turnover intention ( Breevaart et al., 2016 ; Owens et al., 2016 ; Shahpouri et al., 2016 ; Kumar et al., 2018 ). Therefore, employees’ JE has been regarded as one of the performance indicators of human resource management.

In terms of antecedents and predictors, it is broadly accepted that JE may be affected by both individual differences (e.g., Sharoni et al., 2015 ; Latta and Fait, 2016 ; Basit, 2017 ) and environmental/contextual elements (e.g., Sharoni et al., 2015 ; Basit, 2017 ; Gyu Park et al., 2017 ; Lebron et al., 2018 ) (see also Macey and Schneider, 2008 ) or even an interaction between these two factors (e.g., Sharoni et al., 2015 ; Hernandez and Guarana, 2018 ).

Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivation and JE

To the best of our knowledge, only a few papers examined the association between work motivation and JE. For instance, Rich et al. (2010) tested a model in which both intrinsic motivation and JE were tested “vertically,” meaning they were both mediators (in the model) rather than two factors in a predictor–outcome relationship. This offers a further incentive to examine the association between (intrinsic/extrinsic) work motivation and JE.

Because JE is “…driven by perceptions of psychological meaningfulness, safety, and availability at work” ( Hernandez and Guarana, 2018 , p. 1), a vital notion behind work motivation is the perception of the job as a place for fulfilling different needs: extrinsic needs, such as income and status, and intrinsic needs, such as enjoyment, and personal challenge. This perception, very likely, bolsters the association between the employees’ drive to work and the workplace or the work themselves, increasing the involvement and the amount of work they put into their work (i.e., JE). These assumptions lead us to hypothesize the following:

H1: Intrinsic motivation positively associates with JE.

H2: Extrinsic motivation positively associates with JE.

Heavy Work Investment

Fundamentally different from being immersed or involved at work (e.g., JE), employees usually invest time and energy at their workplace with various manifestations, which ultimately barrel down to the concept of HWI. This umbrella term encompasses two major core aspects: (1) investment of time (i.e., working long hours) and (2) investment of effort and energy (i.e., devoting substantial efforts, both physical and mental, at work) ( Snir and Harpaz, 2012 , Snir and Harpaz, 2015 ). These dimensions are, respectively, called (a) time commitment (HWI-TC) and work intensity (HWI-WI). Notably, many studies deal with the implications of working overtime (e.g., Stimpfel et al., 2012 ; Caruso, 2014 ). However, to the best of our knowledge, empirical studies regarding the investment of efforts at work as an indicator of HWI (e.g., Tziner et al., 2019 ) are scarce. Therefore, the current research addresses both of the core dimensions of HWI (i.e., time [HWI-TC] and effort [HWI-WI]).

In reality, HWI consists of many different constructs (e.g., workaholism and work addiction or passion to work) but conclusively revolves around the devotion of time and effort at work (see Snir and Harpaz, 2015 , p. 6). HWI is apparently similar to JE, but these two constructs are distinct. As shown in previous studies, the correlation between workaholism—one component of HWI—and JE is generally weak, and engaged individuals can be not only high in HWI but also low in HWI ( van Beek et al., 2011 ).

For HWI’s possible predictors, Snir and Harpaz (2012 , 2015) have differentiated between situational and dispositional types of HWI (based on Weiner’s, 1985 , attributional framework). Examples of situational types are financial needs or employer-directed contingencies (external factors), while dispositional types are characterized by individual differences (internal factors), such as work motivation.

Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivation and HWI

As previously mentioned, employees may be driven to work by both intrinsic and extrinsic forces, motivating them to engage in work activities to fulfill different needs (e.g., salary, enjoyment, challenge, and promotion). Ultimately, these two mutually exclusive elements would translate into the same outcome—increased investment at work. At this juncture, however, we cannot say what type of work motivation (intrinsic/extrinsic) would more tightly link to either (1) the heavier devotion of time (HWI-TC) or (2) the heavier investment of effort (HWI-WI) at work. Consequently, we hypothesize further the following:

H3: Intrinsic motivation positively associates with both HWI-TC and HWI-WI.

H4: Extrinsic motivation positively associates with both HWI-TC and HWI-WI.

It is important to emphasize that, again, HWI and JE are mutually independent constructs. Nevertheless, HWI points at two different investment “types”—in time and effort. Theoretically, we see that although both aspects of investment are, probably, linked to JE, we may also conclude that these associations would differ based on the type of investment. For example, while workers may allegedly spend a great deal of time on the job, in actuality, they may not be working (studiously) on their given tasks at all, a situation labeled as “presenteeism” (see Rabenu and Aharoni-Goldenberg, 2017 ). However, exerting more effort at work, by definition, means that one is more engaged, to whatever extent, in work (e.g., investing more effort, basically, means investing time as well, but not vice versa). In other words, while we expect that JE will be positively related to dimensions of HWI (one must devote time and invest more effort to be engaged at work), we also assume that JE will be more strongly correlated with the effort dimension, rather than time . As such, we hypothesize the following:

H5a: JE positively associates with HWI-TC.

H5b: JE positively associates with HWI-WI.

H5c: JE has a stronger association with HWI-WI than with HWI-TC.

The purpose of H5a–H5c is to differentiate JE from HWI-WI and HWI-TC, as they may have some overlaps. However, they are still stand-alone constructs, which is the reason the current research gauge them both and correlate them, though they are both outcome variables (an issue of convergent and discriminant validity).

Worker’s Status—Buffering Effect

An organization or a workplace is usually composed of several types of employees, albeit not all of them exhibit the same attitudes and behaviors at work. For example, temporary workers report greater job insecurity and lower well-being than permanent employees ( Dawson et al., 2017 ). Another example is of students (i.e., working students vs. non-student employees). The motivators and incentives needed to drive corporate/working students differ from others. They are, for instance, more interested in salary, promotion, tangible rewards in their job, and other such benefits ( Palloff and Pratt, 2003 ).

Furthermore, capitalizing upon the COR theory ( Hobfoll, 1989 , 2011 ), the main argument is that employees invest various resources (e.g., time, energy, money, effort, and social credibility) at work. The more resources devoted, the less will remain at the individual’s disposal, and prolonged state of depleted resources without gaining others may result in stress and, ultimately, burnout. As such, a worker who is also a student will, by definition, have fewer resources at either domain (work, social life, or family), as opposed to a worker who does not engage in any form of higher education at all. Working students are under severer time constraints than non-student employees because they face “work–study conflict.” Therefore, compared to non-student workers, working students have difficulty in devoting so much time and physical as well as psychological effort to work. Specifically, working students with a low level of motivation may take an interest in studies and thus not be likely to devote much effort to work. However, motivated working students will maintain their effort through effective time management because they highly value their current work. Thus, JE and HWI of working students will depend on their motivation to a greater degree than non-student workers. Ergo, we posit that the associations between intrinsic/extrinsic motivation and HWI and JE are conditioned by the type of worker under investigation.

For the current study, the notion of working students versus non-student employees would be gauged, as not much attention was given to distinguishing both groups in research. Usually, samples were composed of either group distinctively, not in tandem with one another. Hence, we hypothesize the following, based on our previous hypotheses:

H6: Worker’s status moderates the relationship between intrinsic motivation and HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, such that the relationship will be weaker for working students than for non-student employees.

H7: Worker’s status moderates the relationship between extrinsic motivation and HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, such that the relationship will be weaker for working students than for non-student employees.

Country Difference—Buffering Effect

Worker’s status’ moderation of the links between intrinsic/extrinsic motivation to HWI and JE, as mentioned above, does not appear in a vacuum. This conditioning may also be dependent on international cultural differences. That is to say, we assume that we would receive different results based on the country under investigation because the social, work, cultural, and national values differ from one country to another. Firstly, culture, in this sense, may be defined as “common patterns of beliefs, assumptions, values, and norms of behavior of human groups (represented by societies, institutions, and organizations)” ( Aycan et al., 2000 , p. 194). As mentioned, countries differ from one another in many aspects. The most prominent example is the cultural/national dimensions devised by Hofstede (1980 , 1991) . Different countries display different cultural codes, norms, and behaviors, which may affect their market and work values and behaviors. As such, it is safe to assume that work-related norms and codes differ from one country to another to the extent that working students may exhibit or express certain attitudes and behaviors in country X, but different ones in country Y. The same goes for non-student (or “regular”) workers, as well.

In this study, we examine the case of Israel’s versus Japan’s different situation and cultural perspectives in the work sense. Japan’s culture is more hierarchical and formal than the Israeli counterpart. Japanese believe efforts and hard work may bring “anything” (e.g., prosperity, health, and happiness), while in Israel, there is much informal communication, and “respect” is earned by (hands-on) experience, not necessarily by a top-down hierarchy. Japanese emphasize loyalty, cohesion, and teamwork ( Deshpandé et al., 1993 ; Deshpandé and Farley, 1999 ). Compared to Israeli, Japanese employees are more strongly required to conform to the organization’s norm and dedicate themselves to the organization’s future. Such cultural characteristics may affect the working attitudes and behavior of working students. Specifically, in Japan, working students try to devote as much time as possible even if they are under severe time constraints caused by the study burden. Moreover, sometimes, they experience guilt because they use their time for themselves (i.e., study) rather than for the firm (e.g., socializing with colleagues). Thus, they engage in much overtime work as a tactic of impression management ( Leary and Kowalski, 1990 ) to make themselves look loyal and hard working.

In addition, in Israel, there is high value to performance, while in Japan, competition (between groups, usually) is rooted in society and drives for excellence and perfection. Also, Israelis respect tradition and normative cognition. They tend to “live the present,” rather than save for the future, while Japanese people tend to invest more (e.g., R&D) for the future. Even in economically difficult periods, Japanese people prioritize steady growth and own capitals rather than short-term revenues such that “companies are not here to make money every quarter for the shareholders, but to serve the stakeholders and society at large for many generations to come” (for further reading, see Hofstede, 2018 ).

In Hofstede’s use of the term, some aspects of these cultural differences can be summarized as Japan being higher in power distance, masculinity, and long-term orientation than Israel ( Hofstede, 2018 ). These cultural differences led us to formulate the following hypotheses:

H8: Country differences condition the moderation of worker’s status on the relationship between intrinsic motivation and HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, such that the effect of worker’s status suggested in H6 will be weaker for Japanese than for Israelis.

H9: Country differences condition the moderation of worker’s status on the relationship between extrinsic motivation and HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, such that the effect of worker’s status suggested in H7 will be weaker for Japanese than for Israelis.

It is important to note, however, that H8 and H9 are also developed to increase the external validity of the research and its generalizability beyond a single culture, as Barrett and Bass (1976) noted that “most research in industrial and organizational psychology is done within one cultural context. This context puts constraints upon both our theories and our practical solutions to the organizational problem” (p. 1675).

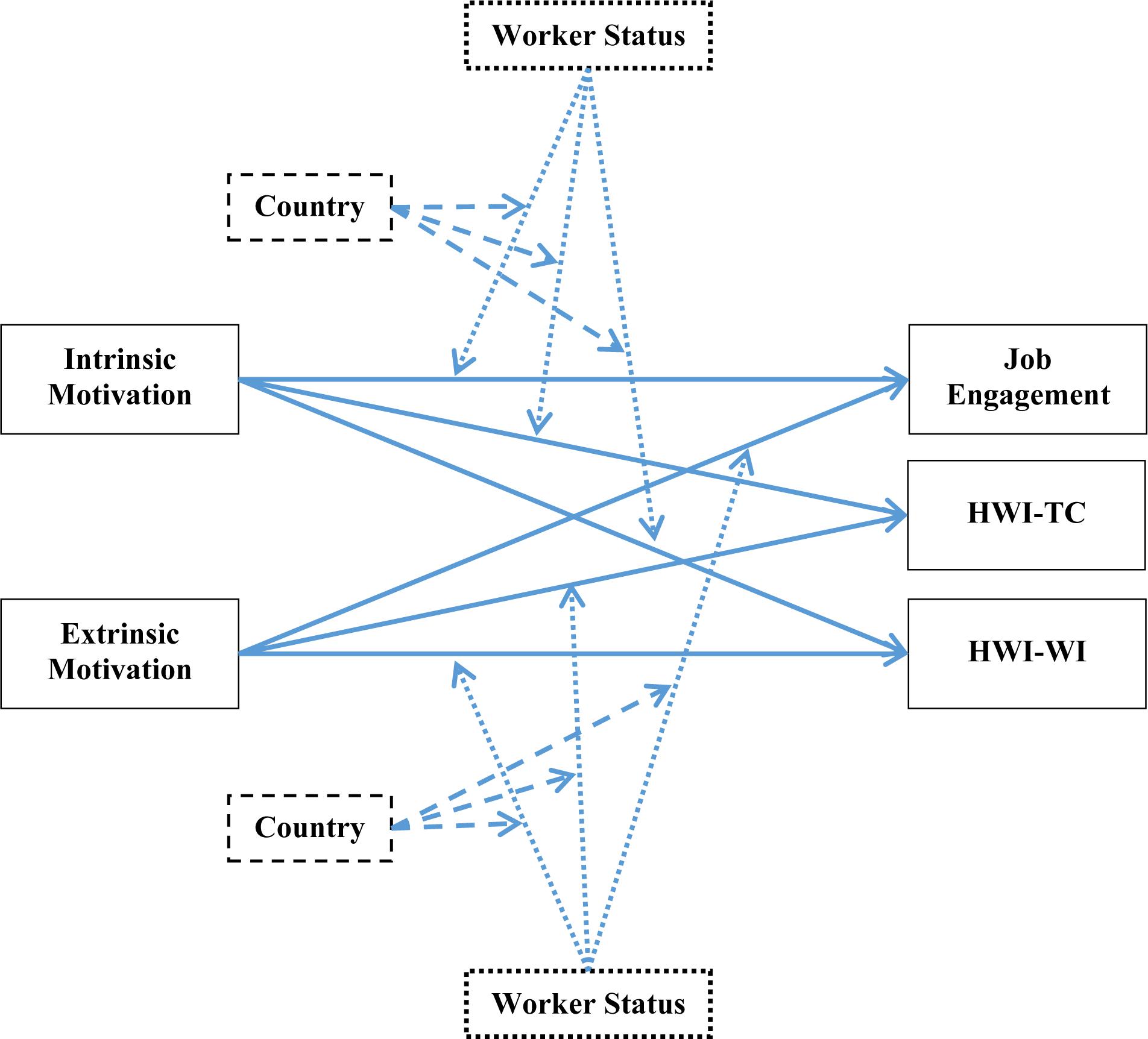

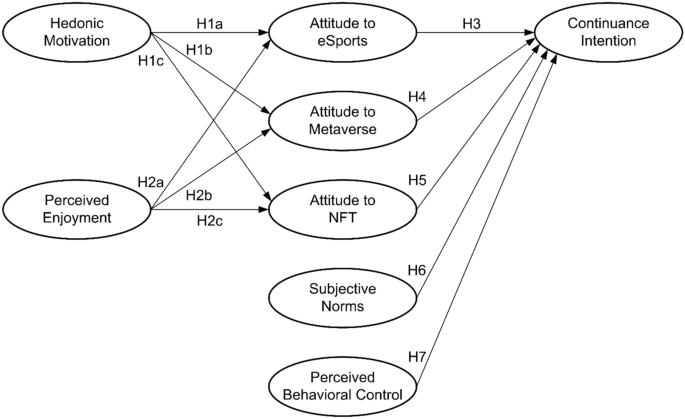

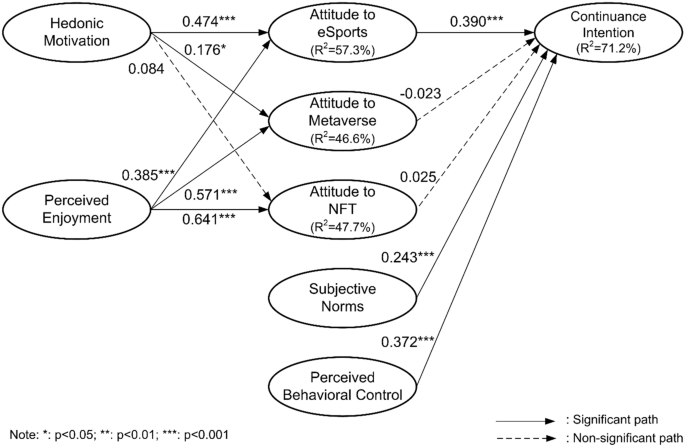

Figure 1 portrays the overall model.

Figure 1. Research model. Worker’s status: 1 = working students, 2 = non-student employees. Country: 1 = Israel, 2 = Japan. HWI-TC = time commitment dimension of heavy work investment. HWI-WI = work intensity dimension of heavy work investment.

Materials and Methods

For hypothesis testing, this study conducted questionnaire-based research using samples of company employees who also engage in a manner of higher education (i.e., working students) and those who do not (i.e., “regular” or non-student employees). Since working students in both countries do not concentrate in specific age groups, industries, or functional areas, participants were recruited from various fields. Moreover, to reduce the impact of organization-specific culture, we collected data from various companies rather than from a specific company, in both countries.

Participants

The research constitutes 242 Israeli (70.9% response rate) and 171 Japanese (56.6% response rate) participants, from various industries and organizations. The demographical and descriptive statistics for each sample are presented in Table 1 . The table also contains the result of group difference tests, pointing at some demographic differences between Israeli and Japanese samples. Therefore, the following analyses include these demographics as control variables to control their potential influence on the research model and reduce the problem that would arise from said differences between the two countries.

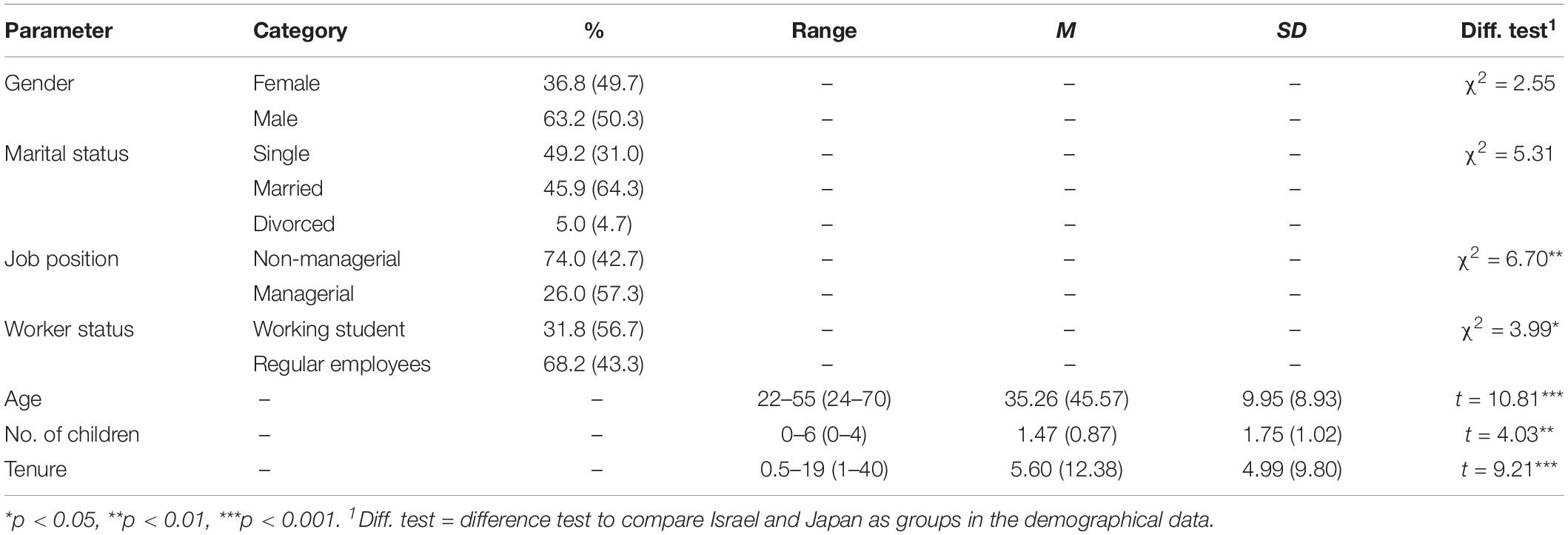

Table 1. Demographical and descriptive statistics for the Israeli ( N = 242) and the Japanese ( N = 171; in parenthesis) samples.

The items of the questionnaire were initially written in English and then translated into Hebrew and Japanese, utilizing the back-translation procedure ( Brislin, 1980 ).

Work motivation was gauged by the Work Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation Scale (WEIMS; Tremblay et al., 2009 ), consisting of 18 Likert-type items ranging from 1 (“Does not correspond at all”) to 6 (“Corresponds exactly”). Intrinsic motivation had a high reliability (α Israel = 0.92, α Japan = 0.86; e.g., “…Because I derive much pleasure from learning new things”) as did extrinsic motivation (α Israel = 0.73, α Japan = 0.75; e.g., “…For the income it provides me”).

HWI (see Snir and Harpaz, 2012 ) was tapped by 10 Likert-type items ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 6 (“Strongly agree”), five items for each dimension, namely, time commitment (HWI-TC; e.g., “Few of my peers/colleagues put in more weekly hours to work than I do”) and work intensity (HWI-WI; e.g., “When I work, I really exert myself to the fullest”), respectively. HWI-TC had a high reliability (α Israel = 0.85, α Japan = 0.92) as did HWI-WI (α Israel = 0.95, α Japan = 0.91).

JE was gauged by the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-9 (UWES-9; Schaufeli et al., 2006 ) consisting of nine Likert-type items ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 6 (“Strongly agree”). The measure had a very high reliability (α Israel = 0.95, α Japan = 0.94; e.g., “I am immersed in my work”).

For the Israeli sample, a pencil-and-paper research survey was distributed to 341 total potential participants in two universities and one college. One of the authors provided the questionnaire in several courses (MBA and management, human resource management, psychology, and more), at the end of each class session. Those wishing to participate replied affirmatively and were included in the total sample. We assured the anonymity and discretion of the participants and the data derived from the research and included a conscious consent question at the beginning of the survey asking for their agreement to participate. No incentives were given whatsoever to the participants for their cooperation. A total of 341 surveys were distributed, yet only 242 came back filled, and all of them were valid to use as data in the research.

For the Japanese sample, the data were collected by using the online questionnaire system of Google spreadsheet. Invitation messages were sent to the potential respondents via email or SNS messenger with the link of the questionnaire. One of the authors contacted 189 full-time workers who participated in one or more of the following (1) strategic management and organization management classes of a Japanese private university, (2) human resource management course in an educational service company, or (3) one-off lectures conducted by the author. All of them were non-student workers, and ultimately, 97 of them answered the questionnaire in full (51.3% response rate). As for the working students, the same author reached out to three graduate schools through personal networks. Then, he asked the liaison of each school to list up working students and send them the questionnaire link by email or SNS messenger. In total, the link was sent to 113 working students (in said three universities), and 74 completed the questionnaire (65.5% response rate). Thus, the overall response rate was 56.6%.

Data Analyses

The data were analyzed utilizing the SPSS (v. 23) software package and PROCESS macro for SPSS (v. 3.3). PROCESS is an add-on macro for the SPSS and SAS software packages written by Andrew F. Hayes. It is a modeling tool based on ordinary least squares (OLS) and logistic regressions for basic and complex path analyses with strong algorithms and modular capabilities and can handle simultaneous moderation and mediations effects (including moderated-moderation effects).

The choice of PROCESS (over SEM) is based on methodological and mathematical reasons. To elaborate, holistic testing of the entire model (see Figure 1 ) via SEM will result in 15 different observed variables (including the interaction effects) and a two-group comparison, and abundant regression lines would result in a high number of degrees of freedom. It would also require a considerably higher sample size to meet the mathematical conditions for SEM. However, we should note that one of the limitations of PROCESS is the inability to test models with more than one dependent variable ( Y ) or more than one independent variable ( X ), and as such it is required to test the model (see Figure 1 ) separately—one for each predictor–criterion linkage.

Control Variables

As per Table 1 , we can see some differences between the two countries, and as such, we included them as covariates in the moderated-moderation analyses. In other words, in these analyses, we controlled for the effects of job position, age, number of children, tenure, and also gender and marital status. This is relevant for Tables 4 –6 . Evidently, the inclusion of control variables has increased the predictive capacity and goodness of our results. Gender is a dichotomous closed question with options of (1) male or (2) female. Age is an open question: “what is your age (in years)? ______.” Marital status is a closed question with options of (1) single, (2) married, (3) divorced, or (4) widowed. Number of children is an open question: “How many children do you have? ______.” Tenure is an open question: “what is your tenure at work (in years)? ______.” Job position is a dichotomous closed question with options of (1) non-managerial or (2) managerial.

Common Method Bias

Harman’s one-factor test ( Podsakoff et al., 2003 ) was used to assess the degree to which intercorrelations among the variables might be an artifact of common method variance (CMV). The first general factor that emerged from the analysis accounted only for 35.19% of the explained variance in the Israeli sample and 37.27% in the Japanese sample. While this result does not rule out completely the possibility of same-source bias (CMV), according to Podsakoff et al. (2003) , less than 50% of the explained variance accounted for by the first emerging factor indicates that CMV is an unlikely explanation of our investigation findings.

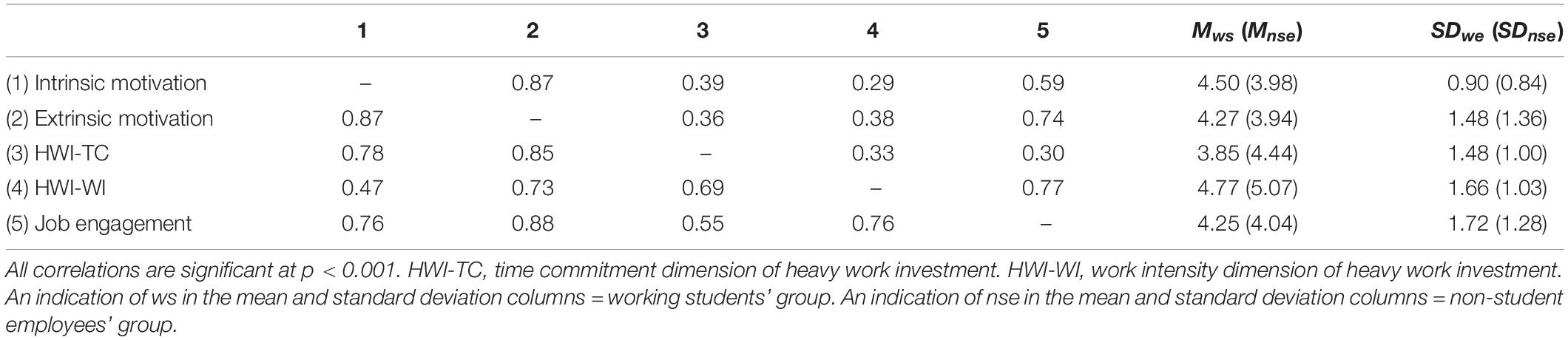

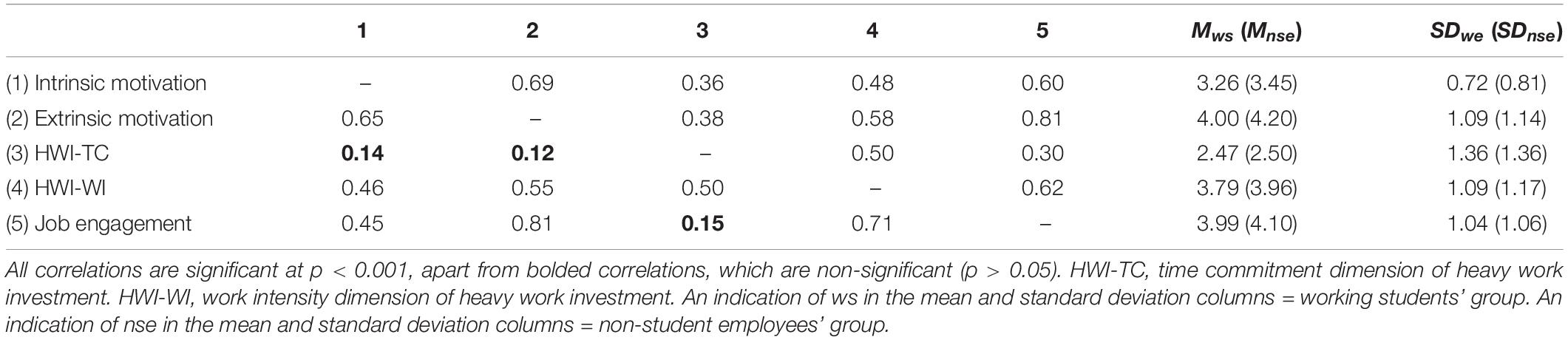

First, we explored descriptive statistics and associations between the variables. These results are displayed in Tables 2 , 3 , for each sample.

Table 2. Pearson correlation matrix for working students ( below the diagonal; n = 77) and non-student employees ( above the diagonal; n = 165), means and standard deviations in the Israeli sample ( N = 242).

Table 3. Pearson correlation matrix for working students ( below the diagonal; n = 97) and non-student employees ( above the diagonal; n = 74), means and standard deviations in the Japanese sample ( N = 171).

As shown in Table 2 , we found the following regarding the Israeli sample:

- JE positively correlates with HWI-TC for working students, r (77) = 0.55, p = 0.000, and for non-student employees r (165) = 0.30, p = 0.000 (supporting H5a, in Israel).

- JE positively correlates with HWI-WI for working students, r (77) = 0.76, p = 0.000, and for non-student employees r (165) = 0.77, p = 0.000 (supporting H5b, in Israel).

These differences in correlation coefficients are in line with our H5c, meaning JE has stronger links to HWI-WI as opposed to HWI-TC. Ergo, in order to gauge whether these differences are statistically significant, we used Fisher’s Z transformation and significance test. For working students, the difference is indeed significant ( Z = 2.31, p = 0.021) and is also for the non-student employees’ group ( Z = 6.41, p = 0.000). This supports H5c, in Israel.

Moreover, as shown in Table 3 , we found the following regarding the Japanese sample:

- JE positively correlates with HWI-TC only for non-student employees, r (74) = 0.30, p = 0.001, but is non-significant for working students, r (94) = 0.15, p = 0.146 (partially supporting H5a, in Japan).

- JE positively correlates with HWI-WI for working students, r (94) = 0.72, p = 0.000, and for non-student employees, r (74) = 0.62, p = 0.000 (supporting H5b, in Japan).

These differences in correlation coefficients are in line with our H5c, meaning JE has stronger links to HWI-WI as opposed to HWI-TC. Ergo, in order to gauge whether these differences are statistically significant, we used Fisher’s Z transformation and significance test. For working students, the difference is indeed significant ( Z = 5.12, p = 0.000) and is also significant for the non-student employees’ group ( Z = 2.48, p = 0.013). This supports H5c, in Japan.

To test the rest of our hypotheses (i.e., H1–H4 and H6–H9), we utilized the PROCESS macro for SPSS using model no. 3 for moderated moderation (95% bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples). The results from the analyses are presented in Tables 4 –6 . However, it is important to note that we also used heteroscedasticity-consistent standard error (SE) estimators, as suggested by Hayes and Cai (2007) , to ensure that the estimator of the covariance matrix of the parameter estimates will not be biased and inconsistent under heteroscedasticity violation.

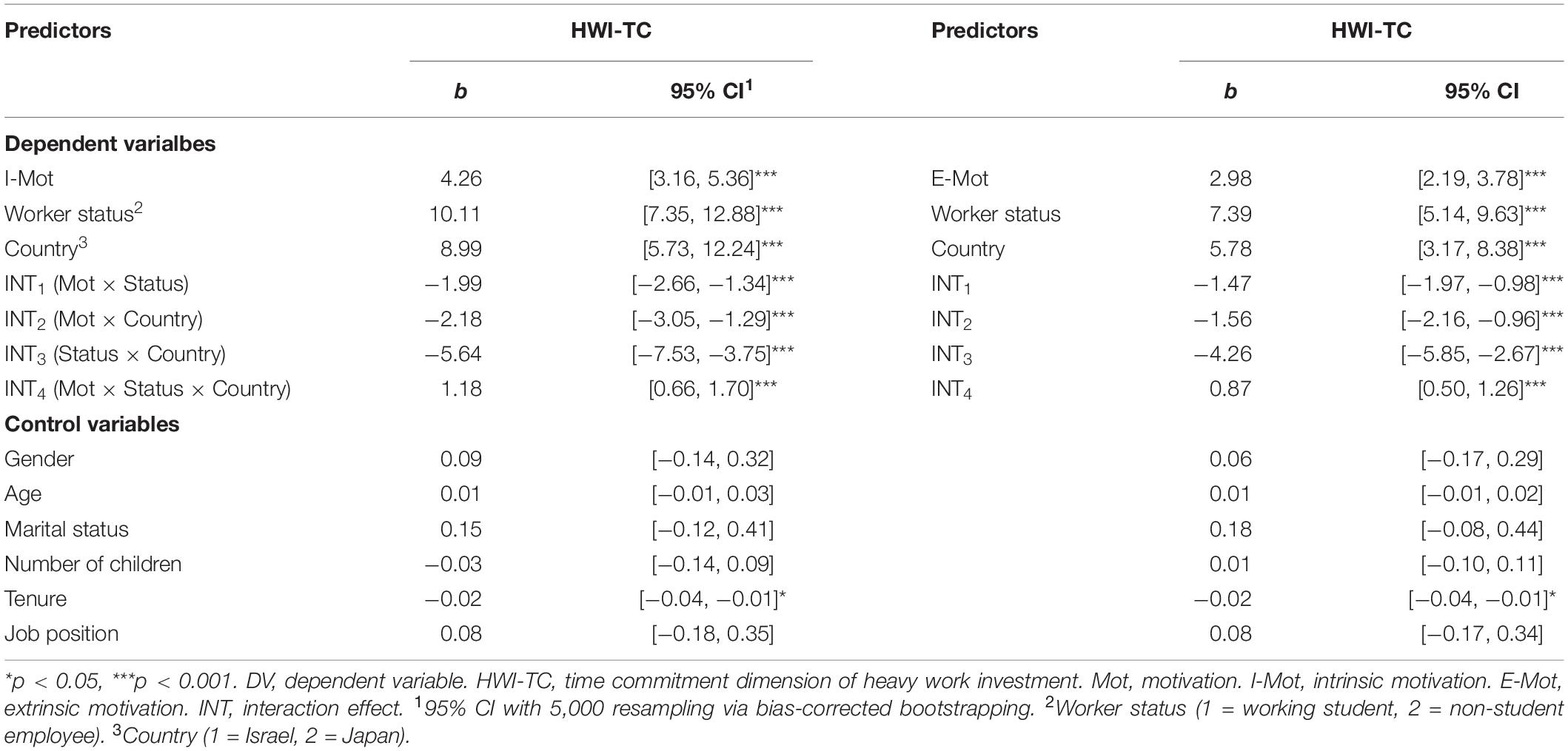

Table 4. Moderficients and confidence intervals (CIs) for predicting HWI-TC.

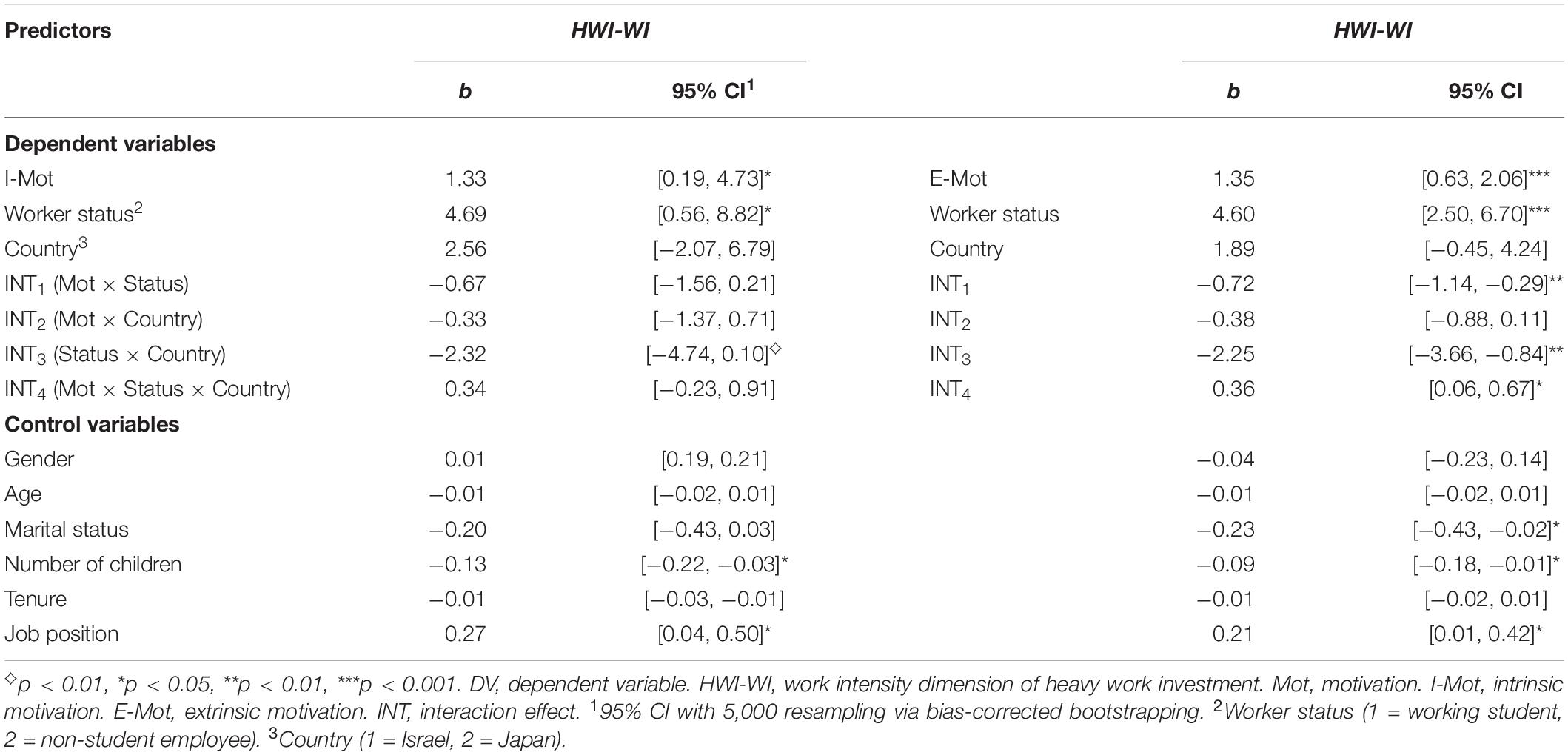

Table 5. Moderated-moderation regression coefficients and confidence intervals (CIs) for predicting HWI-WI.

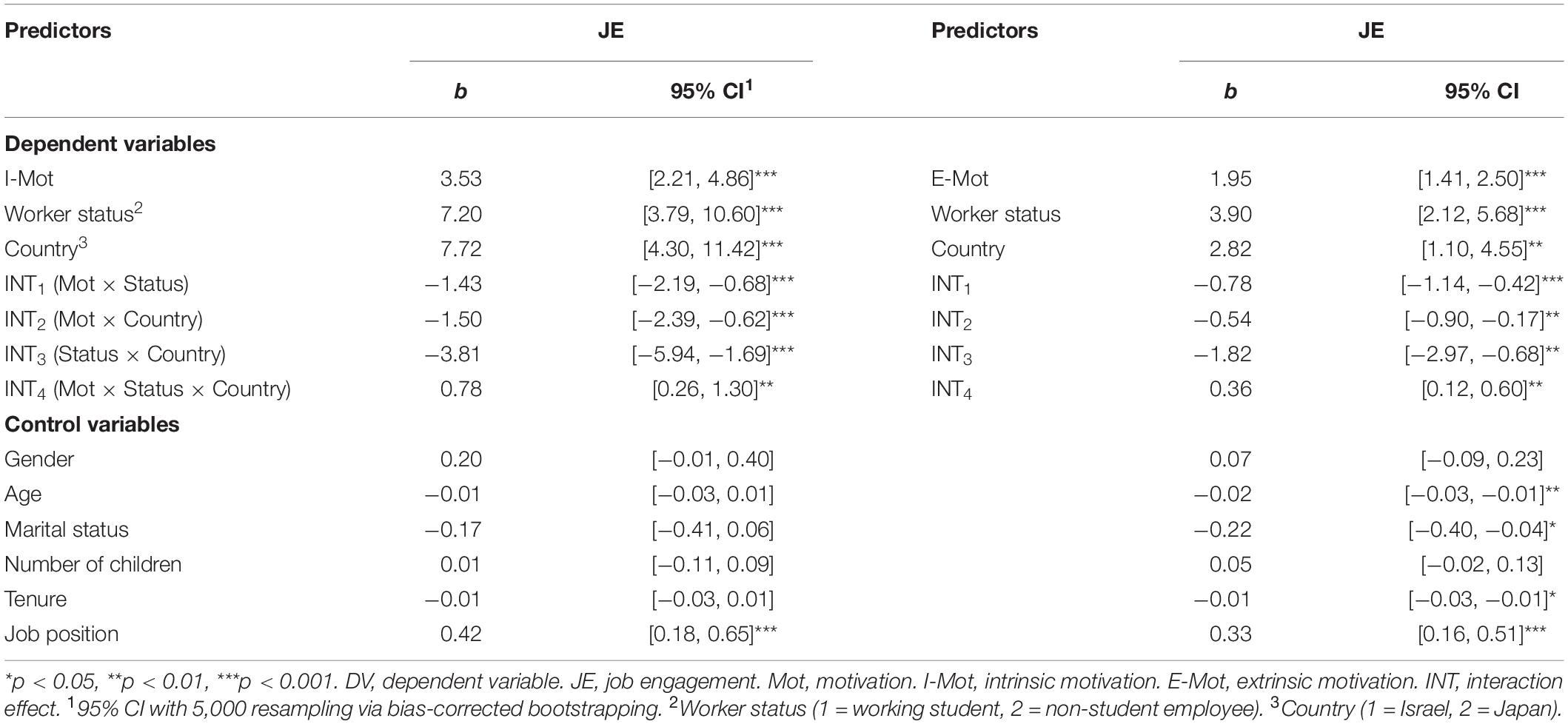

Table 6. Moderated-moderation regression coefficients and confidence intervals (CIs) for predicting job engagement (JE).

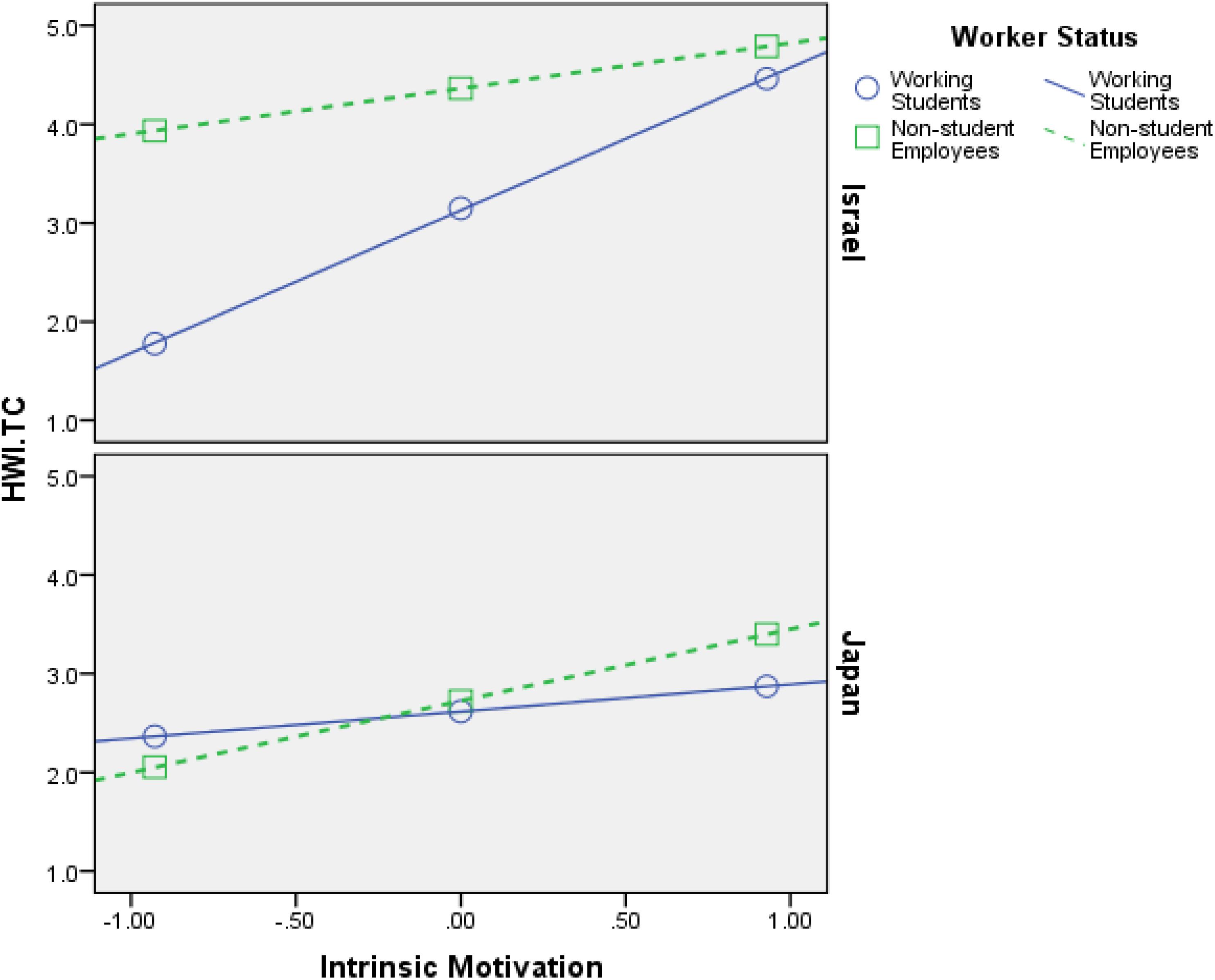

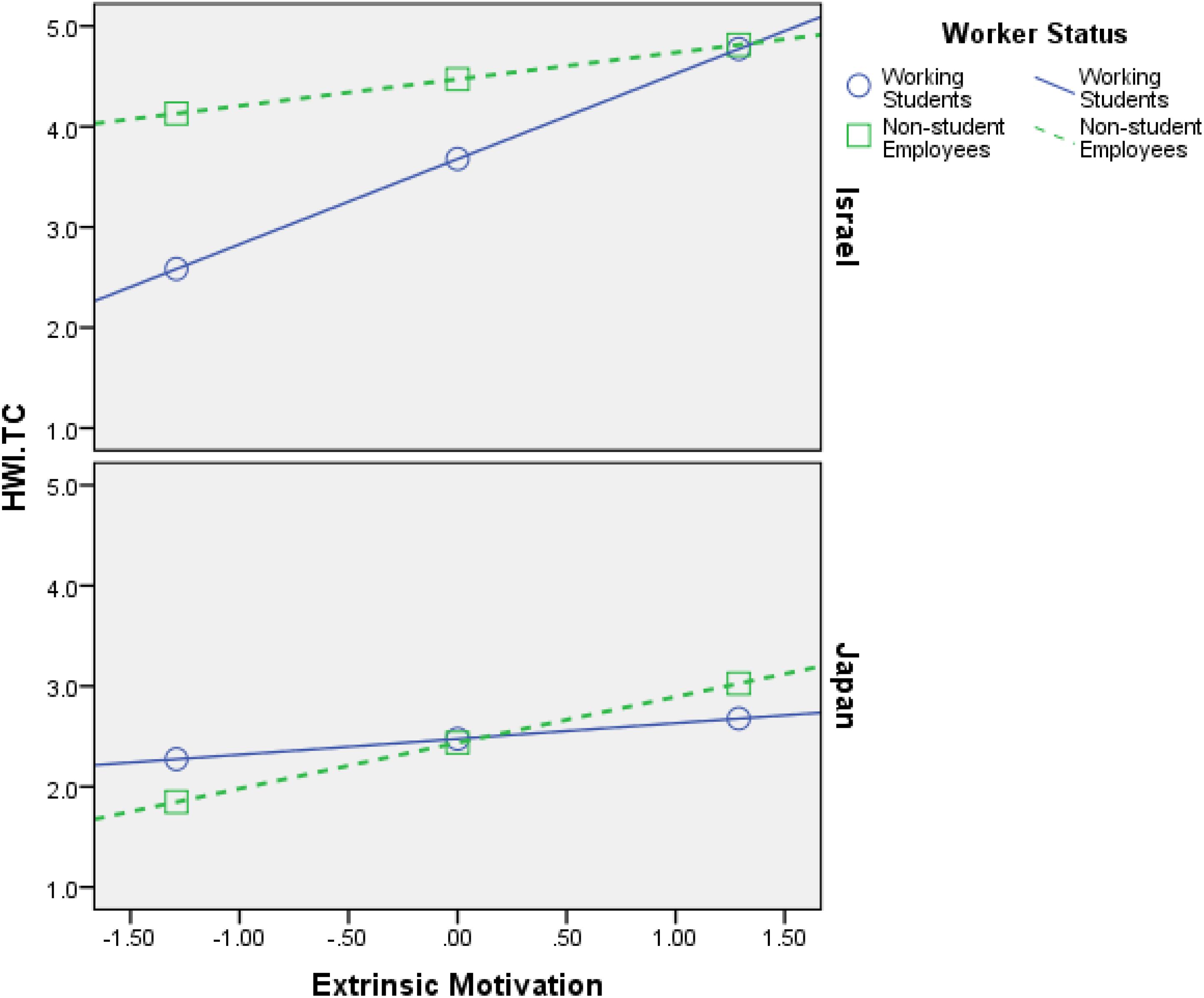

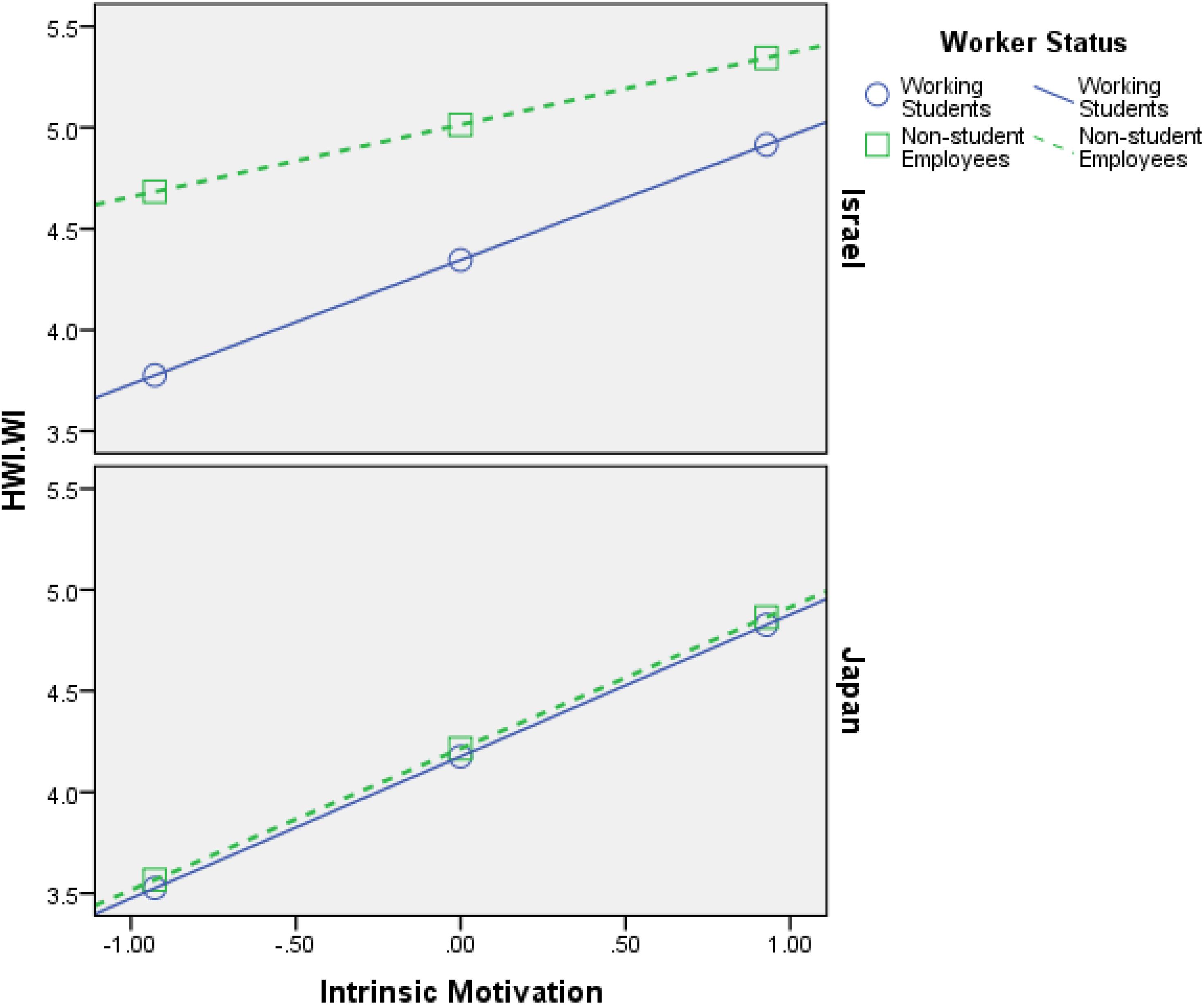

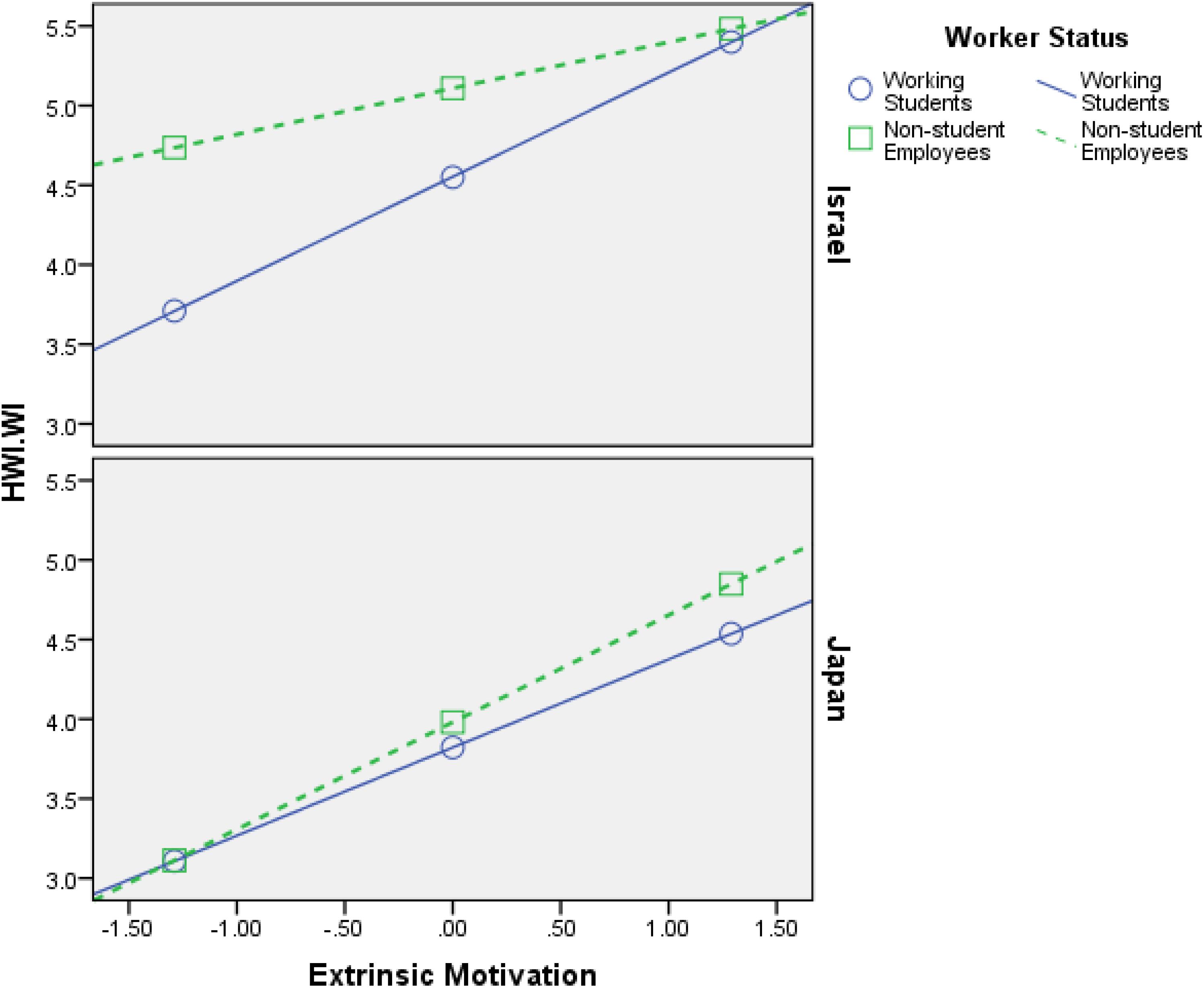

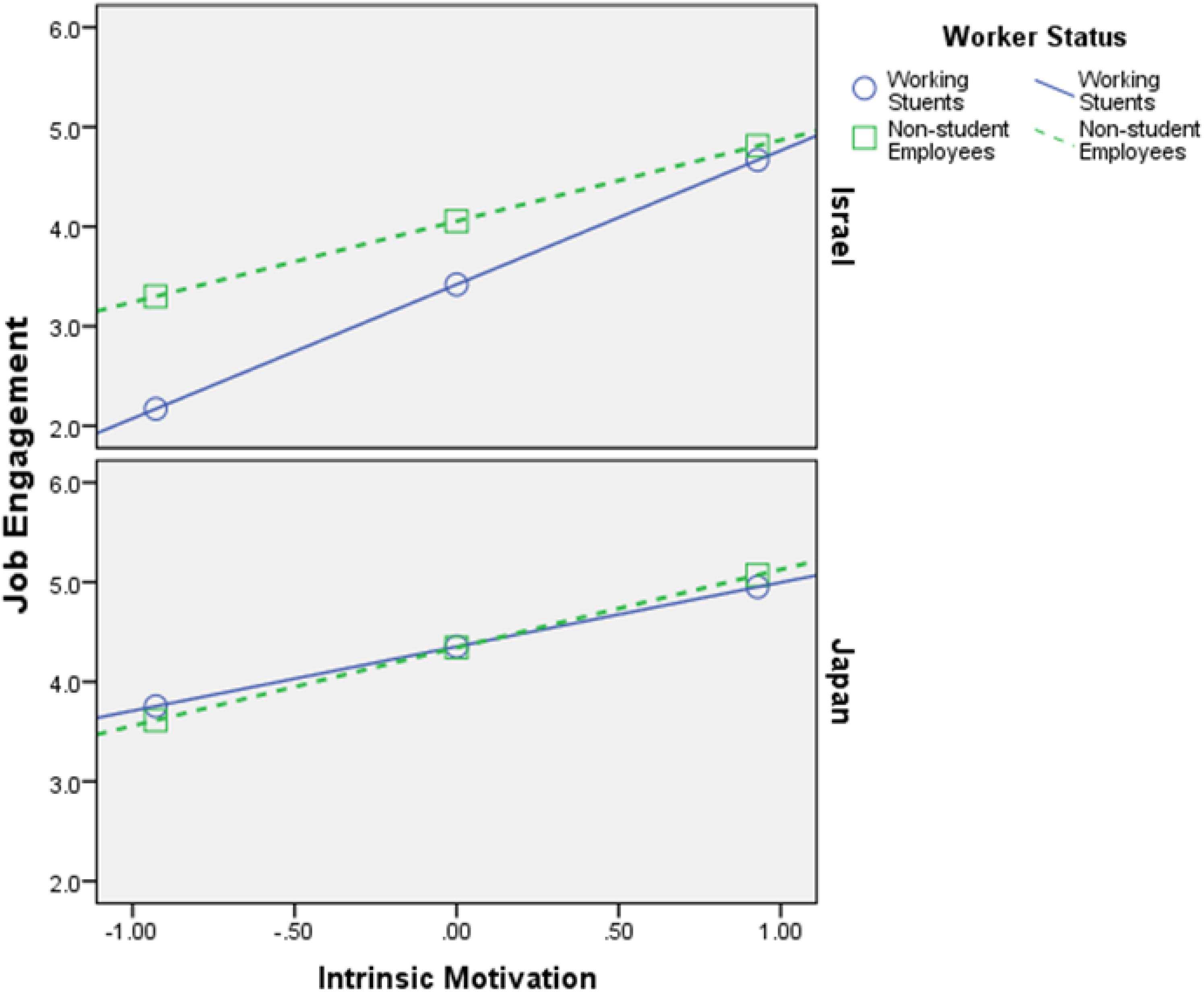

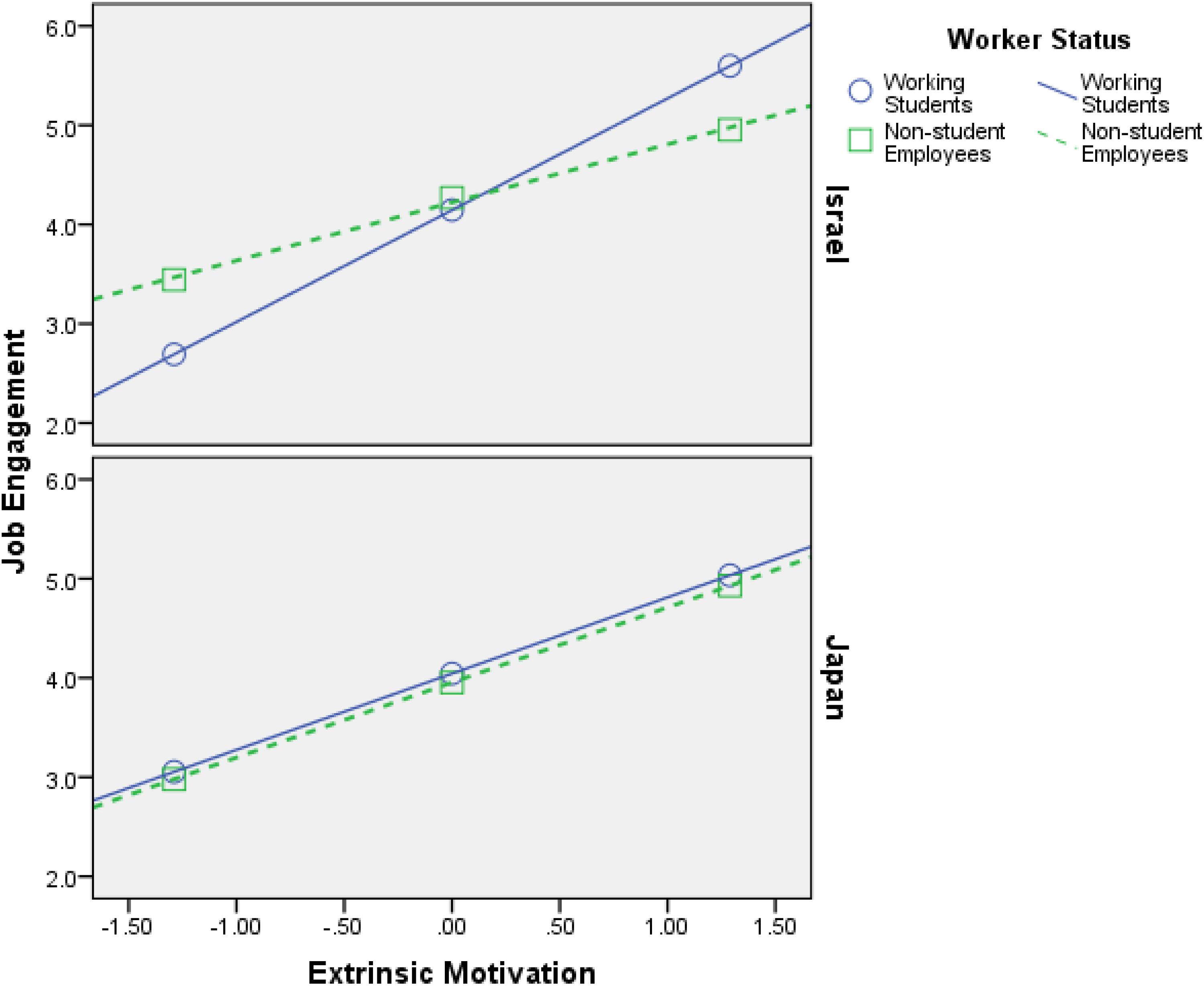

Firstly, the findings that are shown in Tables 4 –6 support H1 – H4 , meaning both intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation relate positively to HWI-TC, HWI-WI, and JE, in all samples (Israel and Japan). Additionally, the interaction effects (most of them) are significant, which is the most important part of any moderation analysis (see Appendix in Shkoler et al., 2017 ). Figures 2 –7 portray moderation effects.

Figure 2. Interaction effects of Intrinsic Motivation × Worker’s Status × Country in predicting HWI-TC. HWI-TC, time commitment dimension of heavy work investment.

Figure 3. Interaction effects of Extrinsic Motivation × Worker’s Status × Country in predicting HWI-TC. HWI-TC, time commitment dimension of heavy work investment.

Figure 4. Interaction effects of Intrinsic Motivation × Worker’s Status × Country in predicting HWI-WI. HWI-WI, work intensity dimension of heavy work investment.

Figure 5. Interaction effects of Extrinsic Motivation × Worker’s Status × Country in predicting HWI-WI. Notes . HWI-WI = work intensity dimension of heavy work investment.

Figure 6. Interaction effects of Intrinsic Motivation × Worker’s Status × Country in predicting job engagement.

Figure 7. Interaction effects of Extrinsic Motivation × Worker’s Status × Country in predicting job engagement.

Figures 2 –7 display surprising findings:

(1) The behaviors of the correlations (for instance, between intrinsic motivation and JE or HWI-TC) are different between the two countries, in general, such that means and correlations are both higher in the Israeli sample as opposed to the Japanese one.

(2) The behaviors of the correlations (for instance, between intrinsic motivation and JE or HWI-TC) are different between the two groups of worker status, in each country on its own , such that (a) working students, in Israel, exhibit stronger links to the outcome variables (i.e., HWI-TC, HWI-TC, and JE) as opposed to non-student employees; (b) however, in most cases, these associations were not so different between said groups, in the Japanese sample.

(3) The behaviors of the correlations (for instance, between intrinsic motivation and JE or HWI-TC) are different between the two groups of worker status when comparing each country, such that (a) working students, in Israel, exhibit stronger links to the outcome variables as opposed their Japanese counterparts; (b) however, in most cases, these associations were not so different between non-student employees (in Israel vs. Japan).

(4) The only analysis in which points 1–3 above do not apply is when using intrinsic motivation to predict HWI-WI (again, in a moderated-moderation model). It suggests that intrinsic motivation’s impact on the increased effort at work changes based on neither worker status nor the country/culture.

These findings support our hypotheses H6–H9: (1) worker status does moderate the links between work motivation and the outcome variables (HWI-TC, HWI-TC, and JE), and (2) county/cultural differences can moderate said relationships as well. Still, more importantly, they work as a conditioning moderator on the previous moderation (i.e., moderated moderation) in all of the analyses done.

The aims of the current paper were (1) to shed light on the relationship between intrinsic/extrinsic motivation and HWI of time (HWI-TC) and effort (HWI-WI) and JE, (3) to assess convergent and discriminant properties of JE in relation to HWI-TC and HWI-WI, and (4) to gauge the moderation effects of both worker status (working students vs. non-student employees) and country/culture (Israel vs. Japan) on said relationships (point 1) in a moderated-moderation analysis type. Our research hypotheses were supported to a great extent. The findings are summarized in Table 7 .

Table 7. Results of hypothesis testing.

Theoretical Implications

Our research adheres to the very few studies that have tested and validated Snir and Harpaz’s (2015) HWI conceptual model between its various predictors (i.e., intrinsic/extrinsic motivation) with regards to specific moderators (e.g., worker’s status and country/culture). Our findings supported the model (see Snir and Harpaz, 2015 , p. 6) and contributed to its incremental validity. Apart from realizing parts of the model’s structure and processes, we have also shown that the moderation effects suggested in the model may be conditioned by other moderators as well (in our study, country/culture differences), leading to more need for further research.

Although it is not the main focus of the current research, we have established some convergent and discriminant validity relationship between JE and HWI. Specifically, JE has a high convergent validity with HWI-WI, yet low convergent-borderline-discriminant validity with HWI-TC, increasing the need for exploring these issues further.

We have provided more evidence as to the critical role of culture in differentiating model and relationship behaviors. Our findings regarding the between-country differences found in the moderating effects of workers’ status supported our hypotheses, suggesting that compared to Israeli workplaces, those in Japan, indeed, put much emphasis in loyalty and cohesion. Japanese working students show similar work behavior (i.e., JE and HWI) as non-student workers. Attitudes, norms, and behavioral codes accepted in a country X may be quite different in country Y, not only in the general society but at the workplace as well. Concerning the workers’ status, it seems plausible that employees’ differing perceptions of the work context may affect their “readiness” to translate a drive to work to an actual HWI of JE, alone or in conjunction with cultural perceptions as well.

Furthermore, our findings on between-country differences have important insights for research in organizational learning. Employees’ continuous learning is essential for organizations to be competitive in the current and future VUCA world. Therefore, an organization needs to provide employees with opportunities to learn and support, which enables them to manage their work–study conflict effectively. However, as suggested in the results of the Japanese sample, it may be possible that cultural norms restrain workers from dedicating their time to learning. In addition to the effects of organization-level human resource development climate ( Chaudhary et al., 2012 ), we also need to consider the effects of national-level culture in the examination of organizational learning practices and their consequences.

Practical Implications

If JE is an organizational goal toward which many workplaces strive, their respective managers may very well need to enhance employees’ work motivation (such as offering more rewards or challenge), thus increasing the employees’ propensity for translating that motivation into actual HWI or JE.

The moderation effects emphasize the need for smart and careful management in workplaces with international employees, as we notice how different Israel is from Japan, for example. Managers and even service-givers must pay attention to these cultural differences when doing work with or for an entity (e.g., country, organization, or group) from outside the providing side’s national boundaries.

Besides, the stronger associations between work motivation and JE or HWI in Israeli sample (see Figures 2 –7 ) suggest that working students virtually actuate more of their working drives into the behavioral expressions of their drives to work, thus investing heavier in them. That may be so because working students are keener on proving themselves to the organization toward the end goal of being recruited as permanent employees (supported by the results in Israel, as opposed to Japan). Hence, those who have less occupational security are more likely to translate their drive to work into actual HWI and JE. Nevertheless, in today’s economy, in which “occupational sense of security” appears to be declining, it seems plausible that in the future the moderated association between motivation and HWI, found in our paper, will diminish in strength or even dissipate entirely. This argumentation finds support in recent publications (e.g., Neuner, 2013 ; Koene et al., 2014 ; Weil, 2014 ). Perhaps working students are also more susceptible to organizational incentives (i.e., intrinsic or extrinsic), as opposed to their non-student counterparts (i.e., “regular” employees).

On the other hand, Japanese workers showed relatively weak relationships between work motivation and JE or HWI. These findings suggest that the Japanese workplace norm restrains working students from putting much effort to study, and thus, they work long hours for managing impression or making up for their “violation” of the workplace norm. Such workplace derives from traditional Japanese culture which emphasizes loyalty and dedication to the employer ( Blomberg, 1994 ), and even modern companies in Japan expect employees to dedicate most of their life to the organization, resulting in much overtime work of Japanese workers ( Franklin, 2017 ; Pilla and Kuriansky, 2018 ; Mason, 2019 ). Therefore, to encourage employees’ continuous learning and associating organizational learning, managers in Japanese firms need to reconstruct the workplace norm such that working students will not feel guilty by studying outside of their organization.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

While our study has strength in the newness of findings and the use of an international sample, we should mention its limitations. First, our data are cross-sectional and single sourced. It limits the generalizability of the research and does not let us see if the findings are stable across time. Although it may not be a major limitation, our research was not focused on a specific industry, sector, or type of workers (e.g., high-tech, low-tech, services, or marketing and sales). While this bolsters the external validity of the research, it limits the construct validity of the results.

In our model, we included only individual differences as predictors and only contextual elements as moderators. As such, we recommend using a mix of said variables, such as “place” in the model, as predictors and moderators, so as not to be limited to one direction of explanations. For Snir and Harpaz’s (2015) model of HWI (p. 6), we only validated a part of it but did not include HWI as a mediator, but only as an outcome. Thus, we recommend using the full model to shed light on its possible processes, beyond predictor–outcome relationships. In addition, we urge researchers to investigate and identify more potentially interesting and relevant moderators, as we showed in our model (i.e., country/culture differences).

To expand our understanding of cultural difference, we recommend replicating our study in other countries with cultural similarities or differences to the ones used in the research, to broaden the generalizability and validity of our findings. As we noted previously, In Hofstede’s use of the term, Japan is higher in power distance, masculinity, and long-term orientation than Israel. Thus, this study might reveal the moderating effects of both these cultural dimensions and the worker’s status. However, this study only includes two countries, which might limit the generalizability of the results. Therefore, we suggest scholars worldwide to not only replicate our research in other countries but to also consider other cultural dimensions to generalize and expand our findings. Furthermore, in future international comparative studies, researchers can explore why and how each country’s cultural and institutional components influence the differences that would exist between countries.

Concerning our findings regarding convergent and discriminant validity between JE and HWI, we also encourage more research to be done in order to provide a clearer picture regarding these validity issues we raised in the current study.

We suggest conducting longitudinal studies incorporating other potential moderator variables (such as work ethic and gender) or mediators (as previously mentioned) and further investigating processes—which we enumerated in the discussion section—as likely to connect work motivation to JE, HWI, and potential outcomes.

It is also safe to assume that the associations we discovered in the research would be dependent on which industry we focus on (e.g., high-tech, low-tech, marketing, or service), and as such, we would also suggest incorporating this element in future research.

Finally, we suggest that future research compare the effect of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on various kinds of behavior using the same sample. Although this study is one of few studies that investigate the effect of both types of motivation in one study, it assumed that they result in similar attitude and behavior. As Ryan and Deci (2000a) argued, these two types of behavior can lead different kinds of behavior since their sources are different—that is, intrinsic motivation derives from one’s free choice, but extrinsic motivation is promoted by external controls. Therefore, future research can include various kinds of behavior in a model and explore whether these two types of motivation lead to a different behavior and why.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The procedure of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hosei University Graduate School of Career Studies. The committee approved that this study does not contain ethical flaws like leaking of private information and inhumane questions in the questionnaire. All subjects gave written informed consent regarding the purpose of research, that of data collection, and the privacy protection method. The current study was correlational, based on a survey, and not a manipulation on subjects. At the beginning of each questionnaire, we explained the general goal of the research. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. We ensured anonymity and discretion of the results and also ensured that the subjects know they could leave the participation at any time they choose.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Alarcon, G. M., and Edwards, J. M. (2011). The relationship of engagement, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Stress Health 27, e294–e298. doi: 10.1002/smi.1365

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R., Mendonca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J., Stahl, G., et al. (2000). Impact of culture on human resource management practices: a 10-country comparison. Appl. Psychol. 49, 192–221. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00010

Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K., and Fletcher, L. (2017). The meaning, antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement: a narrative synthesis. Int. J. Manag. Rev 19, 31–53. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12077

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., and Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: an emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress 22, 187–200. doi: 10.1080/02678370802393649

Barrett, G. V., and Bass, B. M. (1976). “Cross-cultural issues in industrial and organizational psychology,” in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology , ed. M. Dunnette, (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally), 1639–1686.

Google Scholar

Basit, A. A. (2017). Trust in supervisor and job engagement: mediating effects of psychological safety and felt obligation. J. Psychol. 151, 701–721. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2017.1372350

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bauer, K. N., Orvis, K. A., Ely, K., and Surface, E. A. (2016). Re-examination of motivation in learning contexts: meta-analytically investigating the role type of motivation plays in the prediction of key training outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 31, 33–50. doi: 10.1007/s10869-015-9401-1

Blomberg, C. (1994). The Heart of the Warrior: Origins and Religious Background of the Samurai System in Feudal Japan. New York, NY: Routledge.

Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Derks, D. (2016). Who takes the lead? A multi-source diary study on leadership, work engagement, and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 37, 309–325. doi: 10.1002/job.2041

Brislin, R. W. (1980). “Translation and content analysis of oral and written material,” in Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology , eds H. C. Triandis and J. W. Berry, (Boston: Allyn and Bacon), 389–444.

Caruso, C. C. (2014). Negative impacts of shiftwork and long work hours. Rehabil. Nurs. 39, 16–25. doi: 10.1002/rnj.107

Chaudhary, R., Rangnekar, S., and Barua, M. K. (2012). Relationships between occupational self efficacy, human resource development climate, and work engagement. Team Perform. Manag. 18, 370–383. doi: 10.1108/13527591211281110

Chughtai, A. A., and Buckley, F. (2011). Work engagement: antecedents, the mediating role of learning goal orientation and job performance. Career Dev. Int. 16, 684–705. doi: 10.1108/13620431111187290

Corrales-Herrero, H., and Rodríguez-Prado, B. (2018). The role of non-formal lifelong learning at different points in the business cycle. Int. J. Manpow. 39, 334–352. doi: 10.1108/IJM-08-2016-0164

Dawson, C., Veliziotis, M., and Hopkins, B. (2017). Temporary employment, job satisfaction and subjective well-being. Econ. Indust. Democracy 38, 69–98. doi: 10.1177/0143831X14559781

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., and Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 125, 627–668. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Deshpandé, R., and Farley, J. U. (1999). Corporate culture and market orientation: comparing Indian and Japanese firms. J. Int. Mark. 7, 111–127. doi: 10.1177/1069031x9900700407

Deshpandé, R., Farley, J. U., and Webster, F. E. Jr. (1993). Corporate culture, customer orientation, and innovativeness in Japanese firms: a quadrad analysis. J. Mark. 57, 23–37. doi: 10.2307/1252055

Franklin, S. (2017). Japanese Business Culture: A Study on Foreigner Integration and Social Inclusion. Honors thesis, Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, KY.

Gyu Park, J., Sik Kim, J., Yoon, S. W., and Joo, B. K. (2017). The effects of empowering leadership on psychological well-being and job engagement: the mediating role of psychological capital. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 38, 350–367. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-08-2015-0182

Hayes, A. F., and Cai, L. (2007). Using heteroskedasticity-consistent standard error estimators in OLS regression: an introduction and software implementation. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 709–722. doi: 10.3758/BF03192961

Hernandez, M., and Guarana, C. L. (2018). An examination of the temporal intricacies of job engagement. J. Manag. 44, 1711–1735. doi: 10.1177/0149206315622573

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organization: Software of the Mind. London, UK: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2018). The 6-D Model – Countries Comparison. Available at: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/israel,japan/ (accessed January 19, 2019).

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.5465/256287

Kanfer, R. (2009). Work motivation: identifying use-inspired research directions. Indust. Organ. Psychol. 2, 77–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9434.2008.01112.x

Kanfer, R., Frese, M., and Johnson, R. E. (2017). Motivation related to work: a century of progress. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 338–355. doi: 10.1037/apl0000133

Koene, B. A., Galais, N., and Garsten, C. (eds) (2014). Management and Organization of Temporary Agency Work. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kumar, M., Jauhari, H., Rastogi, A., and Sivakumar, S. (2018). Managerial support for development and turnover intention: roles of organizational support, work engagement and job satisfaction. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 31, 135–153. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-06-2017-0232

Latham, G. P., and Pinder, C. C. (2005). Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 485–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142105

Latta, G. F., and Fait, J. I. (2016). Sources of motivation and work engagement: a cross-industry analysis of differentiated profiles. J. Organ. Psychol. 16, 29–44.

Leary, M. R., and Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: a literature review and two-component model. Psychol. Bull. 107, 34–47. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.1.34

Lebron, M., Tabak, F., Shkoler, O., and Rabenu, E. (2018). Counterproductive work behaviors toward organization and leader-member exchange: the mediating roles of emotional exhaustion and work engagement. Organ. Manag. J. 15, 159–173. doi: 10.1080/15416518.2018.1528857

Legault, L. (2016). “Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation,” in Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences , eds Z. H. Virgil and T. K. Shackelford, (New York, NY: Springer), 1–3.

Macey, W. H., and Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Indust. Organ. Psychol. 1, 3–30.

Mason, S. (2019). Teachers, Twitter and tackling overwork in Japan. Issues Educ. Res. 29, 881–898.

Neuner, J. (2013). 40% of America’s Workforce Will be Freelancers by 2020. Available at: https://qz.com/65279/40-of-americas-workforce-will-be-freelancers-by-2020/ (accessed January 19, 2019).

Owens, B. P., Baker, W. E., Sumpter, D. M., and Cameron, K. S. (2016). Relational energy at work: implications for job engagement and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 101, 35–49. doi: 10.1037/apl0000032

Palloff, R. M., and Pratt, K. (2003). The Virtual Student: A Profile and Guide to Working with Online Learners. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Pilla, D., and Kuriansky, J. (2018). Mental health in Japan: intersecting risks in the workplace. J. Stud. Res. 7, 38–41.

Pinder, C. C. (2008). Work Motivation in Organizational Behavior , 2nd edn, New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rabenu, E., and Aharoni-Goldenberg, S. (2017). Understanding the relationship between overtime and burnout. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 47, 324–335. doi: 10.1080/00208825.2017.1382269

Rich, B. L., LePine, J. A., and Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 53, 617–635. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.51468988

Rockmann, K. W., and Ballinger, G. A. (2017). Intrinsic motivation and organizational identification among on-demand workers. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 1305–1316. doi: 10.1037/apl0000224

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000a). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000b). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., and Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire. Educ. Psychol. Measur. 66, 701–716. doi: 10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., and Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happ. Stud. 3, 71–92. doi: 10.1023/A:1015630930326

Shahpouri, S., Namdari, K., and Abedi, A. (2016). Mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between job resources and personal resources with turnover intention among female nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 30, 216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.10.008

Sharoni, G., Shkoler, O., and Tziner, A. (2015). Job engagement: antecedents and outcomes. J. Organ. Psychol. 15, 34–48.

Shkoler, O., Rabenu, E., and Tziner, A. (2017). The dimensionality of workaholism and its relations with internal and external factors. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 33, 193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.rpto.2017.09.002

Snir, R., and Harpaz, I. (2012). Beyond workaholism: towards a general model of heavy work investment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 22, 232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2011.11.011

Snir, R., and Harpaz, I. (2015). “A general model of heavy work investment,” in Heavy Work Investment: Its Nature, Sources, Outcomes, and Future Directions , eds I. Harpaz and R. Snir, (New York, NY: Routledge), 3–30.

Stimpfel, A. W., Sloane, D. M., and Aiken, L. H. (2012). The longer the shifts for hospital nurses, the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction. Health Aff. 31, 2501–2509. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1377

Taris, T., van Beek, I., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). “The beauty versus the beast: on the motives of engaged and workaholic employees,” in Heavy work Investment: Its Nature, Sources, Outcomes, and Future Directions , eds I. Harpaz and R. Snir, (New York, NY: Routledge), 121–138.

Tremblay, M. A., Blanchard, C. M., Taylor, S., Pelletier, L. G., and Villeneuve, M. (2009). Work extrinsic and intrinsic motivation scale: its value for organizational psychology research. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 41, 213–226. doi: 10.1037/a0018176

Tziner, A., Buzea, C., Rabenu, E., Truta, C., and Shkoler, O. (2019). Understanding the relationship between antecedents of heavy work investment (HWI) and burnout. Econ. Amphith. 21:153

Tziner, A., Fein, E., and Oren, L. (2012). “Human motivation and performance outcomes in the context of downsizing,” in Downsizing: Is Less Still More? eds C. L. Cooper, A. Pandey, and J. C. Quick, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 103–133. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511791574.008

Weil, D. (2014). The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became so Bad for so Many and What Can be Done to Improve it ?. Master’s thesis, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

van Beek, I., Taris, T. W., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2011). Workaholic and work engaged employees: dead ringers or worlds apart? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 16, 468–482. doi: 10.1037/a0024392

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 92, 548–573. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548

Keywords : intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, heavy work investment, job engagement, work status, moderated moderation, cultural differences

Citation: Shkoler O and Kimura T (2020) How Does Work Motivation Impact Employees’ Investment at Work and Their Job Engagement? A Moderated-Moderation Perspective Through an International Lens. Front. Psychol. 11:38. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00038

Received: 27 July 2019; Accepted: 07 January 2020; Published: 21 February 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Shkoler and Kimura. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Or Shkoler, [email protected]

† These authors have contributed equally this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

EMPLOYEE MOTIVATION AND PRODUCTIVITY: A REVIEW OF LITERATURE AND IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGEMENT PRACTICE

A substantial body of theory and empirical evidence exists to attest to the fact that motivation and productivity are concepts which have been subjects of immense interest among researchers and managers. The objective of this paper is to conduct a literature review and analysis on theories and empirical evidence on the relationship between employee motivation and organizational productivity with a view to drawing important lessons for managerial practice. To achieve this, the paper conducted a review of some of the key theories and empirical studies on motivation and its impact on employee productivity drawing experiences from diverse organizational settings in Nigeria and several other countries. The study revealed that there are different factors to consider in motivating employees: some monetary or financial such as pay and others are non-financial like recognition and challenging jobs. Important implications are presented for managerial practice.

Related Papers

Sirkka Naundobe

This study examines the relationship between Motivation and Employee productivity, using First Bank Nigeria Plc. as a case study. First Bank of Nigeria, is a Nigerian multinational bank and financial services company. It is the country's largest financial services company serving about eight Million (8,000,000) strong customer base through over 750 nationwide branches , as well as online services, with its global reach and currently it is Nigerian's largest bank by assets. Just like any long standing big organization First Bank Plc. is faced with the problem of developing and sustaining staff engagement through motivation to achieve high employee and organization productivity and prevent low employee morale and low overall organizational performance, the paper aimed at identifying various strategies and motivational techniques that exist in the organization, determination of the best motivational techniques that bring the best out of employees and to determine ways of improving overall organizational performance through appropriate motivational approach. This study was carried out among the employees of First bank Nigeria Plc. spanning through branches and the headquarter in Lagos, Nigeria. 450 well –structured questionnaire were administered on the six (6) geopolitical zones of Nigeria where First Bank Plc is evenly represented in branches with a total of 300 questionnaires received back and passed through statistical analyses. Research questions were raised based on the research objectives and hypotheses. Chi () statistical test was deployed to test the various hypotheses formulated in the study. The result showed that quality of supervision has positive effect on employee motivation to work better. It was also found that workers perception on what obtained in his

Academic Research

Emmanuel O . Olusanya

Employees are a company's livelihood. How they feel about the work they are doing and the results received from that work directly impact an organization's performance and, ultimately, its stability. An unstable organization ultimately underperforms. The study had the following objectives: to find out the motivational factors put in place by the organization to enhance performance, to find out the relationship between employee motivation and performance, and to find out the challenges that organizations face in its attempt to motivate staff. To achieve these goals, a questionnaire was designed based on the objectives. The completed questionnaires were processed and analysed using the SPSS version 20 The study used descriptive sample survey for the representation and the analysis of the findings. A sample of 100 respondents was used. The study relied on both primary data, collected through a questionnaire, and secondary data collected from journals and the internet. The result shows that 11 % of the respondents functioned as management, 29 % as senior staff, 48 % as junior staffs and the remaining 12 % were contract staff. Summary of findings shows that 99% of the respondents strongly agreed that employees are motivated through monetary rewards, 65% of the respondents agreed that receiving Recognition for Work Done Affects Employees Output, one respondent was undecided while 34% strongly agreed. Finally, 98% of the respondents strongly agreed to the notion that motivated staff have higher productivity while 2% are also in agreement. The study, therefore, recommends that management should do well by adopting on the spot praise as a medium for recognition and appreciation for hard work for promptness equal effectiveness.

sherry shinwari

This study is aimed at looking into the importance of motivation in the management of people at work, no system moves smoothly without it, and no organization achieve its objective without motivating its human resources. The study therefore is to study and come out with the effect and ways of motivating worker in organization, hence comparative study of Manufacturing firms in Nnewi, Descriptive and inferential statistics were used in the analysis of the data. Necessary literatures were reviewed. During the analysis of the data it was discovered that the goal of motivation is to cause people to put fourth their best efforts with enthusiasm and effectiveness in order to achieve and hopefully surpass organizational objective. It is evidence that workers of manufacturing firms in Nnewi are poorly motivated; hence low productivity. Findings from the research on productivity of manufacturing firm's staff are reported. Two sets of questionnaires were employed in the study. One set was administered on management staff and the other on junior staff. The study reveals that salaries paid to junior staff in the company were very below the stipulations of Nigerian National Joint Industry Council. It further shows that the junior staff is rarely promoted and the junior staff prefers financial incentives than non financial incentives. The study recommended that increase in salary via promotion; overtime allowance and holiday with pay should be used as motivational tools.

FEMI P R A I S E MOYIN

Femi Praise

MOYIN P R A I S E FEMI

One of the most important functions of management is to ensure that employee work is more satisfying and to reconcile employee motivation with organizational goals. With the diversity of current jobs, this is a dynamic challenge. What people value and enjoy is influenced by many factors, including the influence of different cultural backgrounds. This research report examines employee motivation and its impact on employee performance. The study examines some common theories of motivation that can be used in an organization to improve employee performance. The study showed that employees have their differences in terms of the concept of motivation. Various forms of theories of motivation in literature have been debated along with their applications and implications. Three questions were examined: What is motivation? What kind of motivation can best be used to increase employee performance? The results of the study show that motivation can increase or decrease employee performance. If the chosen form of motivation meets the needs of the employee, their performance increases. If, on the other hand, the chosen form of motivation does not satisfy the needs of the employee, the benefit decreases. It therefore encourages organizations to understand the motivating need of each employee to improve performance.

SAU Journal of Management and Social Sciences

Prof. Oyedokun E M M A N U E L Godwin , Modupeola Adeolu-Akande

The researchers investigated the impact of motivation on employee productivity in the Nigerian Baptist Convention, Survey research design was adopted while questionnaire was used as the questionnaire of data collection. The reliability of the research instrument was calculated and all variables have Cronbach's alpha value, ranging from 0.907 to 0.935, which achieved the minimum acceptable level of coefficient alpha above 0.70. The data collected were analysed, using the Special Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) to generate tables as well as percentages. This was done to ensure an easy and clear understanding of the work. Multiple linear regression and correlation were used to test the validity of the hypotheses to establish the link between motivation and productivity. The R-square coefficient of the variables (work environment, training and development, recognition, leadership style and workers' efficiency) was 0.999. This shows that the variables constitute 99.9% of total variance which is a high coefficient on the employment motivation (dependent variable). This shows that they have a significant impact on employee motivation at Nigerian Baptist Convention. Thus, organisations, managers and employers should take the issue of motivation seriously.

SSRN Electronic Journal

Stephen Dugguh

Employees are the most important resources in any organization. They are needed to use inputs to enhance outcomes. Low productivity in manufacturing companies in Nigeria in general may be traceable to poor employee motivation. The objective of the paper therefore is to determine how certain theories of motivation could be applied to increase productivity in Cement Manufacturing Companies in Nigeria. The paper is theoretical in nature and draws from various literatures on motivation and productivity and concludes that motivation has a link to productivity since ‘motivated employees are productive employees’. The paper further suggests that relevant motivation theories should be applied to elicit and drive employee performance and increase the level of productivity in Cement Manufacturing Companies in Nigeria.

American Journal of Business and Management

Daniel Tulu

Samuel Ajayi

ABSTRACT This study examines the relationship between Motivation and Employee productivity, using First Bank Nigeria Plc. as a case study. First Bank of Nigeria, is a Nigerian multinational bank and financial services company. It is the country’s largest financial services company serving about eight Million (8,000,000) strong customer base through over 750 nationwide branches , as well as online services, with its global reach and currently it is Nigerian's largest bank by assets. Just like any long standing big organization First Bank Plc. is faced with the problem of developing and sustaining staff engagement through motivation to achieve high employee and organization productivity and prevent low employee morale and low overall organizational performance, the paper aimed at identifying various strategies and motivational techniques that exist in the organization, determination of the best motivational techniques that bring the best out of employees and to determine ways of improving overall organizational performance through appropriate motivational approach. This study was carried out among the employees of First bank Nigeria Plc. spanning through branches and the headquarter in Lagos, Nigeria. 450 well –structured questionnaire were administered on the six (6) geopolitical zones of Nigeria where First Bank Plc is evenly represented in branches with a total of 300 questionnaires received back and passed through statistical analyses. Research questions were raised based on the research objectives and hypotheses. Chi ( ) statistical test was deployed to test the various hypotheses formulated in the study. The result showed that quality of supervision has positive effect on employee motivation to work better. It was also found that workers perception on what obtained in his organization will motivate him to greater productivity. Financial motivation involving monetary rewards have greater impact on performance and organizational productivity.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Amaeshi U.F

Francis Amaeshi

American Journal of Industrial and Business Management

Morakinyo Akintolu

Girma Birhanu

Kayode O L U W A D A M I L A R E BANKOLE

Engr. Akindoyin Segun Julius

International Journal of Innovative Research and Development

Edward Affainie

Motivation And Employee Productivity Among Secondary School Teachers in Makurdi Benue State

Inedu Abraham Idoko

Adewale E. Adegoriola

UGOCHUKWU ABASILIM

Asian Social Science

Professor Lawal Mohammad Anka

UNPUBLISHED

olusegunsteve adegoke

Texila International Journal of Management

Texila International Journal

adeleke omolade

Lighthouse-pub

OPOKU P R I N C E JOSHUA , Prince Opoku Joshua

monica dita

Article in Sahel Analyst: African Journal of Management (AJOM) Vol. 2.No.1, September,

Mustapha Momoh

International Journal of Management Sciences

Joseph Odeleye

Nornubari Puedum

Matsiador Peter

Fabrice Tchakounte Kegninkeu

Reviews of Management Sciences

Sherbaz Khan

Odogwu Chidi

parveen kaur

African Journal of Management Business Admin. University of Maiduguri; ISSN 1118-6224, Vol.2, No.1

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An Empirical Study of Employees’ Motivation and Its Influence Job Satisfaction

Ali, B. J., & Anwar, G. (2021). An Empirical Study of Employees’ Motivation and its Influence Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Engineering, Business and Management, 5(2), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijebm.5.2.3

10 Pages Posted: 21 Apr 2021

Bayad Jamal Ali

Komar University for Science and Technology

Govand Anwar

Knowledge University

An Empirical Study of Employees’ Motivation and its Influence Job Satisfaction

Date Written: April 8, 2021

Human Resource Management is getting more important in the business nowadays, because people and their knowledge are the most important aspects affecting the productivity of the company. One of the main aspects of Human Resource Management is the measurement of employee satisfaction. Companies have to make sure that employee satisfaction is high among the workers, which is a precondition for increasing productivity, responsiveness, quality, and recognition service. The aim of this thesis is to analyze the level of employee satisfaction and work motivation. It also deals with the effect the culture has on employee satisfaction. The theoretical framework of this thesis includes such concepts as, job satisfaction, motivation, and rewards differences. One of the biggest strength of the organization is the relationship and communication between the employees and the managers.

Keywords: Motivation, Reward, Incentive, Recognition, Job Satisfaction

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Bayad Jamal Ali (Contact Author)

Komar university for science and technology ( email ).

Sulaimani Qularesi Kurdistan, Sulaimani Iraq

Knowledge University ( email )

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on ssrn, paper statistics, related ejournals, industrial & organizational psychology ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

How Does Work Motivation Impact Employees’ Investment at Work and Their Job Engagement? A Moderated-Moderation Perspective Through an International Lens

1 Independent Researcher, Netanya, Israel

Takuma Kimura

2 Graduate School of Career Studies, Hosei University, Tokyo, Japan

Associated Data

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.