Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper

Writing a research paper is both an art and a skill, and knowing how to write the methods section of a research paper is the first crucial step in mastering scientific writing. If, like the majority of early career researchers, you believe that the methods section is the simplest to write and needs little in the way of careful consideration or thought, this article will help you understand it is not 1 .

We have all probably asked our supervisors, coworkers, or search engines “ how to write a methods section of a research paper ” at some point in our scientific careers, so you are not alone if that’s how you ended up here. Even for seasoned researchers, selecting what to include in the methods section from a wealth of experimental information can occasionally be a source of distress and perplexity.

Additionally, journal specifications, in some cases, may make it more of a requirement rather than a choice to provide a selective yet descriptive account of the experimental procedure. Hence, knowing these nuances of how to write the methods section of a research paper is critical to its success. The methods section of the research paper is not supposed to be a detailed heavy, dull section that some researchers tend to write; rather, it should be the central component of the study that justifies the validity and reliability of the research.

Are you still unsure of how the methods section of a research paper forms the basis of every investigation? Consider the last article you read but ignore the methods section and concentrate on the other parts of the paper . Now think whether you could repeat the study and be sure of the credibility of the findings despite knowing the literature review and even having the data in front of you. You have the answer!

Having established the importance of the methods section , the next question is how to write the methods section of a research paper that unifies the overall study. The purpose of the methods section , which was earlier called as Materials and Methods , is to describe how the authors went about answering the “research question” at hand. Here, the objective is to tell a coherent story that gives a detailed account of how the study was conducted, the rationale behind specific experimental procedures, the experimental setup, objects (variables) involved, the research protocol employed, tools utilized to measure, calculations and measurements, and the analysis of the collected data 2 .

In this article, we will take a deep dive into this topic and provide a detailed overview of how to write the methods section of a research paper . For the sake of clarity, we have separated the subject into various sections with corresponding subheadings.

Table of Contents

What is the methods section of a research paper ?

The methods section is a fundamental section of any paper since it typically discusses the ‘ what ’, ‘ how ’, ‘ which ’, and ‘ why ’ of the study, which is necessary to arrive at the final conclusions. In a research article, the introduction, which serves to set the foundation for comprehending the background and results is usually followed by the methods section, which precedes the result and discussion sections. The methods section must explicitly state what was done, how it was done, which equipment, tools and techniques were utilized, how were the measurements/calculations taken, and why specific research protocols, software, and analytical methods were employed.

Why is the methods section important?

The primary goal of the methods section is to provide pertinent details about the experimental approach so that the reader may put the results in perspective and, if necessary, replicate the findings 3 . This section offers readers the chance to evaluate the reliability and validity of any study. In short, it also serves as the study’s blueprint, assisting researchers who might be unsure about any other portion in establishing the study’s context and validity. The methods plays a rather crucial role in determining the fate of the article; an incomplete and unreliable methods section can frequently result in early rejections and may lead to numerous rounds of modifications during the publication process. This means that the reviewers also often use methods section to assess the reliability and validity of the research protocol and the data analysis employed to address the research topic. In other words, the purpose of the methods section is to demonstrate the research acumen and subject-matter expertise of the author(s) in their field.

Structure of methods section of a research paper

Similar to the research paper, the methods section also follows a defined structure; this may be dictated by the guidelines of a specific journal or can be presented in a chronological or thematic manner based on the study type. When writing the methods section , authors should keep in mind that they are telling a story about how the research was conducted. They should only report relevant information to avoid confusing the reader and include details that would aid in connecting various aspects of the entire research activity together. It is generally advisable to present experiments in the order in which they were conducted. This facilitates the logical flow of the research and allows readers to follow the progression of the study design.

It is also essential to clearly state the rationale behind each experiment and how the findings of earlier experiments informed the design or interpretation of later experiments. This allows the readers to understand the overall purpose of the study design and the significance of each experiment within that context. However, depending on the particular research question and method, it may make sense to present information in a different order; therefore, authors must select the best structure and strategy for their individual studies.

In cases where there is a lot of information, divide the sections into subheadings to cover the pertinent details. If the journal guidelines pose restrictions on the word limit , additional important information can be supplied in the supplementary files. A simple rule of thumb for sectioning the method section is to begin by explaining the methodological approach ( what was done ), describing the data collection methods ( how it was done ), providing the analysis method ( how the data was analyzed ), and explaining the rationale for choosing the methodological strategy. This is described in detail in the upcoming sections.

How to write the methods section of a research paper

Contrary to widespread assumption, the methods section of a research paper should be prepared once the study is complete to prevent missing any key parameter. Hence, please make sure that all relevant experiments are done before you start writing a methods section . The next step for authors is to look up any applicable academic style manuals or journal-specific standards to ensure that the methods section is formatted correctly. The methods section of a research paper typically constitutes materials and methods; while writing this section, authors usually arrange the information under each category.

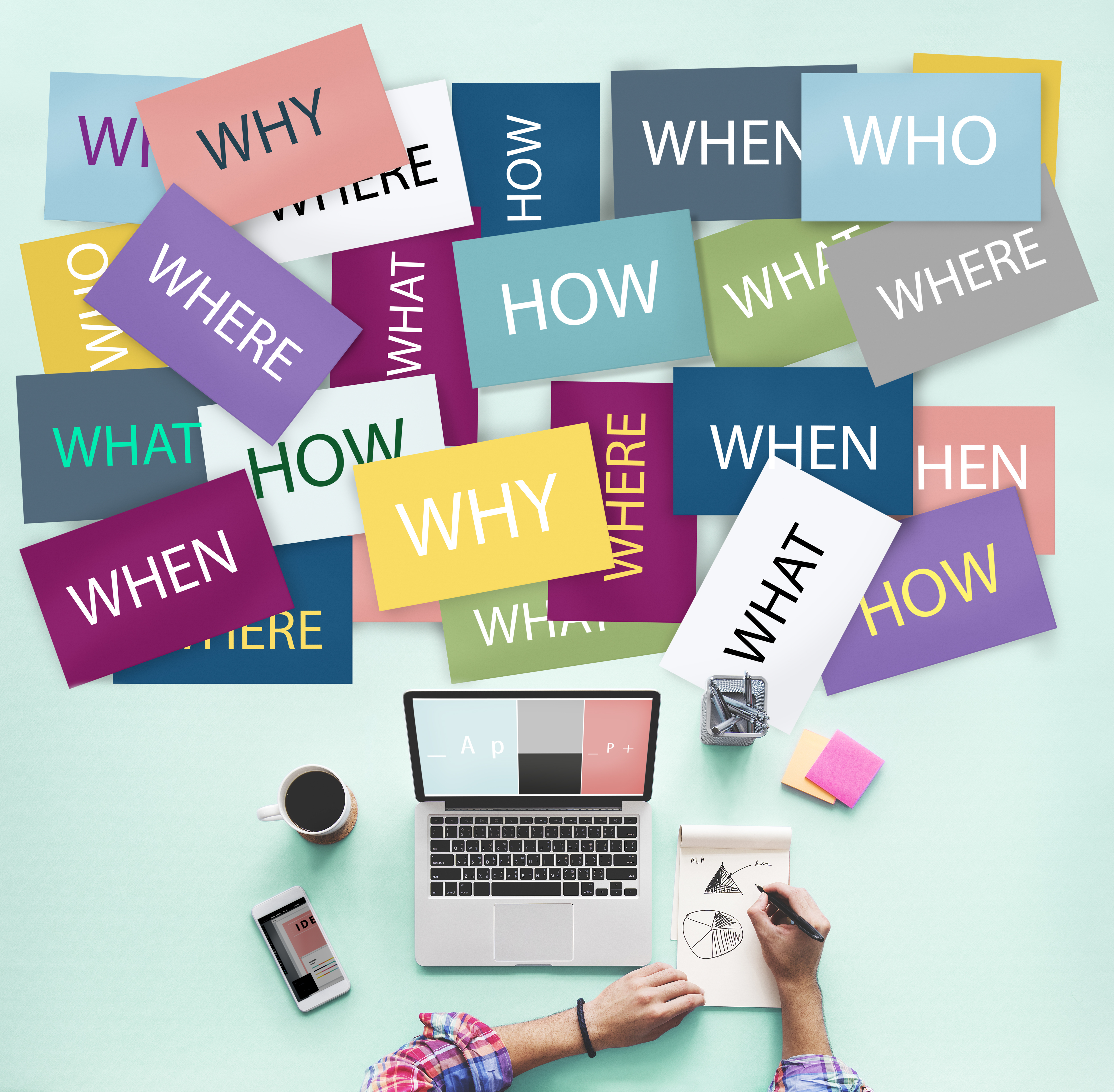

The materials category describes the samples, materials, treatments, and instruments, while experimental design, sample preparation, data collection, and data analysis are a part of the method category. According to the nature of the study, authors should include additional subsections within the methods section, such as ethical considerations like the declaration of Helsinki (for studies involving human subjects), demographic information of the participants, and any other crucial information that can affect the output of the study. Simply put, the methods section has two major components: content and format. Here is an easy checklist for you to consider if you are struggling with how to write the methods section of a research paper .

- Explain the research design, subjects, and sample details

- Include information on inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Mention ethical or any other permission required for the study

- Include information about materials, experimental setup, tools, and software

- Add details of data collection and analysis methods

- Incorporate how research biases were avoided or confounding variables were controlled

- Evaluate and justify the experimental procedure selected to address the research question

- Provide precise and clear details of each experiment

- Flowcharts, infographics, or tables can be used to present complex information

- Use past tense to show that the experiments have been done

- Follow academic style guides (such as APA or MLA ) to structure the content

- Citations should be included as per standard protocols in the field

Now that you know how to write the methods section of a research paper , let’s address another challenge researchers face while writing the methods section —what to include in the methods section . How much information is too much is not always obvious when it comes to trying to include data in the methods section of a paper. In the next section, we examine this issue and explore potential solutions.

What to include in the methods section of a research paper

The technical nature of the methods section occasionally makes it harder to present the information clearly and concisely while staying within the study context. Many young researchers tend to veer off subject significantly, and they frequently commit the sin of becoming bogged down in itty bitty details, making the text harder to read and impairing its overall flow. However, the best way to write the methods section is to start with crucial components of the experiments. If you have trouble deciding which elements are essential, think about leaving out those that would make it more challenging to comprehend the context or replicate the results. The top-down approach helps to ensure all relevant information is incorporated and vital information is not lost in technicalities. Next, remember to add details that are significant to assess the validity and reliability of the study. Here is a simple checklist for you to follow ( bonus tip: you can also make a checklist for your own study to avoid missing any critical information while writing the methods section ).

- Structuring the methods section : Authors should diligently follow journal guidelines and adhere to the specific author instructions provided when writing the methods section . Journals typically have specific guidelines for formatting the methods section ; for example, Frontiers in Plant Sciences advises arranging the materials and methods section by subheading and citing relevant literature. There are several standardized checklists available for different study types in the biomedical field, including CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) for randomized clinical trials, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis) for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, and STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) for cohort, case-control, cross-sectional studies. Before starting the methods section , check the checklist available in your field that can function as a guide.

- Organizing different sections to tell a story : Once you are sure of the format required for structuring the methods section , the next is to present the sections in a logical manner; as mentioned earlier, the sections can be organized according to the chronology or themes. In the chronological arrangement, you should discuss the methods in accordance with how the experiments were carried out. An example of the method section of a research paper of an animal study should first ideally include information about the species, weight, sex, strain, and age. Next, the number of animals, their initial conditions, and their living and housing conditions should also be mentioned. Second, how the groups are assigned and the intervention (drug treatment, stress, or other) given to each group, and finally, the details of tools and techniques used to measure, collect, and analyze the data. Experiments involving animal or human subjects should additionally state an ethics approval statement. It is best to arrange the section using the thematic approach when discussing distinct experiments not following a sequential order.

- Define and explain the objects and procedure: Experimental procedure should clearly be stated in the methods section . Samples, necessary preparations (samples, treatment, and drug), and methods for manipulation need to be included. All variables (control, dependent, independent, and confounding) must be clearly defined, particularly if the confounding variables can affect the outcome of the study.

- Match the order of the methods section with the order of results: Though not mandatory, organizing the manuscript in a logical and coherent manner can improve the readability and clarity of the paper. This can be done by following a consistent structure throughout the manuscript; readers can easily navigate through the different sections and understand the methods and results in relation to each other. Using experiment names as headings for both the methods and results sections can also make it simpler for readers to locate specific information and corroborate it if needed.

- Relevant information must always be included: The methods section should have information on all experiments conducted and their details clearly mentioned. Ask the journal whether there is a way to offer more information in the supplemental files or external repositories if your target journal has strict word limitations. For example, Nature communications encourages authors to deposit their step-by-step protocols in an open-resource depository, Protocol Exchange which allows the protocols to be linked with the manuscript upon publication. Providing access to detailed protocols also helps to increase the transparency and reproducibility of the research.

- It’s all in the details: The methods section should meticulously list all the materials, tools, instruments, and software used for different experiments. Specify the testing equipment on which data was obtained, together with its manufacturer’s information, location, city, and state or any other stimuli used to manipulate the variables. Provide specifics on the research process you employed; if it was a standard protocol, cite previous studies that also used the protocol. Include any protocol modifications that were made, as well as any other factors that were taken into account when planning the study or gathering data. Any new or modified techniques should be explained by the authors. Typically, readers evaluate the reliability and validity of the procedures using the cited literature, and a widely accepted checklist helps to support the credibility of the methodology. Note: Authors should include a statement on sample size estimation (if applicable), which is often missed. It enables the reader to determine how many subjects will be required to detect the expected change in the outcome variables within a given confidence interval.

- Write for the audience: While explaining the details in the methods section , authors should be mindful of their target audience, as some of the rationale or assumptions on which specific procedures are based might not always be obvious to the audience, particularly for a general audience. Therefore, when in doubt, the objective of a procedure should be specified either in relation to the research question or to the entire protocol.

- Data interpretation and analysis : Information on data processing, statistical testing, levels of significance, and analysis tools and software should be added. Mention if the recommendations and expertise of an experienced statistician were followed. Also, evaluate and justify the preferred statistical method used in the study and its significance.

What NOT to include in the methods section of a research paper

To address “ how to write the methods section of a research paper ”, authors should not only pay careful attention to what to include but also what not to include in the methods section of a research paper . Here is a list of do not’s when writing the methods section :

- Do not elaborate on specifics of standard methods/procedures: You should refrain from adding unnecessary details of experiments and practices that are well established and cited previously. Instead, simply cite relevant literature or mention if the manufacturer’s protocol was followed.

- Do not add unnecessary details : Do not include minute details of the experimental procedure and materials/instruments used that are not significant for the outcome of the experiment. For example, there is no need to mention the brand name of the water bath used for incubation.

- Do not discuss the results: The methods section is not to discuss the results or refer to the tables and figures; save it for the results and discussion section. Also, focus on the methods selected to conduct the study and avoid diverting to other methods or commenting on their pros or cons.

- Do not make the section bulky : For extensive methods and protocols, provide the essential details and share the rest of the information in the supplemental files. The writing should be clear yet concise to maintain the flow of the section.

We hope that by this point, you understand how crucial it is to write a thoughtful and precise methods section and the ins and outs of how to write the methods section of a research paper . To restate, the entire purpose of the methods section is to enable others to reproduce the results or verify the research. We sincerely hope that this post has cleared up any confusion and given you a fresh perspective on the methods section .

As a parting gift, we’re leaving you with a handy checklist that will help you understand how to write the methods section of a research paper . Feel free to download this checklist and use or share this with those who you think may benefit from it.

References

- Bhattacharya, D. How to write the Methods section of a research paper. Editage Insights, 2018. https://www.editage.com/insights/how-to-write-the-methods-section-of-a-research-paper (2018).

- Kallet, R. H. How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper. Respiratory Care 49, 1229–1232 (2004). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15447808/

- Grindstaff, T. L. & Saliba, S. A. AVOIDING MANUSCRIPT MISTAKES. Int J Sports Phys Ther 7, 518–524 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3474299/

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

Join Us for Peer Review Week 2024

How Editage All Access is Boosting Productivity for Academics in India

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

Table of Contents

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1

What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

What is the introduction for a research paper?

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

Why is the introduction important in a research paper?

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

Check out how Peace Alemede uses Paperpal to write her research paper

Peace Alemede, Student, University of Ilorin

Paperpal has been an excellent and beneficial tool for editing my research work. With the help of Paperpal, I am now able to write and produce results at a much faster rate. For instance, I recently used Paperpal to edit a research article that is currently being considered for publication. The tool allowed me to align the language of my paragraph ideas to a more academic setting, thereby saving me both time and resources. As a result, my work was deemed accurate for use. I highly recommend this tool to anyone in need of efficient and effective research paper editing. Peace Alemede, Student, University of Ilorin, Nigeria

Start Writing for Free

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address.

Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

1. Introduce the research topic:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

2. Determine a research niche:

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

3. Place your research within the research niche:

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

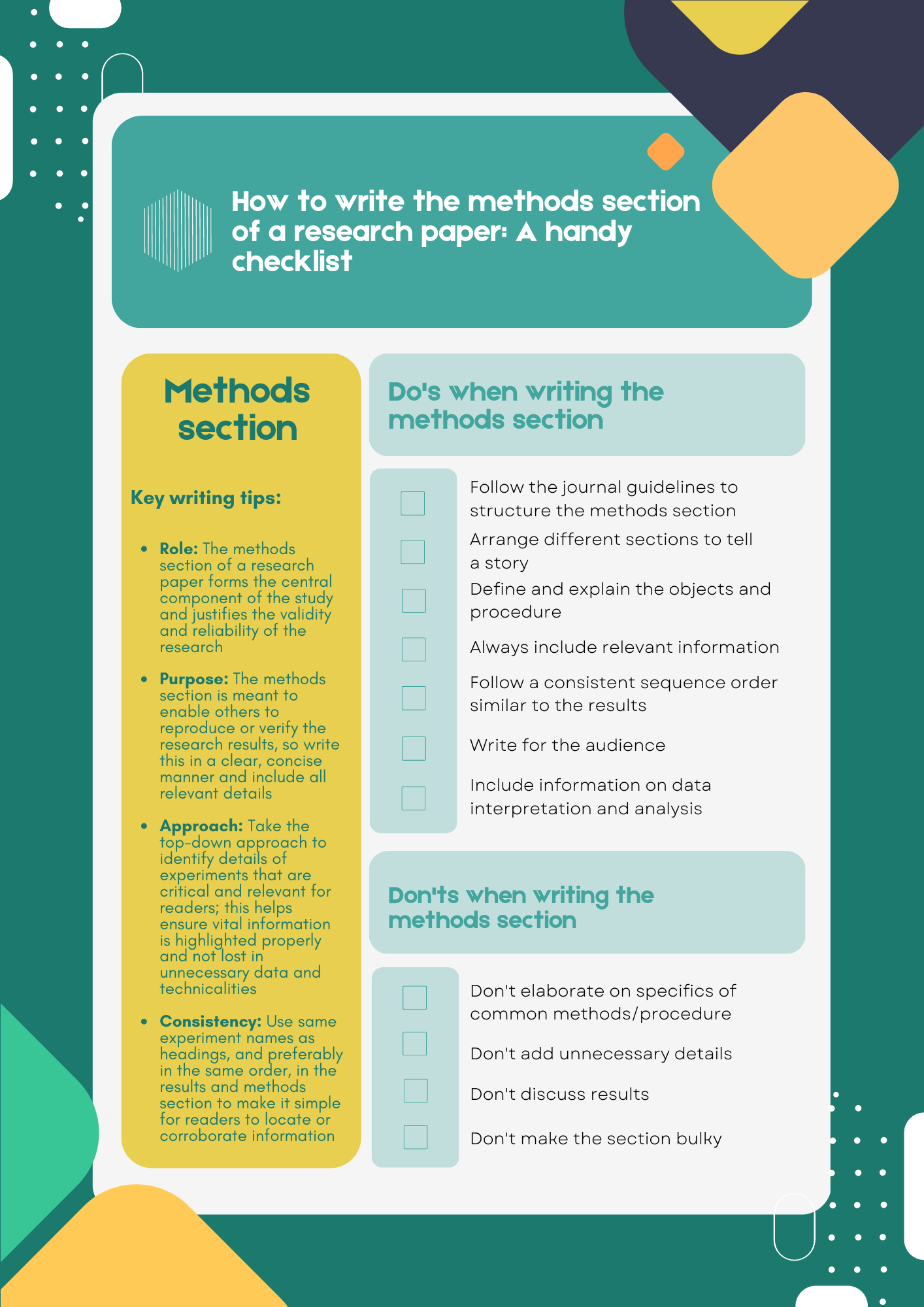

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the purpose of the introduction in research papers.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

How long should the research paper introduction be?

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2

For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

What should be included in the research paper introduction?

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3

Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction.

- Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic.

- Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects.

- Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought.

- Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance.

- Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study

- Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Should I include citations in the introduction for a research paper?

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through.

Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review.

A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

Should I provide a literature review in the research paper introduction?

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following:

- Introduces the topic

- Establishes the study’s significance

- Provides an overview of the relevant literature

- Provides context for the study using literature

- Identifies knowledge gaps

However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction:

- Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research

- Avoid direct quoting

- Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Key points to remember

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

- Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

- Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

- Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

- Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, how to cite in apa format (7th edition):..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples.

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

How to write an effective introduction for your research paper

Last updated

20 January 2024

Reviewed by

However, the introduction is a vital element of your research paper . It helps the reader decide whether your paper is worth their time. As such, it's worth taking your time to get it right.

In this article, we'll tell you everything you need to know about writing an effective introduction for your research paper.

- The importance of an introduction in research papers

The primary purpose of an introduction is to provide an overview of your paper. This lets readers gauge whether they want to continue reading or not. The introduction should provide a meaningful roadmap of your research to help them make this decision. It should let readers know whether the information they're interested in is likely to be found in the pages that follow.

Aside from providing readers with information about the content of your paper, the introduction also sets the tone. It shows readers the style of language they can expect, which can further help them to decide how far to read.

When you take into account both of these roles that an introduction plays, it becomes clear that crafting an engaging introduction is the best way to get your paper read more widely. First impressions count, and the introduction provides that impression to readers.

- The optimum length for a research paper introduction

While there's no magic formula to determine exactly how long a research paper introduction should be, there are a few guidelines. Some variables that impact the ideal introduction length include:

Field of study

Complexity of the topic

Specific requirements of the course or publication

A commonly recommended length of a research paper introduction is around 10% of the total paper’s length. So, a ten-page paper has a one-page introduction. If the topic is complex, it may require more background to craft a compelling intro. Humanities papers tend to have longer introductions than those of the hard sciences.

The best way to craft an introduction of the right length is to focus on clarity and conciseness. Tell the reader only what is necessary to set up your research. An introduction edited down with this goal in mind should end up at an acceptable length.

- Evaluating successful research paper introductions

A good way to gauge how to create a great introduction is by looking at examples from across your field. The most influential and well-regarded papers should provide some insights into what makes a good introduction.

Dissecting examples: what works and why

We can make some general assumptions by looking at common elements of a good introduction, regardless of the field of research.

A common structure is to start with a broad context, and then narrow that down to specific research questions or hypotheses. This creates a funnel that establishes the scope and relevance.

The most effective introductions are careful about the assumptions they make regarding reader knowledge. By clearly defining key terms and concepts instead of assuming the reader is familiar with them, these introductions set a more solid foundation for understanding.

To pull in the reader and make that all-important good first impression, excellent research paper introductions will often incorporate a compelling narrative or some striking fact that grabs the reader's attention.

Finally, good introductions provide clear citations from past research to back up the claims they're making. In the case of argumentative papers or essays (those that take a stance on a topic or issue), a strong thesis statement compels the reader to continue reading.

Common pitfalls to avoid in research paper introductions

You can also learn what not to do by looking at other research papers. Many authors have made mistakes you can learn from.

We've talked about the need to be clear and concise. Many introductions fail at this; they're verbose, vague, or otherwise fail to convey the research problem or hypothesis efficiently. This often comes in the form of an overemphasis on background information, which obscures the main research focus.

Ensure your introduction provides the proper emphasis and excitement around your research and its significance. Otherwise, fewer people will want to read more about it.

- Crafting a compelling introduction for a research paper

Let’s take a look at the steps required to craft an introduction that pulls readers in and compels them to learn more about your research.

Step 1: Capturing interest and setting the scene

To capture the reader's interest immediately, begin your introduction with a compelling question, a surprising fact, a provocative quote, or some other mechanism that will hook readers and pull them further into the paper.

As they continue reading, the introduction should contextualize your research within the current field, showing readers its relevance and importance. Clarify any essential terms that will help them better understand what you're saying. This keeps the fundamentals of your research accessible to all readers from all backgrounds.

Step 2: Building a solid foundation with background information

Including background information in your introduction serves two major purposes:

It helps to clarify the topic for the reader

It establishes the depth of your research

The approach you take when conveying this information depends on the type of paper.

For argumentative papers, you'll want to develop engaging background narratives. These should provide context for the argument you'll be presenting.

For empirical papers, highlighting past research is the key. Often, there will be some questions that weren't answered in those past papers. If your paper is focused on those areas, those papers make ideal candidates for you to discuss and critique in your introduction.

Step 3: Pinpointing the research challenge

To capture the attention of the reader, you need to explain what research challenges you'll be discussing.

For argumentative papers, this involves articulating why the argument you'll be making is important. What is its relevance to current discussions or problems? What is the potential impact of people accepting or rejecting your argument?

For empirical papers, explain how your research is addressing a gap in existing knowledge. What new insights or contributions will your research bring to your field?

Step 4: Clarifying your research aims and objectives

We mentioned earlier that the introduction to a research paper can serve as a roadmap for what's within. We've also frequently discussed the need for clarity. This step addresses both of these.

When writing an argumentative paper, craft a thesis statement with impact. Clearly articulate what your position is and the main points you intend to present. This will map out for the reader exactly what they'll get from reading the rest.

For empirical papers, focus on formulating precise research questions and hypotheses. Directly link them to the gaps or issues you've identified in existing research to show the reader the precise direction your research paper will take.

Step 5: Sketching the blueprint of your study

Continue building a roadmap for your readers by designing a structured outline for the paper. Guide the reader through your research journey, explaining what the different sections will contain and their relationship to one another.

This outline should flow seamlessly as you move from section to section. Creating this outline early can also help guide the creation of the paper itself, resulting in a final product that's better organized. In doing so, you'll craft a paper where each section flows intuitively from the next.

Step 6: Integrating your research question

To avoid letting your research question get lost in background information or clarifications, craft your introduction in such a way that the research question resonates throughout. The research question should clearly address a gap in existing knowledge or offer a new perspective on an existing problem.

Tell users your research question explicitly but also remember to frequently come back to it. When providing context or clarification, point out how it relates to the research question. This keeps your focus where it needs to be and prevents the topic of the paper from becoming under-emphasized.

Step 7: Establishing the scope and limitations

So far, we've talked mostly about what's in the paper and how to convey that information to readers. The opposite is also important. Information that's outside the scope of your paper should be made clear to the reader in the introduction so their expectations for what is to follow are set appropriately.

Similarly, be honest and upfront about the limitations of the study. Any constraints in methodology, data, or how far your findings can be generalized should be fully communicated in the introduction.

Step 8: Concluding the introduction with a promise

The final few lines of the introduction are your last chance to convince people to continue reading the rest of the paper. Here is where you should make it very clear what benefit they'll get from doing so. What topics will be covered? What questions will be answered? Make it clear what they will get for continuing.

By providing a quick recap of the key points contained in the introduction in its final lines and properly setting the stage for what follows in the rest of the paper, you refocus the reader's attention on the topic of your research and guide them to read more.

- Research paper introduction best practices

Following the steps above will give you a compelling introduction that hits on all the key points an introduction should have. Some more tips and tricks can make an introduction even more polished.

As you follow the steps above, keep the following tips in mind.

Set the right tone and style

Like every piece of writing, a research paper should be written for the audience. That is to say, it should match the tone and style that your academic discipline and target audience expect. This is typically a formal and academic tone, though the degree of formality varies by field.

Kno w the audience

The perfect introduction balances clarity with conciseness. The amount of clarification required for a given topic depends greatly on the target audience. Knowing who will be reading your paper will guide you in determining how much background information is required.

Adopt the CARS (create a research space) model

The CARS model is a helpful tool for structuring introductions. This structure has three parts. The beginning of the introduction establishes the general research area. Next, relevant literature is reviewed and critiqued. The final section outlines the purpose of your study as it relates to the previous parts.

Master the art of funneling

The CARS method is one example of a well-funneled introduction. These start broadly and then slowly narrow down to your specific research problem. It provides a nice narrative flow that provides the right information at the right time. If you stray from the CARS model, try to retain this same type of funneling.

Incorporate narrative element

People read research papers largely to be informed. But to inform the reader, you have to hold their attention. A narrative style, particularly in the introduction, is a great way to do that. This can be a compelling story, an intriguing question, or a description of a real-world problem.

Write the introduction last

By writing the introduction after the rest of the paper, you'll have a better idea of what your research entails and how the paper is structured. This prevents the common problem of writing something in the introduction and then forgetting to include it in the paper. It also means anything particularly exciting in the paper isn’t neglected in the intro.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: Sep 17, 2024 10:59 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Get creative with full-sentence rewrites

Polish your papers with one click, avoid unintentional plagiarism.

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction in 4 Steps

Published on July 2, 2024 by Hannah Skaggs . Revised on September 11, 2024.

Having a hard time learning how to write a research paper introduction? Follow these four steps:

- Draw readers in.

- Zoom in on your topic and its importance.

- Explain how you’ll add new knowledge.

- Tell readers what they’ll find in your paper.

To understand why a great introduction matters, imagine a friend inviting you to lunch with another friend of hers. You show up at the restaurant and find them waiting for you at the table. You sit down, and her friend says, “So I wanna tell you about my major goal in life.”

Pretty awkward, right? You don’t even know this guy’s name yet, and he’s already diving into the heavy stuff. You’d probably prefer to have your friend introduce him, then spend some time learning about his background and personality before you get into deeper conversation.

Research paper readers need this kind of warmup, too. A good introduction, or intro, lives up to its name—it introduces readers to the topic. It prepares them to care about and understand your research, and it’s more convincing.

Free Grammar Checker

Table of contents

Steps to write a research paper introduction, tips for writing a research paper introduction, tools for writing a research paper introduction, frequently asked questions about how to write a research paper.

By following the steps below, you can learn how to write an introduction for a research paper that helps readers “shake hands” with your topic. In each step, thinking about the answers to key questions can help you reach your readers.

1. Get your readers’ attention

To speak to your readers effectively, you need to know who they are. Consider who is likely to read the paper and the extent of their knowledge on the topic. Then begin your introduction with a sentence or two that will capture their interest.

For instance, you might begin with an interesting quote or an example of a situation that illustrates your argument (as we did above). Or you could start by simply stating a fact that most people aren’t aware of, which may be a better approach in scientific fields. Whichever method you choose, remember that this is academic writing —keep your phrasing formal and don’t sensationalize.

Key questions:

- Who is your audience?

- What will your paper talk about?

- What will grab your audience’s interest in the topic?

2. Explain why your topic matters

Just as you’d like to understand where a new acquaintance is coming from as you get to know them, your readers want to understand the background of your research. Once you’ve got their attention, explain why they should care.

You can give background for your research by discussing previous research on the topic. While this part should be shorter than a literature review , it can explore some of the same kinds of connections and themes. Make sure the sources you cite relate to the argument you’re making or the problem you want to solve. The information you provide here should lay a factual foundation for your research.

- Why should readers care about your topic?

- What do readers need to know to understand your research?

- What have other researchers said about the topic?

- What is the field’s overall view of the topic?

3. Lay out your argument and plan

After showing your reader the existing knowledge on the topic, you can turn to how your paper will contribute new knowledge. Tying your research to previous research is the most important aspect of this step.

Explain what knowledge is missing from the existing research and how you plan to uncover that knowledge. This is the most common place for the thesis statement, which succinctly tells readers the purpose and main idea of your paper (though it could also appear at the end of Step 4).

- How does your research relate to the studies you described in Step 2?

- What question are you aiming to answer , or what problem are you looking to solve?

- What methods will you use to answer that question or solve that problem?

4. Define your direction

Besides introducing your readers to the topic and your related findings or argument, you’re introducing them to your research process and the paper itself. This means you need to help them understand how the paper is organized and where it’s going. Add a sentence, or a few sentences, describing the sections of your paper in order or the main ideas it will cover.

While longer papers typically need to include this step, shorter ones, such as a five-paragraph essay , can usually skip it. In these cases, the thesis statement outlines the paper’s structure.

- What goal will each section of your paper accomplish?

- What should readers take away from your paper?

As you go through the steps above, keep in mind the principles of quality academic writing. Specifically, understanding how to organize and summarize will empower you to complete each step with excellence.

Keep it smooth

A good flow helps readers follow your logic. As you progress from Step 1 to Step 4, the information you give should grow more and more specific. It’s similar to how, when you meet a person, you learn basics like their name and appearance first. Then you learn about their background and more specific details, like their political views.

To make your introduction flow, start with an outline. The outline functions like a skeleton. It provides a structure for the details that make up your introduction like muscles and other tissues. It helps you make sure you don’t miss any important elements. Then, as you flesh out the details, use transition words and phrases between them to show how they relate to each other.

Keep it brief

How long should a research paper introduction be? It depends on the overall length of your paper, but the intro is typically one of the shortest sections. For example, in a short paper like an essay, you can complete each of the steps above in just a sentence or two. But in a longer one, such as a dissertation , each step may take a couple of paragraphs.

In a sense, the intro is a summary of the rest of the paper, and summarizing is all about prioritizing. As business guru Karen Martin said, “When everything is a priority, nothing is a priority.”

Martin was talking about deciding which tasks are more urgent in a business, but the same principle applies to summarizing. You must decide which ideas are the most fundamental and leave the rest out. Think about it: when you’re first meeting someone, they don’t give you an exhaustive list of all their traits. They introduce themselves with just a few of their most prominent ones.

Besides narrowing your focus, another way to keep your introduction short is to write concisely. Plain, direct language helps hold the reader’s attention, but wordy sentences will make them nod off and lose interest.

Since the introduction of a research paper is basically a summary, you may find it helpful to write it last, after you’ve finished the rest of your paper. If you write it first, there’s a good chance you’ll have to change some of its main points later. This can happen because the other sections of your paper, which your intro is based on, may evolve while you’re writing them.

Of course, you should always go back and take a second or even third look at every section of your research paper to check for errors and other necessary changes. But if you write your intro last, editing it is likely to take much less time.

Now that we’ve introduced you to the basics of writing a research paper introduction, we’d like to introduce you to QuillBot. At every step of writing your intro, it can help you upgrade your writing skills:

- Cite sources using the Citation Generator .

- Avoid plagiarism using the Plagiarism Checker .

- Reword statements from previous research (but still cite them) using the Paraphraser .

- Write spectacular and concise thesis statements (or even your whole introduction section!) using the Summarizer .

A research paper introduction starts by acquainting readers with the topic generally. Then it explores the background of the research. Finally, it explains the specific purpose of the research and its contribution.

Quotes , anecdotes, and interesting facts are all effective hooks to begin the introduction of a research paper. Which one you choose depends on the subject of your paper and your field of study.

Is this article helpful?

Hannah Skaggs

Research Blog

How to write a research paper introduction (with examples).