75+ Analogy Examples [in Sentences]

- Figurative Language

- Published on Sep 19, 2021

- shares

Analogy is a rhetorical device that says one idea is similar to another idea, and then goes on to explain it. They’re often used by writers and speakers to explain a complex idea in terms of another idea that is simpler and more popularly known.

This post contains more than 75 examples of analogies, some of which have been taken from current events to give you a flavor of how they’re used in real-world writing, some from sayings of famous people, and some are my own creation. They’ve been categorized into two types:

- Analogies with proportionate relationship

- Other analogies

To get the most of these examples, notice how unlike the two things being compared are and, in the second type, how the explanation goes.

(Note: Comments that go with examples are in square brackets.)

More resources on analogy:

- What is analogy and how to write its three types?

- People often confuse analogy with metaphor and simile. Learn how metaphor, simile, and analogy differ

1. Analogies with proportionate relationship

1 . What past is to rear-view mirror, future is to windshield.

2 . What Colorado is in the canyon, Jack is in exams. Both run through the stretch quickly.

3 . What Honda Accord is to cars in 2021, Internet Explorer is to web browsers in 2021. Microsoft did well to finally pull the plug on its browser.

4 . What Monday morning is to me, regular vaccines is to my dog. We both don’t look forward to them.

5 . I’m as uncomfortable in taking a swim as a lion is in taking a climb to a tree.

6 . What dredging machine is to small earthwork, sledgehammer is to cracking walnuts.

7 . I’m as jittery facing a potentially hostile audience as an old man facing a snowstorm.

8 . My father is attracted to jazz as much as iron filings are attracted to magnet. Come what may, he’ll find a way to attend a performance in the town.

9 . Loan sharks are feasting on poor villagers by extracting exorbitant interest rates, in much the same way as vultures feast on carcass.

10 . Famished, we patiently waited for the freshly baked pizza and, when it arrived, pounced on it like grizzly bears pounce on salmons.

Here are few analogies by famous writers and public figures:

11 . As smoking is to the lungs, so is resentment to the soul; even one puff is bad for you. Elizabeth Gilbert

12 . MTV is to music as KFC is to chicken. Lewis Black

13 . He is to acting what Liberace was to pumping iron. Rex Reed on Sylvester Stallone

14 . Armstrong is to music what Einstein is to physics and the Wright Brothers are to travel. Ken Burns

15 . Super Bowl Sunday is to the compulsive gambler what New Year’s Eve is to the alcoholic. Arnie Wexler

16 . He was to ordinary male chauvinist pigs what Moby Dick was to whales. Robert Hughes on Pablo Picasso

17 . College football is a sport that bears the same relation to education that bullfighting does to agriculture. Elbert Hubbard

18 . Football is to baseball as blackjack is to bridge. One is the quick jolt; the other the deliberate, slow-paced game of skill. Vin Scully

19 . It has been said that baseball is to the United States what revolutions are to Latin America, a safety valve for letting off steam. George Will

20 . The sound byte is to politics what the aphorism is to exposition: the art of saying much with little. Charles Krauthammer

21 . Ricardo Montalban is to improvisational acting what Mount Rushmore is to animation. John Cassavetes

22 . To be an American and unable to play baseball is comparable to being a Polynesian and unable to swim. John Cheever

23 . Freedom of the press is to the machinery of the state what the safety valve is to the steam engine. Arthur Schopenhauer

24 . The Christian Coalition has no more to do with Christianity than the Elks Club has to do with large animals with antlers. Garrison Keillor

25 . If facts are the seeds that later produce knowledge and wisdom, then the emotions and impressions of the senses are the fertile soil in which the seed must grow. Rachel Carson

26 . The president of the United States bears about as much relationship to the real business of running America as does Colonel Sanders to the business of frying chicken. J. G. Ballard

2. Other analogies

27 . More books and tuitions don’t translate into more learning just as a fire hose in place of water dispenser doesn’t translate into more drinking capacity.

28 . Although online trolling is rampant, few thoughtful and well-meaning comments also get posted. How to go about responding to them? Propagate helpful comments by retweeting, liking, or leaving your reply. Ignore the trolls. This is quite similar to how we fan or extinguish a fire. Pour gasoline, and it’ll propagate. Starve it of oxygen, and it’ll die.

29 . Entrepreneurs who are working on projects such as generating energy through fusion reaction, the method that powers our sun, and inter-planetary travel are furrowing a new path. That’s like driving on an alien terrain full of surprises with no taillight to follow.

30 . It’s not easy building a business from scratch. That’s why most entrepreneurs after exiting their first company rather invest in other ventures. It’s easier to pour gasoline on a fire than starting a new fire.

31 . Do you want to work on the fringes, do odd jobs? Or do you want to join an organization and make impact? You can remain a pirate or join a navy. Choice is yours.

32 . When the leak in the pipe was repaired, I was surprised at the high flow of water. It meant that the pipe was leaking for months and got detected only when it burst, stopping the flow completely. In much the same way, bad habits creep into our lives almost imperceptibly, with us hardly noticing it till they culminate in a mishap.

33 . Depression is like the common cold. You don’t realize how underappreciated breathing is until you have a cold, and your nose is stuffed, and all you want to do is be able to take a deep breath. That’s what it feels like to have depression. I just want to be able to breathe again. I just want to feel okay. Source

34 . When I think about the effect of software, I equate it to water. Both are basic necessities. Both defy borders and generally go where they want to go. Both need to be protected and both need to be understood. They are critical resources that will always be central to success, and it is readily apparent when either is absent. We easily understand what it is like to be thirsty, and many are finding out what it is like to be digitally unaware. Both are extremely uncomfortable. Source

35 . The vaccine situation in India is like arranged marriage. First, you’re not ready, then you don’t like any, and then u don’t get any. Those who got are unhappy thinking may be the other one would have been better. Those who did not get any are willing to get anyone. Source

36 . Money is like manure. If you spread it around, it’s useful, and everything around you starts greening. If you leave it lying in a pile, it starts stinking quite quickly. Source

37 . Time for negotiations and beating around the bush is over; we need to take hard steps now. It’s time to give up scalpel and bring in hammer.

38 . We all want precise, quick, actionable solutions to solve the challenges life throws at us. However, answers to life’s challenges don’t come in bullet points. Such answers are hazy and often come in paragraphs.

39 . Ever had gum stuck on your hair. Icky, isn’t it. That’s what sight of a centipede or an earthworm does to me.

40 . While reading, a reader needs to slow down somewhat to comprehend a sentence that lacks parallel structure. Don’t we slow down when we encounter a speed bump on an otherwise smooth road? [Comment: I’ve used this and the next analogy in my post on parallelism. If you can think of a compelling thing to compare with, analogies aren’t difficult to pull off.]

41 . Just as you need two straight lines to even consider the concept of parallel lines, you need two elements in a sentence to even consider the concept of parallelism in a sentence.

42 . While their mother was away, the two leopard cubs escaped wild dogs by remaining standstill, camouflaging perfectly with the rocks in the background. Clearly, the two cubs, barely two months old, had been learning only what matters in the real world – escaping predators and hunting. In contrast, we humans learn myriad of subjects in school and college, of which only a tiny portion matters in the real world.

43 . Like the deadly fog that envelopes the region, affecting normal life for many days, global warming has emerged as the envelope of the entire planet, wreaking untold harm on the earth’s inhabitants.

44 . People gain wisdom little by little through experience, but that’s highly inefficient. You can gain wisdom much faster by learning from others’ mistakes, by receiving advice from mentors, and by reading books which have documented every possible human success and failure. Isn’t that akin to filling a bucket by a dripping tap when you can fill it much faster by opening the tap fully.

45 . You may have the required qualification and skills for a job, you may have mentors to guide you every step of the way, and you may have the best colleagues. But all this means nothing if you’re in the wrong job. It’s like having the best vehicle for a journey and friendliest co-passengers, but heading in a direction different from your destination.

46 . Government has invested so much of taxpayer’s money into the state-owned airline but to no avail. It hasn’t shown profits in nearly ten years. Is it any different from spraying fertilizer on weeds and deadwood?

47 . Trying ten pilot projects to zero in on our new product is quite resource heavy. Instead, we should try maximum 2-3 pilots based on a strong hypothesis. We can’t waste bullets through shotgun fire; we need sniper fire.

48 . None of your business ideas have worked so far because you haven’t thoroughly tested key assumptions in your business model. You’re in a way constantly shooting in the dark, hoping to find the target.

49 . You should stay in this project for few more weeks and complete it. Otherwise, your successor might get the credit for the completed project even though you’ve done bulk of the work. You’ll lay the eggs that others will hatch.

50 . With his skills, he’ll be better suited in marketing than in sales. You can’t put a square peg in a round hole.

51 . The fish asked the two passing subadult fish, “How’s the water?” The two subadult fish quizzically ask each other, “What’s water?” Like the fish don’t know what water is because it’s such an indistinguishable part of their life, we don’t see our frailties because they’re such an indistinguishable part of our lives.

52 . In the division of business empire between the feuding siblings, the sister got the steady cash-generator of a company. The others landed less attractive assets. That was like the sister skimming the cream and leaving double-toned milk for the brothers.

53 . He performed so well in the interview that he topped the exam despite poor performance in the written test. Imagine Usain Bolt winning 100-meter dash despite starting the race ten meters behind others.

54 . Industries such as online retail have such thin margins that an odd adverse event may turn a quarter from profit to loss. Life in the wild for predators is no different. A timely kill, or lack of it, can be the difference between fasting and feasting.

55 . By the time court ordered a stay on demolition order of the municipal body, the building was razed down. That was like conducting a successful organ transplant but failing to save the patient.

56 . Our program helping students boost their brain power didn’t take off. Our program helping struggling students did much better though. Isn’t it easier to sell aspirin than vitamin?

57 . When the leak in the pipe was repaired, I was surprised at the high flow of water. It meant that the pipe was leaking for months and got detected only when it burst, stopping the flow completely. In much the same way, bad habits creep into our lives almost imperceptibly, with us hardly noticing it till they culminate in a mishap.

58 . Public companies can find it challenging to reinvent themselves and make breakthrough progress because of constant pressure to keep short-term results clean. That’s why sometimes companies go private, Dell being an example, to discover their mojo away from the pressures a public company faces. I did something similar as an individual. For a year, I retreated from most time-wasters and social activities, tried multiple things, and found the career path I wanted to take.

59 . The marketing head proposed six marketing channels to pursue to increase brand awareness, possibly playing safe. Throw enough spaghetti against the wall and some of it will stick.

60 . When the company decided to disband the post because of inadequate work, the person-to-be-effected justified its continuance, citing the important functions the post served. Ask a man whose job is to shoo flies about the importance of his job, and he’ll say that he is saving humanity. We all think ours is the most important job.

61 . People underestimate how quickly they can become an expert in a field if they keep on improving and keep putting in the hours on their skill. It’s like how fast money multiplies when it accrues interest in a bank.

62 . If your content features on the second page of search result on Google, no one is going to find it. That’s like a murderer hiding a dead body at a place where no one can detect it.

63 . Just like one should cross a stream where it is shallowest, a company should enter that segment of a market where it has some advantage or where competition is less.

64 . Just as people don’t heed to health warning prominently displayed on cigarette packets and smoke, people don’t learn basic workplace skills despite knowing that lack of these skills affect their chance of landing a good job.

65 . The businessman, who hoodwinked several unsuspecting people with his suave manners and forged pedigree, was finally arrested. What many thought to be a promissory note turned out to be a dud cheque.

66 . Just as a cautious businessman avoids investing all his capital in one concern, so wisdom would probably admonish us also not to anticipate all our happiness from one quarter alone. Sigmund Freud

67 . Criticism may not be agreeable, but it is necessary. It fulfils the same function as pain in the human body. It calls attention to an unhealthy state of things. Winston Churchill

68 . It is with books as with men; a very small number play a great part; the rest are lost in the multitude. Voltaire

69 . A truly great book should be read in youth, again in maturity, and once more in old age, as a fine building should be seen by morning light, at noon, and by moonlight. Robertson Davies

70 . It is with narrow-souled people as with narrow-necked bottles: the less they have in them, the more noise they make in pouring it out. Jonathan Swift

71 . Adversity has the same effect on a man that severe training has on the pugilist: it reduces him to his fighting weight. Josh Billings

72 . The lights of stars that were extinguished ages ago still reach us. So it is with great men who died centuries ago, but still reach us with the radiations of their personalities. Kahlil Gibran

73 . As the internal-combustion engine runs on gasoline, so the person runs on self-esteem: if he is full of it, he is good for the long run; if he is partly filled, he will soon need to be refueled; and if he is empty, he will come to a stop. Thomas Szasz

74 . I don’t like nature. It’s big plants eating little plants, small fish being eaten by big fish, big animals eating each other. It’s like an enormous restaurant. Woody Allen

75 . The human mind treats a new idea the same way the body treats a strange protein; it rejects it. Peter B. Medawar

76 . I go to books and to nature as a bee goes to the flower, for a nectar that I can make into my own honey. John Burroughs

77 . Trickle-down theory – the less than elegant metaphor that if one feeds the horse enough oats, some will pass through to the road for the sparrows. John Kenneth Galbraith

78 . A man should live with his superiors as he does with his fire; not too near, lest he burn; not too far off, lest he freeze. Diogenes

79 . We must be willing to get rid of the life we’ve planned, so as to have the life that is waiting for us. The old skin has to be shed before the new one can come. Joseph Campbell

80 . Relationships are hard. It’s like a full-time job, and we should treat it like one. If your boyfriend or girlfriend wants to leave you, they should give you two weeks’ notice. There should be severance pay, and before they leave you, they should have to find you a temp. Bob Ettinger

Anil is the person behind this website. He writes on most aspects of English Language Skills. More about him here:

What Is Analogy and How to Use It in Your Essay

Table of contents

- 1 Types of Analogies

- 2 How Does Analogy Compare and Enhance Writing?

- 3 Metaphor and Simile: Cornerstones of Analogy (What This Greek Word Means?)

- 4 Crafting Effective Analogies Eight Steps Guide

- 5 Polishing Your Writing Style With Analogy Examples

Analogy is a literary technique that compares related or unrelated concepts, events, or notions to one another. Before writing an analogy, you should know that this concept can implement other literary devices like metaphors or allegories.

This article sets the stage for exploring the diverse landscape of analogical writing.

As you progress, you will also:

- Define examples of analogies and discover how they elevate your essay-writing skills.

- You will learn how analogy enhances essay writing and why it can help you improve your style.

- Examine and master the use of metaphor and simile.

- Master an eight-step PapersOwl guide to learn how to craft effective analogies quickly.

Before we proceed with practical examples and dive deep into theory, let’s start with the analogy definition.

Definition of Analogy in Writing

An analogy in essay writing represents a description that compares this to that by simplifying a certain idea. What you compare may have or may not have similarities. The use of comparative language is common for an analogy. One may encounter phrases like “experienced like an old dog” or “writing essays as a busy working bee.” An analogy general idea can be made between what a young child can do and what modern computers can generate. You can compare and persuade. Likewise, a persuasive essay author can provide an analogy between a youngster and artificial intelligence.

Analogy’s purpose is to draw comparisons and a more detailed image with a clearer description. When an unknown concept is represented, literal analogies bring more clarity. When you are asked to create a connection between unrelated concepts, analogies become helpful. When you encounter metaphors, similes, or allegories, it indicates their practical use.

Types of Analogies

Speaking of types of analogies in writing, one should focus on various types of relations.

- Analogies that identify identical relationships . These analogy examples are most common as they talk about related concepts. It is like Los Angeles to the United States or guitar to piano. By learning how to write an analogy, one can see the relation between the same country or the musical instrument analogy.

- Analogies that identify shared abstraction. An analogy of figurative language stands for shared abstractions comparing something unrelated. It aims to find commonalities or patterns that make sense. Such cases can compare learning a foreign language to watering seeds that grow into flowers as time passes. Since it is the journey, not the destination, it helps to understand the abstractive language.

- A relation of a certain part to something whole analogy . It is a comparison of two sets of the same object or two parts of the same concept.

- Cause-and-effect relation analogy. It speaks of causes like the lack of water, which causes dehydration.

- Source to product. Think about the wood and the piano manufacturing common analogies.

- Object and a clear purpose. This one can talk about books and reading or water and swimming.

- Comparison of typical characteristics. If something is essential for an object, it becomes the source of the analogy between them.

- Coming from something general to specific parts. You can make an analogy by offering a good detective book by comparing two or more things.

- Metaphors and Allegories. These elements of an analogy in poetry add creativity and literary power, like being tired as a dog or feeling hungry like a wolf.

Tip: Using literal analogies can enhance your writing by building a strong connection between concepts. For example, when you need to provide a literature analysis essay assignment, you use the creativity and imagination of the author by seeking analogies, among other things.

How Does Analogy Compare and Enhance Writing?

The most important element of using analogy examples in your essay is its enhancement. From clarity to a better description, it offers a mental bridge to the readers. If something in an essay is obscure or complex, an analogy makes it easier to understand demanding concepts.

- Creating Vivid Mental Images.

An analogy compares things and shows a way to help people understand things. When we compare raising children to building a house brick after brick, we receive an instant mental image. Similarly, adding creative writing to an essay helps to enhance the emotional state of things.

- Simplifying Complex Concepts.

Analogy examples help to simplify things that are overly complicated and demanding. It can be used in engineering or healthcare when a certain action is compared to what people know in practice. Likewise, comparing chemical aspects of work to cooking or culinary and human taste can help to simplify things. It is a practical example that gives people more accessible things they can easily connect with.

- Using Analogy to Influence and Convince.

An analogy compares marketing and business writing concepts when the main purpose is to motivate customers. The same is true when the author has to convince. Think about social or environmental causes where cause-and-effect rhetorical devices can become a turning point for readers. A good comparison with a logical argument can help inspire and simplify things, even in marketing. Due to their explanatory nature, analogies are common in argumentative writing essays or school debates.

- Rhetorical Devices and Analogy.

Most analogies represent rhetorical devices, as we should use at least one type of comparison. Still, it does not work the same way as similes or metaphors that deal with resemblance aspects. A correct example will seek parallels between things that are not obvious or connected in one way or another. When used for an essay assignment, it will add rhetoric to help readers determine what common qualities can be established based on what is not apparent at first glance.

- Analogy in Different Genres.

When you are asked to use examples of analogies for a school essay, the trick is to determine the main purpose and use it correctly. It means that using an analogy in a detective story is not the same as using it for marketing purposes. The same applies when an author must classify different objects for analogy in literature. Likewise, a problem-and-solution analogy can be used in education or to deliver a similar concept. If we choose history books, we can provide old and modern analogies that help us understand historical concepts more clearly.

Metaphor and Simile: Cornerstones of Analogy (What This Greek Word Means?)

Metaphors and similes represent the main cornerstones of the use of an analogy. Take a quick look at several academic essays related to social or literary subjects, and you will most definitely encounter at least one case. Writers use metaphors to compare something or use them for a specific effect. The tricky part is that a simile is a special sub-category of a metaphor, which shows that most similes are parts of metaphors, yet not the other way around. Let’s identify each case!

A metaphor (from the Greek word “to transfer”) represents a figure of speech that aims to compare things to achieve a specific rhetorical effect. A good example would be saying that the world is a stage or that people in love represent an endless ocean of love. Of course, metaphors are not meant to be taken literally!

A typical simile will create a different type of comparison by implementing the words “like” and “as” in writing. The most famous example of a simile in writing would be the phrase “Life is a beach.” One can spot it by using a direct comparison. It must be used with caution or have an additional explanation. Remember that examples of an analogy should show and explain things, which is why a simile or a metaphor can be used.

- Identifying the Main Differences.

Summing up regarding distinctions for writing analogies, we receive the following five rules:

- A simile aims to show that something is like some other object.

- A metaphor literary device uses poetical writing to say something is another thing.

- The purpose of analogy is to offer an additional explanatory point, not merely show.

- Metaphors and similes can work for an enhancement effect when using an analogy in essay writing.

- A simile is a special subgenre of metaphors, yet not all metaphors are similes.

Crafting Effective Analogies Eight Steps Guide

Making an analogy efficient and fitting always comes down to the practical clarity of a certain description. Depending on the genre, start by analyzing your target audience to make things more accessible. If there’s a concept, think about the main elements and see what is most relevant.

- Analyze the Target Concept. Start with a proper analysis of the main concept that you outline in your essay. If you are dealing with medical practices, do not create analogies that do not fit. Keep within high morals and be sensitive. If you are composing a reflective essay, some types of analogy can be related to your past or certain experiences from your life. These should help people understand you in a better way.

- Choosing the Concept for Explanation . When you seek diverse types of analogies, think about a concept that can be used for explanatory purposes. It means that you may use historical books or comparisons to certain movies or events that have taken place before. For example, you may consider comparing a business deal to Boston’s Tea Ceremony or woodworking to learning how to play guitar well.

- Highlight Relevant Similarities. Although analogies in literature are always about seeking similarities, not all will remain clear to your readers. Therefore, one should focus on relevant similarities and highlight them the best way you can. If you state that our world is like a theater where all of us are merely actors, it should not come out of the blue but have an explanation as you quote William Shakespeare’s words.

- Forming the Basis of the Analogy. Before you add it to your essay, think about making an introduction. An analogy never comes on its own because it requires a special paragraph that highlights it and leads to an emotional climax. Once you have got what is an example of an analogy, add more analytical writing or an explanatory sentence to help your readers see your point more clearly.

- Illustrating the Analogy with Real-World Situations. An analogy sentence that does not make sense will not work. The trick is to help people connect and see how your example can be used in practice. When you say that working at Tesla corporation was like surviving Arizona’s heatwave, most Americans will be able to relate to that.

- Adapting the Analogy to Audience Knowledge. When your analogy is overly complex and relates to engineering or law essay writing, you may not achieve success with that. Remember to adapt your comparison to the level of your target audience. The key is to make things accessible and ensure that you are understood.

- Ensuring Natural Fit and Relevance. It is best to use your analogy in the middle of a paragraph. This way, you can add a special introduction and make it fit naturally. It should fit within a relevant paragraph, making it apparent to avoid using analogies as the final sentence. More space is essential since you must add transition words in an essay.

- Weaving Analogies into the Narrative. Use an analogy to show and explain a certain concept or idea. Use the same narrative tone if your essay is written this way. Adjust your writing accordingly if you use an explanatory or argumentative tone.

Polishing Your Writing Style With Analogy Examples

Coming up with a good analogy may seem challenging, especially when you must get the essay done at the last minute or when you are unsure about the emotional power of your writing. Using an analogy in writing helps you improve things and add clarity, even to the most complex subjects. Refer to the eight-step writing guide above before you start, and don’t forget to double-check existing analogy types! Lastly, remember the importance of balancing active and passive voice as you explain and use various literary devices to enhance your writing further.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

AI Generator

“He’s as strong as an ox” and “Navigating her emotions is like walking through a maze” are examples of analogies, a common method of comparison in the English language. Analogies are not only prevalent in literature and writing but also in everyday speech, serving as an effective tool for communication. They involve comparing two different things or ideas, which helps clarify or emphasize a point. This literary term, known as an analogy, encompasses various types of comparisons, making it a key element in both formal and informal expression.

Like any other literary analysis sample device, Analogy is used in enhancing the meaning of a composition and is also used in helping the readers in creating a visual image in their minds as well as relationships goals and connections when they would read something difficult or sensitive by comparing one thing to the other. Analogies are often used in thesis , essay writing , report writing , and even in speeches .

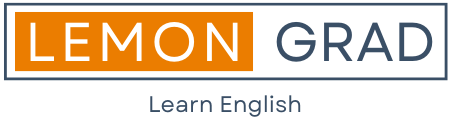

What is an Analogy? – Definition An analogy is a comparison between two different things, intended to highlight some form of similarity. It’s a linguistic technique used to explain a new or complex idea by relating it to something familiar. Analogies are often used in teaching, writing, and speaking to make concepts easier to understand. They draw parallels that help people visualize and grasp the essence of the subjects being compared, thereby enhancing comprehension and retention.

Examples of Word Analogies

Analogies are crucial in language and thinking, comparing different concepts to enhance understanding. They are used in education to simplify complex ideas, in standardized tests to assess reasoning skills, and in job interviews to evaluate problem-solving abilities. Additionally, analogies enrich literature and daily communication. Examples like comparing pens to brushes or the sun to planets demonstrate how analogies illuminate various subjects, making them more accessible and relatable.

- Relationship in First Pair : A pen is a tool used for writing.

- Application to Second Pair : Similarly, a brush is a tool, but it is used for painting.

- The analogy connects the function of each tool with its primary action.

- Relationship in First Pair : The sun is a central part of our solar system.

- Application to Second Pair : In a broader scope, a planet is part of a galaxy, which is a larger system of celestial bodies.

- This analogy scales from a smaller celestial relationship (sun and solar system) to a larger one (planet and galaxy).

- Relationship in First Pair : A teacher is the guiding authority in a classroom.

- Application to Second Pair : Similarly, a captain is the guiding authority on a ship.

- The analogy compares the roles of authority and guidance in different settings.

- Relationship in First Pair : A clock is an instrument used to measure and indicate time.

- Application to Second Pair : In a similar vein, a thermometer is an instrument used to measure and indicate temperature.

- This analogy connects the function of measuring and indicating specific elements (time and temperature) with their respective instruments.

- Relationship in First Pair : A book is an individual item that is part of a collection in a library.

- Application to Second Pair : Similarly, a piece of art is an individual item that forms part of a collection in a gallery.

- The analogy shows the relationship of individual items (books, art) as components of larger collections (library, gallery).

- Leaf : Tree :: Wave : Ocean It compares the part-to-whole relationship of a leaf to a tree and a wave to an ocean.

- Author : Novel :: Composer : Symphony This analogy highlights the relationship between an author and their creation, a novel, to a composer and their creation, a symphony.

- Doctor : Hospital :: Teacher : School It parallels the role of a doctor in a hospital to that of a teacher in a school.

- Key : Piano :: String : Guitar This analogy compares the function of a key on a piano to a string on a guitar.

- Nurse : Healthcare :: Lawyer : Law Here, the analogy shows the relationship of a nurse to the field of healthcare and a lawyer to the field of law.

More Analogy Examples for You to Solve

- Owl : Night :: Eagle : _______ (Hint: Consider the time of day each bird is most active.)

- Library : Books :: Museum : _______ (Hint: Think about what a museum houses.)

- Novelist : Words :: Painter : _______ (Hint: Focus on the primary medium used by each artist.)

- Teacher : Educate :: Chef : _______ (Hint: What is the primary action a chef performs?)

- Fish : School :: Wolf : _______ (Hint: Consider the term for a group of these animals.)

- Piano : Music :: Telescope : _______ (Hint: What does a telescope help us explore?)

- Rain : Cloud :: Lava : _______ (Hint: Where does lava originate?)

- Heart : Circulate :: Lungs : _______ (Hint: Think about the primary function of lungs.)

- Leaf : Photosynthesis :: Root : _______ (Hint: Consider the main function of roots in a plant.)

- Baker : Bakery :: Librarian : _______ (Hint: Where does a librarian work?)

- Clock : Time :: Scale : _______

- Ocean : Saltwater :: Lake : _______

- Flower : Garden :: Book : _______

- Knife : Cut :: Screwdriver : _______

- Fire : Heat :: Snow : _______

- Poet : Poem :: Musician : _______

- Bird : Nest :: Bee : _______

- Tree : Oxygen :: Sun : _______

- Actor : Stage :: Athlete : _______

- Shoe : Foot :: Glove : _______

- Phone : Call :: Computer : _______

- Rain : Umbrella :: Sun : _______

- Leaf : Green :: Sky : _______

- Baker : Bread :: Winemaker : _______

- Painter : Portrait :: Writer : _______

- Doctor : Patient :: Teacher : _______

- Fisherman : Fish :: Miner : _______

- Keyboard : Type :: Mouse : _______

- Car : Garage :: Airplane : _______

- Map : Location :: Calendar : _______

Examples of Analogies for Critical Thinking

- Just as a garden is a space where flowers grow and flourish, the mind is a space where ideas are cultivated and developed. This analogy emphasizes the nurturing and growth aspects in both scenarios.

- A book opens the door to knowledge, much like a key unlocks a door. This analogy highlights the unlocking and revealing nature of a book, providing access to new information and understanding.

- A telescope enables us to see distant stars, while a microscope allows us to view tiny bacteria. This analogy draws a parallel between the tools we use to explore vastly different scales of our universe, from the vast to the microscopic.

- Just as a foundation provides stability and support for a building, roots offer support and nourishment to a tree. This analogy compares the underlying support structures in architecture and nature.

- In poetry, words are woven together to create emotional and intellectual art, just as colors are blended in a painting to create a visual masterpiece. This analogy compares the elements of creation in different forms of art.

- A chef uses a recipe to create a dish, just like a composer uses a musical score to create a symphony.

- An author crafts stories with a pen as a sculptor shapes sculptures with a chisel.

- Fire is a source of warmth, as ice is a source of coolness.

- A clock measures time like a thermometer measures temperature.

- Trees produce oxygen, and clouds produce rain.

More Examples for you to Solve:

- Helmet : Head :: Gloves : _______ (Hint: Consider what gloves protect.)

- Sponge : Absorb :: Sieve : _______ (Hint: Think about what a sieve does with liquids.)

- Caterpillar : Butterfly :: Tadpole : _______ (Hint: Consider the lifecycle transformation.)

- Magnet : Attract :: Repellent : _______ (Hint: Think of the opposite action of attracting.)

- Flashlight : Darkness :: Air Conditioner : _______ (Hint: What does an air conditioner alleviate?)

- Furnace : Heat :: Refrigerator : _______ (Hint: Think about what a refrigerator preserves.)

- Anchor : Ship :: Brakes : _______ (Hint: Consider what brakes do to a vehicle.)

- Recipe : Dish :: Blueprint : _______ (Hint: What is created using a blueprint?)

- Vaccine : Disease :: Fertilizer : _______ (Hint: Think about what fertilizer promotes.)

- Lighthouse : Ships :: Traffic Light : _______ (Hint: Consider what traffic lights guide.)

- Archive : Documents :: Museum : _______

- Rudder : Direction :: Engine : _______

- Thermometer : Temperature :: Barometer : _______

- Author : Story :: Composer : _______

- Nest : Bird :: Den : _______

- Broom : Sweep :: Hose : _______

- Window : Light :: Dam : _______

- Dew : Morning :: Frost : _______

- Key : Lock :: Code : _______

- Easel : Painter :: Anvil : _______

Analogy Examples in Sentence

- Life is like a box of chocolates; you never know what you’re going to get. This analogy compares the unpredictability of life with the surprise of picking a chocolate from an assorted box.

- The heart of a car is its engine. This draws a parallel between the essential role of the heart in the human body and the engine in a vehicle.

- A good book is a magic gateway into another world. Here, the transformative power of reading is likened to a portal leading to new, undiscovered realms.

- The classroom was a zoo. This analogy suggests the noisy and chaotic nature of the classroom, similar to the lively environment of a zoo.

- Her eyes were windows to her soul. This sentence compares eyes to windows, implying that they reveal deep emotions or the essence of a person.

- Time is a thief. This analogy implies that time steals moments from our lives, much like a thief takes away possessions.

- The computer in the modern age is like a pen in the past. This draws a comparison between the role of computers today in communication and creation, and the role of the pen in earlier times.

- The moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas. This vividly portrays the moon as a ghostly ship sailing across the sky, with clouds as its sea.

- The world is a stage, and we are merely players. This famous analogy from Shakespeare suggests that life is like a play, and everyone has a role to perform.

- Watching the show was like walking through a dream. This suggests the surreal, dream-like quality of the show, likened to the experience of walking through a dream.

Examples of Analogy in Literature

Analogy is a common literary device used by authors to draw comparisons between two different things, often to highlight a particular theme or idea. Here are some examples of analogy in literature:

- This famous analogy compares the world to a stage and life to a play, suggesting that our lives are structured like a theatrical performance, with different roles and acts.

- Orwell uses farm animals to represent historical figures and social classes, drawing parallels between the farm’s descent into tyranny and the history of Soviet communism.

- Here, the prejudice and racism in Maycomb are compared to a disease, suggesting they are both harmful and spread uncontrollably.

- The diverging paths symbolize life’s different options and directions, and the choice of path represents a decision that shapes one’s future.

- In this analogy, experiences are likened to physical parts of a person, suggesting that they become integral to one’s identity.

Types of Analogy

- Literal Analogy : Compares two similar things or classes of things that have the same relationship. For example, “Just as a sword is the weapon of a warrior, a pen is the weapon of a writer.”

- Figurative Analogy : Involves a comparison between two things that are different in nature, often used to explain a concept or to persuade. For instance, comparing the mind to a computer.

- Relational Analogy : Focuses on the relationship between pairs of words. For example, “Hand is to glove as foot is to sock.” The relationship is about things that cover.

- Personal Analogy : Requires imagining oneself as an object or a situation. It’s often used in problem-solving to look at things from a different perspective.

- Predictive Analogy : Used to predict the outcome of some actions by comparing it to known outcomes in similar scenarios. For example, “If you overwater a plant, it dies; similarly, too much of anything, even a good thing, can be harmful.”

- Analogical Argument : Used in persuasive writing and speech, where an analogy is used as an argument or as a part of an argument.

- Negative Analogy : Focuses on comparing dissimilarities between two things. For example, “Arguing on the internet is unlike a sports competition; there are no clear winners.”

- Medical Analogy : Common in medical fields, where symptoms or conditions of a patient are compared to typical cases to diagnose or treat.

- Historical Analogy : Draws a comparison between historical events to explain or predict current events. For example, comparing modern political situations to historical ones.

- Mathematical Analogy : Involves comparing mathematical relationships, often used in teaching complex mathematical concepts.

How to Write an Analogy

- Identify the Core Idea or Concept : Begin by determining the main idea or concept you want to explain or enhance through the analogy.

- Find a Relatable Comparison : Choose a familiar or easily understandable object, situation, or concept that shares similarities or relationships with your core idea.

- Establish a Clear Relationship : Ensure that the relationship between the two entities in your analogy is clear and logical. The comparison should highlight the similarities or explain the concept effectively.

- Use Simple and Effective Language : The effectiveness of an analogy often lies in its simplicity. Use language that is easy to understand and avoids complexity.

- Be Consistent : Maintain consistency in the elements of your analogy. Mixing different metaphors or comparisons can lead to confusion.

- Test Your Analogy : Before finalizing, test your analogy to see if it makes the concept clearer and is understandable to your intended audience.

When to Use Analogy

- To Simplify Complex Ideas : Analogies are excellent for breaking down complex or abstract concepts into simpler, more relatable terms.

- In Teaching and Education : They are used to explain new or difficult subjects by relating them to something familiar to the students.

- To Persuade or Argue : In rhetoric and writing, analogies can make arguments more persuasive by drawing parallels that the audience can easily understand.

- To Enhance Writing : Writers often use analogies to add depth, creativity, and imagery to their writing, making it more engaging and vivid.

- In Problem-Solving : Analogies can help in seeing problems from a new perspective, leading to innovative solutions.

How Does Analogy Work

- By Establishing Relationships : Analogies work by drawing a parallel between two disparate entities, emphasizing their similarities in relation to each other.

- Through Familiarity and Understanding : They often use familiar concepts to explain unfamiliar ones, making new or complex information more digestible and easier to grasp.

- Creating Mental Images : Good analogies create vivid mental images, which can be more effective in communication than abstract concepts.

- Enhancing Memory and Retention : Because they often involve storytelling or imagery, analogies can be more memorable than straightforward explanations, aiding in better retention of the information.

- Building on Prior Knowledge : Analogies leverage the audience’s existing knowledge or experience, providing a foundation for understanding new information.

Analogies, when used effectively, can be powerful tools for communication, learning, and creativity, bridging gaps in understanding by connecting the unknown to the

25 Examples of Analogies

1. life is like a race.

2. Finding a Good Man is Like Finding a Needle in a Haystack

3. Just as a Sword is the Weapon of a Warrior, a Pen is the Weapon of a Writer

4. That’s as Useful as Rearranging Deck Chairs on the Titanic.

5. How a Doctor Diagnoses Diseases are Like How a Detective Investigates Crimes

6. Explaining a Joke is Like Dissecting a Frog

7. Just as a Caterpillar Comes out of its Cocoon, So we Must Come out of our Comfort Zone

8. A Movie is a Roller Coaster Ride of Emotions.

9. You are as Annoying as Nails on a Chalkboard.

10. Life is Like a Box of Chocolates – You Never Know What You’re Gonna Get!

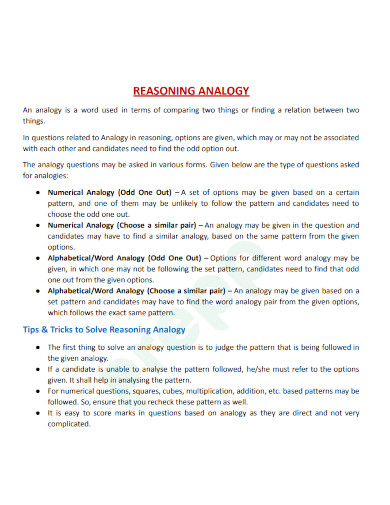

11. Reasoning Analogy

Size: 69 KB

12. Analogy as the Core of Cognition

Size: 108 KB

13. Analogy by Similarity Example

Size: 68 KB

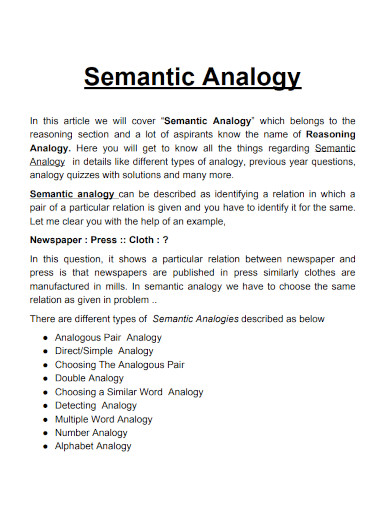

14. Semantic Analogy Example

Size: 74 KB

15. Teaching by Analogy Example

Size: 105 KB

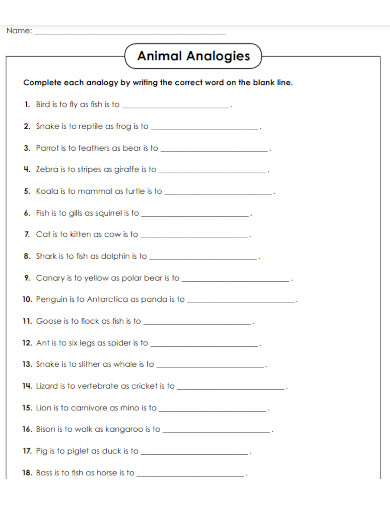

16. Animal Analogies Example

Size: 41 KB

17. The Principle of Analogy

Size: 84 KB

18. Analogy as Exploration

File Format

Size: 62 KB

19. Science Analogy Example

Size: 61 KB

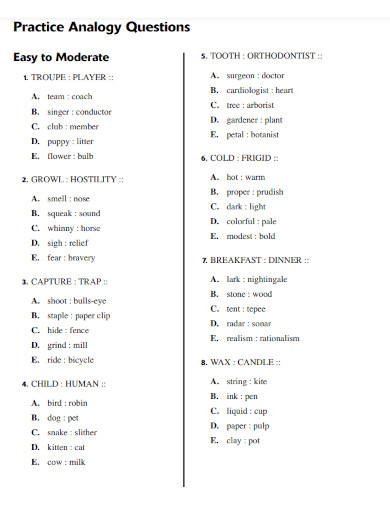

20. Practice Analogy Questions

Size: 46 KB

21. The Reaction Against Analogy

Size: 71 KB

22. Transformational Analogy Example

Size: 64 KB

23. Curve Analogies Template

24. Analogy and Transfer

Size: 109 KB

25. Analogy in Thinking Example

Size: 23 KB

What is an Analogy?

A figurative analogy is used when you compare two completely different ideas or things and use its similarities to give an explanation of things that are hard to understand or are too sensitive. Analogies are often used in thesis , essay writing , report writing , and even in speeches .

Step 1: Identify the Two or More Things You Want to Compare

To start is to identify two or more words or phrases you may want to compare. This is the first step to writing your analogy. You must also be careful with the analogy you are going to be using, if your audiences are children, you can use analogy for kids . The important thing is to be able to explain the idea or the concept.

Step 2: Do Your Research on the Similarities

In order for you to explain and understand the similarities between the words or phrases that you are using for analogy, you must first do your research about it. Simply writing two words together to compare is not enough. It is also important for you to understand what these two words mean and how similar are they in order for them to be compared.

Step 3: Make the Analogies

Make or create the analogies once you have figured out the similarities of the words you have written. If you have not, go back to the second step and continue until you found them. The analogy must be in a simple sentence or a simple statement. Avoid using technical jargon that defeats the purpose of the analogy.

Step 4: Give the Explanation of the Chosen Analogies

The last step is to give out the explanation of the chosen analogies. The explanation will help give the reader the idea of what they are reading and can grasp the information from the analogies. Provided the fact that these chosen analogies details and examples to back it.

What is the difference with analogy, simile and metaphor?

More often than not, an analogy is sometimes mistaken with the other figures of speech examples , namely simile and metaphor , because these are used to seek relationships between concepts and things. The figurative language simile compares two objects that use comparison words such as ‘like’ and ‘as’ where the whole metaphor would compare two objects with the use of the said comparison words.

What are the elements of an analogy?

What you can expect in the elements of an analogy are as follows: the two or more concepts that need to be compared, the shared characteristics of these concepts, the differences of the concepts, the purpose, the clarification, and lastly the creativity.

What is the difference between analogy and idioms?

An analogy is a comparison of two or more things, topics or concepts that helps explain the topic. An idiom is a phrase that has a figurative language or meaning to it.

Analogy compares two completely different things and look for similarities between two things or concepts and it only focuses on that angle. The use and purpose of analogies may baffle any reader at first but once they would realize how analogies can help writers in making difficult and sensitive topics or things understandable, analogies might be used frequently.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

Metaphors and Analogies: How to Use Them in Your Academic Life

Certain Experiences in life can't be captured in simple words. Especially if you are a writer trying to connect with your audience, you will need special threads to evoke exact feelings.

There are many literary devices to spark the readers' imagination, and analogies and metaphors are one of that magical arsenal. They enrich your text and give it the exact depth it will need to increase your readers' heartbeat.

Taking a particular characteristic and associating it with the other not only enriches your text's linguistic quality but gives the reader a correct pathway to deeper layers of a writer's psyche.

In this article, we are going to take a good look at the difference between analogy and metaphor and how to use them in your academic writing, and you will find some of the most powerful examples for each. Learn more about this and other vital linguistic tools on our essay writer service website.

What are Metaphors: Understanding the Concept

Let's discuss the metaphors definition. Metaphors are a figure of speech that compares two unrelated concepts or ideas to create a deeper and more profound meaning. They are a powerful tool in academic writing to express abstract concepts using different analogies, which can improve the reader's understanding of complex topics. Metaphors enable writers to paint vivid pictures in the reader's mind by comparing something familiar with an abstract concept that is harder to grasp.

The following are some of the most famous metaphors and their meanings:

- The world is your oyster - the world is full of opportunities just waiting for you to grab them

- Time is money - time is a valuable commodity that must be spent wisely

- A heart of stone - someone who is emotionally cold and unfeeling

Analogies Meaning: Mastering the Essence

Analogies, on the other hand, are a comparison of two concepts or ideas that have some similarity in their features. They are used to clarify complex ideas or to make a new concept more relatable by comparing it to something that is already familiar.

Analogies are often followed by an explanation of how the two concepts are similar, which helps the reader to understand and make connections between seemingly disparate ideas. For example, in academic writing, if you were explaining the function of a cell membrane, you might use an analogy, such as comparing it to a security gate that regulates what enters and exits a building.

Check out these famous analogies examples:

- Knowledge is like a garden: if it is not cultivated, it cannot be harvested.

- Teaching a child without education is like building a house without a foundation.

- A good friend is like a four-leaf clover; hard to find and lucky to have.

Benefits of Metaphors and Analogies in Writing

Chances are you are wondering why we use analogies and metaphors in academic writing anyway?

The reason why metaphors are beneficial to writers, especially in the academic field, is that they offer an effective approach to clarifying intricate concepts and enriching comprehension by linking them to more familiar ideas. Through the use of relatable frames of reference, these figures of speech help authors communicate complicated notions in an appealing and comprehensible way.

Additionally, analogies and metaphors are a way of artistic expression. They bring creativity and imagination to your writing, making it engaging and memorable for your readers. Beautiful words connect with readers on a deeper emotional level, allowing them to better retain and appreciate the information being presented. Such linguistic devices allow readers to open doors for imagination and create visual images in their minds, creating a more individualized experience.

However, one must be mindful not to plagiarize famous analogies and always use original ideas or appropriately cite sources when necessary. Overall, metaphors and analogies add depth and beauty to write-ups, making them memorable for years to come.

Understanding the Difference Between Analogy and Metaphor

While metaphors and analogies serve the similar purpose of clarifying otherwise complex ideas, they are not quite the same. Follow the article and learn how they differ from each other.

One way to differentiate between analogies and metaphors is through the use of 'as' and 'like.' Analogies make an explicit comparison using these words, while metaphors imply a comparison without any overt indication.

There is an obvious difference between their structure. An analogy has two parts; the primary subject, which is unfamiliar, and a secondary subject which is familiar to the reader. For example, 'Life is like a box of chocolates.' The two subjects are compared, highlighting their similarities in order to explain an entire concept.

On the other hand, a metaphor describes an object or idea by referring to something else that is not literally applicable but shares some common features. For example, 'He drowned in a sea of grief.'

The structural difference also defines the difference in their usage. Analogies are often used in academic writing where hard concepts need to be aligned with an easier and more familiar concept. This assists the reader in comprehending complex ideas more effortlessly. Metaphors, on the other hand, are more often used in creative writing or literature. They bring depth and nuance to language, allowing for abstract ideas to be communicated in a more engaging and imaginative way.

Keep reading and discover examples of metaphors and analogies in both academic and creative writing. While you are at it, our expert writers are ready to provide custom essays and papers which incorporate these literary devices in a seamless and effective way.

Using Famous Analogies Can Raise Plagiarism Concerns!

To avoid the trouble, use our online plagiarism checker and be sure that your work is original before submitting it.

Analogies and Metaphors Examples

There were a few analogies and metaphors examples mentioned along the way, but let's explore a few more to truly understand their power. Below you will find the list of metaphors and analogies, and you will never mistake one for the other again.

- Love is like a rose, beautiful but with thorns.

- The human body is like a machine, with many intricate parts working together in harmony.

- The structure of an atom is similar to a miniature solar system, with electrons orbiting around the nucleus.

- A computer's motherboard is like a city's central system, coordinating and communicating all functions.

- The brain is like a muscle that needs constant exercise to function at its best.

- Studying for exams is like training for a marathon; it requires endurance and preparation.

- Explaining a complex scientific concept is like explaining a foreign language to someone who doesn't speak it.

- A successful team is like a well-oiled machine, with each member playing a crucial role.

- Learning a new skill is like planting a seed; it requires nurturing and patience to see growth.

- Navigating through life is like sailing a ship with unpredictable currents and changing winds.

- Life is a journey with many twists and turns along the way

- The world's a stage, and we are all mere players.

- Her eyes were pools of sorrow, reflecting the pain she felt.

- Time is a thief, stealing away moments we can never recapture.

- Love is a flame, burning brightly but at risk of being extinguished.

- His words were daggers piercing through my heart.

- She had a heart of stone, unable to feel empathy or compassion.

- The city was a jungle, teeming with life and activity.

- Hope is a beacon, guiding us through the darkest of times.

- His anger was a volcano, ready to erupt at any moment.

How to Use Metaphors and Analogies in Writing: Helpful Tips

If you want your readers to have a memorable and engaging experience, you should give them some level of autonomy within your own text. Metaphors and analogies are powerful tools to let your audience do their personal interpretation and logical conclusion while still guiding them in the right direction.

First, learn about your audience and their level of familiarity with the topic you're writing about. Incorporate metaphors and analogies with familiar references. Remember, literary devices should cleverly explain complex concepts. To achieve the goal, remain coherent with the theme of the paper. But be careful not to overuse metaphors or analogies, as too much of a good thing can make your writing feel overloaded.

Use figurative language to evoke visual imagery and breathe life into your paper. Multiple metaphors can turn your paper into a movie. Visualizing ideas will help readers better understand and retain the information.

In conclusion, anytime is a great time to extend your text's impact by adding a well-chosen metaphor or analogy. But perfection is on the border of good and bad, so keep in mind to remain coherent with the theme and not overuse any literary device.

Metaphors: Unveiling Their Cultural Significance

Metaphors are not limited to just academic writing but can also be found in various forms of culture, such as art, music, film, and television. Metaphors have been a popular element in creative expression for centuries and continue to play a significant role in modern-day culture. For instance, metaphors can help artists convey complex emotions through their music or paintings.

Metaphors are often like time capsules, reflecting the cultural and societal values of a particular era. They shelter the prevailing beliefs, ideals, and philosophies of their time - from the pharaohs of ancient Egypt to modern-day pop culture.

Metaphors often frame our perception of the world and can shape our understanding of our surroundings. Certain words can take on new meanings when used metaphorically in certain cultural contexts and can assimilate to the phenomenon it is often compared to.

Here you can find a list of literature and poems with metaphors:

- William Shakespeare loved using metaphors, and here's one from his infamous Macbeth: 'It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.'

- Victor Hugo offers a timeless metaphor in Les Misérables: 'She is a rose, delicate and beautiful, but with thorns to protect her.'

- Robert Frost reminds us of his genius in the poem The Road Not Traveled: 'The road less traveled.'

Movies also contain a wide range of English metaphors:

- A famous metaphor from Toy Story: 'There's a snake in my boot!'

- A metaphor from the famous movie Silver Lining Playbook: 'Life is a game, and true love is a trophy.'

- An all-encompassing and iconic metaphor from the movie Star Wars: 'Fear is the path to the dark side.'

Don't forget about famous songs with beautiful metaphors!

- Bob Dylan's Blowin' in the Wind uses a powerful metaphor when he asks: 'How many roads must a man walk down?'

- A metaphor from Johnny Cash's song Ring of Fire: 'Love is a burning thing, and it makes a fiery ring.'

- Bonnie Tyler's famous lyrics from Total Eclipse of the Heart make a great metaphor: 'Love is a mystery, everyone must stand alone.'

Keep reading the article to find out how to write an essay with the effective use of metaphors in academic writing.

Exploring Types of Metaphors

There is a wide variety of metaphors used in academic writing, literature, music, and film. Different types of metaphors can be used to convey different meanings and create a specific impact or evoke a vivid image.

Some common types of metaphors include similes / simple metaphors, implicit metaphors, explicit metaphors, extended metaphors, mixed metaphors, and dead metaphors. Let's take a closer look at some of these types.

Simple metaphors or similes highlight the similarity between two things using 'like' or 'as.' For example, 'Her eyes were as bright as the stars.'

Implicit metaphors do not make a direct comparison. Instead, they imply the similarity between the two concepts. An example of an implicit metaphor is 'Her words cut deep,' where the similarity between words and a knife is implied. Good metaphors are often implicit since they require the reader to use their own understanding and imagination to understand the comparison being made.

Explicit metaphors are straightforward, making a clear comparison between two things. For instance, 'He is a shining star.'

An extended metaphor, on the other hand, stretches the comparison throughout an entire literary work or section of a text. This type of metaphor allows the writer to create a more complex and elaborate comparison, enhancing the reader's understanding of the subject.

Mixed metaphors combine two or more unrelated metaphors, often leading to confusion and lack of clarity. If you are not an expert on the subject, try to avoid using confusing literary devices.

Dead metaphors are another danger. These are metaphors that have been overused to the extent that they have lost their original impact, becoming clichés and not being able to evoke original visual images.

In academic writing, metaphors create a powerful impact on the reader, adding color and depth to everyday language. However, they need to be well-placed and intentional. Using an inappropriate or irrelevant metaphor may confuse readers and distract them from the main message. If you want to avoid trouble, pay for essay writing service that can help you use metaphors effectively in your academic writing.

Exploring Types of Analogies

Like metaphors, analogies are divided into several categories. Some of the common types include literal analogies, figurative analogies, descriptive analogies, causal analogies, and false/dubious analogies. In academic writing, analogies are useful for explaining complex ideas or phenomena in a way that is easy to understand.

Literal analogies are direct comparisons of two things with similar characteristics or features. For instance, 'The brain is like a computer.'

Figurative analogies, on the other hand, compare two unrelated things to highlight a particular characteristic. For example, 'The mind is a garden that needs to be tended.'

Descriptive analogies focus on the detailed similarities between two things, even if they are not immediately apparent. For example, 'The relationship between a supervisor and an employee is like that of a coach and a player, where the coach guides the player to perform at their best.'

Causal analogies are used to explain the relationship between a cause and an effect. For instance, 'The increase in global temperatures is like a fever caused by environmental pollution.'

Finally, false/dubious analogies are comparisons that suggest a similarity between two things that actually have little in common. For example, 'Getting a college degree is like winning the lottery.'

If you are trying to explain a foreign concept to an audience that may not be familiar with it, analogies can help create a bridge and make the concept more relatable. However, coming up with a perfect analogy takes a lot of time. If you are looking for ways on how to write an essay fast , explore our blog and learn even more.

If you want your academic papers to stand out and be engaging for the reader, using metaphors and analogies can be a powerful tool. Now that you know the difference between analogy and metaphor, you can use them wisely to create a bridge between complex ideas and your audience.

Explore our blog for more information on different writing techniques, and check out our essay writing service for more help on crafting the perfect papers.

Need to Be on Top of Your Academic Game?

We'll elevate your academic writing to the next level with papers tailored to your specific requirements!

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

.webp)

The Value of Analogies in Writing and Speech

Chris Stein/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

An analogy is a type of composition (or, more commonly, a part of an essay or speech ) in which one idea, process, or thing is explained by comparing it to something else.

Extended analogies are commonly used to make a complex process or idea easier to understand. "One good analogy," said American attorney Dudley Field Malone, "is worth three hours' discussion."

"Analogies prove nothing, that is true," wrote Sigmund Freud, "but they can make one feel more at home." In this article, we examine the characteristics of effective analogies and consider the value of using analogies in our writing.

An analogy is "reasoning or explaining from parallel cases." Put another way, an analogy is a comparison between two different things in order to highlight some point of similarity. As Freud suggested, an analogy won't settle an argument , but a good one may help to clarify the issues.

In the following example of an effective analogy, science writer Claudia Kalb relies on the computer to explain how our brains process memories:

Some basic facts about memory are clear. Your short-term memory is like the RAM on a computer: it records the information in front of you right now. Some of what you experience seems to evaporate--like words that go missing when you turn off your computer without hitting SAVE. But other short-term memories go through a molecular process called consolidation: they're downloaded onto the hard drive. These long-term memories, filled with past loves and losses and fears, stay dormant until you call them up. ("To Pluck a Rooted Sorrow," Newsweek , April 27, 2009)

Does this mean that human memory functions exactly like a computer in all ways? Certainly not. By its nature, an analogy offers a simplified view of an idea or process—an illustration rather than a detailed examination.

Analogy and Metaphor

Despite certain similarities, an analogy is not the same as a metaphor . As Bradford Stull observes in The Elements of Figurative Language (Longman, 2002), the analogy "is a figure of language that expresses a set of like relationships among two sets of terms. In essence, the analogy does not claim total identification, which is the property of the metaphor. It claims a similarity of relationships."

Comparison & Contrast

An analogy is not quite the same as comparison and contrast either, although both are methods of explanation that set things side by side. Writing in The Bedford Reader (Bedford/St. Martin's, 2008), X.J. and Dorothy Kennedy explain the difference:

You might show, in writing a comparison and contrast, how San Francisco is quite unlike Boston in history, climate, and predominant lifestyles, but like it in being a seaport and a city proud of its own (and neighboring) colleges. That isn't the way an analogy works. In an analogy, you yoke together two unlike things (eye and camera, the task of navigating a spacecraft and the task of sinking a putt), and all you care about is their major similarities.

The most effective analogies are usually brief and to the point—developed in just a few sentences. That said, in the hands of a talented writer, an extended analogy can be illuminating. See, for example, Robert Benchley's comic analogy involving writing and ice skating in "Advice to Writers."

Argument From Analogy

Whether it takes a few sentences or an entire essay to develop an analogy, we should be careful not to push it too far. As we've seen, just because two subjects have one or two points in common doesn't mean that they are the same in other respects as well. When Homer Simpson says to Bart, "Son, a woman is a lot like a refrigerator," we can be fairly certain that a breakdown in logic will follow. And sure enough: "They're about six feet tall, 300 pounds. They make ice, and . . . um . . . Oh, wait a minute. Actually, a woman is more like a beer." This sort of logical fallacy is called the argument from analogy or false analogy .

Examples of Analogies

Judge for yourself the effectiveness of each of these three analogies.

Pupils are more like oysters than sausages. The job of teaching is not to stuff them and then seal them up, but to help them open and reveal the riches within. There are pearls in each of us, if only we knew how to cultivate them with ardor and persistence. ( Sydney J. Harris, "What True Education Should Do," 1964)

Think of Wikipedia's community of volunteer editors as a family of bunnies left to roam freely over an abundant green prairie. In early, fat times, their numbers grow geometrically. More bunnies consume more resources, though, and at some point, the prairie becomes depleted, and the population crashes. Instead of prairie grasses, Wikipedia's natural resource is an emotion. "There's the rush of joy that you get the first time you make an edit to Wikipedia, and you realize that 330 million people are seeing it live," says Sue Gardner, Wikimedia Foundation's executive director. In Wikipedia's early days, every new addition to the site had a roughly equal chance of surviving editors' scrutiny. Over time, though, a class system emerged; now revisions made by infrequent contributors are much likelier to be undone by élite Wikipedians. Chi also notes the rise of wiki-lawyering: for your edits to stick, you've got to learn to cite the complex laws of Wikipedia in arguments with other editors. Together, these changes have created a community not very hospitable to newcomers. Chi says, "People begin to wonder, 'Why should I contribute anymore?'"--and suddenly, like rabbits out of food, Wikipedia's population stops growing. (Farhad Manjoo, "Where Wikipedia Ends." Time , Sep. 28, 2009)

The "great Argentine footballer, Diego Maradona, is not usually associated with the theory of monetary policy," Mervyn King explained to an audience in the City of London two years ago. But the player's performance for Argentina against England in the 1986 World Cup perfectly summarized modern central banking, the Bank of England's sport-loving governor added.

Maradona's infamous "hand of God" goal, which should have been disallowed, reflected old-fashioned central banking, Mr. King said. It was full of mystique and "he was lucky to get away with it." But the second goal, where Maradona beat five players before scoring, even though he ran in a straight line, was an example of the modern practice. "How can you beat five players by running in a straight line? The answer is that the English defenders reacted to what they expected Maradona to do. . . . Monetary policy works in a similar way. Market interest rates react to what the central bank is expected to do." (Chris Giles, "Alone Among Governors." Financial Times . Sep. 8-9, 2007)

Finally, keep in mind Mark Nichter's analogical observation: "A good analogy is like a plow which can prepare a population's field of associations for the planting of a new idea" ( Anthropology and International Health , 1989).

- Understanding Analogy

- What Is Clarity in Composition?

- False Analogy (Fallacy)

- Definition and Examples of Parody in English

- 30 Writing Topics: Analogy

- Heuristics in Rhetoric and Composition

- What Is Colloquial Style or Language?

- Hypercorrection in Grammar and Pronunciation

- Logos (Rhetoric)

- Using the Simple Sentence in Writing

- The Basic Characteristics of Effective Writing

- Learn About Précis Through Definition and Examples

- Euphuism (Prose Style)

- Definition and Examples of an Ad Hominem Fallacy

- Graphics in Business Writing, Technical Communication

- Definition and Examples of Bilingualism

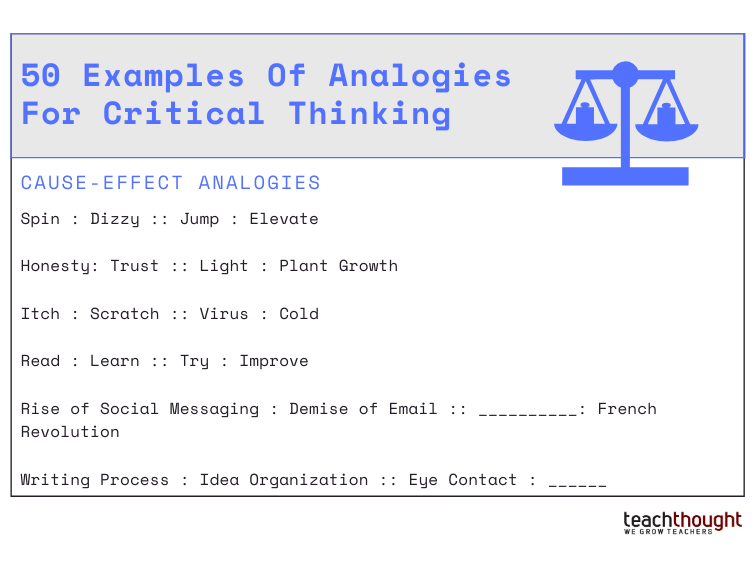

50 Examples Of Analogies For Critical Thinking

By forcing students to distill one relationship in order to understand another, it’s almost impossible to solve analogies without understanding.

What Are The Best Examples Of Analogies For Critical Thinking?

by Terry Heick

In our guide to teaching with analogies , we offered ideas, definitions, categories, and examples of analogies.

This post is a more specific version of that article where we focus specifically on types and examples of analogies rather than looking at teaching with analogies more broadly. Below, we offer more than 20 different types of analogies and examples of type of analogy as well–which results in nearly 100 examples of analogies overall.

Note that because an analogy is simply a pattern established by the nature of a relationship between two ‘things,’ there are an infinite number of kinds of analogies. You could, for example, set up an analogy by pairing two objects only loosely connected–brick and road, for example: a brick is to a road as…

Of course, analogies are best solved by creating a sentence that accurately captures the ‘truest and best’ essence of the relationship of the first two items in the analogy. So in the above brick/road example, you might say that ‘bricks used to be used to create roads,’ at which point all kinds of possibilities emerge: Bricks used to be used to create roads as glass used to be used to create bottles, yielding the analogy:

Bricks : Road :: Glass : Bottle

You could also use this in a specific content area–Social Studies, for example:

Bricks : Road :: Pamphlets : Propaganda

Language Arts?

Bricks : Roads :: Couplets : Sonnets? Maybe, but this leaves out the critical ‘used to be…’ bit.

You get the idea. By forcing students to distill one relationship in order to understand another, it’s almost impossible to accurately solve analogies without at least some kind of understanding–unless you use multiple-choice, in which case a lucky guess could do the trick.

Now, that’s a purposely far-fetched example. In most teaching and learning circumstances like courses and classrooms, analogies are used in common forms that are more or less obvious: part to whole, cause and effect, synonym and antonym, etc. This makes them less subjective and creative and easier to score on a multiple-choice question and can reduce the subjectivity of actually nailing down the uncertain relationship between ‘bricks’ and ‘roads.’ It becomes much easier when you use something with a more clear relationship, like ‘sapling is to tree as zygote is to…’