- Correspondence

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2011

How to do a grounded theory study: a worked example of a study of dental practices

- Alexandra Sbaraini 1 , 2 ,

- Stacy M Carter 1 ,

- R Wendell Evans 2 &

- Anthony Blinkhorn 1 , 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 11 , Article number: 128 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

387k Accesses

207 Citations

44 Altmetric

Metrics details

Qualitative methodologies are increasingly popular in medical research. Grounded theory is the methodology most-often cited by authors of qualitative studies in medicine, but it has been suggested that many 'grounded theory' studies are not concordant with the methodology. In this paper we provide a worked example of a grounded theory project. Our aim is to provide a model for practice, to connect medical researchers with a useful methodology, and to increase the quality of 'grounded theory' research published in the medical literature.

We documented a worked example of using grounded theory methodology in practice.

We describe our sampling, data collection, data analysis and interpretation. We explain how these steps were consistent with grounded theory methodology, and show how they related to one another. Grounded theory methodology assisted us to develop a detailed model of the process of adapting preventive protocols into dental practice, and to analyse variation in this process in different dental practices.

Conclusions

By employing grounded theory methodology rigorously, medical researchers can better design and justify their methods, and produce high-quality findings that will be more useful to patients, professionals and the research community.

Peer Review reports

Qualitative research is increasingly popular in health and medicine. In recent decades, qualitative researchers in health and medicine have founded specialist journals, such as Qualitative Health Research , established 1991, and specialist conferences such as the Qualitative Health Research conference of the International Institute for Qualitative Methodology, established 1994, and the Global Congress for Qualitative Health Research, established 2011 [ 1 – 3 ]. Journals such as the British Medical Journal have published series about qualitative methodology (1995 and 2008) [ 4 , 5 ]. Bodies overseeing human research ethics, such as the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, and the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research [ 6 , 7 ], have included chapters or sections on the ethics of qualitative research. The increasing popularity of qualitative methodologies for medical research has led to an increasing awareness of formal qualitative methodologies. This is particularly so for grounded theory, one of the most-cited qualitative methodologies in medical research [[ 8 ], p47].

Grounded theory has a chequered history [ 9 ]. Many authors label their work 'grounded theory' but do not follow the basics of the methodology [ 10 , 11 ]. This may be in part because there are few practical examples of grounded theory in use in the literature. To address this problem, we will provide a brief outline of the history and diversity of grounded theory methodology, and a worked example of the methodology in practice. Our aim is to provide a model for practice, to connect medical researchers with a useful methodology, and to increase the quality of 'grounded theory' research published in the medical literature.

The history, diversity and basic components of 'grounded theory' methodology and method

Founded on the seminal 1967 book 'The Discovery of Grounded Theory' [ 12 ], the grounded theory tradition is now diverse and somewhat fractured, existing in four main types, with a fifth emerging. Types one and two are the work of the original authors: Barney Glaser's 'Classic Grounded Theory' [ 13 ] and Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin's 'Basics of Qualitative Research' [ 14 ]. Types three and four are Kathy Charmaz's 'Constructivist Grounded Theory' [ 15 ] and Adele Clarke's postmodern Situational Analysis [ 16 ]: Charmaz and Clarke were both students of Anselm Strauss. The fifth, emerging variant is 'Dimensional Analysis' [ 17 ] which is being developed from the work of Leonard Schaztman, who was a colleague of Strauss and Glaser in the 1960s and 1970s.

There has been some discussion in the literature about what characteristics a grounded theory study must have to be legitimately referred to as 'grounded theory' [ 18 ]. The fundamental components of a grounded theory study are set out in Table 1 . These components may appear in different combinations in other qualitative studies; a grounded theory study should have all of these. As noted, there are few examples of 'how to do' grounded theory in the literature [ 18 , 19 ]. Those that do exist have focused on Strauss and Corbin's methods [ 20 – 25 ]. An exception is Charmaz's own description of her study of chronic illness [ 26 ]; we applied this same variant in our study. In the remainder of this paper, we will show how each of the characteristics of grounded theory methodology worked in our study of dental practices.

Study background

We used grounded theory methodology to investigate social processes in private dental practices in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. This grounded theory study builds on a previous Australian Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) called the Monitor Dental Practice Program (MPP) [ 27 ]. We know that preventive techniques can arrest early tooth decay and thus reduce the need for fillings [ 28 – 32 ]. Unfortunately, most dentists worldwide who encounter early tooth decay continue to drill it out and fill the tooth [ 33 – 37 ]. The MPP tested whether dentists could increase their use of preventive techniques. In the intervention arm, dentists were provided with a set of evidence-based preventive protocols to apply [ 38 ]; control practices provided usual care. The MPP protocols used in the RCT guided dentists to systematically apply preventive techniques to prevent new tooth decay and to arrest early stages of tooth decay in their patients, therefore reducing the need for drilling and filling. The protocols focused on (1) primary prevention of new tooth decay (tooth brushing with high concentration fluoride toothpaste and dietary advice) and (2) intensive secondary prevention through professional treatment to arrest tooth decay progress (application of fluoride varnish, supervised monitoring of dental plaque control and clinical outcomes)[ 38 ].

As the RCT unfolded, it was discovered that practices in the intervention arm were not implementing the preventive protocols uniformly. Why had the outcomes of these systematically implemented protocols been so different? This question was the starting point for our grounded theory study. We aimed to understand how the protocols had been implemented, including the conditions and consequences of variation in the process. We hoped that such understanding would help us to see how the norms of Australian private dental practice as regards to tooth decay could be moved away from drilling and filling and towards evidence-based preventive care.

Designing this grounded theory study

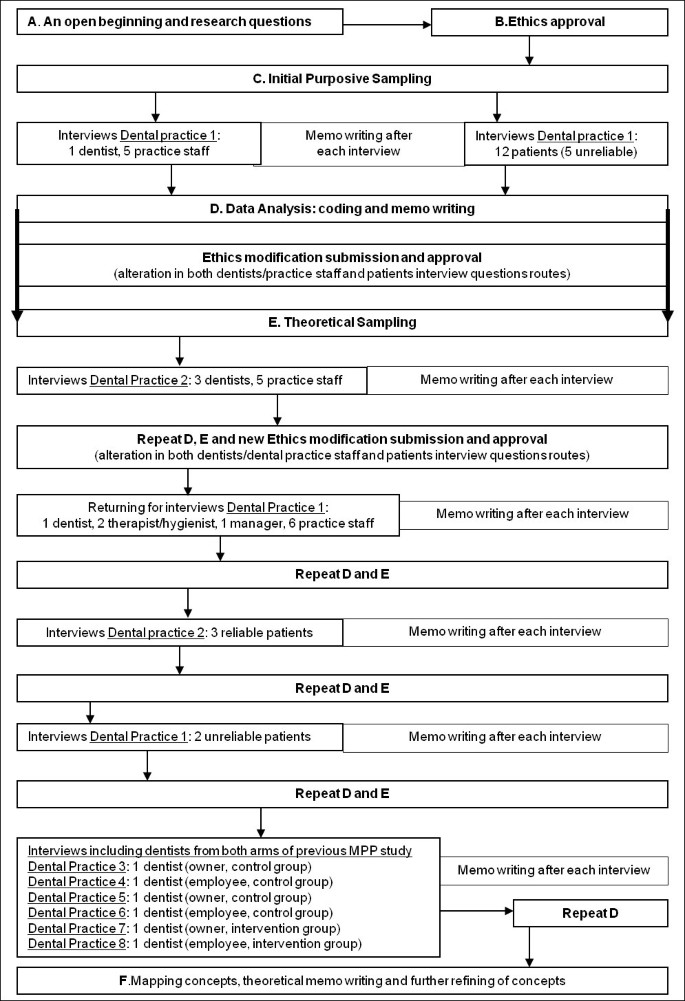

Figure 1 illustrates the steps taken during the project that will be described below from points A to F.

Study design . file containing a figure illustrating the study design.

A. An open beginning and research questions

Grounded theory studies are generally focused on social processes or actions: they ask about what happens and how people interact . This shows the influence of symbolic interactionism, a social psychological approach focused on the meaning of human actions [ 39 ]. Grounded theory studies begin with open questions, and researchers presume that they may know little about the meanings that drive the actions of their participants. Accordingly, we sought to learn from participants how the MPP process worked and how they made sense of it. We wanted to answer a practical social problem: how do dentists persist in drilling and filling early stages of tooth decay, when they could be applying preventive care?

We asked research questions that were open, and focused on social processes. Our initial research questions were:

What was the process of implementing (or not-implementing) the protocols (from the perspective of dentists, practice staff, and patients)?

How did this process vary?

B. Ethics approval and ethical issues

In our experience, medical researchers are often concerned about the ethics oversight process for such a flexible, unpredictable study design. We managed this process as follows. Initial ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Sydney. In our application, we explained grounded theory procedures, in particular the fact that they evolve. In our initial application we provided a long list of possible recruitment strategies and interview questions, as suggested by Charmaz [ 15 ]. We indicated that we would make future applications to modify our protocols. We did this as the study progressed - detailed below. Each time we reminded the committee that our study design was intended to evolve with ongoing modifications. Each modification was approved without difficulty. As in any ethical study, we ensured that participation was voluntary, that participants could withdraw at any time, and that confidentiality was protected. All responses were anonymised before analysis, and we took particular care not to reveal potentially identifying details of places, practices or clinicians.

C. Initial, Purposive Sampling (before theoretical sampling was possible)

Grounded theory studies are characterised by theoretical sampling, but this requires some data to be collected and analysed. Sampling must thus begin purposively, as in any qualitative study. Participants in the previous MPP study provided our population [ 27 ]. The MPP included 22 private dental practices in NSW, randomly allocated to either the intervention or control group. With permission of the ethics committee; we sent letters to the participants in the MPP, inviting them to participate in a further qualitative study. From those who agreed, we used the quantitative data from the MPP to select an initial sample.

Then, we selected the practice in which the most dramatic results had been achieved in the MPP study (Dental Practice 1). This was a purposive sampling strategy, to give us the best possible access to the process of successfully implementing the protocols. We interviewed all consenting staff who had been involved in the MPP (one dentist, five dental assistants). We then recruited 12 patients who had been enrolled in the MPP, based on their clinically measured risk of developing tooth decay: we selected some patients whose risk status had gotten better, some whose risk had worsened and some whose risk had stayed the same. This purposive sample was designed to provide maximum variation in patients' adoption of preventive dental care.

Initial Interviews

One hour in-depth interviews were conducted. The researcher/interviewer (AS) travelled to a rural town in NSW where interviews took place. The initial 18 participants (one dentist, five dental assistants and 12 patients) from Dental Practice 1 were interviewed in places convenient to them such as the dental practice, community centres or the participant's home.

Two initial interview schedules were designed for each group of participants: 1) dentists and dental practice staff and 2) dental patients. Interviews were semi-structured and based loosely on the research questions. The initial questions for dentists and practice staff are in Additional file 1 . Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. The research location was remote from the researcher's office, thus data collection was divided into two episodes to allow for intermittent data analysis. Dentist and practice staff interviews were done in one week. The researcher wrote memos throughout this week. The researcher then took a month for data analysis in which coding and memo-writing occurred. Then during a return visit, patient interviews were completed, again with memo-writing during the data-collection period.

D. Data Analysis

Coding and the constant comparative method.

Coding is essential to the development of a grounded theory [ 15 ]. According to Charmaz [[ 15 ], p46], 'coding is the pivotal link between collecting data and developing an emergent theory to explain these data. Through coding, you define what is happening in the data and begin to grapple with what it means'. Coding occurs in stages. In initial coding, the researcher generates as many ideas as possible inductively from early data. In focused coding, the researcher pursues a selected set of central codes throughout the entire dataset and the study. This requires decisions about which initial codes are most prevalent or important, and which contribute most to the analysis. In theoretical coding, the researcher refines the final categories in their theory and relates them to one another. Charmaz's method, like Glaser's method [ 13 ], captures actions or processes by using gerunds as codes (verbs ending in 'ing'); Charmaz also emphasises coding quickly, and keeping the codes as similar to the data as possible.

We developed our coding systems individually and through team meetings and discussions.

We have provided a worked example of coding in Table 2 . Gerunds emphasise actions and processes. Initial coding identifies many different processes. After the first few interviews, we had a large amount of data and many initial codes. This included a group of codes that captured how dentists sought out evidence when they were exposed to a complex clinical case, a new product or technique. Because this process seemed central to their practice, and because it was talked about often, we decided that seeking out evidence should become a focused code. By comparing codes against codes and data against data, we distinguished the category of "seeking out evidence" from other focused codes, such as "gathering and comparing peers' evidence to reach a conclusion", and we understood the relationships between them. Using this constant comparative method (see Table 1 ), we produced a theoretical code: "making sense of evidence and constructing knowledge". This code captured the social process that dentists went through when faced with new information or a practice challenge. This theoretical code will be the focus of a future paper.

Memo-writing

Throughout the study, we wrote extensive case-based memos and conceptual memos. After each interview, the interviewer/researcher (AS) wrote a case-based memo reflecting on what she learned from that interview. They contained the interviewer's impressions about the participants' experiences, and the interviewer's reactions; they were also used to systematically question some of our pre-existing ideas in relation to what had been said in the interview. Table 3 illustrates one of those memos. After a few interviews, the interviewer/researcher also began making and recording comparisons among these memos.

We also wrote conceptual memos about the initial codes and focused codes being developed, as described by Charmaz [ 15 ]. We used these memos to record our thinking about the meaning of codes and to record our thinking about how and when processes occurred, how they changed, and what their consequences were. In these memos, we made comparisons between data, cases and codes in order to find similarities and differences, and raised questions to be answered in continuing interviews. Table 4 illustrates a conceptual memo.

At the end of our data collection and analysis from Dental Practice 1, we had developed a tentative model of the process of implementing the protocols, from the perspective of dentists, dental practice staff and patients. This was expressed in both diagrams and memos, was built around a core set of focused codes, and illustrated relationships between them.

E. Theoretical sampling, ongoing data analysis and alteration of interview route

We have already described our initial purposive sampling. After our initial data collection and analysis, we used theoretical sampling (see Table 1 ) to determine who to sample next and what questions to ask during interviews. We submitted Ethics Modification applications for changes in our question routes, and had no difficulty with approval. We will describe how the interview questions for dentists and dental practice staff evolved, and how we selected new participants to allow development of our substantive theory. The patients' interview schedule and theoretical sampling followed similar procedures.

Evolution of theoretical sampling and interview questions

We now had a detailed provisional model of the successful process implemented in Dental Practice 1. Important core focused codes were identified, including practical/financial, historical and philosophical dimensions of the process. However, we did not yet understand how the process might vary or go wrong, as implementation in the first practice we studied had been described as seamless and beneficial for everyone. Because our aim was to understand the process of implementing the protocols, including the conditions and consequences of variation in the process, we needed to understand how implementation might fail. For this reason, we theoretically sampled participants from Dental Practice 2, where uptake of the MPP protocols had been very limited according to data from the RCT trial.

We also changed our interview questions based on the analysis we had already done (see Additional file 2 ). In our analysis of data from Dental Practice 1, we had learned that "effectiveness" of treatments and "evidence" both had a range of meanings. We also learned that new technologies - in particular digital x-rays and intra-oral cameras - had been unexpectedly important to the process of implementing the protocols. For this reason, we added new questions for the interviews in Dental Practice 2 to directly investigate "effectiveness", "evidence" and how dentists took up new technologies in their practice.

Then, in Dental Practice 2 we learned more about the barriers dentists and practice staff encountered during the process of implementing the MPP protocols. We confirmed and enriched our understanding of dentists' processes for adopting technology and producing knowledge, dealing with complex cases and we further clarified the concept of evidence. However there was a new, important, unexpected finding in Dental Practice 2. Dentists talked about "unreliable" patients - that is, patients who were too unreliable to have preventive dental care offered to them. This seemed to be a potentially important explanation for non-implementation of the protocols. We modified our interview schedule again to include questions about this concept (see Additional file 3 ) leading to another round of ethics approvals. We also returned to Practice 1 to ask participants about the idea of an "unreliable" patient.

Dentists' construction of the "unreliable" patient during interviews also prompted us to theoretically sample for "unreliable" and "reliable" patients in the following round of patients' interviews. The patient question route was also modified by the analysis of the dentists' and practice staff data. We wanted to compare dentists' perspectives with the perspectives of the patients themselves. Dentists were asked to select "reliable" and "unreliable" patients to be interviewed. Patients were asked questions about what kind of services dentists should provide and what patients valued when coming to the dentist. We found that these patients (10 reliable and 7 unreliable) talked in very similar ways about dental care. This finding suggested to us that some deeply-held assumptions within the dental profession may not be shared by dental patients.

At this point, we decided to theoretically sample dental practices from the non-intervention arm of the MPP study. This is an example of the 'openness' of a grounded theory study potentially subtly shifting the focus of the study. Our analysis had shifted our focus: rather than simply studying the process of implementing the evidence-based preventive protocols, we were studying the process of doing prevention in private dental practice. All participants seemed to be revealing deeply held perspectives shared in the dental profession, whether or not they were providing dental care as outlined in the MPP protocols. So, by sampling dentists from both intervention and control group from the previous MPP study, we aimed to confirm or disconfirm the broader reach of our emerging theory and to complete inductive development of key concepts. Theoretical sampling added 12 face to face interviews and 10 telephone interviews to the data. A total of 40 participants between the ages of 18 and 65 were recruited. Telephone interviews were of comparable length, content and quality to face to face interviews, as reported elsewhere in the literature [ 40 ].

F. Mapping concepts, theoretical memo writing and further refining of concepts

After theoretical sampling, we could begin coding theoretically. We fleshed out each major focused code, examining the situations in which they appeared, when they changed and the relationship among them. At time of writing, we have reached theoretical saturation (see Table 1 ). We have been able to determine this in several ways. As we have become increasingly certain about our central focused codes, we have re-examined the data to find all available insights regarding those codes. We have drawn diagrams and written memos. We have looked rigorously for events or accounts not explained by the emerging theory so as to develop it further to explain all of the data. Our theory, which is expressed as a set of concepts that are related to one another in a cohesive way, now accounts adequately for all the data we have collected. We have presented the developing theory to specialist dental audiences and to the participants, and have found that it was accepted by and resonated with these audiences.

We have used these procedures to construct a detailed, multi-faceted model of the process of incorporating prevention into private general dental practice. This model includes relationships among concepts, consequences of the process, and variations in the process. A concrete example of one of our final key concepts is the process of "adapting to" prevention. More commonly in the literature writers speak of adopting, implementing or translating evidence-based preventive protocols into practice. Through our analysis, we concluded that what was required was 'adapting to' those protocols in practice. Some dental practices underwent a slow process of adapting evidence-based guidance to their existing practice logistics. Successful adaptation was contingent upon whether (1) the dentist-in-charge brought the whole dental team together - including other dentists - and got everyone interested and actively participating during preventive activities; (2) whether the physical environment of the practice was re-organised around preventive activities, (3) whether the dental team was able to devise new and efficient routines to accommodate preventive activities, and (4) whether the fee schedule was amended to cover the delivery of preventive services, which hitherto was considered as "unproductive time".

Adaptation occurred over time and involved practical, historical and philosophical aspects of dental care. Participants transitioned from their initial state - selling restorative care - through an intermediary stage - learning by doing and educating patients about the importance of preventive care - and finally to a stage where they were offering patients more than just restorative care. These are examples of ways in which participants did not simply adopt protocols in a simple way, but needed to adapt the protocols and their own routines as they moved toward more preventive practice.

The quality of this grounded theory study

There are a number of important assurances of quality in keeping with grounded theory procedures and general principles of qualitative research. The following points describe what was crucial for this study to achieve quality.

During data collection

1. All interviews were digitally recorded, professionally transcribed in detail and the transcripts checked against the recordings.

2. We analysed the interview transcripts as soon as possible after each round of interviews in each dental practice sampled as shown on Figure 1 . This allowed the process of theoretical sampling to occur.

3. Writing case-based memos right after each interview while being in the field allowed the researcher/interviewer to capture initial ideas and make comparisons between participants' accounts. These memos assisted the researcher to make comparison among her reflections, which enriched data analysis and guided further data collection.

4. Having the opportunity to contact participants after interviews to clarify concepts and to interview some participants more than once contributed to the refinement of theoretical concepts, thus forming part of theoretical sampling.

5. The decision to include phone interviews due to participants' preference worked very well in this study. Phone interviews had similar length and depth compared to the face to face interviews, but allowed for a greater range of participation.

During data analysis

1. Detailed analysis records were kept; which made it possible to write this explanatory paper.

2. The use of the constant comparative method enabled the analysis to produce not just a description but a model, in which more abstract concepts were related and a social process was explained.

3. All researchers supported analysis activities; a regular meeting of the research team was convened to discuss and contextualize emerging interpretations, introducing a wide range of disciplinary perspectives.

Answering our research questions

We developed a detailed model of the process of adapting preventive protocols into dental practice, and analysed the variation in this process in different dental practices. Transferring evidence-based preventive protocols into these dental practices entailed a slow process of adapting the evidence to the existing practices logistics. Important practical, philosophical and historical elements as well as barriers and facilitators were present during a complex adaptation process. Time was needed to allow dentists and practice staff to go through this process of slowly adapting their practices to this new way of working. Patients also needed time to incorporate home care activities and more frequent visits to dentists into their daily routines. Despite being able to adapt or not, all dentists trusted the concrete clinical evidence that they have produced, that is, seeing results in their patients mouths made them believe in a specific treatment approach.

Concluding remarks

This paper provides a detailed explanation of how a study evolved using grounded theory methodology (GTM), one of the most commonly used methodologies in qualitative health and medical research [[ 8 ], p47]. In 2007, Bryant and Charmaz argued:

'Use of GTM, at least as much as any other research method, only develops with experience. Hence the failure of all those attempts to provide clear, mechanistic rules for GTM: there is no 'GTM for dummies'. GTM is based around heuristics and guidelines rather than rules and prescriptions. Moreover, researchers need to be familiar with GTM, in all its major forms, in order to be able to understand how they might adapt it in use or revise it into new forms and variations.' [[ 8 ], p17].

Our detailed explanation of our experience in this grounded theory study is intended to provide, vicariously, the kind of 'experience' that might help other qualitative researchers in medicine and health to apply and benefit from grounded theory methodology in their studies. We hope that our explanation will assist others to avoid using grounded theory as an 'approving bumper sticker' [ 10 ], and instead use it as a resource that can greatly improve the quality and outcome of a qualitative study.

Abbreviations

grounded theory methods

Monitor Dental Practice Program

New South Wales

Randomized Controlled Trial.

Qualitative Health Research Journal: website accessed on 10 June 2011, [ http://qhr.sagepub.com/ ]

Qualitative Health Research conference of The International Institute for Qualitative Methodology: website accessed on 10 June 2011, [ http://www.iiqm.ualberta.ca/en/Conferences/QualitativeHealthResearch.aspx ]

The Global Congress for Qualitative Health Research: website accessed on 10 June 2011, [ http://www.gcqhr.com/ ]

Mays N, Pope C: Qualitative research: observational methods in health care settings. BMJ. 1995, 311: 182-

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kuper A, Reeves S, Levinson W: Qualitative research: an introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008, 337: a288-10.1136/bmj.a288.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, Tri-Council Policy Statemen: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans . 1998, website accessed on 13 September 2011, [ http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/english/policystatement/introduction.cfm ]

Google Scholar

The Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research: website accessed on 10 June 2011, [ http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/e35syn.htm ]

Bryant A, Charmaz K, (eds.): Handbook of Grounded Theory. 2007, London: Sage

Walker D, Myrick F: Grounded theory: an exploration of process and procedure. Qual Health Res. 2006, 16: 547-559. 10.1177/1049732305285972.

Barbour R: Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog?. BMJ. 2001, 322: 1115-1117. 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115.

Dixon-Woods M, Booth A, Sutton AJ: Synthesizing qualitative research: a review of published reports. Qual Res. 2007, 7 (3): 375-422. 10.1177/1468794107078517.

Article Google Scholar

Glaser BG, Strauss AL: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. 1967, Chicago: Aldine

Glaser BG: Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Emergence vs Forcing. 1992, Mill Valley CA, USA: Sociology Press

Corbin J, Strauss AL: Basics of qualitative research. 2008, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 3

Charmaz K: Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. 2006, London: Sage

Clarke AE: Situational Analysis. Grounded Theory after the Postmodern Turn. 2005, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Bowers B, Schatzman L: Dimensional Analysis. Developing Grounded Theory: The Second Generation. Edited by: Morse JM, Stern PN, Corbin J, Bowers B, Charmaz K, Clarke AE. 2009, Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press, 86-125.

Morse JM, Stern PN, Corbin J, Bowers B, Charmaz K, Clarke AE, (eds.): Developing Grounded Theory: The Second Generation. 2009, Walnut Creek, CA, USA: Left Coast Press

Carter SM: Enacting Internal Coherence as a Path to Quality in Qualitative Inquiry. Researching Practice: A Discourse on Qualitative Methodologies. Edited by: Higgs J, Cherry N, Macklin R, Ajjawi R. 2010, Practice, Education, Work and Society Series. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2: 143-152.

Wasserman JA, Clair JM, Wilson KL: Problematics of grounded theory: innovations for developing an increasingly rigorous qualitative method. Qual Res. 2009, 9: 355-381. 10.1177/1468794109106605.

Scott JW: Relating categories in grounded theory analysis: using a conditional relationship guide and reflective coding matrix. The Qualitative Report. 2004, 9 (1): 113-126.

Sarker S, Lau F, Sahay S: Using an adapted grounded theory approach for inductive theory about virtual team development. Data Base Adv Inf Sy. 2001, 32 (1): 38-56.

LaRossa R: Grounded theory methods and qualitative family research. J Marriage Fam. 2005, 67 (4): 837-857. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00179.x.

Kendall J: Axial coding and the grounded theory controversy. WJNR. 1999, 21 (6): 743-757.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dickson-Swift V, James EL, Kippen S, Liamputtong P: Doing sensitive research: what challenges do qualitative researchers face?. Qual Res. 2007, 7 (3): 327-353. 10.1177/1468794107078515.

Charmaz K: Discovering chronic illness - using grounded theory. Soc Sci Med. 1990, 30,11: 1161-1172.

Curtis B, Evans RW, Sbaraini A, Schwarz E: The Monitor Practice Programme: is non-surgical management of tooth decay in private practice effective?. Aust Dent J. 2008, 53: 306-313. 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.00071.x.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Featherstone JDB: The caries balance: The basis for caries management by risk assessment. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004, 2 (S1): 259-264.

PubMed Google Scholar

Axelsson P, Nyström B, Lindhe J: The long-term effect of a plaque control program on tooth mortality, caries and periodontal disease in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2004, 31: 749-757. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00563.x.

Sbaraini A, Evans RW: Caries risk reduction in patients attending a caries management clinic. Aust Dent J. 2008, 53: 340-348. 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.00076.x.

Pitts NB: Monitoring of caries progression in permanent and primary posterior approximal enamel by bitewing radiography: A review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1983, 11: 228-235. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1983.tb01883.x.

Pitts NB: The use of bitewing radiographs in the management of dental caries: scientific and practical considerations. DentoMaxilloFac Rad. 1996, 25: 5-16.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Pitts NB: Are we ready to move from operative to non-operative/preventive treatment of dental caries in clinical practice?. Caries Res. 2004, 38: 294-304. 10.1159/000077769.

Tan PL, Evans RW, Morgan MV: Caries, bitewings, and treatment decisions. Aust Dent J. 2002, 47: 138-141. 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2002.tb00317.x.

Riordan P, Espelid I, Tveit A: Radiographic interpretation and treatment decisions among dental therapists and dentists in Western Australia. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991, 19: 268-271. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00165.x.

Espelid I, Tveit A, Haugejorden O, Riordan P: Variation in radiographic interpretation and restorative treatment decisions on approximal caries among dentists in Norway. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1985, 13: 26-29. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1985.tb00414.x.

Espelid I: Radiographic diagnoses and treatment decisions on approximal caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986, 14: 265-270. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1986.tb01069.x.

Evans RW, Pakdaman A, Dennison P, Howe E: The Caries Management System: an evidence-based preventive strategy for dental practitioners. Application for adults. Aust Dent J. 2008, 53: 83-92. 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.00004.x.

Blumer H: Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. 1969, Berkley: University of California Press

Sturges JE, Hanrahan KJ: Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: a research note. Qual Res. 2004, 4 (1): 107-18. 10.1177/1468794104041110.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/11/128/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank dentists, dental practice staff and patients for their invaluable contributions to the study. We thank Emeritus Professor Miles Little for his time and wise comments during the project.

The authors received financial support for the research from the following funding agencies: University of Sydney Postgraduate Award 2009; The Oral Health Foundation, University of Sydney; Dental Board New South Wales; Australian Dental Research Foundation; National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grant 632715.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Values, Ethics and the Law in Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Alexandra Sbaraini, Stacy M Carter & Anthony Blinkhorn

Population Oral Health, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Alexandra Sbaraini, R Wendell Evans & Anthony Blinkhorn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alexandra Sbaraini .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to conception and design of this study. AS carried out data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. SMC made substantial contribution during data collection, analysis and data interpretation. AS, SMC, RWE, and AB have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12874_2011_640_moesm1_esm.doc.

Additional file 1: Initial interview schedule for dentists and dental practice staff. file containing initial interview schedule for dentists and dental practice staff. (DOC 30 KB)

12874_2011_640_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional file 2: Questions added to the initial interview schedule for dentists and dental practice staff. file containing questions added to the initial interview schedule (DOC 26 KB)

12874_2011_640_MOESM3_ESM.DOC

Additional file 3: Questions added to the modified interview schedule for dentists and dental practice staff. file containing questions added to the modified interview schedule (DOC 26 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sbaraini, A., Carter, S.M., Evans, R.W. et al. How to do a grounded theory study: a worked example of a study of dental practices. BMC Med Res Methodol 11 , 128 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-128

Download citation

Received : 17 June 2011

Accepted : 09 September 2011

Published : 09 September 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-128

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- qualitative research

- grounded theory

- methodology

- dental care

BMC Medical Research Methodology

ISSN: 1471-2288

- General enquiries: [email protected]

10 Grounded Theory Examples (Qualitative Research Method)

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Grounded theory is a qualitative research method that involves the construction of theory from data rather than testing theories through data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In other words, a grounded theory analysis doesn’t start with a hypothesis or theoretical framework, but instead generates a theory during the data analysis process .

This method has garnered a notable amount of attention since its inception in the 1960s by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

Grounded Theory Definition and Overview

A central feature of grounded theory is the continuous interplay between data collection and analysis (Bringer, Johnston, & Brackenridge, 2016).

Grounded theorists start with the data, coding and considering each piece of collected information (for instance, behaviors collected during a psychological study).

As more information is collected, the researcher can reflect upon the data in an ongoing cycle where data informs an ever-growing and evolving theory (Mills, Bonner & Francis, 2017).

As such, the researcher isn’t tied to testing a hypothesis, but instead, can allow surprising and intriguing insights to emerge from the data itself.

Applications of grounded theory are widespread within the field of social sciences . The method has been utilized to provide insight into complex social phenomena such as nursing, education, and business management (Atkinson, 2015).

Grounded theory offers a sound methodology to unearth the complexities of social phenomena that aren’t well-understood in existing theories (McGhee, Marland & Atkinson, 2017).

While the methods of grounded theory can be labor-intensive and time-consuming, the rich, robust theories this approach produces make it a valuable tool in many researchers’ repertoires.

Real-Life Grounded Theory Examples

Title: A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology

Citation: Weatherall, J. W. A. (2000). A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology. Educational Gerontology , 26 (4), 371-386.

Description: This study employed a grounded theory approach to investigate older adults’ use of information technology (IT). Six participants from a senior senior were interviewed about their experiences and opinions regarding computer technology. Consistent with a grounded theory angle, there was no hypothesis to be tested. Rather, themes emerged out of the analysis process. From this, the findings revealed that the participants recognized the importance of IT in modern life, which motivated them to explore its potential. Positive attitudes towards IT were developed and reinforced through direct experience and personal ownership of technology.

Title: A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study

Citation: Jacobson, N. (2009). A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study. BMC International health and human rights , 9 (1), 1-9.

Description: This study aims to develop a taxonomy of dignity by letting the data create the taxonomic categories, rather than imposing the categories upon the analysis. The theory emerged from the textual and thematic analysis of 64 interviews conducted with individuals marginalized by health or social status , as well as those providing services to such populations and professionals working in health and human rights. This approach identified two main forms of dignity that emerged out of the data: “ human dignity ” and “social dignity”.

Title: A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose

Citation: Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research , 27 (1), 78-109.

Description: This study explores the development of noble youth purpose over time using a grounded theory approach. Something notable about this study was that it returned to collect additional data two additional times, demonstrating how grounded theory can be an interactive process. The researchers conducted three waves of interviews with nine adolescents who demonstrated strong commitments to various noble purposes. The findings revealed that commitments grew slowly but steadily in response to positive feedback, with mentors and like-minded peers playing a crucial role in supporting noble purposes.

Title: A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users

Citation: Pace, S. (2004). A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users. International journal of human-computer studies , 60 (3), 327-363.

Description: This study attempted to understand the flow experiences of web users engaged in information-seeking activities, systematically gathering and analyzing data from semi-structured in-depth interviews with web users. By avoiding preconceptions and reviewing the literature only after the theory had emerged, the study aimed to develop a theory based on the data rather than testing preconceived ideas. The study identified key elements of flow experiences, such as the balance between challenges and skills, clear goals and feedback, concentration, a sense of control, a distorted sense of time, and the autotelic experience.

Title: Victimising of school bullying: a grounded theory

Citation: Thornberg, R., Halldin, K., Bolmsjö, N., & Petersson, A. (2013). Victimising of school bullying: A grounded theory. Research Papers in Education , 28 (3), 309-329.

Description: This study aimed to investigate the experiences of individuals who had been victims of school bullying and understand the effects of these experiences, using a grounded theory approach. Through iterative coding of interviews, the researchers identify themes from the data without a pre-conceived idea or hypothesis that they aim to test. The open-minded coding of the data led to the identification of a four-phase process in victimizing: initial attacks, double victimizing, bullying exit, and after-effects of bullying. The study highlighted the social processes involved in victimizing, including external victimizing through stigmatization and social exclusion, as well as internal victimizing through self-isolation, self-doubt, and lingering psychosocial issues.

Hypothetical Grounded Theory Examples

Suggested Title: “Understanding Interprofessional Collaboration in Emergency Medical Services”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Coding and constant comparative analysis

How to Do It: This hypothetical study might begin with conducting in-depth interviews and field observations within several emergency medical teams to collect detailed narratives and behaviors. Multiple rounds of coding and categorizing would be carried out on this raw data, consistently comparing new information with existing categories. As the categories saturate, relationships among them would be identified, with these relationships forming the basis of a new theory bettering our understanding of collaboration in emergency settings. This iterative process of data collection, analysis, and theory development, continually refined based on fresh insights, upholds the essence of a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “The Role of Social Media in Political Engagement Among Young Adults”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Open, axial, and selective coding

Explanation: The study would start by collecting interaction data on various social media platforms, focusing on political discussions engaged in by young adults. Through open, axial, and selective coding, the data would be broken down, compared, and conceptualized. New insights and patterns would gradually form the basis of a theory explaining the role of social media in shaping political engagement, with continuous refinement informed by the gathered data. This process embodies the recursive essence of the grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Transforming Workplace Cultures: An Exploration of Remote Work Trends”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Constant comparative analysis

Explanation: The theoretical study could leverage survey data and in-depth interviews of employees and bosses engaging in remote work to understand the shifts in workplace culture. Coding and constant comparative analysis would enable the identification of core categories and relationships among them. Sustainability and resilience through remote ways of working would be emergent themes. This constant back-and-forth interplay between data collection, analysis, and theory formation aligns strongly with a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Persistence Amidst Challenges: A Grounded Theory Approach to Understanding Resilience in Urban Educators”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Iterative Coding

How to Do It: This study would involve collecting data via interviews from educators in urban school systems. Through iterative coding, data would be constantly analyzed, compared, and categorized to derive meaningful theories about resilience. The researcher would constantly return to the data, refining the developing theory with every successive interaction. This procedure organically incorporates the grounded theory approach’s characteristic iterative nature.

Suggested Title: “Coping Strategies of Patients with Chronic Pain: A Grounded Theory Study”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Line-by-line inductive coding

How to Do It: The study might initiate with in-depth interviews of patients who’ve experienced chronic pain. Line-by-line coding, followed by memoing, helps to immerse oneself in the data, utilizing a grounded theory approach to map out the relationships between categories and their properties. New rounds of interviews would supplement and refine the emergent theory further. The subsequent theory would then be a detailed, data-grounded exploration of how patients cope with chronic pain.

Grounded theory is an innovative way to gather qualitative data that can help introduce new thoughts, theories, and ideas into academic literature. While it has its strength in allowing the “data to do the talking”, it also has some key limitations – namely, often, it leads to results that have already been found in the academic literature. Studies that try to build upon current knowledge by testing new hypotheses are, in general, more laser-focused on ensuring we push current knowledge forward. Nevertheless, a grounded theory approach is very useful in many circumstances, revealing important new information that may not be generated through other approaches. So, overall, this methodology has great value for qualitative researchers, and can be extremely useful, especially when exploring specific case study projects . I also find it to synthesize well with action research projects .

Atkinson, P. (2015). Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: Valid qualitative research strategies for educators. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 6 (1), 83-86.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . London: Sage.

Bringer, J. D., Johnston, L. H., & Brackenridge, C. H. (2016). Using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software to develop a grounded theory project. Field Methods, 18 (3), 245-266.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . Sage publications.

McGhee, G., Marland, G. R., & Atkinson, J. (2017). Grounded theory research: Literature reviewing and reflexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29 (3), 654-663.

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2017). Adopting a Constructivist Approach to Grounded Theory: Implications for Research Design. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 13 (2), 81-89.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Grounded Theory In Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Grounded theory is a useful approach when you want to develop a new theory based on real-world data Instead of starting with a pre-existing theory, grounded theory lets the data guide the development of your theory.

What Is Grounded Theory?

Grounded theory is a qualitative method specifically designed to inductively generate theory from data. It was developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967.

- Data shapes the theory: Instead of trying to prove an existing theory, you let the data guide your findings.

- No guessing games: You don’t start with assumptions or try to confirm your own biases.

- Data collection and analysis happen together: You analyze information as you gather it, which helps you decide what data to collect next.

It is important to note that grounded theory is an inductive approach where a theory is developed from collected real-world data rather than trying to prove or disprove a hypothesis like in a deductive scientific approach

You gather information, look for patterns, and use those patterns to develop an explanation.

It is a way to understand why people do things and how those actions create patterns. Imagine you’re trying to figure out why your friends love a certain video game.

Instead of asking an adult, you observe your friends while they’re playing, listen to them talk about it, and maybe even play a little yourself. By studying their actions and words, you’re using grounded theory to build an understanding of their behavior.

This qualitative method of research focuses on real-life experiences and observations, letting theories emerge naturally from the data collected, like piecing together a puzzle without knowing the final image.

When should you use grounded theory?

Grounded theory research is useful for beginning researchers, particularly graduate students, because it offers a clear and flexible framework for conducting a study on a new topic.

Grounded theory works best when existing theories are either insufficient or nonexistent for the topic at hand.

Since grounded theory is a continuously evolving process, researchers collect and analyze data until theoretical saturation is reached or no new insights can be gained.

What is the final product of a GT study?

The final product of a grounded theory (GT) study is an integrated and comprehensive grounded theory that explains a process or scheme associated with a phenomenon.

The quality of a GT study is judged on whether it produces this middle-range theory

Middle-range theories are sort of like explanations that focus on a specific part of society or a particular event. They don’t try to explain everything in the world. Instead, they zero in on things happening in certain groups, cultures, or situations.

Think of it like this: a grand theory is like trying to understand all of weather at once, but a middle-range theory is like focusing on how hurricanes form.

Here are a few examples of what middle-range theories might try to explain:

- How people deal with feeling anxious in social situations.

- How people act and interact at work.

- How teachers handle students who are misbehaving in class.

Core Components of Grounded Theory

This terminology reflects the iterative, inductive, and comparative nature of grounded theory, which distinguishes it from other research approaches.

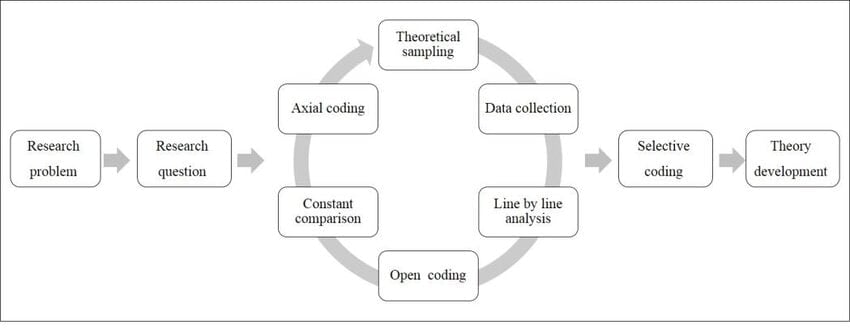

- Theoretical Sampling: The researcher uses theoretical sampling to choose new participants or data sources based on the emerging findings of their study. The goal is to gather data that will help to further develop and refine the emerging categories and theoretical concepts.

- Theoretical Sensitivity: Researchers need to be aware of their preconceptions going into a study and understand how those preconceptions could influence the research. However, it is not possible to completely separate a researcher’s history and experience from the construction of a theory.

- Coding: Coding is the process of analyzing qualitative data (usually text) by assigning labels (codes) to chunks of data that capture their essence or meaning. It allows you to condense, organize and interpret your data.

- Core Category: The core category encapsulates and explains the grounded theory as a whole. Researchers identify a core category to focus on during the later stages of their research.

- Memos: Researchers use memos to record their thoughts and ideas about the data, explore relationships between codes and categories, and document the development of the emerging grounded theory. Memos support the development of theory by tracking emerging themes and patterns.

- Theoretical Saturation: This term refers to the point in a grounded theory study when collecting additional data does not yield any new theoretical insights. The researcher continues the process of collecting and analyzing data until theoretical saturation is reached.

- Constant Comparative Analysis: This method involves the systematic comparison of data points, codes, and categories as they emerge from the research process. Researchers use constant comparison to identify patterns and connections in their data.

Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss first introduced grounded theory in 1967 in their book, The Discovery of Grounded Theory .

Their aim was to create a research method that prioritized real-world data to understand social behavior.

However, their approaches diverged over time, leading to two distinct versions: Glaserian and Straussian grounded theory.

The different versions of grounded theory diverge in their approaches to coding , theory construction, and the use of literature.

All versions of grounded theory share the goal of generating a middle-range theory that explains a social process or phenomenon.

They also emphasize the importance of theoretical sampling , constant comparative analysis , and theoretical saturation in developing a robust theory

Glaserian Grounded Theory

Glaserian grounded theory emphasizes the emergence of theory from data and discourages the use of pre-existing literature.

Glaser believed that adopting a specific philosophical or disciplinary perspective reduces the broader potential of grounded theory.

For Glaser, prior understandings should be based on the general problem area and reading very wide to alert or sensitize one to a wide range of possibilities.

It prioritizes parsimony , scope , and modifiability in the resulting theory

Straussian Grounded Theory

Strauss and Corbin (1990) focused on developing the analytic techniques and providing guidance to novice researchers.

Straussian grounded theory utilizes a more structured approach to coding and analysis and acknowledges the role of the literature in shaping research.

It acknowledges the role of deduction and validation in addition to induction.

Strauss and Corbin also emphasize the use of unstructured interview questions to encourage participants to speak freely

Critics of this approach believe it produced a rigidity never intended for grounded theory.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This version, primarily associated with Charmaz, recognizes that knowledge is situated, partial, provisional, and socially constructed. It emphasizes abstract and conceptual understandings rather than explanations.

Kathy Charmaz expanded on original versions of GT, emphasizing the researcher’s role in interpreting findings

Constructivist grounded theory acknowledges the researcher’s influence on the research process and the co-creation of knowledge with participants

Situational Analysis

Developed by Clarke, this version builds upon Straussian and Constructivist grounded theory and incorporates postmodern , poststructuralist , and posthumanist perspectives.

Situational analysis incorporates postmodern perspectives and considers the role of nonhuman actors

It introduces the method of mapping to analyze complex situations and emphasizes both human and nonhuman elements .

- Discover New Insights: Grounded theory lets you uncover new theories based on what your data reveals, not just on pre-existing ideas.

- Data-Driven Results: Your conclusions are firmly rooted in the data you’ve gathered, ensuring they reflect reality. This close relationship between data and findings is a key factor in establishing trustworthiness.

- Avoids Bias: Because gathering data and analyzing it are closely intertwined, researchers are truly observing what emerges from data, and are less likely to let their preconceptions color the findings.

- Streamlined data gathering and analysis: Analyzing and collecting data go hand in hand. Data is collected, analyzed, and as you gain insight from analysis, you continue gathering more data.

- Synthesize Findings : By applying grounded theory to a qualitative metasynthesis , researchers can move beyond a simple aggregation of findings and generate a higher-level understanding of the phenomena being studied.

Limitations

- Time-Consuming: Analyzing qualitative data can be like searching for a needle in a haystack; it requires careful examination and can be quite time-consuming, especially without software assistance6.

- Potential for Bias: Despite safeguards, researchers may unintentionally influence their analysis due to personal experiences.

- Data Quality: The success of grounded theory hinges on complete and accurate data; poor quality can lead to faulty conclusions.

Practical Steps

Grounded theory can be conducted by individual researchers or research teams. If working in a team, it’s important to communicate regularly and ensure everyone is using the same coding system.

Grounded theory research is typically an iterative process. This means that researchers may move back and forth between these steps as they collect and analyze data.

Instead of doing everything in order, you repeat the steps over and over.

This cycle keeps going, which is why grounded theory is called a circular process.

Continue to gather and analyze data until no new insights or properties related to your categories emerge. This saturation point signals that the theory is comprehensive and well-substantiated by the data.

Theoretical sampling, collecting sufficient and rich data, and theoretical saturation help the grounded theorist to avoid a lack of “groundedness,” incomplete findings, and “premature closure.

1. Planning and Philosophical Considerations

Begin by considering the phenomenon you want to study and assess the current knowledge surrounding it.

However, refrain from detailing the specific aspects you seek to uncover about the phenomenon to prevent pre-existing assumptions from skewing the research.

- Discern a personal philosophical position. Before beginning a research study, it is important to consider your philosophical stance and how you view the world, including the nature of reality and the relationship between the researcher and the participant. This will inform the methodological choices made throughout the study.

- Investigate methodological possibilities. Explore different research methods that align with both the philosophical stance and research goals of the study.

- Plan the study. Determine the research question, how to collect data, and from whom to collect data.

- Conduct a literature review. The literature review is an ongoing process throughout the study. It is important to avoid duplicating existing research and to consider previous studies, concepts, and interpretations that relate to the emerging codes and categories in the developing grounded theory.

2. Recruit participants using theoretical sampling

Initially, select participants who are readily available ( convenience sampling ) or those recommended by existing participants ( snowball sampling ).

As the analysis progresses, transition to theoretical sampling , involving the deliberate selection of participants and data sources to refine your emerging theory.

This method is used to refine and develop a grounded theory. The researcher uses theoretical sampling to choose new participants or data sources based on the emerging findings of their study.

This could mean recruiting participants who can shed light on gaps in your understanding uncovered during the initial data analysis.

Theoretical sampling guides further data collection by identifying participants or data sources that can provide insights into gaps in the emerging theory

The goal is to gather data that will help to further develop and refine the emerging categories and theoretical concepts.

Theoretical sampling starts early in a GT study and generally requires the researcher to make amendments to their ethics approvals to accommodate new participant groups.

3. Collect Data

The researcher might use interviews, focus groups, observations, or a combination of methods to collect qualitative data.

- Observations : Watching and recording phenomena as they occur. Can be participant (researcher actively involved) or non-participant (researcher tries not to influence behaviors), and covert (participants unaware) or overt (participants aware).

- Interviews : One-on-one conversations to understand participants’ experiences. Can be structured (predetermined questions), informal (casual conversations), or semi-structured (flexible structure to explore emerging issues).

- Focus groups : Dynamic discussions with 4-10 participants sharing characteristics, moderated by the researcher using a topic guide.

- Ethnography : Studying a group’s behaviors and social interactions in their environment through observations, field notes, and interviews. Researchers immerse themselves in the community or organization for an in-depth understanding.

4. Begin open coding as soon as data collection starts

Open coding is the first stage of coding in grounded theory, where you carefully examine and label segments of your data to identify initial concepts and ideas.

This process involves scrutinizing the data and creating codes grounded in the data itself.

The initial codes stay close to the data, aiming to capture and summarize critically and analytically what is happening in the data

To begin open coding, read through your data, such as interview transcripts, to gain a comprehensive understanding of what is being conveyed.

As you encounter segments of data that represent a distinct idea, concept, or action, you assign a code to that segment. These codes act as descriptive labels summarizing the meaning of the data segment.

For instance, if you were analyzing interview data about experiences with a new medication, a segment of data might describe a participant’s difficulty sleeping after taking the medication. This segment could be labeled with the code “trouble sleeping”

Open coding is a crucial step in grounded theory because it allows you to break down the data into manageable units and begin to see patterns and themes emerge.

As you continue coding, you constantly compare different segments of data to refine your understanding of existing codes and identify new ones.

For instance, excerpts describing difficulties with sleep might be grouped under the code “trouble sleeping”.

This iterative process of comparing data and refining codes helps ensure the codes accurately reflect the data.

Open coding is about staying close to the data, using in vivo terms or gerunds to maintain a sense of action and process

5. Reflect on thoughts and contradictions by writing grounded theory memos during analysis

During open coding, it’s crucial to engage in memo writing. Memos serve as your “notes to self”, allowing you to reflect on the coding process, note emerging patterns, and ask analytical questions about the data.

Document your thoughts, questions, and insights in memos throughout the research process.

These memos serve multiple purposes: tracing your thought process, promoting reflexivity (self-reflection), facilitating collaboration if working in a team, and supporting theory development.

Early memos tend to be shorter and less conceptual, often serving as “preparatory” notes. Later memos become more analytical and conceptual as the research progresses.

Memo Writing

- Reflexivity and Recognizing Assumptions: Researchers should acknowledge the influence of their own experiences and assumptions on the research process. Articulating these assumptions, perhaps through memos, can enhance the transparency and trustworthiness of the study.

- Write memos throughout the research process. Memo writing should occur throughout the entire research process, beginning with initial coding.67 Memos help make sense of the data and transition between coding phases.8

- Ask analytic questions in early memos. Memos should include questions, reflections, and notes to explore in subsequent data collection and analysis.8

- Refine memos throughout the process. Early memos will be shorter and less conceptual, but will become longer and more developed in later stages of the research process.7 Later memos should begin to develop provisional categories.

6. Group codes into categories using axial coding

Axial coding is the process of identifying connections between codes, grouping them together into categories to reveal relationships within the data.

Axial coding seeks to find the axes that connect various codes together.

For example, in research on school bullying, focused codes such as “Doubting oneself, getting low self-confidence, starting to agree with bullies” and “Getting lower self-confidence; blaming oneself” could be grouped together into a broader category representing the impact of bullying on self-perception.

Similarly, codes such as “Being left by friends” and “Avoiding school; feeling lonely and isolated” could be grouped into a category related to the social consequences of bullying.

These categories then become part of the emerging grounded theory, explaining the multifaceted aspects of the phenomenon.

Qualitative data analysis software often represents these categories as nested codes, visually demonstrating the hierarchy and interconnectedness of the concepts.

This hierarchical structure helps researchers organize their data, identify patterns, and develop a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between different aspects of the phenomenon being studied.

This process of axial coding is crucial for moving beyond descriptive accounts of the data towards a more theoretically rich and explanatory grounded theory.

7. Define the core category using selective coding

During selective coding , the final development stage of grounded theory analysis, a researcher focuses on developing a detailed and integrated theory by selecting a core category and connecting it to other categories developed during earlier coding stages.

The core category is the central concept that links together the various categories and subcategories identified in the data and forms the foundation of the emergent grounded theory.

This core category will encapsulate the main theme of your grounded theory, that encompasses and elucidates the overarching process or phenomenon under investigation.

This phase involves a concentrated effort to refine and integrate categories, ensuring they align with the core category and contribute to the overall explanatory power of the theory.

The theory should comprehensively describe the process or scheme related to the phenomenon being studied.

For example, in a study on school bullying, if the core category is “victimization journey,” the researcher would selectively code data related to different stages of this journey, the factors contributing to each stage, and the consequences of experiencing these stages.

This might involve analyzing how victims initially attribute blame, their coping mechanisms, and the long-term impact of bullying on their self-perception.

Continue collecting data and analyzing until you reach theoretical saturation

Selective coding focuses on developing and saturating this core category, leading to a cohesive and integrated theory.

Through selective coding, researchers aim to achieve theoretical saturation, meaning no new properties or insights emerge from further data analysis.

This signifies that the core category and its related categories are well-defined, and the connections between them are thoroughly explored.

This rigorous process strengthens the trustworthiness of the findings by ensuring the theory is comprehensive and grounded in a rich dataset.

It’s important to note that while a grounded theory seeks to provide a comprehensive explanation, it remains grounded in the data.

The theory’s scope is limited to the specific phenomenon and context studied, and the researcher acknowledges that new data or perspectives might lead to modifications or refinements of the theory

- Constant Comparative Analysis: This method involves the systematic comparison of data points, codes, and categories as they emerge from the research process. Researchers use constant comparison to identify patterns and connections in their data. There are different methods for comparing excerpts from interviews, for example, a researcher can compare excerpts from the same person, or excerpts from different people. This process is ongoing and iterative, and it continues until the researcher has developed a comprehensive and well-supported grounded theory.

- Continue until reaching theoretical saturation : Continue to gather and analyze data until no new insights or properties related to your categories. This saturation point signals that the theory is comprehensive and well-substantiated by the data.

8. Theoretical coding and model development

Theoretical coding is a process in grounded theory where researchers use advanced abstractions, often from existing theories, to explain the relationships found in their data.

Theoretical coding often occurs later in the research process and involves using existing theories to explain the connections between codes and categories.

This process helps to strengthen the explanatory power of the grounded theory. Theoretical coding should not be confused with simply describing the data; instead, it aims to explain the phenomenon being studied, distinguishing grounded theory from purely descriptive research.

Using the developed codes, categories, and core category, create a model illustrating the process or phenomenon.

Here is some advice for novice researchers on how to apply theoretical coding:

- Begin with data analysis: Don’t start with a pre-determined theory. Instead, allow the theory to emerge from your data through careful analysis and coding.

- Use existing theories as a guide: While the theory should primarily emerge from your data, you can use existing theories from any discipline to help explain the connections you are seeing between your categories. This demonstrates how your research builds on established knowledge.

- Use Glaser’s coding families: Consider applying Glaser’s (1978) coding families in the later stages of analysis as a simple way to begin theoretical coding. Remember that your analysis should guide which theoretical codes are most appropriate.

- Keep it simple: Theoretical coding doesn’t need to be overly complex. Focus on finding an existing theory that effectively explains the relationships you have identified in your data.

- Be transparent: Clearly articulate the existing theory you are using and how it explains the connections between your categories.

- Theoretical coding is an iterative process : Remain open to revising your chosen theoretical codes as your analysis deepens and your grounded theory evolves.

9. Write your grounded theory

Present your findings in a clear and accessible manner, ensuring the theory is rooted in the data and explains the relationships between the identified concepts and categories.

The end product of this process is a well-defined, integrated grounded theory that explains a process or scheme related to the phenomenon studied.

- Develop a dissemination plan : Determine how to share the research findings with others.

- Evaluate and implement : Reflect on the research process and quality of findings, then share findings with relevant audiences in service of making a difference in the world

Reading List

Grounded Theory Review : This is an international journal that publishes articles on grounded theory.

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13, 3-21.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Clarke, A. E. (2003). Situational analyses: Grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn . Symbolic interaction , 26 (4), 553-576.

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity . University of California.

- Glaser, B. G. (2005). The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding . Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Holton, J. (2004, May). Remodeling grounded theory. In Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: qualitative social research (Vol. 5, No. 2).

- Charmaz, K. (2012). The power and potential of grounded theory. Medical sociology online , 6 (3), 2-15.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1965). Awareness of dying. New Brunswick. NJ: Aldine. This was the first published grounded theory study