- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplement Archive

- Editorial Commentaries

- Perspectives

- Cover Archive

- IDSA Journals

- Clinical Infectious Diseases

- Open Forum Infectious Diseases

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Why Publish

- IDSA Journals Calls for Papers

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Branded Books

- Journals Career Network

- About The Journal of Infectious Diseases

- About the Infectious Diseases Society of America

- About the HIV Medicine Association

- IDSA COI Policy

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- For Reviewers

- For Press Offices

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Unconscious bias—the role it plays and how to measure it, impact of bias on healthcare delivery, measuring bias—the implicit association test (iat), mitigating unconscious bias, call to action.

- < Previous

The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jasmine R Marcelin, Dawd S Siraj, Robert Victor, Shaila Kotadia, Yvonne A Maldonado, The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It, The Journal of Infectious Diseases , Volume 220, Issue Supplement_2, 15 September 2019, Pages S62–S73, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz214

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The increasing diversity in the US population is reflected in the patients who healthcare professionals treat. Unfortunately, this diversity is not always represented by the demographic characteristics of healthcare professionals themselves. Patients from underrepresented groups in the United States can experience the effects of unintentional cognitive (unconscious) biases that derive from cultural stereotypes in ways that perpetuate health inequities. Unconscious bias can also affect healthcare professionals in many ways, including patient-clinician interactions, hiring and promotion, and their own interprofessional interactions. The strategies described in this article can help us recognize and mitigate unconscious bias and can help create an equitable environment in healthcare, including the field of infectious diseases.

There is compelling evidence that increasing diversity in the healthcare workforce improves healthcare delivery, especially to underrepresented segments of the population [ 1 , 2 ]. Although we are familiar with the term “underrepresented minority” (URM), the Association of American Medical Colleges, has coined a similar term, which can be interchangeable: “Underrepresented in medicine means those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population” [ 3 ]. However, this definition does not include other nonracial or ethnic groups that may be underrepresented in medicine, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning/queer (LGBTQ) individuals or persons with disabilities. US census data estimate that the prevalence of African American and Hispanic individuals in the US population is 13% and 18%, respectively [ 4 ], while the prevalence of Americans identifying as LGBT was estimated by Gallup in 2017 to be about 4.5% [ 5 ]. Yet African American and Hispanic physicians account for a mere 6% and 5%, respectively, of medical school graduates, and account for 3% and 4%, respectively, of full-time medical school faculty [ 6 ]. As for LGBTQ medical graduates, the Association of American Medical Colleges does not report their prevalence [ 6 ]. Persons with disabilities are estimated to be 8.7% of the general population [ 4 ], while the prevalence of physicians with disabilities has been estimated to be a mere 2.7% [ 7 ]. Furthermore, although women currently outnumber men in first-year medical school classes [ 8 ], gender disparities still exist at higher ranks in women’s medical careers [ 9–11 ].

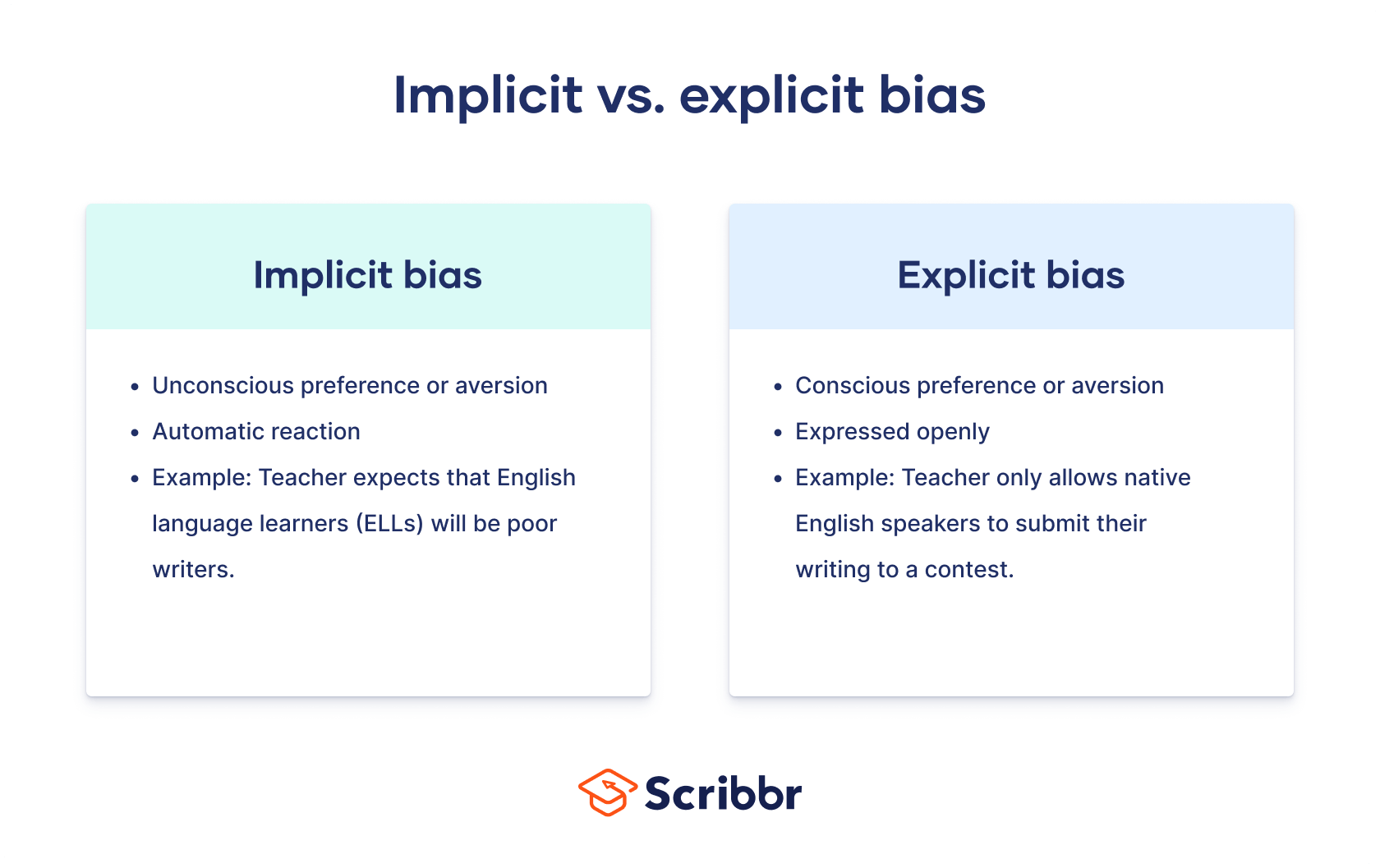

Unconscious or implicit bias describes associations or attitudes that reflexively alter our perceptions, thereby affecting behavior, interactions, and decision-making [ 12–14 ]. The Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) notes that bias, stereotyping, and prejudice may play an important role in persisting healthcare disparities and that addressing these issues should include recruiting more medical professionals from underrepresented communities [ 1 ]. Bias may unconsciously influence the way information about an individual is processed, leading to unintended disparities that have real consequences in medical school admissions, patient care, faculty hiring, promotion, and opportunities for growth ( Figure 1 ). Compared with heterosexual peers, LGBT populations experience disparities in physical and mental health outcomes [ 15 , 16 ]. Stigma and bias (both conscious and unconscious) projected by medical professionals toward the LGBTQ population play a major role in perpetuating these disparities [ 17 ]. Interventions on how to mitigate this bias that draw roots from race/ethnicity or gender bias literature can also be applied to bias toward gender/sexual minorities and other underrepresented groups in medicine.

Glossary of key terms.

The specialty of infectious diseases is not free from disparities. Of >11 000 members of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), 41% identify as women, 4% identify as African American, 8% identify as Hispanic, and <1% identify as Native American or Pacific Islander (personal communication, Chris Busky, IDSA chief executive officer, 2019). However, IDSA data on members who identify as LGBTQ and members with disabilities are not available.

The 2017 IDSA annual compensation survey reports that women earn a lower income than men [ 18 ], and a review of the full report demonstrates similar disparities among URM physicians, compared with their white peers [ 19 ]. While it may not be feasible to assign a direct causal relationship between unconscious bias and disparities within the infectious diseases specialty, it is reasonable and ethical to attempt to address any potential relationship between the two. In this article, we define unconscious bias and describe its effect on healthcare professionals. We also provide strategies to identify and mitigate unconscious bias at an organizational and individual level, which can be applied in both academic and nonacademic settings.

Even in 2019, overt racism, misogyny, and transphobia/homophobia continue to influence current events. However, in the decades since the healthcare community has moved toward becoming more egalitarian, overt discrimination in medicine based on gender, race, ethnicity, or other factors have become less conspicuous. Nevertheless, unconscious bias still influences all human interactions [ 13 ]. The ability to rapidly categorize every person or thing we encounter is thought to be an evolutionary development to ensure survival; early ancestors needed to decide quickly whether a person, animal, or situation they encountered was likely to be friendly or dangerous [ 20 ]. Centuries later, these innate tendencies to categorize everything we encounter is a shortcut that our brains still use.

Stereotypes also inadvertently play a significant role in medical education ( Figure 1 ). Presentation of patients and clinical vignettes often begin with a patient’s age, presumed gender, and presumed racial identity. Automatic associations and mnemonics help medical students remember that, on examination, a black child with bone pain may have sickle-cell disease or a white child with recurrent respiratory infections may have cystic fibrosis. These learning associations may be based on true prevalence rates but may not apply to individual patients. Using stereotypes in this fashion may lead to premature closure and missed diagnoses, when clinicians fail to see their patients as more than their perceived demographic characteristics. In the beginning of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, the high prevalence of HIV among gay men led to initial beliefs that the disease could not be transmitted beyond the gay community. This association hampered the recognition of the disease in women, children, heterosexual men, and blood donor recipients. Furthermore, the fact that white gay men were overrepresented in early reported prevalence data likely led to lack of recognition of the epidemic in communities of color, a fact that is crucial to the demographic characteristics of today’s epidemic. Today, there is still no clear solution to learning about the epidemiology of diseases without these imprecise associations, which can impact the rapidity of accurate diagnosis and therapy.

Unconscious bias describes associations or attitudes that unknowingly alter one’s perceptions and therefore often go unrecognized by the individual, whereas conscious bias is an explicit form of bias that is based on one’s discriminatory beliefs and values and can be targeted in nature [ 14 ]. While neither form of bias belongs in the healthcare profession, conscious bias actively goes against the very ethos of medical professionals to serve all human beings regardless of identity. Conscious bias has manifested itself in severe forms of abuse within the medical profession. One notable historical example being the Tuskegee syphilis study, in which black men were targeted to determine the effects of untreated, latent syphilis. The Tuskegee study demonstrated how conscious bias, in this case manifested in the form of racism, led to the unethical treatment of black men that continues to have long-lasting effects on health equity and justice in today’s society [ 21 ]. Given the intentional nature of conscious bias, a different set of tools and a greater length of time are likely required to change one’s attitudes and actions. Tackling unconscious bias involves willingness to alter one’s behaviors regardless of intent, when the impact of one’s biases are uncovered and addressed [ 22 ]

There is still debate, however, about the degree to which unconscious bias affects clinician decision-making. In one systematic review on the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare delivery, there was strong evidence demonstrating the prevalence of unconscious bias (encompassing race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, age, weight, persons living with HIV, disability, and persons who inject drugs) affecting clinical judgment and the behavior of physicians and nurses toward patients [ 12 ]. However, another systematic review found only moderate-quality evidence that unconscious racial bias affects clinical decision-making [ 23 ]. A detailed discussion of the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare delivery is out of the scope of this article, which is focused on the impact of unconscious bias as it relates to healthcare professionals themselves. Nevertheless, strategies to mitigate the effects of unconscious bias (discussed later) can be applied to healthcare delivery and patient interactions.

While we know that unconscious bias is ubiquitous, it can be difficult to know how much it affects a person’s daily interactions. In many cases, an individual’s unconscious beliefs may differ from their explicit actions. For example, healthcare professionals, if asked, might say they try to treat all patients equally and may not believe they hold negative attitudes about patients. However, by definition, they may lack awareness of their own potential unconscious biases, and their actions may unknowingly suggest that these biases are active.

To measure unconscious bias, Drs Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald developed the IAT in 1998 [ 24 ]. Many versions of the IAT are accessible online (available at: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/ ), but one of the most studied is the Race IAT. The IAT has been extensively studied as an inexpensive tool that provides feedback on an individual biases for self-reflection. The IAT calculates how quickly people associate different terms with each other. To determine unconscious race bias, the race IAT asks the subject to sort pictures (of white and black people) and words (good or bad) into pairs. For example, in one part of the Race IAT, participants must associate good words with white people and bad words with black people. In another part of the Race IAT, they must associate good words with black people and bad words with white people. Based on the reaction times needed to perform these tasks, the software calculates a bias score [ 20 , 24 ]. Category pairs that are unconsciously preferred are easier to sort (and therefore take less time) than those that are not [ 24 ]. These unconscious associations can be identified even in individuals who outwardly express egalitarian beliefs [ 20 , 24 ]. According to Project Implicit, the Race IAT has been taken >4 million times between 2002 and 2017, and 75% of test takers demonstrate an automatic white preference, meaning that most people (including a small group of black people) automatically associate white people with goodness and black people with badness [ 20 ]. Proponents of the IAT state that automatic preference for one group over another can signal potential discriminatory behavior even when the individuals with the automatic preference outwardly express egalitarian beliefs [ 20 ]. These preferences do not necessarily mean that an individual is prejudiced, which is associated with outward expressions of negative attitudes toward different social groups [ 20 ].

Many of the studies of unconscious bias described in this article use the IAT as the primary tool for measuring the phenomenon. Nevertheless, the degree to which the IAT predicts behavior is as of yet unclear, and it is important to recognize the limitations and criticisms of the IAT, as this is pertinent to its potential application in mitigating unconscious bias. Blanton et al reanalyzed data from 2 studies supporting the validity of the IAT, claiming that there is no evidence predicting individual behavior, with concerns for interjudge reliability and inclusion of outliers affecting results [ 25 ]. Response to this criticism by McConnell et al describes extensive training of test judges and evidence that the reanalysis was not a perfect replication of methods [ 26 ]. Blanton et al argue further in a different article that attempting to explain behavior on the basis of results of the IAT is problematic because the test relies on an arbitrary metric, leading to identified preferences when individuals are “behaviorally neutral” [ 27 ]. Notwithstanding the limitations of the IAT, none of its critics refute the existence of unconscious bias and that it can influence life experiences. The following sections review how unconscious bias affects different groups in the healthcare workforce.

Racial Bias

Medical school admissions committees serve as an important gatekeeper to address the significant disparities between racial and ethnic minorities in healthcare as compared to the general population. Yet one study demonstrated that members of a medical school admissions committee displayed significant unconscious white preference (especially among men and faculty members) despite acknowledging almost zero explicit white preference [ 28 ]. An earlier study of unconscious racial and social bias in medical students found unconscious white and upper-class preference on the IAT but no obvious unconscious preferences in students’ response to vignette-based patient assessments [ 29 ]. Unconscious bias affects the lived experiences of trainees, can potentially influence decisions to pursue certain specialties, and may lead to isolation. A recent study by Osseo-Asare et al described African American residents’ experiences of being only “one of a few” minority physicians; some major themes included discrimination, the presence of daily microaggressions, and the burden of being tasked as race/ethnic “ambassadors,” expected to speak on behalf of their demographic group [ 30 ].

Gender Bias

Gender bias in medical education and leadership development has been well documented [ 11 , 31 ]. Medical student evaluations vary depending on the gender of the student and even the evaluator [ 31 ]. Similar studies have demonstrated gender bias in qualitative evaluations of residents and letters of recommendations, with a more positive tone and use of agentic descriptors in evaluations of male residents as compared to female residents [ 11 ]. Studies evaluating inclusion of women as speakers have also demonstrated gender bias, with fewer women invited to speak at grand rounds [ 9 ] and differences in the formal introductions of female speakers as compared to male speakers [ 32 , 33 ], with men more likely referred to by their official titles than women.

Sexual and Gender Minority Bias

Sexual and gender minority groups are underrepresented in medicine and experience bias and microaggressions similar to those experience by racial and ethnic minorities. Experiences with or perceptions of bias lead to junior physicians not disclosing their sexual identity on the personal statement part of their residency applications for fear of application rejection or not disclosing that they are gay to colleagues and supervisors for fear of rejection or poor evaluations [ 34 ]. In one study, some physician survey respondents indicated some level of discomfort about people who are gay, transgender, or living with HIV being admitted to medical school. These respondents were less likely to refer patients to physician colleagues who were gay, transgender, or living with HIV [ 35 ]. These explicit biases were significantly reduced, compared with those revealed in prior surveys done in 1982 and 1999; opposition to gay medical school applicants went from 30% in 1982 to 0.4% in 2017, and discomfort with referring patients to gay physicians went from 46% in 1982 to 2% in 2017 [ 35 ]. The 2017 survey did not measure levels of unconscious bias, which is likely to still be pervasive despite decreased explicit bias. As with other types of bias, these data reveal that explicit bias against gay physicians has decreased over time; the degree of unconscious bias, however, likely persists. While this is encouraging to some degree, unconscious bias may be much more challenging to confront than explicit bias. Thus, members of underrepresented groups may be left wondering about the intentions of others and being labeled as “too sensitive.”

Studies including the perspectives of LGBTQ healthcare professionals demonstrate that major challenges to their academic careers persist to this day. These include lack of LGBTQ mentorship, poor recognition of scholarship opportunities, and noninclusive or even hostile institutional climates [ 36 ]. Phelan et al studied changes in biased attitudes toward sexual and gender minorities during medical school and found that reduced unconscious and explicit bias was associated with more-frequent and favorable interactions with LGBTQ students, faculty, residents, and patients [ 37 ].

Disability Bias

Physicians with disabilities constitute another minority group that may experience bias in medicine, and the degree to which they experience this may vary, depending on whether disabilities may be visible or invisible. One study estimated the prevalence of self-disclosed disability in US medical students to be 2.7% [ 7 ]. Medical schools are charged with complying with the Americans With Disabilities Act, but only a minority of schools support the full spectrum of accommodations for students with disabilities [ 38 ]. Many schools do not include a specific curriculum for disability awareness [ 39 ]. Physicians with disabilities have felt compelled to work twice as hard as their able-bodied peers for acceptance, struggled with stigma and microaggressions, and encountered institutional climates where they generally felt like they did not belong [ 40 ]. These are themes that are shared by individuals from racial and ethnic minorities.

A strategy to counter unconscious bias requires an intentional multidimensional approach and usually operates in tandem with strategies to increase diversity, inclusion, and equity [ 41 , 42 ]. This is becoming increasingly important in training programs in the various specialties, including infectious diseases. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education recently updated their common program requirements for fellowship programs and has stipulated that, effective July 2019, “[t]he program’s annual evaluation must include an assessment of the program’s efforts to recruit and retain a diverse workforce” [ 43 ]. The implication of this requirement is that recognition and mitigation of potential biases that may influence retention of a diverse workforce will ultimately be evaluated (directly or indirectly).

Mitigating unconscious bias and improving inclusivity is a long-term goal requiring constant attention and repetition and a combination of general strategies that can have a positive influence across all groups of people affected by bias [ 44 ]. These strategies can be implemented at organizational and individual levels and, in some cases, can overlap between the 2 domains ( Figure 2 ). In this section, we review how infectious diseases clinicians and organizations like IDSA and hospitals can use some of these strategies to address and mitigate implicit bias in our specialty.

Organization-level and personal-level strategies to mitigate unconscious bias. Orange circles indicate organization-specific strategies, green circles indicate individual-level strategies, and blue circles represent strategies that can be emphasized on both organizational and individual levels to mitigate implicit bias.

Organizational Strategies

Commitment to a culture of inclusion: more than just diversity training or cultural competency.

Creating change requires more than just a climate survey, a vision statement, or creation of a diversity committee [ 45 ]. Organizations must commit to a culture shift by building institutional capacity for change [ 41 , 46 ]. This involves reaffirming the need not only for the recruitment of a critical mass of underrepresented individuals, but equally importantly, the recruitment of critical actor leaders who take the role of change agents and have the power to create equitable environments [ 41 , 47–49 ]. These change agents need not themselves be underrepresented; indeed, the success of culture change requires the involvement of allies within the majority group (eg, men, white people, and cis-gender heterosexual individuals). IDSA has demonstrated a commitment to this type of culture change with recent changes in leadership structure and with intentional recruitment of individuals invested in diversity and inclusion; however, there is always room for reevaluation of other areas where diversity is desired.

Committing to a culture of inclusion at the academic-institution level involves creating a deliberate strategy for medical trainee admission and evaluation and faculty hiring, promotion, and retention. Capers et al describe strategies for achieving diversity through medical school admissions, many of which can also be applied to faculty hiring and promotion [ 49 ]. Notable strategies they suggest include having admissions (or hiring) committee members take the IAT and reflect on their own potential biases before they review applications or interview candidates [ 49 ]. They also recommend appointing women, minorities, and junior medical professionals (students or junior faculty) to admissions committees, emphasizing the importance of different perspectives and backgrounds [ 49 ]. Organizations can also survey employee perception of inclusivity. These assessments include questions on the degree to which an individual feels a sense of belonging within an institution, alongside questions pertaining to experiences of bias on the grounds of cultural or demographic factors [ 50 ]. Conducting regular assessments and analysis of survey results, particularly on how individuals of diverse backgrounds feel they can exist within the organization and their culture simultaneously, allows organizations to ensure that their trainings on unconscious bias and promotion of cultural humility lead to long-term positive change. Furthermore, realizing that different demographic groups may feel less respected than others provides information on areas of focus for consequent refresher seminars on combating unconscious bias in conjunction with cultural humility.

Meaningful Diversity Training and the Usefulness of the IAT

Notwithstanding potential criticisms of the IAT with respect to prediction of discriminatory behavior, this can be a useful tool within a comprehensive organizational training seminar directed toward understanding and addressing individual unconscious bias. In the study by Capers et al, over two thirds of admissions committee members who took the IAT and responded to the post-IAT survey felt positive about the potential value of this tool in reducing their unconscious bias [ 28 ]. Additionally, almost half were cognizant of their IAT results when interviewing for the next admissions cycle, and 21% maintained that knowledge of this bias affected their decisions in the next admissions cycle [ 28 ]. Perhaps this knowledge led to conscious changes in committee member behavior because, in the following year, the matriculating class was the most diverse in that institution’s history [ 28 , 49 ]. A similar bias education intervention coupled with the IAT led to a decreased unconscious gender leadership bias in one academic center [ 48 ]. IDSA and infectious diseases practices (or academic divisions) could consider ways to incorporate this into already established training for those in leadership roles or on leadership search committees.

Of course, the potential applicability of the IAT can be overstated—at best, several meta-analyses have demonstrated that there may only be a weak correlation between IAT scores and individual behavior [ 51–53 ], and several criticisms of the IAT have already been discussed here. Additionally, while important to acknowledge that bias is pervasive, care must be taken to avoid normalizing bias and stereotypes because this may have the unintended consequence of reinforcing them [ 54 ]. Important points that should be emphasized when using the IAT as part of diversity training include that (1) people should be aware of their own biases and reflect on their behaviors individually; (2) the IAT can suggest generally how groups of people with certain results may behave, rather than how each individual will behave; and (3) on its own, the IAT is not a sufficient tool to mitigate the effects of bias, because if there is to be any chance of success, an active cultural/behavioral change must be engaged in tandem with bias awareness and diversity training [ 55 ].

Individual Strategies

Deliberative reflection.

Before encounters that are likely to be affected by bias (such as trainee evaluations, letters of recommendation, feedback, interviews, committee decisions, and patient encounters), deliberative reflection can help an individual recognize their own potential for bias and correct for this [ 56 ]. It is also a good time to consider the perspective of the individual whom they will be evaluating or interacting with and the potential impact of their biases on that individual. Participants can be encouraged to evaluate how their own experiences and identities influence their interactions. Including data on lapses in proper care due to provider bias also proves helpful in giving workers real-life examples of the consequences of not being vigilant for bias [ 51 , 57 ]. This motivated self-regulation based on reflections of individual biases has been shown to reduce stereotype activation and application [ 44 , 58 ]. If one unintentionally behaves in a discriminatory manner, self-reflection and open discussion can help to repair relationships ( Figure 3 ).

Strategies to address personal bias before and after it occurs.

Question and Actively Counter Stereotypes

Individuals may question how they can actively counter stereotypes and bias in observed interactions. The active-bystander approach adapted from the Kirwan Institute [ 59 ] can provide insight into appropriate responses in these situations ( Figure 4 ).

Kirwan Institute approach to countering unconscious bias as an active bystander.

Strategies That Apply to Both Organizations and Individuals

Cultural competency and beyond: cultural humility.

Healthcare organizations seeking to develop providers who can work seamlessly with colleagues and more effectively treat patients from all cultural backgrounds have been conducting trainings in cultural competency [ 60 ]. The term “cultural competency” implies that one has achieved a static goal of championing inclusivity. This approach imparts a false sense of confidence in leaders and healthcare professionals and fails to recognize that our understanding of cultural barriers is continually growing and evolving [ 61 ]. Cultural humility has been proposed as an alternate approach, subsuming the teachings of cultural competency while steering participants toward a continuous path of discovery and respect during interactions with colleagues and patients of different cultural backgrounds [ 62 ]. Other synonymous terms include “cultural sensitivity” and “cultural curiosity.” Rather than checking a box for training, cultural humility focuses on the individual and teaches that developing one’s self-awareness is a critical step in achieving mindfulness for others [ 63 ]. Cultural humility emphasizes that individuals must acknowledge the experiential lens through which they view the world and that their view is not nearly as extensive, open, or dynamic as they might perceive [ 61 ]. By training leaders and healthcare professionals that they do not need to be and ultimately cannot be experts in all the intersecting cultures that they encounter, healthcare professionals can focus on a readiness to learn that can translate to greater confidence and willingness in caring for patients of varying backgrounds [ 61 ].

As cultural humility is important to recognizing and mitigating conscious and unconscious biases, patient simulations and diversity-related trainings should be augmented with discussions about cultural humility. By integrating cultural humility into healthcare training procedures, organizations can strive to eliminate the perceived unease healthcare professionals might experience when interacting with individuals from backgrounds or cultures unfamiliar to them. Cultural humility starts from a condition of empathy and proceeds through the asking of open questions in each interaction ( Figure 1 ). Instilling elements of cultural humility training within simulation-based learning provides participants with experience in treating a wide array of patients while providing low-risk, feedback-based learning opportunities [ 22 , 64 ].

Diversify Experiences to Provide Counterstereotypical Interactions

Exposing individuals to counterstereotypical experiences can have a positive impact on unconscious bias [ 10 , 44 , 55 ]. Therefore, intentional efforts to include faculty from underrepresented groups as preceptors, educators, and invited speakers can help reduce the unconscious associations of these responsibilities as unattainable. Capers et al suggest that including students, women, and African Americans and other racial and ethnic minorities on admissions committees may be part of a strategy to reduce unconscious bias in medical school admissions [ 49 ]. If institutions, organizations, and conference program committees are aware of their own metrics in this respect, following this information with deliberate choices to remedy inequities can have a profound impact on increasing diversity [ 65 ]. Furthermore, in medical training, while deliberate curricula involving disparities and care of underrepresented individuals are beneficial, educators must be aware of the impact of the hidden curriculum on their trainees. The term “hidden curriculum” refers to the aspects of medicine that are learned by trainees outside the traditional classroom/didactic instruction environment. It encompasses observed interactions, behaviors, and experiences often driven by unconscious and explicit bias and institutional climate [ 66–68 ]. Students can be taught to actively seek out the hidden curriculum in their training environment, reflect on the lessons, and use this reflection to inform their own behaviors [ 67 ]. Individuals can intentionally diversify their own circles, connecting with people from different backgrounds and experiences. This can include the occasionally awkward and uncomfortable introductions at professional meetings or at community events, making an effort to read books by diverse authors, or trying new foods with a colleague. These are small behavioral changes that, with time, can help to retrain our brain to classify people as “same” instead of “other.”

Mentorship and Sponsorship

Mentors can, at any stage in one’s career, provide advice and career assistance with collaborations, but sponsors are typically more senior individuals who can curate high-profile opportunities to support a junior person, often with potential personal or professional risk if that person does not meet expectations. URMs and women physicians tend not to have as much support with mentoring and sponsorship as the majority group, white men. Qualitative studies of URM physician perspectives typically reveal themes of isolation and lack of mentorship, regardless of the URM group being studied [ 30 , 36 , 69 ]. Possible reasons include lack of mentors from similar backgrounds or ineffective mentoring in discordant mentor-mentee relationships. Mentor-training workshops that intentionally include unconscious bias training can enhance the effectiveness of mentors working with diverse trainees and junior faculty and address this potential barrier to URM success [ 70 ]. Providing mentorship within an individual department, as well as support for participating in external mentorship and career development programs, can help create sponsorship opportunities that eventually influence career advancement [ 41 ]. Many professional societies such as IDSA provide mentorship opportunities, and these can be enhanced by encouraging more sponsorship of junior clinicians for opportunities such as podium lectures, moderating at conferences, writing editorials, or committee positions.

In the years since the IAT was first described, researchers have published countless data on the impact of unconscious bias. Fortunately, explicit and implicit attitudes toward many disenfranchised groups of people have regressed to a more neutral position over time [ 71 ], but this does not mean that unconscious bias has disappeared. Just as healthcare providers are required to stay up to date on medical techniques and procedures to best serve their patients, we propose that trainings involving the social aspects of medicine be treated similarly. Cultural humility is characterized by lifelong learning and is a key aspect of a successful provider-patient relationship. Thus, it is imperative that healthcare organizations and professional medical societies such as IDSA continually provide healthcare professionals with learning opportunities to enhance their interactions with individuals different from themselves. Effectively addressing unconscious bias and subsequent disparities in IDSA will need comprehensive, multifaceted, and evidence-based interventions ( Figure 5 ).

Unconscious bias highlights.

IDSA has demonstrated a commitment to diversifying its society leadership by commissioning the Gender Disparities Task Force and the Inclusion, Diversity, Access & Equity Task Force, reconfiguring existing committees, developing new committees (eg, the Leadership Development Committee), and creating new opportunities, such as the IDSA Leadership Institute. While these are important and impactful actions, we propose the following additional steps to address the role of unconscious bias in various settings. First, develop an IDSA-sponsored climate survey to assess perceptions of inclusion and belonging within the Society, and repeat this climate assessment after implementing bias reduction strategies. Second, provide IDSA-sponsored education/training on unconscious bias reduction strategies and cultural humility to academic infectious disease divisions and fellowship programs to support the recruitment and retention of a diverse infectious diseases physician workforce. Third, develop benchmarks for excellence in infectious diseases divisions and fellowship training programs to evaluate these bias reduction strategies. Fourth, provide education/training on unconscious bias–reduction strategies and cultural humility to leadership and membership within IDSA. Specifically, the board of directors, the Leadership Development Committee, the Awards Committee, and others involved in electing, nominating, or honoring members should consider including incorporating the IAT and bias-reduction education for their committee members. After implementing such strategies, IDSA should reevaluate metrics of awardees, committee chairs, and leadership to determine whether these strategies made an impact. Fifth, cultivate existing mentorship programs within IDSA, with the added focus of intentional mentoring and sponsorship of groups traditionally underrepresented in leadership. Sixth, commit to consistent review and revision of infectious diseases recruitment messaging, ensuring that materials and media counter harmful stereotypes and represent true diversity. Seventh, collect, review, and publish metrics of diversity in all facets of the membership, including IDWeek speaker demographic characteristics, IDSA journal editor/reviewers, guideline authorship, and committee membership, with intentional response strategies to change these demographic characteristics to a more diverse distribution. Eighth, be transparent about reporting of metrics, with clear accountability and flexibility to adjust initiatives based on results.

Although there are numerous data describing the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare delivery, clinician-patient interactions, and patient outcomes, discussion of these aspects is out of the scope of this article, which focuses on the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare professionals. Additionally, the majority of data on unconscious bias presented in this article relates to general academic training and career development, as data in the infectious diseases practice community is limited. This represents an area of need for evaluation within the specialty of infectious diseases, since a vast majority of members are in clinical practice and may experience bias in varying degrees. While it is important to support trainees who may experience unconscious bias, it is also critical to provide support for infectious diseases clinicians further along in their careers, as a means to maintain retention in the specialty. Finally, some individuals may prefer person-first language, while others may prefer identity-first language when referring to disabilities. We consistently used person-first language throughout this manuscript based on the recommendation by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention ( https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/pdf/disabilityposter_photos.pdf ).

Supplement sponsorship . This supplement is sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Acknowledgments . We thank Drs Molly Carnes, Ranna Parekh, and Arghavan Salles, as well as Lena Tenney, for critical review of this manuscript before publication; Mr Chris Busky, for providing written communications about the demographic characteristics of IDSA membership and leadership; and Catherine Hiller, for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

J. R. M. wrote first draft and subsequent revisions; D. S. and R. V. contributed to the first draft and subsequent revisions; S. K. contributed to the first draft and subsequent revisions; Y. A. M. contributed to subsequent revisions; and all authors reviewed a final version of the work before submission.

Potential conflicts of interest . J. R. M. and D. S. are members of the IDSA Inclusion, Diversity, Access & Equity Task Force. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Institutional and Policy-Level Strategies for Increasing the Diversity of the U.S. Healthcare Workforce . In the nation’s compelling interest: ensuring diversity in the health-care workforce . Smedley BD , Stith Butler A , Bristow LR , eds. Washington, DC : National Academies Press (US) , 2004 .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

American College of Physicians . Racial and ethnic disparities in health care, updated 2010 . https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/advocacy/current_policy_papers/assets/racial_disparities.pdf . Accessed 25 January 2019 .

Association of American Medical Colleges . Underrepresented in medicine definition . https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/urm/ . Accessed 19 January 2019 .

United States Census Bureau . US Census Bureau QuickFacts . https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US# . Accessed 2 January 2019 .

Newport F. In U.S., estimate of LGBT population rises to 4.5% . https://news.gallup.com/poll/234863/estimate-lgbt-population-rises.aspx . Accessed 25 January 2019 .

Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) . AAMC facts & figures 2016; diversity in medical education . http://www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures2016.org/index.html . Accessed 25 January 2019 .

Meeks LM , Herzer KR . Prevalence of self-disclosed disability among medical students in US allopathic medical schools . JAMA 2016 ; 316 : 2271 – 2 .

Association of American Medical Colleges . U.S. medical school applications and matriculants by school, state of legal residence, and sex, 2018–2019 . https://www.aamc.org/download/321442/data/factstablea1.pdf . Accessed 4 January 2019 .

Boiko JR , Anderson AJM , Gordon RA . Representation of women among academic grand rounds speakers . JAMA Intern Med 2017 ; 177 : 722 – 4 .

Carnes M , Bartels CM , Kaatz A , Kolehmainen C . Why is John more likely to become department chair than Jennifer? Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2015 ; 126 : 197 – 214 .

Gerull KM , Loe M , Seiler K , McAllister J , Salles A . Assessing gender bias in qualitative evaluations of surgical residents . Am J Surg 2019 ; 217 : 306 – 13 .

FitzGerald C , Hurst S . Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review . BMC Med Ethics 2017 ; 18 .

Staats C , Dandar V , St Cloud T , Wright R . How the prejudices we don’t know we have affect medical education, medical careers, and patient health . In: Darcy Lewis and Emily Paulsen, eds. Proceedings of the 2014 diversity and inclusion innovation forum: unconscious bias in academic medicine . Association of American Medical Colleges . Association of American Medical Colleges and the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at The Ohio State University, USA 2017;1–93.

Staats C , Patton C. State of the science: implicit bias review: the Ohio State University Kirwan Instiute for the study of race and ethnicity . OH : The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at The Ohio State University , 2013 ; 1 – 102 .

Institute of Medicine . The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: building a foundation for better understanding . Washington, DC : The National Academies Press , 2011 .

Gonzales G , Przedworski J , Henning-Smith C . Comparison of health and health risk factors between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in the united states: results from the national health interview survey . JAMA Intern Med 2016 ; 176 : 1344 – 51 .

Valdiserri RO , Holtgrave DR , Poteat TC , Beyrer C . Unraveling health disparities among sexual and gender minorities: a commentary on the persistent impact of stigma . J Homosex 2019 ; 66 : 571 – 89 .

Trotman R , Kim AI , MacIntyre AT , Ritter JT , Malani AN . 2017 infectious diseases society of america physician compensation survey: results and analysis . Open Forum Infect Dis 2018 ; 5 : ofy309 .

Marcelin JR , Bares SH , Fadul N . Improved infectious diseases physician compensation but continued disparities for women and underrepresented minorities . Open Forum Infect Dis 2019 ; 6 : ofz042 .

Banaji MR , Greenwald AG. Blindspot: hidden biases of good people . 1st ed. USA : Delacorte Press , 2013 .

Francis CK . Medical ethos and social responsibility in clinical medicine . J Urban Health 2001 ; 78 : 29 – 45 .

Teal CR , Gill AC , Green AR , Crandall S . Helping medical learners recognise and manage unconscious bias toward certain patient groups . Med Educ 2012 ; 46 : 80 – 8 .

Dehon E , Weiss N , Jones J , Faulconer W , Hinton E , Sterling S . A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making . Acad Emerg Med 2017 ; 24 : 895 – 904 .

Greenwald AG , McGhee DE , Schwartz JL . Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test . J Pers Soc Psychol 1998 ; 74 : 1464 – 80 .

Blanton H , Jaccard J , Klick J , Mellers B , Mitchell G , Tetlock PE . Strong claims and weak evidence: reassessing the predictive validity of the IAT . J Appl Psychol 2009 ; 94 : 567 – 82 ; discussion 583–603.

McConnell AR , Leibold JM. Weak criticisms and selective evidence: Reply to Blanton et al . (2009) . J Appl Psychol , 2009;94, 583-9. doi:10.1037/a0014649

Blanton H , Jaccard J , Strauts E , Mitchell G , Tetlock PE . Toward a meaningful metric of implicit prejudice . J Appl Psychol 2015 ; 100 : 1468 – 81 .

Capers Q 4th , Clinchot D , McDougle L , Greenwald AG . Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions . Acad Med 2017 ; 92 : 365 – 9 .

Haider AH , Sexton J , Sriram N , et al. Association of unconscious race and social class bias with vignette-based clinical assessments by medical students . JAMA 2011 ; 306 : 942 – 51 .

Osseo-Asare A , Balasuriya L , Huot SJ , et al. Minority resident physicians’ views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace . JAMA Netw Open 2018 ; 1 : e182723 .

Riese A , Rappaport L , Alverson B , Park S , Rockney RM . Clinical performance evaluations of third-year medical students and association with student and evaluator gender . Acad Med 2017 ; 92 : 835 – 40 .

Files JA , Mayer AP , Ko MG , et al. Speaker introductions at internal medicine grand rounds: forms of address reveal gender bias . J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017 ; 26 : 413 – 9 .

Mehta S , Rose L , Cook D , Herridge M , Owais S , Metaxa V . The speaker gender gap at critical care conferences . Crit Care Med 2018 ; 46 : 991 – 996 .

Lee KP , Kelz RR , Dubé B , Morris JB . Attitude and perceptions of the other underrepresented minority in surgery . J Surg Educ 2014 ; 71 : e47 – 52 .

Marlin R , Kadakia A , Ethridge B , Mathews WC . Physician attitudes toward homosexuality and HIV: the PATHH-III survey . LGBT Health 2018 ; 5 : 431 – 42 .

Sánchez NF , Rankin S , Callahan E , et al. LGBT trainee and health professional perspectives on academic careers–facilitators and challenges . LGBT Health 2015 ; 2 : 346 – 56 .

Phelan SM , Burke SE , Hardeman RR , et al. Medical school factors associated with changes in implicit and explicit bias against gay and lesbian people among 3492 graduating medical students . J Gen Intern Med 2017 ; 32 : 1193 – 201 .

Zazove P , Case B , Moreland C , et al. U.S. medical schools’ compliance with the americans with disabilities act: findings from a national study . Acad Med 2016 ; 91 : 979 – 86 .

Seidel E , Crowe S . The state of disability awareness in american medical schools . Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2017 ; 96 : 673 – 6 .

Meeks LM , Herzer K , Jain NR . Removing barriers and facilitating access: increasing the number of physicians with disabilities . Acad Med 2018 ; 93 : 540 – 3 .

DiBrito SR , Lopez CM , Jones C , Mathur A . Reducing implicit bias: association of women surgeons #HeForShe task force best practice recommendations . J Am Coll Surg 2019 ; 228 : 303 – 9 .

South-Paul JE , Roth L , Davis PK , et al. Building diversity in a complex academic health center . Acad Med 2013 ; 88 : 1259 – 64 .

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . Common program requirements (fellowship) . https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRFellowship2019.pdf . Accessed 19 January 2019 .

Devine PG , Forscher PS , Austin AJ , Cox WT . Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: a prejudice habit-breaking intervention . J Exp Soc Psychol 2012 ; 48 : 1267 – 78 .

Carnes M , Fine E , Sheridan J . Promises and pitfalls of diversity statements: proceed with caution . Acad Med 2019 ; 94 : 20 – 4 .

Smith DG . Building institutional capacity for diversity and inclusion in academic medicine . Acad Med 2012 ; 87 : 1511 – 5 .

Helitzer DL , Newbill SL , Cardinali G , Morahan PS , Chang S , Magrane D . Changing the culture of academic medicine: critical mass or critical actors? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017 ; 26 : 540 – 8 .

Girod S , Fassiotto M , Grewal D , et al. Reducing implicit gender leadership bias in academic medicine with an educational intervention . Acad Med 2016 ; 91 : 1143 – 50 .

Capers Q , McDougle L , Clinchot DM . Strategies for achieving diversity through medical school admissions . J Health Care Poor Underserved 2018 ; 29 : 9 – 18 .

Person SD , Jordan CG , Allison JJ , et al. Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine: the diversity engagement survey . Acad Med 2015 ; 90 : 1675 – 83 .

Greenwald AG , Banaji MR , Nosek BA . Statistically small effects of the implicit association test can have societally large effects . J Pers Soc Psychol 2015 ; 108 : 553 – 61 .

Oswald FL , Mitchell G , Blanton H , Jaccard J , Tetlock PE . Predicting ethnic and racial discrimination: a meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies . J Pers Soc Psychol 2013 ; 105 : 171 – 92 .

Oswald FL , Mitchell G , Blanton H , Jaccard J , Tetlock PE . Using the IAT to predict ethnic and racial discrimination: small effect sizes of unknown societal significance . J Pers Soc Psychol 2015 ; 108 : 562 – 71 .

Duguid MM , Thomas-Hunt MC . Condoning stereotyping? How awareness of stereotyping prevalence impacts expression of stereotypes . J Appl Psychol 2015 ; 100 : 343 – 59 .

Dasgupta N . Chapter five—implicit attitudes and beliefs adapt to situations: a decade of research on the malleability of implicit prejudice, stereotypes, and the self-concept . In: Devine P , Plant A , eds. Advances in experimental social psychology . Vol. 47 . USA: Academic Press, 2013 : 233 – 79 .

Phillips NA , Tannan SC , Kalliainen LK . Understanding and overcoming implicit gender bias in plastic surgery . Plast Reconstr Surg 2016 ; 138 : 1111 – 6 .

Nelson SC , Prasad S , Hackman HW . Training providers on issues of race and racism improve health care equity . Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015 ; 62 : 915 – 7 .

Burns MD , Monteith MJ , Parker LR . Training away bias: the differential effects of counterstereotype training and self-regulation on stereotype activation and application . J Exp Soc Psychol 2017 ; 73 : 97 – 110 .

Tenney L. Being an active bystander: strategies for challenging the emergence of bias. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity , 2017 .

Harrison G , Turner R . Being a ‘culturally competent’ social worker: making sense of a murky concept in practice . Br J Soc Work 2010 ; 41 : 333 – 350 .

Juarez JA , Marvel K , Brezinski KL , Glazner C , Towbin MM , Lawton S . Bridging the gap: a curriculum to teach residents cultural humility . Fam Med 2006 ; 38 : 97 – 102 .

Chang ES , Simon M , Dong X . Integrating cultural humility into health care professional education and training . Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2012 ; 17 : 269 – 78 .

Kumagai AK , Lypson ML . Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education . Acad Med 2009 ; 84 : 782 – 7 .

Beauchamp GA , McGregor AJ , Choo EK , Safdar B , Rayl Greenberg M . Incorporating sex and gender into culturally competent simulation in medical education . J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019 . doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.7271

van Ryn M , Hardeman R , Phelan SM , et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: a medical student CHANGES study report . J Gen Intern Med 2015 ; 30 : 1748 – 56 .

Hafferty FW . Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum . Acad Med 1998 ; 73 : 403 – 7 .

Neve H , Collett T . Empowering students with the hidden curriculum . Clin Teach 2018 ; 15 : 494 – 9 .

Fallin-Bennett K . Implicit bias against sexual minorities in medicine: cycles of professional influence and the role of the hidden curriculum . Acad Med 2015 ; 90 : 549 – 52 .

Liebschutz JM , Darko GO , Finley EP , Cawse JM , Bharel M , Orlander JD . In the minority: black physicians in residency and their experiences . J Natl Med Assoc 2006 ; 98 : 1441 – 8 .

Gandhi M , Fernandez A , Stoff DM , et al. Development and implementation of a workshop to enhance the effectiveness of mentors working with diverse mentees in HIV research . AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014 ; 30 : 730 – 7 .

Charlesworth TES , Banaji MR . Patterns of implicit and explicit attitudes: I. Long-Term change and stability from 2007 to 2016 . Psychol Sci 2019 ; 30 : 174 – 92 .

Yeager KA , Bauer-Wu S . Cultural humility: essential foundation for clinical researchers . Appl Nurs Res 2013 ; 26 : 251 – 6 .

Sue DW , Capodilupo CM , Torino GC , et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice . Am Psychol 2007 ; 62 : 271 – 86 .

- bias (epidemiology)

- communicable diseases

- delivery of health care

- personnel selection

- cultural competence

- infectious diseases society of america

- mentorships

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| August 2019 | 509 |

| September 2019 | 589 |

| October 2019 | 1,410 |

| November 2019 | 2,042 |

| December 2019 | 1,411 |

| January 2020 | 2,310 |

| February 2020 | 2,600 |

| March 2020 | 2,346 |

| April 2020 | 3,582 |

| May 2020 | 1,716 |

| June 2020 | 4,194 |

| July 2020 | 3,754 |

| August 2020 | 4,157 |

| September 2020 | 5,002 |

| October 2020 | 5,731 |

| November 2020 | 5,337 |

| December 2020 | 4,038 |

| January 2021 | 4,439 |

| February 2021 | 5,264 |

| March 2021 | 7,110 |

| April 2021 | 6,594 |

| May 2021 | 5,651 |

| June 2021 | 4,077 |

| July 2021 | 3,769 |

| August 2021 | 4,415 |

| September 2021 | 6,403 |

| October 2021 | 6,028 |

| November 2021 | 5,996 |

| December 2021 | 3,551 |

| January 2022 | 4,581 |

| February 2022 | 5,716 |

| March 2022 | 7,015 |

| April 2022 | 6,583 |

| May 2022 | 5,686 |

| June 2022 | 3,767 |

| July 2022 | 4,020 |

| August 2022 | 3,778 |

| September 2022 | 4,958 |

| October 2022 | 6,260 |

| November 2022 | 6,488 |

| December 2022 | 3,963 |

| January 2023 | 4,203 |

| February 2023 | 5,460 |

| March 2023 | 6,441 |

| April 2023 | 6,362 |

| May 2023 | 5,624 |

| June 2023 | 3,688 |

| July 2023 | 4,267 |

| August 2023 | 4,484 |

| September 2023 | 5,618 |

| October 2023 | 5,793 |

| November 2023 | 5,414 |

| December 2023 | 3,800 |

| January 2024 | 4,855 |

| February 2024 | 4,375 |

| March 2024 | 5,673 |

| April 2024 | 5,649 |

| May 2024 | 5,069 |

| June 2024 | 2,952 |

| July 2024 | 2,798 |

| August 2024 | 2,871 |

Email alerts

More on this topic, related articles in pubmed, citing articles via, looking for your next opportunity.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1537-6613

- Print ISSN 0022-1899

- Copyright © 2024 Infectious Diseases Society of America

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Patient satisfaction and experience

Getty Images

What is implicit bias, how does it affect healthcare?

Healthcare leaders working toward health equity will need to recognize their own implicit biases to truly enhance patient care..

- Sara Heath, Executive Editor

Medicine's focus on racial health disparities and health equity has brought to the forefront another key concept in healthcare delivery and patient care: implicit bias.

Implicit bias, a phrase that is not unique to healthcare, refers to the unconscious prejudice individuals might feel about another thing, group, or person.

According to the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at the Ohio State University, implicit bias is involuntary, can refer to positive or negative attitudes and stereotypes, and can affect actions without an individual knowing it:

Also known as implicit social cognition, implicit bias refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner. These biases, which encompass both favorable and unfavorable assessments, are activated involuntarily and without an individual’s awareness or intentional control. Residing deep in the subconscious, these biases are different from known biases that individuals may choose to conceal for the purposes of social and/or political correctness. Rather, implicit biases are not accessible through introspection.

Implicit bias can be a factor in any aspect of our everyday lives: when we interact with colleagues, make new friends, or meet parents at our children’s schools. That means the interactions providers and medical workers have with patients are likewise not immune to implicit bias.

In 2015, a group of researchers conducted a literature review to understand the pervasiveness of and impacts of implicit bias. Through the review, the team was able to conclude at least moderate implicit bias in most medical providers. The Implicit Association Test, which measures implicit bias, detected about equal bias across Black, Latinx, and dark-skinned patients.

To be clear, implicit bias is unconscious, and most researchers investigating the subject assert that very few medical professionals maliciously seek to do harm to some of their patients.

But that 2015 review showed that implicit bias does have some consequences, not least of which are strained patient-provider relationships and clinical outcomes. This, like other clinical quality challenges, warrants a closer look from the medical community.

Below, PatientEngagementHIT will outline what implicit bias looks like in healthcare, how it can affect patient-provider communication and outcomes, and how the healthcare industry is beginning to recognize its own implicit biases.

What is implicit bias in healthcare?

In healthcare, implicit bias can shape the way medical providers interact with patients. Because everyone is susceptible to implicit bias, even clinicians, these unconscious preconceptions will naturally seep into patient-provider communication.

There is already some evidence indicating such. In September 2020, the Regenstrief Institute published data from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) suggesting that veterans accessing mental health treatment could sense some non-verbal cues that signaled implicit bias.

The survey of 85 Black veterans showed that most had good patient-provider relationships, but many expressed some issues that indicated race could play a role in their healthcare.

"They explained that structural characteristics such as the physical space of an institution project how welcoming an institution might be to minority patients, and that staff diversity, especially in position of power, reflects the facility's values and culture related to racial equity," the researchers reported.

The study went on to describe various subtle behaviors and microaggressions that indicated to patients that implicit biases could be tainting their healthcare experiences.

Since 2020, more studies have explored patient perceptions of implicit bias, with four in 10 patients telling a 2022 MITRE-Harris Poll Survey on Patient Experience that the perceive their providers as biased against them. Hispanic and Black patients were more likely to report this than any other demographic group.

But implicit bias is at play not just when it comes to race and ethnicity. A September 2022 Urban Institute/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation report showed that 17 percent of publicly insured people and 13 percent of uninsured people perceived implicit bias from their providers.

And nearly a third of people with disabilities said in a different Urban Institute/RWJF poll that they perceived unfair treatment in healthcare settings.

Meanwhile, a separate third of LGBT patients said they've had disrespectful healthcare experiences, indicating some bias on the part of their providers.

Again, most experts agree that most clinicians are committed to providing excellent medical care to all of their patients, regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, or ability to pay. But again, since nobody is immune to implicit bias, it is at play in many medical encounters.

What are the consequences of implicit bias in healthcare?

As with any interaction, implicit bias can have adverse effects on the patient experience. By damaging patient-provider interactions, implicit bias can adversely impact health outcomes.

In many situations, patients are able to pick up on a provider’s implicit bias, and patients often report a poor experience for that. A patient who picks up on a provider’s implicit bias naturally may feel less inclined to engage deeply with care.

Patients with similar experiences as the veteran from the Regenstrief study, for example, could be dissuaded from visiting a provider if they feel the provider treated them like an "angry, big Black man."

This kind of implicit discrimination has born itself out in many Black and Brown patients lacking trust in the medical institution and being reticent to engage with it.

Additionally, implicit bias could put a cap on how well a patient understands her own health or is invited to engage in her care. For example, some providers may limit the depth of shared decision-making or explanations of medical concepts because their implicit bias tells them a patient does not have the health literacy to fully engage with her care.

This, coupled with some implicit biases that tell providers a patient may not be able to afford specialty care, can decrease the odds a patient gets the depth of medical care she might need.

In December 2022, researchers from the University of Minnesota Medical School showed racial health disparities in treatment recommendation . Specifically, the team found that Black patients and other patients of color were less likely to be advised on primary brain tumor removal, which they said was likely a byproduct of implicit bias.

Another study from November 2023 showed that Black patients were modestly more likely to receive low-value care , or "services that provide little to no benefit in specific clinical scenarios yet have potential for harm," the researchers wrote in BMJ. That disparity is likewise potentially driven by implicit bias.

For example, limited patient trust among Black populations could be behind the slightly greater risk for low-value acute diagnostic tests, the researchers said. Because this population tends to report lower trust in medical providers, they may be more likely to agree to diagnostic testing because it is more reassuring than a provider’s assessment.

On the provider side, implicit or explicit biases could also impact communication, which in turn could result in misunderstandings of patient care needs and preferences.

Implicit bias is still a sneaky specter infecting healthcare interactions and contributing to the racial health disparities being seen today. Organizations working to close health disparities must incorporate implicit bias and cultural competency training into their practice.

Addressing implicit bias

Eliminating implicit bias is a challenging task because, as the experts at OSU's Kirwan Institute said, one's own implicit bias is not something most people are aware of. Implicit bias is not purposeful -- purposeful discrimination is referred to as explicit.

But a strong education campaign can be a good first step to helping clinicians pick up on their own biases.

Currently, there's no standardized course for implicit bias training in hospitals and health systems. But as more governing bodies begin to require implicit bias training for things like licensure, organizations are working to build out their own curricula. Implicit bias training courses need to incorporate the existing evidence base, center key stakeholders, and hold space for participants' humanity .

In short, implicit bias training needs to be informative and actionable and avoid judgment. Organizations can potentially increase participation numbers by making it easy to attend implicit bias training, so it may be helpful to consider holding training sessions over Zoom and at various times and days to accommodate staff schedules.

Notably, implicit bias training is not just for clinicians, experts agree. Training that includes administrative, front office, and other staff like environmental services helps fortify and organizational culture of inclusion and equity.

Implicit bias training is essential, but looking into the distant future, many experts have said increasing the diversity of the medical workforce will be a key step in mitigating implicit bias. Although anyone of any demographic has implicit biases, having a workforce reflective of the community it serves may lessen the damage those biases have.

Indeed, data has shown that a diverse medical workforce can improve outcomes because it increases the odds of racial concordance, something that’s been proven to enrich the patient-provider relationship and some outcomes.

Right now, a diverse medical workforce is out of reach. Part of the issue is lack of diversity in medical education; hospitals and health systems can only hire as diverse a staff as they have applicants. Some higher education institutions are cultivating a more diverse medical school applicant pool by hosting elementary, middle, and high school STEM exposure course. Some medical schools are also beginning to offer tuition-free education.

But healthcare can only maintain a diverse medical workforce if its institutions remain inviting to all. Building out a peer-to-peer culture of belonging will be critical in this area.

The process of identifying and acknowledging implicit bias in healthcare is only in its infancy. But as more organizations commit to ending racial health disparities and working toward health equity, this will be an important step toward that end.

Sara Heath has been covering news related to patient engagement and health equity since 2015.

- What is the Difference Between Health Disparities, Equity?

Dig Deeper on Patient satisfaction and experience

How Do Income & SDOH Affect Cardiovascular Healthcare?

Discrimination in Pediatrics Raises Questions About Weathering

Low Trust, Bias Taint Shared Decision-Making for Black Patients

How U-M Health Got 27K Staff Members in Implicit Bias Training

A 'JAMA Internal Medicine' study found that team-based documentation increased visit volume and reduced physician EHR ...

Ambient AI technology is helping Ochsner Health improve patient-provider relationships by allowing clinicians to spend ...

Epic's goal to bring customers live on TEFCA by the end of 2025 complements Carequality's plan to align with TEFCA as the ...

Taking steps to recognize and correct unconscious assumptions toward groups can promote health equity.

JENNIFER EDGOOSE, MD, MPH, MICHELLE QUIOGUE, MD, FAAFP, AND KARTIK SIDHAR, MD

Fam Pract Manag. 2019;26(4):29-33

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

Jamie is a 38-year-old woman and the attending physician on a busy inpatient teaching service. On rounds, she notices several patients tending to look at the male medical student when asking a question and seeming to disregard her. Alex is a 55-year-old black man who has a history of diabetic polyneuropathy with significant neuropathic pain. His last A1C was 7.8. He reports worsening lower extremity pain and is frustrated that, despite his bringing this up repeatedly to different clinicians, no one has addressed it. Alex has been on gabapentin 100 mg before bed for 18 months without change, and his physicians haven't increased or changed his medication to help with pain relief.

Alisha is a 27-year-old Asian family medicine resident who overhears labor and delivery nurses and the attending complain that Indian women are resistant to cervical exams.

These scenarios reflect the unconscious assumptions that pervade our everyday lives, not only as practicing clinicians but also as private citizens. Some of Jamie's patients assume the male member of the team is the attending physician. Alex's physicians perceive him to be a “drug-seeking” patient and miss opportunities to improve his care. Alisha is exposed to stereotypes about a particular ethnic group.

Although assumptions like these may not be directly ill-intentioned, they can have serious consequences. In medical practice, these unconscious beliefs and stereotypes influence medical decision-making. In the classic Institute of Medicine report “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care,” the authors concluded that “bias, stereotyping, and clinical uncertainty on the part of health care providers may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in health care” often despite providers' best intentions. 1 For example, studies show that discrimination and bias at both the individual and institutional levels contribute to shocking disparities for African-American patients in terms of receiving certain procedures less often or experiencing much higher infant mortality rates when compared with non-Hispanic whites. 2 , 3 As racial and ethnic diversity increases across our nation, it is imperative that we as physicians intentionally confront and find ways to mitigate our biases.

Implicit bias is the unconscious collection of stereotypes and attitudes that we develop toward certain groups of people, which can affect our patient relationships and care decisions.

You can overcome implicit bias by first discovering your blind spots and then actively working to dismiss stereotypes and attitudes that affect your interactions.

While individual action is helpful, organizations and institutions must also work to eliminate systemic problems.

DEFINING AND REDUCING IMPLICIT BIAS

For the last 30 years, science has demonstrated that automatic cognitive processes shape human behavior, beliefs, and attitudes. Implicit or unconscious bias derives from our ability to rapidly find patterns in small bits of information. Some of these patterns emerge from positive or negative attitudes and stereotypes that we develop about certain groups of people and form outside our own consciousness from a very young age. Although such cognitive processes help us efficiently sort and filter our perceptions, these reflexive biases also promote inconsistent decision making and, at worst, systematic errors in judgment.

Cognitive processes lead us to associate unconscious attributes with social identities. The literature explores how this influences our views on race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation, and weight, and studies show many people are biased in favor of people who are white, young, male, heterosexual, and thin. 4 Unconsciously, we not only learn to associate certain attributes with certain social groupings (e.g., men with strength, women with nurturing) but also develop preferential ranking of such groups (e.g., preference for whites over blacks). This unconscious grouping and ranking takes root early in development and is shaped by many outside factors such as media messages, institutional policies, and family beliefs. Studies show that health care professionals have the same level of implicit bias as the general population and that higher levels are associated with lower quality care. 5 Providers with higher levels of bias are more likely to demonstrate unequal treatment recommendations, disparities in pain management, and even lack of empathy toward minority patients. 6 In addition, stressful, time-pressured, and overloaded clinical practices can actually exacerbate unconscious negative attitudes. Although the potential impact of our biases can feel overwhelming, research demonstrates that these biases are malleable and can be overcome by conscious mitigation strategies. 7

We recommend three overarching strategies to mitigate implicit bias – educate, expose, and approach – which we will discuss in greater detail. We have further broken down these strategies into eight evidence-based tactics you can incorporate into any quality improvement project, diagnostic dilemma, or new patient encounter. Together, these eight tactics spell out the mnemonic IMPLICIT. (See “ Strategies to combat our implicit biases .”)

| Explore and identify your own implicit biases by taking implicit association tests or through other means. | ||

| Practice ways to reduce stress and increase mindfulness, such as meditation, yoga, or focused breathing. | “ ” | |

| Consider experiences from the point of view of the person being stereotyped. This can involve consuming media about those experiences, such as books or videos, and directly interacting with people from that group. | “ ” | |

| Pause and reflect on your potential biases before interacting with people of certain groups to reduce reflexive reactions. This could include thinking about positive examples of that stereotyped group, such as celebrities or personal friends. | “ ” | |

| Evaluate people based on their personal characteristics rather than those affiliated with their group. This could include connecting over shared interests or backgrounds. | “ ” | |

| Embrace evidence-based statements that reduce implicit bias, such as welcoming and embracing multiculturalism. | “ ” | |

| Promote procedural change at the organizational level that moves toward a socially accountable health care system with the goal of health equity. | ||

| Practice cultural humility, a lifelong process of critical self-reflection to readdress the power imbalances of the clinician-patient relationship. | “ ” |

When we fail to learn about our blind spots, we miss opportunities to avoid harm. Educating ourselves about the reflexive cognitive processes that unconsciously affect our clinical decisions is the first step. The following tactics can help:

Introspection . It is not enough to just acknowledge that implicit bias exists. As clinicians, we must directly confront and explore our own personal implicit biases. As the writer Anais Nin is often credited with saying, “We don't see things as they are, we see them as we are.” To shed light on your potential blind spots and unconscious “sorting protocols,” we encourage you to take one or more implicit association tests . Discovering a moderate to strong bias in favor of or against certain social identities can help you begin this critical step in self exploration and understanding. 8 You can also complete this activity with your clinic staff and fellow physicians to uncover implicit biases as a group and set the stage for addressing them. For instance, many of us may be surprised to learn after taking an implicit association test that we follow the typical bias of associating males with science — an awareness that may explain why the patient in our first case example addressed questions to the male medical student instead of the female attending.

Mindfulness .It should come as no surprise that we are more likely to use cognitive shortcuts inappropriately when we are under pressure. Evidence suggests that increasing mindfulness improves our coping ability and modifies biological reactions that influence attention, emotional regulation, and habit formation. 9 There are many ways to increase mindfulness, including meditation, yoga, or listening to inspirational texts. In one study, individuals who listened to a 10-minute meditative audiotape that focused them and made them more aware of their sensations and thoughts in a nonjudgmental way caused them to rely less on instinct and show less implicit bias against black people and the aged. 10