Dr M clarifies ancestry: Not Indian Muslim, but likely of Indian descent like many Penang Malay Muslims

Ebit Lew sexting trial: Woman claims was coerced to expose breasts during video call, took screenshot

Another sinkhole appears at Jln Masjid India, mere 50m away from collapse which swallowed woman (VIDEO)

OECD moots gradual return of GST for Malaysia to strengthen its revenue source, Rafizi says many baskets better

In prison since August 2022, why is Umno so determined to free Najib now?

Camp operator, saddled with RM14m loss, fails court bid against govt for axing National Service

Putrajaya takes Terengganu female diving medallists under its wings after furore raised by PAS-led state govt

‘Mother was everything to me’: Son who regrets victim never saw the tattoo with her name before KL sinkhole tragedy

Rafizi announces govt efficiency commitment law to improve doing business in Malaysia

Two Johor cops seriously injured in landslide during bomb detonation exercise

SAR operation for missing Indian woman in Jalan Masjid India sinkhole halted yesterday due to heavy rain, to resume today

Where have all the shoppers gone? Onto social media, nearly everyone, says TikTok

The works of Van Gogh, Monet, Mozart and Beethoven come alive in an immersive, multisensory experience next month in KL

Singapore courts jails Malaysian 14 months for bribing zoo official RM474,000 in corrupt contractor scheme

IGP: Millah Abraham cult being monitored, deviant teachings under control

Malaysia’s election process explained.

KUALA LUMPUR, March 23 — Here is a quick breakdown of Malaysia’s election process based on the first-past-the-post system in a parliamentary democracy.

The 14th general election must be held by August 24 this year.

1. Parliament is dissolved

The ball starts rolling the day Parliament is dissolved, which has yet to happen for the14th general election.

This sometimes happens once every four years, but a full term is five years.

The Yang Di-Pertuan Agong officially dissolves Parliament upon advice from the prime minister, who is currently Datuk Seri Najib Razak.

When Parliament is dissolved, the election is to be held within 60 days .

2. When will this happen?

The 13th Parliament automatically dissolves on June 24 , but the prime minister can call for the dissolution anytime before then.

3. What or who are people voting for?

Take a deep breath.

Malaysians vote for who will sit in the Lower House of Parliament known as the Dewan Rakyat, comprising 222 seats. This is a federal level vote.

The candidates for the 222 seats are divided into respective constituencies. Or, in simpler terms, there are 222 constituencies and one seat to represent each area in Parliament.

A constituency is an area within a state. Each state has a various number of federal and state constituencies. Selangor has 22 federal constituencies, for example, while Penang has 13.

But there is also a second vote which generally coincides with the general election. The people will vote for 587 state legislative assembly seats, or “Ahli Dewan Undangan Negeri”. These assemblymen are elected to form the state government. This is a state level vote.

Voters in the federal territories of Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya and Labuan, however, only have one vote — for their Member of Parliament — as there are no local council elections.

In the 14th general election, Sarawakians will only cast their ballots for their MPs as their state election was already held in 2016.

It is possible for candidates to run as both MPs and state assemblymen.

Candidates will either be nominees of political parties or running as independents.

Following the Westminster system, there is also an Upper House in Parliament known as Dewan Negara. The people do not vote on these 70 seats occupied by senators.

Senators are appointed by Yang Di-Pertuan Agong upon advice from the prime minister. Each state assembly can appoint two senators to the Dewan Negara.

4. Who oversees the election?

A seven-member Election Commission (EC) appointed by the King upon advice from the prime minister.

Their first call to action is when Parliament is dissolved. The EC issues a writ to returning officers to hold elections in their respective constituencies. A returning officer is someone who represents each constituency on behalf of the EC.

Keeping up? Let’s move on.

5. Nominations begin

And the excitement commences.

Candidates must first deposit RM10,000 to contest a parliamentary seat and RM5,000 for a seat at state level. They will lose their deposit if they fail to get at least ⅛ of the total number of votes cast.

Candidates are also required to pay a campaign materials deposit of RM5,000 for a Parliament seat and RM3,000 for a state seat. The deposit will be returned once all of the candidate’s campaign materials are cleaned up within two weeks of polling.

Nomination papers are submitted to the returning officer for each constituency.

The returning officer will declare shortly after who the candidates are, trusting they are fit to stand for election.

There are three premises which determine if a person can run for election — they must be Malaysian citizens of at least 21 years of age, of sound mental capacity and not bankrupt.

6. Then some campaigning

This will begin after nominations are decided and end at midnight before polling day.

Campaigns will include tours around kampungs and holding “ceramah”, or rallies.

Rules of the campaign — no use of improper materials, no illegal forums and no going above campaign spending limits, which are RM200,000 for federal level and RM100,000 for state level votes.

7. Followed by polling

The voting day. Polling lasts for one day.

Registered voters cast their poll for both parliamentary and state level candidates.

There is no date set for voting in the 14th general election as Parliament is yet to be dissolved.

8. Count the ballots

Ballots are tallied by EC officers.

9. Declaration

Returning officer to each constituency will announce which candidate is the winner.

For each seat declared, the numbers begin to add up for which party will rule in Parliament.

10. How is the winner decided?

Using a first-past-the-post system, adopted from Britain. The winner is the candidate who gets the most number of votes out of the total ballots cast. For example, if 100 votes were cast in a constituency and Candidate A received 40 votes, while Candidate B and Candidate C each received 30 votes, Candidate A is the winner despite not getting support from majority of voters.

A government is formed when a party or coalition secures more than half the seats in Parliament.

With 222 seats on offer, 112 is the magic number needed to form a parliamentary majority and the government.

You May Also Like

Related articles.

Health Ministry: No suspected mpox cases detected among 2.64 million travellers

SAR team re-enters Indah Water pump station in search for KL sinkhole victim

DPM Zahid to undertake three-day official visit to Timor Leste

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal of Constitutional Law

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. liberal democracy on the rise or decline, 3. major constitutional developments, 4. looking ahead to 2018.

- < Previous

Malaysia: The state of liberal democracy

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Andrew James Harding, Jaclyn L Neo, Dian A H Shah, Wilson Tay Tze Vern, Malaysia: The state of liberal democracy, International Journal of Constitutional Law , Volume 16, Issue 2, April 2018, Pages 625–634, https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moy042

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Malaysia approaches its fourteenth general election, which must be held by August 24, 2018, at the latest. This election will determine whether the ruling BN (Barisan Nasional) coalition returns to power despite the corruption scandal surrounding 1Malaysia Development Berhad that has attracted worldwide attention, 1 and recaptures the two-thirds majority in the federal parliament which will enable it to amend the Federal Constitution. No party has enjoyed such a majority since 2008; hence no constitutional amendment has taken place since then. Against this backdrop, the constituency-redelineation exercise of the Election Commission of Malaysia (EC), which started in September 2016, has been particularly contentious. Opposition parties and their supporters have alleged, claiming extensive gerrymandering, that this redelineation gives further advantages to the ruling coalition (which the EC strenuously denies), and the exercise itself has been held up by extensive litigation across the country stretching throughout 2017.

Legal and political developments with a religious aspect continued to be particularly emotive in this country where Islam is constitutionally enshrined as “the religion of the Federation” 2 but which is also home to a sizable non-Muslim minority of around 39 percent of the population. 3 These developments continue to test the dividing line between the two legal systems that co-exist in Malaysia’s pluralist legal sphere—one centered around the regular or “civil” courts and the other around the religious or Syariah courts which exercise jurisdiction over Muslims in Malaysia. As exemplified by the bin Abdulla h case discussed further below, also at issue is the extent to which Islamic religious precepts and institutions can influence secular administrative bodies wielding governmental power in Malaysia.

Liberal democracy could be said to remain in a relatively precarious position in Malaysia. While opposition politicians, civil society leaders, and the alternative media have generally been able to continue highlighting scandals such as that of state investment vehicle 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), and to organize public rallies such as the “Love Malaysia, End Kleptocracy” event on October 14, 2017, criminal charges have been pressed against several prominent opposition leaders that could disqualify them from politics. This year, a Committee of the Inter-Parliamentary Union adopted a Decision expressing concern over the use of criminal investigations and legal action against nineteen opposition parliamentarians in Malaysia. 4

The abolition of the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking, passed by parliament in December represents a tentative step forward for the cause of liberal democracy. Amendments to the Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 now enable courts to impose a sentence of life imprisonment plus whipping for that offense in lieu of the mandatory death penalty if it finds that the accused “has assisted an enforcement agency in disrupting drug trafficking activities within or outside Malaysia.” 5

It is encouraging that the government, in response to public pressure, removed a provision in the original bill that would have given Malaysia’s Attorney-General, as the Public Prosecutor, the sole discretion to certify whether or not the accused person had rendered such assistance to an enforcement agency. In the amendment’s final version, that discretion now rests with the courts. Thus the reform—originally modeled on Singapore’s 2013 amendment to its penalty for drug trafficking—has gone one step further and achieved an even more complete separation of powers by giving to the judicial branch, rather than the public prosecutor, full control over the decision whether a death sentence should be imposed. 6 This reform enhances the content and significance of the constitutional guarantee in article 5(1) that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty, save in accordance with law.

On the other hand, speech and activity with religious aspects have come under increasing control and suppression in Malaysia. Many publications touching upon Islam have been banned on the basis that they could cause “confusion,” “anxiety,” “anger,” or even “division” among the Muslim community, which the government considers to be public order concerns. 7 When faced with challenges to such bans, the courts have tended to adopt a deferential approach, affirming the government’s decisions.

Furthermore, religious freedom—especially for Muslims—continues to be highly restricted in Malaysia. In several cases that came up for consideration in 2017, the courts affirmed existing doctrine that the question of whether a person was a Muslim or not is a matter under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Syariah Court. This means that even where a person had publicly renounced Islam (e.g., by way of a statutory declaration), he or she is still bound by Islamic law, particularly its rules on conversion out of Islam. A person can only convert out of Islam if the Syariah courts “certify” his or her conversion, which in the current constitutional context remains highly unlikely. 8

These developments could be seen as lack of due regard for the freedom of speech as well as freedom of religion, which is enshrined in articles 10(1) and 11 of the Federal Constitution, respectively.

3.1. Constituency boundaries litigation

The Malaysian courts continued to be the main avenue for opposition parties and concerned citizens to mount challenges against the EC’s redelineation exercise. The EC had, in September 2016, published notice of its proposed recommendations for the redelineation of federal and state constituencies in Peninsular Malaysia, as is mandated every eight years or more under article 113(2) of the Federal Constitution. These recommendations are thereafter to be reported to the Prime Minister, who then tables it before the House of Representatives (the lower house of parliament) alongside a draft order giving effect to the recommendations, with or without modifications. Upon the draft order being approved by not less than one-half of the total members of the House, it is submitted to the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (the King) who makes an order in terms of the draft, completing the redelineation. However, at the notice stage, any state government or local authority whose area is affected by the recommendation, or any body of 100 or more persons in an affected constituency, may object, whereupon the EC shall hold local enquiries in respect of these constituencies and may modify its recommendations if necessary.

The Selangor State Government—controlled by political parties in opposition at the federal level—sought judicial review against the EC recommendations in Selangor, highlighting that they resulted in malapportioned, gerrymandered constituencies, were based on incomplete and defective electoral rolls, and lacked particulars necessary for voters to make meaningful representations in response. 9 After a prolonged hearing, the High Court declined to intervene on the basis that the EC’s recommendations and its discretion to take into account the principles governing redelineation as provided for in the Thirteenth Schedule of the Federal Constitution were non-justiciable since the final decision on the redelineation is reserved for Parliament. The state government nonetheless secured a stay, pending an appeal, preventing the EC proceeding further with the redelineation; but the Court of Appeal swiftly overturned that stay. Other court challenges to various EC recommendations were also mounted, unsuccessfully, by groups of voters in other states. The deluge of litigation, however, appears to have significantly delayed the completion of the redelineation exercise which, under Article 113(2)(iii) of the Federal Constitution, must conclude by September 2018.

The redelineation exercise is a serious matter due to the persistent problem of electoral malapportionment and gerrymandering in Malaysia. Coupled with Malaysia’s first-past-the-post electoral system, the absence of concrete rules and ratios governing the apportionment of electors to constituencies in Part I of the Thirteenth Schedule (which sets out the so-called Principles Relating to the Delimitation of Constituencies) has already produced a situation where, in the previous general election, the ruling coalition polled 47 percent of the votes in an essentially two-party contest, yet secured 60 percent of the parliamentary seats. 10 The latest redelineation exercise will allegedly exacerbate the problem even further; to cite but one example, one of the new constituencies it would produce will contain approximately ten times more electors than another. 11 There are also serious allegations of ethnic discrimination in the redrawing of constituency boundaries. 12 Since the exercise directly affects not only the question of who forms the government post-election but also whether a government emerges with the two-thirds majority needed to amend the Federal Constitution, this is a debate of momentous significance.

3.2. Two landmark cases on separation of powers

In Semenyih Jaya Sdn Bhd v. Pentadbir Tanah Daerah Hulu Langat & Anor, 13 the Federal Court re-examined a 1988 constitutional amendment that deleted “the judicial power of the Federation” from the provision in the Federal Constitution establishing the courts of first instance (article 121(1)). Departing from precedents interpreting this amendment as having drastically curbed the jurisdiction and powers of the Malaysian courts vis-à-vis parliament, 14 the Federal Court stridently affirmed that judicial power, judicial independence, and the separation of powers “are as critical as they are sacrosanct in our constitutional framework.” 15 Therefore, article 121(1) was interpreted as continuing to enshrine the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary as basic features of the Federal Constitution. 16 Judicial power to adjudicate matters brought to court is vested only in the courts, and “any alterations made in the judicial functions would be tantamount to a grave and deliberate incursion into the judicial sphere.” 17 Thus, the Federal Court struck down a statutory provision restricting the courts’ ability to determine whether owners of land compulsorily acquired by the government had been adequately compensated in accordance with the rights to property protected under article 13 of the Federal Constitution. This reassertion of judicial power augurs well for the role of the courts in safeguarding the supremacy of the Federal Constitution and the rule of law.

Semenyih Jaya also revived discussion of the “basic structure doctrine,” under which a legislature cannot amend the written constitution in ways that would destroy its basic structure, even if the stipulated amendment procedure is followed. The Federal Court’s explicit assertion that parliament does not have the power to amend the Federal Constitution to the effect of undermining the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary enshrined therein 18 is a landmark development that departs significantly from previous rulings on the issue and brings Malaysia in line with some other Commonwealth jurisdictions.

In Teng Chang Khim (appealing as Speaker of Selangor State Legislative Assembly) v. Badrul Hisham bin Abdullah & Anor, 19 the Federal Court clarified the limits of judicial intervention into legislative proceedings, given the concept of parliamentary privilege. The Speaker’s act of declaring a member of the state Legislative Assembly seats vacant upon the latter’s prolonged absence without leave—as the Speaker is empowered to do under the Selangor State Constitution—was held to be “inevitably connected with the essential business of the Legislative Assembly,” such that it was protected by parliamentary privilege under article 72(1) of the Federal Constitution, even though the declaration itself was made at a press conference and not in formal Assembly proceedings. The Federal Court clarified that the court could only intervene if the Legislative Assembly, or a committee or officer thereof, was acting ultra vires its legal powers. Otherwise, it would be non-justiciable due to parliamentary privilege.

3.3. Religion and administrative power

In A Child & Others v. Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara & Others , 20 the Court of Appeal examined the proper exercise of administrative power in matters implicating religious identification. In this case, a child was born out of wedlock under Syariah law to Muslim parents. When the National Registration Department (NRD) issued the birth certificate, the child’s name bore the patronymic surname bin Abdullah instead of his father’s name. This was done against the wishes of the parents, who proceeded to make an application to correct the surname to reflect the name of the father. The NRD rejected the application and justified the decision on religious grounds, asserting that under Syariah law—which governs Muslims in Malaysia—an illegitimate Muslim child could not bear the name of his father but must be ascribed with the surname bin Abdullah. The director-general of the NRD relied on two fatwas from the National Fatwa Committee in 1981 and 2003 in preference to the statutory provisions governing his exercise of power, i.e., the Births and Deaths Registration Act 1957 (BDRA).

The Court of Appeal judgment, in favor of the appellants, is significant for three reasons. The first concerns the reach of religious authorities and injunctions in civil or “secular” matters. Unlike the High Court decision that approved the NRD’s reliance on Islamic law in deciding an illegitimate child’s surname, the Court of Appeal insisted that this issue is governed only by the BDRA. From this perspective, the NRD had acted irrationally and exceeded the scope of its power, as it only needed to consider whether the appellant had met the statutory registration requirements. The Court stressed that the BDRA does not sanction the application of Islamic law or principles in the registration process 21 and that fatwas are irrelevant to the exercise of statutory duties under the BDRA. 22

Second, the Court’s reasoning has implications for the country’s federal arrangement in matters involving Islam. National registration is a “civil” matter under the federal list of powers and any attempt to allow fatwas —which do not have binding or legislative force in this particular instance—to dictate the administration of civil law would be unconstitutional. The case also raises a question about a federal body encroaching on state authority in Islamic law matters. The fatwas in question, having been issued by the federal-level National Fatwa Committee, could not have applied to the appellants, who were residents of the state of Johor. By deciding the way it did, the Court of Appeal keeps intact the constitutionally demarcated federal and state division of powers—powers that have recently been increasingly blurred by fervent exercises of power by federal-level religious bodies.

Finally, the judgment displayed great sensitivity to extra-legal considerations, i.e., as the Court aptly expressed, “whether an innocent child should be subjected to humiliation, embarrassment and public scorn for the rest of his life.” 23 This of course does not dilute the significance of the legal reasoning offered by the Court, but when considered together with the astute legal analysis, overall the decision is a welcome approach to deciding important questions involving religion and constitutional law.

3.4. Religion and freedom of expression

One of the most prominent cases this year was the ban on a book by a Canadian lesbian author titled Allah, Liberty & Love: The Courage to Reconcile Faith and Freedom and its translated Malay version. The stated ground for the ban was that the book was prejudicial to morality and public order. Following the ban, the enforcement division of the Selangor state religious department raided the offices of the publisher of the translated book and sought to charge the director of the publishing house before the Syariah Court under the Syariah Criminal Offences (Selangor) Enactment 1995. Under section 16 of the Enactment, a person who publishes or has in his possession religious publications contrary to Islamic law is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding RM3000 and/or imprisonment not exceeding two years. The publisher and the director challenged the provision in the Enactment and the actions of the religious department officers on constitutional and administrative law grounds. The High Court dismissed the application on a preliminary objection, 24 but on appeal, the Court of Appeal held that the dismissal was erroneous and remitted the matter to the High Court for a substantive hearing of the judicial review application. 25

Another case to monitor concerns the constitutionality of a fatwa by the Selangor Fatwa Committee against a prominent women’s rights group, Sisters In Islam, designating the group “deviant.” The group’s challenge was also initially dismissed by the High Court on the basis that only Syariah courts have the power to deal with a religious decree. However, the Court of Appeal reversed the ruling and remitted the case back to the Kuala Lumpur High Court. 26 This will be another important case as it implicates the scope of a religious fatwa committee’s powers and the extent to which it is subject to the Federal Constitution’s guarantees of fundamental liberties, which include the freedom of association and assembly as enshrined in article 10.

3.5. Child conversions and Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976

In November 2016, a bill was tabled in parliament to amend the Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976, which included provisions requiring both parents in a civil marriage to consent to a minor’s conversion into Islam and providing that a child will remain in the religion of his or her parents at the time the marriage was registered. 27 This offered the best hope for an end to lingering problems brought about, in part, by civil– Syariah jurisdictional battles in matters concerning conversions. 28 However, when parliament passed the bill in August 2017, section 88A, which would have invalidated unilateral conversions of children, was conspicuously missing. The government claimed that it withdrew the provision as it would conflict with existing Federal Court decisions on the unilateral conversion of children. 29

Even though the final amendment contained positive developments—for instance, it cemented the position that disputes relating to custody, maintenance, and matrimonial assets that arise from the dissolution of a civil marriage must be resolved in the civil courts rather than the Syariah courts (despite the conversion of one spouse to Islam), as well as inserting a provision that both the converted and non-converting spouse could petition for divorce before the civil courts—critics argue that the main objective behind efforts to amend the law had always been the issue of unilateral conversion. The fact that section 88A fell through demonstrates how the government and the political process could cave in to majoritarian pressures surrounding the question of conversion. The passing of the bill may well have ended any legislative initiative to resolve the long-standing controversy surrounding unilateral conversions of underage children. 30 It also raises a crucial question—if the judicial and political processes do not protect fundamental rights and minorities, what recourse would citizens then have?

3.6. Controversial extension of Chief Justice’s tenure

In July, the government announced that Tun Raus Sharif’s term as Chief Justice (CJ) of the Federal Court (the highest judicial appointment in Malaysia) would be extended for three years from August 4, 2017, while Tan Sri Zulkifli Ahmad Makinudin would continue as President of the Court of Appeal (PCA) for two years from September 28, 2017. Both senior judges were to have retired on these dates upon reaching the constitutional age limit for judges of the Federal Court. This unprecedented extension of the CJ’s and PCA’s tenure beyond retirement age was purportedly done under article 122(1A) of the Federal Constitution, which allows the appointment of ‘additional judges’ of the Federal Court beyond the age limit. However, it remains highly questionable whether that provision allows for a judge’s tenure qua CJ and PCA (as opposed to an ordinary membership of the Federal Court) to be extended in that manner.

Several parties subsequently attempted to challenge these appointments by way of judicial review. In November, former Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s application for judicial review was dismissed by the High Court on the basis that there could be no statutory duty for the Prime Minister to advise the King to revoke the allegedly unconstitutional appointments. 31 In December, another application for judicial review, by opposition party Amanah, was also dismissed due to lack of locus standi . 32

The Malaysian Bar took a strong stand on the matter, convening an Extraordinary General Meeting on August 3, at which it resolved that these extensions were “unconstitutional, null and void.” 33 The Bar also resolved that it would “no longer have confidence” in these two judges continuing to hold office as CJ and PCA, and mandated the Bar Council to institute legal proceedings challenging the constitutionality of the extensions. This duly took place and on December 19, 2017, and the Bar was granted leave by the High Court to refer six questions regarding the constitutionality of these appointments for determination by the Federal Court in 2018. A singular difficulty arising in this litigation is how the case will be heard and disposed of, given that the persons who are the subject of the challenge are currently occupying the top two positions in the very same court hearing the case.

The main event in 2018 is undoubtedly the upcoming fourteenth general election, in which all seats in the Lower House of the federal parliament, as well as every state legislature except Sarawak’s, will be up for election. This election will test whether the incumbent BN can head off the main opposition Coalition of Hope (PH) and even possibly recapture a two-thirds majority in parliament, which would enable it to amend the Federal Constitution at will once again.

If 93-year-old former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad—the one-time strongman of Malaysia turned government arch-critic—remains at the helm of PH, this election will demonstrate how far he can sway popular support against scandal-hit incumbent Prime Minister Najib Razak, particularly among the latter’s core constituency of Malay and indigenous voters. This election will also determine—at least for the duration of the next parliament—the ability of the Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS) to continue pushing its Islamist agenda for Malaysia since PAS has chosen to align itself with neither the BN nor PH. 34

The Malaysian Bar’s challenge to the constitutionality of the reappointment of the Chief Justice and the President of the Court of Appeal—presently before the Federal Court—is a case to watch in 2018. This scenario, unprecedented in Malaysian constitutional history, will test the ability of the apex court to deliver a convincing and well-reasoned resolution capable of sustaining current efforts to rebuild public confidence in the Malaysian judiciary.

Cases on religious issues, as highlighted above, will also, as ever, be notable in 2018. Three such cases—the government’s appeal against the A Child & Others decision at the Federal Court, and the substantive judicial review applications involving Canadian author Irshad Manji and Sisters in Islam—will be particularly important to watch.

See Jaclyn L. C. Neo et al., Malaysia: Developments in Malaysian Constitutional Law , in i · CONnect-Clough Center 2016 Global Review of Constitutional Law 125, 125–126 (Richard Albert et al. eds., 2016).

Fed. Const. Malaysia art. 3(1).

Central Intelligence Agency , The World Factbook , https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/my.html .

Decision adopted by the Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians at its 152nd session (Geneva, January 23 to February 3, 2017 ), Inter-Parliamentary Union, available at http://archive.ipu.org/hr-e/comm152/mal21.pdf .

Dangerous Drugs (Amendment) Act 2017, § 2. The Act was passed by both Houses of Parliament on December 14, 2017.

Singapore: Executions Continue in Flawed Attempt to Tackle Drug Crime, Despite Limited Reforms , Amnesty International (Oct. 11, 2017), http://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/10/singapore-executions- continue-in-flawed-attempt-to-tackle-drug-crime/ .

See, e.g. , Mohd Faizal bin Musa v. Minister of Home Affairs, 11 M.L.J. 397 (2017).

Jenny bt Peter @ Nur Muzdhalifah Abdullah v. Director of Jabatan Agama Islam Sarawak & Ors and Other Appeals, 1 M.L.J. 340 (2017); Mardina Tiara bt Abdullah Emat @ Margaret ak Emat v. Director of Jabatan Agama Islam Sarawak & Ors, 9 M.L.J. 293 (2017); Syarifah Nooraffyzza Wan Hosen v. Director of Jabatan Agama Islam Sarawak & Ors, No. Q-01(A)-45-02/2015 (Court of Appeal July 7, 2017).

Kerajaan Negeri Selangor v. Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya & Others, M.L.J. Unreported 1902 (2017).

What’s Malay for Gerrymandering? , The Economist, Aug. 9, 2014, available at http://www.economist.com/news/asia/21611139-years-delineation-electoral-boundaries-will-determine-future-malaysian-politics-whats .

Kenneth Tee, Selangor Voters Cite Massive Size Discrepancies in Objections to EC’s Redelineation , Malay Mail Online (Jan. 3, 2018), http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/selangor-voters-cite-massive-size-discrepancies-in-objections-to-ecs-redeli#mcKXzzPe1XfLxgEw.97 .

Melati A. Jalil & Chan Kok Leong, EC’s Redelineation Clearly Biased, Critics Tell PM’s Aide , The Malaysian Insight (Dec. 19, 2017), http://www.themalaysianinsight.com/s/28456/ .

3 M.L.J. 561 (2017).

See Public Prosecutor v. Kok Wah Kuan, 1 M.L.J. 1 (2008); Danaharta Urus Sdn Bhd v. Kekatong Sdn Bhd, 2 M.L.J. 257 (2004).

Semenyih Jaya, 3 M.L.J. at 593.

Id. at 590.

Id. ¶¶ 67, 84.

5 M.L.J. 567 (2017).

4 M.L.J. 440 (2017).

Id. at 455.

Id. at 453.

Id. at 445.

ZI Publications Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Jabatan Agama Islam Selangor & Ors, [2017] 1 LNS 1816.

ZI Publications Sdn Bhd & Anor v. Jabatan Agama Islam Selangor & Ors, No. W-01(A)-383-10/2016 (Court of Appeal July 17, 2017).

Zurairi AR, SIS Allowed to Continue Judicial Review Against ‘Deviant’ Fatwa , Malay Mail Online (Mar. 2, 2017), http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/sis-allowed-to-continue-judicial-review- against-deviant-fatwa#il1RD6BiAg4YzWCS.99 .

Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) (Amendment) Bill 2016, § 88A.

See, e.g. , Jaclyn Neo, Competing Imperatives: Conflicts and Convergences in State and Islam in Pluralist Malaysia , 4 Oxford J. L. & Rel. 1 (2015).

In Subashini a/p Rajasingam v. Saravanan a/l Thangathoray and Other Appeals, 2 M.L.J. 147 (2008), the Federal Court held that the conversion of a child by either parent is valid, i.e. it does not require the consent of both parents. This decision was affirmed in Pathmanathan Krishnan v. Indira Gandhi Mutho and Other Appeals, 1 C.L.J. 911 (2016). See Dian A. H. Shah, Religion, Conversions and Custody: Battles in the Malaysian Appellate Courts , in Law and Society in Malaysia: Pluralism, Religion, and Ethnicity 145, 150–152 (Andrew Harding & Dian A. H. Shah eds., 2018).

See generally Shah, supra note 29.

Dr Mahathir Loses Bid to Challenge Appointment of Two Judges , New Straits Times (Nov. 6, 2017), available at http://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2017/11/299989/dr-mahathir-loses-bid-challenge-appointment- two-judges .

Ram Anand, Amanah Fails in Judicial Review Bid Against CJ’s Appointment , Malay Mail Online (Dec. 19, 2017), http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/amanah-fails-in-judicial-review-bid-against- cjs-appointment#kTUFY0YRc4pV3e9q.97 .

Resolution Adopted at The Extraordinary General Meeting of the Malaysian Bar Held at KL and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall (Thursday, 3 Aug 2017 ), The Malaysian Bar (Aug. 3, 2017), http://www.malaysianbar.org.my/malaysian_bar_s_resolutions/resolution_adopted_at_the_extraordinary_general_meeting_of_the_malaysian_bar_held_at_kl_and_selangor_chinese_assembly_hall_thursday_3_aug_2017.html .

Yang Razali Kassim, Is A New PAS Emerging? , Straits Times, May 5, 2017, available at http://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/is-a-new-pas-emerging .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| June 2018 | 803 |

| July 2018 | 571 |

| August 2018 | 32 |

| September 2018 | 43 |

| October 2018 | 50 |

| November 2018 | 35 |

| December 2018 | 37 |

| January 2019 | 10 |

| February 2019 | 12 |

| March 2019 | 20 |

| April 2019 | 16 |

| May 2019 | 26 |

| June 2019 | 11 |

| July 2019 | 18 |

| August 2019 | 13 |

| September 2019 | 10 |

| October 2019 | 13 |

| November 2019 | 26 |

| December 2019 | 7 |

| January 2020 | 15 |

| February 2020 | 7 |

| March 2020 | 15 |

| April 2020 | 12 |

| May 2020 | 8 |

| June 2020 | 32 |

| July 2020 | 45 |

| August 2020 | 34 |

| September 2020 | 31 |

| October 2020 | 228 |

| November 2020 | 120 |

| December 2020 | 115 |

| January 2021 | 65 |

| February 2021 | 69 |

| March 2021 | 68 |

| April 2021 | 76 |

| May 2021 | 99 |

| June 2021 | 119 |

| July 2021 | 126 |

| August 2021 | 61 |

| September 2021 | 95 |

| October 2021 | 185 |

| November 2021 | 216 |

| December 2021 | 164 |

| January 2022 | 111 |

| February 2022 | 78 |

| March 2022 | 59 |

| April 2022 | 112 |

| May 2022 | 84 |

| June 2022 | 133 |

| July 2022 | 47 |

| August 2022 | 119 |

| September 2022 | 62 |

| October 2022 | 75 |

| November 2022 | 115 |

| December 2022 | 82 |

| January 2023 | 55 |

| February 2023 | 56 |

| March 2023 | 38 |

| April 2023 | 37 |

| May 2023 | 44 |

| June 2023 | 34 |

| July 2023 | 57 |

| August 2023 | 34 |

| September 2023 | 32 |

| October 2023 | 99 |

| November 2023 | 139 |

| December 2023 | 65 |

| January 2024 | 85 |

| February 2024 | 37 |

| March 2024 | 73 |

| April 2024 | 130 |

| May 2024 | 67 |

| June 2024 | 56 |

| July 2024 | 32 |

| August 2024 | 22 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- I·CONnect

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1474-2659

- Print ISSN 1474-2640

- Copyright © 2024 New York University School of Law and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Read The Diplomat , Know The Asia-Pacific

- Central Asia

- Southeast Asia

- Environment

- Asia Defense

- China Power

- Crossroads Asia

- Flashpoints

- Pacific Money

- Tokyo Report

- Trans-Pacific View

Photo Essays

- Write for Us

- Subscriptions

Malaysia’s Election and Southeast Asia: Issues and Implications

Recent features.

Imran Khan’s Biggest Trial

Seoul Is Importing Domestic Workers From the Philippines

The Rise, Decline, and Possible Resurrection of China’s Confucius Institutes

Nowhere to Go: Myanmar’s Exiled Journalists in Thailand

Trump 2.0 Would Get Mixed Responses in the Indo-Pacific

Why Thaksin Could Help Hasten a Middle-Class Revolution in Thailand

Can the Bangladesh Police Recover?

The Lingering Economic Consequences of Sri Lanka’s Civil War

What’s Driving Lithuania’s Challenge to China?

Hun Manet: In His Father’s Long Shadow

Afghanistan: A Nation Deprived, a Future Denied

In Photos: Life of IDPs in Myanmar’s Rakhine State

Asean beat | politics | southeast asia.

As a leading member of ASEAN, Malaysia’s foreign policy in Southeast Asia will have implications for GE14 and vice versa.

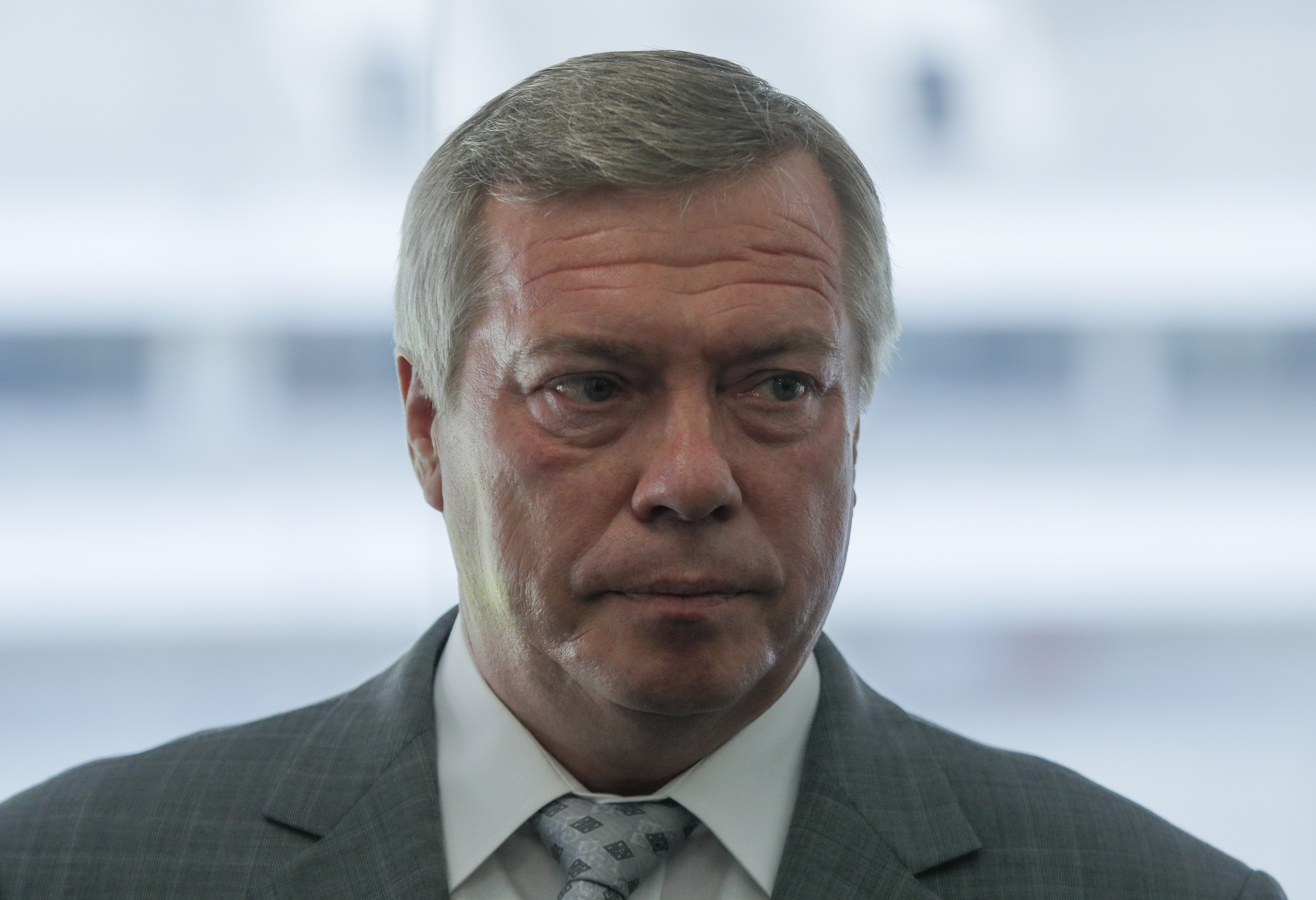

Myanmar’s State Counsellor and Foreign Minister Aung San Suu Kyi, center, gestures while talking to Thailand’s Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-Cha, right, and Malaysia’s Prime Minister Najib Razak during the 20th ASEAN-China Summit in metro Manila, Philippines (Nov. 13, 2017).

The upcoming Malaysian GE14 on May 9, 2018, has been dubbed as the most unpredictable and competitive general election in the history of the nation. The Barisan Nasional (BN) government, helmed by Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak, who is facing strong challenges to his political legitimacy and survival, is doing all it can to stay in power. Najib’s key opponent is none other than former mentor and premier of Malaysia Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, as he leads a spirited but fragile Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition.

Similar to previous elections, the battle lines of GE14 will be drawn mainly on domestic issues rather foreign affairs. In fact, there is a dearth of scholarly literature examining the precise relation between Malaysia’s foreign policy and general elections. Yet, one cannot ignore the fact that foreign policy issues, including Southeast Asian affairs, have been featured in Malaysia’s general elections, albeit in a low-key manner. And GE14 is no exception.

Malaysia’s Foreign Policy in Southeast Asia: PH vs BN

Comparing the GE14 manifestos of the BN government and PH coalition, some observations could be made. The PH manifesto, Buku Harapan , devotes about three pages to Malaysia’s foreign affairs on the global stage and in Southeast Asia as well (see pages 153 to 155). This is unlike the GE13 manifesto of PH’s predecessor, Pakatan Rakyat, which had almost no reference to foreign policy matters.

With regard to Southeast Asia, the PH coalition intends to raise Malaysia’s prominence in ASEAN. For example, Malaysia would play a more active role in international organizations such as the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), which works closely with the ASEAN Secretariat and research institutes from East Asia to provide intellectual and analytical research and policy recommendations; as well as building up the economic, political, security, and sociocultural aspects of the ASEAN community. More resources would be directed to Wisma Putra (Malaysia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs) so as to strengthen the country’s representation at the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR). The PH manifesto also advocated support for the Rohingya. The manifesto even indicated that Malaysia will be positioned as a Middle Power.

In contrast, the BN manifesto, Bersama BN Hebatkan Negara , has grouped foreign policy issues under the section on safeguarding national sovereignty and security of the people. While it does not explicitly mention Malaysia’s role in ASEAN, it briefly states some policy goals in the context of Southeast Asia. For instance, it highlights continuing efforts to resolve regional conflicts in southern Thailand, southern Mindanao in the Philippines, and Rakhine state in Myanmar; and expanding regional defense diplomacy with countries that share borders with Malaysia (see page 90).

Indeed, Malaysia’s mediation and humanitarian efforts in regional conflicts within Southeast Asia have been a highly symbolic means of demonstrating the country’s leadership and influence within ASEAN. One could expect the BN government to maintain these endeavors without much disruption if it is returned to power after GE14.

It is not far-fetched to suggest these endeavors would continue even if the PH coalition wins the election. PH’s foreign policy objectives regarding Southeast Asia and ASEAN, as outlined in its manifesto, share fundamental similarities with existing and well-established features of Malaysia’s foreign policy thrust, namely that ASEAN is a cornerstone of Malaysia’s foreign affairs.

Yet without details on how to achieve these objectives, it is unclear how a PH government could outperform the BN government in foreign policy ventures, let alone match Mahathir’s foreign policy achievement in propelling Malaysia to global prominence as a champion of the Islamic world and developing countries, and ASEAN multilateralism.

Southeast Asia: An Arena for Malaysia’s GE14

Right from the start of his tenure, Najib has sought to enhance Malaysia’s global standing, including its influential standing in ASEAN. Success in foreign policy is important for Najib, as it would contribute to boosting the image and legitimacy for the BN government back home. The reason for this is apparent. The Najib regime has had to contend with a strong domestic political opposition, which made significant strides in the 2008 elections. The BN government’s GE13 electoral setback in 2013, and mounting political, economic, and societal challenges in recent years, have further weakened Najib’s leadership considerably.

At this point, one might even question whether foreign policy achievements are politically expedient at all during elections, especially since Najib’s penchant for foreign policy ventures and highlighting successes in this arena did not seem to have worked in his favor during GE13. Yet one cannot deny that since 2013, the BN government has tried to ensure, or at least give the appearance, that its foreign policy follows closely to what was outlined in its GE13 manifesto. For example, Malaysia, as ASEAN chair in 2015, helped in the realization of the ASEAN economic community in that year. Malaysia has also continued to engage in humanitarian efforts in conflict zones, such as Mindanao, southern Thailand, and more recently, Rahkine state.

Malaysia’s humanitarian support for the Rohingya Muslim minority is not only aimed at demonstrating leadership in ASEAN affairs. Since the 2013 electoral setback, the Najib government has resorted to conservative Islamization in Malaysia in an effort to shore up the regime’s Islamic credentials and secure the support of the Malay-Muslim community. Thus, the BN government’s concerns for the plight of the Muslim Rohingya is mostly likely a politically shrewd tactic, as it feeds into the religious rhetoric that is being projected by the country’s ruling elites.

However, the single most important foreign policy issue for GE14, which has stolen the limelight, is Malaysia’s ties with China. It is not surprising that the BN government has been establishing stronger ties with China so as to improve economic performance and political legitimacy. One of the most visible sign of this is Malaysia’s deep entrenchment in China’s Belt and Road initiative.

Najib’s attempt to draw closer to China has incurred strong criticisms from the PH coalition over perceived negative economic, political, and social outcomes for Malaysia. Yet Sino-Malaysia relations are not merely a domestic political controversy, as it has strategic implications for Southeast Asia as well.

Najib’s foreign policy has sought to build up Malaysia’s position as a key conduit through which China-ASEAN relations can improve significantly. Likewise, China’s political elites recognize that Sino-Malaysia relations are at the forefront of China’s ties with ASEAN. For China, building stronger relations with Malaysia is a significant means to expand China’s economic interests, prominence, and influence throughout Southeast Asia.

To be sure, Malaysia is unlikely to become another Cambodia, through which China could exert undue pressure to alter regional affairs in its favor. Malaysia has consistently sought to pursue an independent, nonaligned, and neutral foreign policy. Malaysia has also been striving to hedge between China and the United States, ostensibly through economic relations with the former and security arrangements with the latter to offset potential risks associated with the rise of China.

Nevertheless, it is uncertain how Malaysia could continue to maintain this delicate balance in the future, given Malaysia’s increasing economic dependence on a rising and increasingly assertive China. Gradually, Malaysia’s leaders may find themselves having less room for maneuver to stave off China’s political and economic pressure to augment Malaysia’s posture in the region. If Malaysia’s foreign policy autonomy erodes because of China’s pressure, Malaysia’s claims to be a credible leader to galvanize ASEAN to engage China through rules-based interactions is at risk.

At this stage, it is still too early to gauge the actual impact of the aforementioned developments on the upcoming elections, let alone the outcome of GE14 on Southeast Asia affairs. It is quite certain, however, that foreign policy issues will be played up by both sides of the political divide to maximize gains for this elections.

In the event that the PH coalition wins the elections (though this is unlikely), it would be the first time in Malaysia’s history that a non-BN government steers the nation’s foreign policy. It would also usher in a new era and new dimension to the evolution of Malaysian diplomacy.

Of course, should the BN government retain power, it cannot afford to rest on its laurels, and assume that it can carry on its foreign policy conduct away from the close scrutiny of political opposition and public opinion in Malaysia. The events leading right up to GE14 show that future analysis of post-GE14 elections must reckon with the realities of growing domestic contestation over foreign policy.

This article is part of a series of commentaries by RSIS on the 14th Malaysian General Election.

David Han Guo Xiong is a Senior Analyst with the Malaysia Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Malaysia's Fierce Campaigning in Action

By alexandra radu.

Malaysia Kicks off Election Campaign Ahead of November 19 Vote

By sebastian strangio.

Malaysia's New Political Tsunami

By michio ueda.

Ahead Of Elections, Malaysians Protest Controversial Laws

Captured Myanmar Soldier: Army Joined Hands With ARSA Against Arakan Army Advance

By rajeev bhattacharyya.

China Rejects the ‘San Francisco System’

By kawashima shin.

A New Bangladesh Is Emerging But It Needs India Too

By muqtedar khan and umme salma tarin.

By Aleksander Lust

By Kunwar Khuldune Shahid

By Haeyoon Kim

By Si-yuan Li and Kenneth King

By Hailun Li

Shopping Cart

Explainer: Malaysia’s Electoral System

Don’t forget to check out New Naratif’s Election 101 page on Malaysia GE15!

This brief article presents an overview of the Federation of Malaysia’s (Malaysia) electoral system, how it works, how and why it has been altered over the years, and the challenge it presents for representative democracy in Malaysia. [1], [2]

“…the view we take is that democratic government is the best and most acceptable government. So long as the form is preserved, the substance can be changed to suit conditions of a particular country.” Tun Abdul Razak Hussein, Second Prime Minister of Malaysia. [3]

A democracy’s electoral system is fundamental to its legitimacy, as from the electoral system, the form and style of representation flow, the relative strength of political parties, the formation of government and the development of policy positions. In a representative democracy, the structure of the state’s electoral system plays a critical role in determining the nature and form of political discourse and parliamentary representations. The electoral system establishes who may vote, how many representatives are to be chosen from which areas, who oversees the conduct of elections, and how votes are counted. Adjustments and manipulations of these elements can have severe positive or negative consequences on the stakeholders. Electoral system changes also strongly impact the ability of citizens to participate in the state’s general political discourse and democratic processes⎯as voters, candidates, members of political parties, etc. Beyond any formal barriers, the perceived fairness or otherwise of the electoral process can affect citizens’ willingness to engage in the democratic process. [4]

Malaysia considers itself a democracy—a federation of 13 states and three federal territories [5] , with a form of government that is constitutional, monarchical, and parliamentary at both the state and federal levels, with every state having its constitution. Common to every state is the Federal Constitution (FC). Since 1954, Malaysia has adopted election laws generally practised (at that time) in the United Kingdom. The primary election laws are found in the Elections Act 1958 , Elections Offences Act 1954 , Election Commission Act 1957 , Elections (Registration of Electors) Regulation 2002 , and Elections (Conduct of Elections) Regulations 1981 . The electoral system subscribes to the first-past-the-post (FPTP) or plurality method. [6], [7]

As Malaysia is a federation, it has two levels of elections⎯the federal level, which elects the members of Parliament (MPs) for the Dewan Rakyat (DR), and the state level, which elects members for the Dewan Undangan Negeri (state legislative assemblies/DUN). There are 222 seats representing the 222 constituencies. The Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) is part of the bicameral Parliament, with the Dewan Negara (DN) being the Upper House. There is no election for members (Senators) of the Dewan Negara as they are nominated by their DUN—two for each state. The Yang diPertuan Agong appoints the remaining 44 members from names proposed by the government, including four appointed to represent the federal territories. [8]

However, Malaysia’s ‘democratic’ status is plagued by two issues: (a) that elections are neither free nor fair; and (b) it has never experienced party alternation since the first elections in 1955, under British home rule, and the first GE after independence in 1959 until GE14 in 2018 (63 years of single party/coalition rule). [9]

There have been 14 general elections (GE) since Malaysia gained independence in 1957. [10] The Barisan Nasional (BN) and its predecessor, the Alliance (Perikatan), had won all (except the historic GE14 in 2018). An important reason for BN’s success is the electoral system. [11]

Issues with Malaysia’s Electoral System

Characterised by excessive malapportionment and gerrymandering [12] , enabled by 63 years of single-party/coalition rule, Malaysia’s FPTP electoral system has been central to Malaysia’s democratic deficit, yet constituency malapportionment and gerrymandering only began with zest at the 1974 delimitation review. [13]

After Merdeka , following the Reid Constitutional Commission (1956-1957), a constitutional monarchy, a federal form of government and elections based on Westminster-styled institutions was implemented. The electoral system was broadly anchored to elements of procedural democracy such as transparent and autonomous electoral institutions and procedures, freedom of political association, and campaigning, guaranteed by law and constitutional provisions which devolve duties of conducting elections to an independent EC.

Two issues have driven the degradation of Malaysia’s electoral system since then—communalism [14] and consociationalism. [15] According to Ratnam, communal politics, a feature of Malaya’s plural society [16] , valorised communal interests through ethnically constituted political parties. Moreover, ethnic cleavages were reinforced with religious affiliation (Malays were Muslims, Chinese were Buddhists/Taoists, and Indians were Hindus). Communalism was seen as a social feature of plural societies detrimental to social and national integration. [17] In 1957, the population of the Federation of Malaya were Malays (50%), Chinese (37%), Indians (11%), and others (2%). The Malays, led by UMNO, had already made their displeasure of giving equal citizenship to non-Malays (immigrants in Malaya) known by stopping the proposal of a Malayan Union in 1946. The British replaced the Malayan Union with the Federation of Malaya (Persekutuan Tanah Melayu) in 1948. This provided for Malay hegemony of the political system. [18]

Communalism came to be mediated by political processes of ethnic power-sharing in the mid-1950s through the Alliance/Perikatan (United Malay National Organisation/UMNO, Malaysian Chinese Association/MCA & Malaysian Indian Congress/MIC). [19] However, Lijphart recommended four conditions for the successful implementation of consociationalism: (1) a grand coalition of all ethnic groups, (2) a mutual veto in decision-making, (3) an ethnic proportionality in the allocation of opportunities and offices, and (4) ethnic autonomy. [20] UMNO systematically violated these conditions. The party representing the Malay community on the peninsular, and who was considered as first among equals, grew in strength to become the hegemonic power in the expanded replacement of the Alliance, the Barisan Nasional (BN) after the May 13, 1969, race riots⎯itself triggered by the poor performance of the Alliance/Perikatan at the 1969 GE (GE3).

The first significant change made to the electoral system occurred in 1962. The EC undertook the first review of electoral constituencies after the 1959 GE (GE1). It was not well received by UMNO, which had lost Malay ground to the Pan Malaysian Islamic Party (PMIP/PAS) in the east coast states of Kelantan and Terengganu. The Alliance government then introduced the Constitutional (Amendment) Act 1962, that not only annulled the revised constituencies but also removed the EC’s final power of decision on electoral constituencies and transferred it to a simple majority in Parliament. [21] This meant that the EC could only submit reviews to the prime minister, who could make revisions before it is presented to Parliament. The 1962 Act also effectively annulled the EC’s new delineations, reverted them to the 1959 situation, and emasculated the EC’s impartial and independent role in constituency delimitations.

The original FC (1957) allowed for a 15% deviation across constituencies from the state average. [22] These were amended in 1962 (discussed above), 1963, and 1974. The 1962 amendment widened the range of permissible deviation from 15% to 33.33%. It also changed the basis of comparison from the state to the national average. The 1963 amendment⎯which came with the Malaysia Act 1963⎯deliberately introduced inter-state malapportionment to underrepresent Singapore and overrepresent Sabah and Sarawak. UMNO wanted to overcome the threat posed by Singapore’s 1.7 million largely Chinese inhabitants by balancing them with the natives of Sabah and Sarawak, whom UMNO assumed would be allies of the Malays. The overrepresentation of Sabah and Sarawak was also part of the 20-point agreement with Sabah and the 18-point agreement with Sarawak as part of the formation of the Federation of Malaysia.

Expansion of the legislature accompanied interstate malapportionment, as the number of federal and state seats increased with constituency delimitation exercises in 1973, 1974, 1977, 1984, 1987, 1994, 1996, 2003, 2005, 2015 and 2016. [23]

The Constitutional (Amendment) Act (No. 2) of 1973 was, in particular, very significant because it removed the EC’s power to apportion parliamentary constituencies among states. The number was now specified in Article 46 of the FC, amendable by the government with a two-thirds majority.

However, despite elections not being free and fair, Malaysia did experience party/coalition alternation in 2018 (GE14), even if still subject to the following systemic, structural, and institutional factors. Unfortunately, Pakatan Harapan (PH) [24] was toppled by an internal coup just 20 months later, in February 2020. The new coalition—Perikatan Nasional/PN [25] —came to power with the support of the BN and PAS. The PN administration did not last long. On August 21 2021, BN returned to power.

Issues with the electoral system remain and can be categorised under the following headings:

- The Role of the Election Commission

The Election Commission (EC) undertakes electoral administration in Malaysia. The three primary functions of the EC are the delimitation of constituencies, the preparation and revision of the electoral roll, and the conduct of elections for the Dewan Rakyat and the Dewan Undangan Negeri .

The current structure of the EC, as defined in the FC and as discussed earlier, allows for executive interference or influence as the Yang DiPertuan Agong appoints its members on the advice of the Prime Minister. During BN’s long rule, the EC (like other independent institutions/agencies and government) were an instrument for the incumbent to retain power. [26]

- Redelineation, Malapportionment and Gerrymandering of Constituencies

The last redelineation exercise was approved just before GE14. The process was rushed, controversial, and favoured BN. The principles for delineation set in Section 2 of the 13 th Schedule of the FC state that constituencies are proposed to be “approximately equal” in the number of voters, and efforts to “maintain local ties” are called for. Malapportionment violates these principles by producing the massive difference between constituency populations that result in the value of votes becoming extremely unequal. [27]

Gerrymandering, where boundaries are drawn to favour a particular party, usually by manipulating ethnic composition. According to Section 2(a), constituencies should not transgress state boundaries, and district and local authority boundaries (Pihak Berkuasa Tempatan/PBT) should help define what constitutes “local ties.” For the most part, the EC used district and PBT boundaries in their delineation except when it served their purpose to either “pack” or “crack” opposition strongholds. “Packing” concentrates an opposition party’s voting power into one district to reduce the value of each vote, while “cracking” is breaking up an opposing party’s supporters into many districts.

- Questionable Electoral Roll

The integrity of the electoral roll has always been a concern. Electoral reform groups such as MERAP, ENGAGE and Bersih 2.0 independently exposed dubious voters in the roll by analysing available electoral roll data. Some issues included an excessive number of voters registered in single addresses, voters on the roll with no address, voters with identical names and dates of birth, deceased voters, and non-citizens.

- Political Financing

Political parties are regulated by the Societies Act of 1966 under the Home Ministry. The minister has absolute discretion to declare a society illegal. Conversely, the EC has no power to register and regulate political parties. There is also a lack of regulation on political financing. Although there is the Election Offenses Act of 1954, it is rarely enforced. It does not cover the nexus between business and politics.

- Enforcement of Electoral Laws

The EC relies on the Royal Malaysian Police and the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission to enforce electoral laws, especially in election campaigning. Enforcement against electoral malpractices has been weak because the EC claims they do not have direct powers to act against preparators.

Malaysia’s Electoral System at GE15

At GE14, the reformist Pakatan Harapan toppled the incumbent BN. The PH administration and civil society initiated electoral reforms to address systemic and endemic problems inherent in the electoral system and improve the political culture in Malaysia. These broad recommendations were captured by the Report of the Electoral Reform Roundtable: [28]

- Consideration should be given to moving away from the first-past-the-post system towards a more proportional system that can promote national unity and centrism, allow for healthy competition between coalition partners, and better represent Malaysia’s diverse population in Parliament.

- So long as Malaysia retains the first-past-the-post system, it should address issues of over- and under-representation between Malaya states and within each state. Constituencies should also be fairly and impartially drawn. Seats should be distributed between the States based on electorate size. At the same time, strict numerical standards should be reinstated for variations between constituencies.

- The electoral rolls should be audited and managed in an open, inclusive, and transparent manner to build public trust. A new geocoded National Address Database should be used to audit the electoral rolls and the civil registration records of the National Registration Department. The electoral rolls should be made available for public inspection and monitoring, and the integrity of the electoral rolls should be ensured before the implementation of automatic voter registration.

- Absentee voting should be extended to Malaysian voters living in neighbouring countries and those living further afield. The EC should ensure that the campaign period is long enough and that the processes of issuing and despatching postal ballots are speedy enough to allow the ballots to be returned in time to be counted. While absentee voting facilities should be provided for some domestic voters⎯particularly East Malaysian voters in West Malaysia and vice versa⎯in the long run, voters should be encouraged to vote where they reside. Consideration should be given to holding polling for military and police voters on election day. Military and police voters should also be allowed to vote in their home constituencies via absentee voting.

- Because of the difficulties of auditing electronic and online voting systems and securing public trust in such systems, careful investigations and public consultations should be conducted before adopting any form of electronic and online voting in Malaysia.

- While it should not be for government authorities to decide what is or is not “fake news”, the Election Commission and other authorities should play a role in monitoring political spending, electoral misconduct, and hate speech online.

- The regulation of political spending must be extended to political parties and third parties, both during and outside the campaign period, and to internal party elections. Political contributions, both in cash and in kind, should also be declared and subject to limits. Public funding should take the place of some forms of private funding, and parties should have equitable and unrestricted access to state media.

- Rules and guidelines should be drawn for managing government transitions and codifying best practices and caretaker conventions. Consideration should also be given to a constitutional amendment submitting defecting Members of Parliament to re-election. Alternatively, suppose a mixed-member system is introduced. In that case, a distinction may be drawn between constituency MPs and party list MPs regarding party affiliation.

- Election offences laws should be updated to clarify the roles and powers of the various state agencies and to empower the Election Commission to monitor, investigate, and penalise breaches of election offences laws.

- The selection of Election Commissioners should be subject to scrutiny by a cross-party parliamentary committee. The Election Commission should have operational independence in staffing and budgeting, subject to scrutiny by a dedicated parliamentary select committee. The Election Commission should be given responsibility for the registration and regulation of political parties, while consideration may be given to transferring responsibility for the delimitation of constituencies to an independent boundaries commission.

Malaysia’s Electoral System and Representative Democracy

As discussed earlier, the reformist PH administration was toppled by an internal coup (Sheraton Move) just 20 months after GE14. While not stopping the reform measures, the two new administrations that came after did not pursue them with vigour. There were, however, three significant developments⎯the lowering of the voting age (Undi 18), automatic voter registration, and anti-hopping law.

In July 2019, the Malaysian Parliament enacted a constitutional amendment to lower the voting age for general elections from 21 to 18, provide for automatic registration of voters, and reduce the qualifying age to 18 for contesting a seat in the federal or state legislature. The lowering of the voting age and automatic voter registration has added 6.23 million new voters to the electoral roll., bringing the number of voters eligible to vote in GE15 to 21.17 million⎯almost 66% of Malaysians. Ironically, as argued by Chai, lowering the voting age while expanding enfranchisement has been devalued by an even more unequal representation. [29]

On October 5 2022, Malaysia’s new anti-hopping law (AHL) took effect. The AHL was enacted to address the issue of party hopping, as seen in the Sheraton Move that brought down the elected PH government. Party hopping has been a major problem in Malaysia since 1961. While there is consensus that AHL is a good development, concerns remain as there is a significant loophole where parties crossing the aisle are not punished. [30]

The opening paragraph stated why an electoral system is fundamental to a democracy’s legitimacy. The issues with Malaysia’s electoral system, as captured in section II remain, despite the increasing competitiveness of the electoral contest. The critical issue that plagues Malaysian democracy is that elections are neither free nor fair.

Beyond the recommendations provided by the Report of the Electoral Reform Roundtable in 208, serious work is being undertaken in Malaysia to reform the electoral system and other democratic institutions. Democratic backsliding⎯when core institutions are being weakened and manipulated by autocratically linked leaders⎯has occurred in Malaysia and many other countries. [31] To address democratic backsliding, Malaysians must make wise choices at GE15.

- This article borrows heavily from materials cited.

- Readers interested in comparing Singapore to Malaysia’s electoral system can read the explainer: Explainer: Singapore’s Electoral System – New Naratif .

- Ong, M. (1990). Malaysia: Communalism and the Political System. Pacific Viewpoint, 31(2), 73-95.

- Kelly, N. (2012). Directions in Australian Electoral Reform: Professionalism and Partisanship in Electoral Management. ANU Press.

- The Federation of Malaysia consists of 13 states (Perlis, Kedah, Pulau Pinang, Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Melaka, Johor, Pahang, Terengganu and Kelantan on the Peninsular, and Sabah and Sarawak on the Borneo Island), and the Federal Territories ( Wilayah Persekutuan ) of Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya on the Peninsular, and Labuan, off the Sabah coast.

- Tey, T. H. (2010). Malaysia’s electoral system: Government of the people?. Asian Journal of Comparative Law , 5 , 1-32.

- Hai, L. H. (2002). Electoral politics in Malaysia: ‘Managing’ elections in a plural society. Electoral Politics in Southeast and East Asia , 101-148.

- The Dewan Negara has an important role in the legislative process. It can introduce legislations, as well as reviews revisions, and hold debates over legislations passed by the Dewan Rakyat with some major exceptions.

- Wong, C. H., Chin, J., & Othman, N. (2010). Malaysia–towards a topology of an electoral one-party state. Democratization , 17 (5), 920-949.

- The 1955 elections were for the Malayan Legislative Council. The Federation of Malaya gained independence ( Merdeka ) on 31 st August 1957. Post- Merdeka general elections were held in 1959 (GE1), 1964 (GE2), 1969 (GE3), 1974 (GE4), 1978 (GE5), 1982 (GE6), 1986 (GE7), 1990 (GE8), 1995 (GE9), 1999 (GE10), 2004 (GE11), 2008 (GE12), 2013 (GE13), and 2018 (GE14).

- To understand how the most recent redelineation (in 2018), lead to further malapportionment and gerrymandering, please read How Malaysia’s Election is Being Rigged – New Naratif .

- Wong, CH (2018). ‘Reconsidering Malaysia’s First-Past-The-Post Electoral System: Malpractices and Mismatch’ in Weiss, M. L, & Mohd. Faisal Syam Abdol Hazis (eds), Towards a new Malaysia? : the 2018 election and its aftermath.

- Ratnam, 1965, cited in Saravanamuthu, J. (2016) Power Sharing in a Divided nation : mediated Communalism and New Politics in Six Decades of Malaysia’s Elections. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Lijphart, 1977 cited in Saravanamuthu, 2016.

- Furnivall,1948 cited in Saravanamuthu, 2016.

- Geertz, 1963 cited in Saravanamuthu, 2016.

- Ong, Michael. (1990). Malaysia: Communalism and the Political System. Pacific Viewpoint, 31(2), 73-95.

- Saravanamuthu, J. (2016) Power Sharing in a Divided nation : mediated Communalism and New Politics in Six Decades of Malaysia’s Elections. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Lim, 2005 cited in Saravanamuthu, 2016.

- Lim, 2002 cited in Wong, CH (2018).

- Wong, CH, 2018.

- The members of Pakatan Harapan (PH) originally were Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), Democratic Action Party (DAP) and Parti Amanah Negara (Amanah), which splintered from the Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS). It was formed in 2015. Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu), an UMNO splinter party joined PH in 2017.

- Perikatan Nasional/PN was formed when Bersatu and several MPs from Keadilan/PKR left PH and formed an alliance with the BN and PAS. Several MPs from Sabah and Sarawak also switched allegiance from PH to PN.

- Thomas Fan, 2019, Malaysia Begins Rectifying Major Flaws in its Election System, ISEAS.

- Ostwald, K. (2017). Malaysia’s Electoral Process: The Methods and Costs of Perpetuating UMNO Rule. Available at SSRN 3048551 .

- Bersih (Ed.). (2018, December 1). The way forward for free & fair elections – Kofi Annan Foundation. Bersih 2.0. Retrieved October 24, 2022, from https://www.kofiannanfoundation.org/app/uploads/2021/04/e5d34343-190307_kaf_electoral_reform_roundtable_en_version_web_version.pdf

- James Chai (2022). The Paradox of Malaysia’s Lowering of Voting Age – Expanded Enfranchisement Devalued by More Unequal Representation. ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Ng, SF (2022). Malaysia’s Anti-hopping Law: Some Loopholes to Mull Over. Fulcrum.

- Ding, Iza, & Slater, Dan. (2021). Democratic decoupling. Democratization, 28(1), 63-80.

Related Articles

Mitos Impian Malaysia

Penang Hokkien and its Struggle for Survival

Malay Wedding

The Myth of the Malaysian Dream

A Day in the Life of a Malay Dad

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The latest resources for democracy, right to your inbox. Stay up to date with our weekly newsletter.

Democratising democracy in Southeast Asia.

Our manifesto, our process, financial model, transparency, collaborate, institutional access, work with us.

Support the movement by:

Make a donation

Sponsor a membership

Terms and conditions

Privacy Policy

Information for Contributors

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

- Invite this member to groups

- Message this member

- Add this member as a connection

Please note: This action will also remove this member from your connections and send a report to the site admin. Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

- Media Freedom Project

- SOGIESC-Informed Democracy

- Principles of Democracy

- The Citizens’ Agenda

- Community Corner

- Collective Care

- Democracy Classrooms

- Citizens, Convene!

New Naratif is a member-based community-building organisation to democratise democracy in Southeast Asia.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

The Nut Graph

Making Sense of Politics & Pop Culture

Malaysia’s electoral system

February 11, 2013

FREE and fair elections are essential to a democratic system of governance. Citizens have the right to choose who they want to govern them, and elections are a way for voters to hold those they elect accountable.

Malaysians choose representatives for two levels of governance – Members of Parliament (MPs) at the federal level and state assemblypersons in the state legislative assemblies.

Under the constitution, the maximum term of the Dewan Rakyat is five years, after which it is automatically dissolved and elections are held. Usually, the Dewan Rakyat is dissolved before its five-year term is complete. This happens when the prime minister advises the Yang Di-Pertuan Agong (YDPA) to dissolve Parliament, and the YDPA decides to do so.

Once Parliament is dissolved, a general election must be held within 60 days.

How do elections take place?

The Election Commission (EC) runs the election process. Under the constitution, the primary function of the EC is to conduct elections to the Dewan Rakyat and the state legislative assemblies. The EC also prepares and revises the electoral roll for elections. It is also further responsible for reviewing the division of constituencies and recommending changes. The EC should be a nonpartisan entity.