Evaluating and Pricing Health Insurance in Lower-income Countries: A Field Experiment in India

Universal health coverage is a widely shared goal across lower-income countries. We conducted a large-scale, 4-year trial that randomized premiums and subsidies for India’s first national, public hospital insurance program, called RSBY. We find substantial demand (∼ 60% uptake) even when consumers were charged a price equal to the premium the government paid for insurance. We also find substantial adverse selection into insurance at positive prices. Insurance enrollment increases insurance utilization, partly due to spillovers from use of insurance by neighbors. However, healthcare utilization does not rise substantially, suggesting the primary benefit of insurance is financial. Many enrollees attempted to use insurance but failed, suggesting that learning is critical to the success of public insurance. We find very few statistically significant impacts of insurance access or enrollment on health. Because there is substantial willingness-to- pay for insurance, and given how distortionary it is to raise revenue in the Indian context, we calculate that our sample population should be charged a premium for RSBY between 67-95% of average costs (INR 528-1052, $30-60) rather than a zero premium to maximize the marginal value of public funds.

We thank Kate Baicker, Amitabh Chandra, Manasi Deshpande, Pascaline Dupas, Jacob Goldin, Joshua Gottlieb, Johannes Haushofer, Nathaniel Hendren, Rick Hornbeck, Radhika Jain, Neale Mahoney, Karthik Muralidharan, Joe Newhouse, Matt Notowodigdo, Julian Reif, and seminar participants at Brown University, Columbia University, University of Chicago, HBS, the Indian School of Public Policy, PUC-Rio, Stanford, Wharton, ASSA, Barcelona Summer School, BREAD, IFS-UCL-LSE-STICERD Development seminar, and LEAP for comments. For exceptional research assistance, we thank Tanay Balantrapu, Afia Khan, Sneha Stephen, Tianyu Zheng, and the JPAL-SA and Outline India field teams. This study was funded by the Department for International Development in the UK Government; the Tata Trusts through the Tata Centre for Development at the University of Chicago; the MacLean Center, the Becker-Friedman Institute, the Neubauer Collegium, and the Law School at the University of Chicago; the Sloan Foundation; SRM University; Northwestern University and the International Growth Centre. The study received IRB approval from U. of Chicago (IRB12-2085), Northwestern (STU00073184), the Public Health Foundation of India (TRCIEC- 182/13), and the Institute for Financial Management and Research. This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03144076) and the American Economic Association Registry (AEARCTR-0001793). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

- randomized controlled trials registry entry

- online appendix

- March 15, 2024

Working Groups

More from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

Effect of Health Insurance in India: A Randomized Controlled Trial

University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2021-146

52 Pages Posted: 27 Dec 2021

Anup Malani

University of Chicago - Law School; National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine; Resources for the Future

Phoebe Holtzman

Jones Lang LaSalle

Kosuke Imai

Harvard University

Cynthia Kinnan

Northwestern University - Department of Economics

Morgen Miller

University of Chicago

Shailender Swaminathan

University of Alabama at Birmingham - School of Public Health

Alessandra Voena

Stanford University

Bartosz Woda

University of Chicago - Law School

Gabriella Conti

University College London

Date Written: December 17, 2021

We report on a large randomized controlled trial of hospital insurance for above poverty-line Indian households. Households were assigned to free insurance, sale of insurance, sale plus cash transfer, or control. To estimate spillovers, the fraction of households offered insurance varied across villages. The opportunity to purchase insurance led to 59.91% uptake and access to free insurance to 78.71% uptake. Access increased insurance utilization. Positive spillover effects on utilization suggest learning from peers. Many beneficiaries were unable to use insurance, demonstrating hurdles to expanding access via insurance. Across a range of health measures, we estimate no significant impacts on health.

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Anup Malani (Contact Author)

University of chicago - law school ( email ).

1111 E. 60th St. Chicago, IL 60637 United States 773-702-9602 (Phone) 773-702-0730 (Fax)

HOME PAGE: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/faculty/malani/

National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)

1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 United States

University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine

Chicago, IL 60637 United States

Resources for the Future

1616 P Street, NW Washington, DC 20036 United States

Jones Lang LaSalle ( email )

330 Madison Ave 4th floor New York, NY 10017

Harvard University ( email )

1875 Cambridge Street Cambridge, MA 02138 United States

Northwestern University - Department of Economics ( email )

2003 Sheridan Road Evanston, IL 60208 United States

University of Chicago ( email )

1101 East 58th Street Chicago, IL 60637 United States

University of Alabama at Birmingham - School of Public Health ( email )

1665 University Blvd. Birmingham, AL 35294 United States

Stanford University ( email )

Stanford, CA 94305 United States

1111 E. 60th St. Chicago, IL 60637 United States

University College London ( email )

Gower Street London, WC1E 6BT United Kingdom

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, becker friedman institute for economics working paper series.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Randomized Social Experiments eJournal

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Impact of Publicly Financed Health Insurance Schemes on Healthcare Utilization and Financial Risk Protection in India: A Systematic Review

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Public Health, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

Affiliation Indian Institute of Public Health, Delhi, Public Health Foundation of India, Delhi NCR, India

- Shankar Prinja,

- Akashdeep Singh Chauhan,

- Anup Karan,

- Gunjeet Kaur,

- Rajesh Kumar

- Published: February 2, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996

- Reader Comments

Several publicly financed health insurance schemes have been launched in India with the aim of providing universalizing health coverage (UHC). In this paper, we report the impact of publicly financed health insurance schemes on health service utilization, out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure, financial risk protection and health status. Empirical research studies focussing on the impact or evaluation of publicly financed health insurance schemes in India were searched on PubMed, Google scholar, Ovid, Scopus, Embase and relevant websites. The studies were selected based on two stage screening PRISMA guidelines in which two researchers independently assessed the suitability and quality of the studies. The studies included in the review were divided into two groups i.e., with and without a comparison group. To assess the impact on utilization, OOP expenditure and health indicators, only the studies with a comparison group were reviewed. Out of 1265 articles screened after initial search, 43 studies were found eligible and reviewed in full text, finally yielding 14 studies which had a comparator group in their evaluation design. All the studies (n-7) focussing on utilization showed a positive effect in terms of increase in the consumption of health services with introduction of health insurance. About 70% studies (n-5) studies with a strong design and assessing financial risk protection showed no impact in reduction of OOP expenditures, while remaining 30% of evaluations (n-2), which particularly evaluated state sponsored health insurance schemes, reported a decline in OOP expenditure among the enrolled households. One study which evaluated impact on health outcome showed reduction in mortality among enrolled as compared to non-enrolled households, from conditions covered by the insurance scheme. While utilization of healthcare did improve among those enrolled in the scheme, there is no clear evidence yet to suggest that these have resulted in reduced OOP expenditures or higher financial risk protection.

Citation: Prinja S, Chauhan AS, Karan A, Kaur G, Kumar R (2017) Impact of Publicly Financed Health Insurance Schemes on Healthcare Utilization and Financial Risk Protection in India: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 12(2): e0170996. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996

Editor: Cheng-Yi Xia, Tianjin University of Technology, CHINA

Received: June 30, 2016; Accepted: January 13, 2017; Published: February 2, 2017

Copyright: © 2017 Prinja et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding: This research was supported by USAID India grant AID-386-A-14-00006. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is a major policy goal in health sector globally. [ 1 , 2 ] Despite the acceptance of UHC at policy level in India, around three-quarters of healthcare spending is borne by households. [ 3 ] The recent National Sample Survey (NSS) report reveals that only 12% of the urban and 13% of the rural population is under any kind of health protection coverage. [ 4 ] Not surprisingly, nearly 26% of the total health spending by rural households is sourced from either borrowings or selling of assets. [ 4 ] Further, OOP spending pushes approximately 3.5% to 6.2% of the India’s population below the poverty line every year. [ 5 – 7 ]

Traditionally, health care financing in India had been mostly restricted to the supply side, focussing on the strengthening of infrastructure and human resource. The advent of National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in 2005 also served as an instrument of strengthening the supply-side infrastructure. [ 8 ] The Planning Commission’s High Level Expert Group (HLEG) proposed a model to achieve UHC under which citizens would have full access to free healthcare from a combination of public and private facilities. [ 9 ] This shifted government’s attention from its prior focus on supply side to demand side financing models in the form of publicly sponsored health insurance schemes.

Since 2007, several publicly financed health insurance schemes have been launched in India both at the state level such as Rajiv Aarogyasri Health Insurance Scheme (RAS) in Andhra Pradesh [ 10 ], Rajiv Gandhi Jeevandayee Arogya Yojana (RGJAY) in Maharashtra [ 11 ], Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance scheme (CMCHIS) in Tamil Nadu [ 12 ], and Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) at the Central level. [ 13 ] These demand-side financing mechanisms entitle poor and other vulnerable households to choose cashless healthcare from a pool of empanelled private or public providers. While the RSBY scheme was designed and implemented by the Ministry of Labour and Employment (MOLE), the implementation role for RSBY–now called Rashtriya Swasthya Suraksha Yojana (RSSY, however we refer to as RSBY in the entire paper), has been recently transferred to Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in 2015. [ 14 ]

In the last 7–8 years, a large amount of government’s money has been invested in the implementation of these health insurance schemes. A total of INR 370 billion (USD 587 million) tax money has been allocated for RSBY since its launch in 2008–09. [ 15 ] If the budgets of state sponsored schemes are also pooled, it amounts to a significant amount of public exchequer’s money, thereby justifying a need to determine whether these schemes are achieving their desired objectives.

In line with this policy need for an appraisal, the Government of India constituted a task force on costing of health services. One of the terms of reference for this Task Force included an assessment of RSBY. [ 16 ] Also, several State Governments have set up independent commissions to determine the best way forward to achieve universal health coverage. [ 17 , 18 ] As a result, there is a need to systematically review evidence in terms of whether these schemes have been able to achieve the objectives of universalizing health care for which they were launched. Two reviews have been published earlier, both of which measured the impact of health insurance in low and middle income countries as a whole without a specific focus on India. [ 19 , 20 ] Specific characteristics of the scheme implementation and contextual differences in various countries support a case for a systematic review with a national focus. Further, one of these review focussed on only social and community based health insurance schemes. [ 20 ] However, much of the current interest is on determining success or failure of tax-funded health insurance schemes which cover nearly 14% out of the total 15% population who have any form of health care insurance.

As a result, we conducted a systematic review to primarily assess the impact of publicly financed health insurance schemes on utilization of health care services, out of pocket expenditure, financial risk protection and on the health of population in India. Secondly, we also summarise the findings of various process evaluations, which have assessed the performance of these schemes in terms of extent of community awareness, determinants of enrolment and utilization, accessibility and utilization of different services across states in India.

Methodology

Search strategy.

A comprehensive computerised search was conducted to search for empirical studies focussing on the impact or evaluation of publicly sponsored health insurance schemes in India. PubMed, Google scholar, Ovid, Scopus and Embase databases were searched to identify eligible studies published till September 2015. Official websites of various health insurance schemes ( www.rsby.gov.in , www.aarogyasri.telangana.gov.in , www.sast.gov.in/home/VAS.html , http://www.cmchistn.com and / www.chiak.org ) were also searched. The review used the search strategy consisting of following key words:

(((((((((((Publicly sponsored health insurance) OR government sponsored health insurance) OR Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana) OR RSBY) OR rajiv arogyasree health insurance scheme) OR rajiv aarogyasri community health insurance scheme) OR vajpayee arogyasri) OR vajpayee arogyasri yojana) OR chief minister kalaignar insurance scheme) OR rajiv gandhi jeevandayee arogya yojana) OR comprehensive health insurance scheme)”.

The search strategy was defined by reviewing the previously done systematic reviews and in consultation with the research staff from the Advanced Centre for Evidence-Based Child Health and the library staff of the Post-Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh. The key words were checked for controlled vocabulary under Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) of PubMed. Two investigators (ASC and GK) had access to abstract and full text of the paper to decide on its inclusion. Discrepancies between the two investigators were solved by discussion with the third investigator (SP). Two authors of this review are familiar with the methods of systematic review (SP and AK), two are experts in health economics with strong interest and familiarity with the health financing policies (SP and AK), while another author is a senior public health expert (RK).

Inclusion criteria and study selection

The review included peer-reviewed articles, government reports and working papers that were reported in the English language and excludes abstracts, expert opinions, narrative reviews, commentaries, case reports and conference papers.

The studies were selected based on a two stage screening process as per PRISMA guidelines [ 21 ] ( S1 Table ). The first step comprised of searching for studies based on the search strategy from the selected databases and websites. Following this, duplicates were removed and the remaining studies were then screened by applying inclusion criteria to the titles and abstracts. Based on the screening of titles and abstracts, potentially relevant articles were selected for further review, which involved examining the content of their full text. After reviewing full text, only empirical research studies were considered eligible while others were excluded. At this stage, a bibliographic search of the selected studies was also carried out to identify additional relevant articles. The search was continued until no new article was found ( Fig 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.g001

Data extraction and quality

A standardised data extraction form was developed to collect information from the selected studies on the relevant impact outcomes, besides the general and methodological aspects. The latter included information on year of publication, funding agency, study design or type of study (experimental and observational), description of intervention and control group, duration and location of the study, sample size, type of outcome assessed, etc. Two researchers (ASC and GK) independently extracted the data and assessed the quality of the studies.

The studies selected in the review were divided into two groups i.e., with a comparison or control group (against which the insured group was measured) and without a control group (descriptive in nature). To assess the impact on utilization, OOP expenditure and health indicators, studies with a comparison group alone were reviewed. Process level indicators were assessed based on the findings of studies from both the groups, i.e. with and without control group. Further, quality of these studies was assessed by Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. [ 22 ] The components of quality assessment in the EPHPP tool include type of study, presence of any kind of selection bias, consideration to blinding and confounders, validity and reliability of the data collection tools and consideration to withdrawals and loss to follow ups, if any. We also categorised the studies (having a control group) based on their analytical approach–i.e. Intention to Treat (ITT) and Average Treatment effect on the Treated (ATT) analysis. [ 23 ] Basically, ITT measures impact on the eligible population irrespective of getting enrolled or utilising the services while ATT measures impact on those who are enrolled in the scheme.

A total of 1265 articles were identified from databases (n = 1244), websites (n = 18) and bibliographic search (n = 3) as shown in Fig 1 . After removing duplicates, the remaining 814 articles were screened by applying inclusion criteria to the titles and abstracts. A total of 671 articles were excluded in the 1 st stage screening and 143 studies were identified as eligible for 2 nd screening. Full text papers of these 143 studies were reviewed. Ultimately, 43 articles were found eligible for this systematic review. Out of this, 14 studies had a comparison group [ 24 – 37 ] and the remaining 29 were without a comparison group [ 38 – 66 ].

General characteristics of selected studies

Out of the 14 studies with a comparison group, 7 were cross-sectional studies with data collected from intervention and control group, while 6 studies were quasi experimental in nature adopting a pre and post design. Out of these 6 studies, 2 studies evaluated the impact based on difference in difference analysis and one study followed geographic discontinuity design ( Table 1 ). Most of these studies (n = 8) were published in peer reviewed journals while the remaining were reports (n = 3) and working papers (n = 3). Around half of the studies (n = 6) evaluated RSBY scheme, followed by studies on RAS (n = 3), Vajpayee Aarogyashri Scheme (VAS) (n = 1) and Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme in Kerala (n = 1). Further, focus of the remaining 3 studies was on both RSBY and RAS. Twelve studies evaluated the health insurance scheme within 3 years of their implementation while the remaining 2 studies evaluated the scheme following 3 years of implementation.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.t001

With regards to studies without a comparison group (n = 29), majority of them (59%, n = 17) were published in peer reviewed journals, 28% (n = 8) were working papers and the remaining were reports (13%) ( Table 1 ). All the studies had a cross sectional study design, out of which 8 studies were based on secondary data and 4 had a regression model based analysis. Nearly 83% (n = 24) of the studies evaluated RSBY, followed by 10% studies (n = 3) on RAS. More than half (56%, n = 16) of these studies were done within 3 years of the implementation of the scheme, followed by 31% (n = 9), assessing the scheme following 3 years of implementation. For the rest, 13% of the studies duration between implementation of the scheme and evaluation of the study was not clearly stated in the article.

Impact assessment

Table 2 summarises the impact of various publicly financed health insurance schemes reported in the selected 14 studies with a comparison group. Nine of these studies were based on ATT analysis approach [ 26 – 29 , 31 , 34 – 37 ], while remaining 5 studies were ITT in nature. [ 24 , 25 , 30 , 32 , 33 ]

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.t002

Among these, 7 studies (50%) assessed financial risk protection only, one study measured utilization alone, while remaining 5 studies (36%) evaluated both utilization and financial risk protection. Only one study included all the impact outcomes including the impact of insurance on the health of the population.

Financial risk protection.

Out of the 13 studies assessing financial risk protection [ 24 – 36 ], 9 (69%) reported no reduction in OOP expenditure among enrolled households after implementation of health insurance schemes. [ 24 – 27 , 30 – 32 , 34 , 35 ] In terms of quality, 7 studies had a strong methodological design [ 24 , 30 – 33 , 35 , 36 ], out of which 5 reported increase in the OOP expenses. [ 24 , 30 – 32 , 35 ] The remaining 2 studies, which evaluated state sponsored insurance schemes of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, showed a decline in OOP expenses. [ 33 , 36 ] Out of the five strong quality studies showing increase in OOP expenditure, 3 studies were based on the same data and methodology but had measured varied outcomes in terms of financial protection. [ 24 , 30 , 32 ] Specifically, among studies measuring catastrophic health expenditure as a measure of financial protection, 3/4 th showed increase in the incidence of catastrophic health count. [ 24 – 26 ] Only a single high quality study, which evaluated Andhra Pradesh’s RAS scheme showed a reduction in incidence catastrophic head count after implementation of the scheme. [ 33 ]

The studies (n = 5) which measured the impact of RSBY only, were either of a low or moderate quality and among these, 2 studies reported a reduction in OOP expenses [ 28 , 29 ], but none showed any decrease in incidence of catastrophic health expenditure. Among the 4 studies which evaluated state sponsored schemes [ 33 – 36 ], 2 reported reduction in OOP expenses [ 33 , 36 ], and one study showed decrease in number of catastrophic head count [ 33 ]. One study which considered all the publicly sponsored health insurance schemes together as one, reported that all these were associated with rise in OOP expenditure and catastrophic health expenditure. [ 25 ]

Three studies, which were based on similar data and methodology, compared the impact of RAS in Andhra Pradesh with that of RSBY in Maharashtra. [ 24 , 30 , 32 ] One of these studies showed that in both the states, schemes were associated with increase in OOP expenditure and catastrophic health expenditure, with higher increase in the state of Maharashtra. [ 24 ] Other study showed that this increase in expenditure was observed among both the household groups who accessed care in public or private health facilities. [ 32 ] The latter finding implied some protective effect of RAS in Andhra Pradesh, relative to RSBY in Maharashtra. However, independently, RAS did not result in a reduction in OOP expenses among insured. Another study inferred that this relative reduction in OOP expenditure and catastrophic health expenditure in Andhra Pradesh (compared to Maharashtra) was concentrated more among the richest 60%, implying an inequitable effect. [ 30 ]

Among 7 studies with a quasi-experimental design, 5 showed that the insurance schemes were associated with a rise in OOP expenditure. [ 24 , 30 – 32 , 35 ] Similarly, among the 3 studies based on DID analysis, 2 reported showed rise in OOP expenditure. [ 24 , 25 ] Among 6 cross sectional studies, a study reported similar [ 27 ] amount of OOP expenditures among enrolled and non-enrolled group and 2 studies reported reduction in incurring of OOP expenses. [ 28 , 29 ]

Out of the 7 studies with a strong methodological design, 4 were done within 3 years of the implementation of the schemes, of which 2 studies reported reduction in OOP expenditure [ 33 , 36 ] and a study showed reduction in catastrophic health expenditure. [ 33 ] Studies done at and after 3 year of implementation showed, that schemes were associated with increase in OOP expenses and number of catastrophic head count. [ 24 , 28 , 30 , 32 ]

Utilization.

Overall 7 articles assessed the impact of health insurance on utilization of health services and the findings of all these studies showed that these insurance schemes were associated with increase in consumption of health care services. In terms of quality, 5 studies were of strong methodological rigour [ 24 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 36 ] and the remaining 2 had a moderate or weak quality. [ 26 , 37 ] The increase in utilization among these studies varied from 12.3% to 244% among the insured as compared to non-insured households. The studies based on ATT analysis showed that this increase was in in the range of 12.3%-244%, [ 26 , 35 – 37 ] whereas studies based on ITT analysis showed the increase in the range of 22%-56% among the enrolled households. [ 24 ]

Among the studies which evaluated RSBY alone (n = 2), increase in utilization varied from 15.3% in Maharashtra [ 37 ] to 244% in Karnataka. [ 26 ] For the state-specific insurance schemes, increase in consumption of health care varied from 12.3% in Karnataka’s VAS [ 36 ] to 35.4% for Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme of Kerala. [ 35 ]

One out of the 3 studies which were based on same data and methodology, comparing the impact of RAS in Andhra Pradesh with that of RSBY in Maharashtra, showed an increase in utilization in post insurance period in both states with higher increase in the state of Andhra Pradesh. [ 24 ] Another study showed that this significant positive growth in the utilization was more among both the poor and better-off households in Andhra Pradesh as compared to Maharashtra. Further, it also showed that the increase in utilization of simpler conditions such as fever was more among poor while the rich reported more consumption of services required for the management of chronic conditions such as kidney problems. [ 30 ] The third study showed that in the post insurance period utilization of services in private hospitals increased in Andhra Pradesh and decreased in Maharashtra. On the other hand, utilization in public facilities reduced in both the states with more decrease seen in the state of Andhra Pradesh. [ 32 ]

Increase in the utilization rate in early years of implementation was much higher (12.3% to 244%) [ 26 , 35 , 36 ], than the increase in utilization reported (15%) when the scheme was evaluated after 5 years of its implementation. [ 37 ]

Impact on health.

A single study assessed the impact of health insurance on the improvement of health among those enrolled in the scheme. It reported that the mortality rate from conditions covered by the scheme was less in eligible households as compared to ineligible households (0.32% vs 0.90%). [ 36 ] While about half (52%) of deaths among enrolled households were among people aged <60 years, this rose to more than three-fourths (76%) among those not enrolled. The study also showed that impact of the scheme in reducing mortality was more pronounced among poor in the treatment areas and not among population above poverty line.

Process evaluation

Out of the 29 studies without a control group, 77% of them (n = 24) were on RSBY only and the remaining studies either assessed state sponsored health insurance scheme only or compared it with RSBY. The process indicators included in these studies were level of awareness, determinants of enrolment and utilisation and accessibility to hospitals.

Eight studies done across states in India measured the awareness level of various attributes related to the health insurances schemes. [ 26 , 29 , 38 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 53 , 63 ] Further, 10 studies also assessed the source of awareness about these schemes across various states in India. [ 26 , 29 , 38 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 53 , 57 , 63 , 66 ] Furthermore, 6 studies evaluated the role of determinants for enrolment. [ 37 , 42 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 50 ] Similarly, 8 studies measured the association of factors influencing utilization of health services, among the enrolled households. [ 24 , 33 , 37 , 40 , 47 – 49 , 51 ]

Awareness levels of various attributes related the insurance schemes were reported to be in the range of 13.6% to 90% as shown in Table 3 . Awareness was highest for information on BPL status and 5 member per household as the eligibility criteria and relatively lowest for transport allowances and diseases/conditions covered under the insurance schemes. Specifically, information on eligibility condition of 5 members per household varied from 31% in Chhattisgarh to around 63% in Haryana. Further, awareness level ranged from 32% in Gujarat to 65% in Himachal Pradesh regarding information on free treatment being given under the scheme. Similarly regarding knowledge of transport allowance, information levels ranged from 13.6% in Haryana to 43% in Uttar Pradesh. Panchayats (median: 61%) and friends/ neighbours (median: 44.5%) were the most common source of awareness. In around 60% and 43% of the reported studies, panchayat and friends/neighbour respectively were stated as the source of awareness in more than 60% of the studied population. Less than 15% of the population stated the contribution of health care workers for awareness generation ( Table 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.t004

Determinants of enrolment.

The studies selected in the review showed that enrolment was inversely associated with administrative areas having a larger geographic size [ 42 , 49 ] and families belonging to socially disadvantaged communities [ 42 , 46 , 50 ] ( Table 5 ). Further, 2 studies also reported that low enrolment was related to the poverty status of the households. [ 46 , 47 ] On the contrary, higher enrolment was associated with households headed by a female. [ 37 , 46 ] Further, districts with good development indicators in terms of better business index [ 49 ], low corruption index [ 46 ], higher coverage of preventive health services such as DPT immunization [ 50 ] and better accessibility to commercial banks or nearby town [ 50 ] were also positively associated with high enrolment rates. None of the selected studies identified ‘self-selection’ while analysing the determinants of enrolment although one study mentioned that there is less likelihood of self-selection in RSBY as the scheme is open only for poor. [ 50 ]

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.t005

Determinants of utilization.

Higher the number of empanelled hospitals and proportion of private hospitals in a district, higher were the rates of hospitalization [ 47 – 49 , 51 ] ( Table 6 ). Less advantaged castes were associated with lowest utilization rates. [ 24 , 33 , 37 , 40 ] In contrast to trends in enrolment, districts with better indicators of economic development such as access to educational, commercial, hospitals and transportation institutions and better coverage of preventive or primary health services (such as DPT3 immunization rate) were linked with low utilization rates. [ 48 , 49 ] RSBY scheme was mostly utilized for gynaecological procedures (5–20%), urogenital (33.4%), gastrointestinal (11%) and ophthalmic (6%) conditions ( Fig 2 ). On the contrary, state sponsored health insurance schemes catered mainly to tertiary care needs for injuries (21–27%), oncology (6–17%) and cardiovascular/respiratory/nephrology conditions (9–10%). RSBY scheme was used predominantly for medical as compared to surgical procedures.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.t006

Private facilities were observed as the preferred ones by the beneficiaries of both RSBY and state level health insurance schemes. Findings from the states of Gujarat [ 40 ], Uttar Pradesh [ 29 ] and Haryana [ 66 ], showed private facilities to be most commonly utilized (73%, 87% and 67% respectively) under RSBY. Three-quarters of all claims under RSBY in India were reported to have utilized care in private facilities, with Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan reporting 100% of claims from private facilities. [ 51 ] Over time, claims in Chattisgarh increased by 266% (INR 38436 to 140900) in private hospitals, as compared to 204% increase in public facilities (INR 30525 to 92905). [ 45 ] Considering, state sponsored scheme of Andhra Pradesh, number of surgeries performed in private hospitals were 2.85 times higher than in public facilities. [ 60 ]

It could be assumed that large percentage of empanelled private providers is the reason for high utilization of these facilities under RSBY. The states of Haryana, West Bengal and Bihar, where proportion of private empanelled hospitals was around 90%, the proportion of overall claims in these facilities was more than 95% in each of these states. ( Fig 3 ), [ 67 ] Similarly, in Tripura, Himachal Pradesh and Assam where proportion of private facilities was less than 20%, the proportion of claims in these facilities was less than 30%. Districts such as Kanpur Nagar from UP, Dangs from Gujarat and Karnal from Haryana, having more than 90% of total empanelled hospitals as private had highest hospitalisation rate across the state. [ 47 ]

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.g003

Even states with lower private sector empanelment, also continue to show higher share of private sector utilization. Private sector contributed 65% and 25% of the total empanelled facilities in the states of Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, while 100% of the claims were from private sector in these states ( Fig 3 ). Similarly, Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand having 98% of claims from private facilities had 62% and 54% of the total empanelled facilities as private respectively. Kerala and Assam were the outliers, where the despite a proportion of private empanelled hospitals of around 50%, the utilization of these facilities was below 30%.

Uniformity and accessibility of hospitals.

Hospitalisation rates under RSBY scheme fell steadily with distance of home from health facility. [ 40 ] Those who lived more than 30 km had a lower inpatient rates as compared to those who lived within 30 km. Likewise, for Andhra Pradesh’s RAS scheme, as distance from the nearest treatment facility increased, the utilization rates declined. [ 58 ] Density of the empanelled hospitals was significantly and positively correlated with the utilization rate. [ 47 , 48 ]

Historically, the health system in India has had a maternal and child health (MCH) centric approach, both in financing and delivery of health services. [ 68 ] Low public spending on health care shifted the burden of seeking care on households by paying out of pocket expenditures. [ 9 ] This led to either a barrier in accessing health services, or catastrophic outcomes for those who sought care. [ 4 , 5 , 7 ] Further, low capacity of public health system has resulted in rapid development of private health care delivery system, as well as a push towards various demand-side financing mechanisms. [ 69 , 70 ] The recent policy thrust on UHC has shifted attention towards a broader focus on health system to meet all the needed preventive as well as curative health care needs of the population.

It is in this contextual framework that various publicly financed health insurance schemes evolved in India. At a time when the debate of ‘how’ to achieve universal health care is raging wide discussions, our paper attempts at summarizing the existing evidence. Our review is the first comprehensive systematic review which focuses on Indian publicly financed health insurance schemes. We find that there is positive evidence that the utilization of hospital services increased after introduction of these insurance schemes. Moreover, this increase in utilization has sustained over time and across regions. However, commensurate with an increase in utilization of services, so far we do not find substantial evidence on reduction of out-of-pocket expenditures or improvement of financial risk protection. In fact, 5 out of 8 studies actually reported either no impact or an increase in OOP expenditures. Finally, although one study does point to some beneficial effect on health of population, there is dearth of robust evidence on the impact of these schemes on the health of the population.

Although our review finds a general increase in utilization of hospitalization services, there are still several unanswered questions. This increase in utilization of hospitalizations could be attributed to 3 reasons: firstly, it could be a result of a pent-up demand on account of previously present barriers to access. However, this could explain the increase in hospitalization during early years of the implementation of health insurance schemes. Persistence of increased utilization over the last 7–8 years rules out this reason. Secondly, it could be attributed to either genuine reduction of financial barriers to access or a supplier induced demand. Given the available evidence, it is difficult to single out the reason from amongst the latter two. Examination of presence and extent of supplier-induced demand is certainly an important future area of research for health economists, although establishing a causal link is fraught with several methodological issues and problems with data availability. It can also be seen that the positive impact on utilization of services which we find in most existing studies could be an underestimate of the true effect considering low awareness level among the enrolled population. As time passes and awareness level improve, this could lead to further increase in utilization of health services [ 71 – 73 ]. Moreover, our review also shows that this increase in utilization is more concentrated in private sector hospitals. Together these two findings imply that it is not only likely to impose fiscal constraints on the government for sustainability of these schemes, but also expected to divert large amount of tax based public money towards private sector.

A second point of concern which points to inefficiency is the presence of conditions such as gynaecological problems, deliveries, cataract etc. among some of leading conditions for which hospitalizations are done. [ 40 , 49 ] This is a pointer to inefficient allocation of resources since while on one hand the Government is already allocating significant supply-side resources through flagship health programs on strengthening public sector facilities for providing universal access to these conditions [ 74 ]; on other hand these conditions continue to be major sources of utilization in the demand-side financing schemes. Considering that much of this utilization in these demand-side financing schemes happens in the private sector, it is inefficient as it leads to double allocation for meeting the same demand. Moreover, this also points to a possible gaming by providers [ 75 , 76 ], where dual practice could possibly result in siphoning off of public sector demand to private sector for provisioning under these schemes.

Contradicting findings in terms of increase in utilization and lack of significant improvement in financial risk protection needs careful examination. This could be explained based on several possible reasons, Firstly, the height of benefit package under existing schemes such as RSBY is inadequate. With a cover of INR 30,000 per year per household, several high cost illnesses leave the individuals at risk of impoverishment. Secondly, the depth of coverage could possibly be inadequate. RSBY and other state health insurance schemes primarily cover the services requiring hospitalization, while nearly 70% of overall health expenditure is on account of outpatient care which is not covered. [ 77 ] So, even enrolled households continue to pay for outpatient care. Thirdly, there is a possibility that even the private empanelled hospitals are charging the patients who pay the same out-of-pocket. [ 40 ] Finally, and importantly, it is possible that the bulk of private empanelled providers which exist in the urban areas remain elusive to the vast rural population which continues to face geographic barriers to accessing care. [ 78 ] This possibility is also substantiated by the finding that the benefits are mostly gained by the richer quintiles and urban population. In view of limitations of existing evidence, a conclusive statement will require further research which examines these possible explanations. Important policy inferences emerge from the latter point–firstly, that no such demand-side health financing scheme can succeed in providing financial risk protection in the absence of a strong primary health infrastructure. Secondly, this primary health infrastructure needs to be equitably distributed and utilized. Finally, since the rural and disadvantaged areas have not seen the growth of private sector, there is significant merit in the role of investing to strengthen public sector infrastructure.

An important finding from the process evaluation reports is the inequitable nature of the enrolment and utilization. This point towards inefficient targeting towards those who need the services most. Several reasons could be considered to explain this finding. Firstly, insurance companies have an incentive to enrol less than the maximum number of 5 household members, because the premium payment is linked to the number of households enrolled, rather than members. Moreover, villages with higher proportion of BPL population have poorer enrolment. This could be a result of systematic attempt to enrol the better-offs rather than worse offs. Average family size reported in India is 4.8. However studies from the review shows average family size of households under RSBY in the range of 1.46–3.77. [ 27 , 29 , 48 , 50 ]. This points to the need for comparing the characteristics of family member enrolled in RSBY against those who are left out. This would help ascertain whether there is any cream skimming by insurance companies. Secondly, it could be seen that in more backward villages, due to paucity of means, poorer households are not able to get a BPL card. And since the means test to identify a poor household is the BPL card, hence the very poor are unable to enrol in the scheme. [ 42 , 47 ] This in turn could lead to poor targeting under the scheme as most needy and poor are unable to obtain BPL card. Another reason which could contribute to poor enrolment among the poorest could be low level of awareness regarding the means to get an insurance card. This also correlates with the finding of low awareness about publicly sponsored health insurance schemes among the target population. [ 26 , 29 , 38 , 43 , 53 ]

We would like to acknowledge that impact evaluation was the primary objective of the present paper, and as a result we might have missed out on some studies which were purely describing the processes. Secondly, we are also likely to miss qualitative narrative of the implementation of these insurance programs, and which do provide important insights. This also explains our reporting of impact assessment results first, followed by process evaluation. However, it is also important to understand that the process evaluations in literature are not as standardized as the impact evaluations, which makes it difficult to systematically report. Not every process evaluation reported findings on the same set of indicators. This is an important gap in literature and needs to be bridged in future studies.

Given the current policy directions for universal health care, publicly financed health insurance schemes are likely to stay. Hence there is a need to design the schemes and implement safeguards so that the benefits of the risk pooling can be maximized. Firstly, benefits of these demand-side financing mechanisms will be not reaped unless the basic health care infrastructure for delivery of primary health services is strong. This primary health care infrastructure will be necessary to provide basic health services, besides serving as gatekeeping for specialist services. Examples from Thailand, United Kingdom and Mexico substantiate this claim. [ 79 ] Secondly, the public sector needs to be strengthened and incentivized to compete for provision of services. This will generate much needed extra revenue for the public health system, which can in turn be used to strengthen provision of health services. The public sector has demonstrated that it can provide universal access for health care services, which are delivered efficiently and utilized equitably, the only condition being that enough resources are spent. Various interventions for improving access to maternal health care services and institutional delivery in public sector illustrates this point. [ 80 – 82 ] Thirdly, there is a need to invest in systems to monitor and evaluate implementation of health insurance schemes. This is also essential in view of large private sector presence, which has perverse incentives to induce demand; and the intermediary purchaser/ insurer, who has perverse incentive to reduce utilization through cream-skimming. Overall, publicly financed health insurance schemes are not the panacea to achieve UHC in India. Instead, these schemes need to be aligned with proper strengthening of the public sector for provision of comprehensive primary health care. Secondly, presence of health insurance schemes could be used as an opportunity to reform the tenets of the health sector which are beyond the routine regulatory frameworks.

Supporting Information

S1 table. prisma checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170996.s001

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the assistance provided by the Mrs Neelima Chadha from the library of Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER) Chandigarh.

Author Contributions

- Conceptualization: SP RK AK.

- Data curation: ASC GK.

- Formal analysis: ASC SP.

- Funding acquisition: AK SP.

- Methodology: SP RK.

- Validation: RK AK.

- Writing – original draft: ASC SP.

- Writing – review & editing: SP ASC AK GK RK.

- 1. World Health Organization. The world health report: health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. 2010.

- 2. Norheim O, Ottersen T, Berhane F, Chitah B, Cookson R, Daniels N, et al. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage: Final report of the WHO consultative group on equity and universal health coverage: World Health Organization; 2014.

- 3. Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. NCMH: Report of the National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. 2005.

- 4. Government of India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. NSSO 71st Round (January—June 2014): Key Indicators of Social Consumption in India Health. 2015.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 8. Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Rural Health Mission (2005–2012) Mission Document.

- 9. Bang A, Chatterjee M, Dasgupta J, Garg A, Jain Y, Shiv Kumar AK, et al. High level expert group report on universal health coverage for India. New Delhi, Planning Commission of India. 2011.

- 10. Rajiv Aarogyasri Health Insurance Scheme. [Internet]. [cited 2016 17 Feb]. Available from: http://www.aarogyasri.telangana.gov.in/ .

- 11. Rajiv Gandhi Jeevandayee Arogya Yojana [Internet]. [cited 2016 17 Feb]. Available from: https://www.jeevandayee.gov.in/ .

- 12. Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance scheme [Internet]. [cited 2016 17 Feb]. Available from: http://www.cmchistn.com/ .

- 13. Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana [cited 2015 20 November]. Available from: http://www.rsby.gov.in/ .

- 14. Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Ministry of Labour & Employment. Health and Family Welfare Ministry to Implement RSBY Scheme from Tomorrow. 2015.

- 15. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Directorate General of Health Services, Central Bureau of Health Intellegence. National Health Profile, 2015.

- 17. Universal Health Coverage Project to Revolutionize Health Care Delivery System in Punjab. Directorate of Information and Public Relations, Punjab; 2015.

- 18. Government of Himachal Pradesh, Department of Health and Family Welfare. Order No.: 13454-4676/2014. 2014.

- 19. Escobar ML, Griffin CC, Shaw RP. The impact of health insurance in low-and middle-income countries: Brookings Institution Press; 2011.

- 20. Acharya A, Vellakkal S, Taylor F, Masset E, Satija A, Burke M, et al. Impact of National Health Insurance for the Poor and Informal Sector in Low-and Middle-income Countries: EPPI-Centre; 2012.

- 22. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Quality Assessment Tool forQuantitative Studies Method. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University. (Updated 13 April, 2010). [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2015 12 Nov]. Available from: http://www.nccmt.ca/registry/view/eng/15.html .

- 23. Asian Development Bank. A Review of Recent Developments in Impact Evaluation. 2011. [cited 2016 April 25]. Available from: http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28622/developments-impact-evaluation.pdf .

- 26. Aiyar A, Sharma V, Narayanan K, Jain N, Bhat P, Mahendiran S, et al. Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (A study in Karnataka). 2013.

- 27. The Research Institute Rajagiri College of Social Sciences Kochi, Kerala. RSBY–CHIS Evaluation Survey (Facility Level Survey to Assess Quality of Hospitals in RSBY Network & Post Utilization Survey of RSBY Patient Experience at Empanelled Hospitals in Kerala).

- 28. GIZ. Evaluation of Implementation Process of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana in Select Districts of Bihar, Uttarakhand and Karnataka. 2012.

- 29. Amicus Advisory Private Limited. Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana: Studying Jaunpur (Uttar Pradesh).

- 30. Bergkvist S, Wagstaff A, Katyal A, Singh P, Samarth A, Rao M. What a difference a state makes: health reform in Andhra Pradesh. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2014(6883).

- 31. Dhanaraj S. Health shocks and coping strategies: State health insurance scheme of Andhra Pradesh, India. WIDER Working Paper, 2014.

- 35. Philip NE, Kannan S, Sarma SP. Utilization of comprehensive health insurance scheme, Kerala: a comparative study of insured and uninsured BPL households. BMC Proceedings; 2012: BioMed Central Ltd.

- 37. Ghosh S. Publicly-Financed Health Insurance for the Poor Understanding RSBY in Maharashtra. 2014.

- 38. Patel J, Shah J, Agarwal M, Kedia G. Post utilization survey of RSBY beneficiaries in civil hospital, Ahmedabad: A cross sectional study. 2013.

- 43. Amicus Advisory Pvt. Ltd. Evaluation Study of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana in Shimla & Kangra Districts in Himachal Pradesh.

- 44. Mott MacDonald. Ministry of Labour & Employment. Pilot Post-enrolment Survey of the RSBY Programme in Gujarat, March 2011.

- 48. Hou X, Palacios R. Hospitalization patterns in RSBY: preliminary evidence from the MIS. 2011.

- 49. Krishnaswamy K, Ruchismita R. Performance trends and policy recommendations: an evaluation of the mass health insurance scheme of Government of India. Chennai: Centre for Insurance and Risk Management. 2011.

- 50. Sun C. An analysis of RSBY enrolment patterns: Preliminary evidence and lessons from the early experience. RSBY Working Paper, 2010.

- 51. Shoree S, Ruchismita R, Desai KR. Evaluation of RSBY’s Key performance indicators: A biennial study. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- 53. Thakur H, Ghosh S. Social Exclusion and Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) in Maharashtra. 2013.

- 56. Kilaru A, Saligram P, Giske A, Nagavarapu S. State insurance schemes in Karnataka and users’ experiences–Issues and concerns.

- 62. Arora D. Towards alternative health financing: the experience of RSBY in Kerala. 2010.

- 63. Council for Tribal and Rural Development (CTRD). Final report on evaluation of "Rashtriya Swasthiya Bima Yojana" in Chhattisgarh. 2012.

- 64. Chaupal Gramin Vikas Prashikshan Evum Shodh Sansthan (Chaupal). (2013b). Study on status of Public Health Services at various levels in Chhattisgarh. Unpublished.

- 65. Chaupal Gramin Vikas Prashikshan Evum Shodh Sansthan (Chaupal). (2013a). Study on patient experiences in availing RSBY in private hospitals in Chhattisgarh. Unpublished.

- 66. Mott MacDonald. Pilot Post-enrolment Survey of the RSBY Programme in Haryana, March 2011. Ministry of Labour & Employment

- 67. Rashtriya Swasthiya Bima Yojana. RSBY Connect Issue No. 20. 2013.

- 68. Mor N. The Best Way to Address Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Is Not to Build an MCH Focussed Health System. Available at SSRN 2648846. 2015.

- 70. Bajpai V. The challenges confronting public hospitals in india, their origins, and possible solutions. Advances in Public Health. 2014.

- 74. Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Framework for Implementation of National Health Mission, 2012–2017. [cited 2016 April 27]. Available from: http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/NHM/NRH_Framework_for_Implementation__08-01-2014_.pdf .

- 76. Berman P, Cuizon D. Multiple public-private jobholding of health care providers in developing countries. An exploration of theory and evidence Issue paper-private sector London: Department for International Developmnent Health Systems Resource Centre Publication. 2004.

- 77. Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Health Policy 2015 draft. [cited 2016 April 27]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=3014 .

- 82. Prinja S, Gupta R, Bahuguna P, Sharma A, Aggarwal AK, Phogat A, et al. A Composite Indicator to Measure Universal Health Care Coverage in India: Way Forward for Post-2015 Health System Performance Monitoring Framework. Health Policy Plannning. 2016: pii: czw097. [Epub ahead of print].

Health Insurance in India Opportunities, Challenges and Concerns

- January 2000

- In book: Indian Insurance Industry: Transition and Prospects

- Publisher: New Century Publications, New Delhi

- Editors: Srivastava D C and Srivastava S (eds

- Public Health Foundation of India

- Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Saloni Devi

- Papai Barman

- Ranjan Karmakar

- Amrik Singh

- Harinder Singh

- Pavithra Rajan

- Harneet Kaur

- Saurabh Sharma

- Suruchi Sharma

- Yuti Rohit Chandan

- Dr Waghmare

- A. Sai Bhavana

- P. L. Srinivasa Murthy

- Econ Polit Wkly

- Michael Kent Ranson

- U E Reinhardt

- D C Srivastava

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 07 September 2020

Effect of health insurance program for the poor on out-of-pocket inpatient care cost in India: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey

- Shyamkumar Sriram ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4906-1405 1 &

- M. Mahmud Khan 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 20 , Article number: 839 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

66 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

In India, Out-of-pocket expenses accounts for about 62.6% of total health expenditure - one of the highest in the world. Lack of health insurance coverage and inadequate coverage are important reasons for high out-of-pocket health expenditures. There are many Public Health Insurance Programs offered by the Government that cover the cost of hospitalization for the people below poverty line (BPL), but their coverage is still not complete. The objective of this research is to examine the effect of Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor on hospitalizations and inpatient Out-of-Pocket costs.

Data from the recent national survey by the National Sample Survey Organization, Social Consumption in Health 2014 are used. Propensity score matching was used to identify comparable non-enrolled individuals for individuals enrolled in health insurance programs. Binary logistic regression model, Tobit model, and a Two-part model were used to study the effects of enrolment under Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor on the incidence of hospitalizations, length of hospitalization, and Out-of- Pocket payments for inpatient care.

There were 64,270 BPL people in the sample. Individuals enrolled in health insurance for the poor have 1.21 higher odds of incidence of hospitalization compared to matched poor individuals without the health insurance coverage. Enrollment under the poor people health insurance program did not have any effect on length of hospitalization and inpatient Out-of-Pocket health expenditures. Logistic regression model showed that chronic illness, household size, and age of the individual had significant effects on hospitalization incidence. Tobit model results showed that individuals who had chronic illnesses and belonging to other backward social group had significant effects on hospital length of stay. Tobit model showed that days of hospital stay, education and age of patient, using a private hospital for treatment, admission in a paying ward, and having some specific comorbidities had significant positive effect on out-of-pocket costs.

Conclusions

Enrolment in the public health insurance programs for the poor increased the utilization of inpatient health care. Health insurance coverage should be expanded to cover outpatient services to discourage overutilization of inpatient services. To reduce out-of-pocket costs, insurance needs to cover all family members rather than restricting coverage to a specific maximum defined.

Peer Review reports

Achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is an important goal for almost every nation in the world [ 1 ]. Financial risk protection is one aspect or dimension of UHC and providing financial risk protection is a specific target of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations [ 2 ]. The level of financial protection realized by different population groups depends on the out-of-pocket expenditures (OOP) incurred by them for financing health care [ 3 , 4 ]. High OOP health expenditures, by definition, happens when households decide to access and utilize health care services but do not have protection against high expenditures due to high medical care costs and/or lack of access to insurance coverage and other safeguards against out of pocket costs [ 5 ]. Evidence from Indian National Health Account 2017 shows that OOP health expenditures for inpatient care constitutes around 32% of the total OOP health expenditures, despite the coverage offered by various health insurance programs [ 6 ]. The public healthcare system in India, with geographically distributed primary health centers and sub-centers, is very weak and lacks basic infrastructure. In addition, waiting times in the public sector primary health care facilities are very long, encouraging most of the patients to choose private providers for their health care needs [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Increasing propensity to use private sector health care providers increases the costs and lack of health insurance coverage and inadequate coverage make the OOP expenditure high with negative impacts on health care utilization [ 10 ]. Since cost of inpatient services is high, protecting households from hospital OOP expenses should significantly improve financial equity in health service delivery. Moreover, access to health care can be improved significantly if the system can protect the poor households from significant OOP expenses. In order to improve access to health care by the poor, India initiated a number of health insurance programs since 2008 [ 10 ]. This paper advances our knowledge about financial risk protection and effect of health insurance programs for the poor on access, utilization and out-of-pocket expenses in India.

The increase in health insurance coverage may lead to increase in health care utilization because of the change in behavior of the insured as well as the health care provider. A study by Anderson et al. (2012) in the USA found that there was a 61% reduction in inpatient hospital admissions and 40% reduction in emergency department visits among the uninsured population compared to insured population with similar sociodemographic characteristics [ 11 ]. Evidence from literature has shown that increased health insurance coverage leads to increase in utilization of health services, but the effect of health insurance coverage on financial risk protection is less clear, especially for poor beneficiaries [ 12 ]. This is because, there are two opposing forces in play due to increased coverage of insurance; one aspect is the increased access and utilization due to insurance coverage, which increases total health care cost and second, even with lower OOP rates per service, total OOP may actually become higher due to higher utilization. The health insurance for the poor in India covers only inpatient services. This creates an incentive for the patients to visit hospitals and get hospitalized, instead of using basic primary health care services. Studies on hospitalization trends in India showed that an annual hospitalization rate increased from 16.6 per 1000 population to 37.0 per 1000 from 1995 to 2014 [ 13 ]. Although, we expect to see an increase in hospital utilization rate with improving access and availability, a part of this increase may be due to hospital insurance offered to the poor by the Government of India.

There are many Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor offered by the Government of India (GOI) and some states to cover the cost of hospitalization and inpatient care [ 14 ]. RSBY is a health insurance program started by the Ministry of Labor and Employment of the GOI in April 2008 and it provides a wide range of hospital-based healthcare services to Below Poverty Line (BPL) families [ 15 ]. There are a number of state-run public health insurance programs for the poor in three of the southern states in India which provide higher coverage than RSBY and are exempted from the national program. The programs are the Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme in Tamil Nadu State, Rajiv Aarogyasri Community Health Insurance (RACHI) in Andhra Pradesh State, and Vajpayee Aarogyasri Scheme (VAS) in Karnataka State [ 14 ]. Table 1 summarizes the important features of the national RSBY program and the state health insurance programs for the poor in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

Around 41 million families are enrolled in RSBY, covering around 150 million poor people as of September 2016. The enrolment under the program has been increasing starting from only 55 districts in 2008–2009. Nationally, around 460 districts participate in the program, with 57% of the eligible households are currently enrolled [ 16 ]. There is significant inter-district and inter-state variation in the percentage of eligible households enrolled in RSBY. Across states, the degree of enrolment of households varies from a low of 24% in Arunachal Pradesh and 36% in Haryana to more than 75% in Kerala. The degree of enrollment of households by district varies significantly across the country, with a low rate of enrollment of 3% in Kannauj district and 6% in Kanpur district in the Uttar Pradesh state to a high enrollment rate of 90% of households in most of districts in the Chhattisgarh and Kerala states of India. Enrolment is not complete in many states, even a decade after the start of the program. Also, as of September 2016, the state of Rajasthan was still in its early stage for enrolling households in RSBY [ 16 ]. This shows that enrollment in the RSBY program has been slow in some parts of India. Not all states in India participate in RSBY. The state of Andhra Pradesh has not adopted RSBY as it already has a substantially more generous state level health insurance program than RSBY which pre-dates RSBY with relatively high population coverage, covering nearly 80% of its population [ 17 ]. Studies show that coverage rate of RSBY is low with half of the poor individuals not covered because of problems with targeting due to incomplete information on poor individuals and households, high migration rates among the poor [ 16 ] and possibly the rapid changes in social mobility.

Under the Public Health Insurance Programs for the poor only the hospitalization services and expenses associated with inpatient care are covered. It is expected that the health insurance for the poor will increase utilization of hospital services by the BPL households who would usually be forced to postpone their non-urgent procedures for a later time because of cost. Even with insurance, there may be OOP payments for drugs, tests and post-treatment care which are not covered by the health insurance. Therefore, hospital insurance may actually end-up increasing the OOP payments for inpatient and inpatient-related care for the poor. Hence the direction of effect of the Poor People Health Insurance Programs on total inpatient OOP health expenditure is unclear. Also, RSBY may lead to misuse of services, since both the physician and the patient have the incentive to convert an outpatient case into an inpatient admission, leading to unnecessary utilization [ 18 ]. The objective of this research is to examine the effect of Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor on incidence of hospitalizations and inpatient OOP health expenditures.

Many studies show that people incur high OOP health expenditures despite being covered by the national health insurance program RSBY or other state health insurance programs [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. However, studies on state health insurance programs in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh showed that OOP health expenditures significantly declined with health insurance coverage [ 17 , 25 , 26 ]. Cross-sectional studies done in Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra show that the utilization of healthcare was significantly higher among the insured compared to the uninsured population [ 27 ].

Previous studies on Poor People’s Health Insurance Programs such as RSBY dealt with issues related to program enrolment [ 28 ], barriers in implementation of the program [ 22 ], effect of information campaign [ 29 ], hospitalization patterns [ 30 ], and determinants of participation in the program [ 31 ]. There are only two district level studies on RSBY, one done in Amaravati district in Maharashtra [ 32 ] and the other in Gujarat [ 19 ], that showed increased hospitalizations and higher OOP health expenditures among the RSBY insured individuals. The study in Gujarat found that RSBY enrollees experienced higher OOP health expenditures because they had to pay for medicines and diagnostics during the hospital admission [ 25 ]. In contrast, another state level study for the Aarogyasri program found that insurance significantly reduced the OOP health expenditures for hospitalizations [ 17 ]. Most of other studies that studied the effect of health insurance on hospitalizations and OOP health expenditures were community-based health insurance programs in different parts of the country [ 25 , 33 , 34 , 35 ] and thus limiting its usefulness for national decision-making.

This study is a considerable improvement over other studies on Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor in India on two important counts: i) the study uses nationally representative dataset which helps in estimating pan-India effects of Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor ii) the study evaluates the effect of Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor by comparing outcomes between poor people enrolled and not-enrolled in the insurance program. Many studies are based on RSBY enrollees alone and do not have any controls making it difficult to identify the effects of the Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor. This study identified comparable control population from among those who are poor but were not enrolled in the insurance program. The specific research questions that will be addressed in this research are: (i) How do hospitalizations differ between the enrolled and not-enrolled groups under Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor? and (ii) How does OOP health expenditure for inpatient care differ among people enrolled and not-enrolled under Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor?

Data source

The data from the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) of the GOI were used for the study [ 36 ]. The NSSO is a national organization under the Ministry of Statistics and Implementation which was established in 1950 to regularly conduct surveys and provide useful statistics in the field of socio-economic status of households, demography, health, industries, agriculture, consumer expenditure etc. The specific data set from NSSO that was used in this study is the Social Consumption (Health), NSS 71st Round for 2014, which is the latest nationwide data available for India. The survey covered whole of the Indian Union. The survey used the interview method of data collection from a sample of 65,932 randomly selected households (36,480 in rural India and 29,452 in urban India) and 335,499 individuals, covering the members of the household in all the 36 states (including union territories). The data for the survey were collected over a period of six months, from January to June 2014. The NSSO Social Consumption (Health) collected data on demographic characters, employment, health conditions, source of payments, health insurance coverage, type of coverage, costs of various inpatient services, level of care, type of care and a number of other variables. The survey also collected information on medical care received at inpatient and outpatient facilities of medical institutions including health expenditures for various episodes of illness. This is the first NSSO health survey that collected data on utilization of alternative medicines. The details of hospitalization for all current and former members of the household were collected for the last 365 days (hospitalization occurred from January 2013 to June 2014) and the details of outpatient services were collected for the last 15 days.

Estimation of OOP health expenditures

‘Total Out-of-Pocket health expenditures for inpatient care’ is defined as the total health expenditure for inpatient care net of reimbursement by health insurance. It is a continuous variable calculated in Indian Rupees (INR). In the data provided by the government of India, hospitalization expenses were included under two heads namely medical (direct) and direct non-medical (indirect) costs. Direct medical expenditure consists of package component and non-package component (doctor fee, medicines, diagnostic tests, bed charges, other medical expenses) and direct non-medical expenditure consists of transport for patient, transport for others, lodging charges of escort, food expenses, and other expenses. There is a separate variable in the data which provided the “amount reimbursed by the health insurance”. All these variables were used to derive the OOP health expenditure for inpatient care.

Total inpatient healthcare expenditure = (Medical expenditure, X) + (Direct Non-Medical.

Expenditure, Y).

Total out-of-pocket inpatient health expenditure = (Total inpatient healthcare expenditure) –.

(Amount reimbursed by the health insurance, Z)

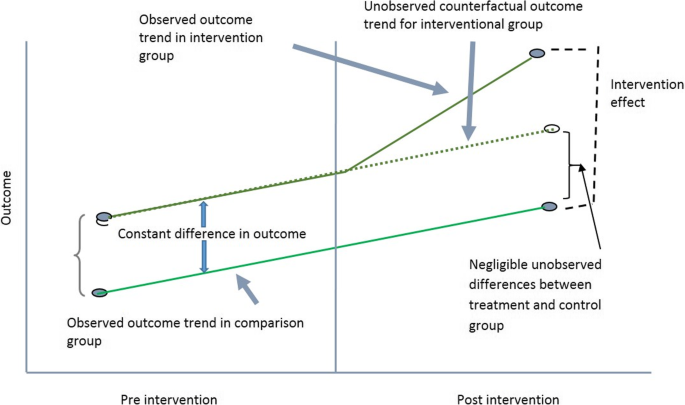

Empirical methodology

The main objective of this study is to estimate the effect of Public Health Insurance Programs for the Poor on hospitalizations and OOP inpatient care costs. The effects of the program were estimated by comparing the probability of hospitalizations and OOP inpatient healthcare costs between the groups who are eligible (poor) and covered by the insurance programs and who are eligible (poor) but not covered. In theory, the best approach of estimating the impact of a program is to adopt a Difference-in-difference (DID) framework with randomized allocation of eligible individuals in the program group and the no-program group. The framework requires data on the two groups in the pre-intervention period and then in the post-intervention period [ 37 ]. DID estimators compare the change in mean outcomes before and after the intervention among individuals who acquire coverage (treated) and those remaining not exposed.

To estimate the causal effect using DID, the assumptions of DID must be satisfied. The main assumptions are that the treatment and control groups have parallel trends in outcome, the composition of the treatment and control groups are stable for repeated cross-sectional design, the allocation of treatment is unrelated to the outcome at baseline, and there are no spillover effects. The most important assumption for DID is the ‘parallel trend assumption’. This means that in the absence of the intervention/treatment, the average difference in the outcome between the treatment and control groups would have remained constant in post-intervention time period as in pre-intervention period. The violation of this assumption will imply that the DID approach will not be able to obtain unbiased estimates of program impacts. The DID model cannot be used if composition of the pre-intervention and post-intervention groups are not stable, if the comparison group has a different outcome trend, and if the allocation of the treatment/intervention is determined by the baseline outcome [ 37 ].

However, the treated and untreated may differ in the distribution of both observable and unobservable characteristics. Heckman and Vytlacil (2007) highlighted that unobservable variables may play a bigger (or smaller) role in influencing the with-treatment outcome than the without-treatment outcome [ 38 ]. Inability to control for them is likely to provide under (over) estimation of the effects of the programs. Since the main assumption of DID is parallel trend assumption and checking for the constant difference in outcome over time is necessary for deriving impact of a program or intervention using DID approach.

For the purpose of this study, a number of simplifying assumptions must be made as the data set is cross-sectional in nature and we only observe the outcomes in the year the data were collected. Therefore, the data set does not provide any information on the individuals who were enrolled in the insurance program in the previous period and those who were not enrolled. The insurance program is designed for the poor households and since belonging to the poverty group is a dynamic event, a household in poverty in pre-insurance period may not necessarily be in poverty in the post-intervention period. Moreover, household in poverty in the current year (the year of data collection) may not have been in poverty in the previous period. Almost all programs also show some degree of mistargeting implying that some poor people may not be offered the insurance while some non-poors are offered the insurance benefit. These potential deviations from expected enrollment may affect the estimate of outcomes when a post-intervention year’s data are used.